1. Introduction

Climate change necessitates urgent action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, which stem from industrial activities, transportation, land-use changes for food production, and the extraction of raw materials [

1,

2]. The construction sector accounts for 37% of global emissions, primarily due to materials such as concrete, steel, and aluminum., glass, and bricks [

3].

This research investigates a practical solution: substituting conventional construction materials with wood-based products in the Mexican context. Wood offers a dual advantage: it extends the carbon storage life of forests by sequestering the carbon absorbed by trees into construction materials [

4]. Replacing high-emission materials reduces the sector’s carbon footprint. Additionally, wood-based materials are often more cost-effective [

5].

Technological advances have enhanced the viability of wood in construction, allowing for 30–50% reductions in carbon emissions through engineered wood products and recovery processes [

6]. Wood processing is up to 40% more energy efficient than concrete or steel [

7]. Integrating digital manufacturing technologies with traditional carpentry techniques further enhances efficiency and opens opportunities for sustainable design and material reuse [

8].

For effective adoption of wood in the construction sector, urban planners, architects, and policymakers must coordinate efforts to integrate wood into urban systems. This adoption includes optimizing supply chains, managing urban forests, mitigating urban heat islands, and ensuring climate adaptation strategies [

9]. Regulatory frameworks are crucial, encompassing economic incentives, carbon pricing, and building code adaptations to encourage the transition to sustainable wood construction. Institutional support in research, training, and public awareness is crucial for creating an enabling environment [

10].

Recent research has emphasized that the adoption of timber in construction across Latin America faces not only technical and regulatory challenges but also cultural and perceptual barriers. A survey of more than 200 professionals in the region revealed that although timber is recognized for its environmental benefits, including carbon storage and reduced construction waste, its use is often constrained by insufficient building codes, lack of technical training, and persistent biases associating concrete and steel with modernity and safety. These findings underscore the importance of addressing both institutional frameworks and professional education to mainstream timber in the building sector [

11].

Investigations suggest that communal viewpoints regarding the robustness and security of wood exert considerable influence on the selection of building materials across diverse locales. Research conducted in Norway and Chile has consistently shown unfavorable impressions regarding the longevity, fire retardancy, and maintenance expenses of wood in urban residential and multi-unit dwellings [

12,

13]. Nevertheless, advantages such as reduced construction expenditures and thermal comfort are also acknowledged [

13].

Cultural distinctions contribute to the receptiveness of wooden structures, with technical and financial advantages proving more convincing than societal considerations [

14]. Similar trends have been observed internationally, where the perceptions of construction professionals significantly influence the choice of materials and the adoption of low-carbon options [

15]. These findings are consistent with previous research, which shows that perceptions of durability, modernity, and economic viability strongly influence the adoption of natural building materials across diverse contexts [

15,

16].

Notwithstanding apprehensions, homeowners typically harbor favorable sentiments toward the safety and efficacy of treated wood, albeit some articulate concerns regarding habitability and health implications [

17]. To foster the advance of timber construction, a cooperative endeavor encompassing public policy, industrial innovations, and lucid scientific dissemination is indispensable to rectify deeply rooted prejudices and misunderstandings [

13]. Despite these global patterns, obstacles persist, notably in areas such as Mexico, where wood has historically been underrepresented in construction practices. Cultural and psychological impediments often outweigh technical difficulties, as exemplified by misperceptions about wood’s resilience and safety. Ameliorating these perceptions requires a thorough understanding of societal attitudes and behaviors regarding wood in construction [

18].

In Mexico, the forestry sector faces challenges that limit its potential. The country has over 138 million hectares of forest, yet annual losses exceed 170,000 hectares due to land-use changes, illegal logging, and forest fires [

19]. Illegal timber production rival’s legal harvests, primarily driven by demand from construction and manufacturing [

20]. High production costs, poor infrastructure, and inefficient management undermine competitiveness, leading to increased timber imports and trade deficits [

21]. Nonetheless, Pinus patula and Pinus pseudostrobus play a significant role in national production [

22].

Mexico's community forestry sector represents a unique opportunity. Unlike other countries, where community forestry focuses on rehabilitating degraded lands, Mexican communities have developed commercial timber enterprises on communal lands over the past three decades. For example, Ixtlán de Juárez in Oaxaca has demonstrated the potential for sustainable forest management through collective ownership, conservation, and integration of forestry enterprises [

23].

Aligning these practices with international trends can enhance resilience and adaptability while reducing risks to forests and local communities [

24,

25]. Comparable discussions have emerged in other regions, such as Ethiopia, where bamboo has been examined as a renewable and commercially viable construction material, illustrating how cultural and market factors shape the uptake of natural resources [

16].

This study aims to evaluate the potential of timber as a sustainable construction material in Mexico by analyzing the perceptions of key stakeholders and identifying the main opportunities and barriers to its adoption within a circular economy and climate change mitigation framework. To achieve this, we combine a targeted literature review with qualitative and quantitative data from semi-structured interviews and a snowball-sampled survey. This approach allows us to integrate insights from previous research with first-hand perceptions of practitioners and experts, providing a comprehensive understanding of the socio-cultural, technical, and regulatory conditions that shape timber adoption in the Mexican construction sector.

This study employs a comprehensive methodological approach to address these issues, utilizing semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders in Mexico's construction, forestry, and wood industries. This approach enables us to examine the socio-cultural, economic, and regulatory factors that influence the adoption of wood-based construction in Mexico.

Preliminary findings suggest that societal acceptance, encompassing the beliefs and biases of developers, architects, and end-users, plays a significant role in the adoption of wood-based practices. Education programs, policy incentives, and collaborative industry efforts are needed to address misconceptions and improve technical understanding. Implementing these measures would facilitate the integration of wood into Mexico's construction industry, aligning it with circular economy principles and advancing environmental sustainability.

2. Materials and Methods

This research employed a descriptive approach, facilitating an in-depth exploration of the data used in the article's discussion. The study was based on semi-structured interviews conducted with companies, professionals, and academics involved in the utilization of wood in the construction sector, as well as a survey using a snowball sampling method targeting architects, engineers, postgraduate students, and researchers.

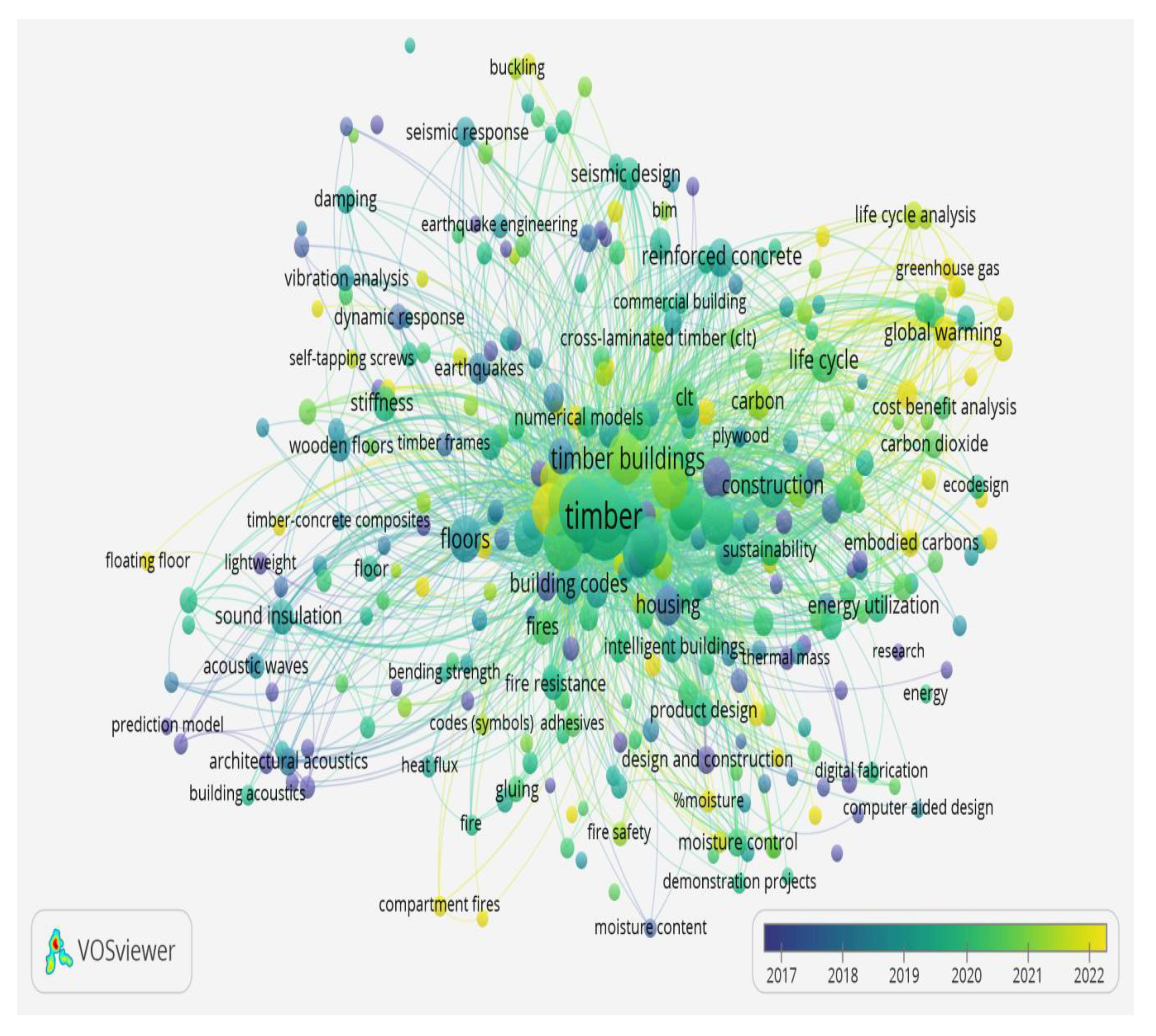

The questionnaire was formulated based on parameters identified in a prior bibliometric analysis, which was conducted using VOSviewer software and limited to a search of Scopus-indexed publications, as shown in Figure 2 of the annex. This analysis yielded insights into: durability, fire safety, energy efficiency, innovation in laminated products, and international regulatory frameworks. Integrating these results into the questionnaire design allowed for the collection of perceptions aligned with the article's prospective approach.

Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews are a flexible and dynamic technique in scientific research, and they were conducted to collect qualitative data efficiently. This method is widely used in qualitative research to gather in-depth information [

26,

27]. Semi-structured interviews allow researchers to explore specific themes while maintaining a conversational style, facilitating the natural expression of participants' perceptions and perspectives [

28]. This approach offers advantages over other interview types, such as adaptability and the ability to refine research questions while maintaining focus [

27].

They are particularly effective in interpretive research, helping researchers understand participants' lived experiences [

29]. Semi-structured interviews are a tool for understanding motivations, attitudes, and the impacts of specific policies or events on individuals' lives [

28].

In August 2023, face-to-face semi-structured interviews were conducted with key stakeholders in the construction sector in Mexico City and the Sierra Norte de Oaxaca as part of a project field trip. Participants included architects, sawmill managers, engineers, and wood specialists, who responded to six questions (

Table 1).

Public Opinion Surveys: A Tool for Studying Public Perception

Recent public opinion surveys have emerged as a valuable tool and methodology for investigating public perception, whose validity is contingent upon technical quality and social legitimacy [

30]. Due to their rapid accessibility and nature, these methods are essential for conjectural analysis [

31], particularly in construction projects.

In this study, we employed a snowball sampling method, a probabilistic technique used in qualitative research. This approach enables its application in virtual environments and social networks for data collection, generating significant samples [

32]. The survey was conducted online through the Encuestafacil platform (

https://www.encuestafacil.com/respweb/cuestionarios.aspx?EID=2908673&MT=X), with data collected from January 19 to March 13, 2024, encompassing four distinct phases:

1. General information: age, gender, place of residence, level of education, and experience in design and construction.

2. General knowledge of the forest-wood relationship and certifications.

3. Materials selected at the time of construction. Wood, brick, and concrete.

4. Final considerations about selecting wood at the time of projecting.

The objective of the survey is to understand how wood is perceived in the construction sector and to recognize whether wood certification and standardization norms are known in Mexico. As well as whether wood is part of the catalog of materials used in the design of a construction project, or if it is only used as ornamental or formwork material.

The results obtained from the post hoc power analysis were performed using GPower software (version 3.1.6). As Faul et al. (2007) describe, “GPower 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences," The software “provides effect size calculators and graphics options” and “offers five different types of statistical power analysis: a priori, compromise, criterion, post-hoc, and sensitivity,”. Furthermore, the authors note, “In this article, we present extensions and improvements of GPower 3 in correlation and regression analyses”. Employing the "post hoc" module with an alpha level of 0.05, a total sample size of N = 50, and the observed effect size (Cohen's d = 2.75), the analysis yielded an achieved power of 0.934, confirming a minimal risk of committing a Type II error and substantiating the robustness of our t-test results [

33].

RAWGraphs software was used to visualize the perception data, representing the results in a star diagram (

Figure 1). The questionnaire responses were previously coded into three levels of agreement ("strongly agree," "agree," and "disagree"), which facilitated the construction of the graphical representation and preparation of

Table 2 with consolidated percentages for each category [

34].

3. Results

Perspective of wood use in construction in Mexico: An expert's approach

Semi-structured interviews with experts from various fields regarding the use of wood allowed for the capture of diverse perspectives on sustainability, the substitution of conventional materials in lightweight structures, and its viability as a primary option in construction.

The results are presented in a "star chart" or "wheel diagram" (

Figure 1). This format enables the visualization of complete responses, highlighting the compactness of the processed data. Each line represents a variable, the sidebars indicate the response percentages, and the categories are segmented by color.

The interview results reveal essential advances in research on how timber construction is perceived in Mexico. At the technical and regulatory level, there is a notable concern regarding the need for more regulations and minimum standards for wood use. Participants also highlighted significant challenges in mixed construction, particularly in combining wood with other materials, such as concrete and steel. The lack of technical knowledge and specific training in wood use represents another critical barrier hindering its widespread adoption.

To ensure consistency between the graphical representation (

Figure 1) of the semi-structured interviews and the numerical systematization (

Table 2) of the survey, responses from the semi-structured interviews were coded and aggregated into the survey's perception categories. Responses were then grouped into three levels of agreement: "totally agree," "agree," and "disagree."

Table 2 presents the combined percentages of the first two categories ("totally agree" and "agree"). At the same time,

Figure 1, created using RAWGraphs software, depicts the relative distribution of these responses in a star diagram. Thus, the table provides a precise quantitative view of the consensus reached, while the figure offers a clear visual representation of the dispersion and compactness of perceptions among participants.

According to the survey results from architecture and construction experts, half (50%) of the respondents use wood as a structural support element in concrete or as formwork. However, only 11% use it as a primary structural material. More than half of the respondents also utilize it for interior finishes, while nearly half do not incorporate it into their designs at all.

The main reasons for avoiding wood as a structural element are the perceived lack of strength and concerns about inadequate treatments to protect it from external agents such as fungi, moisture, and fire. However, in the hypothetical case that these negative perceptions were addressed, there is potential for innovation in wood treatment. In the interview with the specialists, an example was given that innovative wood treatments corrected perceptions, with thirty percent of respondents willing to consider wood as a structural or semi-structural element in housing construction.

Table 2 displays the level of agreement, prominent trends, and consensus interpretations, considering various limitation categories identified in

Figure 1. Key findings from the analysis of perceptions regarding limitations of wood use in construction reveal significant patterns across multiple dimensions. Technical limitations, including lack of training, knowledge, and innovation, emerge as the most consistently recognized barriers by respondents, pointing to a significant gap in capacity building within the sector. Concurrently, regulatory and standardization issues are identified as substantial limitations, showing remarkably high consensus, suggesting the need for more robust and uniform regulatory frameworks.

Interestingly, perceptions traditionally associated with wood limitations, such as the notion that it is only helpful for lightweight structures, do not present themselves as significant concerns. While wood is a crucial element in construction, there is notable variability in opinions regarding its limitations. In this regard, some individuals strongly agree with the technical and economic limitations in using wood, while others strongly disagree. This diversity of perspectives underscores that the perception of wood's capabilities and shortcomings is not uniform. However, certain technical and economic aspects have a greater consensus regarding their impact as limiting factors for the use of this material in construction.

Economic factors, particularly investment needs, are perceived as substantial limitations to broader adoption of wood in construction. Perceptions of performance aspects, such as energy efficiency and structural applications, are notably variable, indicating areas with less consensus within the industry. Finally, respondents agreed that integration with other materials presents significant challenges, suggesting the need to develop better hybrid and mixed construction system solutions.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study highlight the growing role of timber as a sustainable building material, aligning with global trends in low-carbon construction. This trend is mirrored in stakeholder perceptions: interviewed experts anticipate an increased use of timber in building, often in hybrid forms combining wood with conventional materials. Such optimism is grounded in timber’s well-documented environmental advantages. Wood products extend the carbon storage of forests by locking sequestered CO₂ into buildings for decades [

4]. Life-cycle assessments also show that engineered timber can reduce embodied emissions by 30–50% compared to concrete or steel [

6].

These benefits are complemented by improvements in energy efficiency during production and use – wood processing consumes significantly less energy than mineral-based materials, and timber buildings offer superior thermal performance and insulation [

5,

13]. Several interviewees also noted design and operational benefits, citing wood’s light weight and potential for prefabrication, which streamlines construction and reduces onsite waste. This potential is consistent with reports of 20–30% waste reduction in wood construction projects [

35].

Despite these advantages, the study also underscores persistent barriers that must be addressed to mainstream timber in construction in Mexico. A significant challenge identified is the gap in building regulations and standards for the use of structural wood. Similar skepticism has been documented internationally; studies in Norway and Chile have found that many urban residents doubt the longevity and fire performance of wood [

12,

13]. Such concerns persist even as modern treatments and design techniques significantly improve timber’s performance. These findings are consistent with previous research, which shows that perceptions of durability, modernity, and economic viability strongly influence the adoption of natural building materials across diverse contexts [

15,

16].

For example, protective coatings and lamination can enhance fire resistance to meet strict safety standards [

36], yet awareness of these innovations remains low. Cultural biases also play a role in material choice. In Mexico, as in many countries, concrete dominates modern urban aesthetics and is often equated with progress, whereas wood is associated with rural or traditional buildings. This cultural predisposition leads some developers and clients to dismiss timber as old-fashioned or unreliable. Indeed, while wood's sustainable and aesthetic virtues are acknowledged, stakeholders tend to be swayed more by practical considerations of cost and performance than by environmental appeal alone [

14].

Notably, prior research suggests that when wood is treated correctly and its benefits are understood, acceptance tends to increase. Homeowners have reported confidence in the safety and quality of treated lumber, despite initial reservations about issues such as pests or mold [

17]. These findings suggest that many perceptions of the barriers to timber adoption are perceptual and informational, rather than strictly technical, and thus can be overcome through targeted interventions.

A multifaceted strategy is needed to translate timber’s potential into practice, combining policy reform, industry development, and education. Regulatory action is a priority: establishing comprehensive building code provisions and performance standards for timber would provide the construction sector with clear guidance and confidence. Lessons from regions with successful timber high-rises demonstrate that robust codes and certification systems are crucial in addressing safety concerns and liability issues. Government leadership can also drive change by enacting economic incentives, such as subsidies, tax credits, or public procurement preferences for low-carbon materials, which can offset the higher upfront costs of engineered wood and stimulate market demand [

9].

Such incentives, alongside carbon pricing mechanisms, would internalize the environmental benefits of timber and improve its competitiveness relative to steel and concrete. In parallel, strengthening the domestic wood supply chain is crucial for long-term viability. Supporting sustainable forestry and local production of construction-grade timber (e.g., via community forestry initiatives or public-private partnerships) can ensure material quality and reduce costs linked to imports. This action aligns with the circular economy framework, encouraging the reuse and recycling of local wood and ensuring that regenerative forestry practices maximize the environmental benefits of timber throughout its life cycle.

Equally important is capacity-building in the construction sector. The revelation of this study's lack of expertise in timber indicates a need for educational and training programs. As our respondents recommended, universities and technical institutes should integrate modern timber engineering and design into curricula. Continuous professional development courses for architects, engineers, and builders on engineering wood products, such as cross-laminated timber (CLT) design, fire-safe detailing, and moisture protection, would help dispel myths by equipping practitioners with the skills to confidently utilize wood.

Public awareness campaigns could further reinforce these efforts by informing clients and communities about timber’s actual performance, showcasing successful projects, and reframing wood as a modern, high-performance material rather than a backward option. By implementing these measures, stakeholders can progressively overcome the psychological and institutional barriers identified, creating an enabling environment for timber-based building solutions.

Looking ahead, the implications of incorporating timber into construction are substantial. In the near term, piloting more demonstration projects (such as medium-rise timber buildings in Mexican cities) would provide local case studies to evaluate real-world performance and costs, proving the concept to skeptics. Rigorous monitoring of these projects, regarding structural integrity, user satisfaction, and carbon outcomes, could generate valuable data to refine standards and best practices. Over the longer term, mainstreaming timber aligns well with Mexico's commitments to sustainable development and climate change mitigation. By substituting carbon-intensive materials, the construction sector can cut emissions and move toward the net-zero targets urged by international bodies (IPCC, 2023). It could also foster timber and wood industries to enhance their technical, economic, and social-related potential through improvements in the high-end market.

Furthermore, integrating timber into urban development supports a circular economy by creating buildings that function as extended carbon sinks and can be disassembled and repurposed at the end of their life, thereby minimizing waste. Future research should build on our perception-based insights to examine how end-users (homeowners and tenants) respond to living in timber buildings, which will be crucial for market acceptance. Investigating differences in perception between urban and rural populations, or among professionals in different regions, could also inform the tailoring of adoption strategies to specific contexts. Additionally, comparative policy studies – learning from countries with advanced timber construction (e.g., Canada, Scandinavia) – would help identify effective regulatory and incentive frameworks that could be adapted to Mexico's context.

In summary, timber in building presents a promising pathway for climate action, but realizing this promise will require critical shifts in policy, industry practices, and societal mindsets. By critically addressing the identified barriers through coordinated efforts, Mexico's construction sector can harness the full potential of timber, achieving substantial emissions reductions, fostering sustainable development linkages between rural and urban areas, and contributing to global climate mitigation in line with the principles of cleaner production and resource circularity. [

4,

6,

12,

13,

17]

Environmental and Technical Advantages

The results of this study highlight that timber construction offers significant environmental and technical benefits compared to conventional materials. Respondents consistently emphasized that timber could reduce embodied carbon by 30–50%, while also lowering construction-site waste by up to 30%. The ability of wood to store 1–1.6 t CO₂ m³ over its service life demonstrates its dual role as both a building material and a temporary carbon sink, thereby extending the mitigation function of forests into the built environment.

Beyond its climate benefits, timber contributes to circular economy strategies by prolonging the life cycle of biomass and substituting materials with higher carbon intensity, such as steel and concrete. Professionals also recognized its favorable performance in terms of thermal insulation, ease of prefabrication, and adaptability for modular design. These characteristics align with international evidence that engineered wood products not only enhance energy efficiency but also reduce construction timelines and improve overall sustainability in housing and public infrastructure.

Cultural, Regulatory, and Technical Barriers

Despite the evident benefits, professionals identified multiple barriers that limit the broader adoption of timber in the Mexican construction sector. Technical concerns remain central, particularly about durability, fire resistance, and long-term maintenance in diverse climatic conditions. The lack of comprehensive building codes and standardized regulations for timber construction was repeatedly mentioned as a source of uncertainty for architects, engineers, and developers. This regulatory vacuum undermines confidence in the material and limits large-scale investment.

Equally significant are cultural perceptions: concrete and steel are still strongly associated with modernity, strength, and safety, whereas timber is often perceived as fragile, temporary, or less reliable. These social constructs represent an entrenched bias that can only be modified through sustained education and communication strategies. In addition, respondents noted that higher upfront costs for engineered timber solutions act as a financial deterrent, especially in a market where cost minimization often outweighs considerations of long-term sustainability.

Methodological Considerations

The methodological design of this study also imposes limitations that must be acknowledged. The snowball sampling strategy restricted the number of participants, but ensured that all respondents had direct, practical experience in the design and construction of timber buildings. This approach prioritized depth over breadth, yielding insights rooted in genuine expertise rather than hypothetical assessments.

Although the representativeness of the sample is limited, the credibility of the responses is enhanced by the fact that the interviewees were professionals who had faced technical and cultural challenges in actual projects. Future research should complement this expert-based perspective with broader surveys including developers, policymakers, and end-users, thereby enabling comparative analyses of how perceptions differ across professional and social groups.

A significant limitation of the study is the relatively small sample size. This limitation was not due to a lack of outreach but rather a methodological decision to prioritize the quality and relevance of the participants' experience over quantity. A "snowball" sampling technique was used to identify professionals with proven expertise using wood in architectural design or construction. This strategy reduced the pool of participants but ensured a high level of practical and specialized knowledge in the responses obtained. Thus, the study's value lies in the depth and accuracy of the perceptions captured, reflecting the real experience of those directly involved in using wood in construction rather than in broad statistical representativeness.

Pathways and Strategies for Mainstreaming Timber

Overcoming the barriers to timber adoption requires a multidimensional strategy that integrates regulatory reform, financial incentives, education, and collaboration. Clear standards on fire resistance, structural integrity, and seismic performance provide the legal certainty needed to encourage adoption. Parallel to this, economic instruments such as subsidies, preferential loans, or tax incentives for timber-based projects could compensate for higher initial costs and stimulate demand. Education and professional training are equally critical: integrating modules on timber engineering into architectural and civil engineering curricula would ensure that future professionals are equipped to design with this material.

Beyond academia, demonstration projects, pilot housing programs, and training workshops can showcase the safety, durability, and modernity of timber, helping to shift cultural perceptions. Communication strategies that emphasize both the traditional uses of wood in Mexican architecture and innovations in engineered timber could further legitimize the material among professionals and the broader society. Finally, collaborative platforms between government agencies, industry associations, and research institutions could foster innovation, align regulatory frameworks with international best practices, and create a more enabling environment for timber construction.

Towards a Research and Policy Agenda

The findings of this study suggest that timber construction has the potential to become a cornerstone of sustainable housing strategies in Mexico, but this will require overcoming persistent cultural, technical, and institutional barriers. To support this transition, future research should broaden its scope to include comparative regional studies, investigating how local forestry traditions and construction practices influence perceptions of timber.

Longitudinal studies would also be valuable to track how attitudes evolve as new policies, building codes, and pilot projects are implemented. In addition, integrating life-cycle cost analyses and quantitative modeling of carbon storage in real projects would provide more substantial evidence for policymakers and developers. Research could serve as the basis for targeted policies and incentives, ensuring that timber becomes not only an environmentally beneficial material but also a socially accepted and economically viable option in the Mexican construction sector.

Finally, greater collaboration across sectors—forestry, construction, academia, and public policies is required to align supply chains, research, and regulatory frameworks. Such collaboration can help ensure that the environmental benefits of sustainable forestry are translated into tangible contributions to climate mitigation through timber-based construction in cities.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the considerable potential of timber construction to reduce carbon emissions, extend the service life of forest products, and contribute to circular economy strategies in Mexico. Experts with first-hand experience in design and construction highlighted the environmental and practical advantages of timber, further solidifying its role as a viable and sustainable building material.

Nevertheless, significant obstacles persist. Technical concerns regarding durability, fire safety, and maintenance, coupled with regulatory gaps, cultural biases, and higher initial costs, continue to hinder the widespread adoption of timber. Addressing these challenges requires coordinated action across policy, industry, and academia. While snowball sampling provided valuable insights based on practical expertise, it sacrificed statistical representativeness. This approach enhances the depth of the findings but also underscores the need for supplementary studies by employing larger and more diverse samples.

Future research should broaden its scope to encompass a broader range of stakeholders across diverse regions of Mexico. This expansion would enable comparative analyses of perceptions among professional groups, policymakers, and end-users. Such investigations yield a more comprehensive understanding of opportunities and constraints, thereby informing the design of targeted policies, financial incentives, and educational initiatives.

Realizing the full potential of timber in construction demands not only technical advancements and regulatory reforms but also a shift in cultural perceptions. Demonstration projects, updated building codes, and enhanced professional training programs can position timber as a modern, safe, and competitive building material. By overcoming these obstacles, Mexico's construction sector can unlock the full potential of wood, contributing to national climate mitigation objectives and accelerating the transition toward a circular and sustainable urban environment.

Author Contributions

S. Marcelo Olivera-Villarroel: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Lucero García-Franco: Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Alejandro Rodea-Chavez: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Data curation. Christopher L. Heard: Writing –review & editing, Validation. Daniel Rozas-Vásquez: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Paola Ovando: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by FORSCIRC project: "Sostenibilidad y circularidad: Retos y oportunidades para el sector forestal ante el cambio climático ", funded by the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) (Reference: INCGL20018), Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana - Unidad Cuajimalpa (in Mexico) (Reference: DCCD.CD.027.23), and the FOVI project 230147 from the Chilean National Agency for Research and Development. Authors are solely responsible for any errors or omissions in this work. The authors confirm that they have no financial, personal, or professional conflicts of interest related to this study. We protected the privacy of all participants by ensuring that no personal information was collected or stored at any point during the research. People agreed to take part in the survey after understanding what it involved. By accessing and finishing the online questionnaire, they showed their consent. Using the web application meant they agreed to its terms and privacy policy, and we did not request sensitive information or impose any obligations on the researchers.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available upon request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Full Meaning |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of Open Access Journals |

| TLA |

Three Letter Acronym |

| LD |

Linear Dichroism |

| CO₂ |

Carbon Dioxide |

| CLT |

Cross-Laminated Timber |

| CSIC |

Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas |

| IPP |

Institute for Public Goods and Policies |

| UAM |

Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana |

| UCT |

Universidad Católica de Temuco |

| FORSCIRC |

Sostenibilidad y circularidad: Retos y oportunidades para el sector forestal ante el cambio climático |

| FOVI |

Fondo de Investigación (Chile) |

| CONAFOR |

Comisión Nacional Forestal |

| SEMARNAT |

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales |

| PNUMA / UNEP |

United Nations Environment Program |

| IPCC |

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| LCA |

Life Cycle Assessment |

| NDC |

Nationally Determined Contribution |

| GPower |

General Power Analysis Software |

| RAWGraphs |

RAW Graphs Data Visualization Software |

| CC |

Climate Change |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Advancements in wood testing for structural design, modifications to construction codes, fire resistance, product design, and technologies for lamination and other engineering methods are evident (See Figure 3). These improvements underscore the industry's progress in enhancing the structural and environmental performance of wood-based construction materials [

37]. The research reveals an increasing focus on the relationship between construction and the environment, encompassing topics such as "carbon emission," "embodied carbon," "energy efficiency," and "climate change" (See Figure 2). This trend signifies a shift in the perception of wood as a sustainable material for constructing urban and rural dwellings, underscoring its role in addressing climate change mitigation [

38].

Figure A1.

Visualization of timber construction cluster networks.

Figure A1.

Visualization of timber construction cluster networks.

References

- IPCC. Sixth Assessment Report: Climate Change 2023. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Geneva, 2023. https://www.ipcc.ch/languages-2/spanish/.

- Karakosta, C.; Papathanasiou, J. Decarbonizing the Construction Sector: Strategies and Pathways for Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction. Energies 2025, 18, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PNUMA. Informe del Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente: Emisiones del Sector Construcción 2022. Nairobi: PNUMA, 2022. https://www.unep.org/es/resources/informe-sobre-la-brecha-de-emisiones-2022.

- Heräjärvi, H. Wooden buildings as carbon storages – Mitigation or oration? Wood Material Science & Engineering, 2019, 14, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himes, A.; Busby, G. Wood Buildings as a Climate Solution: Carbon Impacts and Future Outlook. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Park, Y. Engineered Timber and Life-Cycle Emission Reductions in Construction. Build. Environ. 2024, 245, 110817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nässén, J. , Hedenus, F., Karlsson, S., & Holmberg, J. Concrete vs. wood in buildings–An energy system approach. Building and environment. [CrossRef]

- Reisach, D., Schütz, S., Willman, J., & Schneider, S. Digital Fabrication for Circular Timber Construction: A Case Study. Journal of Circular Economy, 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Pudzis, E.; Kundziņa, A.; Druķis, P. The Role and Potential of Timber in Construction for Achieving Climate Neutrality Objectives in Latvia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, X.; Luo, C. A Review of Carbon Pricing Mechanisms and Risk Management for Raw Materials in Low-Carbon Energy Systems. Energies 2025, 18, 3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, R.; Guillaumet, A.; do Valle, Â.; Duque, M.d.P.; Gonzalez, G.; Cabrero, J.M.; De León, E.; Castro, F.; Gutierrez, C.; Negrão, J.; et al. Development of Sustainable Timber Construction in Ibero-America: State of the Art in the Region and Identification of Current International Gaps in the Construction Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, A.; Larasatie, P.; Godar Chhetri, S.; Rubino, E.; Boston, K. Perceptions of Multi-Story Wood Buildings: A Scoping Review. Buildings 2025, 15, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encinas, F.; Truffello, R.; Ubilla, M.; Aguirre-Nuñez, C.; Schueftan, A. Perceptions, Tensions, and Contradictions in Timber Construction: Insights from End-Users in a Chilean Forest City. Buildings 2024, 14, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczyszyn, A.; Grzybek, P.; Tokarska, M. Perception of Wooden Structures: Technical and Social Factors in Adoption. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselin, A. , Blanchet, P. , Lehoux, N., and Cimon, Y. Main motivations and barriers for using wood in multi-story and non-residential construction projects, BioResources, 2017, 12, 546–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.; Ding, G.; Crews, K. Sustainable timber use in residential construction: Perception versus reality. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 2014, 186, 399–407. [Google Scholar]

- Vlosky, R.; Shupe, T. Homeowner Perceptions of Pressure-Treated Wood Safety and Performance. For. Prod. J. 2002, 52, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Solís-Carcaño, R. and Franco-Poot, R. (2014) Construction Workers’ Perceptions of Safety Practices: A Case Study in Mexico. Journal of Building Construction and Planning Research, 2, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- CONAFOR. Anuario Estadístico Forestal de México 2023. Comisión Nacional Forestal, México, 2023. https://www.gob.mx/semarnat/documentos/anuarios-estadisticos-forestales.

- Torres-Rojo, J.M. Illegal Logging and the Productivity Trap of Timber Production in Mexico. Forests 2021, 12, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Lopez, P.S.; Perales Salvador, A.; Trujillo Ubaldo, E. El subsector forestal mexicano y su apertura comercial. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales, México, v. 6, n. 29, p. 08-23, jun. 2015. Disponible en http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2007-11322015000300002&lng=es&nrm=iso.

- Moctezuma López, G., & Flores, A. (2020). Importancia económica del pino (Pinus spp.) como recurso natural en México, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales, 11(60), 161-185. Epub 09 de diciembre de 2020. [CrossRef]

- Santiago-García, W.; Bautista-Pérez, L.; Rodríguez-Ortiz, G.; Quiñonez-Barraza, G.; Ruiz-Aquino, F.; Suárez-Mota, M.E.; Santiago-García, E.; Leyva-Pablo, T.; Cortés-Pérez, M.; González-Guillén, M.d.J. Comparative Analysis of Three Forest Management Plans in Southern Mexico. Forests 2022, 13, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, D. B., Merino-Pérez, L., & Barry, D. Chapter 1: Community Managed in the Strong Sense of the Phrase: The Community Forest Enterprises of Mexico. In The community forests of Mexico: managing for sustainable landscapes, 2005, (pp. 1-26). University of Texas Press. https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.7560/706378-003/html.

- Merino-Perez, L. Conservation and Forest Communities in Mexico: Experiences, Visions, and Rights. In: Porter-Bolland, L., Ruiz-Mallén, I., Camacho-Benavides, C., McCandless, S. (eds) Community Action for Conservation. Springer, New York, NY, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Bravo, L.; Torruco-García, U.; Martínez-Hernández, M.; Varela-Ruiz, M. La entrevista, recurso flexible y dinámico. Investigación en Educación Médica 2013, 2, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruslin, R., Mashuri, S., Rasak, M. S. A., Alhabsyi, F., & Syam, H. Semi-structured Interview: A methodological reflection on the development of a qualitative research instrument in educational studies. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education (IOSR-JRME), 2022, 12, 22-29. [CrossRef]

- Adams, W.C. Conducting Semi-Structured Interviews. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuzhat Naz, Fozia Gulab, and Mahnaz Aslam. “Development of Qualitative Semi-Structured Interview Guide for Case Study Research”. Competitive Social Science Research Journal, vol. 3, no. 2, June 2022, pp. 42-52.

- Mañas-Ramírez, B. “Los Orígenes Estadísticos de las Encuestas de Opinión.” EMPIRIA: Revista de Metodología de Ciencias Sociales (2005): 89-113. [CrossRef]

- Aliaga, F., Baeza, M., Basulto, O., Carmona, G., Carretero, Á., Cegarra, J., de Alba, M., Dittus, R., Durán, J., Jodelet, D., Maffesoli, M., Murcia, N., Murcia, J., Narváez, A., Ramírez, C., Riffo, I., Sancho, R., Silva, A., & Vizeu, B. Investigación sensible. Metodologías para el estudio de imaginarios y representaciones sociales. Ediciones USTA.2022. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, N.; Tamar, A. “Field research in conflict environments: Methodological challenges and snowball sampling.” Journal of Peace Research 48 (2011): 423 - 435. [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. GPower 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauri, M.; Elli, T.; Caviglia, G.; Uboldi, G.; Azzi, M. RAWGraphs: A Visualisation Platform for Making Sense of Data. Proceedings of the 12th Biannual Conference on Italian SIGCHI Chapter, Chapter 2017, 28–35. [CrossRef]

- Suter, F.; Steubing, B.; Hellweg, S. Life cycle impacts and benefits of wood along the value chain: the case of Switzerland. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 2017, vol. 21, no 4, p. 874-886. [CrossRef]

- Henek, V.; Venkrbec, V.; Novotný, M. Fire resistance of large-scale cross-laminated timber panels. En IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. IOP Publishing, 2017. p. 062004. [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, O. Trends in the U.S. Forest products sector, markets, and technologies. In: Dockry, Michael J.; Bengston, David N.; Westphal, Lynne M., comps. Drivers of change in U.S. forests and forestry over the next 20 years. Gen. Tech. Rep. NRS-P-197. Madison, WI: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station: 2020, 26–49. [CrossRef]

- Skullestad, J.; Bohne, R.; Lohne, J. Carbon Emission and Life Cycle Assessment of Wooden Buildings. Energy Procedia 2016, 96, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).