Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

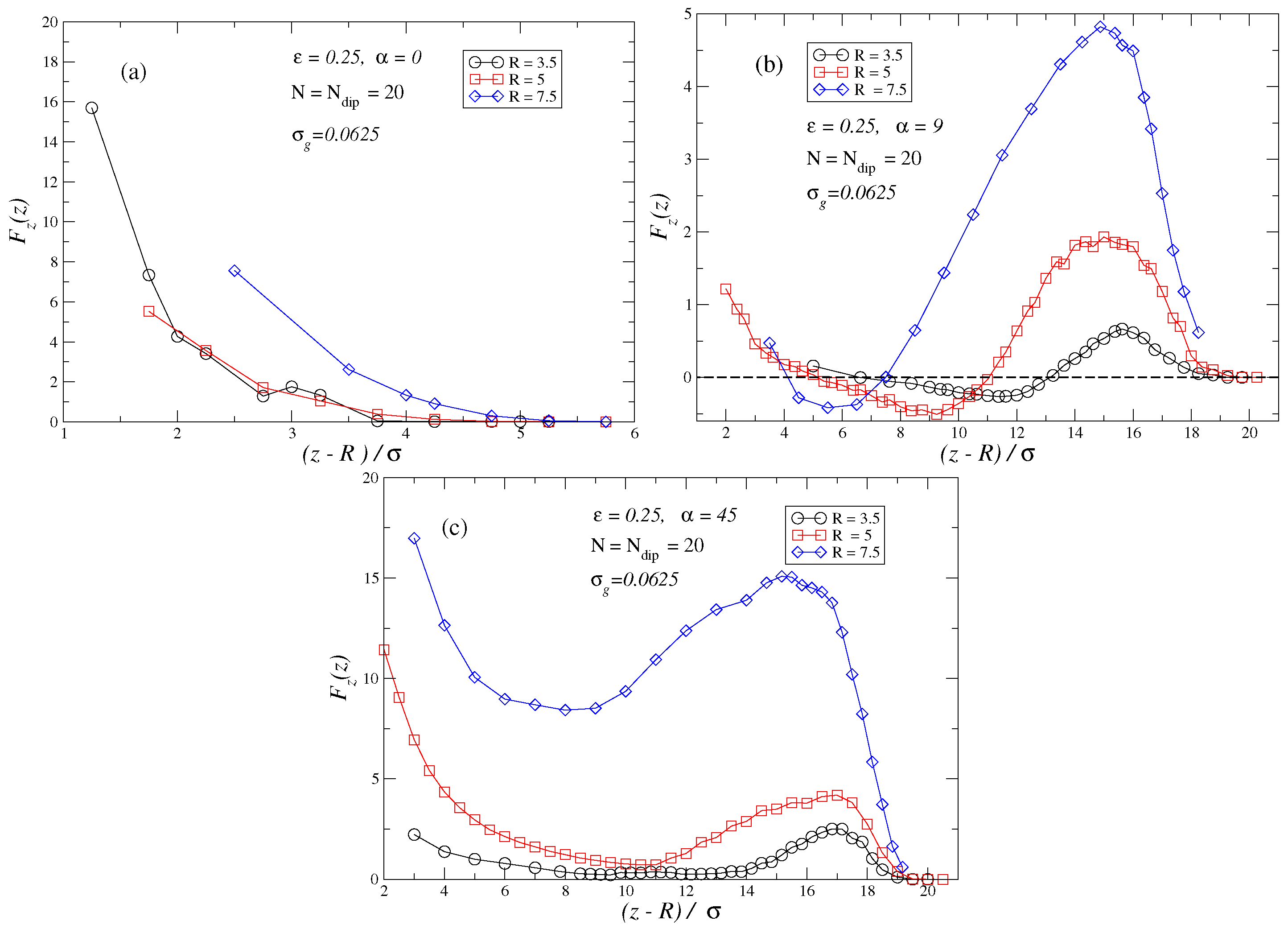

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

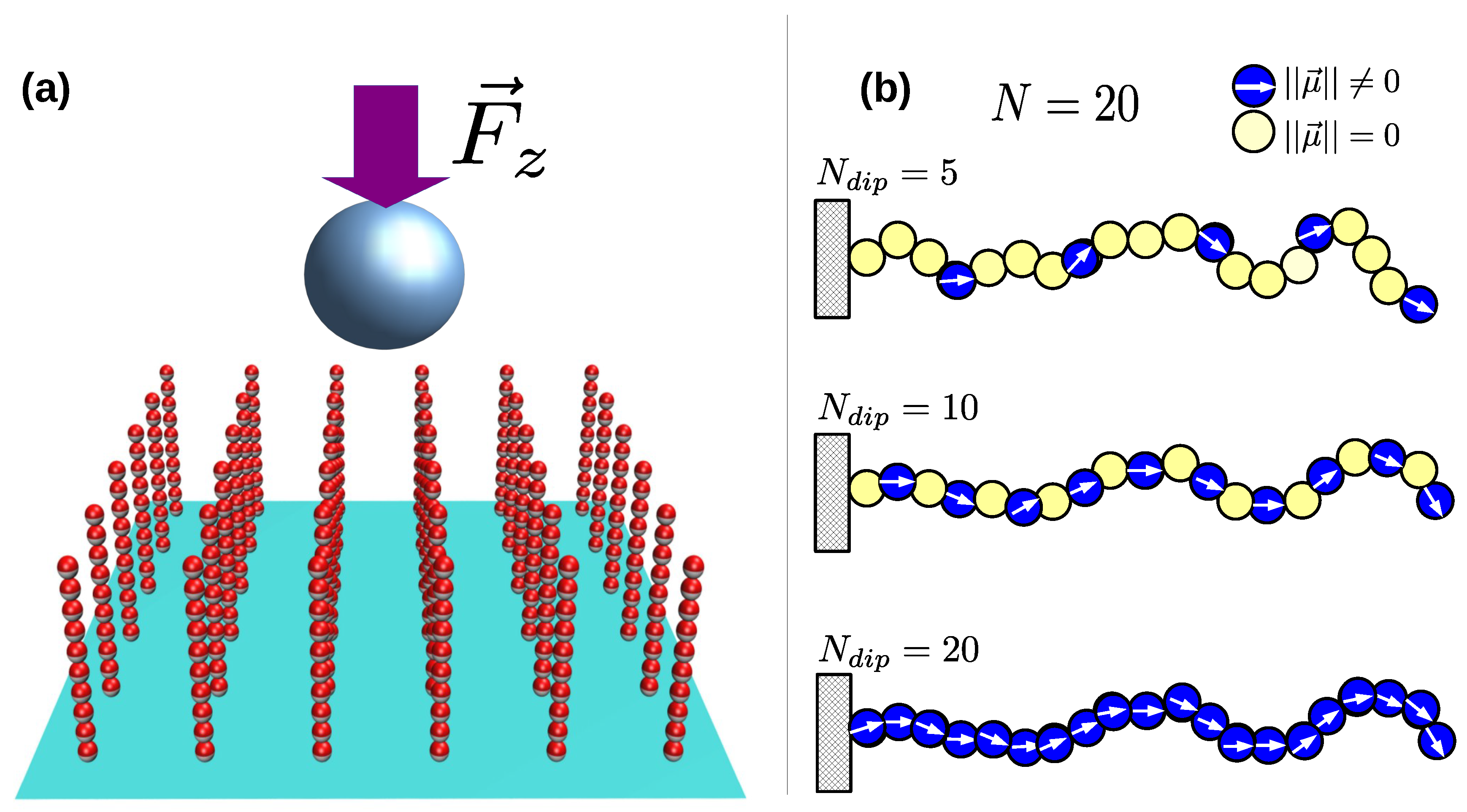

2. Numerical Method

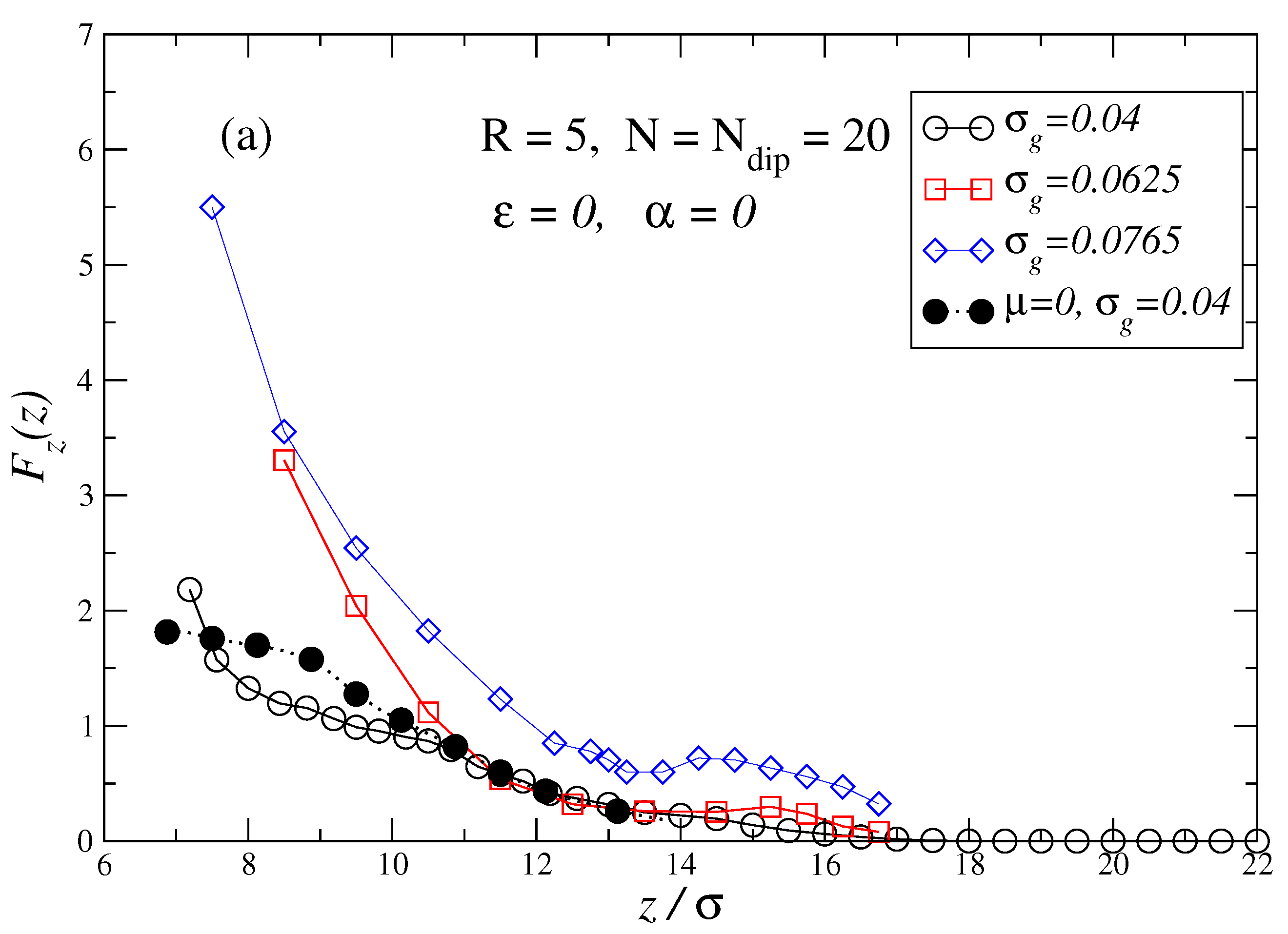

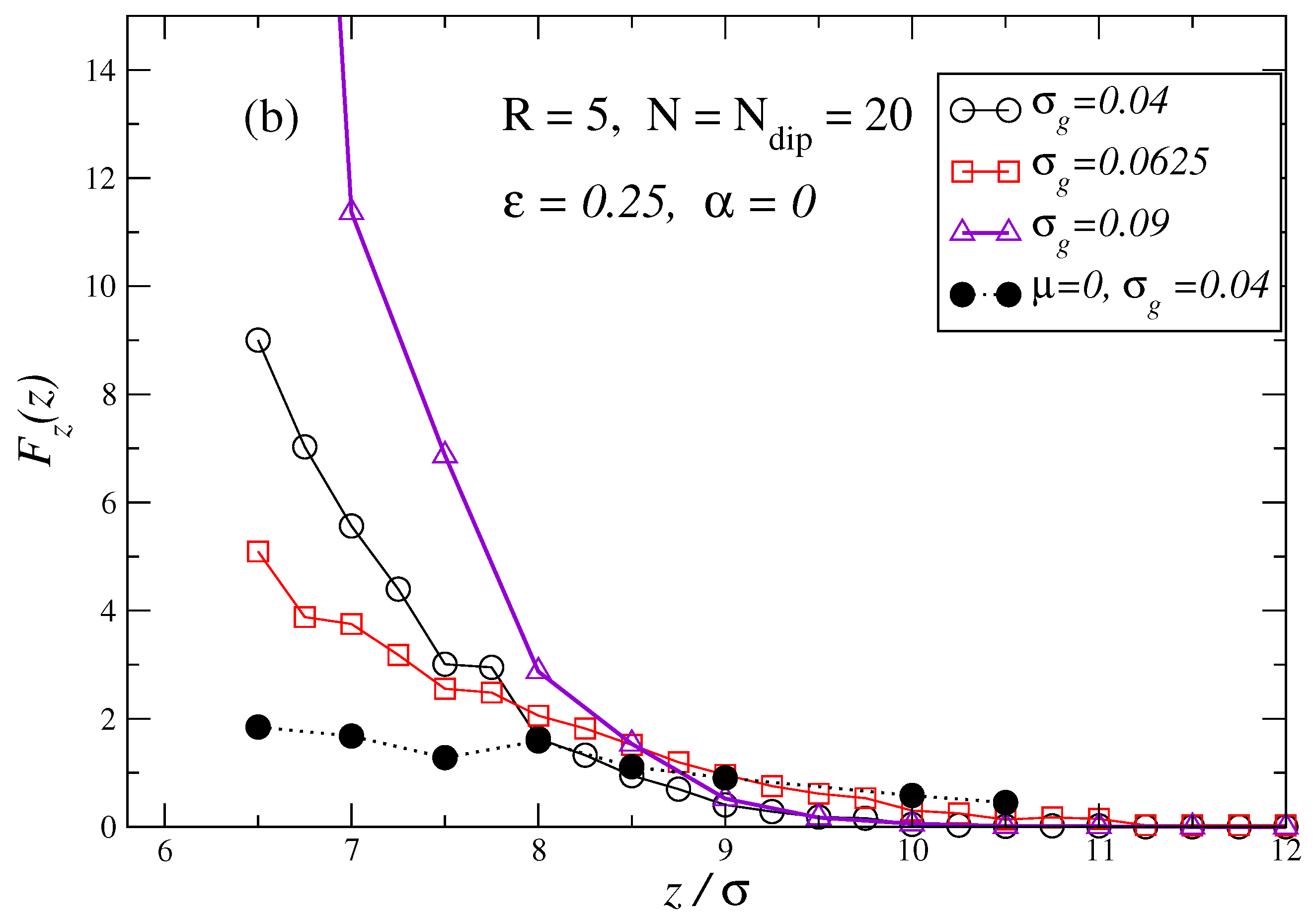

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Li, B.; Sheng, W. Surface Functionalization with Polymer Brushes via Surface-Initiated Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization: Synthesis, Applications, and Current Challenges. LANGMUIR 2024, 40, 5571–5589. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, H. Polymer Brushes and Surface Nanostructures: Molecular Design, Precise Synthesis, and Self-Assembly. LANGMUIR 2024, 40, 2439–2464. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wei, C.; Zhao, T. Molecular brushes based on poly(amino acid)s: synthesis, structures, and applications. JOURNAL OF POLYMER SCIENCE 2024, 62, 480–491. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wei, Q.; Sheng, W.; Yu, B.; Zhou, F.; Li, B. Driving Polymer Brushes from Synthesis to Functioning. ANGEWANDTE CHEMIE-INTERNATIONAL EDITION 2023. [CrossRef]

- Metze, F.K.; Klok, H.A. Supramolecular Polymer Brushes. ACS POLYMERS AU 2023, 3, 228–238. [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.Q.; Zhu, W.; Guo, W.J.; Li, Q.; Ma, S.; Bucher, C.; Liu, B.; Ji, X.; Huang, F.; Sessler, J.L. Supramolecular polymers: Recent advances based on the types of underlying interactions. PROGRESS IN POLYMER SCIENCE 2023, 137. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, H. Polymer brush-based nanostructures: from surface self-assembly to surface co-assembly. SOFT MATTER 2022, 18, 5138–5152. [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, N. Brush-like polymers: design, synthesis and applications. CHEMICAL COMMUNICATIONS 2021, 57, 10484–10499. [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wang, X.; Yan, S.; Dong, A.; Luan, S.; Yin, J. Advances in design and biomedical application of hierarchical polymer brushes. PROGRESS IN POLYMER SCIENCE 2021, 118. [CrossRef]

- Reese, C.J.; Boyes, S.G. New methods in polymer brush synthesis: Non-vinyl-based semiflexible and rigid-rod polymer brushes. PROGRESS IN POLYMER SCIENCE 2021, 114. [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zhang, X.; Yu, B.; Zhou, F. Brushing up functional materials. NPG ASIA MATERIALS 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Conrad, J.C.; Robertson, M.L. Towards mimicking biological function with responsive surface-grafted polymer brushes. Current Opinion in Solid State and Materials Science 2019, 23, 1–12. Active and adaptive soft matter. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Billing, M.; Ruths, M.; Klok, H.A.; Yu, J. Structure and Functionality of Polyelectrolyte Brushes: A Surface Force Perspective. Chemistry – An Asian Journal 2018, 13, 3411–3436, [https://aces.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/asia.201800920]. [CrossRef]

- Welch, M.E.; Ober, C.K. Responsive and patterned polymer brushes. JOURNAL OF POLYMER SCIENCE PART B-POLYMER PHYSICS 2013, 51, 1457–1472. [CrossRef]

- Lokesh, M.G.; Tiwari, A.K. A concise review on polymer brushes and its interaction with surfactants: An approach towards smart materials. JOURNAL OF MOLECULAR LIQUIDS 2024, 407. [CrossRef]

- Conrad, J.C.; Robertson, M.L. Shaping the Structure and Response of Surface-Grafted Polymer Brushes via the Molecular Weight Distribution. JACS AU 2023. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, F. Shear-Stable Polymer Brush Surfaces. LANGMUIR 2023, 39, 37–44. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, R.; Duval, J.F.L.; Werner, C.; Sterling, J.D. Quantitative insights into electrostatics and structure of polymer brushes from microslit electrokinetic experiments and advanced modelling of interfacial electrohydrodynamics. CURRENT OPINION IN COLLOID & INTERFACE SCIENCE 2022, 59. [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, M. Weak polyelectrolyte brushes. SOFT MATTER 2022, 18, 2500–2511. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Billing, M.; Ruths, M.; Klok, H.A.; Yu, J. Structure and Functionality of Polyelectrolyte Brushes: A Surface Force Perspective. CHEMISTRY-AN ASIAN JOURNAL 2018, 13, 3411–3436. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jing, B.; Zhu, Y. Molecule Motion at Polymer Brush Interfaces from Single-Molecule Experimental Perspectives. JOURNAL OF POLYMER SCIENCE PART B-POLYMER PHYSICS 2014, 52, 85–103. [CrossRef]

- Reznik, C.; Landes, C.F. Transport in Supported Polyelectrolyte Brushes. ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 2012, 45, 1927–1935. [CrossRef]

- Ballauff, M. Spherical polyelectrolyte brushes. PROGRESS IN POLYMER SCIENCE 2007, 32, 1135–1151. [CrossRef]

- Ballauff, M.; Borisov, O. Polyelectrolyte brushes. CURRENT OPINION IN COLLOID & INTERFACE SCIENCE 2006, 11, 316–323. [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Banik, M.; Chen, G.; Sinha, S.; Mukherjee, R. Polyelectrolyte brushes: theory, modelling, synthesis and applications. SOFT MATTER 2015, 11, 8550–8583. [CrossRef]

- Mikhailov, V, I.; Darinskii, A.A.; Birshtein, T.M. Bending Rigidity of Branched Polymer Brushes with Finite Membrane Thickness. POLYMER SCIENCE SERIES C 2022, 64, 110–122. [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Bu, X.; Zhang, X. Single Chain Mean-Field Theory Study on Responsive Behavior of Semiflexible Polymer Brush. MATERIALS 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Klushin, L.I.; Skvortsov, A.M.; Qi, S.; Schmid, F. Polydisperse Brush with the Linear Density Profile. POLYMER SCIENCE SERIES C 2018, 60, 84–94. [CrossRef]

- Zhulina, E.B.; Borisov, O.V. Dendritic polyelectrolyte brushes. POLYMER SCIENCE SERIES C 2017, 59, 106–118. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, B.H. Self-assembly of block copolymers grafted onto a flat substrate: Recent progress in theory and simulations. CHINESE PHYSICS B 2016, 25. [CrossRef]

- Binder, K.; Milchev, A. Polymer brushes on flat and curved surfaces: How computer simulations can help to test theories and to interpret experiments. JOURNAL OF POLYMER SCIENCE PART B-POLYMER PHYSICS 2012, 50, 1515–1555. [CrossRef]

- Tagliazucchi, M.; Szleifer, I. Stimuli-responsive polymers grafted to nanopores and other nano-curved surfaces: structure, chemical equilibrium and transport. SOFT MATTER 2012, 8, 7292–7305. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Cao, D.; Wu, J. Density functional theory for predicting polymeric forces against surface fouling. SOFT MATTER 2010, 6, 4631–4646. [CrossRef]

- Naji, A.; Seidel, C.; Netz, R.R. Theoretical approaches to neutral and charged polymer brushes. In SURFACE- INITIATED POLYMERIZATION II; Jordan, R., Ed.; SPRINGER-VERLAG BERLIN: HEIDELBERGER PLATZ 3, D-14197 BERLIN, GERMANY, 2006; Vol. 198, Advances in Polymer Science, pp. 149–183. [CrossRef]

- Rühe, J.; Ballauff, M.; Biesalski, M.; Dziezok, P.; Gröhn, F.; Johannsmann, D.; Houbenov, N.; Hugenberg, N.; Konradi, R.; Minko, S.; Motornov, M.; Netz, R.; Schmidt, M.; Seidel, C.; Stamm, M.; Stephan, T.; Usov, D.; Zhang, H. Polyelectrolyte brushes. In POLYELECTROLYTES WITH DEFINED MOLECULAR ARCHITECTURE I; Schmidt, M., Ed.; SPRINGER-VERLAG BERLIN: HEIDELBERGER PLATZ 3, D-14197 BERLIN, GERMANY, 2004; Vol. 165, Advances in Polymer Science, pp. 79–150. [CrossRef]

- Vorsmann, C.F.; Del Galdo, S.; Capone, B.; Locatelli, E. Colloidal adsorption in planar polymeric brushes. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 816–825. [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, D.; Milchev, A.; Binder, K. Polymer brushes on flat and curved substrates: Scaling concepts and computer simulations. Macromolecular symposia. Wiley Online Library, 2007, Vol. 252, pp. 47–57.

- Kreer, T. Polymer-brush lubrication: a review of recent theoretical advances. SOFT MATTER 2016, 12, 3479–3501. [CrossRef]

- Larin, D.E.; Govorun, E.N. Surfactant-Induced Patterns in Polymer Brushes. Langmuir 2017, 33, 8545–8552. PMID: 28759241. [CrossRef]

- Ishraaq, R.; Das, S. All-atom molecular dynamics simulations of polymer and polyelectrolyte brushes. CHEMICAL COMMUNICATIONS 2024, 60, 6093–6129. [CrossRef]

- Abdelbar, M.A.A.; Ewen, J.P.P.; Dini, D.; Angioletti-Uberti, S. Polymer brushes for friction control: Contributions of molecular simulations. BIOINTERPHASES 2023, 18. [CrossRef]

- Binder, K.; Kreer, T.; Milchev, A. Polymer brushes under flow and in other out-of-equilibrium conditions. SOFT MATTER 2011, 7, 7159–7172. [CrossRef]

- Descas, R.; Sommer, J.U.; Blumen, A. Grafted Polymer Chains Interacting with Substrates: Computer Simulations and scaling. MACROMOLECULAR THEORY AND SIMULATIONS 2008, 17, 429–453. [CrossRef]

- Viduna, D.; Limpouchová, Z.; Procházka, K. Monte Carlo simulation of polymer brushes in narrow pores. JOURNAL OF CHEMICAL PHYSICS 2001, 115, 7309–7318. [CrossRef]

- Grest, G. Normal and shear forces between polymer brushes. In POLYMERS IN CONFINED ENVIRONMENTS; Granick, S., Ed.; SPRINGER-VERLAG BERLIN: HEIDELBERGER PLATZ 3, D-14197 BERLIN, GERMANY, 1999; Vol. 138, Advances in Polymer Science, pp. 149–183.

- Grest, G. Computer simulations of shear and friction between polymer brushes. CURRENT OPINION IN COLLOID & INTERFACE SCIENCE 1997, 2, 271–277. [CrossRef]

- Mikhailov, I.V.; Amoskov, V.M.; Darinskii, A.A.; Birshtein, T.M. The Structure of Dipolar Polymer Brushes and Their Interaction in the Melt. Impact of Chain Stiffness. Polymers 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Birshtein, T.; Polotsky, A.; Glova, A.; Amoskov, V.; Mercurieva, A.; Nazarychev, V.; Lyulin, S. How to fold back grafted chains in dipolar brushes. Polymer 2018, 147, 213–224. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Okrugin, B.M.; Richter, R.P.; Leermakers, F.A.M.; Neelov, I.M.; Zhulina, E.B.; Borisov, O.V. Electroresponsive Polyelectrolyte Brushes Studied by Self-Consistent Field Theory. Polymers 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Lukiev, I.V.; Mogelnitskaya, Y.A.; Mikhailov, I.V.; Darinskii, A.A. Chains Stiffness Effect on the Vertical Segregation of Mixed Polymer Brushes in Selective Solvent. Polymers 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Kielbasa, A.; Kowalczyk, K.; Chajec-Gierczak, K.; Bala, J.; Zapotoczny, S. Applications of surface-grafted polymer brushes with various architectures. POLYMERS FOR ADVANCED TECHNOLOGIES 2024, 35. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.L.; Cordero, R.; Tran, H.; Ober, C.K. 50th Anniversary Perspective: Polymer Brushes: Novel Surfaces for Future Materials. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 4089–4113. [CrossRef]

- Su, N. Advances and Prospects in the Study of Spherical Polyelectrolyte Brushes as a Dopant for Conducting Polymers. MOLECULES 2024, 29. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, S.; Diekmann, J.; Greve, D.; Thiele, U. Drops on Polymer Brushes: Advances in Thin-Film Modeling of Adaptive Substrates. LANGMUIR 2024, 40, 4001–4021. [CrossRef]

- Atif, M.; Balasini, A. Mixed polymer brushes for controlled protein adsorption: state of the art and future prospective. MATERIALS ADVANCES 2024, 5, 1420–1439. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tang, K.; Wang, M.; Shen, C.; Deng, R. Recent Progress in Janus Nano-Objects with Asymmetric Polymer Brushes. CHEMISTRY-AN ASIAN JOURNAL 2024, 19. [CrossRef]

- Bhayo, A.M.; Yang, Y.; He, X. Polymer brushes: Synthesis, characterization, properties and applications. PROGRESS IN MATERIALS SCIENCE 2022, 130. [CrossRef]

- Poisson, J.; Hudson, Z.M. Luminescent Surface-Tethered Polymer Brush Materials. CHEMISTRY-A EUROPEAN JOURNAL 2022, 28. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.S.; Saha, S. Advances in design and applications of polymer brush modified anisotropic particles. ADVANCES IN COLLOID AND INTERFACE SCIENCE 2022, 300. [CrossRef]

- van Eck, G.C.R.; Chiappisi, L.; de Beer, S. Fundamentals and Applications of Polymer Brushes in Air. ACS APPLIED POLYMER MATERIALS 2022. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.y.; Luo, H.n.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y. Research progress in self-oscillating polymer brushes. RSC ADVANCES 2022, 12, 1366–1374. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Mitomo, H.; Ijiro, K. Assembly and Active Control of Nanoparticles using Polymer Brushes as a Scaffold. CHEMISTRY LETTERS 2021, 50, 361–370. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Gautrot, J.E. Responsive Polymer Brush Design and Emerging Applications for Nanotheranostics. ADVANCED HEALTHCARE MATERIALS 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Pester, C.W. Mixed Polymer Brushes for “Smart” Surfaces. POLYMERS 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Hu, W. Surface-grafting polymers: from chemistry to organic electronics. MATERIALS CHEMISTRY FRONTIERS 2020, 4, 692–714. [CrossRef]

- Heggestad, J.T.; Fontes, C.M.; Joh, D.Y.; Hucknall, A.M.; Chilkoti, A. In Pursuit of Zero 2.0: Recent Developments in Nonfouling Polymer Brushes for Immunoassays. ADVANCED MATERIALS 2020, 32. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Ren, B.; Huang, L.; Shen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, M.; Yang, J.; Zheng, J. Salt-responsive zwitterionic polymer brushes with anti-polyelectrolyte property. CURRENT OPINION IN CHEMICAL ENGINEERING 2018, 19, 86–93. [CrossRef]

- Keating, J.J.; Imbrogno, J.; Belfort, G. Polymer Brushes for Membrane Separations: A Review. ACS APPLIED MATERIALS & INTERFACES 2016, 8, 28383–28399. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Ista, L.K.; Gu, R.; Zauscher, S.; Lopez, G.P. Nanopatterned polymer brushes: conformation, fabrication and applications. NANOSCALE 2016, 8, 680–700. [CrossRef]

- Azzaroni, O. Polymer brushes here, there, and everywhere: Recent advances in their practical applications and emerging opportunities in multiple research fields. JOURNAL OF POLYMER SCIENCE PART A-POLYMER CHEMISTRY 2012, 50, 3225–3258. [CrossRef]

- Mocny, P.; Klok, H.A. Tribology of surface-grafted polymer brushes. MOLECULAR SYSTEMS DESIGN & ENGINEERING 2016, 1, 141–154. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.U.; Matsen, M.W. Repulsion Exerted on a Spherical Particle by a Polymer Brush. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 246–252. [CrossRef]

- Egorov, S.A. Insertion of nanoparticles into polymer brush under variable solvent conditions. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2012, 137, 134905, [https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jcp/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/1.4757017/15454558/134905_1_online.pdf]. [CrossRef]

- Lian, Z.; Qi, S.; Zhou, J.; Schmid, F. Solvent Determines Nature of Effective Interactions between Nanoparticles in Polymer Brushes. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2015, 119, 4099–4108. PMID: 25706324. [CrossRef]

- Santo, K.P.; Vishnyakov, A.; Brun, Y.; Neimark, A.V. Adhesion and Separation of Nanoparticles on Polymer-Grafted Porous Substrates. Langmuir 2018, 34, 1481–1496. PMID: 28914540. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Cao, D.; Wu, J. Density functional theory for predicting polymeric forces against surface fouling. Soft Matter 2010, 6, 4631–4646. [CrossRef]

- Milchev, A.; Dimitrov, D.; Binder, K. Excess free energy of nanoparticles in a polymer brush. Polymer 2008, 49, 3611–3618. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Ermilov, V.; Lazutin, A.; Halperin, A. Colloids in Brushes: The Insertion Free Energy via Monte Carlo Simulation with Umbrella Sampling. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 3511–3520. [CrossRef]

- Milchev, A.; Dimitrov, D.I.; Binder, K. Polymer brushes with nanoinclusions under shear: A molecular dynamics investigation. Biomicrofluidics 2010, 4, 032202, [https://pubs.aip.org/aip/bmf/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/1.3396446/14587334/032202_1_online.pdf]. [CrossRef]

- Merlitz, H.; Wu, C.X.; Sommer, J.U. Inclusion Free Energy of Nanoparticles in Polymer Brushes. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 8494–8501. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xiang, X. Adsorption of a spherical nanoparticle in polymer brushes: Brownian dynamics investigation. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2013, 392, 3857–3862. doi:. [CrossRef]

- de Beer, S.; Mensink, L.I.S.; Kieviet, B.D. Geometry-Dependent Insertion Forces on Particles in Swollen Polymer Brushes. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 1070–1078. [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.M.; Li, B.; Zhang, R.; Sun, Z.Y.; Lu, Z.Y. Free energy for inclusion of nanoparticles in solvated polymer brushes from molecular dynamics simulations. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2020, 152, 094905, [https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jcp/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/5.0002257/15575067/094905_1_online.pdf]. [CrossRef]

- Spencer, R.K.W.; Ha, B.Y. How a Polymer Brush Interacts with Inclusions and Alters Their Interaction. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 1304–1313. [CrossRef]

- Laktionov, M.Y.; Shavykin, O.V.; Leermakers, F.A.M.; Zhulina, E.B.; Borisov, O.V. Colloidal particles interacting with a polymer brush: a self-consistent field theory. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 8463–8476. [CrossRef]

- Offner, A.; Ramon, G.Z. The interaction of a particle and a polymer brush coating a permeable surface. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2021, 913, R3. [CrossRef]

- Laktionov, M.Y.; Zhulina, E.B.; Klushin, L.; Richter, R.P.; Borisov, O.V. Selective Colloid Transport across Planar Polymer Brushes. Macromolecular Rapid Communications 2023, 44, 2200980, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/marc.202200980]. [CrossRef]

- Tom, A.M.; Kim, W.K.; Hyeon, C. Polymer brush-induced depletion interactions and clustering of membrane proteins. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2021, 154, 214901, [https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jcp/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/5.0048554/15618870/214901_1_online.pdf]. [CrossRef]

- Nourbakhsh, S.; Yu, L.; Ha, B.Y. Modeling the Protective Role of Bacterial Lipopolysaccharides against Membrane-Rupturing Peptides. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2021, 125, 8839–8854. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astier, S.; Johnson, E.C.; Norvilaite, O.; Varlas, S.; Brotherton, E.E.; Sanderson, G.; Leggett, G.J.; Armes, S.P. Controlling Adsorption of Diblock Copolymer Nanoparticles onto an Aldehyde-Functionalized Hydrophilic Polymer Brush via pH Modulation. Langmuir 2024, 40, 3667–3676. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popova, T.O.; Borisov, O.V.; Zhulina, E.B. Polyelectrolyte Brushes with Protein-Like Nanocolloids. Langmuir 2024, 40, 1232–1246. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorka, W.; Kuciel, T.; Nalepa, P.; Lachowicz, D.; Zapotoczny, S.; Szuwarzynski, M. Homogeneous Embedding of Magnetic Nanoparticles into Polymer Brushes during Simultaneous Surface-Initiated Polymerization. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 456. [CrossRef]

- San Choi, W.; Young Koo, H.; Young Kim, J.; .; Huck, W.T.S. Collective Behavior of Magnetic Nanoparticles in Polyelectrolyte Brushes. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 4504–4508. [CrossRef]

- Evans, B.A.; Shields, A.R.; Carroll, R.L.; Washburn, S.; Falvo, M.R.; Superfine, R. Magnetically Actuated Nanorod Arrays as Biomimetic Cilia. Nano Lett 2007, 7, 1428–1434. [CrossRef]

- Benkoski, J.J.; Deacon, R.M.; Land, H.B.; Baird, L.M.; Breidenich, J.L.; Srinivasan, R.; Clatterbaugh, G.V.; Keng, P.Y.; Pyun, J. Dipolar assembly of ferromagnetic nanoparticles into magnetically driven artificial cilia. Soft Matter 2010, 6, 602–609. [CrossRef]

- Haddour, N.; Chevolot, Y.; Trévisan, M.; Souteyrand, E.; Cloarec, J.P. Use of magnetic field for addressing, grafting onto support and actuating permanent magnetic filaments applied to enhanced biodetection. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 8266–8271. [CrossRef]

- Vilfan, M.; Potočnik, A.; Kavčič, B.; Osterman, N.; Poberaj, I.; Vilfan, A.; Babič, D. Self-assembled artificial cilia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 1844–1847, [https://www.pnas.org/content/107/5/1844.full.pdf]. [CrossRef]

- Trévisan, M.; Duval, A.; Moreau, J.; Bartelian, B.; Canva, M.; Monnier, V.; Chevolot, Y.; Cloarec, J.; Souteyrand, E. Assembling, locating, grafting and actuating permanent filaments for validation of Polarimetric Surface Plasmon Resonance Imaging system. Procedia Engineering 2011, 25, 872 – 875. EurosensorsXXV. [CrossRef]

- Trévisan, M.; Chevolot, Y.; Monnier, V.; Cloarec, J.P.; Souteyrand, E.; Duval, A.; Moreau, J.; Canva, M. Elaboration and grafting of magnetic bead-chains for detection of anisotropy with polarimetric surface plasmon resonance imaging system. International Journal of Nanoscience 2012, 11, 1240012. [CrossRef]

- Breidenich, J.L.; Wei, M.C.; Clatterbaugh, G.V.; Benkoski, J.J.; Keng, P.Y.; Pyun, J. Controlling length and areal density of artificial cilia through the dipolar assembly of ferromagnetic nanoparticles. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 5334–5341. [CrossRef]

- Tokarev, A.; Gu, Y.; Zakharchenko, A.; Trotsenko, O.; Luzinov, I.; Kornev, K.G.; Minko, S. Reconfigurable Anisotropic Coatings via Magnetic Field-Directed Assembly and Translocation of Locking Magnetic Chains. Advanced Functional Materials 2014, 24, 4738–4745, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/adfm.201303358]. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zheng, Y. Bio-inspired artificial cilia with magnetic dynamic properties. Frontiers of Materials Science 2015, 9, 178. [CrossRef]

- Hanasoge, S.; Hesketh, P.J.; Alexeev, A. Microfluidic pumping using artificial magnetic cilia. Microsystems & Nanoengineering 2018, 4, 11. [CrossRef]

- Vu, A.; Freeman, E.; Qian, X.; Ulbricht, M.; Ranil Wickramasinghe, S. Tailoring and remotely switching performance of ultrafiltration membranes by magneticaly responsive polymer chains. Membranes 2020, 219, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Akkilic, N.; Leermakers, F.A.M.; de Vos, W.M. Responsive polymer brushes for controlled nanoparticle exposure. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 17871–17878. [CrossRef]

- Fahrni, F.; Prins, M.W.J.; van IJzendoorn, L.J. Micro-fluidic actuation using magnetic artificial cilia. Lab Chip 2009, 9, 3413–3421. [CrossRef]

- Babataheri, A.; Roper, M.; Fermigier, M.; Roure, O.D. Tethered fleximags as artificial cilia. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2011, 678, 5–13. [CrossRef]

- Ben, S.; Zhou, T.; Ma, H.; Yao, J.; Ning, Y.; Tian, D.; Liu, K.; Jiang, L. Multifunctional Magnetocontrollable Superwettable-Microcilia Surface for Directional Droplet Manipulation. Advanced Science 2019, 6, 1900834, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/advs.201900834]. [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Song, F.J.; Dobnikar, J. Assembly of Superparamagnetic Filaments in External Field. Langmuir : the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids 2016, 32 36, 9321–8.

- Sánchez, P.A.; Pyanzina, E.S.; Novak, E.V.; Cerdà, J.J.; Sintes, T.; Kantorovich, S.S. Magnetic filament brushes: tuning the properties of a magnetoresponsive supracolloidal coating. Faraday Discuss. 2016, 186, 241–263. [CrossRef]

- Pyanzina, E.S.; Sánchez, P.A.; Cerdà, J.J.; Sintes, T.; Kantorovich, S.S. Scattering properties and internal structure of magnetic filament brushes. Soft Matter 2017, 13, 2590–2602. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, P.A.; Pyanzina, E.S.; Novak, E.V.; Cerdà, J.J.; Sintes, T.; Kantorovich, S.S. Supramolecular Magnetic Brushes: The Impact of Dipolar Interactions on the Equilibrium Structure. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 7658–7669. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozhkov, D.A.; Pyanzina, E.S.; Novak, E.V.; Cerdà, J.J.; Sintes, T.; Ronti, M.; Sánchez, P.A.; Kantorovich, S.S. Self-assembly of polymer-like structures of magnetic colloids: Langevin dynamics study of basic topologies. Molecular Simulation 2018, 44, 507–515. [CrossRef]

- Cerdà, J.J.; Bona-Casas, C.; Cerrato, A.; Novak, E.V.; Pyanzina, E.S.; Sánchez, P.A.; Kantorovich, S.; Sintes, T. Magnetic responsive brushes under flow in strongly confined slits: external field control of brush structure and flowing particle mixture separation. Soft Matter 2019, 15, 8982–8991. [CrossRef]

- Cerdà, J.J.; Bona-Casas, C.; Cerrato, A.; Sintes, T.; Massó, J. Colloidal magnetic brushes: influence of the magnetic content and presence of short-range attractive forces in the micro-structure and field response. Soft Matter 2021, 17, 5780–5791. [CrossRef]

- Zaben, A.; Kitenbergs, G.; Cebers, A. Deformation of flexible ferromagnetic filaments under a rotating magnetic field. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2020, 499, 166233. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Belovs, M.; Cēbers, A. Ferromagnetic microswimmer. Phys Rev E 2009, 79, 051503. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, N.; Zhang, N.; Du, H. A dynamic absorber with a soft magnetorheological elastomer for powertrain vibration suppression. Smart Materials and Structures 2009, 18, 074009. [CrossRef]

- Goubault, C.; Jop, P.; Fermigier, M.; Baudry, J.; Bertrand, E.; Bibette, J. Flexible Magnetic Filaments as Micromechanical Sensors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 260802. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Mao, Y.; Ge, J. The magnetic assembly of polymer colloids in a ferrofluid and its display applications. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 1598–1605. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.W.; Hu, S.T.; Yang, S.Y.; Horng, H.E.; Hung, J.C.; Hong, C.Y.; Yang, H.C.; Chao, C.H.; Lin, C.F. Tunable diffraction of magnetic fluid films and its potential application in coarse wavelength-division multiplexing. Opt. Lett. 2004, 29, 1867–1869. [CrossRef]

- Pirmoradi, F.N.; Jackson, J.K.; Burt, H.M.; Chiao, M. A magnetically controlled MEMS device for drug delivery: design, fabrication, and testing. Lab Chip 2011, 11, 3072–3080. [CrossRef]

- Corr, S.A.; Byrne, S.J.; Tekoriute, R.; Meledandri, C.J.; Brougham, D.F.; Lynch, M.; Kerskens, C.; O’Dwyer, L.; Gun’ko, Y.K. Linear Assemblies of Magnetic Nanoparticles as MRI Contrast Agents. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2008, 130, 4214–4215. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Q. Magnetic Nanochains: a review. Nano 2011, 06, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Warner, H. R., J. Kinetic Theory and Rheology of Dilute Suspensions of Finitely Extendible Dumbbells. Industrial and Engineering Chemistry Fundamentals 1972, 11, 379–387. Cited By :385. [CrossRef]

- Weeks, J.D.; Chandler, D.; Andersen, H.C. Role of Repulsive Forces in Determining the Equilibrium Structure of Simple Liquids. J Chem Phys 1971, 54, 5237–5247. [CrossRef]

- Cerdà, J.J.; Ballenegger, V.; Lenz, O.; Holm, C. P3M algorithm for dipolar interactions. J Chem Phys 2008, 129, 234104. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, A.; de Joannis, J.; Holm, C.J. Electrostatics in periodic slab geometries. I. J. Chem. 2002, 117, 2496. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Holm, C. Estimate of the cutoff errors in the Ewald summation for dipolar systems. J. Chem. 2001, 115, 6351. [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.P.; Tildesley, D.J. Computer Simulation of Liquids, 1 ed.; Oxford Science Publications, Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1987.

- Limbach, H.J.; Arnold, A.; Mann, B.A.; Holm, C. ESPResSo – An Extensible Simulation Package for Research on Soft Matter Systems. Comput Phys Commun 2006, 174, 704–727. [CrossRef]

- Suwa, M.; Tsukahara, S.; Watarai, H. Applications of magnetic and electromagnetic forces in micro-analytical systems. Lab Chip 2023, 23, 1097–1127. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skjeltorp, A.T. One- and Two-Dimensional Crystallization of Magnetic Holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1983, 51, 2306–2309. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J.; Klingenberg, D.J.; Hidalgo-Alvarez, R.; de Vicente, J. Steady shear magnetorheology of inverse ferrofluids. Journal of Rheology 2011, 55, 127–152. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).