1. Introduction

Major hepato-biliary-pancreatic (HBP) surgery, defined in Japan as a high-level HBP surgery, is associated with various serious complications and high perioperative mortality [

1]. According to the Japan National Clinical Database, although the postoperative hospital stay and perioperative mortality rates among patients undergoing major hepatectomy and pancreaticoduodenectomy are lower in Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery (JSHBPS) board-certified training institutions than in other institutions, the rates are still higher than for other gastrointestinal cancer surgeries and thus require improvement [

1].

Sarcopenia in patients undergoing gastrointestinal cancer surgery is a risk factor for postoperative complications and a poor prognosis, and assessment and continuous monitoring of sarcopenia has become an important issue in clinical practice [

2,

3,

4]. Patients with pancreatic cancer may suffer from pancreatic exocrine insufficiency as a result of pancreatic duct obstruction, diabetes mellitus, obstructive jaundice, or cholangitis, and many patients show preoperative weight loss, malnutrition, and sarcopenia [

4,

5]. The usefulness of HBP surgery, sarcopenia evaluation, perioperative management, and rehabilitation has therefore attracted attention [

4,

5,

6].

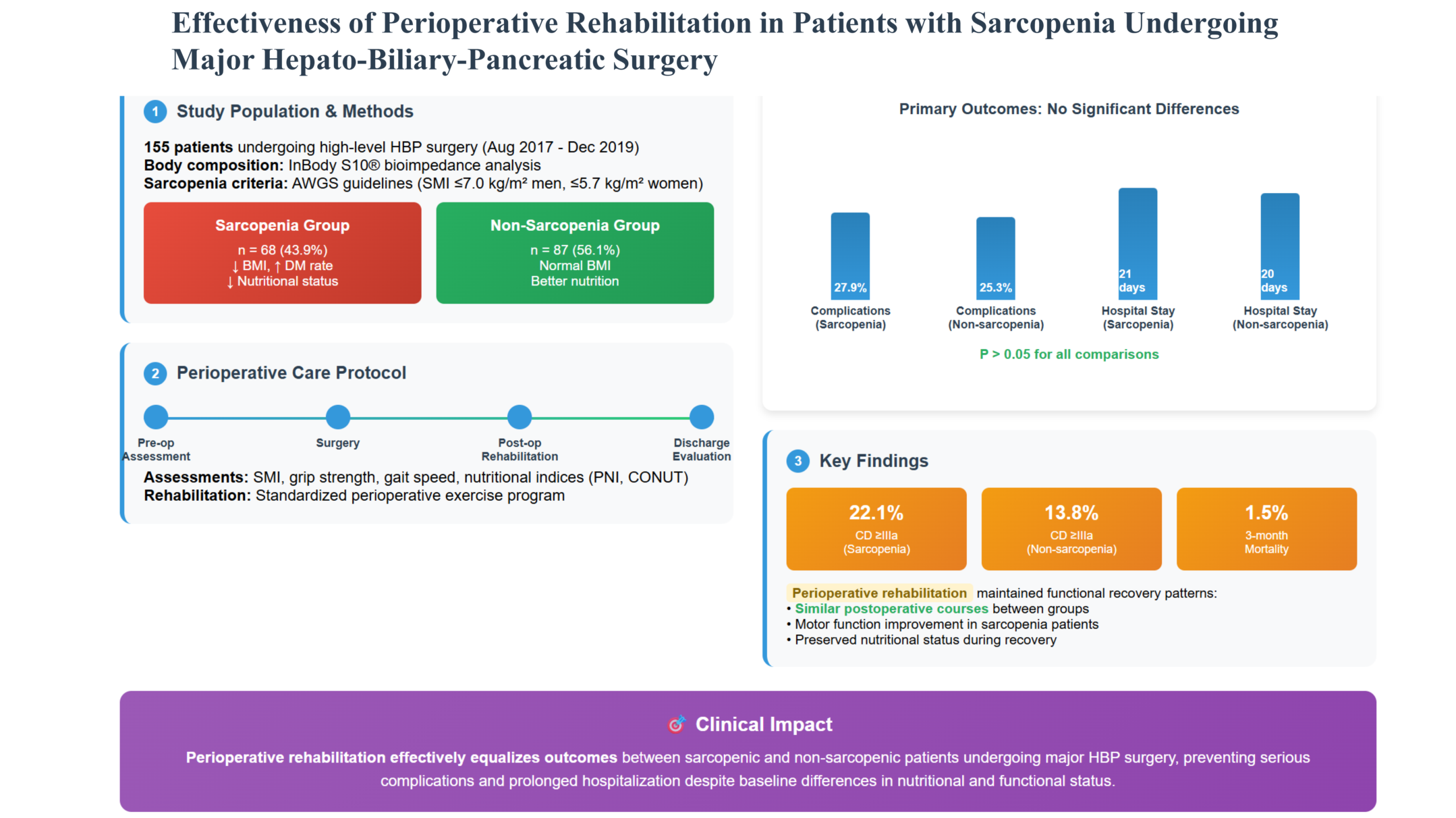

The aim of this study was to clarify the effectiveness of perioperative rehabilitation for patients with sarcopenia undergoing high-level HBP surgery in our institution, compared with patients without sarcopenia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Defining High-Level HBP Surgery

The JSHBPS has designated 28 surgeries as high-level HBP surgeries, including four categories: hepatobiliary surgery (11 types), hepatopancreatic surgery (1 type), pancreatic surgery (11 types), and HBP surgery requiring vascular resection and reconstruction (5 types) [

1].

2.2. Patients

We enrolled 155 adult patients who underwent high-level HBP surgery in Asahikawa Medical University Hospital from August 2017 until December 2019. Study approval was obtained from the Ethics and Indications Committee of Asahikawa Medical University.

2.3. Defining Sarcopenia

Patient body composition was estimated using multifrequency bioimpedance analysis with an InBody S10® analyzer (Biospace Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea). The InBody uses an eight-point tetrapolar electrode system that assesses impedance at six specific frequencies (1, 5, 50, 250, 500, and 1000 kHz), and impedance at three specific frequencies (5, 50, and 250 kHz) with a small alternate electrical current applied on the body. Bioimpedance measurements were performed by trained staff according to standardized procedures. The measurements were conducted on the dominant side of the body (right side in most patients). The patients fasted overnight, emptied their bladders by urinating, and measurements were made with the patient unclothed and in a standing posture, at an ambient temperature of 25°C. After collecting the data, the skeletal muscle index (SMI) was calculated by normalizing the skeletal muscle mass for height (kg/m

2). Sarcopenia has previously been defined as a decrease in SMI [

7]. We therefore defined the sarcopenia (S) group as patients with an SMI ≤ 7 kg/m

2 for men or ≤ 5.7 kg/m

2 for women, in accordance with the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) criteria [

8]. Patients without sarcopenia constituted the non-sarcopenia (NS) group.

2.4. Data

We retrospectively reviewed the enrolled patients’ medical records to retrieve the following data: general clinical information (age, sex, body mass index (BMI), body fat percentage, and SMI), presence of diabetes mellitus, surgical data (type of high-level HBP surgery), gait speed, hand-grip strength, postoperative surgical and medical complications, and survival. Gait speed was determined by measuring the time taken for patients to walk a straight, 10-m course at their usual speed and was calculated as meters per second (m/s). Muscle strength was assessed by measuring hand-grip strength using a digital grip-strength dynamometer. Hand-grip strength was measured twice, and the average of the two values for the dominant hand was used as the mean grip strength in the analysis. Events occurring within 30 days after surgery were classified as postoperative complications or mortality. The Clavien–Dindo (CD) classification was used to rate the severity of each postoperative complication [

9]. The presence of postoperative complications in this study was defined as CD grade ≥ II and serious complications were defined as grade III (there were no grade IV or V complications). Refractory ascites and pleural effusion (PE) were defined as conditions that did not respond to conservative treatment and required invasive treatment. Nutritional indices were generated from preoperative blood test results, including serum albumin (ALB) and serum total cholesterol concentrations, white blood cell count, and total lymphocyte count (TLC). If there was more than one set of measurements for a given patient, the earliest set of measurements was used. The prognostic nutritional index (PNI) was calculated as (10 × ALB (g/dL)) + (0.005 × TLC (mm

3)) [

10]. Regarding the controlling nutritional status (CONUT) score [

11], albumin concentrations ≥ 3.5, 3.0–3.49, 2.5–2.99, and < 2.5 g/dL were scored as 0, 2, 4, and 6 points, respectively, total lymphocyte counts ≥ 1600, 1200–1599, 800–1199, and < 800/mm

3 were scored as 0, 1, 2, and 3 points, respectively, and total cholesterol concentrations ≥ 180, 140–179, 100–139, and < 100 mg/ dL were scored as 0, 1, 2, and 3 points, respectively. The CONUT score was then defined as the sum of the above three measurements [

11].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

PNI has previously been stratified according to nutritional significance, with a value ≥ 50 defined as normal, ≥ 45 to 49, ≥ 40 to 44, <, and < 40 considered as mild malnutrition, moderate malnutrition, and severe malnutrition, respectively [

10]. Continuous data are presented as median (range) as appropriate. Continuous variables were analyzed nonparametrically using the Mann–Whitney U test. Correlations between continuous variables were assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficients and linear regression. Perioperative changes in each parameter in both groups were estimated using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s

post hoc test. All numerical data were presented as mean ± standard deviation.

All statistical analyses were performed using EZR version 1.68 (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

The baseline patient characteristics are summarized in

Table 1. There were 99 male and 56 female patients (63.9% vs 36.1%, respectively), with a median age of 72 years (range, 20–87 years), median BMI of 22.7 kg/m

2 (range, 15.8–43.4), median body fat percentage of 27.3% (range, 3.0%–54.0%), and a median SMI of 6.8 kg/m

2 (range, 4.4–9.1). Fifty-five (35.5%) patients had diabetes mellitus. Regarding the patients’ preoperative nutritional indicators, the median serum ALB was 4.0 g/dL (range, 2.4–5.2), median PNI was 47 (range, 30–59), and the median CONUT score was 2 (range, 0–9). In terms of preoperative motor function, the median gait speed was 1.19 m/s (range, 0.52–1.63) and the median mean grip strength was 27.7 kg (range, 13.0–52.0).

Using the AWGS criteria, the 155 patients were divided into two groups according to SMI, with 68 (43.9%) and 87 (56.1%) patients stratified into the S and NS groups, respectively.

3.2. Comparison of Preoperative Statuses in the S and NS Groups

The preoperative conditions of the patients in the two groups are shown in

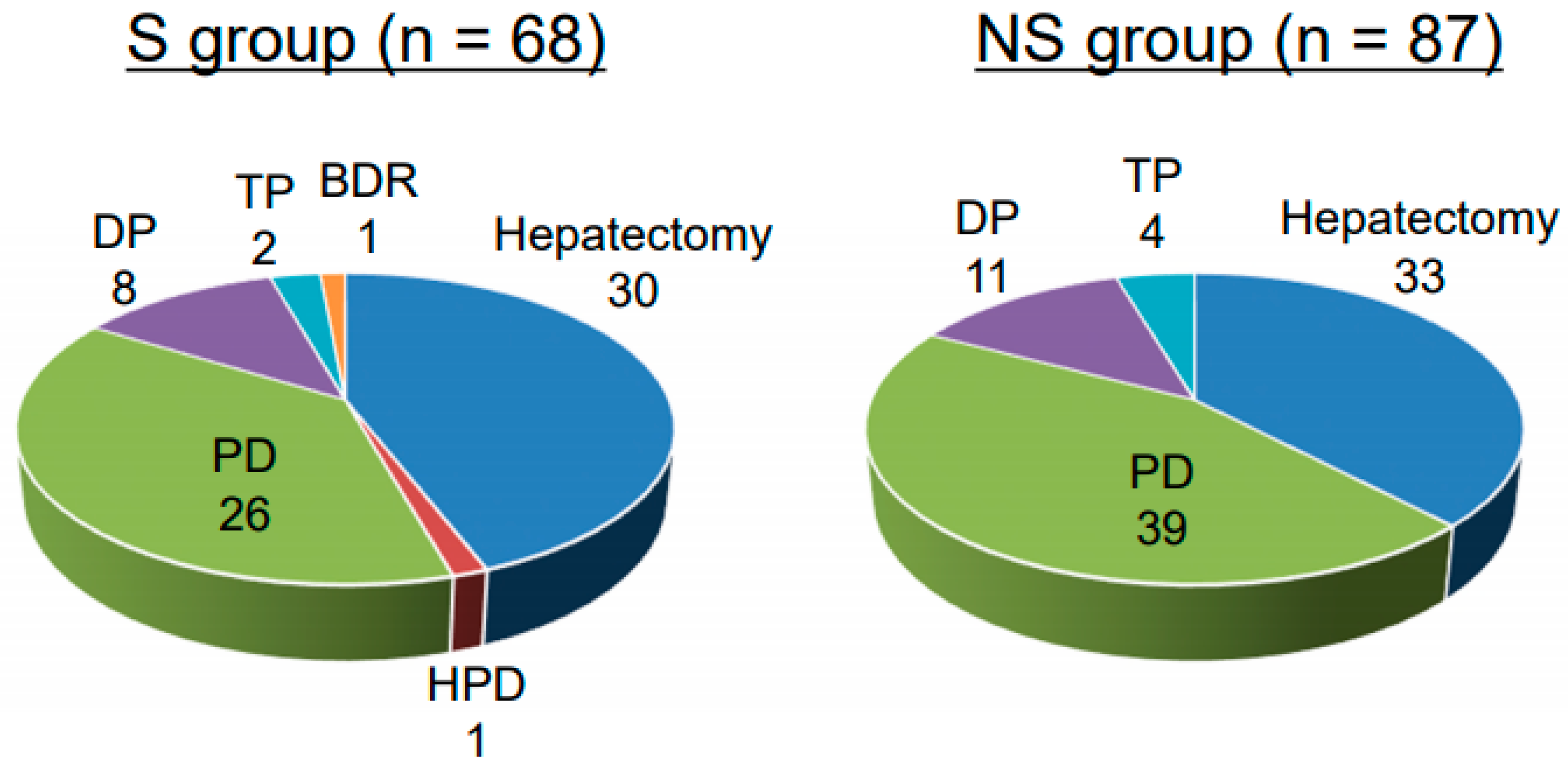

Table 2. There was no significant difference in age between the groups. Patients in the S group had significantly lower BMI, body fat percentage, serum ALB, and mean grip strength compared with the NS group. The incidence of diabetes mellitus and the CONUT score were both significantly higher in the S group than in the NS group. PNI tended to be lower in the S group, suggesting poorer nutritional status, but the difference was not significant. Regarding motor function, the mean grip strength was significantly lower in the S group than in the NS group. Gait speed tended to be slower in the S group, suggesting poorer mobility status, but the difference was not significant. The surgical procedures performed in each patient are shown in

Figure 1. There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of surgical procedures.

3.3. Comparison of Postoperative Statuses in the S and NS Groups

The postoperative conditions of the patients in the two groups are summarized in

Table 3. There were no significant differences between the two groups in the incidence of total postoperative complications, CD grade ≥ IIIa complications, incidence of refractory ascites and PE, postoperative hospital stay, and perioperative mortality. There was no significant difference in serum ALB concentrations at discharge between the two groups. Gait speed and mean grip strength at discharge were significantly lower in the S group than in the NS group.

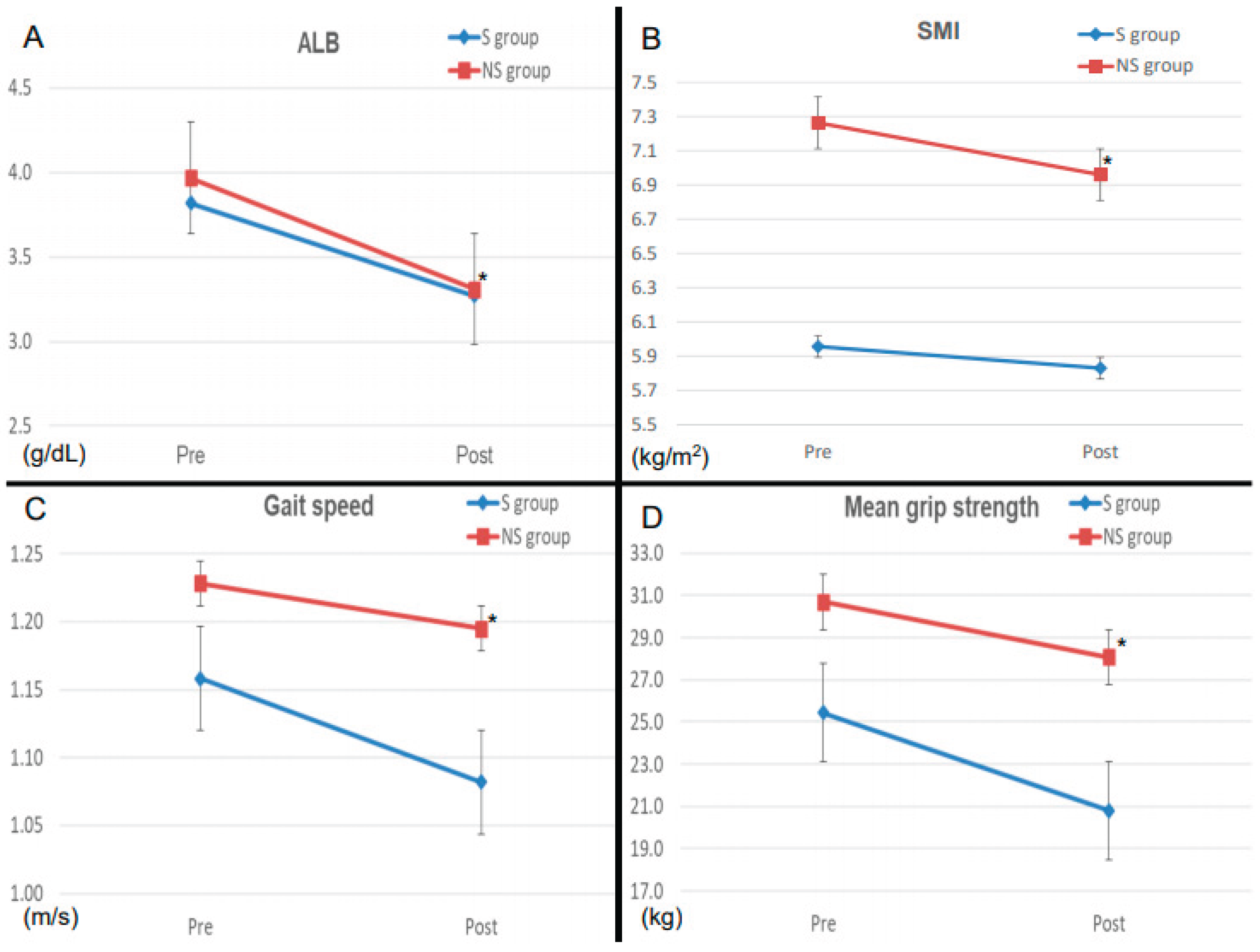

3.4. Perioperative Changes in serum ALB Levels and Motor Function parameters in the Two Groups

We also evaluated the changes in perioperative serum ALB levels and motor functions between the two groups. The perioperative rates of change in serum ALB levels and SMI were significantly higher in the NS group than in the S group (

Figure 2), while the perioperative rates of change for gait speed and mean grip strength were significantly higher in the S group than in the NS group.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrated the effectiveness of perioperative rehabilitation in patients with sarcopenia undergoing major HBP surgery. Previous studies have shown that patients with sarcopenia undergoing HBP surgery have more complications and a worse prognosis than those without sarcopenia [

4,

5,

6]. In addition, preoperative nutritional therapy and prehabilitation are considered important countermeasures; however, the role of exercise therapy, especially postoperative rehabilitation, in improving perioperative outcomes remains unclear.

The current results showed that 43.9% of patients who underwent major HBP surgery in our institution had sarcopenia, and these patients had a higher rate of diabetes mellitus, lower BMI, poorer nutritional status, and poorer mobility than those without sarcopenia. Patients with and without sarcopenia underwent the same surgical procedures, and there was no significant difference in the incidence of perioperative complications, including refractory ascites and PE, perioperative mortality, or hospital stay, although postoperative motor function was predominantly impaired in the sarcopenia group. Regarding changes in serum ALB, SMI, and motor function, serum ALB and SMI were significantly lower in the non-sarcopenia group, while motor function was significantly lower in the sarcopenia group. These results suggest that perioperative rehabilitation suppressed the postoperative decline in serum ALB and SMI in the sarcopenia group, with low nutritional status and motor function, resulting in reductions in perioperative complications, mortality, and hospital stay, to the same extent as in the non-sarcopenia group. Additional nutritional therapy and improved rehabilitation methods may also be necessary to improve motor function, and further investigations are therefore required.

Skeletal muscle accounts for approximately 20% of basal metabolism and approximately 45% of total daily energy expenditure. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor coactivator 1 alpha, which is expressed in skeletal muscle with exercise, induces or inhibits various myokines and has been reported to improve depression, increase appetite, inhibit tumor growth, and prevent skeletal muscle atrophy in cachexia [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Once skeletal muscle mass is reduced, the combination of decreased appetite, decreased food intake, and decreased physical activity leads to a vicious cycle of further reductions in body weight and skeletal muscle mass, resulting in a rapidly decreasing quality of life. Perioperative rehabilitation is therefore considered an important process to maintain skeletal muscle.

Perioperative rehabilitation has been reported to contribute to the reduction of postoperative complications in all areas of gastrointestinal surgery [

16], although most studies have focused on the effects of preoperative rehabilitation [

17]. Although the present study mostly considered postoperative rehabilitation, the postoperative course of the higher-risk sarcopenia group was not inferior to that of the non-sarcopenia group, suggesting that postoperative rehabilitation alone can contribute to an improved postoperative course.

This study focused on the short-term postoperative benefits of perioperative rehabilitation; however, there were some limitations when considering the long-term results. First, whether perioperative rehabilitation contributes to an improved disease prognosis is an important question. Second, it will also be interesting to determine if additional nutritional management can further improve the disease course, as shown in other studies [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Third, the appropriate intensity of rehabilitation used in our department also needs to be examined by follow-up SMI examinations.

5. Conclusions

Perioperative rehabilitation may help to reduce postoperative complications in patients undergoing major HBP surgery. The postoperative course of patients with sarcopenia undergoing HBP surgery with perioperative rehabilitation was not inferior to that of patients without sarcopenia. Perioperative rehabilitation is thus considered useful for avoiding serious postoperative complications and long-term hospitalization in patients with sarcopenia after major HBP surgery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Hiroyuki Takahashi; methodology, Hiroyuki Takahashi; software, Tomoki Takizawa, Shoichiro Mizukami; validation, Hiroyuki Takahashi, Tomoki Takizawa, and Kai Makino; formal analysis, Yuki Adachi; investigation, Koji Imai; re-sources, Hideki Yokoo; data curation, Hiroyuki Takahashi; writing—original draft preparation, Hiroyuki Takahashi; writing—review and editing, Hideki Yokoo; visualization, Hideki Yokoo; supervision, Hideki Yokoo; project administration, Hideki Yokoo; funding acquisition, No. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics and Indications Committee of Asahikawa Medical University (No. 19235).

Informed Consent Statement

The requirement for written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. Information about the study was made publicly available, and patients were given the opportunity to opt out.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. This was a retrospective study using an opt-out approach, and individual patient data cannot be shared publicly.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALB |

albumin |

| AWGS |

Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia |

| BMI |

body mass index |

| CD |

Clavien–Dindo |

| CONUT |

controlling nutritional status |

| HBP |

hepato-biliary-pancreatic |

| JSHBPS |

Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery |

| NS |

non-sarcopenia group |

| PE |

pleural effusion |

| PNI |

prognostic nutritional index |

| S |

sarcopenia group |

| SMI |

skeletal muscle index |

| TLC |

total lymphocyte count |

References

- Otsubo, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Sano, K.; Misawa, T.; Ota, T.; Katagiri, S.; Yanaga, K.; Yamaue, H.; Kokudo, N.; Unno, M.; et al. Safety-related outcomes of the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery board certification system for expert surgeons. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2017, 24, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, K.; Ida, S.; Baba, Y.; Ishimoto, T.; Kosumi, K.; Tokunaga, R.; Izumi, D.; Ohuchi, M.; Nakamura, K.; Kiyozumi, Y.; et al. Prognostic and clinical impact of sarcopenia in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Dis Esophagus 2016, 29, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieffers, J.R.; Bathe, O.F.; Fassbender, K.; Winget, M.; Baracos, V.E. Sarcopenia is associated with postoperative infection and delayed recovery from colorectal cancer resection surgery. Br J Cancer 2012, 107, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okumura, S.; Kaido, T.; Hamaguchi, Y.; Fujimoto, Y.; Masui, T.; Mizumoto, M.; Hammad, A.; Mori, A.; Takaori, K.; Uemoto, S. Impact of preoperative quality as well as quantity of skeletal muscle on survival after resection of pancreatic cancer. Surgery 2015, 157, 1088–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, P.; Hyder, O.; Firoozmand, A.; Kneuertz, P.; Schulick, R.D.; Huang, D.; Makary, M.; Hirose, K.; Edil, B.; Choti, M.A.; et al. Impact of sarcopenia on outcomes following resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg 2012, 16, 1478–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valero, N. 3rd; Amani, N.; Spolverato, G.; Weiss, M.J.; Hirose, K.; Dagher, N.N.; Wolfgang, C.L.; Cameron, A.A.; Philosophe, B.; Kamel, I.R.; et al. Sarcopenia adversely impacts postoperative complications following resection or transplantation in patients with primary liver tumors. J Gastrointest Surg 2015, 19, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.K.; Woo, J.; Assantachai, P.; Auyeung, T.W.; Chou, M.Y.; Iijima, K.; Jang, H.C.; Kang, L.; Kim, M.; Kim, S.; et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update on Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020, 21, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.K.; Liu, L.K.; Woo, J.; Assantachai, P.; Auyeung, T.W.; Bahyah, K.S.; Chou, M.Y.; Chen, L.Y.; Hsu, P.S.; Krairit, O.; et al. Sarcopenia in Asia: consensus report of the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014, 15, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onodera, T.; Goseki, N.; Kosaki, G. [Prognostic nutritional index in gastrointestinal surgery of malnourished cancer patients]. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi 1984, 85, 1001–1005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ignacio de Ulibarri, J.; Gonzalez-Madrono, A.; de Villar, N.G.; Gonzalez, P.; Gonzalez, B.; Mancha, A.; Rodriguez, F.; Fernandez, G. CONUT: a tool for controlling nutritional status. First validation in a hospital population. Nutr Hosp 2005, 20, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Botwinick, I.C.; Pursell, L.; Yu, G.; Cooper, T.; Mann, J.J.; Chabot, J.A. A biological basis for depression in pancreatic cancer. HPB (Oxford) 2014, 16, 740–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agudelo, L.Z.; Femenia, T.; Orhan, F.; Porsmyr-Palmertz, M.; Goiny, M.; Martinez-Redondo, V.; Correia, J.C.; Izadi, M.; Bhat, M.; Schuppe-Koistinen, I.; et al. Skeletal muscle PGC-1a1 modulates kynurenine metabolism and medi.a.;es resilience to stress-induced depression. Cell 2014, 159, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argiles, J.M.; Campos, N.; Lopez-Pedrosa, J.M.; Rueda, R.; Rodriguez-Manas, L. Skeletal muscle regulates metabolism via interorgan crosstalk: Roles in health and disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016, 17, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Song, N.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y. Irisin inhibits pancreatic cancer cell growth via the AMPK-mTOR pathway. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 15247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, H.; Yokoyama, Y.; Inoue, T.; Nagaya, M.; Miuno, Y.; Kadono, I.; Nishiwaki, K.; Nishida, Y.; Nagino, M. Clinical benefit of preoperative exercise and nutritional therapy for patients undergoing hepato-pancreato-biliary surgeries for malignancy. Ann Surg Oncol 2019, 26, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, J.; Guinan, E.; McCormick, P.; Larkin, J.; Mockler, D.; Hussey, J.; Moriarty, J.; Wilson, F. The ability of prehabilitation to influence postoperative outcome after intra-abdominal operation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery 2016, 160, 1189–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, S.T.; Lo, C.M.; Lai, E.C.; Chu, K.M.; Liu, C.L.; Wong, J. Perioperative nutritional support in patients undergoing hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1994, 331, 1542–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirabe, K.; Yoshimatsu, M.; Motomura, T.; Takeishi, K.; Toshima, T.; Muto, J.; Matono, R.; Taketomi, A.; Uchiyama, H.; Maehara, Y. Beneficial effects of supplementation with branched-chain amino acids on postoperative bacteremia in living donor liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl 2011, 17, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, K.; Yokoyama, Y.; Nakajima, H.; Nagino, M.; Inoue, T.; Nagaya, M.; Hattori, K.; Kadono, I.; Ito, S.; Nishida, Y. Preoperative 6-minute walk distance accurately predicts postoperative complications after operations for hepato-pancreato-biliary cancer. Surgery 2017, 161, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, H.; Yokoyama, Y.; Inoue, T.; Nagaya, M.; Mizuno, Y.; Kadono, I.; Nishiwaki, K.; Nishida, Y.; Nagino, M. Clinical benefit of preoperative exercise and nutritional therapy for patients undergoing hepato-pancreato-biliary surgeries for malignancy. Ann Surg Oncol 2019, 26, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).