Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. In Vitro Experiment

2.4. Determination of Rumen Fermentation Parameters

2.5. Determination of Rumen Microbial Diversity

2.6. Determination of Rumen Metabolites

2.7. Data Analysis

2.7.1. Rumen Fermentation Parameters

2.7.2. Rumen Microbial Diversity

2.7.3. Rumen Metabolites

3. Results

3.1. Nutritional Digestibility In Vitro

3.2. Rumen Fermentation Parameters

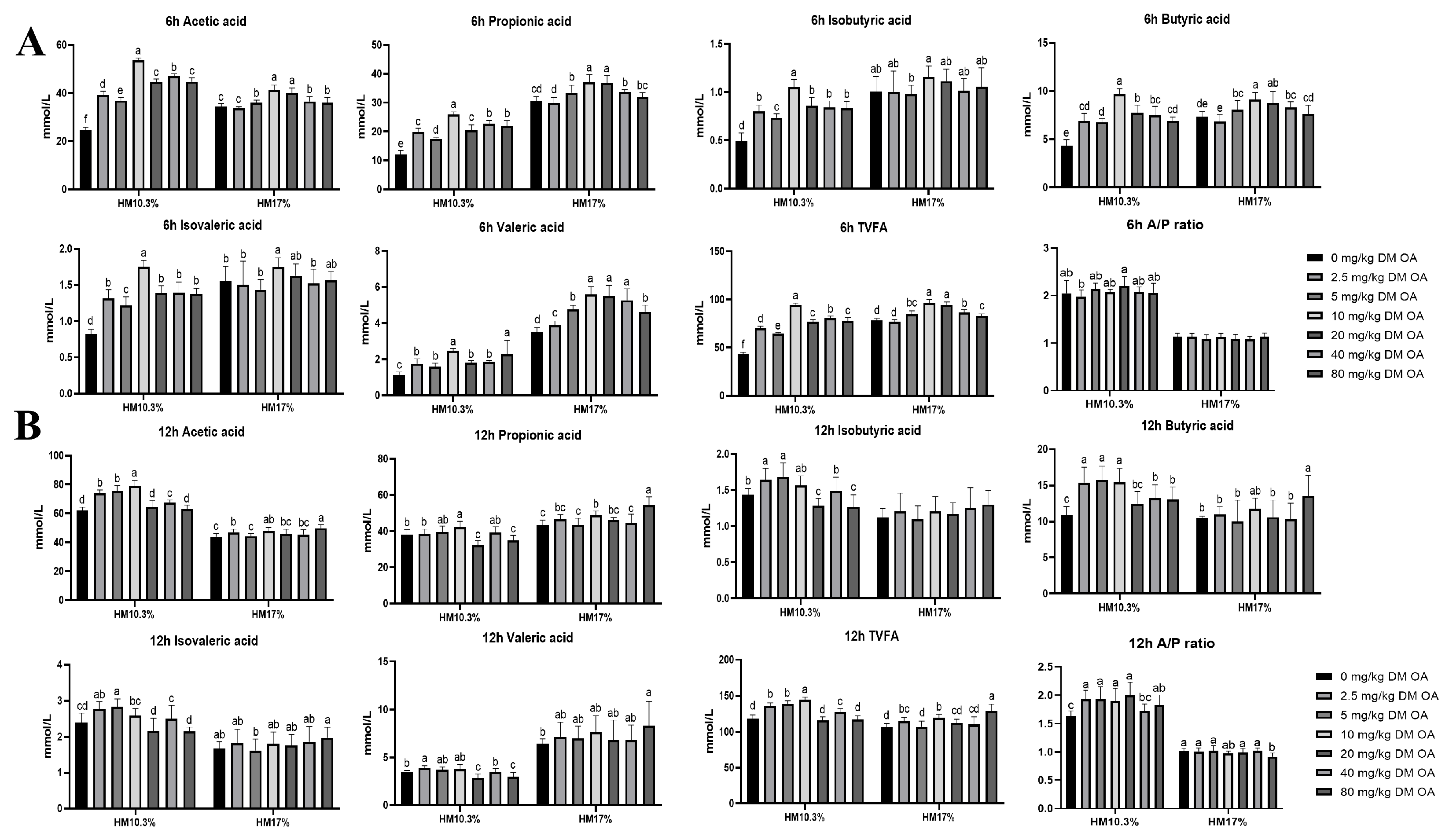

3.3. Microbial Diversity In Vitro

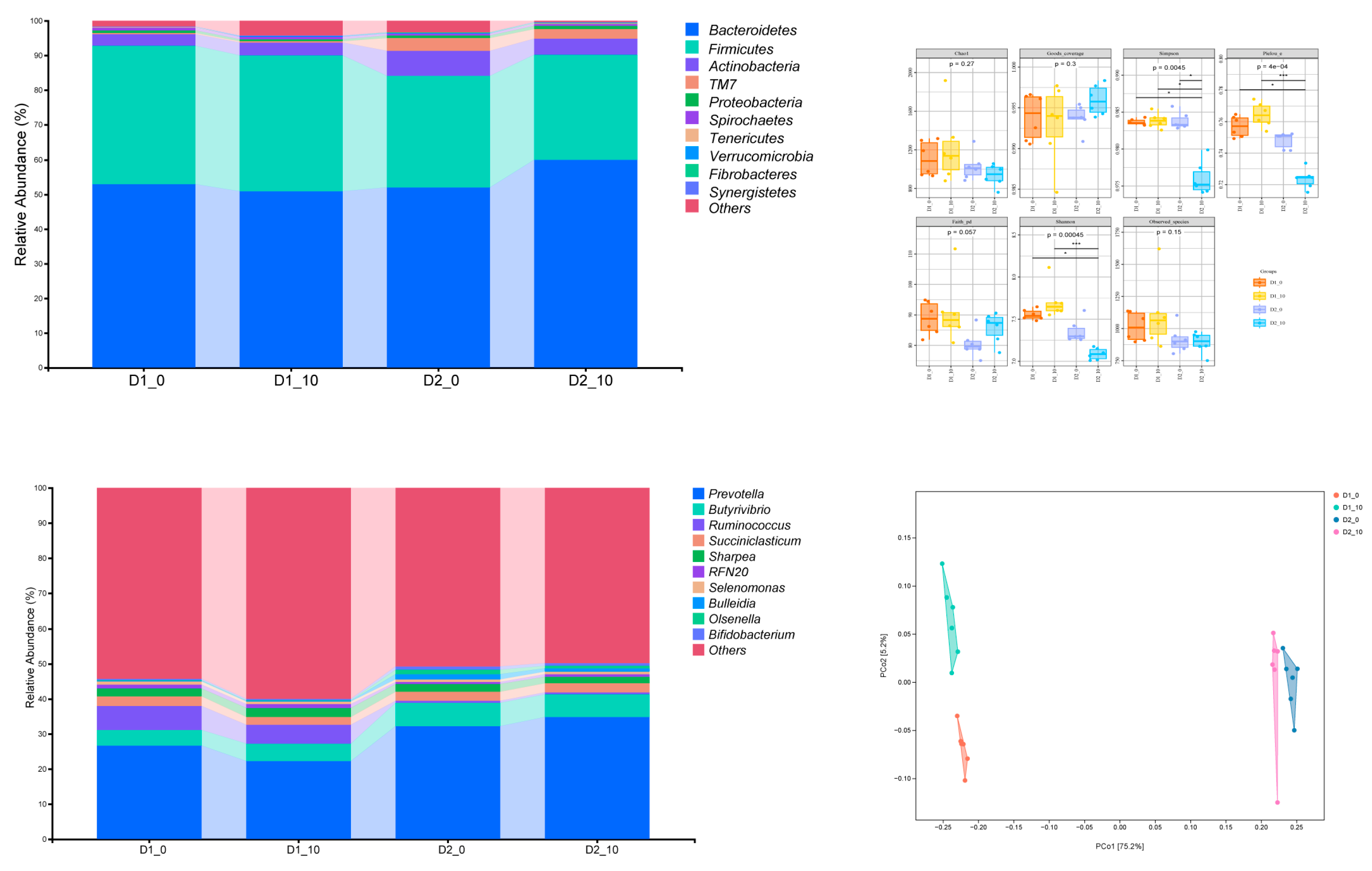

3.3.1. Ruminal Bacterial Alpha Diversity Indexes

3.3.2. Ruminal Bacterial Phylum Composition

3.3.3. Rumen Bacterial Genus Composition

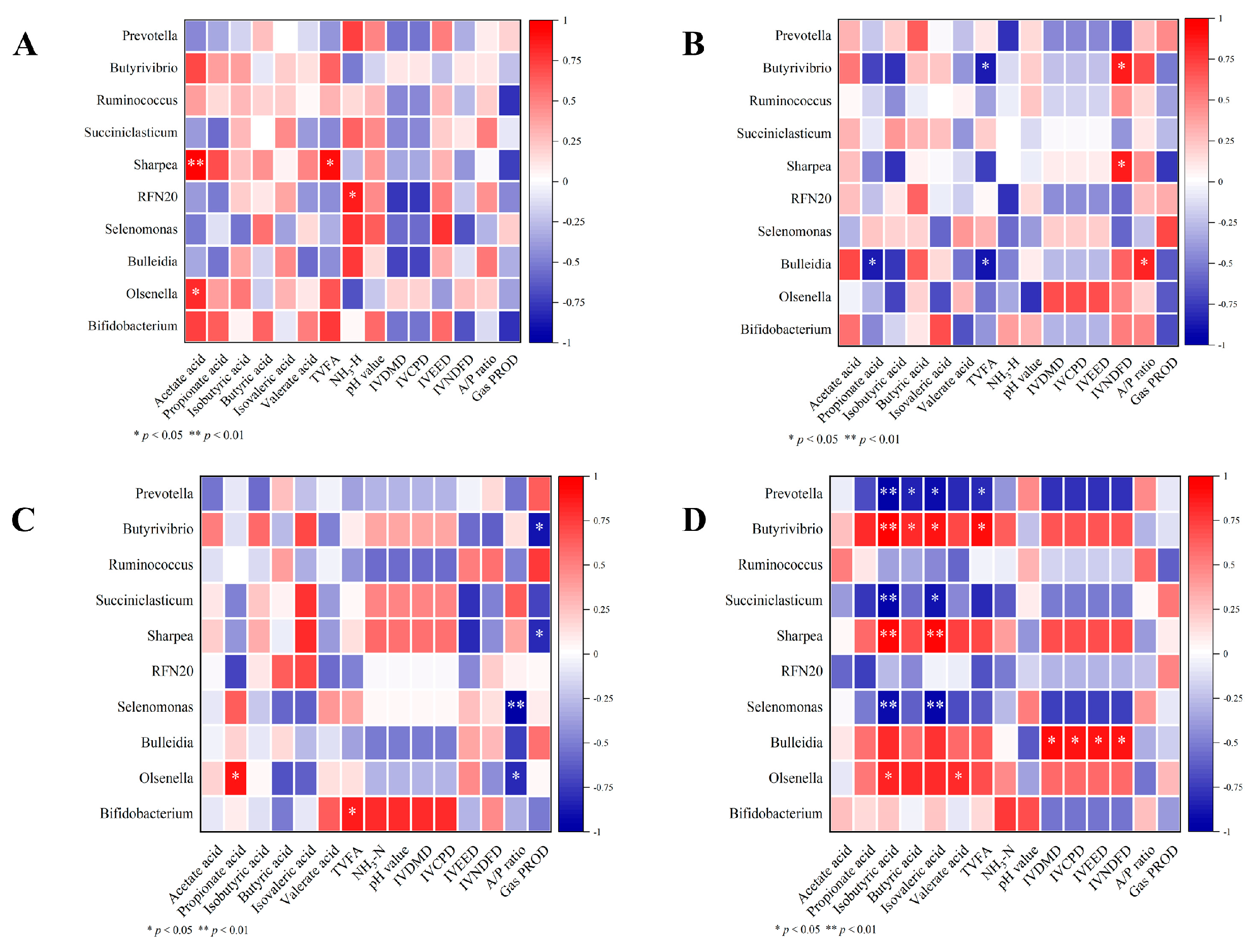

3.4. The Relationship Between Rumen Fermentation Parameters and Bacterial Genus Composition

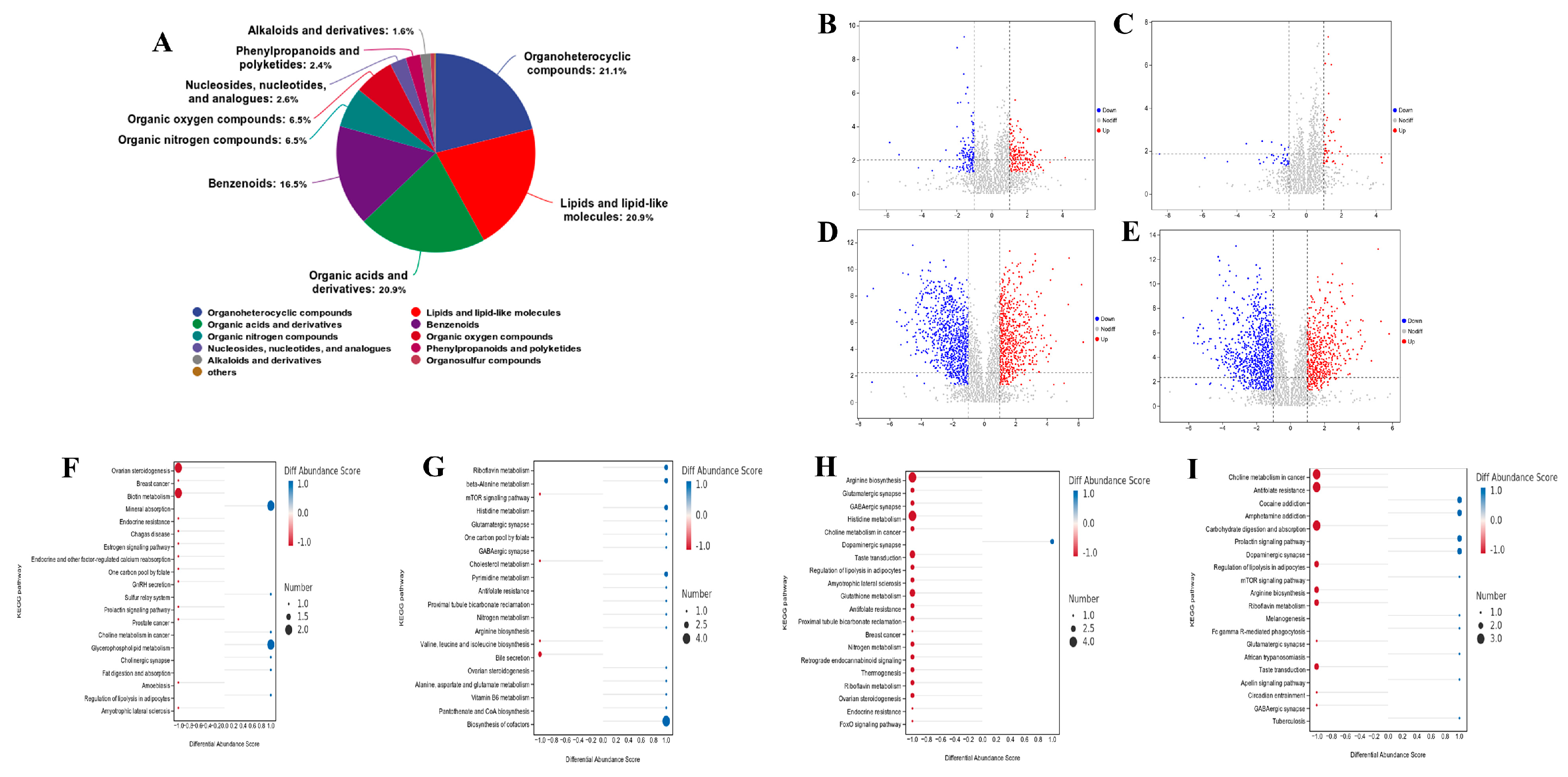

3.5. Rumen Metabolites In Vitro

3.6. Rumen Metabolic Pathway

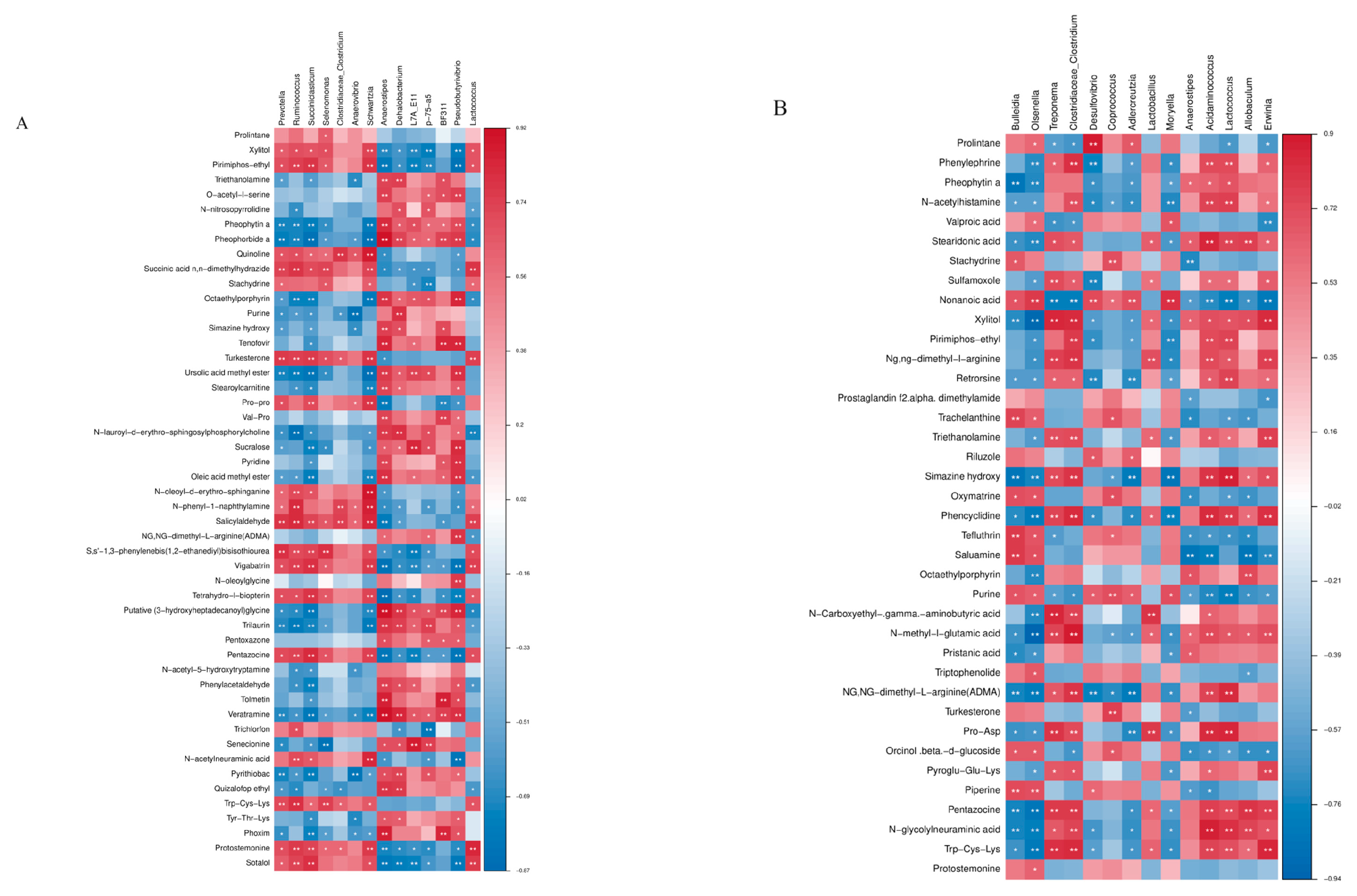

3.7. The Correlation Between Rumen Metabolites and Rumen Bacterial

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HM | Hemicellulose |

| OA | Oxalic acid |

| VFA | Volatile fatty acid |

| YC | Yeast culture |

| IVDMD | Dry matter digestibility |

| IVCPD | Crude protein digestibility |

| IVEED | Crude fat digestibility |

| IVNDFD | Neutral detergent fiber digestibility |

References

- Weimer, P.J. Degradation of Cellulose and Hemicellulose by Ruminal Microorganisms. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plata, F.P.; Bárcena-Gama, J.R. Effect of a Yeast Culture (Saccharomyces Cerevisiae) on Neutral Detergent Fiber Digestion in Steers Fed Oat Straw Based Diets. Animal Feed Science and Technology 1994, 49, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, F.; Estoppey, A.; House, G.L.; Lohberger, A.; Bindschedler, S.; Chain, P.S.; Junier, P. Oxalic Acid, a Molecule at the Crossroads of Bacterial-Fungal Interactions. Advances in applied microbiology 2019, 106, 49–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, W.; Li, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, W.; Xin, L.; Han, Z.; Wang, L.; Aschalew, N.D.; et al. Mechanistic Insights into Rumen Function Promotion through Yeast Culture (Saccharomyces Cerevisiae) Metabolites Using in Vitro and in Vivo Models. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1407024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duraiswamy, A.; Sneha A, N.M.; Jebakani K, S.; Selvaraj, S.; Pramitha J, L.; Selvaraj, R.; Petchiammal K, I.; Kather Sheriff, S.; Thinakaran, J.; Rathinamoorthy, S.; et al. Genetic Manipulation of Anti-Nutritional Factors in Major Crops for a Sustainable Diet in Future. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 1070398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Abdullah, R.B.; Wan Khadijah, W.E. A Review of Oxalate Poisoning in Domestic Animals: Tolerance and Performance Aspects. Journal of animal physiology and animal nutrition 2013, 97, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.N.; Sun, Y.R.; Tang, Y.M.; Xie, X.L.; Li, Q.Y.; Mou, F.Z.; Sun, H.X. Effect of High Oxalic Acid Intake on Growth Performance and Digestion, Blood Parameters, Rumen Fermentation and Microbial Community in Sheep. Small Ruminant Research 2024, 237, 107324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.F.; Butcher, J.E. Halogeton Poisoning of Sheep: Effect of High Level Oxalate Intake. Journal of Animal Science 1972, 35, 1233–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frutos, P.; Duncan, A.J.; Kyriazakis, I.; Gordon, I.J. Learned Aversion towards Oxalic Acid-Containing Foods by Goats: Does Rumen Adaptation to Oxalic Acid Influence Diet Choice? Journal of Chemical Ecology 1998, 24, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, A.J.; Frutos, P.; Young, S.A. Rates of Oxalic Acid Degradation in the Rumen of Sheep and Goats in Response to Different Levels of Oxalic Acid Administration. Animal Science 1997, 65, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kh, M. Estimation of the Energetic Feed Value Obtained from Chemical Analysis and in Vitro Gas Production Using Rumen Fluid. Anim Res Dev 1988, 28, 7–55. [Google Scholar]

- Aschalew, N.D.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Xia, Y.; Yin, G.; Dong, J.; Zhen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, T.; Sun, Z.; et al. Effects of Yeast Culture and Oxalic Acid Supplementation on in Vitro Nutrient Disappearance, Rumen Fermentation, and Bacterial Community Composition. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, A.L.; Marbach, E.P. Modified Reagents for Determination of Urea and Ammonia. Clinical chemistry 1962, 8, 130–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Urriola, P.E.; Shurson, G.C. Use of in Vitro Dry Matter Digestibility and Gas Production to Predict Apparent Total Tract Digestibility of Total Dietary Fiber for Growing Pigs. Journal of animal science 2017, 95, 5474–5484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFeo, M.E.; Shampoe, K.V.; Carvalho, P.H.; Silva, F.A.; Felix, T.L. In Vitro and in Situ Techniques Yield Different Estimates of Ruminal Disappearance of Barley. Translational Animal Science 2020, 4, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeser, J.P.; Combs, D.K. An Alternative Method to Assess 24-h Ruminal in Vitro Neutral Detergent Fiber Digestibility. Journal of dairy science 2009, 92, 3833–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, A.; Stewart, C.J. Microbiota Analysis Using Sequencing by Synthesis: From Library Preparation to Sequencing. Methods Mol Biol 2020, 2121, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschalew, N.D.; Wang, T.; Qin, G.X.; Zhen, Y.G.; Zhang, X.F.; Chen, X.; Atiba, E.M.; Seidu, A. Effects of Physically Effective Fiber on Rumen and Milk Parameters in Dairy Cows: A Review. Indian Journal of Animal Research 2020, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Plaizier, J.C.; Krause, D.O.; Gozho, G.N.; McBride, B.W. Subacute Ruminal Acidosis in Dairy Cows: The Physiological Causes, Incidence and Consequences. The Veterinary Journal 2008, 176, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belenguer, A.; Bati, M.B.; Hervás, G.; Toral, P.G.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R.; Frutos, P. Impact of Oxalic Acid on Rumen Function and Bacterial Community in Sheep. animal 2013, 7, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, R.; Yang, S.; Deng, J.P.; Tang, S.X.; Tan, Z.L. Effects of Three Methane Mitigation Agents on Parameters of Kinetics of Total and Hydrogen Gas Production, Ruminal Fermentation and Hydrogen Balance Using in Vitro Technique. Anim Sci J 2016, 87, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xia, Y.; Cheng, L.; Qin, G.; Aschalew, N.D.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Q.; et al. Mechanistic Insights into Inositol-Mediated Rumen Function Promotion and Metabolic Alteration Using in Vitro and in Vivo Models. Front Vet Sci 2024, 11, 1359234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.; Liu, H.; Zhao, J.; Gu, X.; Wei, X.; Zhang, X.; Ma, N.; Johnston, L.J.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, W.; et al. Amino Acids Metabolism by Rumen Microorganisms: Nutrition and Ecology Strategies to Reduce Nitrogen Emissions from the inside to the Outside. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 800, 149596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.A.; Reis, S.S.; Costa, D.C. da C.C.; Dos Santos, M.A.; Paulino, R. de S.; Rufino, M. de O.A.; Neto, S.G. Yeast-Fermented Cassava as a Protein Source in Cattle Feed: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trop Anim Health Prod 2023, 55, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, M.E.; Stern, M.D.; Satter, L.D. The Effect of Rumen Ammonia Concentration on Dry Matter Disappearance in Situ. J. Dairy Sci 1979, 62, 76. [Google Scholar]

- Keim, J.P.; Alvarado-Gilis, C.; Arias, R.A.; Gandarillas, M.; Cabanilla, J. Evaluation of Sources of Variation on in Vitro Fermentation Kinetics of Feedstuffs in a Gas Production System. Anim Sci J 2017, 88, 1547–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagpal, R.; Shrivastava, B.; Kumar, N.; Dhewa, T.; Sahay, H. Microbial Feed Additives. Rumen Microbiology: From Evolution to Revolution 2015, 161–175.

- Mahayri, T.M.; Fliegerová, K.O.; Mattiello, S.; Celozzi, S.; Mrázek, J.; Mekadim, C.; Sechovcová, H.; Kvasnová, S.; Atallah, E.; Moniello, G. Host Species Affects Bacterial Evenness, but Not Diversity: Comparison of Fecal Bacteria of Cows and Goats Offered the Same Diet. Animals 2022, 12, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Qin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Ning, X.; Sun, S. Specific Alterations of Gut Microbiota in Patients with Membranous Nephropathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Physiology 2022, 13, 909491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnell, L.J.; Reyes, A.A.; Wolfe, C.A.; Weinroth, M.D.; Metcalf, J.L.; Delmore, R.J.; Belk, K.E.; Morley, P.S.; Engle, T.E. Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes Drive Differing Microbial Diversity and Community Composition Among Micro-Environments in the Bovine Rumen. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 897996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.K.; Zhang, X.X.; Li, F.D.; Li, C.; Li, G.Z.; Zhang, D.Y.; Song, Q.Z.; Li, X.L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, W.M. Characterization of the Rumen Microbiota and Its Relationship with Residual Feed Intake in Sheep. Animal 2021, 15, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strobel, H.J. Pentose Utilization and Transport by the Ruminal Bacterium Prevotella Ruminicola. Arch Microbiol 1993, 159, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S.K.; Lauridsen, C. Alpha-Tocopherol Stereoisomers. Vitam Horm 2007, 76, 281–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, R.; Siddiqi, S.; Siddiqi, S.A. α-Tocopherol Reduces VLDL Secretion through Modulation of Intracellular ER-to-Golgi Transport of VLDL. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2023, 101, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albarracin, S.L.; Baldeon, M.E.; Sangronis, E.; Petruschina, A.C.; Reyes, F.G.R. L-Glutamate: A Key Amino Acid for Senory and Metabolic Functions. Arch Latinoam Nutr 2016, 66, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arshad, U.; Zenobi, M.G.; Tribulo, P.; Staples, C.R.; Santos, J.E.P. Dose-Dependent Effects of Rumen-Protected Choline on Hepatic Metabolism during Induction of Fatty Liver in Dry Pregnant Dairy Cows. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0290562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Chai, Y.; Xu, Y.; Miao, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, Z.; Yu, Q. Glycocholic Acid Aggravates Liver Fibrosis by Promoting the Up-Regulation of Connective Tissue Growth Factor in Hepatocytes. Cell Signal 2023, 101, 110508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Yang, M.R.; Lu, J.-G.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, G.-Y.; Jiang, Z.-H. Amide Derivatives of Ginkgolide B and Their Inhibitory Effects on PAF-Induced Platelet Aggregation. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 22497–22503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| HM10.3% | HM17% | P-value | |||||||||||||||||

| Item(%) | Time(h) | 0 mg/kg | 2.5 mg/kg | 5 mg/kg | 10 mg/kg | 20 mg/kg | 40 mg/kg | 80 mg/kg | 0 mg/kg | 2.5 mg/kg | 5 mg/kg | 10 mg/kg | 20 mg/kg | 40 mg/kg | 80 mg/kg | SEM | HM | OA | HM×OA |

| IVDMD | 6 | 28.29 | 30.90 | 30.07 | 30.59 | 30.24 | 30.03 | 29.24 | 29.84 | 28.87 | 8.99 | 27.94 | 28.24 | 29.56 | 26.59 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.49 | 0.33 |

| 12 | 35.87 | 35.88 | 36.63 | 36.69 | 36.94 | 35.78 | 35.60 | 34.28 | 33.46 | 34.84 | 33.96 | 33.72 | 34.04 | 33.91 | 0.28 | <0.01 | 0.95 | 0.98 | |

| IVCPD | 6 | 23.10c | 30.77a | 29.83ab | 29.41ab | 30.93a | 31.45a | 27.23b | 33.60a | 31.01ab | 31.97a | 31.08ab | 27.22bc | 32.37a | 25.08c | 0.34 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 12 | 38.67b | 38.39b | 38.28b | 43.89a | 40.72ab | 40.70ab | 45.08a | 40.47a | 36.75b | 40.44a | 37.72ab | 35.36b | 37.01b | 35.74b | 0.34 | <0.01 | 0.01 | <0.01 | |

| IVEED | 6 | 18.63cd | 27.37a | 19.24c | 18.08d | 20.98b | 28.10a | 16.81e | 27.89c | 30.69b | 31.57ab | 23.36d | 21.59e | 30.87b | 31.96a | 0.47 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 12 | 29.05a | 23.25c | 23.65c | 25.63b | 26.50b | 18.50d | 26.43b | 29.10c | 31.37b | 16.84f | 37.82a | 29.33c | 24.86e | 27.48d | 0.44 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| IVNDFD | 6 | 12.24c | 15.43a | 15.31a | 13.42b | 12.62bc | 12.67bc | 14.53a | 7.53ab | 8.51a | 6.05ab | 6.47ab | 7.14ab | 7.99ab | 4.79b | 0.36 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 12 | 21.53d | 22.31c | 22.92c | 23.59b | 24.62a | 21.07d | 20.30e | 12.10bc | 12.59bc | 16.74a | 13.41bc | 11.25c | 11.09c | 14.71ab | 0.45 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| HM10.3% | HM17% | P-value | |||||||||||||||||

| Item | Time (h) | 0 mg/kg | 2.5 mg/kg | 5 mg/kg | 10 mg/kg | 20 mg/kg | 40 mg/kg | 80 mg/kg | 0 mg/kg | 2.5 mg/kg | 5 mg/kg | 10 mg/kg | 20 mg/kg | 40 mg/kg | 80 mg/kg | SEM | HM | OA | HM×OA |

| NH3-N (mg/dL) |

6 | 17.97d | 19.77abc | 21.08a | 20.32ab | 18.50cd | 18.91bcd | 20.20ab | 22.06ab | 20.47c | 19.60c | 23.46a | 22.52a | 19.96c | 20.94bc | 0.18 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 12 | 28.70a | 26.05b | 28.23a | 22.87c | 23.12c | 24.30c | 23.80c | 25.04 | 25.85 | 25.33 | 25.38 | 25.09 | 25.63 | 25.63 | 0.19 | 0.672 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| Gas PROD (mL) |

6 | 50.94cd | 57.26bc | 61.34b | 59.95b | 46.76d | 135.12a | 51.8cd | 65.2d | 67.45d | 64.45d | 79.36c | 101.25b | 129.86a | 108.92b | 4.48 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 12 | 100.05d | 153.35b | 170.94a | 149.92b | 113.46c | 108.31cd | 118.39c | 85.04c | 152.92a | 113.24b | 136.33a | 112.06b | 93.73c | 145.5a | 4.04 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| pH value |

6 | 7.10a | 7.07ab | 7.06ab | 7.04ab | 7.04ab | 7.01b | 7.01b | 6.95 | 6.96 | 6.95 | 6.95 | 6.90 | 6.91 | 6.95 | 0.02 | <0.01 | 0.89 | 0.99 |

| 12 | 6.88 | 6.83 | 6.80 | 6.80 | 6.81 | 6.81 | 6.77 | 6.73 | 6.75 | 6.71 | 6.69 | 6.71 | 6.72 | 6.69 | 0.02 | <0.01 | 0.94 | 0.99 | |

| TVFA (mmol/L) |

6 | 43.45f | 69.77d | 64.53e | 94.61a | 76.85c | 80.75b | 78.03c | 78.38d | 76.79d | 84.81bc | 96.19a | 94.00a | 86.36b | 82.78c | 1.14 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| 12 | 118.36d | 135.83b | 138.92b | 144.61a | 115.59d | 127.38c | 117.32d | 107.10d | 114.62bc | 107.33d | 119.02b | 112.33cd | 110.32cd | 29.06a | 1.09 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).