Introduction

Gastrointestinal malignancies are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide (1). Recently, there has been an increasing interest in assessing body composition for nutritional evaluation and prognosis determination in patients diagnosed with this type of cancer. Sarcopenia is a condition characterized by progressive and generalized loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and function in the context of aging (2). Numerous studies have demonstrated the adverse effects of sarcopenia on cancer outcomes; these include increased risk of postoperative complications, prolonged hospital stay, poor quality of life, intolerance to anticancer therapy, and decreased overall survival (3-6). Accurate assessment and timely intervention may prevent or mitigate chemotherapy-related muscle toxicity, improving treatment outcomes and life quality (5, 7, 8). Sarcopenia is often multifactorial, especially in cancer patients. It can be affected by the cancer itself (through mechanisms such as cancer cachexia), nutritional deficiencies, decreased physical activity, and the aging process. The toxic effects of chemotherapy, such as nausea, vomiting, and fatigue, can lead to reduced food intake and decreased physical activity, which contributes to muscle wasting. Therefore, observing the change before and after chemotherapy in the same person can be used to examine the relationship between chemotherapy and sarcopenia.

Few articles on the relationship between sarcopenia and chemotherapy define sarcopenia as low muscle mass measured by computed tomography but do not evaluate muscle strength and performance. However, according to the new European Working Group on Sarcopenia of Older People (EWGSOP-2) 2018 criteria, it is not appropriate to diagnose sarcopenia by measuring muscle mass alone (2). It has become essential to investigate the impact of other components of sarcopenia (the combination of low muscle mass plus low muscle strength or low physical performance) that determine the actual functionality.

Our aim in this study was to examine whether sarcopenia developed in patients with gastrointestinal cancer receiving chemotherapy treatment and whether their condition changed compared to before chemotherapy. We also wanted to investigate whether chemotherapy affected comprehensive geriatric assessment results among older participants.

Methods

Study Participants

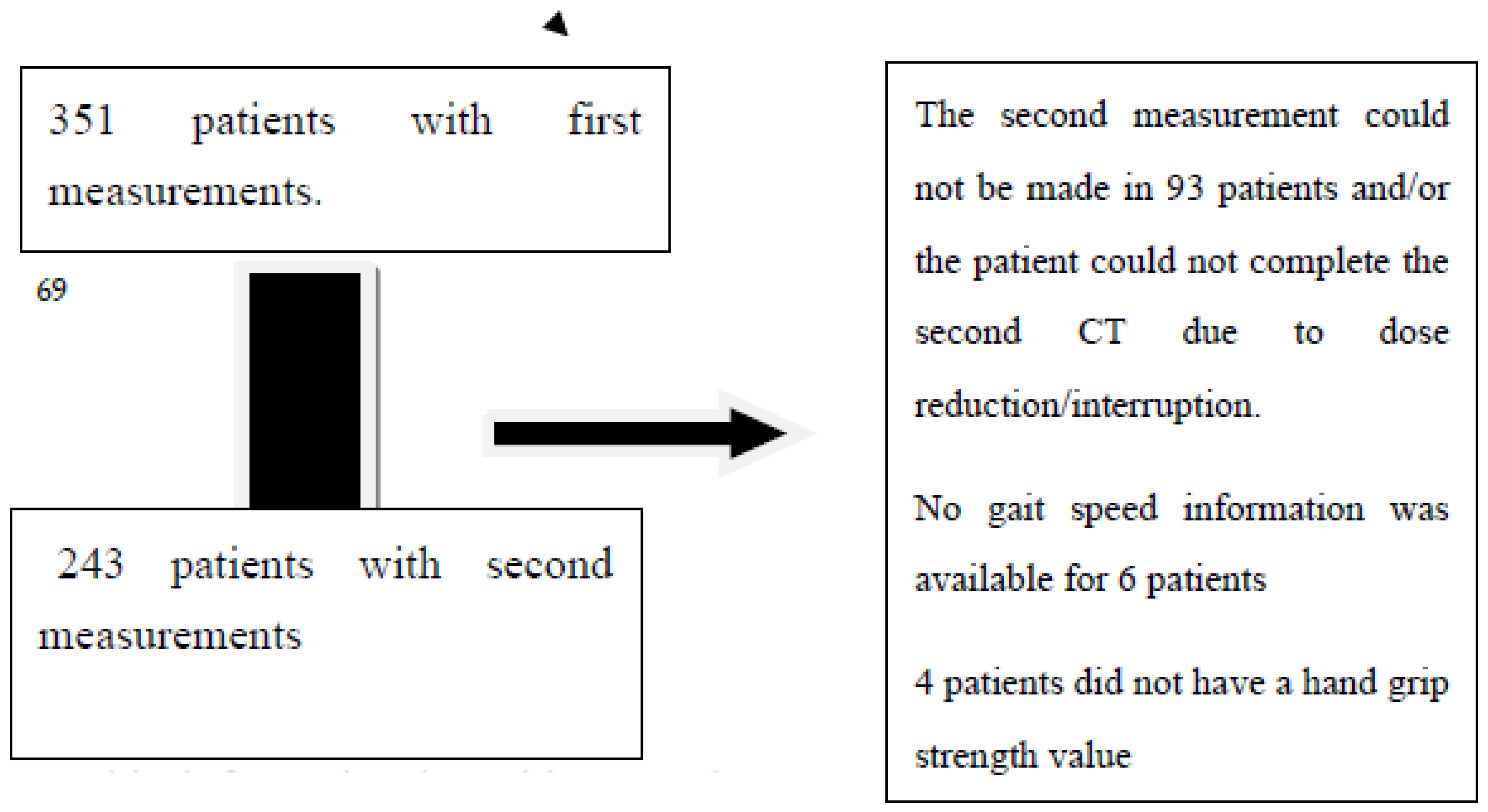

This cross-sectional study included 351 patients who were diagnosed with gastrointestinal system cancer from October 2018 to December 2019. Measurements were taken before chemotherapy, and second measurements were obtained before the next dose. Out of the initial sample, 243 patients participated in the post-chemotherapy measurement. The study included patients with cancer at any stage and patients who would not undergo surgery during the follow-up period. For more information, please refer to

Figure 1.

Demographic information in Tables 1 and 2 was collected for all participants. Body component measurements, gait speed, and hand grip strength were assessed using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA). A comprehensive geriatric assessment was conducted for the older group (≥65 years old). Data from patients who underwent chemotherapy treatment were compared before and after the treatment.

Sarcopenia Measurement

Sarcopenia was diagnosed according to the EWGSOP-2 criteria (2). Muscle mass measurement with BIA; muscle strength measurement by hand grip strength; physical performance evaluation was made by measuring gait speed (m/sec). BIA was performed with a portable BIA analyzer in the supine position. Quadscan 4000 (Bodystat, Douglas, Isle of Man, United Kingdom) was used as the BIA device. Resistance measurement was made in ohms (Ω). The device was adjusted according to the participant's age, gender, height, and weight. Skeletal muscle mass (SMM) was calculated according to the formula Janssen et al. suggested (9). Low muscle mass was calculated according to values reported in studies on Turkish populations. In this study, values below 9.2 kg/m2 in men and 7.4 kg/m2 in women were taken as low muscle mass (10). In our study, muscle strength was measured with the hand grip test. The average of three handgrip values with the dominant hand was taken to determine the participants' handgrip strength. Local cut-off values were used as recommended by EWGSOP-2 (grip strengths <22 kg in females and <32 kg in males) (10). Skeletal muscle mass was evaluated with BIA. Those with low muscle strength were defined as possible sarcopenia. If low muscle strength was supported by measurement (low skeletal muscle mass), confirmed sarcopenia was diagnosed. If low physical performance was added to these, severe sarcopenia was diagnosed.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

Comprehensive geriatric assessment tests included the Katz Activities of Daily Living Index (ADL), Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (IADL), mini-mental status examination (MMSE), and mini-nutritional assessment short form (MNA-SF). Hand grip strength is measured by an electronic hand dynamometer (GRIP-D, produced by Takei, made in Japan). The unit of results is kilograms. The gait speed measured on a 4-meter course in m/s assessed muscle performance. The gait speed was evaluated in favor of decreased muscle performance as ≤0,8 m/ sec.

Statistical Analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows version 24.0 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used. The conformity of the variables to a normal distribution was examined using visual (histograms and probability graphs) and analytical (Kolmogorov-Smirnov/Shapiro-Wilk tests) methods. The results of the descriptive analyses were presented in mean and standard deviation for the normally distributed variables and median and minimum-maximum for the non-normally distributed variables. The frequency of the categorical variables was presented in percentages (%). The Wilcoxon test evaluated intergroup comparisons in Table 2. Categorical variables in Table 3 were compared with the McNemar test. The correlations between customarily distributed numerical variables were assessed with the Pearson test, and the non-normally distributed variables were evaluated with the Spearman test. The results were assessed in a 95% confidence interval, and a p-value of <0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Ethics Committee Approval

The local Hospital ethics committee approved the study. The patients provided written informed consent.

Results

The median age of 243 patients was 57.84 (IQR: 26-79). The female gender ratio was 31.7% (n: 77). 29.2% (n: 71) of the participants were 65 years and older. The demographic data of the participants are summarized in

Table 1.

An initial evaluation of the patient was made before treatment. Measurements were taken before and after chemotherapy. An analysis compared preCT and postCT measurements with a time gap of 62.06±25.61 days. PostCT values for BMI and muscle mass were significantly lower, indicating a decrease in these parameters. Additionally, there was a significant increase in the rate of sarcopenia after chemotherapy. In older patients, both muscle mass and albumin levels decreased significantly postCT, while the prevalence of sarcopenia increased considerably. The Lawton-Brody score also showed a significant decline; however, no notable differences were found in geriatric assessment tests (

Table 2).

A significant difference in sarcopenia groups between before (preCT) and after chemotherapy (postCT) was observed. Of the 105 patients, 43.2% were classified as usual before chemotherapy. In contrast, 7.4% had probable sarcopenia, 16.9% confirmed sarcopenia, and 4.1% had severe sarcopenia after chemotherapy, resulting in a total of 28.4% being diagnosed with some form of sarcopenia post-treatment. This finding was statistically significant (Z:88.93, p<0.001). Detailed data can be found in

Table 3

In additional analyses of 71 older people who participated in the study, it was determined that of 30 people who were not sarcopenic preCT, 23 were sarcopenic on postCT to varying degrees. The difference between the two measurements was statistically significant. (McNemar test, Z: 15.67, p: .016) No significant difference was found between these two groups when comparing comprehensive geriatric tests pre- and post-CT. (By Wilcoxon test, for Katz Z: .102 p:.989, for Lawton-Brody: -.270 p:.787, for MNA-SF Z:-.040 p:.978, for MMSE Z: -247 p: .805 )

Discussion

In this study, we investigated chemotherapy's effects on sarcopenia in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. The findings revealed a notable rise in the prevalence of sarcopenia among individuals undergoing chemotherapy. Furthermore, all patient groups experienced a decline in muscle mass and BMI. Additionally, a decrease in Lawton-Brody score was observed in older patients. After chemotherapy, there was a noticeable but not statistically significant reduction in gait speed and handgrip strength.

In many oncology studies, imaging methods are commonly used to assess muscle mass for diagnosing sarcopenia. However, it is essential to note that the strength of this study lies in its utilization of the EWGSOP-2 criteria, which not only considers muscle mass but also incorporates factors such as muscle strength and functionality in determining sarcopenia. In this study conducted with a Turkish population, sarcopenia was evaluated based on the EWGSOP-2 criteria utilizing specific cut-off values. Interestingly, individuals initially classified as normal preCT subsequently transitioned into the sarcopenic group, while those within less severe categories within the sarcopenic group progressed towards more severe classifications (

Table 3). These findings align with existing literature (11-14). Patients undergoing chemotherapy may experience sarcopenia as a result of their treatment. Regardless of the stage or type of cancer, there is a significant reduction in indicators of sarcopenia following chemotherapy. The decrease can be attributed to the side effects of drugs, loss of appetite, fatigue, metabolic changes after treatment, and the catabolic processes induced by chemotherapy, along with a decline in anabolic processes (5, 6, 15, 16).

Studies have found that handgrip strength is more important than muscle mass in determining survival and functionality in daily life (14, 17, 18). In our study, although gait speed and handgrip strength were significantly lower after chemotherapy, this difference was not statistically significant. The increase in sarcopenia rate may not yet be reflected in functionality because the average interval between measurements is 60 days. Other factors that could contribute to these findings include the unequal representation of male and female participants, a relatively small sample size, and only one measurement of sarcopenia. Additionally, it is worth noting that gait speed and handgrip strength comparisons were based on numerical values rather than specific cutoffs. It should be considered that normal limits for cancer patients may differ from those of the general population.

Another important finding is that 23 out of 30 older patients developed sarcopenia after chemotherapy. There was a significant decrease in muscle mass and albumin levels, along with an increased rate of sarcopenia among the older patients. This finding suggests that older individuals may be more prone to developing sarcopenia as a result of chemotherapy. Sarcopenia is commonly associated with the natural decline in muscle mass and function with age. Furthermore, chemotherapy-induced fatigue may restrict physical activity and contribute to further muscle loss. Additionally, due to the weakened immune system resulting from chemotherapy treatments, older individuals may become more susceptible to infections, leading to muscle wasting (15, 19, 20).

Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) was performed pre and post-chemotherapy to observe the effect of chemotherapy on older patients. Patient selection with CGA before treatment is now a frequently used and recommended method in older patients with cancer (21-24). In our study, the Lawton-Brody score, which provides information about instrumental life activities, decreased significantly post-chemotherapy. These findings might explain the high sarcopenia rates in older patients after treatment. Although handgrip strength and gait speed, closely related to daily functionality, are not affected statistically, the daily instrumental living activity score is affected negatively, meaning that patients may have experienced daily functional difficulties. This might be due to our study's relatively small number of older people.

Several factors were found to be correlated with toxicity, including gender, low handgrip strength before and after chemotherapy, and low gait speed after chemotherapy. Previous studies have shown low handgrip strength increases mortality during cancer treatment(14, 18, 25, 26). Low handgrip strength may be an indicator of sarcopenia and muscle mass loss and has been associated with adverse outcomes of gastrointestinal cancer treatment. Individuals with low handgrip strength may experience a decrease in their overall quality of life, as it can restrict their ability to perform daily activities and comply with treatment protocols. Some studies have shown an association between low gait speed and increased mortality during cancer treatment (27-29). Gait speed and physical activity levels are important indicators that reflect a person's health, endurance, and muscle mass. Although handgrip strength and slow gait speed are easily measurable and reliable indicators of functional decline in older adults, further research is necessary to determine the optimal threshold values for these measures in chemotherapy-induced toxicity. It is essential to consider that a comprehensive assessment, which takes into account various factors, is necessary for accurate prediction and prevention of chemotherapy-induced toxicity in older adults (30). While low handgrip strength and slow gait speed are associated with toxicity after chemotherapy, it is essential to establish standardized measurement values for assessing these parameters in older adults undergoing chemotherapy.

This study is notable for its interdisciplinary approach and comprehensive assessment of older individuals. The diagnosis of sarcopenia was based on the revised EWGSOP-2 criteria. To ensure consistent evaluation, the same researchers performed follow-up measurements. However, this study has limitations.

It is an observational cross-sectional study, which does not establish chronological or causal relationships. Although the study showed an association between chemotherapy and increased sarcopenia, it was not designed to show chemotherapy as the sole cause of sarcopenia. Many reasons may cause patients to become sarcopenic during the chemotherapy process. A more controlled study design, such as a longitudinal study or a randomized controlled trial, would be needed to prove that sarcopenia is caused entirely by chemotherapy. This involves comparing a group of patients receiving chemotherapy with a control group not receiving chemotherapy while controlling for other variables such as disease stage, nutritional intake, physical activity, and general health status.

Based on the results, the number of included patients, especially older ones, may be considered low. Additionally, the average 60-day follow-up period might be insufficient to assess the impact of sarcopenia on functionality. Future studies could extend this period and include intermediate measurements. Furthermore, biochemical markers other than albumin related to sarcopenia were not assessed.

Conclusions

This study highlights the potential link between chemotherapy and sarcopenia in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies, resulting in higher toxicity. Detecting sarcopenia early on and implementing intervention strategies are crucial for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Evaluating nutritional status and physical activity during diagnosis is essential for assessing the risk of developing sarcopenia and taking necessary precautions. Well-controlled double-blind prospective studies are required to reinforce these findings.

Author Contributions

Kamile Sılay:Methodology, investigation, data curation, Writing editing Gokhan Ucar:Conceptulization. Methodology, softwareTulay Eren: Data curation ,investigation, writing, softwareHande Selvi Oztorun: Formal analysis, writingOzan Yazici:Resources, writingNuriye Ozdemir:Methodology, Writing, supervision.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2021;71(3):209-49. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age and ageing. 2019;48(1):16-31. [CrossRef]

- Zhang FM, Wu HF, Shi HP, et al. Sarcopenia and malignancies: epidemiology, clinical classification and implications. Ageing research reviews. 2023;91:102057. [CrossRef]

- Nipp RD, Fuchs G, El-Jawahri A, et al. Sarcopenia Is Associated with Quality of Life and Depression in Patients with Advanced Cancer. The oncologist. 2018;23(1):97-104. [CrossRef]

- Simonsen C, de Heer P, Bjerre ED, et al. Sarcopenia and Postoperative Complication Risk in Gastrointestinal Surgical Oncology: A Meta-analysis. Annals of surgery. 2018;268(1):58-69. [CrossRef]

- Bossi P, Delrio P, Mascheroni A, et al. The Spectrum of Malnutrition/Cachexia/Sarcopenia in Oncology According to Different Cancer Types and Settings: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2021;13(6). [CrossRef]

- Hong S, Kim KW, Park HJ, et al. Impact of Baseline Muscle Mass and Myosteatosis on the Development of Early Toxicity During First-Line Chemotherapy in Patients With Initially Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. Frontiers in oncology. 2022;12:878472. [CrossRef]

- Boshier PR, Heneghan R, Markar SR, et al. Assessment of body composition and sarcopenia in patients with esophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diseases of the esophagus : official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus. 2018;31(8). [CrossRef]

- Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Baumgartner RN, et al. Estimation of skeletal muscle mass by bioelectrical impedance analysis. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md : 1985). 2000;89(2):465-71. [CrossRef]

- Bahat G, Tufan A, Tufan F, et al. Cut-off points to identify sarcopenia according to European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) definition. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2016;35(6):1557-63. [CrossRef]

- Daly LE, Bhuachalla EBN, Power DG, et al. Loss of skeletal muscle during systemic chemotherapy is prognostic of poor survival in patients with foregut cancer. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia, and muscle. 2018;9(2):315-25. [CrossRef]

- Kamarajah SK, Bundred J, Tan BHL. Body composition assessment and sarcopenia in patients with gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2019;22(1):10-22. [CrossRef]

- Bozzetti F. Chemotherapy-Induced Sarcopenia. Current treatment options in oncology. 2020;21(1):7. [CrossRef]

- Moreau J, Ordan MA, Barbe C, et al. Correlation between muscle mass and handgrip strength in digestive cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Cancer medicine.2019;8(8):3677-84. [CrossRef]

- Oflazoglu U, Alacacioglu A, Varol U, et al. The role of inflammation in adjuvant chemotherapy-induced sarcopenia (Izmir Oncology Group (IZOG) study). Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2020;28(8):3965-77. [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama K, Narita Y, Mitani S, et al. Baseline Sarcopenia and Skeletal Muscle Loss During Chemotherapy Affect Survival Outcomes in Metastatic Gastric Cancer. Anticancer research. 2018;38(10):5859-66. [CrossRef]

- Nasu N, Yasui-Yamada S, Kagiya N, et al. Muscle strength is a stronger prognostic factor than muscle mass in gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary pancreatic cancer patients. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif). 2022;103-104:111826. [CrossRef]

- Perrier M, Ordan MA, Barbe C, et al. Dynapenia in digestive cancer outpatients: association with markers of functional and nutritional status (the FIGHTDIGO study). Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2022;30(1):207-15. [CrossRef]

- de Jong C, Chargi N, Herder GJM, et al. The association between skeletal muscle measures and chemotherapy-induced toxicity in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia, and muscle. 2022;13(3):1554-64. [CrossRef]

- Oflazoglu U, Alacacioglu A, Varol U, et al. Chemotherapy-induced sarcopenia in newly diagnosed cancer patients: Izmir Oncology Group (IZOG) study. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2020;28(6):2899-910. [CrossRef]

- Hamaker M, Lund C, Te Molder M, et al. Geriatric assessment in the management of older patients with cancer - A systematic review (update). Journal of geriatric oncology. 2022;13(6):761-77. [CrossRef]

- Li D, Sun CL, Kim H, et al. Geriatric Assessment-Driven Intervention (GAIN) on Chemotherapy-Related Toxic Effects in Older Adults With Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA oncology. 2021;7(11):e214158. [CrossRef]

- Fusco D, Ferrini A, Pasqualetti G, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in older adults with cancer: Recommendations by the Italian Society of Geriatrics and Gerontology (SIGG). European journal of clinical investigation. 2021;51(1):e13347. [CrossRef]

- Lee W, Cheng SJ, Grant SJ, et al. Use of geriatric assessment in cancer clinical trials: A systematic review. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2022;13(7):907-13. [CrossRef]

- Martin P, Botsen D, Brugel M, Bertin E, Carlier C, Mahmoudi R, et al. Association of Low Handgrip Strength with Chemotherapy Toxicity in Digestive Cancer Patients: A Comprehensive Observational Cohort Study (FIGHTDIGOTOX). Nutrients. 2022;14(21). [CrossRef]

- da Rocha IMG, Marcadenti A, de Medeiros GOC, et al. Is cachexia associated with chemotherapy toxicities in gastrointestinal cancer patients? A prospective study. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle. 2019;10(2):445-54. [CrossRef]

- Beukers K, Bessems SAM, van de Wouw AJ, et al. Associations between the Geriatric-8 and 4-meter gait speed test and subsequent delivery of adjuvant chemotherapy in older patients with colon cancer. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2021;12(8):1166-72. [CrossRef]

- Dociak-Salazar E, Barrueto-Deza JL, Urrunaga-Pastor D, et al. Gait speed as a predictor of mortality in older men with cancer: A longitudinal study in Peru. Heliyon. 2022;8(2):e08862. [CrossRef]

- Williams GR, Chen Y, Kenzik KM, et al. Assessment of Sarcopenia Measures, Survival, and Disability in Older Adults Before and After Diagnosis With Cancer. JAMA network open. 2020;3(5):e204783. [CrossRef]

- Quinn GP, Schabath MB. Quality of Life in Underrepresented Cancer Populations. Cancers. 2022;14(14). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).