4.1. Cyclic Voltammetry

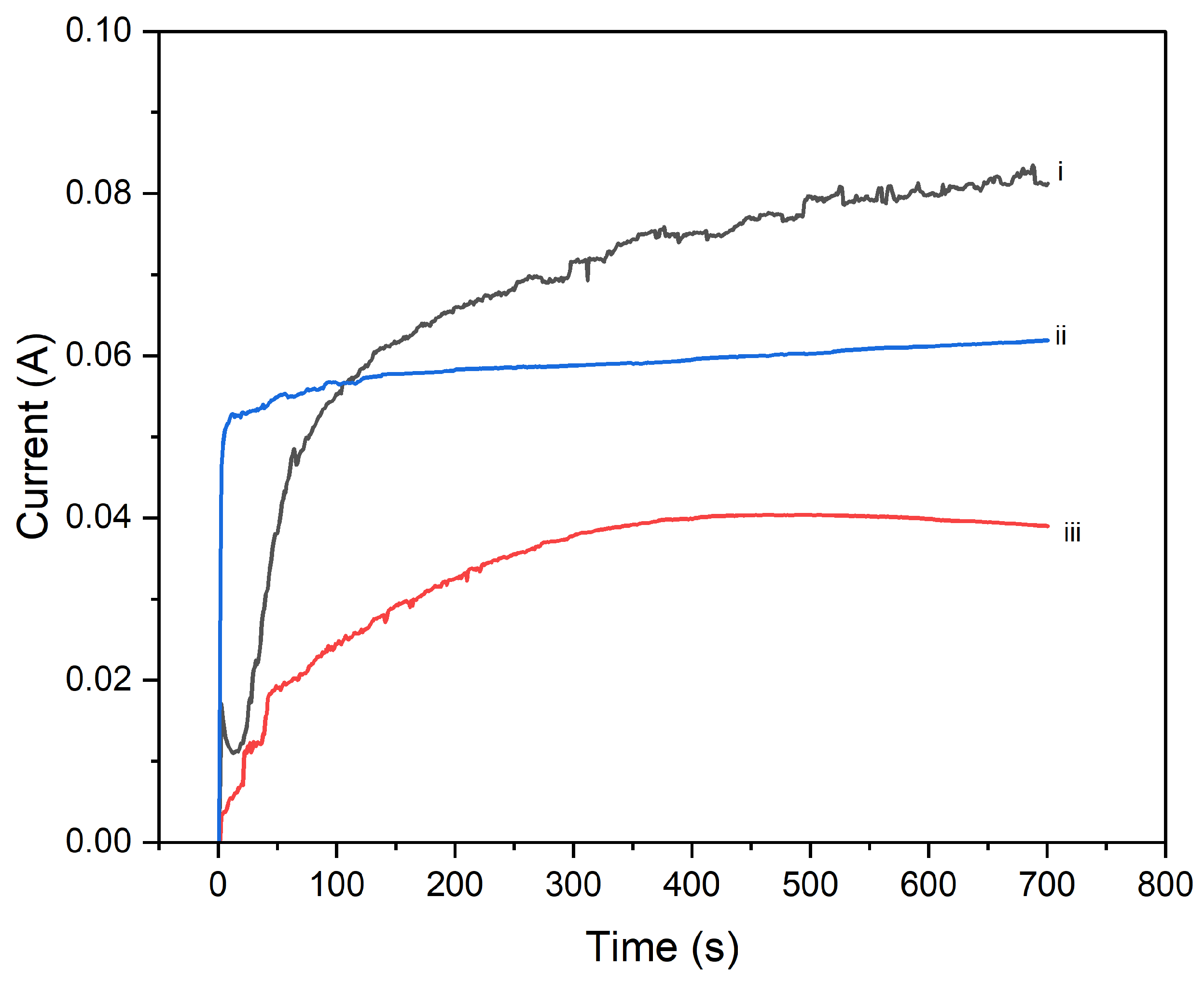

Figure 3 shows the transient current–time curves obtained during the potentiostatic electrochemical polymerization of pyrrole onto the composite PI/CNTs working electrodes processed at

90°C, 180°C, and 250°C for 700 seconds of deposition time. The composite processed at

90°C exhibits the highest steady-state current, reaching approximately

0.08 A, indicating that it forms the most efficient PPy layer for ion transport and charge transfer. In contrast, the

180°C condition stabilizes at a lower current of

0.04 A, suggesting a denser structure with reduced ion diffusion. The

250°C processing stabilizes at around

0.06 A, performing better than

180°C but still lower than

90°C. This suggests that, while

250°C creates a stable PPy layer, it does not achieve the same level of ion mobility and electrochemical efficiency as

90°C. Overall,

90°C proves to be the optimal temperature for polymerization, delivering the best electrochemical performance for energy storage applications.

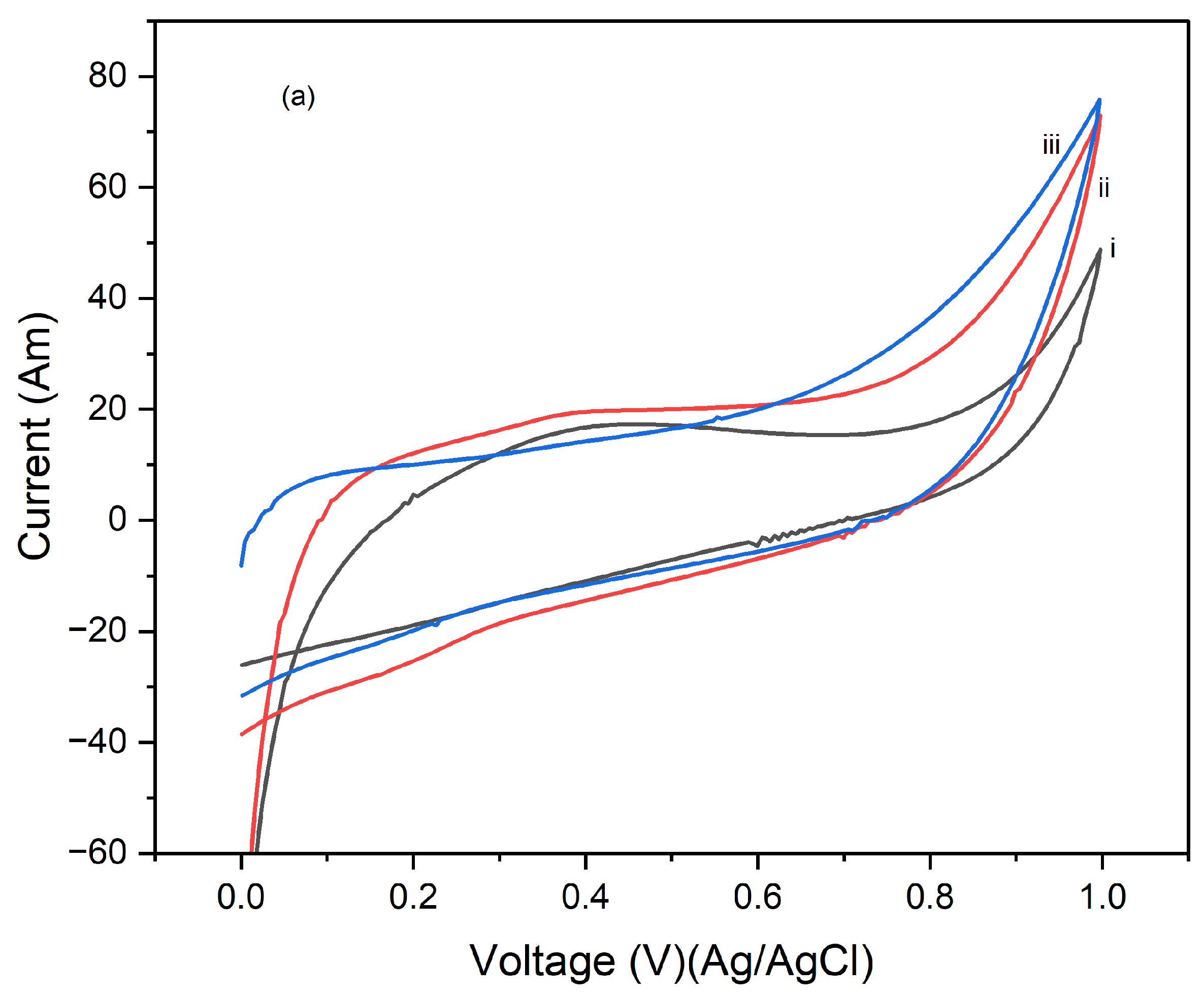

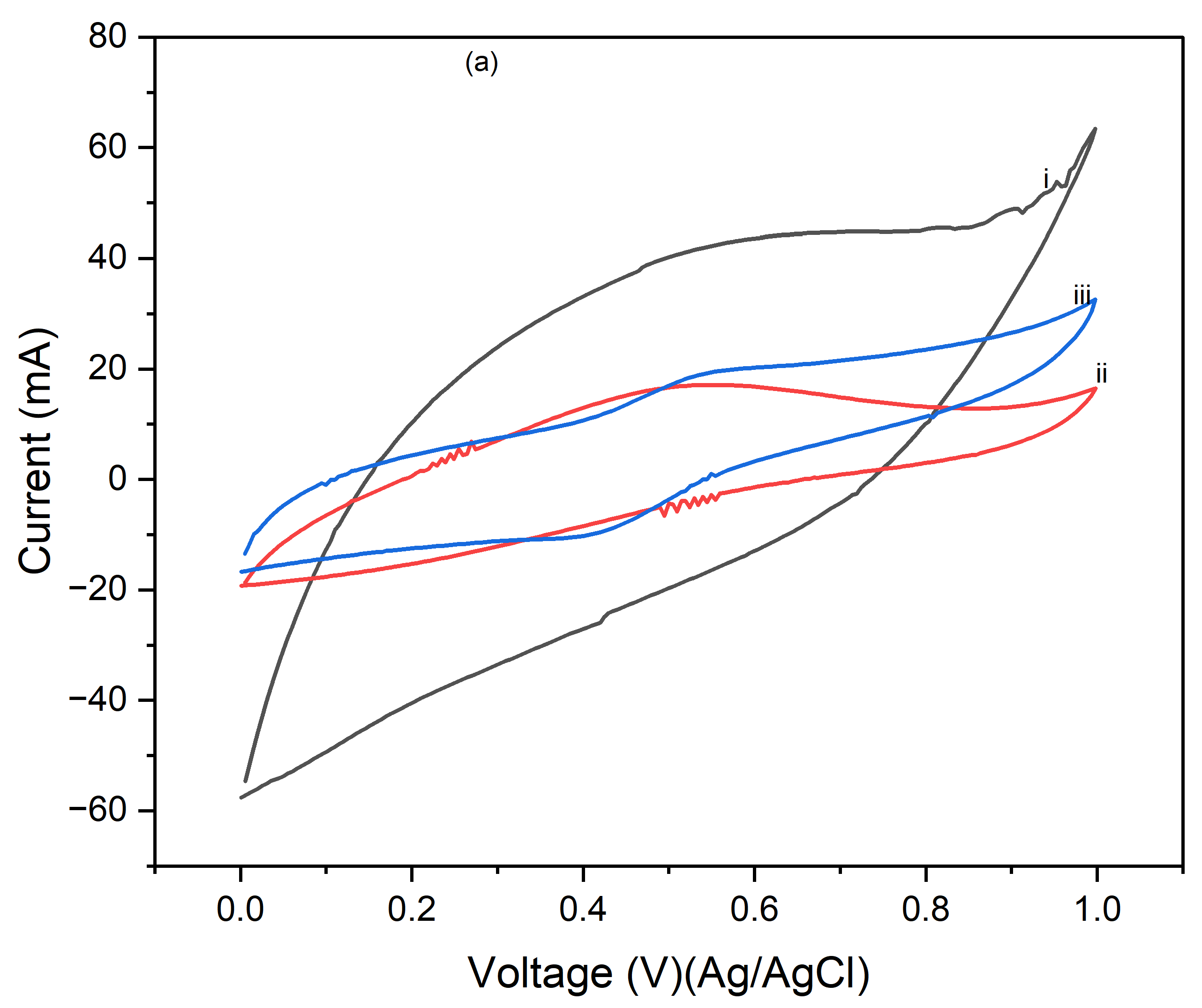

Figure 4 presents the cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of PI/CNTs hybrid nanocomposites processed at 90 °C, followed by the electrodeposition of polypyrrole (PPy). The measurements were conducted using an Ag/AgCl reference electrode and a graphite rod counter electrode, with CV tests run at scan rates of 5 mV/s, 10 mV/s, and 25 mV/s.

Figure 2a shows the results after 1 cycle, the peak current increases with the increase in the scan rate from 5 mV/s to 25 mV/s, indicating typical capacitive behavior where faster scan rates allow less time for ion diffusion, leading to higher current peaks.

Figure 4b, displaying the CVs after 5 cycles, follows a similar trend, with increased peak currents at higher scan rates.

Figure 4c, shows the CV results after 10 cycles, continuing this trend, with further increased peak currents as the scan rate increases. Compared to the 1 and 5-cycle data, the enhanced current response indicates that the electrode's performance improves with continued cycling, due to forming a more stable and efficient electrochemical interface.

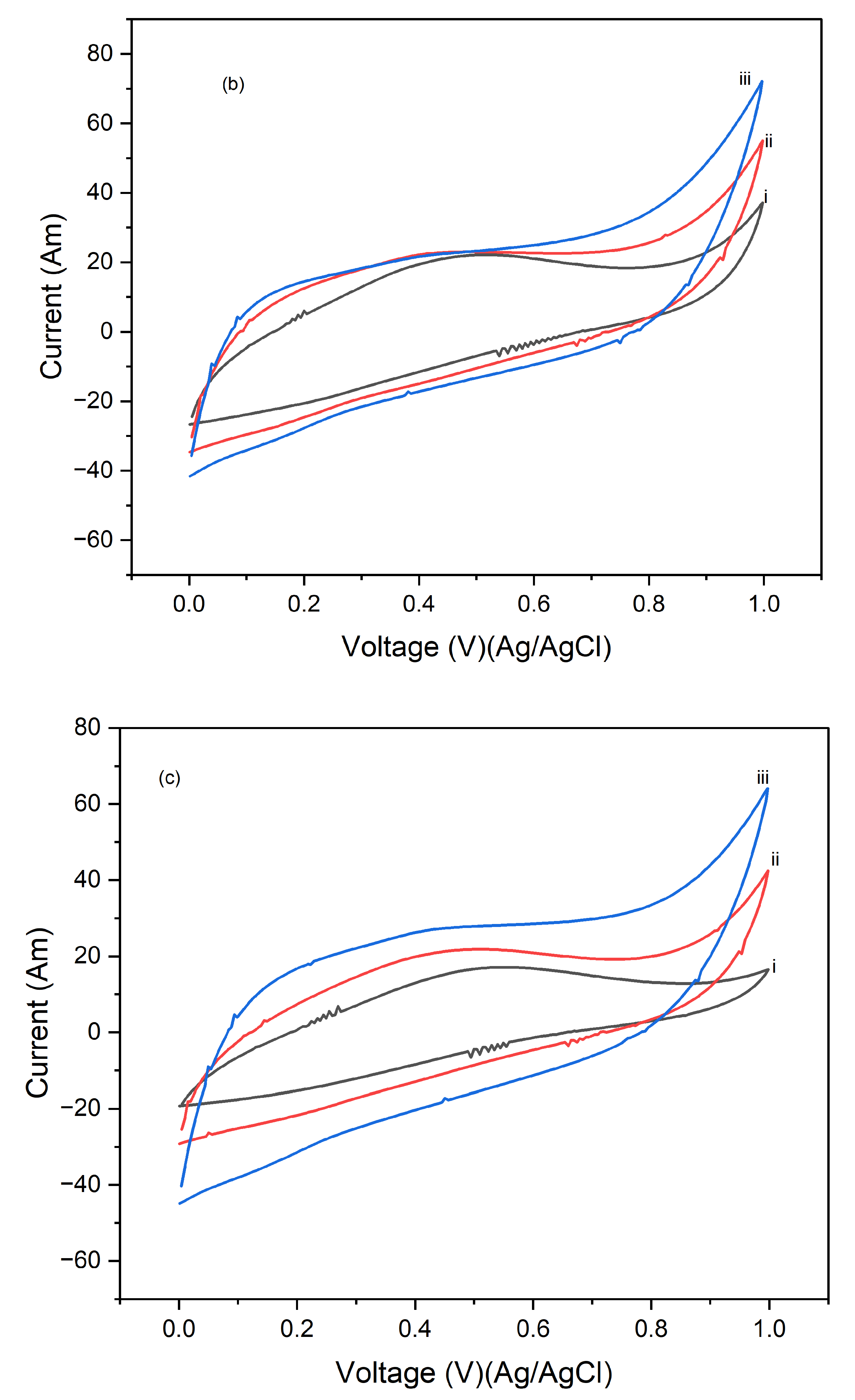

Figure 5 presents the cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of PI/CNTs hybrid nanocomposites processed at 180 °C, followed by the electrodeposition of polypyrrole (PPy). The CV measurements were conducted using an Ag/AgCl reference electrode and a graphite rod counter electrode at scan rates of 5 mV/s, 10 mV/s, and 25 mV/s.

Figure 5a shows the results after 1 cycle, the peak current increases as the scan rate rises from 5 mV/s to 25 mV/s, indicating typical capacitive behavior where faster scan rates lead to higher current peaks due to reduced time for ion diffusion.

Figure 5b, displaying the CVs after 5 cycles, shows a consistent trend of increasing peak current with higher scan rates, with an overall higher current response compared to the 1-cycle data.

Figure 5c illustrates the CV results after 10 cycles, where the peak currents continue to increase with higher scan rates. The current response is further enhanced compared to the 5-cycle data, indicating that the electrode's performance continues to improve with repeated cycling, potentially due to the formation of a more stable and efficient electrochemical interface. This suggests that repeated cycling improves the electrode's electrochemical performance by enhancing the utilization of active material and stabilizing the electrode surface.

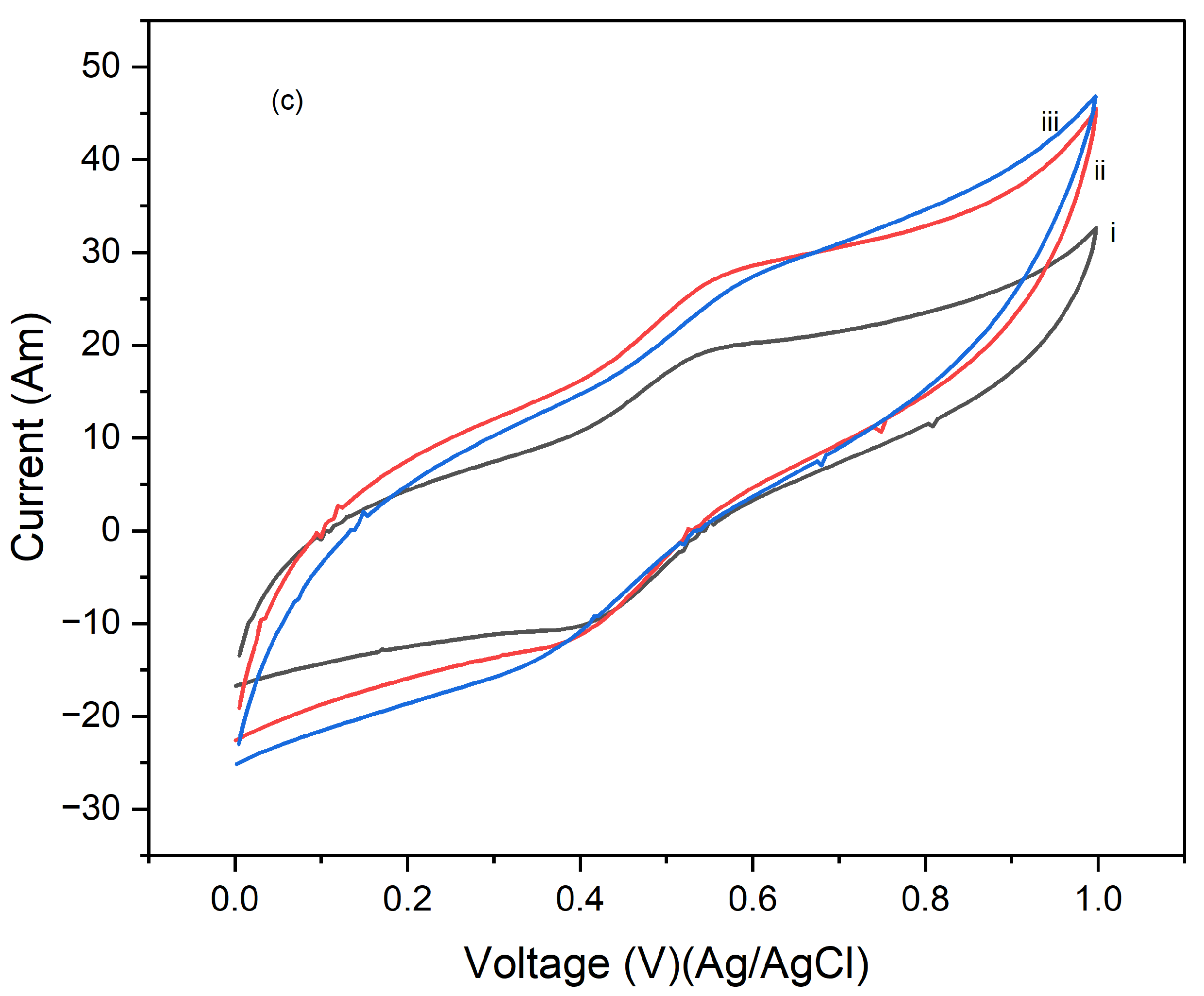

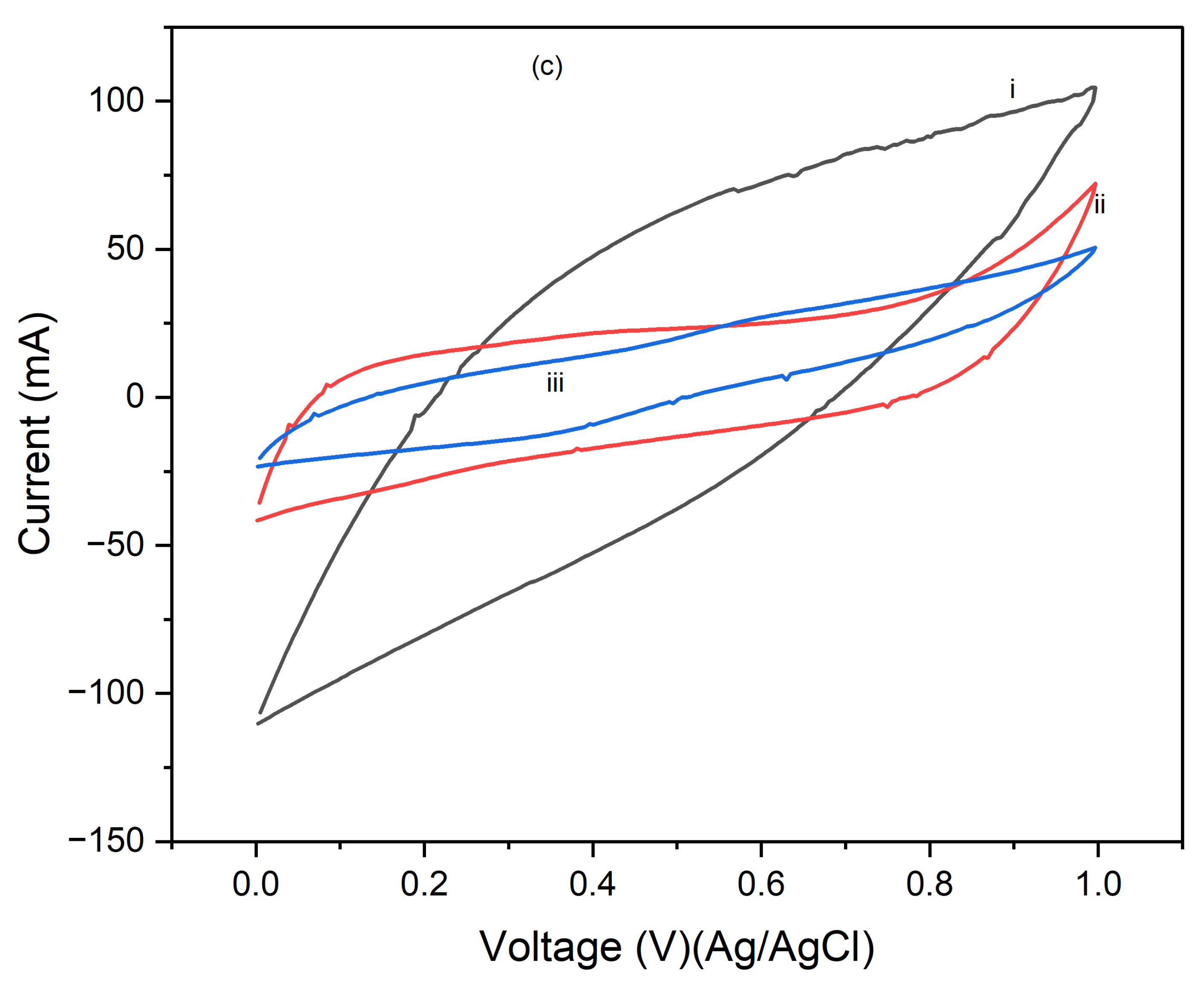

Figure 6 presents the cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of PI/CNTs hybrid nanocomposites processed at 250 °C, followed by the electrodeposition of polypyrrole (PPy). The CV measurements were conducted using an Ag/AgCl reference electrode and a graphite rod counter electrode at a scan rate of 5 mV/s. In

Figure 6a, after 1 cycle, the peak current increases with the scan rate, indicating typical capacitive behavior. However, the current response is lower compared to composites processed at lower temperatures, suggesting a reduction in electrochemical performance possibly due to the high processing temperature affecting the material's structure.

Figure 6b shows the CVs after 5 cycles, where the peak currents are slightly higher than in the 1-cycle data, indicating that repeated cycling improves the electrode's performance. Despite this, the overall current response remains lower than that of composites processed at lower temperatures, implying that the high processing temperature might have negatively impacted the material's active surface area or conductivity.

Figure 6c illustrates the CV results after 10 cycles, showing a continued increase in peak currents with the scan rate, though the overall enhancement in performance with cycling is modest. This suggests that the high processing temperature may limit the material's ability to achieve optimal electrochemical performance. These results highlight that while the PI/CNTs hybrid nanocomposites processed at 250 °C exhibit capacitive behavior and some improvement with cycling, the high processing temperature adversely affected the material's structure, leading to lower overall electrochemical performance compared to composites processed at lower temperatures. This emphasizes the importance of processing conditions for the best possible performance in energy storage applications.

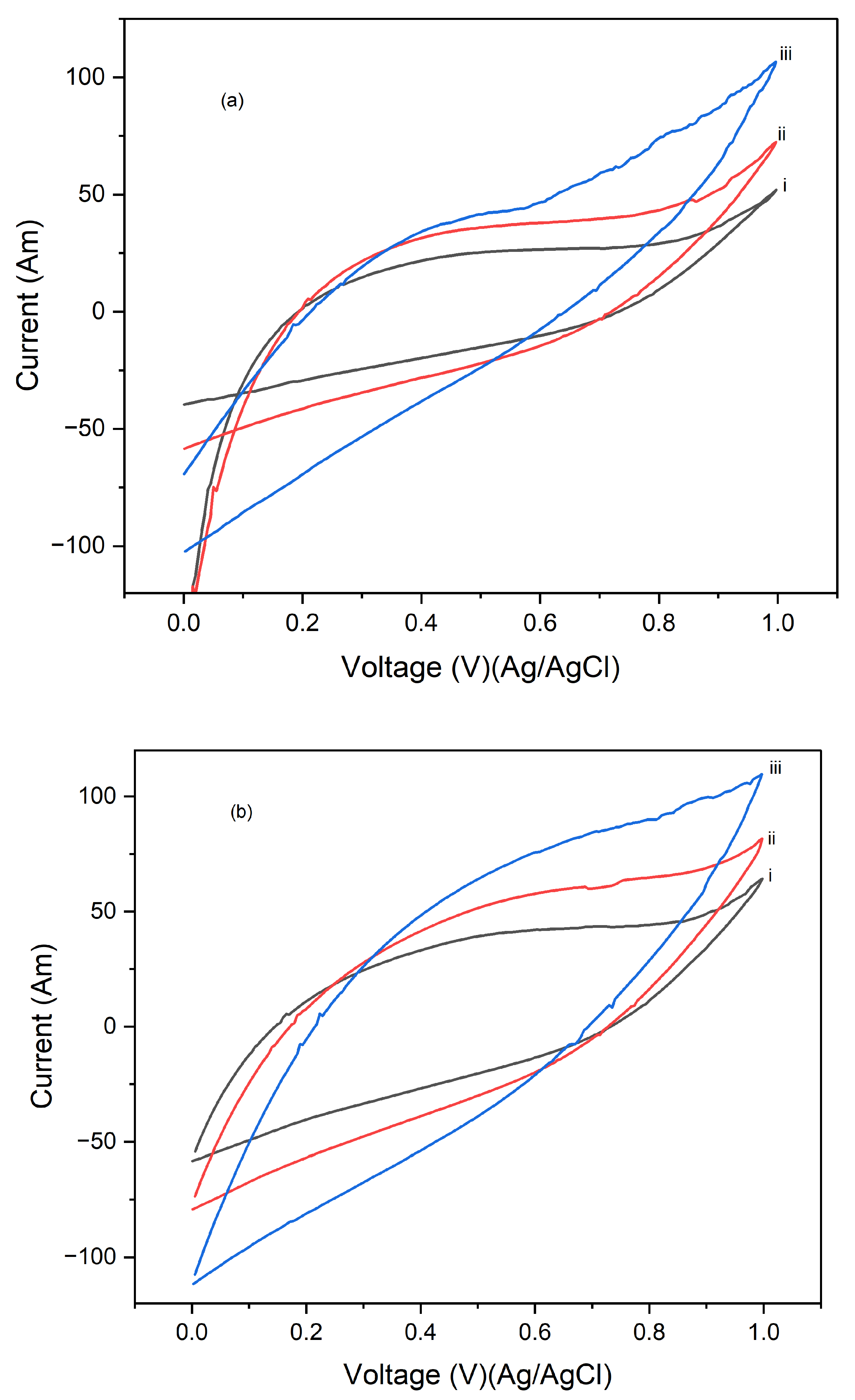

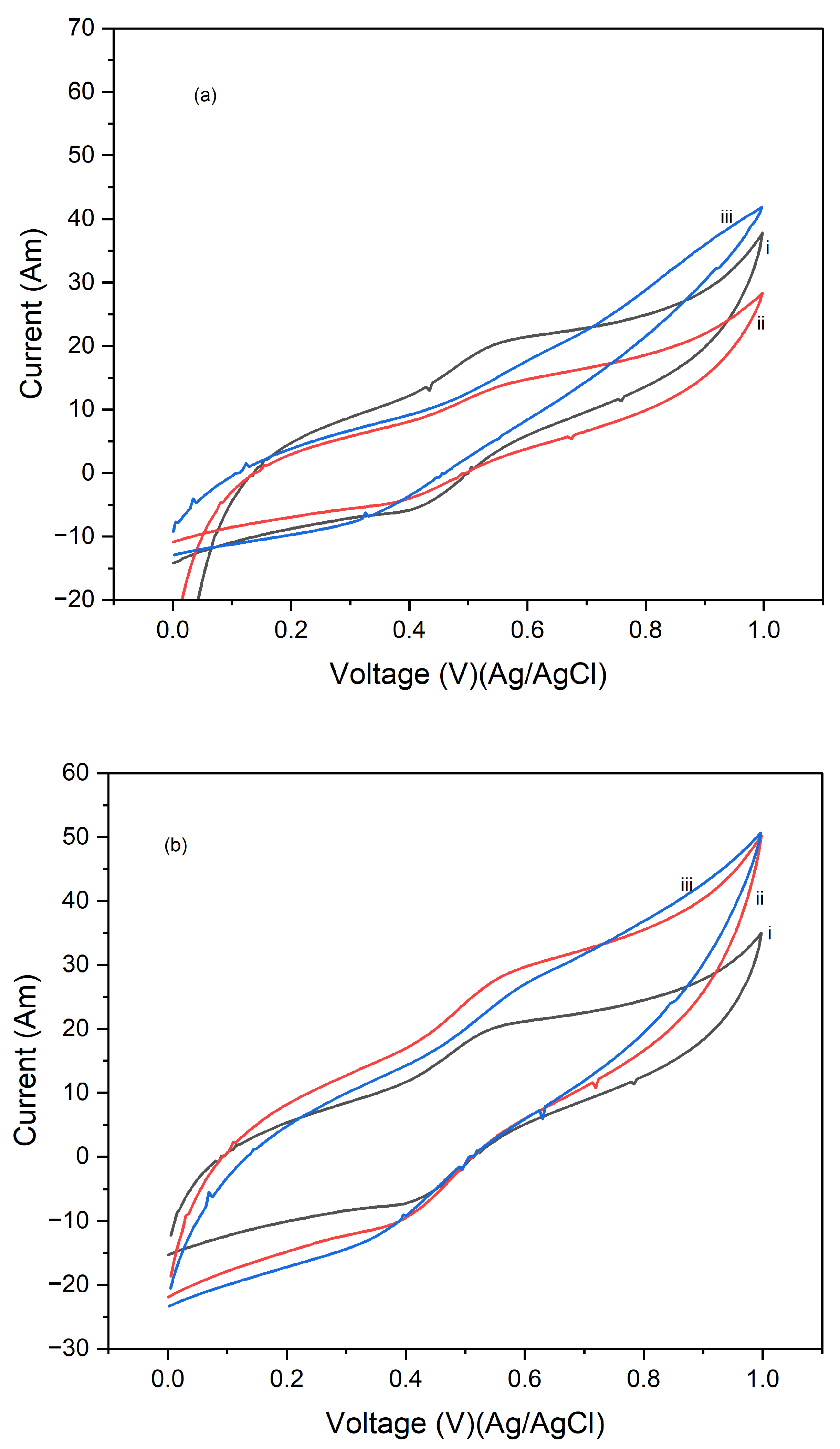

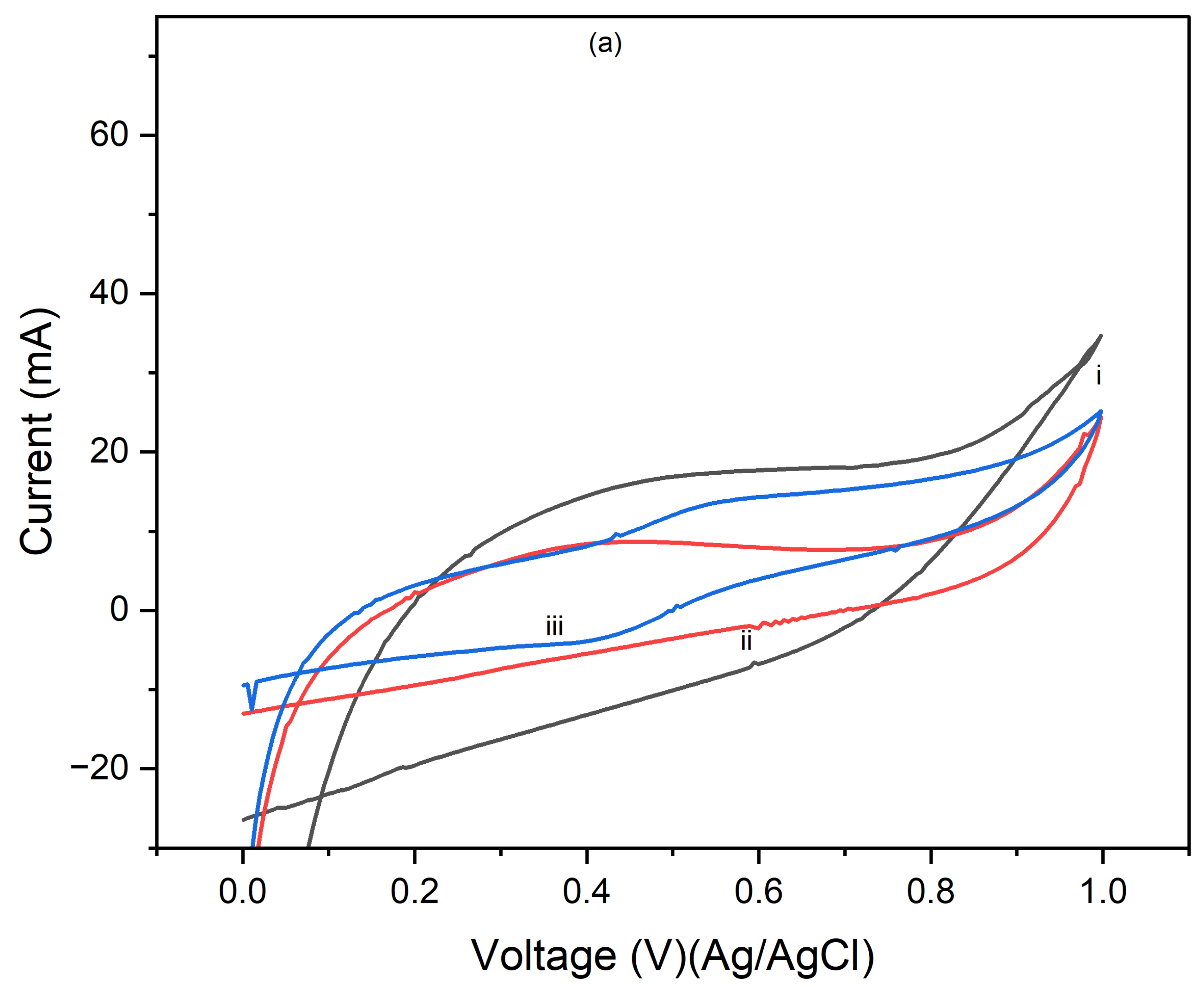

Figure 7 displays the cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of PI/CNTs hybrid nanocomposites processed at three different temperatures 90 °C, 180 °C, and 250 °C followed by the electrodeposition of polypyrrole (PPy). The CV measurements were conducted using an Ag/AgCl reference electrode and a graphite rod counter electrode for 1 cycle at scan rates of 5 mV/s, 10 mV/s, and 25 mV/s. In

Figure 7a, which shows the CV results at a scan rate of 5 mV/s, the composites processed at 90 °C exhibit the highest peak current, indicating superior capacitive behavior and electrochemical performance. The peak currents decrease for the composites processed at 180 °C and further decrease for those processed at 250 °C, suggesting that higher processing temperatures may negatively impact the electrochemical properties, possibly due to structural changes in the material that reduces its conductivity or active surface area.

Figure 7b, which displays the CVs at a scan rate of 10 mV/s, shows a similar trend where the composites processed at 90 °C continue to exhibit the highest peak current, followed by those processed at 180 °C and 250 °C. Although the increased scan rate leads to higher current peaks, the relative performance trend remains consistent, with lower processing temperatures yielding better electrochemical results.

Figure 7c, illustrating the CVs at a scan rate of 25 mV/s, further reinforces this pattern. The composites processed at 90 °C show the best electrochemical performance, with the highest peak currents, while the performance decreases with increasing processing temperature, with the composites processed at 250 °C showing the lowest peak currents. This consistent pattern across different scan rates underscores the significant impact of processing temperature on the electrochemical performance of the composites, highlighting that the 90 °C processing condition consistently produces the best results, making it the best temperature for preparing these composites for high-performance energy storage applications. Conversely, higher temperatures may lead to detrimental structural changes that reduce the effectiveness of the material.

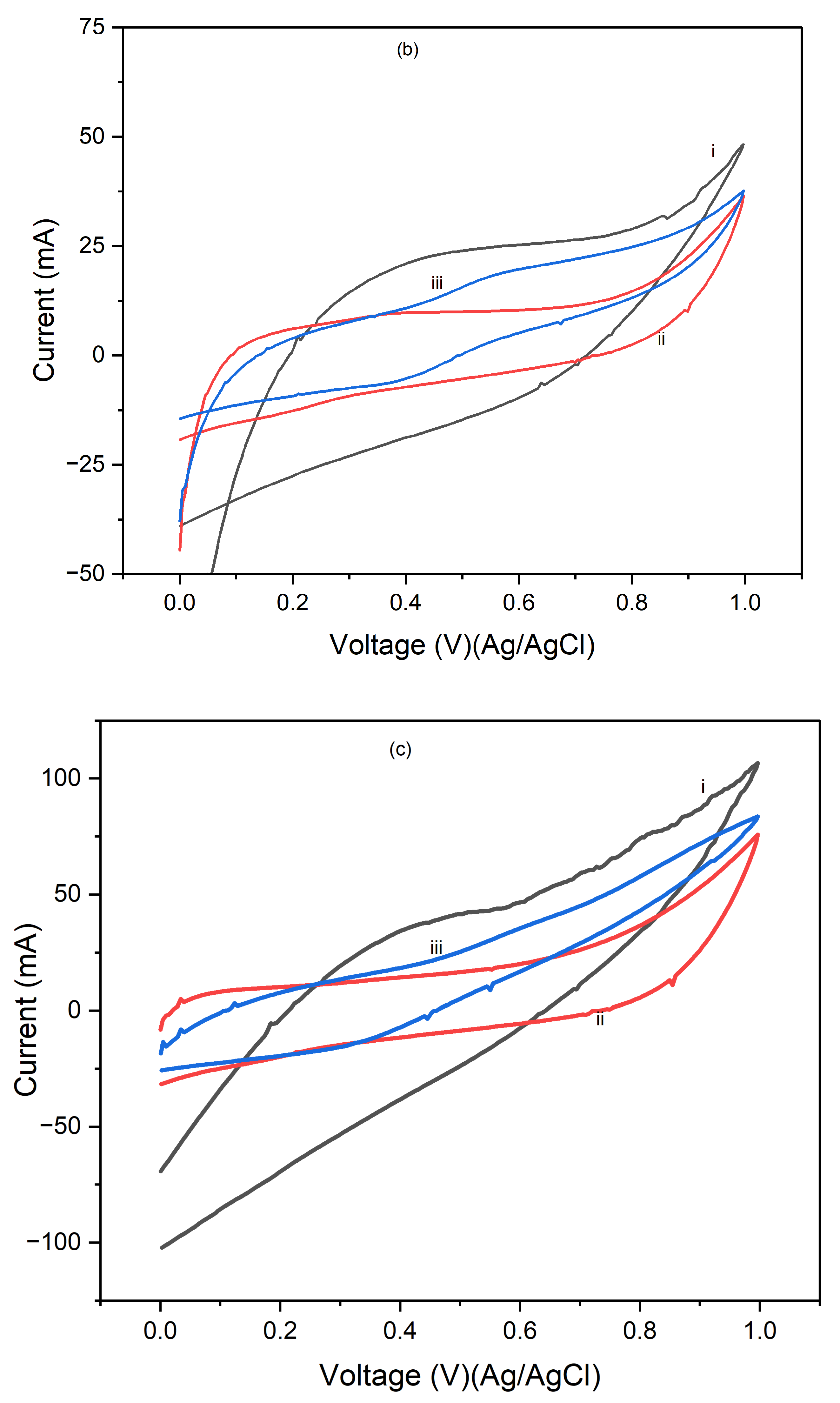

Figure 8 shows the cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of PI/CNTs hybrid nanocomposites processed at 90 °C, 180 °C, and 250 °C, followed by the electrodeposition of polypyrrole (PPy). The CV measurements were conducted using an Ag/AgCl reference electrode and a graphite rod counter electrode after 5 cycles, with scan rates of 5 mV/s, 10 mV/s, and 25 mV/s.

Figure 8a shows the CVs at 5 mV/s, the composite processed at 90 °C demonstrates the highest peak current, indicating superior electrochemical performance. As the processing temperature increases to 180 °C and 250 °C, the peak current decreases, suggesting a reduction in electrochemical activity, likely due to structural changes that negatively impact the material's conductivity or surface area.

Figure 8b, the CVs at 10 mV/s, shows a consistent trend where the 90 °C processed composite again exhibits the highest peak current, followed by the 180 °C and 250 °C samples. The higher scan rate leads to increased currents overall, but the decline in performance with rising temperature remains evident.

Figure 8c shows the CVs at 25 mV/s, the composite processed at 90 °C continues to exhibit the best electrochemical performance with the highest peak currents, while the composites processed at 180 °C and 250 °C show progressively lower currents. This consistent pattern across different scan rates emphasizes the significant impact of processing temperature on the electrochemical behavior of the composites, highlighting that the 90 °C processing condition provides the best performance, whereas higher temperatures seem to adversely affect the material's structure and efficiency.

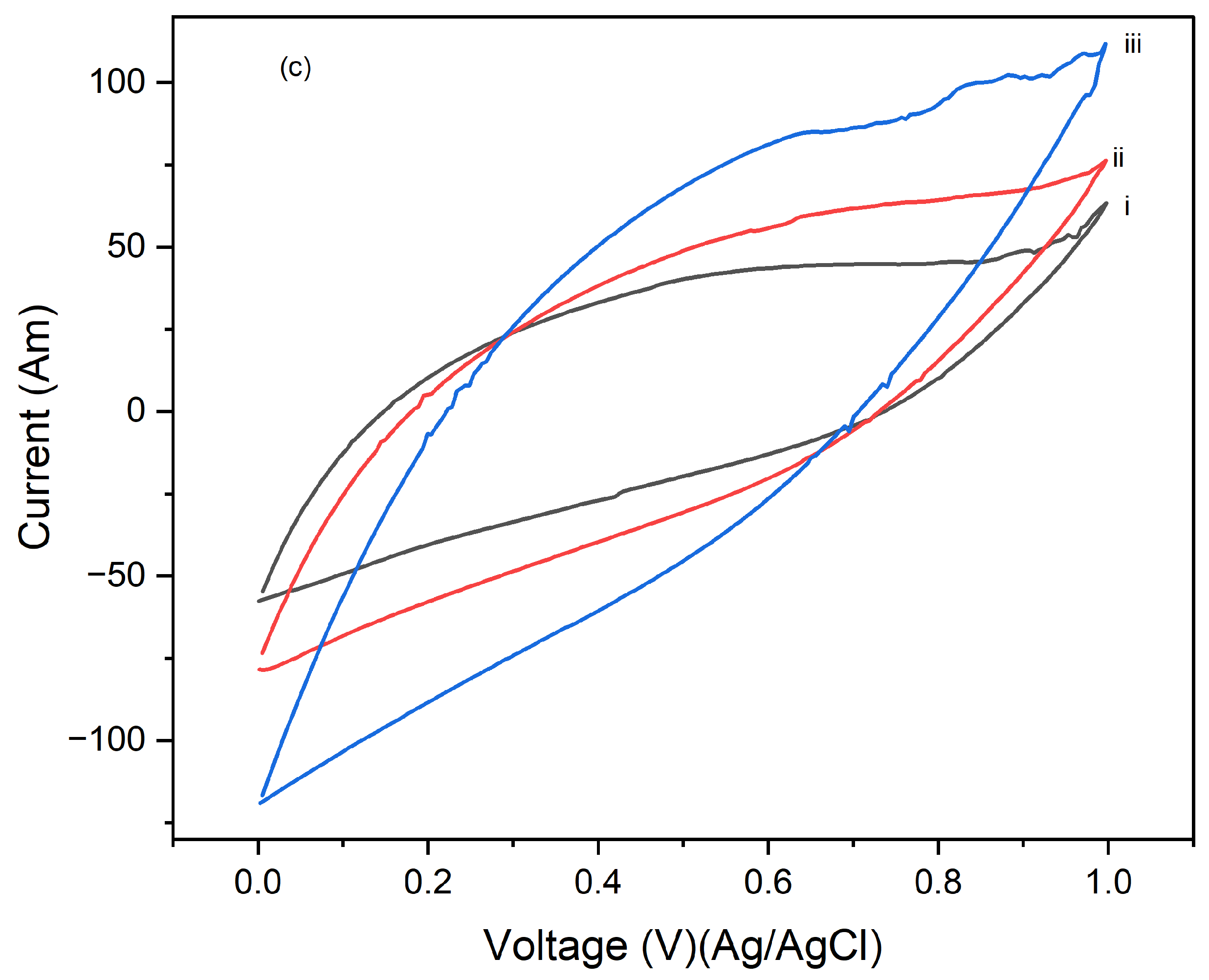

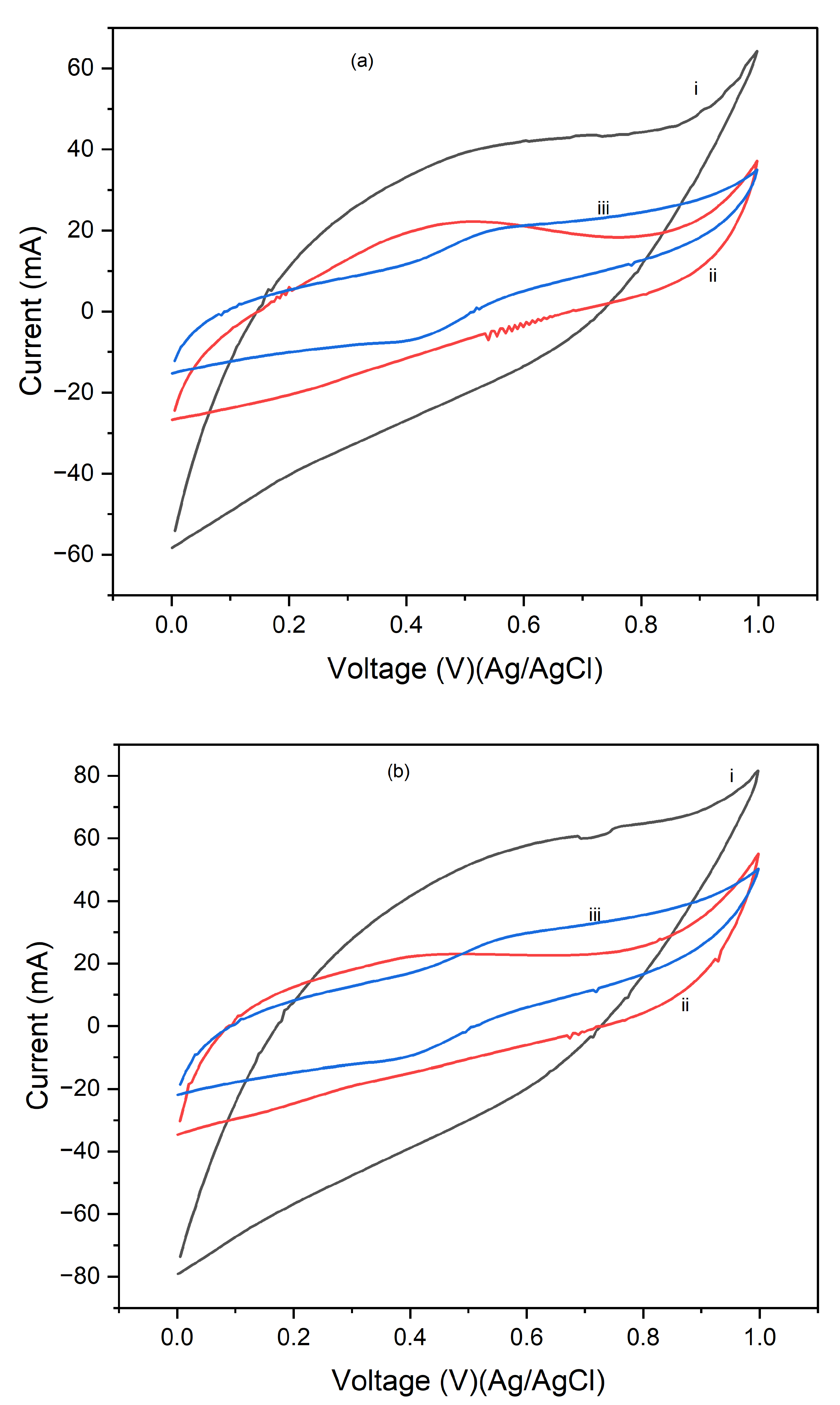

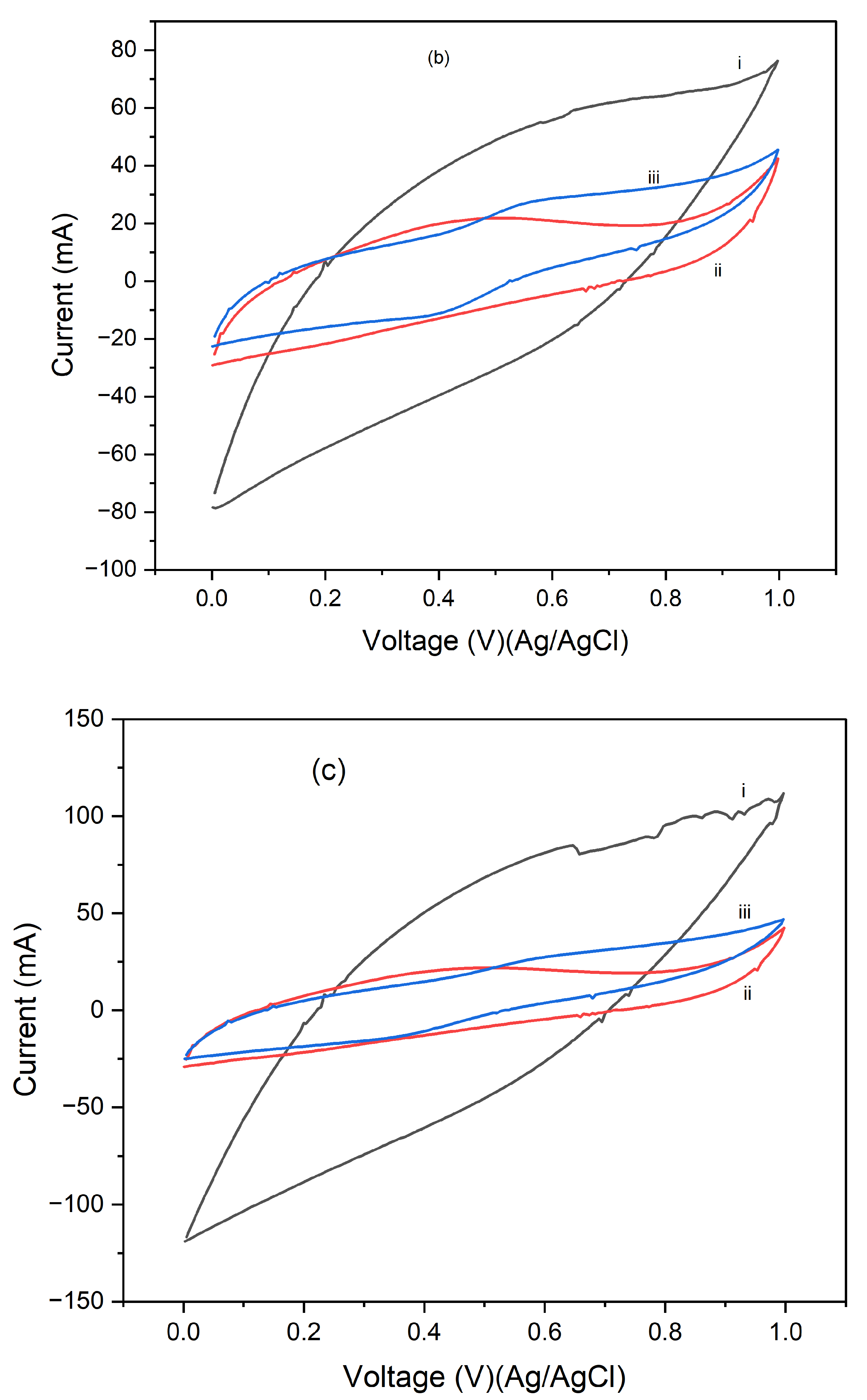

Figure 9 presents the cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of PI/CNTs hybrid nanocomposites processed at 90 °C, 180 °C, and 250 °C, followed by the electrodeposition of polypyrrole (PPy). The CV measurements were conducted using an Ag/AgCl reference electrode and a graphite rod counter electrode after 10 cycles, with scan rates of 5 mV/s, 10 mV/s, and 25 mV/s.

Figure 9a, shows the CVs at 5 mV/s, the composite processed at 90 °C demonstrates the highest peak current, indicating superior electrochemical performance. As the processing temperature increases to 180 °C and 250 °C, the peak currents decrease, suggesting a reduction in electrochemical activity, likely due to structural changes that negatively impact the material's conductivity and active surface area.

Figure 9b, which presents the CVs at 10 mV/s, continues this trend, with the 90 °C processed composite showing the highest peak current, followed by the 180 °C and 250 °C samples. Although the increase in scan rate results in higher current peaks overall, the decline in performance with increasing temperature remains consistent.

Figure 9c, displaying the CVs at 25 mV/s, further reinforces this pattern, with the composite processed at 90 °C demonstrating the best electrochemical performance and the highest peak currents. The performance decreases with increasing processing temperature, with the 250 °C sample showing the lowest peak currents. This consistent pattern across different scan rates and cycles highlights that the PI/CNTs hybrid nanocomposites processed at 90 °C consistently exhibits the best electrochemical performance, making it the optimal temperature for preparing these composites for high-performance energy storage applications. Conversely, higher processing temperatures seem to negatively impact the material's structure, leading to lower overall electrochemical performance.

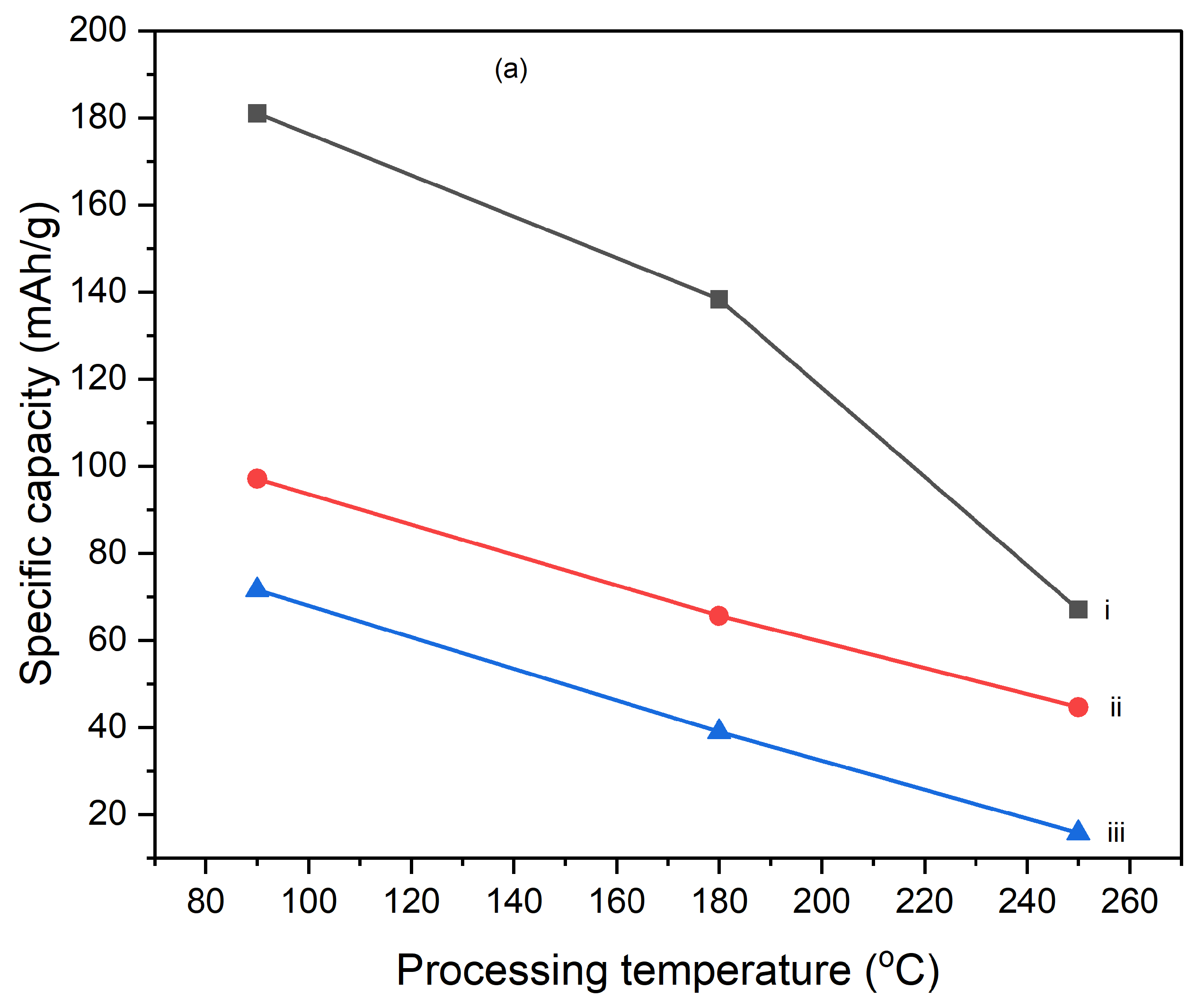

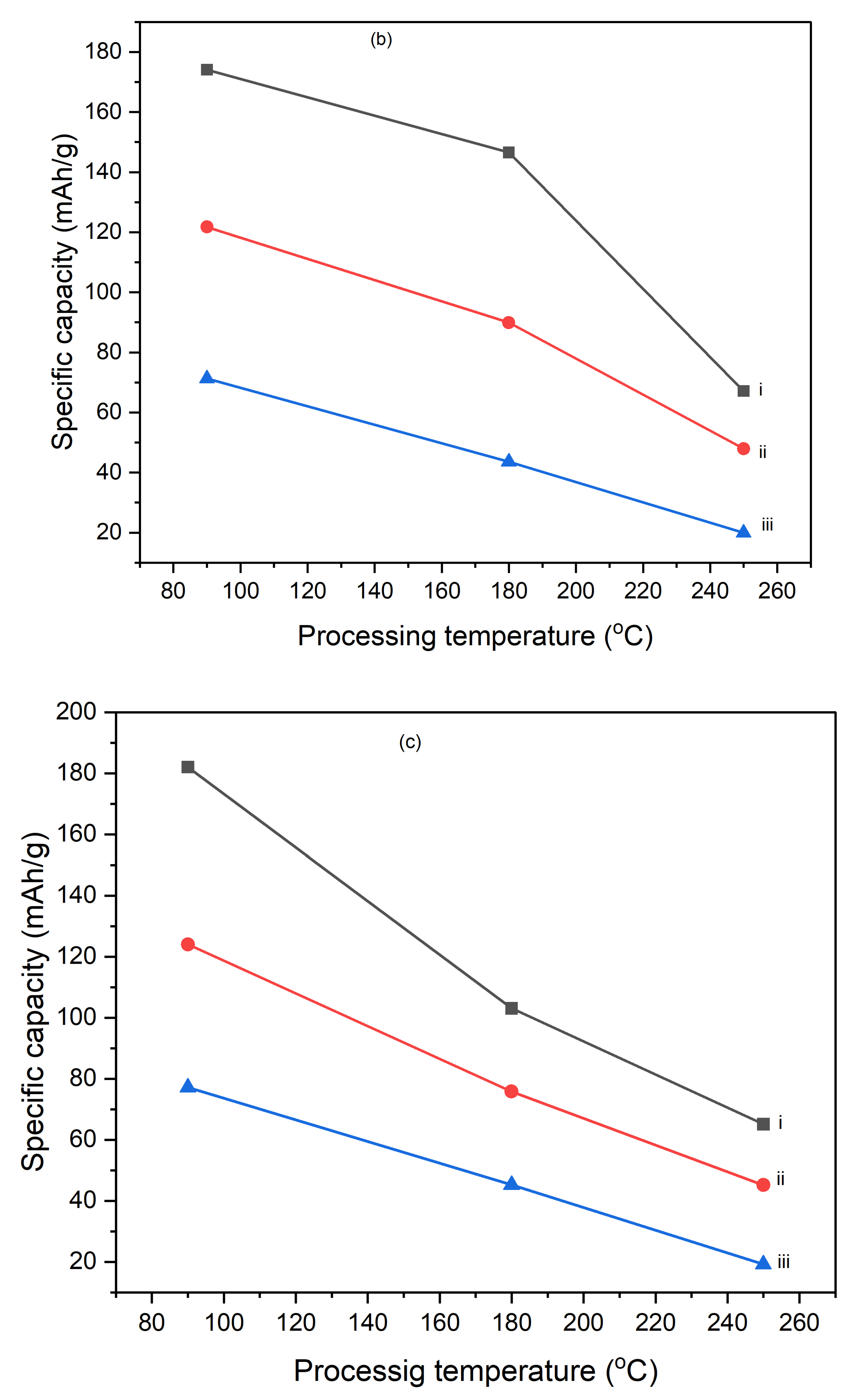

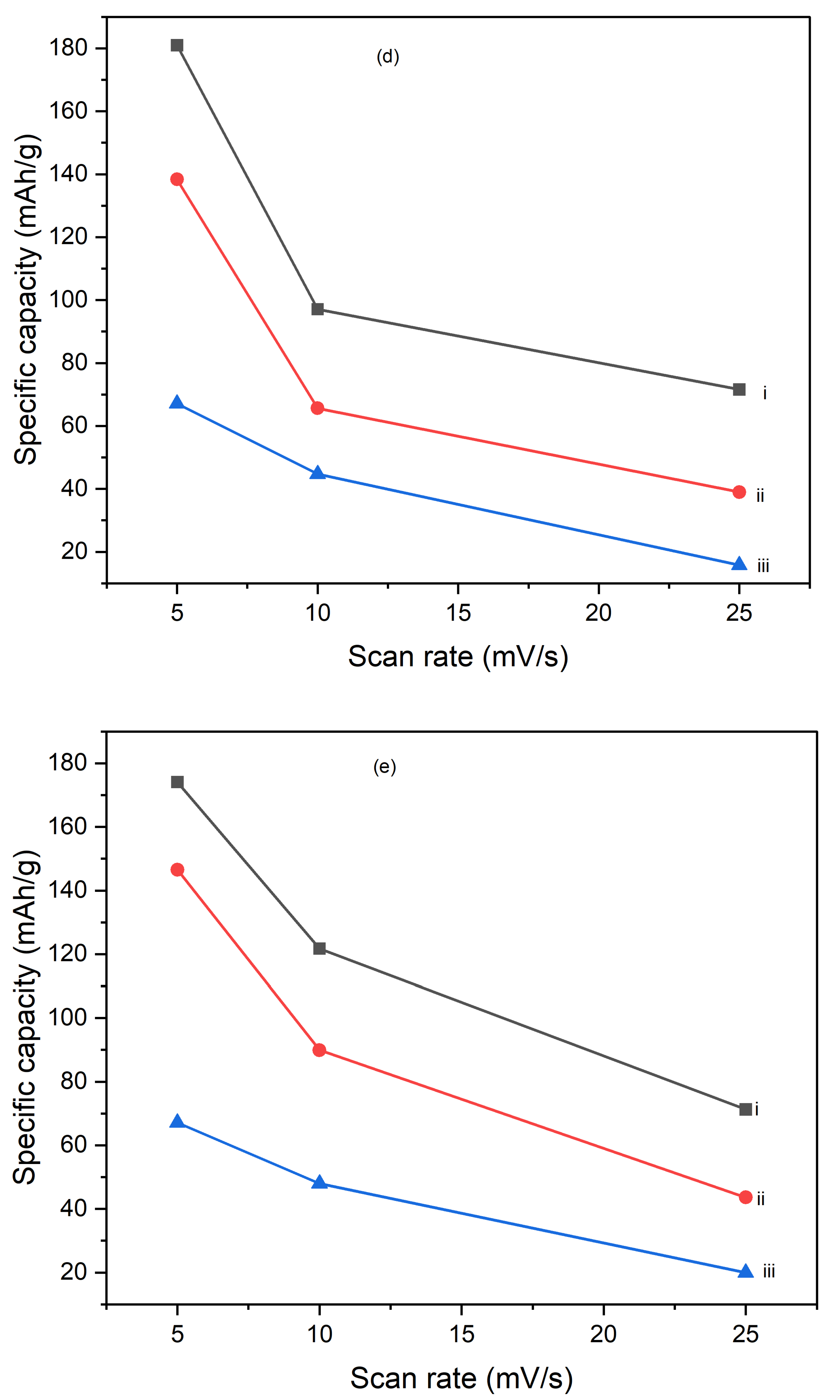

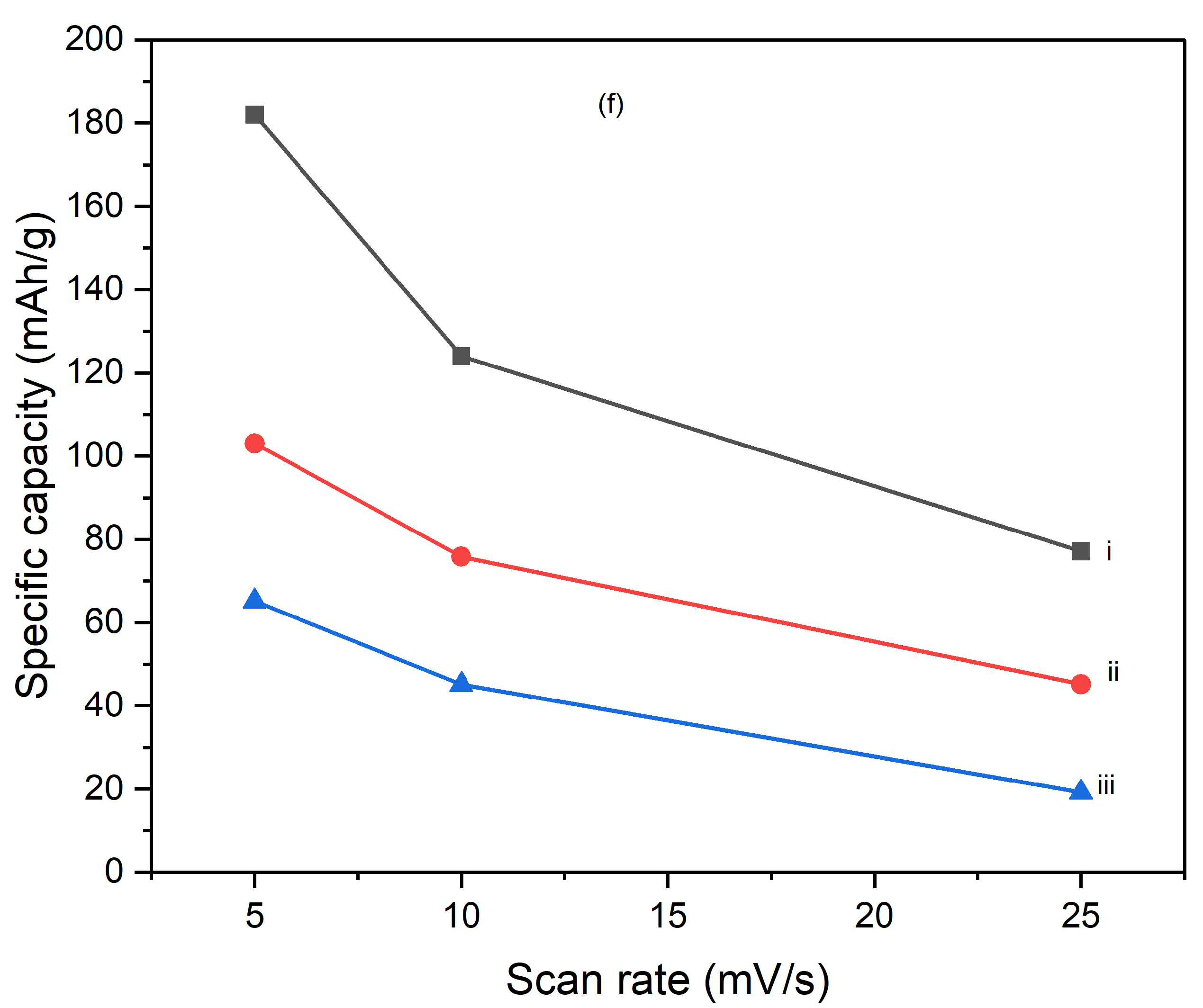

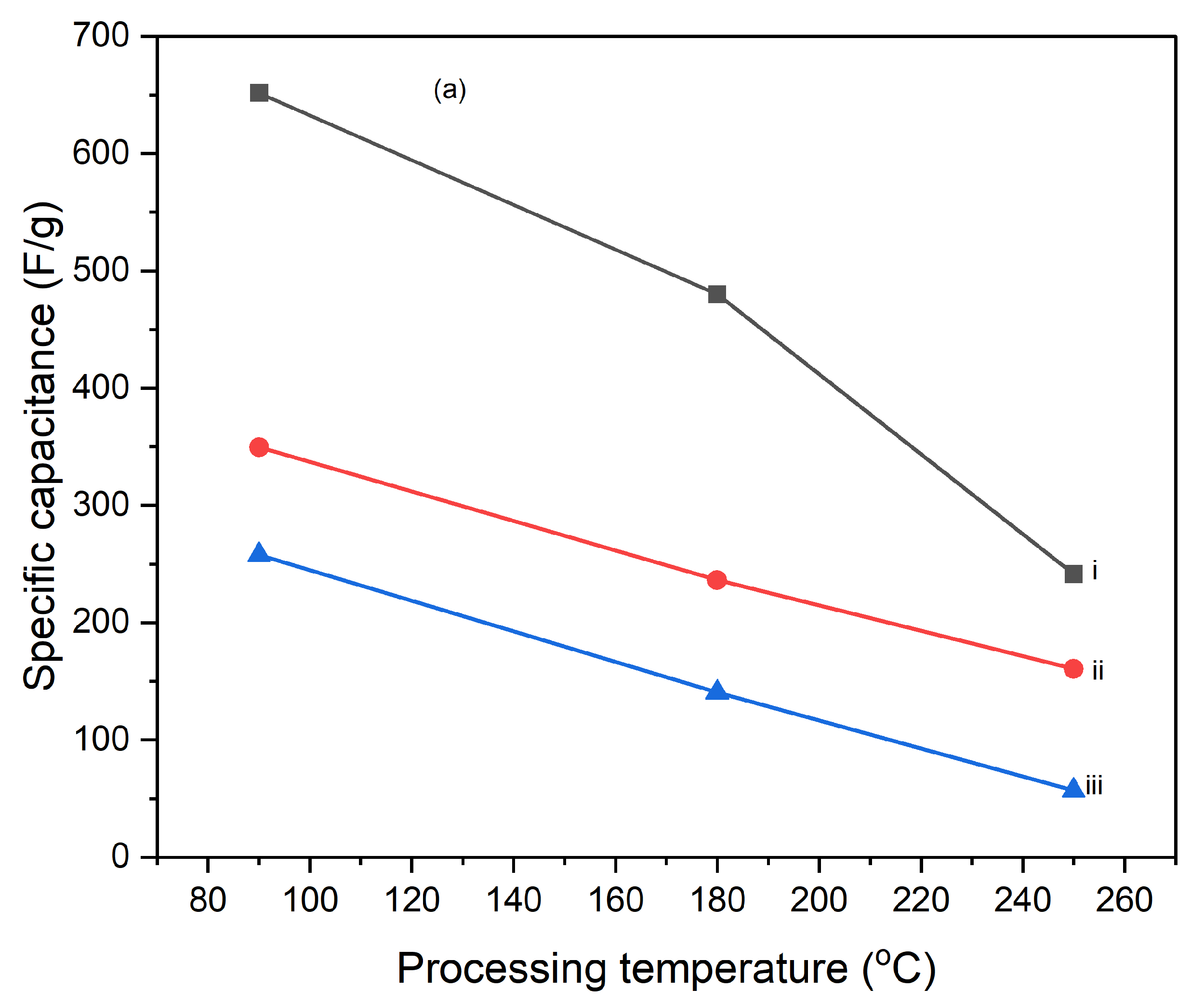

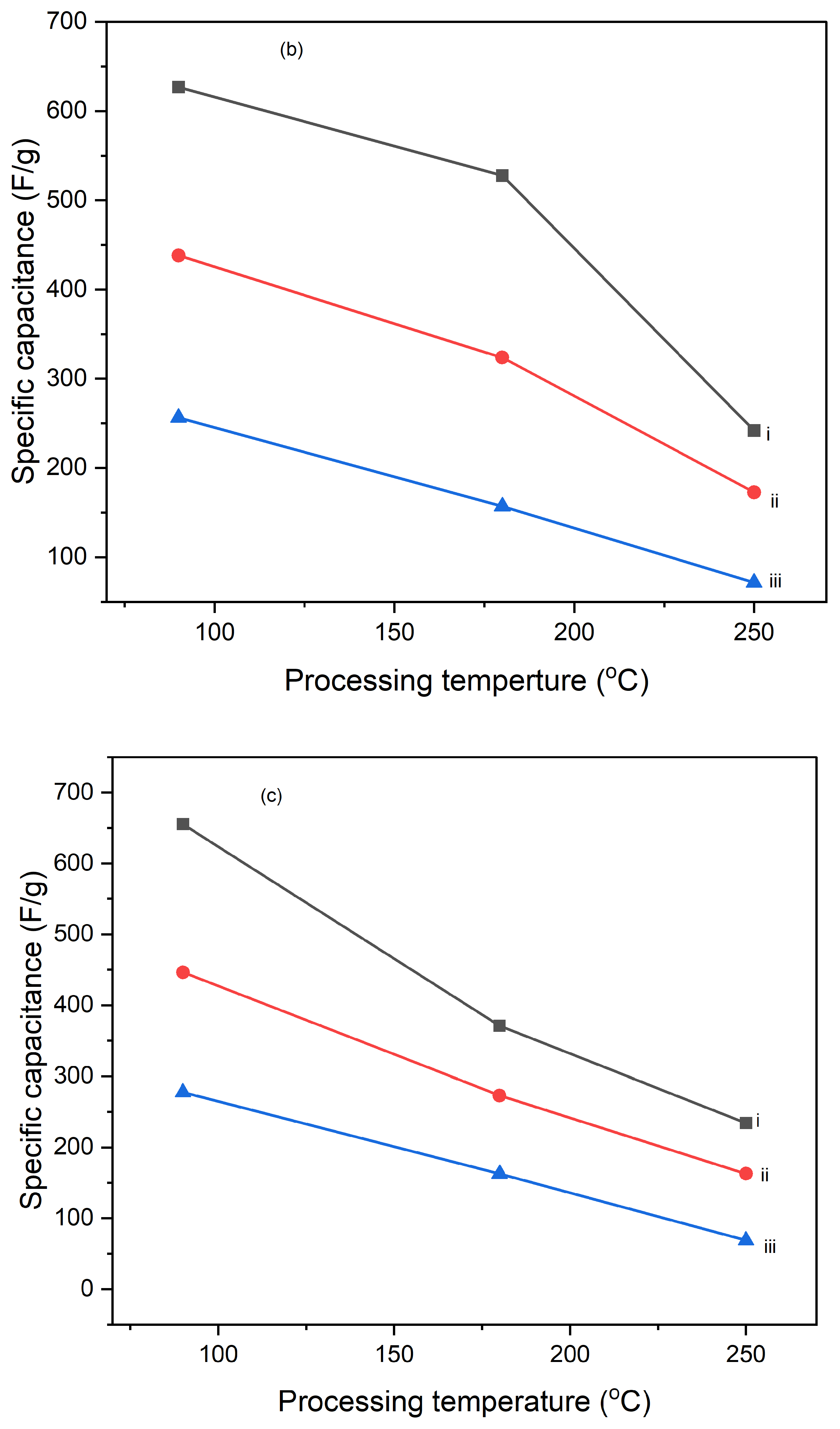

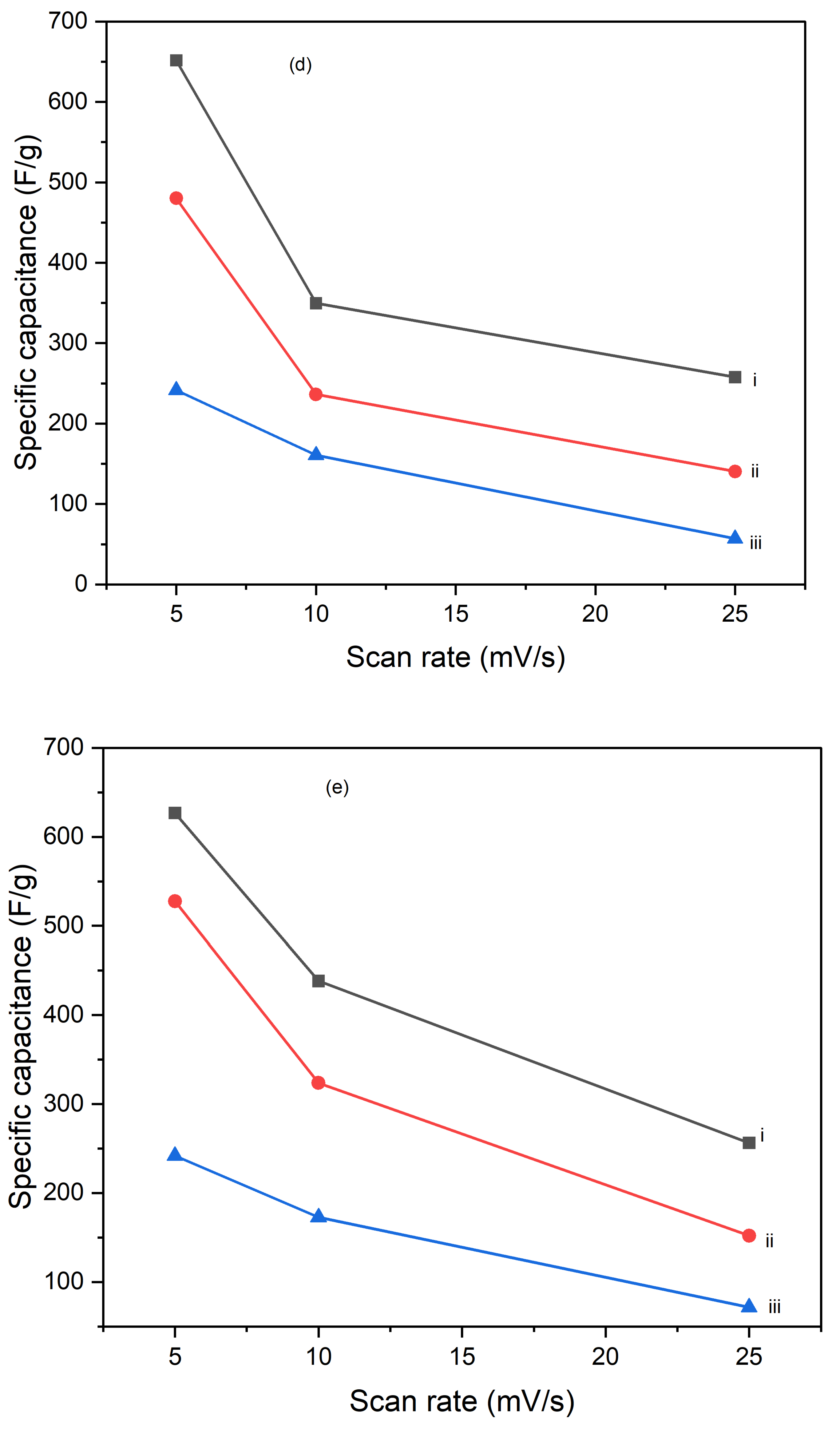

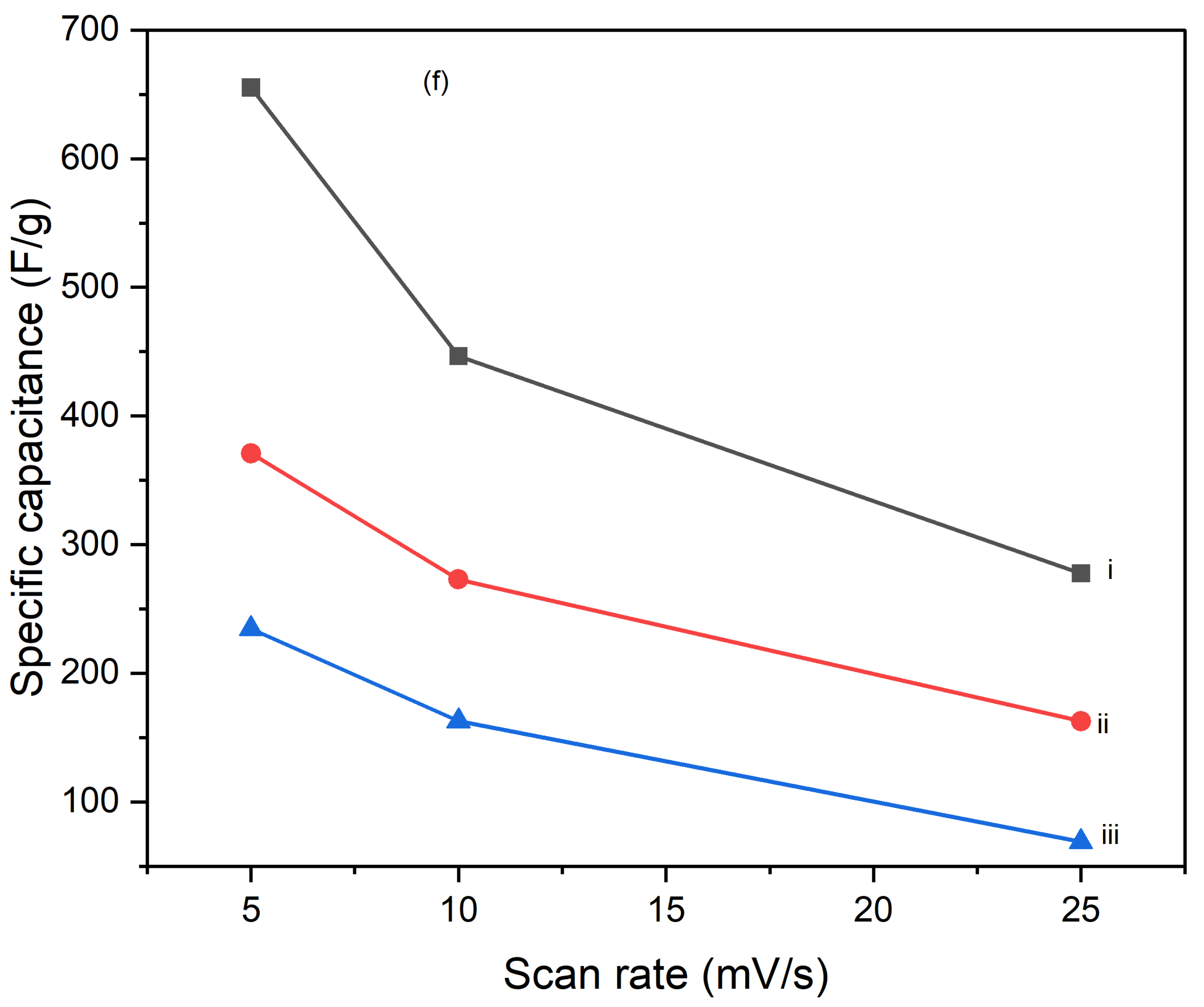

Figures 10 illustrate the variation of specific capacitance calculated from cyclic voltammograms (CVs) at different scan rates (5 mV/s, 10 mV/s, and 25 mV/s) for PI/CNTs hybrid nanocomposites processed at various temperatures (90 °C, 180 °C, and 250 °C) and tested after 1 cycle, 5 cycles, and 10 cycles. Across all conditions, the specific capacitance decreases as the scan rate increases, which is typical for capacitive materials. This trend occurs because slower scan rates provide more time for ion diffusion and better interaction with the electrode surface, leading to higher capacitance values. In the 1-cycle tests, the specific capacitance at 90 °C starts around 651.68 F/g at 5 mV/s, decreases to approximately 236.25 F/g at 10 mV/s, and then slightly increases to about 257.61 F/g at 25 mV/s. This pattern suggests that ion movement becomes more restricted at higher scan rates, particularly during the initial cycle. In the 5-cycle tests, the specific capacitance shows improvement, with values around 626.80 F/g at 5 mV/s, 438.22 F/g at 10 mV/s, and 256.43 F/g at 25 mV/s, indicating enhanced charge storage capability as the electrode material stabilizes with repeated cycling. The 10-cycle tests show further gains, reaching approximately 655.34 F/g at 5 mV/s, 446.48 F/g at 10 mV/s, and 277.69 F/g at 25 mV/s, demonstrating even better charge storage and material stability with more cycles. With the impact of processing temperature, it is clear that the composites processed at 90 °C consistently exhibit the highest specific capacitance across all scan rates for 1 cycle, 5 cycles, and 10 cycles, followed by those processed at 180 °C and 250 °C. This pattern suggests that lower processing temperatures are more favorable for maximizing specific capacitance, likely due to better preservation of the material's structure and electrochemical properties. As the processing temperature increases, the material likely undergoes structural degradation, which diminishes its electrochemical performance. Despite the decline in specific capacitance at higher scan rates, the electrodes maintain strong performance even after 5 and 10 cycles, indicating their good potential for high-rate applications. The PI/CNTs hybrid nanocomposites demonstrate excellent specific capacitance, particularly at lower scan rates and with increased cycling, emphasizing their potential for high-performance energy storage applications, especially when processed at the best processing temperatures.

Figure 11.

Variation of specific capacities calculated from CV of (a) (i) 5mV/s at 1 cycle, (ii) 10mV/s at 1 cycle, (iii) 25mV/s at 1 cycle, (b) (i) 5mV/s at 5 cycle, (ii) 10mV/s at 5 cycle,(iii) 25mV/s at 5 cycle, (c) (i) 5mV/s at 10 cycles, (ii) 10mV/s at 10 cycles, (iii) 25mV/s at 10 cycles, (d) (i) 90oC at 1 cycle, (ii) 180oC at 1 cycle, (iii) 250oC at 1 cycle (e) (i) 90oC at 5 cycles, (ii) 180oC at 5 cycles, (iii) 250oC at 5 cycles and (f) (i) 90oC at 10 cycles, (ii) 180oC at 10 cycles, (iii) 250oC at 10 cycles.

Figure 11.

Variation of specific capacities calculated from CV of (a) (i) 5mV/s at 1 cycle, (ii) 10mV/s at 1 cycle, (iii) 25mV/s at 1 cycle, (b) (i) 5mV/s at 5 cycle, (ii) 10mV/s at 5 cycle,(iii) 25mV/s at 5 cycle, (c) (i) 5mV/s at 10 cycles, (ii) 10mV/s at 10 cycles, (iii) 25mV/s at 10 cycles, (d) (i) 90oC at 1 cycle, (ii) 180oC at 1 cycle, (iii) 250oC at 1 cycle (e) (i) 90oC at 5 cycles, (ii) 180oC at 5 cycles, (iii) 250oC at 5 cycles and (f) (i) 90oC at 10 cycles, (ii) 180oC at 10 cycles, (iii) 250oC at 10 cycles.

Table 1.

Calculated specific capacitance from cyclic voltammetry.

Table 1.

Calculated specific capacitance from cyclic voltammetry.

| CNTs/PI-PPy electrode |

Specific capacitance (F/g)

5mV/s 10mV/s

25mV/s

|

| 90oC |

655.34 |

446.48 |

277.69 |

| 180oC |

370.99 |

272.95 |

162.68 |

| 250oC |

234.42 |

162.78 |

69.02 |

Table 2.

Calculated specific capacities from cyclic voltammetry.

Table 2.

Calculated specific capacities from cyclic voltammetry.

| CNTs/PI-PPy electrode |

Specific capacities (mAh/g)

5mV/s 10mV/s

25mV/s

|

| 90oC |

182.04 |

124.02 |

77.14 |

| 180oC |

103.05 |

75.82 |

45.19 |

| 250oC |

65.12 |

45.22 |

19.17 |

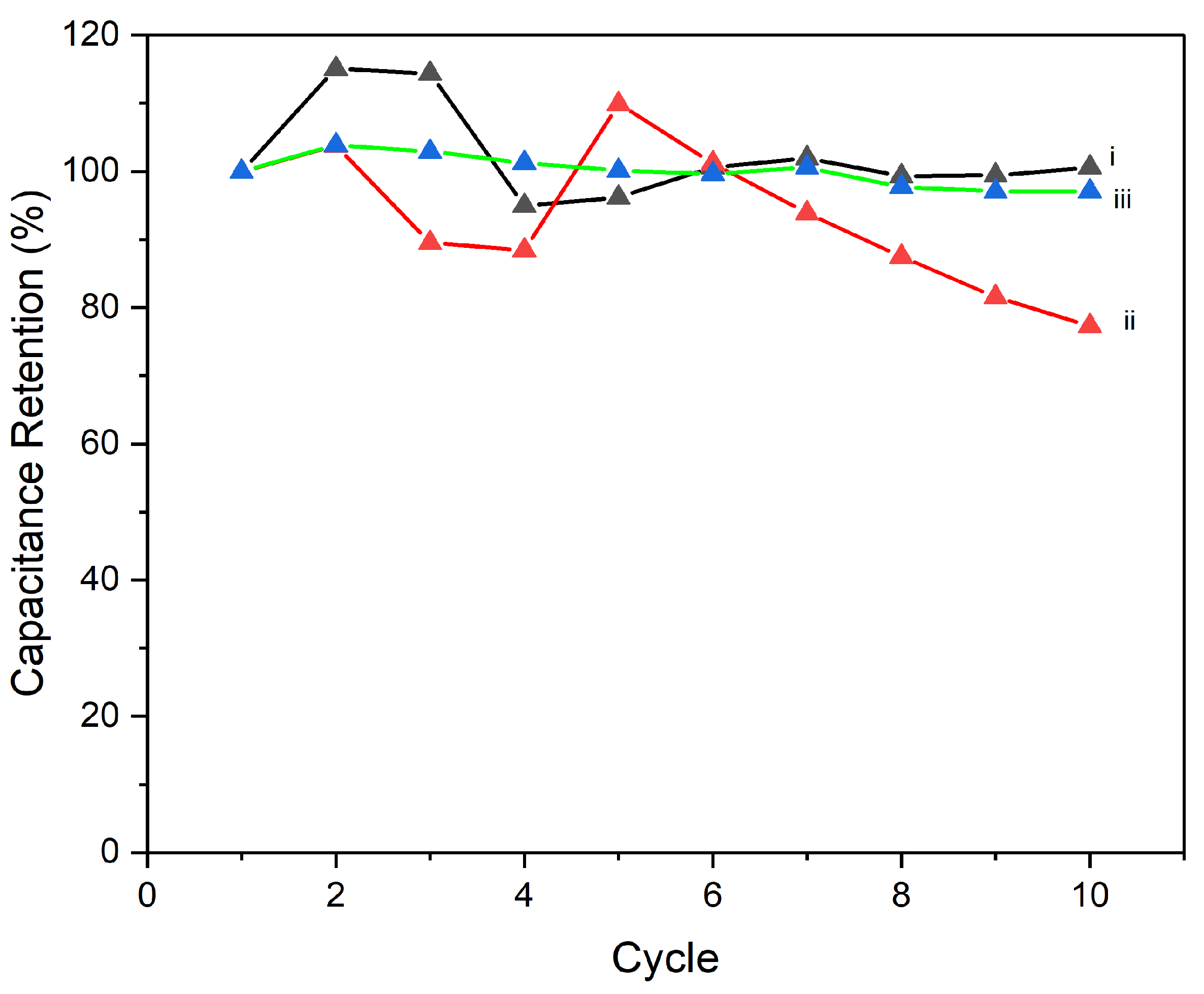

Figure 12 demonstrates that the processing temperature significantly influences the capacitance retention and overall electrochemical stability of CNTs/PI–PPy composite electrodes over 10 cycles at a current density of 0.5 A/g. The electrode processed at 90°C shows the best performance, maintaining capacitance retention around 100% throughout the 10 cycles with minimal degradation, indicating excellent stability and suggesting that 90°C is an optimal processing temperature. In contrast, the electrode processed at 180°C exhibits a noticeable decline in capacitance retention after the 4th cycle, dropping to around 80% by the 10th cycle. This suggests that this temperature may lead to material degradation or poor component interaction, affecting long-term performance. The 250°C processed electrode, while more stable than the 180°C sample, does not surpass the performance of the 90°C electrode, indicating that although higher temperatures may enhance certain material properties, they do not necessarily improve long-term electrochemical stability. Overall, the 90°C processing temperature is the most effective for achieving high capacitance retention and stability, making it the preferred choice for optimizing the performance of these composite electrodes in energy storage applications.

4.2. Galvanostatic Charge/Discharge

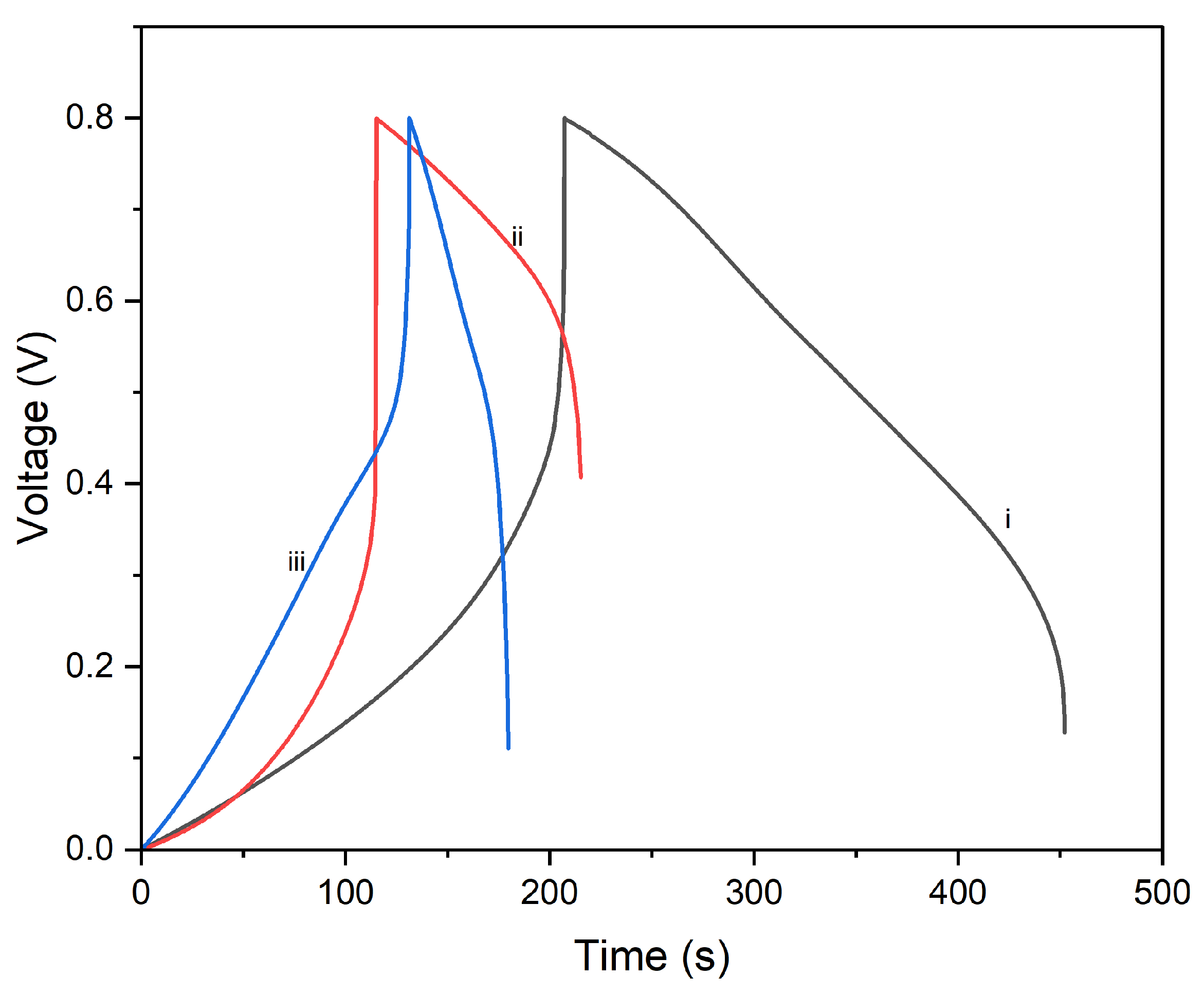

The charge/discharge curves in

Figure 13 show the electrochemical performance of CNTs//PI–PPy composites processed at different temperatures (90 °C, 180 °C, and 250 °C) under an energy density of 0.5 A/g. The composite processed at 90 °C shows the longest discharge time, indicating the highest energy storage capacity, with a smooth and symmetric curve suggesting good capacitive behavior and efficient charge storage and release. The 180 °C composite exhibits a shorter discharge time and slight asymmetry, reflecting intermediate performance and some polarization effects. The 250 °C composite has the shortest discharge time and the most asymmetric curve, indicating the lowest energy storage capacity and higher resistance, likely due to material degradation or structural changes at the higher temperature. Overall, the 90 °C processed composite demonstrates the best electrochemical performance, emphasizing the importance of optimizing processing temperatures for supercapacitor applications. Higher processing temperatures negatively impact energy storage capacity and charge/discharge efficiency, as shown by the poorer performance of the 180 °C and 250 °C samples

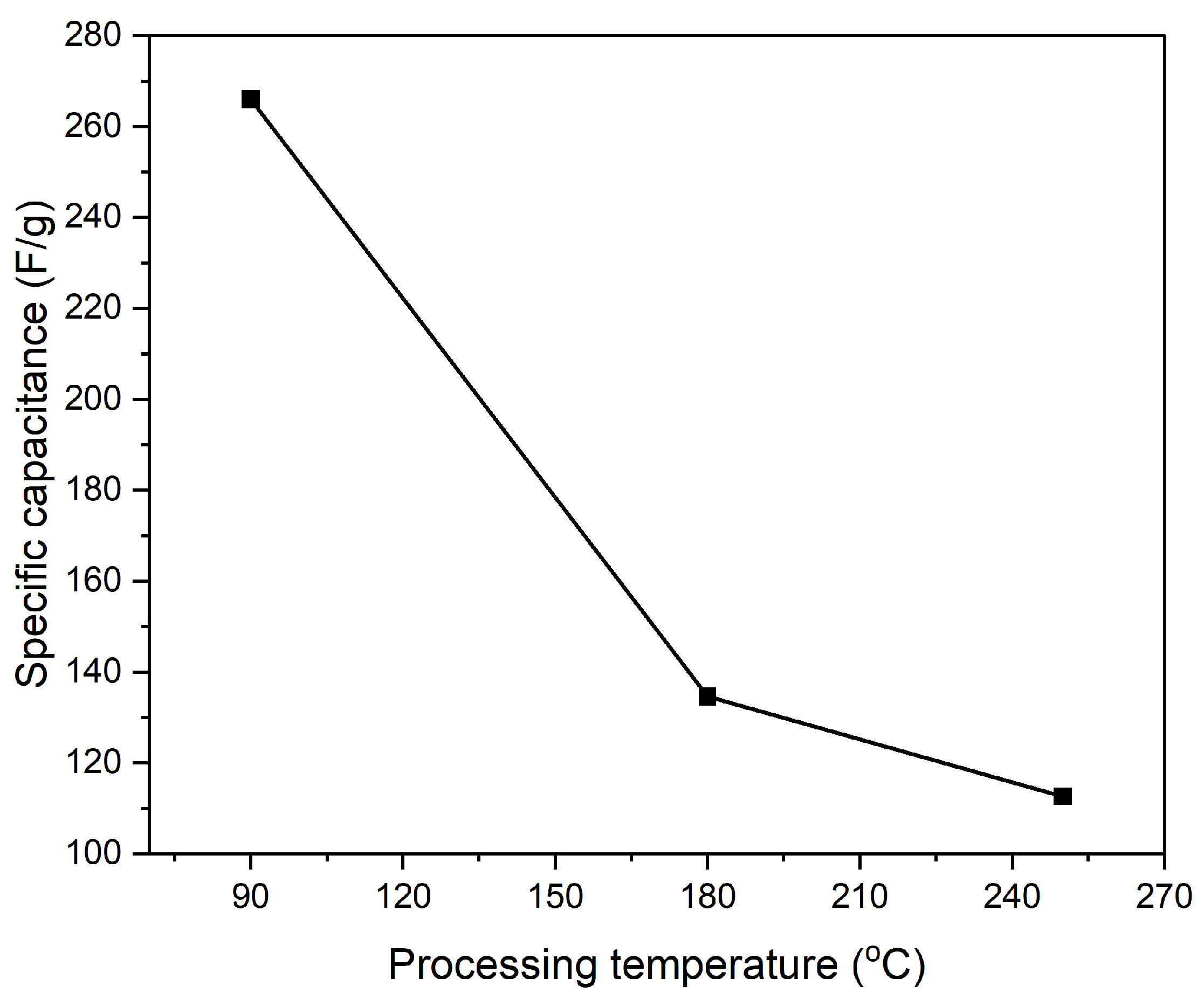

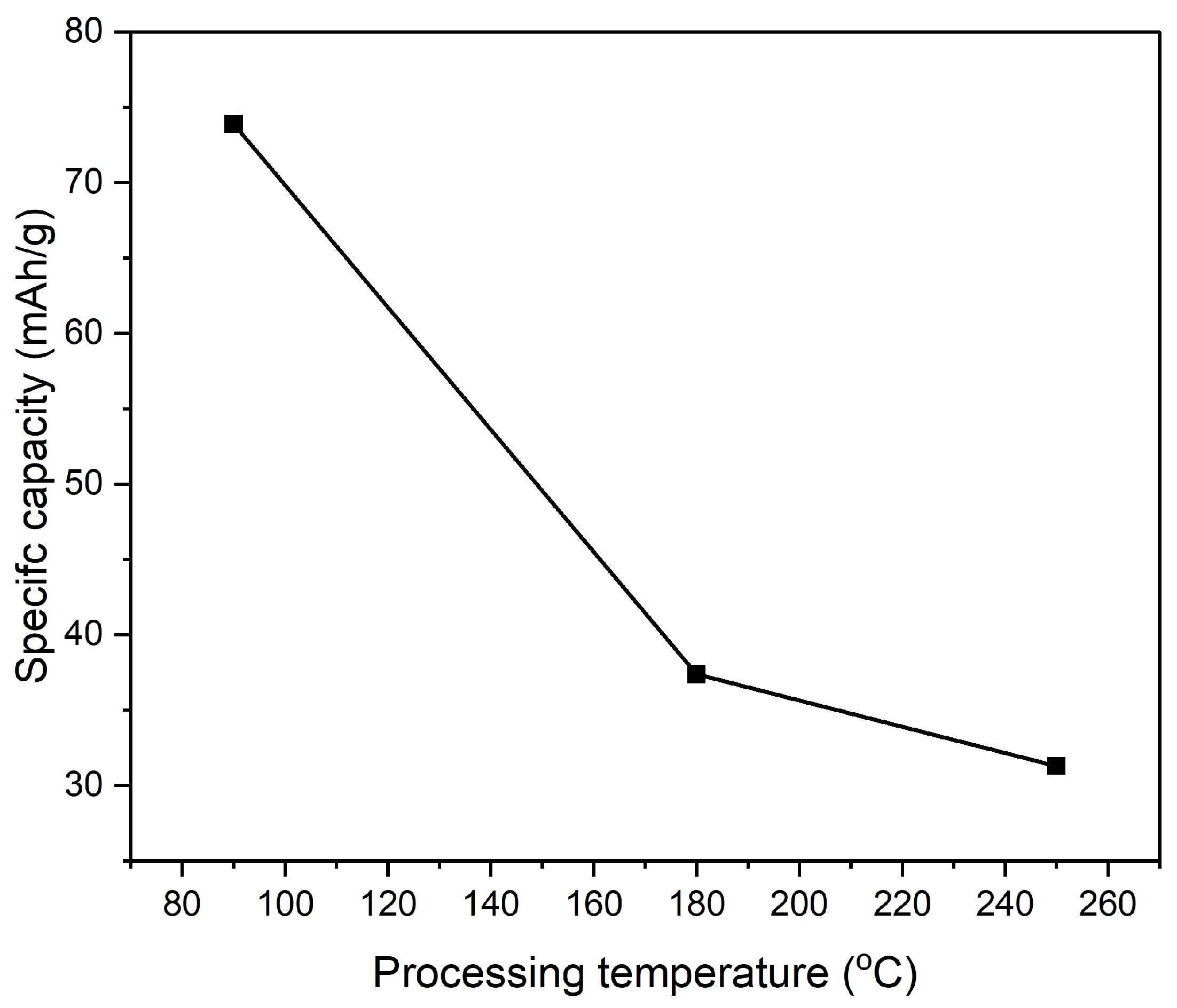

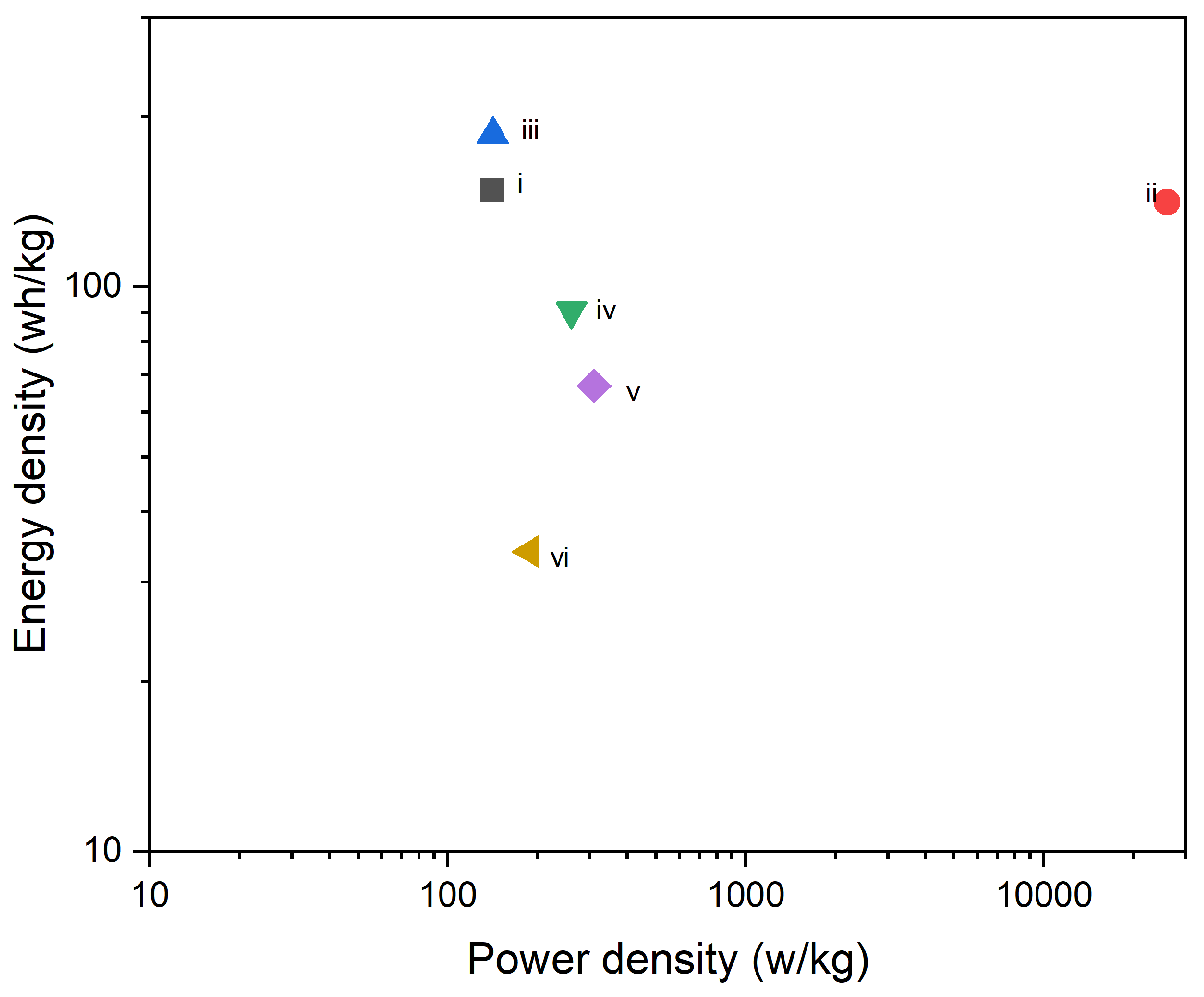

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 together illustrate the impact of processing temperature on the electrochemical performance of CNTs/PI composite electrodes electrodeposited with polypyrrole (PPy), as measured by galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD) at a current density of 0.5 A/g. In

Figure 14, the specific capacitance is shown to decrease significantly as the processing temperature increases. The composite electrode processed at 90 °C demonstrates the highest specific capacitance, approximately 266 F/g. However, with an increase in processing temperature to 180 °C, the specific capacitance drops sharply to around 135 F/g and further decreases to 113 F/g at 250 °C. This decline suggests that higher processing temperatures may negatively affect the composite’s ability to store charge, likely due to thermal degradation or alterations in the microstructure, such as reduced porosity or increased internal resistance, which hinder effective ion transport. Similarly,

Figure 15 shows a corresponding decrease in specific capacity with increasing processing temperatures. The specific capacity of the composite electrode at 90 °C is the highest, around 74 mAh/g. As the temperature rises to 180 °C, the specific capacity drops to about 37 mAh/g, and further decreases to approximately 30 mAh/g at 250 °C. This trend parallels the decline observed in specific capacitance, reinforcing the idea that higher processing temperatures degrade the material's electrochemical properties, potentially due to reduced active surface area, decreased porosity, or changes in the internal resistance of the material. When considering both figures together, it becomes evident that processing temperature plays a critical role in determining the electrochemical performance of PI/CNTs hybrid nanocomposite electrodes. Lower processing temperatures, particularly around 90 °C, are more favorable for achieving higher specific capacitance and specific capacity. This is likely because lower temperatures help preserve the material's microstructure, ensuring higher porosity, better ion mobility, and lower internal resistance, which contribute to more efficient charge storage. On the contrary, higher processing temperatures, such as 180 °C and 250 °C, appear to impair these properties, leading to diminished electrochemical performance. This degradation may be attributed to factors such as thermal degradation, which can alter the material's structure, reduce active sites, and increase the resistance to ion movement, ultimately lowering both specific capacitance and specific capacity. Additionally, it's important to note the discrepancy between the specific capacitance values obtained from GCD measurements in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 and those derived from cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves. GCD measurements, which involve a constant current charge-discharge process, tend to produce lower apparent capacitance due to higher polarization and greater voltage drops. In contrast, CV is more sensitive to surface redox reactions and captures more transient processes, often leading to higher capacitance values.

Figure 14.

The specific capacitance of composite electrode PI/CNTs doped with PPy was measured by using GCD at 0.5 A/g.

Figure 14.

The specific capacitance of composite electrode PI/CNTs doped with PPy was measured by using GCD at 0.5 A/g.

Figure 15.

The specific capacity of composite electrode PI/CNTs doped with PPy was measured by using GCD at 0.5 A/g.

Figure 15.

The specific capacity of composite electrode PI/CNTs doped with PPy was measured by using GCD at 0.5 A/g.

Table 3.

Summary of specific capacitance and capacities obtained from charge-discharge cycles for 700-second deposition at 0.5 A/g.

Table 3.

Summary of specific capacitance and capacities obtained from charge-discharge cycles for 700-second deposition at 0.5 A/g.

|

PI/CNTs–PPy electrode

|

Specific Capacitance (F/g)

0.5A/g

|

|

Specific Capacity (mAh/g)

|

| 90 °C |

265.98 |

|

73.88 |

| 180 °C |

134.58 |

|

37.38 |

| 250 °C |

112.65 |

|

31.29 |

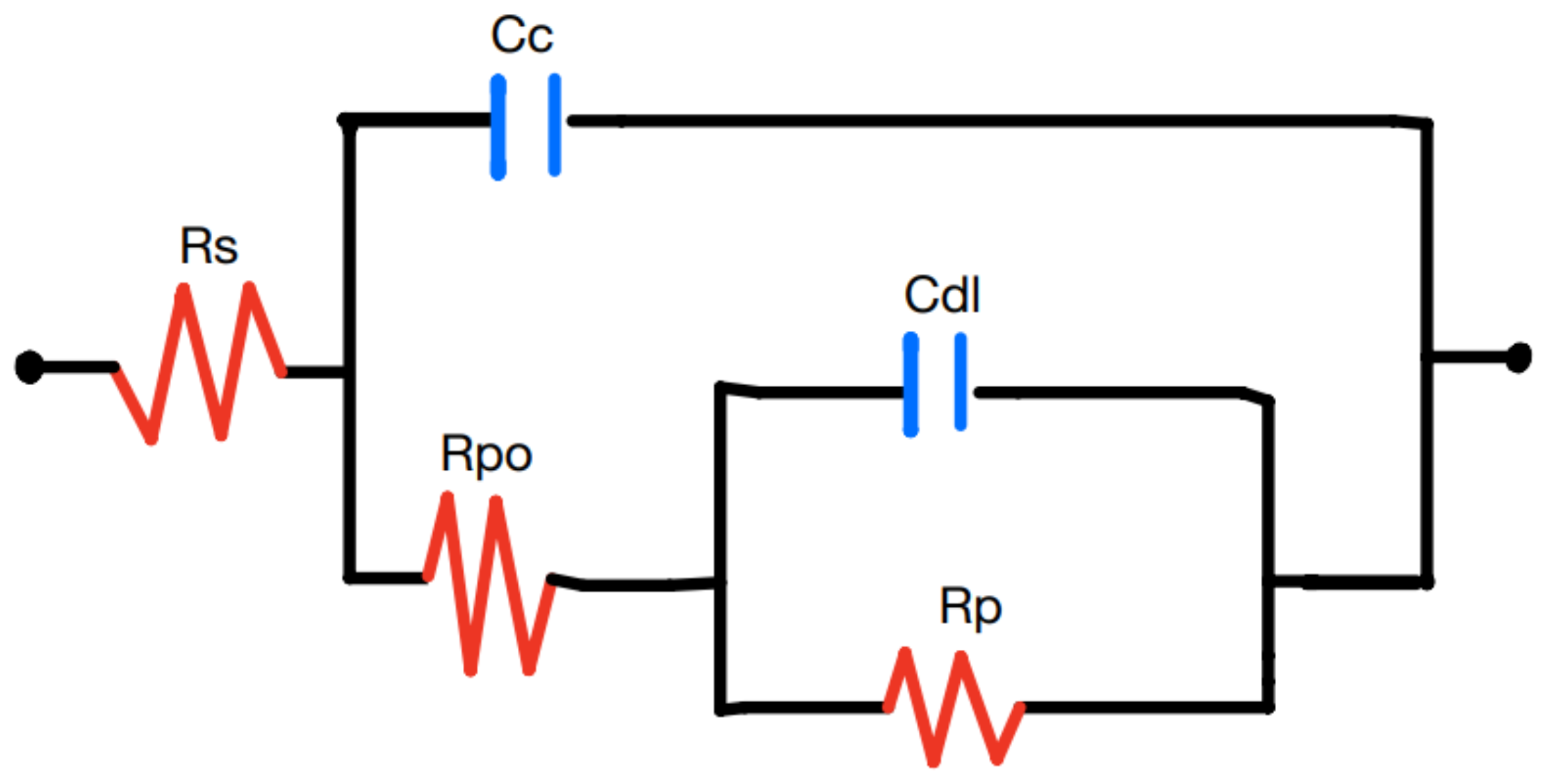

4.3. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

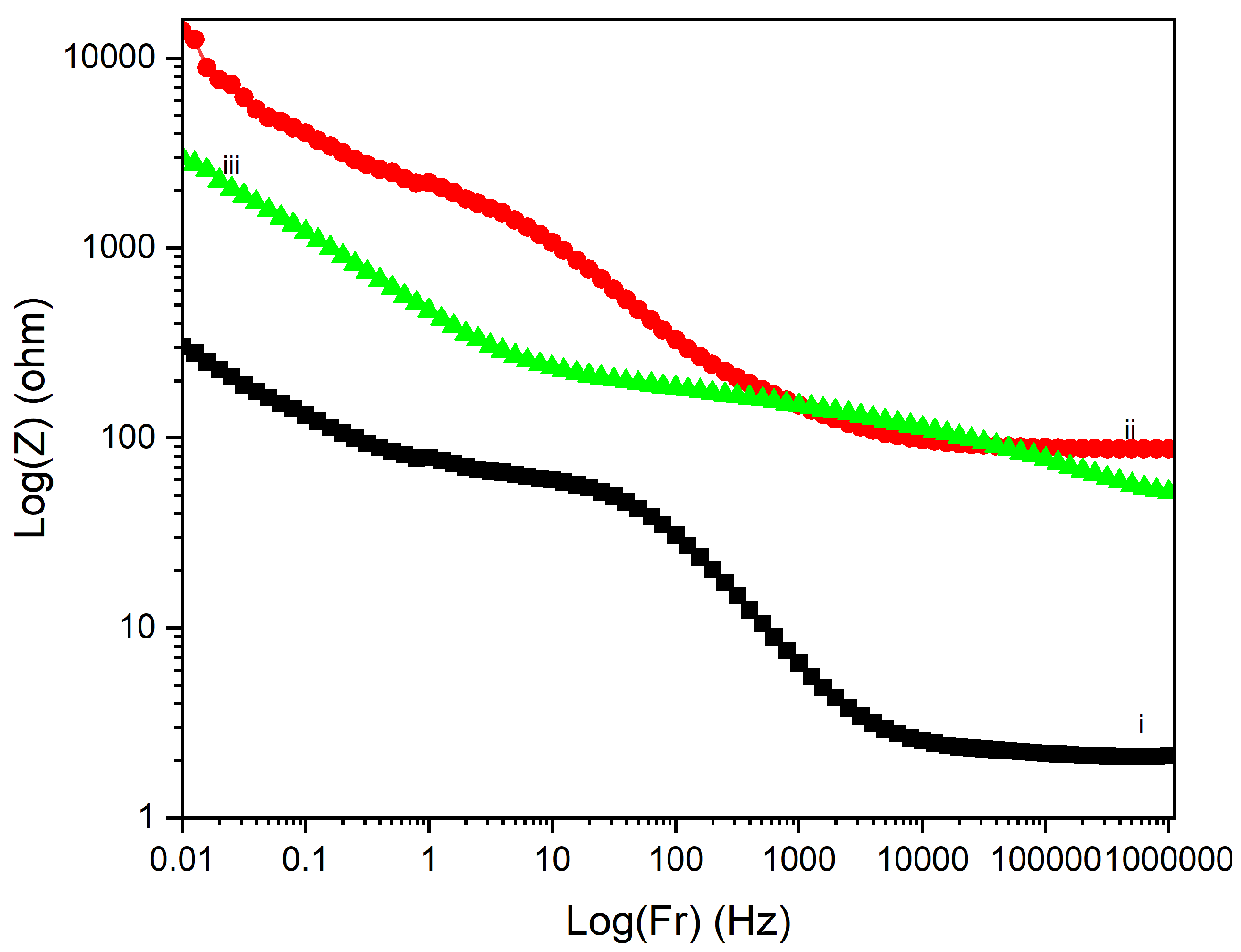

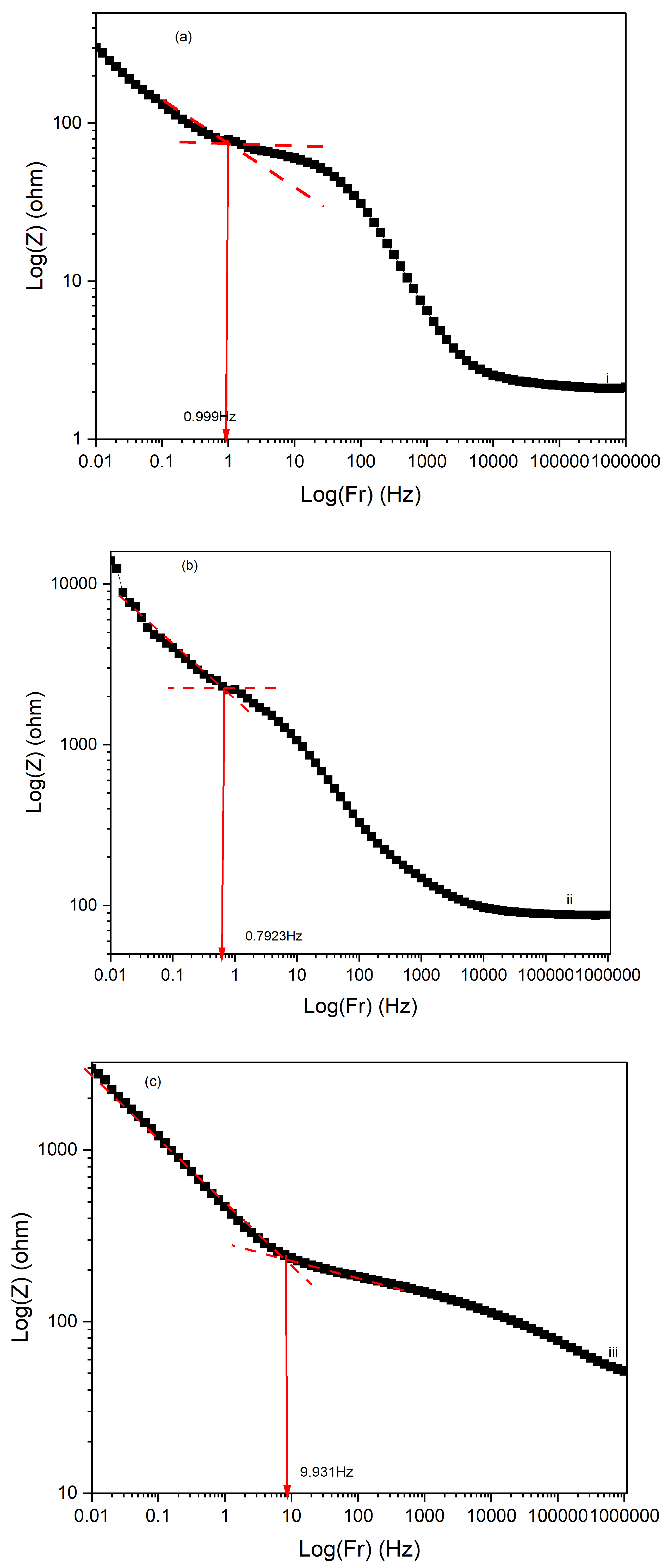

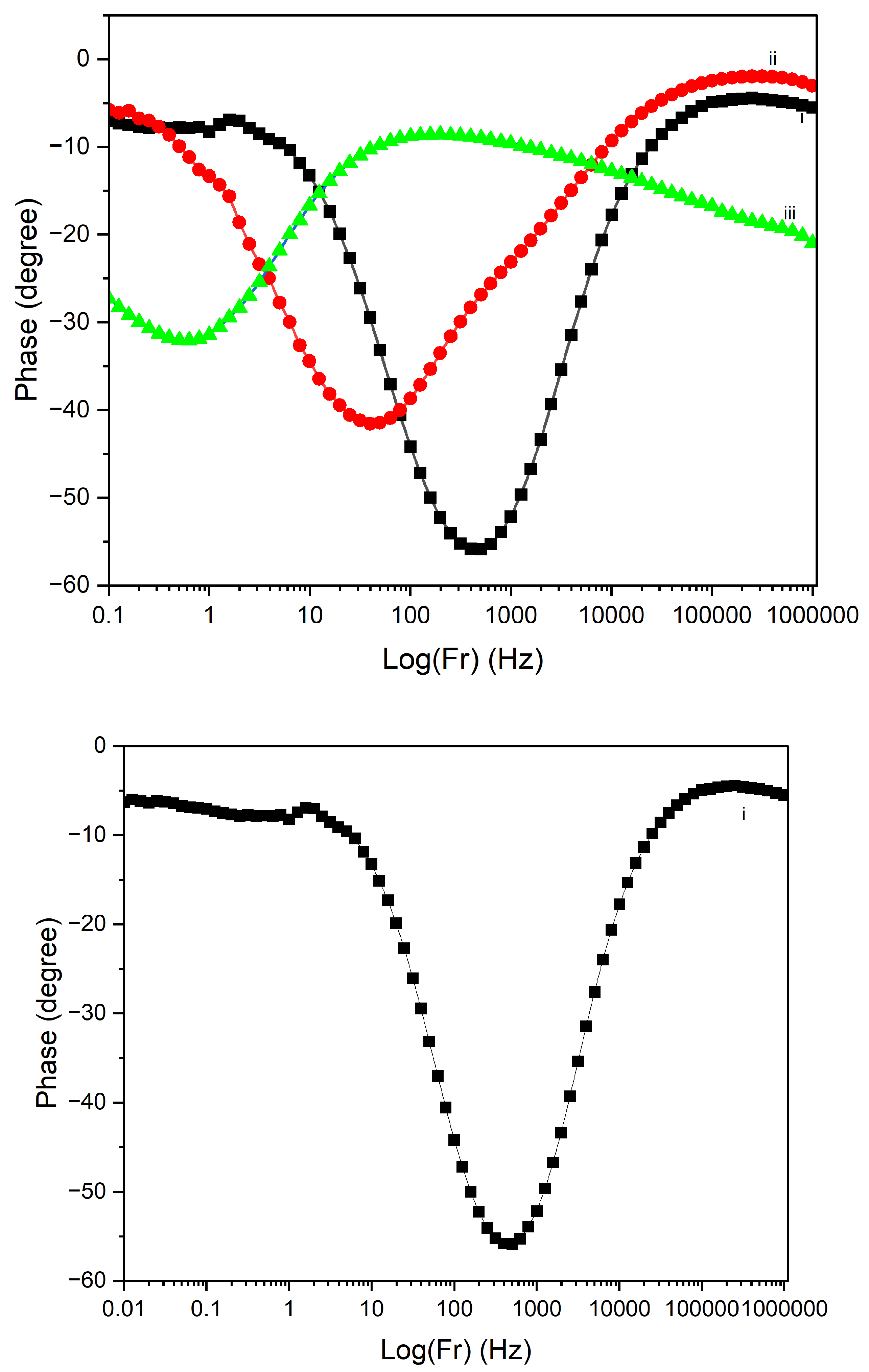

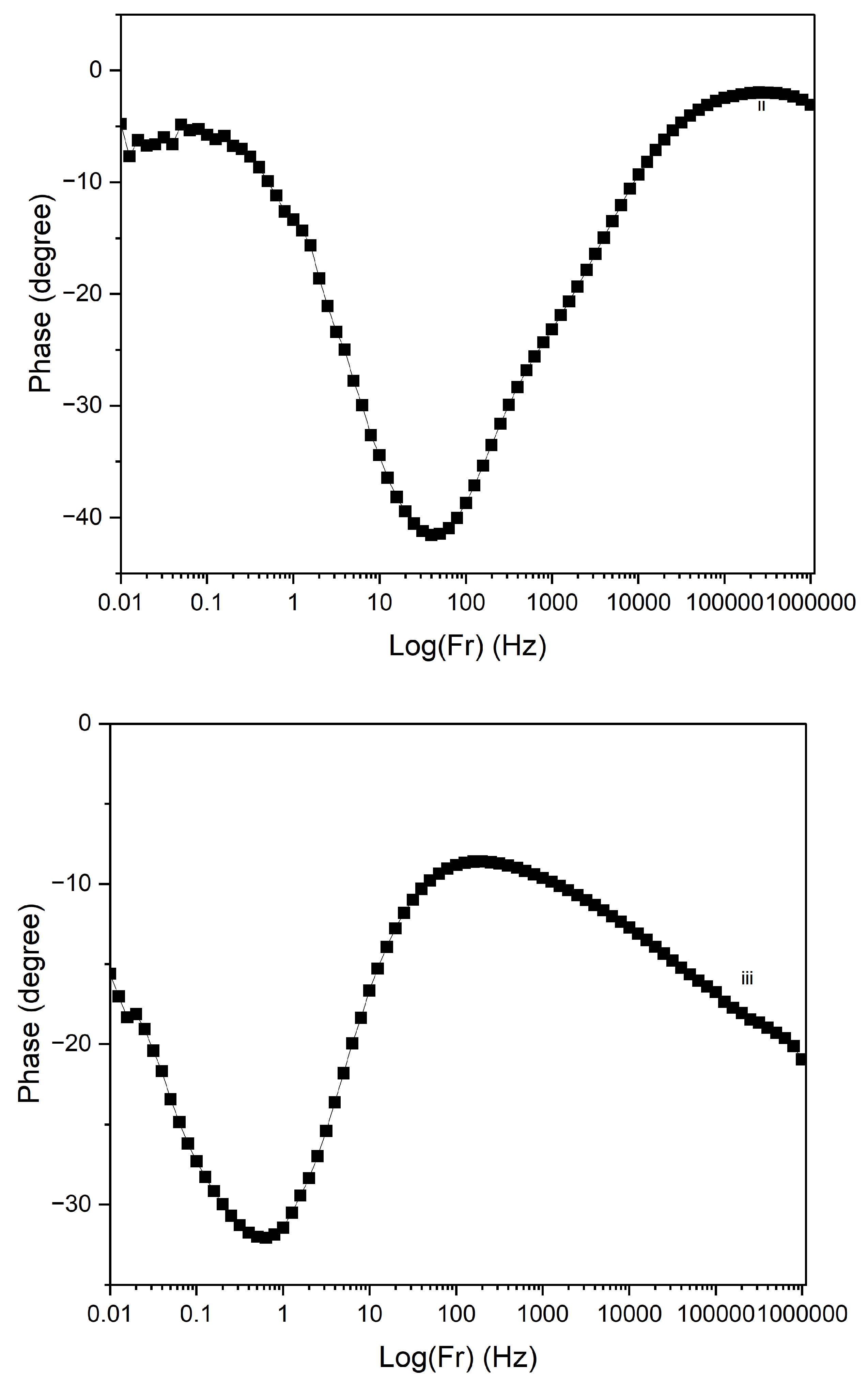

Figure 17 displays the Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) Bode plots for PI/CNTs/–PPy composite samples processed at different temperatures (90 °C, 180 °C, and 250 °C) following a 700-second deposition of polypyrrole (PPy). In the impedance magnitude plot (Log(Z) vs. Log(Fr)) shown in

Figure 16, the sample processed at 90 °C exhibits the lowest impedance across the frequency range, indicating superior conductivity and minimal resistance. This is further supported by the analysis of solution resistance, coating resistance, and pore resistance, where the 90 °C sample demonstrated the lowest values for all three parameters, particularly a solution resistance of 2.307 ohms, a coating resistance of 94 ohms, and a pore resistance of 301.8 ohms. These factors collectively suggest that the 90 °C sample has well-formed conductive and porous structures, facilitating efficient ion transport and charge transfer. The 180 °C sample shows higher impedance, reflecting increased resistance and reduced conductivity. The analysis reveals that the solution resistance is 87.67 ohms, significantly higher than the 90 °C sample, while the coating resistance is extremely high at 8700 ohms, indicating poor conductivity of the coating material. The pore resistance is also the highest among the samples at 13,930 ohms, suggesting substantial limitations in ion transport within the porous structure. This combination of high coating and pore resistance highlights the compromised electrochemical performance of the 180 °C sample, despite two notable time-constant phase changes in

Figure 18, one at 30 Hz and another at 500 Hz. The phase changes reflect a balance between capacitive and resistive properties, though the resistance remains significantly higher than the 90 °C sample. In contrast, the 250 °C sample exhibits the highest impedance overall, signifying the poorest conductivity and the most resistive behavior. The solution resistance is relatively low at 51.8 ohms, but the coating resistance, at 400 ohms, is still considerably higher than the 90 °C sample, indicating suboptimal conductivity. The pore resistance is measured at 2991.9 ohms, lower than the 180 °C sample but still much higher than the 90 °C sample, reflecting limited ion transport. The phase angle plot

Figure 17 for the 250 °C sample demonstrates the least capacitive behavior, with a time-constant phase change occurring at a much lower frequency of 7 Hz, underscoring significant resistive nature and poor charge transfer capabilities. The large shift in phase angle towards resistive behavior at low frequencies indicates substantial impedance and limited capacitive performance.

Overall, the Bode plots and resistance analysis indicate that the composite processed at 90 °C offers the best electrochemical performance, with lower impedance, effective ion transport, and a balanced capacitive response at higher frequencies. The low values of solution, coating, and pore resistances further confirm the superior electrochemical properties of the 90 °C sample compared to, the composites processed at 180 °C and 250 °C exhibit increased resistance across all resistance types, lower frequency phase changes, and less desirable capacitive properties. These findings emphasize the critical importance of optimizing processing temperatures to enhance the electrochemical properties of PI/CNTs–PPy composites for energy storage applications.

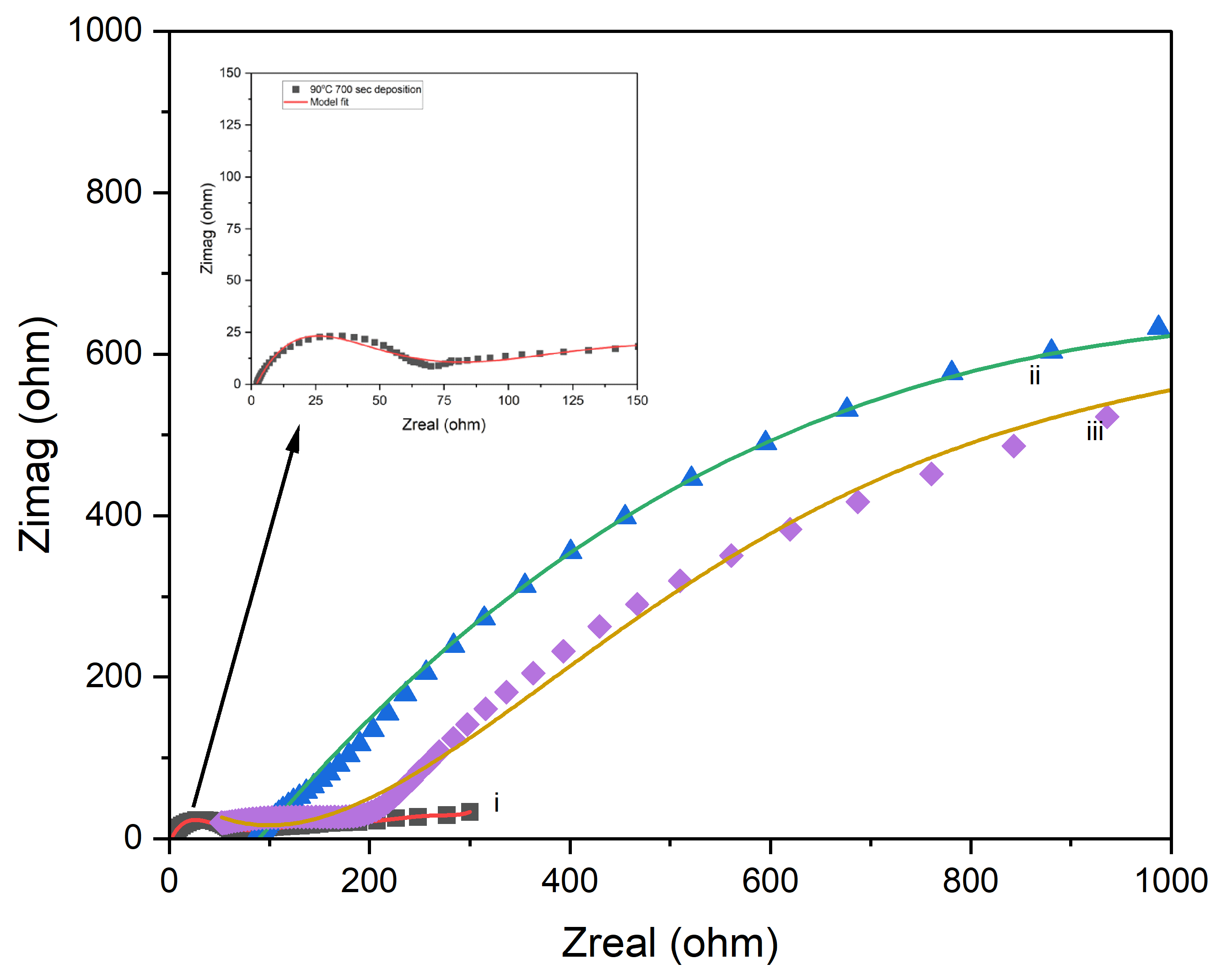

The Nyquist plots in

Figure 19 reveal the impact of processing conditions on the electrochemical performance of PI/CNTs–PPy hybrid nanocomposites, highlighting the consequences of failed coatings. The 90°C sample demonstrates superior performance with a bulk resistance of 65.27 Ω, specific capacitance of 209.16 F/g (23.15 Ω impedance), and a weight gain of 1.669% (0.003287 g), supported by a small semicircle in the Nyquist plot, indicating uniform coating, low surface roughness, and effective ion diffusion, with a porosity of 4.59. In contrast, the 180°C sample shows characteristics of a failed coating, with a bulk resistance of 2366.4 Ω, drastically reduced specific capacitance of 5.4 F/g (1236 Ω impedance), and a weight gain of only 1.313% (0.002284 g). Its large semicircle reflects severe surface roughness, poor uniformity, and high charge transfer resistance, compounded by Warburg impedance effects and a low porosity of 0.35, indicating limited ion transport and inhomogeneity. The 250°C sample presents mixed results, with a bulk resistance of 143.62 Ω, a specific capacitance of 123.90 F/g (26.35 Ω impedance), and the lowest weight gain at 0.567% (0.004875 g). The large semicircle in its Nyquist plot indicates poor coating uniformity, sluggish charge transfer, and thermal degradation, as evidenced by a phase shift at 7 Hz, despite a slight improvement in porosity to 1.52 compared to the 180°C sample. These results demonstrate that failed coatings lead to increased impedance, reduced capacitance, and poor ion transport, with the 90°C sample emerging as the most efficient due to its balanced electrochemical properties, emphasizing the importance of optimizing processing temperatures for effective and uniform coatings.

Figure 19.

EIS Nyquist plot model with simplified Randles circuit for coating defect for PI/CNTs-PPy sample processed at (i) 90oC, (ii) 180oC, and (iii) 250oC at the 700-second deposition of PPy.

Figure 19.

EIS Nyquist plot model with simplified Randles circuit for coating defect for PI/CNTs-PPy sample processed at (i) 90oC, (ii) 180oC, and (iii) 250oC at the 700-second deposition of PPy.

Table 4.

Summary of theoretical porosity, resistance, and specific capacitance obtained using EIS.

Table 4.

Summary of theoretical porosity, resistance, and specific capacitance obtained using EIS.

| Material |

Bulk Resistance (Ω) (EIS)

|

Weigh gain (%) |

Specific capacitance (F/g) (EIS) |

Porosity (EIS) |

| PI/CNTs–90 °C |

65.27 |

1.669 (0.003287g) |

209.16 (23.15Ω) |

4.59 |

| PI/CNTs–180 °C |

2366.4 |

1.313 (0.002284g) |

5.40 (1236Ω) |

0.35 |

| PI/CNTs–250 °C |

143.62 |

0.567 (0.004875g) |

123.90 (26.35Ω) |

1.52 |

Table 5.

Summary of resistance values obtained using (EIS).

Table 5.

Summary of resistance values obtained using (EIS).

| Material |

Solution resistance (Ω) |

Charge transfer resistance (Ω) |

Pore resistance (Ω) |

Coating resistance (Ω) |

| PI/CNTs–90 °C |

2.307 |

67.58 |

301.8 |

94 |

| PI/CNTs–180 °C |

87.67 |

2465 |

13930 |

8700 |

| PI/CNTs–250 °C |

51.8 |

194.79 |

2991.9 |

400 |