1. Introduction

The development of smart surface coatings is one of the promising areas of modern nanotechnology. One of the most popular methods in this field is the use of polymer brushes as smart polymer coatings (SPCs), which can be used in many applications [

1]. Examples are switch sensors [

2,

3,

4,

5], antifouling surfaces [

6,

7,

8,

9], lubrication [

10], targeting drug delivery [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15], chromatographic protein separations [

16,

17,

18].

To control the surface properties of brushes by changing external conditions, mixed brushes are used, consisting of polymer chains of different structures. An example is brushes consisting of chains with different affinities for the solvent. By changing the affinity for the solvent due to the solvent composition, the ionic strength or temperature in such brushes a segregation of the grafted chains may occur. Extreme cases of segregation include lateral and vertical ones. If the brush components are highly incompatible, lateral segregation arises. Alternatively, if the compatibility between the brush components is high enough, vertical segregation occurs [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. The greatest interest for smart coating creation are mixed brushes with vertical microsegregation which implies macromolecules of one type to locate inside the brush near the grafting surface, and macromolecules of another type to form the periphery of the brush.

A characteristic feature of such brushes is a sharp change in the morphology of the brush in a narrow range of environmental parameters. In this case, a switching occurs: the chains from the surface go inside the brush, and the ends of the initially internal chains form a new surface of the brush with new properties. If one of the components is a polyelectrolyte, then another control parameter arises with which you can change the morphology of the brush: the ionic strength of the solution in which the mixed brush is immersed. If the brush consists of polyelectrolyte and neutral chains, then the change in ionic strength will affect mainly the polyelectrolyte chains. It is well known that the size of polyelectrolyte chains in a brush decreases with increase of the ionic strength of the solution. If the structure of mixed brush is such that at low ionic strengths the ends of the charged chains are higher than the ends of the neutral chains, then, as the ionic strength increases, the polyelectrolyte chains may appear lower than the ends of the neutral chains. Accordingly, the properties of the brush surface will change and we observe the conformation transition similar to that for mixed brushes with different affinities.

There is a lot of experimental and theoretical works where brushes containing only polyelectrolyte chains were considered [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. There is also several experimental studies of mixed brushes containing both polyelectrolyte and neutral chains [

30,

31,

32]. As to the theory of such brushes there is only work [

33], where polyelectrolyte and neutral chains can change positions on the grafting surface. In such brushes the variation of charge or ionic strength will lead to the lateral phase separation This work is the first to consider a mixed brush in which vertical micro-segregation of charged and neutral chains is possible. In such a brush, the points of attachment of the chains to the surface are fixed and when external conditions change, the positions of the free ends may change as well.

The main goal of our study is the determine the conditions when a transition occurs in which the charged chains on the surface of the brush are replaced by the ends of neutral chains.

Polyelectrolyte brushes can be found in three regimes with respect to medium ionic strength: "osmotic", "salted" and “quasi-neutral” regimes [

25]. Under conditions of low ionic strength, the localisation of counterions inside the brush leads to the generation of osmotic pressure (osmotic regime), which favours brush swelling. When the ionic strength increases to a value comparable to the ion concentration inside the brush, a “salted brush” regime is observed. The addition of ions to the medium leads to a decrease in the osmotic pressure of counterions and the brush begins to collapse due to entropic elasticity (in our case also due to hydrophobic interactions). At very high ionic strength, the polyelectrolyte brush goes into a quasi-neutral state, in which the influence of the ion-osmotic effect is negligible compared to the influence of non-electrostatic interactions. If the solvent is poor under such conditions, the brush will collapse to the limit.

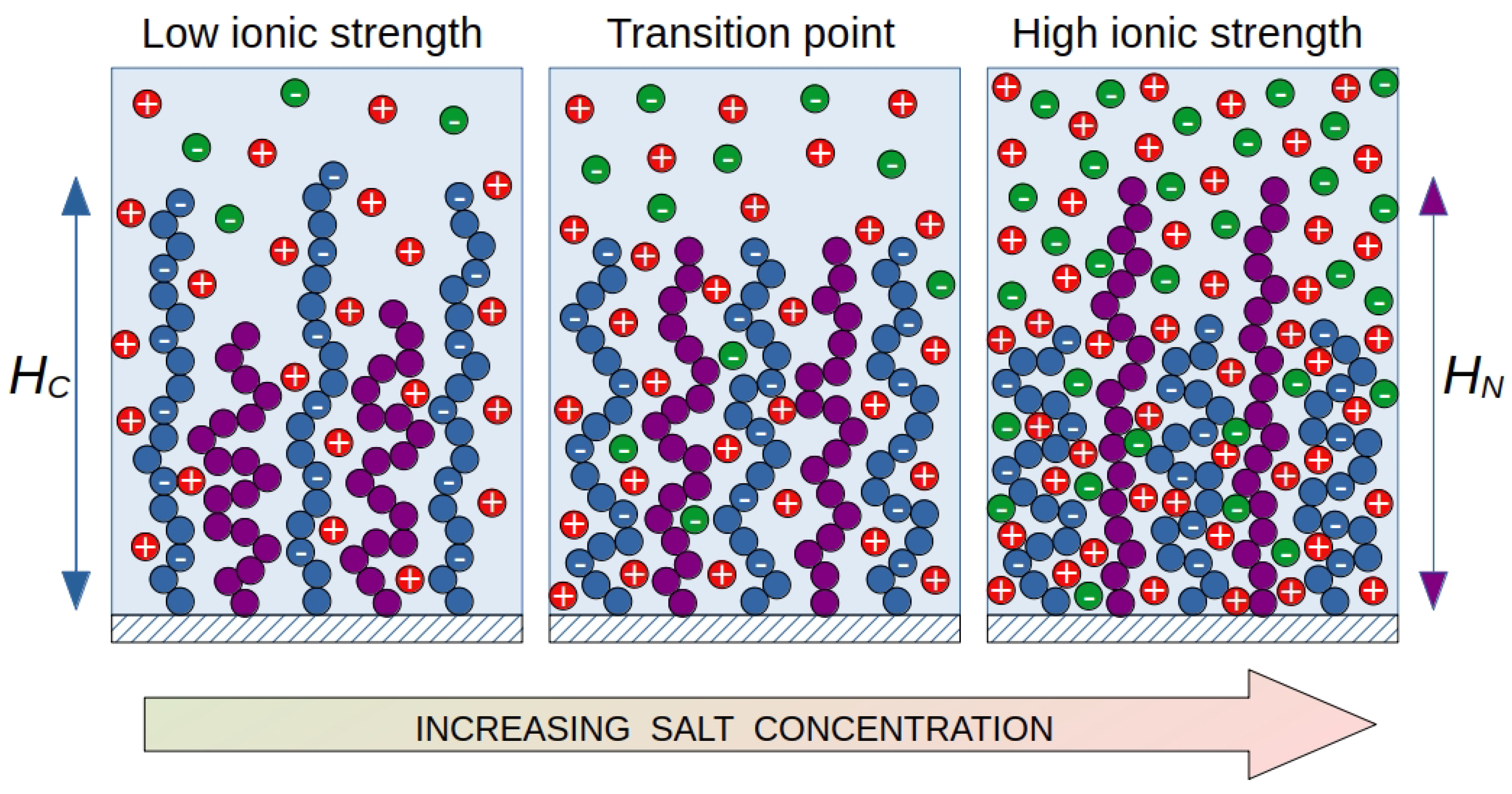

In a mixed brush (

Figure 1), polyelectrolyte chains are "diluted" with neutral chains, but the same trends for polyelectrolyte chains remain. If both neutral and charged chains have the same contour length and the charged ones have a worse affinity for the solvent, the position of the end units in the brush "switches". At low ionic strength, the ends of the polyelectrolyte chains are located at the periphery of the brush, shielding the surface from neutral chains. At a high salt concentration, the opposite effect is observed: the polyelectrolyte chains are collapsed, giving way to neutral chains at the brush periphery. At some intermediate salt concentration there is a transition point. At this point, the end positions (chain heights

and

) for the charged and neutral chains are at the same level. The segregation of such brushes can be controlled by varying two intensive parameters of the system: the ionic strength of the solution and the selectivity of the solvent (temperature). The purpose of this work is to predict the conditions under which vertical segregation of mixed polyelectrolyte-neutral brushes occurs depending on the composition of the brush and the molecular parameters of the grafted chains.

2. Model and Method

2.1. Model

To study salt-controled vertical segregation in mixed polymer brushes, we consider the following coarse-grained model (

Figure 1). A flat brush is formed by two types of chains: neutral (uncharged) chains and charged (polyelectrolyte) chains. Their degrees of polymerization are

and

, grafting densities are

and

, respectively. All chains are considered flexible, i.e. the size of the monomer unit

a coincides with the statistical length of the segment. The chains are grafted at one end onto a flat impenetrable uncharged surface.

The brush is immersed into a sufficiently large reservoir of aqueous solution of salts with concentration

, which contains monovalent cations (

) and anions (

) carrying an elementary charge

. Thus, the molar ionic strength

I of the salt solution is equal to the salt concentration:

The polyelectrolyte counter ions are indistinguishable from free cations in solution. It is assumed that the monomer units, ions and neutral water molecules have the same linear size

a. We will also assume that this value is equal to the linear size of a water molecule:

. Our simulations were performed at a fixed temperature

and at a fixed relative dielectric constant of the medium

that corresponds to the Bjerrum length:

where

is the vacuum permittivity,

is the Boltzmann constant.

The Debye screening length in the bulk of the solution is determined by its ionic strength:

where

is the Avogadro constant. As the ionic strength decreases from

to

, the Debye length increases from

to

. The bound charges on the polyelectrolyte chains cease to have an electrostatic effect on free ions at a distance

from the polymer brush surface and the local ion concentration reaches the setup level concentration

. The boundary condition of the model is a fixed value of the concentration of co-ions of charged chains (

) at a large distance (

) from the brush surface. The concentration of counterions is selected automatically during the modeling process according to the condition of electrical neutrality.

Charged chains in a mixed brush are considered to be strong polyelectrolytes. The fraction of ionized monomer units in a strong polyelectrolyte is independent of the pH and ionic strength of the solution. In other words, each charged chain in the brush has a fractional charge per monomer unit. The sign of the charge of the polymer chain does not affect the simulation results and it was chosen negative for definiteness.

Neutral and charged chains also have different affinities for the solvent. It is assumed that the solvent is athermal with respect to neutral chains, but polyelectrolyte chains are capable of changing their solvatophobicity. The solvent is selective with respect to different types of grafted chains. The strength of selectivity is specified in the model through the Flory-Huggins parameter, , which characterizes the incompatibility of water molecules and monomer units of charged chains.

The segregation transition point is taken to be a combination of parameters (a, b), at which the first moments of the distribution of end segments in the direction normal to the grafting surface for both types of chains are equal (

, see

Figure 1).

2.2. Method

An one-gradient Scheutjens-Fleer self-consistent field (SCF) numerical method was used to study vertical segregation in mixed polyelectrolyte brushes. This method for studying polyelectrolyte systems was first proposed in the article [

34] and then improved in the work [

35].

The self-consistent field method uses the basic assumption of the mean-field approximation that the consideration of a system of many molecules can be replaced by the consideration of the conformations of a limited number of molecules of different types, which are under the influence of a common effective field that describes their interaction with each other and with other molecules. The main idea of this assumption is to reduce the solution of the problem using particle coordinates to the problem of finding the distribution of the volume fraction of particles in the field of a self-consistent potential . Moreover, in the one-gradient method, these distributions are considered as functions of only one coordinate z, which is normal to the grafting surface of the macromolecules.

To find the equilibrium distributions of

for different types of molecules

(where

A is a set of different types of particles: charged and neutral monomer units, water molecules, salt ions), the free energy of the molecular system is minimized numerically. This problem is solved by the method of Lagrange multipliers (Lagrange field

), taking into account the incompressibility condition:

The functional to be minimized is

where

is the partition function of molecular component

i,

is the free energy of interaction between these components, consisting of the excluded bulk interaction and the Coulomb interaction:

Here

is Flory-Huggins parameter describes hydrophobic interactions (in our case between polyelectrolyte chains and the water molecules),

is volume fraction of components in bulk solution,

e is the elementary charge,

is the dimensionless charge of a particle of type

i,

, where

is electrostatic potential given by the Poisson-Boltzmann equation:

where

is the relative dielectric constant of water,

is the vacuum permittivity,

is the distribution of the total charge in each layer at a distance

z from the grafting surface.

Based on the condition of minimization of the functional

, the potential

can be represented in the form of three terms:

the Lagrange field

, the field of hydrophobic forces leading to the collapse of polyelectrolyte chains

and the electrostatic field promoting swelling of charged chains:

From another condition for minimizing the functional

follows a method for calculating the distribution of the volume fraction of components:

The numerical solution of this equation is carried out using a special iterative procedure that uses special propagator matrices to calculate the statistical sums of polymer chains on a cubic lattice.

Within the framework of the SF-SCF method, a random initial field

is first specified, then the partition function of chains in this field is calculated, the distribution of the density

is calculated from the partition function, and the initially specified field

is corrected according to these distribution

. The calculation loop continues until

and

are consistent with each other for the specified structural parameters of the molecular system and the incompressibility condition. In this case, the distribution of the total charge

and the distribution of the electrostatic potential

also become consistent. The algorithm of the procedure used in this work is described in detail in the work [

35] cited above.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analytical Theory

For the analytical prediction of the critical value of incompatibility of polyelectrolyte chains with a solvent

, we have developed the theory based on the simple box-model [

26]. In this model the ends of grafted chains are not distributed over the brush but are fixed at the same distance

H from the grafting surface, and all chains are evenly stretched. For simplicity, the volume fraction of monomer units is considered as an average value independent of the distance from the grafting surface:

where

is the total grafting density of charged and neutral chains.

In order to find out what value of corresponds to the transition point, we will assume that the ends of both types of chains are located at the same distance from the grafting surface, where is the height of the neutral brush with the same total grafting density as in the mixed one.

In an equilibrium state, a balance of pressures (forces per unit grafting surface area) acting on the brush must be maintained [

28]:

Here is the osmotic pressure of mobile ions, is the negative elastic pressure due to chain stretching, is the osmotic pressure caused by the entropy of polymer-solvent mixing, is the pressure causing hydrophobic compression of polyelectrolyte chains (contribution of the Flory-Huggins interaction energy).

The first electrostatic contribution can be expressed by charge balance (so called the Donnan equilibrium [

26]):

where

and

X are the degree of ionization of polyelectrolyte chains and their share in the composition of the mixed brush. Thus, the expression before the parentheses represents the concentration of charged monomer units in the brush. Parameter

y denotes twice the ratio of salt concentration and charged monomer unit concentration:

The factor 55.5 is used to convert ionic strength (concentration of salt ions) from mol/L units to dimensionless volume fraction. Since one liter of water contains

mol, the dimensionless volume fraction of salt ions is calculated as the ratio

, where

is the concentration of monovalent salt (

).

The second term in Equation (

13) is the force that must be applied to stretch the freely jointed chain to the distance

H between the grafted and free ends. In the regime of Gaussian stretching of chains, this contribution can be represented as

The contribution of the entropy of polymer-solvent mixing, according to the Flory theory, is calculated by the formula:

Hydrophobic forces promoting the decomposition of polyelectrolyte chains with increasing Flory-Huggins parameter are described by the following expression

Taking into account all the equations described above, we obtain the desired equation that describes the dependence of the critical value

on the structural parameters of the mixed brush and the ionic strength:

At the transition point, hydrophobic interactions neutralize electrostatic ones, resulting in the polyelectrolyte and neutral chains take on identical conformations, corresponding to the conformations in a neutral brush in an athermal solvent. In this case:

and both types of chains are extended to the height

of the brush with a total grafting density

in an athermal solvent.

Given these model assumptions, Equation (

13) can be written as

where

is mean density of monomer units in a neutral brush under athermal solvent conditions.

Two extreme cases can be considered. At high ionic strengths (and at

or

), the critical selectivity

decreases inversely with increasing ionic strength

I:

At low ionic strengths, the value of

ceases to depend on ionic strength:

These predictions are scaling due to the primitiveness of the model, however, the presented analytical model suggests that the dependence (

22) can be described as a two-parameter one using two empirical coefficients

A and

B:

3.2. SCF Simulation Data

The analytical theory uses a box model, which has limitations. In particular, this model assumes that the ends of the grafted chains are located at the same distance from the grafting surface.

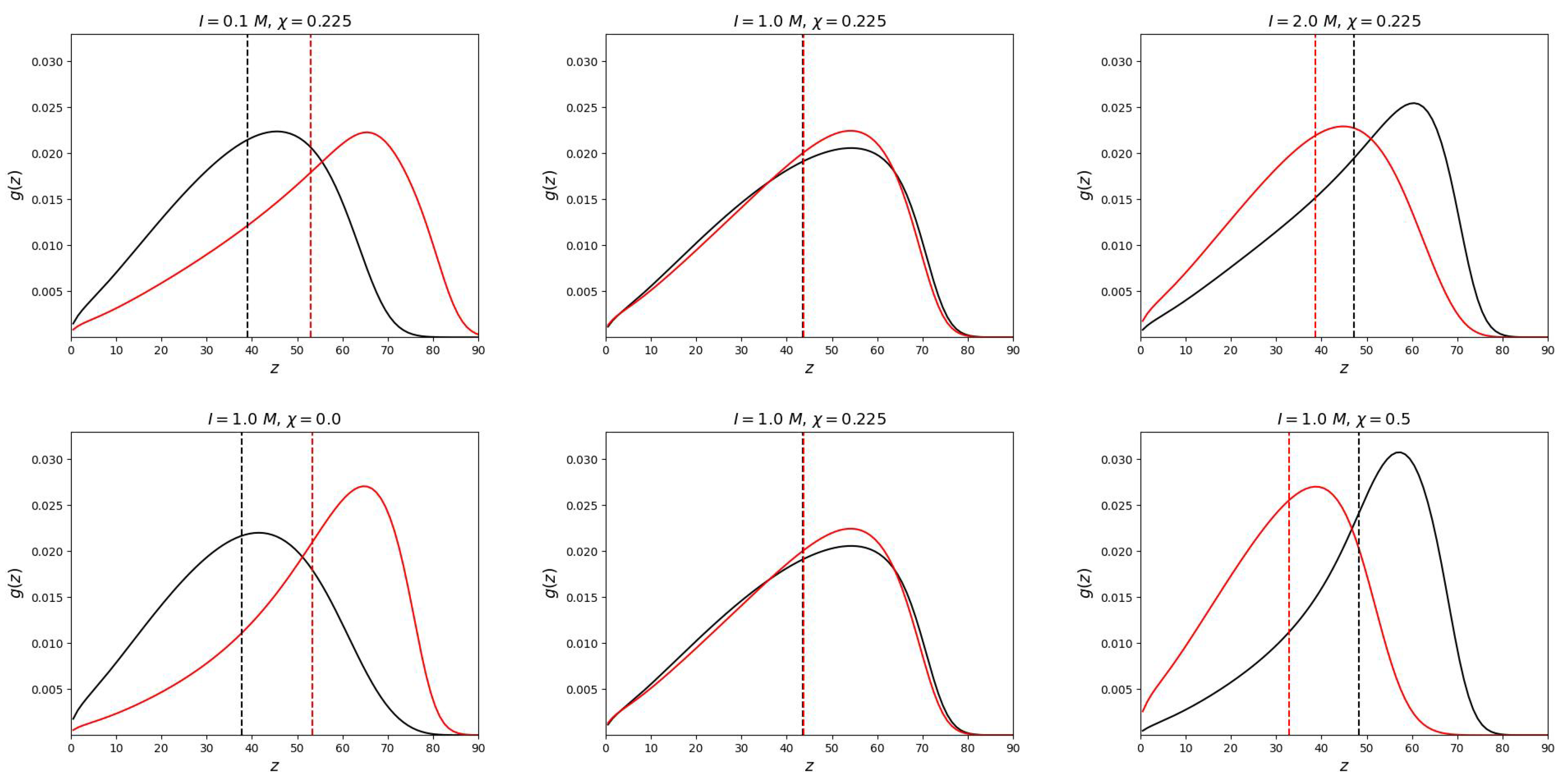

Numerical SCF model does not have this limitation. As can be seen from

Figure 2, the end groups are located throughout the volume of the mixed polymer brush.

The

Figure 2 shows how the "switching" of the position of the grafted chains occurs. In the middle column of the upper and lower graphs, the parameters are selected so that the free ends (for both neutral and polyelectrolyte chains) are located equally relative to the grafting surface. This positions were determined in the work as the first moment of the distribution of the ends:

As can be seen from the graphs, the end groups of the polyelectrolyte chain can take a place on the periphery of the brush or “go” closer to the grafting surface depending on the selectivity of the solvent or ionic strength I. Thus, the segregation of chains in the brush can be controlled by changing the selectivity of the solvent (temperature) and the salt concentration (ionic strength of the solution). At each value of ionic strength, it is possible to determine the critical selectivity of the solvent at which vertical segregation occurs.

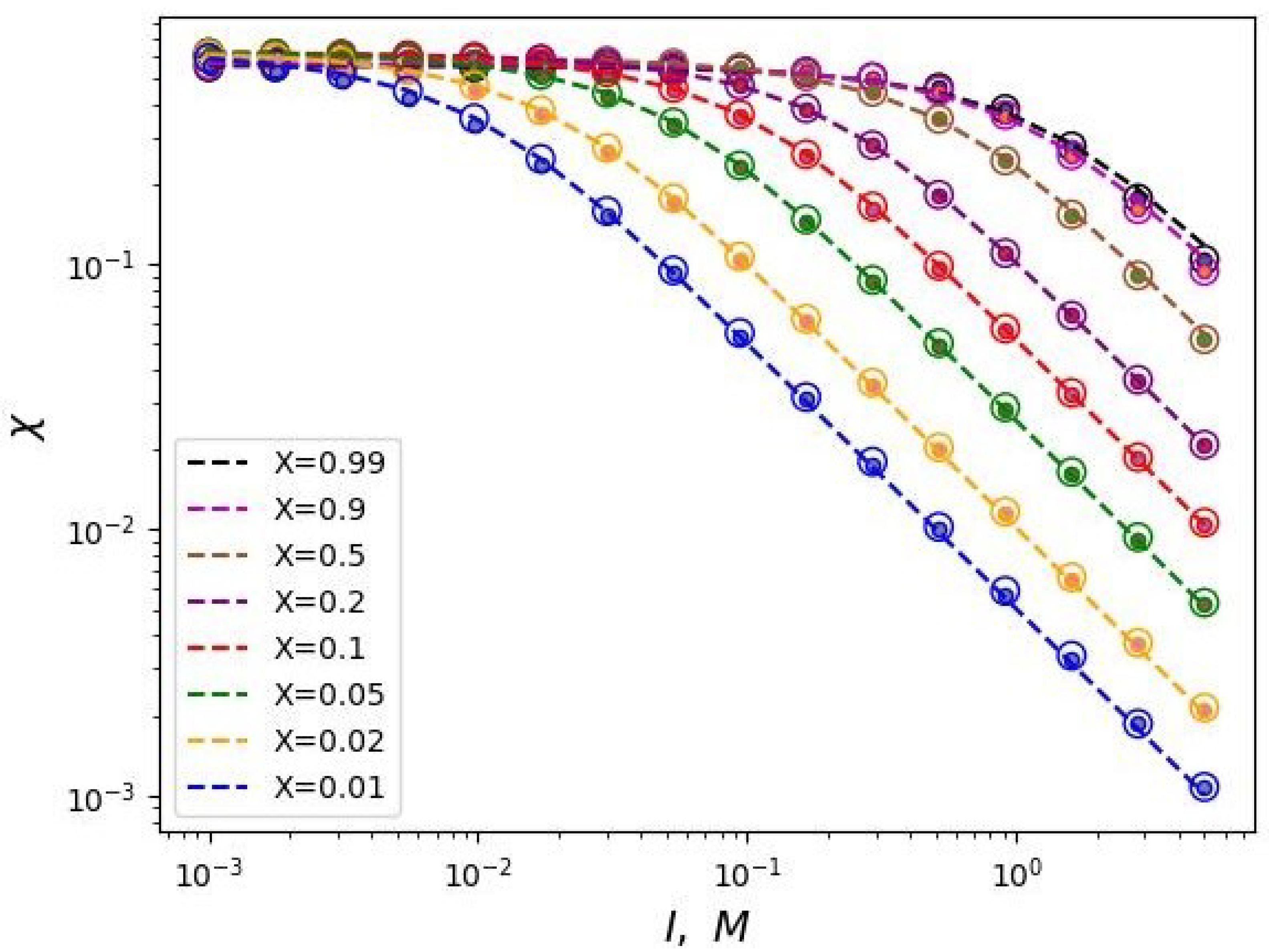

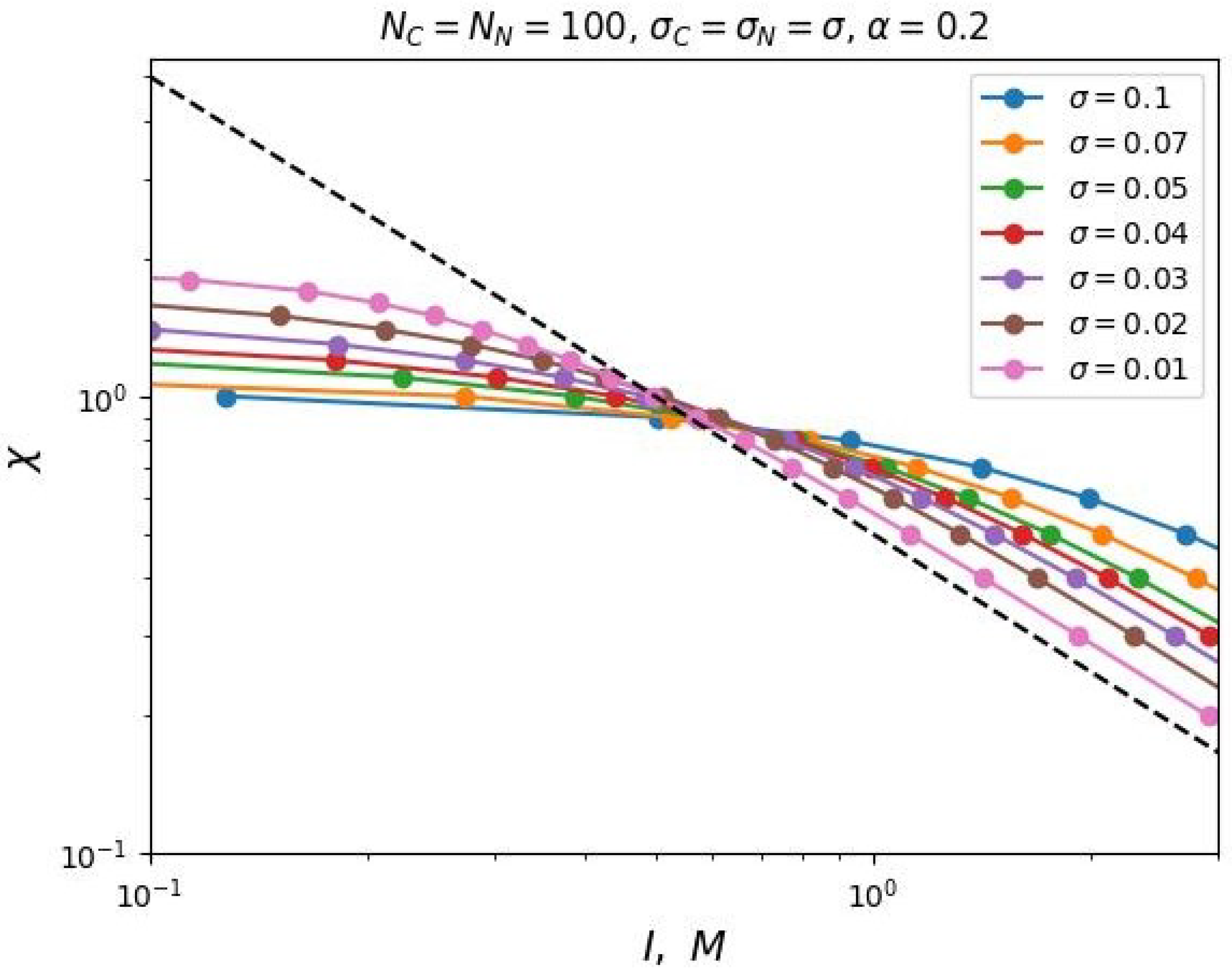

Figure 3 shows the dependencies of critical

on

I for different values of the polyelectrolyte chains share in the mixed brush and different values of the degree of polymerization of the grafted chains in double logarithmic coordinates. This graph can be considered as a diagram. Each curve divides the parameter region

into two parts: above the curve and below the curve. The parameter region below the curves corresponds to the state when the free ends of the neutral chains are located below the charged ones. And vice versa, above the corresponding curves the ends of the polyelectrolyte chains are located below the neutral ones.

It can be noted that these dependencies reach a "plateau" in the region of low salt concentrations (in the "osmotic" regime of the brush). In other words, the value of the segregation point at low ionic strength of the solvent tends to some constant value that does not depend on the share of polyelectrolyte chains in the brush. Thus, in the region of low salt concentrations, vertical segregation can occur only due to a change in the solvent selectivity over a wide range of ionic strength. As the salt concentration increases, the critical selectivity decreases inversely proportional to the value of the ionic strength of the solution. In this region of salt concentration, higher share of polyelectrolyte chains X corresponds to a higher critical selectivity .

This conclusion is also consistent with the analytical theory (Equations (

23) and (

24)). Also, the obtained dependencies have the predicted form of the function (Equation (

25)). The

Figure 3 shows the data fitting by the two-parameter model (Equation (

25)) with dotted lines.

An increase in the degree of ionization of monomer units of the polyelectrolyte chains, according to our analytical theory, should lead to an increase in the critical selectivity of the solvent necessary for the segregation transition at any ionic strength of the solution. The obtained numerical simulation data fully confirm this prediction (

Figure 4).

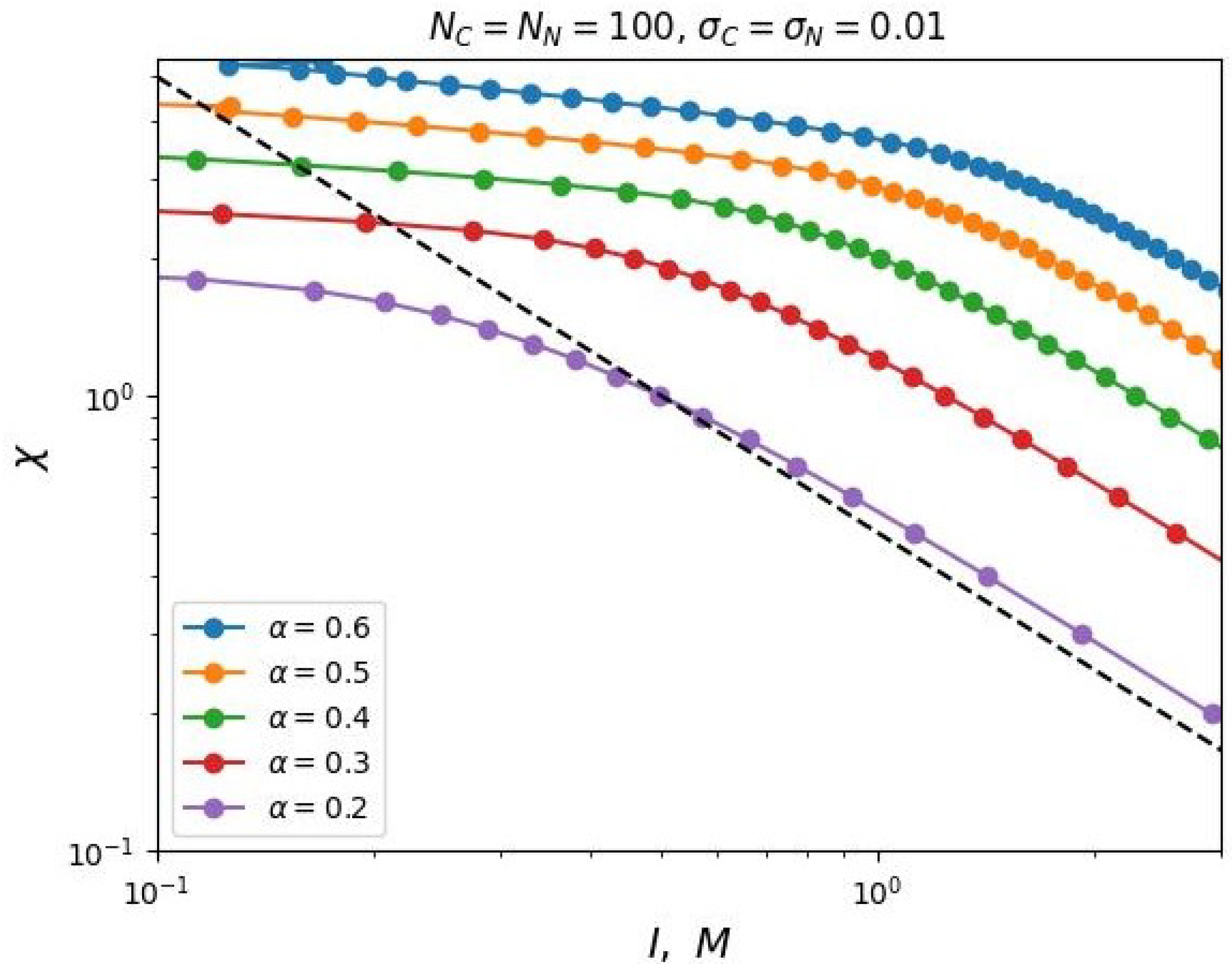

In case of increasing the grafting density

, our analytical theory predicts a decrease in the value of the segregation transition point

at low salt concentrations, which is also confirmed by the results of numerical SCF simulation (see

Figure 5).

However, in the region of high salt concentrations, some discrepancy between the analytical prediction and the modeling is observed. The value of

increases with increasing grafting density

, although, according to Formula (

23), the value of

should not depend on

at high at high salt concentrations. This contradiction is explained by the non-uniform distribution of the density of monomer units and the charge distribution in the volume of the brush, which is not taken into account by the simplified box-model, but is taken into account in the SF-SCF modeling. But even in this case, a two-parameter model (

25) is applicable to describe the dependence

.

4. Conclusions

By using the self-consisting field approach the salt-controlled vertical segregation of the flat mixed polymer brushes containing polyelectrolyte and neutral chains was studied. It was assumed that the selectivity to the solvent was varied for polyelectrolyte chains while the others polymer chains in a brush remained hydrophilic and neutral. Solvent selectivity (i.e., the hydrophobicity of the polyelectrolyte chains) can be controlled by changing the temperature. At low salt concentrations, the polyelectrolyte chains swell and occupy the surface of the mixed brush. At high salt concentrations, the hydrophobic polyelectrolyte chains collapse and give place to neutral chains on the surface. By changing the selectivity of the solvent and the ionic strength of the solution, the surface properties of such mixed brushes can be controlled. Based on the numerical simulations results, it is shown how the critical selectivity corresponding to the segregation transition in polyelectrolyte/neutral brushes depends on the ionic strength of the solution. It is shown that at the same ionic strength, the critical selectivity increases with increasing chain grafting density and the degree of dissociation of charged groups, as well as with increasing share of polyelectrolyte chains in the mixed brush. Within the framework of the mean field theory, a two-parameter model has been constructed that quantitatively describes these dependencies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.V.M., and A.A.D.; methodology, I.V.M., and A.A.D.; software, I.V.M.; validation, I.V.M. and A.A.D.; formal analysis, I.V.M., and A.A.D.; investigation, I.V.M., and A.A.D.; resources, I.V.M.,and A.A.D.; data curation, I.V.M., and A.A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, I.V.M., and A.A.D.; writing—review and editing, I.V.M., and A.A.D.; visualization, I.V.M.; supervision, A.A.D.; project administration, A.A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCF (method) |

The self-consistent field (method) |

| SF-SCF (method) |

The Scheutjens–Fleer self-consistent field (method) |

| SPC |

Smart polymer coatings |

References

- Giussi, J.M.; Cortez, M.L.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Azzaroni, O. Recent developments in flame retardant polymeric coatings. Chemical Society Reviews 2019, 48, 814–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C. Surface-initiated atom transfer radical polymerization for applications in sensors, non-biofouling surfaces and adsorbents. Polymer Journal 2016, 48, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Ferris, R.; Zhang, J.; Ducker, R.; Zauscher, S. Stimulus-responsive polymer brushes on surfaces: Transduction mechanisms and applications. Progress in Polymer Science 2010, 35, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jamali, S.; Liu, Q.; Maia, J.; Baek, J.B.; Jiang, N.; Xu, M.; Dai, L. Conformational transitions of polymer brushes for reversibly switching graphene transistors. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 7434–7441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Alvarado, A.B.; Iturbe-Ek, J.; Mamidi, N.; Sustaita, A.O. Polymer brush-based thin films via Cu(0)-mediated surface-initiated atom transfer radical polymerization for sensing applications. ACS Applied Polymer Materials 2021, 3, 5339–5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Jung, J. Polymer brush: A promising grafting approach to scaffolds for tissue engineering. BMB Reports 2016, 49, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Feng, C.; Hu, J.; Shi, P.; Gu, G.; Wang, L.; Huang, X. Spin-casting polymer brush films for simuli-responsive and anti-fouling surfaces. ACS Applied Materials Interfaces 2016, 8, 6685–6692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.; Truong, V.K.; Woo, S.Y.; Dickey, M.D.; Hsiao, L.; Genzer, J. Counterpropagating gradients of antibacterial and antifouling polymer brushes. Biomacromolecules 2021, 23, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmyn, A.R.; Teunissen, L.W.; Fritz, P.; van Lagen, B.; Smulders, M.M.J.; Zuilhof, H. Diblock and random antifouling bioactive polymer brushes on gold surfaces by visible-light-induced polymerization (SI-PET-RAFT) in water. Advanced Materials Interfaces 2022, 9, 2101784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spirin, L.; Galuschko, A.; Kreer, T.; Johner, A.; Baschnagel, J.; Binder, K. Polymerbrush lubrication in the limit of strong compression. The European Physical Journal E 2010, 33, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Li, C.; Li, L.; Guo, J.; Zhang, J. Bioresponsive drug delivery systems for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Journal of Controlled Release 2020, 327, 641–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mura, S.; Nicolas, J.; Couvreur, P. Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug delivery. Nature Materials 2013, 12, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfhaid, L.H.K. Recent advance in functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles with stimuli-responsive polymer brush for controlled drug delivery. Soft Materials 2022, 20, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurds, L.; Lauko, J.; Rowan, A.E.; Amiralian, N. Tailored nanocellulose-grafted polymer brush applications. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2021, 9, 17173–17188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Gautrot, J.E. Responsive polymer brush design and emerging applications for nanotheranostics. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2021, 10, 2000953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagase, K.; Kobayashi, J.; Kikuchi, A.; Akiyama, Y.; Kanazawa, H.; Okano, T. Protein separations via thermally responsive ionic block copolymer brush layers. RSC Advances 2016, 6, 26254–26263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, G.; Yu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Xin, Q.; Han, S. Protein fractionation of pH-responsive brush-modified ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer membranes. Polymer Engineering and Science 2022, 62, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Castillo, G.F.D.; Kyriakidou, M.; Adali, Z.; Xiong, K.; Hailes, R.L.N.; Dahlin, A. Electrically switchable polymer brushes for protein capture and release in biological environments. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2022, 61, e202115745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minko, S.; Müller, M.; Usov, D.; Scholl, A.; Froeck, C.; Stamm, M. Lateral versus Perpendicular Segregation in Mixed Polymer Brushes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 035502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minko, S.; Luzinov, I.; Luchnikov, V.; Müller, M.; Patil, S.; Stamm, M. Bidisperse Mixed Brushes: Synthesis and Study of Segregation in Selective Solvent. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 7268–7279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Charpota, N.; Mei, H.; Terlier, T.; Pietrzak, D.; Stein, G.E.; Verduzco, R. Impact of Processing Effects on Surface Segregation of Bottlebrush Polymer Additives. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 8909–8917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, H.; Laws, T.S.; Mahalik, J.P.; Li, J.; Mah, A.H.; Terlier, T.; Bonnesen, P.; Uhrig, D.; Kumar, R.; Stein, G.E.; others, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Entropy and enthalpy mediated segregation of bottlebrush copolymers to interfaces. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 8910–8922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalik, J.P.; Sumpter, B.G.; Kumar, R. Vertical phase segregation induced by dipolar interactions in planar polymer brushes. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 7096–7107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesheuvel, P.; de Vos, W.; Amoskov, V. Semianalytical Continuum Model for Nondilute Neutral and Charged Brushes Including Finite Stretching. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 6254–6259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisov, O.; Zhulina, E.; Birshtein, T. Diagram of the States of a Grafted Polyelectrolyte Layer. Macromolecules 1994, 27, 4795–4803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhulina, E.; Birshtein, T.; Borisov, O. Theory of Ionizable Polymer Brushes. Macromolecules 1995, 28, 1491–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehtiati, K.; Moghaddam, S.; Klok, H.A.; Daugaard, A.; Thormann, E. Specific Counterion Effects on the Swelling Behavior of Strong Polyelectrolyte Brushes. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 5123–5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Merlitz, H.; He, S.Z.; Wu, C.X.; Sommer, J.U. Polyelectrolyte Brushes: Debye Approximation and Mean-Field Theory. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 3109–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, Y.; Auroy, P.; Auvray, L. Density Profile of Polyelectrolyte Brushes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 2863–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houbenov, N.; Minko, S.; Stamm, M. Mixed Polyelectrolyte Brush from Oppositely Charged Polymers for Switching of Surface Charge and Composition in Aqueous Environment. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 5897–5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonforte, F.; Müller, M. Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-Based Mixed Brushes: A Computer Simulation Study. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 12450–12462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratek-Skicki, A.; Eloy, P.; Morga, M.; Dupont-Gillain, C. Reversible Protein Adsorption on Mixed PEO/PAA Polymer Brushes: Role of Ionic Strength and PEO Content. angmuir 2018, 34, 3037–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witte, K.; Won, Y.Y. Self-Consistent-Field Analysis of Mixed Polyelectrolyte and Neutral Polymer Brushes. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 7757–7768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Schee, H.; Lyklema, J. A lattice theory of polyelectrolyte adsorption. J.Phys.Chem. 1984, 88, 6661–6667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, O.; Fleer, G.; Scheutjens, J.; J. , L. Adsorption of weak polyelectrolytes from aqueous solution. J.Colloid Interface Sci. 1986, 111, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).