Submitted:

01 January 2025

Posted:

02 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Despite improving operational efficiency of buildings, annual emissions from construction remain stubbornly high. The substitution of fast-growing biogenic materials for high-carbon footprint extractive materials is increasingly discussed as a mitigation tool. Here we identify the relative interest in timber bamboo as such a tool through literature and biobliometric analysis. We review the carbon capturing and structural properties of timber bamboo that underly bamboo’s growing research interest, which, however, has yet to translate to any material degree of adoption in mainstream construction. Given the near absence of subsidies, regulatory mandates and “green premiums”, timber bamboo must become fully cost competitive with existing materials to achieve adoption and provide its carbon mitigation promise. The main problems preventing timber bamboo’s cost competitiveness are analyzed with possible solutions proposed. Finally, the beneficial climate prospects of adopting timber bamboo buildings in substitution for 25% of new cement buildings is projected at over 10 billions tonnes of reduced carbon emissions from 2035 to 2050 and nearly 45 billion tonnes of reduced carbon emissions from 2035 to 2100.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

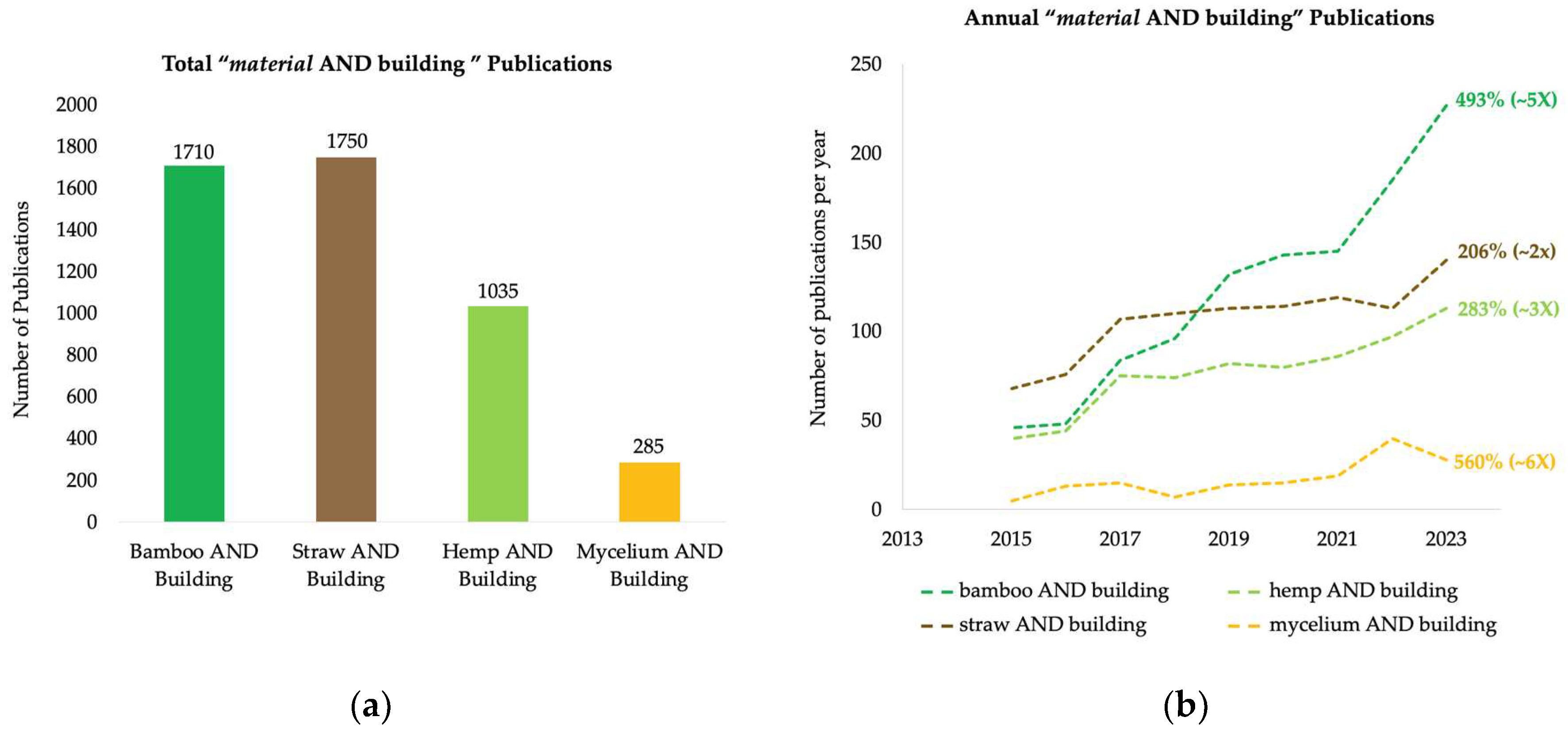

2. Review: Trends in Timber Bamboo Research

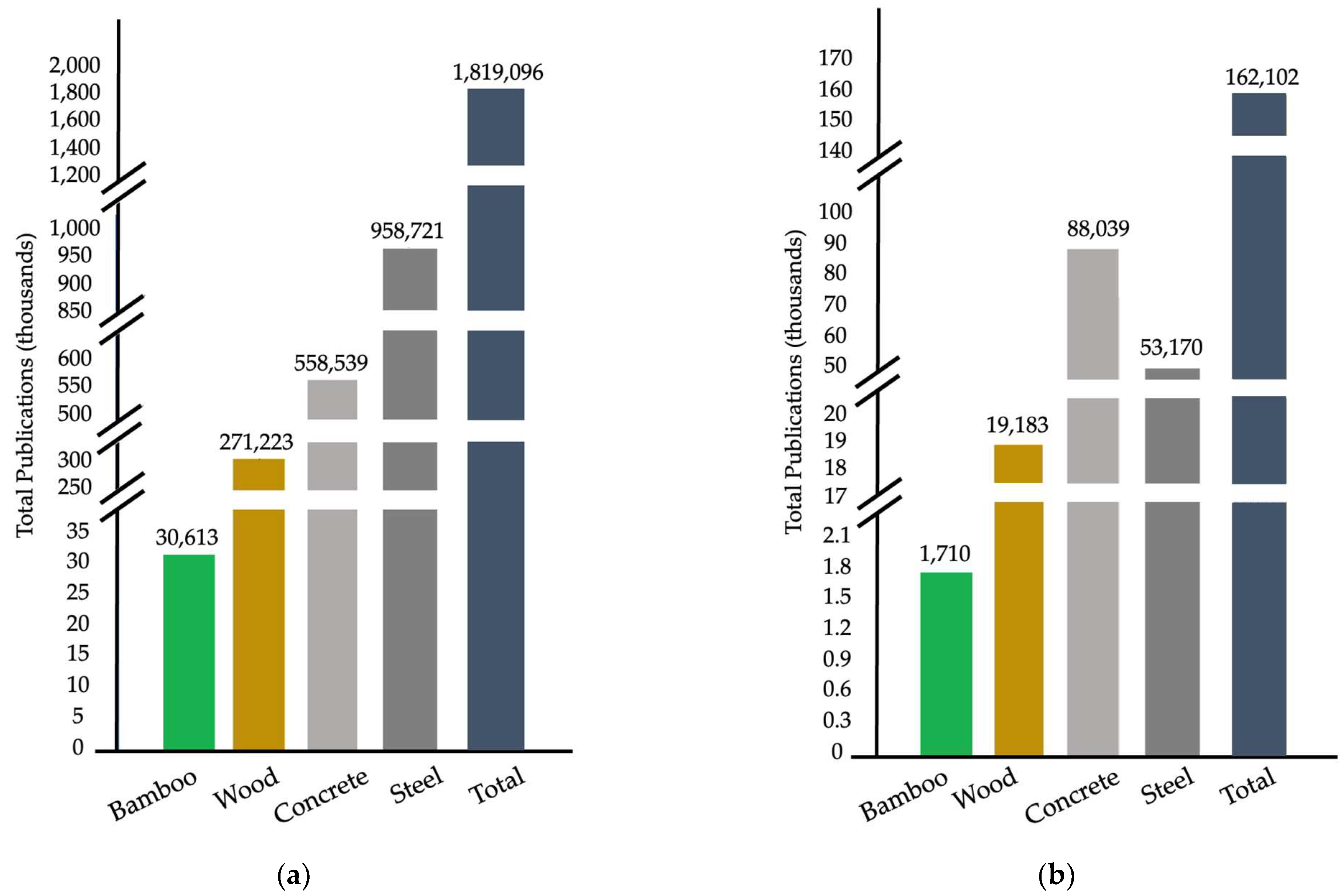

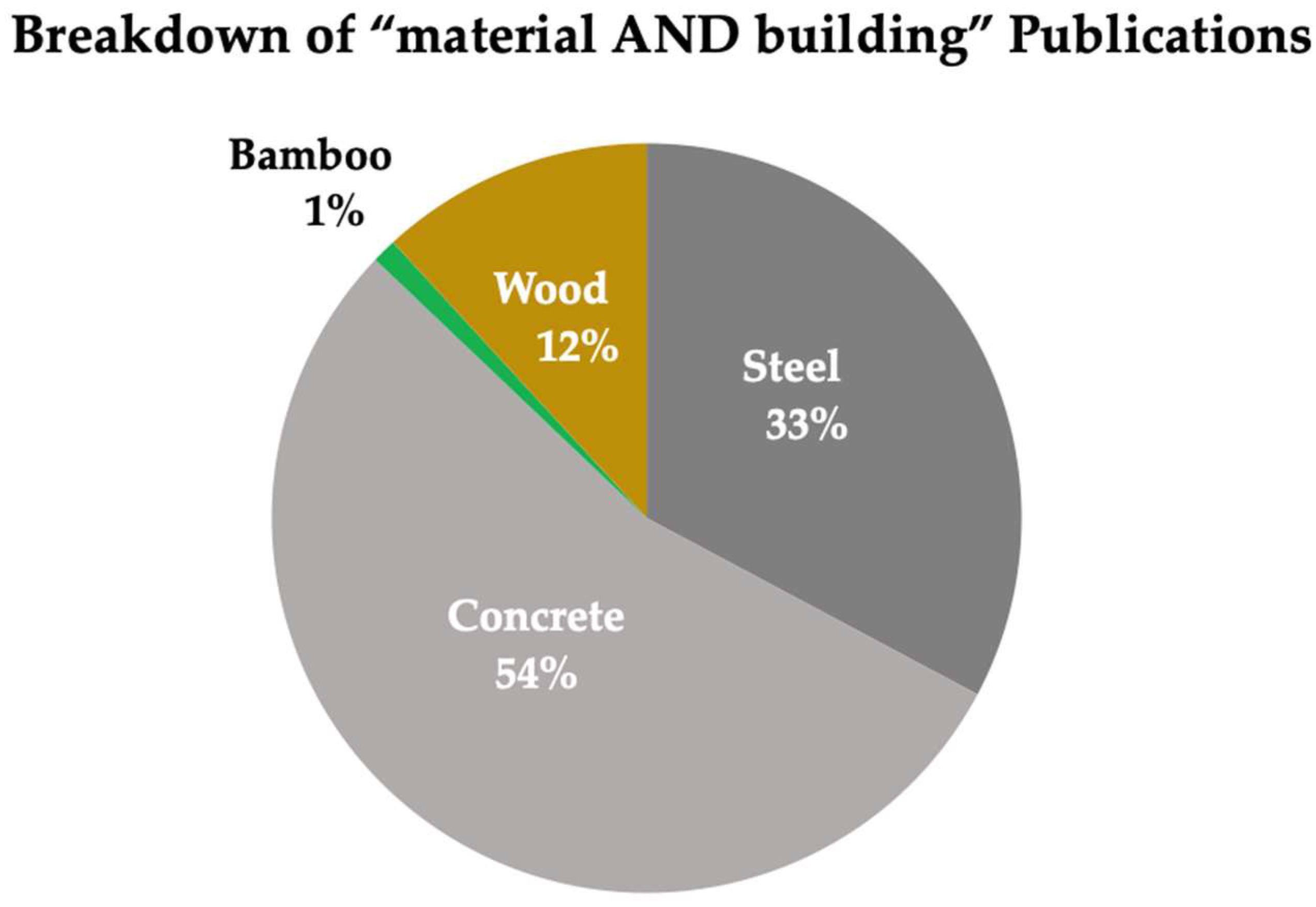

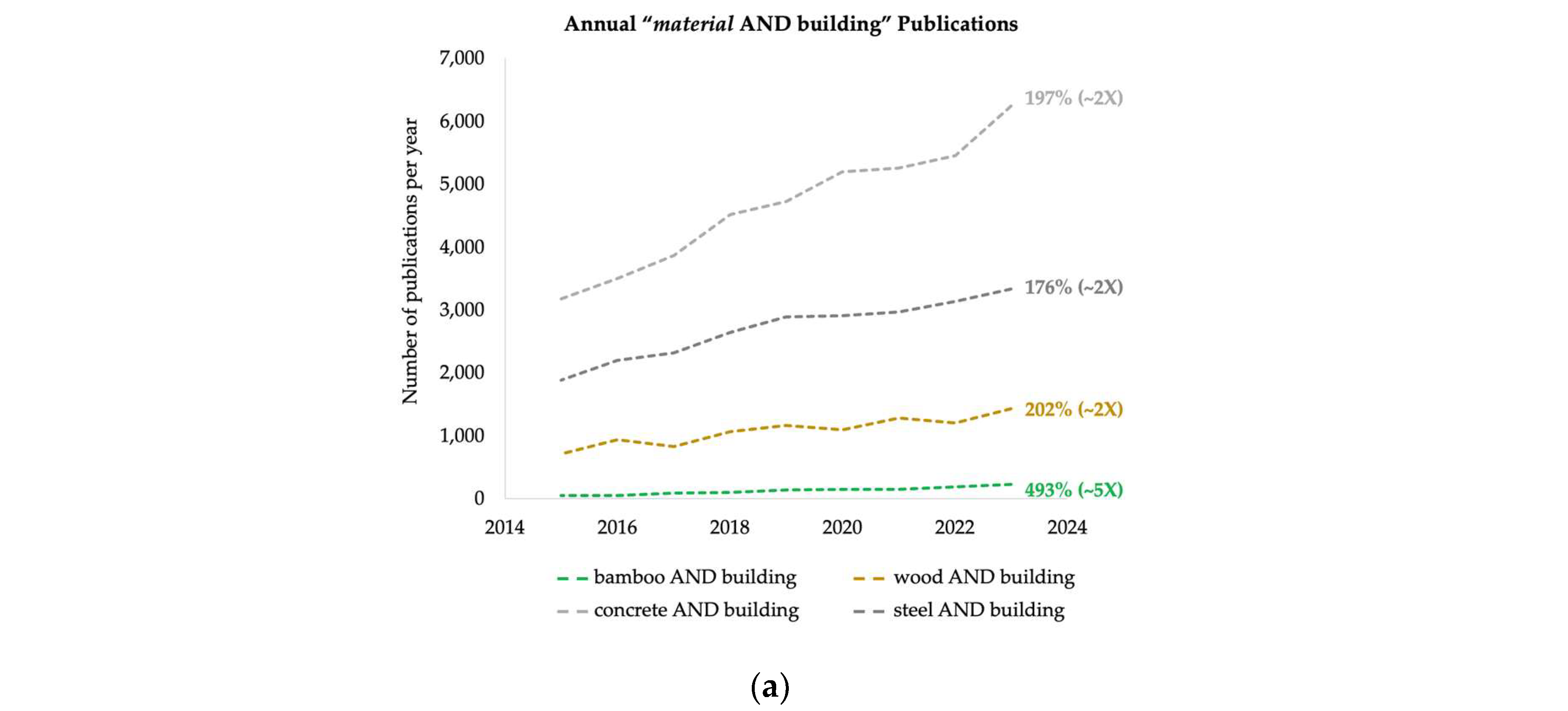

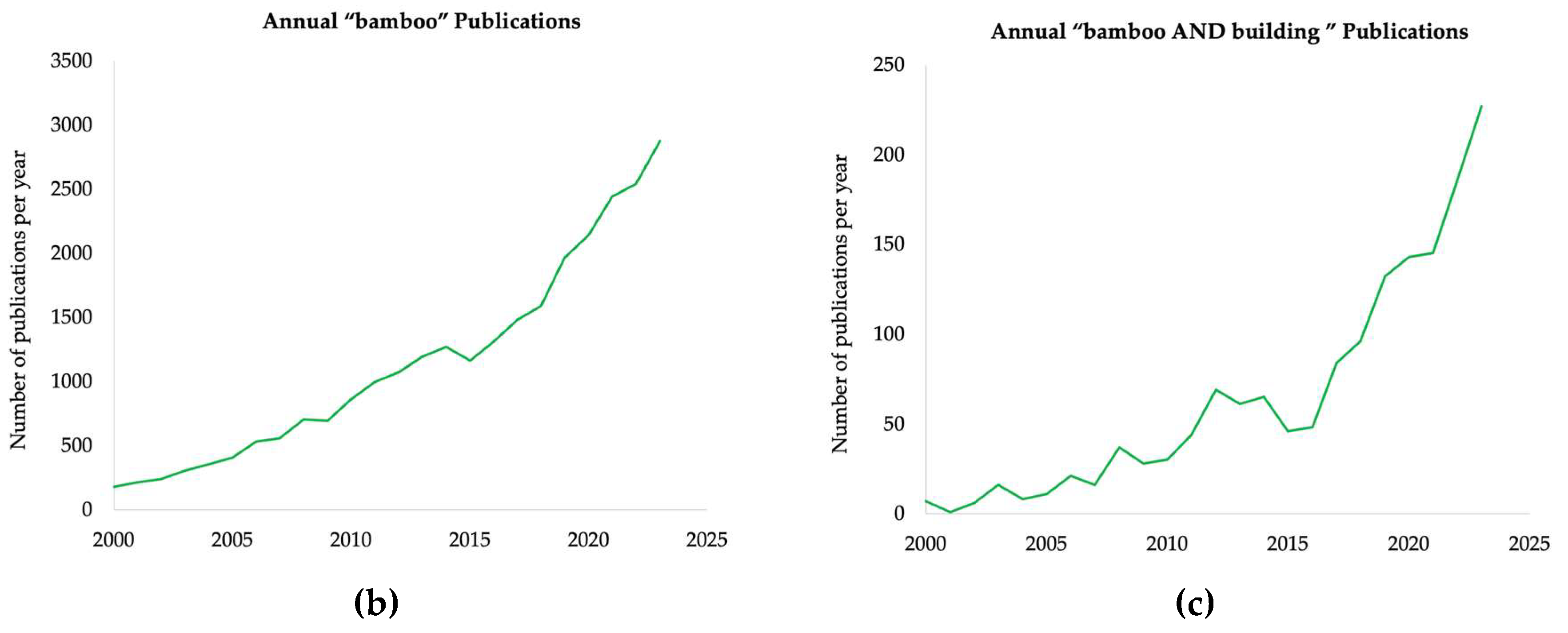

2.1. Comparative Analysis of Bamboo with Traditional Building Materials

2.2. Comparative Analysis of Bamboo with Other Biogenic Building Materials

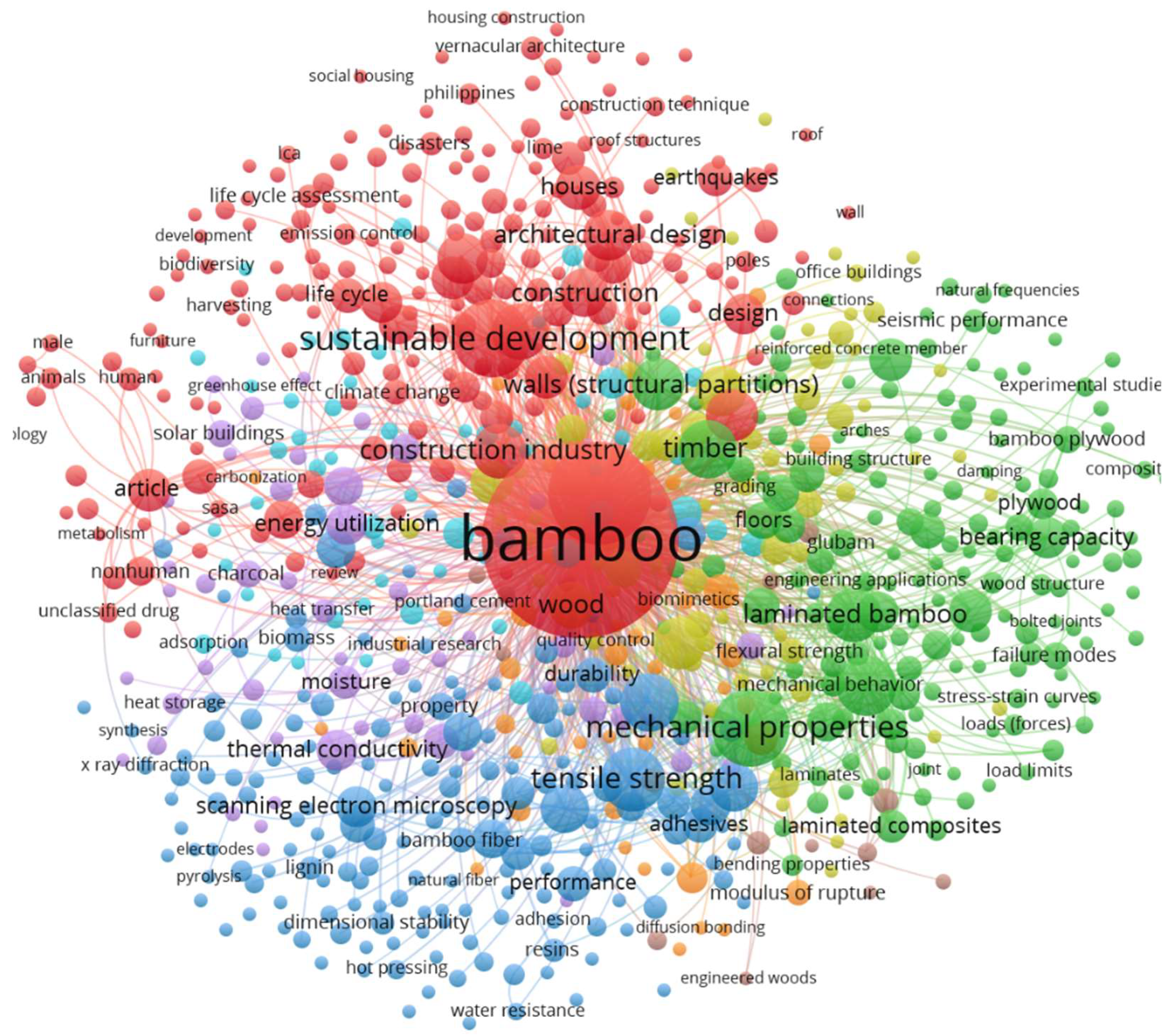

2.3. Bibliometric Network Analysis Using VOSviewer

3. The Climate and Load Bearing Promise of Timber Bamboo

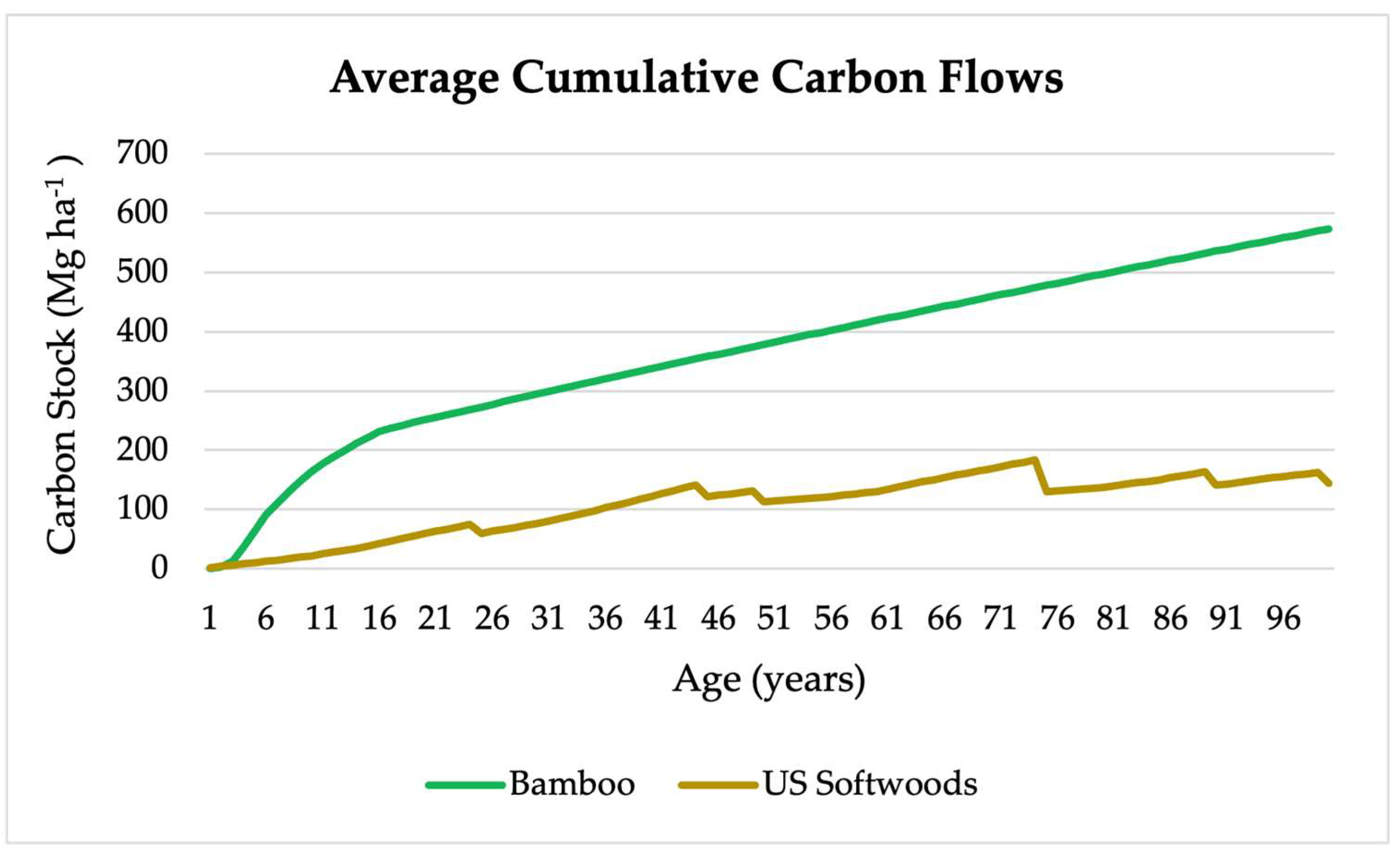

3.1. Comparative Carbon Footprint of Timber Bamboo

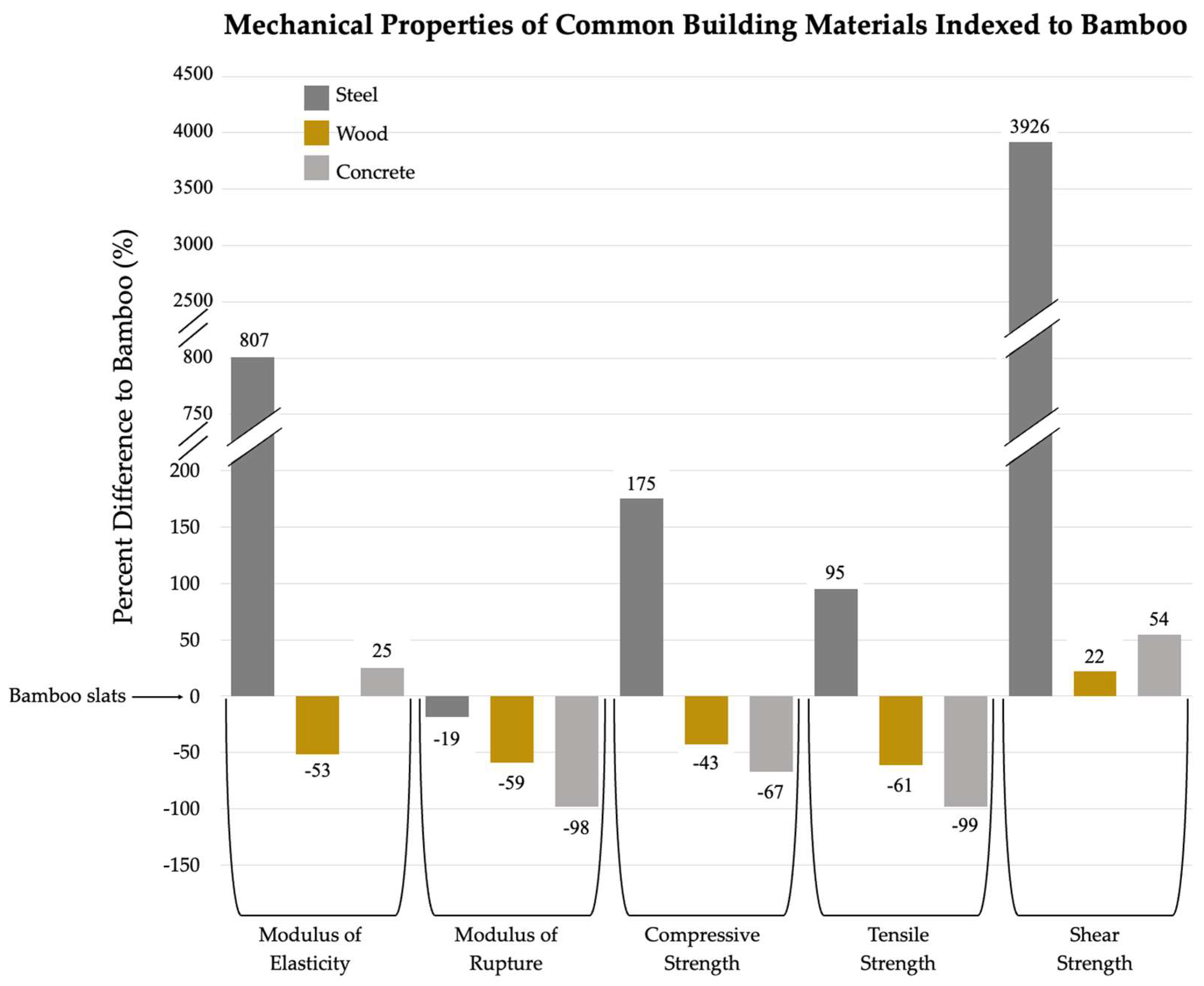

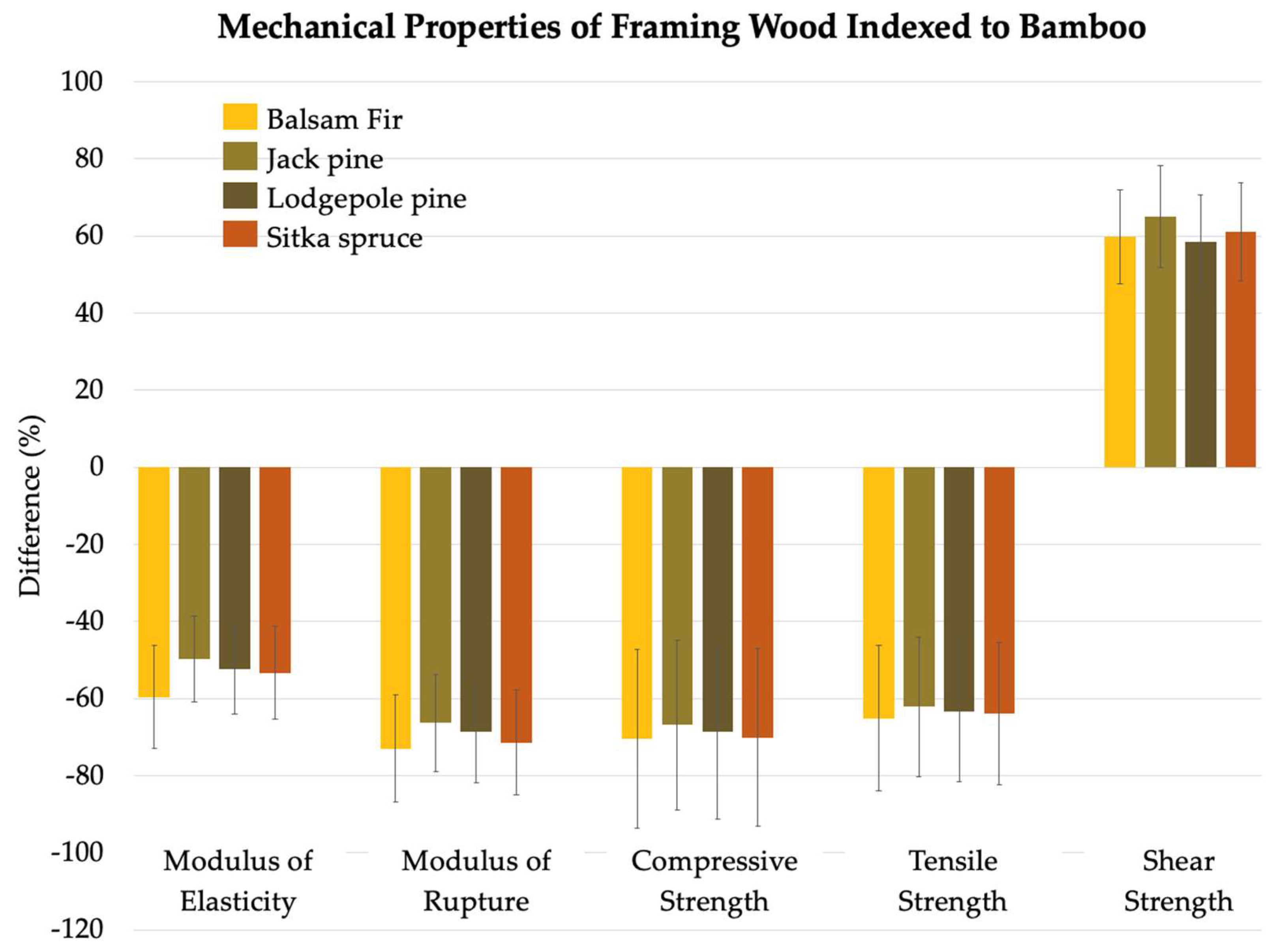

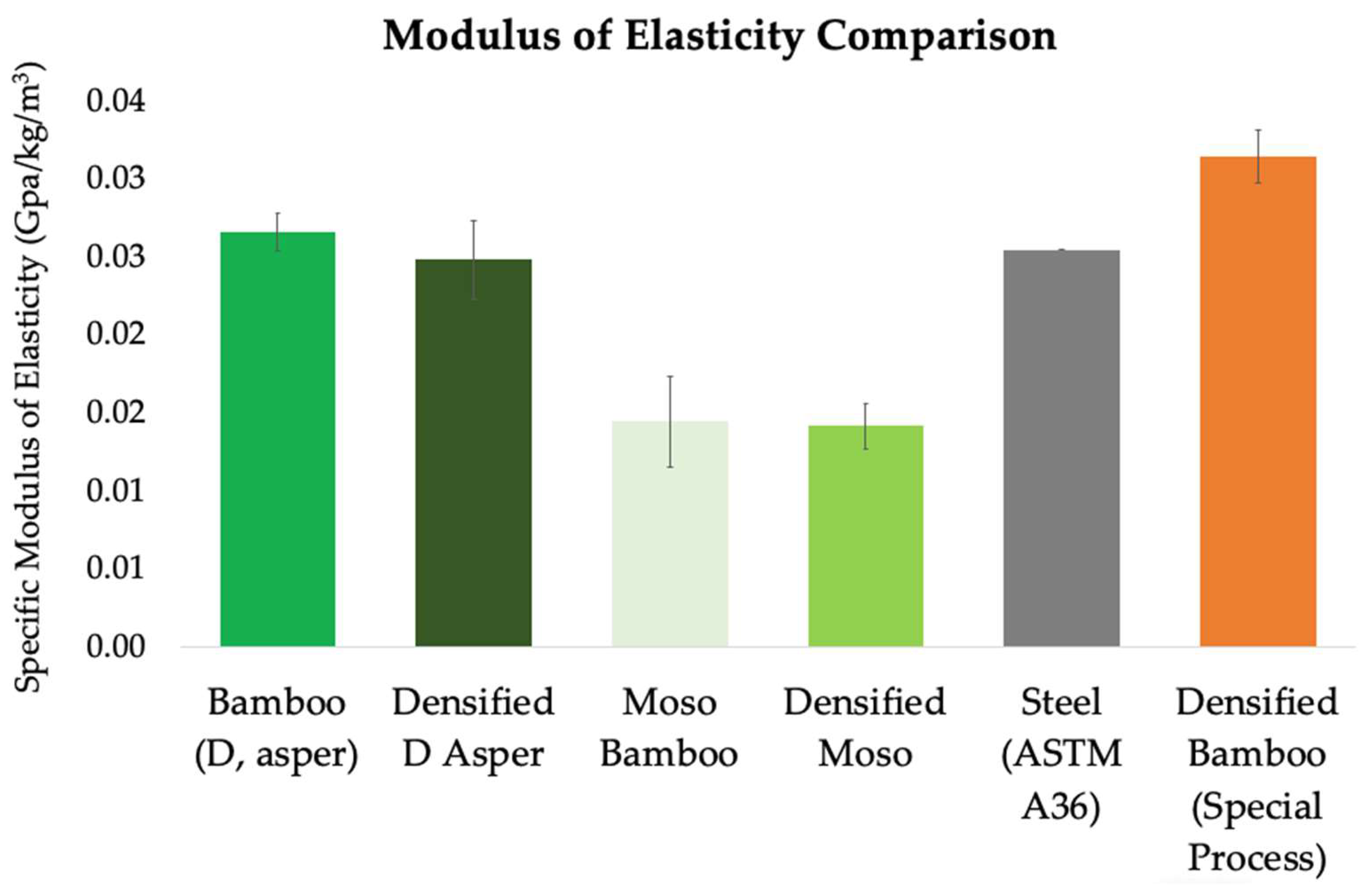

3.2. Comparative Mechanical Properties of Timber Bamboo

4. Adoption of Engineered Structural Bamboo Building Products – Problems & Possibilities

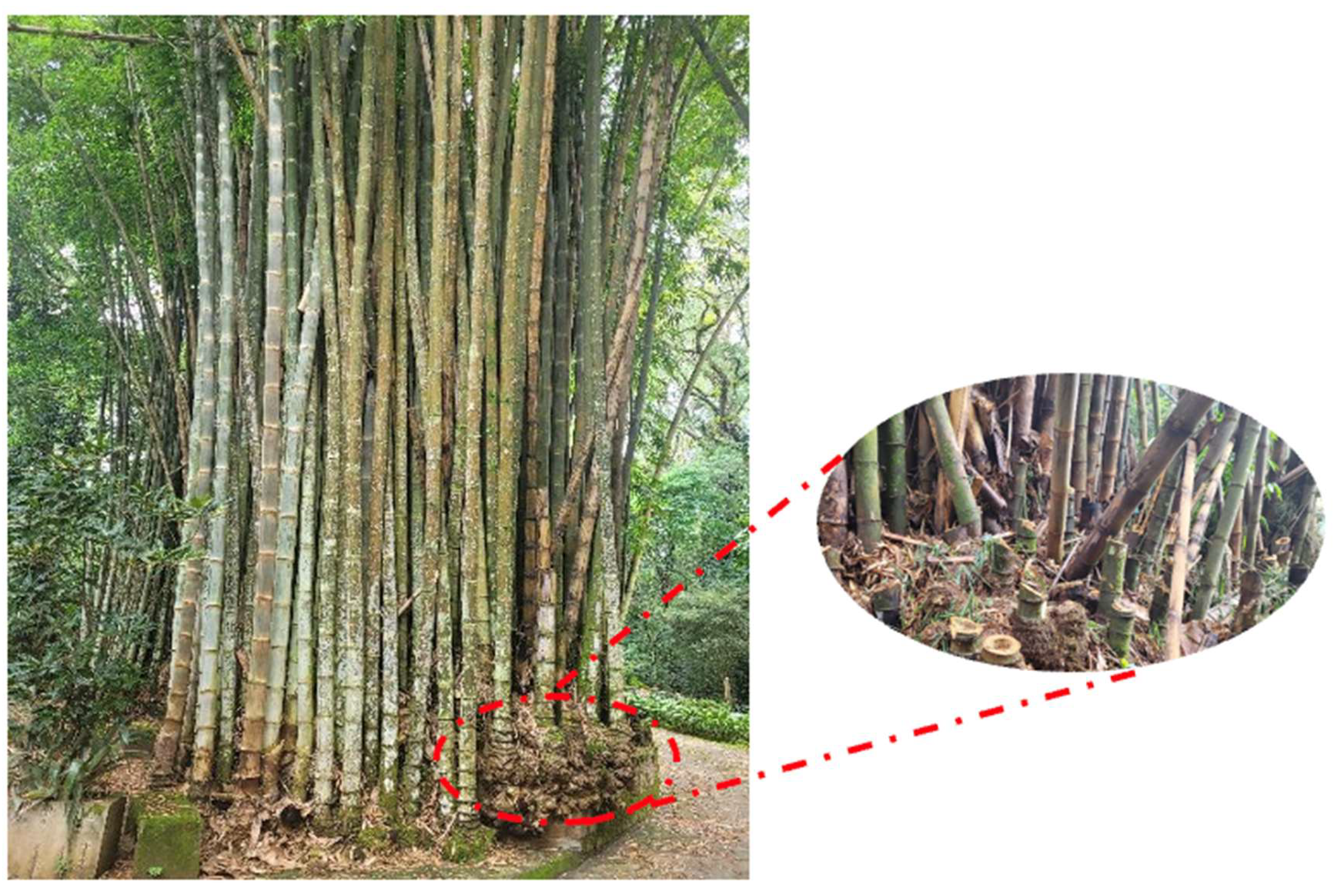

4.1. Raw Material Acquisition

4.1.a. Limited Commerical Plantations

4.1.b. Harvesting Technology

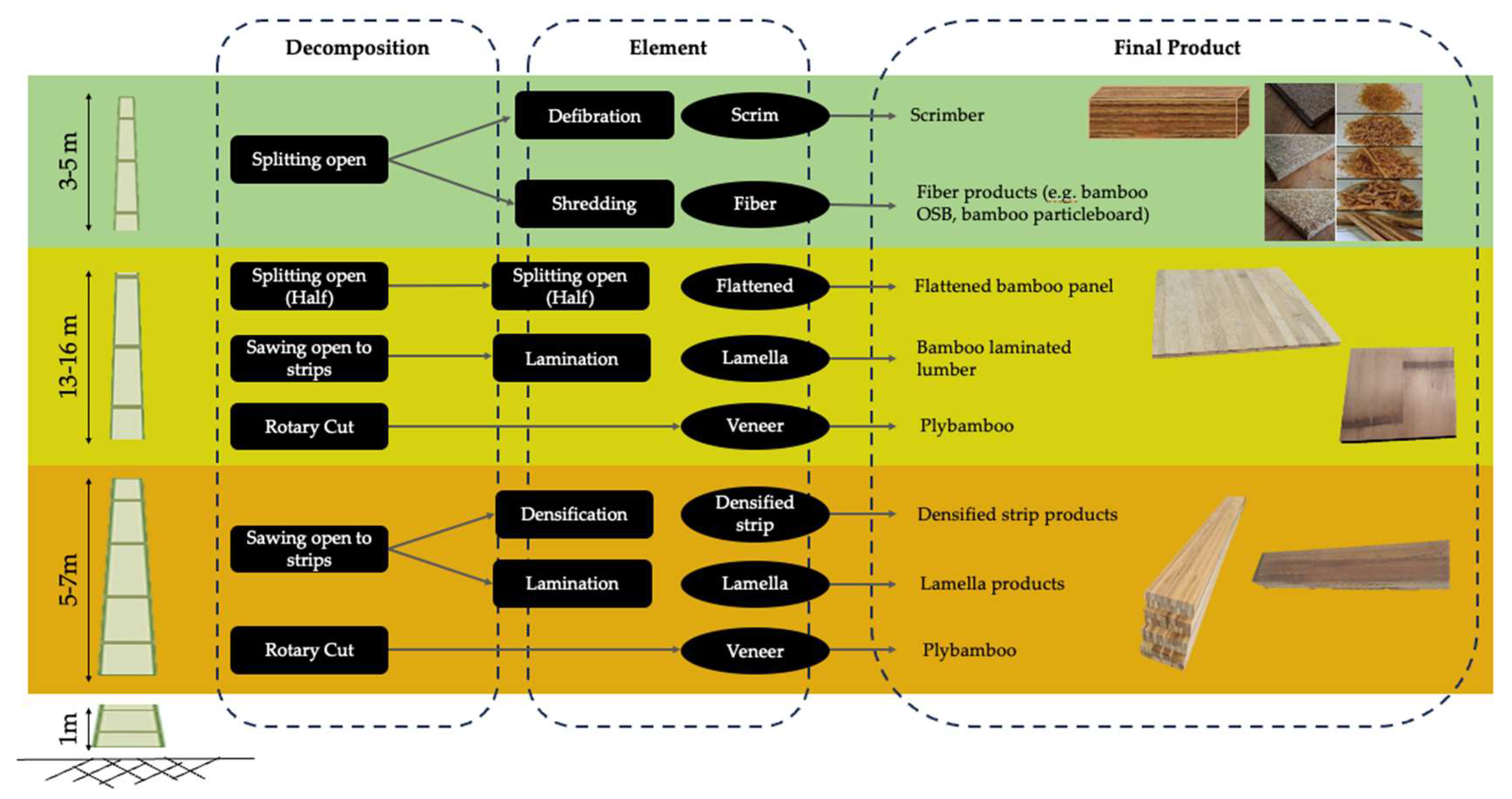

4.2. Processing and Manufacturing

- Top: 3-5 meters in length. This section is best suited for splitting open the bamboo culms, which are then defibrated or shredded to produce scrim and fiber. Due to its fibrous nature and high strength, the top section is ideal for producing scrimber and other fiber-based products.

- Middle: 13-16 meters in length. This section can be split open, sawed into strips, or rotary cut. The resulting elements include flattened strips, laminated lamella, or veneer, which are then used to create laminated bamboo lumber (LBL) and veneers. The balanced properties of the middle section make it ideal for high-quality veneers and laminated products used in flooring, paneling, and furniture.

- Bottom: 5-7 meters in length. This section is processed by sawing into strips or rotary cutting. The elements produced include densified strips or lamella, which are used to create structural components and densified strips for construction applications. The bottom section, being the densest and strongest, is best suited for structural components.

4.3. Sub-Optimal Market Application

5. Potential Carbon Impact

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaowana, P. (2013). Bamboo: An alternative raw material for wood and wood-based composites. Journal of Materials Science Research, 2(2), 90. [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, G., & Dua, S. (2022). A Critical Review of Bamboo as a Building Material for Sustainable Development. Journal of Sustainable Construction Engineering and Project Management, 4(3), 1-8.

- Kartono, B., Nik Ahmad Ariff, N. S., Purnomo, A., & Ezran, M. (2023). Bamboo material for sustainable development: A systematic review. E3S Web of Conferences, 444, Article 01011. [CrossRef]

- Sil, A. (2022). Bamboo – A green construction material for housing towards sustainable economic growth. International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology (IJIET), 13(3), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, R., Kim, J.-H., & Kim, J.-T. (2019). Environmental, social and economic sustainability of bamboo and bamboo-based construction materials in buildings. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 18(2), 49–59. [CrossRef]

- Goh, Y., Yap, S. P., & Tong, T. (2019). Bamboo: The emerging renewable material for sustainable construction. In Elsevier (Ed.), Comprehensive renewable energy. [CrossRef]

- Adier, M. F. V., Sevilla, M. E. P., Valerio, D. N. R., & Ongpeng, J. M. C. (2023). Bamboo as Sustainable Building Materials: A Systematic Review of Properties, Treatment Methods, and Standards. Buildings, 13(10), 2449. [CrossRef]

- Bundi, T., Lopez, L. F., Habert, G., & Zea Escamilla, E. (2024). Bridging housing and climate needs: Bamboo construction in the Philippines. Sustainability, 16(2), 498. [CrossRef]

- Panti, C. A. T., Cañete, C. S., Navarra, A. R., Rubinas, K. D., Garciano, L. E. O., & López, L. F. (2024). Establishing the characteristic compressive strength parallel to fiber of four local Philippine bamboo species. Sustainability, 16(3845). [CrossRef]

- Levina, A. G., & Utomo, M. M. B. (2023). Performance and development challenges of micro–small bamboo enterprises in Gunungkidul, Indonesia. Advances in Bamboo Science, 4, 100037. [CrossRef]

- Li, W., & He, S. (2019). Research on the utilization and development of bamboo resources through problem analysis and assessment. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 300(5), 052028. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., Zhang, W., Diao, X., Ji, M., Fei, B., & Miao, H. (2023). Analysis of Harvesting Methods of Moso Bamboo. Buildings, 13(2), 365. [CrossRef]

- Guerra, S. P. S., Oguri, G., Eufrade, H. J., Melo, R. X., & Spinelli, R. (2016). Mechanized harvesting of bamboo plantations for energy production: Preliminary tests with a cut-and-shred harvester. Energy for Sustainable Development, 34, 62–66. [CrossRef]

- Madhushan, S., Buddika, S., Bandara, S., Navaratnam, S., & Abeysuriya, N. (2023). Uses of Bamboo for Sustainable Construction—A Structural and Durability Perspective—A Review. Sustainability, 15(14), 11137. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme and Yale Center for Ecosystems + Architecture. (2023). Building materials and the climate: Constructing a new future. Retrieved July 17, 2024, from https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/43293.

- McKinsey & Company. (2022, October 17). Reducing embodied carbon in new construction. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved December 27, 2024, from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel-logistics-and-infrastructure/how-we-help-clients/global-infrastructure-initiative/voices/reducing-embodied-carbon-in-new-construction.

- Bitting S, Derme T, Lee J, Van Mele T, Dillenburger B, Block P. Challenges and Opportunities in Scaling up Architectural Applications of Mycelium-Based Materials with Digital Fabrication. Biomimetics (Basel). 2022 Apr 14;7(2):44. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dessi-Olive J. Strategies for Growing Large-Scale Mycelium Structures. Biomimetics (Basel). 2022 Sep 11;7(3):129. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yadav, M., & Saini, A. (2022). Opportunities & challenges of hempcrete as a building material for construction: An overview. Materials Today: Proceedings, 65(Part 2), 2021–2028. [CrossRef]

- Di Sarno, L., Albuhairi, D., & Peres Medeiros, J. M. (2024). Exploring innovative resilient and sustainable bio-materials for structural applications: Hemp-fibre concrete. Structures, 68, 107096. [CrossRef]

- Lecompte, T., & Le Duigou, A. (2017). Mechanics of straw bales for building applications. Journal of Building Engineering, 9, 84–90. [CrossRef]

- The Business Research Company. (2023). Construction Global Market Opportunities and Strategies to 2032. [PDF]. Published October 2023.

- Kumar, V., Lo Ricco, M., Bergman, R. D., Nepal, P., & Poudyal, N. C. (2024). Environmental impact assessment of mass timber, structural steel, and reinforced concrete buildings based on the 2021 international building code provisions. Building and Environment, 251, 111195. [CrossRef]

- Younis, A., & Dodoo, A. (2022). Cross-laminated timber for building construction: A life-cycle-assessment overview. Journal of Building Engineering, 52, 104482. [CrossRef]

- Ryberg, M. W., Ohms, P. K., Møller, E., & Lading, T. (2021). Comparative life cycle assessment of four buildings in Greenland. Building and Environment, 204, 108130. [CrossRef]

- Hinkle, H., McGinley, M., Hargett, T., Dascher, S. (2019). Carbon Farming with Timber Bamboo: A Superior Sequestration System Compared to Wood. BamCore. https://www.bamcore.com/_files/ugd/77318d_568cbad9ac2e443e87d69011ce5f48b2.pdf?index=true.

- U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2003). Fixed assets and consumer durable goods in the United States, 1925–99. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Yiping, L., Yanxia, L., Buckingham, K., Henley, G., & Guomo, Z. (2010). Bamboo and Climate Change Mitigation. INBAR Technical Report 32. International Network for Bamboo and Rattan (INBAR).

- Nath, A. J., Lal, R., & Das, A. K. (2015). Managing woody bamboos for carbon farming and carbon trading. Global Ecology and Conservation, 3, 654-663. [CrossRef]

- slam Sohel, M. S., Alamgir, M., Akhter, S., & Rahman, M. (2015). Carbon storage in a bamboo (Bambusa vulgaris) plantation in the degraded tropical forests: Implications for policy development. Land Use Policy, 49, 142–151. [CrossRef]

- Yuen, J. Q., Fung, T., & Ziegler, A. D. (2017). Carbon stocks in bamboo ecosystems worldwide: Estimates and uncertainties. Forest Ecology and Management, 393, 113-138. [CrossRef]

- Kuehl, Y., Henley, G., & Yiping, L. (Eds.). (n.d.). The climate change challenge and bamboo: Mitigation and adaptation (INBAR Working Paper No. 65). Edited by A. Benton. International Network for Bamboo and Rattan (INBAR).

- Kadivar, M., Gauss, C., Mármol, G., de Sá, A. D., Fioroni, C., Ghavami, K., & Savastano Jr., H. (2019). The influence of the initial moisture content on densification process of D. asper bamboo: Physical-chemical and bending characterization. Construction and Building Materials, 229, Article 116896. [CrossRef]

- Kadivar, M., Gauss, C., Stanislas, T. T., Ahrar, A. J., Charca, S., & Savastano, H. (2022). Effect of bamboo species and pre-treatment method on physical and mechanical properties of bamboo processed by flattening-densification. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 291, Article 126746. [CrossRef]

- Adam, N., & Jusoh, I. (2019). Physical and mechanical properties of Dendrocalamus asper and Bambusa vulgaris. Transactions on Science and Technology, 6(1-2), 95–101.

- Zakikhani, P., Zahari, R., Sultan, M. T. b. H. H., & Majid, D. L. A. A. (2017). Morphological, mechanical, and physical properties of four bamboo species. BioResources, 12(2). [CrossRef]

- Awalluddin, D., Mohd Ariffin, M. A., Osman, M. H., Hussin, M. W., Ismail, M. A., Lee, H.-S., & Abdul Shukor Lim, N. H. (2017). Mechanical properties of different bamboo species. MATEC Web of Conferences, 138, 01024. [CrossRef]

- Glória, G. O., Margem, F. M., Ribeiro, C. G. D., de Moraes, Y. M., da Cruz, R. B., Silva, F. A., & Monteiro, S. N. (2015). Charpy impact tests of epoxy composites reinforced with giant bamboo fibers. Materials Research, 18(Suppl 2), 178-184. [CrossRef]

- Siam, N. A., Uyup, M. K. A., Hamdan, H., Mohmod, A. L., & Awalludin, M. F. (2019). Anatomical, physical, and mechanical properties of thirteen malaysian bamboo species. BioResources, 14(2), 3925-3943. [CrossRef]

- Russ, N. M., Hanid, M., & Ye, K. M. (2018). Literature review on green cost premium elements of sustainable building construction. International Journal of Technology, 9(8), 1715-1725. [CrossRef]

- FAO. 2020. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020: Main report. Rome. [CrossRef]

- WBO (2024). 2024 Global Bamboo Plantation Resource Survey Results Report.

- Daniell, J., Wenzel, F., Khazai, B., & Vervaeck, A. (2011). A country-by-country building inventory and vulnerability index for earthquakes in comparison to historical CATDAT damaging earthquakes database losses. Paper presented at the Australian Earthquake Engineering Society 2011 Conference, November 18–20, Barossa Valley, South Australia.

- Forisk Consulting. (2024, May 9). North America’s top timberland owners and managers: 2024 update. Retrieved December 31, 2024, from https://forisk.com/blog/2024/05/09/north-americas-top-timberland-owners-and-managers-2024-update/.

- Travasso, S. M., Thomas, T., Makkar, S., John, A. T., Webb, P., & Swaminathan, S. (2023). Contextual factors influencing production, distribution, and consumption of nutrient-rich foods in bihar, india: a qualitative study of constraints and facilitators. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 44(2), 100-115. [CrossRef]

- World Resources Institute. (December 23, 2014). Rebranding bamboo: The Bonn 5 million hectare restoration pledge. Retrieved December 31, 2024, from https://www.wri.org/insights/rebranding-bamboo-bonn-5-million-hectare-restoration-pledge.

- King, C., van der Lugt, P., Thang Long, T., & Yanxia, L. (2021). Integration of Bamboo Forestry into Carbon Markets. International Bamboo and Rattan Organisation (INBAR).

- Picchi, G., Sandak, J., Grigolato, S., Panzacchi, P., Tognetti, R. (2022). Smart Harvest Operations and Timber Processing for Improved Forest Management. In: Tognetti, R., Smith, M., Panzacchi, P. (eds) Climate-Smart Forestry in Mountain Regions. Managing Forest Ecosystems, vol 40. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Lindroos, O., La Hera, P. X., & Häggström, C. (2017). Drivers of advances in mechanized timber harvesting: A selective review of technological innovation. Croatian Journal of Forest Engineering, 38(2), 243–258.

- Darabant, A., Rai, P.B., Staudhammer, C.L. et al. Designing and Evaluating Bamboo Harvesting Methods for Local Needs: Integrating Local Ecological Knowledge and Science. Environmental Management 58, 312–322 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y., Li, S., Xiong, J., Xu, B., Liu, P., & Li, H. (2021). Design of bamboo cutting mechanism based on crack propagation principle. BioResources, 16(3), 5890-5900. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., & Cheng, K. J. (2020). Effect of glow-discharge plasma treatment on contact angle and micromorphology of bamboo green surface. Forests, 11(1293). [CrossRef]

- Wu, S., Liang, L., Chen, F., Yang, Z., Zheng, Y., Wu, Y., Li, L., Lou, G., Dai, J., Pang, Y., Chen, H., Fang, Q., & Shen, Z. (2022). Improving the wet adhesive bonding of bamboo urea-formaldehyde adhesive using styrene acrylate by controlling monomer ratios. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. [CrossRef]

- Scurlock, J. M. O., Dayton, D. C., & Hames, B. R. (2000). Bamboo: an overlooked biomass resource? Biomass and Bioenergy, 19(4), 229-244. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W., Fang, Z., Fan, S., & Deng, S. (2022). Evaluation of the Moso bamboo age determination based on laser echo intensity. Remote Sensing, 14(2550). [CrossRef]

- GIM International. (April 26, 2023). LiDAR technology for scalable forest inventory. Retrieved December 31, 2024, from https://www.gim-international.com/content/article/lidar-technology-for-scalable-forest-inventory.

- Yang, Z., Meng, X., Zeng, G., Wei, J., Wang, C., & Yu, W. (2024). Effect of resin content on the structure, water resistance, and mechanical properties of high-density bamboo scrimbers. Polymers, 16(6), Article 797. [CrossRef]

- Liang, L., Zheng, Y., Wu, Y., Yang, J., Wang, J., Tao, Y., Li, L., Ma, C., Pang, Y., Chen, H., & et al. (2021). Surfactant-induced reconfiguration of urea-formaldehyde resins enables improved surface properties and gluability of bamboo. Polymers, 13(3542). [CrossRef]

- Abidin, W. N. S. N. Z., Al-Edrus, S. S. O., Hua, L. S., Ghani, M. A. A., Bakar, B. F. A., Ishak, R., Qayyum Ahmad Faisal, F., Sabaruddin, F. A., Kristak, L., Lubis, M. A. R., & et al. (2023). Properties of phenol formaldehyde-bonded layered laminated woven bamboo mat boards made from Gigantochloa scortechinii. Applied Sciences, 13(47). [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J., Zhi, Z., Zhang, E., Yu, Y., & Wu, Q. (2022). Design and evaluation of bamboo-based elastic cushion by human pressure distribution. In Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications: Design Studies and Intelligence Engineering (Vol. 347, pp. 321-328). IOS Press. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., & Cheng, K. J. (2020). Effect of Glow-Discharge Plasma Treatment on Contact Angle and Micromorphology of Bamboo Green Surface. Forests, 11(12), 1293. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Chen, C., Mi, R., Gan, W., Dai, J., Jiao, M., Xie, H., Yao, Y., Xiao, S., & Hu, L. (2020). A strong, tough, and scalable structural material from fast-growing bamboo. Advanced Materials, 32(8), Article 1906308. [CrossRef]

- World Green Building Council. (2019). Bringing embodied carbon upfront. https://worldgbc.org/advancing-net-zero/embodied-carbon/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2020). CO₂ emissions. Our World in Data. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions.

- Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2020). CO₂ emissions. Our World in Data. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions.

- Cabeza, L. F., Boquera, L., Chàfer, M., & Vérez, D. (2021). Embodied energy and embodied carbon of structural building materials: Worldwide progress and barriers through literature map analysis. Energy and Buildings, 231, 110612lysis. [CrossRef]

| Factor | Property Affected |

| Variation in number of fibers in the culm wall | Poisson’s ratio, density, creep, and deformation |

| Variation in cross-section along the length of the culm | Density, elastic modulus, shrinkage, creep, deformation, and tensile strength |

| Moisture content | Elastic modulus, compressive strength, bending strength, shear strength, shrinkage, creep, and deformation |

| Age of culm | Shrinkage, creep and deformation |

| Environmental growth conditions |

Poisson’s ratio, elastic modulus, compressive strength, and tensile strength |

| Material | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Structural Steel | High Strength-to-Weight Ratio: Ideal for high-rise buildings and long-span bridges. Ductility: Significant deformation before failure, providing reserve strength. Predictable Properties: Reliable material properties for structural design. Speed of Erection: Quick construction, reducing labor costs. Ease of Repair: Easily repairable, minimizing downtime. Adaptability: Suitable for prefabrication and mass production. Reusability: Promotes sustainability and cost-effectiveness. Fatigue Strength: Good fatigue resistance, ensuring long-term integrity. |

Cost: Energy-intensive and relatively expensive production. Fireproofing: Loses strength at high temperatures, requiring fireproofing. Maintenance: Susceptible to corrosion, needing regular maintenance. Buckling Susceptibility: Prone to buckling in compression members, needing careful design. |

| Reinforced Concrete | Compressive Strength: High compressive strength for various applications. Tensile Strength: Withstands considerable tensile stress when reinforced. Fire Resistance: Effective fire protection for embedded steel. Locally Sourced Materials: Promotes cost-effectiveness and sustainability. Durability: Highly durable with minimal maintenance. Moldability: Can be molded into various shapes. Low Maintenance: Reduces long-term operational costs. Rigidity: Minimal deflection for stability. User-Friendliness: Requires less skilled labor compared to steel. |

Long-Term Storage: Cannot be stored once mixed, affecting scheduling. Curing Time: Requires significant curing period, delaying construction. Cost of Forms: High formwork costs impacting budgets. Shrinkage: Prone to shrinkage, leading to cracks and strength loss. |

| Traditional North American Framing Wood | Tensile Strength: Outperforms steel in breaking length, allowing for larger spaces. Electrical and Heat Resistance: Naturally resistant to electrical conduction and heat. Sound Absorption: Minimizes echo for enhanced comfort. Locally Sourced: Renewable and promotes sustainability. |

Shrinkage and Swelling: Affected by moisture levels, impacting stability. Deterioration: Prone to decay, mold, and insect damage, requiring maintenance. |

| Timber Bamboo | Rapid Growth: Fast-growing renewable resource. High Strength-to-Weight Ratio: Suitable for lightweight structures. Flexibility: High flexibility and resilience under stress. Eco-Friendly: Low environmental impact and carbon footprint. Cost-Effective: Generally cheaper than steel and concrete. Thermal Insulation: Provides good thermal insulation properties. |

Durability: Susceptible to decay and pests without proper treatment. Uniformity: Natural variability in quality and dimensions. Moisture Sensitivity: Prone to swelling and shrinkage due to moisture. Fire Resistance: Lower fire resistance compared to concrete. |

| Section | Top | Middle | Bottom |

| Size | 3-5 meters | 13-16 meters | 5-7 meters |

| Decomposition | Splitting open the bamboo culms | Splitting open, sawing open to strips, or rotary cutting | Sawing open to strips or rotatory cutting |

| Element | Defibration or shredding to produce scrim and fiber | Producing flattened strips, laminated lamella, or veneer | Producing densified strips or lamella |

| Final Product | Scrimber and fiber-based products | Laminated bamboo lumber (LBL) and veneers | Densified bamboo strips and structural elements |

| Suitability | Best for producing scrimber due to its fibrous nature and high strength | Ideal for producing high-quality veneers and laminated products used in floor, panelling, and furniture due to its balanced properties | As the densest and strongest section, best for creating structural components and densified strips for construction applications |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).