1. Introduction

Biopesticides, which are safer alternatives to conventional pest control chemicals, are primarily derived from natural sources. These include microbial and biochemical biopesticides, as well as plant-incorporated protectants (PIPs). Together, they currently account for 5% of the global pesticide market [

1,

2]. Chalcones and their derivatives have garnered significant attention due to their wide range of nutritional and biological activities, such as anti-inflammatory, antitumor, antibacterial, antifungal, antimalarial, antitubercular, and anti-pigmentation effects, often demonstrating remarkable efficacy [

3]. They are also recognized for their role as bioprotectants [

4,

5]. Dihydrochalcones, naturally biosynthesized through the well-understood phenylpropanoid pathway in plants, were initially believed to be limited to around 30 plant families. However, along with more advanced analytical techniques development, it has been discovered that dihydrochalcones are more widely distributed in nature. Apples are considered as the richest dietary source of these compounds, which are also found in leaves and roots of apple and hairy roots obtained through genetic transformation [

6]. In addition, dihydrochalcones were also found in other different plant families, including

Asteraceae,

Lauraceae, and

Salicaceae [

7,

8].

Dihydrochalcones have demonstrated effectiveness against a wide range of target pathogens, including fungi such as

Phytophthora,

Pythium, downy mildew (P

seudoperonospora cubensis,

Plasmopara),

Colletotrichum,

Rhizoctonia, and rust (

Puccinia triticina), as well as bacteria like

Xanthomonas and

Pseudomonas. These compounds have been tested on various host plants, including vegetables, leafy greens, fruits, and wheat [

9,

10].

Werner et al. (2020) demonstrated that 2’,4’-dihydroxyhydrochalcone and its synthetic analogs show great promise as potential anti-

Saprolegnia agents, largely due to their high lipophilicity, particularly in molecules with alkyl chains longer than 10 carbon atoms. These compounds are considered promising scaffolds for the development of new, potent anti-oomycete agents [

11].

Antimicrobial activities very often go hand in hand with antioxidant properties. To assess these properties, spectrometric antioxidant tests, such as DPPH and reducing power assays are commonly employed.

The 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay is a widely used, quick, simple, and cost-effective method for evaluating antioxidant activity by using free radicals. This assay measures the ability of compounds to act as hydrogen donors or free radical scavengers (FRS). In the DPPH test, a stable free radical, DPPH, is reduced in the presence of an antioxidant, leading to a change in its distinctive purple color, which has a strong absorbance peak at 517 nm. When an FRS antioxidant reacts with DPPH, it forms DPPH-H, resulting in decreased absorbance and a color shift from purple to yellow as hydrogen atoms are donated. This color change indicates a reduction in radical concentration, directly reflecting the antioxidant’s capacity to neutralize free radicals. As the DPPH solution interacts with a hydrogen-donating compound, it transforms into diphenylpicrylhydrazine, losing its violet color, which signifies the antioxidant's electron-donating power [

12,

13]. The reducing power is determined by the reduction of Fe (III) to Fe (II) in the presence of the tested compound. The concentration of Fe (II) can be monitored by measuring the formation of Prussian blue at 700 nm. The higher dye concentration and therefore the higher absorbance, indicates greater reducing power and enhanced antioxidant activity of the tested compound.

Information on the degradability of organic chemicals is valuable for both hazard and risk assessments. Aquatic hazard classification and general hazard assessments typically rely on standardized tests for ready biodegradability. However, data from tests simulating biodegradation in environments such as water, aquatic sediment, and soil can also contribute to these samples’ assessment [

14]. The European Commission's Technical Guidance Document on Risk Assessment suggests that for readily biodegradable chemicals meeting the pass criteria and the 10-day window, a degradation rate constant (k) of 1.0 hour⁻¹, with a half-life of 0.69 hours, can be used in models estimating chemical removal in sewage treatment plants (STP models). If a chemical pass the level within the 28-day test period but fails the 10-day window, a lower rate constant of 0.3 hour⁻¹, corresponding to a half-life of 2.3 hours, may be applied in STP models [

15].

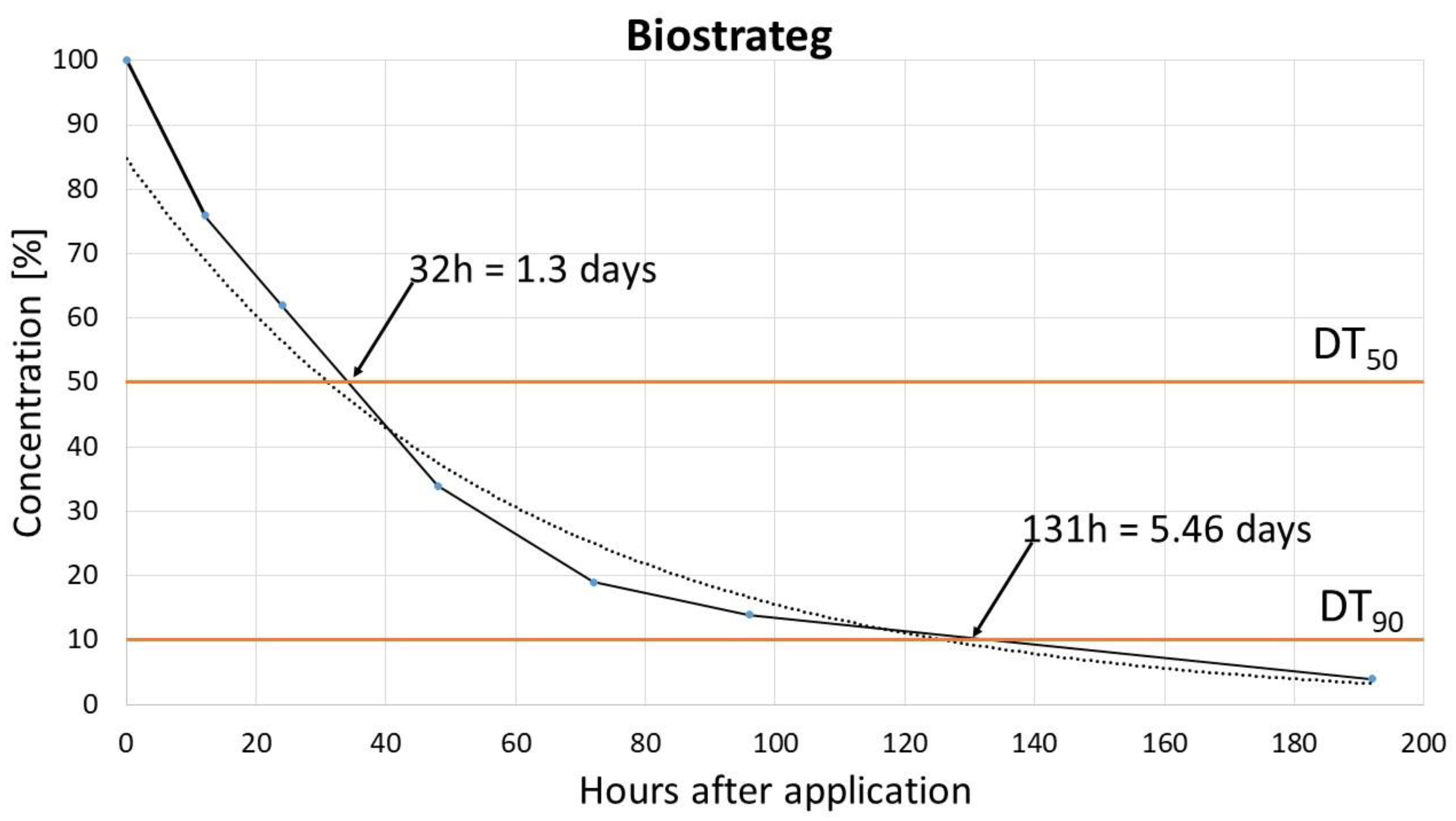

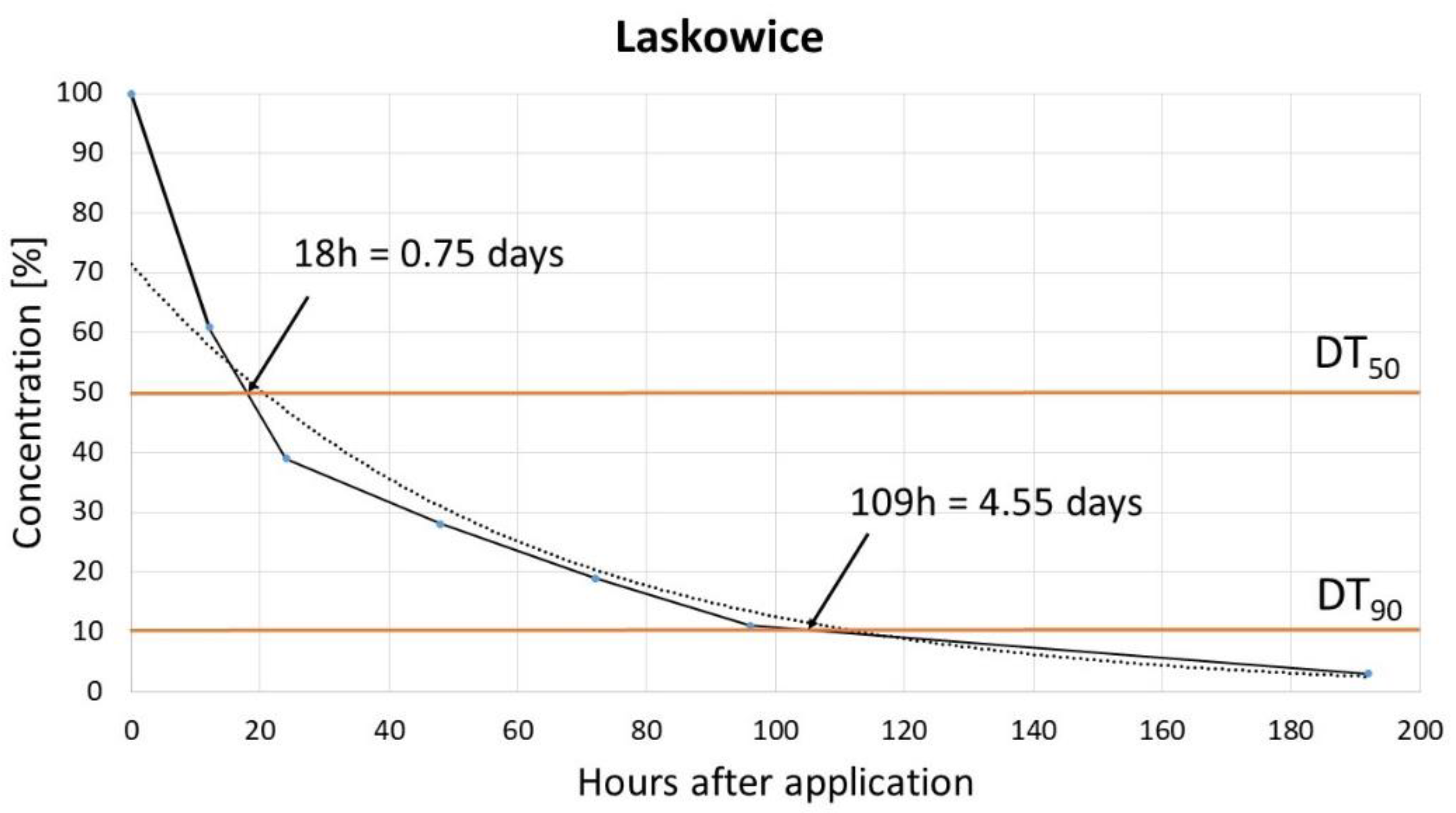

While the antimicrobial activities and effectiveness of biopesticides are crucial, their safety for humans and the environment is equally important, encompassing factors such as toxicity, persistence, and other related concerns. The persistence and dissipation of active substances are measured using DT (dissipation time), especially DT

50 and DT

90 values, which represent the time required for 50% and 90% of a substance, respectively, to disappear. “Disappearance” encompasses all processes leading to the substance’s transformation, degradation, and eventual mineralization, including microbial degradation, chemical hydrolysis, photochemical reactions, and other mechanisms like leaching, volatilization, and plant uptake. In soil, laboratory experiments generally consider a DT

50 of less than 60 days at 20°C acceptable (or less than 90 days at 10°C for applications in colder regions). In field conditions, acceptable thresholds are a DT

50 of less than 3 months and a DT

90 of less than 1 year. It should be noted that DT

50 and DT

90 indicators do not differentiate between degradation processes—such as mineralization, microbial degradation, hydrolysis, or photochemical reactions—and loss through leaching, volatilization, or plant uptake. Instead, these values provide a holistic assessment of a substance’s dissipation, encompassing all contributing processes [

16]. In terms of adsorption - it depends on two main factors - pesticide properties and soil properties showing the behavior of pesticide in soil. Molecular properties of pesticides like solubility, ionisability and hydrophilicity and lipophilicity are crucial [

17].

Determination of antioxidant activity in the case of biopesticides is important in the context of assessing their biodegradability in the environment, because antioxidants are able to influence the decomposition processes associated with radicals and redox reactions [

18].

Various analytical methods are available for determining chalcone concentrations across different matrices, including chromatography with a range of detectors, MALDI, and HNMR techniques [

3]. Pompermaier et al. employed an UHPLC-DAD method to identify six primary dihydrochalcone derivatives [

19]. In this experiment, UHPLC-ESI-MS/MS was used to determine the DT

50 and DT

90 values as well as to assess the dihydrochalcone concentration after sorption experiment.

The aim of the study was to evaluate the attributes of pinocembrin dihydrochalcone, including its antioxidant properties and environment safety as potential biopesticide. This could be assessed through the soil dissipation study experiment as well as organic carbon partition coefficient, Koc.

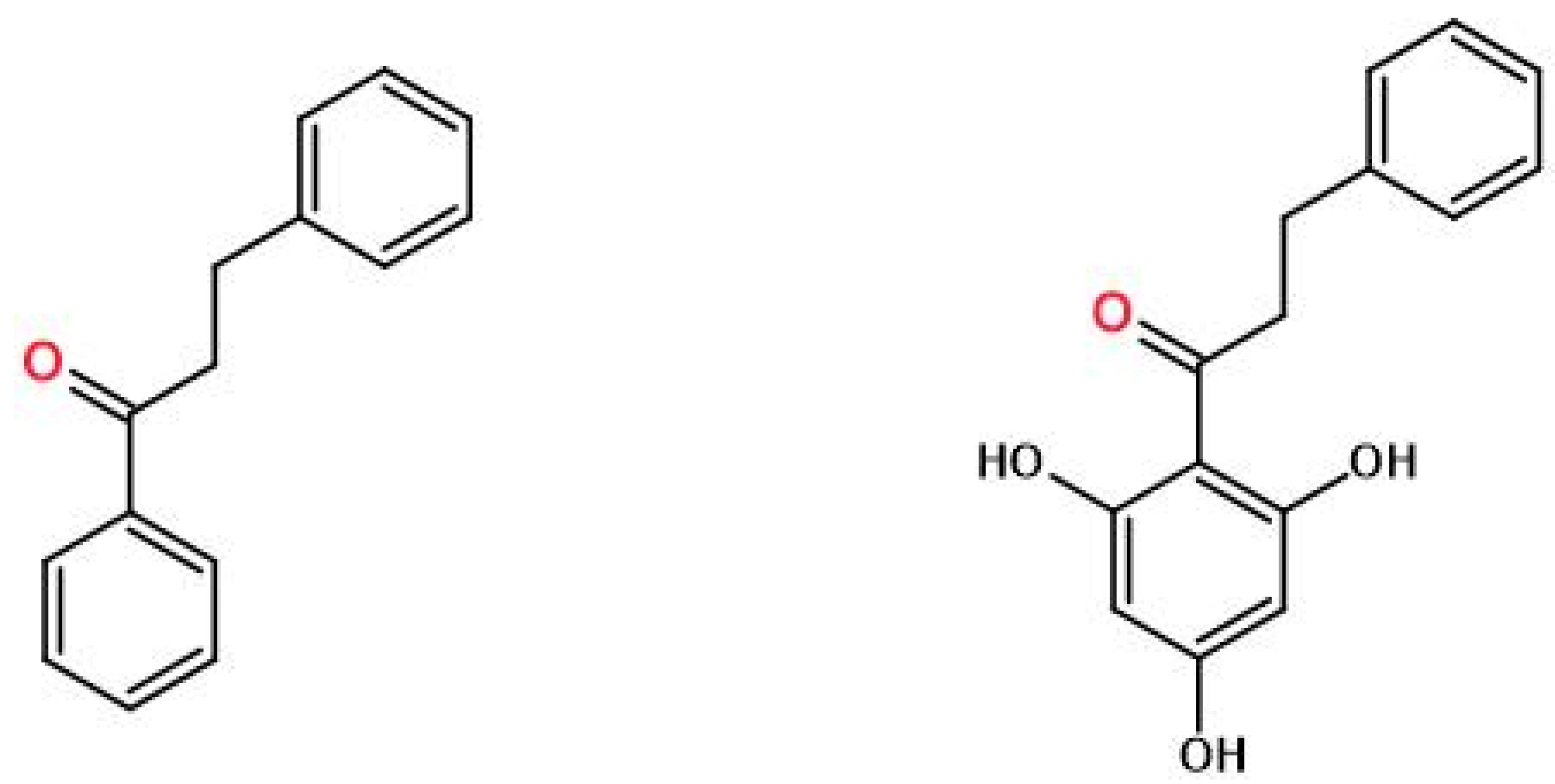

Figure 1.

Dihydrochalcone (left) and pinocembrin dichydrochalcone (3-phenyl-1-(2,4,6-trihydroxyphenyl)-1-propanone) (right).

Figure 1.

Dihydrochalcone (left) and pinocembrin dichydrochalcone (3-phenyl-1-(2,4,6-trihydroxyphenyl)-1-propanone) (right).

3. Discussion

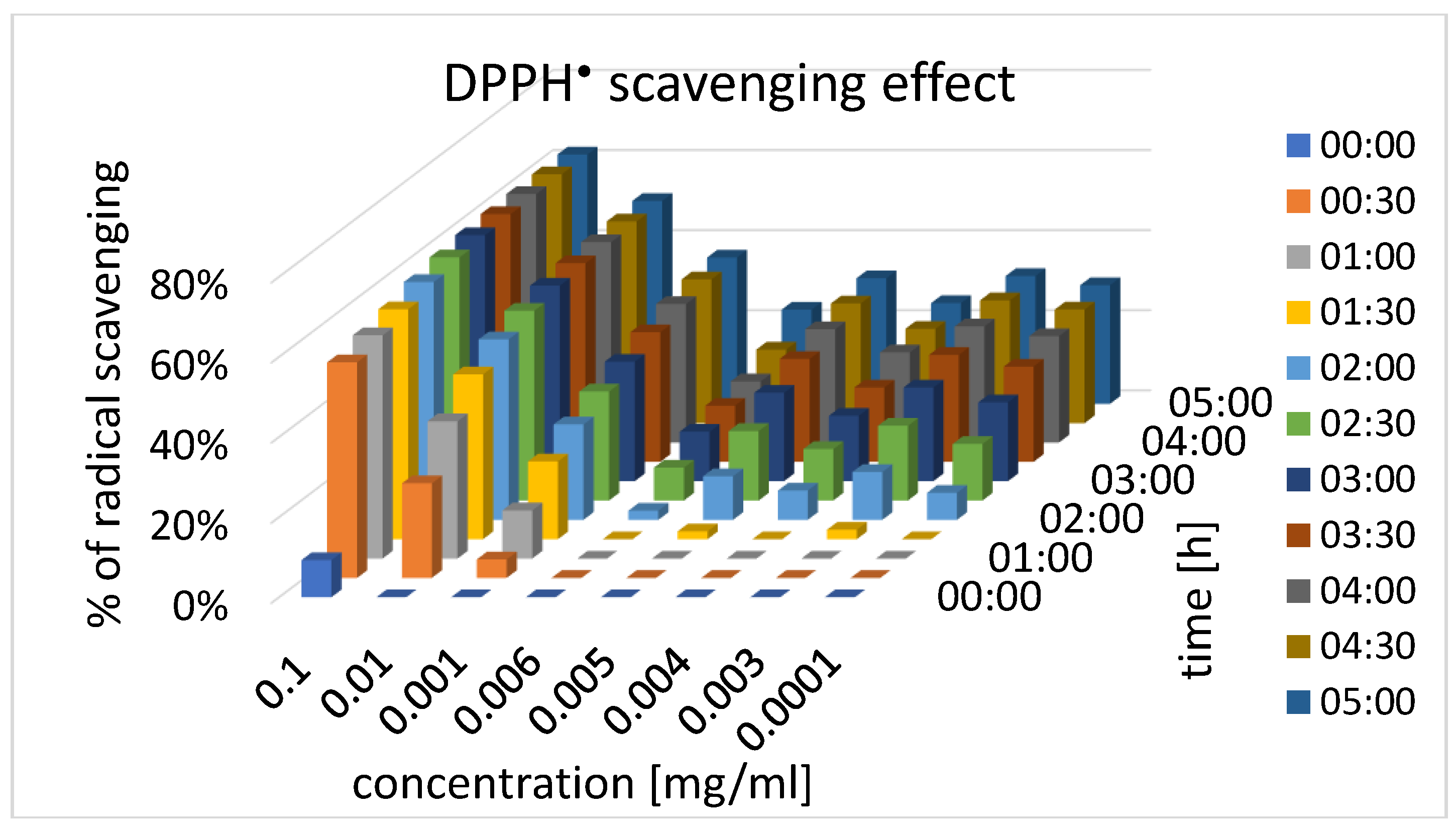

The antioxidant activity of dihydrochalcone was assessed through DPPH radical scavenging, and the results revealed a dose-dependent response

. In the water solution, the scavenging effect was most pronounced at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL, reaching a plateau after 1.5 hours. As the concentration of dihydrochalcone decreased, the time required to achieve peak activity increased proportionally, indicating that higher concentrations lead to quicker onset of antioxidant activity. This behavior suggests that dihydrochalcone has the potential for effective antioxidant action, though its effectiveness in agricultural applications may be limited by the concentration range typically used in such contexts. Specifically, in the 300-600 ppm range, common in agricultural applications, the scavenging activity did not reach the effective concentration (EC

50), which was calculated to be 0.0096 mg/mL. These findings suggest that dihydrochalcone may be more effective as an antioxidant at higher concentrations than those typically applied in agriculture. The concentration is just as important as the structure of the dihydrochalcone, where the number of phenolic hydroxyl groups may enhance antioxidant activity, while glycosylation could reduce it [

25,

26].

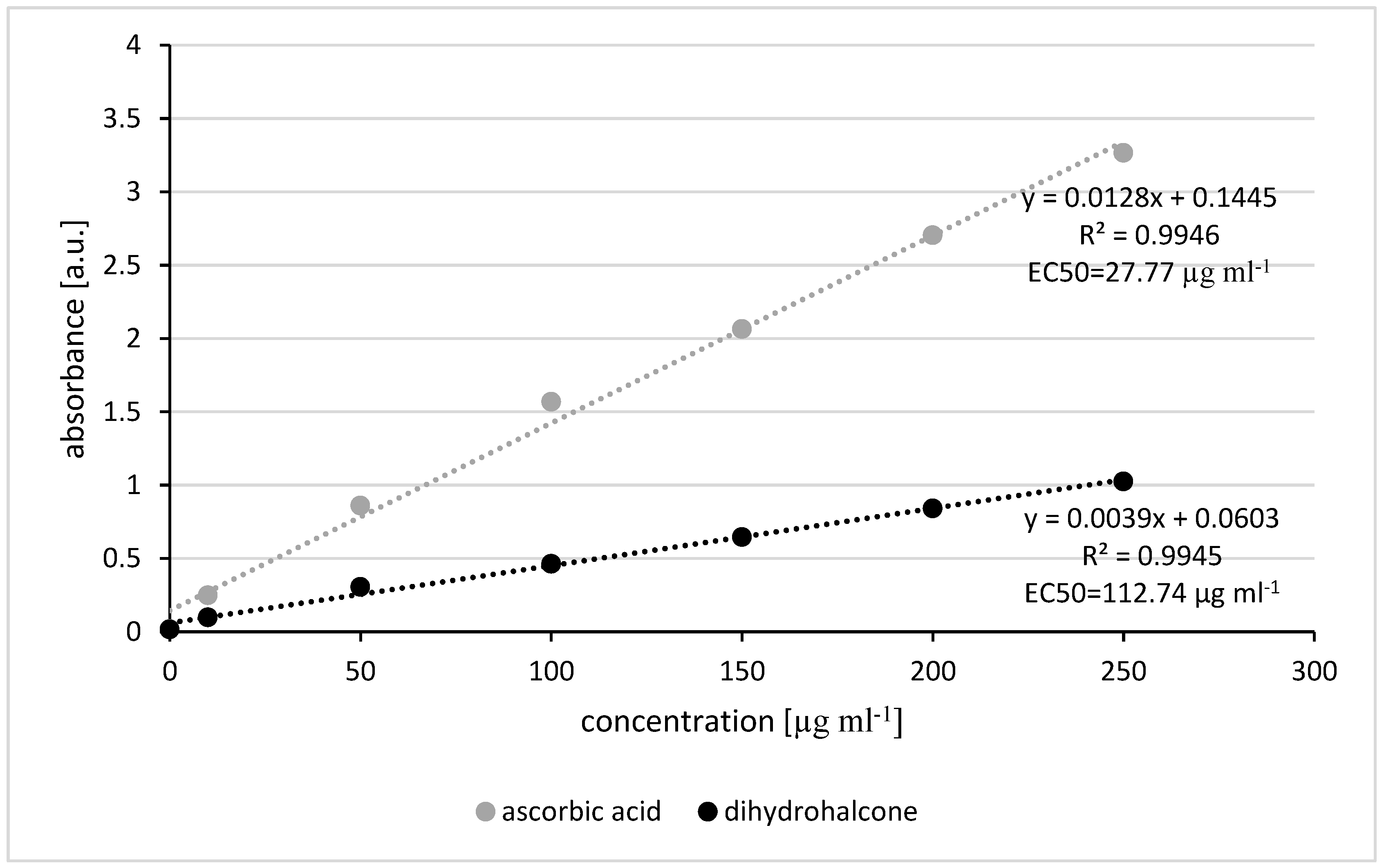

The reducing power of pinocembrin dihydrochalcone was found to be lower than that of ascorbic acid, with EC

50 values of 112.74 µg/mL for pinocembrin dihydrochalcone and 27.77 µg/mL for ascorbic acid. This indicates that while pinocembrin dihydrochalcone has antioxidant potential, it is less potent than ascorbic acid in terms of reducing power. However, the observed linear increase in antioxidant activity with concentration suggests that pinocembrin dihydrochalcone could still be a valuable antioxidant at appropriate concentrations. These findings are consistent with previous studies, such as those by Chen et al. (2017) [

24], who reported comparable reducing power between phloridzin (a dihydrochalcone) and ascorbic acid within a concentration range of 100-300 µg/mL.

The dissipation study, which aimed to determine the degradation rates of pinocembrin dihydrochalcone, revealed that it follows a single first-order (SFO) kinetic model. Rapid degradation of pinocembrin dihydrochalcone was observed, with a DT

50 (time for concentration to decrease to 50% of its initial value) ranging from 0.85 to 1.7 days and a DT

90 (time for concentration to decrease to 10%) between 4.55 and 5.26 days. These findings align with the results reported by Pedrinho et al. [

9], who also observed rapid dissipation of dihydrochalcone across different soil types, suggesting that dihydrochalcone breaks down quickly in the environment, reducing its persistence and potential for accumulation. This rapid degradation may be advantageous for minimizing environmental impact, but it also implies that repeated or continuous applications may be necessary for sustained effectiveness in agricultural settings. Soil degradation rates can be influenced by various factors, including the soil's physicochemical properties (such as pH and organic carbon content), biological properties (such as microbial activity and distribution), and environmental conditions, like temperature and moisture. The soil chemical properties also play a role in determining both the degradation route and rate. Degradation rates may also vary, with multiple studies confirming significant field-to-field differences in pesticide dissipation [

26,

27].

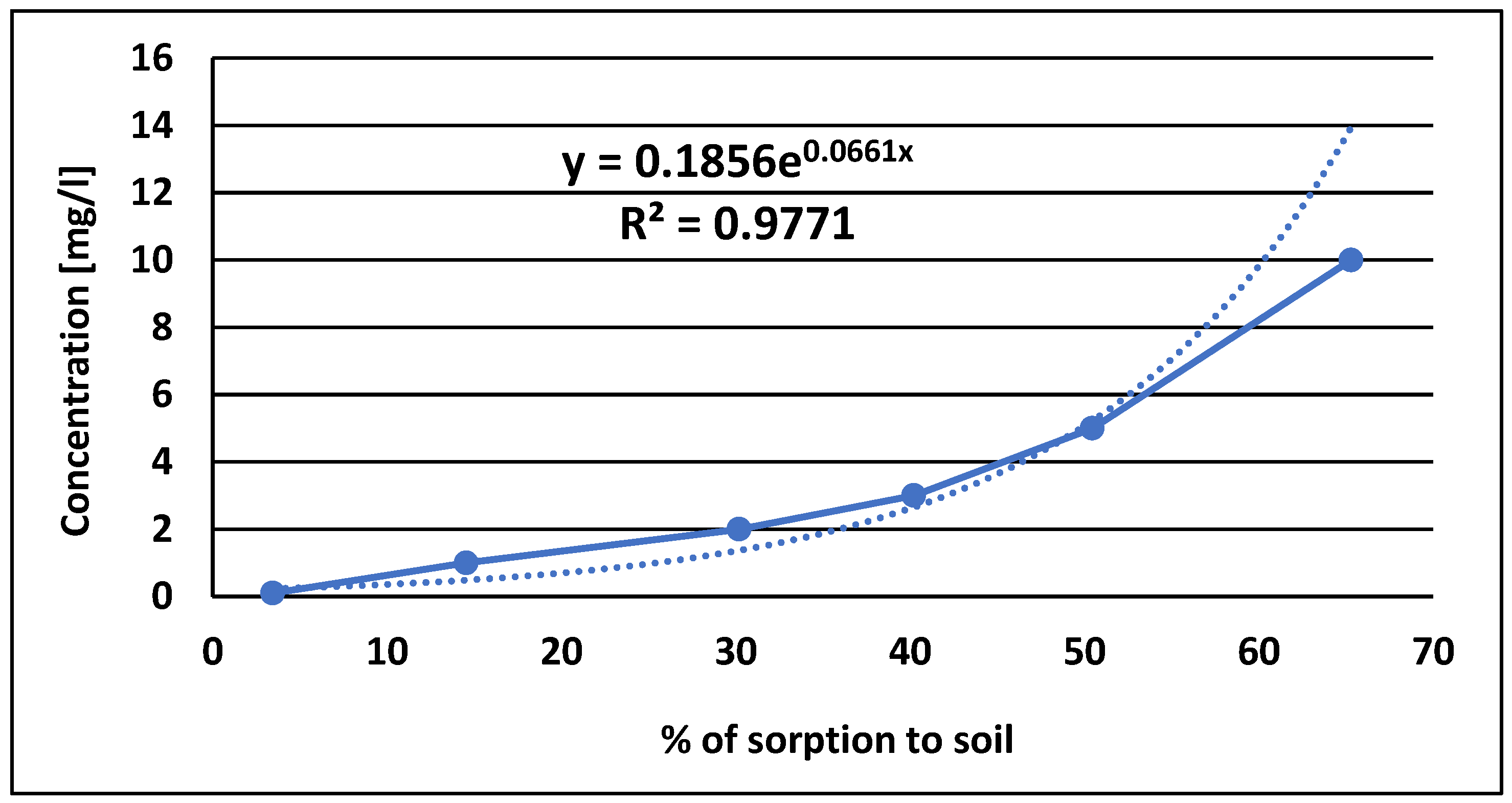

The sorption characteristics of pinocembrin dihydrochalcone were also studied, and the results indicated that its sorption to soil followed a Freundlich isotherm, which is indicative of a nonlinear adsorption process involving both absorption and adsorption mechanisms. The Freundlich model suggests that pinocembrin dihydrochalcone interacts with soil through active sites that vary in both quantity and quality, influencing the strength of adsorption. The measured partition coefficient (KF) value of 0.0661 suggests a low affinity for soil, indicating that pinocembrin dihydrochalcone is less likely to be strongly bound to soil particles. This result implies that pinocembrin dihydrochalcone may be subject to quicker leaching from the soil, reducing its potential for long-term soil residence and effectiveness. Furthermore, the low KF value suggests that pinocembrin dihydrochalcone is less likely to undergo aging processes that would otherwise increase its persistence in the soil.

Overall, the findings of this study highlight the promising antioxidant potential of dihydrochalcone, particularly in water solutions, while also underscoring the influence of environmental factors such as solvent type, concentration, and soil interactions on its bioactivity. While pinocembrin dihydrochalcone exhibits a moderate antioxidant effect and rapid degradation in the soil, its low affinity for soil and rapid dissipation suggest that it may be more effective in short-term applications, with careful consideration needed for its persistence and long-term efficacy in agricultural settings.

4. Materials and Methods

Material

The tested material, pinocembrin dihydrochalcone, was supplied by Methabolic Insight Ltd. (Ness Ziona, Izrael). Pinocembrin dihydrochalcone (3-phenyl-1-(2,4,6-trihydroxyphenyl)-1-propanone) is a white, amorphous powder, produced synthetically with 99,5% purity.

Soil Dissipation Studies

The dissipation study of dihydrochalcone was done under controlled laboratory conditions using growth chambers. Field studies are only required when the DT50, determined under laboratory conditions at 20°C and a soil moisture content corresponding to a pF value of -10 to -32 kPa, exceeds 60 days.

The experiment followed the OECD 307 protocol with slight modifications [

28]. Soil samples were collected from the upper layer (0-15 cm) of two soil types, Laskowice and Biostrateg, both free of dihydrochalcone residues. After passing the soil through a 2-mm sieve, it was stored in covered trays in a greenhouse for 10 days with regular mixing. Soil moisture content was measured by drying samples at 105°C for 24 hours and calculating the weight difference. To standardize conditions, soil moisture was maintained at 60% of field capacity, monitored regularly, and adjusted with distilled water as needed.

Soil samples were placed in 60 mm diameter pots (height: 55 mm), with three replicates per variant. These pots were then transferred to growth chambers set to a day/night temperature cycle of 20°C, with light intensity at 250 ±10 µmol·m-2·s-1 photosynthetic photon flux. Two days after setting up the pots in the chambers, dihydrochalcone was applied using a stationary chamber sprayer equipped with a TeeJet XR 11003-VS mobile nozzle. The application rate matched field conditions (200 L/ha). Soil samples (one pot, approximately 150 g, per sample/replicate) were collected at 1 hour (initial concentration) and at 1, 3, 6, 12, 21, and 36 days after treatment (DAT).

For analysis, soil samples were extracted with methanol using a high-pressure, high-temperature extractor. The methanolic extract was then centrifuged at 7500 rpm, and the supernatant was used. The quantitative analysis of dihydrochalcones was performed using ultrafast liquid chromatography coupled with a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (UHPLC-MS/MS).

Chamber Conditions:

Day period: 6 hours with 10% light intensity.

Night period: 16 hours with no light.

Basic Physicochemical Properties of the Soil

Key physicochemical parameters of the two soil types - Laskowice and Biostrateg - were analyzed, including pH, phosphorus, and potassium content, as well as granulometric composition. Soil pH was measured potentiometrically using a 1 M KCl solution, and phosphorus and potassium content was determined using the Egner-Riehm method. Soil texture analysis was performed with the modified Casagrande method [

29,

30].

Soil properties by type:

Laskowice Soil:

pH: 6.1

Texture: Sand 78%, Silt 22%, Clay 0%

Phosphorus (P₂O₅): 14 mg/100 g soil

Potassium (K₂O): 19 mg/100 g soil

Soil moisture: 15.98%

Nitrogen (N): 72-82 kg/ha

Biostrateg Soil:

pH: 7.04

Texture: Sand 22%, Silt 34%, Clay 41%

Phosphorus (P₂O₅): 21.3 mg/100 g soil

Potassium (K₂O): 18.9 mg/100 g soil

Soil moisture: 15.99%

Nitrogen (N): 71-90 kg/ha

Identification and Quantification of Pinocembrin Dihydrochalcone

The identification and quantification of pinocembrin dihydrochalcone after soil dissipation studies and partition coefficient experiment was conducted using liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS) with a triple quadrupole analyzer. Chromatographic separation was achieved using a Shimadzu Prominence UFLC system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), equipped with an LC-30ADXR binary solvent manager, DGU-20A3 degasser, CTO-10ASVP column oven, Kinetex C18 column (2.6 μm particle size, 50 × 3.0 mm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA), SIL-20AXR autosampler, and CBM-20A system controller. Separation was performed under reversed-phase conditions, with a mobile phase of water (A) and acetonitrile (B) in a binary gradient, containing 32% water. The total analysis time was 10 minutes, with a flow rate of 0.40 mL/min, a column temperature of 35°C, and a sample injection volume of 10 µL.

For dihydrochalcone analysis, the LCMS-8030 tandem mass spectrometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) with a triple quadrupole analyzer and an electrospray ionization (ESI) source operating in negative ionization mode was employed. Nitrogen, used as both drying and nebulizing gas, was supplied from pressurized air, with flow rates of 15 L/min and 3 L/min, respectively. The desolvation line was maintained at 250°C, and the heat block at 400°C. Collision-induced dissociation (CID) utilized high-purity argon (99.99%) at a pressure of 230 kPa, with a dwell time of 10 ms. Quantitative data were processed using LabSolution Ver. 5.6 (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) software.

Pinocembrin dihydrochalcone identification and quantification was conducted in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. The dihydrochalcone peak appeared at 0.65 minutes, with an RSD% for retention time below 2%. Negative ionization mode was used for the analysis, with the following transitions selected for dihydrochalcone identification and quantification:

MRM 1: 257.26 > 213.15, dwell time 100 ms, collision energy (CE) = 19

MRM 2: 257.26 > 81.00, dwell time 100 ms, CE = 29

MRM 3: 257.26 > 173, dwell time 100 ms, CE = 35

The optimized method is highly specific and robust. Despite the rapid dissipation of pinocembrin dihydrochalcone, the analyte remained detectable throughout the experiment.

Partition Coefficient

The partition coefficient of dihydrohalcon was determined experimentally based on its sorption into the soil. A silt loam soil, representative of agriculturally used soils in Poland, was selected for the study. The soil composition included 35% sand, 63% silt, and 2% clay, with the following properties: pH(KCl) = 7 .4, total carbon (TC) = 9 .02 g kg-1, total nitrogen (TN) = 0.97 g kg-1, and total organic carbon (TOC) = 7.74 g kg-1. It was free from contamination by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, pesticides, and heavy metals, ensuring reliable results by minimizing interference with the sorption process. The distribution coefficient (KF) was determined by plotting a logarithmic curve fitted to the experimental data. Sorption studies were conducted using test solutions with varying dihydrochalcone concentrations (0.1 mg kg-1, 1 mg kg-1, 2 mg kg-1, 3, mg kg-1, 5 mg kg-1, and 10 mg kg-1), with each concentration measured in duplicate. The relative standard deviation (RSD) was < 2%. A matrix blank and a standard were included in the analysis to assess compound stability during the sorption period. Sorption was carried out over 24h at a constant temperature of 20o C, with 5 ml of the test solution and 1 g of soil shaken on a rotary shaker at 120 rpm. The concentration of dihydrochalcone in the solution was determined using LC-ESI-MS/MS method described above.

DPPH Assay

The DPPH radical scavenging assay was conducted using a modified version of the method developed by Brand-Williams et al. (1995). Pinocembrin dihydrochalcone was initially dissolved in methanol at a concentration of 1.0 mg/mL, then further diluted in water to final concentrations of 0.1, 0.01, 0.001, 0.006, 0.005, 0.004, 0.003, and 0.0001 mg/mL. Each concentration, was transferred to a 96-well plate in eight replicates. An equal volume of 0.2 mM methanolic DPPH• solution was added to each well. Absorbance was measured immediately at 517 nm using a BioTeq μQuant™ Microplate Spectrophotometer, and then recorded every 30 minutes over a 5-hour period during which samples were incubated in the dark at room temperature. Pure water without tested compound mixed with DPPH• solution was used as a control.

The scavenging effect percentage was calculated with the following formula:

where:

AbsDPPH is the absorbance of DPPH• in water

Abssample is the absorbance of the sample with DPPH•

Abscontrol is the absorbance of the sample without DPPH•

From the obtained results, the EC50 value for the water-based solution was calculated using AAT Bioquest, Inc. (2024) [

31].

Reducing Power

The antioxidant activity of dihydrochalcone was further evaluated through its reducing power following a method described by Oyaizu (1986) [

32] and then slightly modified by Oleszek and Kozachok (2018) [

33]. Briefly, 1 ml aliquots of dihydrochalcone, with concentrations ranging from 0 to 250 μg ml-1, were mixed with 2.5 ml of 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.6) and 2.5 ml of 1% potassium (III) ferricyanide. The mixture was incubated at 50°C for 30 min. Next, 2.5 ml of 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added, and the samples were centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting supernatant (2.5 ml) was diluted with 2.5 ml of deionized water and 0.5 ml of 0.1% ferric (III) chloride. The absorbance was measured at 700 nm. The results were expressed as the effective concentration (EC

50), which represents the concentration corresponding to an absorbance of 0.5. Ascorbic acid, strong antioxidant, was used as reference sample.

5. Conclusions

The DPPH assay demonstrated that pinocembrin dihydrochalcone exhibits moderate anti-radical (scavenging) activity. The highest radical scavenging activity occurred at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL, stabilizing after 1.5 hours. Lower concentrations required more time to reach maximum activity, indicating a concentration-dependent scavenging effect. However, in the 300-600 ppm range typical for agricultural applications, the scavenging effect was insufficient to reach the effective concentration (EC50), which was calculated at 0.0096 mg/mL. This suggests that the radical scavenging potential of dihydrochalcone may be limited under practical agricultural conditions, especially at lower concentrations. Furthermore, the dissipation study showed that dihydrochalcone degrades rapidly in soil, following a single first-order (SFO) kinetic model. The DT50 and DT90 values fell within a very short range, indicating rapid breakdown of the compound in soil environments. This rapid dissipation suggests that pinocembrin dihydrochalcone has a limited persistence in soil, which may reduce environmental impact but also affect its potential as a long-term agricultural additive. The biodegradation in soils involves free radicals, so the questions arise about the function of antioxidant properties in such degradation. Polyphenolic compounds with known antioxidant properties are rather considered as relatively resistant to degradation, thanks to its antiradical activity. Nonetheless, the results of present studies proved that the degradation of pinocembrin dihydroflavone is fast.

Together, the findings imply that while dihydrochalcone poses moderate radical scavenging activity, it may not be effective at typical agricultural concentrations. Its rapid dissipation in soil further suggests limited longevity, which could reduce its efficacy over time. Future research might explore methods to enhance its stability and activity in both soil and agricultural settings.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, M.D.-B.; methodology, M.D.-B, M.O.,A.U.-J.,W.K..; software, M.D.-B., M.K.; validation, M.D.-B. and W.K..; formal analysis, M.D.-B, M.O., W.K. .; investigation, M.D.-B.; data curation, M.D.-B.,M.K.,W.K., S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D.-B, M.O., A.U.-J., S.Z., ; writing—review and editing, M.D.-B., S.Z., B.N.; visualization, M.D.-B.; supervision, M.D.-B. and S.Z. ; project administration, M.D.-B..; funding acquisition, M.D.-B., M.O., M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.