1. Introduction

Recently, dietary supplements have become more commonly used in Japan as people become more health conscious, and according to the 2019 National Health and Nutrition Survey by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 34.4% of people aged 20 and older consume dietary supplements [

1]. A wide range of dietary supplements exists, yet their potential side effects and interactions with medications have not been sufficiently validated. Some dietary supplements have ingredients that can affect perioperative conditions due to abnormalities in the blood coagulation system, cardiovascular system, electrolytes, and prolonged anesthetic effects [

2].

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) recommends discontinuing healthy foods for at least 2 weeks before surgery. Healthy foods from the ASA that affect the perioperative period include ephedra, garlic, ginkgo, ginseng, kava, St. John’s wort, valerian, and vitamin E [

3]. In addition, Hatfield et al. reported that garlic, hawthorn, cordyceps, echinacea, and aloe vera are associated with surgical bleeding independent of anticoagulants, while ginkgo biloba, chondroitin-glucosamine, melatonin, turmeric, bilberry, chamomile, fenugreek, milk thistle, peppermint, cinnamon, and ginger are associated with anticoagulant-related bleeding. Additionally, fish oil, ginseng, and saw palmetto also are thought to be associated with bleeding events, but randomized control trials (RCT) have not demonstrated an increased bleeding risk [

4].

Bronchoscopy is often conducted after discontinuation of dietary supplements. However, there is a lack of research investigating the optimal time of withdrawal and its impact on the risk of problems during bronchoscopy. We, therefore, aimed to determine the safety and withdrawal period for dietary supplements for patients undergoing bronchoscopy, with a particular focus on bleeding complications.

4. Discussion

Some dietary supplements can affect perioperative conditions and require a preoperative withdrawal period to avoid bleeding complications. Invasive bronchoscopy could have complications; in particular, dietary supplements with a bleeding risk should be noted. In this study, the 19 patients who underwent invasive bronchoscopy were regular users of dietary supplements with a risk of bleeding, including garlic ingredients, fish oil, and turmeric.

Raw garlic has not been found to reduce platelet function when consumed as part of a regular diet. Still, some garlic powders and garlic extracts derived from garlic or processed garlic oil contain allicin, alliin, ajoene, methyl allyl trisulfide, diaryl trisulfide, dimethyl trisulfide, vinyl disulfide, and non-sulfur steroid saponins, which all have anticoagulant effects [

20]. Because of the many case reports of surgical bleeding associated with garlic ingredients and RCTs in which garlic has been shown to reduce platelet function, garlic ingredients seem to have a bleeding risk with strong evidential support [

4,

21]. Fish oil contains high doses of the polyunsaturated omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and is commonly used to reduce cardiovascular events. In a large RCT, a group of patients with hypercholesterolemia who regularly used EPA had significantly fewer coronary events but more bleeding events than a group of patients who did not use EPA. Therefore, withdrawal of fish oil is recommended before surgery or invasive procedures [

5,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Conversely, a recent systematic review concluded that fish oil has antiplatelet effects in several RCTs but does not increase bleeding events [

26]. However, no RCTs have reported the bleeding risk related to fish oil use in bronchoscopy. Considering the risk of respiratory deterioration and asphyxiation due to massive bleeding during bronchoscopy, withdrawal of fish oil before bronchoscopy is strongly recommended.

In this study, we performed an invasive bronchoscopy in one patient who had taken a turmeric dietary supplement. The patient did not know the name of the supplement and could not identify it before the bronchoscopy, which was performed without suspending the supplement. It was later discovered during a medical interview with a pharmacist, when the patient was hospitalized for lung cancer surgery, that this dietary supplement contained various ingredients, including turmeric, maria thistle, and black pepper, which are suspected of having a bleeding risk [

4]. Turmeric, often used as a spice and coloring agent, contains a bioactive substance called curcumin [

27], reported to have properties such as antioxidant, hepatoprotective, cardioprotective, neuroprotective, anti-microbial, anti-tumor, and amelioration of dyslipidemia and ischemia–reperfusion disease [

27,

28]. Curcumin also inhibits platelet activity and aggregation [

27]. Turmeric has not been studied regarding its risk before bronchoscopy, and it should be withdrawn before bronchoscopy. In this case, we observed no severe complications; however, clinicians should be aware of dietary supplements containing turmeric and of supplements with unknown ingredients.

Chondroitin-glucosamine has been shown to cause prolonged prothrombin time when combined with warfarin in two cases, and over 40 cases showed an interaction between glucosamine and warfarin, reported by various drug-monitoring agencies [

4,

29,

30,

31]. In this study, there were nine cases in which the patient was a regular user of chondroitin-glucosamine undergoing invasive bronchoscopy. However, none of these patients were administered warfarin; therefore, these nine cases were not included in the list of dietary supplements with bleeding risk. No severe bleeding was observed in patients administered chondroitin-glucosamine.

Recommendations from the ASA and a report by Hodges and Kam indicate that the withdrawal period for dietary supplements should be no less than 2 weeks [

32]. Wong and Townley recommend a 7-day pause for garlic and ginseng, 2 weeks for echinacea and ginger, and 36 hours for ginkgo biloba before surgery [

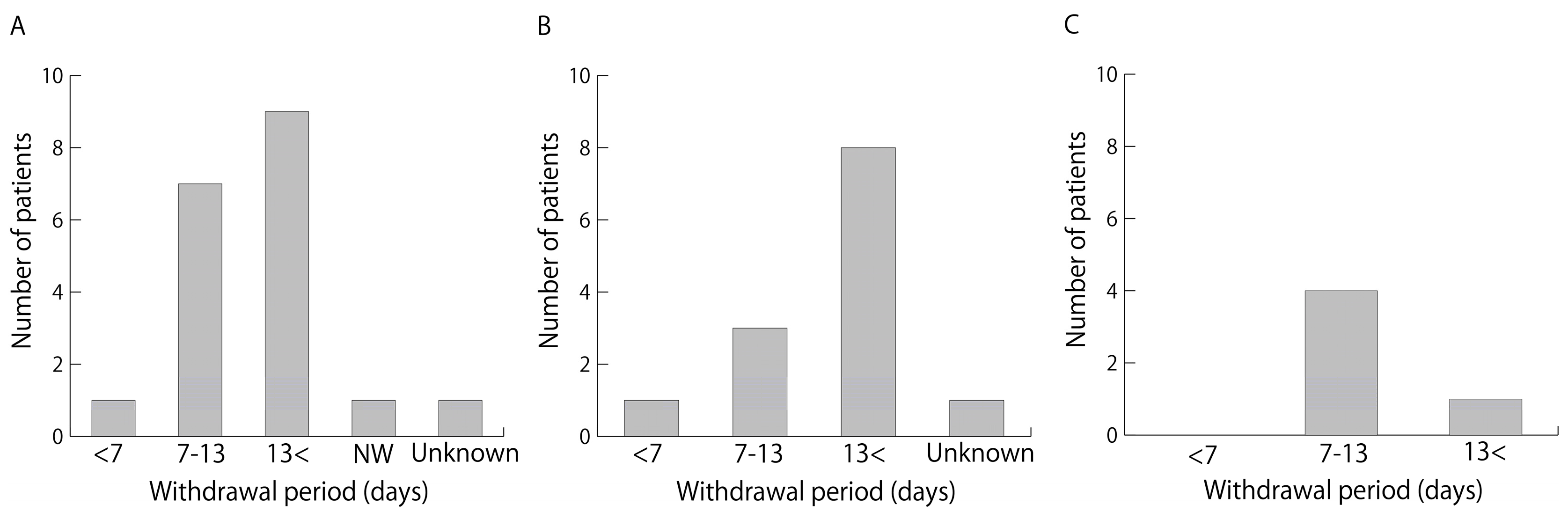

33]. However, because there are so many ingredients that are considered dietary supplements, it is difficult to verify each regarding the risk of perioperative complications such as bleeding and their duration of withdrawal. The duration of withdrawal has not been adequately studied and no reports have examined the duration of dietary supplement withdrawal before bronchoscopy. In this study, of the 19 patients who were regular users of dietary supplements with a risk of bleeding and who underwent invasive bronchoscopy, 18 discontinued dietary supplements before bronchoscopy. In one of these cases, the patient who regularly used a supplement with a garlic ingredient had only a 4-day withdrawal period before invasive bronchoscopy because of the urgent need to diagnose and treat lung cancer. The other 17 cases were performed with a withdrawal of at least 7 days, meeting the duration of withdrawal recommended for garlic components [

33]. As for fish oil, at least 1 or 2 weeks of withdrawal is recommended [

23,

24,

25]. The withdrawal period for fish oil in this study was at least 7 days in all patients.

Complications of bronchoscopy include minor bleeding (hemoptysis < 50 mL) in 0.19% and severe bleeding (hemoptysis > 50 mL) in 0.26% of cases [

34]; in transbronchial biopsy, the incidence of moderate bleeding is 1.7% [

5]. In a prospective cohort study, Herth et al. reported that transbronchial lung biopsies in patients taking aspirin showed moderate bleeding in 1.1% and severe bleeding in 0.9% of patients, but no significant difference was seen in incidence between a group of patients not taking aspirin and a group of patients taking aspirin [

35]. In a prospective cohort study conducted by Ernst et al., transbronchial lung biopsies in patients who were continuing to take clopidogrel or clopidogrel plus aspirin resulted in 34% incidence of moderate bleeding and 27% incidence of severe bleeding with a significantly higher rate than that of control group [

36]. A retrospective study reported that endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration in patients taking clopidogrel and aspirin resulted in a drop in hemoglobin (> 2 g) or rehospitalization within 48 hours due to bleeding or anemia in 8.7% of patients [

37]. Among the patients in this study who were regular users of dietary supplements and underwent invasive bronchoscopy, were taking antithrombotic medications but all had been off their medication for a sufficient period of time prior to bronchoscopy. There was no severe bleeding in any of the groups; however, 19.2% of the patients had moderate bleeding. The incidence of bleeding complications in this study was higher than that in previous reports on transbronchial lung biopsies and ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration in patients taking antiplatelet drugs [

35,

37]. However, this may be due to the small number of cases in this study, differences in patient backgrounds, and differences in the evaluation criteria for bleeding severity. The incidence of bleeding complications during bronchoscopy was not significantly different between the groups divided according to medication status and dietary supplement usage, suggesting that dietary supplements with bleeding risks, such as garlic and fish oil, have a similar risk of bleeding as patients who do not consume these dietary supplements when they are withdrawn for at least 7 days. However, the number of cases was small, and the inclusion of further cases is required.

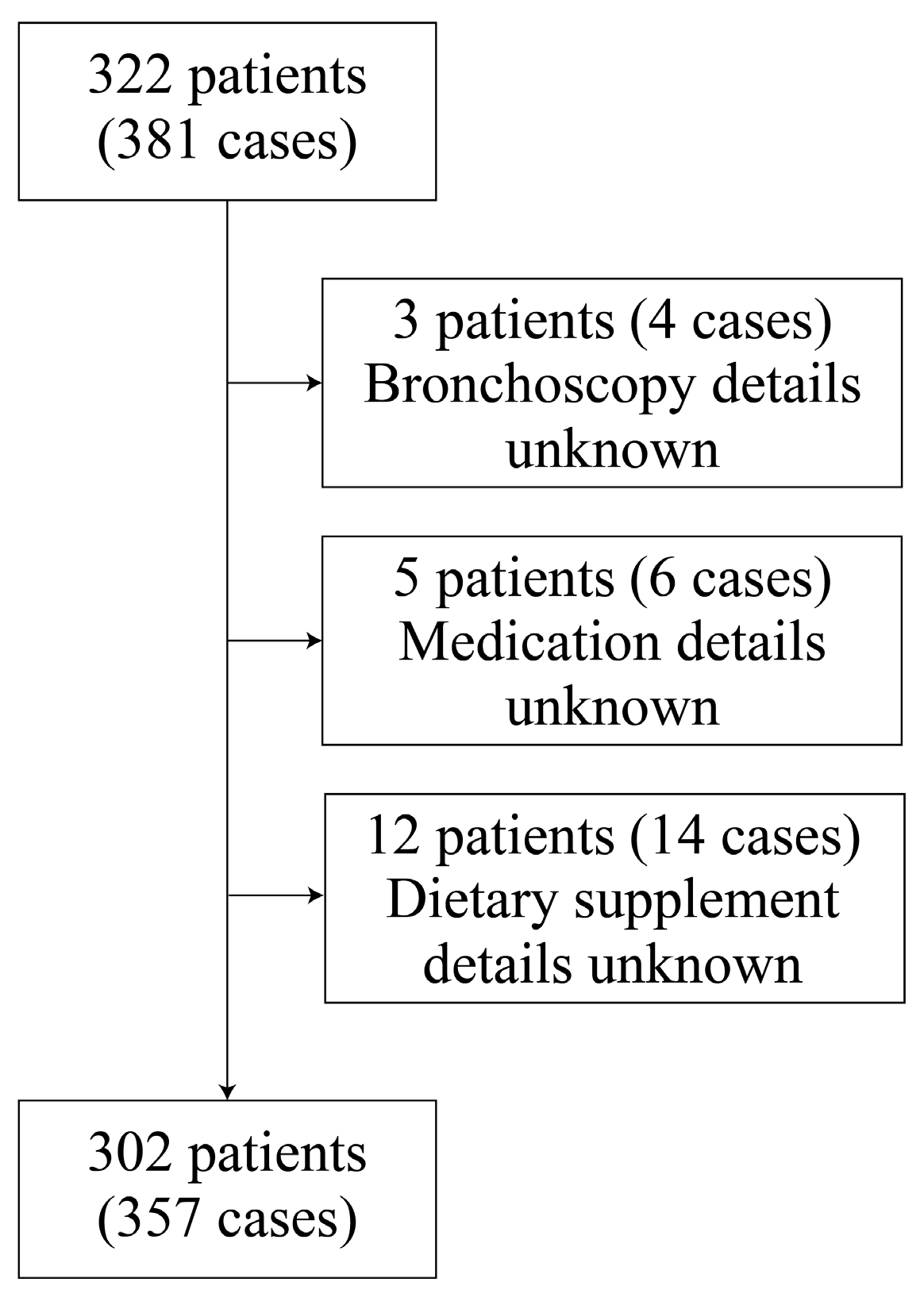

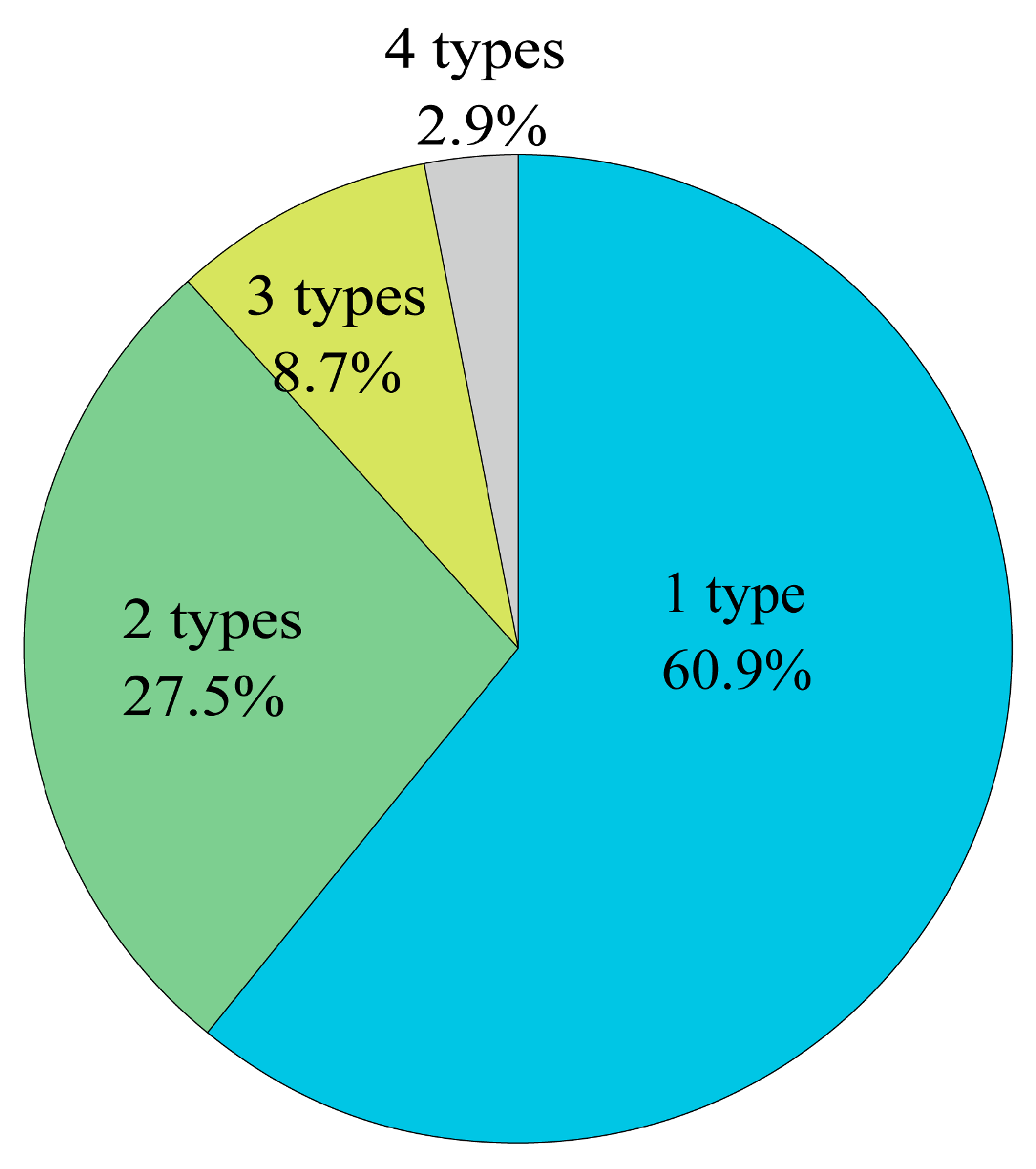

We could not identify the ingredients of the dietary supplements in six cases. The reason for this inadequate information was the lack of knowledge from the patient or healthcare provider. The patient did not know the name of the dietary supplement, and the healthcare provider did not ask enough about it. While healthcare providers need to be aware that some dietary supplements pose a bleeding risk, patients also need to be aware that some dietary supplements contain ingredients that might induce bleeding complications. Additionally, some dietary supplements contain more than one type of ingredient or the ingredients are unclear because of inadequate labeling. Before invasive bronchoscopy, it is crucial to pay close attention in collaboration with pharmacists and to stop using dietary supplements when there is uncertainty about their ingredients.

The limitations of this study that should be considered are its single-center retrospective design and the small number of patients taking dietary supplements with bleeding risk. Therefore, case bias may have affected the results. Further studies with larger numbers of patients from multiple facilities are needed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Naoki Kinoshita; Data curation, Naoki Kinoshita; Investigation, Naoki Kinoshita; Methodology, Naoki Kinoshita; Project administration, Akira Yamasaki; Resources, Kosuke Yamaguchi, Tomoya Harada, Tomohiro Sakamoto, Yoshihiro Funaki, Masaaki Yanai, Yasuhiko Teruya, Yuki Hirayama, Takafumi Nonaka, Hiroki Ishikawa, Genki Inui and Masahiro Kodani; Supervision, Akira Yamasaki; Writing – original draft, Naoki Kinoshita. All authors approved the manuscript for submission.