Introduction

Aquaculture is a rapidly developing sector, experiencing significant annual growth rates. Currently, global inland aquaculture produces 50 million tons of food annually (FAO, 2022). This growth has been fueled by declining natural fisheries, increasing per capita incomes, and a growing demand for aquatic animal protein (FAO, 2020). Additionally, the sector’s expansion is closely tied to ongoing advancements in technology and methodology, particularly with recirculating systems (Naylor et al., 2021).

Pathogen spread and disease emergence are growing global concerns for aquaculture managers, both in open and recirculating aquaculture settings. Disease outbreaks in aquaculture is an estimated annual loss of USD 6 billion globally (World Bank, 2014). Similar to other animal farming industries, these outbreaks are influenced by various factors, including operational practices, rearing densities (Saraiva et al. 2022), biosecurity measures, environmental parameters (e.g., water quality), and stock properties (e.g., limited genetic diversity) (Wright et al., 2023).

However, predicting, detecting, and treating diseases in aquaculture presents unique challenges, compared to other animal-farming industries. First, aquaculture involves over 400 evolutionarily and behaviorally distinct species (Stentiford et al., 2022). which may response differently to similar conditions. For example, Atlantic salmon Salmo salar reared at high densities exhibit increased stress and susceptibility to disease (Ellison et al., 2020), while the opposite is observed in the territorial Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus (Ellison et al., 2018). Second, the underwater environment and the limited behavioral responses of fish to stress, pain, and disease complicate detection through visual and behavioral assessments. As a result, disease detection often occurs after the opportunity for rapid treatment has passed (Rupp et al., 2019), potentially leading to significant stock losses during full outbreaks. Additionally, many aquatic pathogens lack specific, consumer-safe treatments (Cain, 2022). Therefore, prevention and early detection methods are crucial lines of defense, making tools that support early detection essential for the sector’s continued and sustainable growth.

Disease management should extend beyond individual pathogenic species to encompass the study of entire microbial communities, especially in recirculating facilities. Analyzing the complete microbial community, including its overall composition, interactions between or within microbial species, and their competition for space and resources, is crucial for system (Lee et al., 2023) and animal health (Almeida et al., 2021). Understanding the structure and function of these microbial communities opens up opportunities for implementing specific microbial amendments and probiotics (Bentzon-Tilia et al., 2016; Verschuere et al., 2000; El-Saadony et al., 2021), enhancing immune system responses (De Schryver & Vadstein, 2014; Yang et al., 2020), fostering biocontrol mechanisms (Khan et al., 2019), and creating conditions that are unfavorable for pathogens (Yang et al., 2020).

Three current obstacles to early pathogen detection and rapid response in aquaculture include: (1) the requirement for access to and collaboration with diagnostic laboratories, often located off-site, necessitating the transport of delicate samples; (2) the requirement for controlled conditions and specialized infrastructure for diagnostics, such as costly equipment, cold chains, and temperature-sensitive reagents; and (3) the requirement to catch and handle the reared animal for sampling, which is time-consuming and raises animal welfare concerns. These challenges are particularly pronounced in contexts where diagnostic laboratories are scare, time is limited, and resources are constrained.

Below, we outline three key advancements: (1) point-of-care technology enables on-site detection of microorganisms, effectively “bringing the lab to the farm”, (2) field-compatible molecular methods reduce the need for tightly controlled environmental conditions, achieving “independence from lab infrastructure”, and (3) utilizing environmental samples instead of farmed animal samples minimizes the need for animal handling, allowing detection to “move away from animal handling.” Together, these innovations are expected to decrease the time and effort required for pathogen detection, enhance access to molecular methods, and facilitate rapid, precise management responses. They empower farms to conduct certain tests independently, enable veterinarians to perform more advanced analyses on-site, and could be integrated into mobile labs that travel between farms. Additionally, we discuss the potential applications of two research developments in aquaculture: CRISPR-Cas and sequenced-based community analyses.

Our aim is not to instruct aquaculture managers in these methods, but to summarize current possibilities, spark ideas, and foster collaboration between trained molecular scientists and aquaculture managers. This collaboration seeks to bridge the gap between fundamental and applied aquaculture research. Ultimately, integrating advanced methods for rapid pathogen monitoring and comprehensive community analysis will enhance disease prevention and improve the health of both farmed animals and the environment.

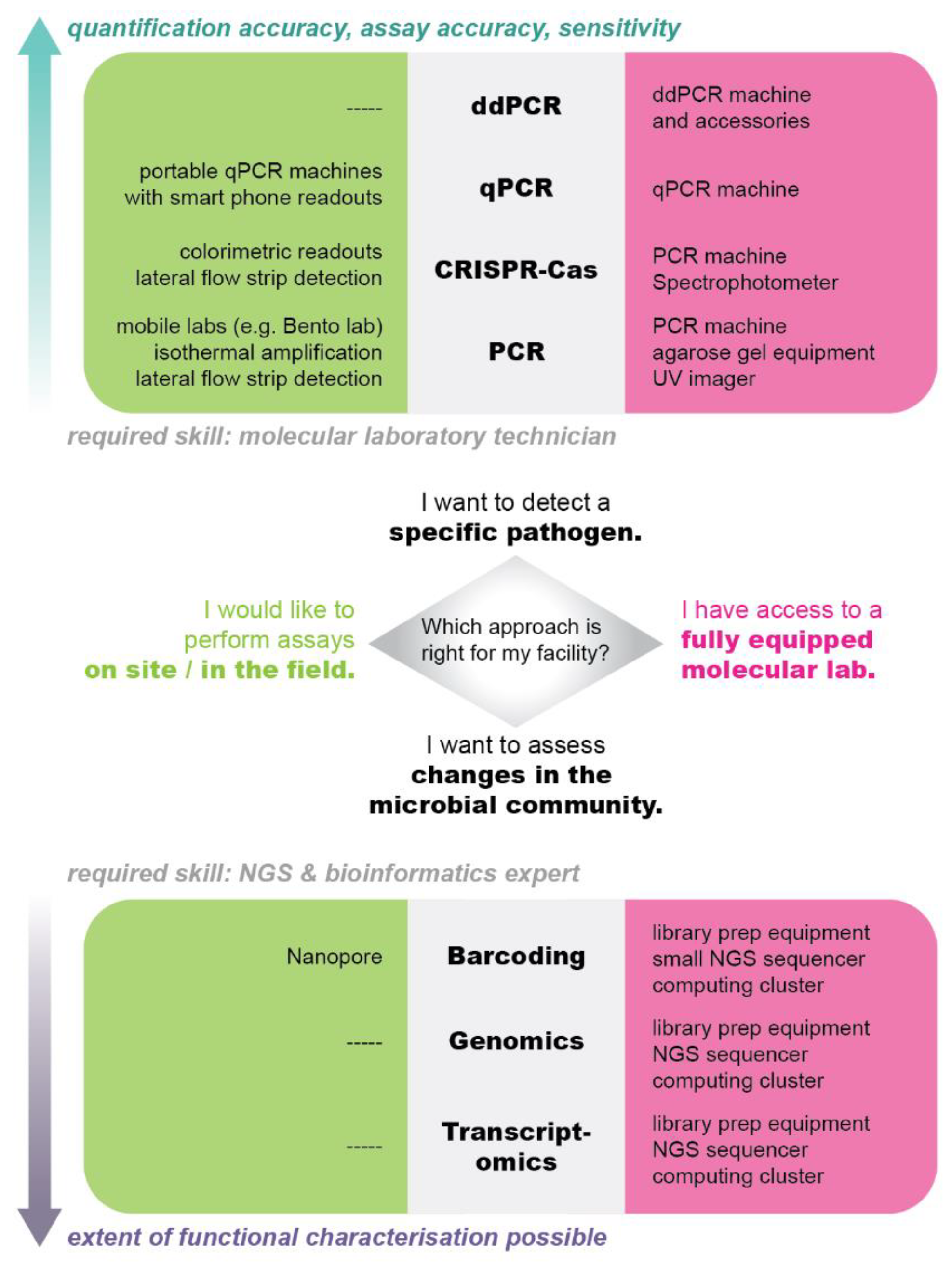

Figure 1.

Overview of current detection options. Based on whether the aim is the detection of individual pathogen species or the characterization of the entire microbial community, whether a fully equipped laboratory is an option, or field-compatible on-site methods are better suited, and whether bioinformatic expertise is available, managers can choose the approach best suited for their needs.

Figure 1.

Overview of current detection options. Based on whether the aim is the detection of individual pathogen species or the characterization of the entire microbial community, whether a fully equipped laboratory is an option, or field-compatible on-site methods are better suited, and whether bioinformatic expertise is available, managers can choose the approach best suited for their needs.

Bringing the Lab to the Farm

In recent years, there has been a significant development of automated, miniaturized, downscaled, and affordable laboratory equipment by start-up companies. This innovation has primarily been driven by needs in three research areas: human epidemiology in countries of the global south, the environmental DNA field, and molecular ecology. These demands have spearheaded the development of microfluidic devices (Kulkarni & Goel, 2020), portable qPCR machines (e.g., Bento Lab

https://bento.bio/), and handheld DNA sequencing devices (e.g., Nanopore MinION), as well as complete field laboratories, including “lab in a bag” options or automobiles converted to fully functional labs (e.g., EMBL Mobile Service (

https://www.embl.org/about/info/trec/mobile-labs/). The objective of these on-site solutions is to reduce turnaround times, minimize the risk of sample loss or damage during transportation, and enable molecular diagnostics in areas lacking centralized laboratory infrastructure.

Devices and solutions capable of rapidly identifying or ruling out specific pathogens are of particular interest in aquaculture, as they facilitate timely and disease-appropriate responses, such as treatment or quarantine of affected units. Devices and solutions capable of portable (q)PCR functionality hold significant potential in this regard. These devices use the same reagents as standard laboratory (q)PCR machines, allowing for straightforward adaptation of well-established assays. However, the primary trade-off associated with miniaturization is reduced sample throughput. In contrast to traditional 96-well formats, portable machines accommodate fewer simultaneous reactions; for instance, the Bio Molecular Systems Mic can process 48 samples, the Biomeme Franklin handles 9 samples, and the Aqua Kit processes 16 samples.

Fortunately, throughput is typically not a limiting factor in point-of-care testing, as a small number of samples is generally sufficient for effective pathogen detection (Nguyen et al. 2018). Portable qPCR machines are characterized by their lightweight, compact design, and often reduced cost. For example, the footprint dimensions of the Biomeme Franklin and the Bio Molecular Systems Mic are 101.3 mm × 182 mm × 89.8 mm and 130 mm × 150 mm × 150 mm, respectively, with weights of 1.2 kg and 2 kg. Additionally, these portable systems offer rapid turnaround times (less than 60 minutes per run), and certain models may not require regular calibration services or access to plug-in electricity, particularly battery-operated variants.

An illustrative application of portable amplification devices in aquaculture is demonstrated by Bio-Key nqPCR

1, a China-based company that has co-engineered field-appropriate qPCR kits tailored for the identification of prevalent aquatic pathogens, using portable qPCR machines such as the Biomeme. Currently, Bio-Key qPCR kits are tailored to detect well-known aquaculture pathogens, including Shrimp Hemocyte Iridescent Virus (SHIV), Vibrio spp., and Infectious Hypodermal Hematopoietic Necrosis virus

2.

When animals exhibit signs of illness, but the causative agent remains unidentified, there is a need for solutions that can detect novel or unknown pathogens. In this context, portable sequencers, particularly the Nanopore MinION, present significant potential (Urban et al., 2021). The MinION is a cost-effective portable sequencing device, with a Nanopore Flongle flow cell run priced at approximately USD 90 for viral and bacterial sequencing. However, successful sequencing requires relatively high-quality DNA, and data interpretation may necessitate a certain level of expertise (Bloemen et al., 2023), thus collaboration with a trained molecular ecologist is recommended. An application example for portable sequencing in the aquaculture sector is the rapid and precise sequencing of salmonid alphavirus and infectious salmon anaemia virus - two viruses with significant implications for global salmonid aquaculture - as demonstrategd by by Gallagher et al. (2018). A more general overview of this technology’s applications is provided by Delamare-Deboutteville (2021).

Both specific detection and sequencing processes can be integrated into microfluidic workflows. These miniaturized platforms facilitate the precise manipulation and analysis of small fluid volumes, allowing for the sequential combination of multiple steps in molecular protocols - such as sample preparation, nucleic acid amplification, and detection - within a single chip or cartridge. See review by Gorgannezhad et al. (2019) for a more in-depth discussion of designs and options. Application examples for microfluidics-based pathogen detection in aquaculture encompass a variety organisms, including decapod iridescent virus 1 (DIV1), white spot syndrome virus (WSSV), infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus, infectious spleen kidney necrosis virus, koi herpesvirus, and Iridovirus, as well as the Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei parasite and various bacteria, such as Aeromonas hydrophila, Edwardsiella tarda, Vibrio harveyi, V. alginolyticus, V. anguillarum, V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Chang et al., 2013; Xiao et al., 2021; Guptha Yedire et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023).

Independence from Controlled Environments

In recent years, protocols facilitating molecular analyses under field conditions have been developed. Traditional molecular assays are often sensitive to environmental parameters, as the enzymes involved typically require stringent cooling chains to maintain activity or rely on precisely controlled temperature sequences for effective DNA amplification. Additionally, the results usually necessitate sophisticated machinery for analysis. The increasing need for on-site pathogen surveillance in human health programs in remote areas (Song et al., 2022) have driven the advancement in the development of enzymes capable of surviving lyophilization, allowing for transportation and storage at room temperature or refrigeration. Furthermore, there is a growing focus on assays that operate at constant (“isothermal”) temperatures that are easily achievable, as well as those that can be assessed visually through color changes.

Lyophilization, or freeze-drying, enhances independence from stringent cooling chains. Traditional PCR and qPCR reagents lose activity at temperatures above -20°C. However, when lyophilized, PCR assays containing all necessary reagents and enzymes can be transported and stored at room temperature, requiring only reconstitution with water on-site prior to use (Rieder et al., 2022). An additional advantage of lyophilization is that central laboratories can prepare quality-controlled reaction batches, which can then be shipped to the end-users and stored on-site for extended periods (Rieder et al., 2022). Consequently, lyophilization is particularly advantageous in resource-limited or remote settings that lack continuous access to freezer capacity.

Isothermal amplification eliminates the need for the precise cycling and high temperatures required in traditional PCR and qPCR assays. Isothermal polymerases function at constant, lower temperatures that can be achieved using incubators, water baths, or even body heat. Two isothermal protocols are currently available, loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) and recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA). RPA functions at 37°C (M. A. Williams et al., 2022), while LAMP operates at 65°C (Notomi et al., 2000). Both methods are time-efficient (< 60 min) (Sullivan et al., 2019; Notomi et al., 2000) and sensitive enough to detect low copy numbers of DNA (e.g., ~1.06 copies for white spot syndrome virus) (Sullivan et al., 2019). Furthermore, these techniques can be integrated with microfluidic devices (Giuffrida & Spoto, 2017; Kant et al., 2018). Additional applications of isothermal methods in aquaculture include the use of LAMP to detect Vibrio parahaemolyticus (Anupama et al., 2020) and V. vulnificus (Z. Tian et al., 2022), both of which are known fish pathogens (Novoslavskij et al., 2016).

RPA has been used to detect various viruses, including Penaeus stylirostris denso virus (Jaroenram & Owens, 2014), infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus (Xia et al., 2015), Cyprinid Herpes virus-3 (Prescott et al., 2016), abalone herpes-like virus, red-spotted grouper nervous necrosis virus (Gao et al., 2018), bacteria such as Flavobacterium columnare (Mabrok et al., 2021), and Edwardsiella ictalurid (H. Li et al., 2022), V. parahaemolyticus (Geng et al., 2019), Francisella noatunensis subsp. Orientalis (Shahin et al., 2018), and the parasite Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae (Soliman et al., 2018). Based on personal experience, false positives may occur with RPA, although this likely depends on the species and specific assay setup.

Finally, colorimetric readouts facilitate independence from machine-dependent result interpretation by providing direct, visually perceptible outputs. Currently, two options are available: lateral flow strips, which exhibit a color change in a specific section (typically a narrow band) when a target is detected and liquid colorimetric assays, where the entire reaction volume changes color with detection. This human-readable output eliminated the need for expensive and sensitive spectrophotometers or fluorometers typically required for standard laboratory assays. Examples of colorimetric readouts in the aquaculture sector include a study by Morsy et al. (2016), who developed a colormetric assay for monitoring food spoilage during fish and meat processing. Additional applications include assays for the detection of fish pathogens, such as largemouth bass ranavirus (Jin et al., 2020) and Flavobacterium columnare (Suebsing et al., 2015).

Moving Away from Fish Handling

Monitoring fish health in aquaculture traditionally requires the capture, examination, and often sacrifice of healthy animals for routine checks. This practice is time-consuming, necessitating significant personnel resources, and conflicts with animal welfare principles aimed at reducing stress and suffering. In contrast, the assessment of pathogen presence and abundance from environmental samples (such as water or swabs) is non-invasive, equally sensitive, and aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2016) as well as the 3Rs objectives (Replace, Reduce, and Refine) for animal welfare.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) and RNA (eRNA) approaches, which detect species from various environmental matrices, including water, soil, plants, and air, are currently revolutionizing both ecological research and pathogen surveillance (Bass et al., 2023). In the aquaculture sector, eDNA methodologies can enhance biosecurity measures (Bohara et al., 2022) by targeting potential contamination sources, such as transport water. For instance, newly imported fish could be placed under quarantine until the screening of transport water yields negative results for specific pathogens.

Examples of eDNA applications in aquaculture include assays for ectoparasitic flukes such as Gyrodactylus salaris (Fossøy et al., 2020), Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae (Sieber et al., 2020), and Flavobacterium psychrophilum (Nguyen et al., 2018). Additionally, eRNA, a more recent development that detects pathogens that are not only present but also actively pathogenic, has been employed to identify Bonamia ostreae, a protozoan parasite responsible for significant mortality in flat oyster (Ostrea edulis) populations (Mérou et al., 2020). Importantly, eDNA and eRNA approaches can benefit from advancements in miniaturization, automation, and integration with colorimetric readouts, isothermal amplification, and field compatibility, like those applied in PCR and qPCR methodologies.

Transfer of CRISPR Technology to Aquaculture

CRISPR is widely recognized for its capabilities in genome editing but has more recently been adapted for the development of highly specific diagnostic assays. CRISPR-based detection represented a valid, target-specific alternative to PCR and qPCR-based amplification techniques (Phelps, 2019). Briefly, the CAS protein is initially bound to a signal-and-quencher coupled oligonucleotide probe that is complementary to the nucleotides of the target pathogen, analogous to probes used in a TaqMan assays. When the CAS-bound probe encounters its complementary sequences, it binds and the Cas protein cleaves the probe, releasing the fluorophore, which subsequently emits a signal in its unquenched state. A comprehensive overview of the fundamental principles and relevant considerations for pathogen detection is provided by Tian et al. (2022).

Three promising CRISPR-based detection methods for the aquaculture sector—SHERLOCK, DETECTR, and RAA—are discussed below.

SHERLOCK (Sensitive High Efficiency Reporter Unlocking) integrates isothermal amplification via recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) with highly specific Cas13-based detection of transcribed amplicons, followed by fluorescence reporting (Kellner et al., 2019). Originally developed for detecting human pathogens (Gootenberg et al., 2017), this method requires standard laboratory settings and equipment.

Subsequent protocols, such as SHERLOCKv2 and STOP (SHERLOCK Testing in One Pot), combine loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) with a heat-tolerant Cas12b, rendering them more suitable for field applications. An example of STOP’s application in aquaculture is presented by Major et al. (2023), who employed this method to detect viral targets, including white spot syndrome virus and Taura syndrome virus, in shrimp tissue samples within 30 minutes.

DETECTR (DNA Endonuclease-Targeted CRISPR Trans-Reporter) combines RPA with Cas12a and and has been recently adapted for colorimetric lateral flow strip detection, yielding results in less than 10 minutes (C. Li et al., 2022). This method has demonstrated the ability to differentiate between closely related species (Williams et al., 2019), a capability that is particularly valuable for environmental samples that may contain numerous closely related species, some of which may be pathogenic while others are harmless.

Application examples of DETECTR in aquaculture include its use in detecting scale-drop disease (Sukonta et al., 2022), Hepatopancreatic Microsporidiosis (Kanitchinda et al., 2020), and Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease (C. Li et al., 2022). Notably, the detection of Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease has been engineered into a one-step procedure (Wang et al., 2023).

Table 1.

Overview of CRISPR-based technologies describing the benefits and flexibility of different methods and proteins involved.

Table 1.

Overview of CRISPR-based technologies describing the benefits and flexibility of different methods and proteins involved.

| METHOD |

PROTEINS |

AMPLIFICATION |

DETECTION |

TARGET |

SENSITIVITY |

TIME |

REF |

| SHERLOCKV1 |

Cas13a |

RPA |

Fluorescence,

Colorimetry |

DNA/

RNA |

1.06 copies

(10 copies /colorimetry) |

60 mins |

Sullivan, 2019 |

| SHERLOCKV2 |

Cas12b |

LAMP |

Fluorescence |

DNA/

RNA |

100 copies |

30- 60 mins |

Major, 2023 |

| DETECTR |

Cas12a |

RPA |

Fluorescence, Colorimetry |

DNA |

40 copies

(200 copies/

colorimetry) |

|

Li, 2022 |

RAA-CRISPR/

CAS12A |

Cas12a |

RAA |

Fluorescence |

DNA |

2 copies |

40 mins |

Xiao, 2021 |

RAA (Recombinase-Assisted Amplification CRISPR-CAS) is an adaptation of the DETECTR method that requires approximately 40 minutes to complete and allows for analysis under UV light. An application example of RAA in aquaculture is the detection of Vibrio vulnificus, the causative agent of vibriosis (Xiao et al., 2021).

In summary, CRISPR-based diagnostics represent a highly specific, sensitive, fast and potentially low-resource approach for detecting specific candidate pathogens. Future developments are likely to include quantitative assessments of pathogen abundance in addition to detection/non-detection determinations. Technical innovations from human diagnostics, such as smartphone-based fluorescence readers for CRISPR detection from human diagnostics (Samacoits et al., 2021), could further enhance the feasibility of on-site implementation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, field-compatible methodologies, techniques from the eDNA field, and community-targeting approaches exhibit significant potential for pathogen surveillance in aquaculture. The scientific field is currently experiencing a revolution in point-of-care diagnostics and on-site pathogen monitoring, characterized by innovations that enable lab-free, fish-free, and refrigeration-free detection, identification, and characterization of pathogens. Furthermore, community sequencing techniques offer unprecedented insights into how management interventions, cleaning protocols, stocking cycles, and other operational practices influence the microbial community of tanks and biofilters. Familiarity with these methods and their potential applications will equip the next generation of aquaculture managers to implement timely and targeted interventions and enhance their pathogen management strategies.

Ethics and integrity statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relating to this manuscript. No animals were used to produce the manuscript. As a perspective piece, it does not contain any data. The work was funded by SNF grant 204838 “MiCo4Sys – Microbial Community Composition and Colonization in Compartmentalized Aquaculture Systems”.

Author contributions

JR conceptualized and drafted the manuscript, AB contributed to literature search and specific sections, all authors contributed to review and editing, IAK performed visualisation and supervision, JR and IAK contributed to funding acquisition.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Heike Schmidt-Posthaus and all members of her team for insightful discussions on aquaculture pathogens and practices, and to many aquaculture farms in Switzerland who provided insights into their operating practices.

References

- Almeida, D. B., Magalhães, C., Sousa, Z., Borges, M. T., Silva, E., Blanquet, I., & Mucha, A. P. (2021). Microbial community dynamics in a hatchery recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) of sole (Solea senegalensis). Aquaculture, 539. [CrossRef]

- Anupama, K. P. , Nayak, A., Karunasagar, I., & Maiti, B. (2020). Rapid visual detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in seafood samples by loop-mediated isothermal amplification with hydroxynaphthol blue dye. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 36(5), Article 5. [CrossRef]

- Bakke, I. , Åm, A. L., Kolarevic, J., Ytrestøyl, T., Vadstein, O., Attramadal, K. J. K., & Terjesen, B. F. (2017). Microbial community dynamics in semi-commercial RAS for production of Atlantic salmon post-smolts at different salinities. Aquacultural Engineering, 78, 42–49. [CrossRef]

- Bass, D. , Christison, K. W., Stentiford, G. D., Cook, L. S. J., & Hartikainen, H. (2023). Environmental DNA/RNA for pathogen and parasite detection, surveillance, and ecology. Trends in Parasitology, 39(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Bastos Gomes, G., Hutson, K. S., Domingos, J. A., Chung, C., Hayward, S., Miller, T. L., & Jerry, D. R. (2017). Use of environmental DNA (eDNA) and water quality data to predict protozoan parasites outbreaks in fish farms. Aquaculture, 479, 467–473. [CrossRef]

- Bentzon-Tilia, M. , Sonnenschein, E. C., & Gram, L. (2016). Monitoring and managing microbes in aquaculture – Towards a sustainable industry. Microbial Biotechnology, 9(5), Article 5. [CrossRef]

- Bloemen, B. , Gand, M., Vanneste, K., Marchal, K., Roosens, N. H. C., & De Keersmaecker, S. C. J. (2023). Development of a portable on-site applicable metagenomic data generation workflow for enhanced pathogen and antimicrobial resistance surveillance. Scientific Reports, 13(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Bohara, K. , Yadav, A. K., & Joshi, P. (2022). Detection of Fish Pathogens in Freshwater Aquaculture Using eDNA Methods. Diversity, 14(12), Article 12. [CrossRef]

- Cain, K. (2022). The many challenges of disease management in aquaculture. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society, 53(6), 1080–1083. [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.-H. , Yang, S.-Y., Wang, C.-H., Tsai, M.-A., Wang, P.-C., Chen, T.-Y., Chen, S.-C., & Lee, G.-B. (2013). Rapid isolation and detection of aquaculture pathogens in an integrated microfluidic system using loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 180, 96–106. [CrossRef]

- De Schryver, P. , & Vadstein, O. (2014). Ecological theory as a foundation to control pathogenic invasion in aquaculture. The ISME Journal, 8(12), Article 12. [CrossRef]

- Delamare-Deboutteville, J. (2021). Uncover aquaculture pathogens identity using Nanopore MinION.pdf. https://digitalarchive.worldfishcenter.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12348/4931/eb0411d2c9e634acfae22ee2db9e7391.pdf?sequence2=.

- Ellison, A. R. , Uren Webster, T. M., Rey, O., Garcia de Leaniz, C., Consuegra, S., Orozco-terWengel, P., & Cable, J. (2018). Transcriptomic response to parasite infection in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) depends on rearing density. BMC Genomics, 19(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Ellison, A. R. , Uren Webster, T. M., Rodriguez-Barreto, D., de Leaniz, C. G., Consuegra, S., Orozco-terWengel, P., & Cable, J. (2020). Comparative transcriptomics reveal conserved impacts of rearing density on immune response of two important aquaculture species. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 104, 192–201. [CrossRef]

- El-Saadony, M. T. , Alagawany, M., Patra, A. K., Kar, I., Tiwari, R., Dawood, M. A. O., Dhama, K., & Abdel-Latif, H. M. R. (2021). The functionality of probiotics in aquaculture: An overview. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 117, 36–52. [CrossRef]

- FAO. (2020). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020. In brief. FAO. [CrossRef]

- FAO. (2022). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022. FAO. [CrossRef]

- Fossøy, F. , Brandsegg, H., Sivertsgård, R., Pettersen, O., Sandercock, B. K., Solem, Ø., Hindar, K., & Mo, T. A. (2020). Monitoring presence and abundance of two gyrodactylid ectoparasites and their salmonid hosts using environmental DNA. Environmental DNA, 2(1), 53–62. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, M. D. , Matejusova, I., Nguyen, L., Ruane, N. M., Falk, K., & Macqueen, D. J. (2018). Nanopore sequencing for rapid diagnostics of salmonid RNA viruses. Scientific Reports, 8(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Gao, F. , Jiang, J.-Z., Wang, J.-Y., & Wei, H.-Y. (2018). Real-time isothermal detection of Abalone herpes-like virus and red-spotted grouper nervous necrosis virus using recombinase polymerase amplification. Journal of Virological Methods, 251, 92–98. [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y. , Tan, K., Liu, L., Sun, X. X., Zhao, B., & Wang, J. (2019). Development and evaluation of a rapid and sensitive RPA assay for specific detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in seafood. BMC Microbiology, 19(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, M. C. , & Spoto, G. (2017). Integration of isothermal amplification methods in microfluidic devices: Recent advances. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 90, 174–186. [CrossRef]

- Gootenberg, J. S. , Abudayyeh, O. O., Lee, J. W., Essletzbichler, P., Dy, A. J., Joung, J., Verdine, V., Donghia, N., Daringer, N. M., Freije, C. A., Myhrvold, C., Bhattacharyya, R. P., Livny, J., Regev, A., Koonin, E. V., Hung, D. T., Sabeti, P. C., Collins, J. J., & Zhang, F. (2017). Nucleic acid detection with CRISPR-Cas13a/C2c2. Science (New York, N.Y.), 356(6336), 438–442. [CrossRef]

- Gorgannezhad, L. , Stratton, H., & Nguyen, N.-T. (2019). Microfluidic-Based Nucleic Acid Amplification Systems in Microbiology. Micromachines, 10(6), Article 6. [CrossRef]

- Guptha Yedire, S. , Khan, H., AbdelFatah, T., Moakhar, R. S., & Mahshid, S. (2023). Microfluidic-based colorimetric nucleic acid detection of pathogens. Sensors & Diagnostics. [CrossRef]

- Hook, S. E., White, C., & Ross, D. J. (2021). A metatranscriptomic analysis of changing dynamics in the plankton communities adjacent to aquaculture leases in southern Tasmania, Australia. Marine Genomics, 59, 100858. [CrossRef]

- Jaroenram, W. , & Owens, L. (2014). Recombinase polymerase amplification combined with a lateral flow dipstick for discriminating between infectious Penaeus stylirostris densovirus and virus-related sequences in shrimp genome. Journal of Virological Methods, 208, 144–151. [CrossRef]

- Jin, R. , Zhai, L., Zhu, Q., Feng, J., & Pan, X. (2020). Naked-eyes detection of Largemouth bass ranavirus in clinical fish samples using gold nanoparticles as colorimetric sensor. Aquaculture, 528, 735554. [CrossRef]

- Kanitchinda, S. , Srisala, J., Suebsing, R., Prachumwat, A., & Chaijarasphong, T. (2020). CRISPR-Cas fluorescent cleavage assay coupled with recombinase polymerase amplification for sensitive and specific detection of Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei. Biotechnology Reports, 27, e00485. [CrossRef]

- Kant, K. , Shahbazi, M.-A., Dave, V. P., Ngo, T. A., Chidambara, V. A., Than, L. Q., Bang, D. D., & Wolff, A. (2018). Microfluidic devices for sample preparation and rapid detection of foodborne pathogens. Biotechnology Advances, 36(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Kellner, M. J. , Koob, J. G., Gootenberg, J. S., Abudayyeh, O. O., & Zhang, F. (2019). SHERLOCK: Nucleic acid detection with CRISPR nucleases. Nature Protocols, 14(10), Article 10. [CrossRef]

- Khan, R., Petersen, F. C., & Shekhar, S. (2019). Commensal Bacteria: An Emerging Player in Defense Against Respiratory Pathogens. Frontiers in Immunology, 10. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01203.

- Kulkarni, M. B. , & Goel, S. (2020). Advances in continuous-flow based microfluidic PCR devices—A review. Engineering Research Express, 2(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. D., Pedroso, A. A., & Maurer, J. J. (2023). Bacterial composition of a competitive exclusion product and its correlation with product efficacy at reducing Salmonella in poultry. Frontiers in Physiology, 13. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2022.1043383.

- Li, C., Lin, N., Feng, Z., Lin, M., Guan, B., Chen, K., Liang, W., Wang, Q., Li, M., You, Y., & Chen, Q. (2022). CRISPR/Cas12a Based Rapid Molecular Detection of Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease in Shrimp. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2021.819681.

- Li, H. , Zhang, L., Yu, Y., Ai, T., Zhang, Y., & Su, J. (2022). Rapid detection of Edwardsiella ictaluri in yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) by real-time RPA and RPA-LFD. Aquaculture, 552, 737976. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. , Han, G., Li, Z., Cun, S., Hao, B., Zhang, J., & Liu, X. (2022). Bacteriophage therapy in aquaculture: Current status and future challenges. Folia Microbiologica, 67(4), 573–590. [CrossRef]

- Mabrok, M. , Elayaraja, S., Chokmangmeepisarn, P., Jaroenram, W., Arunrut, N., Kiatpathomchai, W., Debnath, P. P., Delamare-Deboutteville, J., Mohan, C. V., Fawzy, A., & Rodkhum, C. (2021). Rapid visualization in the specific detection of Flavobacterium columnare, a causative agent of freshwater columnaris using a novel recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) combined with lateral flow dipstick (LFD) assay. Aquaculture, 531, 735780. [CrossRef]

- Major, S. R. , Harke, M. J., Cruz-Flores, R., Dhar, A. K., Bodnar, A. G., & Wanamaker, S. A. (2023). Rapid Detection of DNA and RNA Shrimp Viruses Using CRISPR-Based Diagnostics. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 89(6), e02151-22. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Porchas, M. , & Vargas-Albores, F. (2017). Microbial metagenomics in aquaculture: A potential tool for a deeper insight into the activity. Reviews in Aquaculture, 9(1), 42–56. [CrossRef]

- Mérou, N. , Lecadet, C., Pouvreau, S., & Arzul, I. (2020). An eDNA/eRNA-based approach to investigate the life cycle of non-cultivable shellfish micro-parasites: The case of Bonamia ostreae, a parasite of the European flat oyster Ostrea edulis. Microbial Biotechnology, 13(6), 1807–1818. [CrossRef]

- Morsy, M. K., Zór, K., Kostesha, N., Alstrøm, T. S., Heiskanen, A., El-Tanahi, H., Sharoba, A., Papkovsky, D., Larsen, J., Khalaf, H., Jakobsen, M. H., & Emnéus, J. (2016). Development and validation of a colorimetric sensor array for fish spoilage monitoring. Food Control, 60, 346–352. [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R. L. , Hardy, R. W., Buschmann, A. H., Bush, S. R., Cao, L., Klinger, D. H., Little, D. C., Lubchenco, J., Shumway, S. E., & Troell, M. (2021). A 20-year retrospective review of global aquaculture. Nature, 591(7851), Article 7851. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P. L. , Sudheesh, P. S., Thomas, A. C., Sinnesael, M., Haman, K., & Cain, K. D. (2018). Rapid Detection and Monitoring of Flavobacterium psychrophilum in Water by Using a Handheld, Field-Portable Quantitative PCR System. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health, 30(4), 302–311. [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, T. , & Botelho, A. (2021). Metagenomics and other omics approaches to bacterial communities and antimicrobial resistance assessment in aquacultures. Antibiotics, 10(7). [CrossRef]

- Notomi, T. , Okayama, H., Masubuchi, H., Yonekawa, T., Watanabe, K., Amino, N., & Hase, T. (2000). Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Research, 28(12), Article 12. [CrossRef]

- Novoslavskij, A. , Terentjeva, M., Eizenberga, I., Valciņa, O., Bartkevičs, V., & Bērziņš, A. (2016). Major foodborne pathogens in fish and fish products: A review. Annals of Microbiology, 66(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Phelps, M. (2019). Increasing eDNA capabilities with CRISPR technology for real-time monitoring of ecosystem biodiversity. Molecular Ecology Resources, 19(5), 1103–1105. [CrossRef]

- Prescott, M. A. , Reed, A. N., Jin, L., & Pastey, M. K. (2016). Rapid Detection of Cyprinid Herpesvirus 3 in Latently Infected Koi by Recombinase Polymerase Amplification. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health, 28(3), Article 3. [CrossRef]

- Rey-Campos, M. , Ríos-Castro, R., Gallardo-Escárate, C., Novoa, B., & Figueras, A. (2022). Exploring the Potential of Metatranscriptomics to Describe Microbial Communities and Their Effects in Molluscs. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(24), 16029. [CrossRef]

- Rieder, J., Kapopoulou, A., Bank, C., & Adrian-Kalchhauser, I. (2023). Metagenomics and metabarcoding experimental choices and their impact on microbial community characterization in freshwater recirculating aquaculture systems. Environmental Microbiome, 18(1), 8. [CrossRef]

- Rieder, J. , Martin-Sanchez, P. M., Osman, O. A., Adrian-Kalchhauser, I., & Eiler, A. (2022). Detecting aquatic pathogens with field-compatible dried qPCR assays. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 202, 106594. [CrossRef]

- Rupp, M. , Pilo, P., Müller, B., Knüsel, R., von Siebenthal, B., Frey, J., Sindilariu, P.-D., & Schmidt-Posthaus, H. (2019). Systemic infection in European perch with thermoadapted virulent Aeromonas salmonicida (Perca fluviatilis). Journal of Fish Diseases, 42(5), Article 5. [CrossRef]

- Samacoits, A. , Nimsamer, P., Mayuramart, O., Chantaravisoot, N., Sitthi-amorn, P., Nakhakes, C., Luangkamchorn, L., Tongcham, P., Zahm, U., Suphanpayak, S., Padungwattanachoke, N., Leelarthaphin, N., Huayhongthong, H., Pisitkun, T., Payungporn, S., & Hannanta-anan, P. (2021). Machine Learning-Driven and Smartphone-Based Fluorescence Detection for CRISPR Diagnostic of SARS-CoV-2. ACS Omega, 6(4), 2727–2733. [CrossRef]

- Shahin, K. , Gustavo Ramirez-Paredes, J., Harold, G., Lopez-Jimena, B., Adams, A., & Weidmann, M. (2018). Development of a recombinase polymerase amplification assay for rapid detection of Francisella noatunensis subsp. Orientalis. PloS One, 13(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Sieber, N. , Hartikainen, H., & Vorburger, C. (2020). Validation of an eDNA-based method for the detection of wildlife pathogens in water. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 141, 171–184. [CrossRef]

- Soliman, H. , Kumar, G., & El-Matbouli, M. (2018). Recombinase polymerase amplification assay combined with a lateral flow dipstick for rapid detection of Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae, the causative agent of proliferative kidney disease in salmonids. Parasites & Vectors, 11(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Song, X. , Coulter, F. J., Yang, M., Smith, J. L., Tafesse, F. G., Messer, W. B., & Reif, J. H. (2022). A lyophilized colorimetric RT-LAMP test kit for rapid, low-cost, at-home molecular testing of SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogens. Scientific Reports, 12(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Stentiford, G. D. , Peeler, E. J., Tyler, C. R., Bickley, L. K., Holt, C. C., Bass, D., Turner, A. D., Baker-Austin, C., Ellis, T., Lowther, J. A., Posen, P. E., Bateman, K. S., Verner-Jeffreys, D. W., van Aerle, R., Stone, D. M., Paley, R., Trent, A., Katsiadaki, I., Higman, W. A., … Hartnell, R. E. (2022). A seafood risk tool for assessing and mitigating chemical and pathogen hazards in the aquaculture supply chain. Nature Food, 3(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Suebsing, R. , Kampeera, J., Sirithammajak, S., Withyachumnarnkul, B., Turner, W., & Kiatpathomchai, W. (2015). Colorimetric Method of Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification with the Pre-Addition of Calcein for Detecting Flavobacterium columnare and its Assessment in Tilapia Farms. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health, 27(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Sukonta, T. , Senapin, S., Taengphu, S., Hannanta-anan, P., Kitthamarat, M., Aiamsa-at, P., & Chaijarasphong, T. (2022). An RT-RPA-Cas12a platform for rapid and sensitive detection of tilapia lake virus. Aquaculture, 560, 738538. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, T. J. , Dhar, A. K., Cruz-Flores, R., & Bodnar, A. G. (2019). Rapid, CRISPR-Based, Field-Deployable Detection Of White Spot Syndrome Virus In Shrimp. Scientific Reports, 9(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, B. J. G. , Finke, J. F., Saunders, R., Warne, S., Schulze, A. D., Strohm, J. H. T., Chan, A. M., Suttle, C. A., & Miller, K. M. (2022). Metatranscriptomics reveals a shift in microbial community composition and function during summer months in a coastal marine environment. Environmental DNA. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y., Liu, T., Liu, C., Xu, Q., & Liu, Q. (2022). Pathogen detection strategy based on CRISPR. Microchemical Journal, 174, 107036. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z. , Yang, L., Qi, X., Zheng, Q., Shang, D., & Cao, J. (2022). Visual LAMP method for the detection of Vibrio vulnificus in aquatic products and environmental water. BMC Microbiology, 22(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2016). The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

- Urban, L. , Holzer, A., Baronas, J. J., Hall, M. B., Braeuninger-Weimer, P., Scherm, M. J., Kunz, D. J., Perera, S. N., Martin-Herranz, D. E., Tipper, E. T., Salter, S. J., & Stammnitz, M. R. (2021). Freshwater monitoring by nanopore sequencing. eLife, 10, e61504. [CrossRef]

- Verschuere, L. , Rombaut, G., Sorgeloos, P., & Verstraete, W. (2000). Probiotic Bacteria as Biological Control Agents in Aquaculture. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 64(4), Article 4.

- Wang, P. , Guo, B., Zhang, X., Wang, Y., Yang, G., Shen, H., Gao, S., & Zhang, L. (2023). One-Pot Molecular Diagnosis of Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease by Recombinase Polymerase Amplification and CRISPR/Cas12a with Specially Designed crRNA. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 71(16), 6490–6498. [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. A. , de Eyto, E., Caestecker, S., Regan, F., & Parle-McDermott, A. (2022). Development and field validation of RPA-CRISPR-Cas environmental DNA assays for the detection of brown trout (Salmo trutta) and Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus). Environmental DNA. [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.-A. , O’Grady, J., Ball, B., Carlsson, J., de Eyto, E., McGinnity, P., Jennings, E., Regan, F., & Parle-McDermott, A. (2019). The application of CRISPR-Cas for single species identification from environmental DNA. Molecular Ecology Resources, 19(5), 1106–1114. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2014). Reducing Disease Risk in Aquaculture. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/18936.

- Wright, A. , Li, X., Yang, X., Soto, E., & Gross, J. (2023). Disease prevention and mitigation in US finfish aquaculture: A review of current approaches and new strategies. Reviews in Aquaculture, n/a(n/a), Article n/a. [CrossRef]

- Xia, X. , Yu, Y., Hu, L., Weidmann, M., Pan, Y., Yan, S., & Wang, Y. (2015). Rapid detection of infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHHNV) by real-time, isothermal recombinase polymerase amplification assay. Archives of Virology, 160(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X., Lin, Z., Huang, X., Lu, J., Zhou, Y., Zheng, L., & Lou, Y. (2021). Rapid and Sensitive Detection of Vibrio vulnificus Using CRISPR/Cas12a Combined With a Recombinase-Aided Amplification Assay. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.767315.

- Yang, W., Zheng, Z., Lu, K., Zheng, C., Du, Y., Wang, J., & Zhu, J. (2020). Manipulating the phytoplankton community has the potential to create a stable bacterioplankton community in a shrimp rearing environment. Aquaculture, 520, 734789. [CrossRef]

Notes

| 1 |

https://www.biokeyqpcr.com/supplier-3083726-portable-qpcr-machine. |

| 2 |

https://www.biokeyqpcr.com/quality-27511152-shrimp-tissues-vpa-vibrio-parahaemolyticus-real-time-pcr-detection-kit. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).