Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

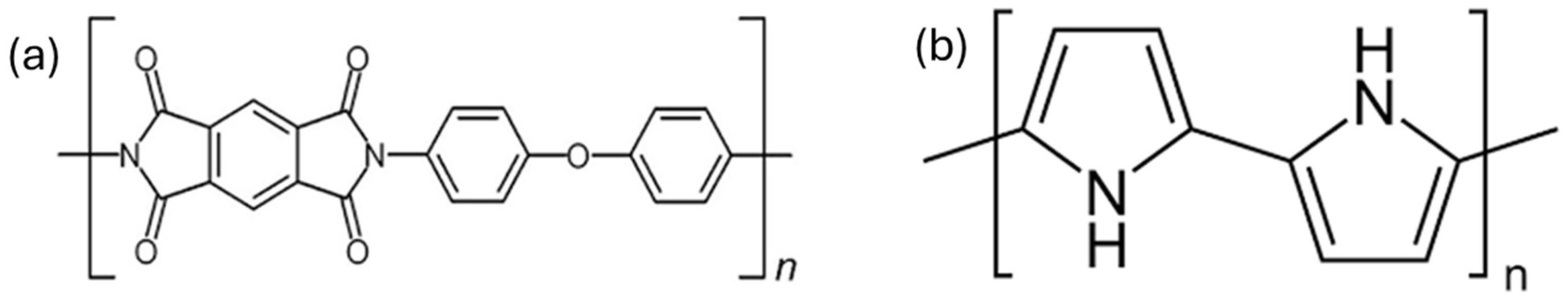

1.1. Polyimide

1.2. Polypyrrole

| Property | Standalone CNT Sheets | Graphene Sheets | Activated Carbon | Carbon Fibers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical Conductivity | ~103–104 S/cm (highly conductive). | ~104–105 S/cm (extremely high for high-quality graphene). | ~10–100 S/cm (moderate conductivity). | ~102–103 S/cm (depends on fiber alignment and purity). |

| Tensile Strength | ~150–300 MPa (moderate strength). | ~100–150 MPa (weaker but improves when stacked). | ~20–80 MPa (low due to porous structure). | ~1–5 GPa (exceptionally high for advanced fibers). |

| Young’s Modulus | ~10–20 GPa (high stiffness). | ~1–5 GPa (lower stiffness due to 2D nature). | ~0.5–2 GPa (weak mechanical stability). | ~70–300 GPa (extremely high for structural uses). |

| Thermal Conductivity | ~1000–2000 W/m·K (exceptionally high). | ~5000 W/m·K (highest known for pure graphene). | ~1–10 W/m·K (low due to high porosity). | ~100–600 W/m·K (moderate, improves with alignment). |

| Porosity | ~10–50 nm (moderate porosity, defined by CNT bundle packing). | ~Few nanometers (depends on stacking, typically low). | ~0.1–1 μm (high porosity due to activated structure). | Negligible (dense and aligned structure). |

| Density | ~1.3–1.5 g/cm3 (lightweight). | ~1–2 g/cm3 (depends on number of layers and defects). | ~0.5–0.9 g/cm3 (very lightweight). | ~1.8–2.0 g/cm3 (heavier due to structural density). |

| Specific Capacitance | ~10–50 F/g (limited to double-layer capacitance). | ~50–200 F/g (depends on surface area and electrolyte). | ~100–300 F/g (high due to extensive surface area). | ~10–50 F/g (low due to dense structure). |

| Thermal Stability | Stable up to ~600–800 °C in inert environments. | Stable up to ~400 °C in air, higher in inert atmospheres. | Stable up to ~600 °C (depends on activation process). | Stable up to ~1000 °C in inert conditions. |

| Flexibility | High; bendable and stretchable. | High for single-layer graphene; reduced for stacked layers. | Low; brittle and prone to cracking. | Low; rigid and prone to fracture under bending. |

| Scalability | Challenging; uniformity over large areas is difficult. | Difficult; large-scale production of defect-free sheets is hard. | High; widely available and inexpensive. | Moderate; high-quality fibers are expensive to produce. |

| Properties | Polypyrrole (PPy) | Polyimide (PI) |

|---|---|---|

| Electrical Conductivity | ~10–100 S/cm (doped with appropriate agents like p-toluene sulfonic acid) | ~10−12 S/cm (intrinsic); can be increased with conductive additives like CNTs. |

| Redox Activity | Exhibits pseudocapacitance; specific capacitance values range from 200–600 F/g, depending on structure and doping. | No intrinsic redox activity; primarily used as a structural matrix. |

| Mechanical Strength | Moderate; tensile strength ranges from 10–50 MPa, brittle in pure form. | High; tensile strength ranges from 80–200 MPa, depending on processing and reinforcement. |

| Thermal Stability | Degrades above 150–200 °C, depending on polymerization and doping conditions. | High stability: thermal degradation starts at ~400 °C, suitable for high-temperature applications. |

| Porosity Contribution | Can form layers with pores in the range of 10–50 nm (dependent on deposition conditions). | Porosity is tunable; partial imidization at 90 °C results in a porous structure, while full imidization at 250 °C reduces porosity. |

| Chemical Stability | Sensitive to over-oxidation in electrolytes; stability depends on the potential range. | Excellent chemical stability; resistant to solvents, acids, and bases. |

| Young’s Modulus | ~1–2 GPa (moderate, brittle polymer). | ~2–8 GPa (high, depends on reinforcement and processing conditions). |

| Density | ~1.5 g/cm3 (bulk material). | ~1.4 g/cm3 (varies slightly with processing). |

| Specific Capacitance | Ranges from 200–600 F/g (varies with doping and structure). | Not applicable; PI does not contribute directly to capacitance. |

| Scalability | Easily deposited via chemical or electrochemical polymerization. | Scalable synthesis through imidization of polyamic acid, suitable for large-scale applications. |

2. Experimental

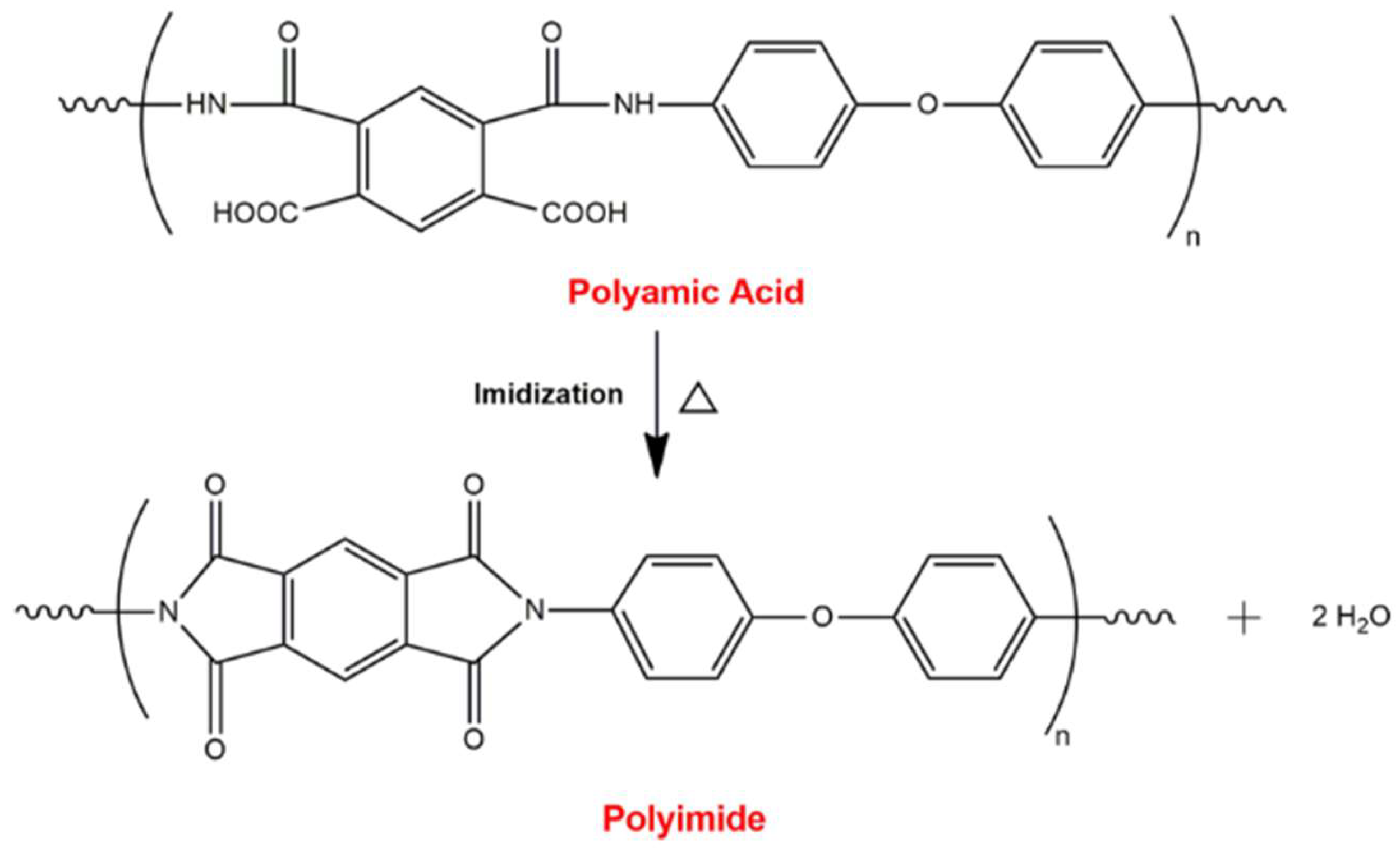

2.1. Synthesis of Polyimide

2.2. Electrochemical Deposition of Polypyrrole

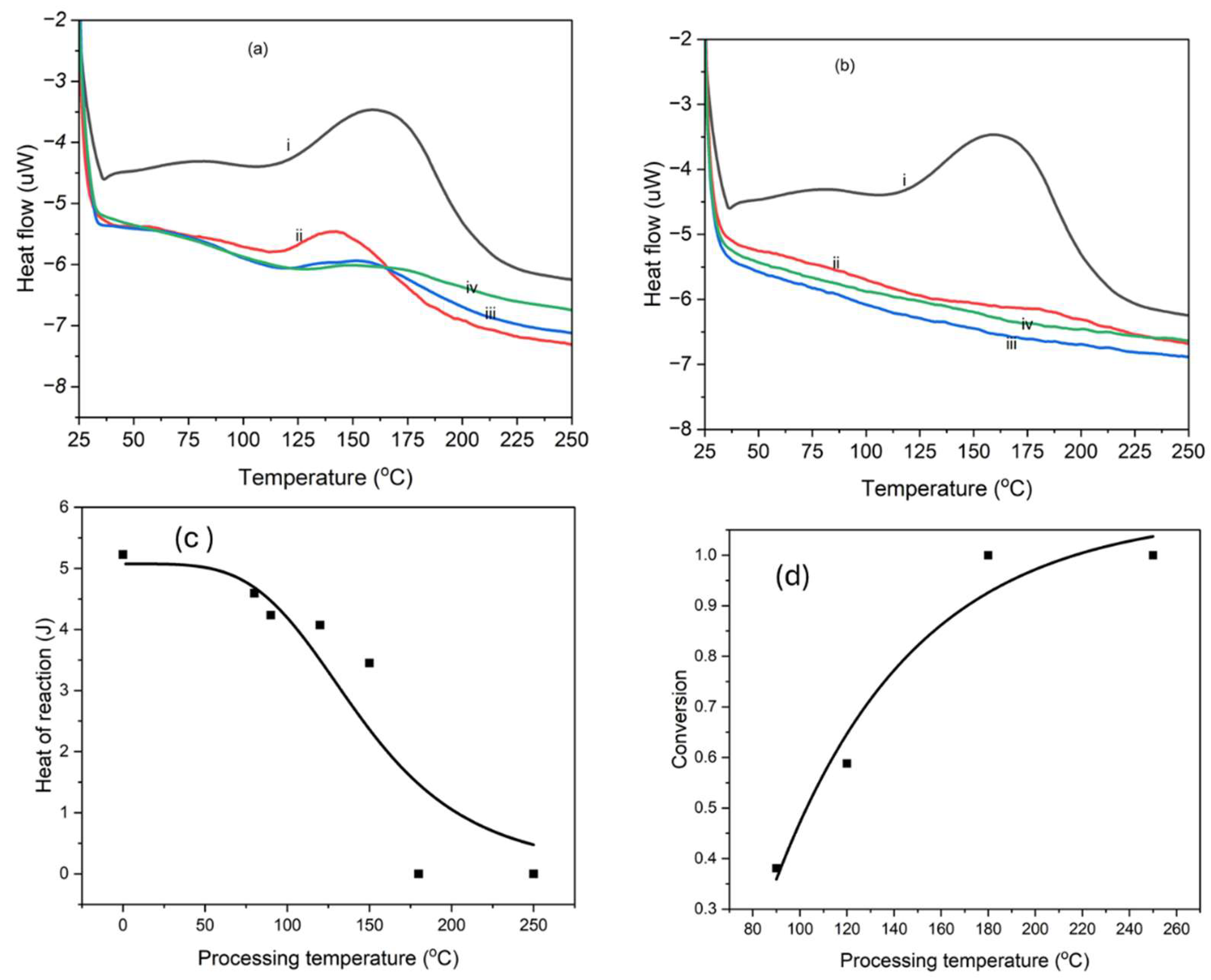

2.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

2.4. Electrochemical Characterization, EC

2.5. Electrochemical Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Thermal Analysis and Imidization

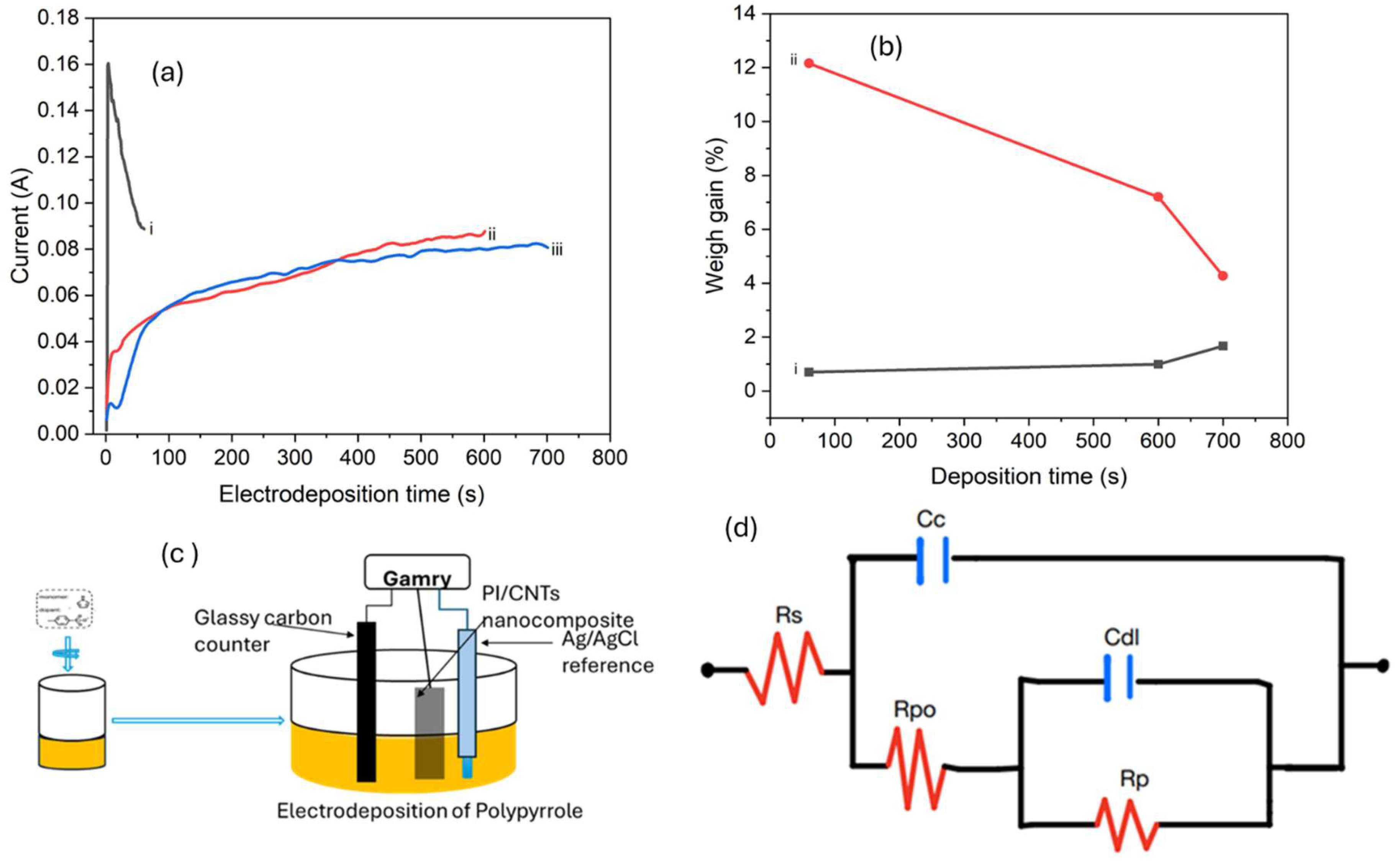

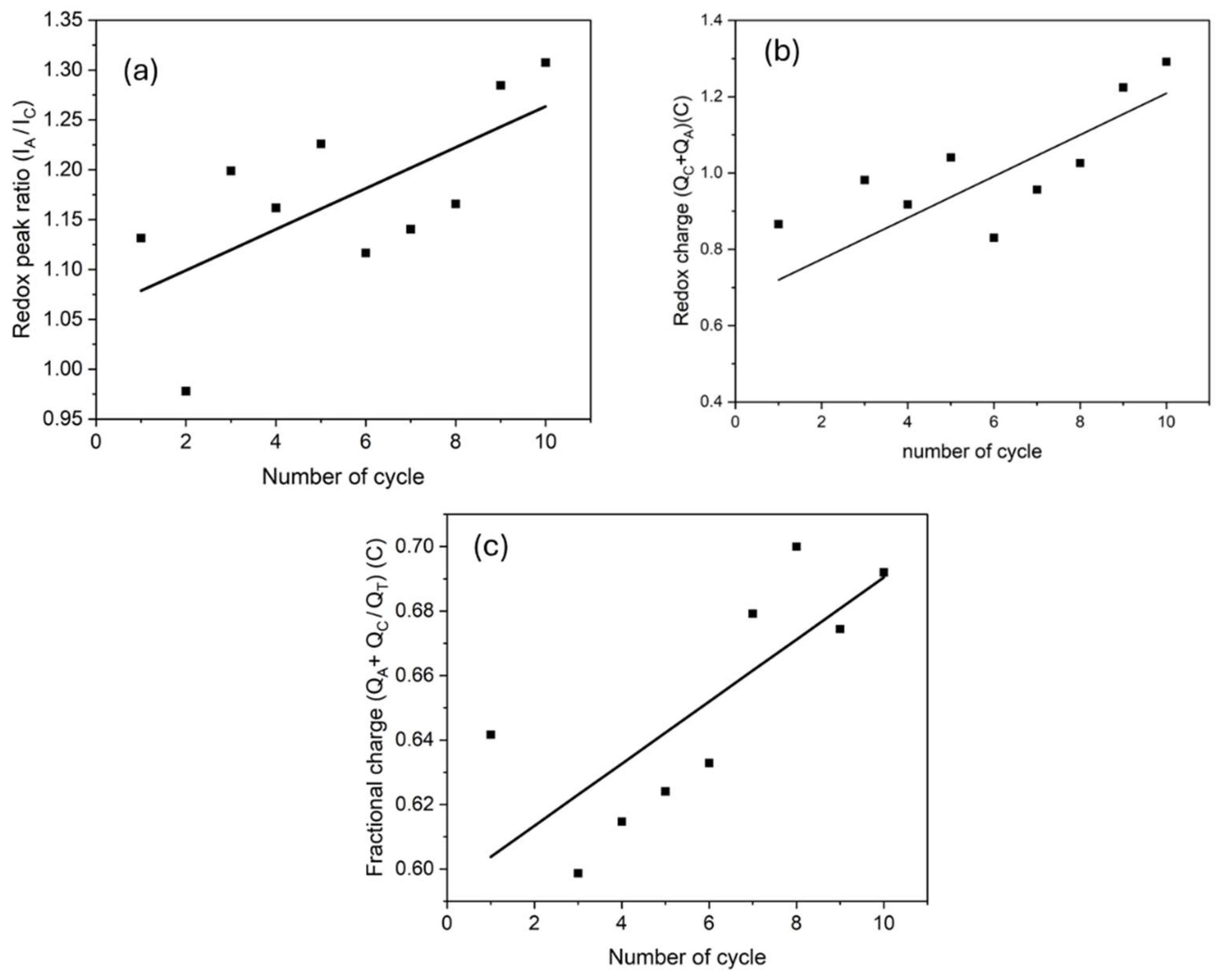

3.2. Electrodeposition of Polypyrrole

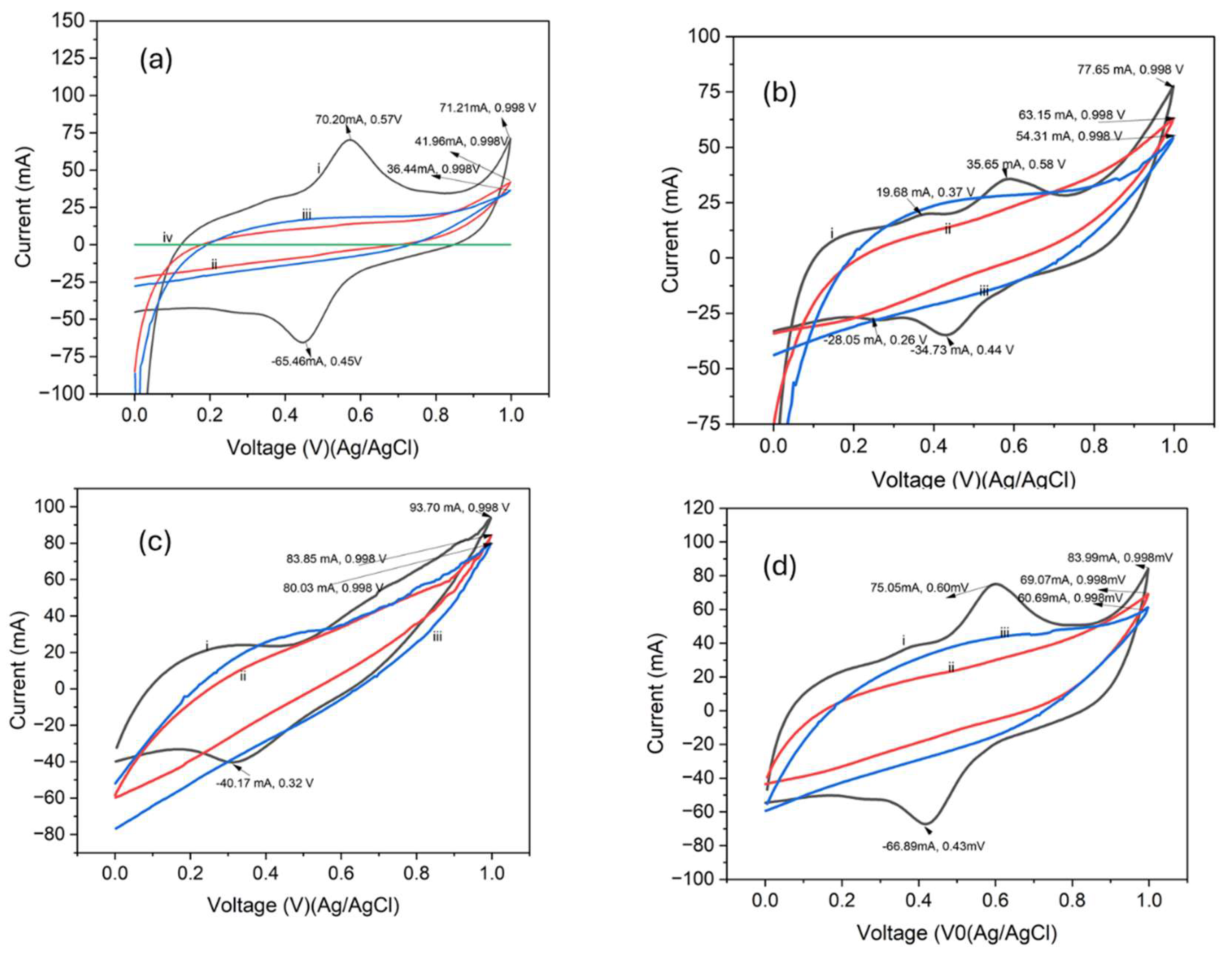

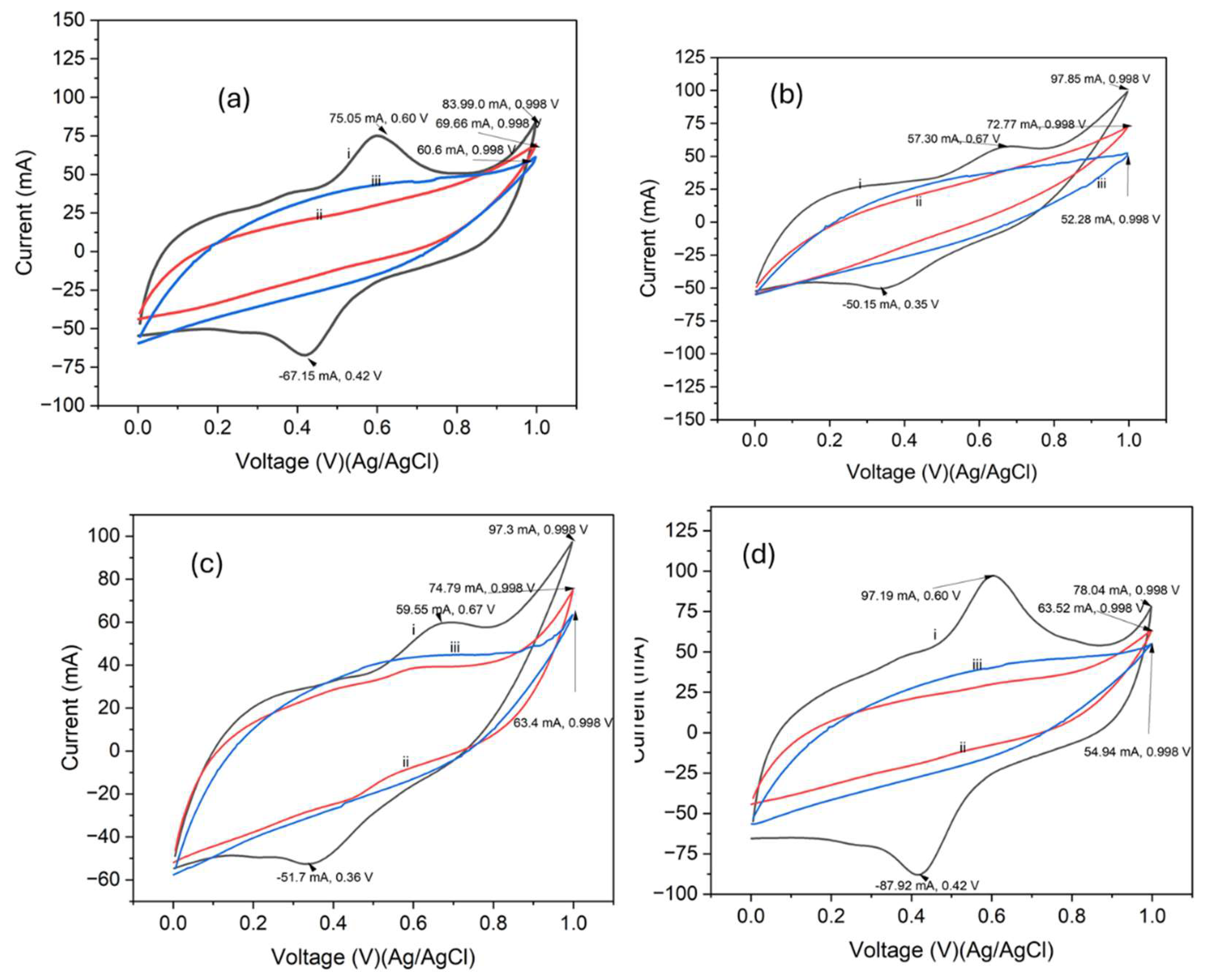

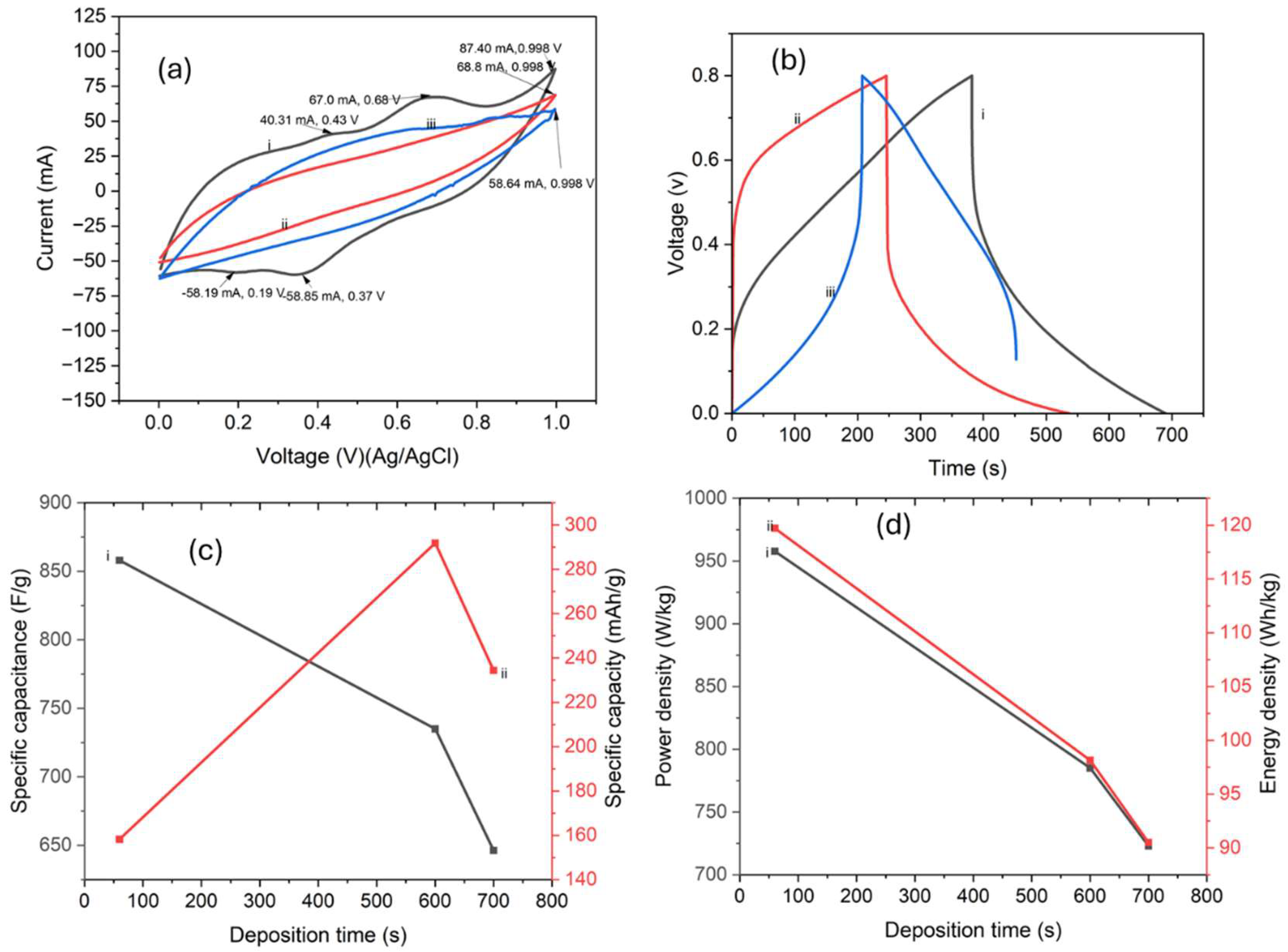

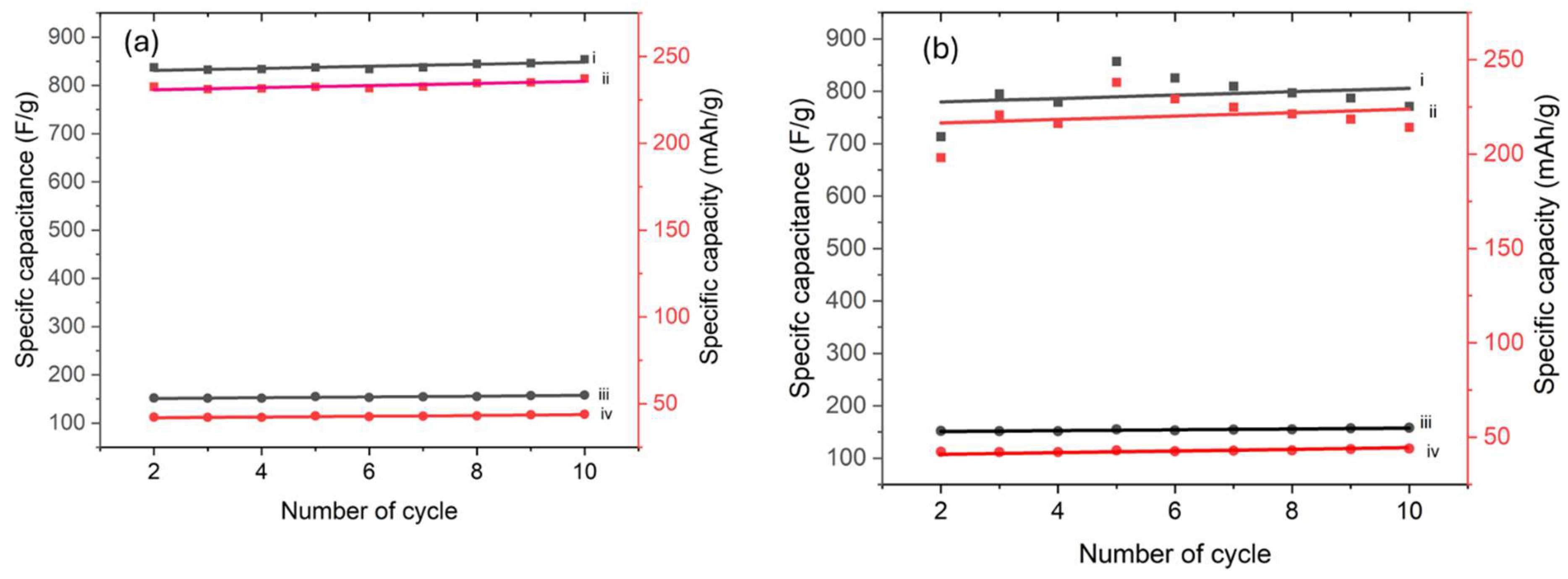

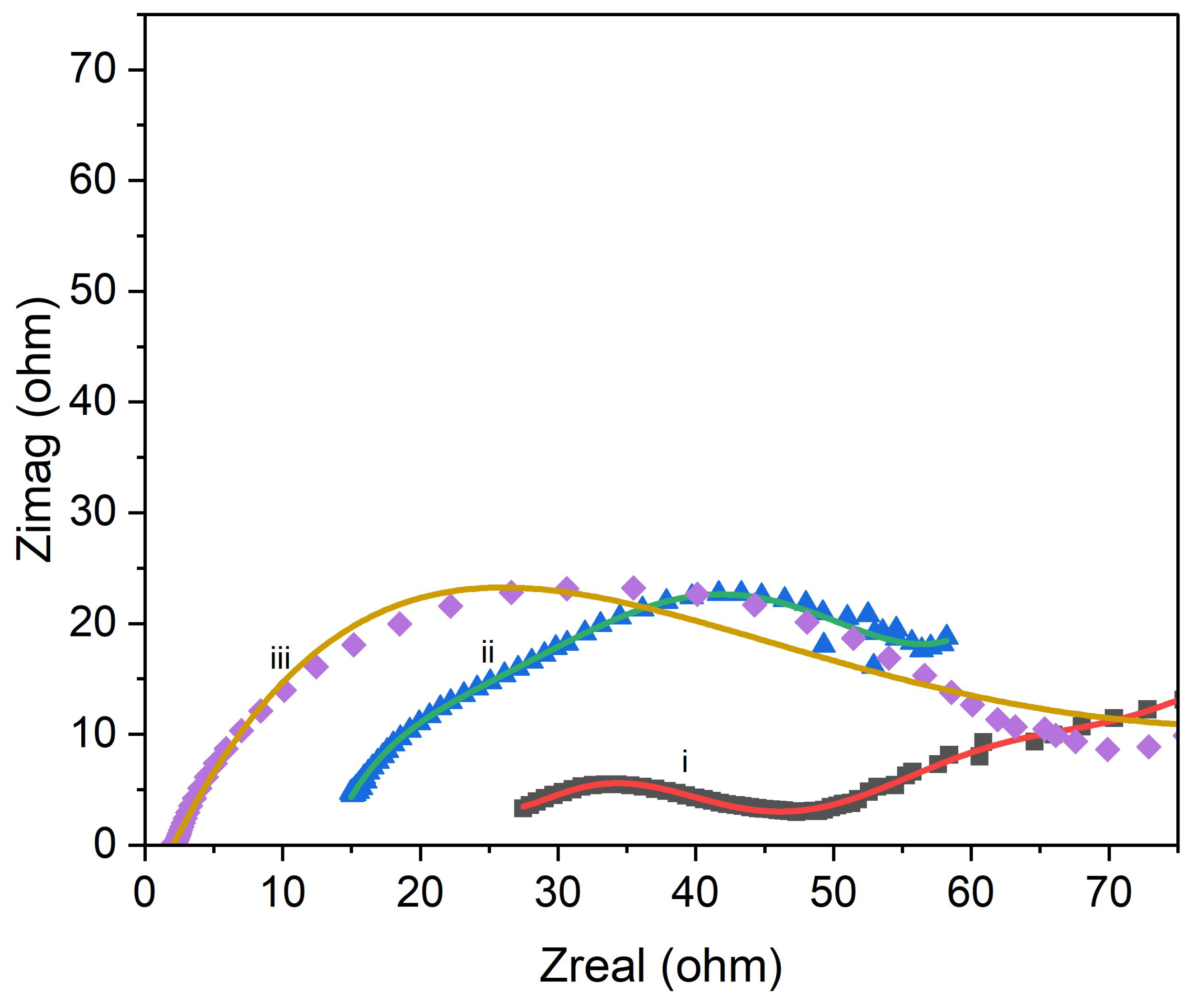

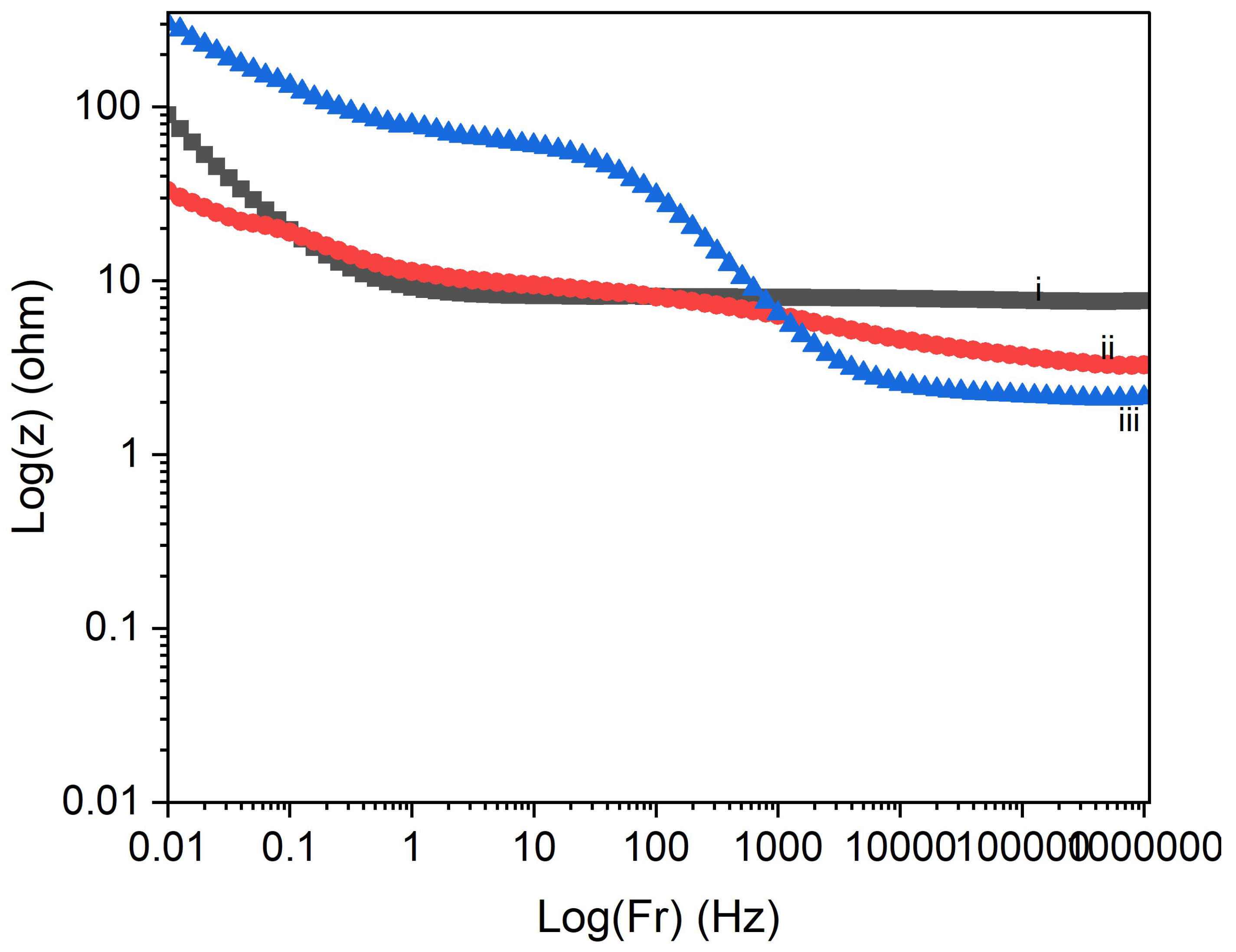

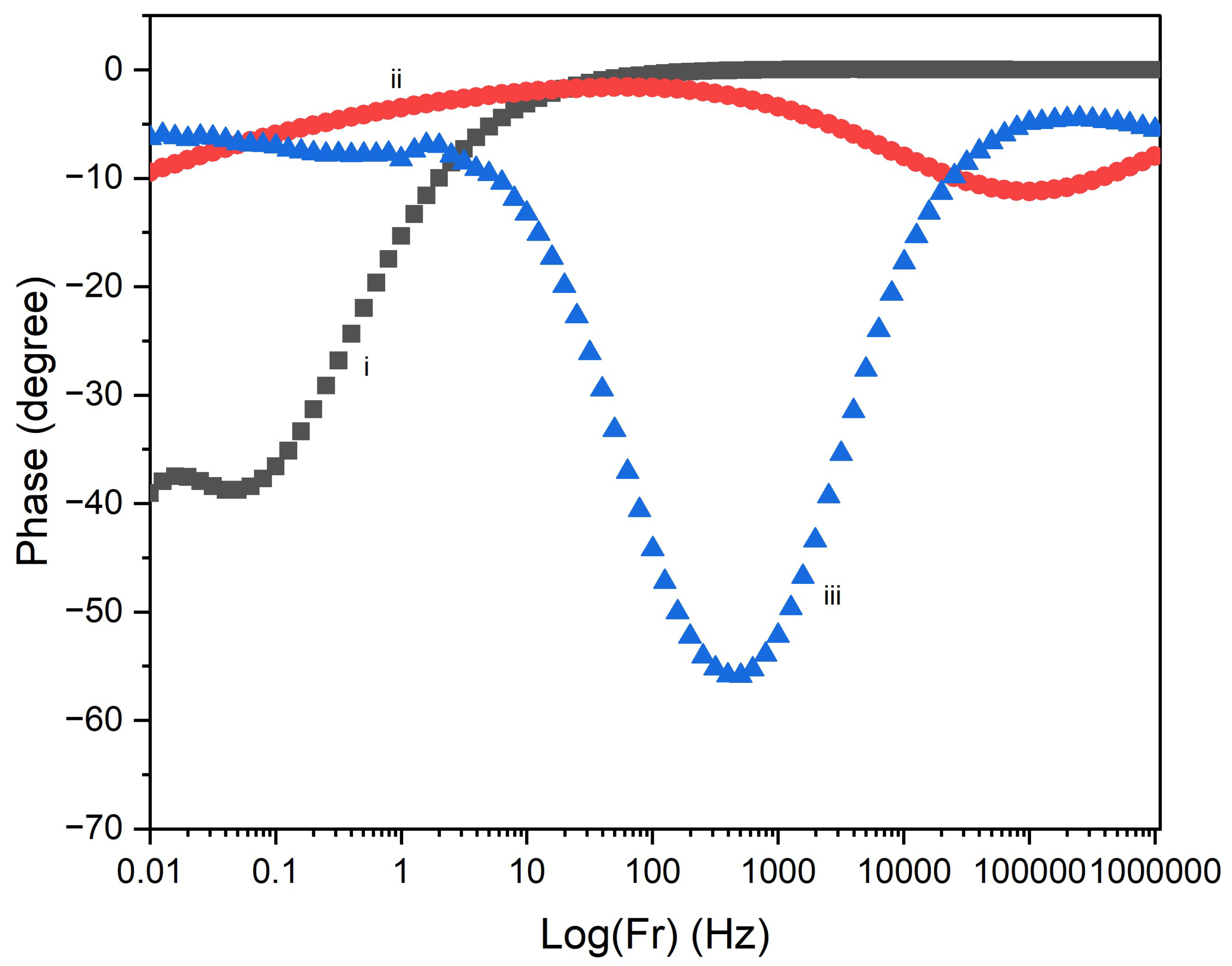

3.3. Electrochemical Properties

| Deposition time | Bulk resistance (Ω) | Porosity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 60 s | 17.7 | 12.2 |

| 600 s | 42.2 | 7.2 |

| 700 s | 61.9 | 4.3 |

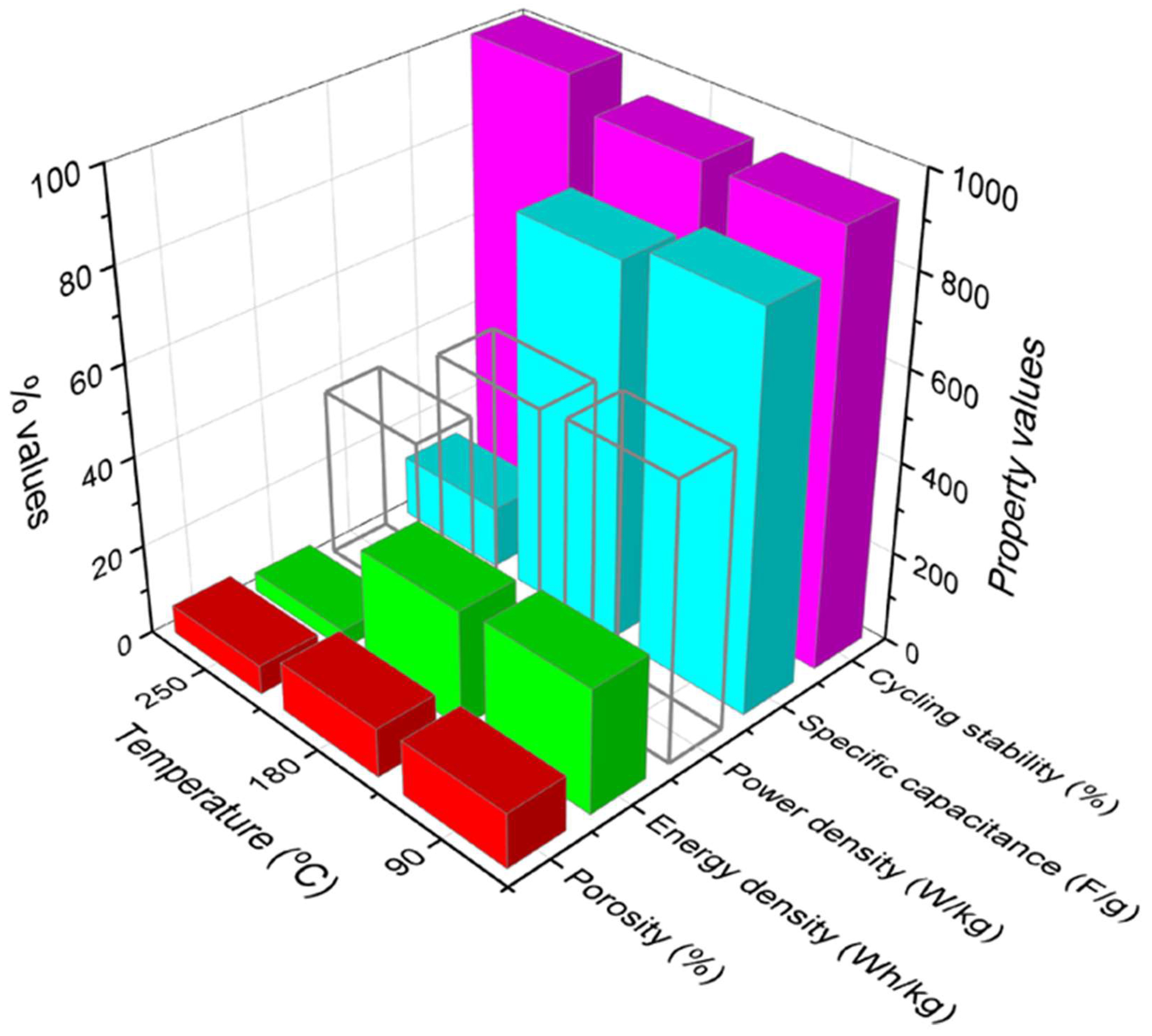

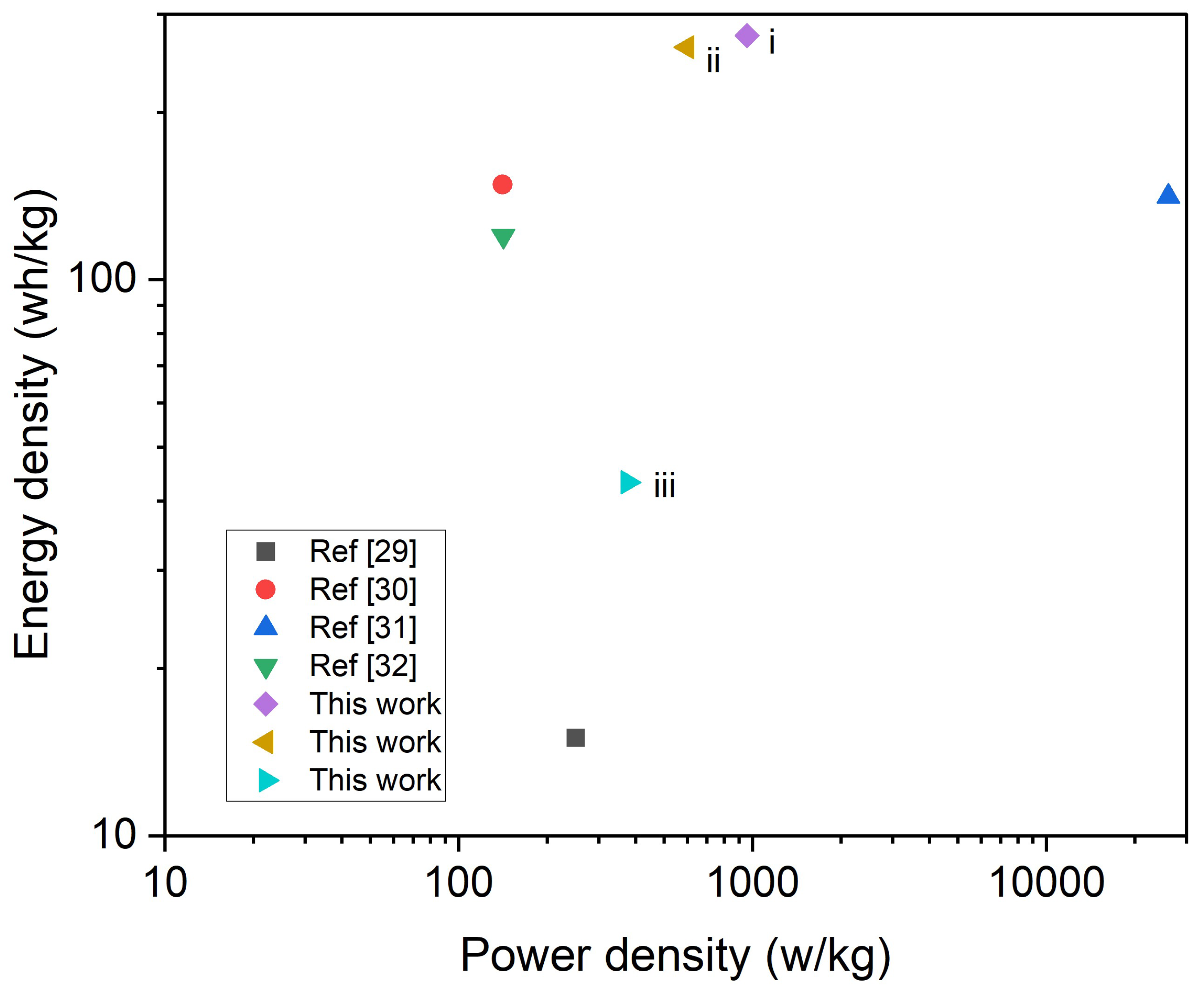

4. Effect of Time and Temperature on the Hybrid Nanocomposite

5. Conclusion

References

- Xu, F.; Wang, H.; Wu, M.; Nan, J.; Li, T.; Cao, S.A. Electrochemical properties of poly (anthraquinonyl imide) s as high-capacity organic cathode materials for Li-ion batteries. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2018, 214, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, D.; Xu, L.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Z.; Kan, B.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Y. A 3D cross-linked graphene-based honeycomb carbon composite with excellent confinement effect of organic cathode material for lithium-ion batteries. Carbon 2020, 157, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.; Sun, X.G.; Dai, S. Organic Cathode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries: Past, Present, and Future. Advanced Energy and Sustainability Research 2021, 2, 2000044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Li, G.; Han, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, F.; Hu, Z.; Cai, T.; Chu, J.; Song, Z. Oxidized indanthrone is a cost-effective and high-performance organic cathode material for rechargeable lithium batteries. Energy Storage Materials 2022, 50, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, W.; Song, E.; Wang, S.; Liu, J. Trinitroaromatic Salts as High-Energy-Density Organic Cathode Materials for Li-Ion Batteries. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, L.; Xu, H.; Song, Y.; He, X. Polyimides as Promising Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Review. Nano-Micro Letters 2023, 15, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Yang, H.; Sui, L.; Jiang, S.; Hou, H. Self-Adhesive Polyimide (PI)@ Reduced Graphene Oxide (RGO)/PI@ Carbon Nanotube (CNT) Hierarchically Porous Electrodes: Maximizing the Utilization of Electroactive Materials for Organic Li-Ion Batteries. Energy Technology 2020, 8, 2000397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, V.T.; Kumar, J.S.; Jain, A. Polymer and ceramic nanocomposites for aerospace applications. Applied Nanoscience 2017, 7, 519–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.C.; Fidalgo-Marijuan, A.; Dias, J.C.; Gonçalves, R.; Salado, M.; Costa, C.M.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Molecular design of functional polymers for organic radical batteries. Energy Storage Materials 2023, 102841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Liu, C.; Sun, X.; Yang, Z.; Kia, H.G.; Peng, H. Aligned carbon nanotube/polymer composite fibers with improved mechanical strength and electrical conductivity. Journal of Materials Chemistry 2012, 22, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Dai, J.; Li, W.; Wei, Z.; Jiang, J. The effects of CNT alignment on electrical conductivity and mechanical properties of SWNT/epoxy nanocomposites. Composites Science and Technology 2008, 68, 1644–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.C.; Liu, M.Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.Q.; Wang, R.; Wang, K.; Wong, Y.K.; Tang, B.Z.; Hong, S.H.; Paik, K.W.; Kim, J.K. Enhanced electrical conductivity of nanocomposites containing hybrid fillers of carbon nanotubes and carbon black. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2009, 1, 1090–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezer Hicyilmaz, A.; Celik Bedeloglu, A. Applications of polyimide coatings: A review. SN Applied Sciences 2021, 3, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lin, J.; Shen, Z.X. Polyaniline (PANi) based electrode materials for energy storage and conversion. Journal of Science: Advanced Materials and Devices 2016, 1, 225–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chougule, M.A.; Pawar, S.G.; Godse, P.R.; Mulik, R.N.; Sen, S.; Patil, V.B. Synthesis and characterization of polypyrrole (PPy) thin films. Soft Nanoscience Letters 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanavičius, A.; Ramanavičienė, A.; Malinauskas, A. Electrochemical sensors based on conducting polymer—polypyrrole. Electrochimica Acta 2006, 51, 6025–6037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooneratne, R.; Iroh, J.O. Polypyrrole Modified Carbon Nanotube/Polyimide Electrode Materials for Supercapacitors and Lithium-ion Batteries. Energies 2022, 15, 9509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zheng, L.; Wang, X.; Yi, L.; Bai, L.; Zhang, X. Polypyrrole/carbon aerogel composite materials for supercapacitor. Journal of Power Sources 2010, 195, 6964–6969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, H.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, F. Synthesis, characterization, and electrochemical behavior of polypyrrole/carbon nanotube composites using organometallic-functionalized carbon nanotubes. Applied Surface Science 2010, 256, 2284–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.X.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.Z.; Bewlay, S.; Liu, H.K. An investigation of polypyrrole-LiFePO4 composite cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochimica Acta 2005, 50, 4649–4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Konstantinov, K.; Zhao, L.; Ng, S.H.; Wang, G.X.; Guo, Z.P.; Liu, H.K. Sulfur-polypyrrole composite positive electrode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries. Electrochimica Acta 2006, 51, 4634–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, H.; Cui, J.; Yao, S.; Shen, X.; Park, T.J.; Kim, J.K. Recent advances in emerging nonaqueous K-ion batteries: from mechanistic insights to practical applications. Energy Storage Materials 2021, 39, 305–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, Y.; Gao, B.; Lv, X.; Si, Z.; Wang, H.G. Conjugated microporous polyarylimides immobilization on carbon nanotubes with improved utilization of carbonyls as cathode materials for lithium/sodium-ion batteries. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2021, 601, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Wang, H.; Lin, J.; Luo, X.; Cao, S.A.; Yang, H. Poly (anthraquinonyl imide) as a high capacity organic cathode material for Na-ion batteries. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2016, 4, 11491–11497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, C.; Hu, Y.; Lin, H.; Kong, W.; Ma, J.; Jin, Z. π-Conjugated polyimide-based organic cathodes with extremely long cycling life for rechargeable magnesium batteries. Energy Storage Materials 2020, 26, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Ji, X.; Hou, S.; Eidson, N.; Fan, X.; Liang, Y.; Deng, T.; Jiang, J.; Wang, C. Azo compounds derived from electrochemical reduction of nitro compounds for high performance Li-ion batteries. Advanced Materials 2018, 30, 1706498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.; Shi, C.; Wu, C.; Yuan, L.; Qiao, H.; Wang, K. Heterostructure Fe 2 O 3 nanorods@ imine-based covalent organic framework for long cycling and high-rate lithium storage. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 1906–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andezai, A.; Iroh, J.O. Influence of the Processing Conditions on the Rheology and Heat of Decomposition of Solution Processed Hybrid Nanocomposites and Implication to Sustainable Energy Storage. Energies 2024, 17, 3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooneratne, R.S. Development of Multicomponent Polyimide-Carbon Nanotube/polypyrrole Composites for Enhanced Energy Storage in Supercapacitor Electrodes. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Cincinnati, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Ma, Y.; Huang, Y. High energy density Li-ion capacitor assembled with all graphene-based electrodes. Carbon 2015, 92, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Ji, X.; Fan, X.; Gao, T.; Suo, L.; Wang, F.; Sun, W.; Chen, J.; Chen, L.; Han, F.; Miao, L. Flexible aqueous Li-ion battery with high energy and power densities. Advanced Materials 2017, 29, 1701972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajuria, J.; Arnaiz, M.; Botas, C.; Carriazo, D.; Mysyk, R.; Rojo, T.; Talyzin, A.V.; Goikolea, E. Graphene-based lithium ion capacitor with high gravimetric energy and power densities. Journal of Power Sources 2017, 363, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).