Submitted:

05 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

2.2. Preparation of Flavonoid from Chuju

2.3. Animal Experiments

2.4. Oral Glucose and Insulin Tolerance Tests

2.5. Biochemical Parameter Analysis

2.6. Histological Assessment

2.7. Analysis of Gut Microbiota

2.8. Western Blot Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

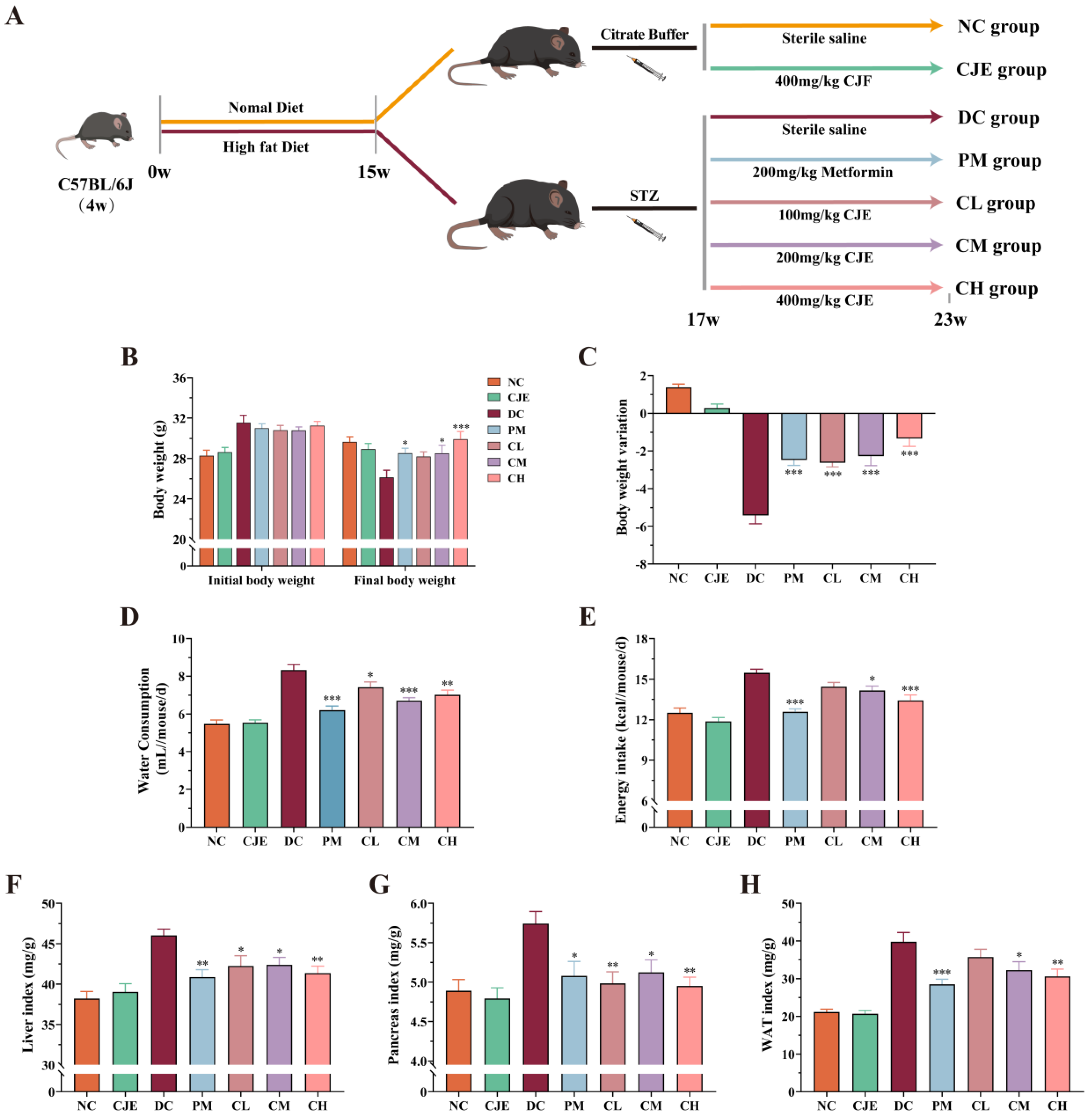

3.1. CJE Ameliorated Basal Physiological Indicators in T2DM Mice

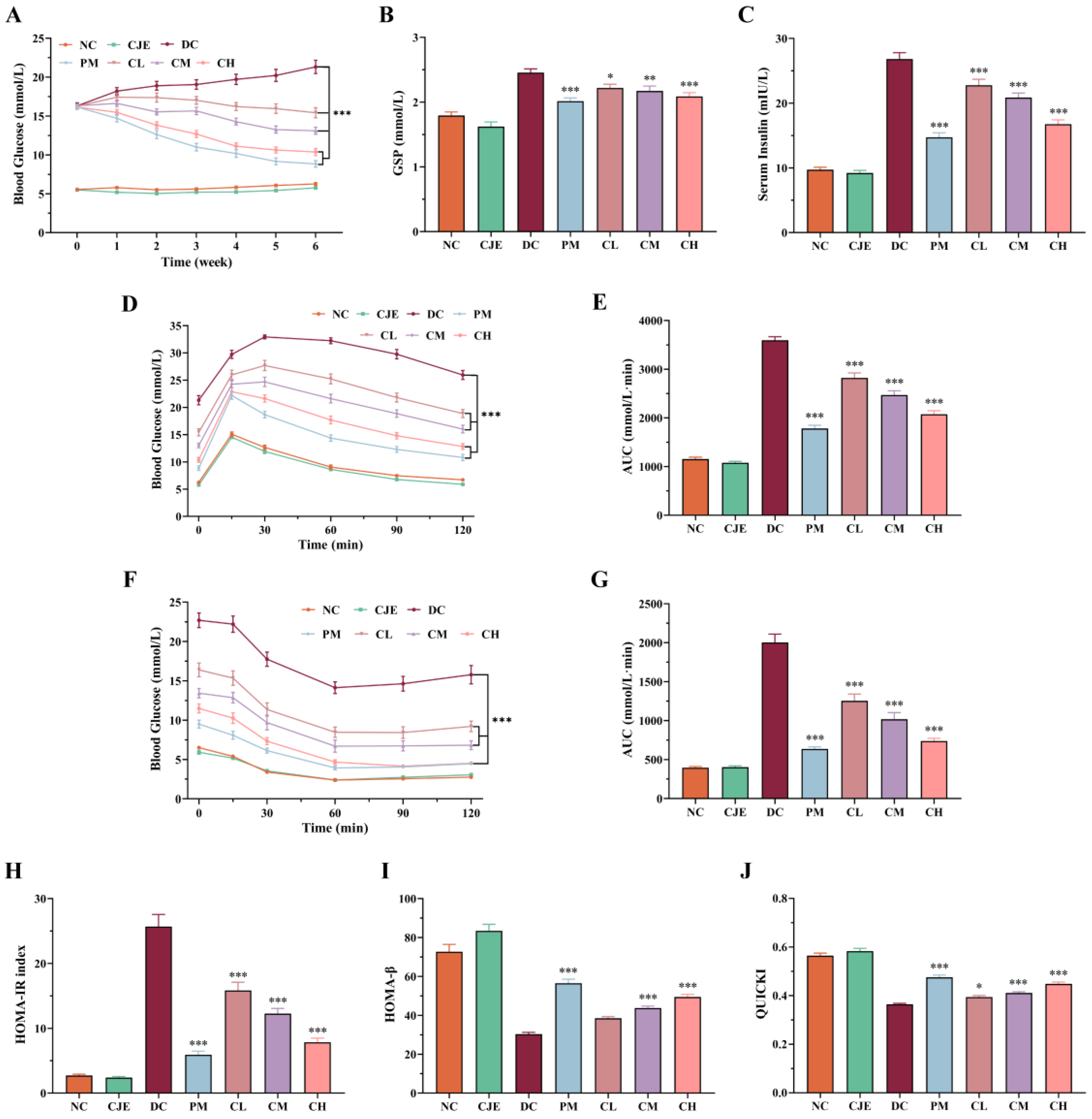

3.2. CJE Alleviated Hyperglycemia and Insulin Resistance in T2DM Mice

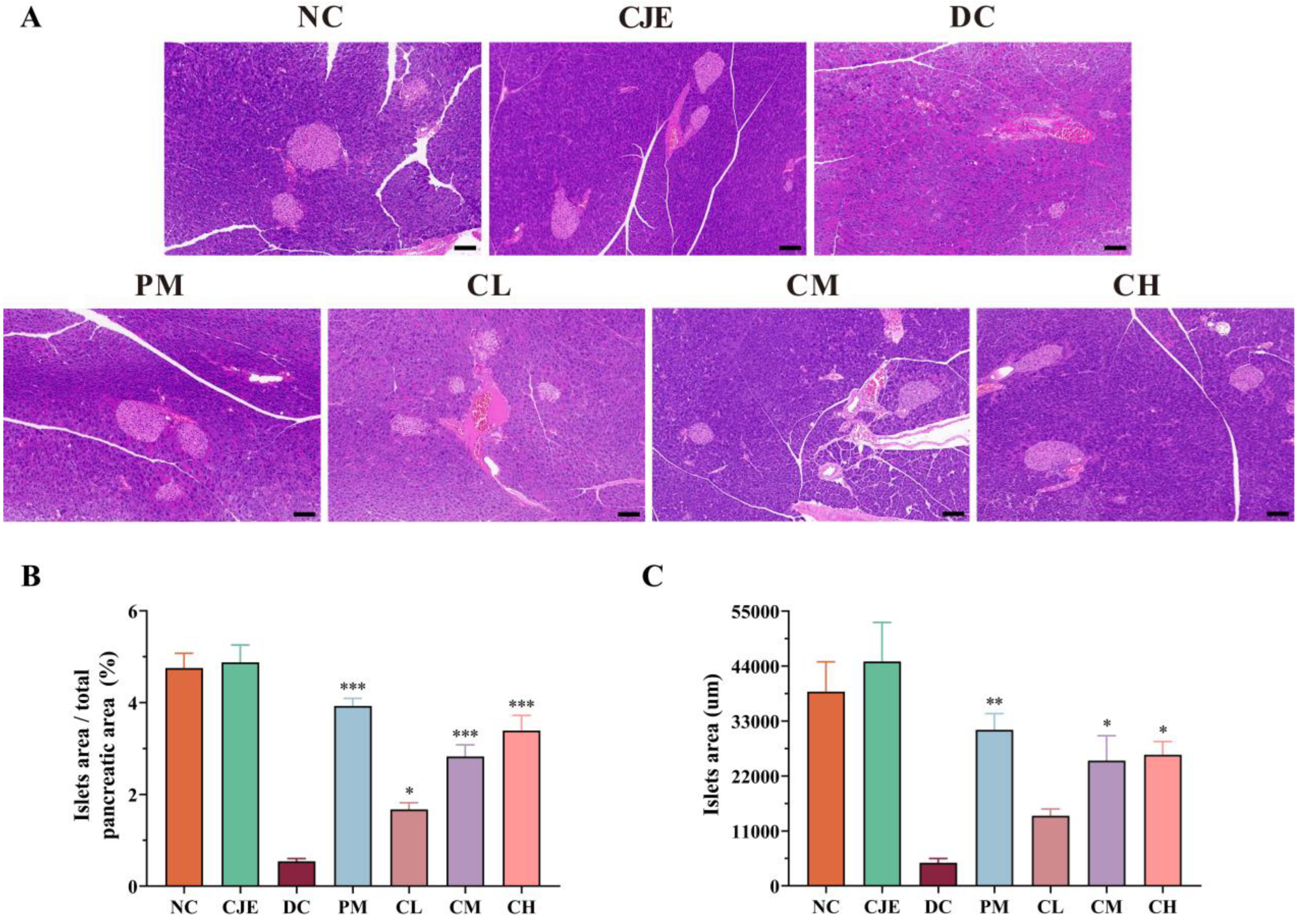

3.3. CJE Improved the Damage of Pancreatic Morphology and β Cell Function in T2DM Mice

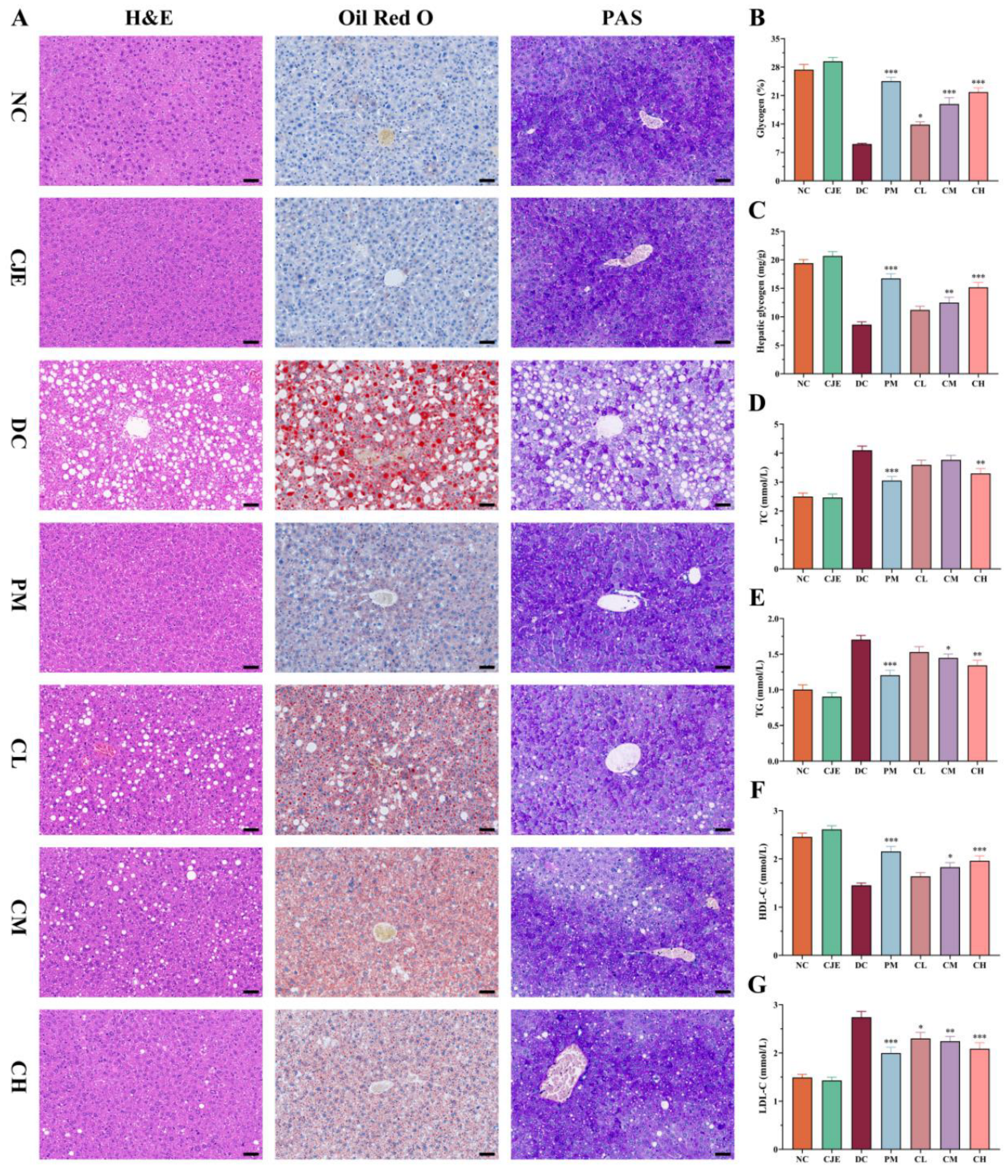

3.4. CJE Regulated Lipid Profile Disorders and Ameliorated Liver Injury in T2DM Mice

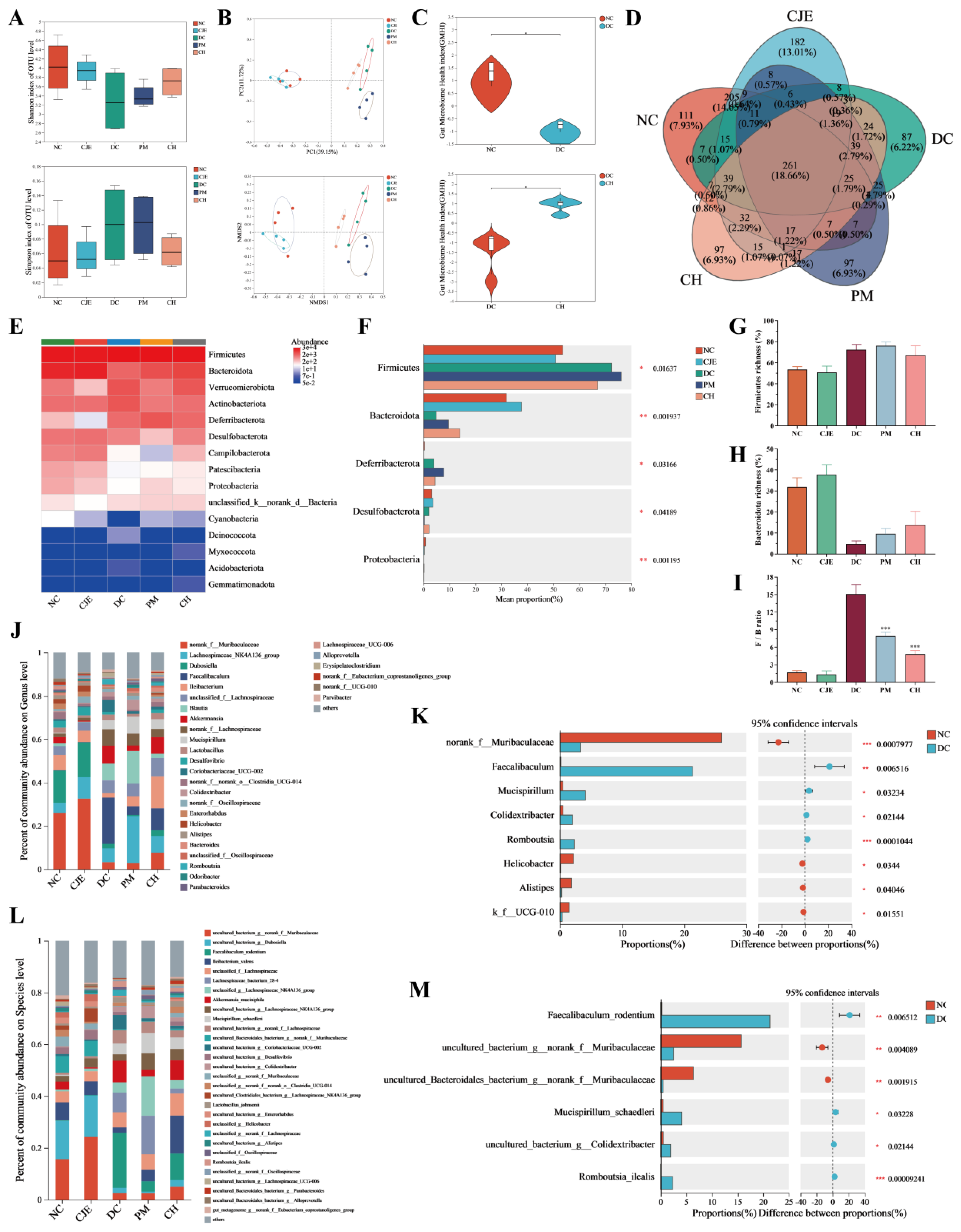

3.5. CJE Intervened Intestinal Microbiota Diversity and Composition of T2DM Mice

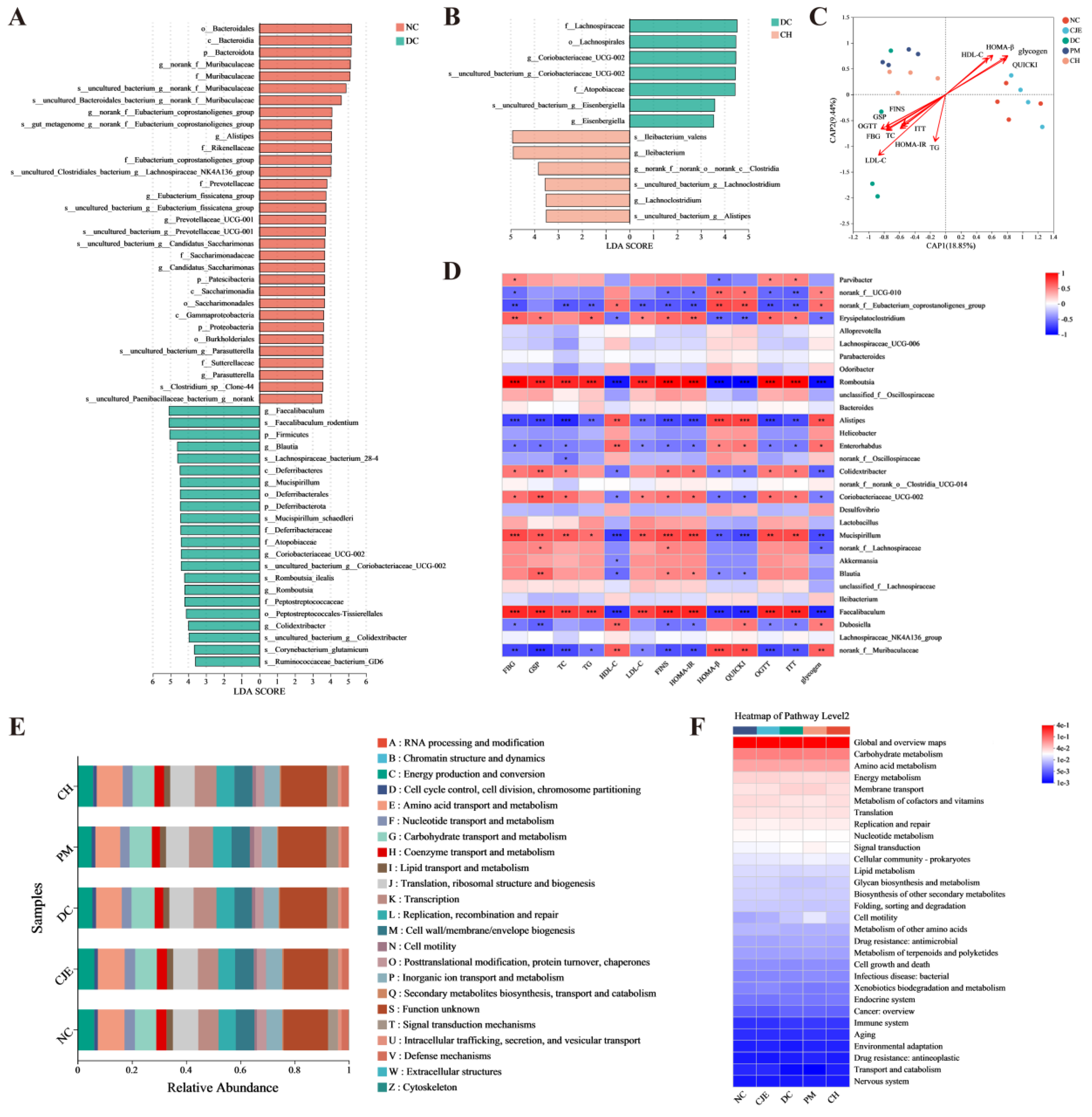

3.6. CJE Improved Metabolic Homeostasis of T2DM Mice by Mediating Intestinal Microbiota

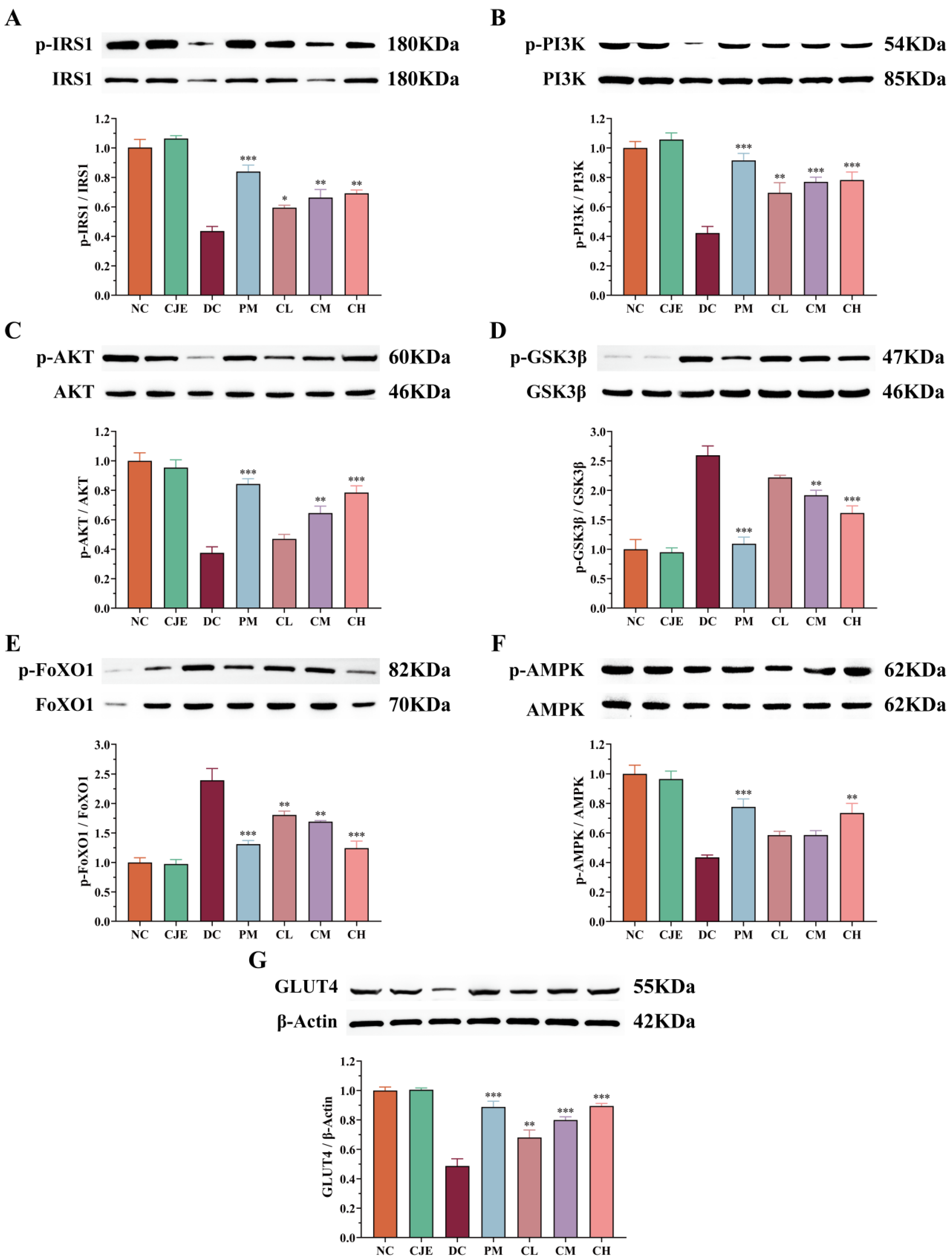

3.7. CJE Regulated Hypoglycemic Signaling Pathways in in the Liver of T2DM Mice

4. Discussion

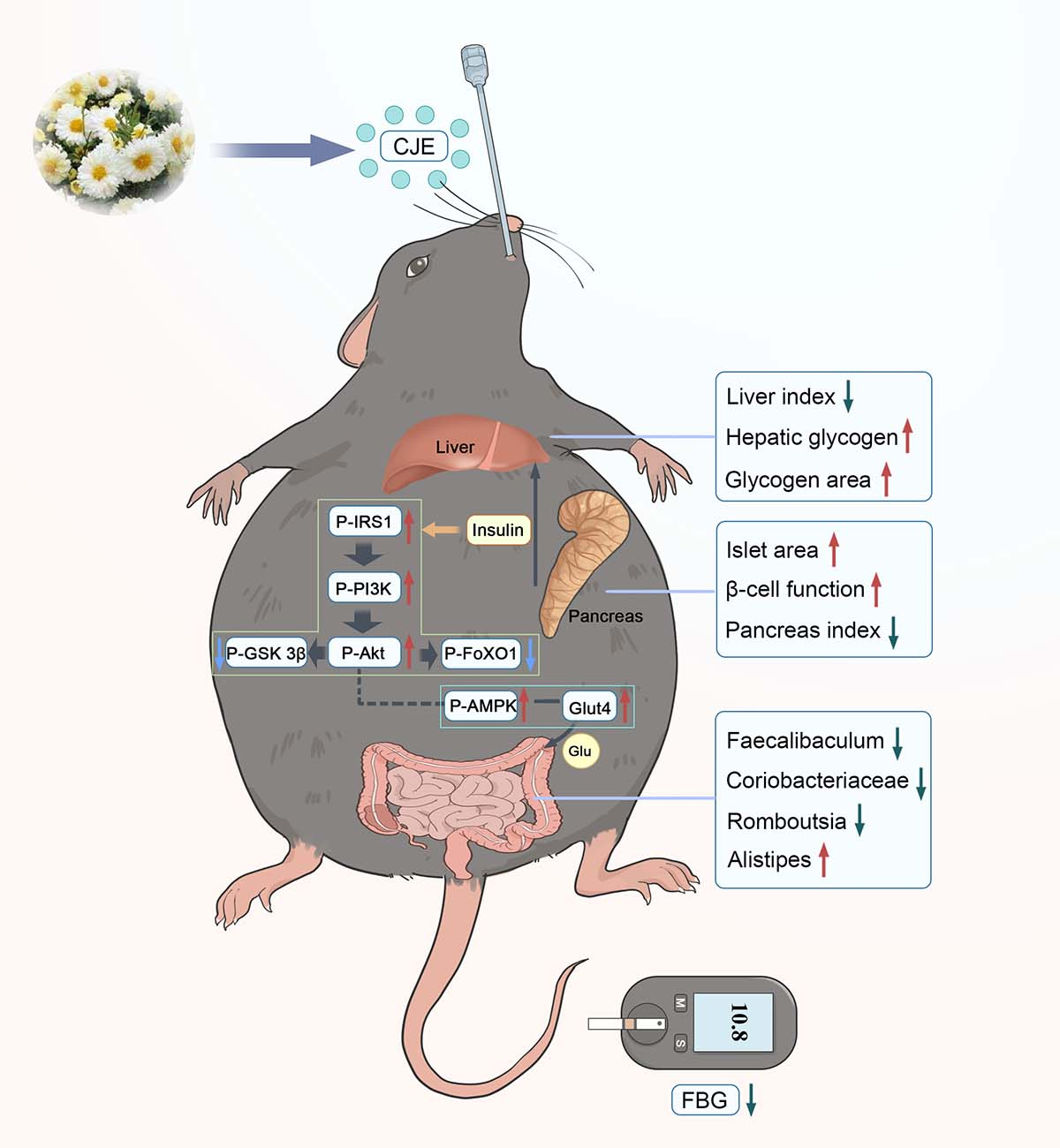

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cole, J. B.; Florez, J. C. Genetics of diabetes mellitus and diabetes complications. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B. B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J. C. N.; Mbanya, J. C.; Pavkov, M. E.; Ramachandaran, A.; Wild, S. H.; James, S.; Herman, W. H.; Zhang, P.; Bommer, C.; Kuo, S.; Boyko, E. J.; Magliano, D. J. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A. A.; Ogurtsova, K.; Shaw, J. E.; Bright, D.; Williams, R.; IDF Diabetes Atlas Committee. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peer, N.; Balakrishna, Y.; Durao, S. Screening for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 5, CD005266. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gao, F.; Zhou, J.; Xiang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Wan, L.; Chen, J. Structure features and in vitro hypoglycemic activities of polysaccharides from different species of Maidong. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 173, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asman, A. G.; Hoogendoorn, C. J.; McKee, M. D.; Gonzalez, J. S. Assessing the association of depression and anxiety with symptom reporting among individuals with type 2 diabetes. J. Behav Med. 2020, 43, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Zou, S.; Xu, H.; Li, M.; Tong, Z.; Xu, M.; Xu, X. Hypoglycemic activity of the Baker's yeast β-glucan in obese/type 2 diabetic mice and the underlying mechanism. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2016, 60, 2678–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Shi, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, S. Mechanisms underlying the effect of polysaccharides in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 144, 474–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshet, A.; and Segal, E. Identification of gut microbiome features associated with host metabolic health in a large population-based cohort. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, J. S.; Mak, W. Q.; Tan, L. K. S.; Ng, C. X.; Chan, H. H.; Yeow, S. H.; Foo, J. B.; Ong, Y. S.; How, C. W.; Khaw, K. Y. Microbiota-gut-brain axis and its therapeutic applications in neurodegenerative diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Izadifar, Z.; Cotton, J.; Chen, S.; Horvath, V.; Stejskalova, A.; Gulati, A.; LoGrande, N. T.; Budnik, B.; Shahriar, S.; Doherty, E. R.; Xie, Y.; To, T.; Gilpin, S. E.; Sesay, A. M.; Goyal, G.; Lebrilla, C. B.; Ingber, D. E. Mucus production, host-microbiome interactions, hormone sensitivity, and innate immune responses modeled in human cervix chips. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allin, K. H.; Nielsen, T.; Pedersen, O. Mechanisms in endocrinology: Gut microbiota in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 172, R167–R177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosomi, K.; Saito, M.; Park, J.; Murakami, H.; Shibata, N.; Ando, M.; Nagatake, T.; Konishi, K.; Ohno, H.; Tanisawa, K.; Mohsen, A.; Chen, Y. A.; Kawashima, H.; Natsume-Kitatani, Y.; Oka, Y.; Shimizu, H.; Furuta, M.; Tojima, Y.; Sawane, K.; Saika, A.; Kondo, S.; Yonejima, Y.; Takeyama, H.; Matsutani, A.; Mizuguchi, K.; Miyachi, M.; Kunisawa, J. Oral administration of Blautia wexlerae ameliorates obesity and type 2 diabetes via metabolic remodeling of the gut microbiota. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.; Bai, M.; Sun, Y.; Abdel-Samie M. A., S.; Lin, L. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of Chuzhou chrysanthemum essential oil. J. Funct. Foods. 2018, 48, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wang, L.; Ying, X.; Peng, J.; Jiang, M.; Bai, G.; Luo, G. Comparative evaluation of different cultivars of Flos Chrysanthemi by an anti-inflammatory-based NF-κB reporter gene assay coupled to UPLC-Q/TOF MS with PCA and ANN. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 174, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, G.; Long, M.; Shan, K.; Xie, C.; Yang, R. Antioxidant Effect of Chrysanthemum morifolium (Chuju) Extract on H2O2-Treated L-O2 Cells as Revealed by LC/MS-Based Metabolic Profiling. Antioxidants. 2022, 11, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Li, J.; Miao, Y.; Du, H.; Liu, D. Comparison of Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological Effects of Different Varieties of Chrysanthemum Flos in China. Chem. Biodivers. 2021, 18, e2100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; He, Z.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Yu, S.; Qian, Z. The Influence of Planting Sites on the Chemical Compositions of Chrysanthemum morifolium Flowers (Chuju) as Revealed by Py-GC/MS Combined with Multivariate Statistical Analysis. Chem. Biodivers. 2024, 21, e202401383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Ge, Q.; Ding, Z.; Pan, L.; Gu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Cai, H. Network pharmacology and metabolomics-based detection of the potential pharmacological effects of the active components in Chrysanthemum morifolium ‘Chuju’. Journal of Chinese Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2022, 31, 412–428. [Google Scholar]

- 20 Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, L.; Niu, Y.; Yao, D.; Song, L.; Okonkwo, C. E.; Phyllis, O.; Ma, H. Ultrasonic vacuum synergistic assisted ethanol extraction of steviol glycosides and kinetic studies. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 221, 119385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 21 Jiang, T.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Pi, M.; Hu, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zeng, J.; Li, B.; Xu, Z. Identification and quantification of flavonoids in edible dock based on UPLC-qTOF MS/MS and molecular networking. J. Food Compost. Anal. 2024, 133, 106339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Kong, X.; Xia, X.; Huang, X.; Mao, Z.; Han, J.; Shi, F.; Liang, Y.; Wang, A.; Zhang, F. Effects of ginseng peptides on the hypoglycemic activity and gut microbiota of a type 2 diabetes mellitus mice model. J. Funct. Foods. 2023, 111, 105897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Jiang, J.; Jing, T.; Hu, D.; Zhu, J.; Zeng, Y.; Pang, Y.; Huang, D.; Cheng, S.; Cao, C. A polysaccharide NAP-3 from Naematelia aurantialba: Structural characterization and adjunctive hypoglycemic activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 318, 121124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Q. W.; Zhou, T. S.; Qiu, W. H.; Wang, Y. K.; Xu, Q. L.; Ke, S. Z.; Wang, S. J.; Jin, W. H.; Chen, J. W.; Zhang, H. W.; Wei, B.; Wang, H. Characterization and hypoglycemic effects of sulfated polysaccharides derived from brown seaweed Undaria pinnatifida. Food Chem. 2021, 341, 128148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, C.; Einwallner, E. Study of In Vivo Glucose Metabolism in High-fat Diet-fed Mice Using Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) and Insulin Tolerance Test (ITT). J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 56672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, R. L.; Hackney, D. J.; Giering, E. L.; Zraika, S. Acclimation Prior to an Intraperitoneal Insulin Tolerance Test to Mitigate Stress-Induced Hyperglycemia in Conscious Mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2020, 61179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Liu, D.; Guo, Z.; Han, P.; Ma, Y.; Wu, M.; Zhang, R.; He, J. Physicochemical properties, structural characterization, and antidiabetic activity of selenylated low molecular weight apple pectin in HFD/STZ-induced type 2 diabetic mice. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 348, 122790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Hou, H.; Yang, M.; Zhang, H.; Sun, C.; Wei, L.; Xu, S.; Guo, W. Hypoglycemic effect of orally administered resistant dextrins prepared with different acids on type 2 diabetes mice induced by high-fat diet and streptozotocin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.; Liu, G.; Cao, X.; Zhu, S.; Li, Q.; Ji, G.; Han, Y.; Xiao, H. Hypoglycemic effects of wheat bran alkyresorcinols in high-fat/high-sucrose diet and low-dose streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetic male mice and protection of pancreatic β cells. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 3282–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, D.; Feng, X.; Lei, S.; Zhang, H.; Hu, W.; Yang, S.; Yu, X.; Su, Z. Pancreatic β-cell failure, clinical implications, and therapeutic strategies in type 2 diabetes. Chin. Med. J. 2024, 137, 791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, G.; Sun, H.; Chen, Y.; Guo, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Lu, C.; Wang, X. Antioxidant and hypoglycemic activity of tea polysaccharides with different degrees of fermentation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 228, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Hou, J.; Liu, H.; Zeng, R.; Li, X.; Han, M.; Li, Q.; Ji, L.; Pan, D.; Jia, W.; Zhong, W.; Xu, T. Plasma proteome profiling reveals the therapeutic effects of the PPAR pan-agonist chiglitazar on insulin sensitivity, lipid metabolism, and inflammation in type 2 diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Rellan, M. J.; Fondevila, M. F.; Fernandez, U.; Rodríguez, A.; Varela-Rey, M.; Veyrat-Durebex, C.; Seoane, S.; Bernardo, G.; Lopitz-Otsoa, F.; Fernández-Ramos, D.; Bilbao, J.; Iglesias, C.; Novoa, E.; Ameneiro, C.; Senra, A.; Beiroa, D.; Cuñarro, J.; Chantada-Vazquez, M. D.; Garcia-Vence, M.; Bravo, S. B.; Lima, N. D. S.; Porteiro, B.; Carneiro, C.; Vidal, A.; Tovar, S.; Müller, T. D.; Ferno, J.; Guallar, D.; Fidalgo, M.; Sabio, G.; Herzig, S.; Yang, W. H.; Cho, J. W.; Martinez-Chantar, M. L.; Perez-Fernandez, R.; López, M.; Dieguez, C.; Mato, J. M.; Millet, O.; Coppari, R.; Woodhoo, A.; Fruhbeck, G.; Nogueiras, R. O-GlcNAcylated p53 in the liver modulates hepatic glucose production. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Ma, J.; Li, R. Alterations of gut microbiota in biopsy-proven diabetic nephropathy and a long history of diabetes without kidney damage. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13(1), 12150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L.; Chu, J.; Li, H.; Sun, W.; Yang, C.; Wang, H.; Dai, W.; Yan, S.; Chen, X.; Xu, D. Alterations of the Gut Microbiota in Patients with Diabetic Nephropathy. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0032422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Lou, H.; Peng, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Comprehensive relationships between gut microbiome and faecal metabolome in individuals with type 2 diabetes and its complications. Endocrine. 2019, 66, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Pan, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; Wu, G.; Pan, Y. Acanthopanax trifoliatus (L.) Merr polysaccharides ameliorates hyperglycemia by regulating hepatic glycogen metabolism in type 2 diabetic mice. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1111287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Qi, X.; Yu, K.; Lu, A.; Lin, K.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, M.; Sun, Z. AMPK activation is involved in hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic activities of mogroside-rich extract from Siraitia grosvenorii (Swingle) fruits on high-fat diet/streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aodah, A. H.; Alkholifi, F. K.; Alharthy, K. M.; Devi, S.; Foudah, A. I.; Yusufoglu, H. S.; Alam, A. Effects of kaempherol-3-rhamnoside on metabolic enzymes and AMPK in the liver tissue of STZ-induced diabetes in mice. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, L.; Wang, L.; Guo, K.; Hou, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Q.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, L.; Niu, J.; Chen, C.; Song, L.; Hou, S.; Kong, L.; Li, X.; Ren, J.; Li, P.; Mohammadi, M.; Huang, Z. Paracrine FGFs target skeletal muscle to exert potent anti-hyperglycemic effects. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Li, C.; Wang, L. Glycolipid Metabolism and Metagenomic Analysis of the Therapeutic Effect of a Phenolics-Rich Extract from Noni Fruit on Type 2 Diabetic Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 2876–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tan, H.; Zhan, W.; Song, L.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X.; Lin, Z.; Wang, W.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L.; Bei, W.; Guo, J. Molecular mechanism of Fufang Zhenzhu Tiaozhi capsule in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease based on network pharmacology and validation in minipigs. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 274, 114056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 43Chen, C.; Huang, Q.; Li, C.; Fu, X. Hypoglycemic effects of a Fructus Mori polysaccharide in vitro and in vivo. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 2523–2535. [Google Scholar]

- Copps, K. D.; White, M. F. Regulation of insulin sensitivity by serine/threonine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate proteins IRS1 and IRS2. Diabetologia. 2012, 55, 2565–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Christensen, A.; Eriksson, G.; Laprade, W. M.; Pirzamanbein, B.; Hörnberg, M.; Linde, K.; Nilsson, J.; Skarsfeldt, M.; Leeming, D. J.; Mokso, R.; Verezhak, M.; Dahl, A.; Dahl, V.; Önnerhag, K.; Oghazi, M. R.; Mayans, S.; Holmberg, D. Structure-function analysis of time-resolved immunological phases in metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MASH) comparing the NIF mouse model to human MASH. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhou, S.; Zhou, T. Hypoglycemic Effects of Gynura divaricata (L. ) DC Polysaccharide and Action Mechanisms via Modulation of Gut Microbiota in Diabetic Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 9893–9905. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Wu, Q.; Qian, L.; He, J.; Ni, Y.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Yuan, R.; Liu, S.; Shen, L.; Zhang, M.; Sheng, B.; Li, P.; Kang, K.; Wu, L.; Fang, Q.; Long, X.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Ye, Y.; Ye, J.; Bao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, G.; Liu, X.; Panagiotou, G.; Xu, A.; Jia, W. Resistant starch intake facilitates weight loss in humans by reshaping the gut microbiota. Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 578–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Cheng, W.; Shi, T.; Liao, Y.; Zhou, M.; Liao, Z. Rutin alleviates colon lesions and regulates gut microbiota in diabetic mice. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Yang, C.; Chen, M.; Lv, X.; Liu, B.; Yi, L.; Cornara, L.; Wei, M.; Yang, Y.; Tundis, R.; Xiao, J. Regulatory Efficacy of Brown Seaweed Lessonia nigrescens Extract on the Gene Expression Profile and Intestinal Microflora in Type 2 Diabetic Mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, 1700730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, B.; Ren, D.; Li, T.; Niu, P.; Zhang, X.; Yang, X.; Xiao, J. Fu Brick Tea Manages HFD/STZ-Induced Type 2 Diabetes by Regulating the Gut Microbiota and Activating the IRS1/PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 8274–8287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Yang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X. Polyphenol-Rich Loquat Fruit Extract Prevents Fructose-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease by Modulating Glycometabolism, Lipometabolism, Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, Intestinal Barrier, and Gut Microbiota in Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 7726–7737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, Y.; Edwards, M.; Huang, Y.; Bilate, A. M.; Araujo, L. P.; Tanoue, T.; Atarashi, K.; Ladinsky, M. S.; Reiner, S. L.; Wang, H. H.; Mucida, D.; Honda, K.; Ivanov, I. I. Microbiota imbalance induced by dietary sugar disrupts immune-mediated protection from metabolic syndrome. Cell. 2022, 185, 3501–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, D.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H. Lactobacillus casei Zhang exerts anti-obesity effect to obese glut1 and gut-specific-glut1 knockout mice via gut microbiota modulation mediated different metagenomic pathways. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 2003–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedighi, M.; Razavi, S.; Navab-Moghadam, F.; Khamseh, M. E.; Alaei-Shahmiri, F.; Mehrtash, A.; Amirmozafari, N. Comparison of gut microbiota in adult patients with type 2 diabetes and healthy individuals. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 111, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C. L.; Yu, R.; Li, F.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, D.; Qi, C.; Yin, Y.; Sun, J. Modulation of fat metabolism and gut microbiota by resveratrol on high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, F.; Kang, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, H.; Peng, Y.; Yang, M.; Zheng, Y.; Shao, J.; Yue, X. Whey protein and xylitol complex alleviate type 2 diabetes in C57BL/6 mice by regulating the intestinal microbiota. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, T.; Constantine, E.; Nobles, Z.; Butler, E.; Renteria, K. M.; Teoh, C. M.; Koh, G. Y. Supplementation of Vitamin D3 and Fructooligosaccharides Downregulates Intestinal Defensins and Reduces the Species Abundance of Romboutsia ilealis in C57BL/6J Mice. Nutrients. 2024, 16, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, W.; Ji, S.; Wang, J.; Luo, J.; Lu, B. Sophora japonica flowers and their main phytochemical, rutin, regulate chemically induced murine colitis in association with targeting the NF-κB signaling pathway and gut microbiota. Food Chem. 2022, 393, 133395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C. H.; Li, Y. X.; Xu, Y. C.; Wang, N. N.; Yan, Q. J.; Jiang, Z. Q. Tamarind Xyloglucan Oligosaccharides Attenuate Metabolic Disorders via the Gut-Liver Axis in Mice with High-Fat-Diet-Induced Obesity. Foods. 2023, 12, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, T.; Kubota, T.; Nakanishi, Y.; Tsugawa, H.; Suda, W.; Kwon, A. T.-J.; Yazaki, J.; Ikeda, K.; Nemoto, S.; Mochizuki, Y.; Kitami, T.; Yugi, K.; Mizuno, Y.; Yamamichi, N.; Yamazaki, T.; Takamoto, I.; Kubota, N.; Kadowaki, T.; Arner, E.; Carninci, P.; Ohara, O.; Arita, M.; Hattori, M.; Koyasu, S.; Ohno, H. Gut microbial carbohydrate metabolism contributes to insulin resistance. Nature. 2023, 621, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, R. L.; Wang, L. Y.; Zhang, T.; Qian, D.; Tang, D. D.; He, C. X.; Wu, C. J.; Ai, L. Hydroxy-α-sanshool isolated from Zanthoxylum bungeanum Maxim. has antidiabetic effects on high-fat-fed and streptozotocin-treated mice via increasing glycogen synthesis by regulation of PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β/GS signaling. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1089558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Sun, X.; Lin, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xu, Z.; Liu, P.; Liu, Z.; Huang, H. Gentiopicroside targets PAQR3 to activate the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and ameliorate disordered glucose and lipid metabolism. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2022, 12, 2887–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Liu, G.; Guo, J.; Su, Z. The PI3K/AKT pathway in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Int J Biol Sci. 2018, 14, 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tang, Y.; Shi, S.; Gao, S.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, D.; Chen, T.; He, Q.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Y. Tetrahedral Framework Nucleic Acids Ameliorate Insulin Resistance in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus via the PI3K/Akt Pathway. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021, 13, 40354–40364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Park, S.; Lin, X.; Copps, K.; Yi, X.; White, M. F. Irs1 and Irs2 signaling is essential for hepatic glucose homeostasis and systemic growth. J. Clin. Invest. 2006, 116, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniguchi, C. M.; Kondo, T.; Sajan, M.; Luo, J.; Bronson, R.; Asano, T.; Farese, R.; Cantley, L. C.; Kahn, C. R. Divergent regulation of hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism by phosphoinositide 3-kinase via Akt and PKClambda/zeta. Cell Metab. 2006, 3, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Zhou, X.; Huang, X.; Wang, C.; Li, Y. The IRS/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway mediates olanzapine-induced hepatic insulin resistance in male rats. Life Sci. 2019, 217, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.; Chen, L.; Wang, R.; Chen, Y.; Deng, S.; Shen, G.; Liu, S.; Xiang, X. Hypoglycemic mechanism of Tegillarca granosa polysaccharides on type 2 diabetic mice by altering gut microbiota and regulating the PI3K-akt signaling pathwaye. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness. 2024, 13, 842–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Chen, X.; He, C.; Xiao, C.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Q.; Chen, J.; Bo, H. Sanhuang xiexin decoction synergizes insulin/PI3K-Akt/FoxO signaling pathway to inhibit hepatic glucose production and alleviate T2DM. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 306, 116162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Y.; Li, Q. M.; Yu, N. J.; Chen, W. D.; Zha, X. Q.; Wu, D. L.; Pan, L. H.; Duan, J.; Luo, J. P. Dendrobium huoshanense polysaccharide regulates hepatic glucose homeostasis and pancreatic β-cell function in type 2 diabetic mice. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 211, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, F. G.; Zhang, W. S.; Pan, A.; Yang, Y. L.; Liu, J. F.; Li, P.; Liu, B. L.; Qi, L. W. Ginsenoside Rg1 Inhibits Glucagon-Induced Hepatic Gluconeogenesis through Akt-FoxO1 Interaction. Theranostics 2017, 7, 4001–4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; He, C. X.; Li, R. L.; Qian, D.; Wang, L. Y.; Chen, W. W.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, C. J. Zanthoxylum bungeanum amides ameliorates nonalcoholic fatty liver via regulating gut microbiota and activating AMPK/Nrf2 signaling. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 318, 116848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, D.; Chen, J.; Xu, Y.; He, C.; Wu, Y.; Peng, W.; Li, X. Pungent agents derived from the fruits of Zanthoxylum armatum DC. are beneficial for ameliorating type 2 diabetes mellitus via regulation of AMPK/PI3K/Akt signaling. Journal of Functional Foods, J. Funct. Foods, 2024, 116, 106160. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J. H.; Noh, J. R.; Kim, Y. H.; Kim, J. H.; Kang, E. J.; Choi, D. H.; Choi, J. H.; An, J. P.; Oh, W. K.; Lee, C. H. Sicyos angulatus Prevents High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity and Insulin Resistance in Mice. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 17, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; Xie, Z.; Cao, D.; Gong, M.; Yang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Ou, Y. C-Phycocyanin inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis and increases glycogen synthesis via activating Akt and AMPK in insulin resistance hepatocytes. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 2829–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leto, D.; Saltiel, A. R. Regulation of glucose transport by insulin: traffic control of GLUT4, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhao, S. X.; Xu, B. Q.; Zhang, Y. Q. Gynura divaricata ameliorates hepatic insulin resistance by modulating insulin signalling, maintaining glycolipid homeostasis and reducing inflammation in type 2 diabetic mice. Toxicol. Res. 2019, 8, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Abaydula, Y.; Li, D.; Tan, H.; Ma, X. Taurine ameliorates oxidative stress by regulating PI3K/Akt/GLUT4 pathway in HepG2 cells and diabetic rats. J. Funct. Foods. 2021, 85, 104629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Yu, H. C.; Cha, H. N.; Park, S.; Lee, Y.; Yoon, S. J.; Park, S. Y.; Park, B. H.; Bae, E. J. PAK4 phosphorylates and inhibits AMPKα to control glucose uptake. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, T.; Miyakawa, N.; Arakaki, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Nakahara, R.; Ali, T. F. S.; Biswas, T.; Todaka, M.; Kondo, T.; Fujita, M.; Otsuka, M.; Araki, E.; Tateishi, H. An antifibrotic compound that ameliorates hyperglycaemia and fat accumulation in cell and HFD mouse models. Diabetologia. 2024, 67, 2568–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Flavonoids | Content (μg/g) |

|---|---|

| Apigenin 6, 8-digalactoside | 77245.92831 |

| Dicaffeoyl quinolactone | 60064.4289 |

| Apigenin 6-C-glucoside 8-C-arabinoside | 54672.57871 |

| Luteolin-4'-O-glucoside | 34516.45459 |

| Isoshaftoside | 24582.14705 |

| Scutellarin | 24113.02598 |

| Quercetin 3-O-malonylglucoside | 16414.19393 |

| Chrysoeriol 7-O-glucoside | 14663.34312 |

| Quercetin-3, 4'-O-di-beta-glucoside | 13151.14052 |

| Luteolin 6-C-glucoside 8-C-arabinoside | 11983.51217 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).