1. Introduction

Aquaculture is the fastest-growing sector among the global food production systems. It provides a critical source of protein, employment, and economic development, particularly in developing countries (Naylor, Fang and Fanzo, 2023). Zambia, with its vast water resources and favourable climatic conditions, has experienced significant growth in aquaculture, particularly the production of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), which dominates the local fish farming industry (Hasimuna et al., 2023). As demand for farmed fish continues to rise, the intensification of aquaculture practices has brought about several challenges, such as increased susceptibility to bacterial infections and the widespread use of antibiotics to manage diseases (Pepi and Focardi, 2021).

The use of antibiotics in aquaculture serves as a critical tool to control bacterial diseases and thereby reduce any possible losses that may occur due to high mortality incidence (Ibrahim et al., 2020). However, the abuse of these antibiotics poses significant risks, including the development of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which threatens both fish and human health (Milijasevic et al., 2024). Residues of antibiotics in fish products further raise public health concerns, as they can lead to long-term exposure, allergic reactions, and the development of resistant pathogens in consumers (Ljubojević Pelić et al., 2024). Market-ready fish, such as tilapia, represent a key point of concern, as they are a highly consumed protein source, making it essential to ensure their safety and quality.

Bacterial infections in aquaculture environments are often caused by opportunistic pathogens such as Aeromonas, Pseudomonas, and Vibrio species, which can impact fish health, farm productivity, and food safety (Chatreman, Seecharran and Ansari, 2020). Profiling the microbial diversity, assessing the antibiotic susceptibility of bacterial isolates, and detecting antibiotic residues are essential steps in understanding the scale of these challenges and implementing effective mitigation strategies.

In Zambia's major aquaculture production regions, limited research has been conducted to evaluate the microbiological safety of farmed fish and assess antibiotic residues. This gap necessitates a comprehensive study to provide scientific evidence for guiding policy development, improving farm practices, and ensuring compliance with food safety standards.

This study aimed to profile the microbial communities in market-ready tilapia from key aquaculture regions in Zambia, determine the antibiotic susceptibility patterns of bacterial isolates, and detect the presence of antibiotic residues. The findings provide insights into farmed tilapia's microbiological quality and safety, highlight risks associated with antibiotic misuse, and offer recommendations for sustainable aquaculture practices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The study employed a cross-sectional qualitative design in which market-ready fish were systematically sampled from selected fish farms in the participating districts. This approach allowed for the collection of representative data from various farming operations, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the target population while focusing on specific characteristics relevant to the study objectives.

2.2. Study Area

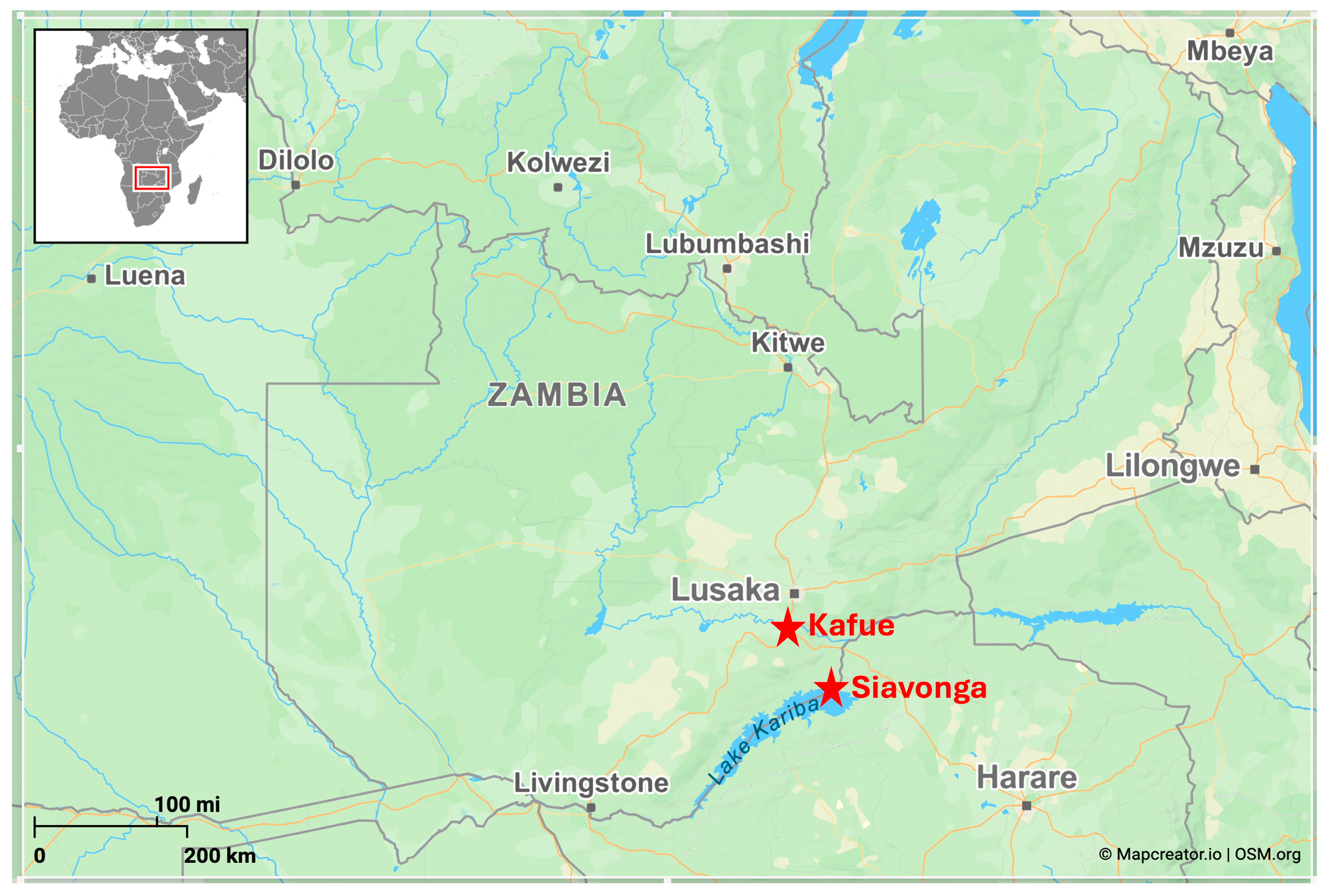

The study was conducted in Kafue and Siavonga districts, which were strategically selected due to their significant contributions to national aquaculture production [

Figure 1]. These locations represent critical nodes in the country's aquaculture sector, with distinct production systems that facilitate a comparative analysis of diverse aquaculture practices. Fish farmers in Kafue district predominantly utilises a pond culture system, whereas in Siavonga they employ a cage culture system, providing a unique opportunity to collect samples from different aquaculture systems that may have different fish health, growth, and productivity statuses. Additionally, both districts encompass a range of aquaculture operations, including small-scale, medium-scale, and large-scale farms, ensuring that the study captures variability across farm sizes and management practices.

The study classified aquaculture farms based on scale and production systems to assess production capacities and market suitability. Large-scale farms included ponds over 1 hectare producing more than 12 metric tonnes (MT) annually or cage systems with over 40 cages yielding over 20 MT, targeting commercial and international markets. Medium-scale farms featured ponds between 2,400 square meters and 1 hectare or 5 to 40 cages, producing 3–12 MT and 12–20 MT annually, respectively, catering to regional markets. Small-scale farms consisted of ponds between 600 and 2,400 square meters or 1 to 5 cages, producing less than 3 MT and 12 MT annually, respectively, focusing on local markets with limited infrastructure and management.

This diverse representation enhanced the robustness of the findings and their applicability to the broader aquaculture industry.

2.3. Sample Size Estimation

A two-stage sampling methodology was employed in Siavonga and Kafue districts to ensure a representative selection of farms and fish samples.

Stage 1: Selection of Farms

The first stage involved the creation of a sampling frame by identifying and evaluating potential fish farms with the assistance of personnel from the district fisheries office. This sampling frame included details on farm-level production capacity, geographical location, and production systems, such as cage, pond, or tank culture. To determine the number of farms to be sampled, a proportional allocation method was applied to ensure representation from different farm sizes and production systems. The number of farms selected (

nf) was calculated as:

where:

Nf = total number of farms in the selected district [Siavonga (25) and Kafue (30)]

N = total number of registered farms in both districts (55)

ns = total number of farms required for the study (determined based on logistical feasibility and study objectives) (11)

Farms were then selected randomly within each district, ensuring proportional representation based on production capacity and system type.

Five (5) and six (6) fish farms were selected in Siavonga and Kafue districts, respectively.

Stage 2: Collection of Fish Samples

Once the farms were selected, the second stage involved collecting fish samples from each farm. The number of fish sampled per farm was determined using Cochran’s formula to ensure an adequate sample size:

where:

n=sample size,

Z is the Z statistic for a level of confidence (95%) = 1.96

P is the expected prevalence = 8.4% (Siamujompa et al., 2023)

d is the precision =0.05

The sample size (n) was estimated at 118.

2.4. Sample Collection

Apparently, healthy Nile tilapia, a key aquaculture species in the study areas, were sampled from various farms for bacterial isolation and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Target bacteria included Vibrio spp., Lactococcus garvieae, Streptococcus spp., Aeromonas spp., Escherichia coli, and Salmonella spp.—organisms relevant to fish health and food safety concerns.

Fish were humanely euthanised using clove oil at 100–200 mg/L, dissolved in ethanol for proper mixing, following ethical guidelines. Secondary confirmation methods, such as decapitation or brain destruction, were applied. Bacteriological swabs from the liver and cloaca were aseptically collected to maintain sample sterility and accuracy. At the farm, these bacteriological swabs were directly inoculated onto Blood agar (HiMedia, India) for broad bacterial growth and MacConkey agar (HiMedia, India) for selective differentiation of Gram-negative bacteria. Additionally, 1g of liver and cloaca tissue was placed in 9ml of alkaline peptone water(APW) (3% NaCl and pH 8) (HiMedia, India) for enrichment and incubated for 24 hours.

Agar plates were stored in cooler boxes to maintain sample viability during transportation to the laboratory, ensuring integrity for further analysis.

After collection of samples for bacteria isolation, the same fish specimen were stored in cooler boxes maintained at 0ºC to be transported to the laboratory for antimicrobial residue testing.

2.5. Isolation and Idenfication of Bacterial

Bacteria isolation involved incubating media plates (Blood and MacConkey agar) at 24–28°C for 24 hours upon arrival at the University of Zambia, School of Veterinary Medicine, Bacteriology Laboratory.

A loopfuls from each previous cultured APW tube (liver and cloacal tissue) were innoculated on Thiosulfate-citrate-bile salts-sucrose (TCBS) agar (HiMedia, India) at 24–28°C for 24 hours. To purify the Vibrio suspect colonies, a single green and yellow colonies from each grown type was streaked onto the other TCBS agar plates and incubated overnight at 24–28°C. This procedure was repeated until pure consistent colonies were obtained. Identification was accomplished based on the results of microscopic observation of stained smears using Gram staining and biochemical examination were carried by using: Indole test, Citrate utilization test, Triple sugar iron test and Salt tolerance test to detect growth of Vibrio species on 0%, 3% and 6% NaCl (Huq et al., 2012).

The isolation and identification of Aeromonas spp., Escherichia coli, and Salmonella spp. were preceded by inspecting and selecting colonies on previously inoculated MacConkey agar to facilitate differentiation based on lactose fermentation. The selected isolates were subcultured on MacConkey agar at 24–28°C for 24 hours. Following incubation, colony morphology was recorded, and suspected isolates were subjected to Gram staining for preliminary characterization. Biochemical identification was conducted using oxidase, triple sugar iron (TSI), citrate, and urease tests (Mumbo et al., 2023).

Isolation of Streptococcus spp. and L. garvieae. was performed by selecting suspect colonoes from previously inoculated Blood agar, which were subcultured on the same media and incubated at 24–28°C for 24–48 hours under facultative anaerobic conditions. Colony morphology and hemolytic patterns were recorded to differentiate species. Suspected isolates were subjected to Gram staining, catalase testing, and biochemical assays. Sugar fermentation tests, including lactose, mannitol, and trehalose utilization, were performed to further characterize isolates (Bwalya et al., 2020).

The confirmed isolates of Vibrio spp, Aeromonas spp., L. garvieae., Streptococcus spp., Salmonella spp., and Escherichia coli were stored in glycerol (Tryptone Soya Broth with 50% glycerol at −40 °C) for further antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

2.6. Determination of Antibiotic Susceptibility of Selected Bacteria

Antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) was performed using the disk diffusion method to assess bacterial resistance against antibiotics. Mueller-Hinton agar (HiMedia, India) was inoculated with bacterial suspensions sstandardised to McFarland 0.5 and incubated at 35–37°C for 16–18 hours. Zones of inhibition around antibiotic disks were measured to determine susceptibility/resistance. Target bacteria included Vibrio spp., L. garvieae, and E. coli, tested against specific antimicrobial panels. Antibiotics used included mpicillin (10 µg), Erythromycin (15 µg), Sulfamethoxazole (25 µg), Florfenicol (30 µg), Tetracycline (30 µg), Ceftazidime (30 µg), Ciprofloxacin (5 µg), Gentamicin (10 µg), Meropenem (10 µg), Imipenem (10 µg), Chloramphenicol (30 µg), Co-trimoxazole (25 µg), Amoxicillin-Clavulanic acid (20/10 µg), and Cefoxitin (30 µg).

2.7. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Residues in Fish Muscle

High-purity antibiotic standards (≥98%) for Sulfamethoxazole, Trimethoprim, Penicillin G, Ampicillin, Tetracycline, Oxytetracycline, Gentamicin, Tiamulin, Erythromycin and Tylosin were procured from Sigma-Aldrich (Germany), along with isotopically labeled internal standards for accurate quantification. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)-grade solvents were sourced from Merck (Germany), and ultrapure water was generated using a Pure Lab Ultra system (UK). Stock solutions (1 mg/mL) were prepared in methanol and stored at -20°C. Working standards (0.5–200 µg/L) were freshly prepared for calibration before each analytical batch.

2.7.1. Fish Sample Collection and Processing

All the fish samples collected from fish farms were analysed. Fish muscle (0.5 g) was homogenized and extracted using ethyl acetate, with EDTA as a chelating agent to prevent interference with fluoroquinolone detection. Extraction involved vortexing, sonication, and centrifugation, followed by solid-phase extraction (SPE) for purification using Oasis HLB cartridges (Waters, USA). The final extracts were dissolved in 500 µL of mobile phase, filtered (0.2 µm nylon filter), and analyzed via UHPLC-MS/MS.

2.7.2. UHPLC-MS/MS Analysis and Method Validation

Samples were analyzed using a Shimadzu Nexera X2 UPLC system with a Hypersil Gold C18 column (30 mm, 1.9 µm) under gradient elution (ethanol and 0.1% formic acid in water) at 500 µL/min flow rate. The UPLC system was coupled to a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Shimadzu 8050), operated in positive ionization mode using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) for precise quantification. Calibration curves (0.5–200 µg/L) were established using matrix-matched calibration, with internal standards for accuracy. Method validation included linearity (R² > 0.99), recovery (1, 10, 100 µg/kg), intra-/inter-day precision (RSD <15%), and limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) based on ICH guidelines.

This validated analytical method ensured high sensitivity, accuracy, and reproducibility for detecting antibiotic residues in fish, supporting reliable residue monitoring and food safety assessments.

2.8. Data Analysis

The data were managed using Microsoft Excel 2013 and analyzed with Datatab software . Descriptive statistics (mean, and percentage distributions) were used to assess bacterial isolation frequencies and antibiotic resistance prevalence in fish samples. Multi-drug resistance (MDR) profiles were analyzed, and statistical tests (e.g., chi-square, Fisher’s exact) were applied to evaluate significant differences across farms and regions, ensuring a comprehensive assessment of resistance patterns.

3. Results

A total of 118 fish samples were collected from 11 farms in Siavonga and Kafue districts, covering small-, medium-, and large-scale operations [Table 1]. Large-scale farms contributed 40 samples (15 from Kafue, 25 from Siavonga), medium-scale farms also provided 40 samples (20 from each district), and small-scale farms accounted for 38 samples (20 from Kafue, 18 from Siavonga). Siavonga contributed slightly more samples (63) than Kafue (55), ensuring balanced representation across both districts and production scales [

Table 2].

3.1. Prevalence of Bacteria

The prevalence of bacterial pathogens varied across production systems and scales of commercial fish farming.

E. coli was more prevalent in cage culture systems, with large-scale farms showing 5.08%, medium-scale farms 4.24%, and small-scale farms 0.85%.

Salmonella spp showed the highest prevalence in large-scale cage culture at 10.17%, while medium- and small-scale farms recorded higher prevalence in pond culture.

Aeromonas spp. was detected only in cage culture, with medium-scale farms showing the highest prevalence (2.54%).

Vibrio spp. prevalence was consistently higher in pond culture, peaking at 16.95% in medium-scale farms, while cage culture had lower rates.

L. garvieae prevalence varied, with large-scale pond culture showing the highest rate (10.17%) and medium-scale cage culture recording higher prevalence than ponds.

Streptococcus spp. was exclusive to pond culture, with medium-scale farms having the highest prevalence (2.54%). These results highlight the influence of production systems, farm scales, and management practices on the distribution of bacterial pathogens [

Table 2].

3.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility Test

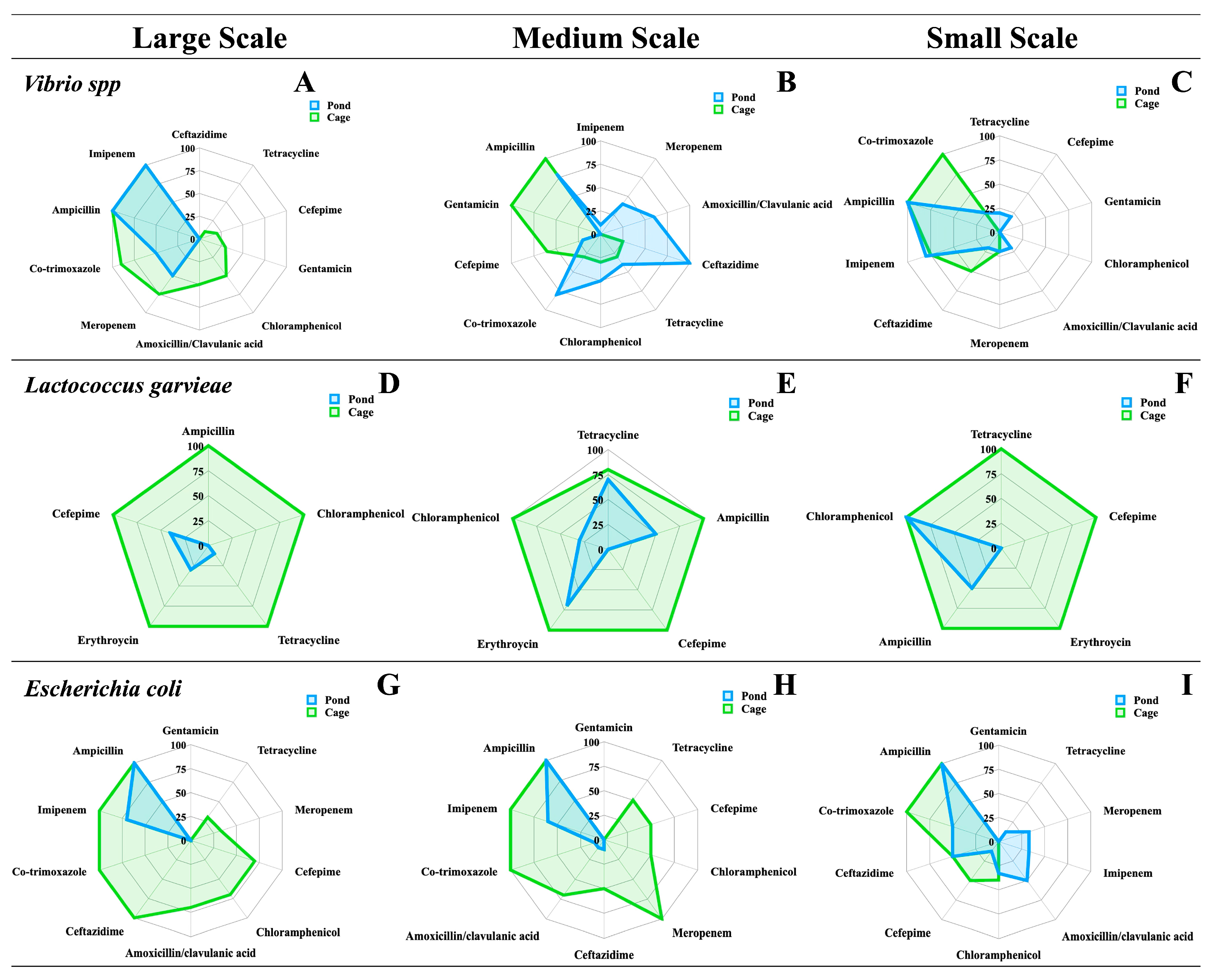

The antibiotic resistance profiles of Vibrio spp., L. garvieae, and E. coli exhibited notable variations across production scales (large, medium, and small) and culture systems (pond and cage).

For Vibrio spp., antibiotic resistance was consistently higher in pond culture compared to cage culture across all scales. In large-scale systems, pond culture demonstrated significant resistance to imipenem and ampicillin, while cage culture exhibited higher susceptibility, particularly to tetracycline and cefepime (70%). In medium-scale systems, ceftazidime and ampicillin showed 100% resistance in pond culture, while gentamicin displayed complete resistance in cage culture. In small-scale systems, pond culture exhibited elevated resistance to ampicillin and imipenem, while cage culture showed resistance to ampicillin and co-trimoxazole (100%) and imipenem (75%).

For L. garvieae, resistance was uniformly high in cage culture, with 100% resistance recorded across all antibiotics and production scales. In pond culture, resistance patterns varied; large-scale systems showed limited susceptibility to cefepime (40%) and ampicillin (30%). In medium-scale systems, pond culture demonstrated moderate susceptibility to chloramphenicol (70%) and ampicillin (50%). In small-scale systems, high resistance was observed across both culture systems, with cefepime and erythromycin exhibiting 100% resistance, while pond culture displayed moderate susceptibility to ampicillin (50%).

For E. coli, resistance was widespread across all antibiotics and production scales, with only slight variations. In large-scale systems, pond culture exhibited partial susceptibility to meropenem (70%) and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (50%), while resistance to ampicillin reached 100%. Medium-scale systems demonstrated pervasive resistance, with minor susceptibility to tetracycline, co-trimoxazole, and chloramphenicol in pond culture. Cage culture displayed slightly lower resistance, with moderate susceptibility to meropenem and imipenem. In small-scale systems, resistance was consistently high across both culture systems, with intermediate susceptibility observed for meropenem, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline (25%-33%) and complete resistance to ampicillin.

Figure 2.

Antibiotic Resistance Profiles of Vibrio spp., (Large(A), Medium(B), and Small (C))Lactococcus garvieae, (Large (D), Medium (E), and Small (F)) and Escherichia coli (Large(G), Medium(H), and Small (I)) Across Culture Systems (Pond and Cage).

Figure 2.

Antibiotic Resistance Profiles of Vibrio spp., (Large(A), Medium(B), and Small (C))Lactococcus garvieae, (Large (D), Medium (E), and Small (F)) and Escherichia coli (Large(G), Medium(H), and Small (I)) Across Culture Systems (Pond and Cage).

3.3. Antibiotic Residue Detection

The results of antibiotic residue testing in fish muscle samples from pond and cage culture systems across large-, medium-, and small-scale commercial farms revealed minimal detection of antibiotic residues. In pond culture systems, no antibiotic residues were detected for any of the tested antibiotics, including sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, penicillin G, ampicillin, tetracycline, oxytetracycline, gentamycin, tiamulin, erythromycin, and tylosin, across all production scales [

Table 6]. Similarly, in cage culture systems, no residues were detected in large- and medium-scale farms. However, a single positive result for pencillin G was observed in small-scale cage culture farms, indicating the presence of antibiotic residue in fish muscle from this system

4. Discussion

This study provides critical insights into the microbial composition, antibiotic susceptibility profiles, and antimicrobial residue detection in market-ready Nile tilapia from key aquaculture production regions in Zambia. The study identified the presence of E. coli, Salmonella spp., Aeromonas spp., and L. garvieae in sampled fish, with significant variations in pathogen prevalence across different aquaculture systems. Bacterial prevalence were notably higher in cage culture systems compared to pond-based systems, likely due to increased stocking densities, lower dissolved oxygen levels, and organic waste accumulation—factors that promote bacterial proliferation. Similar trends have been reported in Chilean salmon aquaculture, where intensive farming practices facilitate pathogen transmission and elevate disease incidence (Miranda, Godoy and Lee, 2018).

The prevalence of bacterial pathogens varied across different aquaculture systems and farm scales, indicating the role of environmental and management factors in microbial distribution. E. coli was predominantly found in large-scale cage culture systems, whereas Salmonella spp. had a higher prevalence in both large-scale cage and medium-scale pond cultures. A study in Malaysia found E. coli in fish and pond water across tilapia and Asian seabass farms using earthen ponds and floating cages, while Salmonella spp. were detected at lower rates with no clear association to production scale (Dewi et al., 2022a). Furthermore, the detection of Aeromonas spp. exclusively in cage systems suggests that the high organic matter accumulation and reduced water exchange in these environments favor its proliferation. This finding aligns with studies from Malaysian and Nigerian aquaculture systems, where earthen ponds reported low prevalence of bacteria as they benefited from natural filtration processes and reduced microbial stress (Alhaji, Maikai and Kwaga, 2021; Dewi et al., 2022b). However, in the present study, Vibrio spp. was more prevalent in pond culture systems, particularly in medium-scale farms, likely due to stagnant water conditions and higher nutrient loads. The persistence of zoonotic pathogens like E. coli and Salmonella spp. in aquaculture systems remains a concern, particularly when linked to agricultural runoff, untreated sewage, and interactions with wildlife (Schar et al., 2020; Narbonne et al., 2021).

Interestingly, L. garvieae exhibited a higher prevalence in pond culture systems, with the highest detection rates observed in large-scale farms. However, there are no documented cases of Lactococcus infections among pond culture farmers compared to those in cage culture, which may be attributed to the higher stocking densities and elevated water temperatures commonly observed in cage culture systems (Ndashe et al., 2023; Siamujompa et al., 2023).

The antibiotic susceptibility results revealed widespread resistance across various bacterial isolates, with distinct patterns between cage and pond culture systems. High levels of AMR were observed against imipenem, ampicillin, co-trimoxazole, cefepime, erythromycin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline across all production systems and scales. Vibrio spp. demonstrated higher resistance levels in pond culture systems, particularly against imipenem and ampicillin in large-scale farms, while cage culture isolates exhibited higher susceptibility to tetracycline and cefepime. A study by Haifa-Haryani et al. (2022) investigated antibiotic resistance in Vibrio spp isolated from cultured shrimp in Peninsular Malaysia, revealing that all Vibrio isolates were resistant to ampicillin, with varying resistance levels to other antibiotics, and although focused on shrimp aquaculture, it highlights the prevalence of ampicillin resistance among Vibrio spp in intensive farming systems (Haifa-Haryani et al., 2022).

In the present study, L. garvieae exhibited complete resistance across all antibiotics in cage culture systems. In pond culture, however, moderate susceptibility to chloramphenicol and ampicillin was observed, indicating some level of antibiotic effectiveness remains. Similar results were reported in studies by Sezgin et al. (2023) and Xu et al. (2024) investigated L. garvieae in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in Turkey and cultured pufferfish (Takifugu obscurus) in China, respectively, revealing resistance to multiple antibiotics such as erythromycin, tetracycline, kanamycin, gentamicin, and ciprofloxacin, while both studies found susceptibility to chloramphenicol and ampicillin, highlighting variations in resistance profiles across different strains (Sezgin et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2024).

In the present study, E. coli exhibited 100% resistance to ampicillin across all farm scales and production systems, with partial susceptibility to meropenem and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid in large-scale pond culture. These findings are consistent with those of Alua et al., (2021), who investigated antimicrobial resistance profiles of E. coli isolates from fish in Abuja, Nigeria, and found that 100% of the isolates were resistant to ampicilin, and erythromycin, exhibiting varying susceptibility to other antibiotics, including amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (Alua et al., 2021). This resistance pattern is concerning, as E. coli is a key indicator of fecal contamination and antimicrobial resistance in aquaculture environments.

The antibiotic residue analysis revealed minimal detection in fish muscle samples, with no residues identified in pond culture systems or most cage culture farms. However, a single detection of pencillin residue in small-scale cage culture raises concerns about indirect exposure pathways. Similar observations were made in Danish and Chilean aquaculture, where residual antibiotics persisted in sediments and water due to feed contamination and effluent discharge (Schmidt et al., 2000; Miranda, Godoy and Lee, 2018). The non-detection of antibiotic residues in fish muscle may support the claim that Zambian farmers do not directly medicate their fish (Ndashe et al., 2023).To achieve minimal to zero antibiotic use in Zambia, strengthening regulatory frameworks and promoting best practices in antibiotic stewardship will be essential to mitigate risks and ensure the safety of farmed fish for consumers.

The detection of antimicrobial-resistant bacterial isolates alongside low levels of antimicrobial residues in fish in the present study raises concerns regarding the sources of resistant bacteria in aquaculture production systems within the study area. A study of AMR trends in aquaculture and fisheries in Asia reported a 33% level of resistance over two decades among cultured aquatic animals, suggesting that while antibiotic residues might be low, resistant bacteria can persist due to factors such as environmental contamination or horizontal gene transfer (Schar et al., 2021).

Potential contamination sources in aquaculture systems are diverse and complex, reflecting the multifaceted nature of antibiotic introduction into these environments. A major contributor is water sources, particularly those shared with agricultural or urban activities. These water bodies often accumulate antibiotic residues through runoff from agricultural fields treated with antimicrobials or via the discharge of untreated wastewater from urban setting or human settlements, creating an environment conducive to the persistence and spread of resistant bacteria (Schar et al., 2020; Alhaji, Maikai and Kwaga, 2021). In such cases, shared water bodies often become critical reservoirs for resistant bacteria, acting as conduits for the introduction and spread of antibiotic residues and resistant genes into aquaculture environments (Milijasevic et al., 2024).

The complexity of these external contamination pathways underscores the challenges of managing antibiotic resistance in aquaculture systems. For instance, the interconnected nature of water bodies allows contaminants to spread widely, impacting multiple aquaculture facilities and even communities that rely on these water sources (Brunton et al., 2019). This is exacerbated by the limited capacity for effective wastewater treatment in many low- and middle-income countries, where effluents are often discharged directly into natural water bodies without adequate processing (Wang et al., 2022). Consequently, aquaculture operations in such regions are particularly vulnerable to the infiltration of resistant bacteria and antibiotic residues, even when farmers do not use antibiotics directly (Brunton et al., 2019). Therefore, understanding these contamination pathways is essential for developing targeted mitigation strategies and ensuring the sustainability of aquaculture practices in Zambia.

The findings of this study highlight the critical need for enhanced biosecurity measures, continuous monitoring of water quality, and stringent surveillance of antimicrobial residues in Zambia’s aquaculture industry. The high prevalence of bacterial pathogens, particularly in cage culture systems, highlights the importance of water quality management, stocking density control, and regular health assessments to mitigate disease outbreaks.

Moreover, the observed antibiotic resistance patterns call for the implementation of alternative disease management strategies, such as probiotics, vaccines, and improved husbandry practices. Integrating antimicrobial resistance surveillance into routine aquaculture monitoring programs can provide valuable data for guiding policy decisions and promoting sustainable fish farming practices.

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrates significant variability in bacterial prevalence and antibiotic resistance across production scales and culture systems in high aquaculture production regions in Zambia. Antibiotic resistance was more pronounced in both cage and pond systems, with 100% resistance to ampicillin in E.coli across all scales. Minimal antibiotic residues were detected, except for a single penicillin detection in small-scale cage systems.

Author Contributions

KN conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated sample collection, performed data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. GM contributed to the study design, facilitated fieldwork, and assisted with manuscript writing. CC, MS1, GN, HK, LM, and EK handled field data collection and sample processing. KN, GM, CM, and MC provided technical support and contributed to result interpretation. CM assisted with data management and coordination. KC, NMM, MMS and TK provided input and reviewed the manuscript, while JBM assisted with statistical analysis. BMH supervised the study and reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the fish farmers in the study areas for their cooperation and support in permitting our team to collect samples from their fish farms, which was crucial for the successful completion of this research. We also extend our heartfelt appreciation to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Zambia for their financial and logistical support. Additionally, we are grateful for the facilitation provided by the Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock through the Department of Fisheries and the Department of Veterinary Services, whose assistance was essential in ensuring the smooth execution of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest associated with this study.

References

- Alhaji, N.B., Maikai, B.V. and Kwaga, J.K., 2021. Antimicrobial use, residue and resistance dissemination in freshwater fish farms of north-central Nigeria: One health implications. Food Control, 130, p.108238. [CrossRef]

- Alua, A.J., Omeizaa, G.K., Amehb, J.A. and SI, E., 2021. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance profile of Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli O157 (STEC) from retailed miscellaneous meat and fish types in Abuja, Nigeria. Veterinary Medicine and Public Health Journal, 2(2), pp.37-43. [CrossRef]

- Brunton, L.A., Desbois, A.P., Garza, M., Wieland, B., Mohan, C.V., Häsler, B., Tam, C.C., Le, P.N.T., Phuong, N.T., Van, P.T. and Nguyen-Viet, H., 2019. Identifying hotspots for antibiotic resistance emergence and selection, and elucidating pathways to human exposure: Application of a systems-thinking approach to aquaculture systems. Science of the total environment, 687, pp.1344-1356. [CrossRef]

- Bwalya, P., Simukoko, C., Hang'ombe, B.M., Støre, S.C., Støre, P., Gamil, A.A., Evensen, Ø. and Mutoloki, S., 2020. Characterization of streptococcus-like bacteria from diseased Oreochromis niloticus farmed on Lake Kariba in Zambia. Aquaculture, 523, p.735185. [CrossRef]

- Chatreman, N., Seecharran, D. and Ansari, A.A., 2020. Prevalence and distribution of pathogenic bacteria found in fish and fishery products: A review. Journal of Fisheries and Life Sciences, 5(2), pp.53-65.

- Dewi, R.R., Hassan, L., Daud, H.M., Matori, M.F., Zakaria, Z., Ahmad, N.I., Aziz, S.A. and Jajere, S.M., 2022. On-Farm Practices Associated with Multi-Drug-Resistant Escherichia coli and Vibrio parahaemolyticus Derived from Cultured Fish. Microorganisms, 10(8), p.1520. [CrossRef]

- Dewi, R.R., Hassan, L., Daud, H.M., Matori, M.F., Nordin, F., Ahmad, N.I. and Zakaria, Z., 2022. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli, Salmonella and Vibrio derived from farm-raised Red Hybrid Tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) and Asian Sea Bass (Lates calcarifer, Bloch 1970) on the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia. Antibiotics, 11(2), p.136. [CrossRef]

- Haifa-Haryani, W.O., Amatul-Samahah, M.A., Azzam-Sayuti, M., Chin, Y.K., Zamri-Saad, M., Natrah, I., Amal, M.N.A., Satyantini, W.H. and Ina-Salwany, M.Y., 2022. Prevalence, antibiotics resistance and plasmid profiling of Vibrio spp. isolated from cultured shrimp in Peninsular Malaysia. Microorganisms, 10(9), p.1851. [CrossRef]

- Hasimuna, O.J., Maulu, S., Nawanzi, K., Lundu, B., Mphande, J., Phiri, C.J., Kikamba, E., Siankwilimba, E., Siavwapa, S. and Chibesa, M., 2023. Integrated agriculture-aquaculture as an alternative to improving small-scale fish production in Zambia. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 7, p.1161121. [CrossRef]

- Huq, A., Haley, B.J., Taviani, E., Chen, A., Hasan, N.A. and Colwell, R.R., 2012. Detection, isolation, and identification of Vibrio cholerae from the environment. Current protocols in microbiology, 26(1), pp.6A-5. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M., Ahmad, F., Yaqub, B., Ramzan, A., Imran, A., Afzaal, M., Mirza, S.A., Mazhar, I., Younus, M., Akram, Q. and Taseer, M.S.A., 2020. Current trends of antimicrobials used in food animals and aquaculture. In Antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance genes in the environment (pp. 39-69). Elsevier . [CrossRef]

- Ljubojević Pelić, D., Radosavljević, V., Pelić, M., Živkov Baloš, M., Puvača, N., Jug-Dujaković, J. and Gavrilović, A., 2024. Antibiotic Residues in Cultured Fish: Implications for Food Safety and Regulatory Concerns. Fishes, 9, p.484. [CrossRef]

- Milijasevic, M., Veskovic-Moracanin, S., Milijasevic, J.B., Petrovic, J. and Nastasijevic, I., 2024. Antimicrobial Resistance in Aquaculture: Risk Mitigation within the One Health Context. Foods, 13(15), p.2448. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, C.D., Godoy, F.A. and Lee, M.R., 2018. Current status of the use of antibiotics and the antimicrobial resistance in the Chilean salmon farms. Frontiers in microbiology, 9, p.1284.. [CrossRef]

- Mumbo, M.T., Nyaboga, E.N., Kinyua, J.K., Muge, E.K., Mathenge, S.G., Rotich, H., Muriira, G., Njiraini, B. and Njiru, J.M., 2023. Antimicrobial resistance profiles of Salmonella spp. and Escherichia coli isolated from fresh Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fish marketed for human consumption. BMC microbiology, 23(1), p.306. [CrossRef]

- Narbonne, J.A., Radke, B.R., Price, D., Hanington, P.C., Babujee, A. and Otto, S.J., 2021. Antimicrobial use surveillance indicators for finfish aquaculture production: a review. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8, p.595152. [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R., Fang, S. and Fanzo, J., 2023. A global view of aquaculture policy. Food Policy, 116, p.102422. [CrossRef]

- Ndashe, K., Hang’ombe, B.M., Changula, K., Yabe, J., Samutela, M.T., Songe, M.M., Kefi, A.S., Njobvu Chilufya, L. and Sukkel, M., 2023. An Assessment of the risk factors associated with disease outbreaks across tilapia farms in Central and Southern Zambia. Fishes, 8(1), p.49. [CrossRef]

- Pepi, M. and Focardi, S., 2021. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria in aquaculture and climate change: A challenge for health in the Mediterranean area. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(11), p.5723. [CrossRef]

- Schar, D., Klein, E.Y., Laxminarayan, R., Gilbert, M. and Van Boeckel, T.P., 2020. Global trends in antimicrobial use in aquaculture. Scientific reports, 10(1), p.21878. [CrossRef]

- Schar, D., Zhao, C., Wang, Y., Larsson, D.J., Gilbert, M. and Van Boeckel, T.P., 2021. Twenty-year trends in antimicrobial resistance from aquaculture and fisheries in Asia. Nature communications, 12(1), p.5384. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.S., Bruun, M.S., Dalsgaard, I., Pedersen, K. and Larsen, J.L., 2000. Occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in fish-pathogenic and environmental bacteria associated with four Danish rainbow trout farms. Applied and environmental microbiology, 66(11), pp.4908-4915. [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, S.S., Yılmaz, M., Arslan, T. and Kubilay, A., 2023. Current antibiotic sensitivity of Lactococcus garvieae in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) farms from Southwestern Turkey. Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 29(2), pp.630-642. [CrossRef]

- Siamujompa, M., Ndashe, K., Zulu, F.C., Chitala, C., Songe, M.M., Changula, K., Moonga, L., Kabwali, E.S., Reichley, S. and Hang’ombe, B.M., 2023. An investigation of bacterial pathogens associated with diseased Nile tilapia in small-scale cage culture farms on Lake Kariba, Siavonga, Zambia. Fishes, 8(9), p.452. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Mairinger, W., Raj, S.J., Yakubu, H., Siesel, C., Green, J., Durry, S., Joseph, G., Rahman, M., Amin, N. and Hassan, M.Z., 2022. Quantitative assessment of exposure to fecal contamination in urban environment across nine cities in low-income and lower-middle-income countries and a city in the United States. Science of The Total Environment, 806, p.151273. [CrossRef]

- Xu, R., He, Z., Deng, Y., Cen, Y., Mo, Z., Dan, X. and Li, Y., 2024. Lactococcus garvieae as a Novel Pathogen in Cultured Pufferfish (Takifugu obscurus) in China. Fishes, 9(10), p.406. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).