1. Introduction

Microfluidic systems enable precise control and manipulation of droplets and flow on a microscale [

1,

2], facilitating separation and movement through finely tuned liquid flow [

3]. By integrating principles from micro-mechanics, fluid dynamics, and smart materials, these systems stand out for their compact design and precise fluid handling capabilities [

4,

5]. Applications span from lab-on-a-chip technologies and microbiology to cooling systems in high-performance electronics and targeted drug delivery. Micropumps are essential for fluid delivery in microfluidics [

6,

7], supporting diverse uses, such as biological fluid transport and cooling in miniaturized electronic devices. In these systems, ultrasonic waves are frequently employed to drive liquids through microchannels [

8,

9]. This ultrasound-based technique focuses energy efficiently, providing a substantial driving force that enables precise fluid control without physical contact, thus allowing for controlled output, absorption, and mixing of fluids. Accordingly [

10,

11], ultrasound-driven microfluidics have been extensively employed in various applications in the microfluidic field.

2. Working Principle of Valveless Micropumps

This article investigates the mechanism of valveless micropumps, which are effective at low Reynolds numbers for overcoming fluid dynamic resistance. Valveless pumps are particularly advantageous in reducing the risk of blockage and preserving the integrity of biological materials [

12,

13,

14], making them ideal components in microfluidic applications. These pumps facilitate fluid movement, while reciprocating micropumps, paired with two one-way microvalves, are used to regulate the flow direction [

15,

16].

2.1. Working Principle and Features of Valveless Micropumps

Valveless micropumps regulate fluid outflow using diffusion and contraction tubes, which create varying fluid dynamics due to differences in their capacities and structures. These variations produce distinct inflow and outflow rates, resulting in differential fluid flow [

17,

18]. The pumps operate by employing moving components to induce periodic vibrations. Each cycle consists of two modes: "suction" and "pumping". During the suction mode, the pump chamber expands upward under external force, increasing its volume and lowering internal pressure relative to the outside. At this stage, the inlet acts as a diffusion outlet [

19,

20], and the outlet functions as a contraction tube, causing the fluid flow rate in the diffusion tube to exceed that in the contraction tube, thereby enhancing the inflow. In the pumping mode [

21,

22], the chamber contracts downward, reducing its volume and raising the internal pressure. At this point, the inlet functions like a contraction tube, and the outlet behaves as a diffusion tube, allowing fluid to exit the chamber and complete the transport process.

The pump chamber contains oscillating diaphragms on either side, which adjust the chamber volume to draw in and expel fluid [

23,

24,

25]. Through their oscillation, these diaphragms modulate the chamber volume, effectively forming a one-way valve with the combined action of the diffusion and contraction tubes. This valveless micropump design, utilizing diffusion and contraction tubes, unifies the driving source, transmission part [

26,

27], and pump body traditionally found as separate elements in conventional pumps. However, moving components may incur losses from pressure and are susceptible to wear, fatigue damage, and specific challenges when handling certain fluids [

28,

29]. At the microscale, advancements in driving technology for valveless micropumps continue to address these evolving demands.

2.2. Applications for Valveless Micropumps

Valveless micropumps are highly effective at operating under high frequencies, making them indispensable for transporting liquids with suspended particles or biological materials. These pumps hold considerable promise for applications in chemistry [

30], pharmaceuticals, and biomedicine. In microfluidic channels, slight disruptions from rough wall surfaces can influence fluid dynamics within the system, leading to vortex structures in the near-wall regions of the flow fields. The fluid flow typically remains in a laminar state, where internal friction shear stress following Newton’s law of internal friction. Key parameters of the microfluidic system such as velocity distribution [

31], flow rates, and energy losses during laminar flow can be determined using mathematical methods.

3. Oscillatory Fluid Motion

In this study, the “Fluid-Solid Coupling” interface within COMSOL is employed to analyze fluid flow and the resulting deformations within valve structures. The “Global Ordinary Differential and Differential Algebraic Equations” module facilitates time-based numerical calculations, tracking fluid flow throughout each phase of the pumping cycle across the microfluidic system. The reciprocating pumping mechanism induces oscillatory fluid motion, transforming this oscillation into a directed net flow. Within the system, the oscillatory pumping action is achieved through a piezo-oscillator that vibrates the membrane, periodically adjusting the volume of the microchamber.

3.1. Microscale Model Geometry

The model geometry described in this paper comprises a horizontal channel and a vertical chamber. The horizontal channel spans 1000 micrometers in length and 100 micrometers in height, with a vertically oriented chamber connected at its midpoint. Within the channel, two angled valve flaps are centrally positioned, creating a narrow, upright structure. These valve flaps, influenced by oscillatory fluid motion, generate a net fluid flow from left to right through the channel. As fluid moves from left to right, it enters the narrow section in the upper half of the channel after passing through the valve flaps. This fluid movement applies viscous resistance and pressure against the internal channel structures, resulting in a net force on both sides of the internal configuration. Made from a flexible material, the valve flaps deform under external forces, changing the direction of fluid flow. The numerical results of fluid flow need to be calculated based on known conditions.

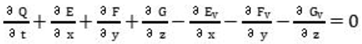

In the model, the flow variables (density, velocity components, pressure) can be represented using the following equation:

Where Γ is a diagonal matrix, Q is a vector, and the terms Ev, Fv, and Gv represent the viscous flux.

At the bottom of the channel, two angled valve flaps partially obstruct the fluid flow along the channel’s length. These valve flaps are separated by a specific distance, with the midpoint of the space between them aligned with the midpoint of the channel. Positioned at a 60-degree angle from the horizontal plane, each flap measures 6 micrometers in width and 56 micrometers in height, featuring a semicircular top edge. They are located 200 micrometers and 700 micrometers from the left boundary of the channel, respectively. The fluid within the channel is modeled as a water-like substance, with a density of 1000 kg/m3 and a dynamic viscosity of 0.001 Pa·s.

3.2. Flow Process Analysis

The numerical simulations in this study are conducted using the “Fluid-Solid Coupling” multiphysics interface. The inlet boundary is positioned above the vertical chamber, where the inlet flow velocity is input with a sinusoidal variation with a period of 2 seconds. The left and right boundaries of the channel act as the outlet boundaries. At each outlet, the flow rate is calculated by integrating the horizontal fluid velocity component (the dependent variable) and then multiplying it by a surface length scale of 10 micrometers. This approach allows for determining the flow rate difference between the left and right outlets, with a positive net flow value indicating a left-to-right movement. By analyzing this data, the study calculates the net flow variation over time, ultimately providing the total volume flow of the pump in one cycle. This analysis specifically examines the transient dynamics throughout a cycle, with a focus on the two complete oscillations of the inlet velocity.

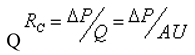

According to Poiseuille's law, the flow resistance of a fluid channel in a laminar state is the ratio of pressure drop

ΔP to volumetric flow rate

Q. This can be mathematically expressed in the form below:

Abrupt changes in flow can arise due to the deformation of the valve flap and the corresponding fluid feedback. To manage this, the solver employs larger time steps when the solution remains relatively stable. In the fluid-solid coupling model, sudden changes in fluid flow may occur, so setting a maximum time step aids in accurately capturing these rapid variations.

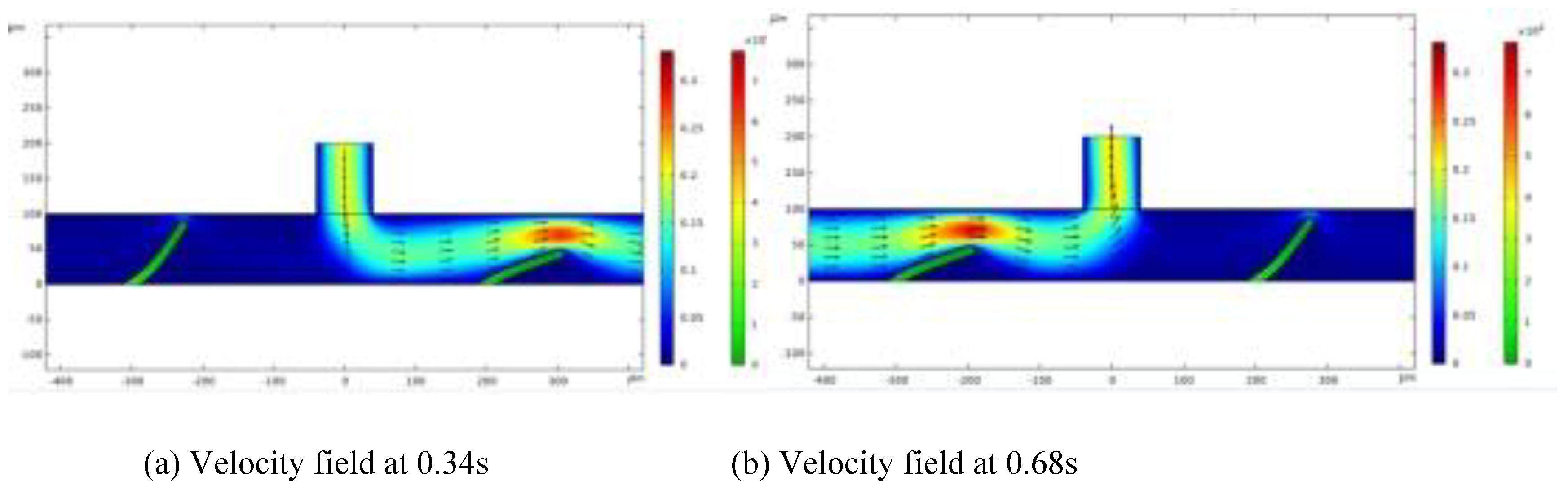

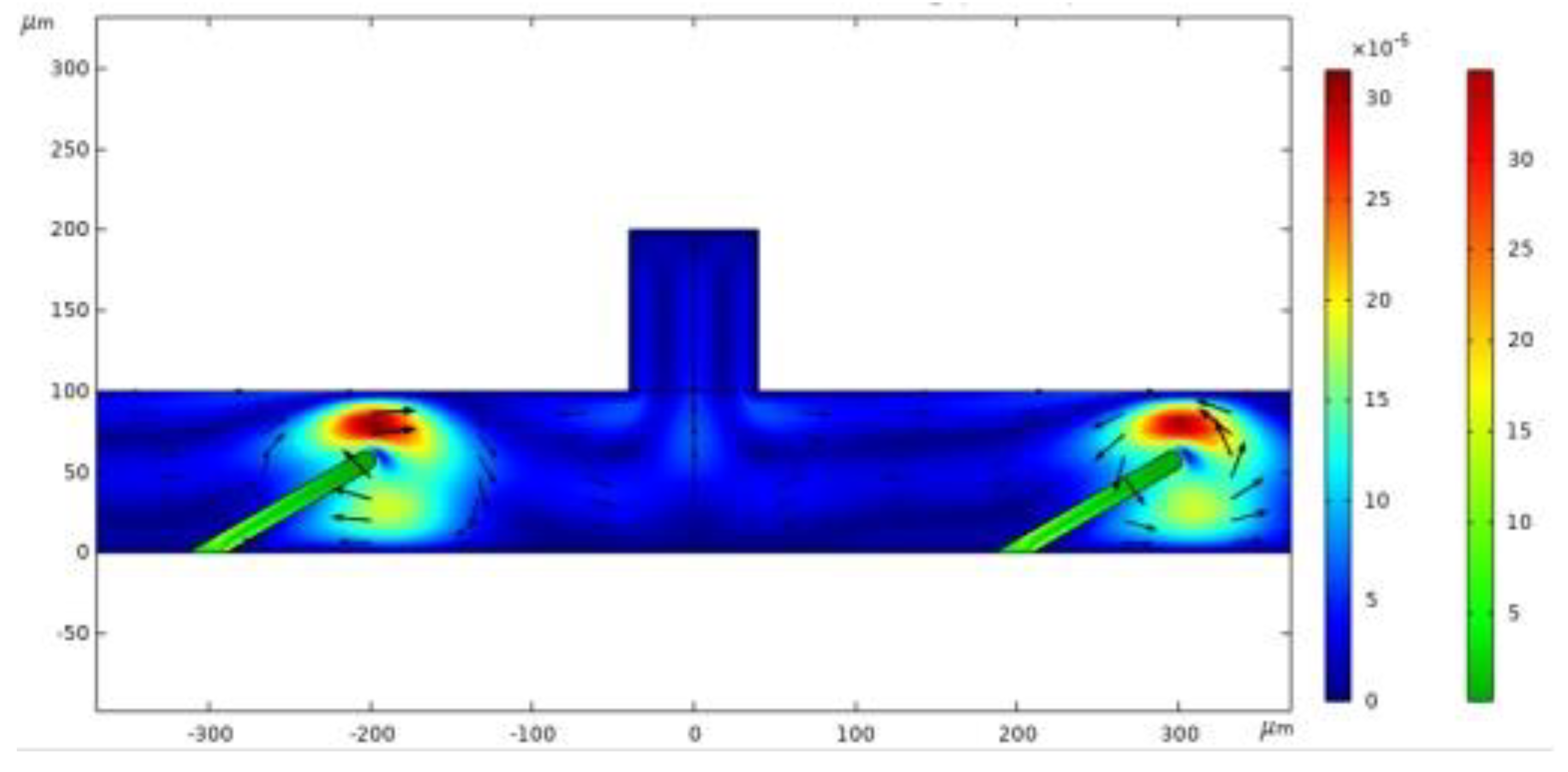

Figure 1 illustrates changes in flow velocity at four distinct time points: t = 0.34s, 0.68s, 1.28s, and 1.68s. The streamlines show the fluid flow positions, with a color gradient from blue to red, indicating an increase in flow velocity from lower to higher levels. As fluid moves through the channel, the valve flap boundary shifts vertically and horizontally, with the highest fluid velocity occurring near the flap. The degree of flap deformation correlates with the inflow velocity; as the flow rate reduces, the force exerted by the fluid weakens, resulting in less deformation. The fluid enters from the left side along the horizontal channel and passes through the constricted area above the flap, which bends under the influence of fluid pressure and viscous resistance. This study explores variations of flow patterns in response to the bending and deformation of the flap.

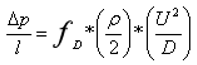

Where

ΔP is the pressure drop,

l represents the length,

ρ is the fluid density,

U is the average fluid velocity, and

D denotes the hydraulic diameter of the fluid channel,

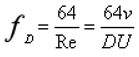

fD is the Darcy friction factor. In the laminar state, this factor is defined as follows:

Where Re is the Reynolds number, and ν denotes the dynamic viscosity.

As fluid enters through the inlet along the horizontal channel, both valve flaps simultaneously bend toward the channel's bottom. However, their bending amplitudes differ, creating a condition that allows fluid to flow more readily toward the right outlet.

3.3. Analysis of Flow Process at Different Positions of the Valve Flaps

As the fluid flows upward, it moves from the horizontal channel into the vertical chamber, causing the two valve flaps to bend outward in opposite directions. During this upward movement, fluid flows from the channel toward the inlet, with each valve flap bending differently. The right valve flap, having a greater bending amplitude, restricts flow more effectively than the left valve flap, allowing fluid from the left to enter the vertical chamber and move from left to right.

In calculating the net flow rate within the channel, left-to-right flow is assigned a positive value, while right-to-left flow is assigned a negative value.

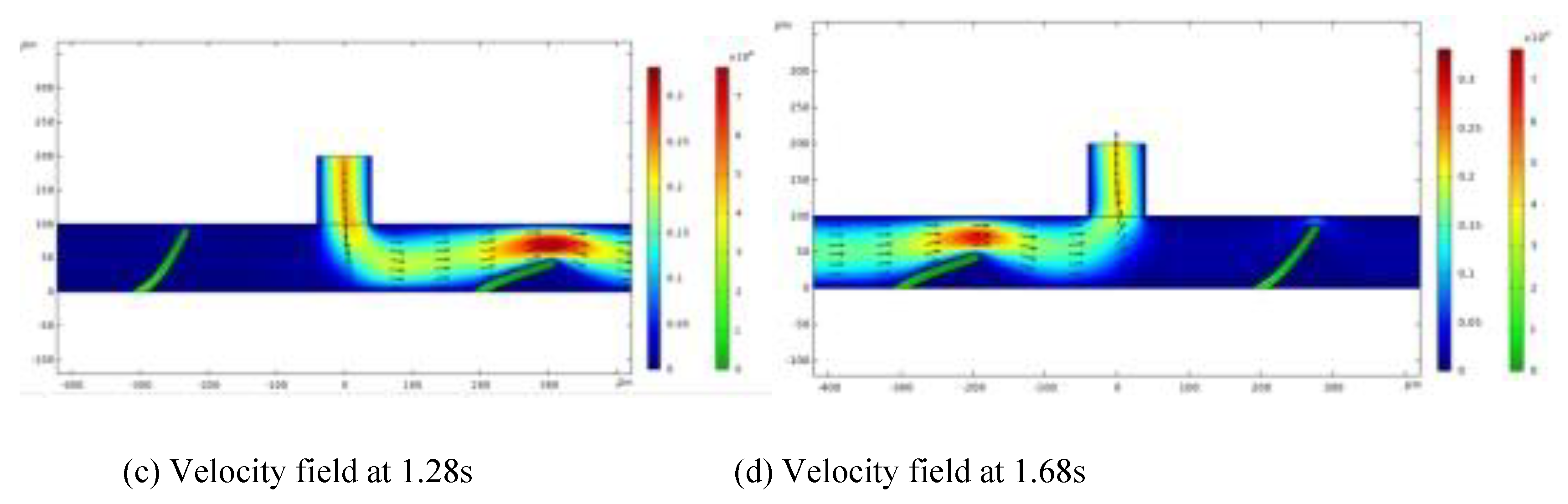

Figure 2 illustrates the fluid flow velocity and velocity field at two specific moments: 0.105 seconds and 0.4 seconds. Streamlines indicate the flow direction, while color variations represent different flow velocities. As fluid moves, the valve flaps act as dynamic boundaries, where fluid velocity peaks near the flaps, causing the greatest variation in fluid behavior. Flow velocity impacts fluid deformation; as flow velocity declines, deformation decreases. By the end of a cycle, the inflow and structural deformation settle into steady-state values, and flow velocity reduces to zero.

On the microscale, viscous forces increase, limiting flow velocity and preventing the attainment of a high Reynolds number. This limitation can be addressed by introducing high-frequency sound waves. Acoustic radiation enters the microfluid, generating acoustic streaming that creates a driving force within the fluid. When this driving force surpasses the microfluid's surface tension, the fluid moves in the direction of the sound waves.

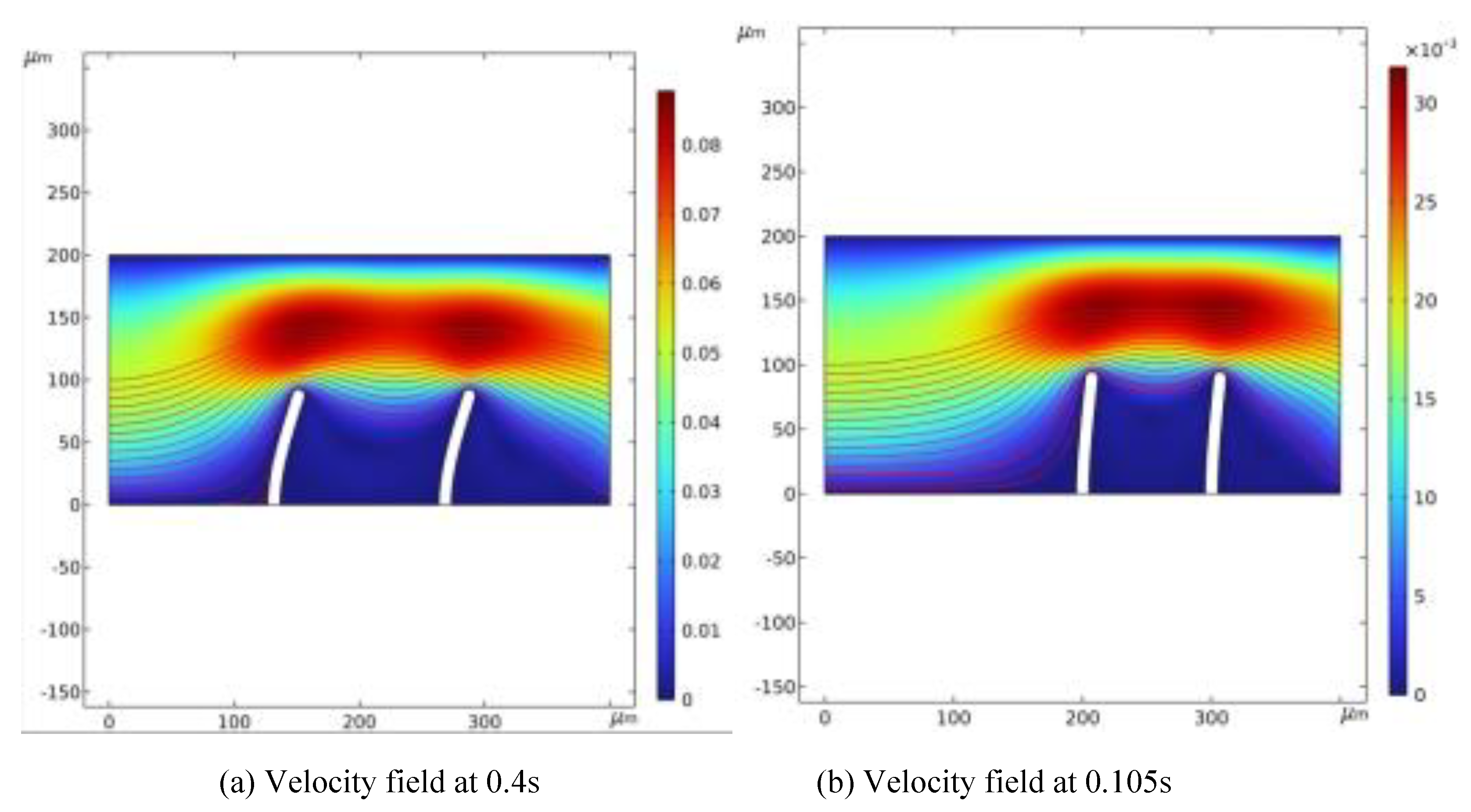

Figure 3 illustrates At time t = 0.15 s, comparing the grid velocity and valve flap deformation at various positions reveals the direction and changes in the velocity field post-deformation, with clear horizontal variations in fluid movement. On the left side of the valve flap, grid elements are stretched, resulting in an unclear velocity field. Conversely, on the right side, the grid elements compress horizontally, forming a distinct fluid velocity field and demonstrating significant velocity changes as fluid flows past the valve flaps. The positioning of the valve flaps notably influences the velocity field's variation; flaps placed further to the left lead to greater fluctuations in the fluid velocity field.

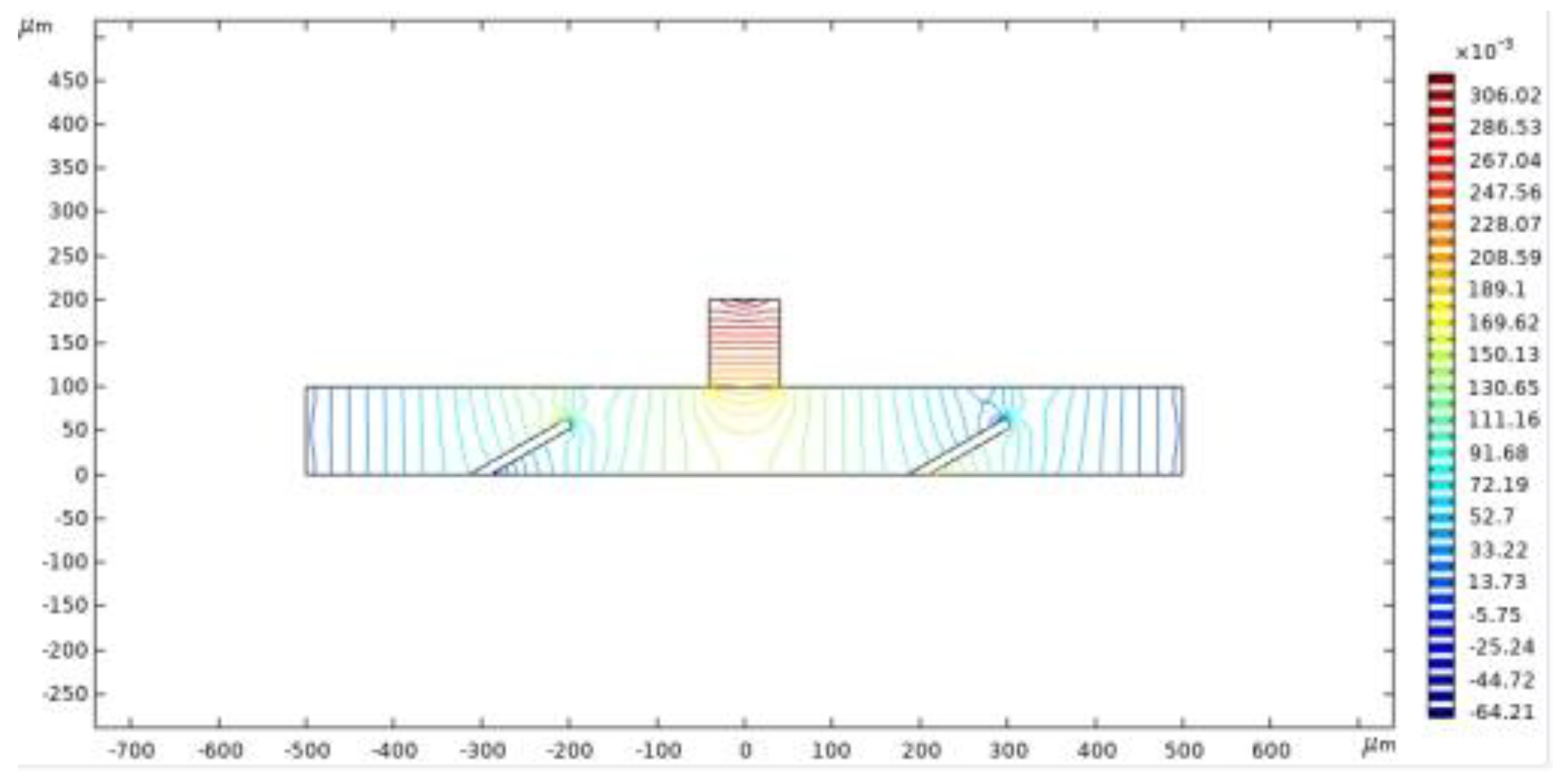

Figure 4 displays the stress distribution in the system at t = 2 s, as the system nears its steady state. The seepage stress streamlines form a radial pattern, with peak stress values appearing at the top of the valve flap and gradually diminishing downward, followed by a slight increase near the bottom. This shows that stress levels are significantly higher around the valve flap than in other regions. Throughout fluid seepage, the flow direction continually changes, with the fluid moving from areas of high to low pressure. In accordance with Darcy's law, the flow velocity is directly proportional to the pressure gradient, meaning that as the pressure drop rises, so does the flow velocity.

The fluid maintains a laminar state due to the small size of the channel and the low Reynolds number. Vortices develop in the confined area behind the valve flap, with their size and location dictated by the flow velocity, while the degree of deformation is influenced by the inflow velocity. There is a net fluid flow from left to right, although this flow is obstructed by the valve flap.

Pressure variations exhibit both oscillating and stationary states at identical pressure levels, transitioning from low to high and back to low. During periods of high pressure, a lag phenomenon is observed. Under dynamic conditions, the liquid collides with the surfaces of the valve flaps, transforming kinetic energy into elastic potential energy during the impact, alongside associated energy losses.

Figure 5 presents the pressure contour of fluid flow at t = 2 s. The streamlines illustrate the variation in flow pressure, while the color gradient indicates the magnitude of the flow pressure. The highest flow pressure is observed along the central vertical axis, gradually decreasing as it extends downward. Near the outlet, positioned outside the valve flap, the flow pressure shows a gradual decrease followed by an increase in the opposite direction.

4. Conclusions

Modern science has evolved to encompass research across a range of scales, including macroscopic, microscopic, and nanoscale dimensions, along with multiple temporal and spatial variables. The advancement of multiscale research significantly benefits everyday life. Computer simulations have gained immense importance in scientific investigations, particularly within the medical field encompassing areas such as physiology, pathophysiology, and surgical treatment. This paper explores the application of computational fluid dynamics in microfluidic systems and examines the influence of obstacles, such as valve flaps, on fluid flow at the microscale. The study reveals that when oscillatory flow is injected into channels with flexible valve flaps, the flaps deform in response to fluid impact, consequently altering the flow direction. Utilizing a "Fluid-Solid Coupling" multiphysics interface, the research delves into the fluid dynamics characteristics of both the fluid and the valve flaps, analyzing the deformation of the valve flaps and the temporal variations in fluid flow within the pumping mechanism model. The investigation considers different configurations regarding the positions and quantities of the valve flaps, calculating the variations in net volume pumped from left to right over time. This analysis provides valuable insights for microfluidic applications in microscale scenarios.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2019PA010). Corresponding author: Meng Weiyun.

References

- Hardt S, Pen nemann H, Schönfeld F (2006) Theoretical and experimental characterization of a low-reynolds number split-and-recombine mixer. Microfluidics and Nanofluidics 2(3):237–248. [CrossRef]

- Di Tommaso P, Chatzou M, Floden EW, Barja PP, Palumbo E, Notredame C. Nextflow enables repro ducible computational workflows. Nat Biotechnol. 2017; 35: 316–319. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au AK, Bhattacharjee N, Horowitz LF, Chang TC, Folch A. 3D-printed microfluidic automation. Lab Chip. 2015; 15: 1934–41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonyar A, Santha H, Varga M, Ring B, Harsanyi G. Characterization of rapid PDMS casting technique utilizing molding forms fabricated by 3D rapid prototyping technology (RPT). Int J Mater Form. 2014; 7: 189–196. [CrossRef]

- Tan YC, Cristini V, Lee AP. Monodispersed microfluidic droplet generation by shear focusing microfluidic device. Sensors Actuators, B Chem. 2006; 114: 350–356. [CrossRef]

- Ho CMB, Ng SH, Li KHH, Yoon Y. 3D printed microfluidics for biological applications. Lab Chip. 2015; 15: 3627–3637. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagally ET, Emrich CA, Mathies RA. Fully integrated PCR-capillary electrophoresis microsystem for DNA analysis. Lab on a Chip. 2001; 1(2):102. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu J, Cao W, Wen W, Chang DC, Sheng P. Polydimethylsiloxane microfluidic chip with integrated microheater and thermal sensor. Biomicrofluidics. 2009; 3(1):012005. [CrossRef]

- Cero´n EN, Ortgies DH, del Rosal B, Ren F, Benayas A, Vetrone F, et al. Hybrid Nanostructures for High-Sensitivity Luminescence Nanothermometry in the Second Biological Window. Advanced Materials. 2015; 27(32):4781–4787. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park S, Wijethunga PAL, Moon H, Han B (2011) On-chip characterization of cryoprotective agent mixtures using an EWOD-based digital microfluidic device. Lab Chip 11: 2212–2221. [CrossRef]

- Swain JE, Lai D, Takayama S, Smith GD (2013) Thinking big by thinking small: application of microfluidic technology to improve ART. Lab Chip 13: 1213– 1224. [CrossRef]

- Newton H, Pegg DE, Barrass R, Gosden RG (1999) Osmotically inactive volume, hydraulic conductivity, and permeability to dimethyl sulphoxide of human mature oocytes. J Reprod Fertil 117: 27–33. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan V, Pamula VK, Fair RB (2004) An integrated digital microfluidic lab on-a-chip for clinical diagnostics on human physiological fluids. Lab Chip 4: 310–315. [CrossRef]

- Gaver Iii DP, Kute SM (1998) A Theoretical Model Study of the Influence of Fluid Stresses on a Cell Adhering to a Microchannel Wall. Biophysical Journal 75: 721–733. [CrossRef]

- Cooley M, Sarode A, Hoore M, Fedosov DA, Mitragotri S, Sen Gupta A. Influence of particle size and shape on their margination and wall-adhesion: implications in drug delivery vehicle design across nanoto-micro scale. Nanoscale. 2018; 10(32):15350–15364. Epub 2018/08/07. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucullo L, Hossain M, Puvenna V, Marchi N, Janigro D. The role of shear stress in Blood-Brain Barrier endothelial physiology. BMC Neurosci. 2011; 12:40. Epub 2011/05/17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang Z, Antonetti DA, Tarbell JM. Shear stress regulates HUVEC hydraulic conductivity by occludin phosphorylation. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005; 33(11):1536–1545. Epub 2005/12/13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morigi M, Zoja C, Figliuzzi M, Foppolo M, Micheletti G, Bontempelli M, et al. Fluid shear stress modulates surface expression of adhesion molecules by endothelial cells. Blood. 1995; 85(7):1696–1703. Epub 1995/04/01. [PubMed]

- Terrell-Hall TB, Ammer AG, Griffith JI, Lockman PR. Permeability across a novel microfluidic blood tumor barrier model. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2017; 14(1):3. Epub 2017/01/25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boedicker JQ, Vincent ME, Ismagilov RF (2009) Microfluidic Confinement of Single Cells of Bacteria in Small Volumes Initiates High-Density Behavior of Quorum Sensing and Growth and Reveals Its Variability. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 48: 5908–5911. [CrossRef]

- Chin CD, Linder V, Sia SK. Commercialization of microfluidic point-of-care diagnostic devices. Lab Chip. 2012; 12(12):2118–34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields CW, Ohiri KA, Szott LM, Lo´pez GP. Translating microfluidics: Cell separation technologies and their barriers to commercialization. Cytom Part B—Clin Cytom. 2017; 92(2):115–25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdonald NP, Cabot JM, Smejkal P, Guijt RM, Paull B, Breadmore MC. Comparing Microfluidic Performance of Three-Dimensional (3D) Printing Platforms. Anal Chem. 2017; 89(7):3858–66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bragheri F, Martinez Vazquez R, Osellame R. Microfluidics. Three-Dimensional Microfabrication Using Two-Photon Polymerization: Fundamentals, Technology, and Applications. 2016. 310–334 p.

- Brzeziński M., Socka M., Makowski T., Kost B., Cieślak M., and Kro´lewska-Golińska K., “Microfluidic assisted nanoprecipitation of biodegradable nanoparticles composed of PTMC/PCL (co)polymers, tannic acid and doxorubicin for cancer treatment,” Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces, vol. 201, p. 111598, May 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karnik R., Gu F., Basto P., Cannizzaro C., Dean L., Manu W. K. et al., “Microfluidic Platform for Controlled Synthesis of Polymeric Nanoparticles,” Nano Lett., vol. 8, no. 9, pp. 2906–2912, Sep. 2008. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimmerling RJ, Lee Szeto G, Li JW, Genshaft AS, Kazer SW, Payer KR, et al. A microfluidic platform enabling single-cell RNA-seq of multigenerational lineages. Nat Commun. 2016; 7: 10220. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser M, Jug F, Julou T, Deshpande S, Pfohl T, Silander OK, et al. Monitoring single-cell gene regulation under dynamically controllable conditions with integrated microfluidics and software. Nat Commun. 2018; 9: 212. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalingam N, Fowler B, Szpankowski L, Leyrat AA, Hukari K, Maung MT, et al. Fluidic Logic Used in a Systems Approach to Enable Integrated Single-Cell Functional Analysis. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2016; 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unger MA, Chou H-P, Thorsen T, Scherer A, Quake SR. Monolithic Microfabricated Valves and Pumps by Multilayer Soft Lithography. Science. 2000; 288: 113–116. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melin J, Roxhed N, Gimenez G, Griss P, van der Wijngaart W, Stemme G. A liquid-triggered liquid microvalve for on-chip flow control. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2004; 100: 463–468. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).