1. Introduction

The world's population is rapidly aging, and it is predicted that by 2050, individuals aged 60 and over will comprise 20-25% of the total population. Age-related neurological complications are common and affect an individual's quality of life. Therefore, understanding the key mechanisms associated with age-related changes, as well as the factors that trigger these inevitable destructive events in brain structure and function, are essential for identifying new therapeutic approaches to meet the needs of aging population. This elucidation will contribute to the development of multimodal health strategies to increase quality of life and lifespan.

The pineal gland, often considered as a key regulator of circadian rhythms, is thought to play a central role in modulating growth, fertility, aging and death [

1]. Some studies suggest that the gland follows a biologically "programmed" timeline, particularly influenced by the secretion of melatonin, a hormone known to regulate sleep-wake cycles and possess antioxidant properties. As we age, the pineal gland becomes calcified and melatonin production decreases significantly [

2,

3,

4]. This decline is associated with several aging-related processes, including decreased antioxidant defense system, weakened immune function, and disruptions in circadian rhythms. Decreased melatonin is thought to accelerate aging at the cellular level, leading to the gradual onset of age-related diseases such as neurodegenerative disorders. Accordingly, this gland is seen as a "clock" that "tracks and regulates" the ontogenetic phases of our genetically inherited "program" of life.

On the other hand, the alterations in the sphingolipid (SL) metabolism leading to oxidative dysfunction are critical to age-related processes and diseases [

5,

6]. There are few data in the scientific literature indicating a link between the melatonin system and SL signaling [

7,

8]. Elucidating the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the most fundamental aspect of our life program will help to develop a rational strategy to improve the health status of the elderly. SLs are a very diverse group of amphipathic lipids that are abundant in cell membranes. They can be classified into two main classes according to the type of polar group in their structure: phosphosphingolipids (PSLs), including sphingomyelin (SM), and glycosphingolipids (GSLs) – cerebrosides and gangliosides [

9]. SLs play an important structural role in biological membranes, including neuronal membranes, and are precursors of many bioactive metabolites that regulate various cellular functions including senescence regulation which is critical in aging [

6]. In this respect the finely tuned balance between the synthesis and degradation of SLs is normally critical for scores of biological processes [

10], so changes in their metabolism can affect homeostasis and brain function.

Sphingomyelin is a major source of ceramides (Cer), that are lipid second messengers formed when SM is cleaved by neutral or acid sphingomyelinases (NSMase and ASMase). The latter enzymes are activated by inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress (OS) [

11] or inhibition of Cer metabolism enzymes such as SM synthase, which converts Cer to SM, and acid ceramidase (ASAH1), which hydrolyzes Cer to sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) [

12]. Ceramide is an important bioactive molecule involved in the regulation of several physiological processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and programmed cell death (apoptosis) [

13]. The induced conversion of SM to Cer in many cell types, including neurons, results in toxicity expressed as pro-apoptotic effects. The consequence of this process is tissue damage and organ dysfunction. In parallel, the decreased level of cellular S1P has been shown to promote cellular senescence [

6]. On the other hand, low levels of Cer and high level of S1P have trophic effects and promote survival after cell division. The differential regulation of opposing pathways between Cer and S1P is known as the “SL Rheostat” demonstrating Ce’s ability to induce cell growth arrest and apoptosis, while S1P is responsible for optimal cell proliferation and growth as well as the suppression of ceramide mediated growth arrest and apoptosis [

14]. One of the major activators of Cer generation is OS caused by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. A link between aging tissue and NSMase activity has also been reported [

15] along with a correlation between NSMase activity and cellular senescence [

16]. Although ASMase is more active than NMase, higher activity of both enzymes was observed in the liver of aged rats than in young ones [

17]. These enzymes are considered biomarkers of aging because their levels increase with age in mammals and are thought to play a role in age-related diseases, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular and immune dysfunction, cancer, and neurodegeneration. However, Cer may not be the only contributing factor to the induction of senescence and aging. ASAH1 which catalyzes Cer into fatty acid and sphingosine has also been shown to be highly upregulated in senescent cells, and silencing ASAH1 in presence of human fibroblasts decreased the expression levels of senescent associated proteins P53, P21, and P16 [

18]. The close association between Cer accumulation, increased OS and insulin resistance is intriguing, as these changes are thought to accelerate aging and age-related diseases. In adult rats, accumulation of specific Cer species in mitochondria has been found, a process that correlates with impaired function of complex IV in the electron transport chain [

19] and corresponds to increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) during aging. There is a negative correlation between glutathione levels and mitochondrial NSMase activity, suggesting that the therapeutic effect of antioxidant molecules works by preventing NSMase activation and Cer accumulation by maintaining normal glutathione levels. These data support the idea that Cer accumulation is a contributing factor in age-related diseases and that strategies to prevent such accumulation may potentially reduce the incidence and severity of these diseases. Melatonin has been shown to suppress ASMase in the hippocampus of mice and cell lines in a manner similar to antidepressants, while the diurnal regulation of S1P and sphinganine 1-phosphate is dependent on intact melatonin signalling [

7].

Previous publications provide a basis for formulating a hypothesis that there is a functional link between the melatonin system and SL pathways that is critical for aging processes, including impaired homeostasis of oxidative status in the central nervous system (CNS). The work of Pierpaoli and Bulian [

20] has shown that the role of melatonin in aging is strictly age-specific. This prompted us to plan a comparative analysis of SL metabolism in sham-operated and pinealectomized rats at 3, 14, and 18 months of age, respectively. At these ages, melatonin deficiency was found to accelerate, slow, or have no effect on the aging process in mice and rats [

20,

21,

22]. The relationship between the pineal hormone and the SL pathway in the mechanisms mediating the aging process was investigated by examining the levels of key metabolites of SM such as Cer, S1P, along with enzymes involved in their processing, namely NSMase, ASMase, and ASAH1 at specific age periods. The changes in the oxidative status in the CNS are directly dependent on the perturbation in the SM metabolism during aging, but the role of melatonin deficiency in modulating these processes in an ontogenetic aspect, which we believe is a critical factor in aging, will be clarified in this study.

3. Discussion

The present findings revealed that melatonin deficiency associated with hormonal dysfunction induces an age-specific alteration in SL metabolism in the hippocampus and plasma in rats. It is well-known that neuronal function is closely related to the homeostasis of SLs in both animals and humans while aging is vulnerable to dysregulation of SL metabolism and thus the abnormalities affect hippocampus-based memory. In this study, we showed that old rats had increased levels of SM, Cer and Cer-derivative S1P in both the hippocampus and plasma compared to young adult rats, which was associated with increased activity and content of NSMase, while ASMase activity and levels in the hippocampus were decreased. Excessive accumulation of Cer and its derivative S1P, particularly in the hippocampus, is associated with neurodegeneration, inflammation and apoptosis, which are hallmarks of age-related neurological disorders. Dysregulation in the metabolism of Cer and SM, which are key components of SL signaling, can accelerate the aging process and trigger neurodegeneration, inflammation, and apoptosis [

11]. Our results are partly in agreement with the report of Babenko et al.[

23], who reported that 24-month-old rats had increased Cer content and Cer/SM ratio in the hippocampus and neocortex compared to 3-month-old rats. Furthermore, these changes were associated with increased NSMase, but not ASMase activity. The cellular Cer can be generated by the hydrolysis of SM catalyzed by SMases. If ASMase activity decreases, it could reduce the production of Cer under acidic conditions. This reduction could counterbalance the amount of Cer generated by NSMase and prevent its overproduction in the aging brain. Therefore, reduced activity of ASMase could be suggested to have an indirect protective effect on the hippocampus by preventing the overproduction of Cer that is under NSMase control in aging. Conversely, activated NSMase leading to elevated Cer levels can induce apoptosis and inflammation, disrupt membrane integrity and signaling pathways critical for cellular functions [

24], and can disrupt the balance between endogenous antioxidant molecules such as glutathione and hence the production of free radicals during metabolic activity [

25].

Aging is associated with a decrease in glutathione (GSH) levels, leading to OS and activation of NSMase, which hydrolyzes SM to Cer [

26]. Chronic inflammation and oxidative damage in the aging brain further enhance NSMase activity. Aging-associated metabolic and inflammatory stress may enhance

de novo Cer synthesis from serine and palmitoyl-CoA. This pathway may become overactive in response to insulin resistance or mitochondrial dysfunction, both of which are common in aging. Therefore, our results indicate that NSMase plays a critical role in the elevation of Cer and increase in SM content in the hippocampus of aged rats. In aged brains, OS potentiates NSMase activity and enhances this effect. Other potential mechanisms that could stimulate the accumulation of Cer and SM in the hippocampus of aged rats could be related to a disrupted (upregulated)

de novo pathway for Cer synthesis due to cellular stress and chronic inflammation, which are common in the aging brain. The hippocampus is particularly sensitive to Cer-induced neurotoxicity, affecting memory and learning, and our preliminary data confirmed that old rats showed decreased cognitive capacity [

27]. While Cer accumulation is more commonly associated with aging, increased SM levels have also been reported as a potential compensatory response to elevated Cer by converting Cer back into SM [

28]. Dysregulated NSMase activity in the plasma in our case could lead to inefficient degradation of SM, contributing to its accumulation. Elevated levels of SM can stiffen cellular membranes, interfering with vesicular trafficking and receptor signaling. Excess SM may compete with other phospholipids, disrupting lipid homeostasis and membrane integrity. And finally, the aberrantly high level of total brain SM is a key pathological event leading to neurodegeneration [

29].

We found that age-related deterioration of SL turnover could be exacerbated by pinealectomy-induced melatonin deficiency in young adult rats with overproduction of Cer in the hippocampus. However, this effect was not associated with a proportional change in NSMase (increased level) or ASMase (decreased activity and/or level). This discrepancy could be explained by the fact that NSMase level but not its activity was measured in the hippocampus, which is a limitation factor of this study. In addition, endogenous melatonin is known to be a potent scavenger of OS-related molecules[

30], and in this regard we previously reported that pinealectomy increased lipid peroxidation in the hippocampus of 3-month-old rats and decreased superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity during the dark phase compared to the corresponding sham rats[

31]. The increased OS resulting from pinealectomy at this age period may be a result of the increased Cer production found in the present study.

Curiously, we found that the level of Cer in the hippocampus of middle-aged rats with pinealectomy was decreased compared to the corresponding sham group. In addition, while the level of NSMase was also reduced, the level of ASMase was restored in the hippocampus of 14-month-old pinealectomized rats compared to sham rats of the same age. This result was unexpected considering our previous report showing that this age period is the most susceptible to OS in the hippocampus as a consequence of pinealectomy [

32]. As in young adult rats, pinealectomy in middle-aged rats had a devastating effect on liver markers (ALAT and ASAT), heat shock protein 70 in the frontal cortex [

22], spatial working memory, and expression of BDNF and its receptor TrkB [

27]. Moreover, we recently reported that only at this stage, SM levels in the hippocampus were decreased as a result of pinealectomy compared to the matched control [

32]. Importantly, we also found that melatonin deficiency in 14-month-old rats is associated with disturbed antioxidant/oxidant balance in rat hippocampus with decreased GSH and increased lipid peroxidation. Notably, young adult and old rats with pinealectomy were not affected. It appears that endogenous melatonin in mature rats plays a critical role in mitigating free radical production by promoting GSH production. Furthermore, OS-induced changes in the hippocampus resulted in reduced SM levels in the same structure. A previous study demonstrated that the mechanism underlying the antidepressant activity of melatonin is related to suppression of Cer accumulation, possibly via inhibition of SM metabolism [

7].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.T. and R.T.; methodology, I.G. and R.T.; software, J.T. and I.G.; validation, R.T., J.T. and I.G.; formal analysis, J.T., I.G.; T.V. and S.A.; investigation, R.T., J.T., I.G.; T.V. and S.A.; resources, J.T. and R.T.; data curation, J.T., R.T. and I.G.; writing—J.T.; writing—review and editing, J.T. and R.T.; project administration, J.T.; funding acquisition, J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

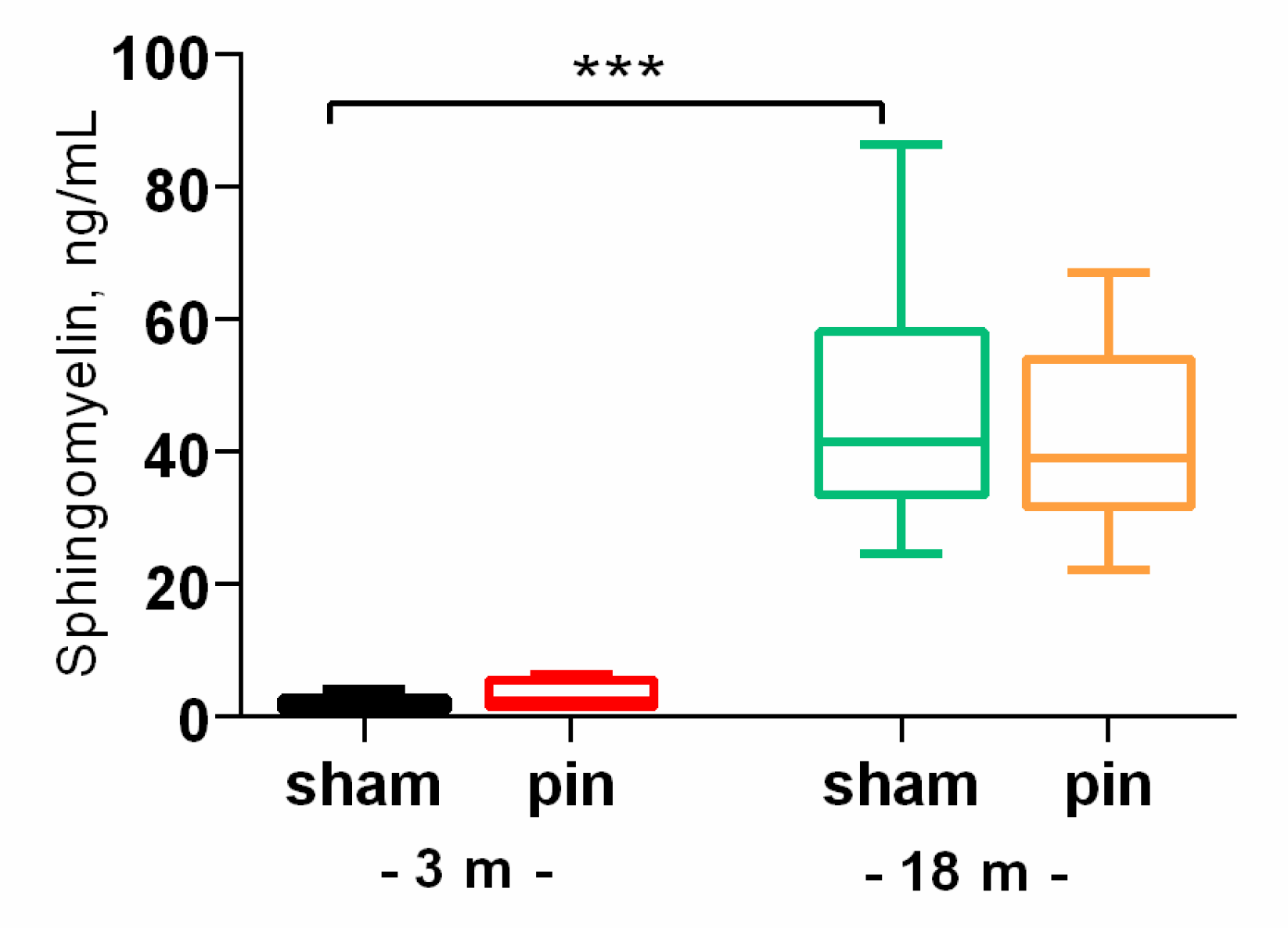

Figure 1.

The effect of pinealectomy on sphigomielin (SM) content in the hippocampus in 3- and 18-month old rats. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA indicated a major Age effect [F1,23 = 60.919, p < 0.001]; *p < 0.001, 18- vs 3-month-old sham rats. 3 m results are published in Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2809.

Figure 1.

The effect of pinealectomy on sphigomielin (SM) content in the hippocampus in 3- and 18-month old rats. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA indicated a major Age effect [F1,23 = 60.919, p < 0.001]; *p < 0.001, 18- vs 3-month-old sham rats. 3 m results are published in Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2809.

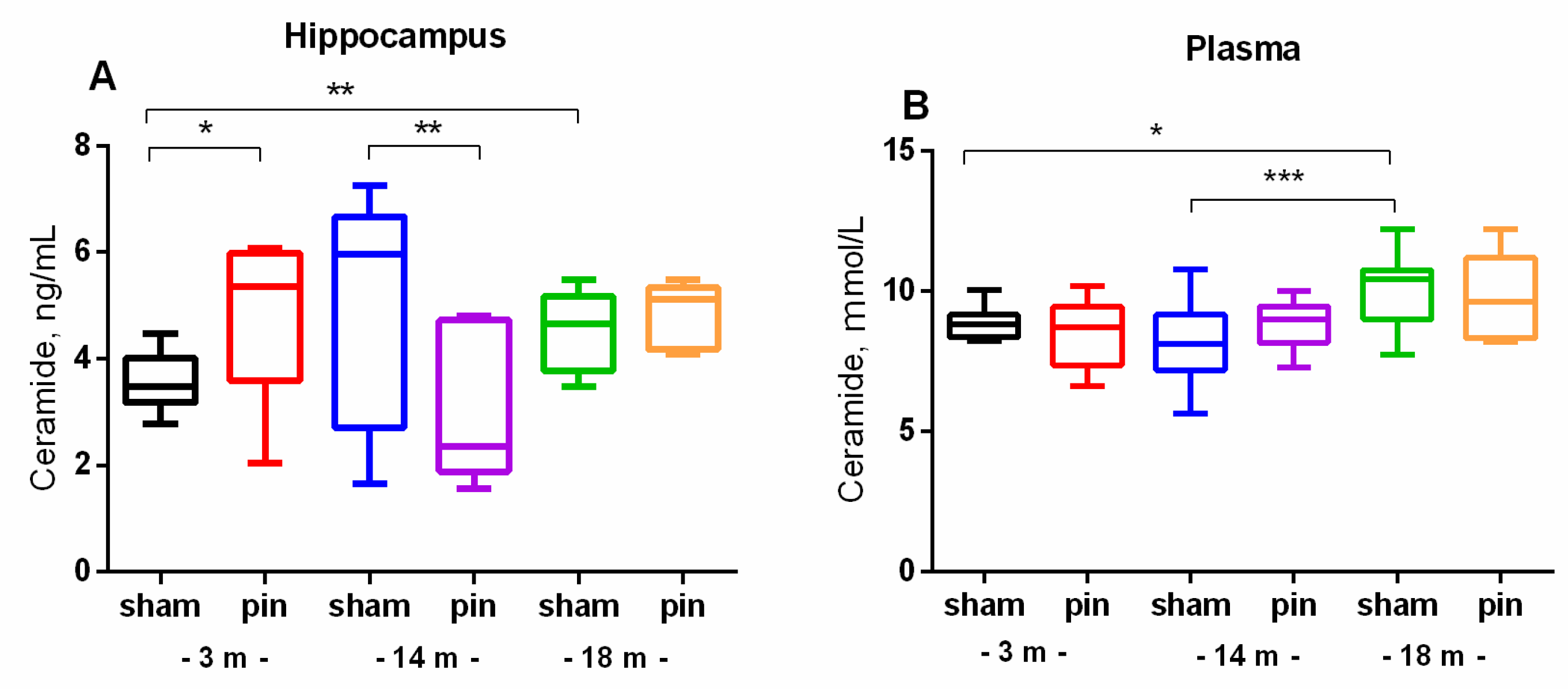

Figure 2.

The effect of pinealectomy on ceramide (Cer) content in the hippocampus and plasma in 3-, 14- and 18-month old rats. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA indicated Age x Surgery interaction [F2,45 = 6.915, p = 0.003] for the hippocampus; *p = 0.01, 18- vs 3-month-old sham rats; *p = 0.036, 3-month-old pin vs sham rats; **p = 0.006, 14-month old pin vs sham rats (A). For plasma a major Age effect [F2,52 = 3.217, p = 0.049] have been detected; *p = 0.042, 18- vs 3-month-old sham rats; ***p < 001, 18- vs 14-month-old sham rats.

Figure 2.

The effect of pinealectomy on ceramide (Cer) content in the hippocampus and plasma in 3-, 14- and 18-month old rats. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA indicated Age x Surgery interaction [F2,45 = 6.915, p = 0.003] for the hippocampus; *p = 0.01, 18- vs 3-month-old sham rats; *p = 0.036, 3-month-old pin vs sham rats; **p = 0.006, 14-month old pin vs sham rats (A). For plasma a major Age effect [F2,52 = 3.217, p = 0.049] have been detected; *p = 0.042, 18- vs 3-month-old sham rats; ***p < 001, 18- vs 14-month-old sham rats.

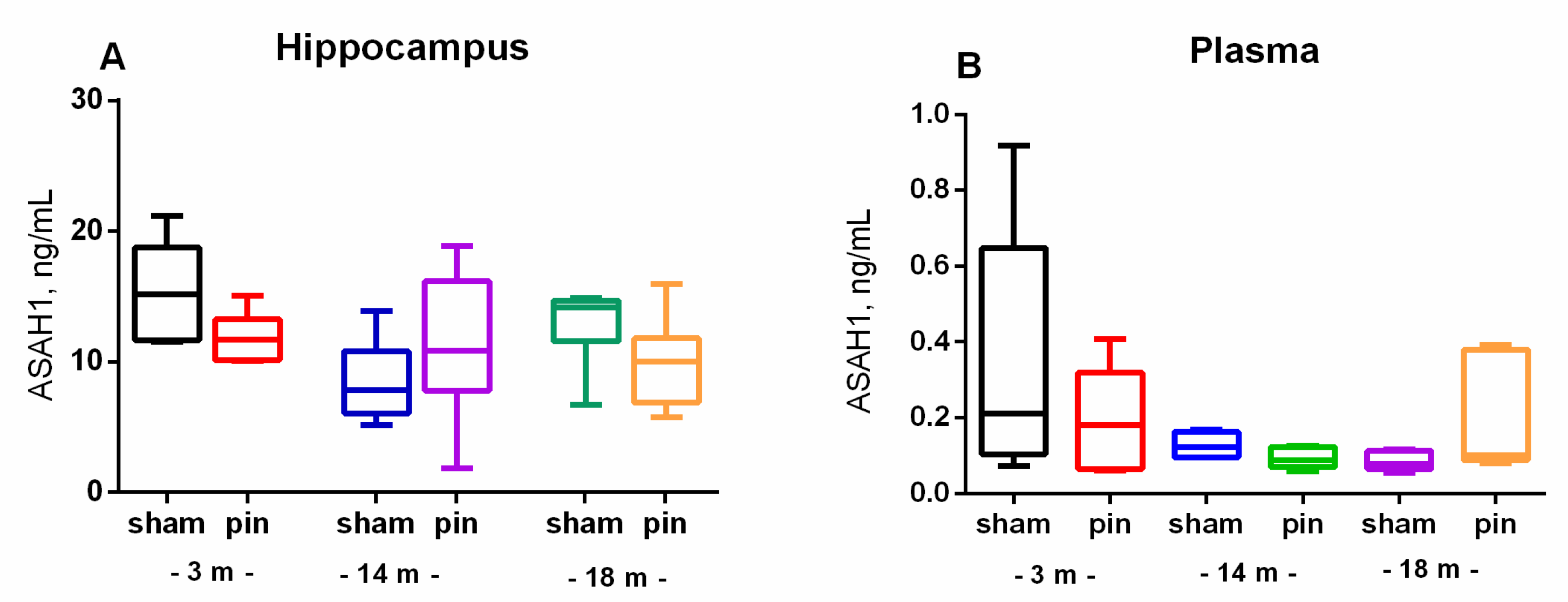

Figure 3.

The effect of pinealectomy on acid ceramidase (ASAH1) content in the hippocampus and plasma in 3-, 14- and 18-month-old rats. Data are presented as mean ± SEM2.3. Melatonin deficiency had beneficial effect on age-associated changes of NSMase and ASMase in the hippocampus only in the middle-aged rats.

Figure 3.

The effect of pinealectomy on acid ceramidase (ASAH1) content in the hippocampus and plasma in 3-, 14- and 18-month-old rats. Data are presented as mean ± SEM2.3. Melatonin deficiency had beneficial effect on age-associated changes of NSMase and ASMase in the hippocampus only in the middle-aged rats.

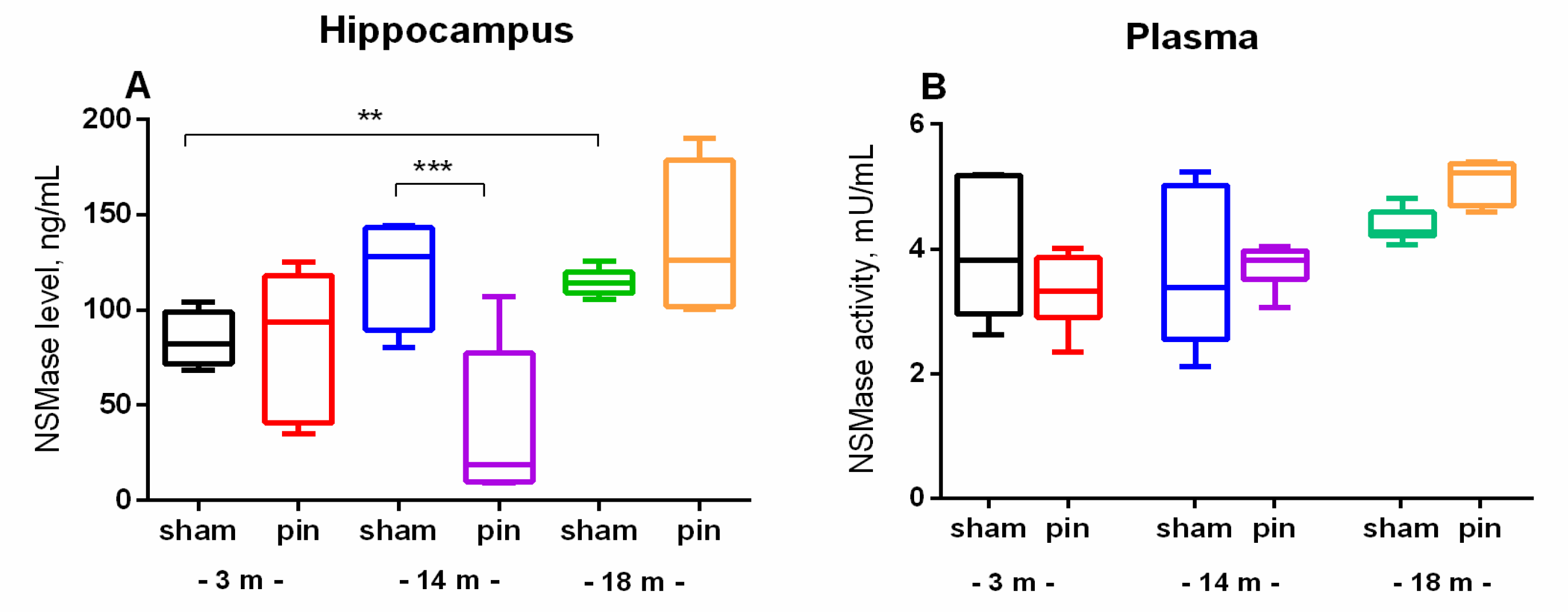

Figure 4.

The effect of pinealectomy on NSMase levels in the hippocampus and NSMase activity in plasma in 3-, 14- and 18-month old rats. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA indicated a main Age effect: [F2,35 = 5.496, p = 0.012] as well as Age x Surgery interaction: [F2,35 = 6.267, p = 0.007] for the NSMase level in the hippocampus; **p = 0.01, 18-month-old sham vs 3-month-old sham; ***p < 0.001, 14-month-old pin vs sham rats.

Figure 4.

The effect of pinealectomy on NSMase levels in the hippocampus and NSMase activity in plasma in 3-, 14- and 18-month old rats. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA indicated a main Age effect: [F2,35 = 5.496, p = 0.012] as well as Age x Surgery interaction: [F2,35 = 6.267, p = 0.007] for the NSMase level in the hippocampus; **p = 0.01, 18-month-old sham vs 3-month-old sham; ***p < 0.001, 14-month-old pin vs sham rats.

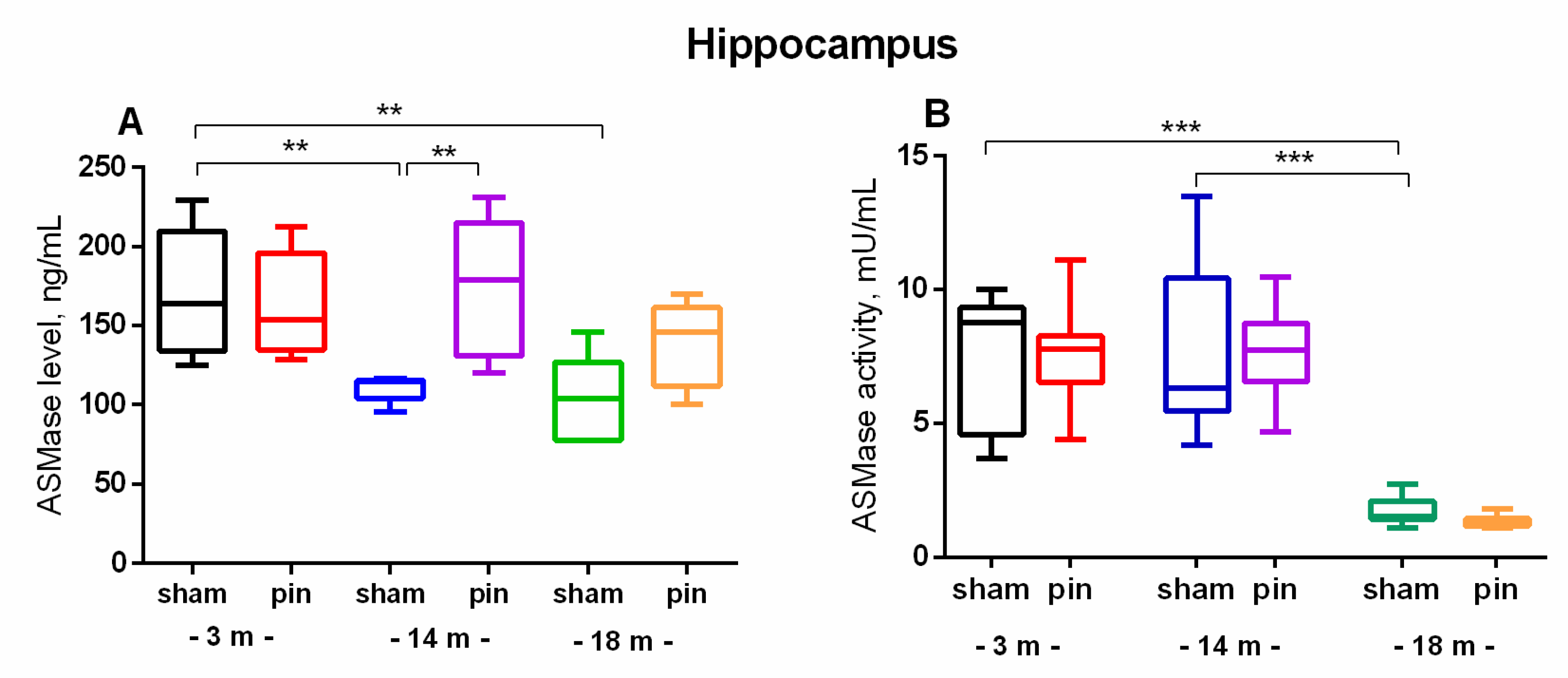

Figure 5.

The effect of pinealectomy on ASMase level (A) and activity (B) in the hippocampus in 3, 14- and 18-month-old rats. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA indicated a main age effect [F2,35 = 6,584, p = 0,003], surgery effect [F1,46 = 7,223, p = 0,010] for ASMase level; **p = 0.002, 14-month-old sham rats vs 3-month-old sham rats; **p = 0.005, 18-month-old sham rats vs 3-month-old sham rats (A). Two-way ANOVA showed a major age effect for the ASMase activity: F2,45 = 647.244, p < 0.001], ***p < 0.001, 18-month-old sham rats vs. 3- and 14-month-old sham rats (B). 2.4. Melatonin Deficiency Exacerbates Age-Related Increase in S1P.

Figure 5.

The effect of pinealectomy on ASMase level (A) and activity (B) in the hippocampus in 3, 14- and 18-month-old rats. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA indicated a main age effect [F2,35 = 6,584, p = 0,003], surgery effect [F1,46 = 7,223, p = 0,010] for ASMase level; **p = 0.002, 14-month-old sham rats vs 3-month-old sham rats; **p = 0.005, 18-month-old sham rats vs 3-month-old sham rats (A). Two-way ANOVA showed a major age effect for the ASMase activity: F2,45 = 647.244, p < 0.001], ***p < 0.001, 18-month-old sham rats vs. 3- and 14-month-old sham rats (B). 2.4. Melatonin Deficiency Exacerbates Age-Related Increase in S1P.

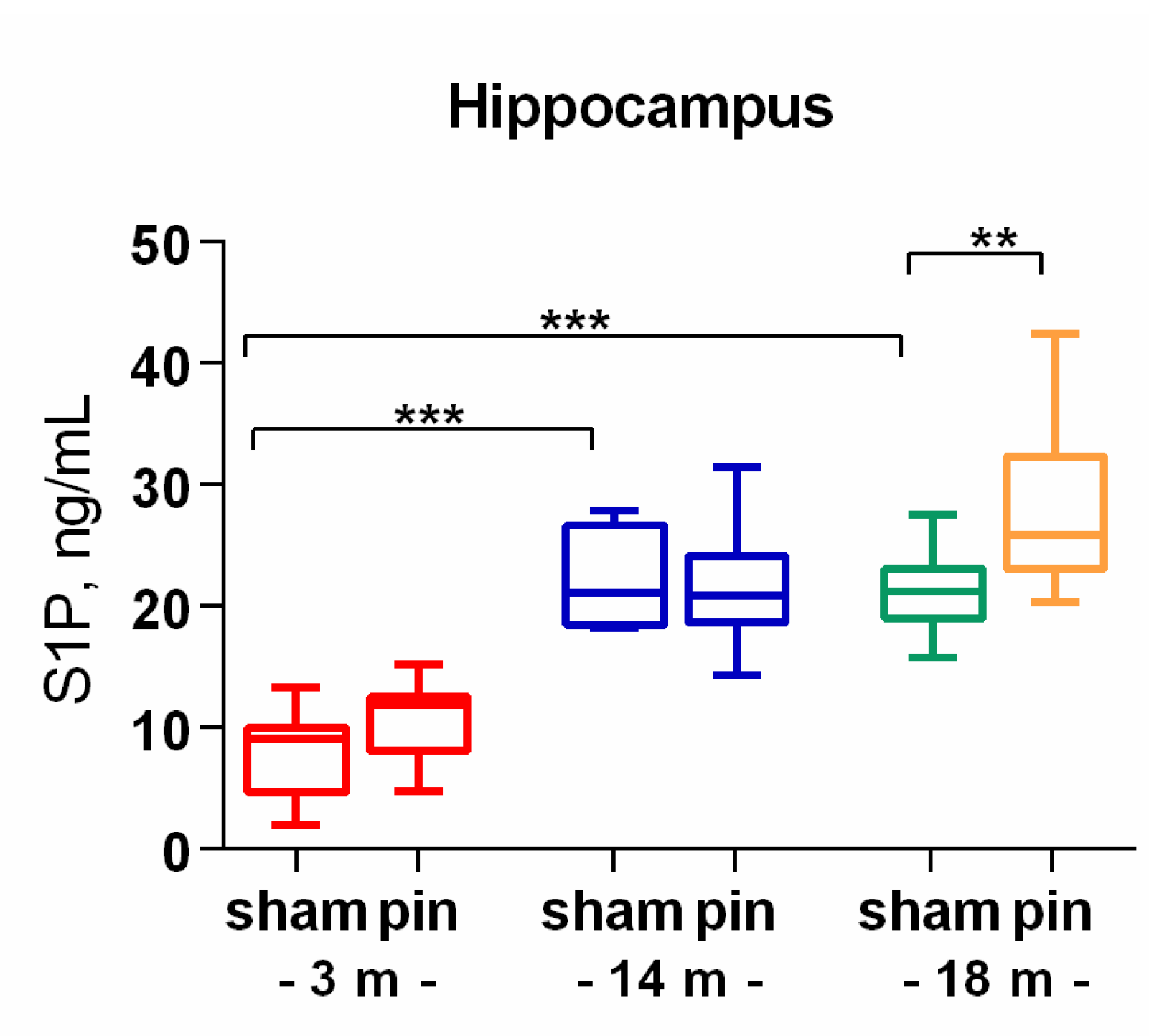

Figure 6.

The effect of pinealectomy on Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) level in the hippocampus in 3-, 14- and 18-month old rats. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA indicated a main Age effect [F2,35 = 47,73, p < 0,001], Surgery effect [F1,35 = 4,99, p = 0,05], ***p < 0.001, 14- and 18-month-old sham rats vs. 3-month-old sham rats; **p = 0.007, 18-month-old pin rats vs. 18-month sham rats.

Figure 6.

The effect of pinealectomy on Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) level in the hippocampus in 3-, 14- and 18-month old rats. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA indicated a main Age effect [F2,35 = 47,73, p < 0,001], Surgery effect [F1,35 = 4,99, p = 0,05], ***p < 0.001, 14- and 18-month-old sham rats vs. 3-month-old sham rats; **p = 0.007, 18-month-old pin rats vs. 18-month sham rats.