Submitted:

15 November 2024

Posted:

15 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

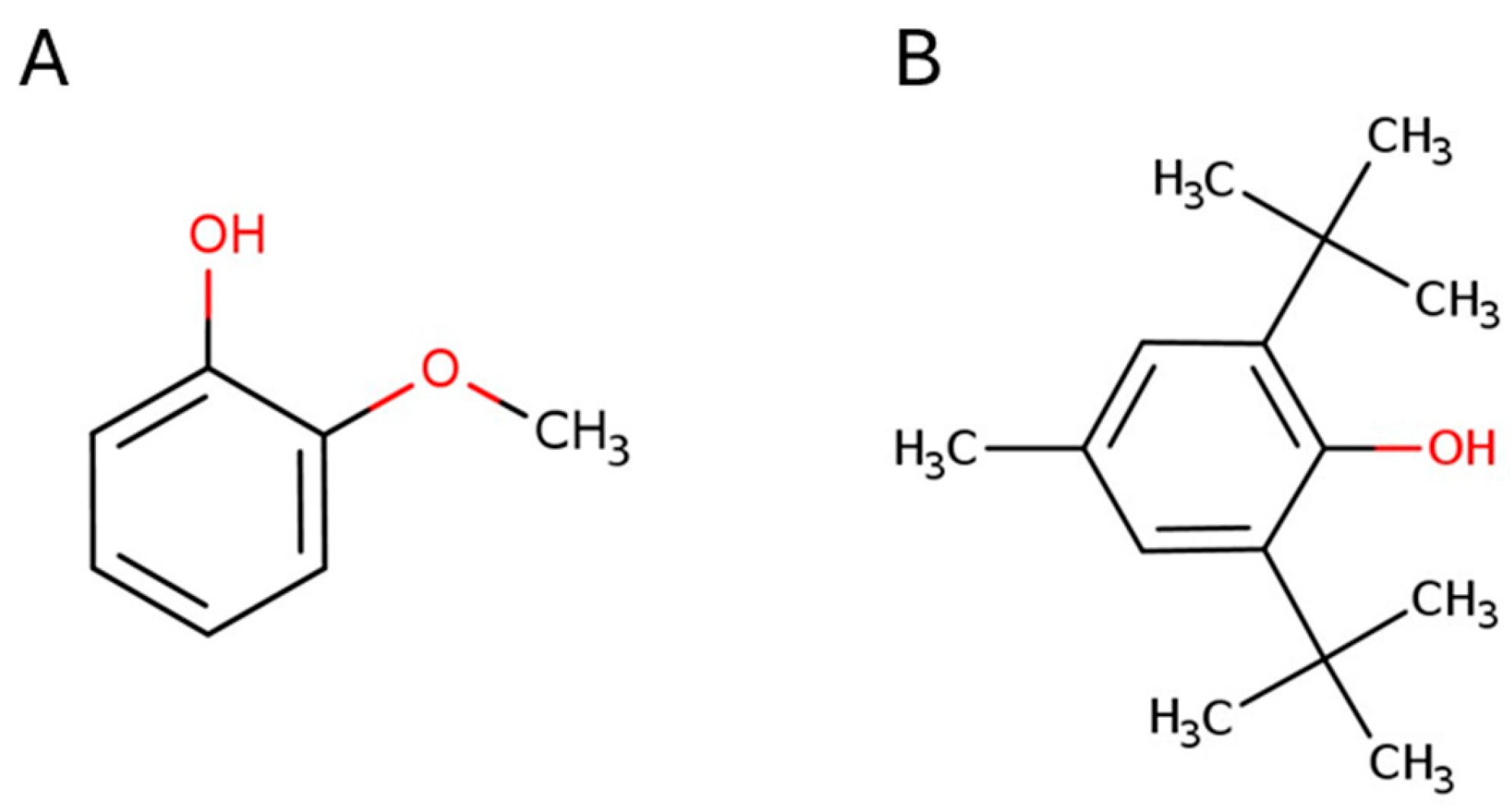

1. Introduction

2. Results

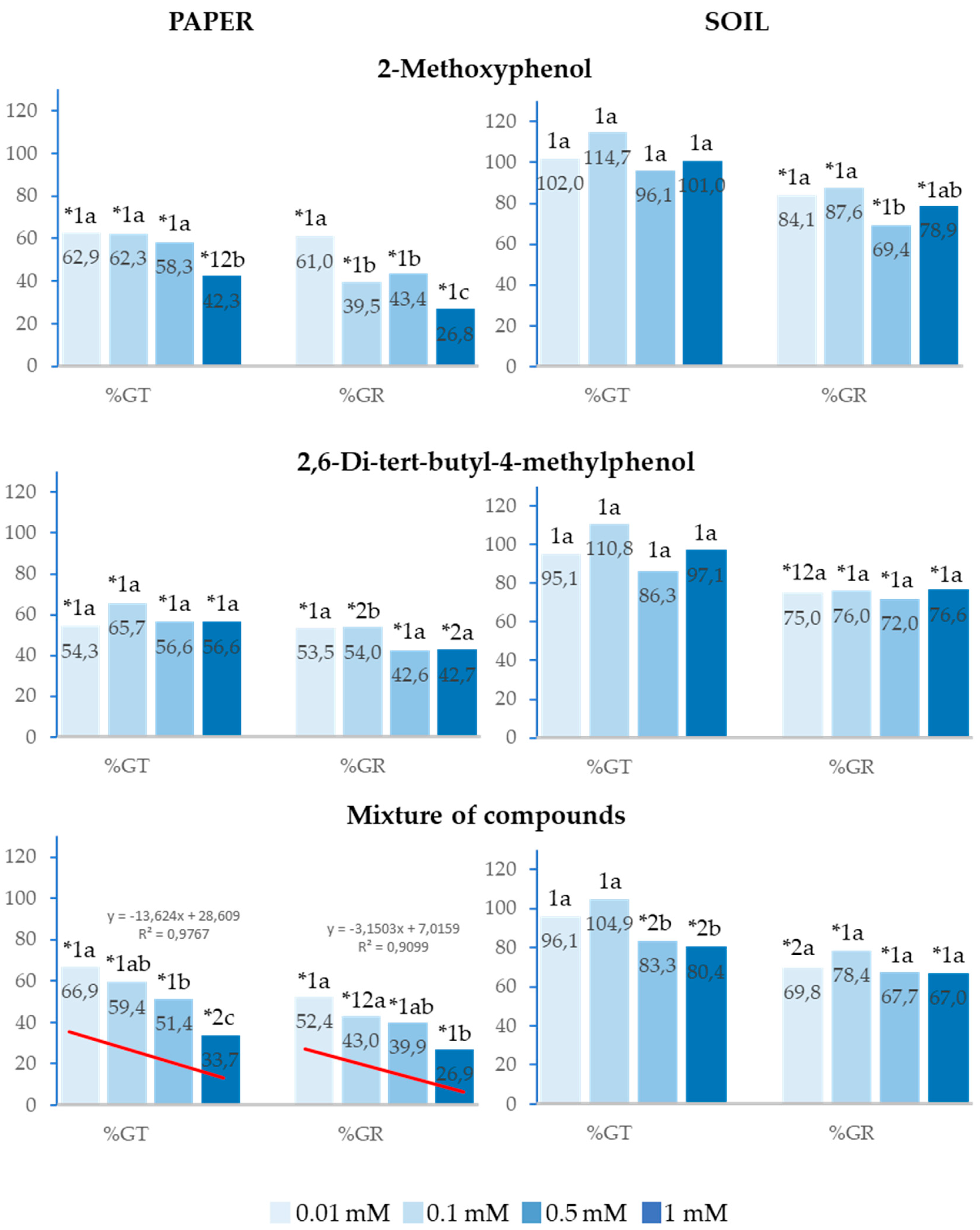

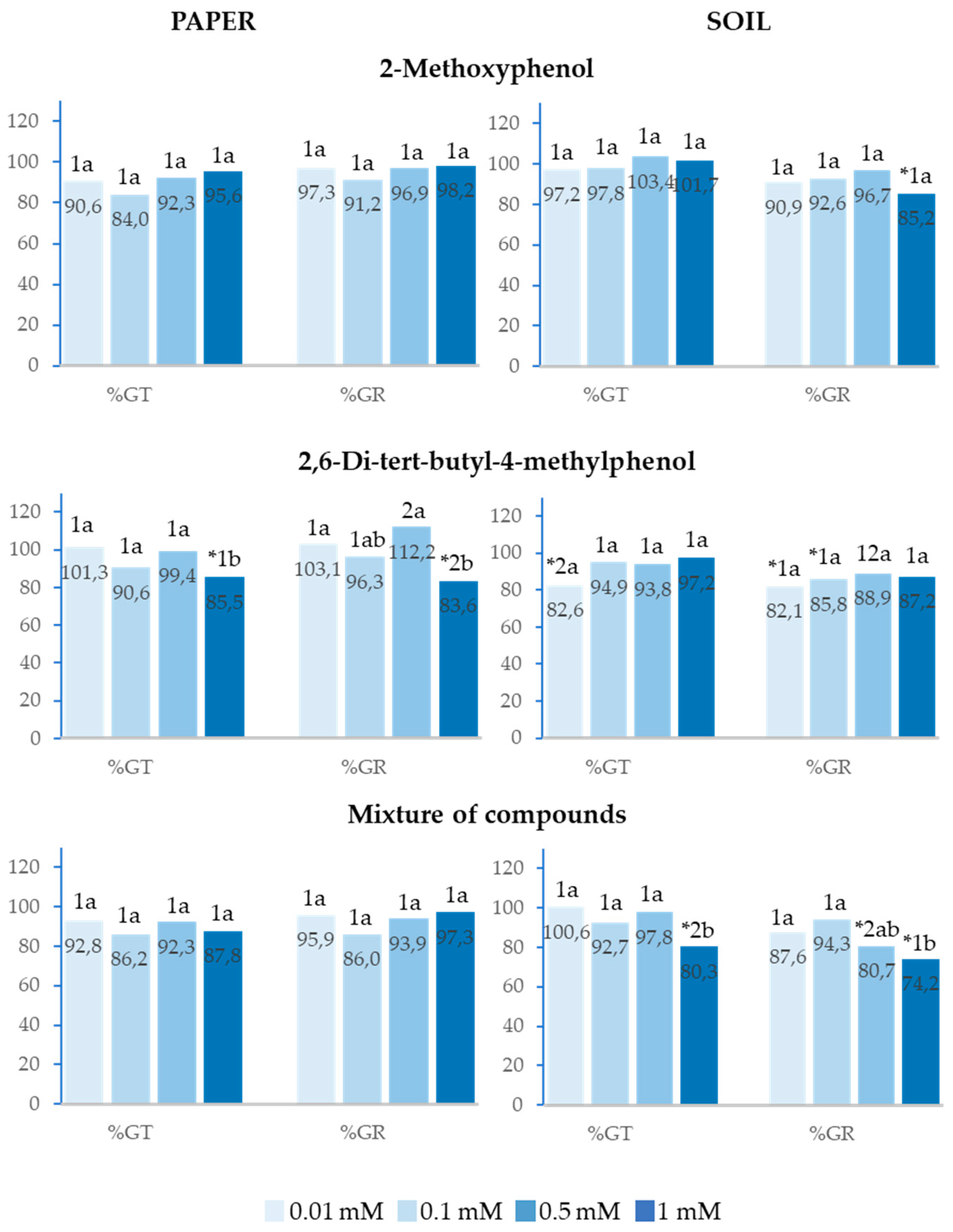

2.1. Effect of 2-Methoxyphenol and 2,6-Di-Tert-Butyl-4-Methylphenol on the Germination of Lactuca sativa L.

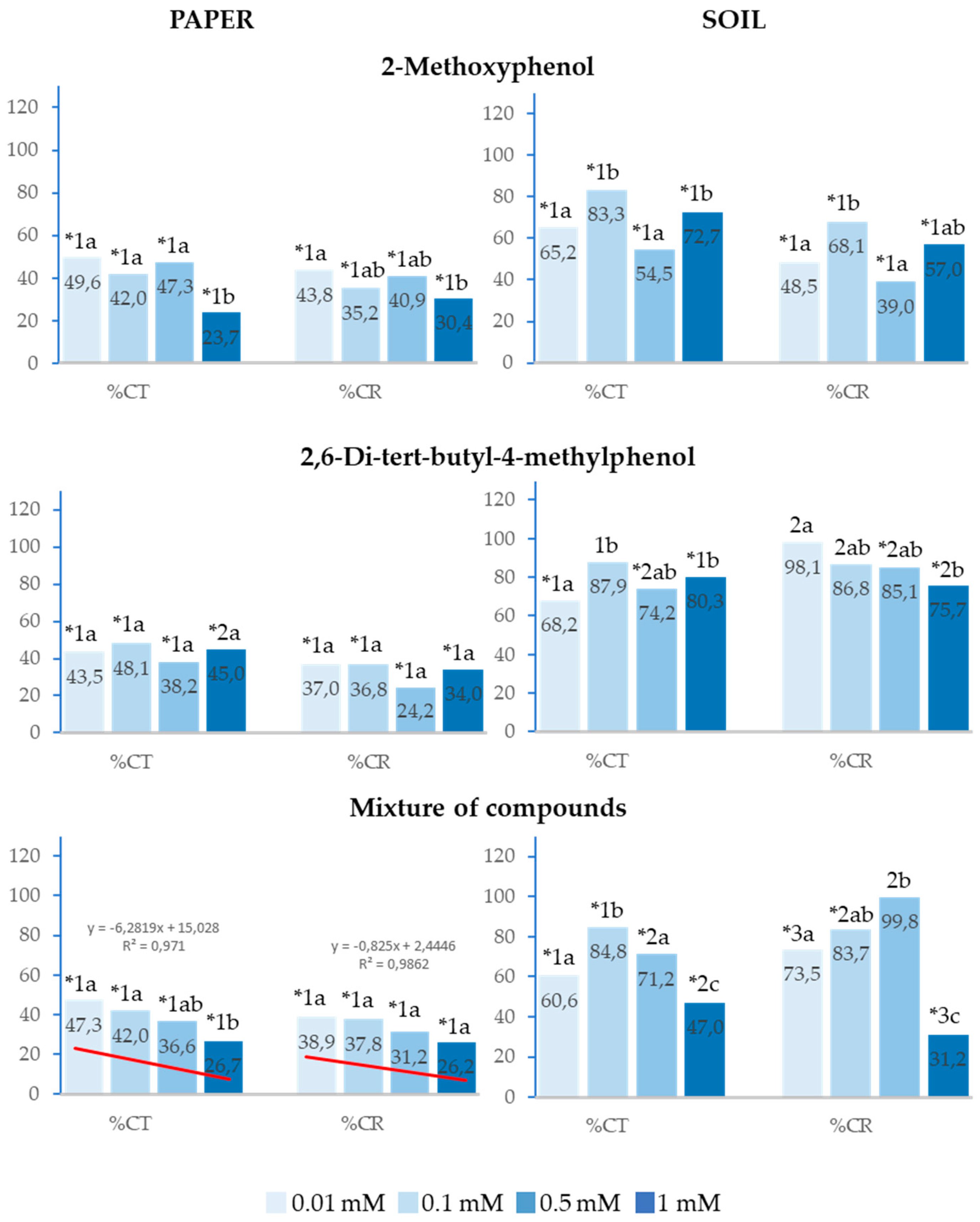

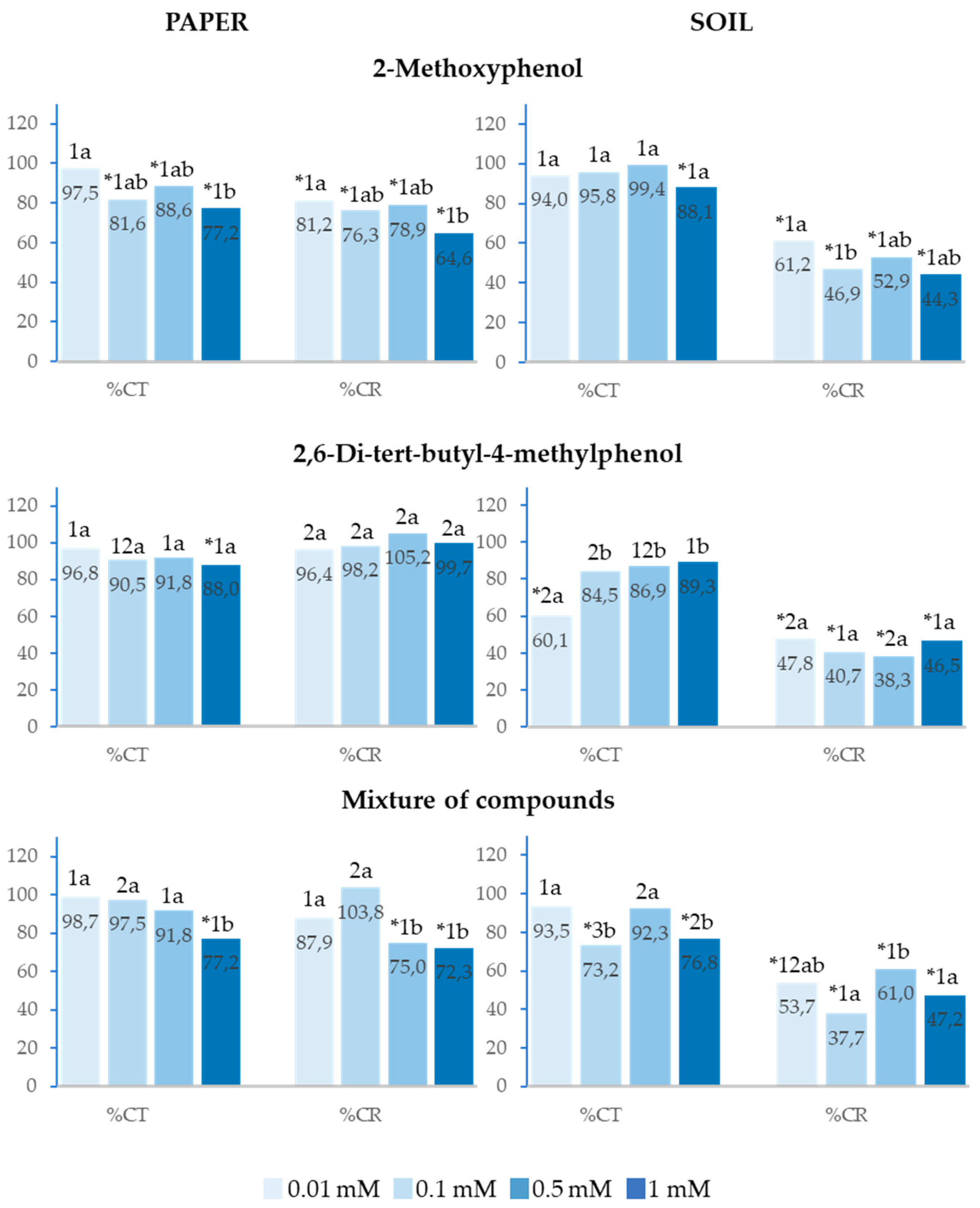

2.2. Effect of 2-Methoxyphenol and 2,6-Di-Tert-Butyl-4-Methylphenol on the Cotyledon Emergence of Lactuca sativa L.

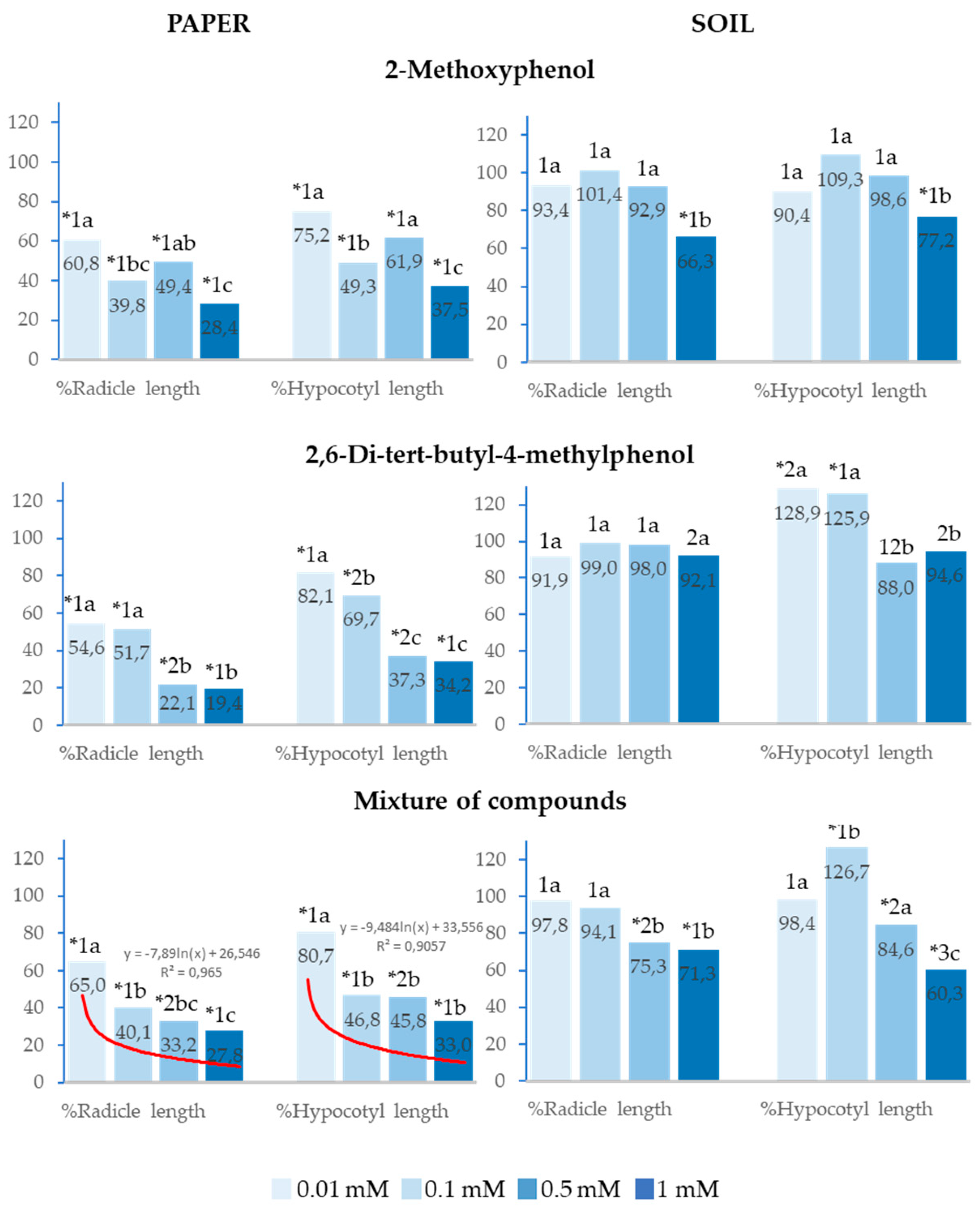

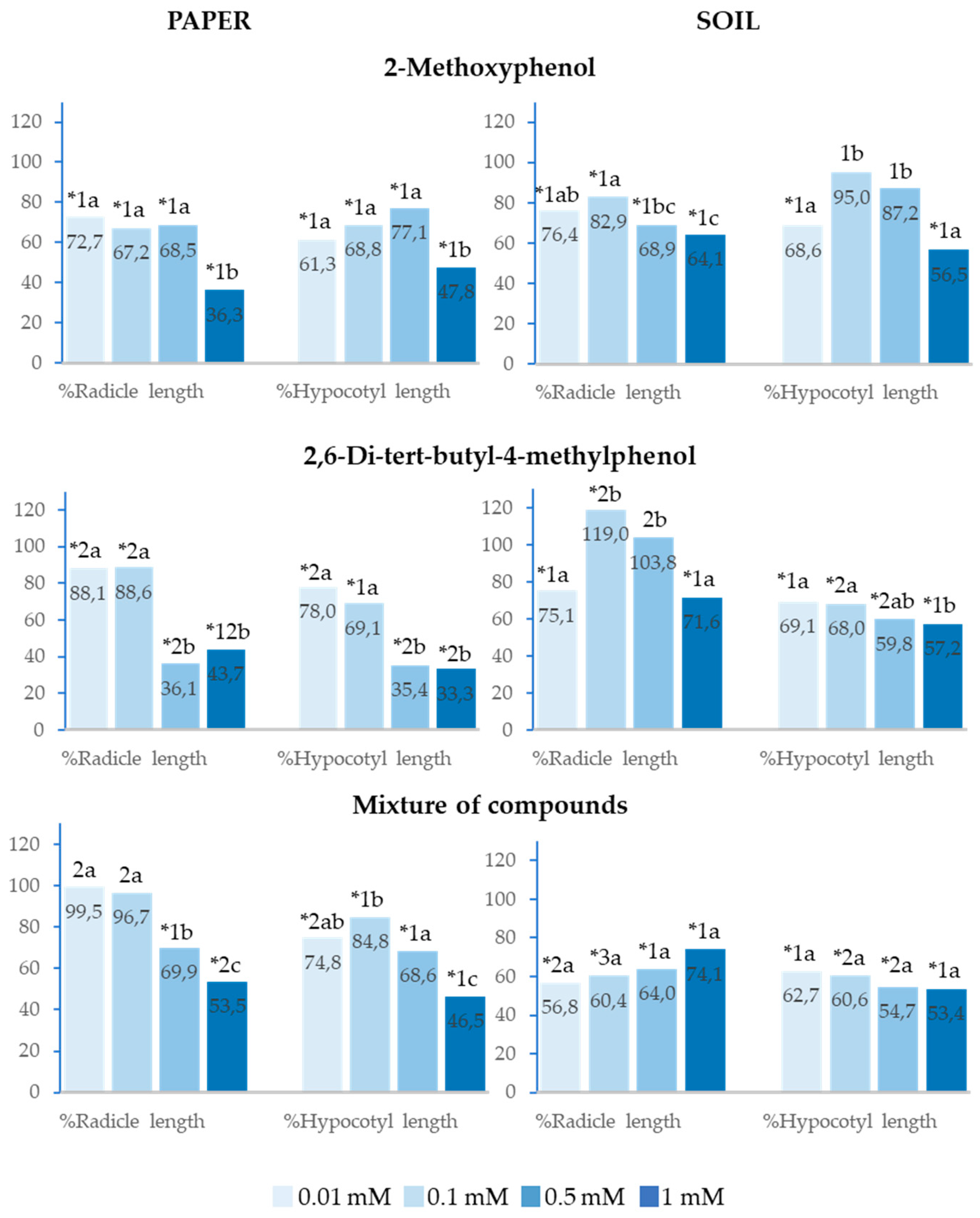

2.3. Effect of 2-Methoxyphenol and 2,6-Di-Tert-Butyl-4-Methylphenol on The Seedling Growth of Lactuca sativa L.

2.4. Effect of 2-Methoxyphenol and 2,6-Di-Tert-Butyl-4-Methylphenol on the Germination of Allium cepa L.

2.5. Effect of 2-Methoxyphenol and 2,6-Di-Tert-Butyl-4-Methylphenol on the Cotyledon Emergence of Allium cepa L.

2.6. Effect of 2-Methoxyphenol and 2,6-Di-Tert-Butyl-4-Methylphenol on the Seedling Growth of Allium cepa L.

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents, Seeds and Substrates

4.2. Phytotoxicity Bioassay

4.3. Measured Indexes to Quantify the Phytotoxic Effect

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, H.P.; Batish, D.R.; Kohli, R.K. Allelopathic Interactions and Allelochemicals: New Possibilities for Sustainable Weed Management. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2003, 22, 239–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, E.L. Allelopathy; Academic Press: Orlando, FL, USA, 1984; p. 422. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, F.; Cheng, Z. Research Progress on the Use of Plant Allelopathy in Agriculture and the Physiological and Ecological 678 Mechanisms of Allelopathy. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 160714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, Y. La utilización de la alelopatía y sus efectos en diferentes cultivos agrícolas. Cultiv. Trop. 2006, 27, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, C.-H.; Li, Z.; Li, F.-L.; Xia, X.-X.; Wang, P. Chemically Mediated Plant–Plant Interactions: Allelopathy and Allelobiosis. Plants 2024, 13, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einhellig, F.A. Mode of Allelochemical Action of Phenolic Compounds. In Allelopathy: Chemistry and mode of action of allelochemicals; Macías, F.A., Galindo, J.C.G., Molinillo, J.M.G.V., Cutler, H.G., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003; pp. 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inderjit. Plant Phenolics in Allelopathy. Bot. Rev. 1996, 62, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiters, A.T. Effects of phenolic acids on germination and early growth of herbaceous woodland plants. J. Chem. Ecol. 1989, 15, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Harun, M.A.; Johnson, J.; Uddin, MN.; Robinson, R.W. Identification and Phytotoxicity Assessment of Phenolic Compounds in Chrysanthemoides monilifera subsp. monilifera (Boneseed). PLoS One 2015, 10, e0139992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tworkoski, T. Herbicide effects of essential oils. Weed Sci. 2002, 50, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vokou, D.; Douvli, P.; Blionis, G.J.; Halley, J.M. Effects of monoterpenoids, acting alone or in pairs, on seed germination and subsequent seedling growth. J. Chem. Ecol. 2003, 29, 2281–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, L.G.; Carpanese, G.; Cioni, P.L.; Morelli, I.; Macchia, M.; Flamini, G. Essential oils from Mediterranean Lamiaceae as weed germination inhibitors. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 6158–6164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macías, F.A.; Molinillo, J.M.; Varela, R.M.; Galindo, J.C. Allelopathy--a natural alternative for weed control. Pest Manag Sci. 2007, 63, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Márquez-García, F.; García-Alonso, D.; Vázquez, F.M. Notes of Changes in Biodiversity in the Exploited Populations of Cistus ladanifer, L., (Cistaceae) from SW Iberian Peninsula. J. Fungi. 2022, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Agra-Coelho, C.; Rosa, M.L.; Moreira, I. Allelopathic effects of Cistus ladanifer L. III Natl. Symp. Herbol. 1980, 1, 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, I.P. Allelopathic potential of Cistus ladanifer L. and Cistus salvifolius L. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Lisboa, Portugal, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, A.S.; Costa, C.T.; Dias, L.S. Allelopathic Plants. XVII. Cistus ladanifer L. Allelopathy. J. 2005, 16, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, N.; Alías, J.C.; Sosa, T. Phytotoxicity of Cistus ladanifer L.: Role of allelopathy. Allelopathy. J. 2016, 38, 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Izquierdo, C.; Serrano-Pérez, P.; Rodríguez-Molina, M.C. Chemical composition, antifungal and phytotoxic activities of Cistus ladanifer L. essential oil and hydrolate. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2022, 45, 102527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdeguer, M.; Blázquez, M.A.; Boira, H. Chemical composition and herbicidal activity of the essential oil from a Cistus ladanifer L. population from Spain. Nat. Prod. Res. Former. Nat. Prod. Lett. 2012, 26, 1602–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazão, D.F.; Martins-Gomes, C.; Steck, J.L.; Keller, J.; Delgado, F.; Gonçalves, J.C.; Bunzel, M.; Pintado, C.M.B.S.; Díaz, T.S.; Silva, A.M. Labdanum Resin from Cistus ladanifer L.: A Natural and Sustainable Ingredient for Skin Care Cosmetics with Relevant Cosmeceutical Bioactivities. Plants 2022, 11, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, N.; Sosa, T.; Alías, J.C.; Escudero, J.C. Identification and effects of interaction phytotoxic compounds from exudate of Cistus ladanifer leaves. J. Chem. Ecol. 2001, 27, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, N.; Sosa, T.; Escudero, J.C. Plant growth inhibiting flavonoids in exudate of Cistus ladanifer and in associated soils. J. Chem. Ecol. 2001, 27, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, N.; Sosa, T.; Alías, J.C.; Escudero, J.C. Germination inhibition of herbs in Cistus ladanifer L. soil: Possible involvement of allelochemicals. Allelopathy. J. 2003, 11, 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Días, A.S.; Dias, L.S.; Pereira, I.P. Activity of water extracts of Cistus ladanifer and Lavandula stoechas in soil on germination and early growth of wheat and Phalaris minor. Allelopathy. J. 2004, 14, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Herranz, J.M.; Farrandis, P.; Copete, M.A.; Duro, E.M.; Zalacaín, A. Effect of allelopathic compounds produced by Cistus ladanifer on germination of 20 Mediterranean taxa. Plant Ecol. 2006, 184, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa, T.; Valares, C.; Alías, J.C.; Chaves, N. Persistence of flavonoids in Cistus ladanifer soils. Plant Soil. 2010, 377, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, P.S.; de Freitas, V.A.P.; Macedo, A.; Silva, G.; Silva, A.M.S. Volatile components of Cistus ladanifer leaves. Flavour Fragr. J. 1999, 14, 300–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, D.; García-Vallejo, M.C. Contribution à la connaissance de l´huile essentielle de Cistus ladaniferus L. Var. Maculatus Dun Ciste commun (jara) d´Espagne. Parfumerie Cosmétique Savons 1969, 12, 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- Simon-Fuentes, A.; Sendra, J.M.; Cuñat, P. Neutral volátiles of Cistus ladaniferus L. essential oil. An. R. Soc. Esp. Quím. 1987, 83, 201–204. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (2024). PubChem Compound Summary for CID 460, Guaiacol. Retrieved October 24, 2024 from https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Guaiacol.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (2024). PubChem Compound Summary for CID 31404, Butylated Hydroxytoluene. Retrieved October 24, 2024 from https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/2_6-ditert-butyl-4-methylphenol.

- Kato-Noguchi, H.; Seki, T.; Shigemori, H. Allelopathy and allelopathic substance in the moss Rhynchostegium pallidifolium. J. Plant Phys. 2010, 167, 468–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einhellig, F.A.; Schon, M.K.; Rasmussen, J.A. Synergistic effects of four cinnamic acid compounds on grain sorghom. Plant Growth Regul. 1983, 1, 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Batish, D.R.; Singh, H.P.; Kaur, S.; Kohli, R.K.; Yadav, S.S. Caffeic acid affects early growth, and morphogenetic response of hypocotyl cuttings of mung bean (Phaseolus aureus). J. Plant Phys. 2008, 165, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Requesón, E.; Osuna, D.; del Rosario Santiago, A.; Sosa, T. Evaluation of the Activity of Estragole and 2-Isopropylphenol, Phenolic Compounds Present in Cistus ladanifer. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.H. Characterization of the mechanisms of allelopathy: Modeling and experimental approaches. In Allelopathy: Organisms, Processes, and Applications; Inderjit, Dakshini, K.M.M., Einhellig, F.A., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, WA, USA, 1995; pp. 132–141. [Google Scholar]

- Einhellig, F.A.; Leather, G.R.; Hobbs, L.L. Use of Lemna minor L. as a bioassay in allelopathy. J. Chem. Ecol. 1985, 11, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.H.; Inoue, M.; Nishimura, H.; Mizutani, J.; Tsuzuki, E. Interactions of trans-cinnamic acid, its related phenolic allelochemicals, and abscisic acid in seedling growth and seed germination of lettuce. J. Chem. Ecol. 1993, 19, 1775–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, G.R. Allelochemicals: Role in Agriculture and Forestry. ACS Symposium Series 330; American Chemical Society: Washington, WA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Colín, M.; Hernandez-Caballero, I.; Infante, C.; Gago, I.; García-Muñoz, J.; Sosa, T. Evaluation of Propiophenone, 4-Methylacetophenone and 2',4'-Dimethylacetophenone as Phytotoxic Compounds of Labdanum Oil from Cistus ladanifer L. Plants 2023, 12, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dudai, N.; Poljakoff-Mayber, A.; Mayer, A.M.; Putievsky, E.; Lerner, H.R. Essential oils as allelochemicals and their potential use as bioherbicides. J. Chem. Ecol. 1999, 25, 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdeguer, M.; Sánchez-Moreiras, A.M.; Araniti, F. Phytotoxic effects and mechanism of action of essential oils and terpenoids. Plants 2020, 9, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tena, C.; del Rosario Santiago, A.; Osuna, D.; Sosa, T. Phytotoxic Activity of p-Cresol, 2-Phenylethanol and 3-Phenyl-1-Propanol, Phenolic Compounds Present in Cistus ladanifer L. Plants 2021, 10, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li Liu, D.; An, M.; Johnson, I.R.; Lovett, J.V. Mathematical modeling of allelopathy. III. A model for curve-fitting allelochemical dose responses. Nonlinearity Biol. Toxicol. Med. 2003, 1, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, E.J. Paradigm lost, paradigm found: the re-emergence of hormesis as a fundamental dose response model in the toxicological sciences. Environ. Pollut. 2005, 138, 378–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malato-Belíz, J.; Escudero, J.C.; Buyolo, T. Application of Traditional Indices and of Diversity to an Ecotonal Area of Different Biomes. In The State of the Art in Vegetation Science; International Association for Vegetation Science (IAVS): Toledo, Spain, 1992; Volume 75. [Google Scholar]

- Wacker, T.; Safir, G.R.; Stephens, C.T. Effects of ferulic acid on Glomus fasciculatum and associated effects on phosphorus uptake an growth of asparagus (Asparagus officinalis L.). J. Chem. Ecol. 1990, 16, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.H.; Wang, Q.; Ruan, X.; Pan, C.D.; Jiang, D.A. Phenolics and plant allelopathy. Molecules 2010, 15, 8933–8952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baziramakenga, R.; Simard, R. R.; Leroux, G. D. Effects of Benzoic and Cinnamic Acid on Growth, Chlorophyll and Mineral Contents of Soybean. J. Chem. Ecol. 1994, 20, 2821–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, C.H. The role of chemical inhibition (allelopathy) in vegetation composition. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 1966, 93, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, A. Estudio de sustancias de crecimiento aislados de Ericacinerea L. Acta Científica Compostel 1971, 8, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Tukey, H.B. Leaching of metabolites from above grown plant parts and its implication. Bull Torrey. Bot. Club 1966, 93, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Moral, R.; Muller, C.H. Effects of Eucalyptus camaldulensis. Am. Midl. Nat. 1975, 83, 254–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einhelling, F.A. Allelopathy: Current Status and Future Goals. In Allelopathy: Organisms, Processes, and Applications; Inderjit, K.M., Dakshini, M., Einhelling, F.A., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Rabotnov, T.A. On the allelopathy in the phytocenosis. Izo Akad Nauk Ser Biol. 1974, 6, 811–820. [Google Scholar]

- An, M.; Pratley, J.; Haig, T. Allelopathy: From Concept to Reality. In Proceedings of the 9th Australian Agronomy Conference, Wagga Wagga, Australia, 20–23 July 1998; pp. 563–566. [Google Scholar]

- Lehman, M.E.; Blum, U. Influence of pretreatment stresses on inhibitory effects of ferulic acid, an allelopathic phenolic acid. J. Chem. Ecol. 1999, 25, 1517–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, P.C. Inderjit, Challenges and opportunities in implementing allelopathy for natural weed management. Crop Prot. 2003, 22, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.J.; Xia, Z.C.; Kong, C.H.; Xu, X.H. Mobility and microbial activity of allelochemicals in soil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 5072–5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.Y.; Kong, C.H.; Wang, P.; Huang, Q.L. Temporal variation of soil friedelin and microbial community under different land uses in a long-term agroecosystem. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 69, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Shao, H. Changes in the soil fungal community mediated by a Peganum harmala allelochemical. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 911836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inderjit. Soil microorganisms: An important determinant of allelopathic activity. Plant Soil 2005, 274, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspersen, S.; Alsanius, B.W.; Sundin, P.; Jensen, P. Bacterial amelioration of ferulic acid toxicity to hydroponically grown lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Soil Biol Biochem 2000, 32, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.H.; Wang, P.; Gu, Y.; Xu, X.H.; Wang, M.L. The fate and impact on microorganisms of rice allelochemicals in paddy soil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 5043–5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorentino, A.; Gentili, A.; Isidori, M.; Monaco, P.; Nardelli, A.; Parrella, A.; Temussi, F. Environmental effects caused by olive mill wastewaters: toxicity comparison of low-molecular-weight phenol components. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 1005–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Baerson, S.R.; Wang, M.; Bajsa-Hirschel, J.; Rimando, A.M.; Wang, X; Nanayakkara, N.P.D.; Noonan, B.P.; Fromm, M.E.; Dayan, F.E.; Khan, I.A.; Duke, S.O. A cytochrome P450 CYP71 enzyme expressed in Sorghum bicolor root hair cells participates in the biosynthesis of the benzoquinone allelochemical sorgoleone. New Phytol. 2018, 218, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W. Literature review on higher plants for toxicity testing. Water Air Soil Poll. 1991, 59, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiapusio, G.; Sánchez, M.A.; Reigosa, J.M.; González, L.; Pellissier, F. Do germination indices adequately reflect allelochemical effects on the germination process? J. Chem. Ecol. 1997, 23, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaderlund, A.; Zackrisson, O.; Nilsson, M.C. Effects of bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) litter on seed germination and early seedling growth of four boreal tree species. J. Chem. Ecol. 1996, 22, 973–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).