1. Introduction

The process of aging in the male reproductive system occurs with reduced levels of androgens because of changes in the organs of the reproductive tract, and not secondary to the increased incidence of diseases or deviations in the hypothalamic-pituitary axis during this process [

1,

2,

3]. According to some authors, the reasons for this are several external events affecting steroidogenesis in Leydig cells (LC), such as weight gain, smoking, and decreased physical activity [

4]. Other authors also discuss a series of intracellular mechanisms (reduced activity of steroidogenic enzymes and some markers of functional maturity) in the steroid-producing elements of the testis during aging [

5].

The role of the “biological clock” responsible for the correct and consistent course of the genetically determined program of life is attributed to the pineal gland. There is a numerous data for a precisely regulated program of growth, development, aging and death in the pineal gland [

6]. The pineal gland is the endocrine gland that produces melatonin. This biologically active substance has multiple effects - anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anticoagulant properties, protects the endothelium of blood vessels, which determines its use for therapeutic purposes [

7].

The role of melatonin has also been studied in relation to the processes of reproduction. Its suppressive effect on the secretion of the two gonadotropic hormones by the adenohypophysis - luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) is well known. Thus, melatonin also regulates testicular function by influencing the male hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis [

8,

9]. Direct action of melatonin on the testicular parenchyma has also been described, where melatonin receptors have been identified [

5,

9]. The effect of melatonin on LCs is related to its role as a local modulator of steroidogenesis, and its participation in the sperm cell maturation and differentiation is discussed. The above-mentioned data are indicative of the regulatory role of melatonin in terms of testicular functions and its active participation in the processes of spermatogenesis and steroidogenesis [

10].

During the cell life cycle, Cyclin D1 regulates some growth factors, and its direct interaction with androgen receptors also acts as a co-activator of nuclear receptors. This makes it an indirect regulator of hormone-sensitive tissues, including the testicular parenchyma [

11]. Its role as a marker of cell proliferation and differentiation in the spermatogenic epithelium of the testis is also debatable [

12]. Any suppression of Cyclin D1 expression induces cell cycle arrest of different populations of germ cells and Sertoli cells and stops steroidogenesis in the testis [

13,

14].

The tumour suppressive protein Bcl6 inhibits transcription and modulates DNA damage. It also plays an important role in apoptosis during normal spermatogenesis and steroidogenesis and in response to DNA damage [

15]. Its role in sperm apoptosis has been described [

16]. Bcl6 has also been the subject of research as a factor in the stabilization and protection of spermatocytes subjected to stress-induced apoptotic changes [

15]. All these data could determine Cyclin D1 and Bcl6 as probable markers for the occurrence of apoptotic manifestations in the steroid-producing cells of the testis and in the spermatogenic testicular epithelium. So far, the direct role of melatonin on the testicular parenchyma and its influence on the apoptotic manifestations has not been sufficiently studied.

In recent years, several peptides have been the subject of intensive research, united in a group of so-called neurotrophic factors. Neurokinin A, Neurokinin B and Substance P (SP) are members of the tachykinin family and exert their effect through G protein-coupled receptors - NK1, NK2 and NK3. They are considered as neuropeptides, as they are mainly found in the central and peripheral nervous system, as well as in LCs and Sertoli cells of the testis [

17]. It is interesting in their role as modulators of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis (Neurokinin B), by influencing the release of gonadotropins or directly on steroidogenesis.

Due to these characteristics and the lack of in-depth research on the subject, the expression of tachykinins in the testis in experimental animals with removed pineal gland would be interesting. Pinealectomy would eliminate its antigonadotrophic effect, and it is already known that this lowers the concentration of testicular LH receptors [

18].

Neurotrophic factors have been found to be signalling molecules controlling neuronal differentiation, survival, and synaptic plasticity [

19]. In addition, evidence reveals additional functional activities of these molecules in a number of non-neuronal cells and tissues [

20,

21]. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) shows a similar structural and functional identity with the NGF gene family of neurotrophins [

20,

22]. BDNF interacts with a membrane protein belonging to the tyrosine kinase (trk) receptor family, trkB [

20]. BDNF and its specific receptor, trkB, have been the subject of many years of research because of their role in neuronal development and proliferation. [

23,

24]. The role of the BDNF/trkB signalling system as autocrine regulators of the cascade mechanisms of steroidogenesis is also investigated [

25]. In our previous works we have demonstrated that human LCs and rat LCs are distinguished by a pronounced expression of the components of the neurotrophins signalling system. The expression of these molecules in fetal and mature LCs appears to support the hypothesis that neurotrophins produced and/or acting on LCs are involved in the process of their differentiation and functional activity [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

The effect of melatonin on testicular morphology and function is not well understood, and studies in an experimental model of pinealectomy are isolated. Based on our long-term experience we aim to investigate the potential role of melatonin in the aging process by studying its effect on the expression of oxidative stress markers of the proteins Cyclin D1 and Bcl6, the neurotrophins ligand-receptor system BDNF/trkB, Neurokinin B, Substance P in the testis in a model of melatonin deficiency.

2. Materials and Methods

Experimental animals. In the present study we used male Wistar rats, bred under standard conditions: 21 1o C, 50-60% humidity and artificial lighting regime. Two groups of rats (n=8) – control rats and rats with removed pineal gland, will be operated on in three separate age categories: 1) mature, 5 months; 2) adults, 15 months and 3) old, 20 months. Two months later, the animals are decapitated by guillotine after anaesthesia with CO2 and tissue material (testis) is taken to carry out the planned tests.

The experiments in the present study were performed in complete agreement with the European Communities Council Directive 2010/63/E.U. Animal experiments were approved by the research project (# 300/N◦5888–0183/04.21) of the Bulgarian Food Safety Agency.

Experimental model of pinealectomy

After anaesthesia with isoflurane (2.5 %), the rats were fixed on a stereotactic apparatus and underwent an epiphysiotomy, according to the methodology described by Hoffman and Reiter (1965)[

31] and routinely applied by the team at the Institute of Veterinary Medicine [

31,

32,

33].

Immunohistochemistry

We use rat testicular fragments, on which we apply a immunohistochemical technique from the combination of ABC and PAP methods on paraffin sections (5-6 μm) and ImmunoCruz mouse ABC staining system (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., USA). with diaminobenzidine (DAB) as a chromogen. Immunoreactivity on paraffin sections begins with dewaxing with xylene and absolute alcohol. This is followed by inhibition of peroxidase with a solution of methanol and hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes. We continue the dewaxing with 96º, 80º and 70º alcohol and finish with distilled water. This is followed by a stay in PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline) for 15 minutes and in a blocking, serum dissolved in PBS for 60 minutes. Then incubation with a specific antibody is carried out and a stay at 4º in a humid chamber for one night. This was followed by washing with PBS and staying with a biotinylated secondary antibody (dissolved 1:100) for 1 hour at room temperature. This stage is followed by washing in PBS and incubating with an AB reagent for 30 minutes. Peroxidase activity is demonstrated using a solution containing substrate buffer (0.1M PB with a pH of 7.4), 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB)-4 HCL and a peroxidase substrate. The duration of incubation is different (5-25 minutes), according to the rate of manifestation of peroxidase activity, which is tracked under a microscope. The final stages are flushing the sections with PBS, dehydration with an ascending alcohol battery and covering with a Veсtamount (Vector, USA). The specificity of immunostaining is demonstrated using control sections in which the primary or secondary antibody is replaced by phosphate buffer or only peroxidase activity is visualized.

The following specific polyclonal rabbit antibodies are used: anti-BDNF, anti-trkB, anti-Cyclin D1, anti-Bcl6, anti-Neurokinin B, anti-Substance P (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., USA).

Quantitative analysis of the intensity of immunohistochemical reactions

Quantitative analysis of the intensity of immunohistochemical reactions using specialized software Olympus DP-Soft image system (version 4.1 for Windows) on a Microphot-SA microscope (Nikon, Japan), equipped with a digital camera Camedia-5050Z (Olympus, Japan). The intensity values of the reactions were in the range of 0÷256, with 0 presenting -white and 256—black. The mean value of the intensity of antigenic expression for each animal in the groups was calculated, and immune expression was recorded in relative units (RU). We analysed testicles slices of experimental animals of different ages from the two study groups. The intensity of immune reactions in positive cells was calculated on different microscopic fields of slices (10 slices per animal, at magnification x400).

Statistical methods. The results obtained will be analysed with parametric (two-way ANOVA) or non-parametric analysis (Kruskal Wallis) depending on the distribution with a statistically significant difference p < 0.05. The data were presented as mean±S.E.M.

3. Results

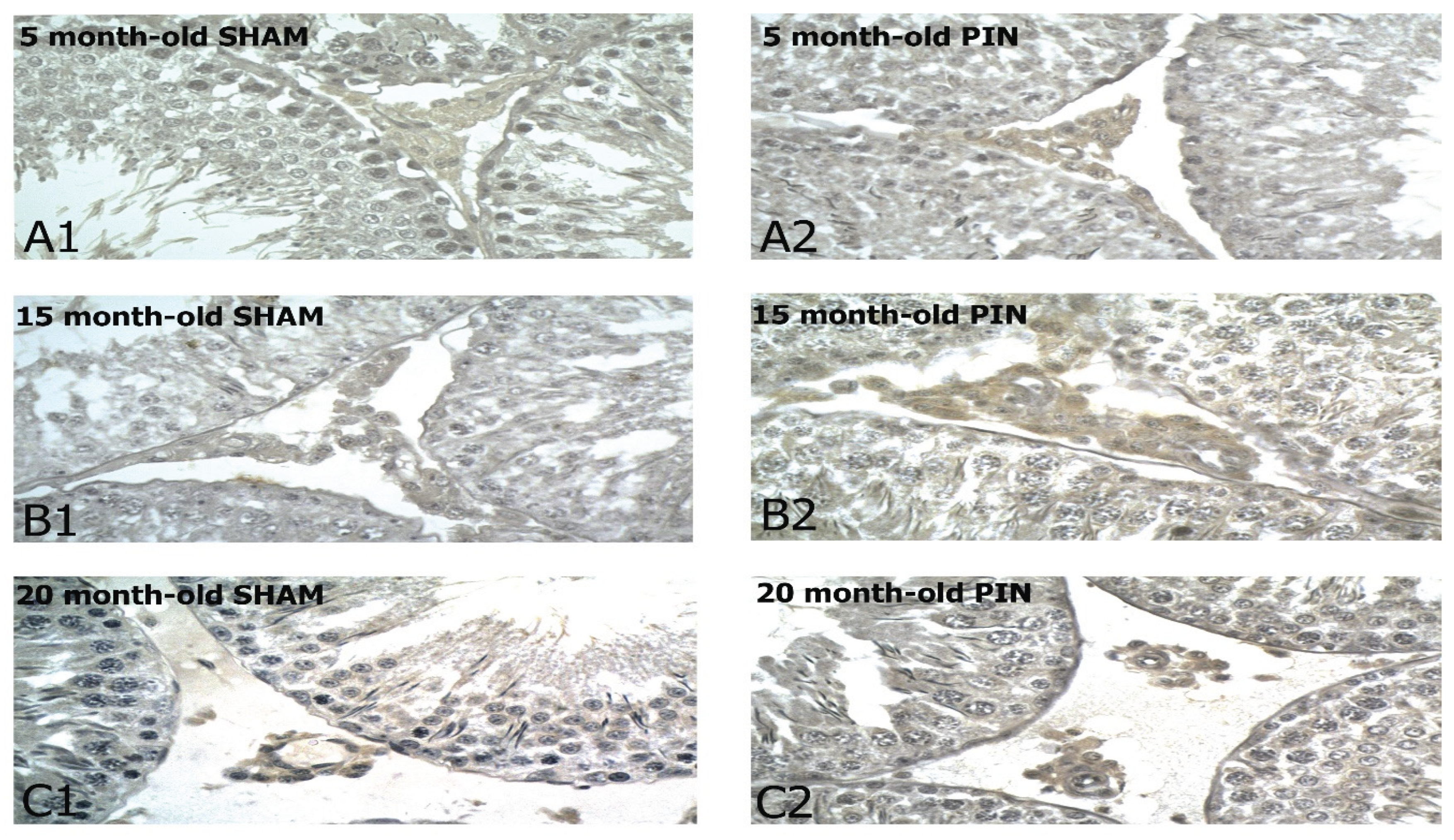

3.1. Cyclin D1 immunohistochemical expression

Representative images showing Cyclin D1 immunostaining in control group (SHAM group), as well as in the group with removed pineal gland (PIN group). The results obtained demonstrate a more pronounced immunoreactivity for Cyclin D1 in the LCs in middle-aged and adult animals with removed pineal glands, compared to the sham-group, without significant differences in its expression in young rats (

Figure 2:

p < 0.01, PIN 20 months vs. PIN 5 months;

p < 0.001 PIN 15 months vs. PIN 5 months). The changes observed correlate with age-related testicular tissue alterations- dramatically reduced spermatogenesis in the wall of the seminiferous tubules, the basal lamina of which is strongly thickened and folded; exclusively single LCs along the blood vessels in the interstitium and are almost not detected peritubularly; the blood vessels between the semiferous tubules show areas of sclerosis and hyalinosis (

Figure 1A-C). However, the expression of Cyclin D1 in the testis differed significantly within the SHAM groups tested at different ages (

Figure 2:

p < 0.001, SHAM 20 months vs. SHAM 5 months;

p < 0.001 SHAM 15 months vs. SHAM 5 months).

Figure 1.

Cyclin D1 immunoexpression in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. Immunohistochemical localization of Cyclin D1 in 5-month-old sham rats (A1), 5-month-old pin rats (A2), 15-month-old rats sham rats (B1), 15-month-old pin rats (B2), 20-month-old sham rats (C1) and 20-month-old pin rats (C2).

Figure 1.

Cyclin D1 immunoexpression in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. Immunohistochemical localization of Cyclin D1 in 5-month-old sham rats (A1), 5-month-old pin rats (A2), 15-month-old rats sham rats (B1), 15-month-old pin rats (B2), 20-month-old sham rats (C1) and 20-month-old pin rats (C2).

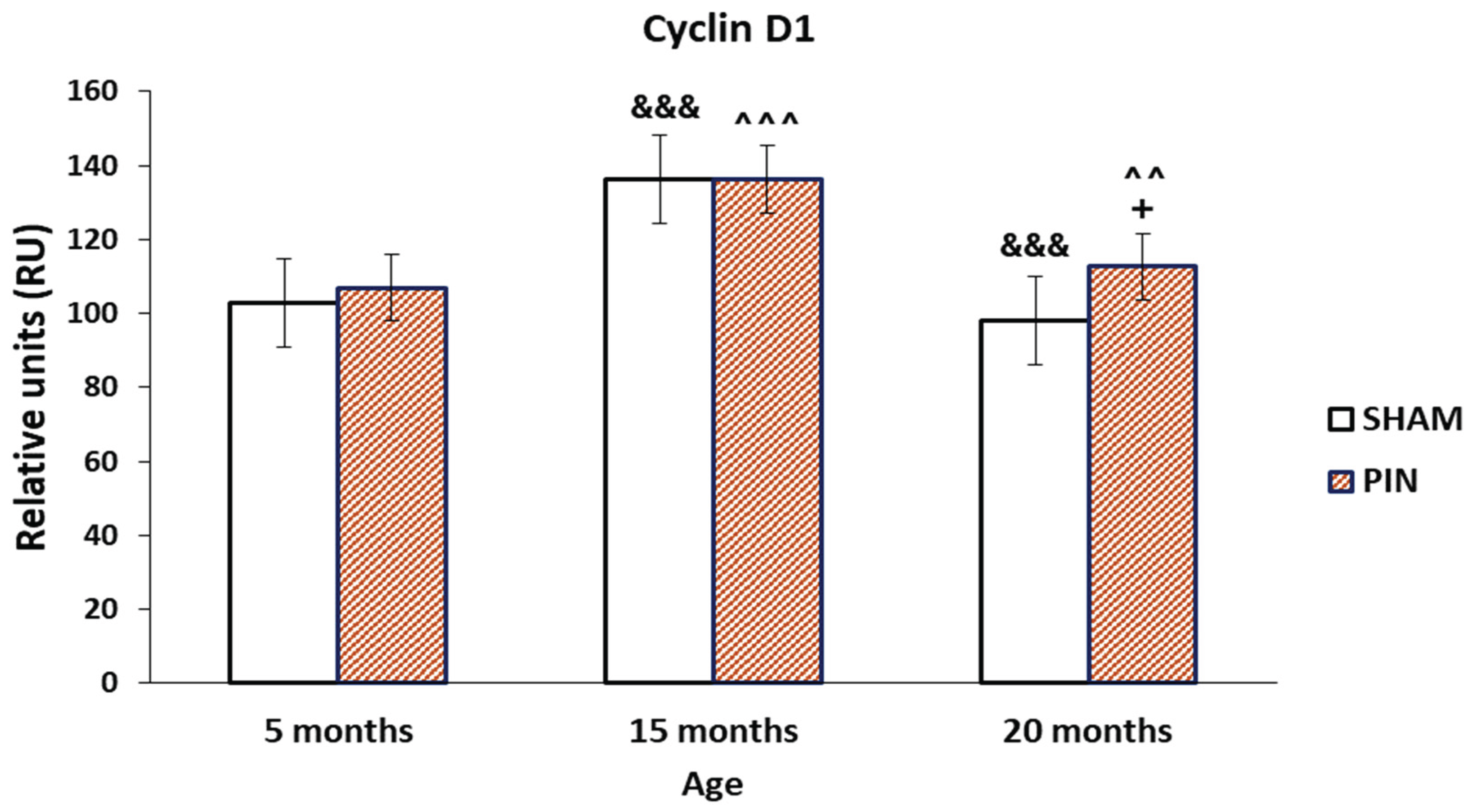

Figure 2.

Effect of pinealectomy on the Cyclin D1 levels (RU) in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. +p < 0.05 20months PIN group vs. 20 months SHAM group; &&& p < 0.001, SHAM 20 months vs. SHAM 5 months; &&& p < 0.001 SHAM 15 months vs. SHAM 5 months; ^^ p < 0.01, PIN 20 months vs. PIN 5 months; ^^^ p < 0.001 PIN 15 months vs. PIN 5 months.

Figure 2.

Effect of pinealectomy on the Cyclin D1 levels (RU) in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. +p < 0.05 20months PIN group vs. 20 months SHAM group; &&& p < 0.001, SHAM 20 months vs. SHAM 5 months; &&& p < 0.001 SHAM 15 months vs. SHAM 5 months; ^^ p < 0.01, PIN 20 months vs. PIN 5 months; ^^^ p < 0.001 PIN 15 months vs. PIN 5 months.

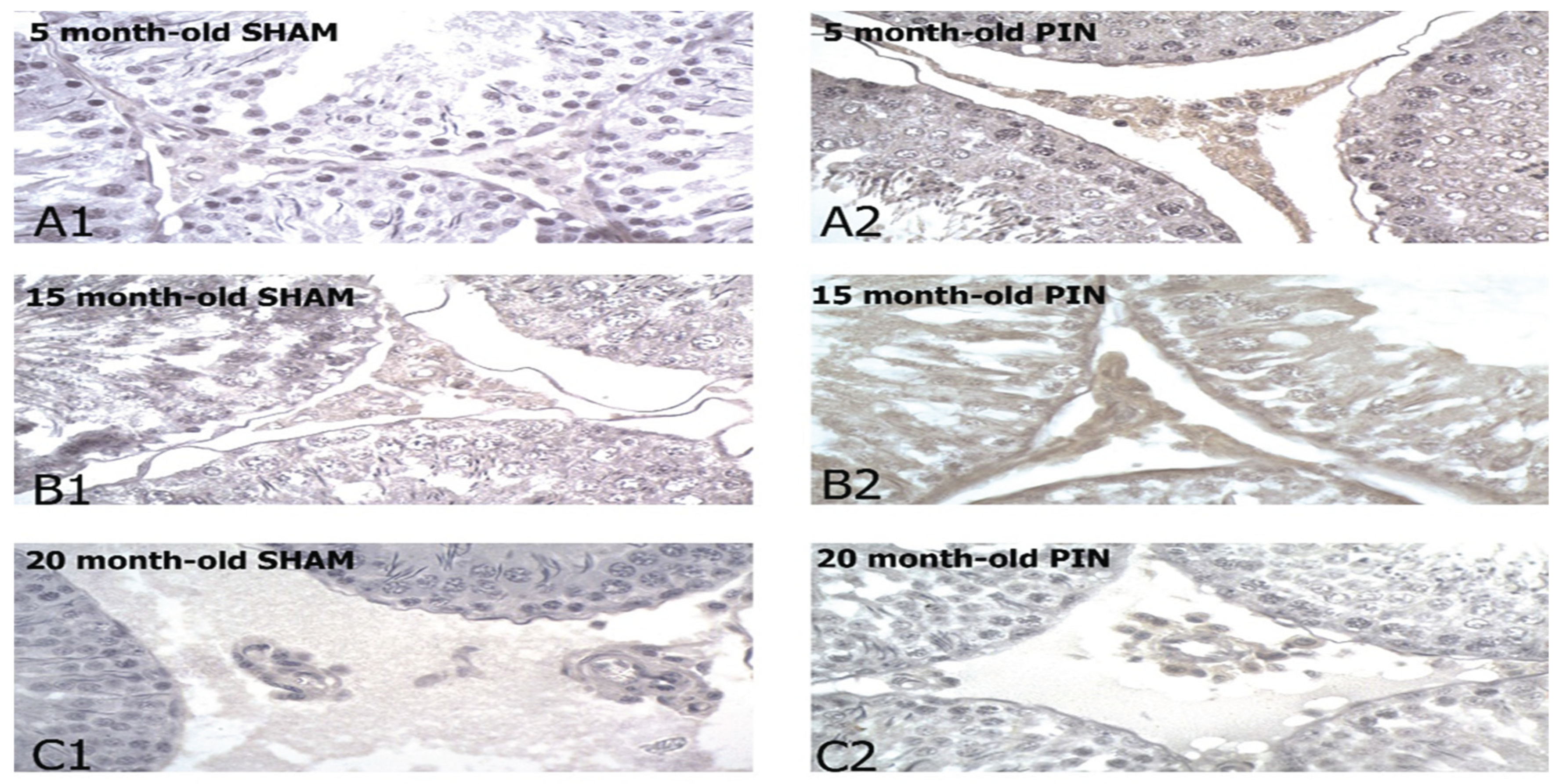

3.2. Bcl6 immunohistochemical expression

A significant improvement in Bcl6 immune reaction intensity in the LCs in animals with removed pineal glands (PIN group) was found, compared to the sham-group (

Figure 4:

p < 0.001 5 months PIN vs. 5 months SHAM;

p < 0.05 15 months PIN vs15 months SHAM;

p < 0.001 20 months PIN group vs. 20 months SHAM group), as well as highly atrophic populations of LCs in 20-month-old animals, related to the attenuating steroidogenic functions of the aging testis (

Figure 3A-C). Regarding the SHAM group, we found a reduced immune response in adult animals in the SHAM group compared to young animals in the same group (

Figure 4: p < 0.001, SHAM 20 months vs. SHAM 5 months).

Figure 3.

Bcl6 immune expression in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. Immunohistochemical localization of Bcl6 in 5-month-old sham rats (A1), 5-month-old pin rats (A2), 15-month-old rats sham rats (B1), 15-month-old pin rats (B2), 20-month-old sham rats (C1) and 20-month-old pin rats (C2). Note the increased expression for BCL6 in the young adult and middle-aged rats with removed pineal glands (B2, C2).

Figure 3.

Bcl6 immune expression in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. Immunohistochemical localization of Bcl6 in 5-month-old sham rats (A1), 5-month-old pin rats (A2), 15-month-old rats sham rats (B1), 15-month-old pin rats (B2), 20-month-old sham rats (C1) and 20-month-old pin rats (C2). Note the increased expression for BCL6 in the young adult and middle-aged rats with removed pineal glands (B2, C2).

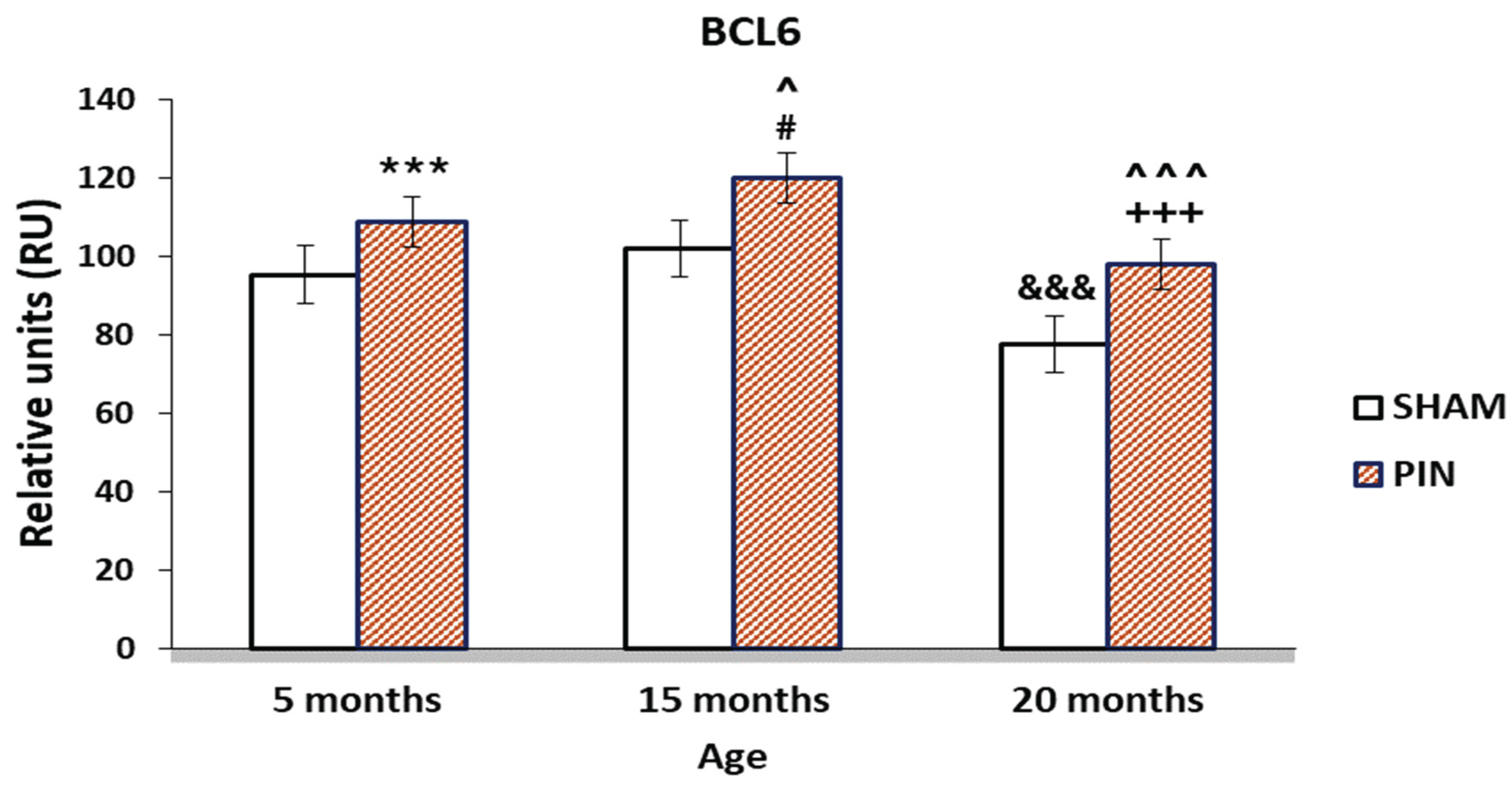

Figure 4.

Effect of pinealectomy on the BCL6 levels (RU) in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. *** p < 0.001 5 months PIN vs. 5 months SHAM; # p < 0.05 15 months PIN vs15 months SHAM; +++p < 0.001 20months PIN group vs. 20 months SHAM group; &&& p < 0.001, SHAM 20 months vs. SHAM 5 months; ^^^ p < 0.001, PIN 20 months vs. PIN 5 months; ^ p < 0.05, PIN 15 months vs. PIN 5 months.

Figure 4.

Effect of pinealectomy on the BCL6 levels (RU) in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. *** p < 0.001 5 months PIN vs. 5 months SHAM; # p < 0.05 15 months PIN vs15 months SHAM; +++p < 0.001 20months PIN group vs. 20 months SHAM group; &&& p < 0.001, SHAM 20 months vs. SHAM 5 months; ^^^ p < 0.001, PIN 20 months vs. PIN 5 months; ^ p < 0.05, PIN 15 months vs. PIN 5 months.

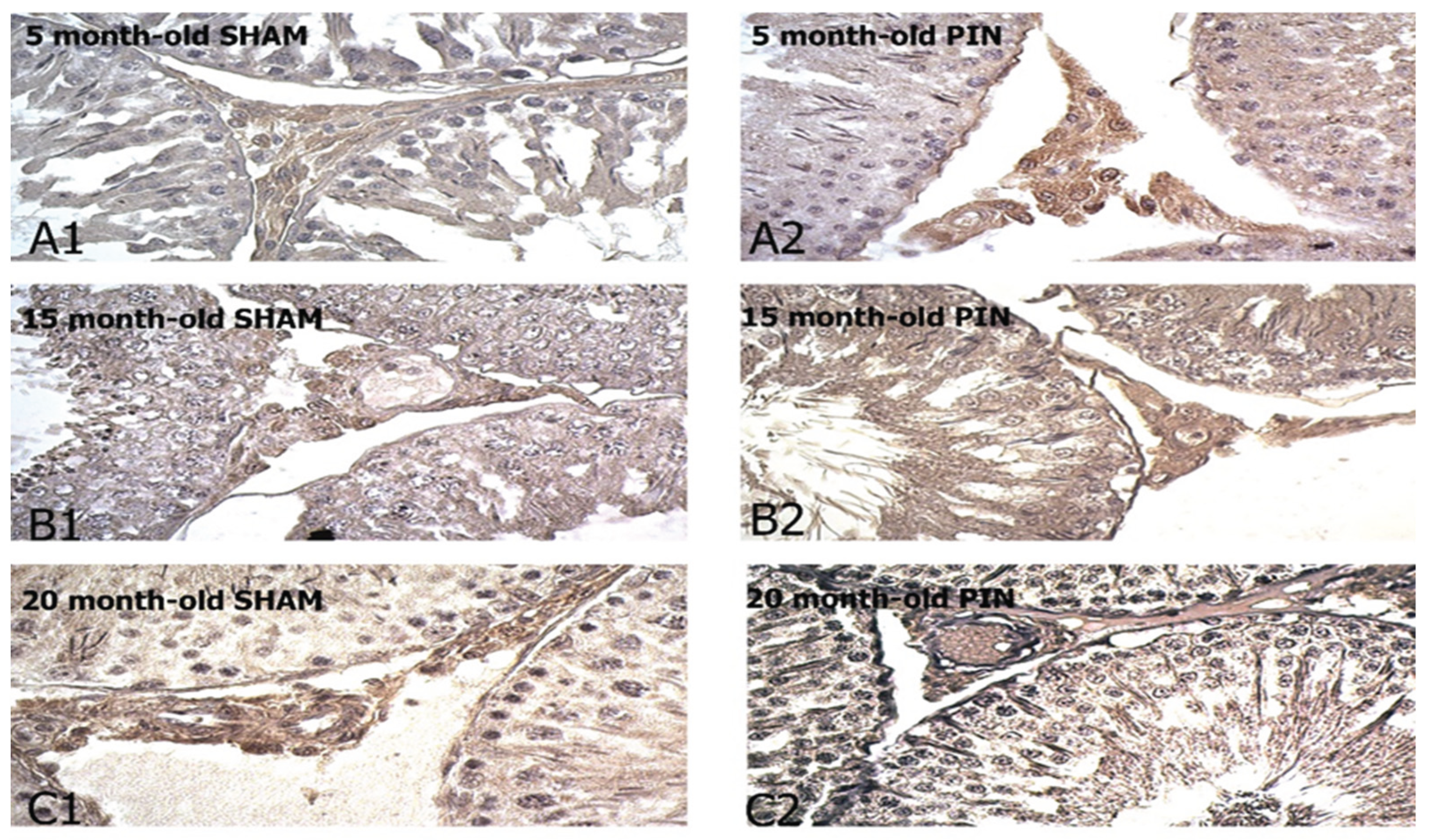

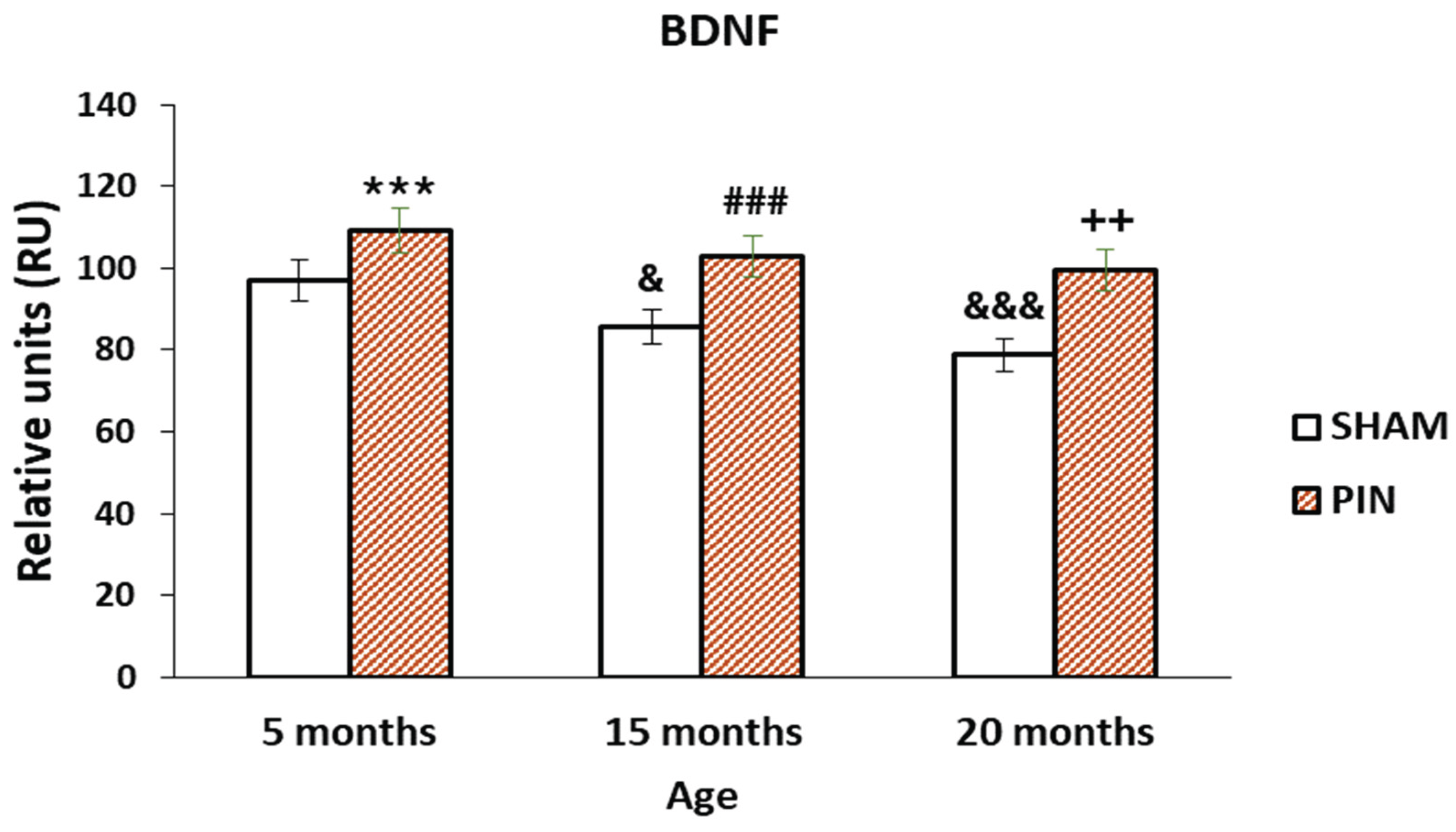

3.3. BDNF immunohistochemical expression

The more pronounced expression of BDNF in the LCs of 5 months old rats and 15 months old rats with removed pineal gland (PIN group),(

Figure 6:

p < 0.001 5 months PIN vs. 5 months SHAM;

p < 0.001 15 months PIN vs 15 months SHAM), as well as the low expression in the atrophic populations of LCs in adults 20 months old animals (PIN group), demonstrated the role of melatonin in the regulation of testicular steroidogenesis, affecting the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis (

Figure 5A-C). The expression of BDNF in the testis differed significantly within the SHAM groups tested at different ages, and a trend towards decreased expression was observed (

Figure 6:

p < 0.001, SHAM 20 months vs. SHAM 5 months).

Figure 5.

BDNF immunoexpression in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. Immunohistochemical localization of BDNF in 5-month-old sham rats (A1), 5-month-old pin rats (A2), 15-month-old rats sham rats (B1), 15-month-old pin rats (B2), 20-month-old sham rats (C1) and 20-month-old pin rats (C2).

Figure 5.

BDNF immunoexpression in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. Immunohistochemical localization of BDNF in 5-month-old sham rats (A1), 5-month-old pin rats (A2), 15-month-old rats sham rats (B1), 15-month-old pin rats (B2), 20-month-old sham rats (C1) and 20-month-old pin rats (C2).

Figure 6.

Effect of pinealectomy on the BDNF levels (RU) in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. *** p < 0.001 5 months PIN vs. 5 months SHAM; ### p < 0.001 15 months PIN vs15 months SHAM; ++p < 0.01 20months PIN group vs. 20 months SHAM group; &&& p < 0.001, SHAM 20 months vs. SHAM 5 months; & p < 0.05 SHAM 15 months vs. SHAM 5 months.

Figure 6.

Effect of pinealectomy on the BDNF levels (RU) in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. *** p < 0.001 5 months PIN vs. 5 months SHAM; ### p < 0.001 15 months PIN vs15 months SHAM; ++p < 0.01 20months PIN group vs. 20 months SHAM group; &&& p < 0.001, SHAM 20 months vs. SHAM 5 months; & p < 0.05 SHAM 15 months vs. SHAM 5 months.

3.4. Trk B immunohistochemical expression

A significant expression for TRK B in the LCs of young adult and middle-aged rats (5- and 15-months old rat) with removed pineal glands (PIN group), compared with SHAM group, as well as low expression in the LCs of adults 20 months old animals. (

Figure 7A–C and

Figure 8:

p < 0.01, 5 months PIN vs. 5 months SHAM;

## p < 0.01 15 months PIN vs15 months SHAM; ++

p < 0.01 20months PIN group vs. 20 months SHAM group). However, in the SHAM group we observed reduced Trk B expression in the course of aging (

Figure 8:

p < 0.01, SHAM 20 months vs. SHAM 5 months).

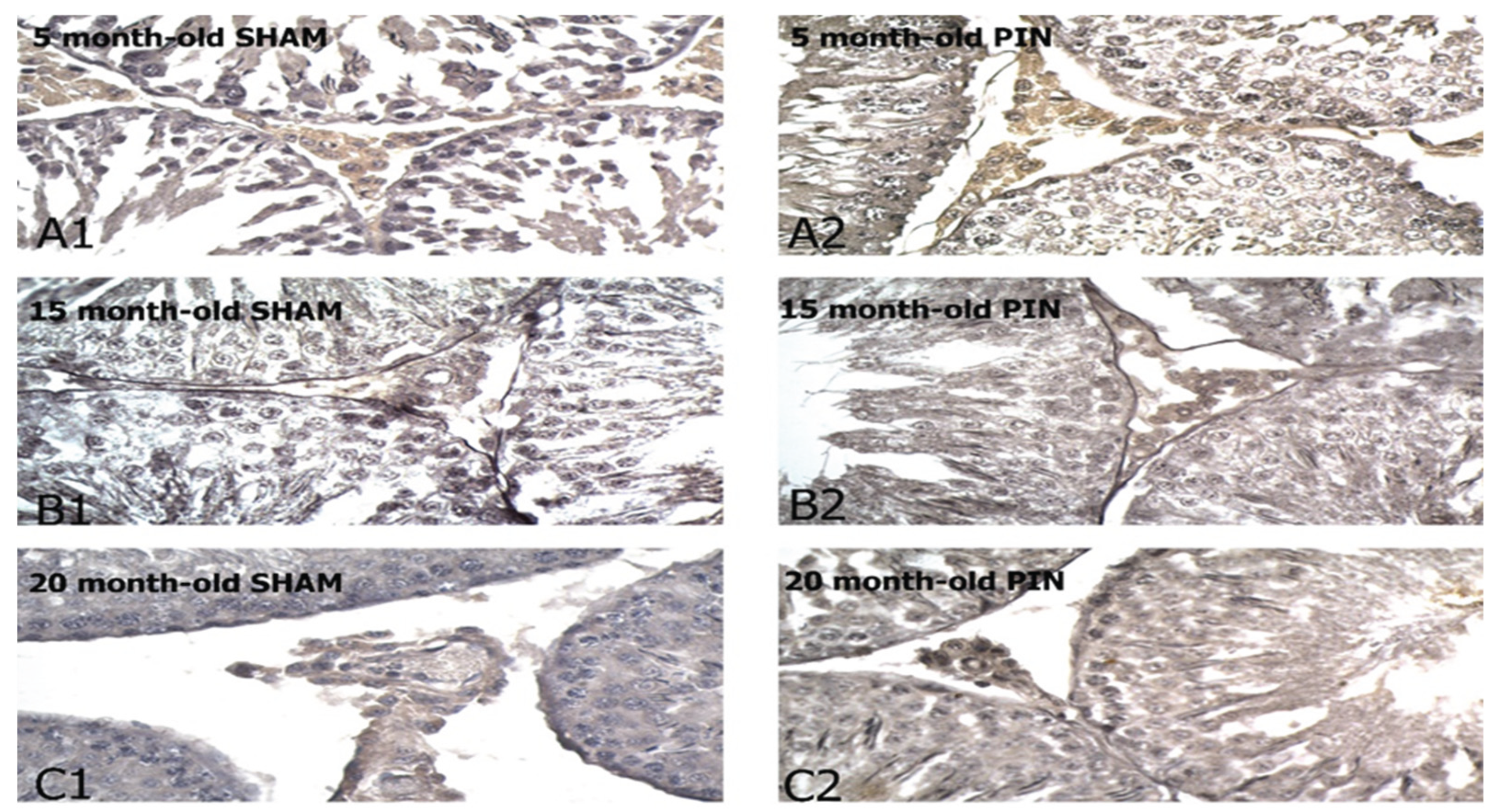

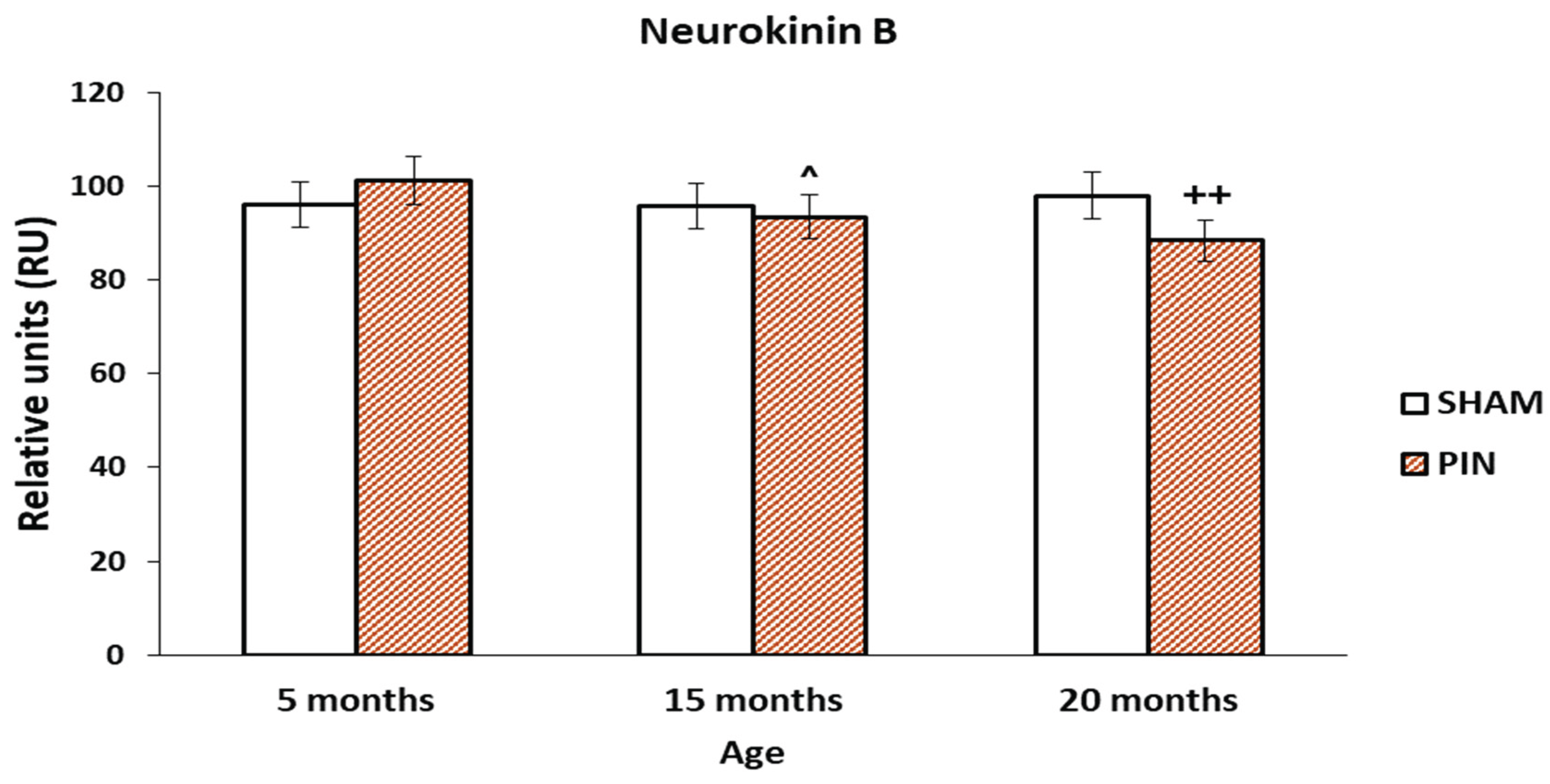

3.5. Neurokinin B immunohistochemical expression

The increased expression of Neurokinin B in LCs of young animals (5 months), without a significant difference in the two groups in young and middle-aged rats (PIN and SHAM groups). The immunoreactivity for Neurokinin B in the LCs of PIN 5-month-old animals is more intensive, compared to the PIN 15-month-old group (

Figure 10: p < 0.05, PIN 15 months vs. PIN 5 months). There is a statistically significant difference between the PIN and SHAM groups in old animals (

Figure 10: p < 0.01 20 months PIN group vs. 20 months SHAM group). The stronger expression of Neurokinin B in the LCs of adult (20-month-old) animals from the SHAM group demonstrates its possible influence on the enhanced apoptotic processes in the aging testis (

Figure 9A-C).

Figure 9.

Neurokinin B immunoexpression in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. Immunohistochemical localization of Neurokinin B in 5-month-old sham rats (A1), 5-month-old pin rats (A2), 15-month-old rats sham rats (B1), 15-month-old pin rats (B2), 20-month-old sham rats (C1) and 20-month-old pin rats (C2).

Figure 9.

Neurokinin B immunoexpression in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. Immunohistochemical localization of Neurokinin B in 5-month-old sham rats (A1), 5-month-old pin rats (A2), 15-month-old rats sham rats (B1), 15-month-old pin rats (B2), 20-month-old sham rats (C1) and 20-month-old pin rats (C2).

Figure 10.

Effect of pinealectomy on the Neurokinin B levels (RU) in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. ++p < 0.01 20 дmonths PIN group vs. 20 months SHAM group; ^ p < 0.05, PIN 15 months vs. PIN 5 months.

Figure 10.

Effect of pinealectomy on the Neurokinin B levels (RU) in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. ++p < 0.01 20 дmonths PIN group vs. 20 months SHAM group; ^ p < 0.05, PIN 15 months vs. PIN 5 months.

3.6. Substance P immunohistochemical expression

The increased expression of Substance P in the LCs of young animals (5 months) and mature (15-month-old) animals in PIN group (

Figure 12:

p < 0.05, PIN 20 months vs. PIN 5 months), points to their probable local role in active LCs proliferation. The difference between the PIN and SHAM groups in middle-aged animals is statistically significant (

Figure 12:

p < 0.05 15 months PIN vs15 months SHAM). In the LCs of adult animals (20-month-old), there is no significant difference in the two groups (PIN and SHAM groups). (

Figure 11A-C).

Figure 11.

Substantia P immunoexpression in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. Immunohistochemical localization of Substance P in 5-month-old sham rats (A1), 5-month-old pin rats (A2), 15-month-old rats sham rats (B1), 15-month-old pin rats (B2), 20-month-old sham rats (C1) and 20-month-old pin rats (C2).

Figure 11.

Substantia P immunoexpression in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. Immunohistochemical localization of Substance P in 5-month-old sham rats (A1), 5-month-old pin rats (A2), 15-month-old rats sham rats (B1), 15-month-old pin rats (B2), 20-month-old sham rats (C1) and 20-month-old pin rats (C2).

Figure 12.

Effect of pinealectomy on the Substantia P levels (RU) in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. # p < 0.05 15 months PIN vs15 months SHAM; && p < 0.01, SHAM 15 months vs. SHAM 5 months; ^ p < 0.05, PIN 20 months vs. PIN 5 months.

Figure 12.

Effect of pinealectomy on the Substantia P levels (RU) in the LCs of 5-, 15- and 20 -month- old rats. # p < 0.05 15 months PIN vs15 months SHAM; && p < 0.01, SHAM 15 months vs. SHAM 5 months; ^ p < 0.05, PIN 20 months vs. PIN 5 months.

4. Discussion

Our study aims to describe the role of some signaling molecules in the processes of spermatogenesis and steroidogenesis in aging testis in melatonin deficiency conditions. According to the previous studies on aging testis steroid-producing LCs undergo dedifferentiation themselves, which worsens their steroidogenic capacity [

34]. On the other hand, a series of intracellular mechanisms reduce the activity of steroidogenic enzymes and decrease T synthesis from the steroid-producing elements of the testis during aging [

5]. These changes cause a reduction of androgen levels and are not secondary from disturbances along the hypothalamic-pituitary axis during aging [

1,

2,

35]. In the morphological aspect, a reduction in the diameter of the seminiferous tubules, thickening of the tubular basal lamina, which shows mosaic-like degenerative changes, was found in the aging testis. At the same time, no decrease or hyperplasia of the LCs is reported, but atrophic changes in the size of their population are more often detected [

36,

37].

Furthermore, the role of the pineal gland and the melatonin produced by it has an interesting participation in the processes which occur in the aging male reproductive system. Kun Yu et al., 2018 [

10] defines melatonin as a local modulator of steroidogenesis and regulator of testicular function.

Direct action of melatonin on the testicular parenchyma has also been described, where melatonin receptors have been identified [

5,

9]. Pinealectomy causes increased activity of the LCs, significantly enlarged testicular interstitium with hypertrophic and hyperplastic LCs [

18,

38]. According to some authors, in pinealectomy, parallel to an increase in the total weight of the testis, ultrastructural changes in LCs- Golgi complex, mitochondria and smooth endoplasmic reticulum are located over a larger area, cytoplasmic secretory granules and osmiophilic bodies are observed [

39].

The involvement of melatonin as a modulator of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins in the testis and its protective role in relation to the male reproductive system is also debatable [

40]. In this regard, the theory of oxidative stress is also the subject of studies related to the modulation of aging processes, with free radicals (ROS-Reactive oxygen species) as the leading factors. ROS damage a wide range of physiological processes, including those related to the aging [

41,

42,

43]. In the testis, ROS are formed in the process of steroidogenesis and cause mitochondrial damage [

44]. Increased apoptotic manifestations are a defence mechanism of cells, when they are under condition of oxidative stress [

45]. In our previous studies, we have identified, along with a number of morphological and functional changes (activity of key steroidogenic enzymes) in steroid-producing cells in the rat testis during aging, changes in the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax factors in LCs as an indicator of their increased apoptotic tendency, as well as the triggering of the mitochondrial pathway of programmed cell death [

46,

47,

48,

49].

The proteins Cyclin D1 and Bcl6 are involved as regulators of some of the mechanisms of the apoptotic process. Cyclin D1 is the subject of research in two directions - participation in the cell life cycle and provoking apoptotic changes in major damage to the cell’s DNA [

50]. During the cell life cycle, Cyclin D1 regulates some growth factors, and its direct interaction with androgen receptors also acts as a co-activator of nuclear receptors. This makes it an indirect regulator of hormone-sensitive tissues, including the testicular parenchyma [

11]. The involvement of melatonin in the overall process of cellular apoptosis is discussed as a modulator of testicular function and steroidogenesis processes [

18]. In sync with these data our results demonstrate a more pronounced immunoreactivity for Cyclin D1 in the LCs in adult animals with removed pineal glands, compared to the sham-group, without significant differences in its expression in young rats. In this respect, Cyclin D1 can be considered as a marker of cell proliferation and differentiation in the testis [

12]. Any suppression of Cyclin D1 expression induces cell cycle arrest of different populations of germ cells and Sertoli cells and stops steroidogenesis in the testis [

13,

14].

The tumor suppressive protein Bcl6 inhibits transcription and modulates DNA damage. It also plays an important role in apoptosis during normal spermatogenesis and steroidogenesis in response to DNA damage [

15,

16]. In the present study, a significant increase in Bcl6 immune reaction intensity in the LCs in animals with removed pineal glands (PIN group) was found, compared to the sham-group, as well as highly atrophic populations of LCs in 20-month-old animals, related to the attenuating steroidogenic functions of the testis in the aging process. All these data could determine Cyclin D1 and Bcl6 as probable markers for the occurrence of apoptotic manifestations in the steroid-producing cells of the aging testis and are indicative for the potential role of the melatonin in these processes.

In recent years, several peptides have been the subject of intensive research, united in a group of so-called neurotrophic factors. Neurokinin A, Neurokinin B and Substance P (SP) are members of the tachykinin family and exert their effect through G protein [

51].

In the testis, tachykinins stimulate the secretory activity of Sertoli cells and inhibit the secretion of LCs [

17,

51]. Our results reveal increased expression of Neurokinin B in LCs of young animals and more pronounced immunoreactivity for Neurokinin B in the LCs of 15-month-old animals with removed pineal gland (PIN group), compared to the SHAM group. The stronger expression of Neurokinin B in the LCs of adult (20-month-old) animals from the SHAM group was detected. Moreover, the increased expression of Substance P in the LCs of young and mature animals with removed pineal gland (PIN group), points to their probable local role in active LCs proliferation. In the LCs of adult animals (20-month-old), the expression is more intensive in SHAM group, compared to the animals with removed pineal gland (PIN group). The results obtained support the data about the role of Neurokinin B and Substance P as a paracrine regulator of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis [

44,

52].

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) shows a similar structural and functional identity with the NGF gene family of neurotrophins [

20,

22] and has been subject of many years of research because of its role in neuronal development and proliferation. [

23]. BDNF interacts with a specific membrane protein belonging to the tyrosine kinase (trk) receptor family, trkB [

20] and exerts its effect by binding to another, low-affinity receptor p75, which is considered non-specific for the entire family of neurotrophins [

30]. In the current work we have studied the expression of BDNF/trkB signaling system in testicular steroid-producing cells during aging in melatonin deficiency conditions. We found the more pronounced expression of BDNF in the LCs of young adult and middle-aged rats with removed pineal gland (PIN group), as well as the low expression in the atrophic populations of LCs in adults 20 months old animals (PIN group). These results demonstrate the role of melatonin in the regulation of testicular steroidogenesis, affecting the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Besides that, we reveal a significant expression for trkB in the LCs of young adult and middle-aged rats (5- and 15-months old rat) with removed pineal glands (PIN group), compared with SHAM group, as well as low expression in the LCs of adults 20 months old animals. Our results are in concordance with data indicating the role of the BDNF and its specific receptor trkB as autocrine regulators of the cascade mechanisms of steroidogenesis, including significantly increase of the expression of steroidogenesis-related genes as steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) and cytochrome P450 [

24,

25].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, using a model of melatonin deficiency in aging rats, we have demonstrated specific changes in the immune expression of broad spectrum of signalling molecules such as BDNF/trkB system, members of the tachykinin family Neurokinin B and Substance P and Cyclin D1 and Bcl6, regulators of the cell life cycle and apoptosis. The results obtained are indicative for the potential role of the molecules under study in the regulation of testicular steroidogenesis during aging and the involvement of melatonin in this process.

Author Contributions

D.B., Y.K., Y.T., A.P. designed and performed the research study. K.G. and M.S.D. analyzed the data. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by project (Н.О.2/2020) to Medical University- Plovdiv. Part of the immunohistochemical reactions and photo documentation were performed at the Morphological Research Center to Scientific Research Institute of Medical University-Plovdiv.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethical guidelines for experimental work with conscious animals were followed in all tests. The study was conducted in accordance with the European Communities Council Directive 2010/63/E.U. Animal experiments were approved by the research project (# 300/N◦5888–0183/ 04.2021) of the Bulgarian Food Safety Agency and Ethical Committee on Human and Animal Experimentation of Medical University of Plovdiv (№4/10.06.2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Surampudi P., Wang C., Swerdloff R. Hypogonadism in the aging male diagnosis, potential benefits, and risks of testosterone replacement therapy. Int J Endocrinol; 2012; 625434.

- Veldhuis J., Liu P., Keenan D., Takahashi P. Older men exhibit reduced efficacy of and heightened potency downregulation by intravenous pulses of recombinant human LH: a study in 92 healthy men. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 302: 117–122. [CrossRef]

- Wei Liu., Li Du, Yinghong Cui., Caimei He., Zuping He. WNT5A regulates the proliferation, apoptosis and stemness of human stem Leydig cells via the β-catenin signaling pathway, Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2024; 81:93. [CrossRef]

- Camacho EM, Huhtaniemi IT, O’Neill TW, EMAS Group, et al. Age-associated changes in hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular function in middle-aged and older men are modified by weight change and lifestyle factors: longitudinal results from the European Male Ageing Study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;168(3):445-55. [CrossRef]

- Lu N.; Yuan H.; Jiang X.; Lei H.; Yao W.; Jia P.; Xia D. Effect of Day Length on Growth and Gonadal Development in Meishan Male Pigs. Animals; 2024, 14, 876. [CrossRef]

- Pierpaoli W., Bulian D. The pineal aging and death program: life prolongation in pre-aging pinealectomized mice., Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2005; 1057:133-44. [CrossRef]

- Gheban A., Rosca A., Crisan M. The morphological and functional characteristics of the pineal gland, Medicine and Pharmacy Reports Vol. 92 / No. 3 / 2019: 226 – 234.

- Frungieri M, Calandra R and Paola Rossi S. Local Actions of Melatonin in Somatic Cells of the Testis, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1170. [CrossRef]

- Kacar E., Tan F., Sahinturk S., Gokhan Zorlu G., Serhatlioglu I., Ozgur Bulmus O., Zubeyde Ercan Z., Haluk Kelestimur H., Modulation of melatonin receptors regulates reproductive physiology: the impact of agomelatine on the estrus cycle, gestation, offspring, and uterine contractions in rats; 2023; Physiol. Res. 72: 793-807. [CrossRef]

- Kun Y., Deng S.,Sun T., Li Y.and Liu Y. Melatonin Regulates the Synthesis of Steroid Hormones on Male Reproduction: A Review, Molecules, 2018, 23, 447.

- Shao J., Xu Z., Qian X., Liu F., Huang H. Effect of Combination Regimen of Low-dose Gossypol Acetic Acid with Steroid Hormones on Expression of Protein Kinase C alpha (PKC-α) and Cyclin D1 in Rat Testes, Journal of Reproduction & Contraception, 2012; 23(4): 199-208.

- Chakrabortya A, Singhb V, Singhb K, Rajender S. Excess iodine impairs spermatogenesis by inducing oxidative stress and perturbing the blood testis barrier, Reproductive Toxicology 96, 2020;128–140.

- Yang C., Yao C., Tian R., Zhu Z., Zhao L., Peng L., Chen H., Huang Y., Zhi E.,Yuehua G., Yunjing X., Hong W., He Z. and Li Z. miR-202-3p Regulates Sertoli Cell Proliferation, Synthesis Function, and Apoptosis by Targeting LRP6 and Cyclin D1 of Wnt/b-Catenin Signaling, Molecular Therapy: Nucleic Acids, 2019, Vol. 14.

- Azar JT., Malekia A., Mosharib S., Razib M. The effect of different types of exercise training on diet-induced obesity in rats, cross- talk between cell cycle proteins and apoptosis in testis, Gene 754, 2020, 144850.

- Kojima S., Hatano M., Okada S., Fukuda T., Toyama Y.,Yuasa S., Ito H. and Tokuhisa T. Testicular germ cell apoptosis in Bcl6-deficient mice, Development 128, 2001, 57-65. [CrossRef]

- Shaha C., Tripathi R. and Mishra D. Male germ cell apoptosis: regulation and biology, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2010; 365, 1501–1515. [CrossRef]

- Omirinde JO and Azeez IA. Neuropeptide profiles of mammalian male genital tract: distribution and functional relevance in reproduction. 2022; Front. Vet. Sci. 9:842515. [CrossRef]

- Yu K., Deng S., Sun T., Li Y. and Liu Y. Melatonin Regulates the Synthesis of Steroid Hormones on Male Reproduction: A Review, Molecules 2018, 23, 447.

- Kaplan D., Miller F. Neurotrophin signal transduction in the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol; 2000; 10:381–391. [CrossRef]

- Sariola H. The neurotrophic factors in non-neuronal tissues. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2001, 58: 1061–1066. [CrossRef]

- Chao MV., Neurotrophins and their receptors: a convergence point for many signalling pathways; Nat Rev Neurosci 4; 2003; 299–309.

- Cacialli P.; Lucini C. Analysis of the Expression of Neurotrophins and Their Receptors in Adult Zebrafish Kidney. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 296. [CrossRef]

- Chen J.; Niu Q.; Xia T.; Zhou G.; Li P.; Zhao Q.; Xu C.; Dong L.; Zhang S.; Wang A. ERK1/2-mediated disruption of BDNF-TrkB signaling causes synaptic impairment contributing to fluoride-induced developmental neurotoxicity. 2018.Toxicology,410, 222–230.

- Jia Y.; Liu Y.; Wang P.; Liu Z.; Zhang R.; Chu M.; Zhao A. NTRK2 Promotes Sheep Granulosa Cells Proliferation and Reproductive Hormone Secretion and Activates the PI3K/AKT Pathway. Animals 2024, 14, 1465. [CrossRef]

- Gao S., Chen S., Chen L., Zhao Y., Sun L., Cao M., Huang Y., Niu Q., Wang F., Yuan C., Li C., Zhou X. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor: A steroidogenic regulator of Leydig cells, J Cell Physiol, 2019; 234(8):14058-14067.

- Koeva Y, Davidoff M, Popova L. Immunocytochemical expression of p75LNGFR and trkA in Leydig cells of the human testis. Folia Medica 1999; 4: 53-58.

- Koeva Y, Davidoff M, Popova L. Identification of BDNF, NT-3 and their receptors localized in Leydig cells of human testis. Comp. Rend. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 2000; 53(2): 129- 132.

- Koeva Y. Immunolocalization of neurotrophic factors and their receptors in the Leydig cells of rat during postnatal development. Folia Medica, 2002; 3: 27-30.

- Müller D., Davidoff M., Bargheer O., Paust H., Pusch W., Koeva Y., Ježek D., Holstein A., Middendorff R. The expression of neurotrophins and their receptors in the prenatal and adult human testis: evidence for functions in Leydig cells. Histochemistry and Cell Biology, 2006, 126:199-211. [CrossRef]

- Tan X.; Zhao L.; Tang Y. The Function of BDNF and Its Receptor in the Male Genitourinary System and Its Potential Clinical Application. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 110–121. [CrossRef]

- Tchekalarova J, Nenchovska Z, Atanasova D, Lazarov N, Kortenska L, Stefanova M, Alova L, Atanasova M. Long-term consequences of prophylactic treatment with agomelatine on depressive-like behavior and neurobiological abnormalities in pinealectomized rats. Behav Brain Res 302 (2016) 11–28.

- Tchekalarova J., M. Atanasova, N. Ivanova, N. Boyadjiev, R. Mitreva, K. Georgieva. Endurance training exerts time-dependent modulation on depressive responses and circadian rhythms of corticosterone and BDNF in the rats with pinealectomy. Brain Res Bull 162 (2020а) 40-48. [CrossRef]

- Tchekalarova J, Kortenska L, Ivanova N, Atanasova M, Marinov P. Agomelatine treatment corrects impaired sleep-wake cycle and sleep architecture and increases MT1 receptor as well as BDNF expression in the hippocampus during the subjective light phase of rats exposed to chronic constant light. Psychopharmacol (Berl) 237 (2020b) 503-518. [CrossRef]

- Koeva Y., Barbutska D., Bakalska M., Atanassova N. Мorphological changes in rat Leydig cells reflecting the decreased testicular steroidogenic capacity during aging; Comptes rendus de l’Academie bulgare des Sciences, 2013, V.66(7), pp1047-1050. [CrossRef]

- Wei Liu, Li Du, Yinghong Cui, Caimei He, Zuping He. WNT5A regulates the proliferation, apoptosis and stemness of human stem Leydig cells via the β-catenin signaling pathway;2024; Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 81:93. [CrossRef]

- Pop O., Cotoi C., Plesea I. Histological and ultrastructural analysis of the seminiferous tubule wall in ageing testis. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2011; 52(1 suppl): 241-8.

- Adamczewska D, Słowikowska-Hilczer J, Walczak-Jędrzejowska R. The fate of Leydig Cells in men with spermatogenic failure. Life (Basel). 2022;12(4):570. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuş I., Sarsilmaz M., Ogetürk M., Yilmaz B., Keleştimur H., Oner H. Ultrastructural interrelationship between the pineal gland and the testis in the male rat, 2000, Arch; 45(2):119-24.

- Shor E., Brown S., Freeman D. A novel role for the pineal gland: Regulating seasonal shifts in the gut microbiota of Siberian hamsters Journal of Pineal Research, 2020, J Pineal Res:e12696. [CrossRef]

- Khan S., Adhikari J., Rizvi M. and Chaudhury N. Radioprotective potential of melatonin against 60Co γ-ray-induced testicular injuryin male C57BL/6 mice, Journal of Biomedical Science, 2015, 22:61.

- Sastre J., Pallardo F., De la Asuncion G. Mitochondria, oxidative stress and aging. Free Radic Res, 2000; 32(3):189-98.

- Lacombe A., Lelievre V., Roselli CE., Salameh W., Lue Y., Lawson G., Muller J., Waschek JA., and Vilain E. Delayed testicular aging in pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide (PACAP) null mice. PNAS, 2006; 103(10): 3793–3798. [CrossRef]

- Wang F., Wang Q., Chen Y., Lin Q., Gao HB and Zhang P. Chronic stress induces ageing-associated degeneration in rat Leydig cells, Asian Journal of Andrology; 2012, 14, 643–648.

- Sun Z, Wen Y, Zhang F, Fu Z, Yuan Y, Kuang H, Kuang X, Huang J, Zheng L, Zhang D. Exposure to nanoplastics induces mitochondrial impairment and cytomembrane destruction in Leydig cells. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2023; 255:114796. [CrossRef]

- Sharma P, Kaushal N, Saleth LR, Ghavami S, Dhingra S, Kaur P. Oxidative stress-induced apoptosis and autophagy: Balancing the contrary forces in spermatogenesis, 2023, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease, Volume 1869, Issue 6. [CrossRef]

- Koeva Y. Relaxin/insulin family peptides and receptors in aging rat testis. Comptes rendus de l’Academie bulgare des Sciences, 2011, vol.64, № 12, 1765-1772.

- Koeva Y., Barbutska D., Bakalska M., Atanassova N. Мorphological changes in rat Leydig cells reflecting the decreased testicular steroidogenic capacity during aging; Comptes rendus de l’Academie bulgare des Sciences, 2013, V.66(7), pp1047-1050. [CrossRef]

- Barbutska D., Koeva Y., Bakalska M., Atanassova N. Age related changes in the steroidproducing cells of rat testis, Scripta Scientifica Medica, 2013, V.45(3); pp:32-35. [CrossRef]

- Barbutska D., Koeva I. Ultrastructural changes in rat Leydig cells and their correlation with the expression of immunohistochemical markers in aging, Folia Medica, 2015a, V. 57; Suppl.2, pp.28.

- Beumer T.L., Roepers-Gajadien H.L., Gademan I., Kal H. and De Rooij D., Involvement of the D-Type Cyclins in Germ Cell Proliferation and Differentiation in the Mouse, Biology of Reproduction 63, 2000, 1893–1898. [CrossRef]

- Debeljuk L, Lasaga M., Modulation of the hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal axis and the pineal gland by neurokinin A, neuropeptide K and neuropeptide gamma, Peptides, 1999;20(2):285-99. [CrossRef]

- Blasco V, Pinto F, González-Ravina C, Santamaría-López, Candenas L. and Fernández-Sánchez M.,Tachykinins and Kisspeptins in the Regulation of Human Male Fertility, J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 113. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).