Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Method

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. DNA Extraction

| Accession ID | Plant Species | Genbank Code | Country Of Origin | Collsite | Lat (N) | Long (E) | Elevation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WE 270 | T. dicoccoides | PI 428089 | TUR | 37 km NE from kilis to Gaziantep | 37°20'19'' | 37°16'50'' | 830 |

| WE 5 | T. dicoccoides | PI 428023 | TUR | 36.2 km west of Diyarbakir in the Karacadag | 37°53'00'' | 39°52'00'' | 1200 |

| WE 230 | T. dicoccoides | PI 428046 | TUR | 12.9 km NW from Ovadag to Pirinclik | 37°47'31'' | 39°57'18'' | 1007 |

| WE 28 | T. dicoccoides | PI 428089 | TUR | 20.2 km east of Siverek | 37°43'00'' | 39°30'00'' | 1200 |

| WE 262 | T. dicoccoides | PI 656872 | TUR | 34 km ESE from Narli (WSW of Karadağ) | 37°20'12'' | 37°17'53'' | 780 (813) |

| WE 14 | T. dicoccoides | PI 428051 | TUR | 36.2 km west of Diyarbakir in the Karacadag | 37°53’00’’ | 39°52’00’’ | 1200 |

| WE 264 | T. dicoccoides | TUR | 37 km NE from Kilis to Gaziantep | 37°20'19'' | 37°16'50'' | 830 | |

| WE 274 | T. dicoccoides | TUR | Siverek Karakeçi Road Azemi Village | 37° 36' 51'' | 39° 20' 12'' | 733 | |

| WE 164 | T. dicoccoides | PI 654321 | TUR | 4km south of Siverek on Karakecili road | 37° 43’05’’ | 39° 19’37’’ | 720 |

| WE 157 | T. dicoccoides | PI 554581 | TUR | 25 km southwest of Diyarbakir | 37° 45’00’’ | 40° 06’00’’ | 1000 |

| WE 114 | T. dicoccoides | PI 538646 | TUR | 36.2 km west of Diyarbakir in the Karacadag | 37° 53’00’’ | 39° 52’00’’ | 1200 |

| WE 159 | T. dicoccoides | PI 554583 | TUR | 3 km southeast of the Junction of Karacadag Mt. road and Diyarbakir highway | 37° 47’00’’ | 39° 47’00’’ | 1350 |

| WE 154 | T. dicoccoides | PI 538713 | LBN | between Ain Harsch and Ain Ata | 33° 26’00’’ | 35° 46’00’’ | 1192 |

| WE 169 | T. dicoccoides | TRI 18478, PI 427998 | LBN | zwischen Kfarkouk und Aiha | 33° 31’00’’ | 35° 52’00’’ | 1216 |

| WE 193 | T. dicoccoides | TRI 18530, PI 538706 | LBN | zwischen Aiha und Kfarkouk, ca. 1 km von Aiha | 33° 30’00’’ | 35° 52’00’’ | 1216 |

| WE 150 | T. dicoccoides | PI 538703 | LBN | near Rashaya | 33° 30’04’’ | 35° 50’22’’ | 1000 |

| WE 41 | T. dicoccoides | PI 428133 | LBN | Aiha-Kfarkouk, above 'sahlet' | 33° 31’00’’ | 35° 52’00’’ | 1141 |

| WE 149 | T. dicoccoides | PI 538702 | LBN | near Rashaya | 33° 30’04’’ | 35° 50’22’’ | 1000 |

| WE 151 | T. dicoccoides | PI 538704 | LBN | near Rashaya | 33° 30’04’’ | 35° 50’22’’ | 1000 |

| WE 46 | T. dicoccoides | PI 428143 | LBN | between Rashaya and Aiha | 33° 30’00’’ | 35° 50’00’’ | 1000 |

| WE 1 | T. dicoccoides | CItr 17675 | LBN | outskirts of Rashaya | 33° 30’04’’ | 35° 50’22’’ | 1000 |

| WE 179 | T. dicoccoides | TRI 18499, PI 470979 | LBN | Mt. Hermon | 33° 25’00’’ | 35° 52’00’’ | 2655 |

| WE 34 | T. dicoccoides | PI 428105 | ISR | 1 to 2 km south of Rosh Pinna towards Safad | 32° 58’00’’ | 35° 32’00’’ | 549 |

| WE 145 | T. dicoccoides | PI 538696 | ISR | Between 'En haShofet and Daliyya | 32° 35’00’’ | 35° 03’00’’ | 122 |

| WE 127 | T. dicoccoides | PI 538670 | ISR | Afula-Tiberias | 32° 36’40’’ | 35° 17’30’’ | 300 |

| WE 139 | T. dicoccoides | PI 538690 | ISR | near Safad on the road to Rosh Pinna | 32° 58’00’’ | 35° 29’40’’ | 800 |

| WE 134 | T. dicoccoides | PI 538679 | ISR | Afula-Tiberias | 32° 36’40’’ | 35° 17’30’’ | 300 |

| WE 61 | T. dicoccoides | PI 466972 | ISR | Bat Shelomo | 32° 35’48’’ | 35° 00’07’’ | 105 |

| WE 59 | T. dicoccoides | PI 466969 | ISR | Bat Shelomo | 32° 35’48’’ | 35° 00’07’’ | 105 |

| WE 62 | T. dicoccoides | PI 466974 | ISR | Bat Shelomo | 32° 35’48’’ | 35° 00’07’’ | 105 |

| WE 267 | T. dicoccoides | PI 538696 | ISR | Between 'En haShofet and Daliyya | 32° 35’00’’ | 35° 03’00’’ | 122 |

| WE 35 | T. dicoccoides | PI 428112 | ISR | 1 to 2 km south of Rosh Pinna towards Safad | 32° 58’00’’ | 35° 32’00’’ | 549 |

| WE 87 | T. dicoccoides | PI 471041 | ISR | Kokhav haShahar | 31° 57’00’’ | 35° 20’00’’ | 696 |

| WE 51 | T. dicoccoides | PI 466943 | SYR | Kazrin | 32° 59’24’’ | 35° 41’24’’ | 259 |

| WE 80 | T. dicoccoides | PI 470956 | SYR | Kazrin | 32° 59’24’’ | 35° 41’24’’ | 259 |

| WE 184 | T. dicoccoides | TRI 18506, PI487255 | SYR | Damaskus Provinz | 33° 45’00’’ | 36° 05’00’’ | 1240 |

| WE 186 | T. dicoccoides | TRI 18508, PI 487262 | SYR | Damaskus Provinz | 33° 40’00’’ | 36° 02’00’’ | 1300 |

| WE 96 | T. dicoccoides | PI 487260 | SYR | 32km from Sweida between Sale and Malah | 32° 38’52’’ | 36° 47’24’’ | 1530 |

| WE 93 | T. dicoccoides | PI 487254 | SYR | Nawa | 32° 52’10’’ | 36° 01’51’’ | 551 |

| WE 98 | T. dicoccoides | PI 487264 | SYR | Aleppo-Abeen road after Aleppo-Afrin road, Aleppo Province | 36° 30’00’’ | 37° 00’00’’ | 350 |

| WE 76 | T. dicoccoides | PI 470945 | SYR | Kazrin | 32° 59’24’’ | 35° 41’24’’ | 259 |

| WE 185 | T. dicoccoides | TRI 18507, PI 487261 | SYR | Es Suweida (Soud) | 32° 38’00’’ | 36° 46’00’’ | 1450 |

| WE 292 | T.durum | PI 466947 | Iran | ||||

| WE 294 | T. durum | Buckzafıro | Arj | ||||

| WE 293 | T. durum | PI 656872 | TUR | 112km northwest of Maras | |||

| WE 291 | T. durum | PI 654317 | TUR | ||||

| WE 289 | T. durum | Landrace | Italy |

2.3. CAAT-PCR and SCoT-PCR Amplification

2.4. Data Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Polymorphism Values for the Entire Set of Genotypes

3.2. Polymorphism Values Calculated Basen on the Collected Region of Accessions

3.3. Parameters Obtained Using CAAT Molecular Markers

3.4. Parameters Obtained Using SCoT Molecular Markers

3.5. Mean Genetic Diversity Parameters for CAAT and SCoT Markers

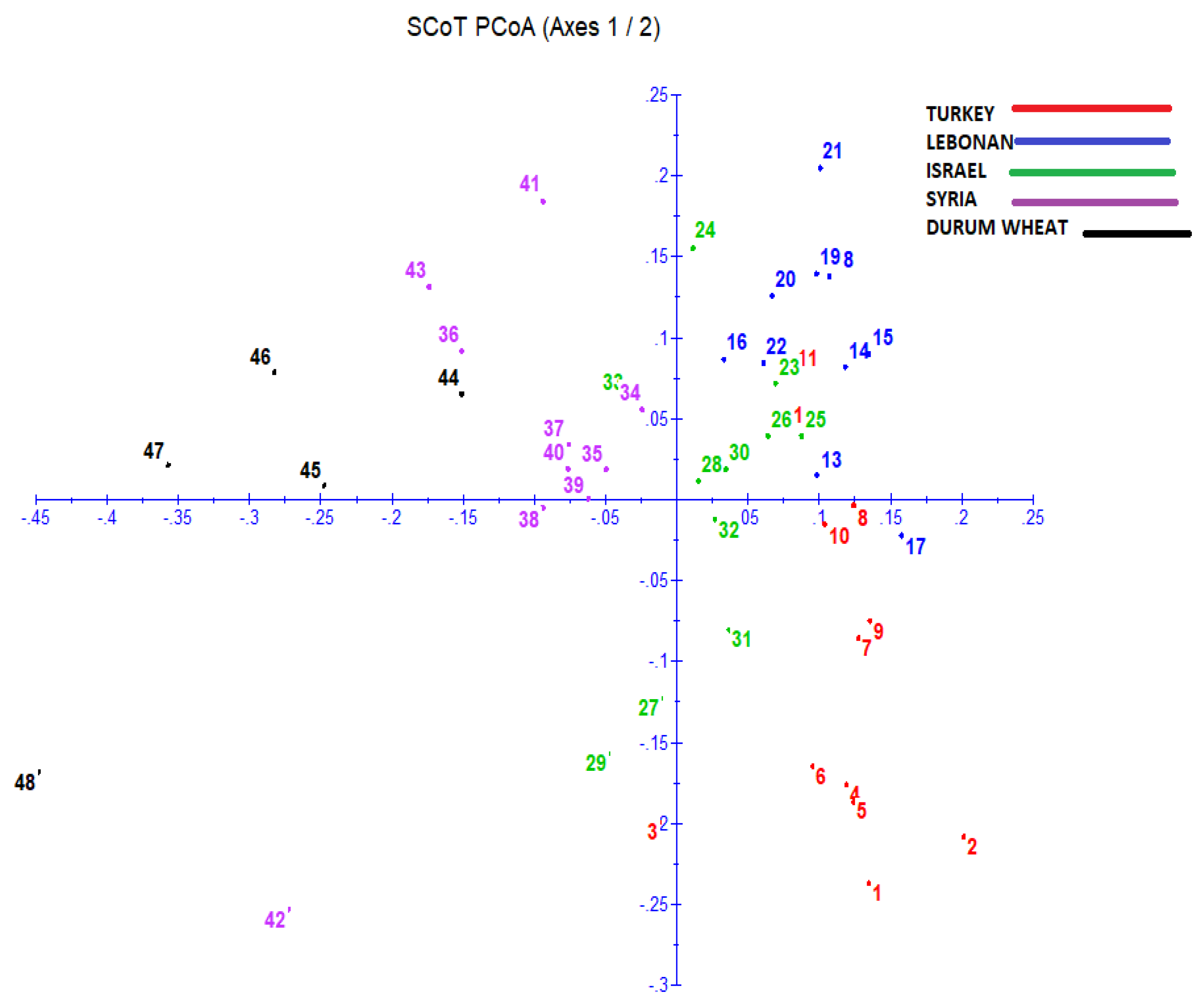

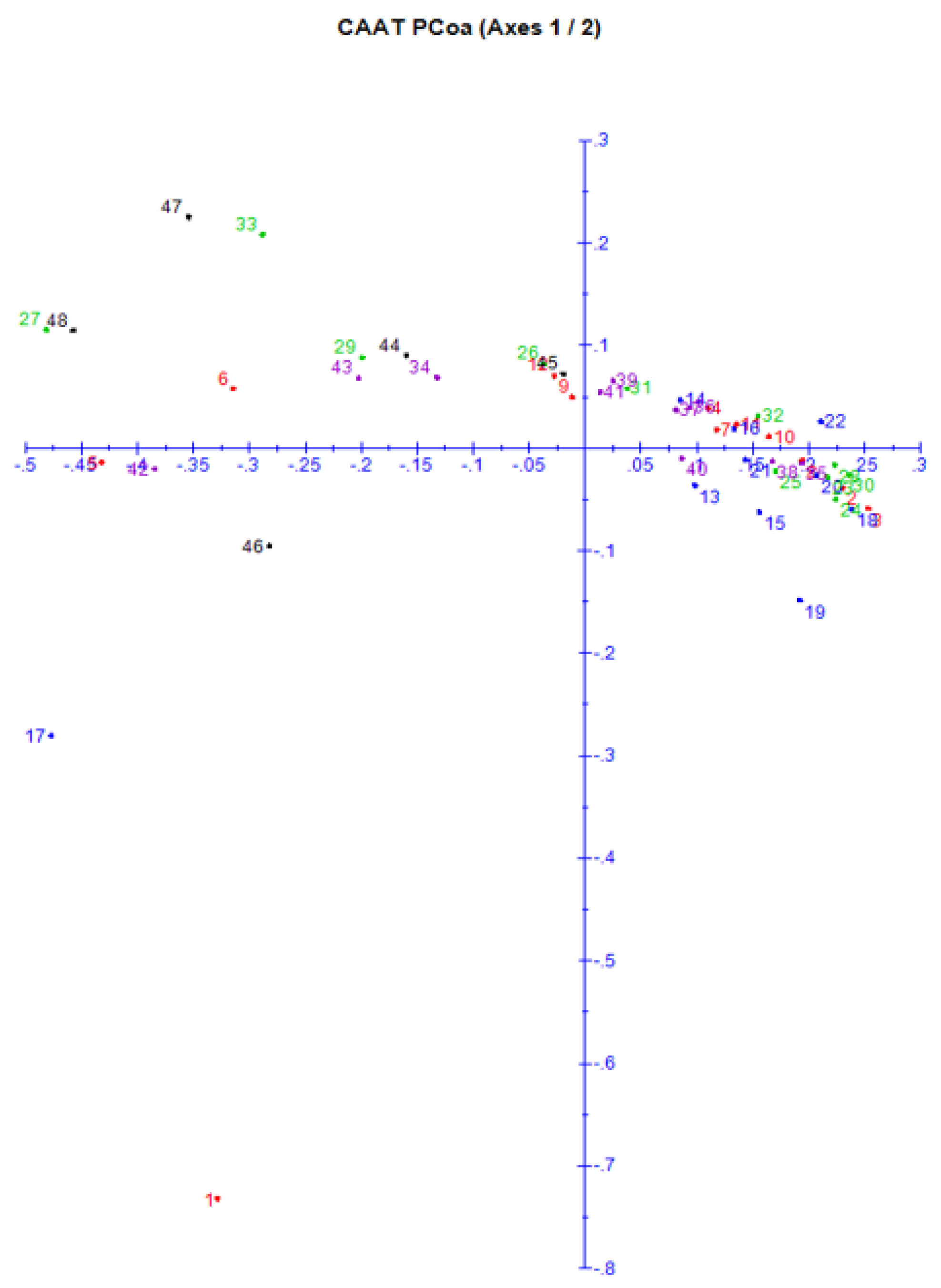

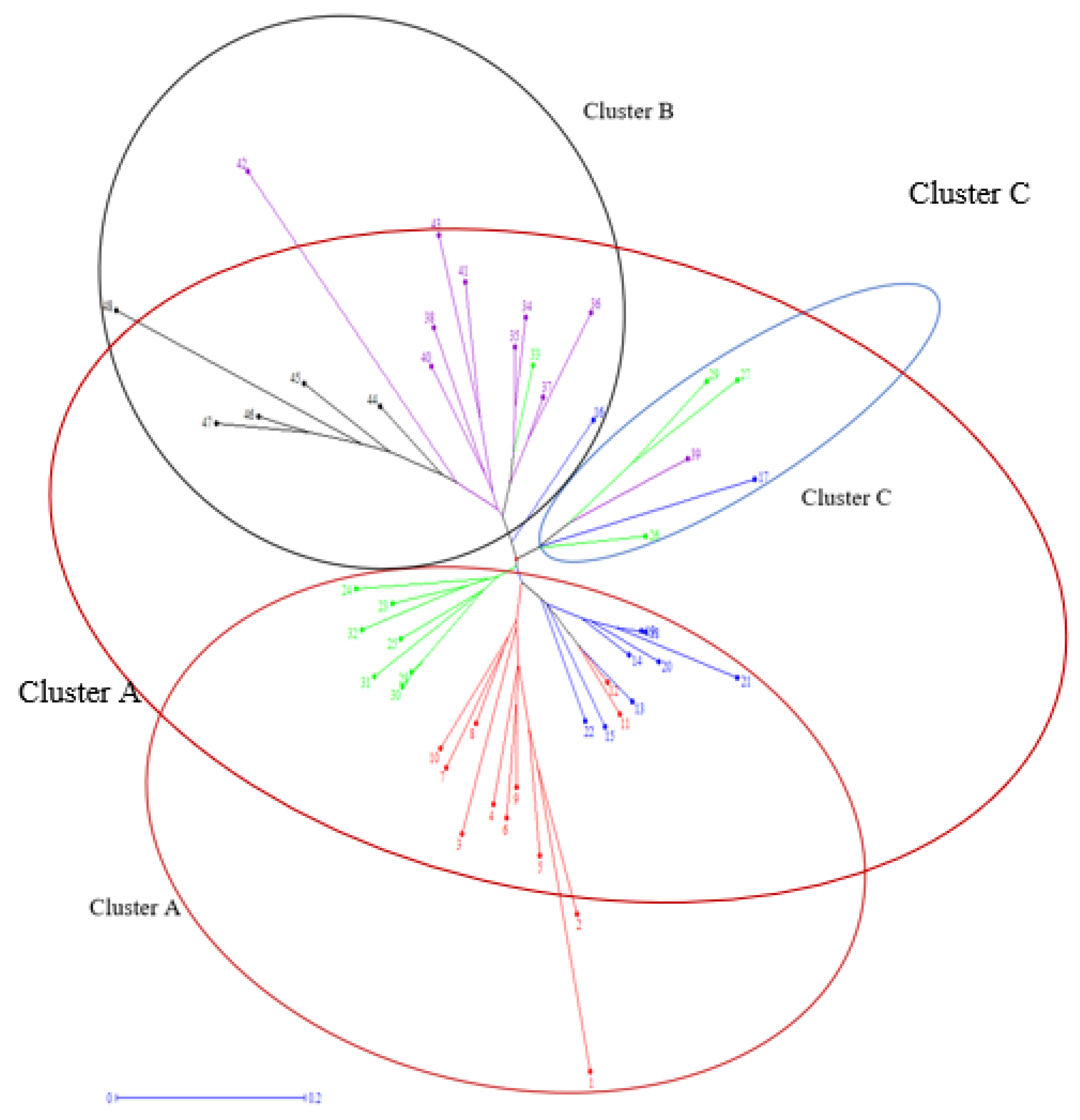

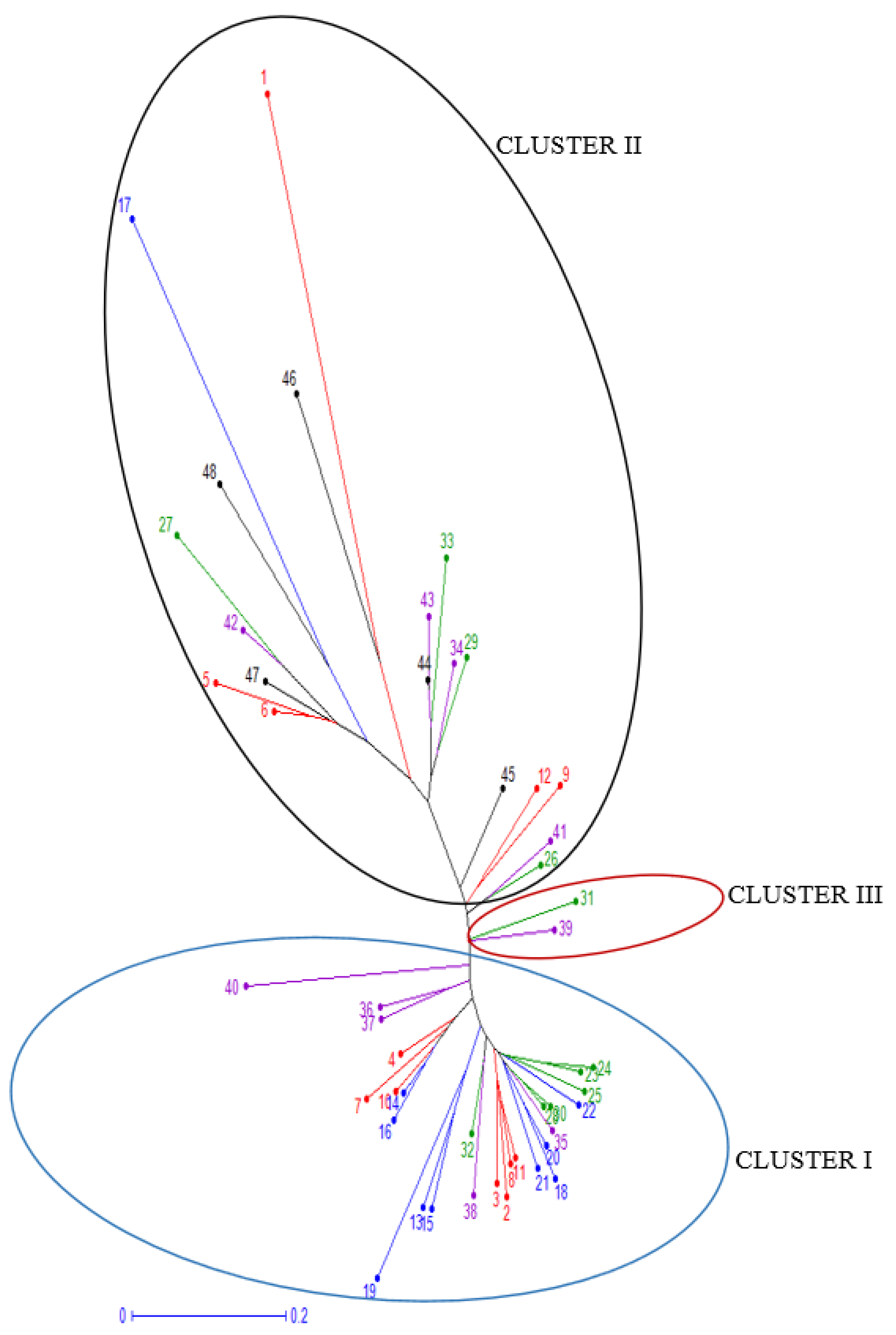

3.6. Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA)

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abouseada, H.H.; Mohamed, A.-S.H.; Teleb, S.S.; Badr, A.; Tantawy, M.E.; Ibrahim, S.D.; Ellmouni, F.Y.; Ibrahim, M. Genetic diversity analysis in wheat cultivars using SCoT and ISSR markers, chloroplast DNA barcoding and grain SEM. Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiryousefi, A.; Hyvonen, J.; Poczai, P. Irscope: An Online Program to Visualize The Junction Sites Of Chloroplast Genomes. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3030–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, J.R.; Lubberstedt, T. Functional markers in plants. TrendsPlant Sci. 2003, 8, 554–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslan-Parviz, M.; Omidi, M.; Rashidi, V.; Etminan, A.; Ahmadzadeh, A. Evaluation of genetic diversity of durum wheat (Triticum durum desf.) genotypes using inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR) and CAAT box-derived polymorphism (CBDP) markers. Genetika 2020, 52, 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, C.Y.; Collard, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; David, J.M. Start Codon Targeted (SCoT) Polymorphism: A Simple, Novel DNA Marker Technique for Generating Gene-Targeted Markers in Plants. In Plant Molecular Biology Reporter; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Collard, B.C.Y.; Jahufer, M.Z.Z.; Brouwer, J.B.; Pang, E.C.K. An introduction to markers, quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping and markerassisted selection for crop improvement: the basic concepts. Euphytica. 2005, 142, 169–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, B.C.Y.; Mackill, D.J. Conserved DNA-derived polymorphism (CDDP): a simple and novel method for generating DNA markers in plants. Plant. Mol. Biol. Report. 2009, 27, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DARwin software (Version 6).

- Dempewolf, H.; Baute, G.; Anderson, J.; Kilian, B.; Smith, C.; Guarino, L. Past and Future Use of Wild Relatives in Crop Breeding. Crop Science 2017, 57, 1070–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dice, L.R. Measures amount of ecologic association between species. Ecology 1945, 26, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.J.; Doyle, J.L. A Rapid Isolation Procedure for Small Quantities of Fresh Leaf Tissue. Phytochemical Bulletin. 1987, 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- El Haddad, N.; Kabbaj, H.; Zaïm, M.; El Hassouni, K.; Tidiane Sall, A.; Azouz, M.; Ortiz, R.; Baum, M.; Amri, A.; Gamba, F.; Bassi, F.M. Crop wild relatives in durum wheat breeding: Drift or thrift? Crop Science 2021, 61, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Haddad, N.; Sanchez-Garcia, M.; Visioni, A.; Jilal, A.; El Amil, R.; Sall, A.T.; Lagesse, W.; Kumar, S.; Bassi, F.M. Crop Wild Relatives Crosses: Multi-Location Assessment in Durum Wheat, Barley, and Lentil. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etminan, A.; Pour-Aboughadareh, A.; Mohammadi, R.; Noori, A.; Ahmadi-Rad, A. Applicability of CAAT Box-derived Polymorphism (CBDP) Markers for Analysis of Genetic Diversity in Durum Wheat. Cereal Research Communications 2018, 46, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.A.F.; Benchimol, L.L.; Barbosa, A.M.M.; Geraldi, I.O.; Souza Jr, C.L.; Souza, A.P. Comparison of RAPD, RFLP, AFLP and SSR markers for diversity studies in tropical maize inbred lines. Genetics and Molecular Biology 2004, submitted. [CrossRef]

- Gascuel, O. Concerning the NJ algorithm and its unweighted version, UNJ. In : Mathematical Hierarchies and Biology. DIMACS workshop, Series in Discrete Mathematics and Theoretical Computer Science. American Mathematical Society 1997, 37, 149–170. [Google Scholar]

- Gorji, A.M.; Poczai, P.; Polgar, Z.; Taller, J. Efficiency of arbitrarily amplified dominant markers (SCOT, ISSR and RAPD) for diagnostic fingerprinting in tetraploid potato. Am. J. Potato Res. 2011, 88, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowayed SM, H.; El-Moneim, D.A. Detection of genetic divergence among some wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes using molecular and biochemical indicators under salinity stress. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.L.; Zhang, J.Y.; Liu, C.H. Genetic diversity in some grape varieties revealed by SCoT analyses. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 5307–5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongtrakul, V.; Huestis, G.M.; Knapp, S.J. Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphisms As A Tool For DNA Fingerprinting Sunflower Germplasm, Genetic Diversity Among Oilseed İnbred Lines, Theor. Appl. Genet. 1997, 95, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, C.P.; Zhou, H.; Huang, X.; Chiang, V.L. Context sequences of translation initiation codon in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 1997, 35, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafkas, S.; Ozkan, H.; Ak BEAcar, I.; Atlı, H.S.; Koyuncu, S. Detecting DNA Polymorfism and Genetic Diversity in a Wide Pistachio Germplasm: Comparison of AFLP, ISSR and RAPD Markers. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 2006, 131, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; He, X.H.; Chen, H.; Ou, S.J.; Gao, M.P. Analysis of diversity and relationshipsamong mango cultivars using start codon targeted (SCoT) markers. Biochem. Syst.Ecol. 2010, 38, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; He, X.H.; Chen, H.; Ou, S.J.; Gao, M.P.; Brown, J.S.; Tondo, C.T.; Schnell, R.J. Genetic diversity of mango cultivars estimated using SCoT and ISSR markers. Biochem.Syst. Ecol. 2011, 39, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; He, X.H.; Chen, H.; Hu, Y.; Ou, S.J. Genetic relationship and diversity ofMangifera indica L.: revealed through SCoT analysis. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2012, 59, 1505–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour-Aboughadareh, A.; Mohmoudi, M.; Ahmadi, J.; Moghaddam, M.; Mehrabi, A.A.; Alavikia, S.S. Agro-morphological and molecular variability in Triticum boeoticum accessions from Zagros Mountains, Iran. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2017, 64, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.A.; Nawaz, M.A.; Shahid, M.Q.; Doğan, Y.; Comertpay, G.; Yıldız, M.; Hatipoğlu, R.; Ahmad, F.; Alsaleh Ahmad Labhane, N.; Özkan, H.; Chung, G.; Baloch, F.S. DNA molecular markers in plant breeding: current status and recent advancements in genomic selection and genome editing. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 2018, 32, 261–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poehlman, J.M.; Sleper, D.A. Breeding field crops. Alkek General, Floor 1995, 6, SB1857P63. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J.; Ma, C.; Jia, Y.-H.; Wang, J.-Z.; Cao, S.-K.; Li, F.F. The distribution and behavioral characteristics of plateau pikas (Ochotona curzoniae). ZooKeys 2021, 1059, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, K. M. Start codon targeted (SCoT) polymorphism marker in plant genome analysis: current status and prospects. Planta 2023, 257, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, A.; Hao, Y.; Xia, X.C.; Khan, A.; Xu, Y.; Varshney, R.K.; He, Z. Crop breeding chips and genotyping platforms: progress, challenges and perspectives. Mol Plant 2017, 10, 1047–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Chen, L.; Sun, D.; You, F.M.; Wang, J.; Peng, Y.; Nevo, E.; Beıles, A.; Sun, D.; Luo, M.-C.; Peng, J. SNP-Revealed Genetic Diversity İn Wild Emmer Wheat Correlates with Ecological Factors. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2013, 13, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawant, S.; Singh, P.; Gupta, S.; Madnala, R.; Tuli, R. Conserved nucleotide sequencesin highly expressed genes in plants. J. Genet. 1999, 78, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefc, K.M.; Lopes, M.S.; Lefort, F.; Botta, R.; Roubelakis-Angelakis, K.A.; Ibáñez, J.; Pejić, I.; et al. Microsatellite variability in grapevine cultivars from different European regions and evaluation of assignment testing to assess the geographic origins of cultivars. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2000, 100, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedimoradi, H.; Talebi, R.; Fayaz, F. Geographical diversity pattern in Iranian landrace durum wheat (Triticum turgidum) accessions using start codon targeted polymorphism and conserved DNA-derived polymorphism markers. Environmental and Experimental Biology 2016, 14, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shizuka, T.; Morı, N.; Ozkan, H.; Ohta, S. Chloroplast DNA Haplotype variation within two Natural Populations Of Wild Emmer Wheat (Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccoides) In Southern Turkey. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2015, 29, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Rana, M.K.; Singh SKumar, S.; Kumar, R.; Singh, R. CAAT box- derived polymorphism (CBDP): a novelpromoter -targeted molecular marker for plants. Journal of Plant Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2014, 23, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, W.; Guo, X.; Chen, P.; Cheng, Y.; Mao, K.; Ma, F. Cation/Ca2+ Exchanger 1 (MdCCX1), a Plasma Membrane-Localized Na+ Transporter, Enhances Plant Salt Tolerance by Inhibiting Excessive Accumulation of Na+ and Reactive Oxygen Species. Front. Plant Sci.,Sec. Plant Abiotic Stress 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, F.Q.; Zhong, R.C.; Han, Z.Q.; Jiang, J.; He, L.Q.; Zhuang, W.J.; Tang, R.H. Start Codon Targeted polymorphism for evaluation of functional genetic variation and relationships in cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) genotypes. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011, 38, 3487–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tene, M.; Adhikari, E.; Cobo, N.; Jordan, K.W.; Matny, O.; del Blanco, l.A.; Roter, J.; Ezrati, S.; Govta, L.; Manisterski, J.; Yehuda, P.B.; Chen, X.; Steffenson, B.; Akhunov, E.; Sela, H. GWAS for Stripe Rust Resistance in Wild Emmer Wheat (Triticum dicoccoides) Population: Obstacles and Solutions. Crops 2022, 2, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primer Name | Sequencing (5’-3’) |

|---|---|

| CAAT PRIMERS | |

| CAAT10 | TGAGCACGATCCAATGTT |

| CAAT12 | TGAGCACGATCCAATATA |

| CAAT13 | TGAGCACGATCCAATGAG |

| CAAT14 | TGAGCACGATCCAATGCG |

| CAAT20 | CTGAGCACGATCCAATAT |

| CAAT21 | CTGAGCACGATCCAATCA |

| CAAT22 | CTGAGCACGATCCAATCG |

| SCoT PRIMERS | |

| SCOT7 | CAACAATGGCTACCACGG |

| SCOT8 | CAACAATGGCTACCACGT |

| SCOT9 | CAACAATGGCTACCAGCA |

| SCOT10 | CAACAATGGCTACCAGCC |

| SCOT11 | AAGCAATGGCTACCACCA |

| SCOT13 | ACGACATGGCGACCATCG |

| SCOT16 | CCATGGCTACCACCGGCC |

| SCOT17 | CATGGCTACCACCGGCCC |

| SCOT19 | GCAACAATGGCTACCACC |

| SCOT23 | ACCATGGCTACCACGGGC |

| Primer Name | Scored Bands | H | PIC | E | Hav | MI | D | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAAT Primers | ||||||||

| CAAT10 | 2 | 0.435 | 0.378 | 1.361 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.539 | 1.063 |

| CAAT12 | 7 | 0.328 | 0.419 | 1.446 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.958 | 1.617 |

| CAAT13 | 12 | 0.491 | 0.352 | 5.212 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.812 | 4.638 |

| CAAT14 | 8 | 0.499 | 0.348 | 3.872 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.766 | 3.829 |

| CAAT20 | 10 | 0.378 | 0.401 | 2.531 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.936 | 3.574 |

| CAAT21 | 12 | 0.498 | 0.349 | 6.361 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.719 | 7.531 |

| CAAT22 | 12 | 0.402 | 0.392 | 3.340 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.923 | 5.914 |

| Mean | 6.3 | 0.433 | 0.377 | 3.446 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.808 | 4.024 |

| SCoT Primers | ||||||||

| SCoT7 | 9 | 0.491 | 0.370 | 3.893 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.813 | 4.340 |

| SCoT8 | 10 | 0.487 | 0.371 | 4.191 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.825 | 5.489 |

| SCoT9 | 8 | 0.440 | 0.393 | 2.617 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.894 | 3.531 |

| SCoT10 | 7 | 0.498 | 0.366 | 3.255 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.784 | 2.936 |

| SCoT11 | 6 | 0.497 | 0.367 | 2.765 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.788 | 2.127 |

| SCoT13 | 7 | 0.447 | 0.390 | 2.361 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.887 | 3.319 |

| SCoT16 | 10 | 0.483 | 0.373 | 4.085 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.834 | 2.553 |

| SCoT17 | 7 | 0.499 | 0.365 | 3.361 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.770 | 2.382 |

| SCoT19 | 5 | 0.499 | 0.365 | 2.617 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.727 | 2.595 |

| SCoT23 | 7 | 0.500 | 0.365 | 3.468 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.755 | 4.723 |

| Mean | 7.6 | 0.484 | 0.373 | 3.261 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.808 | 3.400 |

| Countries | CAAT primers | H | PIC | E | Hav | MI | D | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| caat10 | 0.497 | 0.350 | 1.083 | 0.021 | 0.022 | 0.717 | 1.166 | |

| caat12 | 0.278 | 0.435 | 1.166 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.974 | 2.000 | |

| caat13 | 0.481 | 0.358 | 4.833 | 0.003 | 0.016 | 0.839 | 4.333 | |

| caat14 | 0.500 | 0.349 | 4.083 | 0.005 | 0.021 | 0.742 | 3.500 | |

| Turkey | caat20 | 0.413 | 0.388 | 2.916 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.917 | 3.833 |

| caat21 | 0.472 | 0.362 | 7.416 | 0.003 | 0.024 | 0.620 | 6.500 | |

| caat22 | 0.353 | 0.411 | 2.750 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.949 | 5.166 | |

| mean | 0.428 | 0.379 | 3.464 | 0.006 | 0.015 | 0.823 | 3.785 | |

| caat10 | 0.397 | 0.411 | 1.454 | 0.018 | 0.026 | 0.481 | 1.090 | |

| caat12 | 0.329 | 0.435 | 1.454 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.959 | 1.818 | |

| caat13 | 0.500 | 0.364 | 5.909 | 0.004 | 0.022 | 0.759 | 3.090 | |

| caat14 | 0.499 | 0.365 | 3.818 | 0.006 | 0.022 | 0.775 | 3.090 | |

| Israel | caat20 | 0.388 | 0.414 | 2.636 | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.932 | 3.636 |

| caat21 | 0.483 | 0.373 | 7.090 | 0.004 | 0.026 | 0.653 | 6.727 | |

| caat22 | 0.471 | 0.379 | 4.545 | 0.004 | 0.016 | 0.858 | 7.636 | |

| mean | 0.438 | 0.391 | 3.844 | 0.006 | 0.018 | 0.774 | 3.870 | |

| caat10 | 0.420 | 0.402 | 1.400 | 0.021 | 0.029 | 0.521 | 1.200 | |

| caat12 | 0.368 | 0.423 | 1.700 | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.944 | 1.400 | |

| caat13 | 0.500 | 0.365 | 5.900 | 0.004 | 0.025 | 0.760 | 4.200 | |

| caat14 | 0.455 | 0.387 | 5.200 | 0.006 | 0.030 | 0.580 | 2.400 | |

| Lebanon | caat20 | 0.428 | 0.399 | 3.100 | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.906 | 4.600 |

| caat21 | 0.500 | 0.365 | 5.900 | 0.004 | 0.025 | 0.760 | 8.200 | |

| caat22 | 0.439 | 0.394 | 3.900 | 0.004 | 0.014 | 0.896 | 5.400 | |

| mean | 0.444 | 0.391 | 3.315 | 0.007 | 0.021 | 0.767 | 3.914 | |

| caat10 | 0.320 | 0.403 | 1.600 | 0.016 | 0.026 | 0.368 | 0.800 | |

| caat12 | 0.368 | 0.387 | 1.700 | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.944 | 0.600 | |

| caat13 | 0.477 | 0.341 | 4.700 | 0.004 | 0.019 | 0.849 | 3.800 | |

| caat14 | 0.480 | 0.339 | 3.200 | 0.006 | 0.019 | 0.843 | 3.600 | |

| Syria | caat20 | 0.320 | 0.403 | 2.200 | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.962 | 2.800 |

| caat21 | 0.498 | 0.331 | 5.600 | 0.004 | 0.023 | 0.784 | 4.800 | |

| caat22 | 0.391 | 0.378 | 3.200 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.931 | 4.000 | |

| mean | 0.408 | 0.369 | 3.171 | 0.006 | 0.016 | 0.811 | 2.714 | |

| caat10 | 0.500 | 0.171 | 1.000 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.778 | 0.001 | |

| caat12 | 0.202 | 0.276 | 0.800 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.990 | 1.600 | |

| caat13 | 0.391 | 0.220 | 3.200 | 0.007 | 0.021 | 0.932 | 3.600 | |

| caat14 | 0.320 | 0.245 | 1.600 | 0.008 | 0.013 | 0.964 | 2.400 | |

| Durum Wheat | caat20 | 0.147 | 0.286 | 0.800 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.995 | 1.200 |

| caat21 | 0.406 | 0.214 | 3.400 | 0.007 | 0.023 | 0.923 | 2.000 | |

| caat22 | 0.095 | 0.292 | 0.600 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.998 | 1.200 | |

| mean | 0.295 | 0.243 | 1.628 | 0.012 | 0.016 | 0.940 | 1.714 |

| Countries | Primers | H | PIC | E | Hav | MI | D | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scot7 | 0.499 | 0.360 | 4.333 | 0.005 | 0.020 | 0.771 | 2.666 | |

| Scot8 | 0.486 | 0.370 | 4.166 | 0.004 | 0.017 | 0.828 | 5.333 | |

| Scot9 | 0.413 | 0.400 | 2.333 | 0.004 | 0.010 | 0.917 | 3.000 | |

| Scot10 | 0.472 | 0.380 | 2.666 | 0.006 | 0.015 | 0.858 | 1.333 | |

| Turkey | Scot11 | 0.486 | 0.370 | 2.500 | 0.007 | 0.017 | 0.830 | 2.333 |

| Scot13 | 0.436 | 0.390 | 2.250 | 0.005 | 0.012 | 0.899 | 2.166 | |

| Scot16 | 0.413 | 0.400 | 2.916 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.917 | 3.166 | |

| Scot17 | 0.486 | 0.370 | 4.083 | 0.006 | 0.024 | 0.663 | 1.833 | |

| Scot19 | 0.486 | 0.370 | 2.916 | 0.008 | 0.024 | 0.664 | 1.500 | |

| Scot23 | 0.490 | 0.370 | 4.000 | 0.006 | 0.023 | 0.676 | 2.333 | |

| Mean | 0.467 | 0.379 | 3.216 | 0.005 | 0.017 | 0.802 | 2.566 | |

| Scot7 | 0.485 | 0.382 | 3.727 | 0.005 | 0.018 | 0.831 | 4.000 | |

| Scot8 | 0.472 | 0.388 | 3.818 | 0.004 | 0.016 | 0.856 | 4.727 | |

| Scot9 | 0.469 | 0.390 | 3.000 | 0.005 | 0.016 | 0.862 | 2.545 | |

| Scot10 | 0.490 | 0.380 | 4.000 | 0.006 | 0.025 | 0.677 | 2.545 | |

| Israel | Scot11 | 0.498 | 0.376 | 2.818 | 0.008 | 0.021 | 0.783 | 1.636 |

| Scot13 | 0.499 | 0.375 | 3.636 | 0.006 | 0.024 | 0.733 | 2.545 | |

| Scot16 | 0.499 | 0.375 | 5.272 | 0.005 | 0.024 | 0.724 | 3.272 | |

| Scot17 | 0.499 | 0.375 | 3.363 | 0.006 | 0.022 | 0.772 | 2.727 | |

| Scot19 | 0.452 | 0.397 | 3.272 | 0.008 | 0.027 | 0.576 | 2.000 | |

| Scot23 | 0.481 | 0.384 | 4.181 | 0.006 | 0.026 | 0.646 | 2.727 | |

| Mean | 0.484 | 0.382 | 3.709 | 0.006 | 0.022 | 0.746 | 2.872 | |

| Scot7 | 0.500 | 0.375 | 4.600 | 0.006 | 0.026 | 0.742 | 3.200 | |

| Scot8 | 0.476 | 0.386 | 6.100 | 0.005 | 0.029 | 0.630 | 4.200 | |

| Scot9 | 0.480 | 0.384 | 3.200 | 0.006 | 0.019 | 0.843 | 3.200 | |

| Scot10 | 0.474 | 0.387 | 2.700 | 0.007 | 0.018 | 0.855 | 1.000 | |

| Scot11 | 0.499 | 0.375 | 2.900 | 0.008 | 0.024 | 0.771 | 1.400 | |

| Lebanon | Scot13 | 0.420 | 0.411 | 2.100 | 0.006 | 0.013 | 0.913 | 2.600 |

| Scot16 | 0.484 | 0.383 | 4.100 | 0.005 | 0.020 | 0.834 | 2.200 | |

| Scot17 | 0.474 | 0.387 | 4.300 | 0.007 | 0.029 | 0.626 | 1.000 | |

| Scot19 | 0.497 | 0.376 | 2.700 | 0.010 | 0.027 | 0.713 | 2.200 | |

| Scot23 | 0.474 | 0.387 | 4.300 | 0.007 | 0.029 | 0.626 | 2.200 | |

| Mean | 0.478 | 0.385 | 3.700 | 0.007 | 0.023 | 0.755 | 2.320 | |

| Scot7 | 0.470 | 0.356 | 3.400 | 0.005 | 0.018 | 0.860 | 2.400 | |

| Scot8 | 0.412 | 0.382 | 2.900 | 0.004 | 0.012 | 0.918 | 3.800 | |

| Scot9 | 0.439 | 0.370 | 2.600 | 0.005 | 0.014 | 0.897 | 3.200 | |

| Scot10 | 0.500 | 0.342 | 3.400 | 0.007 | 0.024 | 0.768 | 3.200 | |

| Syria | Scot11 | 0.498 | 0.343 | 3.200 | 0.008 | 0.027 | 0.720 | 2.400 |

| Scot13 | 0.420 | 0.379 | 2.100 | 0.006 | 0.013 | 0.913 | 2.200 | |

| Scot16 | 0.480 | 0.352 | 4.000 | 0.005 | 0.019 | 0.842 | 1.600 | |

| Scot17 | 0.485 | 0.349 | 2.900 | 0.007 | 0.020 | 0.832 | 1.000 | |

| Scot19 | 0.487 | 0.348 | 2.100 | 0.010 | 0.020 | 0.829 | 2.600 | |

| Scot23 | 0.353 | 0.405 | 1.600 | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.950 | 2.400 | |

| Mean | 0.454 | 0.363 | 2.820 | 0.006 | 0.018 | 0.853 | 2.480 | |

| Scot7 | 0.411 | 0.316 | 2.600 | 0.009 | 0.024 | 0.921 | 2.800 | |

| Scot8 | 0.471 | 0.289 | 3.800 | 0.009 | 0.036 | 0.860 | 2.000 | |

| Scot9 | 0.180 | 0.384 | 0.800 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.992 | 1.600 | |

| Scot10 | 0.496 | 0.277 | 3.800 | 0.014 | 0.054 | 0.713 | 0.400 | |

| Durum Wheat | Scot11 | 0.391 | 0.323 | 1.600 | 0.013 | 0.021 | 0.936 | 1.200 |

| Scot13 | 0.202 | 0.379 | 0.800 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.990 | 0.400 | |

| Scot16 | 0.461 | 0.294 | 3.600 | 0.009 | 0.033 | 0.875 | 2.000 | |

| Scot17 | 0.202 | 0.379 | 0.800 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.990 | 1.600 | |

| Scot19 | 0.365 | 0.333 | 1.200 | 0.015 | 0.018 | 0.950 | 1.200 | |

| Scot23 | 0.408 | 0.317 | 2.000 | 0.012 | 0.023 | 0.924 | 2.000 | |

| Mean | 0.359 | 0.329 | 1.860 | 0.010 | 0.022 | 0.915 | 1.440 |

| H | PIC | E | Hav | MI | D | R | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAAT PRIMERS | ||||||||

| Turkey | 0.428 | 0.379 | 3.464 | 0.006 | 0.015 | 0.823 | 3.785 | |

| Israel | 0.438 | 0.391 | 3.844 | 0.006 | 0.018 | 0.774 | 3.870 | |

| Lebanon | 0.444 | 0.391 | 3.315 | 0.007 | 0.021 | 0.767 | 3.914 | |

| Syria | 0.408 | 0.369 | 3.171 | 0.006 | 0.016 | 0.811 | 2.714 | |

| Durum Wheat | 0.295 | 0.243 | 1.628 | 0.012 | 0.016 | 0.940 | 1.714 | |

| SCoT PRIMERS | ||||||||

| Turkey | 0.467 | 0.379 | 3.216 | 0.005 | 0.017 | 0.802 | 2.566 | |

| Israel | 0.484 | 0.382 | 3.709 | 0.006 | 0.022 | 0.746 | 2.872 | |

| Lebanon | 0.478 | 0.385 | 3.700 | 0.007 | 0.023 | 0.755 | 2.320 | |

| Syria | 0.454 | 0.363 | 2.820 | 0.006 | 0.018 | 0.853 | 2.480 | |

| Durum Wheat | 0.359 | 0.329 | 2.100 | 0.010 | 0.022 | 0.915 | 1.440 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).