1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic complicated metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia, which often results from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both. According to the International Diabetes Federation, approximately 589 million adults were living with type 1 DM (T1DM) and type 2 (T2DM) in 2024; and it estimates that by 2050 this number will increase to 853 million. More than 1.8 million children and adolescents are living with T1DM worldwide, and there is a continuous increase in the number of young patients with T1DM and T2DM [

1]. The increased incidence of T1DM has been associated with falling birth rates and compromised fertility [

2].

A large number of studies, both in diabetic men and animal models indicate that DM causes male infertility via action at multiple levels including altered spermatogenesis, degenerative and apoptotic changes in the testes, altered glucose metabolism in Sertoli cells/blood testes barrier, reduced testosterone synthesis and secretion, ejaculatory dysfunction and reduced libido [

3]. In men with chronic diabetes and obesity, late-onset hypogonadism syndrome is more popular. Real obstacle to conduct studies on human male is for ethical reasons, e.g. nearly no testicular biopsies were available, therefore no systematic histopathology or molecular data from human testis of patients with DM can be available [

4]. Therefore, the use of animal models has been crucial to provide more detailed molecular and cellular insight on the effect of hyperglycaemia on the male reproductive system and fertility.

Many animal studies have employed streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetes as STZ is the most prominent diabetogenic chemical that is widely used in experimental animals for creating animal models of type 1 and type 2 diabetes [

5,

6]. STZ is a naturally occurring compound, produced by the soil bacterium

Streptomyces achromogenes that easily enters the pancreatic beta cells through Glucose transporter-2, causing alkylation/damage of the DNA and subsequent cell death resulting in rapid hyperglycaemia. STZ is proven to be a better diabetogenic agent than alloxan with wider species effectiveness and greater reproducibility [

7]. Moreover, the STZ model mimics many of the acute and chronic complications of human diabetes and gives the established similarities of some of the structural, functional and biochemical abnormalities to human disease. Hence, it is an appropriate model to assess the mechanism of diabetes.

The mammalian testis is a complex multicellular organ, separated into two distinct compartments which carry out its principle functions. In the adult testis, spermatogenesis and sperm production occur within the seminiferous tubules, and androgen biosynthesis (steroidogenesis) occurs in Leydig cells located in the interstitium.

Two major events of the testis development that occurred during sexual maturation are the establishment of spermatogenesis and the development of the adult Leydig cell population responsible for androgen production. Spermatogenesis in mammals is a dynamic and highly regulated process that encompasses numerous proliferating and differentiating steps from spermatogonia to spermatozoa resulting in production of the male gametes [

8].

Androgens are especially important for male sexual differentiation in fetal life, pubertal sexual maturation and the maintenance of spermatogenesis in adulthood. The effects of androgens are mediated through the androgen receptor (AR) that binds testosterone (T) with high affinity. In the testis AR is localized in peritubular cells, Leydig cells (LCs) and Sertoli cells (SCs) but not in germ cells (GCs). Preferential action of androgens at stages VII-VIII of the spermatogenic cycle of the rat coincided with the maximal expression of AR protein in Sertoli cells suggesting that androgen support for spermatogenesis is primarily mediated through the Sertoli cells [

9] – a conclusion that was supported by knockout models for selective ablation of AR in Sertoli cell (SCARKO mice) [

10].

Sertoli cells are involved in the regulation of spermatogenesis, providing nutritional support for germ cells. Glucose metabolism in Sertoli cells produces lactate for germ cells, which is crucial for spermatogenesis and in particular it is consumed by pachytene spermatocytes and round spermatids [

11]. Germ cells are highly reliant on carbohydrate metabolism as they need energy for their differentiation. However, metabolic stressors such as diabetes, impair glucose transport and lactate production, compromising energy supply. Hyperglycaemia has been shown to affect glucose uptake and lactate production by Sertoli cells by reducing follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and testosterone levels [

12].

Recent reviews have summarized a lot of data on metabolic and signal pathways of DM action on male reproductive function. The main mechanism of DM is induction of oxidative stress and inflammation and in many papers the role of molecules involved in these pathophysiological processes was discussed in relation to semen pathology/sperm characteristics and male infertility and profiles of reproductive hormones [

12,

13,

14]. Less data are published about the effect of DM on cellular composition of the testis and their functions. The investigations mainly used experimental models for T1DM induced in adulthood. Limited number of studies utilized neonatally induced DM as a model for T2DM but material taken for investigation was from adult animals. Two papers are published about the effect of DM induced in neonatal or pubertal age (day 15) on developing testis suggesting that more pronounced alterations occur in early-life induced DM compared to DM induced in adulthood [

15,

16].

Early postnatal period is crucial for establishment of spermatogenesis – resuming of mitotic division of precursors germ cells on day 4.5 (pre-spermatogonia) giving rise differentiated spermatogonia followed by start of meiosis on day 12 in rat [

17]. In this respect our interest was focused on the developmental effect of early DM induced neonatally on day 1 (NDM as it is applied to induced T2DM in adulthood), or prepubertally on day 10 (PDM). Hence, the aim of the present study is to follow the postnatal development of testicular germ and somatic cells (Leydig cells and Sertoli cells) in condition of experimentally induced NDM or PDM in relation to androgen production and action. The current work presents comparative evaluation of the impact of two types of DM providing new knowledge on differential effects of early postnatal DM on developing testicular cell populations and the first wave of spermatogenesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Model

The experimental protocol was performed at the Institute of Experimental Morphology, Pathology and Anthropology with Museum, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences according to the ARRIVE guidelines and EU Directive for animal experiments. The study was approved by the Bulgarian Agency for Food Safety, Approval number 282 from 24.09.2020.

Pregnant Wistar rats were purchased from the experimental and breeding base for laboratory animals (EBBLA) (Slivnitza, Bulgaria). Mothers were separated into individual standard hard-bottom polypropylene cages, fed a standard diet and had access to food and water ad libitum. After birth, the pups were i.p. injected with streptozotocin (STZ, Sigma-Aldrich, S0130) at a single dose of 100 mg/kg b.w. (dissolved in ice cold 0.1 M citrate buffer, pH 4.5) on day 1 to induce neonatal diabetes mellitus (NDM) or on day 10 to induce prepubertal diabetes mellitus (PDM). Control age-matched animals were injected with citrate buffer. Two days after STZ injection, the blood glucose was measured using a glucometer (Accu-chek Performa, Roshe). Hyperglycaemic status was confirmed by blood glucose level > 15 mmol/L.

At weaning (day 25) the offspring were separated from their mothers to the end of the protocol. Investigated groups consist only of male rats (n = at least 6). The rats were sacrificed (Small Animal Decapitator, Stoelting™ 51330) under light anaesthesia on postnatal days 25 (puberty) and 45 (post puberty/early adulthood). Blood was obtained after decapitation and serum was stored at -80°C for subsequent analysis. Both testes were excised and the left testis was fixed in Bouin solution, dehydrated and embedded in paraffin for further histological studies.

2.2. Measurement of Body and Testis Weight

The body weight of the animals was measured before sacrifice. Testes of control and experimental rats were excised, weighed and relative testis weight (gonado-somatic index) was calculated as a ratio of average weight of both testes to body weight, multiplied by 100.

2.3. Measurement of Serum Glucose

Glucose levels (nonfasting on day 25 and fasting on day 45) were evaluated in serum of control and diabetic animals by commercial kits (Chema Diagnostica, Italy) on biochemical analyzer BA-88 (Mindray, China).

2.4. Measurement of Serum Testosterone and Serum Luteinizing Hormone

Serum testosterone and serum luteinizing hormone (LH) levels were evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the instructions of the kit manufacturer (Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd, China). Competitive ELISA for testosterone (Cat. № E-EL-0155) and sandwich-ELISA for luteinizing hormone (Cat. № E-EL-R0026) were performed. The optical density was read at 450 nm on an ELISA Reader BioTek (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). Curve Expert Professional 2.7 software was used. The final concentration of testosterone was calculated in ng/mL. The final concentration of luteinizing hormone was multiplied by the dilution factor (x6) and calculated in mlU/mL.

2.5. Stereological Analyses

For morphometric/stereological analyses of germ and Sertoli cells, Bouin’s fixed, 5 µm paraffin embedded tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). For Leydig cells enumeration, tissue sections were immunostained for 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD) that is specific marker for steroid-producing cells. Testicular cell composition was estimated using standard stereological techniques involving point counting of cell nuclei to determine the nuclear volume per testis of Sertoli cells, Leydig cells and different maturational stages of germ cells, as previously described [

18]. In brief, cross-sections of testes were examined using 63x objective and a 121-point eyepiece graticule (Leica Microsystems,Wetzlar, Germany) fitted to Zeiss AxioScope A1 microscope. Applying a systematic sampling pattern from a random starting point, 32 microscopic fields (3872 points) were counted for each animal. Points falling over Leydig cells, Sertoli cells, or germ cell nuclei (including spermatogonia, spermatocytes, round and elongated spermatids), seminiferous epithelium, interstitium, and seminiferous tubule lumen were scored and they were expressed as relative (%) volume per testis. Values for percent nuclear volume were converted to absolute nuclear volume (ANV) per testis by reference to testis volume (=weight) because shrinkage was minimal. Cell nuclear volume can be equated to numbers of cells per testis, assuming no change in nuclear diameter of the target cell in the different experimental groups [

10,

18].

2.6. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for Androgen Receptor (AR), 3β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase (3β-HSD) and Testicular Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (tACE)

Unless otherwise stated, all incubations were performed at room temperature. The deparaffinized and rehydrated 5 μm sections of control and experimental testes were subjected to a temperature-induced antigen retrieval step in 0.01 M citrate buffer, pH 6.0 - tACE, AR and 3β-HSD. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by immersing all sections in 3% (vol/vol) H2O2 in methanol for 30 min, followed by two 5-min washes in Tris-buffered saline (TBS). To block nonspecific binding sites, sections were incubated for 30 min with 10% blocking serum in TBS containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA): for AR it was normal swine serum; for tACE and 3β-HSD – normal rabbit serum. After that primary antibodies were added to the sections at appropriate dilutions in blocking serum and incubated overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber. Antibodies were applied as follow: rabbit polyclonal anti-androgen receptor (N-20; sc-816 Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. USA), diluted 1:200; goat polyclonal anti-tACE (sc-12187, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc), diluted 1:500; goat polyclonal anti-3β-HSD (P-18; sc-30820, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc), diluted 1:500. After two 5-min washes in TBS, sections were incubated with biotinylated secondary antibodies as follow: for AR - swine anti-rabbit (dilution 1:500, DAKO Cytomation, Denmark); for tACE and 3β-HSD - rabbit anti-goat (Vector BA-5000) for 30 min. After two additional 5-min washes in TBS, sections were incubated for 30 min with avidin-biotin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (ABC Reagent, Vector Laboratories Inc., USA). Sections were washed twice in TBS, and immunostaining was developed using 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (liquid DAB; DAKO Corp.) The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated before mounting and observed under a light microscope Zeiss AxioScope.A1 (Carl Zeiss, Germany).

Negative controls were ran in parallel by omitting the primary antibody under the same conditions. For AR the negative control was done also by preabsorption of primary antibody with peptide immunogen sc-816P.

2.7. Semen Analysis

The sperm characteristics were evaluated by computer-assisted sperm analysis (SCA®, Sperm Class Analyzer, Microptic®, Spain). Briefly, the semen samples were collected from both cauda epididymides of control and diabetic rats (NDM and PDM) and placed in pre-warmed (37°C) HEPES solution (pH 7.4). After incubation at 37°C for 20 min, 5 μL of each sample were transferred to a chamber Leja 20 (Leja Products B.V., Nieuw-Vennep, The Netherlands) and were analyzed using a microscope (Nikon Eclipse E200, Nikon) with 10× objective (Nikon 10×/0.25 Ph1 BM, Nikon) under negative phase contrast and camera with high resolution (768 × 576 pixels). All samples were evaluated twice to determine the sperm concentration and motility (percentage of sperm moving faster than 10 µm/s).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The obtained data were processed using SPSS 16.0 for Windows. The results are presented as mean value ± standard error (SE). Statistical significance between the experimental groups was assessed using one-way ANOVA and p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

4. Discussion

During the last two decades a large number of studies both on diabetic men and experimental diabetic animals have been published on the impact of DM on male reproduction but many of them have conflicting results. Prevailing notion is that DM alters spermatogenesis, sperm parameters, biosynthesis of testosterone and induces degenerative changes in the testis that lead to sub-fertility or infertility. Although extensive research has been done on experimental models for induction of DM in adulthood (sexually maturity), the studies on the effect of hyperglycaemia on immature animals are very limited.

Early postnatal period is known to be critical for development of male germ cells when after prolonged resting period in fetal and neonatal life, the precursors of germ cells (pre-spermatogonia) resume mitotic division on day 4.5 in rat giving rise to differentiated spermatogonia. The latter proceed to series of consecutive divisions to enter the first prophase of meiotic division with formation of primary spermatocytes that occurs on day 12 in rat. Both major events are crucial for establishment of spermatogenesis and any interference during this time results in poor reproductive capacity and infertility [

17]. Aside from initiative role of pituitary gonadotrophic hormones and androgen locally produced in the testis, insulin might also have a direct action on testicular cell composition. Germ cells are highly dependent on carbohydrates needed for energy homeostasis being vulnerable to any disturbance in glucose metabolism [

12,

20].

By evaluating the impact of DM induced in early life, the current study promises to provide new data suggesting that neonatal or prepubertally induced hyperglycaemia may exert differential effects on testicular cell populations (germ and somatic cells) during the first wave of spermatogenesis that results in poor semen quality.

Based on glucose levels, 25-day-old NDM rats in our study were normoglycaemic, as expected [see King, 2012 [

5] for neonatally induced T2DM] and later they developed mild hyperglycaemia. In contrast, PDM animals were hyperglycaemic on day 25. As hyperglycaemia became more severe on day 45, PDM rats might be considered as T1DM model.

Day 25th in rats is considered as mid-puberty and spermatogenesis proceeds to late pachytene-diplotene spermatocytes. Day 45th is post-puberty/early adulthood as spermatogenesis is completed but without sperm ejaculation and therefore animals are still immature.

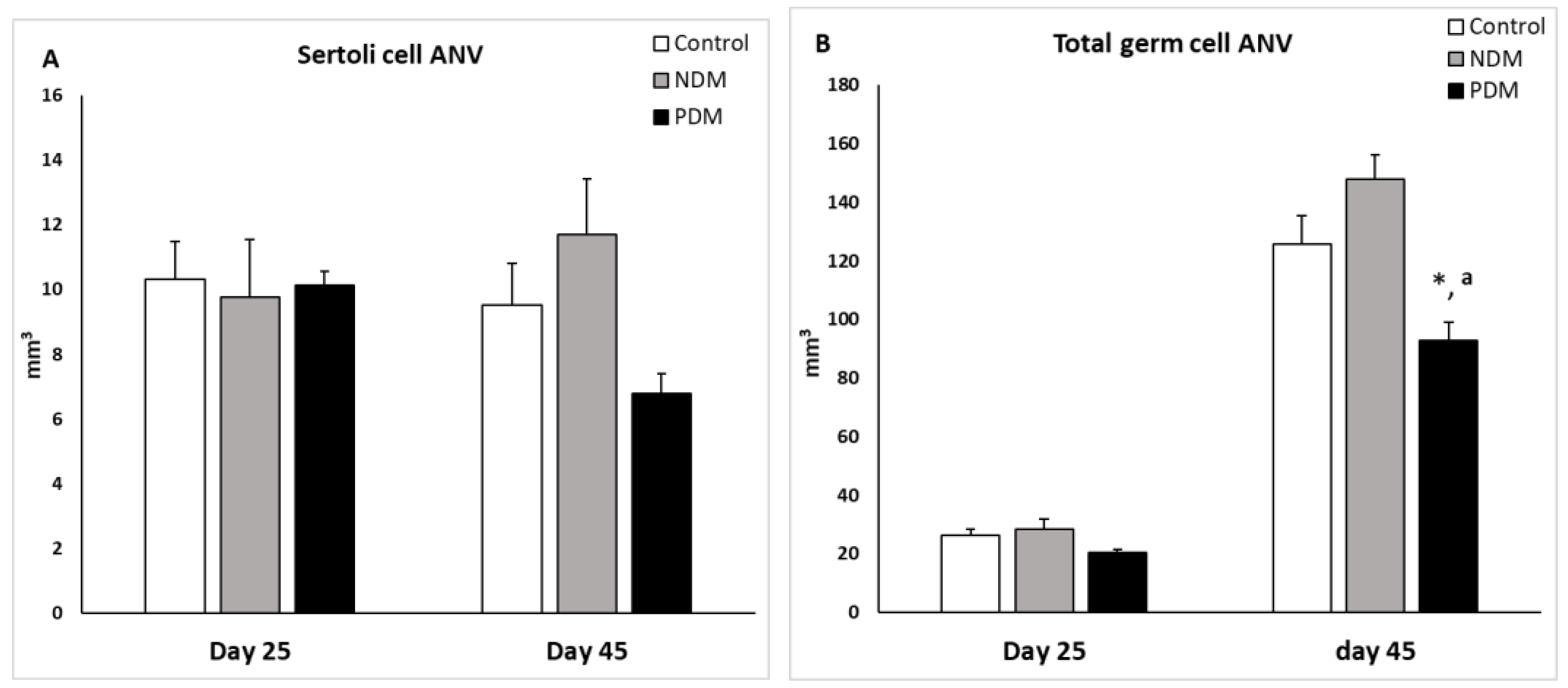

Quantification of total germ cell population revealed different effects of both types of DM. NDM resulted in an increase in total germ cell absolute nuclear volume (TGC-ANV) at both ages by 9% – 18% compared to controls while PDM caused a decrease in this parameter by 75%. Limited data are available that the germ cell number was reduced in adult animals with T1DM or T2DM induced by different treatment protocols (high fat diet (HFD) or nicotinamide (NAD) plus STZ as well drinking of fructose [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. In the few papers published on neonatally induced DM there are no data about testicular cell numbers. Comparatively study by Barsiah et al. [

21] demonstrated more pronounced reduction in total cell number in seminiferous tubules (germ and Sertoli cells) by T1DM than adult T2DM. Our new data for germ cell counts suggest different (opposite) effects on spermatogenesis caused by both types of DM – decrease v/s increase of GC-ANV in PDM and NDM, respectively.

Evaluation of proceeding of spermatogenesis in post-pubertal diabetic rats (45-day-old) demonstrated for the first time delayed development of late stages in spermatogenesis (post-meiotic stages – round and elongated spermatids) in post-pubertal PDM but not in NDM rats. Germ cell depletion mainly of round spermatids also contributes to decreased germ cell number in PDM. It seems that germ cells are more vulnerable to PDM than to NDM that could be explained by different glucose profiles and different time of administration of STZ. PDM is induced at time of active proliferation of spermatogonia before entering meiosis while NDM is induced during quiescent period (mitotic arrest) of precursor spermatogonia (pre-spermatogonia). The authors cited in the paragraph above induced T1DM or T2DM by different treatment regimens and investigation was conducted on adult animals. That could explain our different finding for increased total ANV of GCs in NDM.

Many studies indicated that apoptosis and oxidative stress in tandem with inflammation are responsible for germ cell loss in diabetic conditions (summarized in review articles [

12,

13,

14]. Recently, we reported increased protein expression of pro-apoptotic factor Bax, more pronounced in PDM than NDM rats and these data could provide explanation for the decreased TGC-ANV in PDM animals (by 25%) [

26]. Also, the levels of some molecular markers for oxidative stress (3-Nitrotyrosine, 3-NT and 4-hydroxynonenal, 4-HNE) were elevated more in PDM than in NDM that is associated with increased protein expression of pro-inflammatory marker, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) [

27].

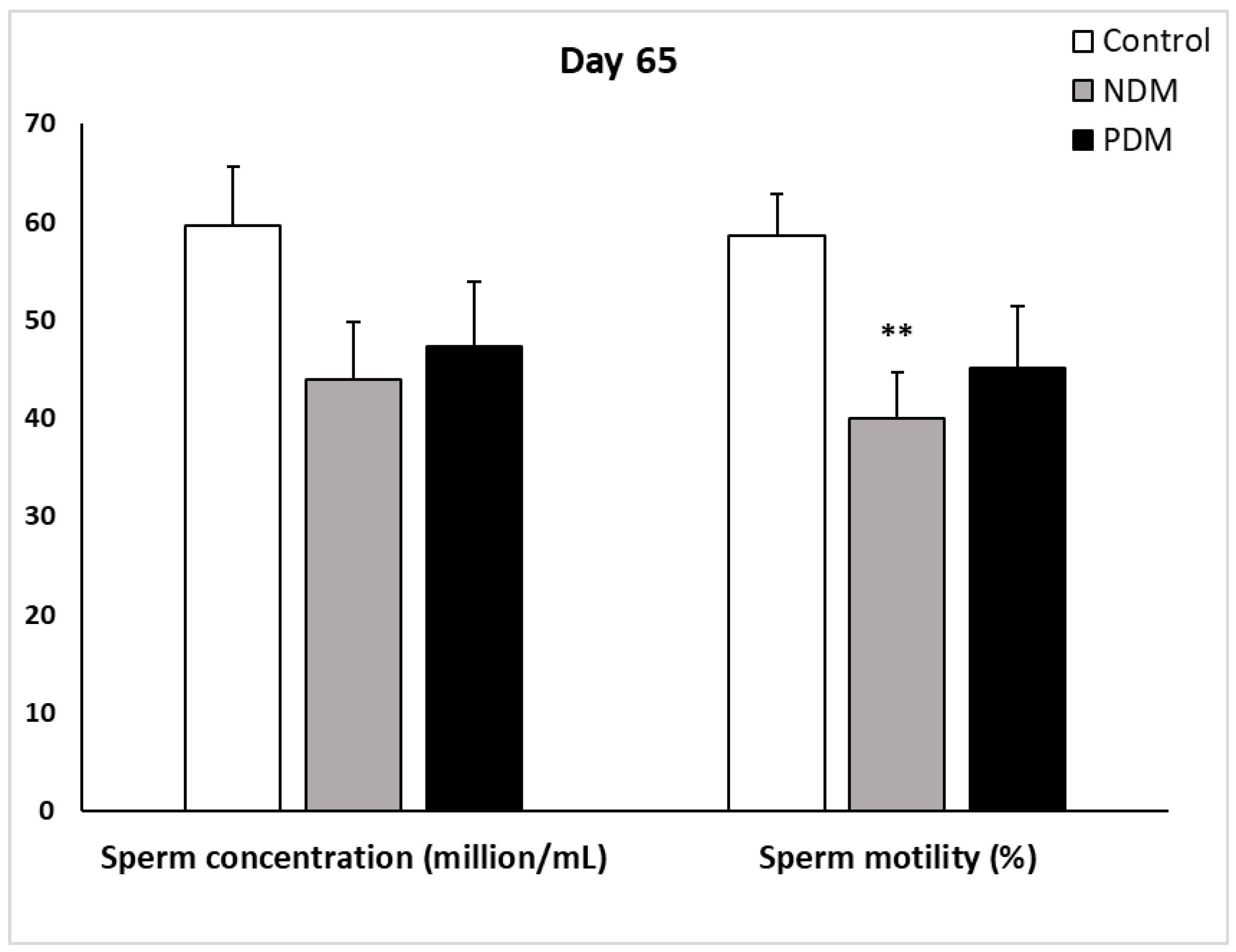

To follow the consequences of impaired spermatogenesis on fertility, we evaluated semen parameters (sperm count/concentration and sperm motility) on day 65 in both diabetic groups. The sperm count and sperm motility decreased in similar extent in PDM and NDM. An extremely high number of round shaped abnormal undifferentiated cells were counted (11-fold increase) in NDM but not in PDM that might be a reason for decreased sperm parameters in NDM despite no obvious destructive changes in post-pubertal 45-day-old rats. Most of the papers reported decreased sperm concentration and motility in T1DM [

25,

28,

29,

30] and in T2DM [

22] but data from NDM in adulthood are contradictory – decreased semen parameters [

16] v/s increased sperm concentration [

31].

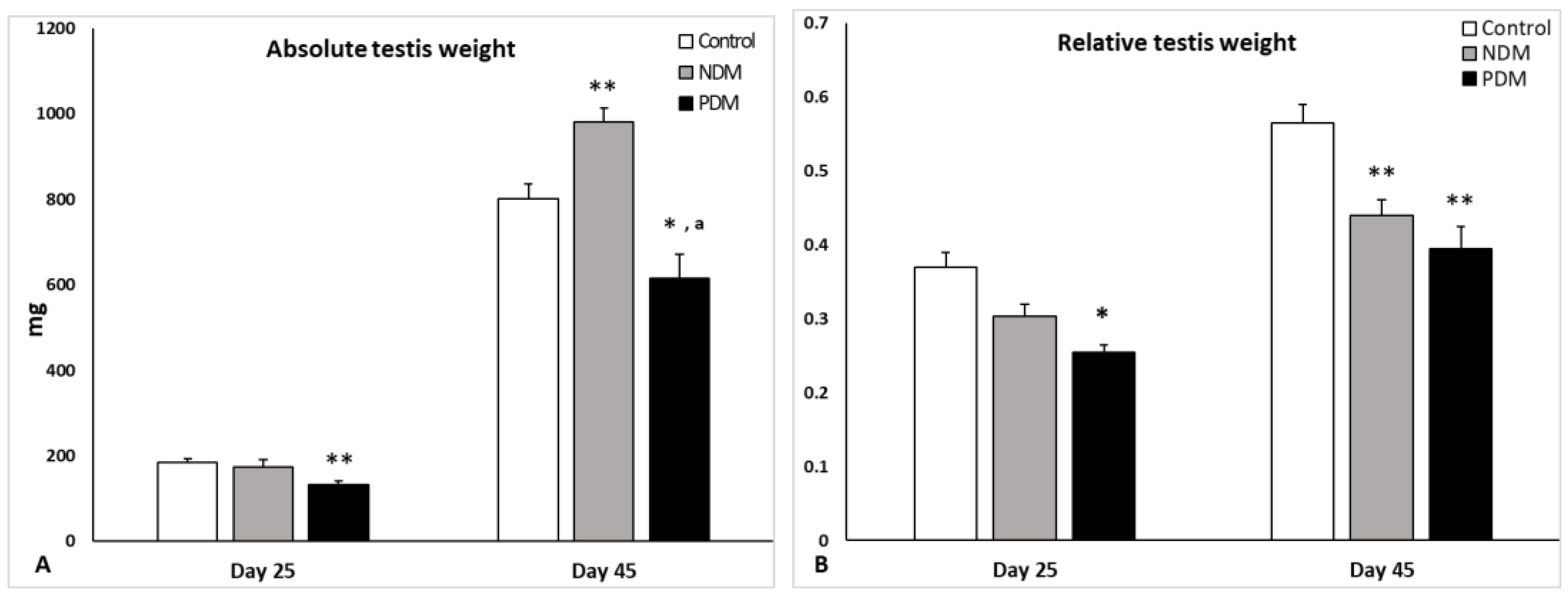

There is a general agreement that changes in absolute testis weight reflect those in TGC-ANV and our results support this finding. Interestingly, the relative testis weight decreased in NDM and PDM animals on days 25 and 45. Although both testis weight and body weight were elevated in NDM the increment in body weight was higher than that in testis weight. Most of the data in the literature indicate lower absolute testis weight in adult rodents with T1DM and T2DM measured in adulthood. Barsiah et al. [

21] reported decreased testis weight only in adult animas with T1DM but not in T2DM - a finding that fits to our results for increased testis weight in NDM post-pubertal rats. We also found higher volume of seminiferous epithelium (SE) in 45-day-old NDM rats in contrast to lower value in PDM. Interestingly, luminal volume of seminiferous tubules (ST) was twice increased in NDM but decreased in PDM. There are discrepancies in the literature data regarding the testicular macro-parameters due to different treatment regimens. Some studies reported decrease in SE volume, ST and lumen diameter in diabetic rats [

24] while others found elevation in their values [

21,

29].

Sertoli cells are essential for developing germ cells to sustain spermatogenesis by providing them unique microenvironment, physical support, growth factors and appropriate nutrients, including glucose. Any metabolic alteration in these cells derived from DM may be responsible for impaired spermatogenesis resulting in compromised fertility. These cells have a glucose sensing machinery that reacts to hormonal fluctuations and several mechanisms to counteract hyper/hypoglycemic events [

20]. Extensive research has been done on the expression of molecular markers for oxidative stress and inflammation including innate immune response in condition of hyperglycaemia [

11,

32]. Less data are available on quantitative aspects of adult Sertoli cells in conditions of DM but none are available for Sertoli cells of developing testis. Our data revealed that at pubertal age NDM and PDM did not produce changes in SC-ANV, which was later insignificantly decreased in PDM. Reduced number of SCs and GCs was reported in adult T1DM and T2DM associated with increased apoptosis [

22,

24,

25,

33]. A possible explanation for the higher SC-ANV in NDM post-pubertal rats in our study might be explained by the higher absolute testis weight. Increased Sertoli cell number was demonstrated by Tavares et al. [

34] in

in vitro studies on neonatal mouse organ cultures as well on TM4 Sertoli cell line treated by D-glucose. An important indicator for Sertoli cell support toward germ cells is the ratio of TGC-ANV/ SC-ANV [

18] and in the current study we did not find any evidence for altered Sertoli cell supportive function.

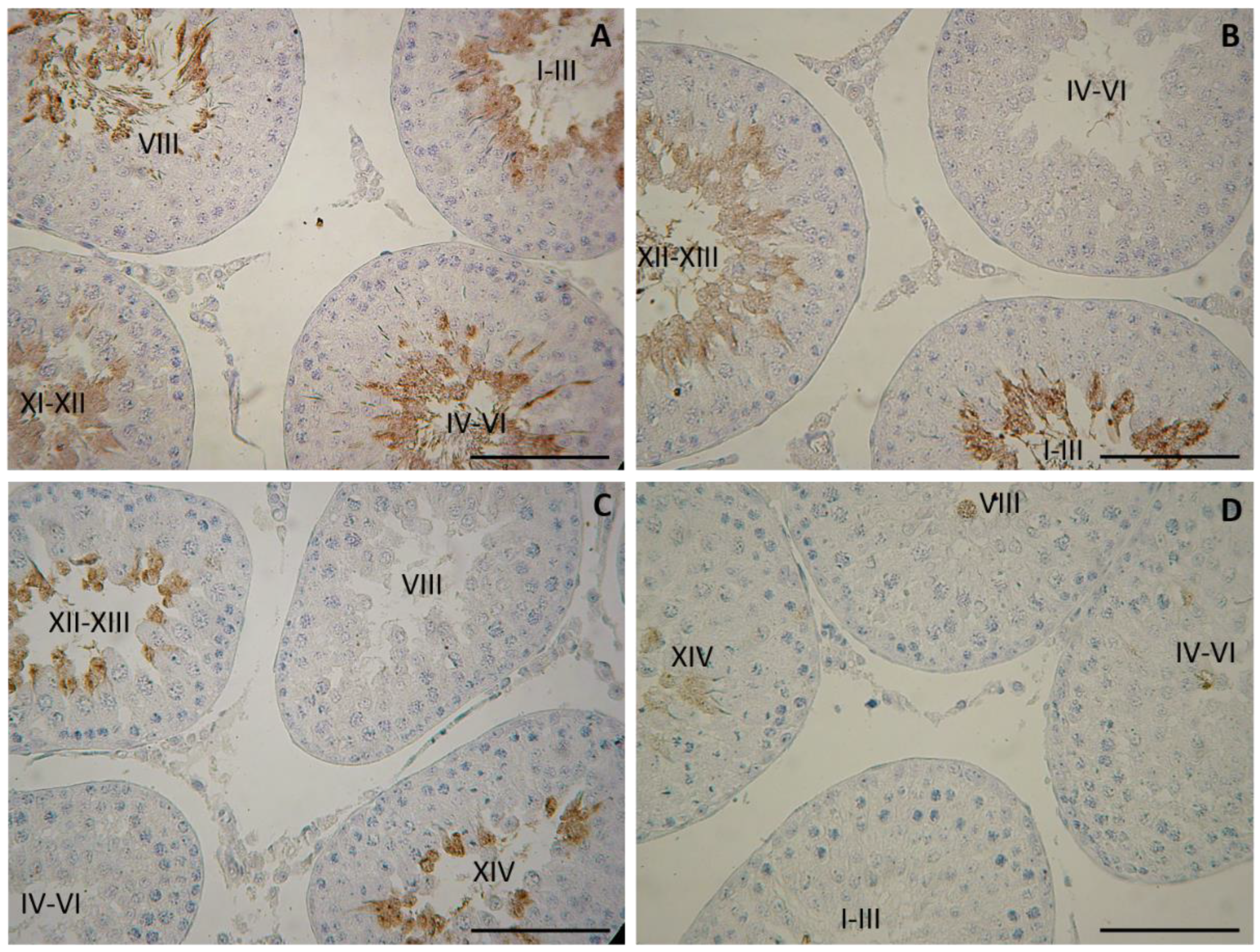

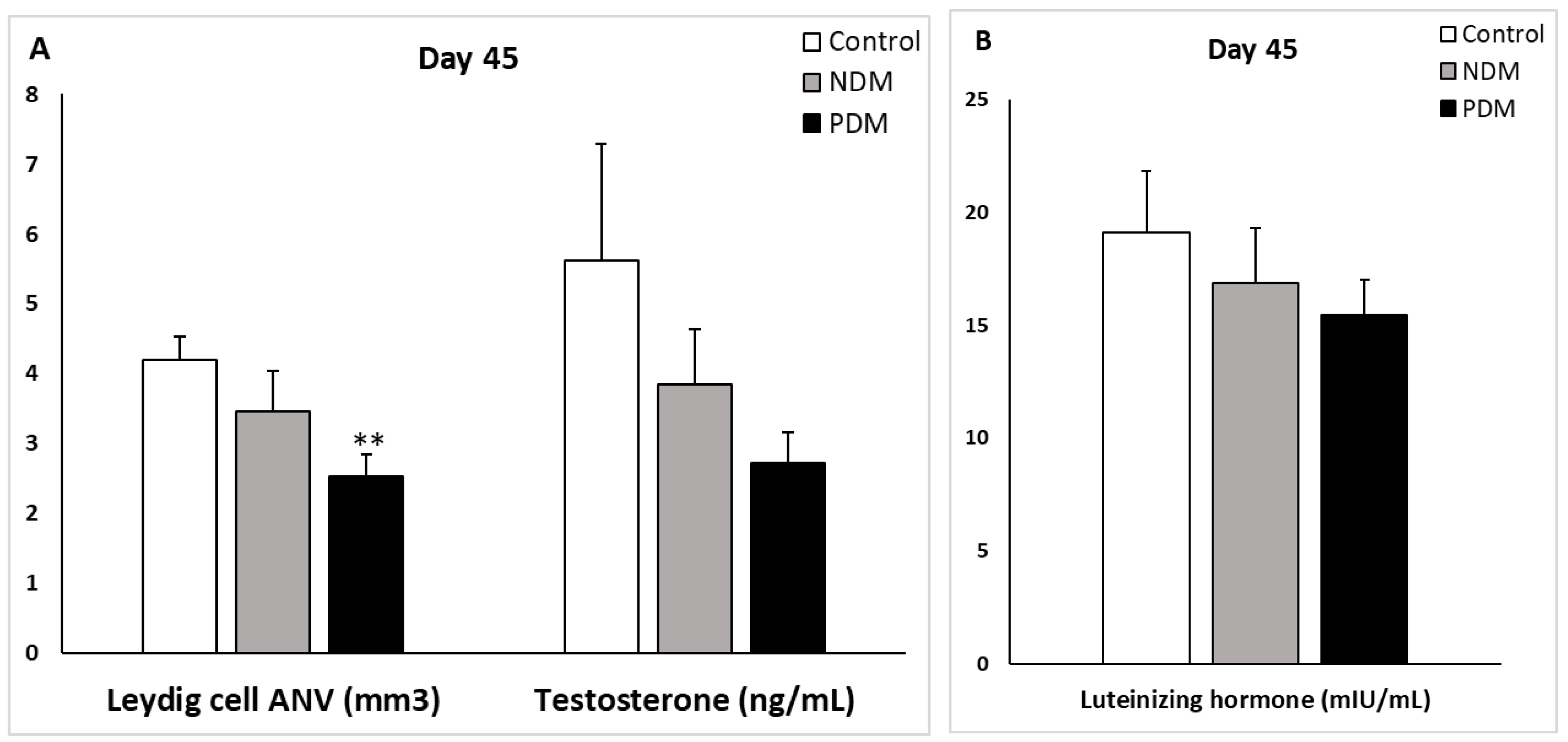

Sertoli cells have long been considered the prime candidates of androgen regulation of spermatogenesis because of specific expression of AR through the stages of seminiferous epithelium. The current study did not find any changes in AR expression in Sertoli cells in pubertal 25-day-old DM rats. Later, at post-pubertal stage when spermatogenesis is completed, the stage-specific pattern in Sertoli cells was not maintained in PDM. Instead, an uniform pattern of AR expression was seen as a result of increased expression in the late stages of spermatogenic cycle. Such a phenomenon we have reported in other experimental condition of hormonal manipulation as androgen withdrawal [

19]. A possible compensatory mechanism of androgen signaling could be suggested as it is essential for developing germ cells in condition of compromised androgen production in PDM. According to Ballester et al. [

35] AR protein levels (measured by Western blot) were not changed in T1DM adult rats while Favaro et al. [

36] found reduced expression of AR in prostate epithelium (reduced number of AR positive cells and protein levels in tissue homogenates).

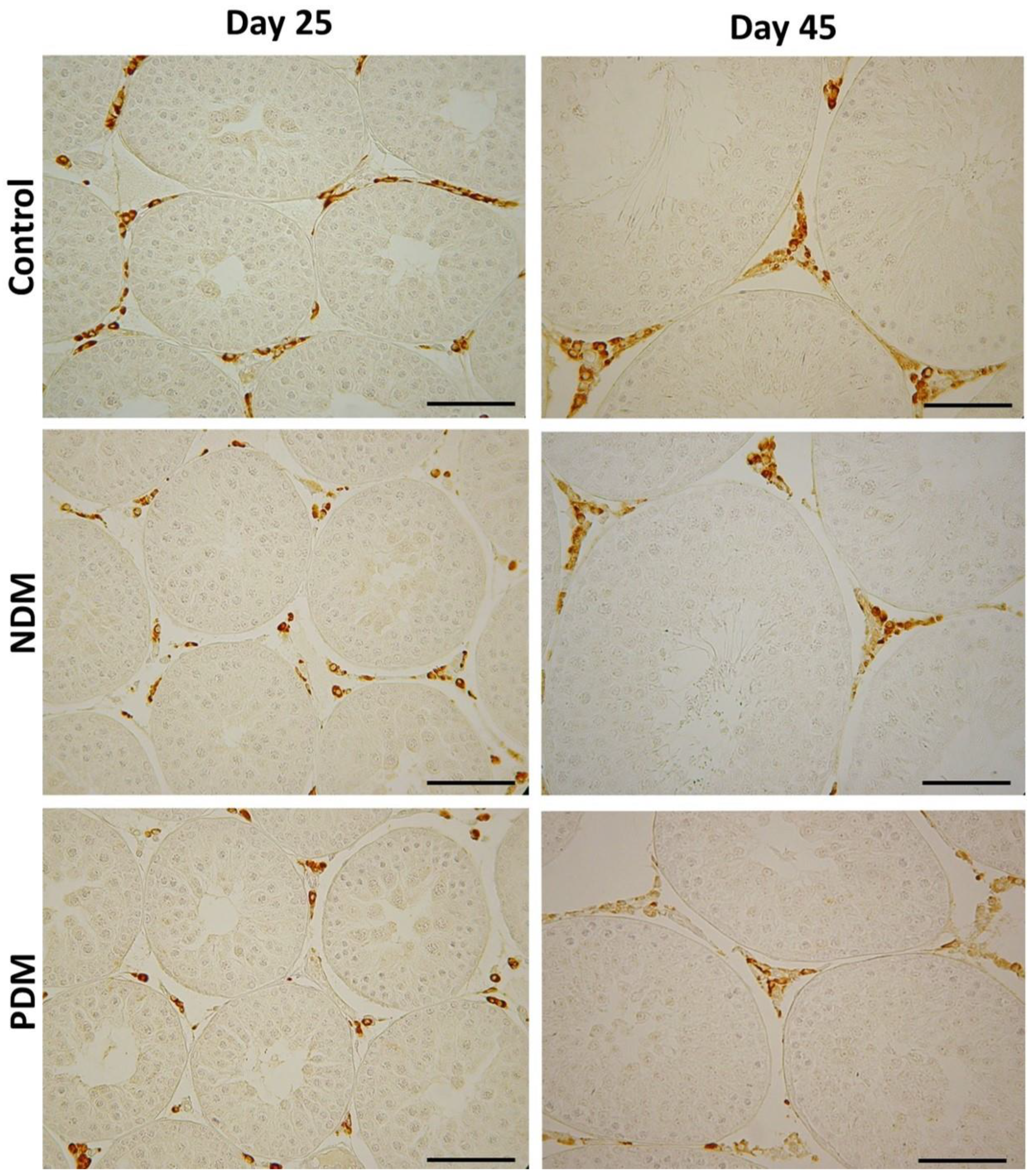

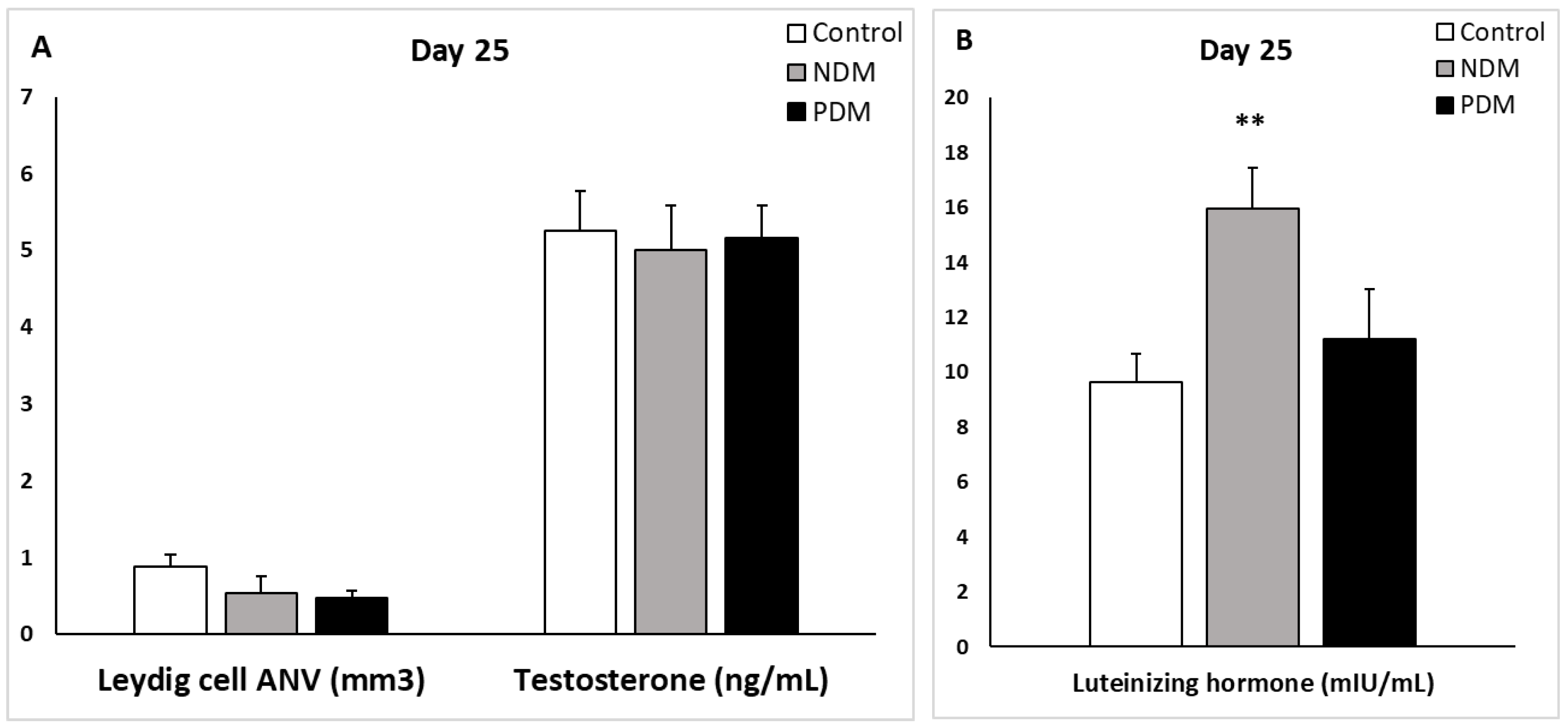

Leydig cells are known to drive spermatogenesis via synthesis and secretion of testosterone after stimulation by pituitary luteinizing hormone. Testosterone in turn acts on Sertoli cells to establish unique environment for normal progression of germ cells through the spermatogenic cycle [

8]. Experimental manipulations for androgen deficiency provided evidence for reduced size of adult Leydig cell population [

18]. After visualization by specific LC marker (3β-HSD) we found reduced ANV of Leydig cells (LC-ANV) in pubertal and post-pubertal NDM and PDM rats compared to controls that was more pronounced in PDM. Intact testosterone production in both pubertal DM groups could be explained by increased ratio of nuclear to cytoplasm volume indicative that LCs are functionally more active in conditions of hyperglycaemia. In later life we found that the changes in testosterone concentration corresponded to that in LC-ANV and the reduction in both parameters was more pronounced in PDM than in NDM. The elevation in LH levels in both diabetic groups could be interpreted as a compensatory mechanism for providing stimuli to the LCs (decreased in number) so that they can maintain normal testosterone production. There are some discrepancies between data on LC number and T biosynthesis in T1DM and T2DM diabetic models. Most of the studies demonstrated decreased number of Leydig cells (LCs were not specifically immunostained and were not distinguished correctly from other cell types in the interstitium) as well as reduced serum T levels [

24,

25,

33,

35]. In these studies reduced number of Sertoli and germ cells were also found together with elevated apoptosis. In other studies Leydig cell hypertrophy or hyperplasia and decreased T levels were reported [

15,

37]. In addition, low levels of testosterone and pituitary gonadotropic hormones (FSH and LH) were summarized in recent review articles [

12,

13,

38]. Down-regulation of the expression of key genes of androgen biosynthesis is involved in suppression of testosterone production in Leydig cells [

39,

40]. One paper reported different hormonal profiles between adult T1DM and T2DM [

21] – decreased serum gonadotrophins in T1DM but not in T2DM. Our results imply that adult LCs underwent more pronounced negative changes in PDM than in NDM.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ek.P. and N.A.; Methodology, Ek.P., R.I., D.A., Y.G., Em.P., I.V. and E.L.; Investigation, Ek.P., R.I., D.A., Y.G., Em.P., I.V. and E.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Ek.P. and N.A.; Writing—Review and Editing, N.A.; Visualization, Ek.P.; Supervision, N.A.; Project Administration, N.A.; Funding Acquisition, N.A.; Data Analysis, Ek.P., R.I., D.A., Y.G., Em.P., I.V. and N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Absolute testis weight (A; mg) and relative testis weight/ (B; testis weight to body weight ratio) on days 25 and 45 of control and diabetic rats. Data represent mean value ± standard error (SE); * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 – statistical significance compared to the control value; a – statistically significant difference compared to NDM. NDM – neonatally-induced diabetes; PDM – prepubertally-induced diabetes.

Figure 1.

Absolute testis weight (A; mg) and relative testis weight/ (B; testis weight to body weight ratio) on days 25 and 45 of control and diabetic rats. Data represent mean value ± standard error (SE); * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 – statistical significance compared to the control value; a – statistically significant difference compared to NDM. NDM – neonatally-induced diabetes; PDM – prepubertally-induced diabetes.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical localization of testicular angiotensin-converting enzyme (tACE) in testes of 45-day-old rats – controls (A) and prepubertally induced diabetic rats (B, C, D). Scale bar = 50 µm.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical localization of testicular angiotensin-converting enzyme (tACE) in testes of 45-day-old rats – controls (A) and prepubertally induced diabetic rats (B, C, D). Scale bar = 50 µm.

Figure 3.

Absolute nuclear volume (ANV, mm3) of Sertoli cells (A) and total germ cells (B) on day 25 and day 45 of control and diabetic rats. Data represent mean value ± standard error (SE); * p < 0.05 – statistical significance compared to the control value; a – statistically significant difference compared to NDM. NDM – neonatally-induced diabetes; PDM – prepubertally-induced diabetes.

Figure 3.

Absolute nuclear volume (ANV, mm3) of Sertoli cells (A) and total germ cells (B) on day 25 and day 45 of control and diabetic rats. Data represent mean value ± standard error (SE); * p < 0.05 – statistical significance compared to the control value; a – statistically significant difference compared to NDM. NDM – neonatally-induced diabetes; PDM – prepubertally-induced diabetes.

Figure 4.

Semen analysis of spermatozoa, isolated from both cauda epididymides of 65-day-old control and diabetic rats. Data represent mean value ± standard error (SE); ** p < 0.01 – statistical significance compared to the control value. NDM – neonatally-induced diabetes; PDM – prepubertally-induced diabetes.

Figure 4.

Semen analysis of spermatozoa, isolated from both cauda epididymides of 65-day-old control and diabetic rats. Data represent mean value ± standard error (SE); ** p < 0.01 – statistical significance compared to the control value. NDM – neonatally-induced diabetes; PDM – prepubertally-induced diabetes.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical visualization with the marker enzyme 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD) in Leydig cells in 25-day-old and 45-day-old controls and diabetic rats with neonatal (NDM) and prepubertal diabetes (PDM). Scale bar = 50 µm.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical visualization with the marker enzyme 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD) in Leydig cells in 25-day-old and 45-day-old controls and diabetic rats with neonatal (NDM) and prepubertal diabetes (PDM). Scale bar = 50 µm.

Figure 6.

Absolute nuclear volume (ANV) of Leydig cells (mm3) and serum testosterone levels (ng/mL) (A) and serum luteinizing hormone (mlU/mL) (B) on day 25 of control and diabetic rats. NDM – neonatally-induced diabetes; PDM – prepubertally-induced diabetes.

Figure 6.

Absolute nuclear volume (ANV) of Leydig cells (mm3) and serum testosterone levels (ng/mL) (A) and serum luteinizing hormone (mlU/mL) (B) on day 25 of control and diabetic rats. NDM – neonatally-induced diabetes; PDM – prepubertally-induced diabetes.

Figure 7.

Absolute nuclear volume (ANV) of Leydig cells (mm3) and serum testosterone levels (ng/mL) (A) and serum luteinizing hormone (mlU/mL) (B) on day 45 of control and diabetic rats. ** p < 0.01 – statistical significance compared to the control value. NDM – neonatally-induced diabetes; PDM – prepubertally-induced diabetes.

Figure 7.

Absolute nuclear volume (ANV) of Leydig cells (mm3) and serum testosterone levels (ng/mL) (A) and serum luteinizing hormone (mlU/mL) (B) on day 45 of control and diabetic rats. ** p < 0.01 – statistical significance compared to the control value. NDM – neonatally-induced diabetes; PDM – prepubertally-induced diabetes.

Figure 8.

Immunohistochemical expression of androgen receptor (AR) in Sertoli cells in 25- and 45-day-old control (A and D) and rats with neonatal DM (B and E) and prepubertal DM (C and F). A weaker intensity of reaction was observed in Sertoli cells of PDM rats. Note uniform intensity of the reaction in Sertoli cells of PDM rats aged 25 and 45 days. Scale bar = 50 µm. Negative control was done by preabsorption of primary antibody with peptide immunogen (picture inserted into control picture of day 25).

Figure 8.

Immunohistochemical expression of androgen receptor (AR) in Sertoli cells in 25- and 45-day-old control (A and D) and rats with neonatal DM (B and E) and prepubertal DM (C and F). A weaker intensity of reaction was observed in Sertoli cells of PDM rats. Note uniform intensity of the reaction in Sertoli cells of PDM rats aged 25 and 45 days. Scale bar = 50 µm. Negative control was done by preabsorption of primary antibody with peptide immunogen (picture inserted into control picture of day 25).

Table 1.

Serum glucose levels (mmol/L) in control and diabetic animals on days 25 (nonfasting) and 45 (fasting). Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE); * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 - statistical significance compared to the control value. NDM – neonatally-induced diabetes; PDM – prepubertally-induced diabetes.

Table 1.

Serum glucose levels (mmol/L) in control and diabetic animals on days 25 (nonfasting) and 45 (fasting). Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE); * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 - statistical significance compared to the control value. NDM – neonatally-induced diabetes; PDM – prepubertally-induced diabetes.

| |

Day 25 |

Day 45 |

| Control |

10.86 ± 0.50 |

7.22 ± 0.84 |

| NDM |

11.49 ± 0.54 (6% ↑) |

9.04 ± 1.27 (27% ↑) |

| PDM |

14.00 ± 1.80 (30% ↑) |

13.73 ± 3.72 * (93% ↑) |

Table 2.

Comparison of the absolute volumes of the seminiferous epithelium, lumen and interstitial tissue in control and diabetic groups (NDM and PDM) on days 25 and 45. Data represent mean value ± standard error (SE); * p < 0.05 – statistical significance compared to the control value. NDM – neonatally-induced diabetes; PDM – prepubertally-induced diabetes.

Table 2.

Comparison of the absolute volumes of the seminiferous epithelium, lumen and interstitial tissue in control and diabetic groups (NDM and PDM) on days 25 and 45. Data represent mean value ± standard error (SE); * p < 0.05 – statistical significance compared to the control value. NDM – neonatally-induced diabetes; PDM – prepubertally-induced diabetes.

| |

|

Interstitium

(mm3)

|

Lumen

(mm3)

|

Seminiferous

epithelium

(mm3)

|

| Day 25 |

Control |

31.32 ± 2.32 |

14.09 ± 2.61 |

136.36 ± 10.39 |

| NDM |

28.03 ± 4.47 |

13.53 ± 2.47 |

131.11 ± 12.29 |

| PDM |

20.45 ± 2.52 * |

8.30 ± 2.07 * |

105.25 ± 10.07 |

| Day 45 |

Control |

116.27 ± 14.11 |

47.87 ± 7.74 |

637.86 ± 35.54 |

| NDM |

108.41 ± 6.62 |

105.73 ± 30.76 |

756.86 ± 34.30 * |

| PDM |

96.38 ± 6.47 |

40.89 ± 10.22 |

478.73 ± 40.36 * |