Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

18 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials, Methods and Datasets

3. Results

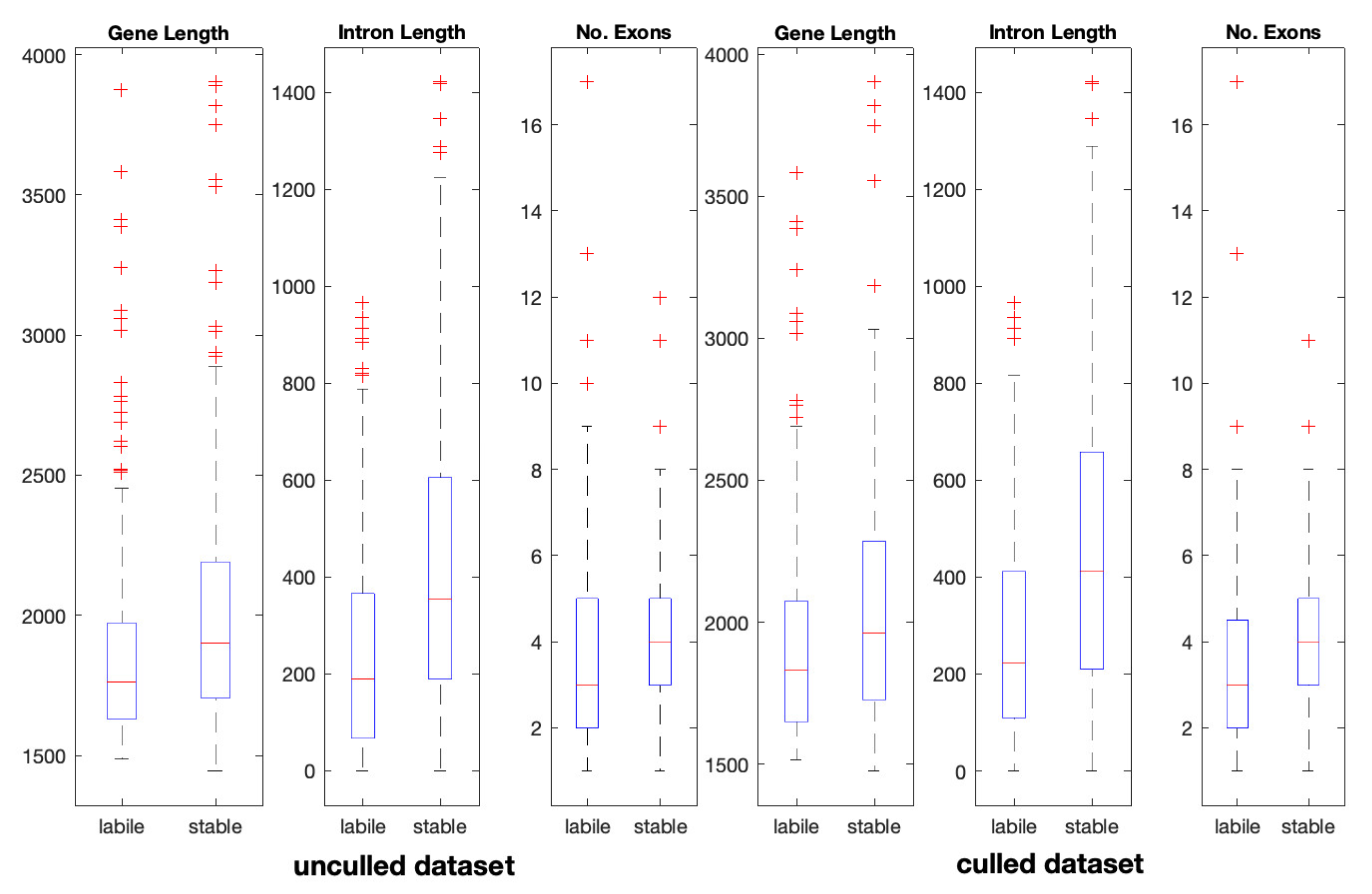

3.1. Analysis of Genomic Features

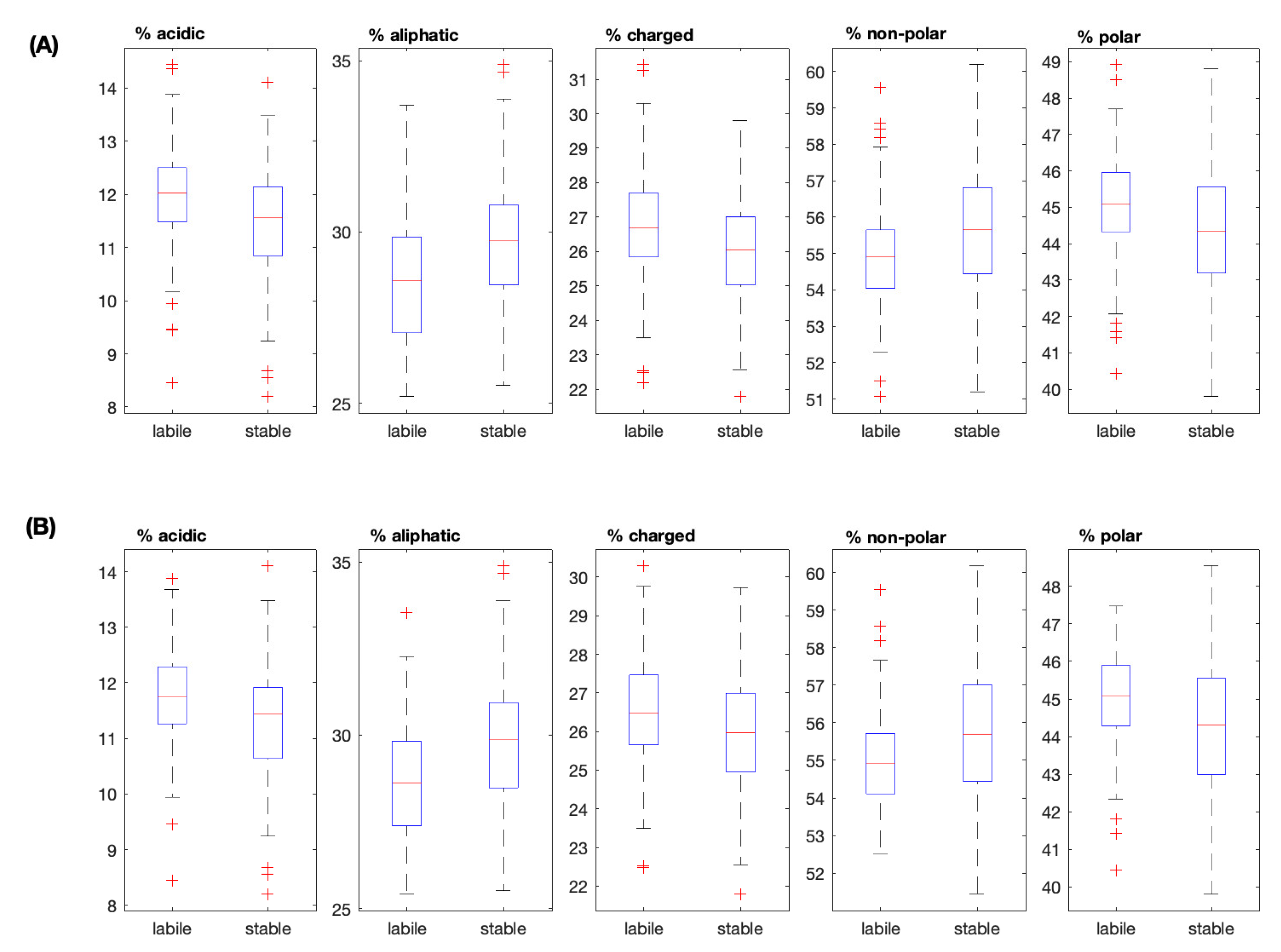

3.2. Analysis of Protein Features

3.3. Phosphorylation

3.4. Signal Peptides, Transmembrane Domains, and Protein Location

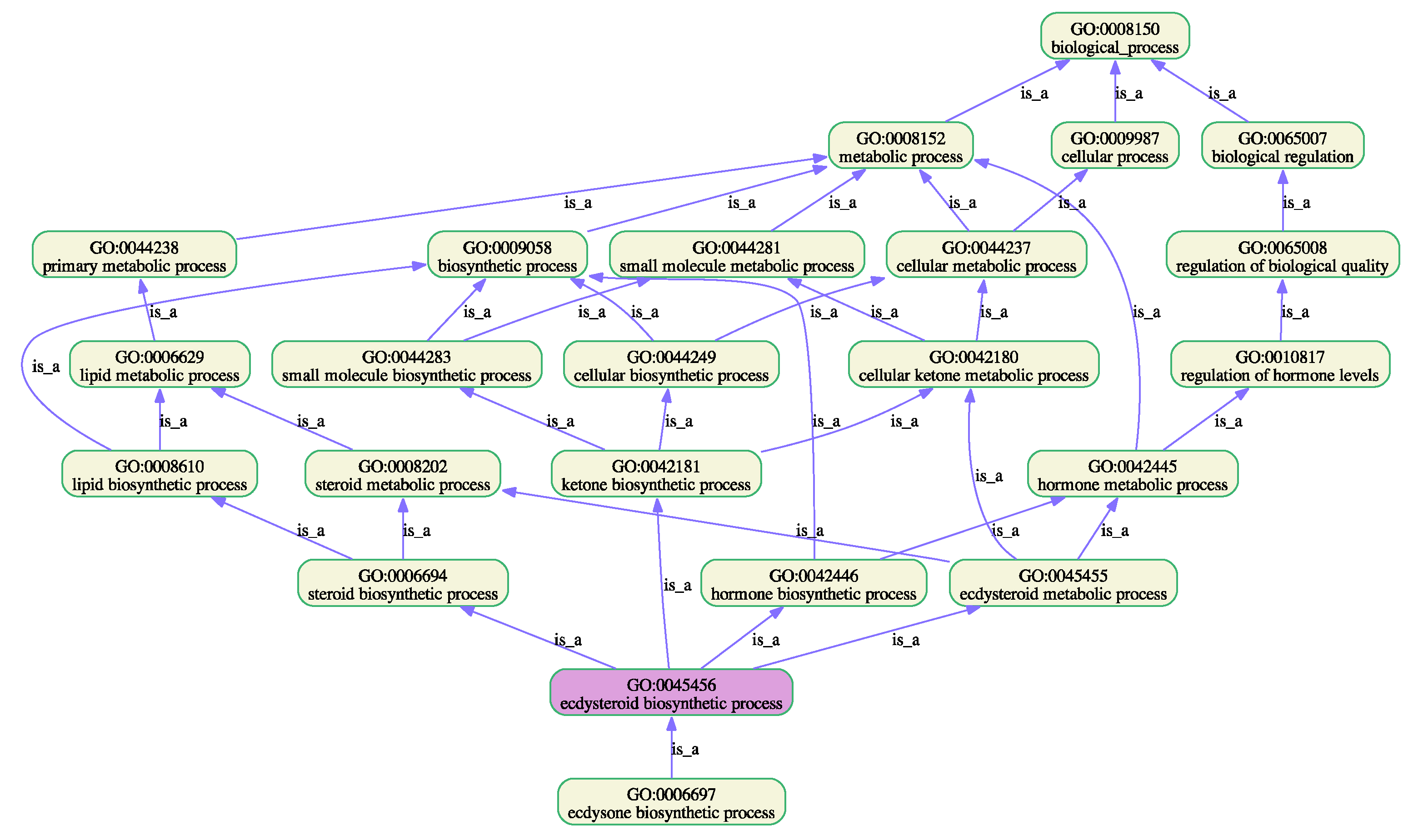

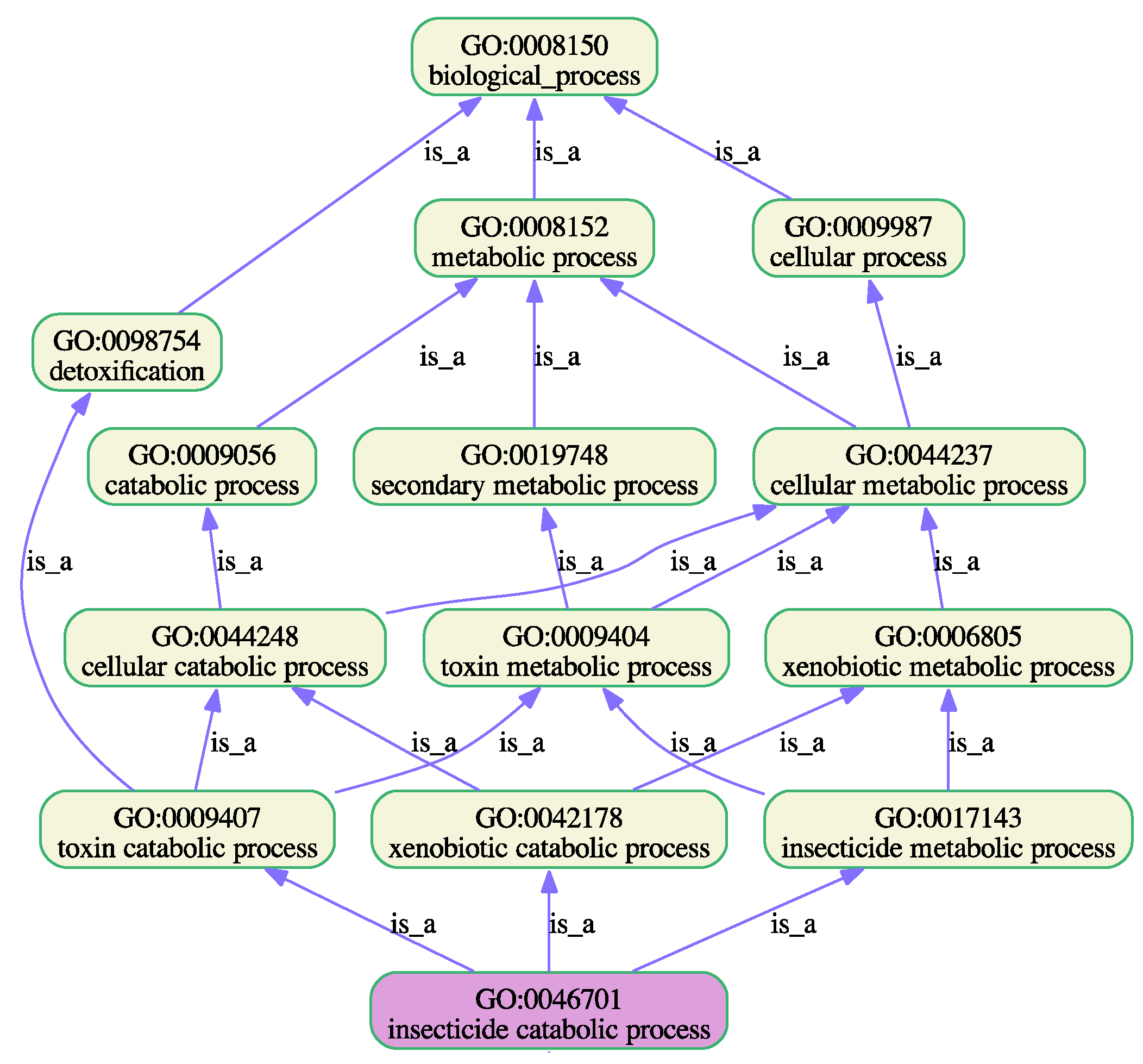

3.5. Gene Enrichment Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

References

- Nelson, D.R.; Nebert, D.W. Cytochrome P450 ( CYP ) Gene Superfamily. Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Klingenberg, M. Pigments of rat liver microsomes. Arch Biochem Biophys 1958, 75, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, J. , et al., Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res, 2021. 49(D1): p. D412-D419.

- Werck-Reichhart, D.; Feyereisen, R. Cytochromes P450: a success story. Genome Biol 2000, 1, REVIEWS3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannemann, F.; Bichet, A.; Ewen, K.M.; Bernhardt, R. Cytochrome P450 systems--biological variations of electron transport chains. Biochim Biophys Acta 2007, 1770, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiyama, K.; Hino, T.; Nagano, S. Diverse reactions catalyzed by cytochrome P450 and biosynthesis of steroid hormone. Biophys Physicobiol 2022, 19, e190021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidi, N.; Vontas, J.; Van Leeuwen, T. The role of glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) in insecticide resistance in crop pests and disease vectors. Curr Opin Insect Sci 2018, 27, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chakrabarty, S.; Jin, M.; Liu, K.; Xiao, Y. Insect ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) Transporters: Roles in Xenobiotic Detoxification and Bt Insecticidal Activity. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.R. Cytochrome P450 diversity in the tree of life. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom 2018, 1866, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, X.; Shi, T.; Gu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Liu, M.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ren, L.; Song, X.; et al. P450Rdb: a manually curated database of reactions catalyzed by cytochrome P450 enzymes. J Adv Res 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermauw, W.; Van Leeuwen, T.; Feyereisen, R. Diversity and evolution of the P450 family in arthropods. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 2020, 127, 103490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.R. Cytochrome P450 and the individuality of species. Arch Biochem Biophys 1999, 369, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.R. The cytochrome p450 homepage. Hum Genomics 2009, 4, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankov, K.V.; McArthur, A.G.; Gold, D.A.; Nelson, D.R.; Goldstone, J.V.; Wilson, J.Y. The cytochrome P450 (CYP) superfamily in cnidarians. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 9834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Qu, Q.; Wang, C.; He, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y. Involvement of CYP2 and mitochondrial clan P450s of Helicoverpa armigera in xenobiotic metabolism. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 2022, 140, 103696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.R. A world of cytochrome P450s. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2013, 368, 20120430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhao, X.; Li, M.; He, K.; Huang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Walters, J.R. Insect genomes: progress and challenges. Insect Mol Biol 2019, 28, 739–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strode, C.; Wondji, C.S.; David, J.P.; Hawkes, N.J.; Lumjuan, N.; Nelson, D.R.; Drane, D.R.; Karunaratne, S.H.; Hemingway, J.; Black, W.C.t.; et al. Genomic analysis of detoxification genes in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 2008, 38, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Yang, P.; Jiang, F.; Cui, N.; Ma, E.; Qiao, C.; Cui, F. Transcriptomic and phylogenetic analysis of Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus for three detoxification gene families. BMC Genomics 2012, 13, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyereisen, R. Arthropod CYPomes illustrate the tempo and mode in P450 evolution. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011, 1814, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyereisen, R. Evolution of insect P450. Biochem Soc Trans 2006, 34, 1252–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulbecco, A.B.; Calderón-Fernández, G.M.; Pedrini, N. Cytochrome P450 Genes of the CYP4 Clan and Pyrethroid Resistance in Chagas Disease Vectors. Frontiers in Tropical Diseases 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranson, H.; Claudianos, C.; Ortelli, F.; Abgrall, C.; Hemingway, J.; Sharakhova, M.V.; Unger, M.F.; Collins, F.H.; Feyereisen, R. Evolution of supergene families associated with insecticide resistance. Science 2002, 298, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulbecco, A.B.; Moriconi, D.E.; Calderon-Fernandez, G.M.; Lynn, S.; McCarthy, A.; Roca-Acevedo, G.; Salamanca-Moreno, J.A.; Juarez, M.P.; Pedrini, N. Integument CYP genes of the largest genome-wide cytochrome P450 expansions in triatomines participate in detoxification in deltamethrin-resistant Triatoma infestans. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 10177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sezutsu, H.; Le Goff, G.; Feyereisen, R. Origins of P450 diversity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2013, 368, 20120428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Good, R.T.; Gramzow, L.; Battlay, P.; Sztal, T.; Batterham, P.; Robin, C. The molecular evolution of cytochrome P450 genes within and between drosophila species. Genome Biol Evol 2014, 6, 1118–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, I.; Kenny, N.; Hui, J.; Hering, L.; Mayer, G. Halloween genes in panarthropods and the evolution of the early moulting pathway in Ecdysozoa. R Soc Open Sci 2018, 5, 180888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Sztal, T.; Pasricha, S.; Sridhar, M.; Batterham, P.; Daborn, P.J. Characterization of Drosophila melanogaster cytochrome P450 genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 5731–5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyereisen, R. Insect P450 inhibitors and insecticides: challenges and opportunities. Pest Manag Sci 2015, 71, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vontas, J.; Katsavou, E.; Mavridis, K. Cytochrome P450-based metabolic insecticide resistance in Anopheles and Aedes mosquito vectors: Muddying the waters. Pestic Biochem Physiol 2020, 170, 104666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabanidou, V.; Kampouraki, A.; MacLean, M.; Blomquist, G.J.; Tittiger, C.; Juarez, M.P.; Mijailovsky, S.J.; Chalepakis, G.; Anthousi, A.; Lynd, A.; et al. Cytochrome P450 associated with insecticide resistance catalyzes cuticular hydrocarbon production in Anopheles gambiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 9268–9273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahouedo, G.A.; Chandre, F.; Rossignol, M.; Ginibre, C.; Balabanidou, V.; Mendez, N.G.A.; Pigeon, O.; Vontas, J.; Cornelie, S. Contributions of cuticle permeability and enzyme detoxification to pyrethroid resistance in the major malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 11091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra-Rodriguez, K.; Suarez, A.F.; Salas, I.F.; Strode, C.; Ranson, H.; Hemingway, J.; Black, W.C.t. Transcription of detoxification genes after permethrin selection in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Insect Mol Biol 2012, 21, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauen, R.; Bass, C.; Feyereisen, R.; Vontas, J. The Role of Cytochrome P450s in Insect Toxicology and Resistance. Annu Rev Entomol 2022, 67, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, H., Yang, G., Winberg, G., Turin, L., Zhang, S., Crystal Structures of an Anopheles gambiae Odorant-binding Protein AgamOBP22a and Complexes with Bound Odorants, to be published.

- Mobegi, F.M.; Zomer, A.; de Jonge, M.I.; van Hijum, S.A. Advances and perspectives in computational prediction of microbial gene essentiality. Brief Funct Genomics 2017, 16, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Wenlock, S.; Kabir, M.; Tzotzos, G.; Doig, A.J.; Hentges, K.E. Identifying mouse developmental essential genes using machine learning. Dis Model Mech 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromolaran, O.; Aromolaran, D.; Isewon, I.; Oyelade, J. Machine learning approach to gene essentiality prediction: a review. Brief Bioinform 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo-Calderon, G.I.; Harb, O.S.; Kelly, S.A.; Rund, S.S.; Roos, D.S.; McDowell, M.A. VectorBase.org updates: bioinformatic resources for invertebrate vectors of human pathogens and related organisms. Curr Opin Insect Sci 2022, 50, 100860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Stoeckert, C.J., Jr.; Roos, D.S. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res 2003, 13, 2178–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.; Brunk, B.P.; Chen, F.; Gao, X.; Harb, O.S.; Iodice, J.B.; Shanmugam, D.; Roos, D.S.; Stoeckert, C.J., Jr. Using OrthoMCL to assign proteins to OrthoMCL-DB groups or to cluster proteomes into new ortholog groups. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 2011, Chapter 6, 6 12 11-16 12 19. [CrossRef]

- Sikic, K.; Carugo, O. Protein sequence redundancy reduction: comparison of various method. Bioinformation 2010, 5, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, P.; Longden, I.; Bleasby, A. EMBOSS: the European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet 2000, 16, 276–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, N.; Sicheritz-Ponten, T.; Gupta, R.; Gammeltoft, S.; Brunak, S. Prediction of post-translational glycosylation and phosphorylation of proteins from the amino acid sequence. Proteomics 2004, 4, 1633–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savojardo, C.; Martelli, P.L.; Fariselli, P.; Profiti, G.; Casadio, R. BUSCA: an integrative web server to predict subcellular localization of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, W459–W466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; You, R.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Zhu, S. NetGO 3.0: Protein Language Model Improves Large-scale Functional Annotations. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 2023, 21, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyte, J.; Doolittle, R.F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol 1982, 157, 105–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, N.; Jiang, Y.; Bergquist, T.R.; Lee, A.J.; Kacsoh, B.Z.; Crocker, A.W.; Lewis, K.A.; Georghiou, G.; Nguyen, H.N.; Hamid, M.N.; et al. The CAFA challenge reports improved protein function prediction and new functional annotations for hundreds of genes through experimental screens. Genome Biol 2019, 20, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.J.M.; Riziotis, I.G.; Borkakoti, N.; Thornton, J.M. Enzyme function and evolution through the lens of bioinformatics. Biochem J 2023, 480, 1845–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klopfenstein, D.V.; Zhang, L.; Pedersen, B.S.; Ramirez, F.; Warwick Vesztrocy, A.; Naldi, A.; Mungall, C.J.; Yunes, J.M.; Botvinnik, O.; Weigel, M.; et al. GOATOOLS: A Python library for Gene Ontology analyses. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 10872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesch-Bartlomowicz, B.; Oesch, F. Phosphorylation of cytochromes P450: first discovery of a posttranslational modification of a drug-metabolizing enzyme. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005, 338, 446–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, B.C.; Tomasiak, T.M.; Keniya, M.V.; Huschmann, F.U.; Tyndall, J.D.; O'Connell, J.D., 3rd; Cannon, R.D.; McDonald, J.G.; Rodriguez, A.; Finer-Moore, J.S.; et al. Architecture of a single membrane spanning cytochrome P450 suggests constraints that orient the catalytic domain relative to a bilayer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 3865–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srejber, M.; Navratilova, V.; Paloncyova, M.; Bazgier, V.; Berka, K.; Anzenbacher, P.; Otyepka, M. Membrane-attached mammalian cytochromes P450: An overview of the membrane's effects on structure, drug binding, and interactions with redox partners. J Inorg Biochem 2018, 183, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gricman, L.; Vogel, C.; Pleiss, J. Conservation analysis of class-specific positions in cytochrome P450 monooxygenases: functional and structural relevance. Proteins 2014, 82, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nature genetics 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, I.; Altab, G.; Raina, P.; de Magalhaes, J.P. Gene Size Matters: An Analysis of Gene Length in the Human Genome. Front Genet 2021, 12, 559998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.C. Role of Gene Length in Control of Human Gene Expression: Chromosome-Specific and Tissue-Specific Effects. Int J Genomics 2021, 2021, 8902428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorlova, O.; Fedorov, A.; Logothetis, C.; Amos, C.; Gorlov, I. Genes with a large intronic burden show greater evolutionary conservation on the protein level. BMC Evol Biol 2014, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.; Barradas, A.; Tzotzos, G.T.; Hentges, K.E.; Doig, A.J. Properties of genes essential for mouse development. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0178273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamsa, S.S.A.; Meloni, B.P. Arginine and Arginine-Rich Peptides as Modulators of Protein Aggregation and Cytotoxicity Associated With Alzheimer's Disease. Front Mol Neurosci 2021, 14, 759729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravanfar, R.; Sheng, Y.; Gray, H.B.; Winkler, J.R. Tryptophan extends the life of cytochrome P450. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120, e2317372120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Sun, L.; Pang, J.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Hu, X.; Li, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. Roles of cysteine in the structure and metabolic function of Mycobacterium tuberculosis CYP142A1. RSC Adv 2022, 12, 24447–24455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, B.R.; Mahalakshmi, R. Hydrophobic Characteristic Is Energetically Preferred for Cysteine in a Model Membrane Protein. Biophys J 2019, 117, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wronska, A.K.; Kaczmarek, A.; Bogus, M.I.; Kuna, A. Lipids as a key element of insect defense systems. Front Genet 2023, 14, 1183659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrese, E.L.; Soulages, J.L. Insect fat body: energy, metabolism, and regulation. Annu Rev Entomol 2010, 55, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatri, P.; Sirota, M.; Butte, A.J. Ten years of pathway analysis: current approaches and outstanding challenges. PLoS Comput Biol 2012, 8, e1002375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geistlinger, L.; Csaba, G.; Santarelli, M.; Ramos, M.; Schiffer, L.; Turaga, N.; Law, C.; Davis, S.; Carey, V.; Morgan, M.; et al. Toward a gold standard for benchmarking gene set enrichment analysis. Brief Bioinform 2021, 22, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Rhee, S.Y. Interpreting omics data with pathway enrichment analysis. Trends Genet 2023, 39, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, W.A.; Tomczak, A.; Khatri, P. Gene annotation bias impedes biomedical research. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attrill, H.; Gaudet, P.; Huntley, R.P.; Lovering, R.C.; Engel, S.R.; Poux, S.; Van Auken, K.M.; Georghiou, G.; Chibucos, M.C.; Berardini, T.Z.; et al. Annotation of gene product function from high-throughput studies using the Gene Ontology. Database (Oxford) 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, T.; Lam, H.Y.M.; Sorensen, K.K.; Tian, P.; Hansen, C.C.; Groves, J.T.; Jensen, K.J.; Christensen, S.M. Membrane anchoring facilitates colocalization of enzymes in plant cytochrome P450 redox systems. Commun Biol 2021, 4, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidorczuk, K.; Mackiewicz, P.; Pietluch, F.; Gagat, P. Characterization of signal and transit peptides based on motif composition and taxon-specific patterns. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 15751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | Clan2 | Clan3 | Clan4 | mitochondrial | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Family | Family | Family | |||

| Dmel | CYP18, 303-307 | CYP6, 9, 28, 308-310, 317 | CYP4, 311-313, 316, 318 | CYP12, 49, 301-2, 314-5 | ||

| 85 | No. genes: 6 | No. genes: 36 | No. genes: 32 | No. genes: 11 | [11] | |

| Agam | CYP15, 303-307 | CYP6, 9, 329 | CYP4, 325 | CYP12, 49, 301-2, 314-5 | ||

| 106 | No. genes: 10 | No. genes: 42 | No. genes: 45 | No. genes: 9 | [11] | |

| Aaeg | CYP15, 18, 303-307 | CYP6, 9, 329 | CYP4, 325 | CYP12, 49, 301-2, 314-5 | [18] | |

| 164 | No. genes: 11 | No. genes: 84 | No. genes: 59 | No. genes: 10 | ||

| Cqui | Cyp15, 303-307 | CYP6, 9, 329 | CYP4, 325 | Cyp12, 301-2, 314-14 | ||

| 196 | No. genes: 14 | No. genes: 88 | No. genes: 83 | No. genes: 11 | [19] |

| Unculled | Culled | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. genes | “stable” | “labile” | “stable” | “labile” | |

| Dmel | 83 | 53 | 30 | 46 | 22 |

| Agam | 94 | 49 | 45 | 31 | 28 |

| Aaeg | 131 | 58 | 73 | 33 | 30 |

| Cqui | 178 | 85 | 93 | 52 | 35 |

| Total | 486 | 245 | 241 | 162 | 115 |

| Features | Bioinformatic methods |

|---|---|

|

Genomic features: gene length, % of GC content, number of transcripts, number of exons, length of exon and intron |

VectorBase [39] |

|

Protein sequence features: protein length, molecular weight, protein charge, isoelectric point, amino acid composition, hydrophobicity |

EMBOSS Pepstats [43] |

| Phosphorylation | PhosNet 3.0 [44] |

| Signal peptide; transmembrane domains; Subcellular localisation | BUSCA [45] |

|

Gene Ontology terms: biological process, cellular component, molecular function |

NetGO 3.0 [46] |

| Datasets | Gene length (bp) | No. of exons | Exon length (bp) | Intron length (bp) | No. transcripts | % GC content | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-culled | “labile” | 1840 | 3 | 1524 | 311 | 1 | 47.20 |

| “stable” | 2149 | 4 | 1518 | 612 | 1 | 44.78 | |

| p-value | 2.8034e-07 | 1.0212e-08 | 0.0209 | 7.6899e-09 | 0.3531 | 0.0270 | |

| Culled | “labile” | 1890 | 3 | 1527 | 359 | 1 | 46.48 |

| “stable” | 2165 | 4 | 1521 | 612 | 1 | 45.63 | |

| p-value | 7.1450e-04 | 4.4157e-06 | 0.0302 | 1.5198e-04 | 0.6973 | 0.3718 | |

| * The median value of each feature is reported. p–values are determined from a Mann–Whitney U test. Statistically significant results were evaluated based on the Bonferroni corrected p–value of 0.0083. They are shown in bold typeface. | |||||||

| Unculled | Culled | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Property | “Labile” | “Stable” | p-value | “Labile” | “Stable” | p-value |

| MW | 5.8236e+04 | 5.8106e+04 | 0.0124 | 5.8454e+04 | 5.8162e+04 | 0.0249 |

| IEP | 8.3088 | 8.1503 | 0.2324 | 8.2718 | 8.3542 | 0.4991 |

| Charge | 9 | 9.5000 | 0.4037 | 10 | 10.5000 | 0.0724 |

| Hydrophobicity | -19.6450 | -16.0583 | 4.3384e-08 | -18.7226 | -15.5340 | 2.7720e-04 |

| Aromatic | 13.2110 | 13.1148 | 0.5403 | 13.2110 | 13.1417 | 0.6721 |

| Aliphatic | 28.5714 | 29.7619 | 3.4826e-10 | 28.6299 | 29.8651 | 3.1629e-06 |

| Acidic | 12.0240 | 11.5686 | 3.5141e-08 | 11.7530 | 11.4458 | 3.8132e-05 |

| Basic | 14.7810 | 14.6000 | 0.0258 | 14.6535 | 14.6939 | 0.6806 |

| Charged | 26.6791 | 26.0521 | 1.2929e-06 | 26.4706 | 25.9669 | 0.0056 |

| Polar | 45.0980 | 44.3340 | 6.3566e-07 | 45.0902 | 44.3137 | 2.4062e-04 |

| Non-polar | 54.9020 | 55.6660 | 5.1469e-07 | 54.9098 | 55.6863 | 2.4062e-04 |

| Small | 44.6000 | 44.6939 | 0.6356 | 44.6680 | 44.4890 | 0.6232 |

| Tiny | 23.3202 | 23.5887 | 0.0306 | 23.5409 | 23.8095 | 0.3240 |

| * The median value of each feature is reported. p–values are determined from a Mann–Whitney U test. Statistically significant results were evaluated based on the Bonferroni corrected p–value of 0.0038. They are shown in bold typeface. | ||||||

| Unculled | Culled | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aa* | “Labile” | “Stable” | p-value | “Labile” | “Stable” | p-value |

| A | 5.6711 | 6.1100 | 4.0438e-04 | 5.8601 | 6.2500 | 0.0145 |

| C | 1.1811 | 1.5238 | 1.9760e-10 | 1.2048 | 1.5385 | 2.8718e-05 |

| D | 5.4409 | 5.3465 | 0.0230 | 5.4104 | 5.2427 | 0.0963 |

| E | 6.4338 | 6.1151 | 8.9284e-06 | 6.3241 | 6.0362 | 0.0012 |

| F | 6.5476 | 6.2000 | 0.0014 | 6.4833 | 6.1100 | 0.0150 |

| G | 5.6075 | 5.3254 | 0.0125 | 5.6863 | 5.3407 | 0.0966 |

| H | 2.1696 | 2.3301 | 4.2799e-05 | 2.2018 | 2.3297 | 0.0233 |

| I | 6.1185 | 6.0827 | 0.8018 | 6.1185 | 6.0038 | 0.7398 |

| K | 6.4639 | 5.4000 | 1.3464e-14 | 6.0998 | 5.3360 | 3.4017e-05 |

| L | 10.0616 | 11.0656 | 2.6111e-12 | 10.2970 | 11.0891 | 7.5251e-07 |

| M | 3.3730 | 2.9851 | 4.2922e-05 | 3.4068 | 3.0364 | 0.0015 |

| N | 4.0161 | 3.9448 | 0.3603 | 3.9062 | 3.8076 | 0.1330 |

| P | 5.0710 | 5.1081 | 0.2145 | 4.9900 | 5.0813 | 0.1682 |

| Q | 3.4765 | 3.5849 | 0.1371 | 3.6290 | 3.6735 | 0.5681 |

| R | 6.0852 | 6.6202 | 1.0888e-04 | 6.3116 | 6.7308 | 0.0013 |

| S | 5.3435 | 5.4104 | 0.4267 | 5.3465 | 5.4409 | 0.4281 |

| T | 5.4326 | 5.2104 | 0.0015 | 5.4902 | 5.1383 | 0.0011 |

| V | 6.5056 | 6.2745 | 0.0128 | 6.4885 | 6.2622 | 0.0318 |

| W | 0.9452 | 1.1236 | 4.8193e-06 | 0.9328 | 1.1494 | 3.9031e-05 |

| Y | 3.5185 | 3.6072 | 0.5588 | 3.4926 | 3.6000 | 0.5164 |

| * amino acid (aa). The p-value for the Bonferroni correction is 0.0025. Statistically significant differences are shown in bold typeface. | ||||||

| Non-culled | Culled | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological feature | No.“labile” CYPs | No.“stable” CYPs | No. “labile” CYPs | No. “stable” CYPs |

| Signal peptide | 19 (7.9%) | 28 (11.4%) | 8 (7.0%) | 18 (11.2%) |

| Mito transit | 11 (4.6%) | 5 (2%) | 7 (6.1%) | 2 (1.3%) |

| Mitochondrial membrane | 11 (4.6%) | 5 (2%) | 7 (6.1%) | 2 (1.3%) |

| N-terminal helix | 198 (82.2%) | 196 (80.0%) | 95 (82.6%) | 132 (81.5%) |

| GO term | Description | Subset1 | All CYPs2 | Dmel2 | Agam2 | Aaeg2 | Cqui2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. GO:0048856 | Anatomical structure development | S | 135 (55.1) | 27 (11.0) | 26 (10.6) | 33 (13.5) | 49 (20) |

| L | 75 | 7 | 18 | 23 | 27 | ||

| 2. GO:0008610 | lipid biosynthetic process | S | 141 (57.5) | 26 (10.6) | 26 (10.6) | 38 (15.5) | 51 (20.8) |

| L | 24 (9.9) | 4 (1.7) | 3 (1.2) | 8 (3.3) | 9 (3.7) | ||

| 3. GO:0008202 | steroid metabolic process | S | 95 (38.8) | 11 (4.5) | 29 (11.8) | 37 (15.1) | 18 (7.3) |

| L | 10 (4.1) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 6 (2.5) | ||

| 4. GO:0042445 | hormone metabolic process | S | 53 (21.6) | 12 (4.9) | 15 (6.1) | 15 (6.1) | 11(4.5) |

| L | 4 (1.6) | - | - | - | 4 (1.6) | ||

| 5. GO:0007275 | multicellular organism development | S | 91 (37.1) | 19 (7.7) | 18 (7.3) | 22 (9.0) | 32 (13.0) |

| L | 25 (10.4) | 2 (0.8) | 7 (2.9) | 9 (3.7) | 7 (2.9) | ||

| 6. GO:0009791 | post-embryonic development | S | 19 (7.7) | 6 (2.4) | 4 (1.6) | 6 (2.4) | 3 (1.2) |

| L | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| 7. GO:0002165 | instar larval or pupal development | S | 17 (6.9) | 6 (2.4) | 6 (2.4) | 3 (1.2) | 2 (0.8) |

| L | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| 8. GO:0045456 | ecdysteroid biosynthetic process | S | 10 (4.1) | 4 (1.6) | 4 (1.6) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) |

| L | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| 9. GO:0006805 | xenobiotic metabolic process | S | 24 (9.8) | 2 (0.8) | 5 (2.0) | 6 (2.4) | 11 (4.5) |

| L | 69 (28.6) | 9 (3.7) | 11 (4.6) | 28 (11.6) | 21 (8.7) | ||

| 10. GO:0046680 | response to DDT | S | 30 (12,2) | 8 (3.3) | 5 (2.0) | 8 (3.3) | 9 (3.7) |

| L | 86 (35.7) | 10 (4.1) | 22 (9.1) | 29 (12.0) | 25 (10.4) | ||

| 11. GO:0009404 | toxin metabolic process | S | 12 (4.9) | 3 (1.2) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | 5 (2.0) |

| L | 28 (11.6) | 7 (2.9) | 2 (0.8) | 10 (4.1) | 9 (3.7) | ||

| 1 S denotes “stable”; L denotes “labile). 2 values in () denote % | |||||||

| “Stable” gene tendencies | “Labile” gene tendencies |

|---|---|

| Longer genes; longer introns; more exons | Simpler, shorter gene structure |

| More hydrophobic; relative proportion of aliphatic amino acids higher; enriched in Cys, Arg, Leu, and Trp | Less hydrophobic; relative proportion of charged and polar amino acids higher; enriched in Glu, Lys, and Met |

| Involved in biosynthetic and developmental processes, such as biosynthesis of lipids and hormones essential for instar larval or pupal morphogenesis | Involved in cellular catabolic processes, detoxification of xenobiotics and insecticide metabolic processes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).