Submitted:

28 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

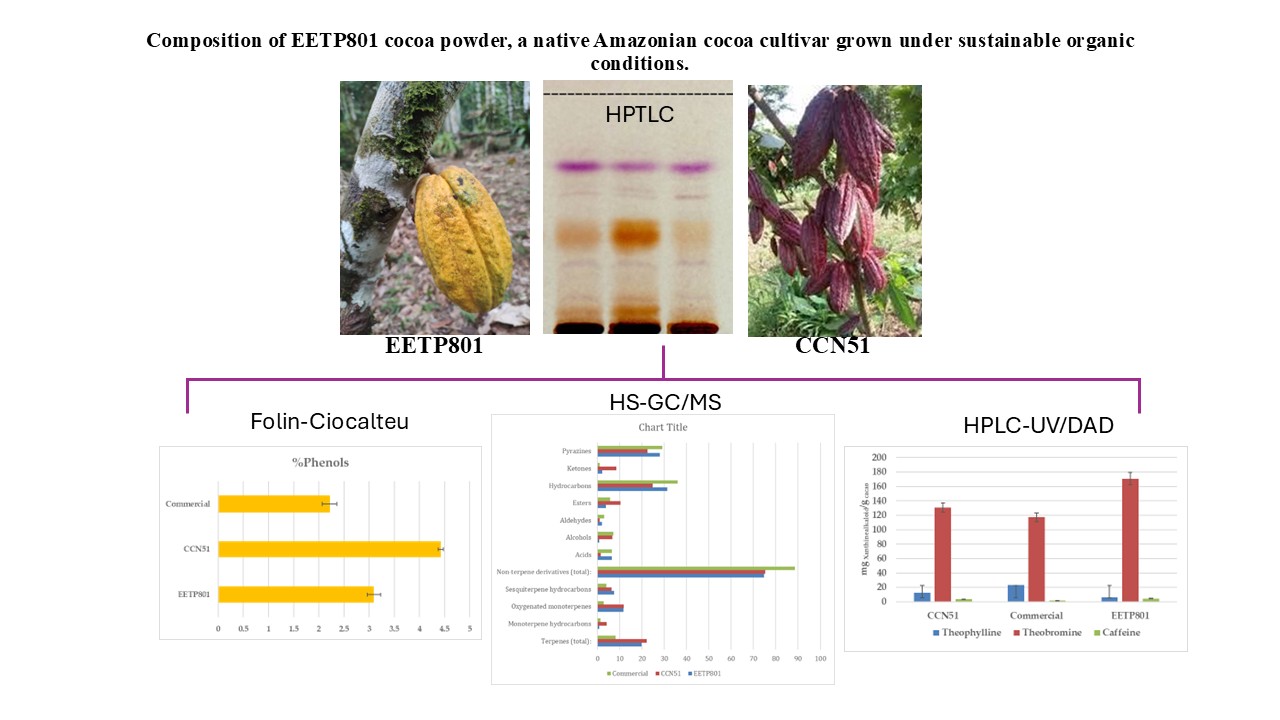

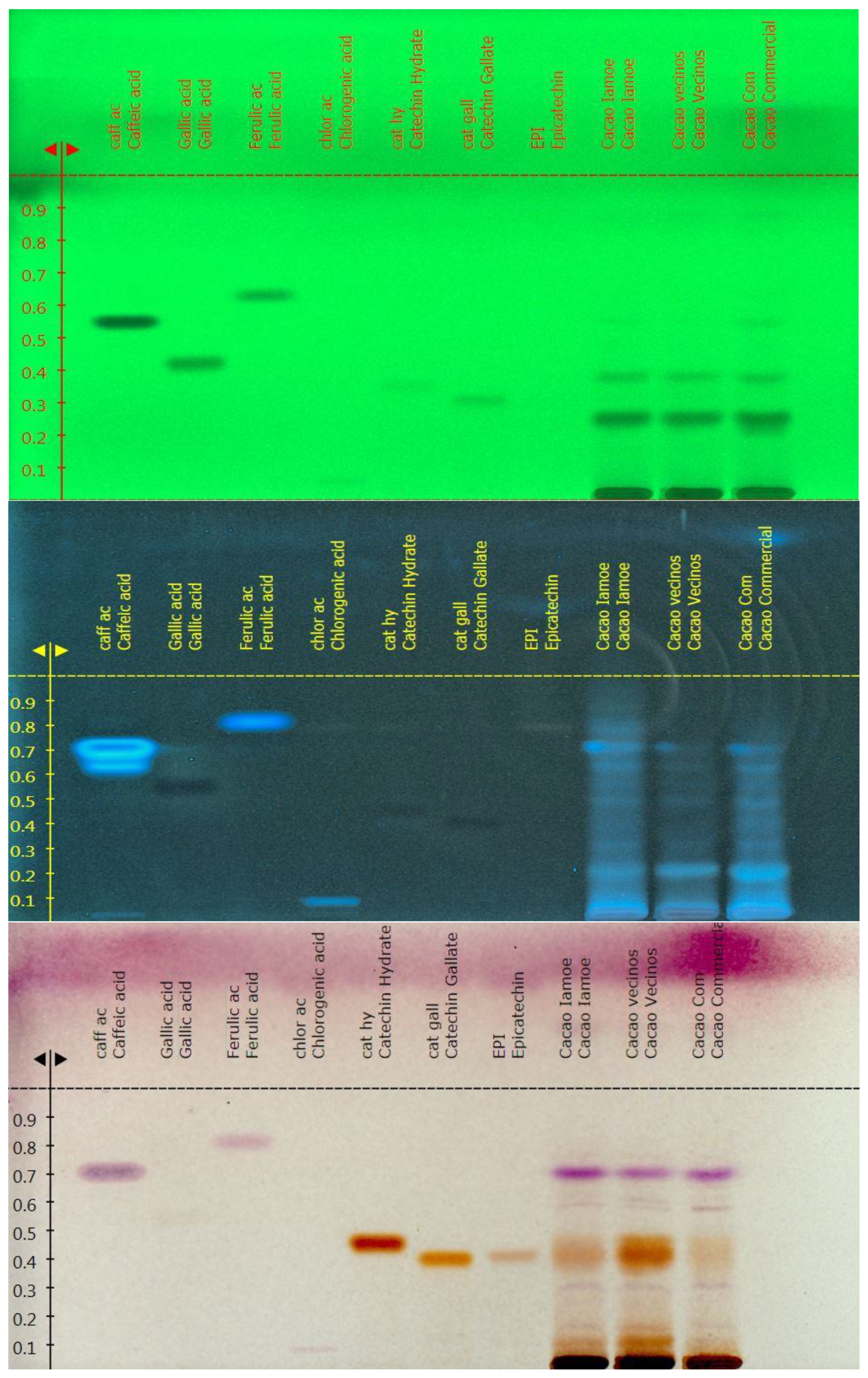

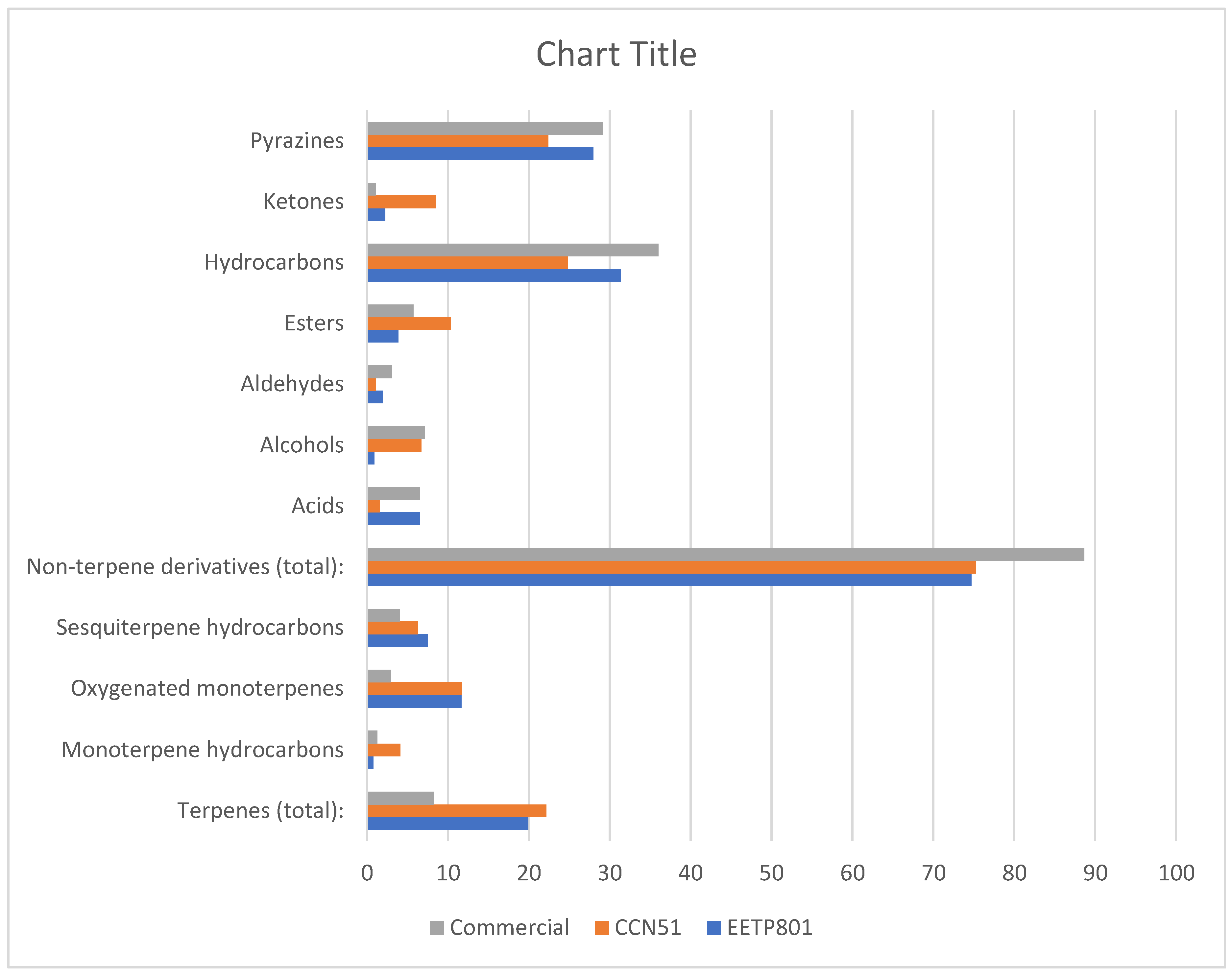

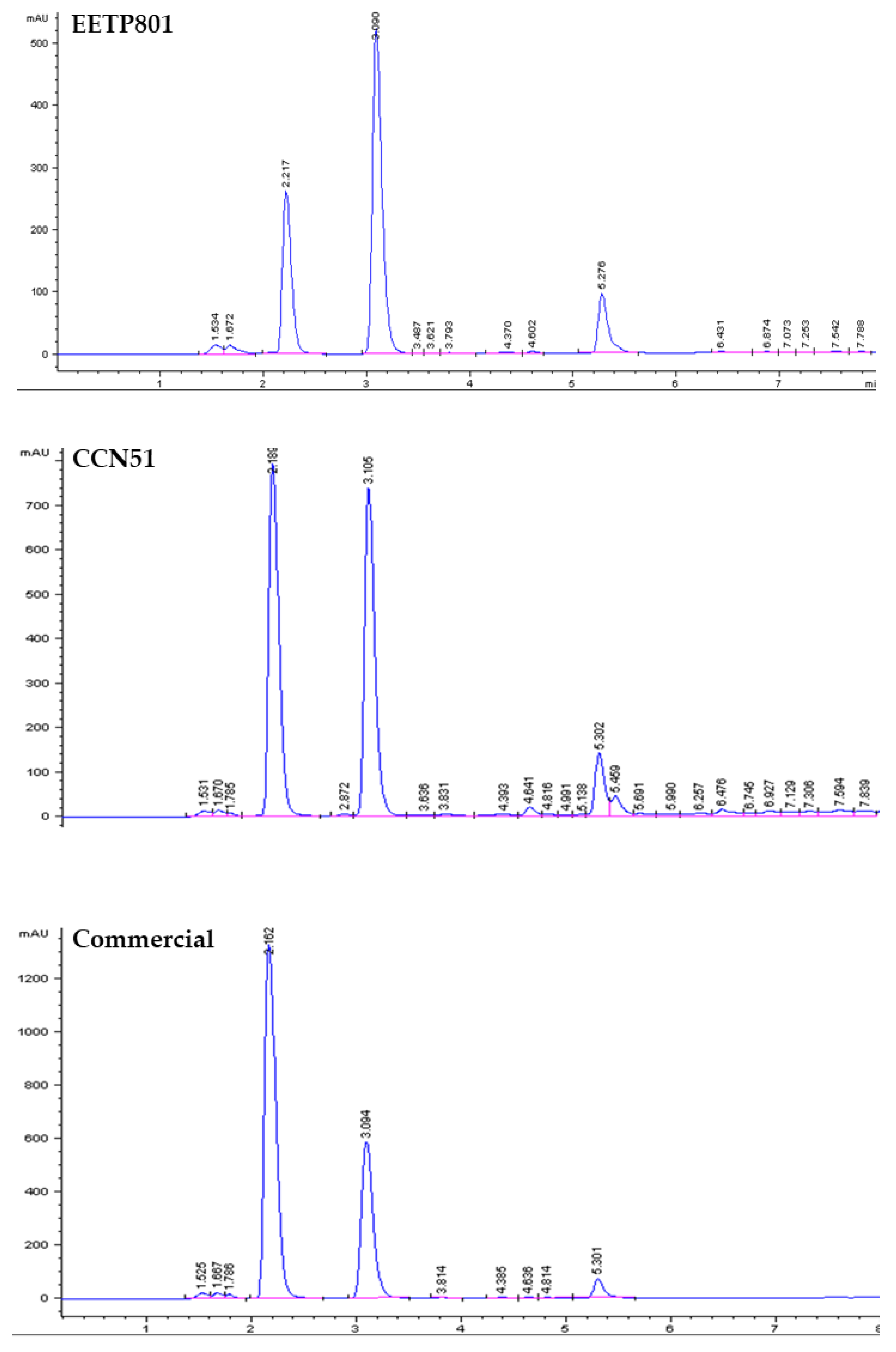

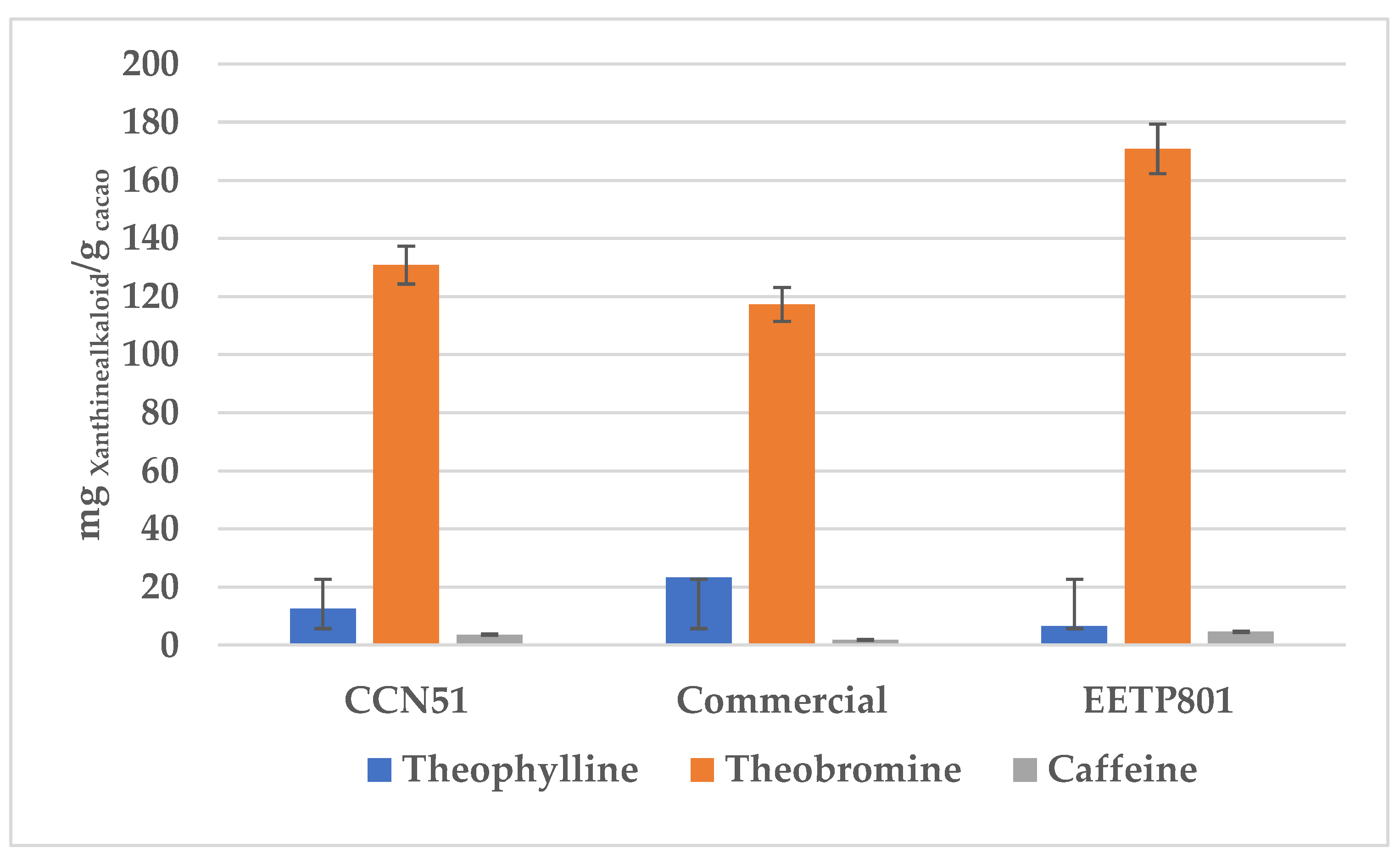

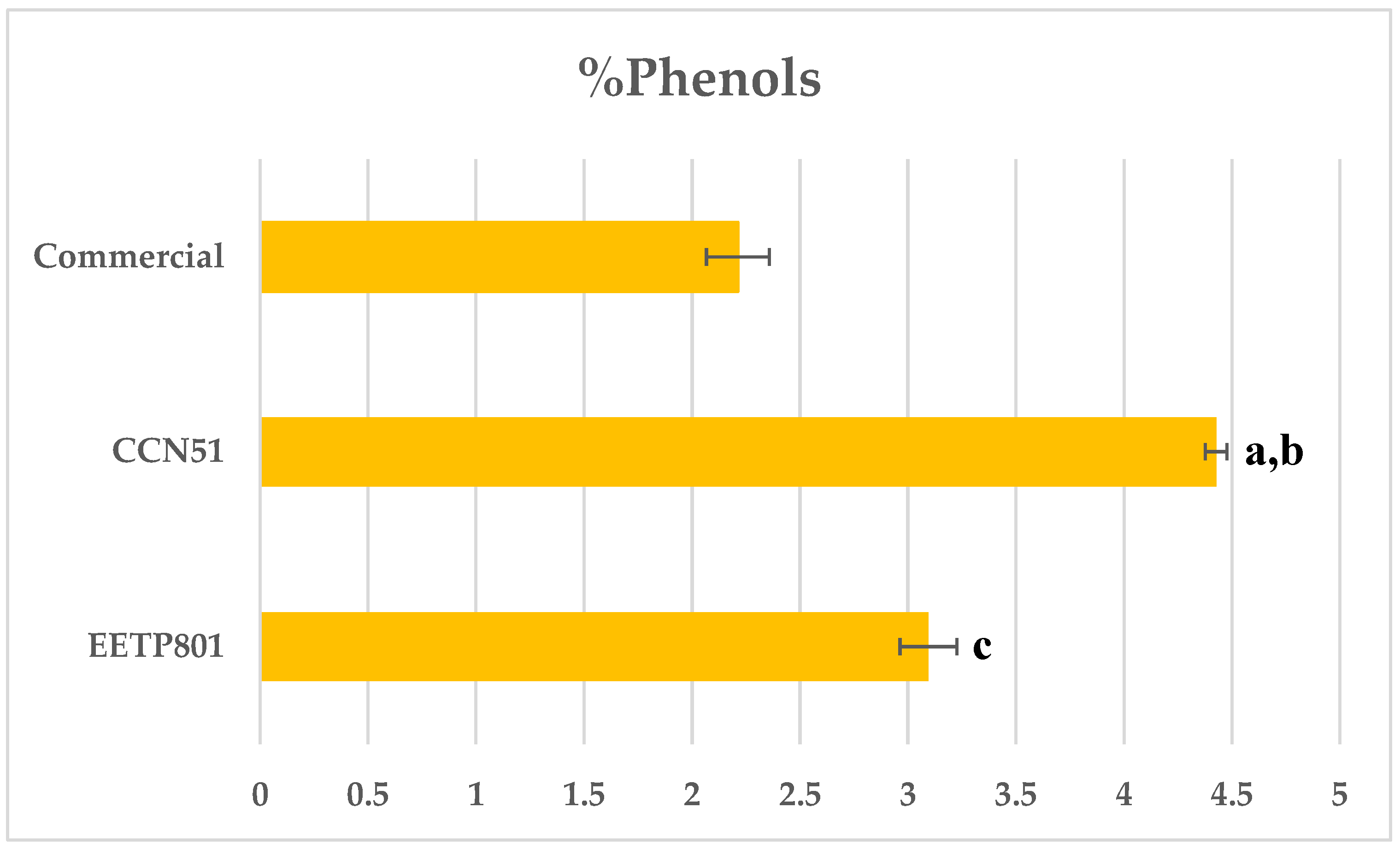

In this study, we have analysed the Amazonian variety EETP801 Cacao, grown under sustainable organic conditions, in comparison to CCN51 cacao grown on a neighbouring commercial farm using standard practices and an European commercial cacao powdered beverage. The overall metabolite profile was analysed by high performance TLC analyses (HPTLC), the volatile fraction by head-space gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (HS-GC-MS) and the xanthine alkaloids by quantitative liquid chromatography-UV photodiode array (HPLC-DAD) analyses. Total polyphenol content was determined by the Folin-Ciocalteu method. Despite the reduced production of cocoa by the EETP801 cultivar in comparison with the CCN51 cultivar, the obtained produce is significantly richer in theobromine (130 mg vs 170 mg per g of cacao) with CCN51 having double concentration of theophylline (12.6 vs 6.5 mg per g of cacao). Qualitatively, EETP-801 has the same polyphenolic composition (as per the HPTLC fingerprint) of the CCN51 cultivar but shows more traces of glycosylated flavonoids (rutin). The HS-GC-MS analyses revealed that the fragrance of both Amazonian cacao samples was superior to that of the commercial sample. The variability in the artisan fermentation and roasting processes influenced certain aspects of the volatile composition. The cultivar EETP801 is a viable option for a more ecologically conscious sector of the cocoa beverages consumer group.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Extraction

2.3. Phenol Content Determination by the Folin-Ciocalteu’s Method.

2.4. High-Performance Thin Layer Chromatography (HPTLC)

2.5. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

2.6. Solid Phase Micro-Extraction of Volatiles

2.7. GC/MS Analysis of Volatiles

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Total Phenol Content

3.2. Chromatographic Fingerprint of the Amazonian Samples

3.3. Analysis of the Volatile Metabolites of the Amazonian Samples

| Constituents | L.R.I.a | Relative abundance (%) | ||

| Commercial | CCN51 | EETP801 | ||

| acetic acid | 599 | 5.52 | -b | 5.56 |

| ethyl acetate | 616 | - | 7.58 | - |

| 2,3-butanediol | 799 | 5.78 | 2.24 | - |

| 2-methyl pyrazine | 833 | 1.21 | 0.33 | 1.04 |

| isovaleric acid | 834 | 1.03 | 0.99 | 0.6 |

| 2-methylbutanoic acid | 860 | - | 0.55 | 0.39 |

| isopentyl acetate | 876 | - | 0.15 | - |

| 2-heptanone | 891 | - | 0.9 | - |

| 2-heptanol | 902 | - | 3.29 | 0.88 |

| 2,6-dimethyl pyrazine | 910 | 3.18 | 1.73 | 5.1 |

| 2,5-dimethyl pyrazine | 920 | - | 0.9 | - |

| 2-ethyl pyrazine | 925 | 1.51 | - | - |

| 2,3-dimethyl pyrazine | 930 | 0.96 | 0.6 | 1.02 |

| benzaldehyde | 963 | 2.06 | 0.63 | 0.77 |

| myrcene | 993 | - | 0.85 | - |

| 2-ethyl-6-methyl pyrazine | 1001 | 1.42 | 0.75 | 1.44 |

| 2,3,5-trimethyl pyrazine | 1005 | 5.64 | 4.84 | 6.45 |

| limonene | 1032 | 1.26 | 1.72 | 0.76 |

| (Z)-β-ocimene | 1042 | - | 1.31 | - |

| (E)-β-ocimene | 1052 | - | 0.22 | - |

| acetophenone | 1068 | - | 0.47 | 0.63 |

| trans-linalool oxide (furanoid) | 1076 | - | 1.4 | 1.09 |

| 2,6-diethyl pyrazine | 1080 | 3.57 | 2.58 | 6.31 |

| 2,3,5,6-tetramethyl pyrazine | 1086 | 10.04 | 9.6 | - |

| cis-linalool oxide (furanoid) | 1090 | - | - | 5.53 |

| 2-nonanone | 1093 | 1.05 | 7.1 | 1.13 |

| n-undecane | 1100 | - | 1.19 | 0.87 |

| linalool | 1101 | 1.01 | 8.64 | 2.66 |

| nonanal | 1102 | 1.01 | - | 1.16 |

| isodihydrolavandulyl aldehyde | 1110 | - | - | 2.01 |

| phenylethyl alcohol | 1111 | - | 1.15 | - |

| trans-limonene oxide | 1141 | - | 0.14 | - |

| 5H-5-methyl-6,5-dihydrocyclopentapyrazine | 1142 | - | - | 0.32 |

| camphor | 1143 | 0.63 | 0.27 | 0.36 |

| 3,5-diethyl-2-methyl pyrazine | 1156 | 0.78 | 0.27 | 0.99 |

| 2,3,5-trimethyl-6-ethyl pyrazine | 1163 | 0.83 | 0.8 | 1.59 |

| tetrahydrolavandulol | 1168 | - | 0.19 | - |

| trans-linalool oxide (pyranoid) | 1177 | - | 0.93 | - |

| α-terpineol | 1191 | - | 0.17 | - |

| 1-dodecene | 1192 | 1.58 | 0.42 | - |

| n-dodecane | 1200 | 1.96 | 8.9 | 8.53 |

| decanal | 1204 | - | 0.4 | - |

| 2,5-dimethyl-3-(2-methylpropyl) pyrazine | 1208 | - | - | 2.07 |

| 2-phenylethyl acetate | 1258 | 2.69 | 2.61 | 1.45 |

| 1-tridecene | 1292 | 5.12 | 0.3 | 0.61 |

| 2-undecanone | 1294 | - | - | 0.46 |

| 2,5-dimethyl-3-(3-methylbutyl) pyrazine | 1298 | - | - | 1.62 |

| n-tridecane | 1300 | 4.08 | 11.37 | 16.44 |

| 1-nonanol acetate | 1312 | 0.48 | - | - |

| (Z)-2-tridecene | 1315 | - | 0.12 | 0.42 |

| geranyl acetate | 1385 | 1.26 | - | - |

| isolongifolene | 1387 | - | 0.27 | - |

| 1-tetradecene | 1392 | 6.37 | 0.19 | - |

| ethyl decanoate | 1395 | 0.9 | - | 0.65 |

| β-longipinene | 1398 | 3.31 | 3.18 | - |

| n-tetradecane | 1400 | 5.88 | 1.91 | 3.5 |

| longifolene | 1403 | - | 0.48 | 0.98 |

| β-caryophyllene | 1420 | - | 0.33 | 0.7 |

| α-neo-clovene | 1454 | 0.74 | 0.58 | - |

| γ-muurolene | 1477 | - | - | 0.39 |

| cis-β-guaiene | 1490 | - | 0.23 | - |

| epizonarene | 1497 | - | 0.54 | - |

| α-muurolene | 1498 | - | 0.19 | 1.17 |

| n-pentadecane | 1500 | 7 | - | - |

| trans-γ-cadinene | 1513 | - | - | 1.11 |

| δ-cadinene | 1524 | - | 0.49 | 3.13 |

| ethyl dodecanoate | 1596 | 1.63 | - | 1.75 |

| n-hexadecane | 1600 | 1.66 | 0.4 | 0.96 |

| 1-tetradecanol | 1676 | 1.37 | - | - |

| n-heptadecane | 1700 | 2.35 | - | - |

| Total identified: | 96.87% | 97.39% | 94.60% | |

3.4. Quantitative Analysis of the Xanthine Alkaloids in Cocoa Samples

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diby, L.; Kahia, J.; Kouamé, C.; Aynekulu, E. Tea, Coffee, and Cocoa. In Encyclopedia of Applied Plant Sciences; Elsevier, 2017; pp. 420–425 ISBN 978-0-12-394808-3.

- International Monetary Fund Primary Commodities: Market Developments & Outlook; World Economic and Financial Surveys; International Monetary Fund: Washington, D.C., 1986; ISBN 978-1-4519-4304-7.

- Coe, S.D.; Coe, M.D. The True History of Chocolate; Thames & Hudson: New York, 1996; ISBN 978-0-500-29474-1. [Google Scholar]

- Barišić, V.; Icyer, N.C.; Akyil, S.; Toker, O.S.; Flanjak, I.; Ačkar, Đ. Cocoa Based Beverages – Composition, Nutritional Value, Processing, Quality Problems and New Perspectives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 132, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Garrido, J.A.; García-Sánchez, J.R.; López-Victorio, C.J.; Escobar-Ramírez, A.; Olivares-Corichi, I.M. Cocoa: A Functional Food That Decreases Insulin Resistance and Oxidative Damage in Young Adults with Class II Obesity. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2023, 17, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhou, J.; Yang, J.; Lou, H.; Zhao, B.; Chi, J.; Tang, W. Dark Chocolate Intake and Cardiovascular Diseases: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kongor, J.E.; Owusu, M.; Oduro-Yeboah, C. Cocoa Production in the 2020s: Challenges and Solutions. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2024, 5, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Lee, K. Environmental Consciousness, Purchase Intention, and Actual Purchase Behavior of Eco-Friendly Products: The Moderating Impact of Situational Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, S.; Sarkar, T.; Chakraborty, R.; Rebezov, M.; Shariati, M.A.; Thiruvengadam, M.; Rengasamy, K.R.R. Dark Chocolate: An Overview of Its Biological Activity, Processing, and Fortification Approaches. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 1916–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainforest Alliance, T. Rainforest Alliance Certified Cocoa 2022.

- Halliday, J. Mars Pledges Sustainable Cocoa Only by 2020. Available online: https://www.foodnavigator.com/Article/2009/04/10/Mars-pledges-sustainable-cocoa-only-by-2020/ (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Heredia-R, M.; Blanco-Gutiérrez, I.; Esteve, P.; Puhl, L.; Morales-Opazo, C. Assessment of Sustainability in Cocoa Farms in Ecuador: Application of a Multidimensional Indicator-Based Framework. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2024, 22, 2379863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EETP-801. Available online: https://icgd.reading.ac.uk/all_data.php?nacode=33607&&tables=planting_mat-country (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Ramiro-Puig, E.; Castell, M. Cocoa: Antioxidant and Immunomodulator. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 101, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonvehí, J.S. Investigation of Aromatic Compounds in Roasted Cocoa Powder. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2005, 221, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Campos, J.; Escalona-Buendía, H.B.; Contreras-Ramos, S.M.; Orozco-Avila, I.; Jaramillo-Flores, E.; Lugo-Cervantes, E. Effect of Fermentation Time and Drying Temperature on Volatile Compounds in Cocoa. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Durme, J.; Ingels, I.; De Winne, A. Inline Roasting Hyphenated with Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry as an Innovative Approach for Assessment of Cocoa Fermentation Quality and Aroma Formation Potential. Food Chem. 2016, 205, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afoakwa, E.O. Chocolate Science and Technology; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, U.K. ; Ames, Iowa, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4051-9906-3.

- Rodriguez-Campos, J.; Escalona-Buendía, H.B.; Orozco-Avila, I.; Lugo-Cervantes, E.; Jaramillo-Flores, M.E. Dynamics of Volatile and Non-Volatile Compounds in Cocoa (Theobroma Cacao L.) during Fermentation and Drying Processes Using Principal Components Analysis. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.D.; Van De Walle, D.; De Clercq, N.; De Winne, A.; Kadow, D.; Lieberei, R.; Messens, K.; Tran, D.N.; Dewettinck, K.; Van Durme, J. Assessing Cocoa Aroma Quality by Multiple Analytical Approaches. Food Res. Int. 2015, 77, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.; San Andrés, V.; Cervera, M.; Redondo, A.; Alquézar, B.; Shimada, T.; Gadea, J.; Rodrigo, M.J.; Zacarías, L.; Palou, L.; et al. Terpene Down-Regulation in Orange Reveals the Role of Fruit Aromas in Mediating Interactions with Insect Herbivores and Pathogens. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, I.S. Tailoring Wine Yeast for the New Millennium: Novel Approaches to the Ancient Art of Winemaking. Yeast 2000, 16, 675–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acierno, V.; Yener, S.; Alewijn, M.; Biasioli, F.; Van Ruth, S. Factors Contributing to the Variation in the Volatile Composition of Chocolate: Botanical and Geographical Origins of the Cocoa Beans, and Brand-Related Formulation and Processing. Food Res. Int. 2016, 84, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinap, S.; Dimick, P.S.; Hollender, R. Flavour Evaluation of Chocolate Formulated from Cocoa Beans from Different Countries. Food Control 1995, 6, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauendorfer, F.; Schieberle, P. Identification of the Key Aroma Compounds in Cocoa Powder Based on Molecular Sensory Correlations. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 5521–5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frauendorfer, F.; Schieberle, P. Changes in Key Aroma Compounds of Criollo Cocoa Beans During Roasting. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 10244–10251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).