Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

20 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

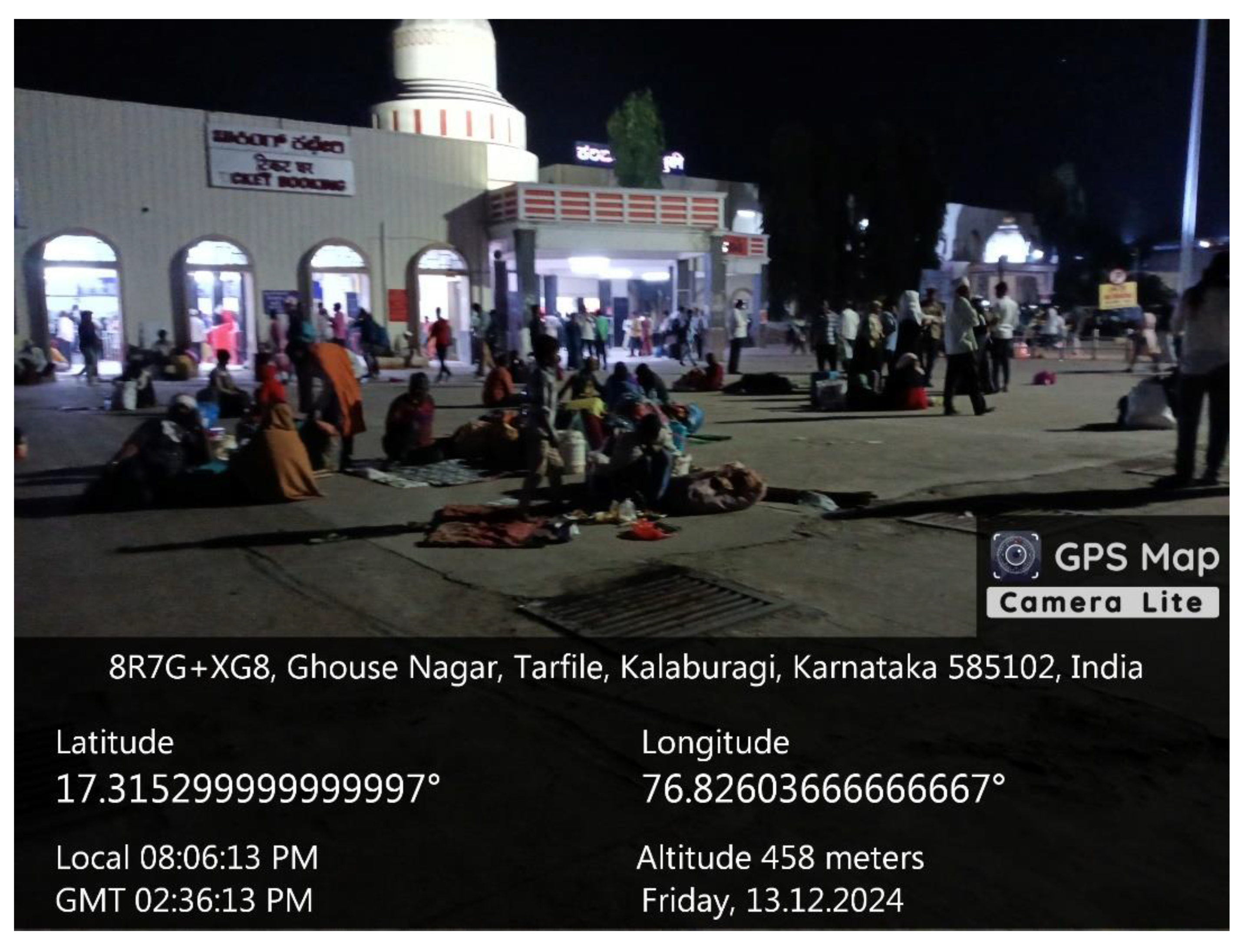

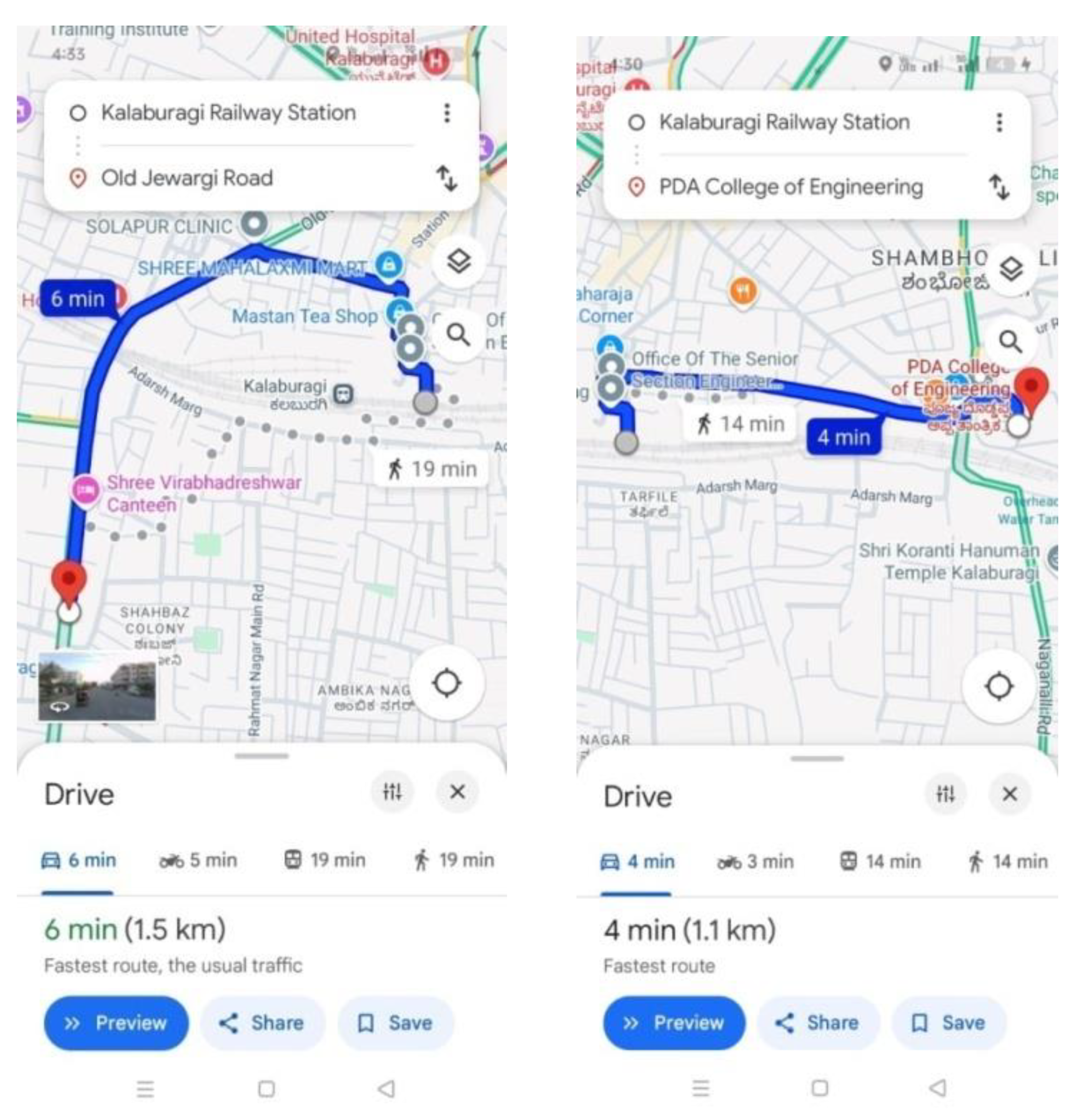

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Study of Experimental Design

- Height and width of the walkway

- Smoothness and regularity of the walkway surface

- Continuity of the walkway

- Ramps connecting the walkway to the road

- Lighting at night

- Barriers like pipe railings or handrails separating traffic

- Obstructions on the walkway

- Maintenance and cleanliness

- Raised crossings for continuous walking

- Walkways available on the correct side of the road.

- The walkway is located on the appropriate side of the carriageway.

- Connectivity

- Zoning and Way finding

- Safety and Security

- Walkway Characteristics

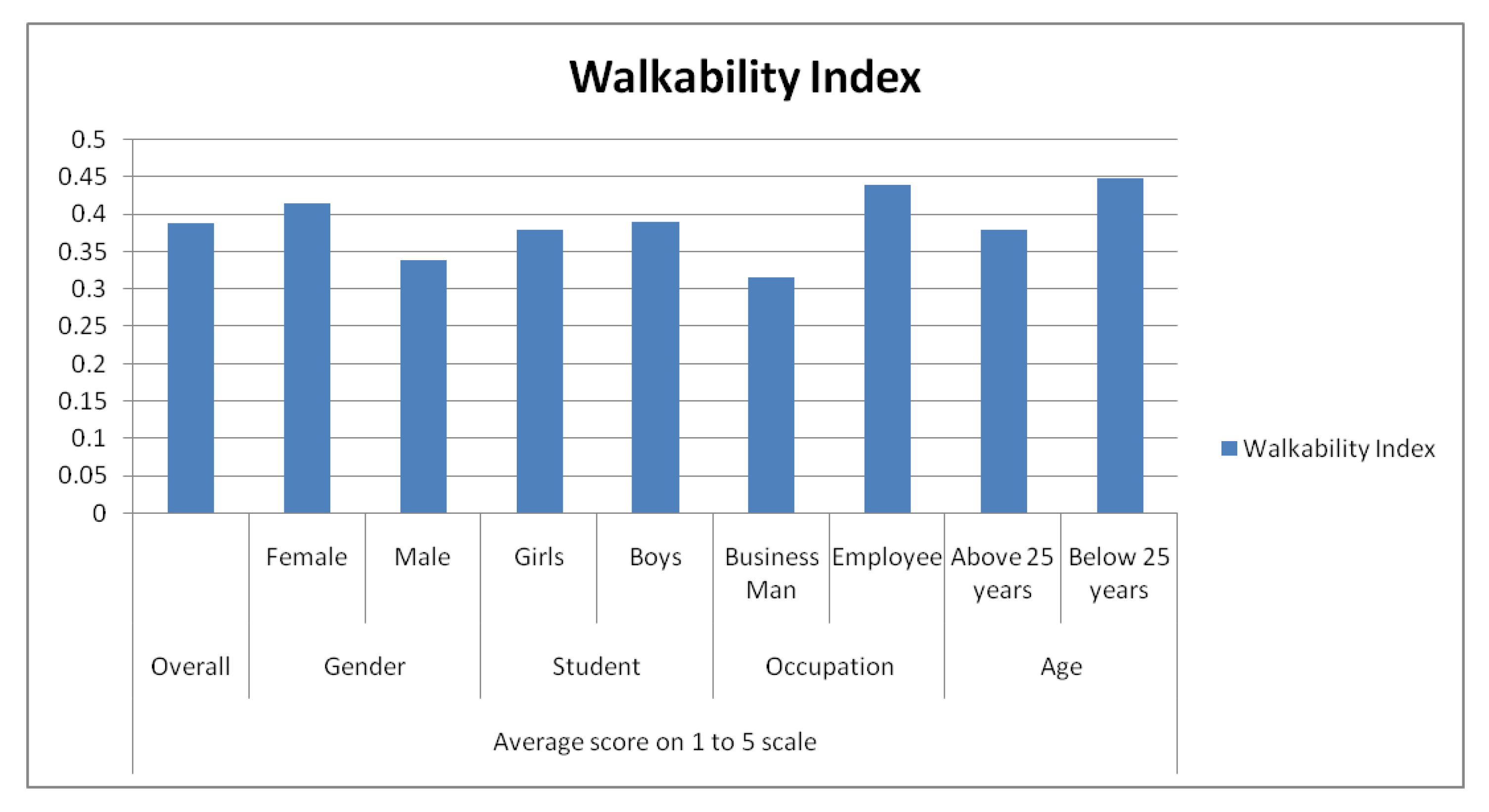

3. Results and Discussions

- 1.

-

Strengths:

- a) Walkway Height (3.01): This score suggests that the height of the walkways is generally suitable, although some variability or inconsistencies may be present in specific locations. Overall, it indicates that pedestrians can navigate comfortably, though minor modifications could enhance uniformity.

- b) Walkway Width (3.39): The moderate score reflects that the width of the walkways is generally adequate for pedestrian traffic. However, in areas with high footfall, the walkways may feel narrow or congested, indicating a potential need for expansion to better accommodate larger groups of pedestrians.

- c) Walkway Continuity (3.73): A relatively high score signifies that most walkways are uninterrupted, which is crucial for maintaining pedestrian flow. Nonetheless, there may be certain gaps or obstructions that could hinder convenience for pedestrians

- d) Unobstructed Walkway Access (3.52): This score indicates that the majority of walkways are free from obstructions, facilitating ease of movement. However, there may still be occasional obstacles that could disrupt pedestrian flow.

- e) Maintenance and Cleaning (3.6): This score indicates a generally favorable condition, implying that the walkways are typically well-maintained and receive regular cleaning. Nonetheless, there may be occasional instances of neglect, particularly in areas with high foot traffic or those that are less frequently monitored.

- f) Walkway Location (3.49): This score implies that the majority of walkways are appropriately situated on the correct side of the roadway, facilitating safer movement for pedestrians. However, there may be some cases where walkways are incorrectly positioned or inadequately aligned with the needs of pedestrians.

- g) Connectivity (3.06): This score denotes a moderate level of connectivity among various pedestrian zones. While certain walkways are effectively linked to significant destinations, others may exhibit gaps in connectivity, which can hinder pedestrian access to essential locations.

- h) Walkway Characteristics (3.5): A moderate rating in this category suggests that most walkways possess acceptable features, such as adequate width and essential amenities. However, there is potential for enhancements, including improved landscaping or the incorporation of seating areas.

- 2.

-

Moderate Aspects:

- a) Surface Quality (2.84): This rating indicates a notable issue with the condition of the walkways. The surfaces may be uneven or inadequately maintained in certain areas, posing risks for pedestrians, especially those with mobility impairments. Enhancements are essential to provide smooth and level walkways for safer navigation.

- b) Traffic Separators (2.91): This score implies that while traffic separators, such as railings or barriers, are present in some locations, they are either insufficient in number or not entirely effective. These elements are crucial for safeguarding pedestrians from vehicular traffic, and a more uniform installation could enhance safety.

- 3.

-

Weaknesses:

- a) Nighttime Illumination (2.39): This low rating indicates a lack of adequate lighting, which can pose safety risks for pedestrians at night. Insufficient illumination contributes to an unsafe environment, particularly for individuals walking after dark.

- b) Ramps for Carriageway Connection (2.42): This score indicates that ramps, which are vital for accessibility, are either missing or inadequate. This presents a significant challenge for individuals with disabilities or those using strollers or wheelchairs. Considerable improvements are required to ensure accessible transitions between the walkway and the carriageway.

- c) Raised Continuous crossing (2.01): The very low score in this category suggests that raised crossings are either nonexistent or insufficient. These crossings are essential for pedestrian safety, and their absence increases the difficulty and danger of crossing streets.

- d) Zoning and Way finding (2.27): A low score in this area points to inadequate signage and way finding systems, complicating navigation for pedestrians. Improved signage and better zoning would facilitate pedestrian orientation and enhance ease of movement.

- e) Safety and Security (2.67): This score reflects concerns regarding pedestrian safety and security. While some safety measures may exist, they appear to be insufficient or not effectively enforced, leaving pedestrians vulnerable to accidents or crime.

4. Conclusions

References

- Ministry of Urban Development, (2008), “Study of traffic and transportation policies in urban areas in India”.

- Litman, T.A. Economic Value of Walkability. Transp. Res. Rec. 2003, 1828, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burden, D. Building communities with transportation. Transp. Res. Rec. 2001, 1773, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw C. (1993), “Creating and Using A Rating System for Neighborhood Walkability towards an Agenda for Local Heroes”, 14th International Pedestrian Conference, Boulder, Colorado.

- Southworth, M. (2005), “Designing the Walkable City”, J. Urban Plann. Dev. vol: 0733-948, pp131:4.

- Litman, T.A. (2011), “Economic Value of Walkability”, Transportation Research Board 2003, pp. 3-11 and in Volume 10.

- Improving Walkability (2005), Transport for London, The London Planning Advisory Committee, Mayor of London, London.

- Walkability in Indian cities, (2011), Clean Air Initiative for Asian cities (CAI-Asia) centre.

- Chalermpong, S., Wibowo, S.S. (2007) Transit Station Access Trips and Factors Affecting Propensity to Walk to Transit Stations in Bangkok Thailand, Journal of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, Vol 7, No.0, 1806-1819.

- ((2014) Measuring Pedestrians’ Satisfaction of Urban Environment under Transit Oriented Development (TOD): A case study of Bangkok Metropolitan, Thailand, Lowland Technology International, Vol.16, No.2, 125-134.

- Redefining walkability to capture safety: Investing in pedestrian, bike, and street level design features to make it safe to walk and bike Behram Wali ,wrence D. Frank Volume 181, March 2024, 103968. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice). [CrossRef]

- Jonas De Vos et al., 2020)(Jonas De Vos, Katrin Lättman, Anna-Lena van der Vlugt, Janina Welsch & Noriko Otsuka (2022): Determinants and effects of perceived walkability: a literature review, conceptual model and research agenda, Transport Reviews.

- Huang, X. , Zeng, L., Liang, H. et al. Comprehensive walkability assessment of urban pedestrian environments using big data and deep learning techniques. Sci Rep 14, 26993 2024.

- Huang, X. , Zeng, L., Liang, H. et al. Comprehensive walkability assessment of urban pedestrian environments using big data and deep learning techniques. Sci Rep 14, 26993 2024.

- “Chronology of railways in India, Part 2 (1870–1899). “IR History: Early Days—II”. IRFCA. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- “Sholapur District Gazetteer”. Gazetteer department. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- “Railway bridge across Bennethora to be complete in two years”. The Hindu. 24 July 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- “Bidar-Gulbarga rail service”. Infrastructure. January 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

| SL.No | Attribute | Average rating on a scale of 1 to 5 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Gender | Student | Occupation | Age | ||||||

| Female | Male | Girls | Boys | Business Man | Employee | Above 25 years | Below 25 years | |||

| 1. | The height of the walkway is suitable. | 3.01 | 2.34 | 3.36 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 2.56 | 3.5 | 2.67 | 3.4 |

| 2. | The path is wide enough. | 3.39 | 3.15 | 3.77 | 3.1 | 3.45 | 3.0 | 3.97 | 3.0 | 3.75 |

| 3. | The surface is flat and smooth. | 2.84 | 2.45 | 3.66 | 3.0 | 1.75 | 2.0 | 3.54 | 2.8 | 3.5 |

| 4. | The walkway is uninterrupted. | 3.73 | 3.32 | 3.76 | 4.5 | 3.7 | 3.45 | 3.83 | 3.5 | 3.78 |

| .5. | Ramps are provided for connection to the carriageway. | 2.42 | 2.33 | 2.9 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.6 |

| 6. | Nighttime illumination is adequate. | 2.39 | 2.16 | 2.45 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 1.95 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 2.9 |

| 7. | A traffic separator, such as a pipe railing, is installed. | 2.91 | 3.20 | 3.76 | 2.3 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 2.75 | 2.4 | 3.0 |

| 8. | The entire width is unobstructed and fully accessible. | 3.52 | 3.0 | 3.66 | 2.7 | 4.0 | 3.15 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 4.0 |

| 9. | Walkways are well-maintained and regularly cleaned. | 3.6 | 3.5 | 4.4 | 1.2 | 4.5 | 3.67 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 4.0 |

| 10. | A raised continuous crossing is available. | 2.01 | 1.5 | 2.33 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 1.66 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| 11. | The walkway is found on the carriageway’s proper side. | 3.49 | 2.5 | 3.66 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 3.54 | 4.0 | 3.4 | 4.0 |

| 12. | Connectivity | 3.06 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 1.3 | 3.67 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 4.0 |

| 13. | Zoning and Way finding | 2.27 | 2.4 | 2.17 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 2.3 |

| 14. | Safety and Security | 2.67 | 3.57 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 3.55 | 1.4 | 3.5 |

| 15. | Walkway Characteristics | 3.5 | 2.5 | 3.66 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 3.54 | 4.0 | 3.4 | 4.0 |

| Average | 2.98 | 3.16 | 3.33 | 2.8 | 2.93 | 2.71 | 3.4 | 2.79 | 3.44 | |

| Walkability Index | 0.389 | 0.416 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.317 | 0.44 | 0.379 | 0.449 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).