1. Introduction

Man-made climate change endangers humanity’s current standards and habitat locations. According to data from NOAA, as of July 2024, the record for consecutive months setting a monthly global average temperature record was set at 14 months (breaking the previous record set between May 2015 and May 2016) [

2]. Simultaneously, public commentary about exceeding the 1.5C and 2C targets set by the Paris Agreement has shifted from “if” to “when.” A recent meta-analysis of 37 different climate models projected the world will pass 1.5C by 2036 (95th percentile), meaning actions taken within the next decade or two are of the upmost importance [

3]. Moreover, humanity is approaching multiple climate tipping points, which once activated accelerate the rate of climate change and are likely irreversible, likely for millennia. A recent climate tipping point example is the observed slowing of the vital Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) caused by the continued increase in ocean surface temperatures and associated salinity levels [

4]. A significant slowdown of the AMOC is projected to lead to severely negative climate impacts, especially for western Europe.

Given these trends, there is an urgent need to both reduce greenhouse gas emissions and remove previously emitted carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Natural land-based systems already remove approximately 2 Gt CO

2 annually, primarily from land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) activities like afforestation and reforestation. Meanwhile, a mere 0.0013 Gt of CO

2, less than 0.1% of total carbon dioxide removal (CDR), comes from novel, technology-based solutions such as direct air capture [

5]. It is doubtful that technology-based carbon removal solutions can be deployed at the scale needed to avoid fast-approaching tipping points or achieve the

$100/ton cost of removed carbon seen as the maximum of economic value required to accelerate widespread adoption [

6]. Relative to building decarbonization, little attention has been given to reducing the built environment’s embodied carbon footprint. Buildings and construction are responsible for well over one third of total global emissions (37 percent), with over 7 percent coming from both concrete (the most-used material in the building sector) and steel (the second most abundant material in buildings) [

1].

A less frequently discussed issue, but also of high importance, is the emerging “global land squeeze.” As total worldwide population continues to rise, so does the demand for land-based products and uses, namely food, wood products, and urban development. These three land uses will compete with the ability of the remaining native habitats to capture and store carbon and to support biodiversity. The use of wood in construction is often asserted as a near-term climate mitigation strategy, and therefore initiatives and policies to increase the use of wood in construction are accelerating. Despite other possible benefits, increased substitution of wood for concrete, steel and other extractive materials simultaneously increases land-use competition. It is estimated that there will be a 54% increase in total wood production between 2010 and 2050, requiring harvesting of about 600M ha of secondary forests in addition to 200M ha of existing plantations [

7]. Furthermore, the true “carbon cost” of wood usage is often overlooked. There is a common misconception that wood is inherently “carbon neutral,” yet in most scenarios, increasing absolute amounts of wood for construction increases atmospheric carbon for many decades, until the harvested wood regrows and captures the emitted CO

2 [

8,

9,

10]. However, there are instances when the harvest and subsequent use of biobased materials can generate carbon removal benefits within a few decades or sometimes even immediately. In an all-carbon-pools analysis for a range of possible forests and harvest scenarios, the only scenarios that achieved high percentage emissions savings for construction material were those that met three conditions: high utilization rate, use of existing plantations or conversion to plantations, and high plantation growth rates, which only exist in selected species in warmer locations [

7].

Given the need to durably sequester carbon for decades and transition to land-use efficient practices,

Eucalyptus is underutilized as a climate-smart building material. Worldwide,

Eucalyptus is the second most planted species of wood, but it is primarily used for non-durable products such as pulp, paper and energy products [

11]. Because these

Eucalyptus end-use products are typically short-lived, the carbon captured during the fast growth cycle of

Eucalyptus is not durably stored. Because of this, harvesting

Eucalyptus without durable storage results in a net warming atmospheric effect. However,

Eucalyptus also possesses the necessary mechanical properties to be used as the structural frame of buildings where the sequestered carbon can be durably stored for many decades. In

Eucalyptus: An Overlooked Resource to Drive CO2 Removal and Building Decarbonization, we outline how the superior strength, productivity, and growth rate of

Eucalyptus make it an ideal candidate for expanded use in building decarbonization. With high characteristic strength and modulus of elasticity, engineered wood products made from

Eucalyptus are a logical choice to meet the increasing demand for wood-based structural building materials [

11]. As one of the fastest-growing tree species in the world,

Eucalyptus can be harvested in as little as 10-12 years for use in engineered wood products, a staggering improvement over the commonly used softwoods of North America that typically take 40 to 75+ years to reach harvestable maturity. Because of these properties, we hypothesized that

Eucalyptus more closely resembles timber bamboo in its carbon removal and storage capacity than three commonly used structural softwoods (Douglas fir, Loblolley pine and Ponderosa pine).

In 2019, we published

Carbon Farming with Timber Bamboo to analyze how timber bamboo’s fast growth and short annual harvest cycle can speed up carbon sequestration and turn timber bamboo plantations into perpetual carbon farms capable of producing high-grade structural fiber that stores the carbon. The analysis used a multi-species/multi-location growth model that was developed to estimate timber bamboo and wood-based annual carbon flows. Robust sensitivity analysis and time valuation of carbon flows along with the development of a comprehensive metric called the Carbon Benefit Multiple (CBM) were used to compare the carbon sequestration and storage potential of both fiber sources. Two unique features are captured in the CBM. First, all carbon flows are time-value discounted. Second, scenarios of time-value discounting are proposed that represent a range of perceived climate change risk. The results showed that with regular harvests turned into durable products, engineered timber bamboo sequesters between 4.9 and 6 times more time-weighted carbon than typical framing timber can [

12]. Here, we test the hypothesis that fast-growing

Eucalyptus could have a CBM that is similarly superior to the North American softwoods commonly used for framing buildings. We show the potential carbon removal and storage advantage of

Eucalyptus to help advance a decarbonized built environment.

2. Materials and Methods

To compare carbon flows, we leveraged the previously developed [

12], which was built from the US Forestry Services (USFS) model “Methods for Calculating Forest Ecosystem and Harvested Carbon with Standard Estimates for Forest Types of the United States” [

13]. This model allows us to directly compare numerous wood-based carbon flows across multiple species and growing locations. The calculation framework of the USFS model incorporates an all-carbon-pools approach by modeling the disposition of carbon flows across three broad categories: 1) the plantation, where all aspects of the ecosystem including above and below ground biomass, ground litter, and soil organic carbon are tracked; 2) the harvest and harvested wood products (HWP) including manufacturing and service life; and 3) the final disposition of the HWPs at end-of-life [

12].

Commercial softwood forestry is well studied and published literature containing models that project the longitudinal carbon flows from softwood plantations are available [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. However, since

Eucalyptus is predominately managed in short rotation cycles for pulp, paper or energy, the availability of long-rotation data that more closely resembles the harvest management used for structural applications is limited. For long rotation, longitudinal Eucalyptus plantation-level data, we combined four species for Brazilian grown Eucalyptus (

E. grandis, E. saligna,

E. urophylla and a hybrid of

E. grandis x E. camaldulensisle with the single published dataset available for Australian-grown

Eucalyptus [

19,

20]. In total, five distinct

Eucalyptus species-location combinations were analyzed. For the softwoods, three North American coniferous species were analyzed: Douglas fir (the largest growing commercial wood species in North America), Loblolley (the fastest growing and most widely planted commercial species in North America, also known as Southern Yellow Pine), and Ponderosa Pine (a commonly planted and widely used species). Data for the three softwood species was drawn from six North American locations, for a total of seven distinct species-location combinations of wood.

Carbon stock over time for the Brazilian site was calculated by using species-specific aboveground biomass equations on sequential inventories of diameter at breast height (DBH, 1,3m above ground) and total height. The dry mass was converted into carbon by multiplying each aboveground component by it specific carbon content, on average 47%. More details related to the site, measurements and fit of the biomass equations are described in Campoe et al., 2012 and le Maire et al., 2019 [

19,

21].

Brazil has a recognized history of advanced breeding and silvicultural practices relative to Eucalyptus. Given the resulting speed and growth efficiency of Brazilian-grown Eucalyptus, rotation cycles of 10-12 years are common for sawlog feedstock. To bias the analysis against our hypothesis, we applied a single 12-year harvest cycle assumption for all four Brazilian Eucalyptus datasets. We used biomass productivity (measured as the volume of wood produced per unit area per year) as a proxy for harvestable bole size of sawlogs. For the fifth Eucalyptus location, which was Australian, we used a projected 15-year harvest cycle. For the three species of softwoods, we obtained harvest rotations directly from the USFS model, ranging from 25 to 75 years. For comparability, we constrained the projected end-use allocations based on historical data for oriented strand board (OSB).

Two stages of biomass conversion efficiency were projected. First, at the time of harvest the mass of felled trees is converted to roundwood for sawlogs that are taken to the mill while leaving the branches, stems and leaves on the ground to decay, thus emitting considerable carbon in the first several years following harvest. Second, end-use conversion at the time of production of the end-use product (or Harvested Wood Product, HWP), accounts for waste that is generated in the milling and manufacturing stage. To model the carbon flows coming from harvest and HWP production for softwoods, we used the USFS published data. Because published data for production efficiencies of long-rotation Eucalyptus into HWP is not available, we utilized the same conversion efficiencies published by the USFS, taking averages of the harvest conversion efficiency and HWP production efficiency across the seven coniferous species-locations and applying them to the five Eucalyptus flows.

Carbon flows through the product ecosystem as an in-use product before being recycled, discarded to a landfill, or burned (and immediately emitted as CO

2). For consistency, we modeled the same HWP disposition carbon flows for all fiber sources. We used the USFS half-life functions for HWP service life and the end-of-life allocations between emissions and landfill deposition. For the portion in landfills, however, we updated the emission projections based on more recently published research for assumptions related to (1) the portion of HWP that was degradable in landfills, (2) when the degradation initiates and (3) how long the degradation occurs before reaching the non-degradable residual state [

22].

Once we obtained annual carbon flows for all species-location datasets, we time discounted them to value near-term atmospheric carbon removal and durable storage (i.e. building decarbonization) more than longer term carbon removal and storage. Policy based carbon accounting and decision making often fails to consider the time value of atmospheric carbon, though advanced, dynamic climate modeling does realistically incorporate time value. This time value modeling of carbon flows incorporates the reality that GHG emissions reduction and CDR that happen today are far more valuable than emission cuts or carbon capture anticipated in the future. The presence of climate system tipping points justifies incorporation of the time value discounting. In conventional finance, a discount rate is applied to each period of cashflows (or more generally, any forward benefit or cost). The higher the discount rate, the more near-term benefits are valued. Similarly, the higher the discount rate, the less certainty or the greater risk is attached to the future carbon benefits. The sum of the discounted carbon flows is the net present value (NPV) of the future flows. The NPV enables a single point of comparison between the different species-location data pairs for a given set of discount rates.

The choice of discount rate applied to the future carbon flows is a subjective and exogenous input in the analysis. To avoid a model influenced from a single discount rate assumption, we tested a range of discount rates which reflect a range of risk perceptions. And instead of using a single discount rate for the entire period of carbon flows, we applied a step function of increasing discounts over time to reflect both delayed early action and increasing information and awareness over time.

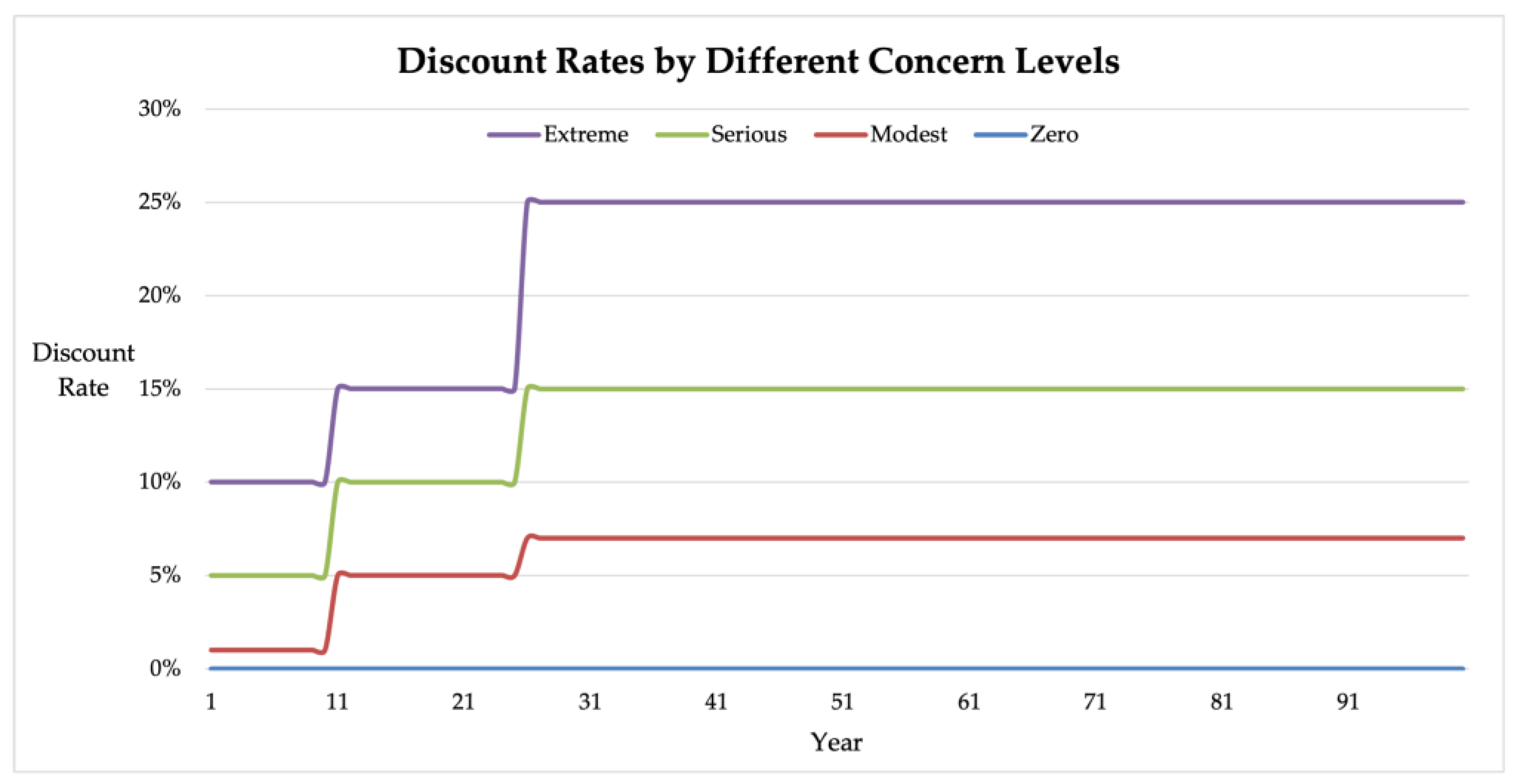

Figure 1 illustrates the three resulting discount rate scenarios applied to the carbon flows for the twelve species-location datasets. The modest risk scenario starts at a 1% discount rate, the serious risk scenario starts at 5%, and the extreme risk scenario starts at 10%. The higher rates imply greater uncertainty about the future, but they also suggest that impacts from distant years are virtually neglected [

23]. The use of higher rates may therefore be reasonable for someone with extreme concern about climate change if they view the situation existentially (i.e. assigns little weight to the future).

To test the hypothesis that

Eucalyptus building materials are preferred carbon storage materials to softwood building materials, we calculate the Carbon Benefit Multiple (CBM), which reflects the ratio of the average PV of the five

Eucalyptus datasets to the average PV for the seven softwoods datasets for various scenarios of time discounting.

If the CBM is greater than 1, Eucalyptus contributes more to building decarbonization than softwoods. If the CBM equals 1, Eucalyptus and softwoods are equivalent. If the CBM is less than 1, softwoods contribute more to building decarbonization that Eucalyptus. The greater the difference from a CMB of 1, the greater the relative impact.

3. Results

3.1. Plantation-Level Cumulative Carbon Flows (Not Discounted)

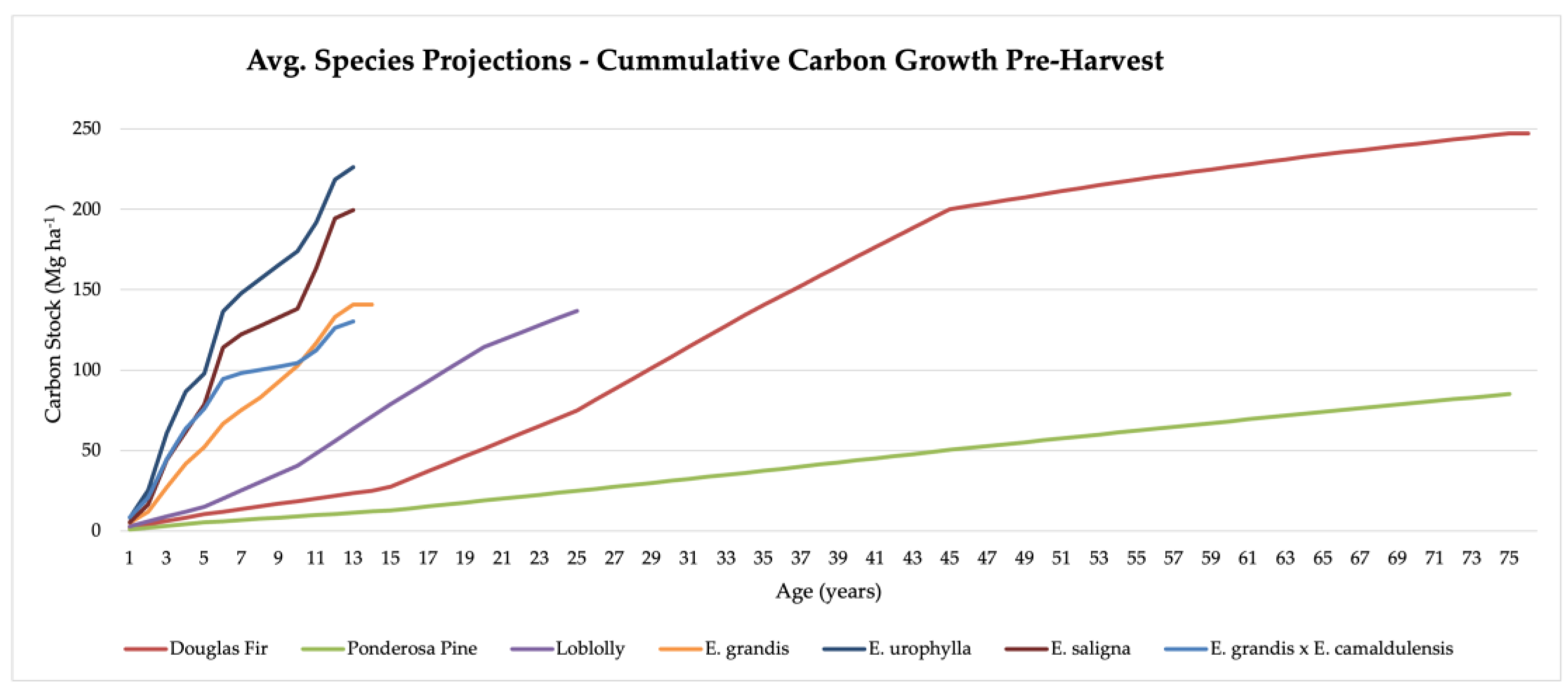

Figure 2 shows the average undiscounted cumulative carbon flows for the four Eucalyptus species and the three softwood species at the plantation level until the year of harvest. The Eucalyptus accumulates sequestered carbon per hectare meaningfully faster than the softwoods. By the ninth year, all four Eucalyptus species have accumulated more than 100 tonnes of C/ha. In contrast, the fastest US grown coniferous species, Loblolly, doesn’t accumulate 100 tonnes C/ha until year 17. The largest growing US softwood, Douglas fir, doesn’t accumulate the 100 tonnes C/ha until year 28, which is three times as long as the slowest of the Eucalyptus species. The third commercial wood species, Ponderosa Pine, does not reach 100 tonnes C/ha by the 100

th year.

3.2. Total (Full Life Cycle) – Annual Carbon Flows (Undiscounted)

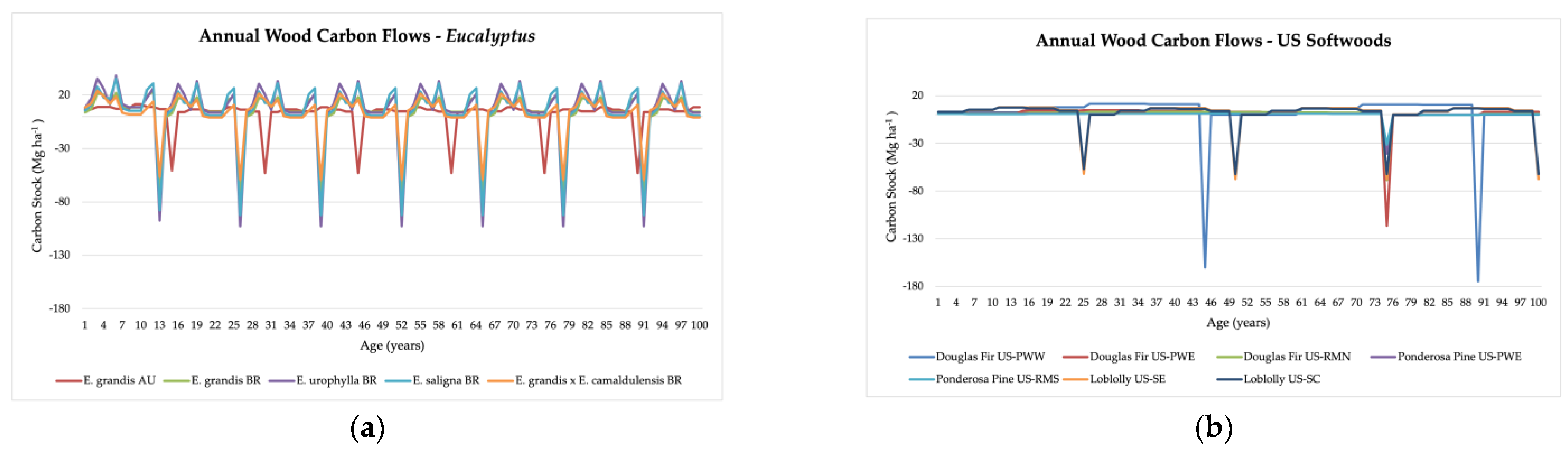

Figure 3a,b present the net annual carbon flows for the Eucalyptus and softwoods, respectively. For both Eucalyptus and the softwoods, when the lines is above zero, annual carbon sequestration is occurring, and when the curve turns negative, the plantation’s harvest waste reemits the sequestered carbon in the year following harvest. Taken together,

Figure 3a and 3b highlight both the large difference in the rotation, or time to harvest, and the larger annual carbon flows for the Eucalyptus species than for the softwood species. Note the Brazilian Eucalyptus growth data shown in

Figure 3a was obtained from a single harvest cycle. The variability in growth year to year is responsible for the spikes in growth prior to harvest. Further research trials would help give more average data and potentially a smoother growth curve.

3.3. Total (Full Life Cycle) – Cumulative Carbon Flows (Undiscounted)

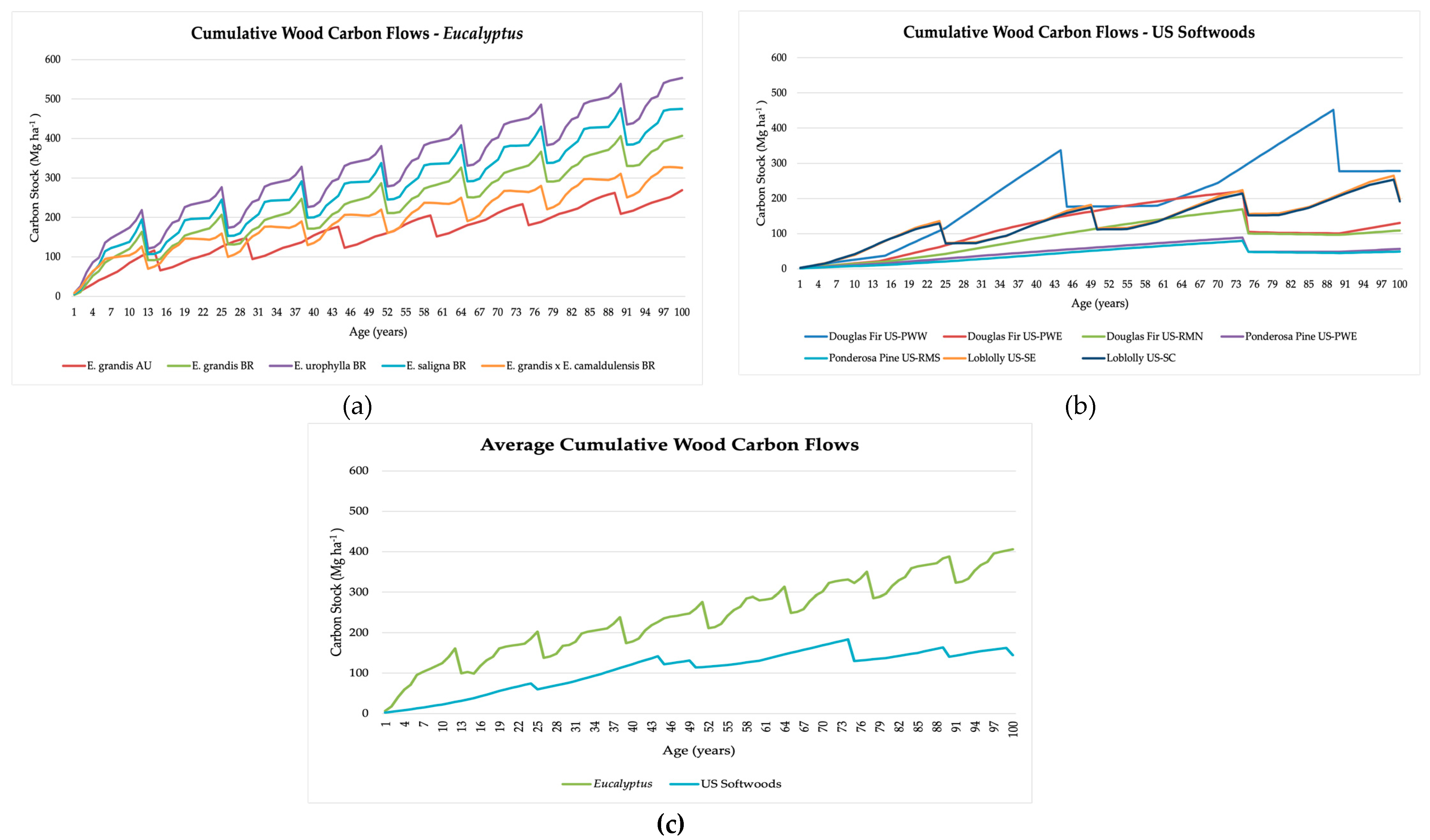

Figure 4a,b present the cumulative carbon flows for the Eucalyptus and softwoods, respectively. For both Eucalyptus and the softwood species, the cumulative carbon captured grows annually until the downward reversal at the time of harvest waste emissions. The key difference between the two species groups is the short rotation and high yield of Eucalyptus species that enables them to more readily overcome the harvest-related emissions and, over time, end up with a much higher total accumulation of sequestered carbon (after including conversion waste, HWP storage and end-of-life treatment). Three of the five Eucalyptus species-location combinations exceed 200 Mt/ha by year 24. In contrast, only the first of the seven softwood combinations reaches 200 Mt/ha temporarily only at year 32. Conversely, at year 84, all five Eucalyptus datasets are above the 200 Mt/ha benchmark and two have reached 400 Mt/ha. The combination of fast growth and high productivity in the cumulative sequestered carbon of all five Eucalyptus datasets at the end of the 100-year period substantially exceeds any of the seven softwood datasets. The lowest performing Eucalyptus species ends at the same level as the highest performing softwood. The average total of accumulation of carbon across the Eucalyptus projections is 406 Mt/ha compared to 138 Mt/ha for the softwoods, almost three times as much.

Figure 4c compares the simple average cumulative carbon flows for the combined Eucalyptus species as compared to the combined softwood species. By the end of the 100-year period, the average carbon stock of the Eucalyptus datasets is 2.8x higher than that of the US softwoods. It is the combination of both speed and productivity that results in these Eucalyptus examples showing the potential to be powerful biogenic carbon capture and storage solutions.

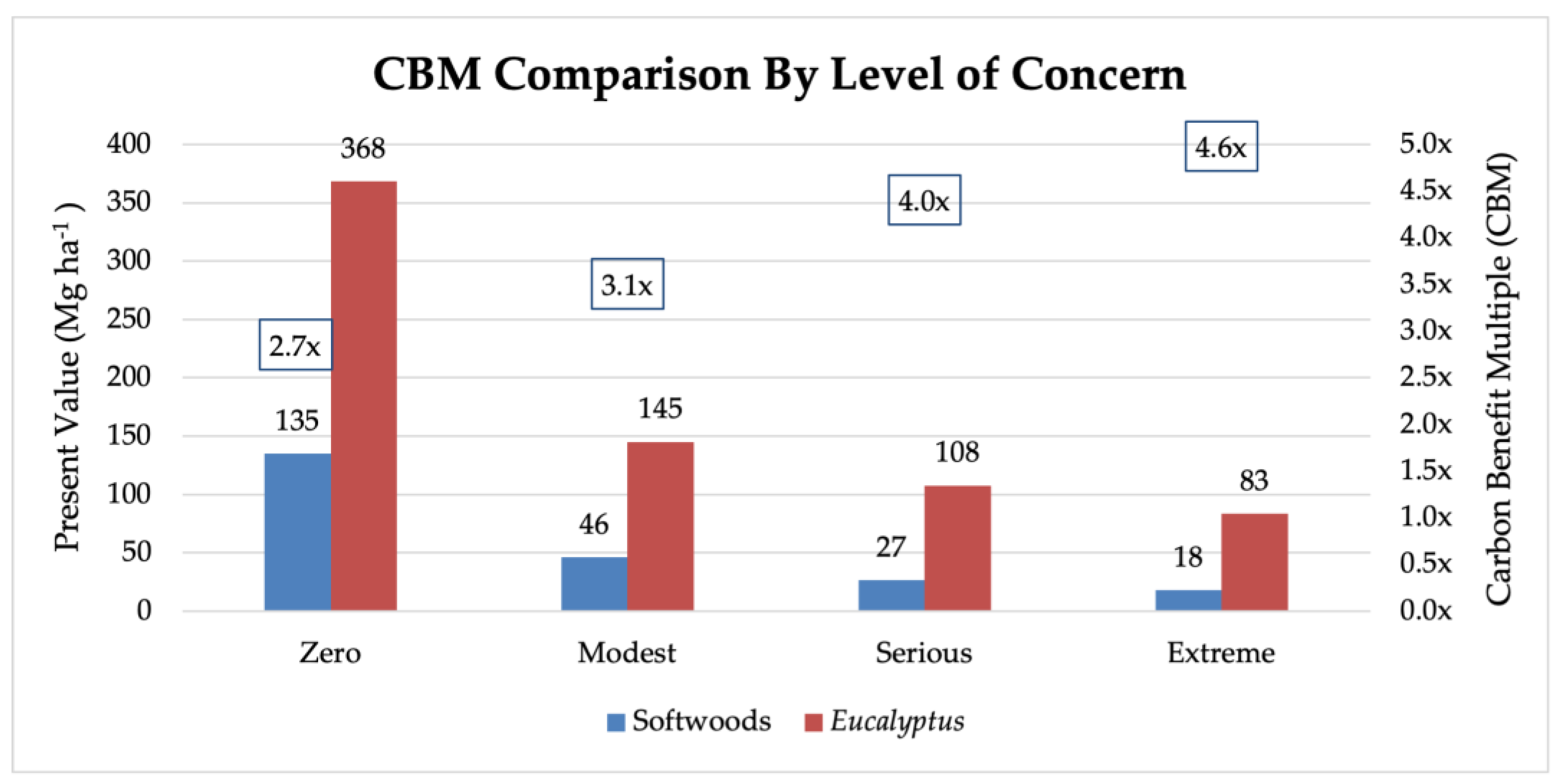

3.4. Carbon Benefit Multiples (Including Temporal Discounting and Scenarios)

To analyze varying degress of concern about climate change, four different temporal discount rate scenarios are constructed that progressively weight higher levels of concern (zero, moderate, serious, and extreme) and thus higher discount rates. The resulting CBM for each scenario is a ratio of present values after discounting the annual carbon flows for the Eucalyptus species compared to the softwood species. This results in a quantification of relative benefit of Eucalyptus compared to softwoods in capturing atmospheric carbon to be stored in durable building structures. The scenario-specific CMBs suggest that Eucalyptus can be 2.7 to 4.6 times more potent in decarbonizing buildings. In the “Modest “ to “Extreme” comparisons, the overall effect of time valuing significantly lowers absolute amounts of carbon sequestration for both Eucalytpus and softwoods. However, across the three “Modest” to “Extreme” levels of concern, the compartive CBM rises in favor of Eucalyptus as the level of concern about climate change (i.e., higher discount rates) increases, highlighting the impact of near-term carbon flows from Eucalytus.

3.5. Total (Full Life Cycle) – Cumulative Carbon Flows with Year 0 Harvest

The CBM framework was originally constructed to compare the potential of bamboo- vs. wood-based afforestation initiatives, and as such, sequestration was modeled over the period leading up to the harvest, following the carbon physically present in the HWP. In dynamic LCAs (DLCA), this so-called “backward-looking” approach is considered appropiate in cases where timber is harvested from forests planted as afforestation efforts [

24,

25]. Conversely, “forward-looking” approaches follow carbon sequestration after a harvest in which trees are planted to replace those that are harvested [

26]. Because of it’s focus on fiber regrowth and the climate benefits of additional sequestration enabled by the harvest of timber with subsequent replanting, we also analyzed carbon flows setting the harvest at Year 0. The results of this second analysis are shown in

Table 1. While this study does not use a DLCA method, the data highlights how results can vary considerably between the two alternative approaches to the timing of sequestration.

The impact of this “forward-looking” approach is that total carbon sequestration across all datasets and scenarios is lowered because of the upfront emissions event at the time of harvest. Instead of starting from zero and increasing, the starting point is a negative value and over time, the follow-on sequestration must compensate. The result is the present value of annual carbon flows from the US softwoods turns progressively negative for each increasing level of concern scenario, whereas the Eucalyptus remains positive across all levels of concern. Given the negative values, the CBM metric becomes less useful and is therefore not calculated in this analysis.

4. Discussion

4.1. Transportation Impact on Carbon Flows

Because fast-growing biogenic fibers are typically found in the warmer tropic and subtropic climates, there will be a greater emissions impact from the logistics associated with transporting them from these regions to decarbonize buildings in other parts of the world. To assess this potential benefit reduction, we performed a simple carbon footprint analysis of the transportation associated with using materials in two different US regions (using U.S. Census data to identify areas with high amounts of new residential construction) that are sourced from within the US and Brazil. Using Simapro software and the ecoinvent database (version 3.9.1), we modeled emissions resulting from three transit configurations: (1) Pacific Northwest softwood traveling to the Midwest or Southern US, (2) Southeastern softwood traveling to the Midwest or Southern US, and (3) Eucalyptus from southern Brazil sent to the US Midwest and South. The total CO

2eq transport results

Table 2 demonstrates that in transit configurations where biogenic structural material travel long road distances within the US, the carbon impact per kg of material is higher than the scenarios where the material travels long distances that are principally oceanic (Brazil to US). This is due to the relatively higher carbon intensity of land transportation compared with oceanic transport. Still, the lowest carbon footprint will result from scenarios where the sourced material is used for buildings in the same region, but practically speaking this is seldom the case.

The above data show that the transport burden of sourcing South American wood for framing in US buildings can be less than the carbon footprint of transporting US grown wood to a different region within the US. Even if Eucalyptus has a higher carbon transport burden, when the Eucalyptus to softwood CBM is greater than 1, some or all of the transport carbon burden can be absorbed while still leaving the CBM greater than 1.

It is worth noting that there is a broader geographic mismatch between sustainable wood supply and building stock demand at play. The majority of sustainable wood supplies today are located in North America and Europe, yet the biggest impact from future urban building development will not occur in these regions. There is, however, significant overlap with where

Eucalyptus plantations are most prevalent and where concentrations and future growth of population are. For example, the two most populous countries (China and India), both with more than 1 billion people and each representing nearly 18 percent of the world’s population, are ranked second and third in terms of total area under

Eucalyptus cultivation, 20 and 17 percent respectively [

11]. Brazil, which has the largest proportion of

Eucalyptus plantation area in the world (20%), is the seventh most populous country worldwide. Looking forward, Pakistan, which has 1% of

Eucalyptus plantation area, is projected to become the fifth most populated nation by 2050 [

27]. This is yet another benefit of fast-growing, high productivity fiber sources like

Eucalyptus; they are more likely to be co-located where urbanization rates, and therefore new construction rates, are high, further increasing their potential to produce net-zero built environments.

4.2. Global Carbon Impact

To illustrate the potential impact Eucalyptus can have when utilized for structural building materials, we examined how much atmospheric carbon can be removed and durably stored when increasing portions of existing Eucalyptus plantations are converted to longer rotation for use in construction. The total plantation area of Eucalyptus is estimated at 22.57 million hectares, making it the most widely planted broad-leaved forest species in the world [

28]. The vast majority of Eucalyptus is managed on short rotation (4-7 years) for the production of pulpwood, charcoal, and firewood. We assessed extending these rotations for use in long-lived, high value building products. Using the USFS model, the average cumulative value of carbon flows (assuming zero discount rate) for the five Eucalyptus datasets is 698 Mt C ha

-1 over a 100-year period. If a mere 2% of existing plantations were converted (451,400 ha), 315 million Mt of carbon could be durably sequestered, translating to 1.16 billion Mt CO

2 eq, or over a gigatonne of CDR. Increasing the conversion rate to 10% increases carbon stored to 1.58 billion Mt and carbon dioxide removed to 5.78 billion Mt. Notably, this analysis doesn’t include any substitution or displacement benefits that could arise if the engineered structural Eucalyptus products replace high embodied carbon alternatives like cement and steel. Doing so would increase the carbon benefit projections substantially.

4.3. Land-Use Efficiency Comparison

While the analysis above demonstrates the building decarbonization benefits of Eucalyptus, data for land use efficiency suggests additional benefits. With significant increases in wood construction, the areas and quantities of additional wood harvested could be large. For example, if 10% of the world’s new urban construction between 2010 and 2050 was wood based, 50 Mha of secondary forest would be required [

7]. This highlights the critical need to consider land-use efficiency as additional criteria for evaluating potential biogenic fiber sources. From the USFS data, the average volume per hectare at the time of harvest across the seven softwood species-location pairings is 227 m3/ha. The highest volume per ha softwood came from Douglas fir in the Pacific Northwest, West (445 m3/ha) while the lowest volume per ha came from ponderosa pine in the Rocky Mountain, South (69 m3/ha). Conversely, the average volume per hectare at the age of 13.4 years across the four Brazilian Eucalyptus species-location pairings is 532 m3/ha, with E. urophylla producing the most (612 m3/ha) and E. grandis x camaldulensis producing the least (427 m3/ha). Assuming the average amount of lumber with a specific gravity of .50 required for constructing a house frame is 17,146 kg is 34.3 m3 per house [

29]. An average Brazilian Eucalyptus plantation could generate 17 houses whereas an average US softwood plantation could generate 6.6 houses. This means the fast-growing Eucalyptus is 134% more land-use efficient than the slow-growing alternative. Given every hectare of land used to supply human consumption comes with a high “carbon opportunity cost,” it is essential that we maximize produce the most with the land we have already converted in order to limit future conversion of additional forests.

4.4. Additional Fast-Growing Fiber Sources

The present analysis demonstrates that five non-traditional Eucalyptus species-location combinations can be more beneficial in capturing and storing carbon than seven US softwoods species-locations combinations. Other non-traditional species-location combinatio Asian grown Acacia [

30] are such candidates to be subsequently explored.

4.5. Limitations and Future Considerations

Despite the significant conclusionsof this study, several limitations are acknowledged. First, the range of the data analyzed was species and location restricted, which may limit the generalizability of the results. The types of fiber source also varied between datasets; specifically, the USFS data contained a myriad of forest types and management intensities whereas the Brazilian Eucalyptus data came from plantations with advanced breeding and silvicultural practices that are typically found in Brazil. This may have skewed the results, but it also supports the case to be made that increased investment in clonal selection and silvicultural practices (as has been done for several decades in Brazil) can produce relatively beneficial results. Second, the reliance on self-reported data from Brazilian plywood manufacturers pertaining to rotation length for structural Eucalyptus products introduces potential biases and inaccuracies that could affect the outcomes. Third, with respect to the carbon flows from tree growth over a 100-year timeframe, we assume no change in the underlying growth rates and carbon sequestration capacity. However, studies have shown that with warming climates come changes in productivity, water availability and soil degradation which are not accounted for in this analysis [

31]. Fourth, the validity of applying USFS assumptions about the harvest and HWP production carbon efficiencies for the non-USFS sourced species has also not been tested. Future research should aim to obtain more species and location-specific harvesting and manufacturing practices to more precisely compare alternatives. Fifth, more robust supply-demand transit analysis could provide deeper insights into the transportation impacts of sourcing fast-growing fibers for use in buildings outside of their local regions.

5. Conclusions

Given the outsized role buildings have in generating greenhouse gas emissions, if the built sector does not achieve significant decarbonization, other CDR efforts will remain futile. The present work utilizes the time discounted rational decision-making framework to test the hypothesis that fast growth and high productivity Brazilian grown Eucalyptus offers superior carbon capture and storage benefits compared to traditionally used softwoods used in North American building, and in fact more closely resembles a similar opportunity with timber bamboo. The detailed analysis of system-wide carbon flows from numerous wood sources found that the earlier and faster biomass accumulation of Brazilian grown Eucalyptus gave it a significant advantage in capturing and storing atmospheric carbon compared to US grown softwoods, even after considering differential carbon flow impacts from transportation. The time-discounted decision model that compared annual carbon flows applied the novel Carbon Benefit Multiple metric which attempts to quantify carbon capture and storing benefits when choosing between species and location alternative structural fibers. The Eucalyptus studied here produced a CBM of 2.7x to 4.6x when compared to the slow-growing North America softwoods, suggesting this category of trees can be prioritized as the preferred structural fiber to help decarbonize buildings. The findings underscore the significant potential of utilizing fast-growing and highly productive structural fibers in the construction sector to achieve substantial carbon removal and storage. The accelerated growth cycles allow for quicker accumulation of sequestered carbon to potentially lessen the risk of climate change tipping points. The high productivity permits a more efficient use of limited arable land to potentially address the emerging global land squeeze. Today, Eucalyptus is predominately used for short-lived or non-durable products like pulp and paper, but the more durable the harvested product is, the greater the CBM of the fiber source can be. This suggests that transitioning even small percentages of existing Eucalyptus plantations to higher value, more durable end-use products like building structures could provide material benefits in climate change mitigation work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.C and H.H.; methodology, K.C. and H.H; validation, K.C., H.H., N.A., O.C.; formal analysis, K.C., N.A., O.C.; investigation, K.C. and O.C.; resources, K.C.; data curation, K.C., N.A., O.C.; writing—original draft preparation, K.C.; writing—review and editing, K.C., H.H., N.A., O.C..; visualization, K.C.; supervision, H.H.; project administration, K.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available in publicly accessible locations, as cited in the References section of this paper. These data sources include previously published and publicly available datasets. No new data were created specifically for this study. All data utilized can be obtained directly from the referenced publications and resources.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author hereby declares a potential conflict of interest with respect to the research presented in this paper. The material discussed and analyzed in this study is used in products that the Authors’ organization sells as part of their business. This relationship may present a financial interest that could influence the interpretation of the research findings or the perceived objectivity of the study. The author affirms that every effort has been made to ensure the integrity and impartiality of the research process. Data were analyzed using standard methodologies, and the results and conclusions drawn are based on the evidence gathered during the research process. All steps were taken to avoid any bias in the research and its reporting. However, the author acknowledges the potential for perceived conflicts of interest and discloses this relationship for full transparency.

References

- United Nations Environment Programme, & Yale Center for Ecosystems + Architecture. (2023). Building Materials and the Climate: Constructing a New Future. https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/43293.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2024, August 12). Earth just had its warmest July on record. https://www.noaa.gov/news/earth-just-had-its-warmest-july-on-record.

- Hausfather, Z. (2024). Analysis: What record global heat means for breaching the 1.5C warming limit. Carbon Brief. https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-what-record-global-heat-means-for-breaching-the-1-5c-warming-limit/.

- Mishonov, A., Seidov, D., Reagan, J. (2024). Revisiting the multidecadal variability of North Atlantic Ocean circulation and climate. Frontiers in Marine Science. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. M., Geden, O., Gidden, M. J., Lamb, W. F., Nemet, G. F., Minx, J. C., Buck, H., Burke, J., Cox, E., Edwards, M. R., Fuss, S., Johnstone, I., Müller-Hansen, F., Pongratz, J., Probst, B. S., Roe, S., Schenuit, F., Schulte, I., Vaughan, N. E. (2024). The State of Carbon Dioxide Removal 2024 - 2nd Edition. [CrossRef]

- Merchant, N., Chay, F., Cullenward, D., & Freeman, J. (2022). Barriers to scaling the long-duration carbon dioxide removal industry. CarbonPlan. https://carbonplan.org/ research/cdr-scale-barriers.

- Searchinger, T., Peng, L., Zionts, J., Waite, R. (2023). The Global Land Squeeze: Managing the Growing Competition for Land. World Resources Institute. [CrossRef]

- Pittau, F., Krause, F., Lumia, G., & Habert, G. (2018). Fast-growing bio-based materials as an opportunity for storing carbon in exterior walls. Building and Environment, 129, 117-129. [CrossRef]

- Pittau, F., Lumia, G., Heeren, N., Iannaccone, G., & Habert, G. (2019). Retrofit as a carbon sink: The carbon storage potentials of the EU housing stock. Journal of Cleaner Production, 214, 365-376. [CrossRef]

- Göswein, V., Arehart, J., Phan-huy, C., Pomponi, F., & Habert, G. (2022). Barriers and opportunities of fast-growing biobased material use in buildings. Buildings and Cities, 3(1), 745–755. [CrossRef]

- Hua, L., Chen, L., Antov, P., Kristak, L., Tahir, P. (2022). Engineering Wood Products from Eucalyptus spp. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Hinkle, H., McGinley, M., Hargett, T., Dascher, S. (2019). Carbon Farming with Timber Bamboo: A Superior Sequestration System Compared to Wood. BamCore. https://www.bamcore.com/_files/ugd/77318d_568cbad9ac2e443e87d69011ce5f48b2.pdf?index=true.

- Smith, J. E., Heath, L., Skog, K., & Birdsey, R. (2006). Methods for calculating forest ecosystem and harvested carbon with standard estimates for forest types of the United States. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station. [CrossRef]

- Puls, S.J., Cook, R.L., Baker, J.S. et al. Modeling wood product carbon flows in southern us pine plantations: implications for carbon storage. Carbon Balance Manage 19, 8 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Peay, W. S., Bullock, B. P., & Montes, C. R. (2022). Growth and yield model comparisons for mid-rotation loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.) plantations in the southeastern US. Forest: International Journal of Forestry Research, 14, 616–633. Fassnacht, F. (Ed.).

- Sohngen, B., & Brown,. (2008). Extending timber rotations: carbon and cost implications. Climate Policy, 8(5), 435–451. [CrossRef]

- Jonker, J. G. G., van der Hilst, F., Markewitz, D., Faaij, A. P. C., & Junginger, H. M. (2018). Carbon balance and economic performance of pine plantations for bioenergy production in the southeastern United States. Biomass and Bioenergy, 117, 44–55. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Benecke, C. A., Martin, T. A., Jokela, E. J., & Torre, R. D. L. (2011). A Flexible Hybrid Model of Life Cycle Carbon Balance for Loblolly Pine (Pinus taeda L.) Management Systems. Forests, 2(3), 749-776. [CrossRef]

- le Maire, G., Guillemot, J., Campoe, O. C., Stape, J.-L., Laclau, J.-P., & Nouvellon, Y. (2019). Light absorption, light use efficiency and productivity of 16 contrasted genotypes of several Eucalyptus species along a 6-year rotation in Brazil. Forest Ecology and Management, 449, 117443. [CrossRef]

- Turner, J., West, G., Dungey, H., Wakelin, S., Maclaren, P., Adams, T., Silcock, P. (2008). Managing New Zealand planted forests for carbon: A review of selected management scenarios and identification of knowledge gaps. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259346441.

- Campoe, O. C., Stape, J. L., Laclau, J.-P., Marsden, C., & Nouvellon, Y. (2012). Stand-level patterns of carbon fluxes and partitioning in a Eucalyptus grandis plantation across a gradient of productivity, in São Paulo State, Brazil. Tree Physiology, 32(6), 696–706. [CrossRef]

- Ximenes, F., Björdal, C., Cowie, A., Barlaz, M. (2015). The decay of wood in landfills in contrasting climates in Australia. Waste Management. [CrossRef]

- Hellweg, S., Hofstetter, T., Hungerbuhler, K. (2003). Discounting and the Environment: Should Current Impacts be Weighted Differently than Impacts Harming Future Generations. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, W., Cooper, S., Allen, S., Roynon, J., & Ibell, T. (2021). Embodied carbon assessment using a dynamic climate model: Case-study comparison of a concrete, steel and timber building structure. Structures, 33, 90-98. [CrossRef]

- Hoxha, E., et al. (2020). Biogenic carbon in buildings: A critical overview of LCA methods. Buildings and Cities, 1(1), 504–524. [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, A., Lesage, P., Margni, M., & Samson, R. (2013). Biogenic carbon and temporary storage addressed with dynamic life cycle assessment. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 17(1), 117–128. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2022). World Population Prospects 2022. https://population.un.org/wpp/.

- Zhang, Y., Wang, X. (2021). Geographical spatial distribution and productivity dynamic change of eucalyptus plantations in China. Scientific Reports, 11, 19764. [CrossRef]

- Oregon Department of Environmental Quality. (2009). A life cycle assessment based approach to prioritizing methods of preventing waste from residential building construction, remodeling, and demolition in the state of Oregon: Phase 1 report, Version 1.2. Quantis, Earth Advantage, and Oregon Home Builders Association.

- Muhammad, A., Rahman, M.R., Hamdan, S., Ervina, J. (2019). Possibility Usage of Acacia Wood Bio-composites in Application and Appliances. In: Rahman, M. (eds) Acacia Wood Bio-composites. Engineering Materials. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Martins, F. B., Benassi, R. B., Torres, R. R., & Brito Neto, F. A. (2022). Impacts of 1.5°C and 2°C global warming on Eucalyptus plantations in South America. Science of the Total Environment, 825, 153820. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).