Submitted:

07 November 2024

Posted:

11 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

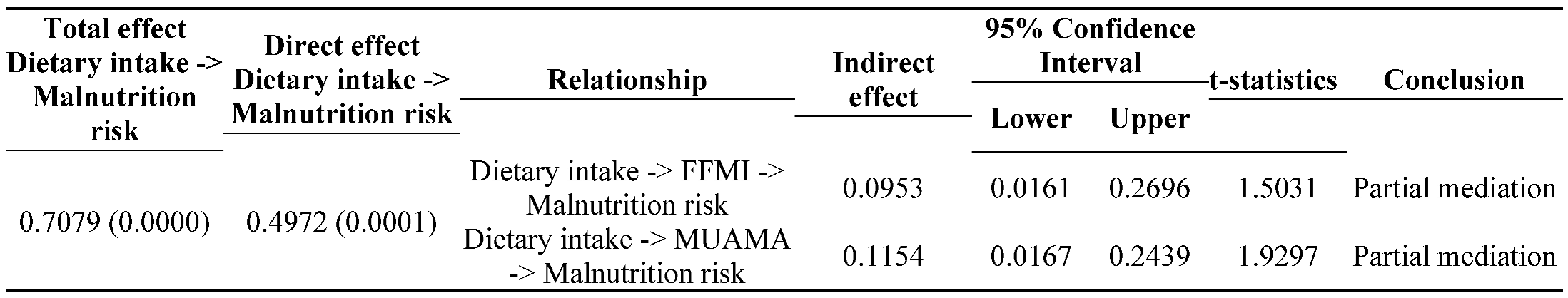

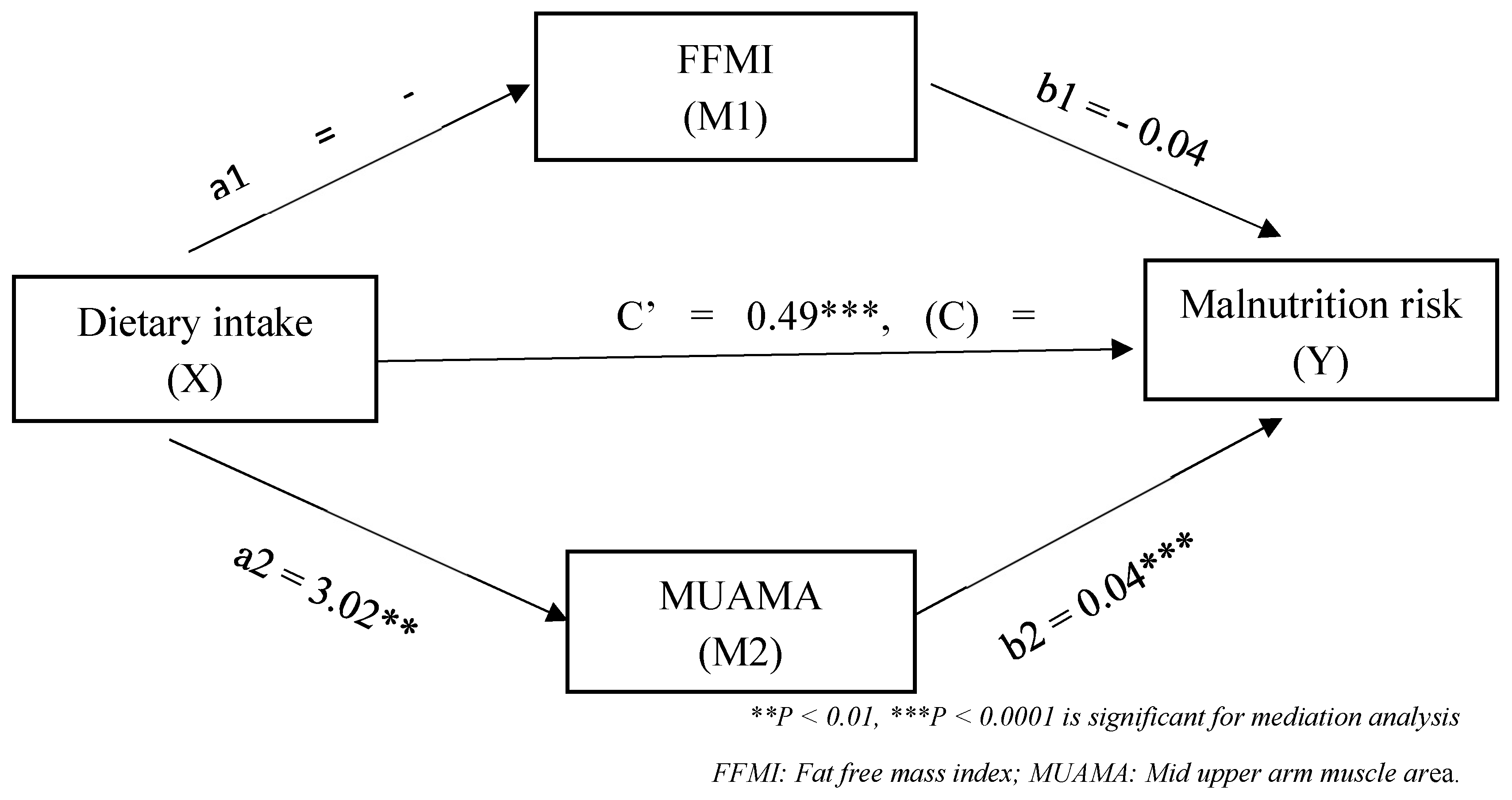

Objectives: This study aims to assess malnutrition and muscle mass depletion risk in gastrointestinal cancer patients, exploring differences between gastric and colorectal cancer, with a focus on gender-specific variations and dietary intake. It also examines whether muscle depletion mediates the relationship between dietary intake and malnutrition risk. Methods: 100 Jordanian pre-operative gastrointestinal cancer patients (60 male, 40 female) with gastric or colorectal cancer were assessed for malnutrition risk using the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) and for muscle depletion using fat-free mass index (FFMI) and mid-upper arm muscle area (MUAMA). Results: the study found that 80% (95% CI: 0.708 - 0.873 ) of patients were at high risk for malnutrition, with over 60% experiencing severe muscle loss. Gastric cancer patients had a higher, though not statistically significant, malnutrition risk (90.2% vs. 72.9%) and muscle depletion compared to colorectal cancer patients. Significant gender-specific differences in muscle depletion via FFMI (P = 0.012) and via MUAMA (P = 0.028) were also noted, especially in females with gastric cancer. Patients' dietary intake was significantly (P < 0.001) below recommended levels for energy, protein, carbohydrates, fiber, and essential fatty acids, which was associated with higher malnutrition risk, muscle depletion, low BMI (<18.5 kg/m²), and significant weight loss (>10%). Low dietary intake was strongly linked to increased malnutrition risk and muscle depletion, with muscle loss partially mediating (b = 0.4972, P < 0.0001) the relationship between poor dietary intake and malnutrition risk. Additionally, higher muscle mass was protective against malnutrition (OR = 16.0, 95% CI: 1.706 – 150.507), and cancer type was a significant predictor of malnutrition risk (OR = 14.4, 95% CI: 1.583 – 130.867). Conclusions: Malnutrition risks and significant muscle loss are common in GI cancer patients, highlighting the urgent need for tailored nutrition care plans and lifestyle modifications.

Keywords:

Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

2.2. Ethical approval

2.3. Anthropometric and muscle depletion

2.4. Malnutrition risk assessment

2.5. Assessment of quality of life

2.6. Assessment of dietary intake

2.7. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. General characteristics of the study subjects

3.2. Malnutrition risk, muscle depletion, adequacy of dietary intake and quality of life scales

| Variable | Type of cancer | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 100) |

Gastric (n=41) |

Colorectal (n= 59) |

||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Sex - Male - Female |

60 (60.0) 40 (40.0) |

23 (56.1) 18 (43.9) |

37 (62.7) 22 (37.3) |

0.323 |

| BMI score (kg/m2) - > 20 - 18.5-20 - < 18.5 |

51 (51.0) 35 (35.0) 14 (14.0) |

17 (41.5) 16 (39.0) 8 (19.5) |

34 (57.6) 19 (32.2) 6 (10.2) |

0.216 |

| Weight loss score (%) - < 5 - 5-10 - > 10 |

9 (9.0) 15 (15.0) 76 (76.0) |

1 (2.4) 5 (12.2) 35 (85.4) |

8 (13.6) 10 (16.9) 41 (69.5) |

0.103 |

| Acute disease score - Zero - One - Two |

46 (46.0) 20 (20.0) 34 (34.0) |

17 (41.5) 8 (19.5) 16 (39.0) |

29 (49.2) 12 (20.3) 18 (30.5) |

0.659 |

| Malnutrition risk - No risk - Medium risk - High risk |

9 (9.0) 11 (11.0) 80 (80.0) |

1 (2.4) 3 (7.3) 37 (90.2) |

8 (13.6) 8 (13.6) 43 (72.9) |

0.093 |

| Muscle depletion for FFMI (kg/m2) - Normal - Depleted MUAMA (Cm2) - Normal - Depleted |

35 (35.0) 65 (65.0) 40 (40.0) 60 (60.0) |

12 (29.3) 29 (70.7) 14 (34.1) 27 (65.9) |

23 (39.0) 36 (61.0) 26 (44.1) 33 (55.9) |

0.216 0.397 |

| Dietary intake - Adequate - Inadequate |

40 (40.0) 60 (60.0) |

13 (31.7) 28 (68.3) |

27 (45.8) 32 (54.2) |

0.114 |

| Health care scale - Good - Bad |

70 (70.0) 30 (30.0) |

27 (65.9) 14 (34.1) |

43 (72.9) 16 (27.1) |

0.296 |

| Functional scale - Good - Bad |

36 (36.0) 64 (64.0) |

16 (39.0) 25 (61.0) |

20 (33.9) 39 (66.1) |

0.376 |

| Symptoms scale - Good - Bad |

32 (32.0) 68 (68.0) |

12 (29.3) 29 (70.7) |

20 (33.9) 39 (66.1) |

0.395 |

| Variable |

Male (n = 60) |

P-value |

Female (n = 40) |

P-value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Type of cancer |

Type of cancer |

|||||

| Gastric (n = 23) n (%) |

Colorectal (n = 37) n (%) |

Gastric (n = 18) n (%) |

Colorectal (n = 22) n (%) |

|||

| BMI score (kg/m2) - > 20 - 18.5-20 - < 18.5 |

11 (47.8) 8 (34.8) 4 (17.4) |

17 (45.9) 14 (37.8) 6 (16.2) |

1.000 |

6 (33.3) 8 (44.4) 4 (22.3) |

17 (77.3) 5 (22.7) 0.5 (0.0)^ |

0.004 |

| Weight loss score (%) - < 5 - 5-10 - > 10 |

1 (4.3) 3 (13.0) 19 (82.6) |

2 (5.4) 5 (13.5) 30 (81.1) |

1.000 |

^0.5 (0.0) 2 (11.1) 16 (88.9) |

6 (27.3) 5 (22.7) 11 (50.0) |

0.016 |

| Acute disease score - Zero - One - Two |

7 (30.4) 4 (17.4) 12 (52.2) |

13 (35.1) 10 (27.0) 14 (37.8) |

0.524 |

10 (55.6) 4 (22.4) 4 (22.4) |

16 (72.7) 2 (22.4) 4 (18.2) |

0.424 |

| Malnutrition risk - No risk - Medium risk - High risk |

1 (4.3) 1 (4.3) 21 (91.4) |

2 (5.4) 5 (13.5) 30 (81.1) |

0.633 |

^0.5 (0.0) 2 (11.1) 16 (88.9) |

6 (27.3) 3 (13.6) 13 (59.1) |

0.039 |

| Muscle depletion for FFMI (kg/m2) - Normal - Depleted |

7 (30.4) 16 (59.6) |

8 (21.6) 29 (78.4) |

0.320 |

5 (27.8) 13 (72.2) |

15 (68.2) 7 (31.8) |

0.012 |

| Muscle depletion for MUAMA (cm2) - Normal - Depleted |

8 (43.8) 15 (65.2) |

11 (29.7) 26 (70.3) |

0.448 |

6 (33.3) 12 (66.7) |

15 (68.2) 7 (31.8) |

0.028 |

| Dietary intake - Adequate - Inadequate |

8 (34.8) 15 (65.2) |

13 (35.1) 24 (64.9) |

0.601 |

5 (27.8) 13 (72.2) |

14 (63.6) 8 (36.4) |

0.025 |

| Health care scale - Good - Bad |

15 (65.2) 8 (34.8) |

26 (70.3) 11 (29.7) |

0.778 |

12 (66.7) 6 (33.3) |

17 (77.3) 5 (22.7) |

0.347 |

| Functional scale - Good - Bad |

7 (30.4) 16 (69.6) |

8 (21.6) 29 (78.4) |

0.320 |

9 (50.0) 9 (50.0) |

12 (54.2) 10 (45.5) |

0.512 |

| Symptoms scale - Good - Bad |

6 (26.1) 17 (73.9) |

9 (24.3) 28 (75.7) |

0.556 |

6 (33.3) 12 (66.7) |

11 (50.0) 11 (50.0) |

0.230 |

3.3. Dietary intake

| Variable | Dietary intake | Male | Female | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adequate (n=40) |

Inadequate (n= 60) |

P | Adequate (n=21) |

Inadequate (n= 39) |

P | Adequate (n=19) |

Inadequate (n= 21) |

P | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Sex - Male - Female |

21 (52.5) 19 (47.5) |

39 (65.0) 21 (35.0) |

0.149 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| BMI score (kg/m2) - > 20 - 18.5-20 - < 18.5 |

39 (97.5) 1 (2.5) ^0.5 (0.0) |

12 (20.0) 34 (56.7) 14 (23.3) |

< 0.001 |

21 (100.0) ^0.5 (0.0) ^0.5 (0.0) |

7 (17.9) 22 (56.4) 10 (25.6) |

< 0.001 |

18 (94.7) 1 (5.3) ^0.5 (0.0) |

5 (23.8) 12 (57.2) 4 (19.0) |

< 0.001 |

| Weight loss score (%) - < 5 - 5-10 - > 10 |

9 (22.5) 15 (37.5) 16 (40.0) |

^0.5 (0.0) ^0.5 (0.0) 60 (100.0) |

< 0.001 |

3 (14.3) 8 (38.1) 10 (47.6) |

^0.5 (0.0) ^0.5 (0.0) 39 (100.0) |

< 0.001 |

6 (31.6) 7 (36.8) 6 (31.6) |

^0.5 (0.0) ^0.5 (0.0) 21 (100.0) |

< 0.001 |

| Acute disease score - Zero - One - Two |

26 (65.0) 8 (20.0) 6 (15.0) |

20 (33.3) 12 (20.0) 28 (46.7) |

0.002 |

13 (61.9) 5 (23.8) 3 (14.3) |

7 (17.9) 9 (23.1) 23 (59.0) |

0.001 |

13 (68.4) 3 (15.8) 3 (15.8) |

13 (61.9) 3 (14.3) 5 (23.8) |

0.897 |

| Malnutrition risk - No risk - Medium risk - High risk |

9 (22.5) 11 (27.5) 20 (50.0) |

^0.5 (0.0) ^0.5 (0.0) 60 (100.0) |

< 0.001 |

3 (14.3) 6 (28.6) 12 (57.1) |

^0.5 (0.0) ^0.5 (0.0) 39 (100.0) |

< 0.001 |

6 (31.6) 5 (26.3) 8 (42.1) |

^0.5 (0.0) ^0.5 (0.0) 21 (100.0) |

< 0.001 |

| Muscle depletion for FFMI (kg/m2) - Normal - Depleted MUAMA (cm2) - Normal - Depleted |

30 (75.0) 10(25.0) 25 (62.5) 15 (37.5) |

5 (8.3) 55 (91.7) 17 (28.3) 43 (71.7) |

< 0.001 0.0007 |

13 (61.9) 8 (38.1) 14 (66.7) 7 (33.3) |

2 (5.1) 37 (94.9) 12 (30.8) 27 (69.2) |

< 0.001 0.007 |

17 (89.5) 2 (10.5) 11 (57.9) 8 (42.1) |

3 (14.3) 18 (85.7) 5 (23.8) 16 (76.2) |

< 0.001 0.028 |

| Type of cancer - Gastric - Colorectal |

13 (32.5) 27 (67.5) |

28 (46.7) 32 (53.3) |

0.114 |

8 (38.1) 13 (61.9) |

15 (38.5) 24 (61.5) |

1.00 |

5 (26.3) 14 (73.7) |

13 (61.9) 8 (38.1) |

0.031 |

| Health care scale - Good - Bad |

32 (80.0) 8 (20.0) |

38 (63.3) 22 (36.7) |

0.058 |

17 (81.0) 4 (19.0) |

24 (61.5) 15 (38.5) |

0.154 |

15 (78.9) 4 (21.1) |

14 (66.7) 7 (33.3) |

0.488 |

| Functional scale - Good - Bad |

23 (57.5) 17 (42.5) |

13 (21.7) 47 (78.3) |

< 0.001 |

10 (47.6) 11 (52.4) |

5 (12.8) 34 (87.2) |

0.005 |

13 (68.4) 6 (31.6) |

8 (38.1) 13 (61.9) |

0.067 |

| Symptoms scale - Good - Bad |

26 (65.0) 14 (35.0) |

6 (10.0) 54 (90.0) |

< 0.001 |

13 (61.9) 8 (38.1) |

2 (5.1) 37 (94.9) |

< 0.001 |

13 (68.4) 6 (31.6) |

4 (19.0) 17 (81.0) |

0.003 |

3.4. Mediation analysis

3.5. Predictors of malnutrition risk

| Variables in the equation | B | S.E. | P-value | OR | 95% C.I. for OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Sex | 2.676 | 1.260 | 0.034 | 14.526 | 1.229 | 171.701 |

| Energy intake (Kcal/day) | -0.007- | 0.003 | 0.020 | 0.993 | 0.987 | 0.999 |

| MUAMA (cm2) | 2.774 | 1.143 | 0.015 | 16.024 | 1.706 | 150.507 |

| Type of cancer | 2.667 | 1.126 | 0.018 | 14.393 | 1.583 | 130.867 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arends, J. Ernährung von Tumorpatienten. Aktuel Ernahrungsmed 2012, 37, 91–106. [CrossRef]

- Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Fearon, K.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S.; Krznaric, Z.; Laird, B.; Larsson, M.; Laviano, A.; Mühlebach, S.; Muscaritoli, M.; Oldervoll, L.; Ravasco, P.; Solheim, T.; Strasser, F.; de van der Schueren, M.; Preiser, J. C. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin Nutr 2017, 36, 11–48. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, K.M.; Loeliger, J.; Nolte, L.; Kelaart, A.; Kiss, N.K. Prevalence of malnutrition and impact on clinical outcomes in cancer services: A comparison of two time points. Clin Nutr 2019, 38, 644-651. [CrossRef]

- Martin., L.; Birdsell, L.; Macdonald, N.; Reiman, T.; Clandinin, M.T.; McCargar, L.J.; Murphy, R.; Ghosh, S.; Sawyer, M. B.; Baracos, V. E. Cancer cachexia in the age of obesity: skeletal muscle depletion is a powerful prognostic factor, independent of body mass index. J Clin Oncol 2013, 31, 1539-1547. [CrossRef]

- Cederholm, T.; Barazzoni, R.; Austin, P.; Ballmer, P.; Biolo, G.; Bischoff, S.C.; Compher, C.; Correia, I.; Higashiguchi, T.; Holst, M.; Jensen, G. L.; Malone, A.; Muscaritoli, M.; Nyulasi, I.; Pirlich, M.; Rothenberg, E.; Schindler, K.; Schneider, S. M.; de van der Schueren, M. A.; Sieber, C.; Valentini, L.; Yu, J.C.; Van Gossum, A.; Singer, P. ESPEN guidelines on definitions and terminology of clinical nutrition. Clin Nutr 2017, 36, 49-64. [CrossRef]

- Deftereos, I.; Djordjevic, A.; Carter, V.M.; McNamara, J.; Yeung, J.M.; Kiss, N. Malnutrition screening tools in gastrointestinal cancer: A systematic review of concurrent validity. Surg Oncol 2021, 38, 101627. [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.J.; Ji, Y.B.; Ma, B.W.; Huang, D.D.; Chen, W.Z.; Pan, Z.Y.; Shen, X.; Zhuang, C. L.; Yu, Z. Comparison of three common nutritional screening tools with the new European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) criteria for malnutrition among patients with geriatric gastrointestinal cancer: a prospective study in China. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019750. [CrossRef]

- Seron-Arbeloa, C.; Labarta-Monzon, L.; Puzo-Foncillas, J.; Mallor-Bonet, T.; Lafita-Lopez, A.; Bueno-Vidales, N.; Montoro-Huguet, M. Malnutrition screening and assessment. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2392. [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Aguilar, R.; Malih, N.; Abbate, M.; Fresneda, S.; Yañez, A.; Bennasar-Veny, M. Validity of nutrition screening tools for risk of malnutrition among hospitalized adult patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr 2024, 43,1094-1116. [CrossRef]

- ager-Wittenaar, H.; Ottery, F.D. Assessing nutritional status in cancer: role of the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2017, 20, 322-329. [CrossRef]

- Gills, C.; Richer, L.; Fenton, T.R.; Gramlich, L.; Keller, H.; Culos- Reed, S.N.; Sajobi, T.T.; Awasthi, R.; Carli, F. Colorectal cancer patients with malnutrition suffer poor physical and mental health before surgery. Surgery 2021, 170, 841-847. [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.Y.; Majid, H.A.; Jamhuri, N.; Ahmad, A.F.; Selvarajoo, T.A. Lower ileostomy output among patients with postoperative colorectal cancer after being supplemented with partially hydrolyzed guar gum: Outcome of a pilot study. Nutrition 2022, 103-104,111758. [CrossRef]

- Lobo, D.N.; Gianotti, L.; Adiamah, A.; Barazzoni, R.; Deutz, N.E.P.; Dhatariya, K.; Greenhaff, P. L.; Hiesmayr, M.; Hjort Jakobsen, D.; Klek, S.; Krznaric, Z.; Ljungqvist, O.; McMillan, D. C.; Rollins, K. E.; Panisic Sekeljic, M.; Skipworth, R. J. E.; Stanga, Z.; Stockley, A.; Stockley, R.; Weimann, A. Perioperative nutrition: Recommendations from the ESPEN expert group. Clin Nutr 2020, 39, 3211-3227. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shahethi, A.H.; Mahdi, F.A.; Al-Shameri, E.A.; Abol Gaith, F.M. Factors associated with malnutrition in hospitalized cancer patients in a National Oncology Center in conflict-affected settings in Sana’a, Yemen: An institution-based cross-sectional study. Cureus 2023, 15, e45411. [CrossRef]

- Bye, A.; Sjøblom, B.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Grønberg, B.H.; Baracos, V.E.; Hjermstad, M.J.; Aass, N.; Bremnes, R. M.; Fløtten, Ø.; Jordhøy, M. Muscle mass and association to quality of life in non-small cell lung cancer patients. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2017, 8, 759-767. [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.C.; Hong, B.Z. High Prevalence of malnutrition and associated factors in newly diagnosed upper gastrointestinal cancer patients: A cross-sectional study. Asian Pac J Cancer Care 2024, 9, 267-275. [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.Y.; Ibrahim, Z.; Abu Zaid, Z.; Mat Daud, Z’.; Md Yusop, N.B. Clinical malnutrition predictive model among gynecologic cancer patients prior to elective operation: A cross-sectional study. Clin Nutr 2021, 40, 4373-4379. [CrossRef]

- Durán Poveda, M.; Suárez-de-la-Rica, A.; Cancer Minchot, E.; Ocón Bretón, J.; Sánchez Pernaute, A.; Rodríguez Caravaca, G.; PREMAS Study Group. The prevalence and impact of nutritional risk and malnutrition in gastrointestinal surgical oncology patients: A prospective, observational, multicenter, and exploratory Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3283. [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.D.; Nieman, D.C. Nutrational Assessment, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, USA, 2010; pp. 170-233.

- Huang, C.X.; Tighiouart, H.; Beddhu, S.; Cheung, A.K.; Dwyer, J.T.; Eknoyan, G.; Beck, G. J.; Levey, A. S.; Sarnak, M. J. Both low muscle mass and low fat are associated with higher all-cause mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 2010, 77, 624–629. [CrossRef]

- Stratton, R.J.; Hackston, A.; Longmore, D.; Dixon, R.; Price, S.; Stroud, M.; King, C.; Elia, M. Malnutrition in hospital outpatients and inpatients: prevalence, concurrent validity and ease of use of the ‘malnutrition universal screening tool’ (‘MUST’) for adults. Br J Nutr 2004, 92, 799-808. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://qol.eortc.org/questionnaire/eortc-qlq-c30/ (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Parsa, N. Environmental factors inducing human cancers. Iran J Public Health 2012, 41, 1-9.

- Ravasco, P. Nutrition in cancer patients. J Clin Med 2019, 8, 1211. [CrossRef]

- Cushen, S.J.; Power, D.G.; Ryan, A.M. Nutrition assessment in oncology. Topics in Clin Nutr 2015, 30, 103-119. [CrossRef]

- Inciong, J. F. B.; Chaudhary, A.; Hsu, H. S.; Joshi, R.; Seo, J. M.; Trung, L. V.; Ungpinitpong, W.; Usman, N. Hospital malnutrition in northeast and southeast Asia: A systematic literature review. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2020, 39, 30-45. [CrossRef]

- Deftereos, I.; Yeung, J.M.C.; Arslan, J.; Carter, V.M.; Isenring, E.; Kiss N. Assessment of nutritional status and nutrition impact symptoms in patients undergoing resection for upper gastrointestinal cancer: Results from the multi-centre NOURISH point prevalence study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3349. [CrossRef]

- Muscaritoli, M.; Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S.; Krznaric, Z.; Laird, B.; Larsson, M.; Laviano, A.; Mühlebach, S.; Oldervoll, L.; Ravasco, P.; Solheim, T. S.; Strasser, F.; de van der Schueren, M.; Preiser, J.C.; Bischoff, S. C. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical nutrition in cancer. Clin Nutr 2021, 40, 2898-2913. [CrossRef]

- Reber, E.; Schönenberger, K.A.; Vasiloglou, M.F.; Stanga, Z. Nutritional risk screening in cancer patients: The first step toward better clinical outcome. Front in Nutr 2021, 8, 603936. [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Cajas-Monson, L.C.; Eisenstein, S.; Parry, L.; Cosman, B.; Ramamoorthy, S. Preoperative malnutrition assessments as predictors of postoperative mortality and morbidity in colorectal cancer: an analysis of ACS-NSQIP. Nutr J 2015, 14, 91. [CrossRef]

- Cereda, E.; Pedrazzoli, P.; Lobascio, F.; Masi, S.; Crotti, S.; Klersy, C.; Turri, A.; Stobäus, N.; Tank, M.; Franz, K.; Cutti, S.; Giaquinto, E.; Filippi, A. R.; Norman, K.; Caccialanza, R. The prognostic impact of BIA-derived fat-free mass index in patients with cancer. Clin Nutr 2021, 40, 3901-3907. [CrossRef]

- Casirati, A.; Vandoni, G.; Della Valle, S.; Greco, G.; Platania, M.; Colatruglio, S.; Lalli, L.; Gavazzi, C. Nutritional status and body composition assessment in patients with a new diagnosis of advanced solid tumour: exploratory comparison of computed tomography and bioelectrical impedance analysis. Clin Nutr 2021, 40, 1268–1273. [CrossRef]

- Mourtzakis, M.; Prado, C.M.M.; Lieffers, J.R.; Reiman, T.; McCargar, L.J.; Baracos, V.E. practical and precise approach to quantification of body composition in cancer patients using computed tomography images acquired during routine care. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2008, 33, 997-1006. [CrossRef]

- Gascón-Ruiz, M.; Casas-Deza, D.; Torres-Ramón, I.; Zapata-García, M.; Alonso, N.; Sesma, A.; Lambea, J.; Álvarez-Alejandro, M.; Quílez, E.; Isla, D.; Arbonés-Mainar, J. M. GLIM vs ESPEN criteria for the diagnosis of early malnutrition in oncological outpatients. Clin Nutr 2021, 40, 3741–3747. [CrossRef]

- Kiss, N.; Prado, C. M.; Daly, R. M.; Denehy, L.; Edbrooke, L.; Baguley, B. J.; Fraser, S. F.; Khosravi, A.; Abbott, G. Low muscle mass, malnutrition, sarcopenia, and associations with survival in adults with cancer in the UK Biobank cohort. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 1775-1788. [CrossRef]

- Abaza, H.; Taqash, A.; Shattal, M.A.; Abuhijla, F.; Abdel-Khaleq, H.; Awadallah, O.; Al-Jafari, K.; Al-Jafari, Z.; Al-Omari, A. Association between muscle mass and overall survival among colorectal cancer patients at tertiary cancer center in the Middle East. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 20836. [CrossRef]

- Cencioni, C.; Trestini, I.; Piro, G.; Bria, E.; Tortora, G.; Carbone, C.; Spallotta, F. Gastrointestinal cancer patient nutritional management: From specific needs to novel epigenetic dietary approaches. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1542. [CrossRef]

- Kubota, T.; Shoda, K.; Konishi, H.; Okamoto, K.; Otsuji, E. Nutrition update in gastric cancer surgery. Ann Gastroenterol Surg 2020, 4, 360-368. [CrossRef]

- Wischmeyer, P. E.; Carli, F.; Evans, D. C.; Guilbert, S.; Kozar, R.; Pryor, A.; Thiele, R. H.; Everett, S.; Grocott, M.; Gan, T. J.; Shaw, A. D.; Thacker, J. K. M.; Miller, T. E.; Hedrick, T. L.; McEvoy, M. D.; Mythen, M. G.; Bergamaschi, R.; Gupta, R.; Holubar, S. D.; Senagore, A. J.; Abola, R. E.; Bennett-Guerrero, E.; Kent, M.L.; Feldman, L.S.; Fiore Jr, J.F.; Perioperative Quality Initiative (POQI) 2 Workgroup. American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality Initiative Joint Consensus Statement on Nutrition Screening and Therapy Within a Surgical Enhanced Recovery Pathway. Anesth Analg 2018, 126, 1883-1895. [CrossRef]

| Macronutrients | Intake Mean ± SD |

RDA Mean ± SD |

P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total energy (Kcal) | 1574.8 ± 655.8 | 1796.0 ± 251.4* | < 0.001 |

| Protein (g) | 96.8 ± 36.4 | 119.7 ± 16.8^ | < 0.001 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 167.0 ± 96.3 | 100.0 ± 0.0 | < 0.001 |

| Fat (g) | 57.8 ±17.1 | 55.0 ± 0.0 | 0.108 |

| Fiber (g) | 26.9 ±7.2 | 30.0 ±0.0 | < 0.001 |

| Omega 3 and 6 (g) | 1.9 ± 2.3 | 0.25 ± 0.0 | < 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).