Introduction

Pelleted feed is extensively utilized in the animal feed industry for its ability to reduce ingredient segregation, minimize feed wastage, and enhance palatability and digestibility. In starter diets for lambs, its use has become increasingly common [

1,

2]. During pelleting, feed ingredients are conditioned under high temperatures for 15 to 20 seconds, which increases starch gelatinization and alters its molecular structure[

3] .This process influences fermentation and digestion in the rumen [

4]. The feed mixture is then pressed through a die to form cylindrical pellets, which affects their hardness and density [

5]. Feed form significantly impacts starch digestion rates in ruminants, with implications for juvenile and adult ruminant health and performance. However, studies on how pelleting affects lamb performance remain limited.

Young lambs’ underdeveloped teeth and digestive systems make pellet hardness a crucial factor in feed intake and digestion. Pellets for young lambs typically have a smaller diameter and are subjected to a higher compression ratio, increasing hardness, which can reduce intake. Starter feeds for lambs often include alfalfa, which improves growth, health, and rumen development, reduces epithelial keratin thickness, and enhances dietary adaptation during weaning [

6].However, alfalfa’s high fiber content increases friction during pelleting, producing harder and denser pellets that may be less suitable for young lambs [

7]. To address these challenges, producing large pellets using low compression ratio ring dies followed by a post-pelleting crumbling process may improve feed intake in young lambs. This method involves pressing cooled pellets through a roller crumbler and grading sieves to create lamb-appropriate small pellets, reducing fine particles. While commonly used in chick feed production[

8], its application to lamb starter feed has not been studied. Recent research highlights the benefits of pelleted feeds on lamb feed intake, growth performance, and rumen fermentation [

9], but variations in pelleting processes remain unexplored.

This study aims to evaluate the effects of removing alfalfa from pelleted starter feeds or using post-pelleting crumbling on feed intake, growth performance, nutrient digestibility, rumen fermentation, and microbiota composition in lambs. We hypothesize that post-pelleting crumbling can reduce pellet hardness and density, thereby increasing feed intake, enhancing growth performance, and improving rumen fermentation in young lambs.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Approval

The animal procedures used in this study were reviewed and approved by the Gansu Agricultural University’s Academic Committee, according to guidelines established by the Biological Studies Animal Care and Use Committee of Gansu Province (Approval No. GSAU-Eth-AST-2024-010).

Determination of Physical and Chemical Properties of Pellet Feed

For each feed group, three samples of approximately 500 g were collected to evaluate hardness, density, and starch gelatinization. Twenty pellets of uniform length and intact appearance were selected using a quartering method. These pellets were compressed along their diameters until fracture using a hardness tester (YHKC-2A, Taizhou Galaxy Instruments Co.). The mean pressure required for breakage was recorded as the hardness value for each group. A 100 g feed sample was placed into a graduated syringe, and the scale was recorded. A vacuum was applied to measure the inter-pellet void volume. The total pellet volume was then calculated, and density was derived using the formula:

ρ=

m/

V, where

ρ is the density (g/cm³),

m is the mass of the sample (g), and

V is the volume (cm³). Starch gelatinization was measured following the method described by Xiong [

10], ensuring consistency with previously established procedures.

Sample Collection and Measurement of Nutrient Digestion

Eighteen lambs (6 from each feed group, with 3 males and 3 females per group) were selected for fecal sample collection. Following weaning at 49 days of age and a 5-day transition period, fecal samples were collected twice daily over four consecutive days using rectal collection. The samples were pooled for each lamb. A portion of the pooled fecal samples was treated with 10% sulfuric acid for nitrogen fixation, followed by crude protein (CP) analysis. The remaining samples were sealed in plastic bags, dried at 65°C, and later used to determine dry matter (DM), neutral detergent fiber (NDF), acid detergent fiber (ADF), and acid-insoluble ash content. Acid-insoluble ash was employed as an internal marker to calculate the apparent digestibility of CP, DM, NDF, ADF, and organic matter (OM). The starter feed and fecal samples were analyzed for: DM: Determined by drying samples at 105°C. CP: Analyzed according to AOAC International (2000) standards [

11]. Acid-insoluble ash: Determined using a previously described method [

12]. NDF and ADF: Analyzed using a previously described method incorporating heat-stable alpha-amylase and sodium sulfate in the NDF procedure [

13]. The apparent digestibility of DM, OM, CP, NDF, and ADF was calculated using the following equation:

Nutrient apparent digestibility (%) = 100%−(acid-insoluble ash content in feces / acid-insoluble ash content in feed × nutrient content in feed / nutrient content in feces) × 100% [

12].

Collection of Rumen Fluid and Measurement of Volatile Fatty Acids (VFAs)

At 49 days of age, 50 mL of rumen fluid was collected from each lamb using an oral rumen tube in the morning while the animals were fasting. The collected rumen fluid was immediately transferred into cryovials and frozen at -20°C for subsequent analysis of fermentation parameters and microbial sequencing.

The concentrations of VFAs in the rumen fluid were determined using gas chromatography [

14]. The rumen fluid samples were pretreated by filtration through a 0.45 μm disposable filter to remove particulates. The clear supernatant was then transferred to vials for gas chromatography (GC) analysis. VFA concentrations were quantified using a Shimadzu gas chromatograph (GC-2010Plus, Japan) with 2-ethylbutyric acid (2-EB) as the internal standard.

Extraction of Microbial DNA from Rumen Fluid and High-Throughput Sequencing

Total DNA was extracted from rumen fluid using the Omega E.Z.N.A. Stool DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT, United States). The quality and concentration of the extracted DNA were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies Inc., Wilmington, DE, United States). DNA was diluted to a concentration of 50 ng/μL for downstream applications.

For microbial community analysis, the V3–V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified using universal primers 341-F (5’-CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG-3’) and 806-R (5’-GGACTACNNGGGTATCTAAT-3’). The PCR conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation at 98°C for 1 minute, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 98°C for 10 seconds, annealing at 50°C for 30 seconds, and elongation at 72°C for 30 seconds, with a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. Barcoded amplicons were pooled in equimolar amounts for Illumina paired-end library preparation. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (San Diego, CA, United States), producing 250 bp paired-end reads.

Paired-end reads were merged using FLASH (v1.2.11) to create raw tags. Tags were quality-filtered using the QIIME toolkit, resulting in high-quality sequences termed “Effective Tags.” These sequences were denoised with the DADA2 or deblur modules in QIIME2 (version 202202), generating Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). Taxonomic assignment was performed using the SILVA database within mothur, with a confidence threshold of 0.80.

Metrics including Chao1, Shannon, Simpson, ACE, and Observed Species indices were calculated to evaluate within-sample species diversity using QIIME2. Differences in microbial communities across samples were analyzed using Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) and cluster analysis, performed in QIIME (version 1.8.0).

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS (version 26.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) within the general linear model (GLM) framework was applied to assess the main effects of starter feed type and sex, as well as their interactions, on growth performance, nutrient digestion, and rumen fermentation indices. Post hoc multiple comparisons were conducted using the least significant difference (LSD) method. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05, while values within the range of 0.05 < P < 0.1 were interpreted as indicating a trend toward significance.

Discussion

The high-temperature conditioning process during feed pelleting is well-recognized for enhancing palatability and digestibility, which is why pelleted feed is a common choice for commercial lamb starter diets. However, the suitability of pelleted feed’s physical characteristics for lambs remains insufficiently explored. Previous research indicates that lambs fed pelleted starters exhibit lower feed intake and average daily gain (ADG) compared to those fed textured starter feeds [

15]. Similarly, studies in post-weaning lambs and calves show reduced ADG and dry matter intake [DMI] with pelleted feeds compared to powdered or coarser feed forms [

16,

17,

18]. These findings suggest that pelleted feed does not universally enhance growth performance in young ruminants.

The reduced intake of pelleted feed by lambs may be associated with its hardness. During the processing of pelleted feed, achieving a specific hardness level is crucial, as insufficient hardness can compromise pellet formation rates and durability [

19]. This is particularly significant for starter feeds containing alfalfa, as the fiber content in alfalfa increases friction during the pelleting process. While no current studies directly examine the effects of pellet hardness on lamb growth performance, higher hardness may negatively impact feed intake. In this study, removing alfalfa from the feed formulation resulted in a reduction in pellet hardness, though the difference was not statistically significant. Additionally, crumbling the pellets after pelleting substantially decreased their hardness and reduced their density, providing further support for the hypothesis.

This study notably found that feeding lambs crumbled pellets significantly increased their feed intake. Consistent with previous research, the feed intake of all lamb groups increased linearly with age, with particularly rapid growth observed after 21 days of age. In this experiment, the increase in feed intake for the crumbled pellet group after 21 days was significantly higher than that of the control group, with intake during the 21–35 day and 35–49 day periods being 2.30 times and 1.74 times greater, respectively. While limited research exists on the effects of starter feed type on lamb intake and growth, numerous studies on calves indicate that starter feed type significantly influences feed intake and growth [

20]. For instance, calves tend to consume more when fed multiple small pellets or powdered feeds compared to standard pellets [

21]. Though the use of crumbled pellets in ruminant diets has not been extensively studied, research in poultry has shown that chicks fed crumbled pellets achieved higher weights between 15 and 42 days of age compared to those fed whole pellets [

22]. Similarly, studies in broilers during the growing phase reported that weight gain and feed-to-meat ratios were significantly improved with pellets and crumbled pellets compared to meal [

23]. In this study, the substantial increase in feed intake for the crumbled pellet group (CA group) led to significantly higher average daily gain (ADG) during the 35—49 day period compared to both the control and NA groups. Crumbled pellets maintain the advantages of pelleted feeds—such as high-temperature conditioning, reduced ingredient separation, and minimized feed waste—while also reducing hardness and particle size. These characteristics likely contributed to the significant increase in feed intake observed in lambs.

In this study, although the hardness of alfalfa-free pellets was lower than that of the control group (with no significant difference), the starch gelatinization degree was significantly higher in the alfalfa-free group. However, the lambs fed alfalfa-free pellets exhibited significantly lower feed intake compared to the control group. This suggests that including alfalfa meal in starter feeds for young lambs benefits feed intake and development, consistent with findings from numerous studies[

24]. For example, research on Tibetan sheep demonstrated that adding alfalfa to the diet significantly increased final body weight (

P < 0.05) [

25]. Previous studies have shown that alfalfa stimulates the proliferation of cellulose-decomposing bacteria in the rumen, promotes the presence of glycolytic bacteria, and increases the production of short-chain fatty acids. These changes alter the rumen fermentation pattern, enhancing the animal’s utilization of fermentation end products and ultimately improving growth performance [

26]. The effectiveness of roughage supplementation in promoting the healthy development of young ruminants’ rumen depends on factors such as roughage type, fiber length, and supplementation method [

27]. Alfalfa, with its high-quality fiber content, effectively stimulates rumen development. Moreover, alfalfa inclusion increases the concentration of β-hydroxybutyrate (BHBA) in the blood, which may reflect accelerated rumen development, as BHBA levels are closely linked to the metabolic development of the rumen wall and fiber digestion rates [

28]. Other research has shown that starter feeds containing straw improve feed intake in calves compared to feeds without straw [

29]. These findings underscore that simply removing alfalfa hay from feed formulations to address challenges such as increased friction during pelleting or reduced starch gelatinization after steam absorption is not a viable solution. Instead, post-pelleting crumbling of the pellets offers a more effective approach to improving the feeding outcomes of pelleted feeds.

This study further evaluated the impact of different starter feed types on the nutrient digestibility of lambs. Digestibility is influenced by various factors, including the physical form and composition of the feed. Research indicates that most starter feeds in lamb feeding practices are typically pelleted [

30]. However, crumbled feeds or feeds with smaller particle sizes have demonstrated better nutrient digestibility compared to larger pellets [

31]. Moreover, incorporating alfalfa into starter feeds has been shown to enhance the digestibility of ADF and NDF [

32]. The NDF and ADF digestibility in the NA group (standard pelleted feed without alfalfa) was significantly higher than in the CON group (standard pelleted feed with alfalfa). This difference may be attributed to the higher degree of starch gelatinization observed in the NA group. Previous research has shown that increasing the conditioning time during pelleting enhances starch gelatinization, subsequently improving the digestibility of dry matter and starch in calves [

19]. Furthermore, the lower feed intake observed in the NA group may have contributed to the increased digestibility, as studies suggest that higher feed intake reduces retention time in the rumen, which can decrease nutrient digestibility. Interestingly, despite significantly higher feed intake in the CA group (crumbled pellets) compared to the CON group, the digestibility of NDF and ADF remained elevated in the CA group. This finding suggests that crumbled pellet feeds are easier for young lambs to digest and absorb. The physical structure of crumbled pellets appears to be more suitable for the underdeveloped digestive systems of young lambs. Additionally, increased feed intake may promote the physical growth and metabolic functions of the rumen, thereby enhancing fiber digestibility. Supporting this notion, related studies have shown that increased intake of solid feeds contributes to the growth in weight and volume of the rumen, enhancing its metabolic capacity[

33].

This experiment further evaluated the effects of different types of starter feeds on the rumen fermentation function of lambs by analyzing volatile fatty acid (VFA) concentrations in rumen fluid. Among the VFAs, the type of starter feed significantly influenced only the propionate concentration, with no significant effects observed on total acid levels, other VFA concentrations, or the acetate-to-propionate ratio. While some studies suggest that concentrates generate higher propionate levels during fermentation [

34], the NA group in this study exhibited lower propionate levels, likely due to reduced feed intake. The concentration of VFAs in rumen fluid reflects the balance between microbial fermentation and VFA absorption in the rumen. Other studies have similarly reported that young lambs supplemented with alfalfa exhibited lower propionate concentrations during the transitional period post-weaning [

24]. The findings of this study indicate that variations in starter feed types and feed intake have minimal impact on the overall rumen fermentation pattern. Consistent with these results, other research emphasizes that the composition of the diet is the primary determinant of rumen fermentation type, whereas the physical form of the feed exerts minimal influence on fermentation parameters in sheep [

35].

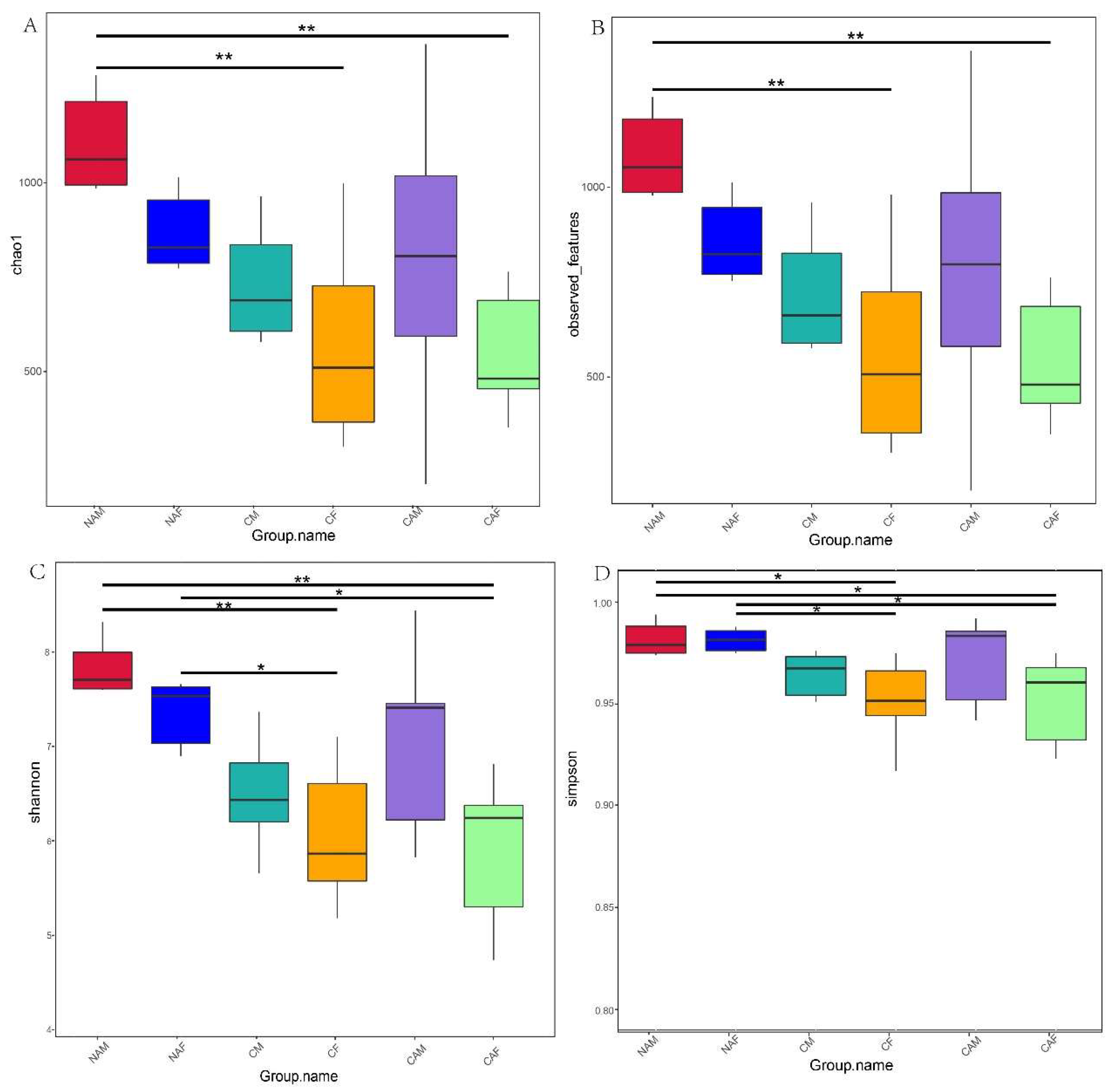

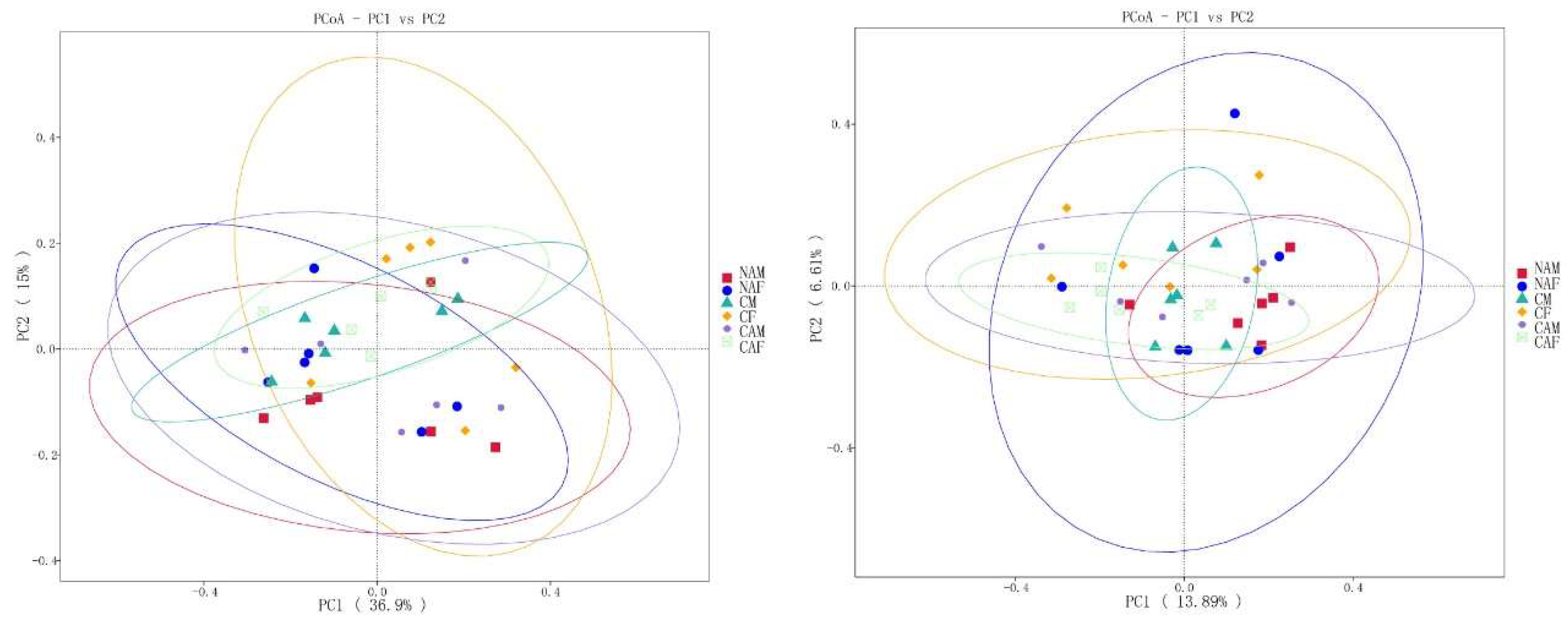

Numerous studies have demonstrated that the physical form of feed influences the rumen microbiota in lambs. For example, Liu et al. reported that pelleted feed, compared to mash, affects phenotypic traits such as meat quality by modulating the rumen microbiota [

36]. In light of this, we further investigated the effects of post-pelleting crumbling on the rumen microbiota of lambs. Our findings indicate that lamb sex influenced alpha diversity indices of the rumen microbiota. However, within the same sex, only diet composition—not post-pelleting crumbling—affected microbial diversity. Additionally, no significant differences in beta diversity were observed among the experimental groups. Similarly, Liu et al. found no differences in the alpha diversity index of rumen microbiota between lambs fed pelleted versus non-pelleted feeds, aligning with the results of this study. These findings suggest that diet composition plays a predominant role in modulating the rumen microbiota, while the physical form of feed, such as crumbling, has a minimal impact [

37].

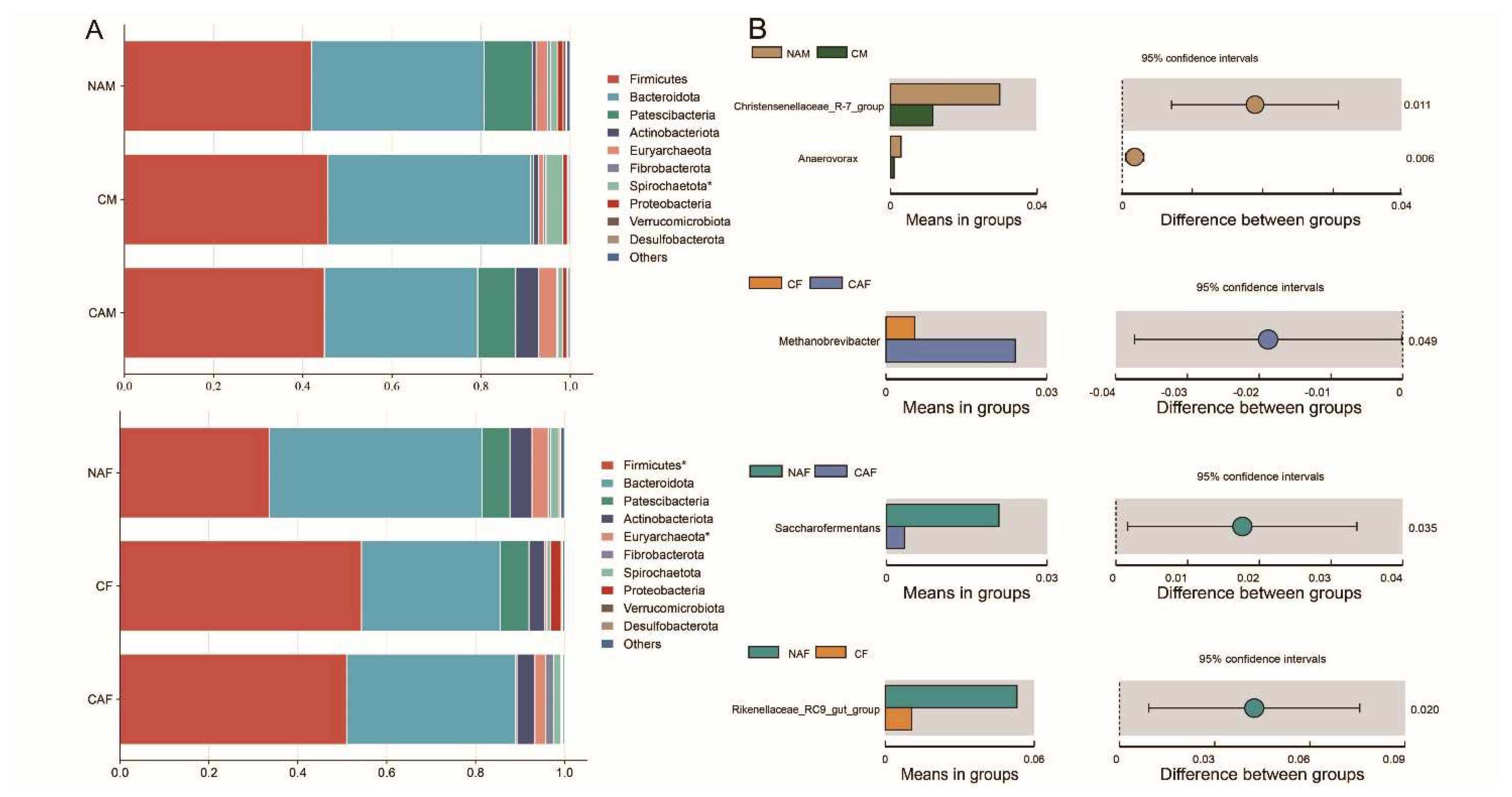

In terms of microbial composition, the dominant phyla across all groups were

Firmicutes and

Bacteroidota, with

Prevotella being the dominant genus, consistent with previous studies [

38]. This study found that pelleting or diet composition influenced the relative abundance of specific phyla and genera. Notably, the microbial groups that differed in male lambs were distinct from those in female lambs. This finding underscores the critical role of animal sex in shaping rumen microbiota and suggests that microbial responses to diet may vary between males and females. Consequently, the inclusion of both sexes in dietary and microbiome studies is vital to obtain a comprehensive understanding of microbial dynamics and dietary impacts, ensuring the broad applicability of findings across populations. Compared to physical feed form, alfalfa inclusion had a more significant influence on a broader range of microbial genera, including the

Christensenellaceae R-7 group,

Anaerovorax,

Saccharofermentans, and

Rikenellaceae RC9 gut group, all of which exhibited higher relative abundances in the non-alfalfa group. These results align with other studies, which have similarly reported increased abundances of the

Christensenellaceae R-7 group,

Saccharofermentans, and

Rikenellaceae RC9 gut group in high-concentrate diets. This suggests that these genera are sensitive to the forage-to-concentrate ratio, with the chemical composition of high-concentrate diets creating specific niches that favor their proliferation.

Our study also found that post-pelleting crumbling increased the abundance of

Methanobrevibacter. Numerous studies examining the relationship between feed efficiency and rumen microbiota in ruminants have reported an association between

Methanobrevibacter abundance and feed conversion efficiency, with higher

Methanobrevibacter abundance often observed in low feed-efficiency groups [

39] A consistent observation across these studies is that increased feed intake correlates with greater

Methanobrevibacter abundance. In this study, the post-pelleting crumbling group exhibited a notable increase in feed intake accompanied by a significant rise in

Methanobrevibacter abundance, aligning with these findings. Similarly, research on rabbits demonstrated that smaller pellet sizes enhanced both feed intake and cecum

Methanobrevibacter abundance [

40], further supporting our results. These findings underscore the role of feed intake as a key factor influencing

Methanobrevibacter abundance in the rumen. While the physical form of feed, particularly post-pelleting crumbling, did not significantly affect microbial diversity indices, it did influence the abundance of specific microbial groups. This study suggests that the physical form of feed can indirectly affect microbial composition by altering intake behavior.

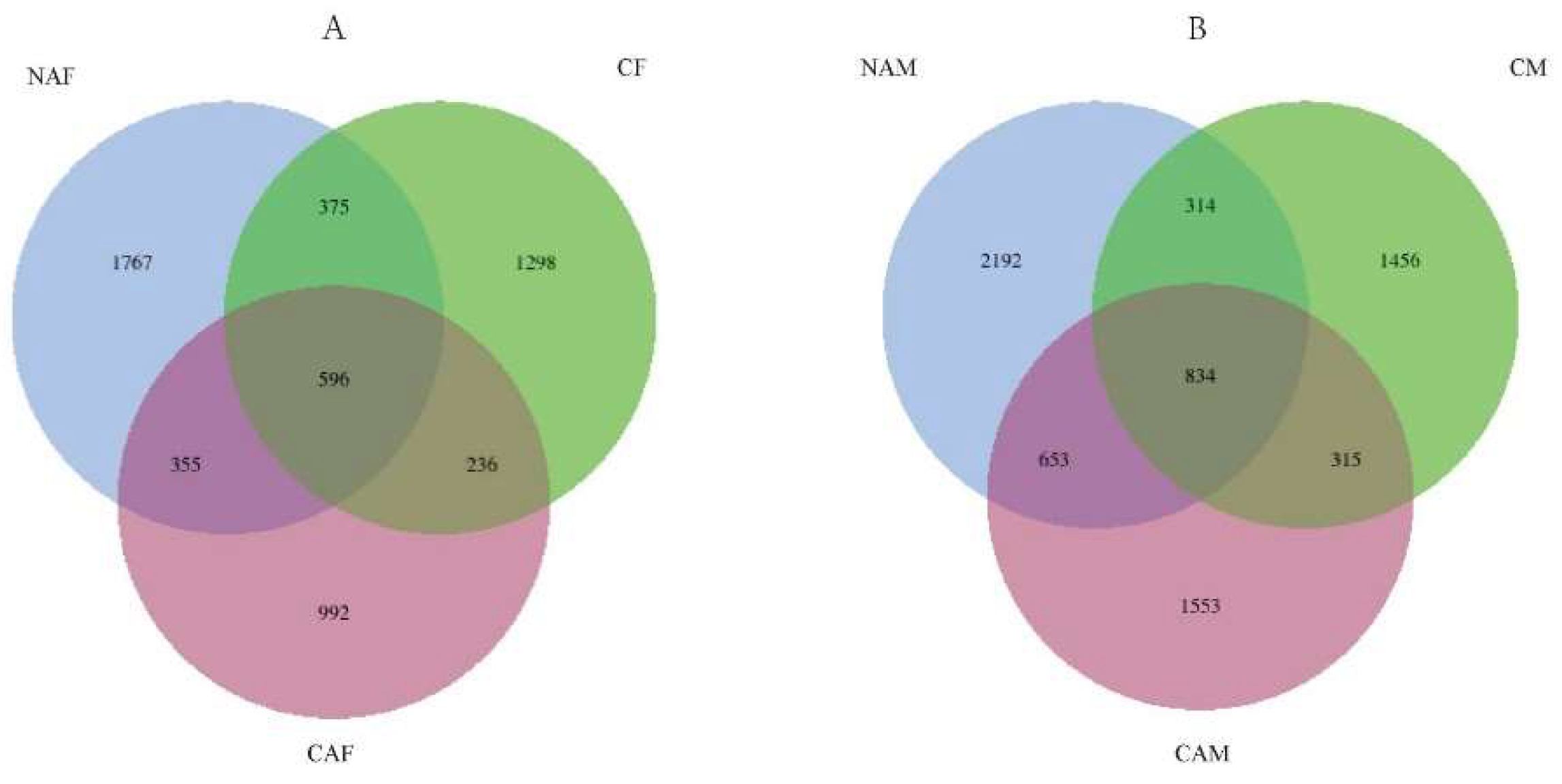

Figure 1.

Relationship between different starter feeds and rumen microbial diversity in lambs. Differences in amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were assessed among the groups. CF: Standard pelleted starter feed containing alfalfa, female lambs. CM: Standard pelleted starter feed containing alfalfa, male lambs. NAF: Standard pelleted starter feed without alfalfa, female lambs. NAM: Standard pelleted starter feed without alfalfa, male lambs. CAF: Starter feed with the same formulation as the CON group, but crumbled using a roller mill after pelleting, female lambs. CAM: Starter feed with the same formulation as the CON group, but crumbled using a roller mill after pelleting, male lambs. F: female; M: male.

Figure 1.

Relationship between different starter feeds and rumen microbial diversity in lambs. Differences in amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were assessed among the groups. CF: Standard pelleted starter feed containing alfalfa, female lambs. CM: Standard pelleted starter feed containing alfalfa, male lambs. NAF: Standard pelleted starter feed without alfalfa, female lambs. NAM: Standard pelleted starter feed without alfalfa, male lambs. CAF: Starter feed with the same formulation as the CON group, but crumbled using a roller mill after pelleting, female lambs. CAM: Starter feed with the same formulation as the CON group, but crumbled using a roller mill after pelleting, male lambs. F: female; M: male.

Figure 2.

Rumen microbial diversity indices for lambs fed different starter feeds. Diversity indices include the Chao1 index (A), Observed_features index (B), Shannon index (C), and Simpson index (D). CF: Standard pelleted starter feed containing alfalfa, female lambs. CM: Standard pelleted starter feed containing alfalfa, male lambs. NAF: Standard pelleted starter feed without alfalfa, female lambs. NAM: Standard pelleted starter feed without alfalfa, male lambs. CAF: Starter feed with the same formulation as the CON group, but crumbled using a roller mill after pelleting, female lambs. CAM: Starter feed with the same formulation as the CON group, but crumbled using a roller mill after pelleting, male lambs. F: female; M: male. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: P < 0.01 (**), P < 0.05 (*).

Figure 2.

Rumen microbial diversity indices for lambs fed different starter feeds. Diversity indices include the Chao1 index (A), Observed_features index (B), Shannon index (C), and Simpson index (D). CF: Standard pelleted starter feed containing alfalfa, female lambs. CM: Standard pelleted starter feed containing alfalfa, male lambs. NAF: Standard pelleted starter feed without alfalfa, female lambs. NAM: Standard pelleted starter feed without alfalfa, male lambs. CAF: Starter feed with the same formulation as the CON group, but crumbled using a roller mill after pelleting, female lambs. CAM: Starter feed with the same formulation as the CON group, but crumbled using a roller mill after pelleting, male lambs. F: female; M: male. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: P < 0.01 (**), P < 0.05 (*).

Figure 3.

Beta diversity analysis of rumen microorganisms across different starter feed groups, visualized using principal coordinate analysis (PCoA). CF: Standard pelleted starter feed containing alfalfa, female lambs. CM: Standard pelleted starter feed containing alfalfa, male lambs. NAF: Standard pelleted starter feed without alfalfa, female lambs. NAM: Standard pelleted starter feed without alfalfa, male lambs. CAF: Starter feed with the same formulation as the CON group, but crumbled using a roller mill after pelleting, female lambs. CAM: Starter feed with the same formulation as the CON group, but crumbled using a roller mill after pelleting, male lambs. F: female; M: male.

Figure 3.

Beta diversity analysis of rumen microorganisms across different starter feed groups, visualized using principal coordinate analysis (PCoA). CF: Standard pelleted starter feed containing alfalfa, female lambs. CM: Standard pelleted starter feed containing alfalfa, male lambs. NAF: Standard pelleted starter feed without alfalfa, female lambs. NAM: Standard pelleted starter feed without alfalfa, male lambs. CAF: Starter feed with the same formulation as the CON group, but crumbled using a roller mill after pelleting, female lambs. CAM: Starter feed with the same formulation as the CON group, but crumbled using a roller mill after pelleting, male lambs. F: female; M: male.

Figure 4.

Relationship between rumen microbial composition and type of starter feed in lambs. A: Differences in microbial composition among the groups at the phylum level. B: Differences in microbial composition among the groups at the genus level. CF: Standard pelleted starter feed containing alfalfa, female lambs. CM: Standard pelleted starter feed containing alfalfa, male lambs. NAF: Standard pelleted starter feed without alfalfa, female lambs. NAM: Standard pelleted starter feed without alfalfa, male lambs.CAF: Starter feed with the same formulation as the CON group, but crumbled using a roller mill after pelleting, female lambs. CAM: Starter feed with the same formulation as the CON group, but crumbled using a roller mill after pelleting, male lambs. F: female. M: male. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: P < 0.01 (**), P < 0.05 (*).

Figure 4.

Relationship between rumen microbial composition and type of starter feed in lambs. A: Differences in microbial composition among the groups at the phylum level. B: Differences in microbial composition among the groups at the genus level. CF: Standard pelleted starter feed containing alfalfa, female lambs. CM: Standard pelleted starter feed containing alfalfa, male lambs. NAF: Standard pelleted starter feed without alfalfa, female lambs. NAM: Standard pelleted starter feed without alfalfa, male lambs.CAF: Starter feed with the same formulation as the CON group, but crumbled using a roller mill after pelleting, female lambs. CAM: Starter feed with the same formulation as the CON group, but crumbled using a roller mill after pelleting, male lambs. F: female. M: male. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: P < 0.01 (**), P < 0.05 (*).

Table 1.

Dietary formulation and nutrient levels (air-dry basis).

Table 1.

Dietary formulation and nutrient levels (air-dry basis).

| Ingredients |

Percentage (%) and Group |

| CON and CA Group |

NA Group |

| Alfalfa |

7.90 |

—— |

| Corn |

37.30 |

40.30 |

| Extruded soybeans |

2.50 |

2.50 |

| Whey powder |

1.50 |

1.50 |

| Corn bran |

6.35 |

9.25 |

| Soybean meal |

18.25 |

19.25 |

| Cottonseed meal |

5.00 |

5.00 |

| DDGS |

12.00 |

13.00 |

| Bio-fermented feed |

2.50 |

2.50 |

| Limestone |

1.70 |

1.70 |

| Premix |

5.00 |

5.00 |

| Total |

100.00 |

100.00 |

| Chemical composition |

Content |

|

| DM (%) |

93.55 |

93.01 |

| DE (MJ·kg-1) |

12.68 |

13.00 |

| CP (%) |

22.38 |

22.58 |

| NDF (%) |

16.27 |

14.00 |

| ADF (%) |

7.37 |

6.35 |

| Ca (%) |

1.38 |

1.20 |

| P (%) |

0.38 |

0.50 |

Table 2.

Physical properties and starch gelatinization of starter feeds with different forms.

Table 2.

Physical properties and starch gelatinization of starter feeds with different forms.

| Treatment |

Hardness (ѱ N) |

Density ( ρ g/cm3) |

Starch Gelatinization (%) |

| CON |

230.94a

|

0.90 |

22.36b

|

| NA |

205.11a

|

0.92 |

33.76a

|

| CA |

27.34b

|

0.82 |

23.65b

|

| SEM |

10.473 |

0.073 |

0.020 |

|

P-value |

<0.001 |

0.397 |

0.002 |

Table 3.

Effects of starter feed form on lamb growth performance and starter intake.

Table 3.

Effects of starter feed form on lamb growth performance and starter intake.

| Items |

Groups |

Main Effects |

SEM |

P-value |

| F |

M |

CON |

NA |

CA |

F |

M |

Feed |

Sex |

F×S |

| CON |

NA |

CA |

CON |

NA |

CA |

| BW (kg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| BW7 |

3.83 |

3.81 |

3.79 |

4.20 |

4.10 |

4.52 |

4.02 |

3.95 |

4.15 |

3.81 |

4.27 |

0.090 |

0.636 |

0.008 |

0.564 |

| BW21 |

5.49 |

5.45 |

5.31 |

6.25 |

6.15 |

6.00 |

5.87 |

5.80 |

5.65 |

5.42 |

6.13 |

0.120 |

0.770 |

0.005 |

0.992 |

| BW35 |

7.02 |

6.76 |

6.88 |

8.03 |

7.65 |

8.02 |

7.52 |

7.20 |

7.45 |

6.89 |

7.90 |

0.170 |

0.733 |

0.004 |

0.959 |

| BW49 |

8.48 |

7.93 |

9.43 |

9.43 |

8.96 |

10.06 |

8.96 |

8.44 |

9.74 |

8.61 |

9.48 |

0.230 |

0.080 |

0.061 |

0.934 |

| ADG (kg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ADG7-21 |

0.12 |

0.12 |

0.11 |

0.15 |

0.15 |

0.11 |

0.13a |

0.13a |

0.11b |

0.11 |

0.13 |

0.000 |

0.030 |

0.039 |

0.258 |

| ADG21-35 |

0.11 |

0.09 |

0.11 |

0.13 |

0.11 |

0.14 |

0.12 |

0.10 |

0.13 |

0.10 |

0.13 |

0.010 |

0.142 |

0.063 |

0.798 |

| ADG35-49 |

0.10 |

0.08 |

0.18 |

0.10 |

0.09 |

0.15 |

0.10b |

0.09b |

0.16a |

0.12 |

0.11 |

0.010 |

0.000 |

0.463 |

0.398 |

| ADG7-49 |

0.11 |

0.10 |

0.13 |

0.12 |

0.12 |

0.13 |

0.12ab |

0.11b |

0.13a |

0.11 |

0.12 |

0.000 |

0.049 |

0.254 |

0.609 |

Table 4.

Effects of starter feed form on starter intake.

Table 4.

Effects of starter feed form on starter intake.

| Items |

Main Effects |

SEM |

P-value |

| CON |

NA |

CA |

| FI 7-21 |

6.66b |

7.32b |

9.44a |

0.191 |

<0.001 |

| FI 21-35 |

25.28b |

17.25c |

57.99a |

1.823 |

<0.001 |

| FI 35-49 |

92.15b |

50.92c |

159.85a |

5.066 |

<0.001 |

| FI 7-49 |

41.36b |

25.16c |

75.76a |

2.281 |

<0.001 |

Table 5.

Effects of different food feeds and sex on nutrient digestibility.

Table 5.

Effects of different food feeds and sex on nutrient digestibility.

| Items |

Groups |

Main Effects |

SEM |

P-value |

| F |

M |

CON |

NA |

CA |

F |

M |

Feed |

Sex |

F×S |

| CON |

NA |

CA |

CON |

NA |

CA |

| CP |

0.62 |

0.62 |

0.85 |

0.82 |

0.78 |

0.84 |

0.72b |

0.70b |

0.85a |

0.70 |

0.81 |

0.024 |

0.060 |

0.027 |

0.216 |

| NDF |

0.43 |

0.67 |

0.67 |

0.60 |

0.67 |

0.64 |

0.51b |

0.67a |

0.66a |

0.59 |

0.64 |

0.014 |

0.001 |

0.130 |

0.028 |

| ADF |

0.36 |

0.54 |

0.59 |

0.52 |

0.63 |

0.45 |

0.44b |

0.59a |

0.52a |

0.50 |

0.53 |

0.014 |

0.003 |

0.215 |

0.001 |

| DM |

0.80 |

0.79 |

0.76 |

0.73 |

0.76 |

0.80 |

0.77 |

0.78 |

0.78 |

0.78 |

0.76 |

0.018 |

0.956 |

0.681 |

0.382 |

| OM |

0.81 |

0.80 |

0.78 |

0.74 |

0.78 |

0.82 |

0.78 |

0.79 |

0.80 |

0.80 |

0.78 |

0.017 |

0.900 |

0.534 |

0.423 |

Table 6.

Effects of different starter feed form and sex on rumen fermentation of lambs.

Table 6.

Effects of different starter feed form and sex on rumen fermentation of lambs.

| Items |

Groups |

Main Effects |

SEM |

P-value |

| F |

M |

CON |

NA |

CA |

F |

M |

Feed |

Sex |

F×S |

| CON |

NA |

CA |

CON |

NA |

CA |

Acetic acid

(mmol/L) |

45.73 |

44.17 |

44.15 |

48.43 |

38.40 |

36.83 |

47.08 |

41.28 |

40.49 |

44.68 |

41.22 |

2.368 |

0.473 |

0.471 |

0.653 |

Propionic acid

(mmol/L) |

14.64 |

12.38 |

15.43 |

15.48 |

10.23 |

9.72 |

15.06a |

11.31b |

12.57ab |

14.15 |

11.81 |

0.518 |

0.019 |

0.031 |

0.050 |

Isobutyric acid

(mmol/L) |

1.78 |

1.48 |

1.90 |

1.42 |

1.15 |

1.07 |

1.60 |

1.31 |

1.48 |

1.72 |

1.21 |

0.098 |

0.497 |

0.014 |

0.520 |

Butyric acid

(mmol/L) |

5.06 |

4.42 |

6.11 |

6.44 |

3.48 |

3.99 |

5.75 |

3.95 |

5.05 |

5.20 |

4.64 |

0.365 |

0.146 |

0.448 |

0.155 |

Isovaleric acid

(mmol/L) |

0.84 |

0.86 |

1.22 |

0.93 |

0.52 |

0.72 |

0.88 |

0.69 |

0.97 |

0.97 |

0.72 |

0.075 |

0.312 |

0.110 |

0.273 |

Valeric acid

(mmol/L) |

0.74 |

0.64 |

0.81 |

0.76 |

0.57 |

0.60 |

0.75a |

0.61b |

0.71a |

0.73 |

0.65 |

0.025 |

0.080 |

0.107 |

0.187 |

Total acid

(mmol/L) |

71.67 |

66.83 |

72.50 |

76.34 |

57.24 |

55.81 |

74.00 |

62.04 |

64.16 |

70.34 |

63.13 |

3.168 |

0.273 |

0.264 |

0.386 |

| Acetate/propionic acid |

3.13 |

3.48 |

2.88 |

3.09 |

3.75 |

3.68 |

3.11 |

3.61 |

3.28 |

3.16 |

3.51 |

0.107 |

0.171 |

0.120 |

0.284 |