1. Introduction

Surgical patients tend to experience nutritional status abnormalities due to the underlying pathology that requires hospitalization and the subsequent surgical process. This may lead to post-operative complications, potentially creating a vicious cycle [

1]. The most important factors that significantly contribute to the development of malnutrition in surgical patients include age, pre-existing chronic comorbidities, oncologic conditions, and prolonged peri-operative fasting periods [

2].

There are several critical points during the peri-operative period when a patient’s nutritional status and body composition may be compromised. Both the underlying disease and pre-operative treatment can lead to metabolic disturbances and inflammatory processes that alter body composition. In addition, patients may struggle to meet their nutritional requirements through a regular diet, ultimately facing surgery in a state of nutritional deficiency, which significantly impacts the post-operative period [

3]. A malnourished patient shows changes in body composition, with a marked decline in functional capacity and deterioration in immune and cardiorespiratory function. Various studies have revealed that the consequences of such malnutrition negatively impact patient recovery, leading to higher morbidity and mortality rates, increased hospital stays with a higher rate of readmission, and consequently, greater healthcare costs [

4,

5]. To optimize patients during the pre-operative period and enhance their functional capacity while reducing postoperative complications, it is recommended that they undergo a prehabilitation period. This should include physical improvement, cognitive intervention, smoking weaning, anemia correction, and nutritional assessment and intervention [

5,

6].

From a nutritional perspective, all patients scheduled for major surgery should undergo nutritional screening and a comprehensive assessment, followed by the establishment of a nutritional treatment plan with monitoring of tolerance and adherence. In addition, it is recommended that all patients at nutritional risk or already malnourished receive pre-operative nutritional treatment for at least seven to ten days before surgery [

7]. However, to ensure an appropriate nutritional approach, nutrition should be fully assessed, including a detailed analysis of body composition, particularly muscle mass.

Body composition analysis using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) has proven useful in assessing short- and long-term changes in body composition, nutritional prognosis, and as an indicator of morbidity and mortality risk. Another clinically feasible technique for assessing muscle mass is ultrasound, which provides a detailed analysis of muscle morphology. Specifically, assessing the rectus femoris muscle via ultrasonography could serve as a valuable tool for determining muscle mass in pre-operative patients [

8,

9,

10].

Muscle strength assessment is also crucial. According to the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2), low muscle strength combined with reduced muscle mass confirms a diagnosis of sarcopenia, with the severity determined by impaired muscle performance [

11]. Thus, we infer that analyzing patient muscle mass via ultrasound and assessing muscle strength using dynamometry are required to confirm a diagnosis of sarcopenia in surgical patients. Furthermore, these assessments should be integrated into the routine clinical practice of nutritional assessment in surgical patients.

For this reason, this study was proposed to implement a morphofunctional assessment in patients undergoing surgery. The main aim of this study was to investigate whether a pre-operative assessment and intervention—including nutritional supplementation, physical exercise, and health education—improve body composition, nutritional status, and quality of life in surgical patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

We performed an observational, descriptive, comparative (pre-post), prospective study at the Infanta Cristina University Hospital in Parla (Madrid) in 2022. This study was approved by the H.U. Puerta de Hierro Research and Ethics Committee.

Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before the study commenced, following the provision of an information sheet addressing any potential questions about the study. The collated data remained anonymous, and those involved in data collection took part voluntarily, without compensation or personal interest. The study subjects’ personal data were handled in compliance with prevailing data protection regulations, including Spanish Royal Decree (RD) 1090/2015 and current Spanish legislation (Spanish Organic Law 3/2018, of December 5, on Personal Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights, Spanish Official State Bulletin 294 of 06/12/2018).

All patients included in the study met the following inclusion criteria: aged 18 or older; referred to a prehabilitation surgical consultation; requiring major surgery with hospital admission; capable of making decisions; and physically and mentally competent to undertake the proposed tests. Patients who were unable to eat orally, were referred to another hospital, making data collection difficult, or did not sign the informed consent form were excluded.

2.2. Studied Variables

The following variables were analyzed:

Clinical variables: age (years); sex (male/female); type of pathology (IDC, colorectal, renal adenocarcinoma, endometrial adenocarcinoma); type of procedure (tumorectomy, mastectomy, colon resection, nephrectomy, hysterectomy); oncologic patient (yes/no); neoadjuvant treatment (yes/no).

Anthropometric measurements: weight (kg); height (m); BMI (kg/m²).

Biochemical variables: Albumin (g/dL); prealbumin (mg/dL); proteins (g/dL); total cholesterol (mg/dL); lymphocytes (units/mm³).

Muscle strength (kg): measured using a hand dynamometer (JAMAR dynamometer). Dynamometry was performed with the dominant hand while the patient was seated, with the arm at a right angle to the forearm. Three measurements were taken, and the average value was calculated.

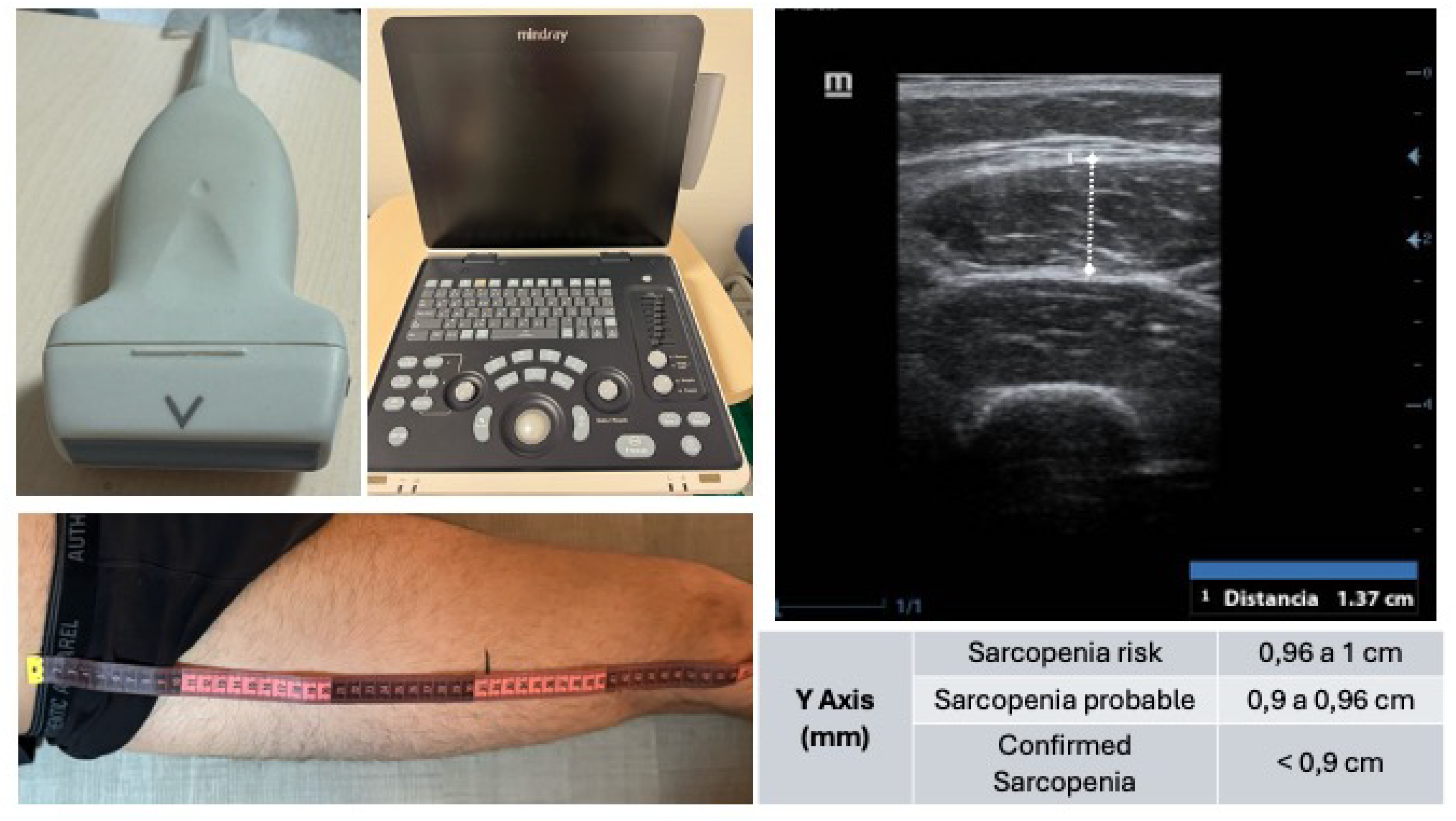

Body composition: Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA) (Beurer BF 1000; Beurer GmbH): Muscle mass and fat mass were estimated using a scale equipped with electrodes for both feet and hands while the patient stood. The BIA provided data on muscle mass (%) and fat mass (%). Muscle ultrasound (Mindray Z60): An ultrasound analysis of the rectus femoris muscle of the quadriceps (QRF) was performed on all patients while in the supine position. The assessment was conducted at the lower third of the thigh (measured from the anterior superior iliac spine to the upper border of the patella) on the dominant leg using a 10–12 MHz linear probe. The probe was aligned perpendicularly to the longitudinal axis of the QRF. Analysis was performed without compression, identifying the QRF by its central tendon, and measuring the anteroposterior thickness of the QRF (Y-axis, cm). The Y-axis index (Y-axis/m²) was also calculated. Visceral adipose tissue ultrasound (Mindray Z60): to assess visceral fat, an ultrasound analysis was performed at the abdominal level with the patient in a supine position, at the midpoint between the xiphoid process and the umbilicus along the midline. Using a transverse probe position, the preperitoneal visceral fat compartment was identified between the inner surface of the linea alba and the peritoneal membrane. The anteroposterior thickness of this compartment was measured during unforced expiration (cm). (

Figure 1)

Malnutrition: the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) criteria were used for malnutrition diagnosis.

Functional assessment: the Barthel Index was applied.

Quality of life: the EuroQoL-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire was used.

Complications: postoperative complications were recorded, including general complications (yes/no), infectious complications (yes/no), suture dehiscence (yes/no), surgical wound complications (yes/no), and surgical wound complications at two weeks (yes/no).

2.3. Intervention

All patients attended the prehabilitation consultation and followed its established protocol. The protocol consisted of three visits conducted by an advanced practice nurse. Initial visit: this took place within 48 hours of the surgical interconsultation after the patient was placed on the surgical waiting list (SWL) by the surgeon. During this initial consultation, a comprehensive bio-psychosocial assessment was performed, including nutritional assessment (GLIM criteria, ultrasound, dynamometry, and bioimpedance); psychological evaluation; analysis of laboratory parameters; assessment of comorbidities; functional evaluation (Barthel Index); quality of life assessment (EuroQoL-5D). In addition, analytical and nutritional parameters were reviewed and optimized by means of targeted treatment prior to surgery. Any abnormalities detected were addressed, and the patient was optimized by means of recommendations provided by the advanced practice nurse. These included: disease coping strategies; physical exercise guidelines (individualized exercise plan: at least 150 minutes per week, combining aerobic and strength training); nutritional recommendations (see distribution of food groups); pulmonary capacity strengthening (using an incentive spirometer); medical nutritional therapy (oral nutritional supplementation [ONS], prescribed by the internist associated with the prehabilitation consultation, to be taken for 21 days before surgery and one month after).

The process was optimized for three weeks before surgery and one month postoperatively. Patients received tailored nutritional education and therapy. This included tailored diets and nutritional supplementation with macronutrients and micronutrients, according to expert recommendations. Notably, immunonutrient-enriched diets were not used, as per the available scientific evidence on pre-operative nutritional supplementation.

The supplementation regimen and nutritional recommendations were split into three groups:

Overweight or Sarcopenic Obesity Patient: daily natural diet with a significant increase in protein intake (71 g of protein/day). Supplementation: 2 oral nutritional supplements (ONS) per day, each 250 mL (NUTAVANT HP®). Composition per 100 mL: 6 g of protein (lactoalbumin, sodium caseinate, calcium caseinate), 12 g of carbohydrates, 4 g of fats (

Table A1).

Patient with Mixed Malnutrition: Daily natural diet with a significant increase in caloric and protein intake. Supplementation: two oral nutritional supplements (ONS) a day, each 250 mL (NUTAVANT PLUS®): supplementation per 100 mL provided 8.9 g of protein (lactoalbumin, sodium caseinate, calcium caseinate), 16.9 g of carbohydrates, and 6.5 g of fats (

Table A2).

Patients with malnutrition and abnormal carbohydrate metabolism followed a daily natural diet adapted with low glycemic index carbohydrates, increased fat intake (mainly foods rich in monounsaturated fatty acids), and higher fiber intake. They were supplemented with two diabetes-specific oral nutritional supplements (ONS) a day, each 250 mL (NUTAVANT PLUS DIABETICA®). Each 100 mL of the supplement provided 6.6 g of protein (lactoalbumin, sodium caseinate, calcium caseinate), 12 g of carbohydrates, 4.6 g of fats (of which 2.3 g were monounsaturated), and 1.8 g of soluble fiber (

Table A3).

The second visit took place the day before surgery to assess the patient’s recovery after the optimization process, performing the same evaluations as in the initial visit. The third visit was undertaken one month after surgery to ensure that quality of life and functional capacity had not declined and to verify that the patient’s nutritional status remained optimal.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v27 software package (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). A descriptive analysis was conducted for all study variables to examine their distribution. Categorical variables were reported using percentages for each response option. Quantitative variables were presented as mean and standard deviation. For comparisons between variables and hypothesis testing, the following statistical tests were used: Chi-square test for categorical variables; student t-test for quantitative variables.

3. Results

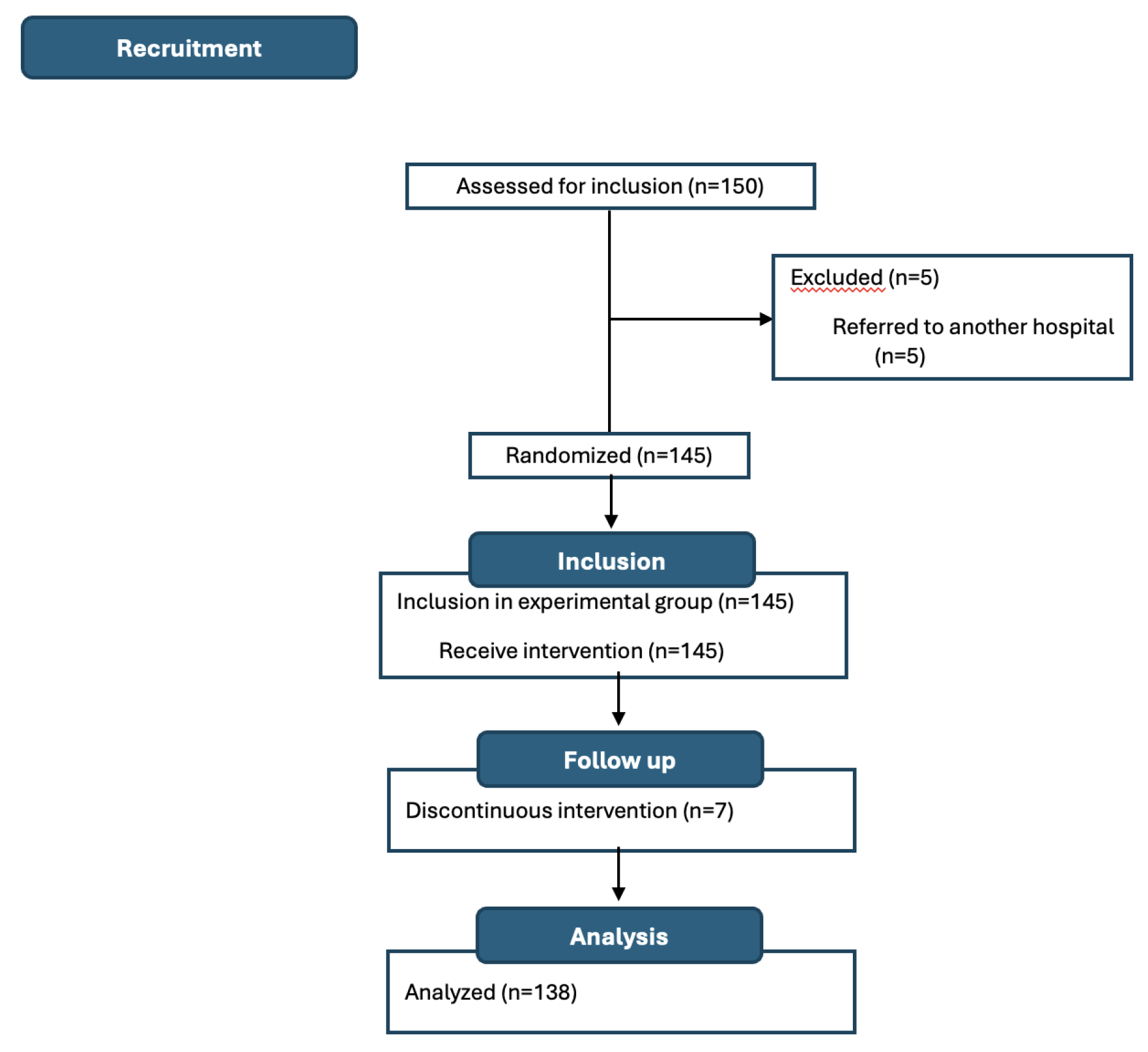

A total of 150 patients were recruited, of whom 138 (92.0%) were analyzed (

Figure 2). Most patients were women (n=84, 60.9%) with a mean age (SD) of 61.69 (13.22) years. The most common surgical procedure was colon resection (n=49, 35.7%), followed by mastectomy and hysterectomy (n=28, 20.5% each), nephrectomy (n=18, 13.2%), and lumpectomy (n=15, 10.1%). Most patients were oncology cases (n=104, 75.3%), and only 27.0% (n=37) received neoadjuvant therapy (

Table A4).

According to GLIM criteria, 81 patients (64.8%) had malnutrition before prehabilitation, with severe malnutrition in 49 (39.2%) of them. After optimization, this number decreased to 42 patients (31.8%), and one month after surgery, only 35 patients (26.7%) met the criteria for malnutrition (

Table A4).

The Y-axis values of the QRF before optimization were 1.16 ± 0.32 cm (p<0.001) (

Table A5), increasing to 1.40 ± 0.33 cm after treatment and 1.37 ± 0.31 cm one month after surgery (p<0.001) (

Table A6).

Similarly, the percentage of muscle mass before treatment was 33.54 ± 6.60%, increasing to 36.33 ± 6.45% after optimization (p=0.001) (

Table A5) and to 36.69 ± 6.63% one month after surgery (p<0.001) (

Table A6).

Muscle strength, measured by dynamometry, was 24.06 ± 9.30 kg, increasing to 26.91 ± 9.76 kg after optimization (p=0.014) (

Table A5) and to 27.21 ± 9.59 kg one month after surgery (p=0.007) (

Table A6).

The preperitoneal abdominal visceral fat, measured by ultrasound, decreased from 0.68 ± 0.32 cm before optimization to 0.55 ± 0.24 cm after optimization (p<0.001)(

Table A5) and further to 0.50 ± 0.21 cm one month later (p<0.001) (

Table A6).

Of the total patients, only 14.2% (n=19) underwent postoperative complications, of which 6.0% (n=8) were infectious. In regard to surgical wound complications at two weeks, only 2.3% (n=3) showed abnormalities (

Table A4).

The supplementation regimen was prescribed based on type of malnutrition present and the daily intake requirements calculated. Most patients were prescribed two bottles of oral nutritional supplements (ONS) per day. Compliance with the prescribed ONS was high (n=121, 87.6%) (

Table A4). Only 8.69% consumed one bottle per day, while 3.6% did not take any. At the first prehabilitation consultation, 71.0% of patients engaged in physical exercise. This increased to 94.2% after optimization (p<0.001) (

Table A5).

In regard to quality of life and functionality, patients maintained similar scores across the three visits (

Table A4 and

Table A7). No significant reduction in functionality was observed during the peri-operative period, nor were there statistically significant differences between visits (

Table A5 and

Table A6). The scores in the different dimensions of the EuroQoL 5D test improved at the second visit, after prehabilitation, with no abnormalities observed in the categories one month after surgery in any patient (

Table A7).

In regard to biochemical variables, patients maintained similar levels across the three visits (

Table A4). However, statistically significant differences were observed in albumin levels between the first visit and the visit one month after surgery (4.01 ± 1.95 g/dL vs. 3.45 ± 0.07 g/dL; p=0.002) (

Table A6). In regard to the postoperative period, only 19 patients (14.2%) underwent complications, most of which were infectious (eight patients). It can be observed that patients who had complications had a lower percentage of muscle mass, a higher percentage of fat mass, a smaller Y-axis thickness of the QRF, a greater thickness of preperitoneal visceral fat, and lower muscle strength (

Table A8).

4. Discussion

This study reports the health outcomes of patients who underwent major elective surgery after taking part in a pre-operative optimization program led by an advanced practice nurse in collaboration with an internist associated with the project. The outcomes compared were those obtained at the time the patient was included in the SWL, after optimization, and during the month of surgery. In addition, post-operative complications were compared between patients treated in 2019—before the implementation of the surgical prehabilitation consultation (data obtained from a prior study at the hospital)—and those who underwent optimization (

Table A9).

Programs involving multiple professionals can be ineffective due to delays in patient treatment and incorrect referrals [

12]. The model used here requires only two healthcare professionals. Other models involve multiple specialists (such as hematologists, endocrinologists, cardiologists, pulmonologists, and physiotherapists) and require an average of five visits per patient [

7]. In the protocol implemented at the Infanta Cristina University Hospital in Parla (Madrid), as reported in this paper, patient assessment, management, and care coordination are overseen by the advanced practice nurse in collaboration with the internist associated with the program. This enables the optimization process to commence within 48 hours of adding the patient to the protocol. Empowering a nurse to take on roles traditionally performed by other physicians streamlines access to therapies and simplifies the treatment of complex patients [

13].

Disease-related malnutrition (DRM) is associated with an imbalance between the patient’s intake and their energy and protein requirements, leading to metabolic and functional changes at the body level. There are multiple limitations to traditional nutritional assessment parameters, such as body mass index, weight loss, or traditional analytical parameters like albumin or lymphocytes. Therefore, we propose a new approach to nutritional assessment and management, focusing on the patient’s morphofunctional evaluation, assessing changes in body composition and function with new parameters using techniques such as bioimpedance, ultrasound, dynamometry, and functional tests [

10].

A systematic review of patients aged over 65 states that combining nutritional supplementation with physical exercise improves muscle strength, promotes mobility, and prevents sarcopenia. It also emphasizes that supplementation should be accompanied by individualized dietary guidelines [

14]. This study draws the same conclusions as the cited systematic review, highlighting that our study population included all age groups, not just patients aged over 65. As reflected in the review, our study attained improvements in muscle strength measured by dynamometry (an increase of 2.85 kg), improvements in the Y-axis of the RF measured by ultrasound (an increase of 0.24 cm), an increase in muscle mass measured by bioimpedance (an improvement of 2.79%), a reduction in preperitoneal visceral fat tissue measured by abdominal ultrasound (a reduction of 0.13 cm), and nutritional assessment improvements based on GLIM criteria (64.8% of patients were malnourished before prehabilitation vs. 26.7% one month after intervention). This was attained by implementing optimization strategies (ONS, tailored diet, personalized exercise, correction of comorbidity disorders, and treatment adjustments) before surgery (

Table A6).

Furthermore, this study included an assessment of patient functionality using the Barthel Index and quality of life using the EuroQol-5 dimensions scale. These measurements confirmed that the level of independence in activities of daily living and patients’ quality of life remained intact thanks to the optimization process (as reported in the sample, patients already showed good quality of life and independence, which remained unchanged one month after surgery) (

Table A6).

Moreover, significant improvements were observed in the values recorded before the intervention and after optimization, compared to those obtained one month after surgery (a period during which patients continued following the given recommendations). These results indicate that improvements in body composition and nutritional status were not diminished post-surgery and even improved in some parameters (

Table A6). Among the small number of patients who underwent complications, it was observed that they had lower muscle mass, higher preperitoneal visceral fat tissue, and lower muscle strength (

Table A8). It is worth noting that the reduction in complications was clearly linked to the individualized optimization process, as revealed in the study. Our study population had an average BMI of 28.54, which led to the optimization of these patients with a tailored 1500-calorie diet along with standard optimization. The positive impact of these measures is reflected in the reduction of fat following the prescribed treatment (an average decrease of 2.42% in fat mass, as measured by bioimpedance). This reduction in fat facilitates surgical intervention and decreases complications (

Table A5).

Furthermore, adherence to treatment, supplementation (high adherence of 87.6%, measured using a home nutritional adherence test), and physical exercise (71% of our patients did not exercise before optimization, while 94.2% did after) was attained by means of personalized telephone follow-ups, conducted from the first day of optimization.

In addition, this study collated data from a previous study involving patients who underwent surgery without the benefit of the prehabilitation consultation, as it had not yet been implemented. Postoperative complications were compared between patients who underwent surgery in 2019 (who did not have access to prehabilitation consultation, n=76) and patients in this study who did (n=138). The complication rate for patients who did not receive prehabilitation was 52.6% (n=40), compared to 14.2% (n=19) for those who did (p<0.001). Regarding wound dehiscence, complications occurred in 21.1% (n=16) of non-optimized patients versus 3% (n=4) (p=0.005). The length of hospital stay for patients who did not have access to prehabilitation was 11.63 ± 10.63 days, compared to 8.34 ± 6.70 days for those who did attend consultation (p=0.004) (

Table A9). The results obtained in this study reveal that pre-operative optimization significantly reduces the frequency of immediate and long-term postoperative complications (p<0.001). This is consistent with another clinical study on patients undergoing major abdominal surgery, in which the postoperative complication rate was 31% following preoperative optimization and 62% in the control group without optimization [

15]. In regard to suture dehiscence, it was less common among participants in the program than in the control group. This finding aligns with a meta-analysis published in 2021, which revealed that improving nutritional status reduces the incidence of suture dehiscence by 29% [

16]. In addition, hyperproteic and hypercaloric oral supplementation with added vitamin D may also be associated with a reduction in postoperative complications [

17]. This aligns with the conclusions of Perry et al. (2021), who performed a meta-analysis of 10 clinical studies involving 643 patients [

16]. Their analysis found that postoperative complications decreased in the group receiving whey protein supplementation (22%) compared to the control group (32%) (p=0.001) [

18]. Therefore, it can be concluded that administering hyperproteic ONS improves muscle mass recovery and muscle trophism, which are essential for early mobilization of patients post-surgery.

Several meta-analyses present varying conclusions regarding the reduction in hospital stay duration for patients taking part in pre-operative optimization programs. One such analysis of nine randomized clinical trials did not observe differences between patients who participated in a preoperative optimization program and those who did not [

19]. However, Lambert et al. (2021) reported in their study a reduction of an average of 1.78 days in hospital stays for patients who participated in pre-operative optimization programs compared to those who did not. These results are consistent with those obtained in this study, where hospital admission in the intervention group was reduced by an average of 3.29 days compared to the control group. The outcomes of this research should be interpreted within the context of its limitations, which are typical of the study design. The level of motivation of a patient who voluntarily takes part in research may differ significantly from that of other patients. In regard to the comparison between patients who benefited from prehabilitation and those who did not, patients who received treatment in the consultation may have had different motivations for following the medical recommendations for pre-operative optimization compared to those in the control group.

Despite its limitations, the study presents favorable results obtained through the implementation of a pre-operative optimization program led by a liaison nurse, aimed at reducing the number of postoperative complications and shortening hospitalization time following major elective surgery, as well as improving muscle mass. The results are consistent with those of other studies on similar interventions.

Although these designs have low internal validity, their external validity is high because they reflect routine clinical practice and the value of interventions that can be performed in this context.

5. Conclusions

This reports a pre-surgical optimization program led by a liaison nurse, which included nutritional supplementation, following standard clinical practice, and a physical exercise program aimed at enhancing pulmonary capacity. In addition, psychological and emotional support was provided to reduce pre-surgical stress.

These combined measures contributed to the recovery and improvement of muscle strength, muscle mass, and the nutritional status of surgical patients. They also reduced the rate of complications and readmissions, as well as the length of hospital stay for these patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M. and F.G.; methodology, N.M.; software, F.R.; validation, N.M, F.G. and F.R.; formal analysis, N.M.; investigation, N.M., A.N., V.I., F.G and F.R.; resources, A.N. and V.I.; data curation, N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.; writing—review and editing, N.M. and F.G.; visualization, F.G.; supervision, F.R,, A.N., V.I., N.M. and F.G.; project administration, F.G.; funding acquisition, N.M and F.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

PERSAN FARMA funded the medical writing and editorial support, as well as the article processing fees.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Instituto de Investigación Biomédica Segovia - Arana of Puerta de Hierro University Hospital (protocol code CI 22/22 of 20th of february at 2022)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the patients who took part in the study, Mr. Jason Willis-Lee (Medical Writer) and PERSAN FARMA for supporting the publication of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The founders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BIA |

Bioelectrical impedance analysis |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| DRM |

Disease-related malnutrition |

| IDC |

Invasive ductal carcinoma |

| GLIM |

Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition |

| ONS |

Oral nutrition supplements |

| QRF |

Quadriceps rectus femoris |

| SWL |

Surgical Waiting list |

Appendix A Tables

Table A1.

Nutritional information of NUTAVANT HP

Table A1.

Nutritional information of NUTAVANT HP

| NUTAVANT HP |

per 100 ml |

| Energy (kJ) |

454 |

| Energy (kcal) |

108 |

| Total Fat (g) |

4.0 |

| Saturated Fat (g) |

2.7 |

| Carbohydrates (g) |

12 |

| Sugars (g) |

5.2 |

| Lactose (g) |

0.27 |

| Dietary Fiber (g) |

0 |

| Protein (g) |

6.0 |

| Salt (g) |

0.28 |

Table A2.

Nutritional information of NUTAVANT PLUS

Table A2.

Nutritional information of NUTAVANT PLUS

| NUTAVANT PLUS |

per 100 ml |

| Energy (kJ) |

679 |

| Energy (kcal) |

162 |

| Total Fat (g) |

6.5 |

| Saturated Fat (g) |

1.9 |

| Carbohydrates (g) |

16.9 |

| Sugars (g) |

1.7 |

| Lactose (g) |

0.52 |

| Dietary Fiber (g) |

0 |

| Protein (g) |

8.9 |

| Salt (g) |

0.24 |

Table A3.

Nutritional information of NUTAVANT PLUS DIABETIC

Table A3.

Nutritional information of NUTAVANT PLUS DIABETIC

| NUTAVANT PLUS DIABETIC |

per 100 ml |

| Energy (kJ) |

503 |

| Energy (kcal) |

120 |

| Total Fat (g) |

4.7 |

| Saturated Fat (g) |

1.0 |

| Carbohydrates (g) |

12 |

| Sugars (g) |

2.5 |

| Lactose (g) |

0.28 |

| Dietary Fiber (g) |

1.8 |

| Protein (g) |

6.6 |

| Salt (g) |

0.28 |

Table A4.

Sociodemographic and clinical variables obtained during the initial consultation, the day before surgery, and one month after surgery (standard deviation).

Table A4.

Sociodemographic and clinical variables obtained during the initial consultation, the day before surgery, and one month after surgery (standard deviation).

| |

Before prehabilitation |

Before surgery |

One month from surgery |

| Age (years) |

61.69 (13.22) |

61.69 (13.22) |

61.69 (13.22) |

| BMI (kg/) |

28.54 (5.89) |

28.07 (5.46) |

30.29 (21.93) |

| Albumin (g/dL) |

4.01 (1.95) |

4.11 (2.25) |

3.45 (0.07) |

| Prealbumin (mg/dL) |

24.08 (6.89) |

23.45 (5.21) |

22.4 (5.15) |

| Proteins (mg/dL) |

6.97 (0.51) |

7.01 (0.50) |

5.95 (1.34) |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) |

179.11 (43.84) |

168.98 (37.87) |

|

| Lymphocytes (uni/) |

1770.80 (762.55) |

1672.42 (650.40) |

1833.3 (450.9) |

| Malnutrition (GLIM)(%) |

64.80 |

31.80 |

26.70 |

| Dynamometry (kg) |

24.06 (9.30) |

26.91 (9.76) |

27.21 (9.59) |

| Muscle mass (%) |

33.54 (6.60) |

36.33 (6.45) |

36.69 (6.63) |

| Fat mass (%) |

33.45 (10.23) |

31.03 (9.61) |

30.28 (10.07) |

| Y QRF (cm) |

1.16 (0.32) |

1.40 (0.33) |

1.37 (0.31) |

| Y/ |

0.482 (0.156) |

0.528 (0.174) |

0.525 (0.187) |

| Preperitoneal fat thickness (cm) |

0.68 (0.32) |

0.55 (0.24) |

0.50 (0.21) |

| Barthel index |

96.9 (10.05) |

97.31 (7.94) |

96.98 (8.39) |

| Total complications |

|

|

14.20% |

| Infectious complications |

|

|

6.00% |

| Suture dehiscence |

|

|

3.00% |

| Surgical wound complications |

|

|

2.90% |

| Wound at 2 weeks complications |

|

|

2.30% |

Table A5.

Clinical variables comparing results before treatment and after optimization (standard deviation).

Table A5.

Clinical variables comparing results before treatment and after optimization (standard deviation).

| |

Before prehabilitation |

Before surgery |

p |

| BMI (kg/) |

28.54 (5.89) |

28.07 (5.46) |

0.501 |

| Albumin (g/dL) |

4.01 (1.95) |

4.11 (2.25) |

0.718 |

| Prealbumin (mg/dL) |

24.08 (6.89) |

23.45 (5.21) |

0.418 |

| Proteins (g/dL) |

6.97 (0.51) |

7.01 (0.50) |

0.478 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) |

179.11 (43.84) |

168.98 (37.87) |

0.054 |

| Lymphocytes (uni/) |

1770.80 (762.55) |

1672.42 (650.40) |

0.265 |

| Malnutrition (GLIM)(%) |

64.80 |

31.80 |

<0.001 |

| Dynamometry (kg) |

24.06 (9.30) |

26.91 (9.76) |

0.014 |

| Muscle mass (%) |

33.54 (6.60) |

36.33 (6.45) |

0.001 |

| Fat mass (%) |

33.45 (10.23) |

31.03 (9.61) |

0.047 |

| Y QRF (cm) |

1.16 (0.32) |

1.40 (0.33) |

<0.001 |

| Y/() |

0.482 (0.156) |

0.528 (0.174) |

0.023 |

| Preperitoneal fat thickness (cm) |

0.680 (0.32) |

0.550 (0.24) |

<0.001 |

| Barthel index |

96.90 (10.05) |

97.31 (7.94) |

0.719 |

Table A6.

Clinical variables comparing results before treatment and one month after surgery (standard deviation).

Table A6.

Clinical variables comparing results before treatment and one month after surgery (standard deviation).

| |

Before prehabilitation |

One month from surgery |

p |

| BMI (kg/) |

28.54 (5.89) |

30.29 (21.93) |

0.316 |

| Albumin (g/dL) |

4.01 (1.95) |

3.45 (0.07) |

0.002 |

| Prealbumin (mg/dL) |

24.08 (6.89) |

22.40 (5.15) |

0.808 |

| Proteins (g/dL) |

6.97 (0.51) |

5.95 (1.34) |

0.477 |

| Lymphocytes (uni/) |

1770.80 (762.55) |

1833 (450.90) |

0.888 |

| Malnutrition (GLIM)(%) |

64.80 |

26.70 |

<0.001 |

| Dynamometry (kg) |

24.06 (9.30) |

27.21 (9.59) |

0.007 |

| Muscle mass (%) |

33.54 (6.60) |

36.69 (6.63) |

<0.001 |

| Fat mass (%) |

33.45 (10.23) |

30.28 (10.07) |

0.011 |

| Y QRF (cm) |

1.16 (0.32) |

1.37 (0.31) |

<0.001 |

| Y/() |

0.482 (0.156) |

0.525 (0.187) |

0.039 |

| Preperitoneal fat thickness (cm) |

0.680 (0.32) |

0.500 (0.21) |

<0.001 |

| Barthel index |

96.90 (10.05) |

96.98 (8.39) |

0.951 |

Table A7.

Quality of Life performance using the EuroQoL 5D test.

Table A7.

Quality of Life performance using the EuroQoL 5D test.

| |

SWL Inclusion N(%) |

Before surgery N(%) |

One month from surgery N(%) |

| Walking problems |

Nothing |

28 (20.3) |

138 (100) |

138 (100) |

| |

Same |

110 (79.9) |

0 |

0 |

| |

A lot |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Personal care problems |

Nothing |

138 (100) |

138 (100) |

138 (100) |

| |

Same |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| |

A lot |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Daily activity problems |

Nothing |

0 |

138 (100) |

138 (100) |

| |

Same |

111 (80.40) |

0 |

0 |

| |

A lot |

27 (19.60) |

0 |

0 |

| Pain |

Nothing |

0 |

111 (80.40) |

138 (100) |

| |

Same |

83 (60.10) |

27 (19.60) |

0 |

| |

A lot |

55 (39.90) |

0 |

0 |

| Anxity or depression |

Nothing |

28 (20.30) |

138 (100) |

138 (100) |

| |

Same |

110 (79.70) |

0 |

0 |

| |

A lot |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Table A8.

Clinical variables comparing the results of patients who had post-operative complications with those who did not (standard deviation)

Table A8.

Clinical variables comparing the results of patients who had post-operative complications with those who did not (standard deviation)

| |

Complications |

No complications |

| BMI (kg/) |

26.19 (5.5) |

25.14 (3.4) |

| Dynamometry (kg) |

26.83 (9.48) |

29.72 (10.45) |

| Muscle mass (%) |

36.10 (6.6) |

39.82 (5.57) |

| Fat mass (%) |

31.50(9.9) |

22.25 (8.0) |

| Y QRF (cm) |

1.27 (0.27) |

1.38 (0.32) |

| Preperitoneal fat thickness (cm) |

0.60 (0.36) |

0.50 (0.20) |

| Barthel index |

96.25 (9.39) |

97.20 (7.90) |

Table A9.

Clinical variables comparing patients who did not undergo pre-surgical prehabilitation with those who did benefit from the program)

Table A9.

Clinical variables comparing patients who did not undergo pre-surgical prehabilitation with those who did benefit from the program)

| |

Control (n=76) |

Study (n=138) |

Total (n=214) |

p |

| Complications n (%) |

Yes |

40 (52.60%) |

19 (14.20%) |

59 (27.60%) |

<0.001 |

| |

No |

36 (47.40%) |

119 (85.80%) |

155 (72.40%) |

|

| Suture deshicense n (%) |

Yes |

16 (21.10%) |

4 (3.00%) |

20 (9.30%) |

0.005 |

| |

No |

60 (78.90%) |

134 (97.00%) |

194 (90.70%) |

|

| Blood requierements n (%) |

Yes |

19 (25%) |

13 (9.90%) |

32 (15.50%) |

0.014 |

| |

No |

57 (75.00%) |

122 (90.10%) |

179 (84.5%) |

|

| Days hospital stay (SD) |

|

11.63 (10.63) |

8.34 (6.70) |

9.50 (8.40) |

0.004 |

References

- Lobo, D.N.; Gianotti, L.; Adiamah, A.; Barazzoni, R.; Deutz, N.E.; Dhatariya, K.; Greenhaff, P.L.; Hiesmayr, M.; Hjort Jakobsen, D.; Klek, S.; et al. Perioperative nutrition: Recommendations from the ESPEN expert group. 39, 3211–3227. [CrossRef]

- Verdú-Fernández, M.A.; Soria Aledo, V.; Campillo-Soto, A.; Pérez-Guarinos, C.V.; Carrillo-Alcaraz, A.; Aguayo-Albasini, J.L. Factores nutricionales relacionados con las complicaciones en cirugía mayor abdominopélvica. [CrossRef]

- Gillis, C.; Wischmeyer, P.E. Pre-operative nutrition and the elective surgical patient: why, how and what? 74, 27–35. [CrossRef]

- De luis, D.; Culebras, J.M.; Aller, R.; Eiros-Bouza, J.M. Surgical infection and malnutrition. pp. 509–513. [CrossRef]

- Durrand, J.; Singh, S.J.; Danjoux, G. Prehabilitation 2019. [CrossRef]

- López Rodríguez-Arias, F.; Sánchez-Guillén, L.; Armañanzas Ruiz, L.I.; Díaz Lara, C.; Lacueva Gómez, F.J.; Balagué Pons, C.; Ramírez Rodríguez, J.M.; Arroyo, A. A Narrative Review About Prehabilitation in Surgery: Current Situation and Future Perspectives. 98, 178–186. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Rodriguez, J.; Ruiz-Lopez, P.M.; et al.. VIA RICA de recuperación intensificada en la cirugía del adulto.

- García Almeida, J.M.; García García, C.; Bellido Castañeda, V.; Bellido Guerrero, D. Nuevo enfoque de la nutrición. Valoración del estado nutricional del paciente: función y composición corporal. 35. [CrossRef]

- Mourtzakis, M.; Parry, S.; Connolly, B.; Puthucheary, Z. Skeletal Muscle Ultrasound in Critical Care: A Tool in Need of Translation. 14, 1495–1503. [CrossRef]

- García Almeida, J.M.; García García, C.; Vegas Aguilar, I.M.; Bellido Castañeda, V.; Bellido Guerrero, D. Morphofunctional assessment of patient nutritional status: a global approach. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. 48, 16–31. [CrossRef]

- Whiteman, A.; Dhesi, J.; Walker, D. The high-risk surgical patient: a role for a multi-disciplinary team approach? 116, 311–314. [CrossRef]

- Carey, N.; Stenner, K.; Courtenay, M. An exploration of how nurse prescribing is being used for patients with respiratory conditions across the east of England. 14, 27. [CrossRef]

- Andrea Vásquez-Morales, C.W.B.y.J.S.V. EJERCICIO FÍSICO Y SUPLEMENTOS NUTRICIONALES; EFECTOS DE SU USO. pp. 1077–1084. [CrossRef]

- Barberan-Garcia, A.; Ubré, M.; Roca, J.; Lacy, A.M.; Burgos, F.; Risco, R.; Momblán, D.; Balust, J.; Blanco, I.; Martínez-Pallí, G. Personalised Prehabilitation in High-risk Patients Undergoing Elective Major Abdominal Surgery: A Randomized Blinded Controlled Trial. 267, 50–56. [CrossRef]

- Perry, R.; Herbert, G.; Atkinson, C.; England, C.; Northstone, K.; Baos, S.; Brush, T.; Chong, A.; Ness, A.; Harris, J.; et al. Pre-admission interventions (prehabilitation) to improve outcome after major elective surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 11, e050806. [CrossRef]

- Lawson, C.; Ferreira, V.; Carli, F.; Chevalier, S. Effects of multimodal prehabilitation on muscle size, myosteatosis, and dietary intake of surgical patients with lung cancer — a randomized feasibility study. 46, 1407–1416. Publisher: NRC Research Press. [CrossRef]

- Mertz, K.H.; Reitelseder, S.; Bechshoeft, R.; Bulow, J.; Højfeldt, G.; Jensen, M.; Schacht, S.R.; Lind, M.V.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Mikkelsen, U.R.; et al. The effect of daily protein supplementation, with or without resistance training for 1 year, on muscle size, strength, and function in healthy older adults: A randomized controlled trial. 113, 790–800. [CrossRef]

- Pang, N.Q.; Tan, Y.X.; Samuel, M.; Tan, K.K.; Bonney, G.K.; Yi, H.; Kow, W.C.A. Multimodal prehabilitation in older adults before major abdominal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 407, 2193–2204. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).