1. Introduction

Rivers are the vital link between terrestrial ecosystems and marine ecosystems, which play an important role in the transport of matter and energy [

1]. The high heterogeneity of river habitat provides the complex living environment for aquatic organisms such as fish, zoobenthos and zooplankton [

2]. Under the dual influence of human activities and climate change, the structure and function of river ecosystem are facing serious challenges [

3]. The studies about restoration and protection of river ecosystem are one of the hotspots in global ecological research [

4].

The Yellow River, the second longest river in China, is an important corridor connecting the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, the Loess Plateau and the North China Plain [

5]. Ecological protection and sustainable development of the Yellow River Basin play a significant part in social and economic development [

6]. Because the Yellow River is affected by the continental monsoon climate in the north of China, glaciation period is from October to March of each year. Before and after the glaciation period, there will be an ice flood in the Yellow River basin [

7]. Due to the blockage of the river channel and the resistance of the water flow, the water level of the Yellow River rises obviously during the ice flood [

8]. Besides, as the middle reaches of the river flow through the Loess Plateau, a large amount of sediment enters the Yellow River making it have the largest sediment content in the world [

9]. The water resource management measures in the Xiaolangdi Hydraulic Project have a significant impact on the dynamic changes of water and sediment in the downstream of the Yellow River [

10], which in turn affects the aquatic biological community and ecosystem structure and function [

11]. In addition, human activities in city and brackish water intersection in estuarine area make the habitat characteristics very complicated in the downstream of the Yellow River [

12].

Zooplankton fed on bacteria and phytoplankton, is an important food source for aquatic animals [

13]. Zooplankton play an important role in the material circulation and energy flow of river ecosystems [

14]. As primary consumers in aquatic ecosystems, zooplankton can have significant impacts on primary producers and secondary consumers through "upward" and "downward" effects [

15]. Zooplankton is very sensitive to changes in water environment, so its species composition, standing stock and community stability can be used as effective indicators to evaluate the health of river ecosystems [

16]. A Study has shown that the Yellow River section with high sediment content and high velocity is not the best place for zooplankton especially large crustaceans to survive [

17]. At present, there have been reports on the zooplankton community in the downstream of the Yellow River, mostly concentrated in the tributaries or estuaries, and few reports on the zooplankton community in main stream of the Yellow River [

18,

19,

20].

In the present study, the Shandong section of the Yellow River was selected as the research area to conduct quantitative surveys of zooplankton in spring (March), summer (June), autumn (October) and winter (December) in 2022. The purposes of this study: (1) To investigate the temporal and spatial changes of species composition, standing stock and community structure of zooplankton in the Shandong section of the downstream of Yellow River; (2) By analyzing the spatial and temporal patterns and stability characteristics of zooplankton community, the seasonal dynamic changes and spatial heterogeneity of zooplankton community in the downstream of the Yellow River were revealed. The research focuses on the frontiers, hot spots and key issues of river ecology research. The results of this study can provide reference for ecological protection and high-quality development of the Yellow River basin.

2. Study Area and Research Methods

2.1. Study Area Description

With a total length of 5,464 kilometers, the Yellow River originates from the northern foothills of the Bayan Har Mountains on the Tibetan Plateau [

1]. The upper reaches flow through the provinces of Qinghai, Sichuan, Gansu and Ningxia, the middle reaches pass through the provinces of Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi and Shanxi, and the lower reaches flow through the provinces of Henan and Shandong [

21]. Shandong section of the Yellow River (34°26′~38°16′ N, 114°16′~119°16′ E) is about 628 km long [

22]. It flows through the cities of Heze, Jining, Taian, Liaocheng, Dezhou, Jinan, Zibo and Binzhou, and ultimately empties into the Bohai Sea at Dongying City [

23]. Because this section is located in temperate continental monsoon climate area, the precipitation is mainly concentrated in the summer [

24]. The annual precipitation ranges from 640 to 700 mm, and the average annual temperature is approximately 13 °C [

25].

2.2. Sample Designing

This study had conducted quantitative zooplankton sampling surveys on Shandong section of the Yellow River in March (spring), June (summer), October (autumn), and December (winter) 2022. A total of 29 sampling sites (S1~S29) were set along the mainstream of the Yellow River within the survey area (

Figure 1), where the distance between each sampling point is approximately 20 km. Based on the different factors between different reaches, the surveyed river section was divided into four reaches: XLDR, DPHR, JNR and ER. XLDR is the reach affected by Xiaolangdi Hydraulic Project, which includes 8 sampling sites (S1~S8). DPHR is the reach affected by water input from the Dawen River and Dongping Lake, which includes 6 sampling sites (S9~S14). JNR is the reach affected by the urban area of Jinan, which includes 5 sampling sites (S15~S19). ER is affected by the tide in the estuary of the Yellow River, which includes 10 sampling sites (S20~S29).

2.3. Sample Collection and Identification

Zooplankton and water samples were collected in the shallow nearshore riverbed areas of the Yellow River during four seasons. In winter, sample collection activities in frozen river were carried out after ice-breaking. A 5 L water sampler was used to collect 30 L mixed water at a depth of 50 cm. A 25# plankton net (mesh size, 64 μm) was used to filter the water and obtain a zooplankton sample. The sample was transferred to 50 mL specimen bottles with 4% formalin.

Zooplankton samples were taken back to the laboratory and stained with Sodium Acid Red 52 for 24 hours. Species identification and counting were performed under a stereomicroscope (Olympus SZ61). In the present study, copepod nauplii were considered as one taxon and not included in the count of the dominant species. When there were more than 2000 individuals in one sample, the subsample method was used to estimate the actual number [

26]. Three faunas were used for zooplankton identification [

27,

28,

29].

2.4. Water Environmental Factors Determination

Water temperature (WT), pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), and conductivity (Cond) were measured on-site using a multi-parameter water quality analyzer (YSI EX02). Total phosphorus (TP) was determined using the continuous flow ammonium molybdate spectrophotometric method, total nitrogen (TN) was measured using the potassium persulfate UV spectrophotometric method, nitrate nitrogen (NO₃⁻-N) was determined by UV spectrophotometry, ammonia nitrogen (NH₄⁺-N) was measured using the salicylic acid spectrophotometric method, and total organic carbon (TOC) was determined by chemical oxidation.

2.5. Data Statistical Analysis

The dominance index (

Y) is calculated using the following formula: [

30]

where

ni is the abundance of the

i-th species,

N is the total abundance of all zooplankton, and

fi is the occurrence frequency of the

i-th species. When the dominance index

Y ≥ 0.02, the species is considered as the dominant species.

The density of zooplankton was calculated by dividing the number of zooplankton individuals by the sampling volume, and it was expressed in ind./L. The biomass of zooplankton was calculated by referring to the method reported by Zhang & Huang [

26]. The weight of each nauplii was estimated to be approximately 0.003 mg [

31]. The VennDiagram package in R v4.1.2 was used to generate a diagram of zooplankton species to compare seasonal differences and spatial heterogeneity of the species composition. One-way ANOVA was used to analyze the density and biomass of zooplankton and to determine the differences between four seasons and four river reaches through the software SPSS 26. When the significance level

P value was less than 0.05, there was a significant difference between two samples. In the statistical analysis software Primer 5.0, zooplankton density data were analyzed using a sorted similarity matrix based on the Bray-Curtis similarity measure. The similarity analysis (ANOSIM) of zooplankton communities was conducted, and the multidimensional non-metric (NMDS) ranking map was made to reveal the characteristics of zooplankton communities. The software Canoco for Windows 4.5 was used to perform redundancy analysis (RDA) for zooplankton and water physicochemical factors, and Monte Carlo tests were used to identify environmental factors which had significant effects on zooplankton.

The collinear network maps of zooplankton in different seasons and different river reaches were generated through the software Gephi 0.9.2. When the zooplankton collinear network analysis diagram was made, the zooplankton species were taken as the image nodes, and the correlation coefficients between the nodes were calculated using the "psych package" in R v4.1.2 software. At the same time, the density (D) and average clustering coefficient (T) were calculated in the software Gephi 0.9.2. The stability of zooplankton community structure in different seasons and river reaches was evaluated by comparing the D/T ratio. The smaller the value of D/T, the more stable the community structure, and the larger the value of D/T, the more unstable the community structure.

3. Results

3.1. Species Composition of Zooplankton

3.1.1. Species Richness

In the present study, a total of 119 species of zooplankton were identified and recorded. There were 70 species of Rotifera (58.82%), 29 species of Cladocera and 20 species of Copepoda. These three main species made up 58.82%, 24.37% and 16.81% of the total species number, respectively. The one-way ANOVA revealed that the numbers of zooplankton species had significant seasonal differences (P<0.05). There was no significant spatial difference in zooplankton species.

In terms of four seasons (

Figure 2-A), species richness of zooplankton was the highest in summer (81 species), followed by spring and autumn with 66 and 56 species, respectively. There were only 36 species in winter. The Venn diagram of zooplankton species showed that there were 15 species in the four seasons, including 7 Rotifers, 2 Cladocerans and 6 Copepods. In summer, the most endemic species (25 species) were found, followed by spring and autumn with 13 and 10 species, respectively, and only 6 endemic species were found in winter.

In terms of four reaches (

Figure 2-B), species richness of zooplankton was the highest in XLDR (87 species), followed by ER, JNR and DPHR with 83, 78 and 72 species, respectively. The Venn diagram of zooplankton species showed that there were 48 species in the four reaches, including 23 Rotifers, 9 Cladocerans and 16 Copepods. In XLDR, the most endemic species (11 species) were found, followed by ER and JNR with 9 and 7 species, respectively, and only 3 endemic species were found in DPHR.

3.1.2. Dominant Species

The dominant species of zooplankton showed significant temporal and spatial heterogeneity between the four seasons and the four river reaches (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

In four seasons (

Table 1), the number of dominant species of zooplankton in autumn was the largest (6 species), and the other three seasons was the same (4 species).

Brachionus calyciflorus was a common and dominant species in all four seasons.

Brachionus angularis,

Keratella quadrala, and

Filinia maior only dominated in spring.

Brachionus diversicornis and

Diaphanosoma dubium only dominated in summer.

Schmackeria forbesi,

Microcyclops varicans and

Mesocyclops leuckarti only dominated in autumn.

Notholca labis and

Polyarthra dolichoptera only dominated in winter.

In four reaches (

Table 2), JNR and ER had four dominant species, while XLDR and DPHR had three dominant species.

B. calyciflorus and

Bosmina longirostris were the common and dominant species in four reaches.

Diaphanosoma dubium was an endemic and dominant species in XLDR.

Sinocalanus dorrii was an endemic and dominant species in DPHR. JNR and ER had no endemic and dominant species.

3.2. Standing Stock of Zooplankton

3.2.1. Density

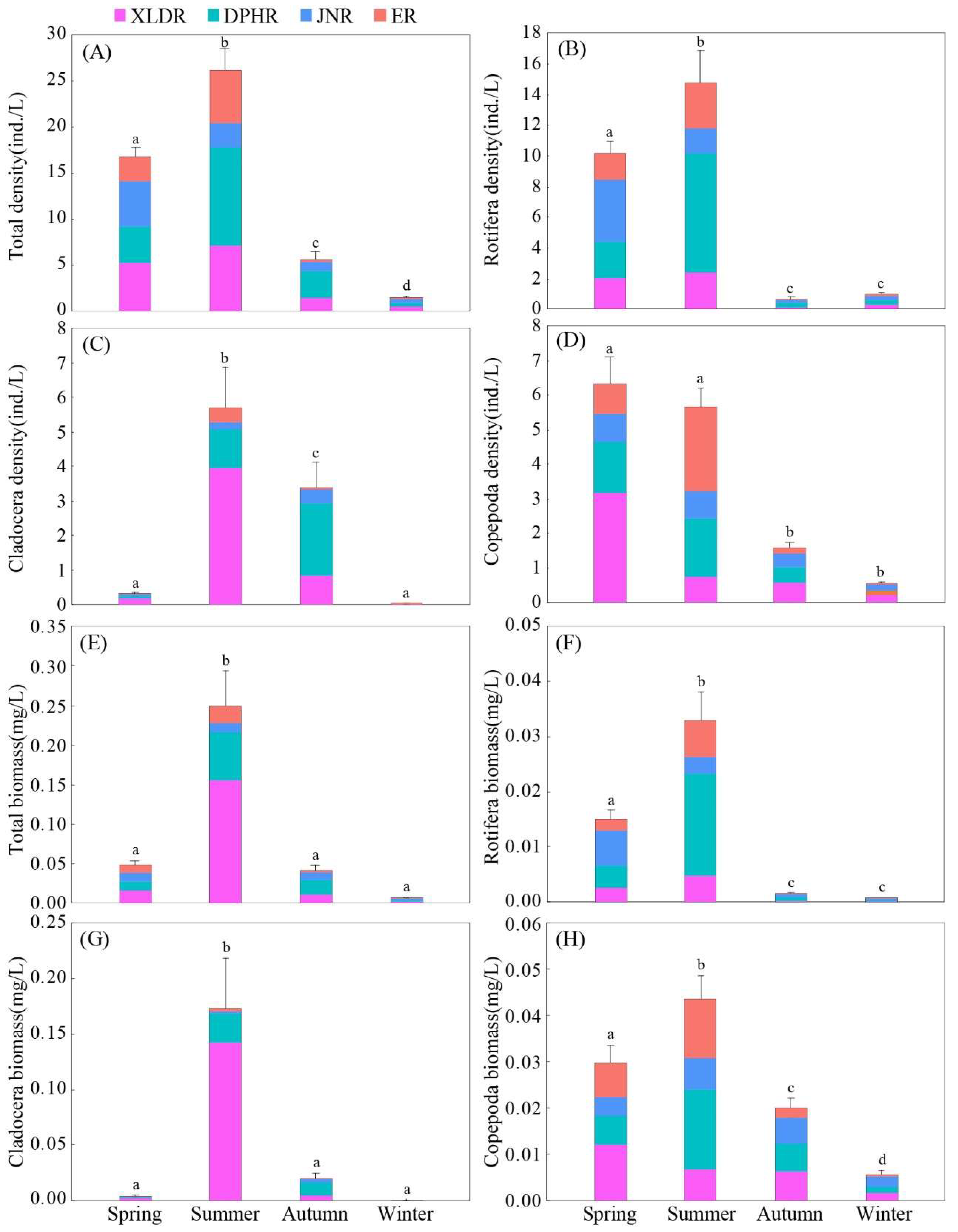

The average density of zooplankton in the Shandong section of the Yellow River during four seasons was (12.53±5.57) ind./L. The total density of zooplankton was mainly contributed by rotifers, accounting for 52.74%, while the density of cladocerans (18.83%) and copepods (28.43%) was smaller.

There were significant seasonal differences in density of zooplankton (

P<0.05). Density of zooplankton in summer (26.17 ind./L) and spring (16.76 ind./L) was significantly higher than that in autumn (5.65 ind./L) and winter (1.56 ind./L) (

Figure 3-A). The seasonal variation of density of rotifers (

Figure 3-B) and copepods (

Figure 3-C) was consistent with total density of zooplankton. However, density of cladocerans (

Figure 3-D) in summer (5.68 ind./L) and autumn (3.39 ind./L) was significantly higher than that in spring (0.32 ind./L) and winter (0.031 ind./L).

There were significant differences among four reaches in density of zooplankton (P< 0.05). Density of zooplankton in DPHR (18.41 ind./L) and XLDR (14.19 ind./L) was significantly higher than that in JNR (9.52 ind./L) and ER (8.84 ind./L). The spatial distribution characteristics of density of cladocerans and copepods was consistent with density of zooplankton. However, density of rotifers in DPHR was significantly higher than that in other three reaches.

3.2.2. Biomass

The average biomass of zooplankton in the Shandong section of the Yellow River during four seasons was (0.087±0.055) mg/L. The total biomass of zooplankton was mainly contributed by cladocerans, accounting for 56.94%, while the biomass of rotifers (14.43%) and copepods (28.63%) was smaller.

There were significant seasonal differences in biomass of zooplankton (

P<0.05). The highest biomass of zooplankton was in summer (0.249 mg/L), followed by spring (0.049 mg/L), autumn (0.042 mg/L), and winter (0.006 mg/L) (

Figure 3-E). The seasonal variation of biomass of rotifers (

Figure 3-F) and copepods (

Figure 3-H) was consistent with the total biomass of zooplankton. However, biomass of cladocerans in summer (0.176 mg/L) was significantly higher than that in other three seasons (

Figure 3-G).

There were significant differences among four reaches in biomass of zooplankton (P< 0.05). Biomass of zooplankton in the upper reaches was significantly higher than that in the lower reaches. The highest biomass of zooplankton was in XLDR (0.189 mg/L), followed by DPHR (0.096 mg/L), JNR (0.037 mg/L) and ER (0.035 mg/L). The spatial distribution characteristics of biomass of cladocerans and copepods were consistent with biomass of zooplankton. However, the DPHR (0.024 mg/L) was significantly higher than that of the other three reaches.

3.3. Characteristics of Zooplankton Community Structure

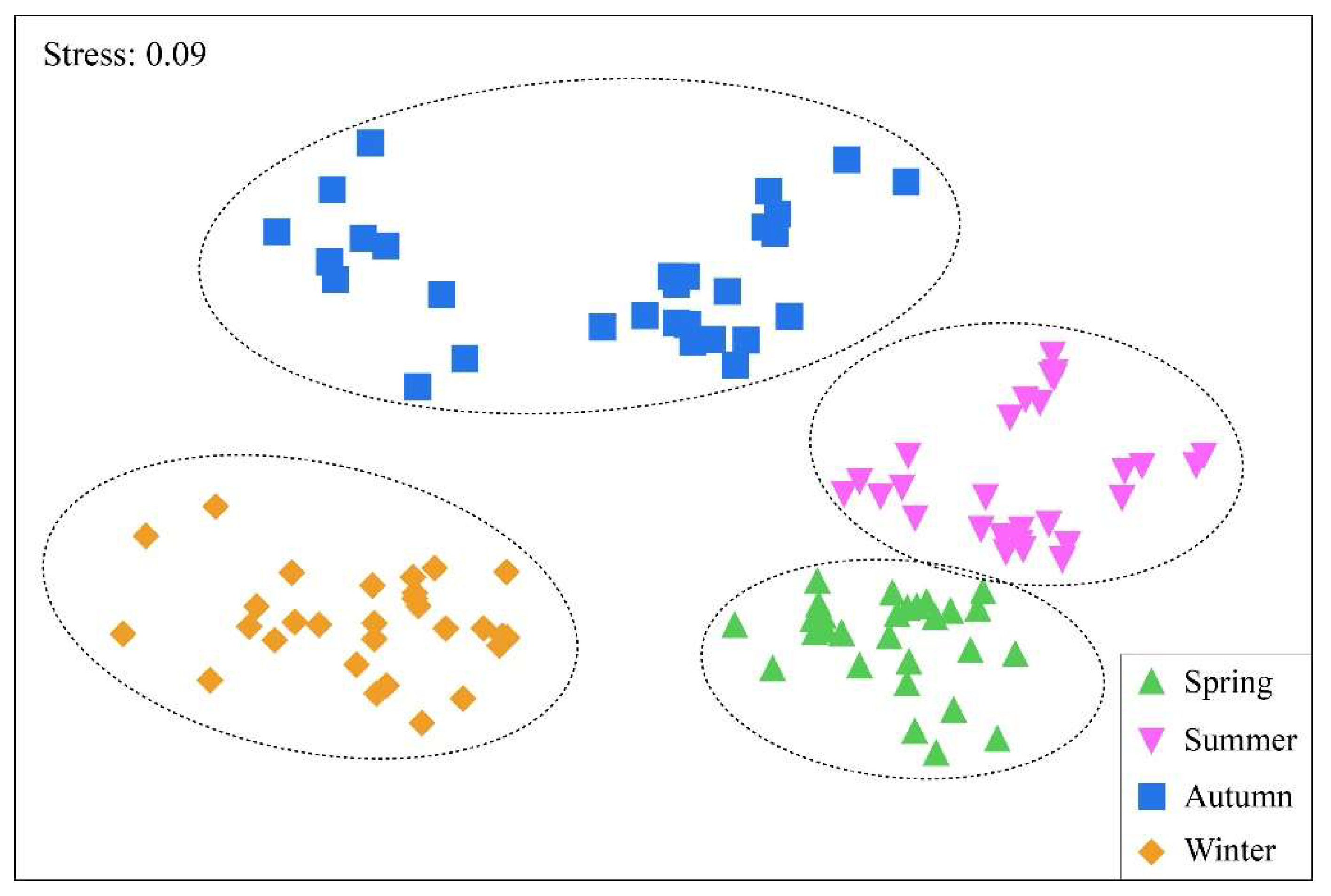

Temporally, zooplankton could be clearly distinguished into four communities: spring community, summer community, autumn community and winter community (

Figure 4). Similarity analysis (ANOSIM) revealed significant differences in zooplankton communities between the four seasons (Global test: R=0.844,

P=0.001).

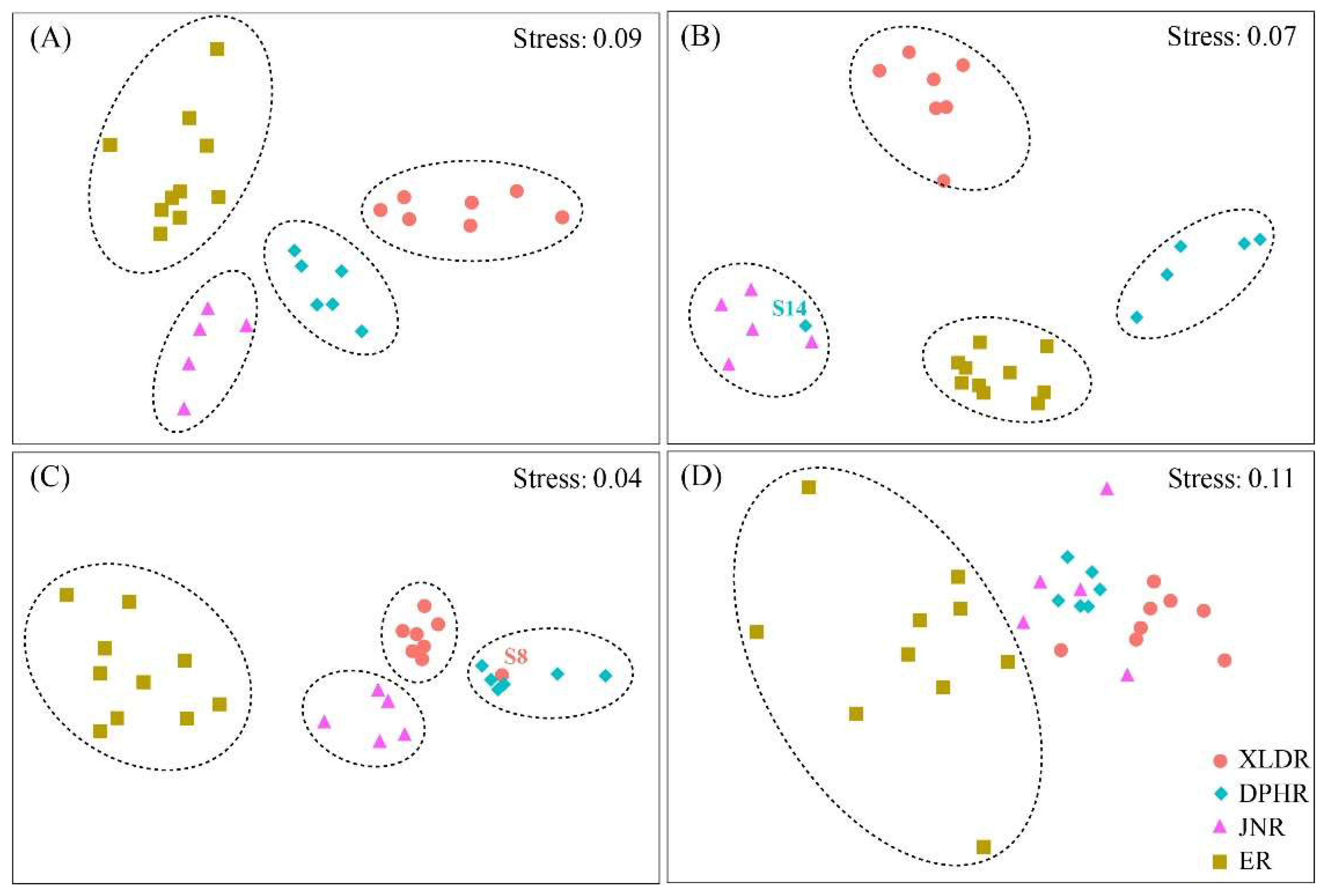

Spatially, zooplankton could be clearly divided into four communities in spring, summer and autumn, which were XLDR community, DPHR community, JNR community and HKR community (

Figure 5-A–C). Similarity analysis (ANOSIM) revealed that there were significant differences in zooplankton communities among the four reaches. The results of Global test were as follows: spring (R=0.876,

P=0.001), summer (R=0.912,

P=0.001) and autumn (R=0.823,

P=0.001). In winter, only the zooplankton in ER gathered into a single community, and the zooplankton community structure differentiation of the other three reaches was low (Global test: R=0.44, P=0.001) (

Figure 7-D).

3.4. Relationship Between Zooplankton and Water Environmental Factors

Based on the redundancy analysis (RDA) of zooplankton abundance and water physicochemical factors, the contribution rate of pH, water temperature (WT), electrical conductivity (Cond) and dissolved oxygen (DO) to the total variance of the seasonal differences of zooplankton communities was 91.2%. Among them, the variance contribution rate of the first characteristic axis was 48.4%, and that of the second characteristic axis was 42.8% (

Figure 6-A). Monte Carlo test showed that pH, WT, Cond and DO had significant effects on the community structure of zooplankton (

P=0.002). There was a significant positive correlation between zooplankton community and Cond in spring. However, the zooplankton community was significantly positively correlated with WT and pH in summer. In addition, Monte Carlo test results revealed that most zooplankton were positively correlated with WT, pH, and electrical Cond.

Figure 6.

Redundancy analysis (RDA) based on zooplankton abundance and water physicochemical factors (The black triangles represent the species of zooplankton, and the dots represent samples from each season).

Figure 6.

Redundancy analysis (RDA) based on zooplankton abundance and water physicochemical factors (The black triangles represent the species of zooplankton, and the dots represent samples from each season).

Figure 7.

Collinear network analysis based on zooplankton abundance.

Figure 7.

Collinear network analysis based on zooplankton abundance.

The results of redundancy analysis (RDA) based on zooplankton abundance and nutrient salts showed that the contribution rate of five nutrients (NO

3--N, NH

4+-N, TN, TOC and TP) to the total variance of seasonal differences of zooplankton communities was 91.0%. The variance contribution of the first characteristic axis was 61.2%, and the variance contribution of the second characteristic axis was 29.8% (

Figure 6-B). The results of Monte Carlo test showed that TN, NO

3--N, TP and NH

4+-N had significant effects on the community structure of zooplankton (TN:

P=0.002, NO

3--N:

P=0.002, TOC:

P=0.002, NH

4+-N:

P=0.008,). There was not significant effect of TOC on zooplankton community (

P=0.314). RDA results also showed that the zooplankton community in spring had a significant positive correlation with NO

3--N, NH

4+-N and TN, and a significant negative correlation with TP (

Figure 6-B).

3.5. Stability of Zooplankton Community

The results of collinear network analysis showed that there were differences in the stability of zooplankton communities in four seasons and four reaches. Temporally, the D/T (value=0.060) of the zooplankton community in summer was the lowest which indicated that the zooplankton community structure in summer was the most stable (

Figure 7-J). However, the D/T (value=0.158) of the zooplankton community in winter was the highest, indicating that the zooplankton community structure in winter was the most unstable. Spatially, the zooplankton community of XLDR had the lowest D/T (value=0.086), which indicated that zooplankton community structure of XLDR was the most stable. However, the zooplankton community of JNR had the highest D/T (0.015). indicating that zooplankton community structure of JNR was the most unstable.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Spatial-Temporal Pattern of Zooplankton Species Composition

In this present study, a total of 119 zooplankton species were found in Shandong section of the Yellow River, which was significantly higher than the number of zooplankton species reported in recent studies [

10,

32]. It may be related to the comprehensive duration of the study (four seasons) and the dense of setting location (29 sampling sites). For example, in a study conducted by Leng et al. in the same river section, only 10 sampling points were set over a 5-month period, and the survey recorded only 28 zooplankton species. In addition, the increase in the number of zooplankton species may be closely related to the ecological protection efforts in the Yellow River basin over the past decade [

33]. Other studies had found that there were significantly seasonal differences in the species composition of zooplankton in the Yellow River, with a notably higher number of species in summer compared to that in winter [

34]. In this study, the seasonal variation in zooplankton species was consistent with previous findings. This strongly indicated that seasonal climate changes directly drive variations in physicochemical factors, which had a significant impact on the species composition of zooplankton [

35].

The spatial differences in zooplankton species composition between the four river reaches were not significant, which was related to the connectivity of the river and to the high similarity in habitats among the studied river reaches [

36]. 29 sampling points in this study were located in the lower the Yellow River, which exhibited typical hydrological features of downstream reaches, such as wide riverbeds and high sediment content [

37]. Previous studies had pointed out that rotifers were highly adaptable to environmental changes and had a wide distribution range [

37]. The results of this study were consistent with this, as the common species across all four seasons and four river reaches were primarily rotifers. This study also found that

Brachionus calyciflorus was the common and dominant species across the four seasons and river reaches. This suggested that

Brachionus calyciflorus was a generalist species with a wide ecological niche, well adapted to the varying physicochemical environments of the lower Yellow River throughout the different seasons [

38]. Another result of this study indicated that the JNR and HKR had a higher number of special zooplankton species, but these special species were not dominant. This suggested that urban wastewater discharge and the confluence of fresh and saline waters had created a unique aquatic environment, providing favorable living conditions for the exclusive zooplankton species [

39].

4.2. The Spatial-Temporal Pattern of Zooplankton Standing Current

The results of this study indicated that there was a seasonal synchrony in the standing stock of zooplankton, with density and biomass of zooplankton following the seasonal pattern: summer > spring > autumn > winter. This pattern was consistent with the findings of many other studies on standing stock of zooplankton in rivers [

40,

41]. Previous research had pointed out that water temperature is a key factor influencing the growth, development, and reproduction of zooplankton [

42], and the findings of this study supported this conclusion. The main reason for this pattern was that as the temperature increases, the growth rate of zooplankton accelerated and the reproductive cycle of zooplankton shortens, leading to a rapid increase in their density and biomass during the summer [

43]. The low biomass of zooplankton in winter is due to the fact that many species cope with the cold winter conditions by producing resting eggs or cysts [

44]. The correlation analysis between zooplankton and environmental factors in this study indicated that the zooplankton community in the lower Yellow River was significantly positively correlated with WT, while in winter, the community structure showed a significant negative correlation with WT. This also revealed that the standing stock of zooplankton was significantly affected by WT.

The spatial distribution of standing stock of zooplankton in the four studied reaches followed a pattern of decreasing from upstream to downstream, which was not consistent with the findings of other studies on zooplankton in domestic rivers [

45,

46]. This discrepancy may have been due to the influence of hydraulic engineering projects, lake water input, urban human activities, and tidal effects on the hydrological environment and nutrient distribution in the studied reaches, which drove the heterogeneous distribution of standing stock of zooplankton along the river [

11,

47]. This study found that the standing stock of zooplankton in autumn was significantly lower than that in summer, particularly the density and biomass of Cladocera were significantly lower in autumn than in summer. This was not only influenced by seasonal changes in water conditions [

35], but also directly related to the water diversion and sediment regulation activities in the upstream hydraulic projects during the summer and autumn zooplankton surveys [

10]. During the summer zooplankton sampling, the upstream water management projects had not carried out water diversion or sediment regulation, while in autumn, water diversion and sediment regulation activities increased the water flow speed and sediment content in XLDR. This kind of water environment was unsuitable for the survival of Cladocera [

48]. This study found that zooplankton standing stock in DPHR during summer was significantly higher than in the other three reaches, with rotifers contributing 74.88% to the total standing stock. This was primarily due to the rising water levels of the Yellow River′s tributaries, such as the Dawen River and Dongping Lake. It could carry large amounts of organic debris and nutrients into the nearby DPHR [

49]. The abundant food resources led to a massive proliferation of rotifers [

50]. This study found that the density of rotifers in JNR during spring was significantly higher than in other reaches. This is due to the input of urban domestic sewage from the nearby city of Jinan, which increased the nutrient levels and elevated the water conductivity [

23], thereby altering the original oligotrophic condition of the JNR and promoting the growth and reproduction of rotifers [

50].

In this present study, we found that the average density of zooplankton in the lower reaches of the Yellow River is below 15 ind./L, and the average biomass is below 0.1 mg/L, which is significantly lower than the standing current of zooplankton in lakes [

51,

52,

53]. It indicates that the rivers of high sediment content and oligotrophic condition are not ideal habitats for zooplankton, which is consistent with previous studies [

17].

4.3. The Spatial-Temporal Pattern of Zooplankton Community Structure

A lot of ecological factors such as climate and habitat influenced the spatiotemporal dynamics of zooplankton communities [

54]. Among these, climate conditions were the primary drivers of the seasonal succession of zooplankton communities [

55]. In this study, the seasonal succession characteristics of zooplankton community also supported this conclusion. The zooplankton community in Shandong section of the Yellow River could be clearly divided into four seasonal communities: spring community, summer community, autumn community, and winter community. The results of the Monte Carlo test revealed that pH, water temperature (WT), conductivity (Cond), dissolved oxygen (DO), total nitrogen (TN), and total organic carbon (TOC) are important water environmental factors causing significant seasonal differences in the zooplankton community. This is consistent with findings reported in previous studies [

56].

The differences in hydrological characteristics among different river reaches led to distinct spatial-patterns in the zooplankton community [

57]. In spring, summer, and autumn, the zooplankton communities could be clearly distinguished into four spatial communities: XLDR community, DPHR community, JNR community, and HKR community. XLDR community was mainly influenced by the upstream hydraulic engineering projects, which was consistent with the previous findings [

58]. DPHR community was mainly influenced by the input of nutrients and organic matter from the lake water [

59]. The JNR community was mainly influenced by the discharge of urban domestic sewage [

37]. The HKR community was primarily affected by the unique brackish water estuarine environment [

60]. In winter, the changes caused by spatial differences were overshadowed by climatic factors [

18]. WT became the dominant factor influencing the zooplankton communities structure [

52]. There were no significant differences in the zooplankton communities among XLDR, DPHR and JNR. However, the zooplankton community in HKR remains unique due to the influence of brackish water convergence, allowing it to form a distinct community on its own.

4.4. Zooplankton Community Stability

The balance theory of community stability suggests that species interact with each other through mutual restraint, leading to stability characteristics within the community. In a stable state, the species composition of the community remains relatively unchanged. Previous studies pointed out that the richness and diversity of zooplankton were essential conditions directly influencing the stability of zooplankton communities [

61]. The results of this study were consistent with this. In summer, the species richness of zooplankton was highest, and the interactions among species were more complex, resulting in the highest stability of zooplankton communities. In contrast, the stability of zooplankton communities was lowest in winter. Due to the influence of urban wastewater discharge, the zooplankton community structure tended to become simplified [

62]. In addition, the overuse of antibiotics, which entered rivers through urban wastewater, harmed zooplankton growth, development, and reproduction by inhibiting their feeding efficiency and digestive enzyme activity [

63,

64]. The results of this study were consistent with this, as the stability of the zooplankton community in JNR was significantly lower than in other reaches. The stability of the zooplankton community in XLDR was significantly higher than in the other three reaches. This was due to the more than 20 years of operation of the Xiaolangdi Hydraulic Project, during which researchers effectively utilized the self-regulating capacity of the river ecosystem, achieving continuous environmental improvement and the goal of sustainable development in XLDR [

65].

References

- Duan, M.W.; Qiu, Z.Q.; Li, R.R.; Li, K.Y.; Yu, S.J.; Liu, D. Monitoring Suspended Sediment Transport in the Lower Yellow River using Landsat Observations. Remote Sensing. 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentim, H.I.L.; Feio, M.J.; Almeida, S.F.P. Fluvial protected areas as a strategy to preserve riverine ecosystems—a review. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2024, 33, 439–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.N.; Zeng, J.J.; Wu, X.; Qu, J.S.; Li, X.M.; Zhang, J.; Han, J.Y. Review on Eco-Environment Research in the Yellow River Basin: A Bibliometric Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022, 19, 11986–11986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.S.; Xu, B.; Wei, K.J.; Zhu, X.Y.; Xu, J. Phytoplankton community structure and its relation to environmental conditions in the middle. Anning River, China. Chinese Journal of Ecology. 2022, 39, 3332–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.M.; Han, B.; Zhao, G.L.; Liang, S.; Jing, Y.C.; Jia, J.; Zhao, L.D. Analysis of the Characteristics of Water Ecological Environment Changes in the Yellow River Basin. People's Yellow River. 2024, 09, 112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, Y.; Liu, X.Y. Coupling driving factors of eco-environmental protection and high-quality development in the Yellow River Basin. Frontiers in Environmental Science. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.M.; Bian, Y.L.; Lin, D. Analysis of the Causes of Ice Disasters and Research on Defense Measures in the Ning-Meng River Section of the Yellow River. People's Yellow River. 2024, 46, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, N.; Zhou, H. Analysis of Ice Conditions in the Ordos Section of the Yellow River over the Past Decade. China Flood and Drought Management. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.Q. Cultural Connotations, Spatial Distribution, and General Characteristics of the Yellow River Basin. Water Economics. 2024, 42: 87-93.

- Song, J.; Hou, C.; Liu, Q.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Yi, Y. Spatial and Temporal Variations in the Plankton Community Due to Water and Sediment Regulation in the Lower Reaches of the Yellow River. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2020, prepublish. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S. Emergy-Based Evaluation of Xiaolangdi Reservoir’s Impact on the Ecosystem Health and Services of the Lower Yellow River. Sustainability. 2024, 20, 8857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.H.; Song, J.J.; Ren, Y.P.; Zhan, D.M.; Liu, T.; Liu, K.K. . Xu, B.D. Spatio-temporal Patterns of Zooplankton Community in the Yellow River Estuary: Effects of Seasonal Variability and Water-Sediment Regulation. Marine Environmental Research. 2023, 189, 106060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.T.; Yan, M.T.; Chen, X.F.; Wang, X.K.; Gong, H.; Wang, W.J.; Wang, J. Bioavailability and Toxicity of Microplastics to Zooplankton. Gondwana Research, 2022, 120-126. [CrossRef]

- Pardianto, D.K.; Lee, B.R.; Choi, K.H.; Park, W. Seasonal Changes of Zooplankton Community around Dokdo in the East Sea. Journal of Environmental Biology, 2019, 40, 884–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giering, S.L.C.; Wells, S.R.; Mayers, K.M.J.; Schuster, H.; Cornwell, L.; Fileman, E.S.; Atkinson, A.; Cook, K.B.; Preece, C.; Mayor, D.J. Seasonal Variation of Zooplankton Community Structure and Trophic Position in the Celtic Sea: A Stable Isotope and Biovolume Spectrum Approach. Progress in Oceanography, 2019, 177, 101943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.T.; Yan, M.T.; Chen, X.F.; Wang, X.K.; Gong, H.; Wang, W.J.; Wang, J. Bioavailability and Toxicity of Microplastics to Zooplankton. Gondwana Research, 2022, 120-126. [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.F.; Kong, F.H.; Wang, Y.R.; Song, J.X.; Cao, Y.L.; Jiang, X.H. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Zooplankton Community Structure and Their Correlation with Environmental Factors in the Beiluo River Basin. Journal of Dalian Ocean University. 2021, 05, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.X.; Zhang, P.C.; Yang, Y.Y.; Li, F.; Li, S.W.; Xu, B.Q. . Wang, Y.H. Characteristics of Zooplankton Community Structure in the Yellow River Estuary during the 2020 Water and Sediment Regulation Project. Technology & Engineering. 2022, 21, 9061–9070. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, T.; Li, Y.T.; Zuo, M.; Cheng, Z.L.; Wang, J.; Wang, A.D. Seasonal Variations in the Structure of Planktonic Larval Communities in the Vicinity of the Yellow River Estuary. Acta Oceanologica Sinica. 2022, 04, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.; Li, M.; Yin, X.W.; Bai, H.F. Zooplankton Diversity and Water Quality Assessment in the Dawen River Wetland, Jinan. Henan Fisheries. 2024, 02, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.K.; Li, H.W.; Song, X.Y.; Sun, W.Y. Dynamic Monitoring of Surface Water Bodies and Their Influencing Factors in the Yellow River Basin. Remote Sensing. 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Li, R. X.; Li, C.H. Sustainability of Water Resources in Shandong Province Based on a System Dynamics Model of Water–Economy–Society for the Lower Yellow River. Sustainability. 2022, 14, 3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.B.; Yan, T.T.; Shi, S.X.; Zhao, W.J.; Ke, S.H.; Zhang, F.S. Trade-Off and Coordination between Development and Ecological Protection of Urban Agglomerations along Rivers: A Case Study of Urban Agglomerations in the Shandong Section of the Lower Yellow River. Land. 2024, 13, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, Y.J.; Li, H.D. Hydrochemical Characteristics and Controlling Factors of the Yellow River in Shandong Section. People's Yellow River. 2019, 40, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.C.; Cai, J.; Xie, M.T.; Liu, X.P.; Tian, J.P.; He, W.J.; Zhang, D.J. Assessment of Ecosystem Service Values in the National Wetland Park of the Lower Yellow River in Shandong. Wetland Science. 2024, 05, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.S.; Huang, X.F. Freshwater Plankton Research Methods [M]. Beijing: Science Press. 1991.

- Wang, J.J. Fauna of Freshwater Rotifers in China [M]. Beijing: Science Press. 1961.

- 28. Crustacean Research Group, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Fauna Sinica: Arthropoda: Crustacea: Freshwater Copepoda [M]. Beijing: Science Press. 1979.

- Jiang, X.Z.; Du, N.S. Fauna Sinica: Arthropoda: Crustacea: Freshwater Cladocera [M]. Beijing: Science Press. 1979.

- Zhang, Y.Z.; Zhang, L.L.; Yin, R.; Luan, H.N.; Liu, Z.J.; Chen, J.; Jiang, R.J. Spatial Niches of Dominant Zooplankton Species in Yueqing Bay, Zhejiang Province. The Journal of Applied Ecology. 2021, 1, 342–348. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Q.M.; Li, C.C. Studies on the Composition and Seasonal Variations of Planktonic Copepoda in Poyang Lake. Jiangxi Science. 1998, 16, 180–187. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, C.M.; Dong, G.C.; Liu, C.; Li, X.Q.; Zhu, S.W.; Ke, H. Investigation and Analysis of Plankton Community Characteristics in the Shandong Section of the Yellow River. Journal of Shandong Agricultural University (Natural Science Edition). 2016, 05, 668–673. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J. (2024-12-09). Creating a New Situation for Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development in the Yellow River Basin. China Fisheries News, p. A04.

- Hui, J.; Jie, Z.L.; He, H.Z.; Li, F.T. Ecological Characteristics and Spatiotemporal Distribution of Plankton in the Henan Section of the Yellow River. Hebei Fisheries. 2018, 05, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, H.; Lin, F.; Wu, Y.P.; Tian, B.; Cai, Z.Y.; Wu, Y.P. . Zhou, Z.G. Analysis of the Community Structure Characteristics and Environmental Correlation of Zooplankton in the Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River at Yichang. Heilongjiang Fisheries. 2022, 05, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, S.W.; Yang, Y.Y.; Xu, B.C.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, M.M.; Li, F.; Yu, H.M. How the Water-Sediment Regulation Scheme in the Yellow River Affected the Estuary Ecosystem in the Last 10 Years? . Science of the Total Environment. 2024, 172002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natthida, J.; Sameer, M.P.; Supiyanit, M. Biodiversity and Species-Environment Relationships of Freshwater Zooplankton in Tropical Urban Ponds. Urban Ecosystems. 2023, 27, 827–840. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Xi, Y.L. Research Progress on Interspecific Competition of Brachionus plicatilis. Ecological Journal. 2019, 10, 3177–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.H.; Jiang, W.L.; Zhang, D.P.; Li, S.F.; Dong, B.; Lv, Z.B.; Ren, Z.H. Study on the Ecological Niche of Dominant Zooplankton Species and Its Correlation with Environmental Factors in Spring and Autumn in the Coastal Area of Laizhou. Marine Fisheries, 2024, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Dong, A.; Yu, X.F.; Yin, Y.; Zhao, K. Seasonal variation characteristics and the factors affecting plankton community structure in the Yitong River, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022, 24, 17030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.M.; He, P.M.; Liu, W.; Liu, J.L.; Chen, S.W.; Han, Z.; Wu, M.Q. Seasonal Variations and the Relationship with Environmental Factors of Zooplankton in Urban Rivers of Shanghai. Journal of Aquatic Ecology. 2022, 05, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.J.; Yang, Y.L.; Ni, L.Y.; Chen, Y.S.; Wen, Z.H.; Su, H.J.; Guo, L.G. Temperature, nutrients, and planktivorous fish predation interact to drive crustacean zooplankton in a large plateau lake, southwest China. Aquatic Sciences. 2022, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Q.; Zhao, K.; Cao, Y.; Wu, B.; Pang, W. T.; You, Q.M.; Wang, Q.X. The community structure of zooplankton and its relationship with environmental factors in Poyang Lake. Acta Ecologica Sinica. 2020, 40, 6644–6658. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.Q.; Pan, B. Z.; Yang, Z. J.; Hu, E.; Zhang, X.; Li, G.; Hu, J.X. Characteristics of the plankton community and interspecific relationships of dominant species in the Jing River Basin. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2024, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, D.; Xia, J.; Song, J. X.; Chang, J.B.; Wu, Q.; Cheng, D.N.; Ren, Y.X. Diversity of plankton and key species ecological niche characteristics in the Wei River based on eDNA technology. Environmental Science. 2021, 42, 4708–4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liang, J.; Kong, D.F.; Chen, T. Survey and evaluation of aquatic biota communities in typical mountain rivers of the Yellow River Basin: A case study of Dayu River. Environmental Science and Technology. 2024, 39, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, L.L.; Gao, L.M.; Qiu, Y.H.; Zhang, Z.; Ge, J.; Zhao, X.L. Levels of nutrient enrichment determine the emergence of zooplankton from resting egg banks. Hydrobiologia. 2023, 1259–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandlund, O.T. The drift of zooplankton and micro benthos in the river Strandaelva, westem Norwway. Hydrobiologia. 1982, 94, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, S.C.; Chen, Z.W.; Yan, R.W.; Li, D.Y. Technical study on draining water from Dongping Lake to the Nan Si Lake. Shandong Water Science and Technology, 1997, 4, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kippen, N.K.; Zhang, C.; Mleczek, M.; Špoljar, M. Rotifers as indicators of trophic state in small water bodies with different catchments (field vs. forest). Hydrobiologia, 2024, prepublish, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.M.; Cao, X.Y.; Cui, L.Y.; Lv, Q.; Chen, T.T. The Influence of Human Interference on Zooplankton and Fungal Diversity in Poyang Lake Watershed in China. Diversity. 2022, 12, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Peng, K.; Zhang, Q.J.; Cai, Y.J.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Gong, Z.J.; Xiang, X.L. Spatio-temporal distribution characteristics and driving factors of zooplankton in Hongze Lake. Environmental Science. 202, 40, 3753–3762. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H.; Zhang, X.W. eDNA metabarcoding in zooplankton improves the ecological status assessment of aquatic ecosystems. Environment International. 2020, 105230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lígia, A.P.; Carlos, C.; Filipe, M.; Alexandra, G.M.; Manuel, J.R.; Miguel, P. Climate forcing on estuarine zooplanktonic production. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2023, 115287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.Y.; Zhao, L.L.; Jia, X.; Hu, Y.F.; Liu, S.Z.; Liu, Q.; Song, J. Seasonal differences and functional group characteristics of plankton community structure in Cetian Reservoir, Shanxi Province. Journal of Dalian Ocean University. 2024, 45, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.X.; Li, H.Y.; Zhou, L.; Shi, J.H.; Nie, Y.; Zhao, F.; Li, S.Y. Structural characteristics of zooplankton communities in Hongze Lake driven by water environmental factors from 2016 to 2020. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 2023, 195, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Palit, D.; Hazra, N. Spatial pattern analysis of zooplankton and surface water of pit lakes (Raniganj coal field, India). Water Science. 2023, 37, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Yi, Y. J.; Hou, C. Y.; Yang, Y. F. The impact of water regulation and sediment control at the Xiaolangdi Reservoir on downstream river plankton. People's Yellow River. 2019, 41, 38–43+75.

- Chen, X.L. Study on the spatiotemporal dynamics and driving factors of plankton community in the regulatory lakes of the Eastern Route of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project [D]. Qufu Normal University. 2024. https://doi.org/. [CrossRef]

- Barros, A.; Hartman, R.; Bashevkin, S.M.; Burdi, C.E. Years of drought and salt: Decreasing flows determine the distribution of zooplankton resources in the San Francisco Estuary. San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science. 2024, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.J.; Xu, Q.J.; Dong, J.; Pang, Y.; Tao, Y.R. Ecological health assessment of lakes based on the coordination of "three waters": A case study of Li Lake in Tai Lake. Journal of Environmental Engineering Technology. 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, M.R.; Ding, Y.F.; Zhang, R.; Liu, Y.; Kan, D.Q.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, J.X. Community structure of metameric zooplankton and evaluation of water quality and trophic state in Jinshuitan Reservoir. Resources and Environment in the Yangtze River Basin. 2023, 32, 354–364. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zou, H.Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, X.W. Seasonal distribution and dynamic evolution of antibiotics and evaluation of their resistance selection potential and ecotoxicological risk at a wastewater treatment plant in Jinan, China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International. 2023, 30, 44505–44517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Dai, S.; Xie, Q.M. Preliminary study on the toxic effects of two quinolone antibiotics on Daphnia magna. Chinese Journal of Antibiotics. 2024, 49, 832–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Dang, Y.C., Duan, W.S. Overview of the ecological and environmental impact of the Xiaolangdi Water Conservancy Hub Project on the Yellow River [C]. Proceedings of the 2021 Annual Conference of the Chinese Water Resources Association, 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).