1. Introduction

The general context of this research is characterized by new and more demanding challenges for the development of the current society. The complex nature of human activities begins to affect the environment therefore it is important to find methods to decrease their impact on the nature. One of the sectors that puts a lot of pressure on the environment is the sector of construction given the increasing demand, all over the world, for new buildings.

The current construction technology is responsible, worldwide, for big amounts of anthropogenic pollutants due to the use of large quantities of energy from the extraction of raw materials, the production of building materials and in the process of construction. According to the report [

1], the sector accounted for 36 percent of global final energy consumption and 37 per cent of energy related CO

2 emissions. The data presented in [

2] reveals that in UK the second largest source of greenhouse gas emissions is the building sector. The buildings sector contributed 20% of total UK emissions in 2021, of which the majority came from homes.

The escalating effects of climate change have placed global emphasis on the importance of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and achieving net zero emissions by the middle of this century. As such, there is an increasing demand for sustainable building material alternatives to reduce the environmental impact of the construction industry [

3]. Using wood as a building material seems to be a good way to respond to these demands as wood is a sustainable natural material that not only need low quantity of energy to be produced but it also traps CO

2 during the life of structure [

4]

. Humans have always relied on wood for their various needs, agricultural tools, building materials, fuel, weapons for hunting and warfare, until the last half of the 19th century, wood was the main material used for construction and power generation energy

. Wood is a material with great mechanical and thermal properties that is naturally occurring, renewable, and biodegradable. Wood is a naturally occurring, renewable building material with anisotropic (inhomogeneous) properties that is composed of numerous plant cells arranged into specialized tissues, also known as anatomical elements, that are quite different [

4]. Wood is one of the older materials in terms of its use in architectural structure and design, but it is certainly not an outdated choice. Wood offers unique properties not found in steel and concrete, and new wood construction practices are continually being introduced to the industry. The environmental impact during the production and end-of-life phases of wood material is generally much lower than that of equivalent materials produced from inorganic or fossil raw materials [

5]. Moreover, unlike resources of agricultural origin, wood does not compete with food [

6]. As a result, since the beginning of the 21st century and in addition to traditional uses, there has been an increase in the consumption of wood for new applications (energy production, building materials, chemicals, etc.) [

7]. Using timber in construction has increased in recent decades [

8].

Wood is the main product of the forests which play an important role in economy and in the society. As highlighted in [

9] forests as important they were in the past, they are essential for the future also. Forests are a natural ally in adapting to and fighting against climate change and will play a vital role in making Europe the first climate neutral continent by 2050. Forests are a huge treasure, as sought after and necessary as other sources of raw materials. Tree trunks and crowns are true accumulators of solar energy and stores of precious organic matter [

10]. Forests covers 45% of the European territory and more than 25% of the population depends on the forest for subsistence and income [

11].

Given the big importance of the forests and its products to the wellbeing of the human society it is important to emphasize that any research and discussion related to the use of wood in any form, including wood as a building material, must consider only legal wood harvested. Illegal harvesting is an important global problem with significant negative economic, environmental and social impact. At the European Union level constant efforts are taken to combat deforestation by adopting the EU Action Plan on Forest Law Enforcement Governance and Trade [

12]. Going further, the idea of sustainability can also be emphasized by using wood from sustainably managed forests, so that logging activities are complemented with reforestation activities, thus making maximum use of the wood benefits.

Research purpose

The general context briefly described above highlights the need to better understand the use of wood as a construction material. A lot of questions appear when discussing about wood as a building material like Can wood replace concrete or steel? Is it a material that resist in time? If is a good material, why is it not widely used? How do we need to understand the behavior od wood as building material? and the list can go on. In this sense the general research question of this study can be easy to formulate “What do we really know about wood as a building material?” but quite complicated to answer.

The research procedure used to find answer to the research questions include a scientometric analysis of the literature and an in-depth analysis completed with an wood expert perspective. The main data used for this study were extracted from the Clarivate Web of Science database and for a more coherent extraction of data the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) method was used.

The document is formatted in accordance with the format for scientific papers. The study's methodologies and methodology are offered after a brief introduction and statement of the study's objectives. The key findings from the research are reported in the following section of the paper, together with the responses to the research question. The key results are presented in the paper's final section, along with a list of the sources consulted for this research.

2. Materials and Methods

According to the purpose of the paper the needed data were obtained by interrogating one of the most important scientific databases Clarivate Web of Science Core Collection (WoS) then the data were process using specific software. The working plan of these methods includes the selection of articles in a sample database followed by filtering and refining the bibliographic data.

2.1. Data Collection

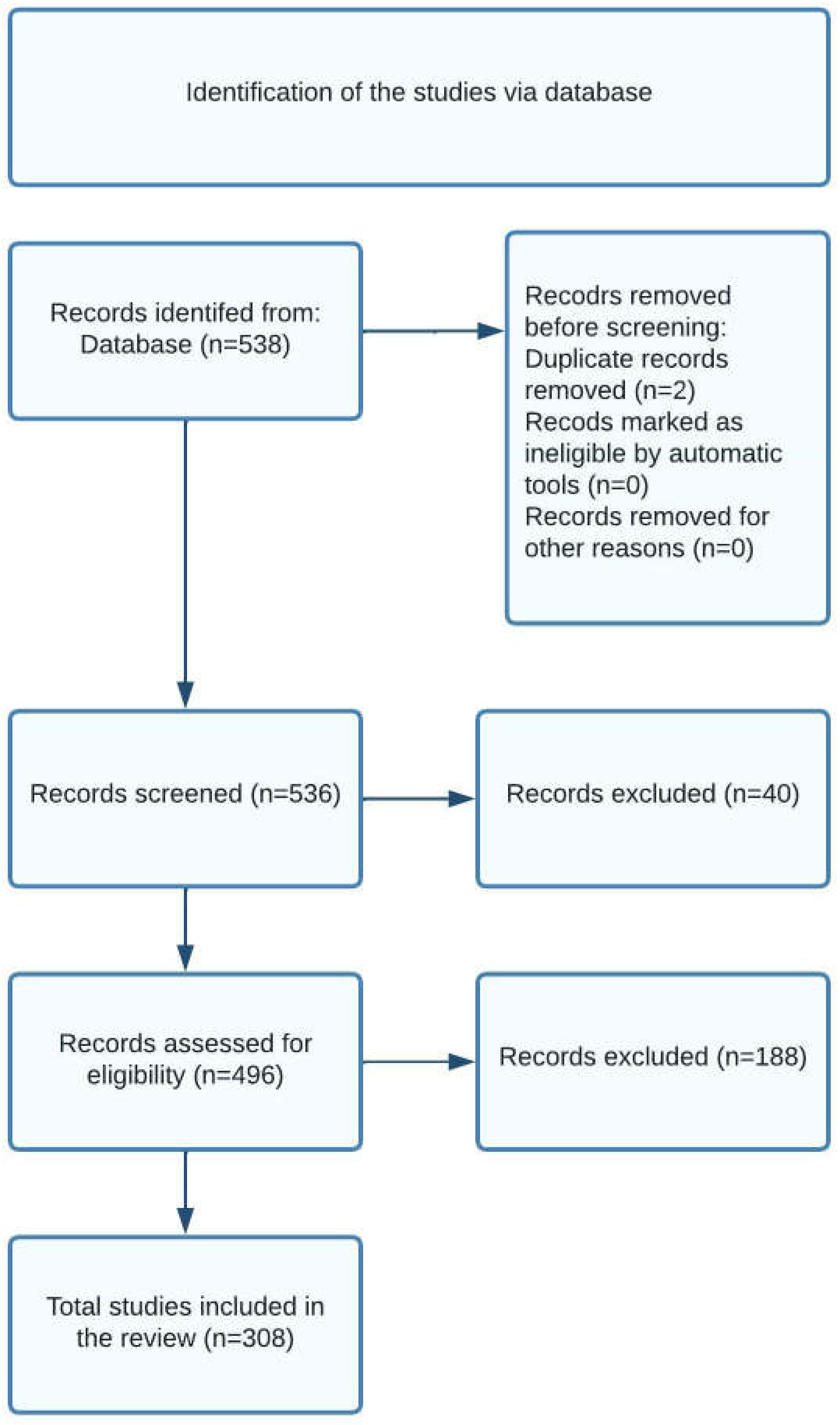

The entire process of interrogating the database is illustrated in

Figure 1. The keywords used for this study were “wood construction” or “timber construction” or “lumber construction” and the main filters to limiting the results were related to selection of only paper types “article” or “review” written in English language. The graph presented in

Figure 1 was generated using LucidChart software [

13].

The initial interrogation of the database revealed a number of 11 680 papers having their topic of wood construction or timber construction or lumber construction. The search was filtered such as to include only the papers that have the keywords in their title, so the number of articles decrease to 1 011. By selecting the paper type to article or review and the written language to English the number of records that were further analyzed decrease to 538 papers.

The systematic review was guided by the standards of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) 2020 Statement, proposed by the researchers Moher et al. [

14] and updated by [

15]. The process is represented in

Figure 2. According to their research, the PRISMA approach indicates four steps to identify and extract the data: identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion.

The identification step started with the articles resulted from the interrogation of the WoS database, 538 studies. Two papers were excluded in this step due to lack of data or duplication. The next step, a time consuming one, was the screening process which imply the assessment of the records by title and abstract, 40 papers were excluded from this study. The reasons for excluding the papers were related mainly to the lack of relevance for the purpose of this study, the majority of the excluded papers were focused on subjects like urea assisted water splitting, hydrogel and solar evaporator, construction of a porous carbon skeleton in wood tracheids, material transport, archaeological studies, different studies on the diseases of species of wood, construction of termites, soil treatments using wood waste or the construction of musical instruments, aircrafts, boats.

For the eligibility step 496 papers were analyzed by searching the full-text articles. Given the purpose of this paper and the big number of records remaining after applying the previous filtration steps, the eligibility criteria included, in addition to access to a full-text version that fits the topic addressed, an additional criterion related to the topicality of the work, thus mainly studies from the last years were consider. Other papers excluded in this step were those focused on other research areas than civil engineering, construction building technology, materials science and related. The final number of papers included in the sample database is 308.

2.2. Data Extraction and Analysis

The analysis of the raw data was performed by exporting the journal articles identified in the scientific database in a plain text file format. The format of the export data file was chosen based on the files supported by the software used. In this research, the data analysis, was done using the software Bibliometrix (version 3.1), developed by Massimo Aria and Corrado Cuccurullo, Department of Economics and Statistics, University of Naples Federico II, Italy [

16].

The information obtained by exporting the data from the scientific database contains the full range of resources available, the title of the article, the author keywords, the keywords plus, the author’s name and the citation information, including the reference list of all the articles. In order to use the data in the software, the exported data need to be further analyzed and processed; this was done manually. The reason behind this is the fact that in order to generate accurate results, Bibliometrix software need a certain uniformity in the format information. This is also one of the reasons for working more with the Web of Science database, due to its greater uniformity in the exported data. The process of data standardization occupied a large percentage of the time needed to complete the study.

3. Results and Interpretation

3.1. The Evolution of the Annual Number of Published Articles

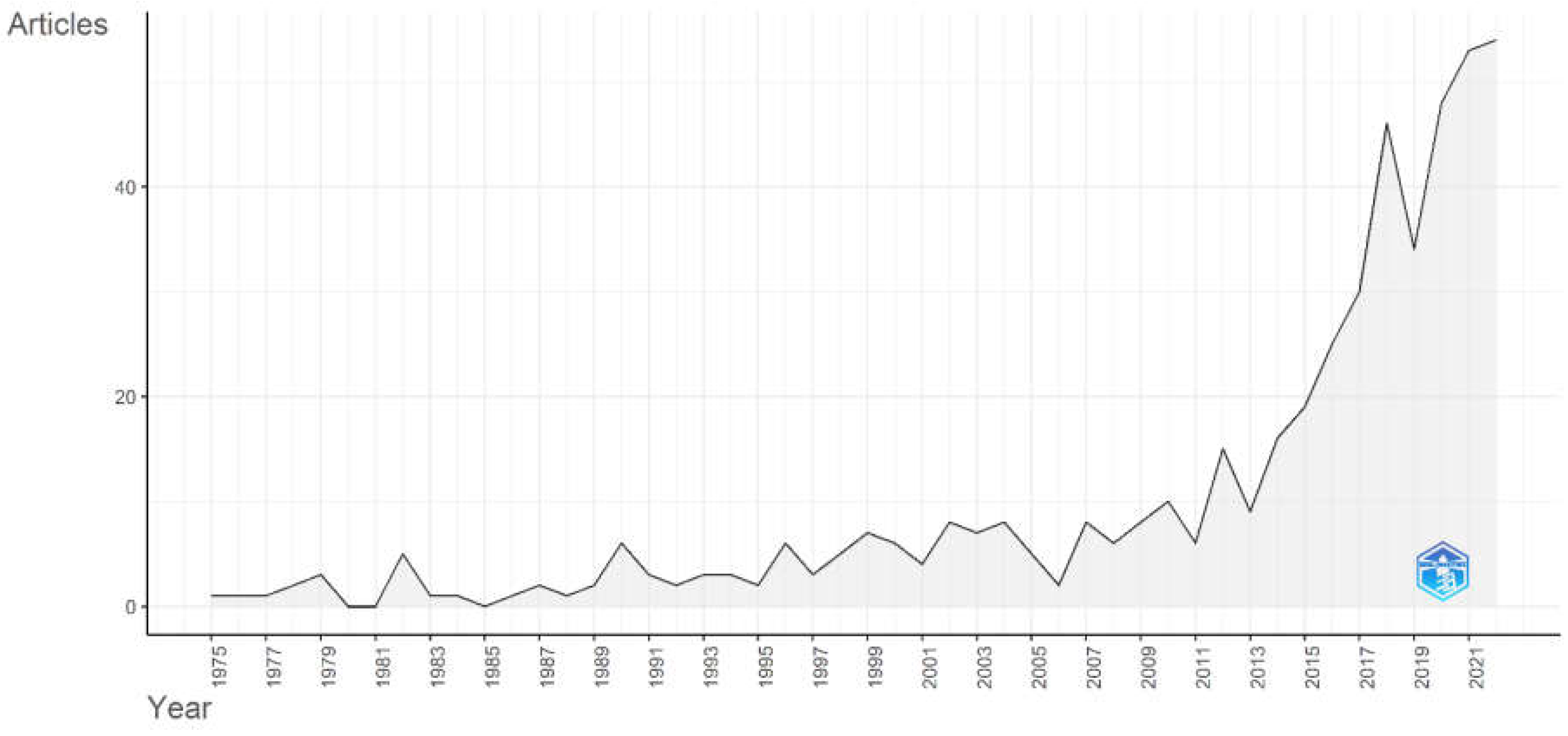

The interest for a certain subject can be seen also in the number of papers published annually. To illustrate the evolution of the annually published number of papers having “wood construction” as topic, a graph was generated (

Figure 3) based on the data extracted from WoS database. Given that the purpose of this graph was just to have a general perspective of the evolution of the interest for the subjects related to the use of wood in construction, the graph was generated using all the paper identified by interrogating the WoS database, before the screening process.

The grouping of the articles according to their publication years was taken directly from the WoS database, without a detailed verification of the publication year. The graph indicates on the x-axis the years of publication and on the y-axis the number of articles published each year.

Judging by the number of the papers published each year it can be observed that in the last years the interest to study the use of wood in construction increase substantially. The data presented in figure 3 indicate that the number of papers published each year, having the subject wood in construction, was quite small up to 2012, each year being published less than 10 papers. The first year in which more than 10 articles were published was in 2012, when 17 articles were published. The following year, in 2013, a decrease in the number of articles followed, with only 9 articles being published, and then, starting with 2014, the number of articles began to increase substantially, reaching over 50 articles published annually in 2021. In 2022, up to November, there are already indexed in the WoS database 55 papers. The increase interest in this topic can have multiple explanations, including the fact that in the last years the number of published papers increased substantially in all areas of research. However, if we take into account the increased importance given to issues related to environmental protection and the multiple crises that society is forced to go through, it can be considered that the interest for a better understanding and use of wood in the construction activity will continue to grow.

3.2. The Trend Topic in Wood Constructions

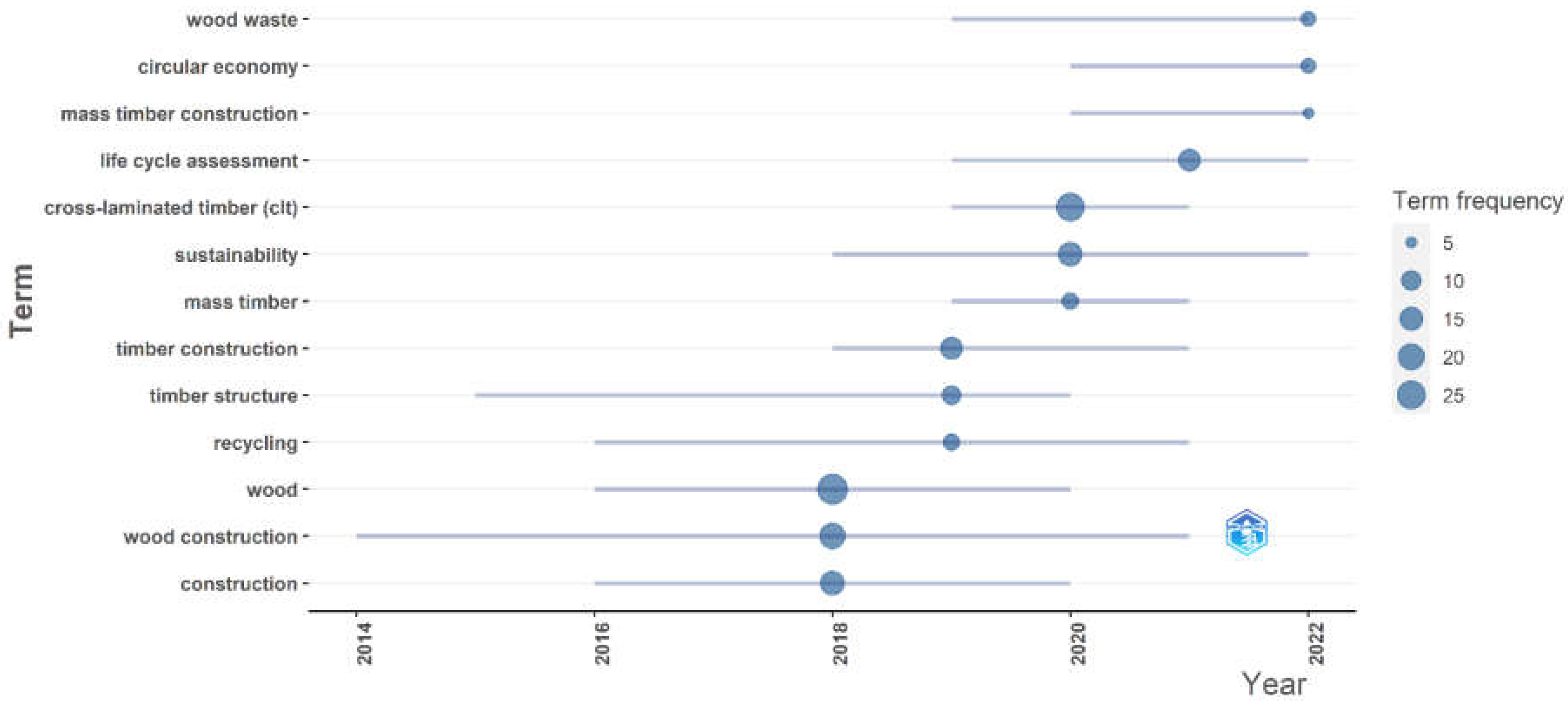

The evolution of the annual number of published articles reveals an increase interest for the use of wood as a building material in the last years. For a better understanding of the main subject approached by the researchers a trend topic graph is presented in

Figure 4. The graph was generated with the help of Bibliometrix software based on data extracted from WoS database. The trend topic was constructed based on the keywords used by the authors with a minimum word frequency of 5 and the number of words considered each year was set to 3. The graphic representation of the analysis performed by the software consists of a series of lines and bubble. The lines represent the period of using that term and the bubbles represent the term frequency. The size of the bubble indicates a certain level of frequency for each term, the bigger the bubble the most frequently used that term.

The graph from

Figure 4 was generated by selecting the most frequently used keywords by the authors for their papers, thus it can be observed an evolution of their interest regarding wood as a building material. In the earlier studies wood was analyzed mainly from construction point of view, most frequently used words were ”construction”, ”wood construction” or ”wood”. The next direction of research focused on the study of timber structures and some attention started to the idea of recycling and possibilities of wood to be recycled. Once the idea of environmental protection became more and more present in all the research, regardless of their focus, form 2020 the word “sustainability” became more frequently used. Also, in the last period the focus of the researchers was on deeper understanding of the use of wood as a building material by exploring the possibilities of engineering wood, as cross laminated timber or mass timbe. Lately, more and more studies are approaching the subject of using wood from circular economy point of view, by prolonging the life of the materials and improving the waste management.

3.3. The Thematic Evolution of Using Wood in Construction

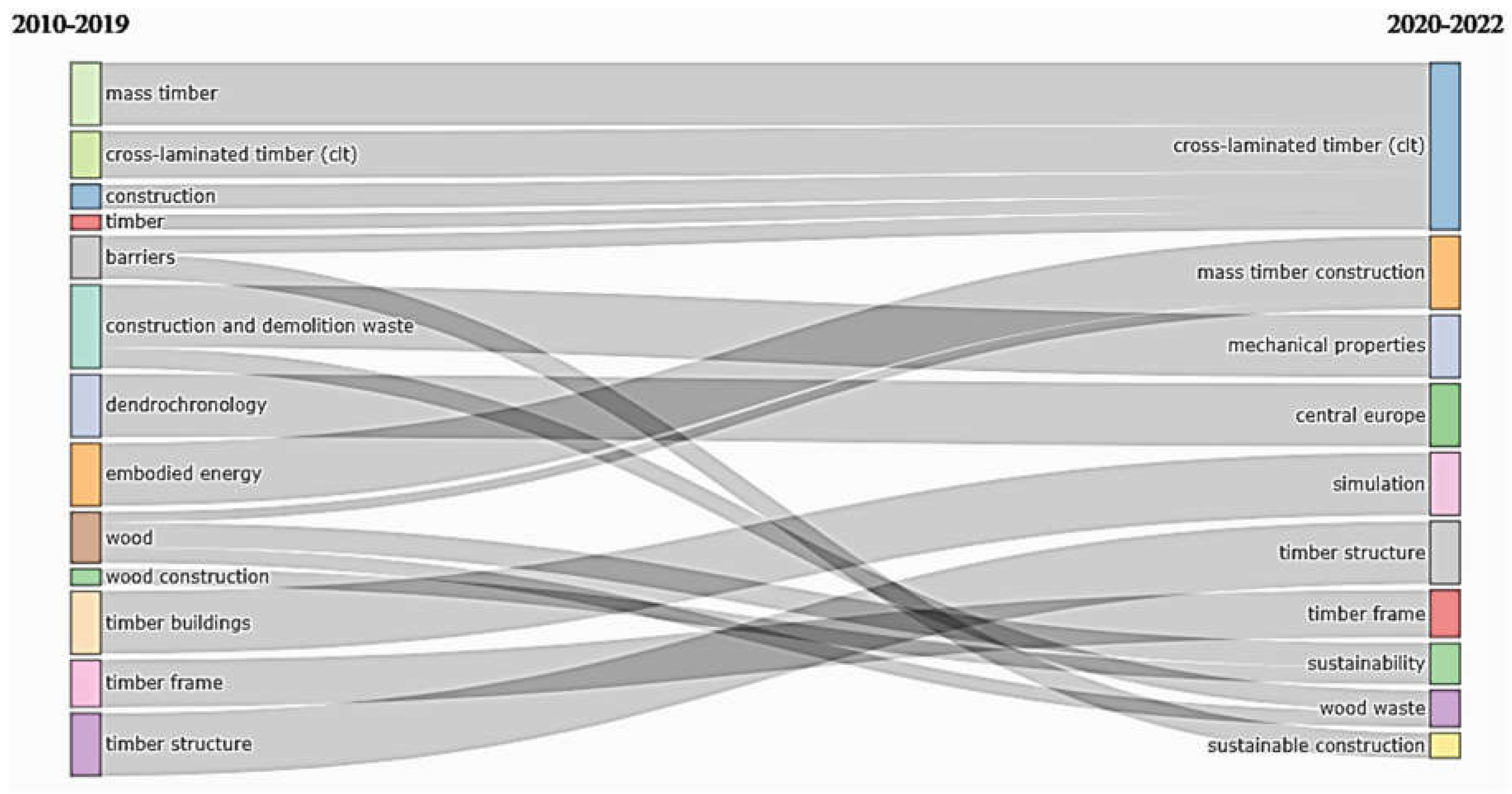

This evolution of the interest for the wood as a building material can be observed in the graph presented in

Figure 5, the thematic evolution of the main used keywords. The graph was generated considering two periods, 2010 to 2019 and 2020 to 2022. The graph was generated using the same Bibliometrix software. The periods considered for the thematic evolution were 2010 – 2019 and 2019 - 2022. The thematic evolution of the keywords was generated with the following parameters: the number of words was set at 250, minimum cluster frequency 5, weight index inclusion: index weighted by word-occurrence; minimum weight index 0.1; number of labels for each cluster 1.

The thematic evolution graph is having the same input data, the authors keywords, as the trend topic graph, but in this graph, it is easy to observe how the keywords transform in time. In the top of the graph, it can be observed that if in the time interval 2010-2019 keywords like “mass timber”, “cross laminated timber”, “construction” or “timber” were used separately, in the papers published in the last period 2020-2022 they were included in the keyword “cross laminated timber”. The study of subjects like “barriers” in using wood split in studying “cross laminated timber” or “sustainable construction”. The subject of “construction and demolition waste” is now treated as the “mechanical proprieties” or “wood waste”. Studies focused on “embodied energy” and a small part of “wood” are now focusing on “mass timber construction”. The studies more focused on the civil engineering part “wood construction”, “timber frame” or “timber structure” are still being studied using the same words while “timber buildings” is found more as “simulation” of the building behavior. The much to general word “wood” is no longer found today being included in words like “mass timber construction”, “sustainability” or “wood waste”.

The position of the words on the graph is given by the number of papers published in each period considered. The majority of papers published in both periods are dealing with the subject of mass timber and cross laminated timber. The first change can be observed on papers studying the barriers of using wood as building material. While half of them continue to approach the subject of using wood to produce cross laminated timber the other half transform and open a new research subject related to sustainable construction. Even if this direction is still a new topic being situated on the bottom of the graph, sustainability can be seen as the major change observed in the graph and it is expected that in the future more studies will focus on looking at wood as sustainable material.

Another interesting aspect observed in the arrangement of the keywords can be observed in case of papers studying the propriety of wood to embody energy which is becoming more and more approached and included in the study of mass timber construction. This can indicate an awareness that wood can be seen not only as a cheaper replacement for other building materials, but it can be a feasible solution to the environmental challenges that the construction industry is facing.

The technological advance in the IT domain can be observed also in the wood research field. More and more papers are using the digital technology to better understand wood constructions, timber buildings are now easy to analyze by simulate their behavior with the help of a computer software. Even if the construction field is one of the most conservative sectors, gradually with the increasing data processing capacity of modern IT tools, the multiple advantages of their use will be felt in the construction industry as well.

4. The In-Depth Analysis of Wood Construction

In the previous sections of the papers the complex nature of wood was highlighted. Wood is a natural material, a live one, having many directions that deserve to continue to be explored and others to be developed in the future. This part of the paper is reserved for an in-depth analysis of the main papers published mainly in the last years. The purpose of this analysis is to better understand the actual research directions discussed in recent papers and to identify potential new ones. To have a general view of the main subjects approached by the researchers with the help of the LucidChart [

13] software a graph was generated (

Figure 6).

As it can be observed from the graph the research directions are covering the entire potential of using wood as a building material starting from using wood as raw material taken directly from the nature and used in construction, the log houses, the processing of round trunk and obtaining timber products, up to the modern timber constructions, the most known one is the Cross Laminated Timber.

The current socio-economic context creates a big demand for green buildings and wood it is the best solutions to this new challenge yet in the market there is a lack of confidence in using wood as a building material [

17]. There still are few studies that can prove the benefits of using wood instead of the other building materials, as it is stated in [

8] since wood absorbs biogenic carbon, it is difficult to determine the environmental benefit until the impact of using other materials in other projects is taken into account. There is therefore a great need to better know the field of using wood as a building material.

The idea that wood constructions are not very resistant in time is not supported by practice, as it can be seen in the study of [

18] where the authors identified roof elements made of wood dated from “can conclude that the four investigated church roofs were built within the period of AD1131–1157, which makes them some of Europe’s oldest surviving wooden structures”.

One of the simplest ways of using wood in construction is to use the trunk of the tree to construct the building. This system is called traditional log-house and it is widely used in the mountain areas where the materials are easily available. The principle of constructing the walls is “superposition of linear elements connected to the orthogonal walls by corner joints” [

17].

Decreasing the wood processing costs by using the whole timber in construction is approached in [

19]. The researchers proposed the realization of log houses with the help of modern digitalization and robotic cutting technology which allow the preparation of the rounded tree trunk easier and even at an industrial level. The technology of using rounded trees in constructions is very laborious and time consuming since each tree is unique and placing one above the other needs a lot of adjustments. The research performed in [

19] shows good results and it reveal the potential of using automatic methods in the conservatory field of construction.

4.1. The Use of Engineering Wood in Construction

It is important to highlight that there is a more and more awareness of the possibility of using wood engineering products and thus to consider other solution, modern timber solutions, to replace the traditional heavy timber constructions. Among the modern types of timber structures, the most known ones are glulam timber, cross laminated timber CLT and various steel - timber composite structures. As highlighted in [

20] “with the improvement of materials, the upgrade of timber processing method and the increasing popularity of engineered wood products, larger and more complex timber structures have been built”. The modern timber structures, the main ones enumerated in [

21] “Cross Laminated Timber (CLT), Nail Laminated Timber (NLT), Dowel Laminated Timber (DLT), Glued Laminated Timber (GLT), Laminated Strand Lumber (LSL), Laminated Veneer Lumber (LVL) and other structural composite lumber (SCL) products” are seen as a efficient structural system with a very good seismic performance.

The use of cross laminated timber has a positive effect in reducing the greenhouse gas emissions and as it is shown in [

22] by replacing concrete floors in steel structural systems with CLT floors the emissions saving potentials “range between 20 and 80 Mt CO

2e with an average around 50 Mt CO

2e in the case of full uptake of the hybrid construction system by 2050. The overall savings represent a 1.5% reduction of the annual greenhouse gas emissions generally attributed to construction”.

The proposed and examined beam models appear to meet the market's demands and needs. All beam types exhibit high mechanical properties, far exceeding the binding requirements for systems type GL24c, regardless of their design (the arrangement of layers and loads). The beams made from visually graded side boards have the highest strength, elastic energy, and elastic work during the bending test. The mechanical characteristics of the fabricated beams, such as bending strength, elastic energy, modulus of elasticity, and resilience, were tested. Results have demonstrated that the wedge-bonded beams made from lower-grade lumber do not diverge noticeably from the beams made from homogenous lamellas [

23].

Solutions to improve the cross laminated timber products are presented in [

24] where a new panel was proposed, the panel is made of CLT elements which have less expensive type of wood in the interior of the CLT. The CLT panel made with recovery wood had similar results in terms of mechanical proprieties as the full CLT structure.

The CLT products were studied also from the type of the wood used to produce them. In this sense the use of bamboo for the CLT production was experimented in [

25]. The bonding performance of the elements was analyzed by conducting orthogonal experiments to evaluate their shear strength, wood failure and delamination rate considering the adhesive type, its spreading time, the clamping time and the clamping pressure. The results of the test showed that the adhesive type is the most important characteristics in the production of CLT elements while the other factors, the spreading time, the clamping pressure and the clamping time have little influence on the bounding performance.

An improved engineered wood product is the

diagonal laminated timber DLT which was developed as a particularity of the CLT products by changing the arrangements of the lamellas achieving thus better results in the mechanical and multiaxial load transfer. As it is showed in [

26] with the help of DLT new possibilities for massive timber construction can be achieved, opening the new application areas in civil engineering and architecture, such as large-span point-supported floor system having the span bigger than 6 m.

Another direction of research is the use of cross laminated timber CLT and cold formed steel (CFS) as structural components. As shown in [

27] composite CLT-CFS sections used as structural elements have a good structural performance in modular buildings. The steel plates are evaluated in [

28] where glued perforated steel plate had excellent slip stiffness and shearing capacity in the push-out and bending tests performed by the researchers. The steel plates experienced low ductility in the test mainly for the brittle fracture of the adhesive. The steel plates can be replaced by glass fiber reinforced polymer plate, as presented in [

29]. The researchers state that glass fiber reinforced polymer plates have similar or even greater static bearing capacities as the steel plate connections.

Timber-concrete composite slabs are becoming more and more popular because they combine the benefits of both materials and provide a practical answer to the growing need for sustainable construction. The investigations' findings demonstrate that micro-notches have a roughly stiff composite action between wood and concrete and enough shear strength for application in commercial and residential structures [

30]. Making wood-concrete composite more resilient to the environmental conditions and improving their compressive strength is the subject of the research [

31]. In [

32] is presented a novel approach to cambering timber elements to address the difficulties of excessive deflections of timber-concrete composite beams during construction.

For the restoration of wooden slabs inside ancient buildings, a theoretical and practical research of the mechanical behavior of a construction unit made of laminated wood and an ecological mortar has been done. It has been determined that adding the mortar compression layer boosted the slab's strength by an average of about 40% compared to using just the wooden joist alone [

33].

4.2. The Joining Systems of Wood Constructions

A major problem in the use of wood is related to the possibilities of joining the elements. In this sense, researchers from a [

34] have conducted an experiment to test the corner of a log house. They tested two types of joints, the standard saddle notch and the dovetail corner. Their research identified that in case of horizontal load the more efficient type of joint is the standard saddle notch. They proposed that the improvement of the lateral load carrying capacity of the dovetail log walls can be made by adopting reinforcing systems.

The research results presented in [

35] reveal that timber step joint can be a very good solution to connect wood members and by not needing any steel part it is an environmentally friendly solution. This type of joint has an optimal transfer of the compression loads and a very good announcement before the load-bearing capacity is reached.

The experiments presented in [

36] demonstrated the suitability of using high-strength full-thread bolts in the frame connection of the cross member and the strut. The same experiments revealed the reliability and safety of using bolts and pins as fasteners to create a frame connection.

The connection of wood and other building material is studied in [

37] where the behavior of the joint of hardwood timber and masonry investigation can help understand the contribution of flexible diaphragms in traditional structures. The timber joints are tested in [

38] also, particularly the cylindrical mortise-tendon timber T- joints. The results revealed that subjected to bending moment the joints can withstand large deformations without a significant drop in lateral force. “The lateral load-carrying capacity and hysteretic behavior of the joint is greatly influenced by whether the tenon is under combined bending and shear or pure shear. The hindrance of post bending could significantly increase the maximum achieved lateral load” [

38].

In [

39] the researchers proposed a new connection, an apex connection that can permit development of a folding mechanism in a light wood frame system. The possibility of a more mobile structures is investigated in [

40] also, a new mechanism using reversible mass timber connectors was developed such that dismountable light-timber frame construction systems can be build. The dismantled structure can later be reused in this way, the principle of circular economy can be applied in the wood construction field. A cutting-edge, fully prefabricated timber envelope, created to make site assembly quick, easy, and scaffold-free is presented in [

41].

The study from [

42] shows that, for single dowel joints in double cuts, the linker has little influence on the results, implying that improving their joint properties represents a small improvement in the reliability results. Aside from subtle differences, the results show that copula functions are a viable tool for capturing common behavioral nuances between random variables. The advantages of using dowels to create wood products are highlighted in [

43] where the researchers are focusing on wood products that can be obtained without the use of adhesives as the dowel laminated timber and densified wood materials.

The advantages brought by the technology can be seen also in the paper [

44] where the authors justify and illustrate the value of using laser cutting technology in the construction of glulam mortise and tenon joints in timber frames. This study showed a significant potential for the rapid manufacture of high-quality, high-uniformity mortise and tenon joints using computer-aided laser cutting method for a variety of applications in the built environment.

4.3. Structural Behavior of Wood Constructions

The behavior of wood as a structural element in construction is another direction of research that tries to better understand the use of wood as building material. Wood is a natural material and thus it is very hard to have a control on each interior structure of a construction element. Although in most of the cases in calculus wood is treated as a usual building material, like concrete of steel, with homogenous structure, it is worth to mention that the idea of not treating wood as a building material but more as something between a material and a structure has appeared. The authors of [

45] argues that due to the nature of wood it is hard that the proprieties of wood to be obtained by small standard specimen. This idea certainly deserves more attention in future research.

Most of the research interest in the structural analysis of wood elements are focused on the cross laminated timber behavior. In [

3] the potential of using distributed sensors to study the structural performance of glued timber. Their results have shown that epoxy adhesive is the optimal one to be used in bonding wood lamellas. The researchers studied three types of epoxy adhesives and recommend the adhesive 2PE-1 as the easier to work with and the cyanoacrylate adhesive (CY -1) not to be compatible with timber due to the timber’s porosity and the tendency to absorb the adhesive.

Another study performed in [

46] compare the bending and shear characteristics of CLT and GLT beams. Their results showed that the bending and shear proprieties of the CLT beams, under same loading conditions, are lower than the GLT beams, because the orthogonal structure inside the CLT.

Other papers focus their research in studying the seismic performance of timber frame structures. In [

47] a heritage Chinese structure with multiple nonlinear connection was investigated. The seismic performance of glulam timber post and beam structures was the main subject of research in [

48] where the authors emphasized the effect of shear wall.

The good behavior of timber structure in the seismic zones is highlighted also in [

49] where through a series of hybrid simulations of timber frames subjected to ground motion excitation proposed post-tensioned timber frame to be suitable for constructions in low to moderate seismicity. In [

21] a new seismic force resisting system for the floor construction is proposed. The system is called FIRMOC and incorporates Floor-Insolation and Recentering techniques that can be used in MODular mass timber constructions. The structural system provides good behavior in case of seismic loads reducing the seismic-induced force on the modular units by more than 50%.

The improvement of the seismic-resistant behavior of buildings can be observed even when wood, in form of sawdust, is introduced in the concrete mixture. As shown in [

50] buildings constructed with concrete blocks having up to 15% wood additive in the mixture can improve the seismic resistance.

In [

51] large spans and asymmetrical column configurations are supported by an integrative design concept for punctually supported timber slabs that is currently being developed. To create a point-supported slab with multi-directional spans, the designed multistorey timber building system combines the advantages of large timber constructions and hollow box systems.

The investigations from [

52] revealed that, for the non-predrilled and predrilled cases, respectively, the characteristic embedment strength values obtained by substituting the mean density with the characteristic density values in established equations yield values that are on average 14% and 19% higher than the actual characteristic values. with a particular emphasis on going over how to convert mean values into characteristic values

The use of wood products in the building sector can have an important role in conservating the resources because in most cases, light timber structures are used. The possibility of constructing sustainable buildings using less material offer a lot of advantage but raised some challenges especially related to the building acoustic. As highlighted in [

53] building acoustics, especially sound insulation, have a major impact on the usability of the final building. The wood constructions being lightweight structures are more prone to vibrations than reinforced concrete because they have a higher stiffness to weight ratio. According to the findings of this inquiry, it is crucial to thoroughly model the slab joints and the elastic support of the slab [

54].

The study [

55] outlines the best current analysis and design approaches and examines technical difficulties related to estimating the vibration serviceability performances of lightweight timber floors. In [

56] is presented a vibro-acoustic analysis of a wood plastic composite WPC orthotropic panel. The research results presented in [

57] shows that the sound insulation performance of CLT is greatly affected by mass and thus is worth to explore the possibility to produce CLT out of more denser tree species. CLT is also the subject of the research carried out in [

58] where field measurements of impact and airborne sound insulation for a prefabricated system of plate elements were performed.

4.4. The Use of IT Technologies in Wood Constructions

The progress achieved in the IT field cannot be overlooked in the case of wooden constructions thus an important number of recent papers are studying the possibility of including the modern IT technology to improve and open new ways to use wood as building material. The robotic technology based on intelligent construction is approached by [

20] which see it as a solution to limitation of using timber structures due to the processing technology. The researchers identify through a case study related to the effect of milling due to the mechanical characteristics of timber, that by adjusting the fixing device the existing machine errors are significantly reduced. They concluded that the robotic processing system and timber frame structure can improve substantially the modern timber structure constructions.

The robotic technology is approached also in [

59] where the researchers proposed a mobile robotic platform where automated assembly tasks can be performed and an on-site robotic fabricated multidirectional slab system. By using this technology directly on-site large-scale integrated timber structures can be constructed.

The assembly of timber structures with the aid of industrial robots was demonstrated in this research [

60] using the application of RL to robotic construction. The tests show that control policies trained in simulation can successfully transfer to reality and can deal with geometric errors during assembly, as illustrated by ap-joint assembly jobs. suggests using reinforcement The first successful application of this strategy in the context of architectural building is presented, teaching robot movement control in contact-rich and tolerance-prone assembly activities.

The concept of robotic timber construction significantly expands the traditional scope of timber construction and introduces the use of robotic assembly logics to this sector by placing the integration of digital design and automated fabrication at the center of both the final object and the process of its construction. Using robotic fabrication, Robotic Timber Construction (RTC) aims to advance additive digital fabrication methods to industrial full-scale dimensions [

61].

Another concept integrated in wood construction is the BIM-based methodology, proposed in [

53] that will allow automated recognition of complex element junction and automatically map them. The augmented reality (AR) has multiple advantages and by using it in the wood construction process can bring a lot of benefits. The researchers proposed in [

62] the use of AR to assist in timber-drilling tasks. They highlighted that with the help of AR complex drilling angle operations can be performed using directly the computer-process feedback. The authors of [

63] propose a timber damage identification dynamic broad network, namely TimberNet, that can quickly realize damage identification via a one-shot calculation.

In the same direction of implementing the new available technology in the wood construction process the researchers from [

64] focus their attention on historic building elements made of wood that over the years and given the technology that they were constructed have now big variations in the cross dimension. The researchers proposed an automatic modeling of the timber elements based on the LIDAR and drilling resisting data.

4.5. The Environmental Impact of Wood Constructions

Another important direction of research in the wood construction field is related to the ecological aspects of the wood and the possibility of using it in a circular economy context. In the last years a significant number of papers published have tackled the subject of environmental benefits of using wood in construction. The subjects of the studies vary from highlighting the ecological and the less polluting technology of using wood compared to other construction materials to more recent approaches of prolonging the life of wood products by using the wood waste.

From the environmental issues point of view the use of wood in construction was analyzed from the concentration of particle matters (PM) produced in the building process. In paper [

65] the researchers demonstrate that in case of two construction one made of steel, and one made of cross laminate timber better results regarding PM emissions are obtained by using CLT as a building material.

A more elaborated study was performed in [

66] where three buildings were analyzed for life cycle greenhouse gas emissions (LCGHGE) and life cycle primary energy (LCPE). The three buildings are made using conventional reinforced concrete (RC), CLT and hybrid CLT. According to the findings, after a 50-year service life, RC and hybrid CLT buildings create 15.00% and 10.77% less LCGHGE, respectively, than CLT and hybrid CLT buildings. In comparison to RC buildings, embodied GHG emissions in CLT and hybrid CLT buildings were lowered by 46.52% and 37.24%, respectively. This difference at GHG emissions and PE in the product and construction stages is evident. When compared to CLT alternatives, RC buildings emit less PE and GHG during operation. In comparison to the RC building, the thermal mass effect has caused the PE for space heating and cooling in CLT and hybrid CLT structures to increase by 2.25 and 2.12 percent, respectively.

A life cycle analyzed was performed also in [

67] where the findings demonstrate the potential value of parametric LCA as a technique for assessing and reducing the possible impact of moisture damage around window connections. On the embodied emissions of wall constructions, this facilitates. Consideration of alternative design and construction methods for timber wall constructions that can be used in tall buildings is made possible by performing parametric LCA analysis at an early stage of the design process. This helps to reduce the likelihood of moisture damage and the embodied emissions that go along with it.

In order to map the current situation in the timber sector and identify raw material assortments utilized in the production of semi-finished wood products, an material flow analysis (MFA) for the year 2019 was conducted. The results of this study demonstrate the growing possibility of using salvaged timber material more frequently in the future [

68].

Due to the fragmentation of its value chain, the abundance of varied stakeholders, and the complexity of the projects, the construction industry has seen low productivity and significant waste [

69]. If wood is considered as raw source the system of recycling recovered wood is more environmentally friendly than incineration. New recycling methods are necessary to advance wood cascading and create a circular bioeconomy [

70].

Reusing structural timber has several challenges, chief of which is ensuring strength and safety. While considering that wood is carbon neutral, the decrease of the environmental load when reusing structural components made of wood was assessed, and this suggests a significant potential [

8]. When used to create WBC, wood waste may be thought of as a CO

2 sink and using it to manufacture low-carbon and circular materials for the concrete industry is an intriguing concept [

71]. To lessen the damaging effects of the construction industry on the environment, wood-cement composite building materials can be mixed with magnesium oxychloride cement (MOC) instead of regular Portland cement [

72].

In [

73] the development of a brand-new, 100 percent biodegradable material concept employing lignosulfonate, starch, and wood particles. The results of early tests on 3DP Biowall samples demonstrate the competitiveness of the material mix. The study [

74] looks into the usage of waste wood shavings in circular economy-based sustainable particleboard designs. For that, three polymeric matrices and two density ranges are evaluated on two wood species (Eucalyptus and Pinus). The results indicate a viable use for leftover wood shavings in a valuable substance. When compared to the production of hard-density particleboards, medium-density particleboards can reduce environmental consequences by up to 23%. This makes it possible to prefabricate various sandwich panel types as panelized building envelope components to be sent to the job site for rapid construction of a residential home building envelope [

75]. Systems made of panel wood, an example of off-site technology, are a great deal more effective than an example of on-site technology as showed in [

76].

The study of the use of bamboo as construction material and the waste of bobos in the building materials was approached in [

77]. The material properties comparison between bamboo and reference lumber reveals that, when compared to the average value of reference timber, bamboo has a higher bulk density and a lower open porosity. Therefore, the authors think that bamboo particleboard and bamboo mat board, with their benefits of reduced cost and technical need, have the potential to be locally climate-adaptive building materials and are competitive with the comparable timber goods.

5. Discussions

From the previous sections of the paper some very interesting ideas can be extracted and deserve to be discussed in more detail. Even if the advantages of using wood in construction are becoming more and more known, there is still some fear of using it from the part of architects and designers. This fear is mainly due to an ignorance of the complexity of this material and probably because most of the time the discussion related to the use of wood appears as an alternative solution to the use of concrete. In these conditions, the comparison of wooden constructions with concrete or brick constructions inevitably appears.

As is it showed in [

45] the current understanding of the elastic and inelastic proprieties of wood as building material is based on models created for other materials ignoring the nature and cellular composition of wood. I consider the idea express by the researchers as a valid one meaning that simple comparation of wood with concrete or steel is not always accurate. Unfortunately, the literature does not offer many studies in this direction. An explanation for this is that the study of wood as a natural element, as plant, is made by forestry engineers, which do not have as main goal the study of mechanical behavior of wood while the civil engineers are focusing mainly on concrete and steel assimilating wood in the same way of thinking, as a simple material. Understanding wood as a construction material must be done precisely by combining the two ways of thinking, knowing the living nature of wood as well as the mechanical requirements specific to constructions.

Many times, when wood constructions are compared with concrete of steel constructions a certain competition appears each side claiming that it is more suitable to be used. The large amounts of energy needed to produce concrete and steel have led to a continuous attempt to replace these materials with other less energy-intensive ones such as wood. Therefore, wood was somehow perceived as the material that can completely replace concrete, bricks or steel, hence the opposition to this material in one of the most conservatory industries, the construction one. It is worth mentioned that construction is an industry where large sums of money are involved and by replacing the principal building material a lot of these sums will be lost. It is important to understand that this idea of competition between building materials is a wrong one, as well as the idea of totally replacing one building material. I think that for the development of the human society a certain balance must be find. There are multiple situations where concrete must be used, as in case of underground foundations for example, and situation where the use of wood is a better solution, for example building the roof.

Being a natural material, a living material, it is clear that under certain conditions wood can deteriorate much faster than concrete, this being one of the main fears related to the use of wood in construction. Although many historic buildings, all over the world, passed the time test, like [

18] or [

78,

79] there are also lot of early examples of wood buildings having a lot of problems, mainly due to the moisture [

80,

81,

82,

83]. In most of the situation the problems are not directly related to the proprieties of wood but is more the case of a bad design or execution of the works. Here it is the same situation of treating wood as a replacing material for concrete or steel ignoring or not knowing the particularities of using wood, the necessity to use treated wood and so on.

A lot of the main disadvantages of wood as a building material can be eliminated using engineering wood products. The most known engineered wood product is the glued laminated timber which opened the possibility of constructing infinitely shapes and dimensions construction elements. From the various types of glued laminated wood elements, the most popular ones are elements made of cross laminated timber CLT which is becoming more and more considered in construction, especially in today’s socio-economic context, facing an energy crisis and at the same time trying to respond to the environmental issues brought by a consummatory society.

The currently construction technology has a major negative impact on the environment, by using building materials that require large amounts of energy to be produced and by generating a lor of waste on all phases of construction. In order to reduce this negative impact and the need to apply the principles of a circular economy in the field of construction as well, more and more studies are focusing on the use of wood and its advantages as a building material. A major advantage, in this context, of using wood as a building material relay on the nature of this material being a natural and sustainable one and fitting perfectly on the idea of circular economy. Wood as raw material can be transformed in building elements and the waste generated can be reused in the composition of other building materials or can be a source of generating bio energy, prolonging thus the life of the material and easing the pressure on the environment.

The progress made by the human society, especially in the IT field, also extend to the field of construction in general and particularly on wood construction technology. The robotic machines, the use of augmented reality and all the new available technology makes it possible to eliminate even more problems related to the use of wood in construction, especially related to the realization of the joints between construction elements. If the progress recorded in the IT field overlaps with the progress recorded in the domain of engineered wood products, the use of wood in construction will definitely expand.

6. Conclusions

Wood is one of the oldest natural materials used by humans, since the early down of civilization. The interest of using wood, a naturally occurring, renewable, and biodegradable material, in construction is becoming more and more actual. This can be seen in the number of research papers published annually, in the last years the number of papers studying the use of wood in construction, increased significantly.

Although wood is more and more studied, there are still many fears and reservations about its use in construction. Most of the time it is perceived as a low budged alternative for concrete or bricks to construct residential or holiday houses. One reason for this believe is the lack of better understanding the proprieties of wood as a building material. Wood is analyzed on structural models constructed for homogenous materials like concrete, ignoring its cellular and fibrous nature.

The main research directions in using wood as a building material are related to the study of new structures made of engineered wood, the most known ones are the CLT structures, the structural behavior of wood structures, the implementation of modern IT technology in wood construction technology and lately the environmental impact of wood construction.

Wood as a construction material is an extremely complex material and for a better understanding of it, there is a need to have an interdisciplinary approach in which to combine the knowledge of construction with that of forestry, ecology, biology and others.

References

- U. Photo and E. Debebe, “World Population Prospects 2022 Summary of Results,” 2022.

- Climate Change Comittee, “Progress in reducing emissions 2022 Report to Parliament,” Jun. 2022. Accessed: Dec. 10, 2022. [Online]. Available: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Progress-in-reducing-emissions-2022-Report-to-Parliament.pdf.

- J. Goodwin, J. E. Woods, and N. A. Hoult, “Assessing the structural behaviour of glued-laminated timber beams using distributed strain sensing,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 325, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Maier, “Building Materials Made of Wood Waste a Solution to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals,” Materials, vol. 14, no. 24, 2021, [Online]. Available: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000737167600001.

- A. Besserer, S. Troilo, P. Girods, Y. Rogaume, and N. Brosse, “Cascading Recycling of Wood Waste: A Review,” Polymers 2021, Vol. 13, Page 1752, vol. 13, no. 11, p. 1752, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Höglmeier, G. Weber-Blaschke, and K. Richter, “Utilization of recovered wood in cascades versus utilization of primary wood—a comparison with life cycle assessment using system expansion,” The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2014 19:10, vol. 19, no. 10, pp. 1755–1766, Jul. 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Bernstein et al., “Renewables need a grand-challenge strategy,” Nature 2016 538:7623, vol. 538, no. 7623, pp. 30–30, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Niu, K. Rasi, M. Hughes, M. Halme, and G. Fink, “Prolonging life cycles of construction materials and combating climate change by cascading: The case of reusing timber in Finland,” Resour Conserv Recycl, vol. 170, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- European Commission, “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions New EU - Forest Strategy for 2030,” Brussels, 2021. Accessed: Jan. 04, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:0d918e07-e610-11eb-a1a5-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF.

- D. Maier, “The use of wood waste from construction and demolition to produce sustainable bioenergy-a bibliometric review of the literature,” Int J Energy Res, vol. 46, no. 9, pp. 11640–11658, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- European Commission, “Forests,” 2022. https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/forests_en (accessed Jan. 04, 2023).

- European Commission, “The EU Action Plan on Forest Law Enforcement Governance and Trade (FLEGT AP),” 2022. Accessed: Jan. 04, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/34861680-e799-4d7c-bbad-da83c45da458/library/a655a5b4-23fb-482d-af47-606697ab168d/details?download=true.

- Lucid, “LucidChart.” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://lucid.co/.

- D. G. Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzla, J.; Altman, “Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement,” Ann Intern Med, vol. 151, pp. 1–8, 2009.

- M. J. Page et al., “The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews,” BMJ, p. n71, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Aria and C. Cuccurullo, “bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis,” J Informetr, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 959–975, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Caniato, A. Marzi, F. Bettarello, and A. Gasparella, “Designers’ expectations of buildings physics performances related to green timber buildings,” Energy Build, vol. 276, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Seim et al., “Diverse construction types and local timber sources characterize early medieval church roofs in southwestern Sweden,” Dendrochronologia (Verona), vol. 35, pp. 39–50, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Geno, J. Goosse, S. van Nimwegen, and P. Latteur, “Parametric design and robotic fabrication of whole timber reciprocal structures,” Autom Constr, vol. 138, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Qiao, Z. Wang, D. Wang, and L. Zhang, “A new mortise and tenon timber structure and its automatic construction system,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 44, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Chen, M. Popovski, and C. Ni, “A novel floor-isolated re-centering system for prefabricated modular mass timber construction – Concept development and preliminary evaluation,” Eng Struct, vol. 222, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. D’Amico, F. Pomponi, and J. Hart, “Global potential for material substitution in building construction: The case of cross laminated timber,” J Clean Prod, vol. 279, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Dziurka, J. Kawalerczyk, J. Walkiewicz, A. Derkowski, and R. Mirski, “The Possibility to Use Pine Timber Pieces with Small Size in the Production of Glulam Beams,” Materials 2022, Vol. 15, Page 3154, vol. 15, no. 9, p. 3154, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. F. Llana, V. González-Alegre, M. Portela, and G. Íñiguez-González, “Cross Laminated Timber (CLT) manufactured with European oak recovered from demolition: Structural properties and non-destructive evaluation,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 339, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Dong, Z. Wang, G. Chen, Y. Wang, Q. Huang, and M. Gong, “Bonding performance of cross-laminated timber-bamboo composites,” Journal of Building Engineering, p. 105526, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Arnold, P. Dietsch, R. Maderebner, and S. Winter, “Diagonal laminated timber—Experimental, analytical, and numerical studies on the torsional stiffness,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 322, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Navaratnam et al., “Development of cross laminated timber-cold-formed steel composite beam for floor system to sustainable modular building construction,” Structures, vol. 32, pp. 681–690, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Tao, B. Shi, H. Yang, C. Wang, X. Ling, and J. Xu, “Experimental and finite element studies of prefabricated timber-concrete composite structures with glued perforated steel plate connections,” Eng Struct, vol. 268, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Wu, Z. Zhang, L. He, and L. ho Tam, “Experimental study on the static and fatigue performances of GFRP-timber bolted connections,” Compos Struct, vol. 304, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Müller and A. Frangi, “Micro-notches as a novel connection system for timber-concrete composite slabs,” Eng Struct, vol. 245, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Khelifi et al., “Conservation Environments’ Effect on the Compressive Strength Behaviour of Wood–Concrete Composites,” Materials 2022, Vol. 15, Page 3572, vol. 15, no. 10, p. 3572, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Müller, P. Grönquist, A. S. Cao, and A. Frangi, “Self-camber of timber beams by swelling hardwood inlays for timber–concrete composite elements,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 308, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Muñoz-Ruiperez, F. F. Oliván, V. C. Carpintero, I. Santamaría-Vicario, and Á. R. Sáiz, “Mechanical Behavior of a Composite Lightweight Slab, Consisting of a Laminated Wooden Joist and Ecological Mortar,” Materials 2020, Vol. 13, Page 2575, vol. 13, no. 11, p. 2575, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Grossi, T. Sartori, I. Giongo, and R. Tomasi, “Analysis of timber log-house construction system via experimental testing and analytical modelling,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 102, pp. 1127–1144, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Braun and B. Kromoser, “The influence of inaccuracies in the production process on the load-bearing behaviour of timber step joints,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 330, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Johanides, D. Mikolasek, A. Lokaj, P. Mynarcik, Z. Marcalikova, and O. Sucharda, “Rotational Stiffness and Carrying Capacity of Timber Frame Corners with Dowel Type Connections,” Materials 2021, Vol. 14, Page 7429, vol. 14, no. 23, p. 7429, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Endo and T. Goda, “Pull-out test and numerical simulation of beam-to-wall connection: Masonry in earthen mortar and hardwood timber,” Eng Struct, vol. 275, p. 115206, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Panoutsopoulou and C. Mouzakis, “Experimental investigation of the behavior of traditional timber mortise-tenon T-joints under monotonic and cyclic loading,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 348, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Islam, Y. H. Chui, and Z. Chen, “Novel Apex Connection for Light Wood Frame Panelized Roof,” Materials, vol. 15, no. 21, p. 7457, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Yan, L. M. Ottenhaus, P. Leardini, and R. Jockwer, “Performance of reversible timber connections in Australian light timber framed panelised construction,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 61, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Gasparri and M. Aitchison, “Unitised timber envelopes. A novel approach to the design of prefabricated mass timber envelopes for multi-storey buildings,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 26, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. D. Aquino, L. G. Rodrigues, J. M. Branco, and W. J. S. Gomes, “Statistical correlation investigation of a single-doweled timber-to-timber joint,” Eng Struct, vol. 269, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Sotayo et al., “Review of state of the art of dowel laminated timber members and densified wood materials as sustainable engineered wood products for construction and building applications,” Developments in the Built Environment, vol. 1, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhan, C. Wang, J. B. H. Yap, and M. S. Loi, “Retrofitting ancient timber glulam mortise & tenon construction joints through computer-aided laser cutting,” Heliyon, vol. 6, no. 4, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Walley and S. J. Rogers, “Is Wood a Material? Taking the Size Effect Seriously,” Materials 2022, Vol. 15, Page 5403, vol. 15, no. 15, p. 5403, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Li, L. Wang, Y. Wei, B. J. Wang, and H. Jin, “Bending and shear performance of cross-laminated timber and glued-laminated timber beams: A comparative investigation,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 45, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Yu, Q. Yang, S. seong Law, and K. Liu, “Seismic performances assessment of heritage timber frame based on energy dissipation,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 56, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Cao, H. Xiong, Y. Liu, D. Yu, and J. Chen, “Seismic performance of glulam timber post and beam structures with and without light frame timber shear wall infill,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 57, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Ogrizovic, G. Abbiati, B. Stojadinović, and A. Frangi, “Hybrid simulation of a post-tensioned timber frame and validation of numerical models for seismic design,” Eng Struct, vol. 265, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Dominguez-Santos, D. Mora-Melia, G. Pincheira-Orellana, P. Ballesteros-Pérez, and C. Retamal-Bravo, “Mechanical Properties and Seismic Performance of Wood-Concrete Composite Blocks for Building Construction,” Materials 2019, Vol. 12, Page 1500, vol. 12, no. 9, p. 1500, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Krtschil et al., “Structural development of a novel punctually supported timber building system for multi-storey construction,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 58, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Iwuoha and W. Seim, “Embedment strength of smooth nails in timber construction – Characteristic and mean values,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 333, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Châteauvieux-Hellwig, J. Abualdenien, and A. Borrmann, “Analysis of early-design timber models for sound insulation,” Advanced Engineering Informatics, vol. 53, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Kawrza, T. Furtmüller, and C. Adam, “Experimental and numerical modal analysis of a cross laminated timber floor system in different construction states,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 344, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Ussher, K. Arjomandi, and I. Smith, “Status of vibration serviceability design methods for lightweight timber floors,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 50, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Santoni, P. Bonfiglio, P. Fausti, C. Marescotti, V. Mazzanti, and F. Pompoli, “Characterization and Vibro-Acoustic Modeling of Wood Composite Panels,” Materials 2020, Vol. 13, Page 1897, vol. 13, no. 8, p. 1897, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Y. Lin, C. T. Yang, and Y. S. Tsay, “A Study on the Sound Insulation Performance of Cross-laminated Timber,” Materials 2021, Vol. 14, Page 4144, vol. 14, no. 15, p. 4144, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Öqvist, F. Ljunggren, and A. Gren, “On the uncertainty of building acoustic measurements - Case study of a cross-laminated timber construction,” Applied Acoustics, vol. 73, no. 9, pp. 904–912, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- H. Chai, H. J. Wagner, Z. Guo, Y. Qi, A. Menges, and P. F. Yuan, “Computational design and on-site mobile robotic construction of an adaptive reinforcement beam network for cross-laminated timber slab panels,” Autom Constr, vol. 142, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Apolinarska et al., “Robotic assembly of timber joints using reinforcement learning,” Autom Constr, vol. 125, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Willmann, M. Knauss, T. Bonwetsch, A. A. Apolinarska, F. Gramazio, and M. Kohler, “Robotic timber construction - Expanding additive fabrication to new dimensions,” Autom Constr, vol. 61, pp. 16–23, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Settimi, J. Gamerro, and Y. Weinand, “Augmented-reality-assisted timber drilling with smart retrofitted tools,” Autom Constr, vol. 139, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, K. V. Yuen, M. Mousavi, and A. H. Gandomi, “Timber damage identification using dynamic broad network and ultrasonic signals,” Eng Struct, vol. 263, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Santos, M. Cabaleiro, H. S. Sousa, and J. M. Branco, “Apparent and resistant section parametric modelling of timber structures in HBIM,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 49, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Ahmed and I. Arocho, “Emission of particulate matters during construction: A comparative study on a Cross Laminated Timber (CLT) and a steel building construction project,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 22, pp. 281–294, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Z. Duan, Q. Huang, Q. Sun, and Q. Zhang, “Comparative life cycle assessment of a reinforced concrete residential building with equivalent cross laminated timber alternatives in China,” Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 62, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Fufa, C. Skaar, K. Gradeci, and N. Labonnote, “Assessment of greenhouse gas emissions of ventilated timber wall constructions based on parametric LCA,” J Clean Prod, vol. 197, pp. 34–46, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Szichta, M. Risse, G. Weber-Blaschke, and K. Richter, “Potentials for wood cascading: A model for the prediction of the recovery of timber in Germany,” Resour Conserv Recycl, vol. 178, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Q. Chen, H. Feng, and B. Garcia de Soto, “Revamping construction supply chain processes with circular economy strategies: A systematic literature review,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 335. Elsevier Ltd, Feb. 10, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Risse, G. Weber-Blaschke, and K. Richter, “Eco-efficiency analysis of recycling recovered solid wood from construction into laminated timber products,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 661, pp. 107–119, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. R. Caldas, A. B. Saraiva, A. F. P. Lucena, M. Y. da Gloria, A. S. Santos, and R. D. T. Filho, “Building materials in a circular economy: The case of wood waste as CO2-sink in bio concrete,” Resour Conserv Recycl, vol. 166, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Maier and D. L. Manea, “Perspective of Using Magnesium Oxychloride Cement (MOC) and Wood as a Composite Building Material: A Bibliometric Literature Review,” Materials 2022, Vol. 15, Page 1772, vol. 15, no. 5, p. 1772, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Kromoser, S. Reichenbach, R. Hellmayr, R. Myna, and R. Wimmer, “Circular economy in wood construction – Additive manufacturing of fully recyclable walls made from renewables: Proof of concept and preliminary data,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 344, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Uemura Silva et al., “Circular vs. linear economy of building materials: A case study for particleboards made of recycled wood and biopolymer vs. conventional particleboards,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 285, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Mohammadabadi, V. Yadama, and J. D. Dolan, “Evaluation of Wood Composite Sandwich Panels as a Promising Renewable Building Material,” Materials 2021, Vol. 14, Page 2083, vol. 14, no. 8, p. 2083, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Švajlenka and M. Kozlovská, “Evaluation of the efficiency and sustainability of timber-based construction,” J Clean Prod, vol. 259, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Huang and Y. Sun, “Hygrothermal performance comparison study on bamboo and timber construction in Asia-Pacific bamboo areas,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 271, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Machado, F. Pereira, and T. Quilhó, “Assessment of old timber members: Importance of wood species identification and direct tensile test information,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 207, pp. 651–660, 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Han, K. Wang, W. Wang, J. Guo, and H. Zhou, “Nanomechanical and Topochemical Changes in Elm Wood from Ancient Timber Constructions in Relation to Natural Aging,” MATERIALS, vol. 12, no. 5, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Autengruber, M. Lukacevic, C. Gröstlinger, J. Eberhardsteiner, and J. Füssl, “Numerical assessment of wood moisture content-based assignments to service classes in EC 5 and a prediction concept for moisture-induced stresses solely using relative humidity data,” Eng Struct, vol. 245, no. August, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Aydın and T. Yılmaz Aydın, “Moisture dependent elastic properties of naturally aged black pine wood,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 262, 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Schmidt and M. Riggio, “Monitoring Moisture Performance of Cross-Laminated Timber Building Elements during Construction,” BUILDINGS, vol. 9, no. 6, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Zhang and R. Richman, “Wood sheathing durability from moisture sorption isotherm variability due to age and temperature,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 273, p. 121672, 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).