Submitted:

25 December 2024

Posted:

26 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

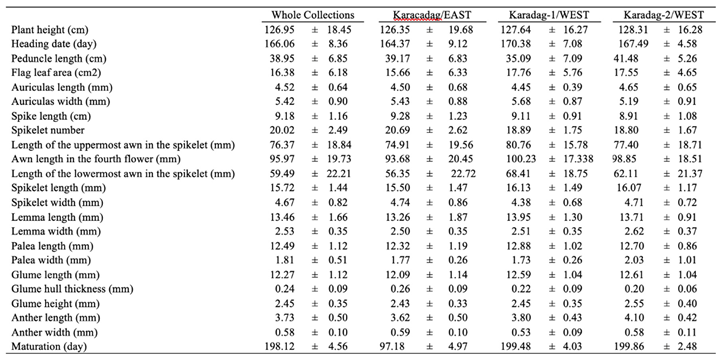

3.1. Agro-Morphological Variation in Wild Emmer Populations

3.2. Genetic Diversity Within and Between the Populations and Sub-Regions

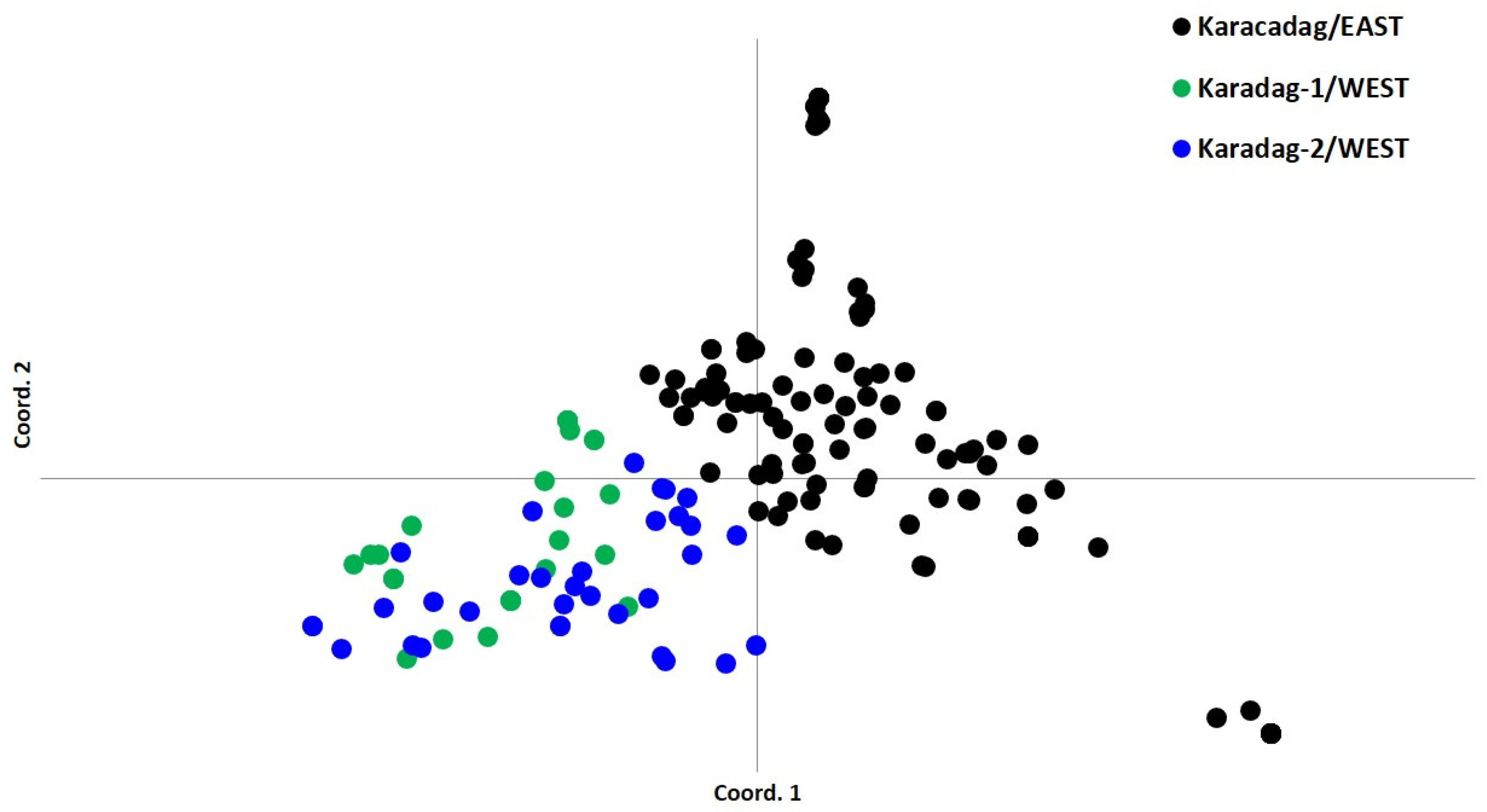

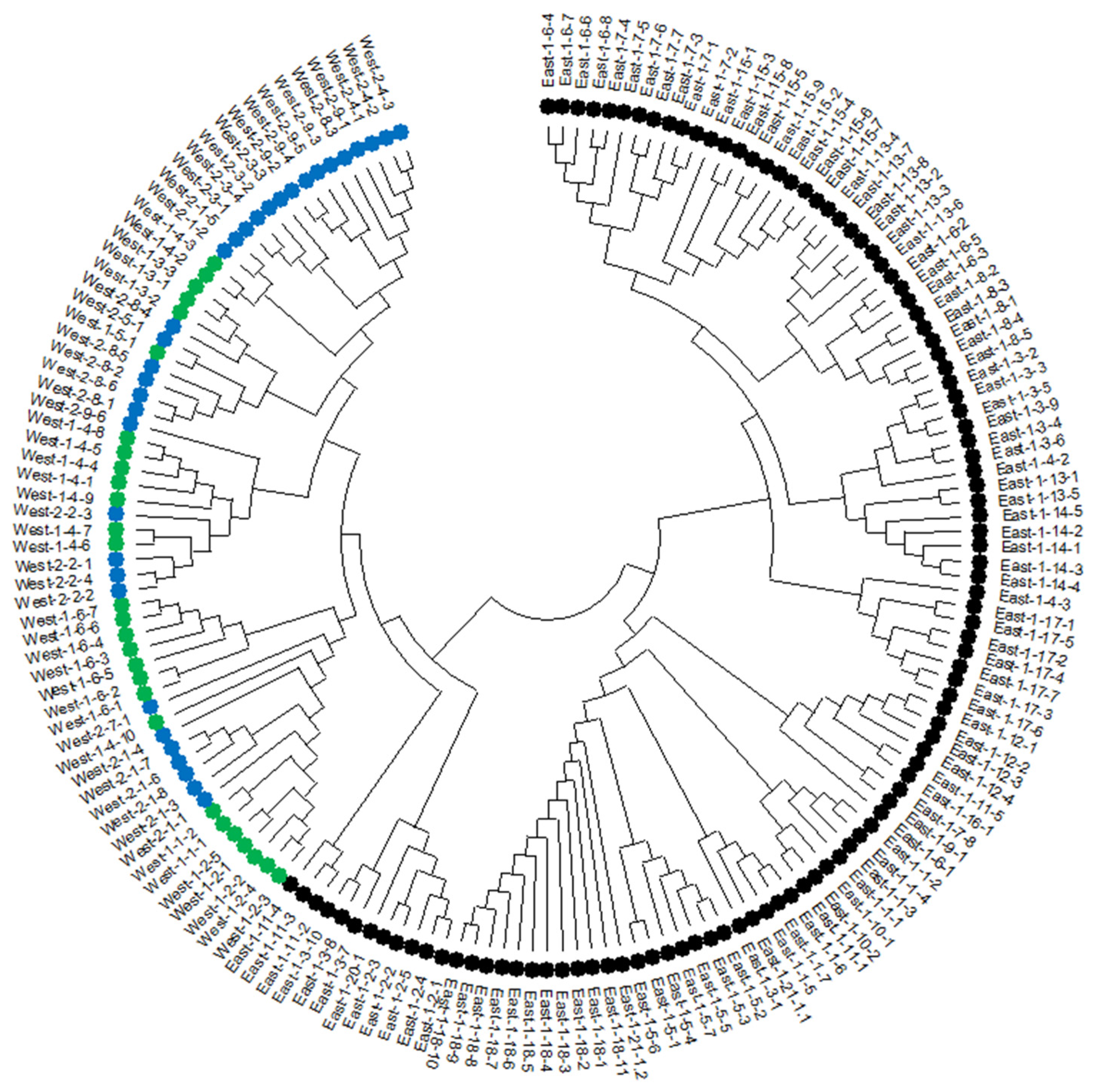

3.3. PCoA and Neighbor-Joining Grouping Patterns in Wild Emmer Populations

4. Discussion

4.1. Agro-Morphological Diversity

4.2. Genetic Diversity of In-Situ Populations

4.3. PCoA and Neighbor-Joining Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Maccaferri, M.; Harris, N.S.; Twardziok, S.O.; Pasam, R.K.; Gundlach, H.; Spannagl, M.; Ormanbekova, D.; Lux, T.; Prade, V.M.; Milner, S.G., et al. Durum wheat genome highlights past domestication signatures and future improvement targets. Nat Genet 2019, 51, 885-895. [CrossRef]

- Snowdon, R.J.; Wittkop, B.; Chen, T.-W.; Stahl, A. Crop adaptation to climate change as a consequence of long-term breeding. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 1613-1623. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Bai, S.; Li, H.; Sun, G.; Zhang, D.; Ma, F.; Zhao, X.; Nie, F.; Li, J.; Chen, L., et al. Introgressing the Aegilops tauschii genome into wheat as a basis for cereal improvement. Nature Plants 2021, 10.1038/s41477-021-00934-w. [CrossRef]

- Varshney, R.K.; Bohra, A.; Roorkiwal, M.; Barmukh, R.; Cowling, W.; Chitikineni, A.; Lam, H.-M.; Hickey, L.T.; Croser, J.; Edwards, D., et al. Rapid delivery systems for future food security. Nature Biotechnology 2021, 10.1038/s41587-021-01079-z. [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.W.; Nie, X.J.; Cui, L.C.; Deng, P.C.; Wang, M.X.; Song, W.N. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of Salinity Stress-Responsive miRNAs in Wild Emmer Wheat (Triticum turgidum ssp dicoccoides). Genes 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.H.; Sun, D.F.; Nevo, E. Wild emmer wheat, Triticum dicoccoides, occupies a pivotal position in wheat domestication process. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2011, 5, 1127-1143.

- Dong, P.; Wei, Y.M.; Chen, G.Y.; Li, W.; Wang, J.R.; Nevo, E.; Zheng, Y.L. Sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP) of wild emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccoides) in Israel and its ecological association. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2010, 38, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Lack, H.W.; Van Slageren, M. The discovery, typification and rediscovery of wild emmer wheat, Triticum turgidum subsp. dicoccoides (Poaceae). Willdenowia 2020, 50, 207-216. [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, H.; Willcox, G.; Graner, A.; Salamini, F.; Kilian, B. Geographic distribution and domestication of wild emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccoides). Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 2011, 58, 11-53. [CrossRef]

- Kantar, M.; Lucas, S.J.; Budak, H. miRNA expression patterns of Triticum dicoccoides in response to shock drought stress. Planta 2011, 233, 471-484. [CrossRef]

- Shavrukov, Y.; Langridge, P.; Tester, M.; Nevo, E. Wide genetic diversity of salinity tolerance, sodium exclusion and growth in wild emmer wheat, Triticum dicoccoides. Breed. Sci. 2010, 60, 426-435. [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Cui, L.; Lv, S.; Bian, J.; Wang, M.; Song, W.; Nie, X. Comprehensive evaluating of wild and cultivated emmer wheat (Triticum turgidum L.) genotypes response to salt stress. Plant Growth Regul 2017, 84, 261-273. [CrossRef]

- Soresi, D.; Bagnaresi, P.; Crescente, J.M.; Diaz, M.; Cattivelli, L.; Vanzetti, L.; Carrera, A. Genetic Characterization of a Fusarium Head Blight Resistance QTL from Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccoides. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 10.1007/s11105-020-01277-0. [CrossRef]

- Soresi, D.; Zappacosta, D.; Garayalde, A.; Irigoyen, I.; Basualdo, J.; Carrera, A. A Valuable QTL for Fusarium Head Blight Resistance from Triticum turgidum L. ssp dicoccoides has a Stable Expression in Durum Wheat Cultivars. Cereal Res. Commun. 2017, 45, 234-247. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, C.Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Zhou, X.L.; Lv, S.K.; Liu, X.L.; Kang, Z.S.; Ji, W.Q. Molecular mapping and marker development for the Triticum dicoccoides-derived stripe rust resistance gene YrSM139-1B in bread wheat cv. Shaanmai 139. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2016, 129, 369-376. [CrossRef]

- Sela, H.; Ezrati, S.; Ben-Yehuda, P.; Manisterski, J.; Akhunov, E.; Dvorak, J.; Breiman, A.; Korol, A. Linkage disequilibrium and association analysis of stripe rust resistance in wild emmer wheat (Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccoides) population in Israel. TAG. Theoretical and applied genetics. Theoretische und angewandte Genetik 2014, 127, 2453-2463. [CrossRef]

- Toktay, H.; Imren, M.; Elekcioglu, I.H.; Dababat, A.A. Evaluation of Turkish wild Emmers (Triticum dicoccoides Koern.) and wheat varieties for resistance to the root lesion nematodes (Pratylenchus thornei and Pratylenchus neglectus). Turkiye Entomoloji Dergisi-Turkish Journal of Entomology 2015, 39, 219-227.

- Saidou, M.; Wang, C.Y.; Alam, M.A.; Chen, C.H.; Ji, W.Q. Genetic analysis of powdery mildew resistance gene using ssr markers in common wheat originated from wild emmer (Triticum dicoccoides Thell). Turkish Journal of Field Crops 2016, 21, 10-15. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhang, D.Y.; Ouyang, S.H.; Xie, J.Z.; Wu, Q.H.; Wang, Z.Z.; Cui, Y.; Lu, P.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Z.J., et al. Dynamic evolution of resistance gene analogs in the orthologous genomic regions of powdery mildew resistance gene MlIW170 in Triticum dicoccoides and Aegilops tauschii. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2015, 128, 1617-1629. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.N.; Liu, N.N.; Wang, H.F.; Shi, X.H.; Li, F.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, W.D.; Guo, W.L.; Hu, Z.R.; Li, H.J., et al. Fine mapping of a powdery mildew resistance gene MlIW39 derived from wild emmer wheat (Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccoides). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 2469-2479. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, S.H.; Zhang, D.; Han, J.; Zhao, X.J.; Cui, Y.; Song, W.; Huo, N.X.; Liang, Y.; Xie, J.Z.; Wang, Z.Z., et al. Fine Physical and Genetic Mapping of Powdery Mildew Resistance Gene MlIW172 Originating from Wild Emmer (Triticum dicoccoides). Plos One 2014, 9. [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.; Ji, W.Q.; Wang, C.Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, B.J. High-density mapping and marker development for the powdery mildew resistance gene PmAS846 derived from wild emmer wheat (Triticum turgidum var. dicoccoides). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 124, 1549-1560. [CrossRef]

- Nevo, E.; Golenberg, E.; Beiles, A.; Brown, A.H.D.; Zohary, D. Genetic diversity and environmental associations of wild wheat, Triticum-dicoccoides, IN ISRAEL. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1982, 62, 241-254. [CrossRef]

- Poyarkova, H.; Gerechteramitai, Z.K.; Genizi, A. 2 variants of wild emmer (Triticum-dicoccoides) native to israel - morphology and distribution. Can. J. Bot.-Rev. Can. Bot. 1991, 69, 2772-2789. [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, K.; Nashef, K.; Ben-David, R. Agronomic and genetic characterization of wild emmer wheat (Triticum turgidum subsp. dicoccoides) introgression lines in a bread wheat genetic background. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 2017, 64, 1917-1926. [CrossRef]

- Arystanbekkyzy, M.; Nadeem, M.A.; Aktas, H.; Yeken, M.Z.; Zencirci, N.; Nawaz, M.A.; Ali, F.; Haider, M.S.; Tunc, K.; Chung, G., et al. Phylogenetic and Taxonomic Relationship of Turkish Wild and Cultivated Emmer (Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccoides) Revealed by iPBS-Retrotransposons Markers. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology 2019, 21, 155-163.

- Shizuka, T.; Mori, N.; Ozkan, H.; Ohta, S. Chloroplast DNA haplotype variation within two natural populations of wild emmer wheat (Triticum turgidumssp.dicoccoides) in southern Turkey. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 2015, 29, 423-430. [CrossRef]

- Ozbek, O.; Millet, E.; Anikster, Y.; Arslan, O.; Feldman, M. Comparison of the genetic structure of populations of wild emmer wheat, Triticum turgidum ssp dicoccoides, from Israel and Turkey revealed by AFLP analysis. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 2007, 54, 1587-1598. [CrossRef]

- Gerechteramitai, Z.K.; Sharp, E.L.; Reinhold, M. Temperature Sensitive genes for stripe rust resistance in triticum-dicoccoides indigenous to Israel. Phytopathology 1981, 71, 218-218.

- Gerechteramitai, Z.K.; Vansilfhout, C.H.; Grama, A.; Kleitman, F. YR15 - A NEW GENE FOR RESISTANCE TO PUCCINIA-STRIIFORMIS IN TRITICUM-DICOCCOIDES SEL G-25. Euphytica 1989, 43, 187-190. [CrossRef]

- Nevo, E.; Beiles, A.; Gutterman, Y.; Storch, N.; Kaplan, D. Genetic-resources of wild cereals in israel and vicinity.1. phenotypic variation within and between populations of wild wheat, Triticum-dicoccoides. Euphytica 1984, 33, 717-735. [CrossRef]

- Silfhout, C.H.; Grama, A.; Gerechter-Amitai, Z.K.; Kleitman, F. Resistance to yellow rust in Triticum dicoccoides. I. Crosses with susceptible Triticum durum. Netherlands Journal of Plant Pathology 1989, 95, 73-78. [CrossRef]

- Poyarkova, H. Morphology, geography and infraspecific taxonomics of Triticum-dicoccoides korn - a retrospective of 80 years of research. Euphytica 1988, 38, 11-23. [CrossRef]

- Nevo, E.; Krugman, T.; Beiles, A. Genetic-resources for salt tolerance in the wild progenitors of wheat (triticum-dicoccoides) and barley (Hordeum-spontaneum) IN ISRAEL. Plant Breeding 1993, 110, 338-341. [CrossRef]

- Kato, K.; Mori, Y.; Beiles, A.; Nevo, E. Geographical variation in heading traits in wild emmer wheat, Triticum dicoccoides.1. Variation in vernalization response and ecological differentiation. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1997, 95, 546-552. [CrossRef]

- Kato, K.; Tanizoe, C.; Beiles, A.; Nevo, E. Geographical variation in heading traits in wild emmer wheat, Triticum dicoccoides. II. Variation in heading date and adaptation to diverse eco-geographical conditions. Hereditas 1998, 128, 33-39. [CrossRef]

- Fahima, T.; Sun, G.L.; Beharav, A.; Krugman, T.; Beiles, A.; Nevo, E. RAPD polymorphism of wild emmer wheat populations, Triticum dicoccoides, in Israel. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1999, 98, 434-447. [CrossRef]

- Belyayev, A.; Raskina, O.; Korol, A.; Nevo, E. Coevolution of A and B genomes in allotetraploid Triticum dicoccoides. Genome / National Research Council Canada = Genome / Conseil national de recherches Canada 2000, 43, 1021-1026. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.C.; Fahima, T.; Peng, J.H.; Roder, M.S.; Kirzhner, V.M.; Beiles, A.; Korol, A.B.; Nevo, E. Edaphic microsatellite DNA divergence in wild emmer wheat, Triticum dicoccoides, at a microsite: Tabigha, Israel. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2000, 101, 1029-1038. [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.H.; Fahima, T.; Roder, M.S.; Huang, Q.Y.; Dahan, A.; Li, Y.C.; Grama, A.; Nevo, E. High-density molecular map of chromosome region harboring stripe-rust resistance genes YrH52 and Yr15 derived from wild emmer wheat, Triticum dicoccoides. Genetica 2000, 109, 199-210. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.C.; Krugman, T.; Fahima, T.; Beiles, A.; Korol, A.B.; Nevo, E. Spatiotemporal allozyme divergence caused by aridity stress in a natural population of wild wheat, Triticum dicoccoides, at the Ammiad microsite, Israel. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2001, 102, 853-864. [CrossRef]

- Fahima, T.; Roder, M.S.; Wendehake, K.; Kirzhner, V.M.; Nevo, E. Microsatellite polymorphism in natural populations of wild emmer wheat, Triticum dicoccoides, in Israel. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2002, 104, 17-29. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.C.; Roder, M.S.; Fahima, T.; Kirzhner, V.M.; Beiles, A.; Korol, A.B.; Nevo, E. Climatic effects on microsatellite diversity in wild emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccoides) at the Yehudiyya microsite, Israel. Heredity 2002, 89, 127-132. [CrossRef]

- Buerstmayr, H.; Stierschneider, M.; Steiner, B.; Lemmens, M.; Griesser, M.; Nevo, E.; Fahima, T. Variation for resistance to head blight caused by Fusarium graminearum in wild emmer (Triticum dicoccoides) originating from Israel. Euphytica 2003, 130, 17-23. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.C.; Fahima, T.; Roder, M.S.; Kirzhner, V.M.; Beiles, A.; Korol, A.B.; Nevo, E. Genetic effects on microsatellite diversity in wild emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccoides) at the Yehudiyya microsite, Israel. Heredity 2003, 90, 150-156. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.S.; Khan, K.; Klindworth, D.L.; Faris, J.D.; Nygard, G. Chromosomal location of genes for novel glutenin subunits and gliadins in wild emmer wheat (Triticum turgidum L. var. dicoccoides). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 108, 1221-1228. [CrossRef]

- Anikster, Y.; Manisterski, J.; Long, D.L.; Leonard, K.J. Leaf rust and stem rust resistance in Triticum dicoccoides populations in Israel. Plant Dis. 2005, 89, 55-62. [CrossRef]

- Syouf, M.; Abu-Irmaileh, B.E.; Valkoun, J.; Bdour, S. Introgression from durum wheat landraces in wild emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccoides (Korn. ex Asch et Graebner) Schweinf). Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 2006, 53, 1165-1172. [CrossRef]

- Hua, W.; Liu, Z.J.; Zhu, J.; Xie, C.J.; Yang, T.M.; Zhou, Y.L.; Duan, X.Y.; Sun, Q.X.; Liu, Z.Y. Identification and genetic mapping of pm42, a new recessive wheat powdery mildew resistance gene derived from wild emmer (Triticum turgidum var. dicoccoides). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009, 119, 223-230. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.J.; Zhu, J.; Cui, Y.; Liang, Y.; Wu, H.B.; Song, W.; Liu, Q.; Yang, T.M.; Sun, Q.X.; Liu, Z.Y. Identification and comparative mapping of a powdery mildew resistance gene derived from wild emmer (Triticum turgidum var. dicoccoides) on chromosome 2BS. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 124, 1041-1049. [CrossRef]

- Sela, H.; Ezrati, S.; Ben-Yehuda, P.; Manisterski, J.; Akhunov, E.; Dvorak, J.; Breiman, A.; Korol, A. Linkage disequilibrium and association analysis of stripe rust resistance in wild emmer wheat (Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccoides) population in Israel. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2014, 127, 2453-2463. [CrossRef]

- Domb, K.; Keidar, D.; Yaakov, B.; Khasdan, V.; Kashkush, K. Transposable elements generate population-specific insertional patterns and allelic variation in genes of wild emmer wheat (Triticum turgidum ssp dicoccoides). BMC Plant Biol 2017, 17. [CrossRef]

- Vuorinen, A.L.; Kalendar, R.; Fahima, T.; Korpelainen, H.; Nevo, E.; Schulman, A.H. Retrotransposon-Based Genetic Diversity Assessment in Wild Emmer Wheat (Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccoides). Agronomy-Basel 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- Salamini, F.; Ozkan, H.; Brandolini, A.; Schafer-Pregl, R.; Martin, W. Genetics and geography of wild cereal domestication in the near east. Nat Rev Genet 2002, 3, 429-441. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.J.; Doyle, J.L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue; 1987.

- Ozkan, H.; Kafkas, S.; Sertac Ozer, M.; Brandolini, A. Genetic relationships among South-East Turkey wild barley populations and sampling strategies of Hordeum spontaneum. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005, 112, 12-20. [CrossRef]

- Schuelke, M. An economic method for the fluorescent labeling of PCR fragments. Nature biotechnology 2000, 18, 233-234. [CrossRef]

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, P.E. GENALEX 6: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2006, 6, 288-295. [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S.M.; Toulmin, C. Food Security: The Challenge of Feeding 9 Billion People. Science 2010, 327, 812-818. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Paleo, L.; Ravetta, D.A. Allocation patterns and phenology in wild and selected accessions of annual and perennial Physaria (Lesquerella, Brassicaceae). Euphytica 2012, 186, 289-302. [CrossRef]

- Feuillet, C.; Langridge, P.; Waugh, R. Cereal breeding takes a walk on the wild side. Trends in Genetics 2007, 24, 24-32. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, R.; Sayre, K.D.; Govaerts, B.; Gupta, R.; Subbarao, G.V.; Ban, T.; Hodson, D.; Dixon, J.A.; Ortiz-Monasterio, J.I.; Reynolds, M. Climate change: Can wheat beat the heat? Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment 2008, 126, 46-58. [CrossRef]

- El Haddad, N.; Kabbaj, H.; Zaïm, M.; El Hassouni, K.; Tidiane Sall, A.; Azouz, M.; Ortiz, R.; Baum, M.; Amri, A.; Gamba, F., et al. Crop wild relatives in durum wheat breeding: Drift or thrift? Crop Science 2021, 61, 37-54. [CrossRef]

- Castaneda-Alvarez, N.P.; Khoury, C.K.; Achicanoy, H.A.; Bernau, V.; Dempewolf, H.; Eastwood, R.J.; Guarino, L.; Harker, R.H.; Jarvis, A.; Maxted, N., et al. Global conservation priorities for crop wild relatives. Nat Plants 2016, 2, 16022. [CrossRef]

- Harlan, J.R.; Wet, J.M.J. TOWARD A RATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF CULTIVATED PLANTS. Taxon 1971, 20, 509-517. [CrossRef]

- Chhuneja, P.; Arora, J.K.; Kaur, P.; Kaur, S.; Singh, K. Characterization of wild emmer wheat Triticum dicoccoides germplasm for vernalization alleles. Journal of Plant Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2015, 24, 249-253. [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.H.; Sun, D.; Nevo, E. Domestication evolution, genetics and genomics in wheat. Molecular Breeding 2011, 28, 281-301. [CrossRef]

- Nevo, E. Genetic resources of wild emmer, Triticum dicoccoides, for wheat improvement in the third millennium. Isr. J. Plant Sci. 2001, 49, S77-S91. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K. Göbekli Tepe; Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayınları: 2007.

- Dietrich, O.; Heun, M.; Notroff, J.; Schmidt, K.; Zarnkow, M. The role of cult and feasting in the emergence of Neolithic communities. New evidence from Göbekli Tepe, south-eastern Turkey. Antiquity 2012, 86, 674-695. [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, C.; Luo, M.-C.; Ramasamy, R.; Dawson, M.; Gill, B.S.; Korol, A.B.; Distelfeld, A.; Dvorak, J. A High-Density Genetic Map of Wild Emmer Wheat from the Karaca Dağ Region Provides New Evidence on the Structure and Evolution of Wheat Chromosomes. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.Y.; Zhu, K.Y.; Dong, L.L.; Liang, Y.; Li, G.Q.; Fang, T.L.; Guo, G.H.; Wu, Q.H.; Xie, J.Z.; Chen, Y.X., et al. Wheat powdery mildew resistance gene Pm64 derived from wild emmer (Triticum turgidum var. dicoccoides) is tightly linked in repulsion with stripe rust resistance gene Yr5. Crop Journal 2019, 7, 761-770. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Nazarian, F. The inheritance and chromosomal location of morphological traits in wild wheat, Triticum turgidum L. ssp dicoccoides. Euphytica 2007, 158, 103-108. [CrossRef]

- Rawale, K.S.; Khan, M.A.; Gill, K.S. The novel function of the Ph1 gene to differentiate homologs from homoeologs evolved in Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccoides via a dramatic meiosis-specific increase in the expression of the 5B copy of the C-Ph1 gene. Chromosoma 2019, 128, 561-570. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Hu, X.; Islam, S.; She, M.Y.; Peng, Y.C.; Yu, Z.T.; Wylie, S.; Juhasz, A.; Dowla, M.; Yang, R.C., et al. New insights into the evolution of wheat avenin-like proteins in wild emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccoides). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2018, 115, 13312-13317. [CrossRef]

- Negisho, K.; Shibru, S.; Pillen, K.; Ordon, F.; Wehner, G. Genetic diversity of Ethiopian durum wheat landraces. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0247016. [CrossRef]

- Teklu, Y.; Hammer, K.; Röder, M.S. Simple sequence repeats marker polymorphism in emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccon Schrank): Analysis of genetic diversity and differentiation. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 2007, 54, 543-554. [CrossRef]

- Harlan, J.R.; Zohary, D. Distribution of wild wheats and barley. Science 1966, 153, 1074-1080. [CrossRef]

- Zohary, D.; Hopf, M. Domestication of plants in the Old World: The origin and spread of cultivated plants in West Asia, Europe and the Nile Valley; Oxford university press: 2000.

- Hegde, S.G.; Valkoun, J.; Waines, J.G. Genetic diversity in wild wheats and goat grass. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2000, 101, 309-316. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Bernardo, R. Molecular marker diversity among current and historical maize inbreds. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2001, 103, 613-617. [CrossRef]

- Ozbek, O.; Millet, E.; Anikster, Y.; Arslan, O.; Feldman, M. Spatio-temporal genetic variation in populations of wild emmer wheat, Triticum turgidum ssp dicoccoides, as revealed by AFLP analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2007, 115, 19-26. [CrossRef]

| Collection No | Collection Locality | Zone | Altitude (m) | Latitude (°N) | Longitude (°E) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24.5 km SW from Diyarbakır to Ovadag | East1 | 780 | 37°47′38″ | 40°12′14″ |

| 2 | 12.9 km NW from Ovadag to Pirinçlik | East1 | 1007 | 37°47′31″ | 39°57′18″ |

| 3 | 18.5 km NW from Ovadag to Pirinçlik | East1 | 920 | 37°49′17″ | 39°59′34″ |

| 4 | 20.1 km SW from Pirinçlik | East1 | 1080 | 37°52′02″ | 39°51′05″ |

| 5 | 20 km SW from Pirinçlik | East1 | 1260 | 37°50′40″ | 39°47′58″ |

| 6 | 2.9 km NE from Karabahçe to Pirinçlik | East1 | 1300 | 37°49′12″ | 39°46′29″ |

| 7 | 41.2 km SW from Pirinçlik | East1 | 1250 | 37°46′42″ | 39°44′50″ |

| 8 | 6.3 km N from Karabahçe (42.9 km W from Diyarbakır to Siverek) | East1 | 1070 | 37°50′21″ | 39°43′23″ |

| 9 | 4.6 km SW from Karabahçe | East1 | 1180 | 37°46′19″ | 39°44′03″ |

| 10 | 17.9 km SW from Karabahçe | East1 | 1160 | 37°44′29″ | 39°42′50″ |

| 11 | 21.7 km SW from Karabahçe | East1 | 1235 | 37°42′51″ | 39°44′03″ |

| 12 | 37.9 km SW from Karabahçe | East1 | 1170 | 37°39′49″ | 39°42′49″ |

| 13 | 37.9 km SW from Karabahçe | East1 | 1180 | 37°36′27″ | 39°43′41″ |

| 14 | 41.6 km SW from Karabahçe | East1 | 1170 | 37°35′08″ | 39°44′36″ |

| 15 | 48.7 km SW from Karabahçe | East1 | 1030 | 37°33′09″ | 39°42′06″ |

| 16 | 27.6 km SW from Karacadag (69.6 km SW from Karabahçe) | East1 | 950 | 37°37′40″ | 39°33′40″ |

| 17 | 30.2 km SW from Çermik to Siverek | East1 | 800 | 38°00′56″ | 39°22′11″ |

| 18 | Siverek Karakeçi Road Azemi Village | East1 | 733 | 37°36′51″ | 39°20′12″ |

| 19 | Karakeçi road | East1 | 737 | 37°33′27″ | 39°20′35″ |

| 20 | Karakeçi grassland | East1 | 758 | 37°32′22″ | 39°21′52″ |

| 21 | 5km from Siverek to Siverek Hilvan Road | East1 | 645 | 37°42′23″ | 39°16′34″ |

| 22 | 72 km SE from Turkoglu SE (W of Karadag) | West1 | 800(853) | 37°19′′46″ | 37°16′29″ |

| 23 | 72 km SE from Turkoglu SE (W of Karadag) | West1 | 800(853) | 37°19′′46″ | 37°16′29″ |

| 24 | 34 km ESE from Narlı (WSW of Karadag) | West1 | 840 (877) | 37°18′53″ | 37°15′41″ |

| 25 | 34 km ESE from Narlı (WSW of Karadag) | West1 | 780 (813) | 37°20′12″ | 37°17′53″ |

| 26 | 39 km ESE from Narlı (SW of Karadag) | West1 | 760 (793) | 37°17′06″ | 37°17′39″ |

| 27 | 39 km ESE from Narlı (SW of Karadag) | West1 | 760 (793) | 37°17′06″ | 37°17′39″ |

| 28 | Between Kahramanmaraş Kelleş village and Yiğitce village | West1 | 791 | 37°20′25″ | 37°17′54″ |

| 29 | Between Gaziantep Tekirsin village and Dundarlı village | West1 | 882 | 37°15′20″ | 37°23′26″ |

| 30 | 37 km NE from Kilis to Gaziantep | West2 | 830 | 37°20′19″ | 37°16′50″ |

| 31 | 39 km NE from Kilis to Gaziantep | West2 | 920 | 37°19′50″ | 37°18′51″ |

| 32 | 41 km NE from Kilis to Gaziantep | West2 | 770 | 37°24′23″ | 37°25′47″ |

| 33 | 42 km NE from Kilis to Gaziantep | West2 | 750 | 37°24′58″ | 37°24′50″ |

| 34 | 58 km NE from Kilis to Gaziantep | West2 | 720 | 37°16′01″ | 37°30′52″ |

| 35 | 59 km NE from Kilis to Gaziantep | West2 | 770 | 37°15′33″ | 37°29′03″ |

| 36 | 21 km NE from Kilis to Gaziantep | West2 | 620 | 36°45′52″ | 37°15′04″ |

| 37 | 24 km NE from Kilis to Gaziantep | West2 | 700 | 36°52′20″ | 37°12′12″ |

| 38 | 25 km NE from Kilis to Gaziantep | West2 | 830 | 36°33′25″ | 37°11′57″ |

| Name | Ch | Motif | Forward Primer sequence | Reverse Primer sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cfa2219 | 1A | (GT)21 | TCTGCCGAGTCACTTCATTG | GACAAGGCCAGTCCAAAAGA |

| wmc312 | 1A | (GA)10 | TGTGCCCGCTGGTGCGAAG | CCGACGCAGGTGAGCGAAG |

| wmc658 | 2A | ---- | CTCATCGTCCTCCTCCACTTTG | GCCATCCGTTGACTTGAGGTTA |

| wmc313 | 4A | (CA)18 | GCAGTCTAATTATCTGCTGGCG | GGGTCCTTGTCTACTCATGTCT |

| wmc110 | 5A | (GT)11 | GCAGATGAGTTGAGTTGGATTG | GTACTTGGAAACTGTGTTTGGG |

| cfa2190 | 5A | (TC)31 | CAGTCTGCAATCCACTTTGC | AAAAGGAAACTAAAGCGATGGA |

| wmc626 | 1B | ---- | AGCCCATAAACATCCAACACGG | AGGTGGGCTTGGTTACGCTCTC |

| gwm498 | 1B | ---- | GGTGGTATGGACTATGGACACT | GGTGGTATGGACTATGGACACT |

| wmc128 | 1B | (GA)10 | CGGACAGCTACTGCTCTCCTTA | CTGTTGCTTGCTCTGCACCCTT |

| wmc149 | 2B | (CT)24 | ACAGACTTGGTTGGTGCCGAGC | ATGGGCGGGGGTGTAGAGTTTG |

| wmc332 | 2B | (CT)12 | CATTTACAAAGCGCATGAAGCC | GAAAACTTTGGGAACAAGAGCA |

| gwm335 | 5B | --- | CGTACTCCACTCCACACGG | CGGTCCAAGTGCTACCTTTC |

| gwm630 | 6B | (GT)16 | GTGCCTGTGCCATCGTC | CGAAAGTAACAGCGCAGTGA |

| gwm146 | 7B | --- | CCAAAAAAACTGCCTGCATG | CTCTGGCATTGCTCCTTGG |

| wmc76 | 7B | (GT)19 | CTTCAGAGCCTCTTTCTCTACA | CTGCTTCACTTGCTGATCTTTG |

| gwm333 | 7B | (GA)19 | GCCCGGTCATGTAAAACG | TTTCAGTTTGCGTTAAGCTTTG |

| Source | df | SS | MS | Est. Var. | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among Pops | 2 | 439.551 | 219.776 | 4.429 | 16 |

| Within Pops | 166 | 3803.206 | 22.911 | 22.911 | 84 |

| Total | 168 | 4242.757 | 27.340 | 100 |

| Population | Karacadag/EAST | Karacadag-1/WEST | Karacadag-2/WEST |

| Karacadag/EAST | --- | 0.518 | 0.539 |

| Karadag-1/WEST | 0.484 | --- | 0.214 |

| Karadag-2/WEST | 0.463 | 0.788 | --- |

| Pops | N | Na | Ne | I | He | uHe |

| Karacadag/EAST | 108 | 9.938 ± 1.871 | 5.470 ± 0.869 | 1.692 ± 0.177 | 0.725 ± 0.046 | 0.729± 0.046 |

| Karadag-1/WEST | 28 | 3.938 ± 0.470 | 2.747 ± 0.308 | 1.030 ± 0.118 | 0.561 ± 0.051 | 0.572 ± 0.052 |

| Karadag-2/WEST | 33 | 6.125 ± 0.861 | 4.135 ± 0.644 | 1.348 ± 0.181 | 0.621 ± 0.070 | 0.632 ± 0.071 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).