Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

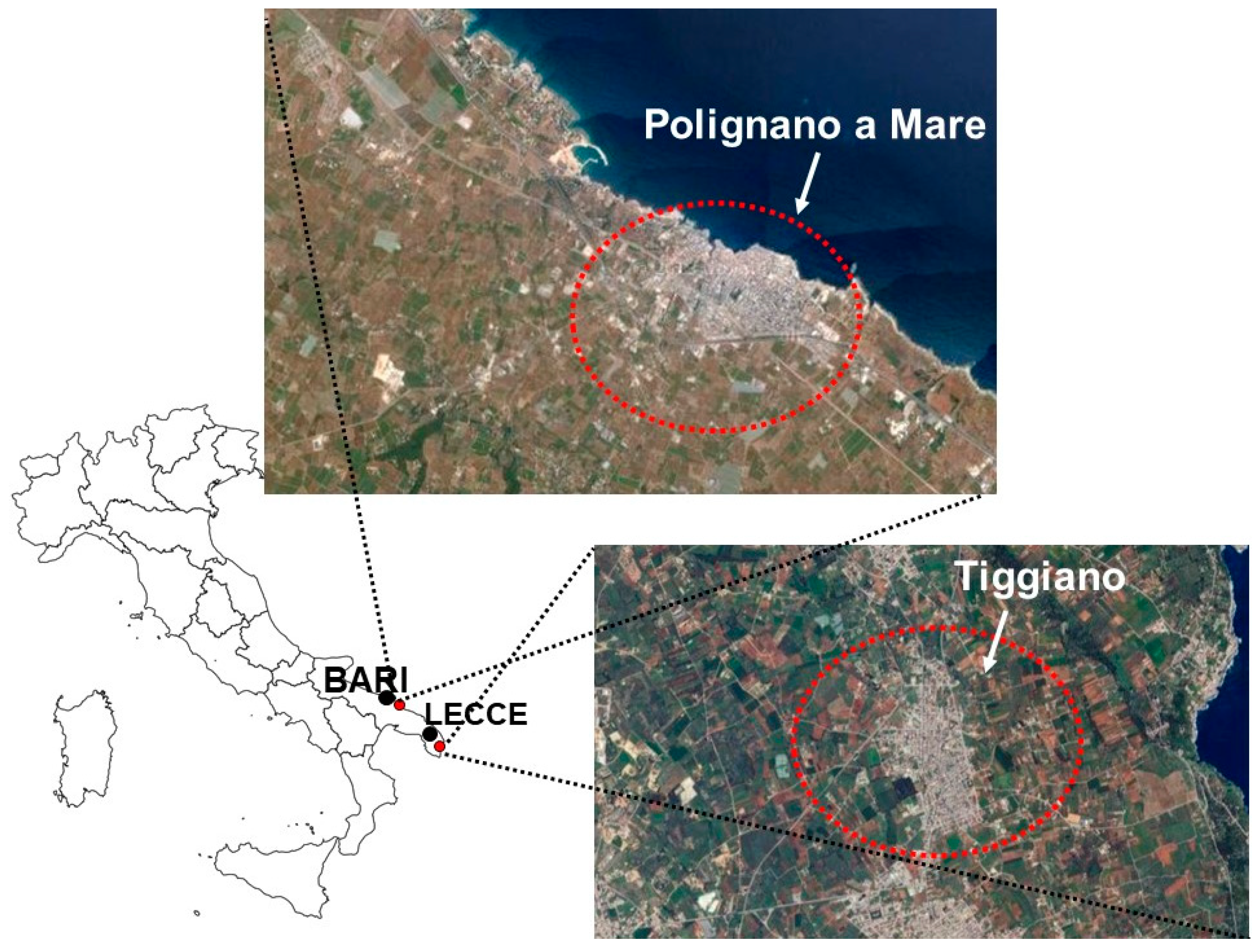

2.1. Cropping Details

2.2. Morphological Characterization

2.3. Umbels and Seeds Traits

2.4. Germination Assays

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Plant Morphological Traits

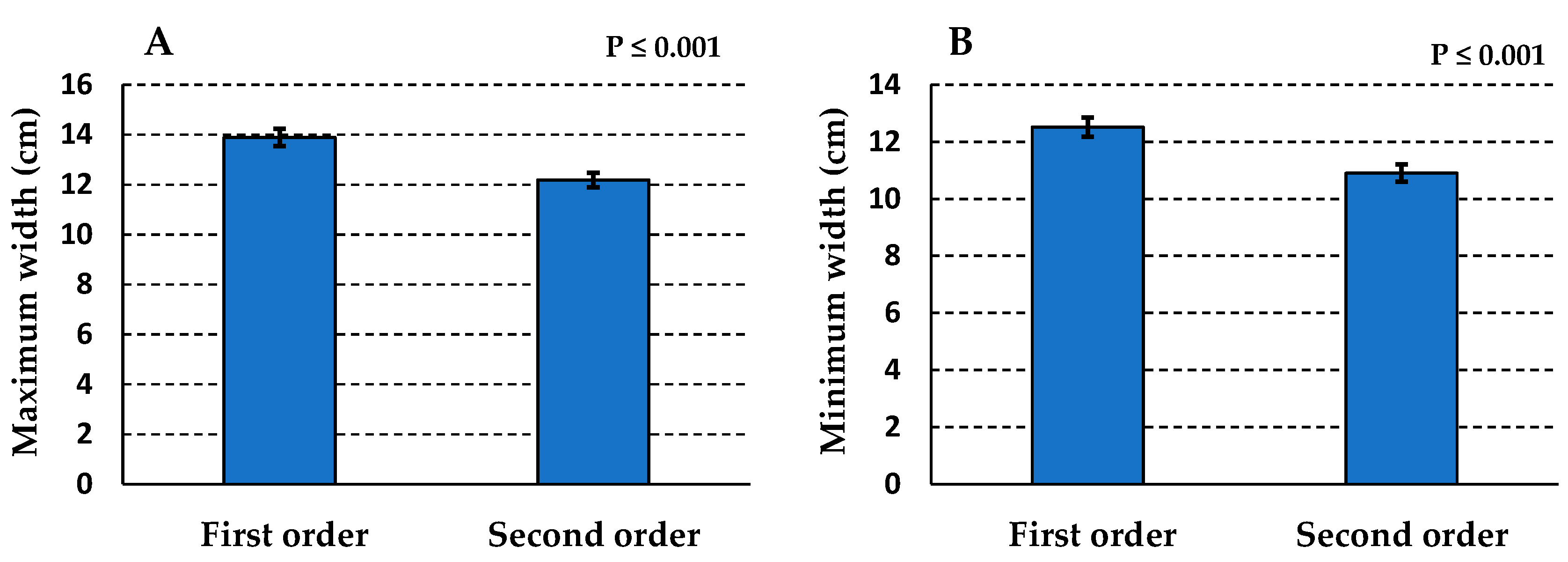

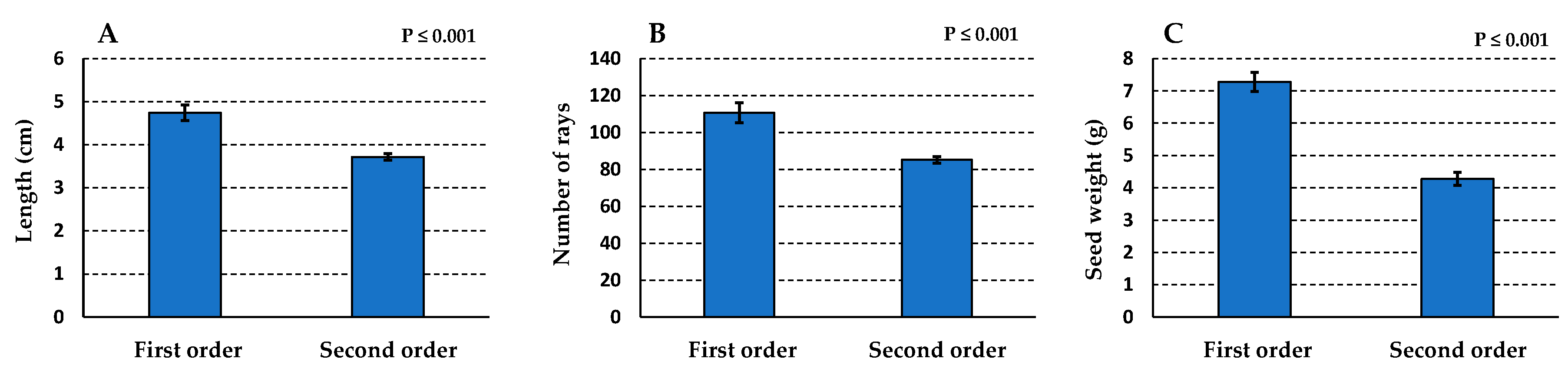

3.2. Umbel and Seed Traits

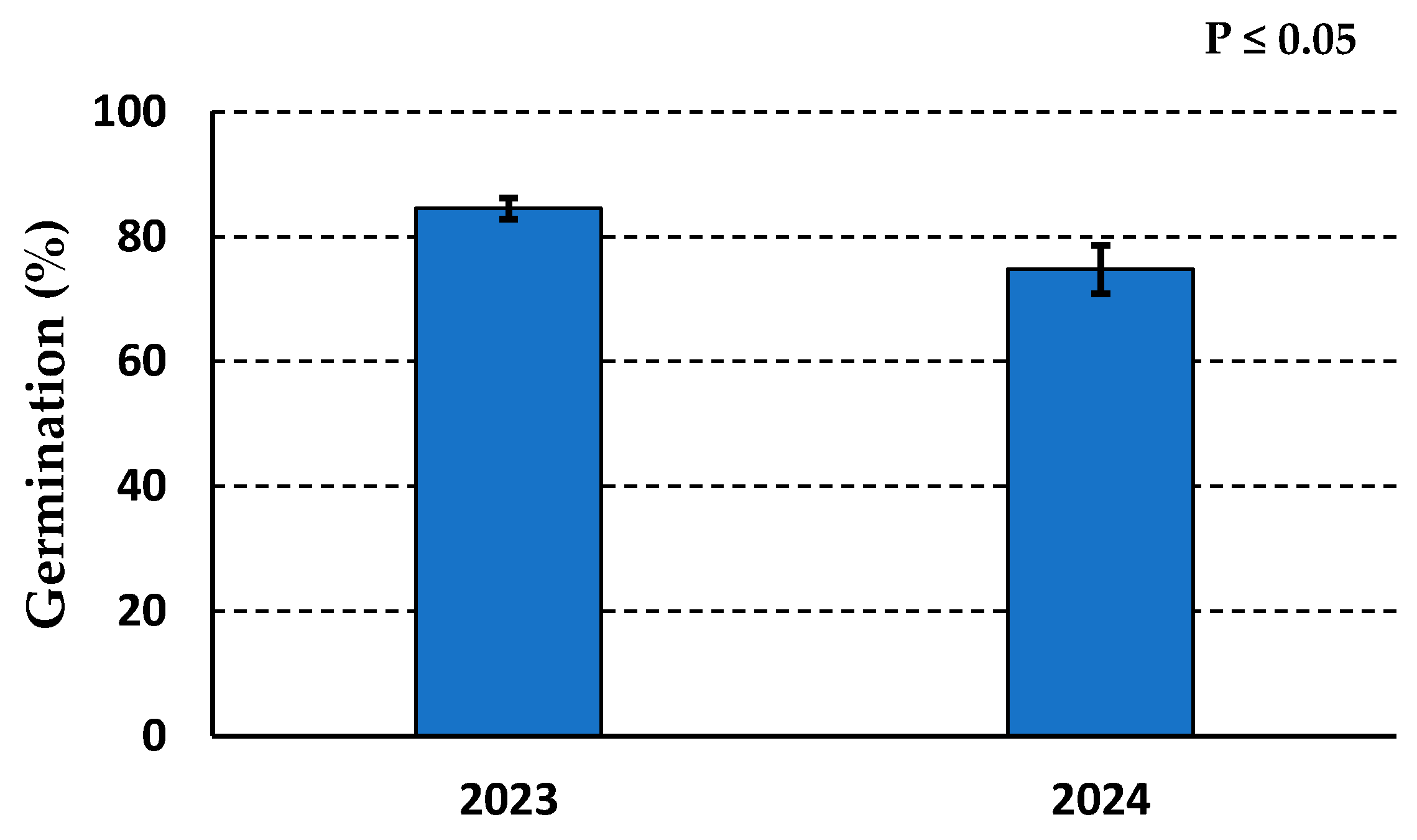

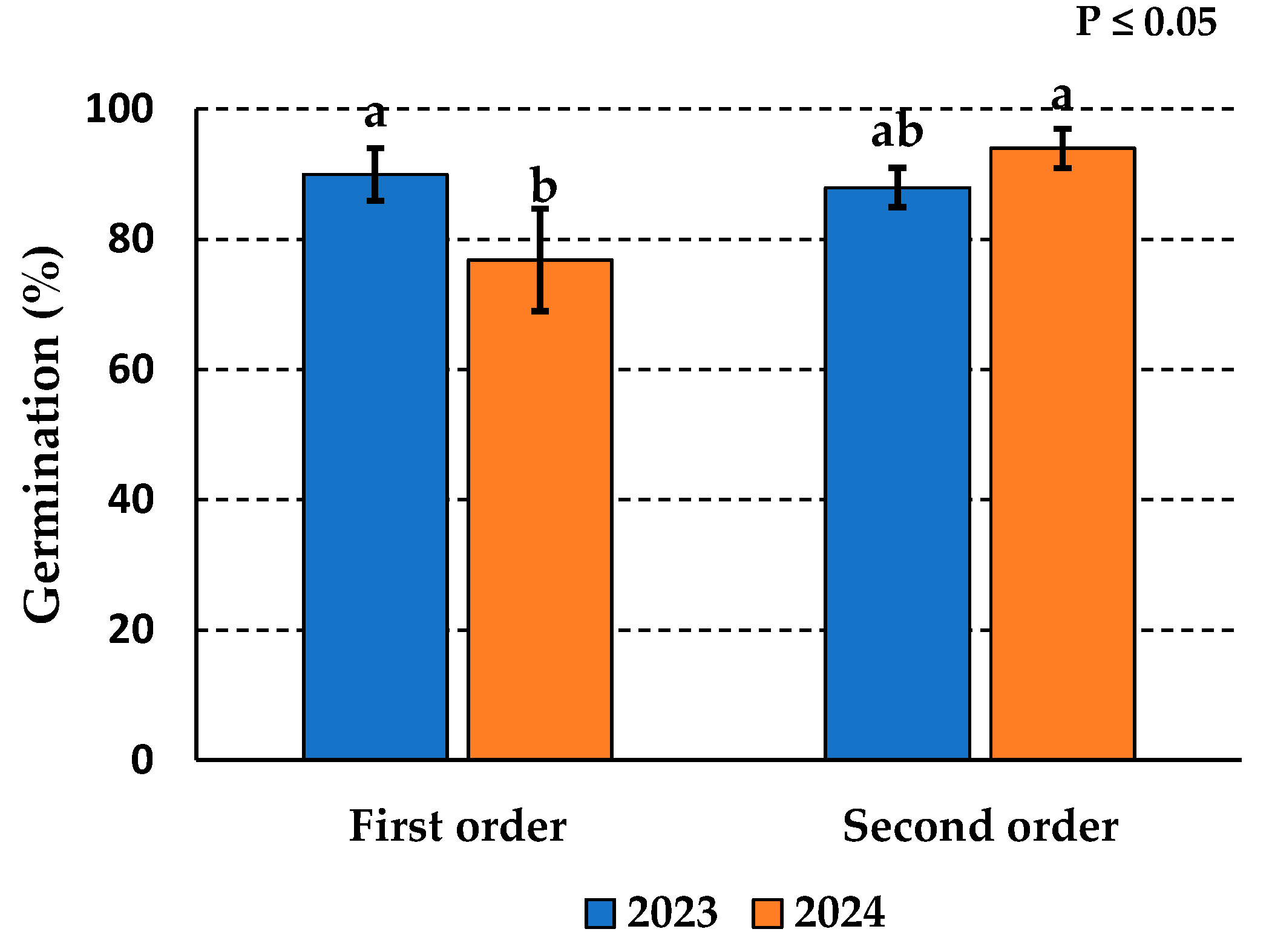

3.3. Germination Rate

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Que, F.; Hou, X.-L.; Wang, G.-L.; Xu, Z.-S.; Tan, G.-F.; Li, T.; Wang, Y.-H.; Khadr, A.; Xiong, A.-S. Advances in Research on the Carrot, an Important Root Vegetable in the Apiaceae Family. Hortic Res 2019, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renna, M.; Montesano, F.; Signore, A.; Gonnella, M.; Santamaria, P. BiodiverSO: A Case Study of Integrated Project to Preserve the Biodiversity of Vegetable Crops in Puglia (Southern Italy). Agriculture 2018, 8, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renna, M.; Serio, F.; Signore, A.; Santamaria, P. The Yellow–Purple Polignano Carrot (Daucus Carota L.): A Multicoloured Landrace from the Puglia Region (Southern Italy) at Risk of Genetic Erosion. Genet Resour Crop Evol 2014, 61, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarano, A.; Gerardi, C.; D’Amico, L.; Accogli, R.; Santino, A. Phytochemical Analysis and Antioxidant Properties in Colored Tiggiano Carrots. Agriculture 2018, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefola, M.; Pace, B.; Renna, M.; Santamaria, P.; Signore, A.; Serio, F. COMPOSITIONAL ANALYSIS AND ANTIOXIDANT PROFILE OF YELLOW, ORANGE AND PURPLE POLIGNANO CARROTS.

- PAT Puglia - Carota Di Polignano Available online: https://www.patpuglia.it/it/12/Carota_di_Polignano/5_85_C. (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- PAT Puglia - Carota Giallo Viola Di Tiggiano Available online: https://www.patpuglia.it/it/12/Carota_giallo-viola_di_Tiggiano/5_87_C (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Didonna, A.; Renna, M.; Santamaria, P. Traditional Italian Agri-Food Products: A Unique Tool with Untapped Potential. Agriculture 2013, 13, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apulian regional register of plants genetic resources Available online: https://filiereagroalimentari.regione.puglia.it/agrobiodiversit%C3%A0-registro-regionale (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Didonna, A.; Santamaria, P. Biodiversity of Vegetable Species: Issues and Opportunities through Environmental Policies and Research. International Journal of Vegetable Science 2024, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didonna, A.; Bocci, R.; Renna, M.; Santamaria, P. The Conservation Varieties Regime: Its Past, Present and Future in the Protection and Commercialisation of Vegetable Landraces in Europe. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UPOV_carrot Available online: https://www.upov.int/test_guidelines/en/fulltext_tgdocs.jsp?lang_code=EN&q=daucus (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Louwaars, N.P. Seed Systems: Managing, Using and Creating Crop Genetic Resources. In Routledge Handbook of Agricultural Biodiversity; Routledge, 2017 ISBN 978-1-315-79735-9.

- Andersen, R. (2009). Information Paper on Farmers’ Rights Submitted by the Fridtjof Nansen Institute, Norway, Based on the Farmers’ Rights Project - Farmers Rights Available online: https://www.farmersrights.org/literature-and-other-resources/global-level-and-conceptual-work-1/andersen-r-2009-information-paper-on-farmers-rights-submitted-by-the-fridtjof-nansen-institute-norway-based-on-the-farmers-rights-project (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Almekinders, C.J.M.; Louwaars, N.P. The Importance of the Farmers’ Seed Systems in a Functional National Seed Sector. Journal of New Seeds 2002, 4, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, B. An Agrobiodiversity Perspective on Seed Policies. Journal of New Seeds 2002, 4, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzetti, F.; Negri, V. The European Seed Legislation on Conservation Varieties. In European Landraces: On-Farm Conservation, Management and Use; Biodiversity International: Rome, Italy, 2009 ISBN 978-92-9043-805-2.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Forestry National Plan on Biodiversity of Agricultural Interest. 2008.

- Pimbert, M.P. Participatory Research and On-Farm Management of Agricultural Biodiversity in Europe; IIED.; London UK, 2011; ISBN 978-1-84369-809-8.

- European Commission Commission Directive 2009/145/EC of 26 November 2009 Providing for Certain Derogations, for Acceptance of Vegetable Landraces and Varieties Which Have Been Traditionally Grown in Particular Localities and Regions and Are Threatened by Genetic Erosion and of Vegetable Varieties with No Intrinsic Value for Commercial Crop Production but Developed for Growing under Particular Conditions and for Marketing of Seed of Those Landraces and varietiesText with EEA Relevance. Official Journal of the European Union 2009, 312/44.

- Frese, L.; Reinhard, U.; Bannier, H.; Germeier, C.U. Landrace Inventory in Germany - Preparing the National Implementation of the EU Directive 2008/62/EC. In European Landraces: On-Farm Conservation, Management and Use; Biodiversity International, 2009 ISBN 978-92-9043-805-2.

- DECRETO LEGISLATIVO 30 Dicembre 2010, n. 267 Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/vediMenuHTML?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2011-02-11&atto.codiceRedazionale=011G0033&tipoSerie=serie_generale&tipoVigenza=originario (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- DECRETO LEGISLATIVO 2 febbraio 2021, n. 20 Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2021/02/27/21G00022/sg (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Gray, D.; Steckel, J.R.A.; Dearman, J.; Brocklehurst, P.A. Some Effects of Temperature during Seed Development on Carrot ( Daucus Carota ) Seed Growth and Quality. Annals of Applied Biology 1988, 112, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, D.; Steckel, J.R.A.; Ward, J.A. Studies on Carrot Seed Production: Effects of Plant Density on Yield and Components of Yield. Journal of Horticultural Science 1983, 58, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.S.; Nascimento, W.M.; Vieira, J.V. Carrot Seed Germination and Vigor in Response to Temperature and Umbel Orders. Sci. agric. (Piracicaba, Braz.) 2008, 65, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocklehurst, P.A.; Dearman, J. The Germination of Carrot (Daucus Carota L.) Seed Harvested on Two Dates: A Physiological and Biochemical Study. Journal of Experimental Botany 1980, 31, 1719–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin, A.; McGill, C.; Ward, A.; Sofkova-Bobcheva, S.; Pieralli, S. Phenological Phase Affects Carrot Seed Production Sensitivity to Climate Change – A Panel Data Analysis. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 892, 164502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council Directive 2002/55/EC of 13 June 2002 on the Marketing of Vegetable Seed Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX%3A32002L0055 (accessed on 13 December 2024).

| Descriptor | Score scale | Score | |

| ‘Tiggiano’ | ‘Polignano’ | ||

| Foliage: width of crown | 3, narrow; 5, medium; 7, broad | 5 | 7 |

| Leaf: attitude | 1, erect; 3, semi-erect; 5, prostate | 1 | 3 |

| Leaf: length (including petiole) | 1, very short; 3, short; 5, medium; 7, long; 9, very long | 7 | 7 |

| Leaf: division | 3, fine; 5, medium; 7, coarse | 5 | 5 |

| Leaf: intensity of green color | 3, light; 5, medium; 7, dark | 3 | 5 |

| Leaf: anthocyanin coloration of petiole | 1, absent; 9, present | 1 | 1 |

| Root: length | 1, very short; 3, short; 5, medium; 7, long; 9, very long | 7 | 5 |

| Root: width | 3, narrow; 5, medium; 7, broad | 5 | 5 |

| Root: ratio length/width | 1, very small; 3, small; 5, medium; 7, large; 9, very large | 7 | 5 |

| Root: shape in longitudinal section | 1, circular; 2, obovate; 3, medium obtriangolar; 4, narrow obtriangular; 5, narrow obtriangular to narrow oblong; 6 narrow oblong | 4 | 4 |

| Root: tendency to conical shape | 1, very weak; 3, weak; 5, medium; 7, strong; 9, very strong | 7 | 7 |

| Root: shape of shoulder | 1, flat; 2, flat to rounded; 3, rounded; 4, rounded to conical; 5, conical | 1 | 1 |

| Root: tip (when fully developed) | 1, blunt; 2, slightly pointed; 3, strongly pointed | 3 | 3 |

| Root: external color | 1, white; 2, yellow; 3, orange; 4, pinkish red; 5, red; 6 purple | 2 and 6 | 2, 3 and 6 |

| Root: intensity of external color | 3, light; 5, medium; 7, dark | 5 | 5 |

| Root: anthocyanin coloration of skin ofshoulder | 1, present; 9, absent | 9 | 9 |

| Root: extent of green color of skin of shoulder | 1, absent o very small; 3, small; 5, medium; 7, large; 9, very large | 3 | 5 |

| Root: ridging of surface | 1, absent o very weak; 3, weak; 5, medium; 7, strong; 9, very strong | 3 | 3 |

| Root: diameter of core relative to totaldiameter | 1, very small; 3, small; 5, medium; 7, large; 9, very large | 5 | 5 |

| Root: color of core | 1, white; 2, yellow; 3, orange; 4, pinkish red; 5, red; 6 purple | 2 | 1 and 2 |

| Root: intensity of color of core | 3, light; 5, medium; 7, dark | 3 | 3 |

| Root: color of cortex | 1, white; 2, yellow; 3, orange; 4, pinkish red; 5, red; 6 purple | 2 and 6 | 2, 3 and 6 |

| Root: intensity of color of cortex | 3, light; 5, medium; 7, dark | 7 | 5 |

| Root: color of core compared to color ofcortex | 1, lighter; 2, same; 3, darker | 1 | 1 |

| Root: extent of green coloration of interior (in longitudinal section) | 1, absent o very small; 3, small; 5, medium; 7, large; 9, very large | 1 | 1 |

| Root: protrusion above soil | 1, absent o very small; 3, small; 5, medium; 7, large; 9, very large | 1 | 3 |

| Root: time of coloration of tip inlongitudinal section | 1, very early; 3, early; 5, medium; 7, late; 9, very late | 5 | 5 |

| Plant: height of primary umbel at time of its flowering | 3, short; 5, medium; 7, tall | 5 | 5 |

| Plants: proportion of male sterile plants | 1, absent o very low; 2, intermediate; 3, high | 2 | 1 |

| Attributes | Seed lenght | Seed width | Weight of 1000 seeds | |

| (mm) | (g) | |||

| Year (A) | ||||

| 2023 | 4.19 | 1.96 | 2.16 | |

| 2024 | 3.74 | 1.71 | 1.74 | |

| Significance(1) | *** | *** | *** | |

| Umbel order (B) | ||||

| First | 4.32 | 2.00 | 2.13 | |

| Second | 3.67 | 1.67 | 1.76 | |

| Significance | *** | *** | *** | |

| Attributes | Seed lenght | Seed width | Weight of 1000 seeds | |

| (mm) | (g) | |||

| Year (A) | ||||

| 2023 | 4.53 | 1.95 | 2.56 | |

| 2024 | 4.63 | 1.91 | 2.44 | |

| Significance(1) | *** | *** | *** | |

| Umbel order (B) | ||||

| First | 4.61 | 1.95 | 2.69 | |

| Second | 4.54 | 1.91 | 2.31 | |

| Significance(1) | *** | *** | *** | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).