1. Introduction

Autonomous robotic grappling is the core requirement for on-orbit robotic servicing and assembly missions. [

1] National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) recently prototyped grappling arms for its Space Exploration Vehicle (SEV). [

2]

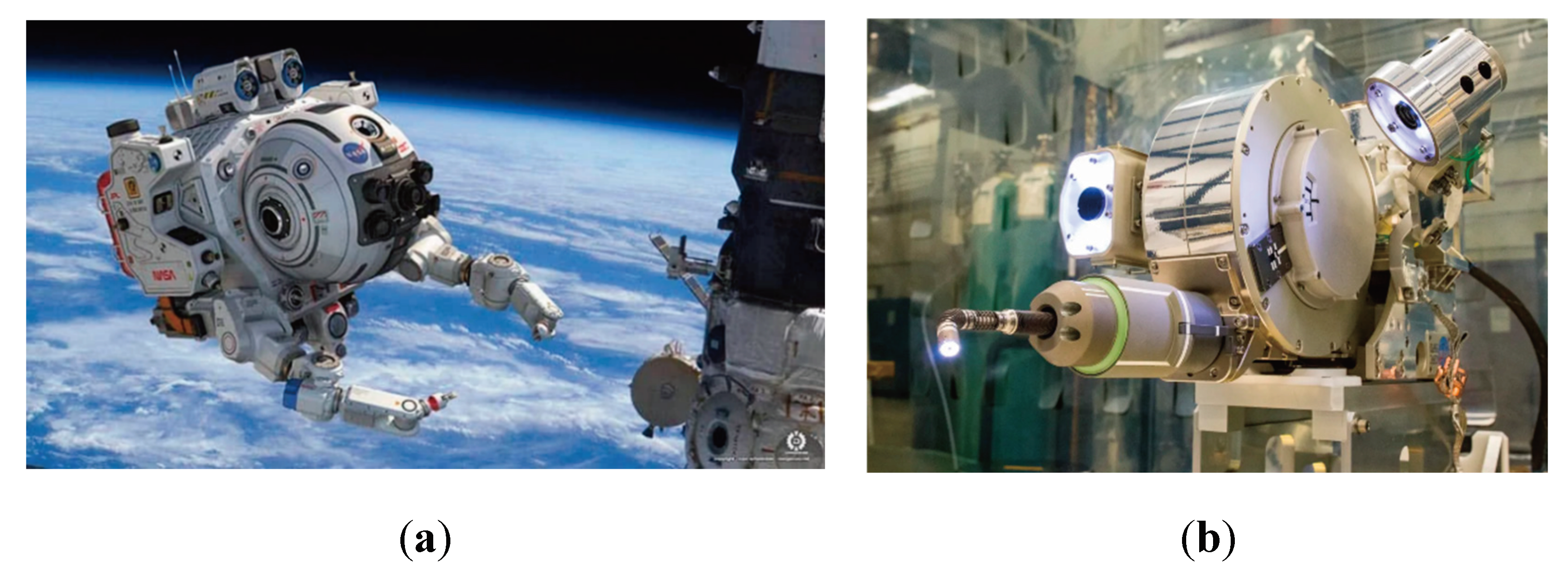

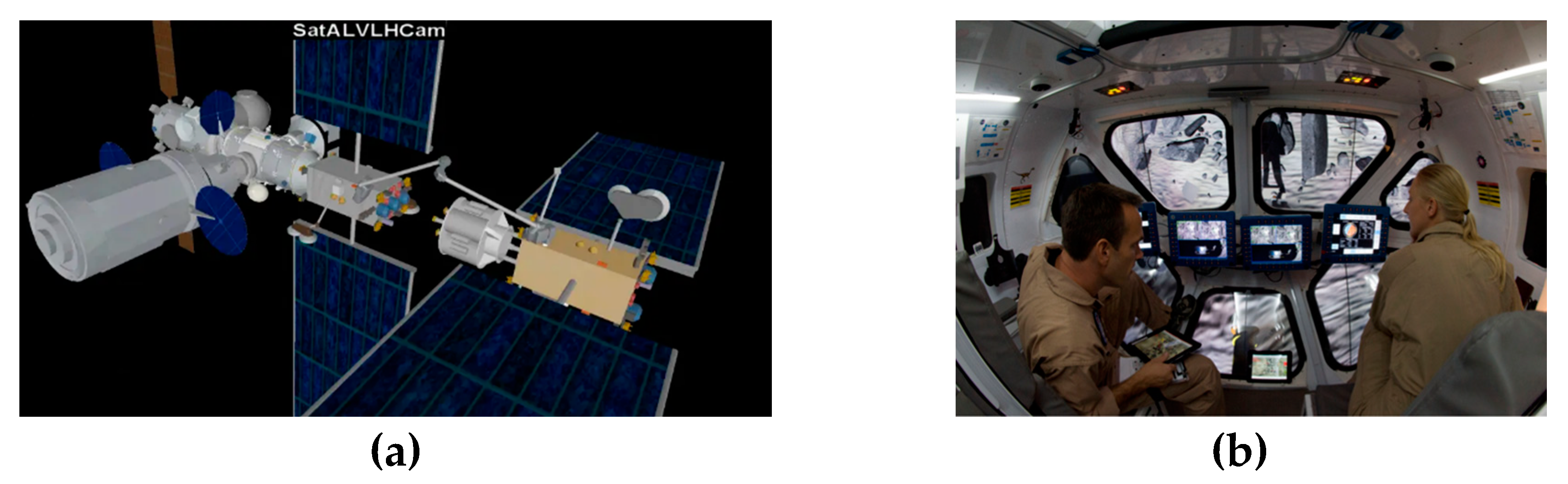

Figure 1.

(

a) NASA PickNik Robotics in-orbit robot addresses a common gap in deploying robotic arms into environments where full autonomy is still too difficult permitting a human operator to supervise and quickly intervene when the space robot gets stuck. [

3] (

b) Robotic Refueling Mission 3 (RRM3) technologies were developed store and transfer super-cold cryogenic fluids. [

4] Image credit: NASA. [

5] See ‘aside’ note in

Appendix A.

Figure 1.

(

a) NASA PickNik Robotics in-orbit robot addresses a common gap in deploying robotic arms into environments where full autonomy is still too difficult permitting a human operator to supervise and quickly intervene when the space robot gets stuck. [

3] (

b) Robotic Refueling Mission 3 (RRM3) technologies were developed store and transfer super-cold cryogenic fluids. [

4] Image credit: NASA. [

5] See ‘aside’ note in

Appendix A.

1.1. Review of the Literature

Long-term sustainability of space includes other robotics tasks like active debris removal, [

6] necessitating arms for grappling and various grasping and anchoring mechanisms. [

2] According to the Technical Committee for Space Robotics of the IEEE Robotics & Automation Society, priority areas for the technical committee include electromechanical design and control, and command & control (including teleoperated modes). [

7] The study in refence [

8] emphasizes center of mass changes due to deployment of payloads or instruments, solar panels, gravity booms, magnetometers, antennas, cameras, solar sails, etc. and used recursive least squares to estimate the mass center’s position. The study in [

9] misaligns a thruster from the anticipated center of mass and uses the governing dynamic equations of motion to estimation the mass center location using multiple Kalman filters.

Determination of moments of inertia (but not inertia products) about two axes was proposed in 1948 for airplane components prior to flight, where the component would be suspended in a lab and subjected to standard pendulum experiments. [

10] Similarly, the moments for the entire airplane were similarly treated in [

11]. Progress over the subsequent forty–six years added capabilities to use both angular acceleration methods and oscillation methods where the assumption is invoked that the suspension axis is assumed to be the axis of rotation. [

12] Inertia cross–products were still not available. Twenty–nine years later light detection and ranging was utilized to estimate inertia parameters within twenty–percent, while location of the mass center was not performed. [

13,

14] Just this year, principal moments (not inertia cross products) of space tethers were estimated using unscented Kalman filters. [

15]

Mass center estimation was recently proposed using a force platform with inertial sensors for balance evaluation in quiet standing and compared the results to traditional methods using optical motion capture system for truth values. [

16] Three general classifications of methods were listed as follows, while this manuscript presents a novel alternative:

Reference [

19] categorized the methods slightly differently as either sensors’ networks or a single sensor while proposing using magneto-inertial measurement units. Calculation of the mass center was proposed [

20,

21,

22] by electrostatic suspension of a proof mass in the satellite in an electrode cage which is rigidly attached to the spacecraft. Accelerations of the proof mass were determined, and then then relative accelerations between the spacecraft and proof mass were used to estimate the mass center. The procedure was used periodically to provide mass center location estimates. Follow–on experiments were presented in [

23]. Arguably, this proof mass–electrode cage may be considered a state of the art for spacecraft so equipped. The calculations involve estimation of angular velocities and quaternion fitting using regression. (ASIDE: the methods proposed in this paper instead involve estimation of all inertia components (moments and products) and uses those estimates to deterministically calculate mass center location).

CFD methods were used in [

24] to investigate the aerodynamic performance of the free-fall wing, and the results indicate wing fluttering and tumbling motions’ tumbling frequencies are driven by changing locations of the moments of inertia around the tumbling axis. Furthermore, the changing position of the center of mass complicates the free-fall motion. The study in reference [

25] used least squares, maximum likelihood, and Kalman filter estimators to estimate mass, center of mass, and moments of inertia of a multi–lift slung aircraft load. The study in reference [

26] used image processing to locate centers of mass using Python–based programming.

Regression–based learning may function as a projection operator to enable data-driven learning of the operators in the Mori–Zwanzig formalism, where [

27] proposed a principled method to extract the Markov and memory operators for any regression models. The research found that more expressive nonlinear regression models fill in the gap between the highly idealized and computationally efficient Mori’s projection operator and the most optimal yet computationally infeasible Zwanzig’s projection operator.

For certain applications, e.g. on-orbit debris inspection of orbital natural objects, defunct satellites, and debris, etc. estimating the mass center requires mapping from a moving observer. Reference [

28] applies an observer to estimate internal angular orientation, angular velocity, and angular acceleration. Next, pose-graph mapping is with visual odometry produces trajectory relative to a target-fixed frame.

Distinguished from these disparate approaches to autonomously estimate the mass center (while maintaining usage of observers), this present study seeks to determine time varying inertia identification and proposed novel online calculation of time varying location of the combined system’s center of mass using two norm optimal nonlinear, projection regression–based learning augmented with enhanced, nonlinear Luenberger observers in direct comparison to benchmark methods.

Box 1. Problem Statements, research objectives, and key contributions.

Problem statements: At all times, find a system’s mass distribution and the location of the center of mass. How may the location be calculated given only timed, angular position data? To what degree of accuracy can metrics be discerned? Requiring how much computational burden? Requiring how much effort?

Research objectives: 1) Using only attitude angle data, discern mass inertia imbalance and 2) express that imbalance as an offset center of gravity, and then discern the location of the center of mass.

Key contributions: Center of gravity location estimation convergence is improved over the state–of–the–art comparative benchmark [

21,

22,

23] from millimeter convergence over hundreds of days, to hundreds of millimeters in minutes achieved in this study.

1.2. State of the Art Benchmarks

The following list highlights the current state of the art inertia moment and products determination and locating the mass center:

In 2022, reference [

1] provided an overview survey of the algorithms and test and validation strategies for grappling robotic free-flying spacecraft, de–emphasizing spacecraft docking and berthing. Core technologies identified includes orientation control (including distributed control systems) and the ability to adapt to unexpected loads. Those core technologies motivate the developments presented in this present study.

Nonlinear dynamics are highlighted as key, and therefore nonlinear approaches are adopted.

Despite insistence on nonlinear dynamics, linear time invariant. PID control laws are emphasized to be “straightforward to design and relatively easy to tune and provide performance sufficient to meet most operating requirements”.

Since the dynamics are Hamiltonian, nonlinear adaptive control is also highlighted and is also adopted in this present study.

Trajectory planning is highlighted as well, and autonomous trajectory generation is adopted to permit nonlinear control proposals.

Air–bearing tables are highlighted to aid validation using laboratory experiments, and one such free–floating, highly flexible robotic gripper arm is described.

1.3. Novelties Presented

The following short list of novelties are combined sequentially to produce novel, autonomous, real–time space robotics:

Time varying estimates of mass locations are found with classical adaptive methods compared to optimal learning leveraging nonlinear, projection regression–based methods. Estimates are supported in–part by the novel use of nonlinear enhanced Luenberger observers.

Time varying estimates of mass locations are used to find time varying estimates of the location of the system center of mass. Estimates are supported in–part by the novel use of nonlinear enhanced Luenberger observers applying the fundamental relationships between products of inertia and mass center location.

Requirement to diagonalize the matrix of mass moments of inertia is eliminated.

Requirement to linearize the governing differential equations is eliminated.

Requirement to simplify governing equations (e.g. small angle assumption, etc.) is eliminated.

Analysis precedes modeling and simulation to verify the design, and then spaceflight experiments are proposed for the sequel to validate the simulation results.

1.4. Conveniences of Presentation

Periodic tables of proximal variables and nomenclature definitions is provided to aid reading without necessitating flipping back and forth between pages seeking definitions of terms. Observers are presented topologically rather than using state space equations to aid remembrance and understanding. Lastly, simulations used to produce the data presented in the manuscript are used to produce the graphic topologies, and furthermore MATLAB®/SIMULINK® subsystems are included in the article appendix aiding repeatability by the readership.

2. Materials and Methods

Physics–based dynamics are foremost detailed in section 2.1. Next, feedforward control using physics–based dynamic embodiment is presented in section 2.2. followed by feedback instantiations: both nonlinear adaption and projection regression–based learning of fully populated inertia matrix components. Nonlinear, enhanced Luenberger observers are introduced to support both feedback instantiations, and the observers are juxtaposed quantitatively to a comparative benchmark. Finally, location of the mass center is estimated using the estimated inertia components with the Final Value Theorem, which is briefly reviewed in the analysis of section 2.

Figure 2.

Process stages adopted in this study: analyze and hypothesize followed by verification of analysis with modeling and simulation validated experimentally.

Figure 2.

Process stages adopted in this study: analyze and hypothesize followed by verification of analysis with modeling and simulation validated experimentally.

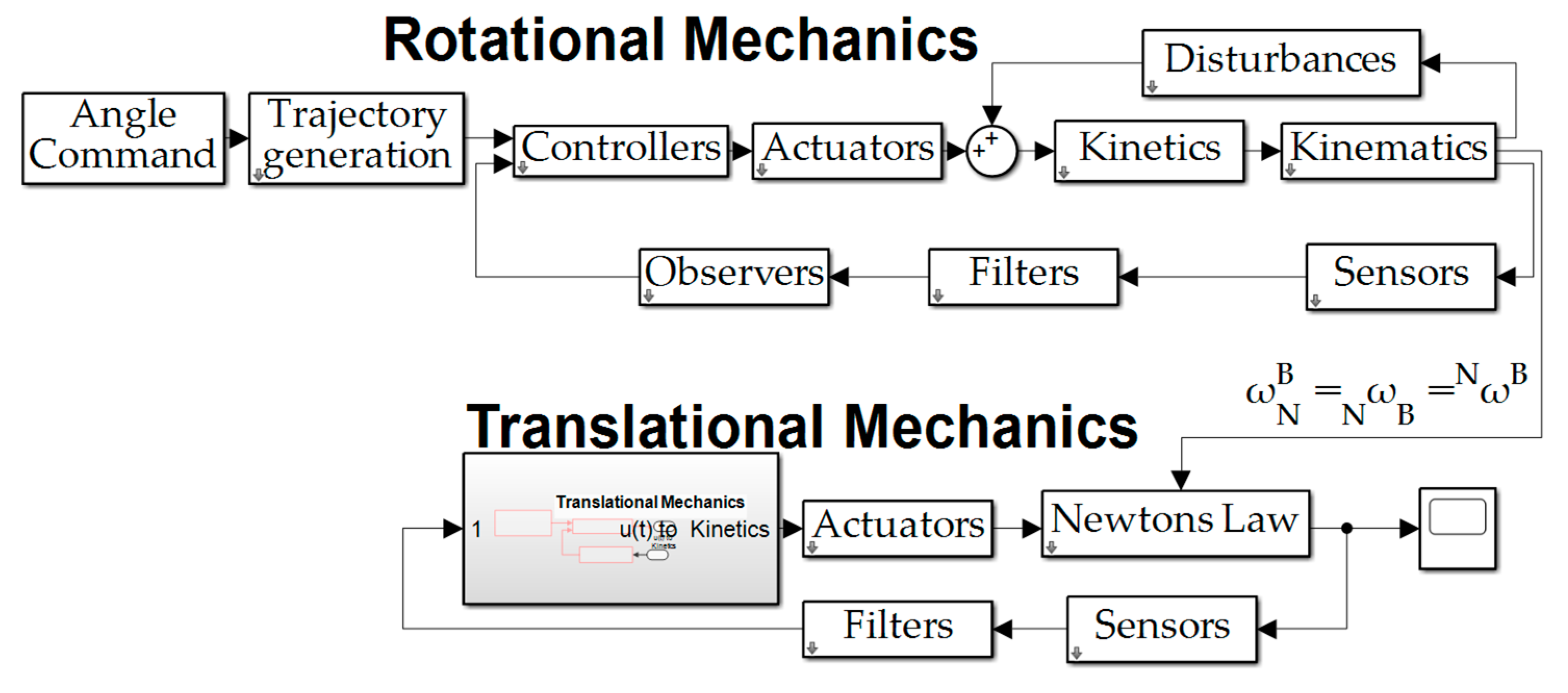

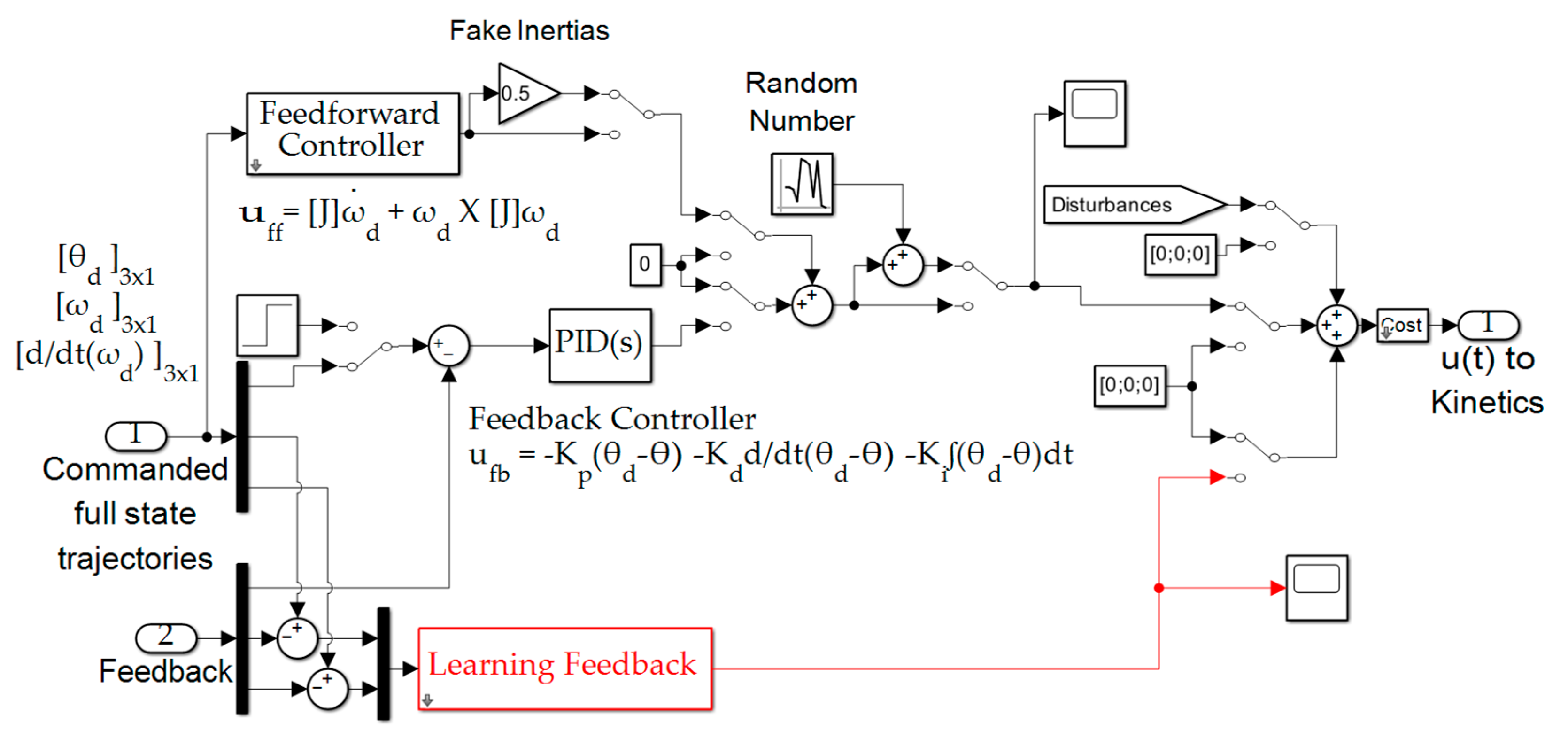

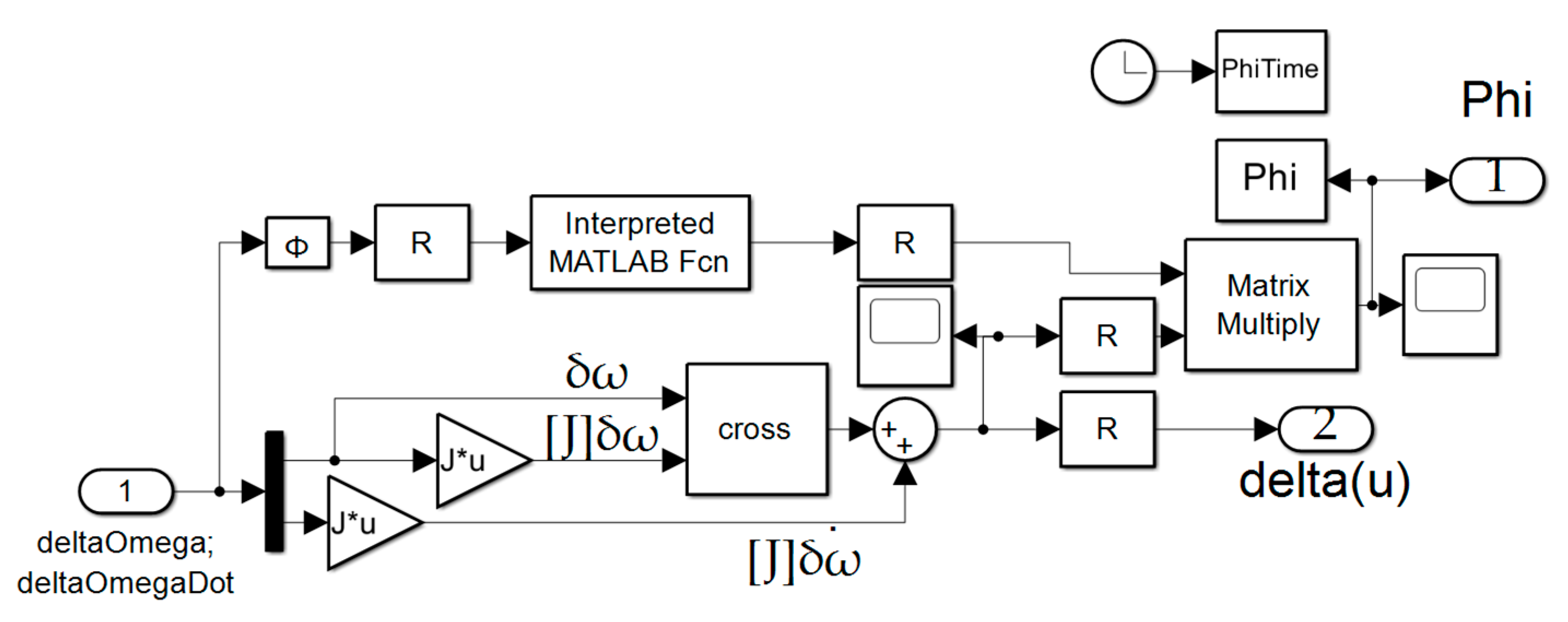

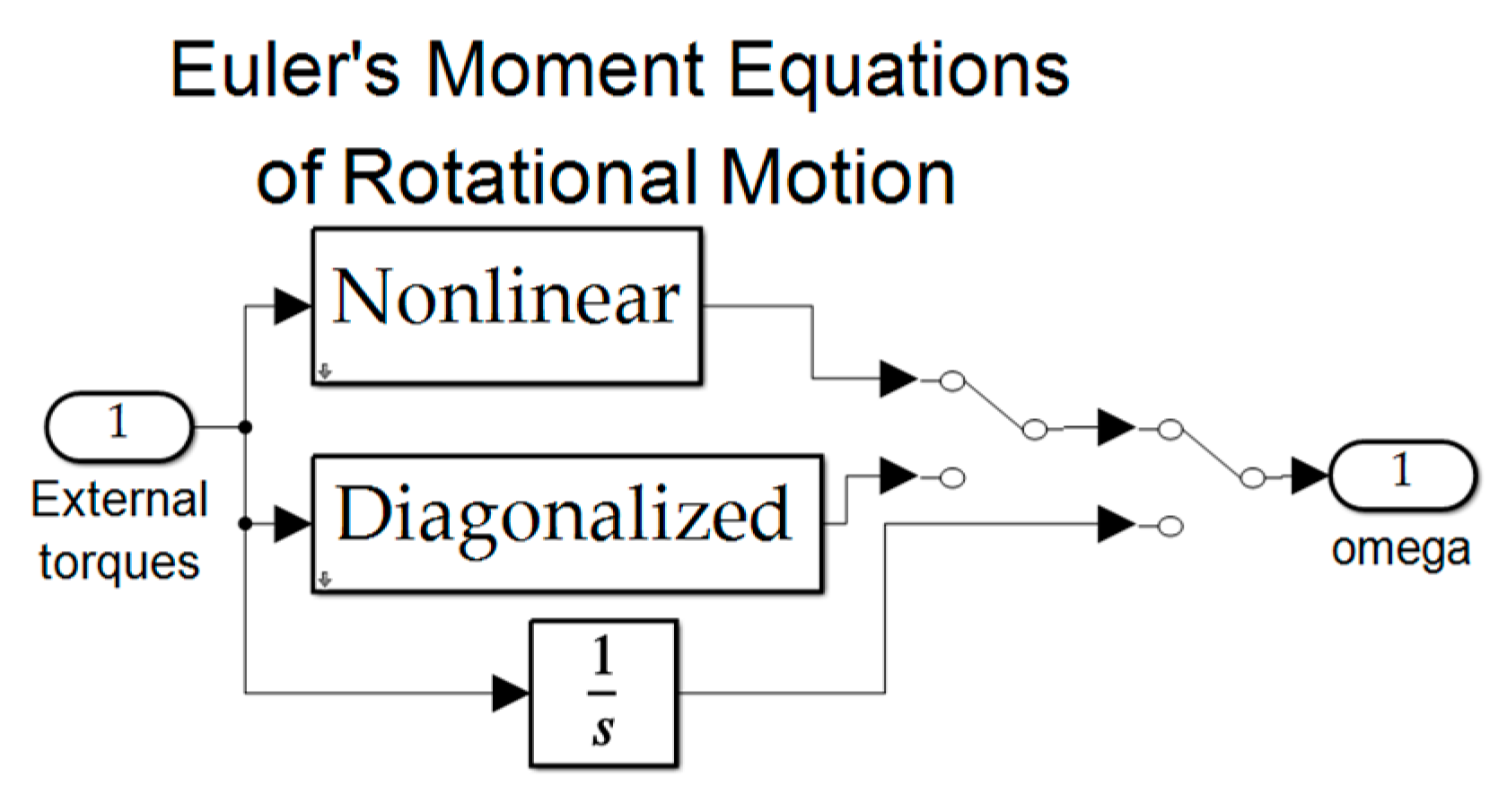

Figure 3.

Space robot system topology represented by the MATLAB

®/SIMULINK

® simulation used to produce the quantitative results presented in this manuscript. Internal content of simulation subsystems is depicted in

Appendix B. Notice the translational subsystems of the six–degree–of–freedom motion simulation are deactivated reducing superfluous computational burden.

Figure 3.

Space robot system topology represented by the MATLAB

®/SIMULINK

® simulation used to produce the quantitative results presented in this manuscript. Internal content of simulation subsystems is depicted in

Appendix B. Notice the translational subsystems of the six–degree–of–freedom motion simulation are deactivated reducing superfluous computational burden.

Foreshadowing the summarized methods,

Table 1 includes a pithy implementation procedure and lists the relevant sections the details may be found.

Table 1.

Implementation procedure.

Table 1.

Implementation procedure.

-

Use the physics–based governing dynamics to embody the control (section 2.1)

Do not diagonalize the inertia matrix Do not linearize the governing equations of motion Do not use small angle assumption to simplify the system equations Establish classical feedback control as comparative benchmark

Use nonlinear, enhanced Luenberger observers (section 2.4–2.6) to estimate all motion states and control. Use projection–based non–linear regression learning to learn the fully populated mass moments of inertia (masses and mass locations) including principal moments and off–diagonal products of inertia. (section 2.3) Use off–diagonal products of inertia to estimate location of the center of mass (section 2.8). |

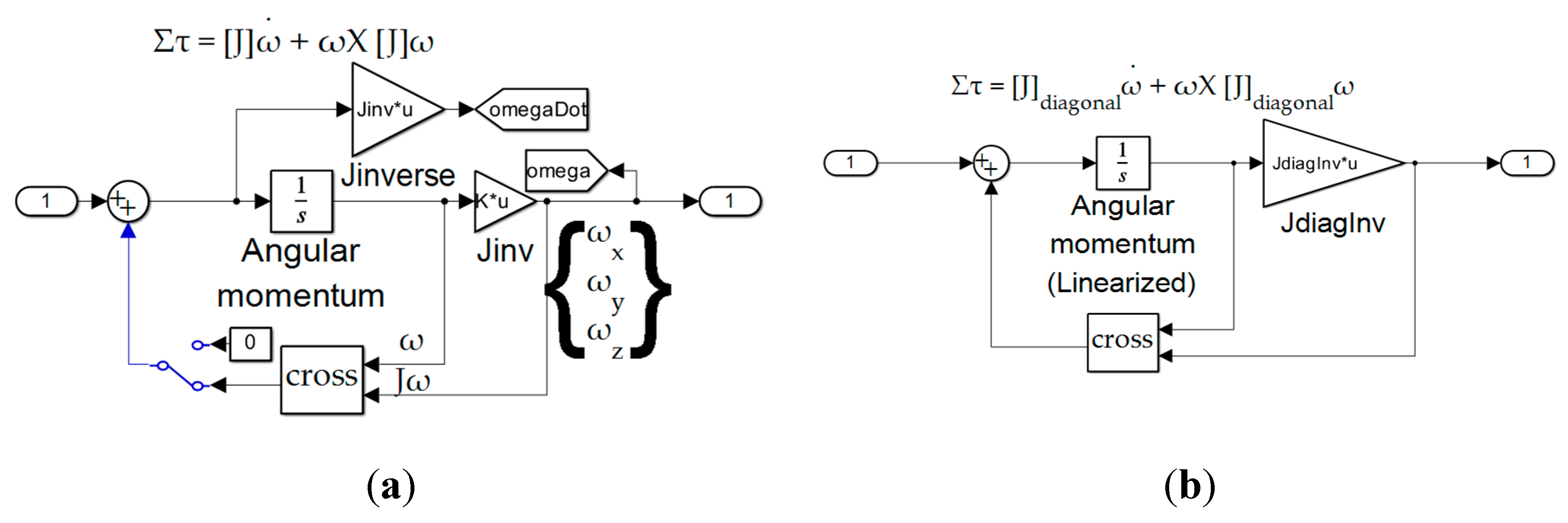

2.1. Physics–Based Dynamics

The well–known Euler’s moment equations (equation (1)) govern rotations of objects of mass. The system of equations is nonlinear and coupled (especially for a fully populated inertia matrix

with both moments and products of inertia, particularly noting the presence of the cross–product operation which puts terms from the second and third equation into the first equation in the system. The equations are ubiquitously linearized and simplified by changing the basis of measurement to diagonalize the inertia matrix.

One motivation for linearization is to aid expression of the system of equations in a standard regression form (a matrix of ‘knowns’ multiplied by a vector of presumed ‘unknowns’). Particularly stemming from a common practice to put the motion states into the vector of unknowns, often referred to as the “state vector”, attempts to express equation (1) into regression form in equation (2).

Table 2.

Table of proximal variables and nomenclature 1.

Table 2.

Table of proximal variables and nomenclature 1.

| Variable/ acronym |

Definition |

Variable/ acronym |

Definition |

|

Inertia matrix or tensor |

|

|

|

Angular acceleration |

|

inertia product |

|

Angular velocity |

|

inertia product |

|

–direction |

|

|

|

–direction |

|

inertia product |

|

–direction |

|

|

|

Regression matrix of knowns |

|

Unknown, predicted variables |

The inertia matrix

is most often diagonalized using the eigenvalue coordinate transformation, or spectral decomposition. The transformation begins with relationships expressed in coordinates of the body fixed axes (where the inertia matrix is fully populated with moments and products). Transformation to a new basis vector set (i.e., the eivenvectors) lead to a diagonalized inertia matrix with only moments and no products, and the diagonalized matrix simplifies subsequent mathematics that are performed with the inertia matrix. [

29]

A common engineering practice is to simply assume the eigenvector basis is equivalent to the body frame basis vectors, where the engineer is comfortable accepting the accompanying error of such an assumption.

The inertia matrix will not be diagonalized in this present study, instead favoring increased accuracy. The inability of expressing equation (2) in standard regression form must be re–addressed.

Noting the difficulties of equation (2), omitting the common practice establishing the vector of unknowns, the mass moments and products may instead be used (equation (3)). A more elaborate derivation from equation (1) to equation (3) is offered in appendix A.

Equation (3) establishes the physics–based embodiment of the control with specific instantiations in both feedforward and feedback.

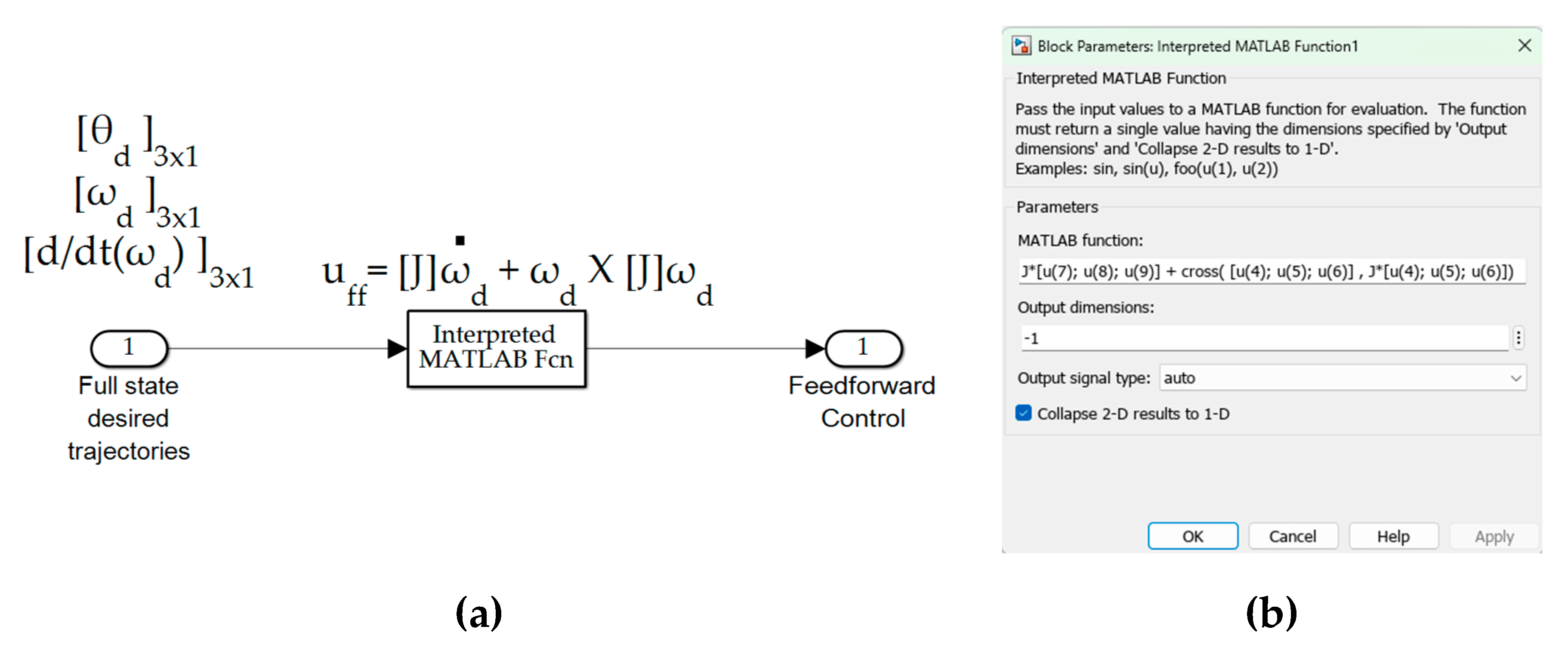

2.2. Feedforward Control Using Physics–Based Dynamic Embodiment

The feedforward instantiation of equation (3) is presented in equation (4) where the matrix of “knowns” necessitates having known angular velocities and angular accelerations. This necessity motivates the use of sinusoidal commanded trajectories, which will be shown to also aid estimation identifiability in section 2.9.

This embodiment may also be used in feedback, where actual trajectories are substituted for desired trajectories, and that instantiation is described later in section 2.8 Combined control.

Table 3.

Table of proximal variables and nomenclature 1.

Table 3.

Table of proximal variables and nomenclature 1.

| Variable/ acronym |

Definition |

Variable/ acronym |

Definition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Regression matrix of sensor data |

|

Regression matrix of desired states |

|

Unknown, predicted variables |

|

Estimated variables |

|

Total control signal |

|

Feedforward control signal |

|

|

|

inertia product |

|

|

|

inertia product |

|

|

|

inertia product |

2.3. Regression–Based Projection for Learning

Feedback may be used to project trajectory tracking errors (equation (5)) on the nonlinear, coupled system equations expressed in regression for in equation (4). The estimated torque is not likely provided by motion sensors (e.g. star trackers, sun sensors, limb lookers, etc.), so observers are investigated to provide the information (in addition to full state trajectories described later in section 2.8.

2.4. Luenberger Observers

Luenberger observers are sometimes referred to as state observers or simply observers and is well described in reference [

30] for observable systems recently ubiquitously defined in so–called “state space” form, or alternatively formulated in state–variable form. The discrete form of the estimator is often represented by the form presented in equation (7) for discrete time index

, states designated

, the “hat” ^ indicating an estimate, output

, where

is discretized state matrix and

is discretized observer gain matrix respectively.

Rather than adopting the ubiquitous form of equation (7), observers are presented in the following sections in topological form to highlight the enhancements to the observers.

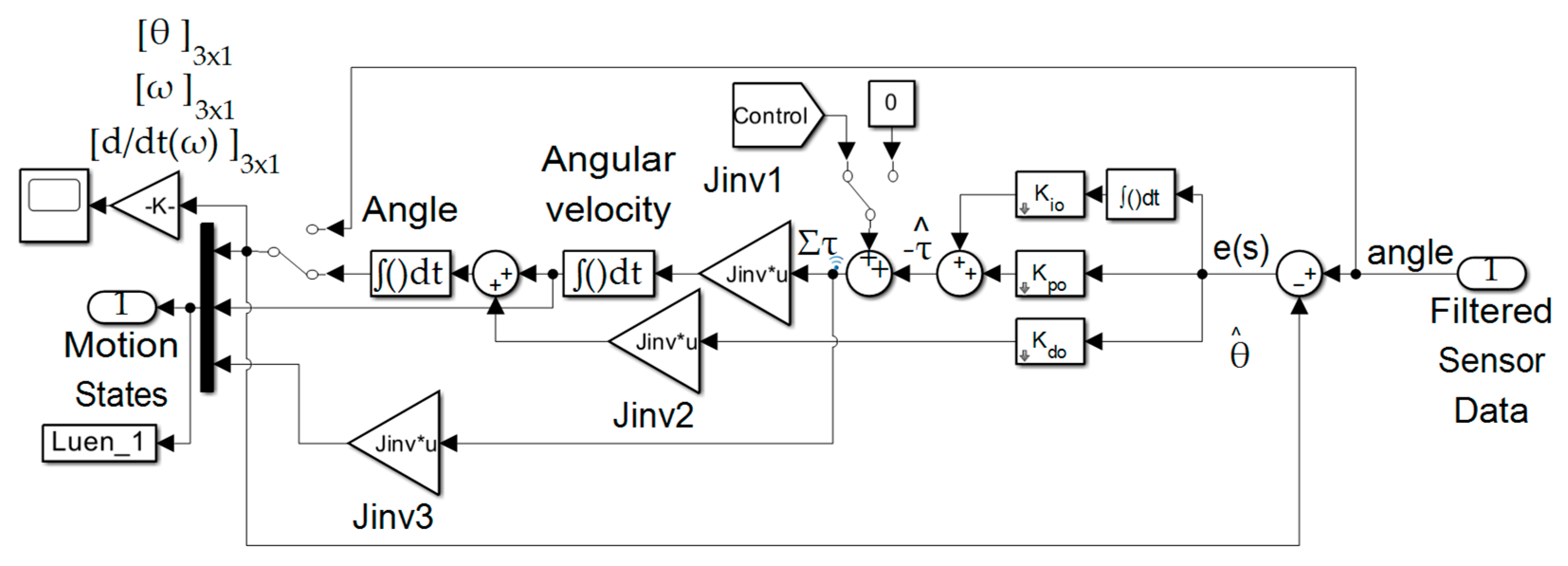

2.5. Enhanced Luenberger Observers

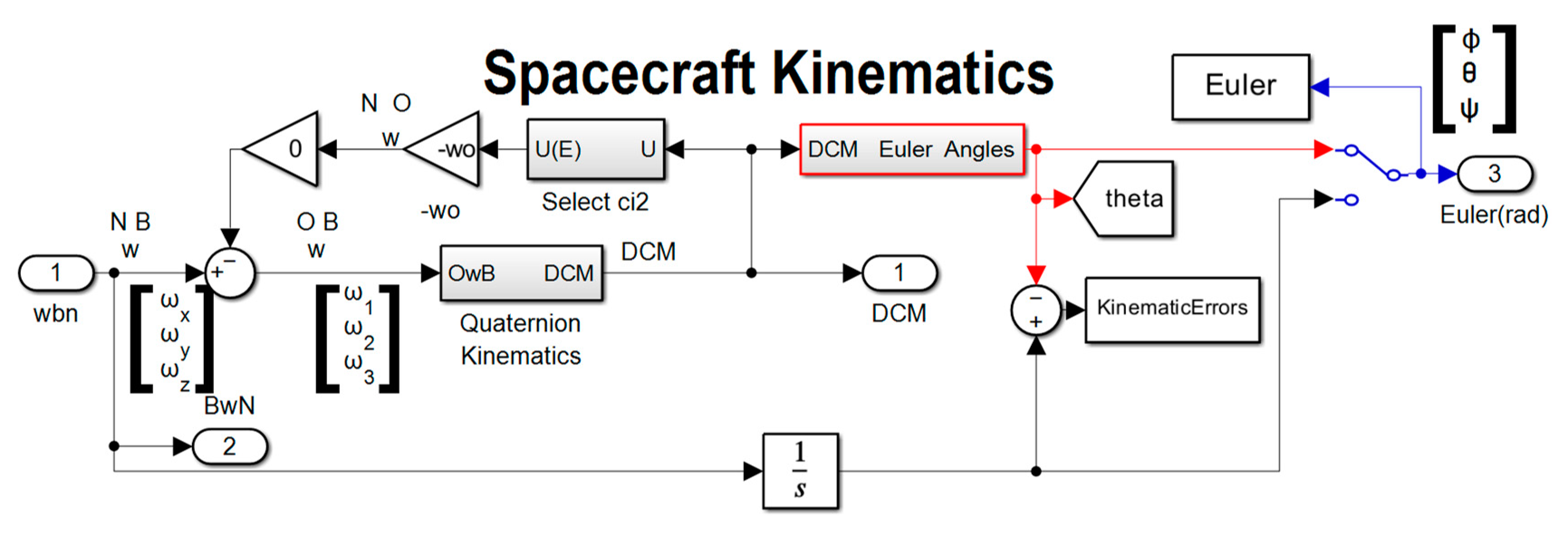

Notice in

Figure 4 the three channels on the right-hand side of the figure. The ubiquitous derivative channel is past forward (to the left of the graphic) of the next integrator compared to the integral and proportional channels. Since the signal to the left of an integrator (the integrator output) is the integral of the input signal, the input signal (to the right) is the derivative of the output signal, thus inducing derivative action on the input. This commonplace enhancement induces derivative action into the estimator without numerically differentiating noisy input signals.

Secondly, notice the top–center topology in

Figure 4 contains a manual switch with the control as a potential input. This enhancement is often applied to reduce or eliminate phase lag in the estimator.

Figure 4.

Luenberger and Enhanced Luenberger Observers built in MATLAB®/SIMULINK®.

Figure 4.

Luenberger and Enhanced Luenberger Observers built in MATLAB®/SIMULINK®.

Lastly notice the center channel or line passing down the middle of the estimator from right to left consists of a double-integrator of states lacking the cross–products of motion stemming from the transport theorem of mechanical motion relating the time derivative of a Euclidean vector as evaluated in a non-rotating coordinate system to its time derivative in a rotating reference frame. [

31] Adoption of enhancements accounting for transport theorem are presented in the following including nonlinear enhancements accounting for the nonlinear coupling nature of the transport theorem terms (the cross–products in equation (1).

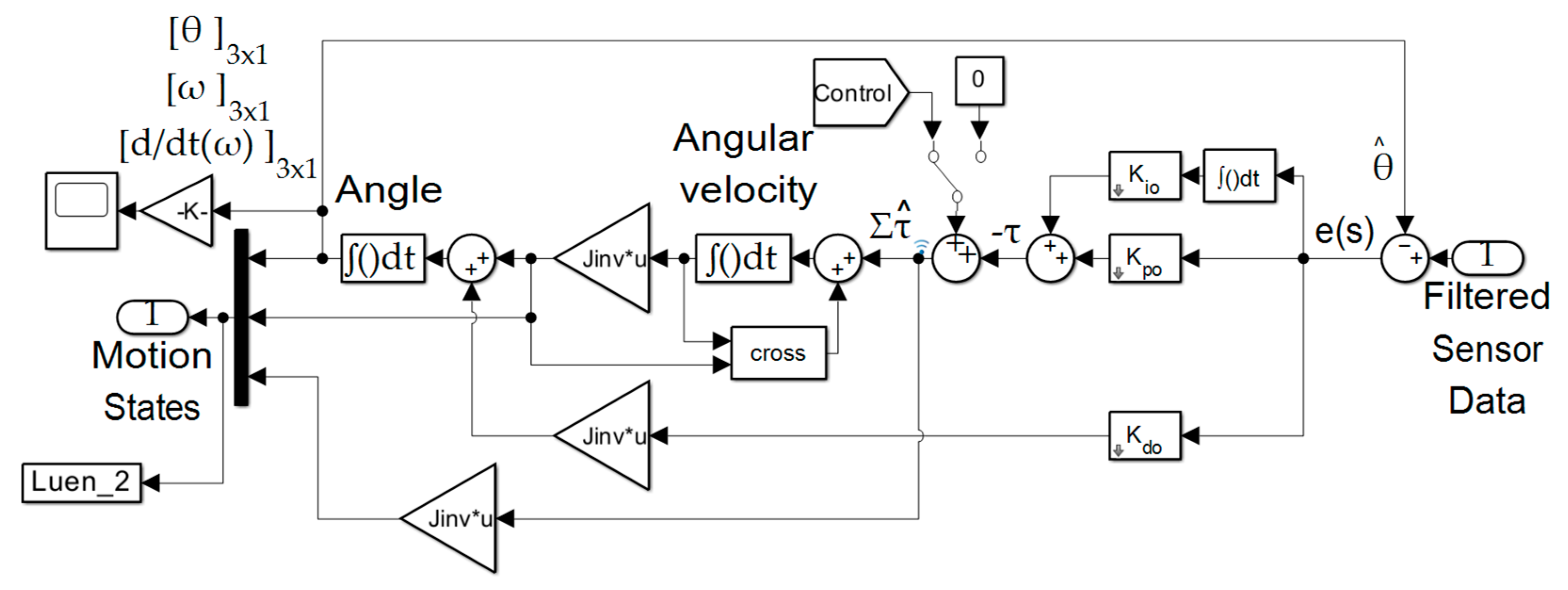

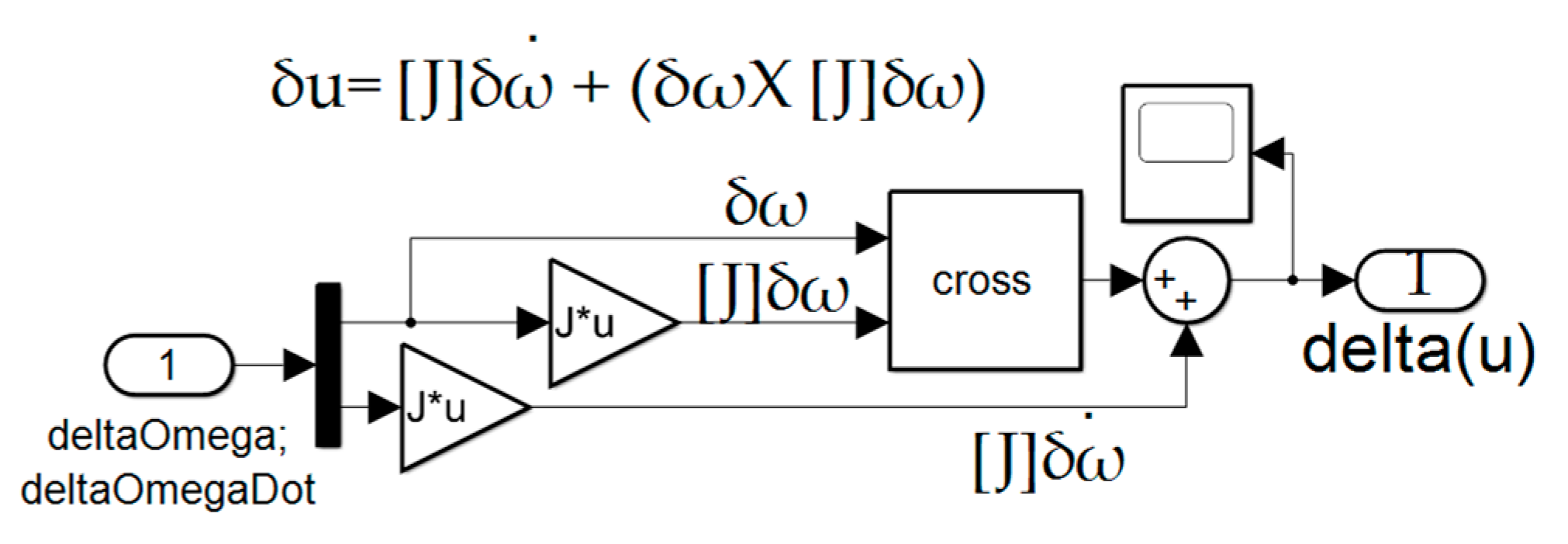

2.6. Nonlinear Enhanced Luenberger Observers

Notice

Figure 5 contains predominantly the same content as

Figure 4, the enhanced Luenberger observer. The new enhancements are depicted in the center of

Figure 5 where the angular velocity signal is extracted, scaled by the mass moments of inertia, then used to create the cross–products which are added to the baseline double–integrator signal.

Figure 5.

Nonlinear Enhanced Luenberger Observer built in MATLAB®/SIMULINK®.

Figure 5.

Nonlinear Enhanced Luenberger Observer built in MATLAB®/SIMULINK®.

2.6. Classical Feedback Adaption

Following initial parameterization in the inertial reference frame, classical feedback adaption was presented in [

32] in the body reference frame, greatly simplifying the algorithms, enhancing its usefulness as a contemporary replacement of the formerly ubiquitous M.I.T. Rule. [

33] The subsystem is displayed in Figure B.31 of

Appendix B codifying equation (8).

2.7. Two Norm Optimal Nonlinear, Projection Regression–Based Learning

An alternative to the classical feedback adaption approach is to project trajectory tracking errors onto the governing system equations parameterized into nonlinear regression form (without truncation, approximations, linearization, diagonalization, or other implications). The regression form is illustrated in the feedforward (

portion of equation (9)’s combined control, while the projection onto the system equations is displayed in the second term (

) using the two norm optimal pseudoinverse application of least squares. The subsystem is displayed in Figure B.32 of

Appendix B.

2.8. Combined Control

The feedforward control portion is identically the nonlinear, coupled governing equations of motion parameterized as a matrix

multiplied by a vector

where the matrix is built using desired (commanded) trajectories annotated by the subscribe “d”, while in feedback form, actual trajectories are used in accordance with equation (5). The need for actual trajectories justifies the investigation of contemporary enhancements to Luenberger observers in sections 2.4 and 2.5.

2.8. Estimating Location of the Center of Mass

Since the matrix of mass moments of inertia has not been diagonalized, the cross–products of inertia (off–diagonal matrix terms) may be used to locate the center of mass using the parallel axis theorem.

Figure 6 provides an illustrative example. Consider the desire to have a mass center located along the depicted central

axis. If the actual location is suspected to be at some other point, e.g. about the depicted

axis, the parallel axis theorem may be used to parameterize the problem.

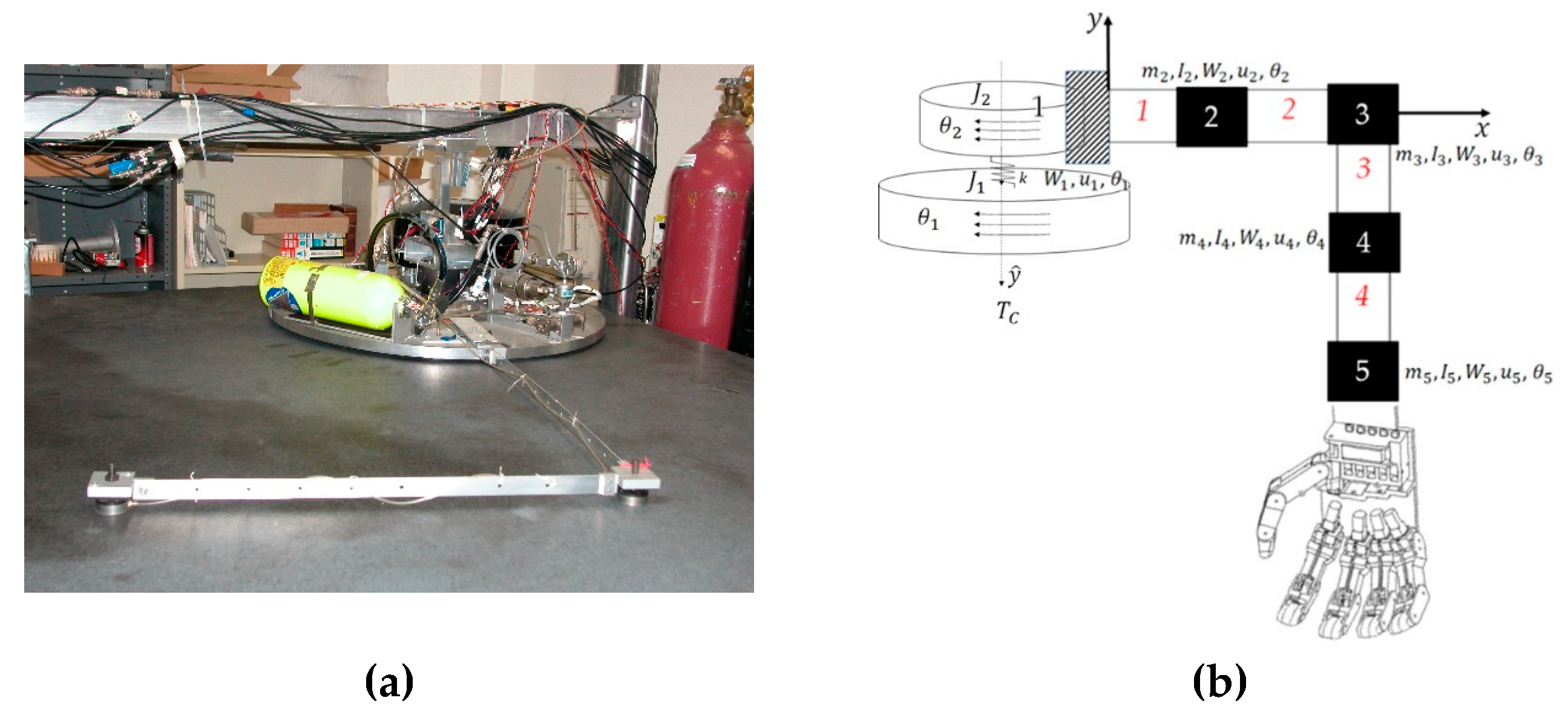

Figure 6.

Benchmark free–floating laboratory space gripper robot used in prequel studies. [

35] (

a) photo of laboratory hardware, (

b) schematic used for prequel engineering analyses.

Figure 6.

Benchmark free–floating laboratory space gripper robot used in prequel studies. [

35] (

a) photo of laboratory hardware, (

b) schematic used for prequel engineering analyses.

Table 4.

Table of proximal variables and nomenclature 1.

Table 4.

Table of proximal variables and nomenclature 1.

Variable /

acronym |

Definition |

Variable/ acronym |

Definition |

|

Mass index |

|

Defined in equation (4) |

|

Moment of inertia index |

|

Defined in equation (4) |

|

Moments of inertia |

|

Adaption gain |

|

Translational displacements |

|

Positive constant reference trajectory gain |

|

Rotational displacements |

|

Dynamic system matrix |

|

Control torque |

|

Combined error measure |

|

Feedforward control |

|

Differential angular velocity |

|

Control difference |

|

Differential angular acceleration |

|

Feedback control |

|

Differential time |

Following a brief presentation of the parallel axis theorem with a small proof, the parameterization is used to express three–dimensional locations ( coordinates) are revealed to be expressed strictly using the products of inertia. Thus, ubiquitous diagonalization of the inertia matrix by transforming basis vectors would eliminate the ability to use this formulation presented in equation (12).

Theorem.

Parallel axis theorem. The moment of inertiaabout some point other than the center of mass is the sum of the moment of inertiaabout the center of mass and the moment of inertia relative to the fixed distance between axes (andinFigure 6) in the rigid body represented by the product of the total mass and the square of the distance (See equation(11)).

The following proof mirrors [

32], since the version most closely illuminates the use of parallel axis theorem in this manuscript to reveal the three-dimensional location of the center of mass. The nomenclature of the proof in [

32] has been mapped to the nomenclature of the formerly investigated space robot. [

33]

Proof. Consider a rigid system of particles of mass

, rotating about a fixed axis

along axis

. Place the origin of the coordinate system at the center–of–mass (cm) of our system of particles. The general point

has coordinates (

,

), the

coordinate of

is a, and the

coordinate of

is

. Since the center of mass is at

, by the definition of the center-of-mass (the unique point at any given time where the weighted relative position of the distributed mass sums to zero, equation (12) results.

By definition, , where is measured from , not from mass center. Thus, leading to equation (13). But since and similarly for , the cross terms in equation (13) go to zero once the sum over is done leading to equation (14). Since , where is now measured from the mass center, and is just , where is the distance from O to the mass center, equation 32 results. □

Table 5.

Table of proximal variables and nomenclature 1.

Table 5.

Table of proximal variables and nomenclature 1.

|

Variable / acronym

|

Definition

|

Variable / acronym

|

Definition

|

|

|

|

Robot arm base parallel axis |

|

Inertia moment about mass center |

|

Body center parallel axis |

|

Total system mass |

|

Radius from parallel axis (not mass center) |

|

Distance from O to the mass center |

|

Radius vector to the mass center |

|

|

|

Differential mass element |

|

|

|

Center of mass coordinates |

|

|

|

|

Equation (12) is extracted from the short proof of parallel axis theorem, since it provides the time varying location of the mass center giving known (or estimated) values of the products of inertia (which would not be available if the matrix had been previously diagonalized by transformation from the body axes basis to the eigenvector basis frame. Thus, the next necessary step of analysis is to elaborate the ability to estimate the inertia matrix, where moments and products together are used to embody the control, while the products of inertia alone are used to parameterize the location of the mass center.

2.9. Persistent Excitation of Estimation

Simple step commands do not provide sufficiently rich input signals to produce faithful estimates of system parameters and locations of the center of mass. More “rich” input signals are utilized to increase estimation confidence.

Definition. Persistent excitation. Condition placed upon input commands to ensure the signals provide sufficient information over time to accurately estimate system parameters (eventually manifest as estimated locations of the system center of mass.

A finite impulse response model of order n involves the inversion of the

matrix in equation (16) where

is defined in equation (17) for control input signal

. Estimation will have a unique solution (i.e. the process is “identifiable”) if and only if the matrix in equation (16) is non–singular or invertible. [

36]

Table 6.

Table of proximal variables and nomenclature 1.

Table 6.

Table of proximal variables and nomenclature 1.

| Variable / acronym |

Definition |

Variable / acronym |

Definition |

|

Covariance dimension |

|

Control |

|

Dimension of the control |

|

Indexed time |

|

System equation |

|

Transposed system equation |

Impacts of persistent excitation on parameter convergence are described in [

37]. Modeling accuracy requires convergence of estimated parameters necessitating persistent excitation. Increased precision and faster convergence stems from relatively stronger excitation. Closed–loop stability of nonlinear, adaptive (or learning) systems is increased by bounding parameter estimation which is also aided by persistent excitation. A step command has one instance of excitation and accordingly only leads to reliable estimation of one parameter. Meanwhile, a sinusoidal command has two instances of excitation (as the curve oscillatory reverses direction twice) leading to reliable estimation of two parameters. Random signals (i.e. Gaussian) are very rich excitation, since values at any pair of times are identically distributed and statistically independent (and hence uncorrelated); and accordingly aid reliable estimation of any number of parameters. Accordingly, white noise is added to command signals in this investigation.

Table 7.

Persistent excitation of various input signals 1.

Table 7.

Persistent excitation of various input signals 1.

| Input signal |

Order of persistent excitation |

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

commands |

n |

Propositions for achieving exponentially convergent estimation when lacking persistent excitation is presented in [

38,

39]. In this research, the approach taken is to add small amplitude white noise to all input command signals, which are based on sinusoids as constructed in Figure B.27 (sinusoids) Figure B.29 (additional white noise) in

Appendix B.

Box 2. Input signal recommendation.

Recommended input command: To maximize persistent excitation, autonomous sinusoidal trajectories are recommended with white noise added.

2.10 Generic Robotics On-Orbit Trainer (GROOT) and Long Duration Propulsive EELV Secondary Payload Adapter (LDPE ESPA)

A generic, customizable simulation is the basic orbital and robotic simulation (BOARS), developed and maintains by NASA simulations and graphics branch [

40] including two orbital vehicles as depicted in

Figure 7 in arbitrary orbits. A robotic dynamic manipulator developed in collaboration with the United States Space Force (USSF) and used at the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School is attached to one of the vehicles called the Generic Robotics On-Orbit Trainer (GROOT). [

41] The software simulations developed and used to produce the results in section 3 of this manuscript utilize configurations scaled from those currently in use for GROOT.

Figure 7.

(a) NASA Basic Orbital and Robotic Simulation (BOARS), [

38] (

b) NASA Exploration Systems Simulations [

41] for mission concept evaluation and operational insight to flight crew. Image credit: NASA, used in accordance with published image use policy. [

5].

Figure 7.

(a) NASA Basic Orbital and Robotic Simulation (BOARS), [

38] (

b) NASA Exploration Systems Simulations [

41] for mission concept evaluation and operational insight to flight crew. Image credit: NASA, used in accordance with published image use policy. [

5].

2.11. Implementation Procedures

From section 2, an implementation procedure immerges, summarized in

Table 8. The procedure was implemented using MATLAB

®/SIMULINK

® where the subsystems are depicted in

Appendix B to aid repeatability by the readership.

Table 8.

Implementation procedure.

Table 8.

Implementation procedure.

-

Use the physics–based governing dynamics to embody the control (section 2.1)

Do not diagonalize the inertia matrix Do not linearize the governing equations of motion Establish classical feedback control as comparative benchmark

Implement nonlinear feedforward in equation (4) (section 2.2) Use nonlinear, enhanced Luenberger observers (section 2.5) to estimate all motion states and control. Use projection–based non–linear regression learning to learn the fully populated mass moments of inertia (masses and mass locations) including principal moments and off–diagonal products of inertia. (section 2.7) Use off–diagonal products of inertia to estimate location of the center of mass (section 2.8). |

Using the implementation procedure in

Table 9, simulations were created (as depicted in

Appendix B), where the results are next presented in section 3.

Table 9.

Algorithm 1: Pseudocode 1.

Table 9.

Algorithm 1: Pseudocode 1.

| |

|

| Input: |

Desired end state: final velocity and final acceleration |

| |

|

| Output: |

Inertia matrix components and three–dimensional coordinates of the center of gravity |

| |

|

| 1 begin |

|

| 2 |

Path planning using sinusoidal trajectories: |

| 3 |

DesiredVelocity = DesiredFinalVelocity * SineEquation |

| 4 |

DesiredAcceleration = DesiredFinalAcceleration * CosineEquation |

| 5 |

Assemble feedforward control |

| 6 |

Parameterize Euler’s moment equations into standard regression form |

| 7 |

Control_1 = DesiredStateMatrix * UnknownInertiaRegressionVector |

| 8 |

OptionalFeedback = DesiredStateMatrixInverse * EstimatedTorque |

| 9 |

EstimatedInertia = DesiredStateMatrixInverse * AppliedTorque |

| 10 |

MassCenterCoordinates = Function(InertiaCrossProducts) |

| 11 end |

|

3. Results

This section presents the results of simulations of the proposed autonomous, online center of mass determination together nonlinear, coupled control and inertia identification and nonlinear, enhanced Luenberger observers.

3.1. Section Description

Section 3.2 describes the developed results incrementally beginning with the unperturbed system followed by the comparative benchmark. Introduced next is dynamic nonlinear feedforward augmented by 1) PID feedback, and 2) inertia adaption. Next, dynamic, nonlinear feedforward with nonlinear, projection–based regression learning is applied. Estimation performance is compared next to evaluate Luenberger observer performance.

Section 3.3 performs identification of mass moments and products. Identification is compared using nonlinear adaption versus nonlinear, projection–based learning.

Section 3.4 extends the results of section 3.3 to reveal the time varying location of the center of mass again comparing nonlinear adaption versus nonlinear, projection–based learning. While the baseline maneuver was a single thirty–degree yaw maneuver, compound maneuvers are evaluated next before summary results are presented in section 3.5.

3.2. Incremental Development and Presentation of Results

First, an unperturbed system is analyzed with classical feedback control. Next, a comparative benchmark for the study is analyzed, a highly perturbed system with classical feedback control. The perturbations include uniform variations to all values in the inertia matrix; random variations (white noise) added to the control to aid estimation; random noise added to sensor outputs; magnetic disturbance torques, aerodynamic disturbance torques, solar radiation pressure disturbance torques, and gravity gradient disturbance torques.

3.2.1. Unperturbed System

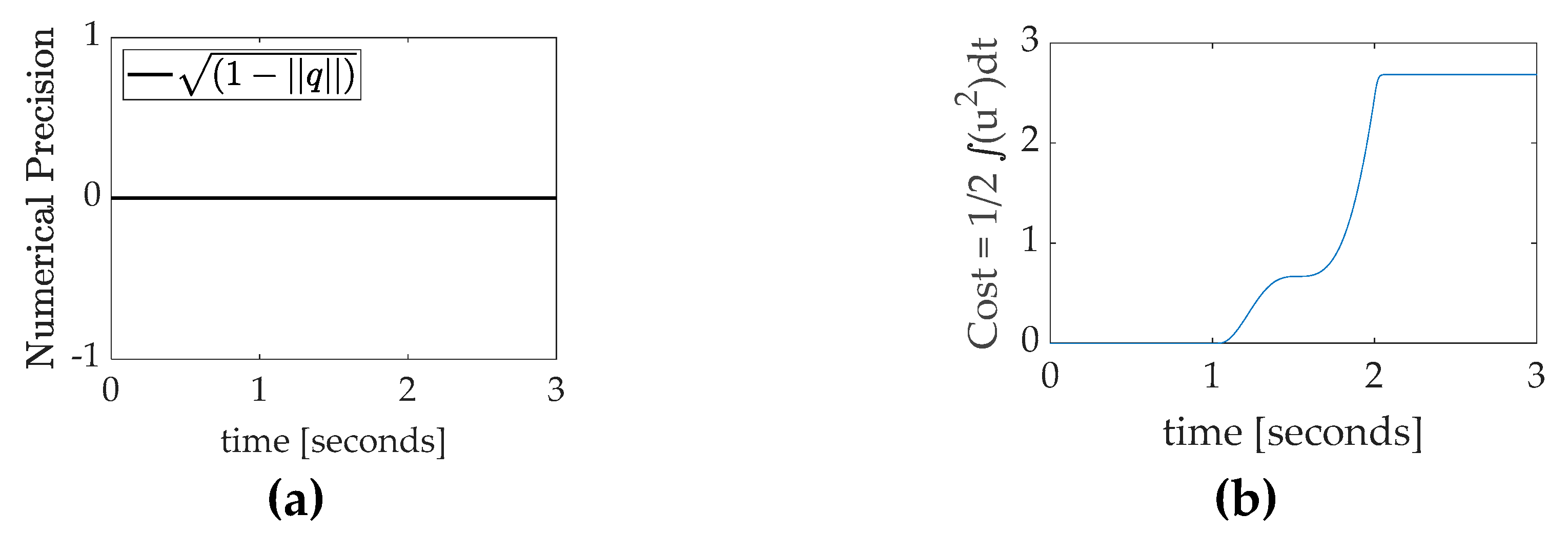

The unperturbed system if used to aid software troubleshooting and for investigating numeric precision. Numerical precision is studied using the quaternion normalization condition [

42] displayed in equation (18) as a figure of merit to iterate numerical integration solvers and evaluation step–sizes. Solvers and step–sizes were iterated until the error evaluating the quaternion normalization condition is always zero (or numeric zero) as displayed in

Figure 9. Also displayed in

Figure 9(b) is a display of the maneuver cost versus time, where cost is calculated as one half the time integral of the square of the control. Each case investigated is compared in part by the amount of control cost to perform the maneuver as one comparative figure of merit in addition to trajectory tracking error means and standard deviations.

Figure 9.

(a) Quaternion normalization condition from equation (18) used to validate numerical precision of simulation results. (b) Quadratic cost of maneuver.

Figure 9.

(a) Quaternion normalization condition from equation (18) used to validate numerical precision of simulation results. (b) Quadratic cost of maneuver.

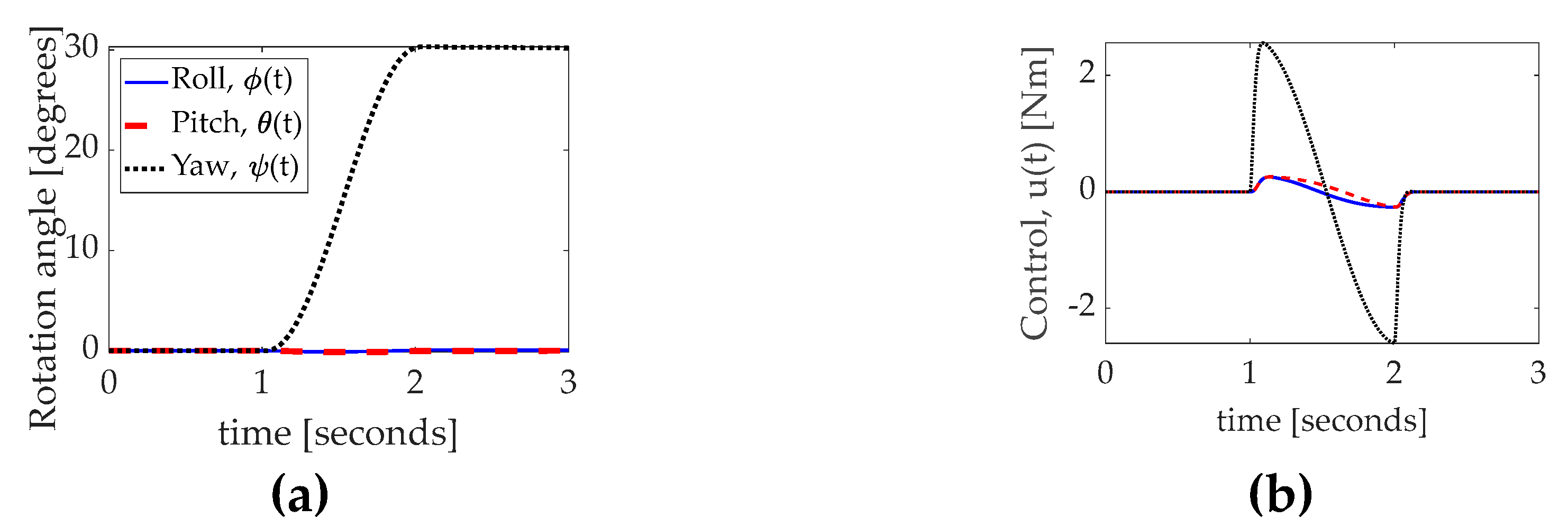

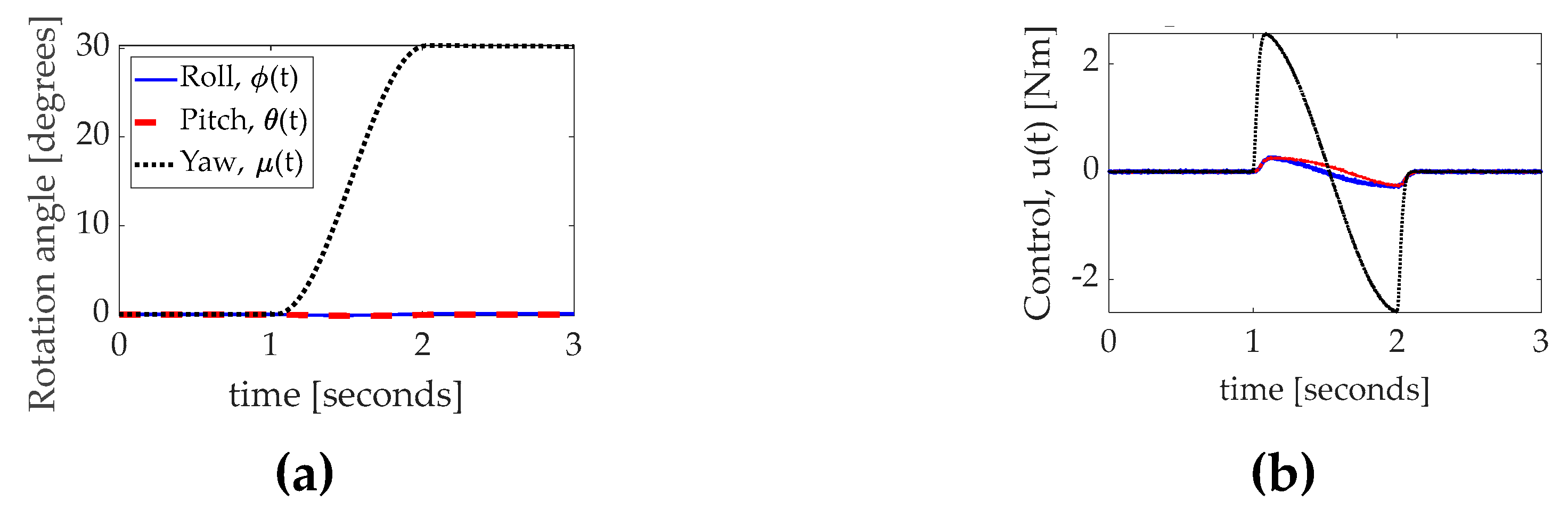

The initial case investigated is classical PID control of an unperturbed system without feedforward or inertia adaption or learning, and the case is presented in

Figure 10–

Figure 11 with quantitative data presented in

Table 10.

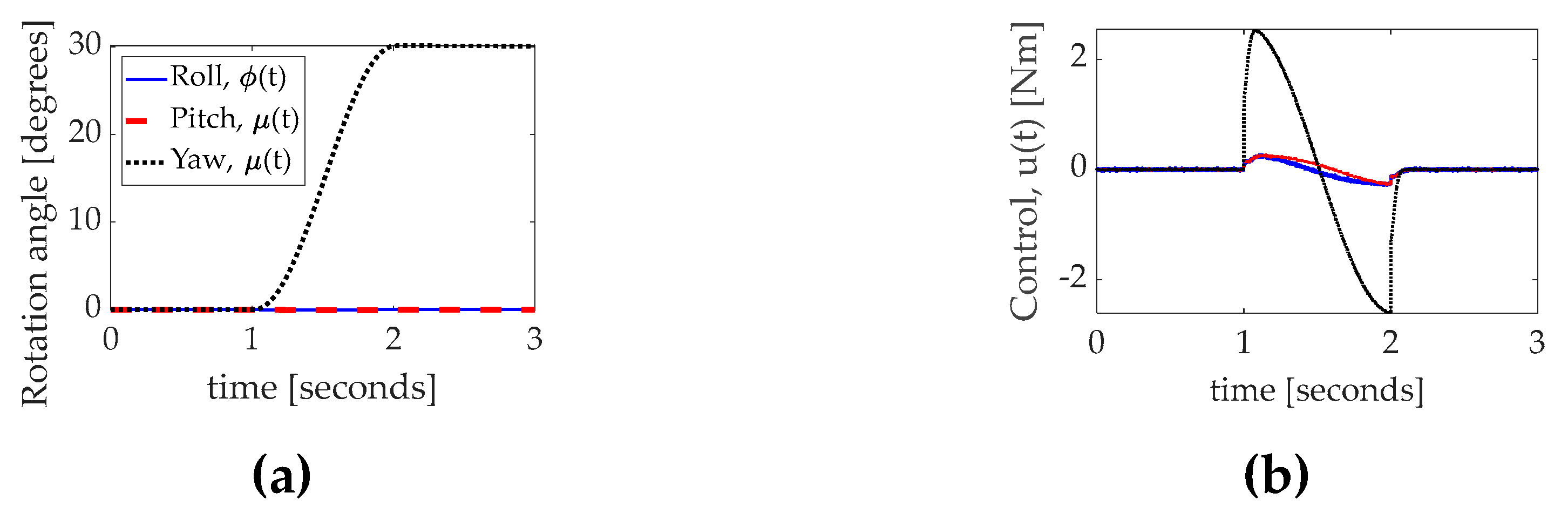

Figure 10.

(

a) Rotation during unperturbed system maneuver: thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant with roll as solid blue line, pitch as dashed red line, and yaw as dotted black line. The three–dimensional maneuver data presented together in

Figure 9(a) is elaborated separately in

Figure 11; (

b) control utilized during the maneuver. Quantitative data corresponding to the qualitative display in

Figure 10 is presented in

Table 10.

Figure 10.

(

a) Rotation during unperturbed system maneuver: thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant with roll as solid blue line, pitch as dashed red line, and yaw as dotted black line. The three–dimensional maneuver data presented together in

Figure 9(a) is elaborated separately in

Figure 11; (

b) control utilized during the maneuver. Quantitative data corresponding to the qualitative display in

Figure 10 is presented in

Table 10.

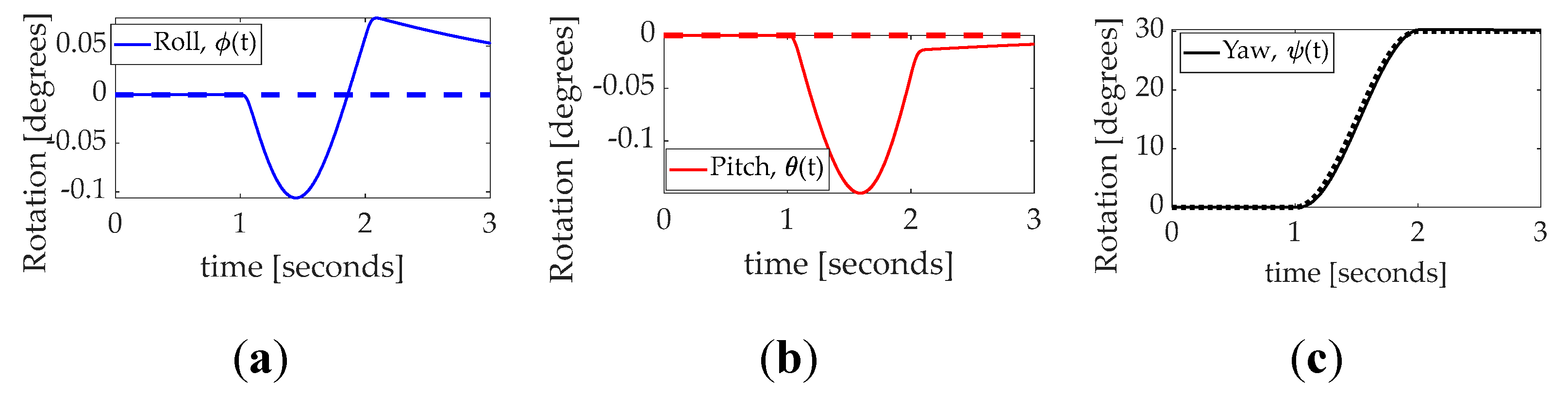

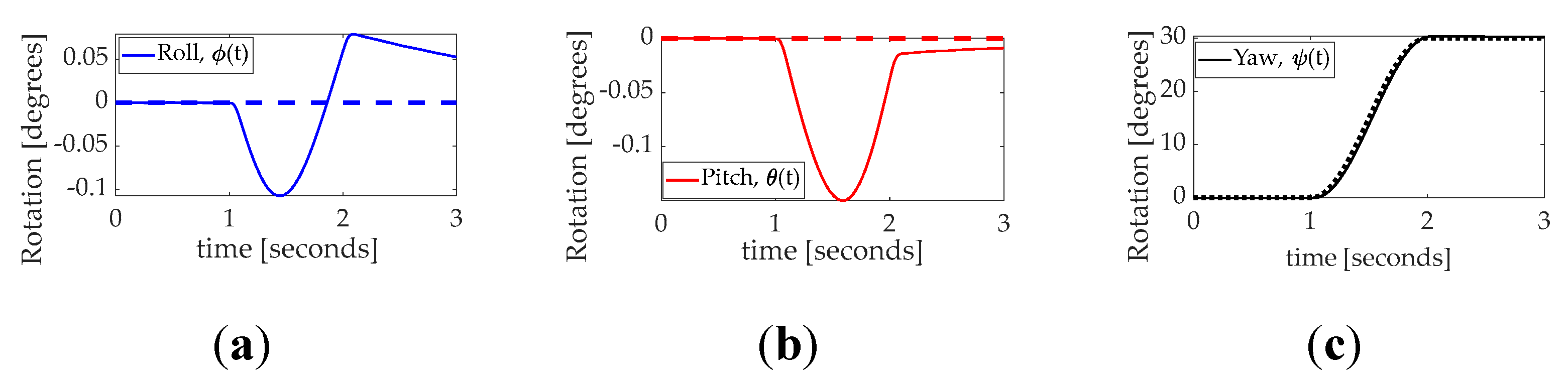

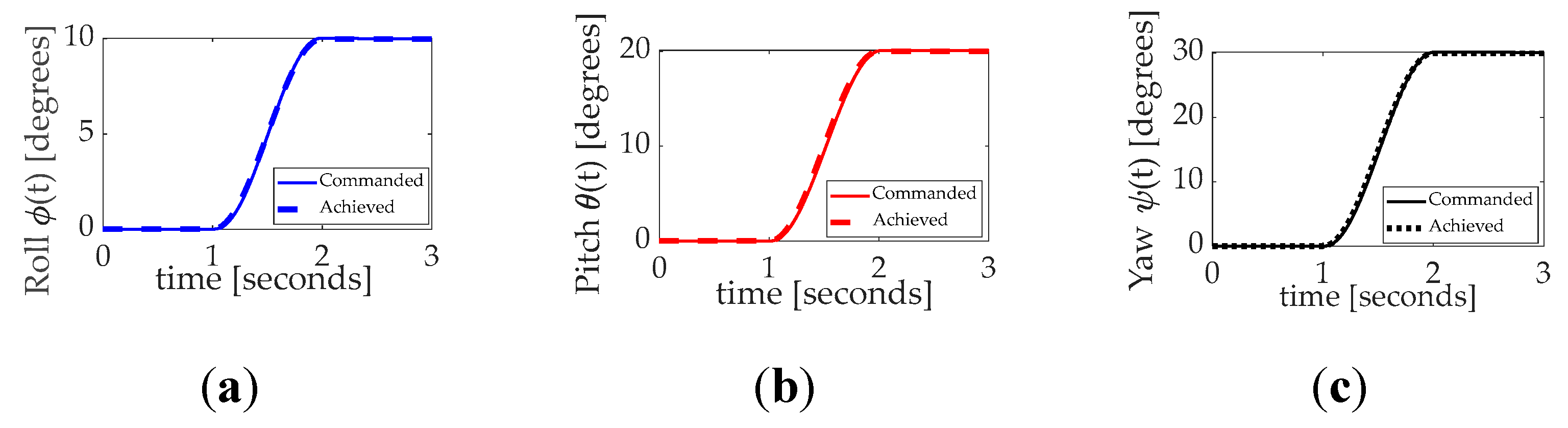

Figure 11.

Commanded rotation versus actual rotation during unperturbed thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant. (a) roll; (b) pitch; (c) yaw. Commanded rotation versus actual rotation during highly perturbed thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant. (a) roll; (b) pitch; (c) yaw. Quantitative data corresponding to the qualitative display in

Figure 11 is presented in

Table 10.

Figure 11.

Commanded rotation versus actual rotation during unperturbed thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant. (a) roll; (b) pitch; (c) yaw. Commanded rotation versus actual rotation during highly perturbed thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant. (a) roll; (b) pitch; (c) yaw. Quantitative data corresponding to the qualitative display in

Figure 11 is presented in

Table 10.

Table 10.

PID controlled unperturbed system.

Table 10.

PID controlled unperturbed system.

|

Roll [degrees] |

Pitch [degrees] |

Yaw [degrees] |

| Mean |

|

|

|

| Standard deviation 1

|

|

|

|

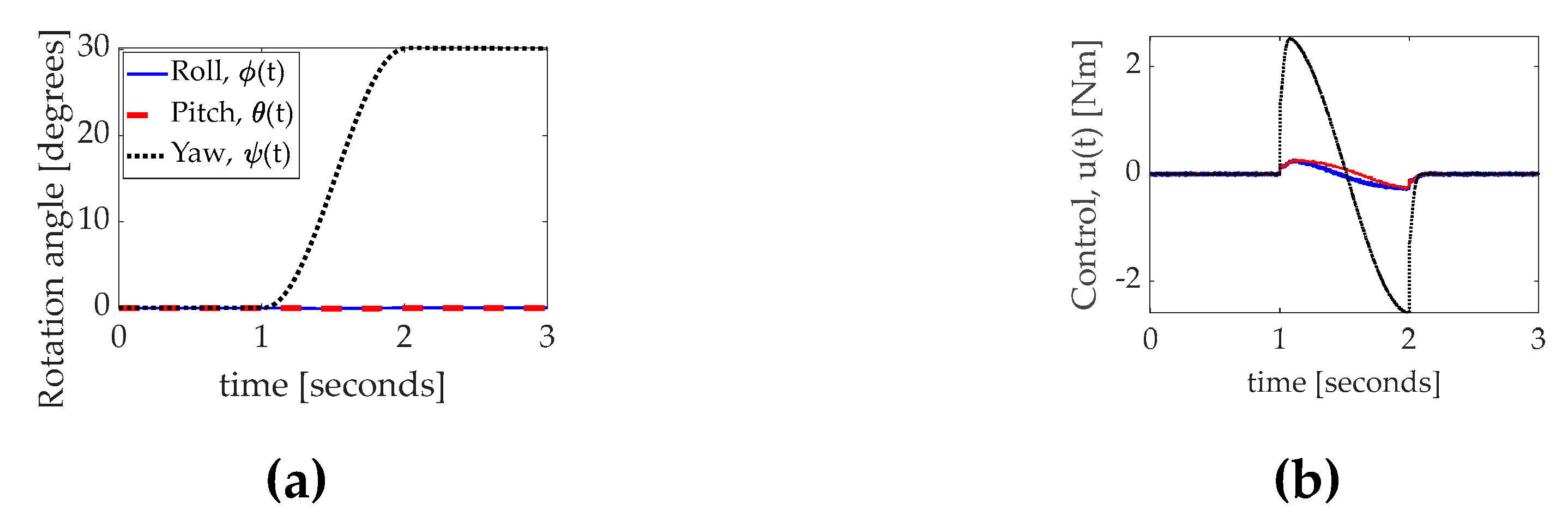

3.2.2. Comparative Benchmark

The comparative benchmark case of classical PID control without feedforward or learning controlling a highly perturbed system with sensor noise is presented in

Figure 12–

Figure 13 with quantitative data presented in

Table 11.

Figure 12a simultaneously displays the roll, pitch, and yaw angles with respect to time. The commanded rotational maneuver is a thirty–degree yaw tracking a sinusoidal trajectory with no commanded roll or pitch, and the maneuver is performed with precision. The three axis controls are displayed in

Figure 12b, notice the largest control corresponds to the yaw channel, while the relative smaller two channels of control counter cross–coupled motion inherent with a fully populated inertia matrix.

Figure 13 displays the same maneuver data as

Figure 12a separated into three displays, one for each axis of motion: roll, pitch, and yaw. The three plots present qualitative information that matches quantitative presentation of data in

Table 11.

Figure 12.

(

a) Rotation during unperturbed system maneuver: thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant with roll as solid blue line, pitch as dashed red line, and yaw as dotted black line. The three–dimensional maneuver data presented together in

Figure 9(a) is elaborated separately in

Figure 11; (

b) control utilized during the maneuver. Quantitative data corresponding to the qualitative display in

Figure 10 is presented in

Table 10.

Figure 12.

(

a) Rotation during unperturbed system maneuver: thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant with roll as solid blue line, pitch as dashed red line, and yaw as dotted black line. The three–dimensional maneuver data presented together in

Figure 9(a) is elaborated separately in

Figure 11; (

b) control utilized during the maneuver. Quantitative data corresponding to the qualitative display in

Figure 10 is presented in

Table 10.

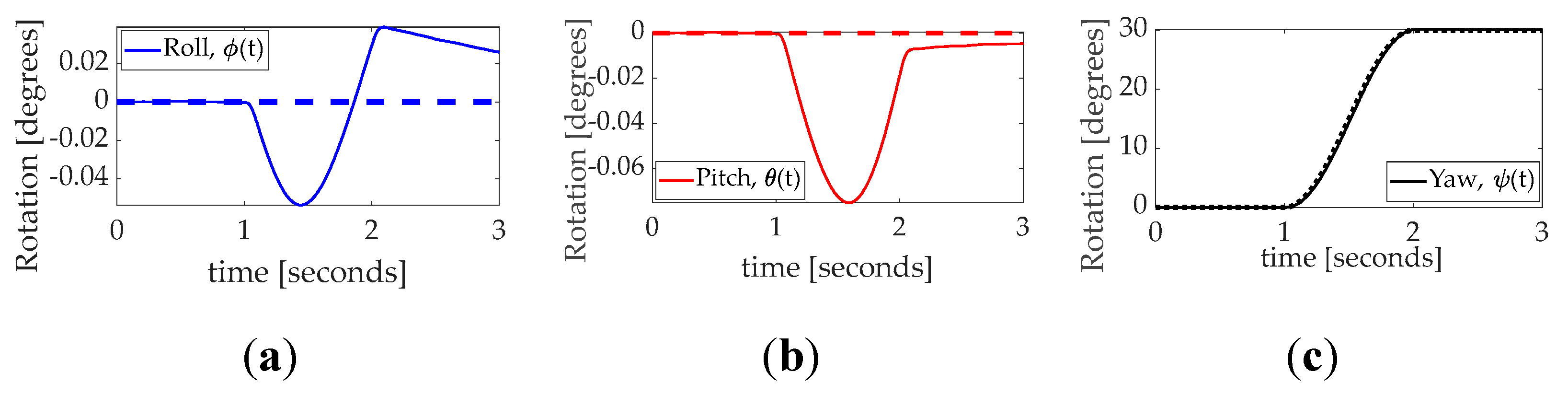

Figure 13.

PID controlled highly perturbed system: uniformly varied inertia, sensors with white noise. Commanded rotation versus actual rotation during highly perturbed thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant. (

a) roll; (

b) pitch; (

c) yaw. Commanded rotation versus actual rotation during highly perturbed thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant. (a) roll; (b) pitch; (c) yaw. Quantitative data corresponding to the qualitative display in

Table 11 is presented in

Table 13.

Figure 13.

PID controlled highly perturbed system: uniformly varied inertia, sensors with white noise. Commanded rotation versus actual rotation during highly perturbed thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant. (

a) roll; (

b) pitch; (

c) yaw. Commanded rotation versus actual rotation during highly perturbed thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant. (a) roll; (b) pitch; (c) yaw. Quantitative data corresponding to the qualitative display in

Table 11 is presented in

Table 13.

Table 11.

PID controlled highly perturbed system: uniformly varied inertia, sensors with white noise, thirty–degree yaw maneuver tracking errors.

Table 11.

PID controlled highly perturbed system: uniformly varied inertia, sensors with white noise, thirty–degree yaw maneuver tracking errors.

|

Roll [degrees] |

Pitch [degrees] |

Yaw [degrees] |

| Mean |

|

|

|

| Standard deviation 1

|

|

|

|

3.2.3. Dynamic Nonlinear Feedforward with PID Feedback and Inertia Adaption

Having foremost established idealized performance controlling an unperturbed system, next the controlled system was perturbed with some performance degradation. Next, this section displays the results of adding dynamic nonlinear feedforward and inertia adaption. Efforts were not made to optimize the adaption or the feedback gains, since tracking errors assist estimation of mass center location (the goal of the study).

Figure 14.

Dynamic nonlinear feedforward with PID feedback and inertia adaption. (

a) Rotation during highly perturbed (uniformly varied inertia, sensors with white noise) thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant with roll as solid blue line, pitch as dashed red line, and yaw as dotted black line. Quantitative data corresponding to the qualitative display in

Figure 14 is presented in

Table 13.

Figure 14.

Dynamic nonlinear feedforward with PID feedback and inertia adaption. (

a) Rotation during highly perturbed (uniformly varied inertia, sensors with white noise) thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant with roll as solid blue line, pitch as dashed red line, and yaw as dotted black line. Quantitative data corresponding to the qualitative display in

Figure 14 is presented in

Table 13.

Figure 15.

Dynamic nonlinear feedforward with PID feedback and inertia adaption. Commanded rotation versus actual rotation during highly perturbed thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant. (

a) roll; (

b) pitch; (

c) yaw. Commanded rotation versus actual rotation during highly perturbed thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant. (a) roll; (b) pitch; (c) yaw. Quantitative data corresponding to the qualitative display

Figure 15 is presented in

Table 13.

Figure 15.

Dynamic nonlinear feedforward with PID feedback and inertia adaption. Commanded rotation versus actual rotation during highly perturbed thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant. (

a) roll; (

b) pitch; (

c) yaw. Commanded rotation versus actual rotation during highly perturbed thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant. (a) roll; (b) pitch; (c) yaw. Quantitative data corresponding to the qualitative display

Figure 15 is presented in

Table 13.

Table 12.

Dynamic nonlinear feedforward with PID feedback and inertia adaption. Highly perturbed (uniformly varied inertia, sensors with white noise) thirty–degree yaw maneuver tracking errors.

Table 12.

Dynamic nonlinear feedforward with PID feedback and inertia adaption. Highly perturbed (uniformly varied inertia, sensors with white noise) thirty–degree yaw maneuver tracking errors.

|

Roll [degrees] |

Pitch [degrees] |

Yaw [degrees] |

| Mean |

|

|

|

| Standard deviation 1

|

|

|

|

3.2.4. Dynamic Nonlinear Feedforward with PID Feedback and Nonlinear Projection–Based Regression Learning

Having in the previous section displayed the results of adding dynamic nonlinear feedforward and inertia adaption, this section replaces inertia adaption with nonlinear projection–based regression learning. As before, efforts were not made to optimize the adaption or the feedback gains, since tracking errors assist estimation of mass center location (the goal of the study).

Figure 16.

Dynamic nonlinear feedforward with PID feedback and nonlinear projection–based regression learning. (

a) Rotation during highly perturbed (uniformly varied inertia, sensors with white noise) thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant with roll as solid blue line, pitch as dashed red line, and yaw as dotted black line. Quantitative data corresponding to the qualitative display in

Figure 16 is presented in

Table 13.

Figure 16.

Dynamic nonlinear feedforward with PID feedback and nonlinear projection–based regression learning. (

a) Rotation during highly perturbed (uniformly varied inertia, sensors with white noise) thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant with roll as solid blue line, pitch as dashed red line, and yaw as dotted black line. Quantitative data corresponding to the qualitative display in

Figure 16 is presented in

Table 13.

Figure 17.

Dynamic nonlinear feedforward with PID feedback nonlinear projection–based regression learning. Commanded rotation versus actual rotation during highly perturbed thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant. (

a) roll; (

b) pitch; (

c) yaw. Commanded rotation versus actual rotation during highly perturbed thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant. (a) roll; (b) pitch; (c) yaw. Quantitative data corresponding to the qualitative display in

Figure 17 is presented in

Table 13.

Figure 17.

Dynamic nonlinear feedforward with PID feedback nonlinear projection–based regression learning. Commanded rotation versus actual rotation during highly perturbed thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant. (

a) roll; (

b) pitch; (

c) yaw. Commanded rotation versus actual rotation during highly perturbed thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant. (a) roll; (b) pitch; (c) yaw. Quantitative data corresponding to the qualitative display in

Figure 17 is presented in

Table 13.

Table 13.

Dynamic nonlinear feedforward with PID feedback and nonlinear feedforward nonlinear projection–based regression learning. Highly perturbed (uniformly varied inertia, sensors with white noise) thirty–degree yaw maneuver tracking errors.

Table 13.

Dynamic nonlinear feedforward with PID feedback and nonlinear feedforward nonlinear projection–based regression learning. Highly perturbed (uniformly varied inertia, sensors with white noise) thirty–degree yaw maneuver tracking errors.

|

0.0075635 |

Roll [degrees] |

Pitch [degrees] |

Yaw [degrees] |

| Mean |

|

|

|

| Standard deviation 1

|

|

|

|

Box 3. Identical tracking: adaption vs. nonlinear projection–based regression learning.

Estimation vs. tracking control: Notice identical trajectory tracking results in

Table 12 and

Table 13. Adaption and nonlinear projection–based regression learning methods are strictly used to estimate inertia components and mass center location and do not affect trajectory tracking performance.

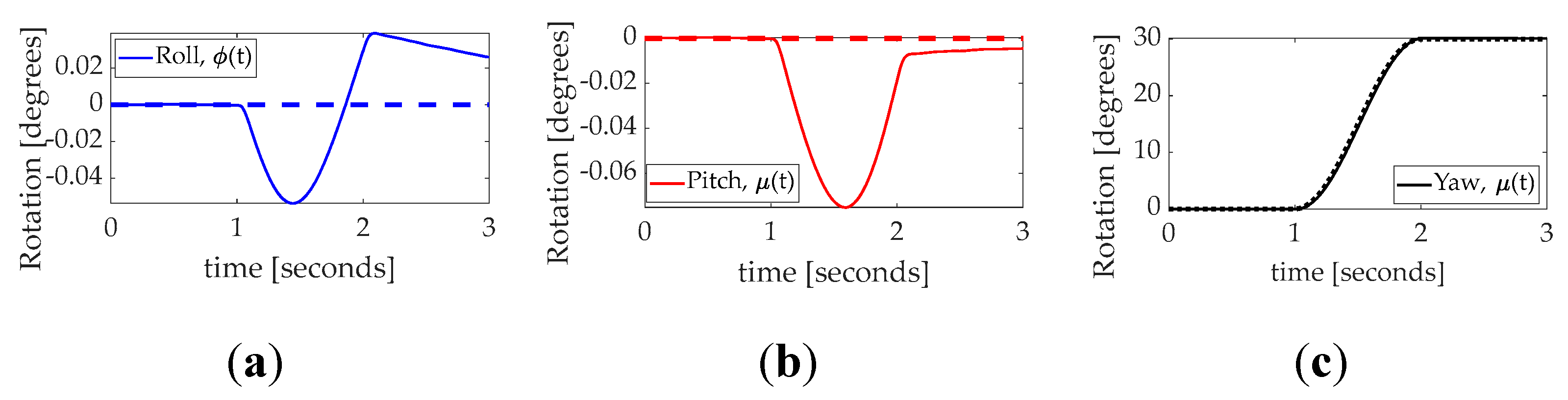

3.2.5. Estimator Performance Comparison

With the backdrop of introducing tracking control options, the remaining topic of study is the performance of state estimation by disparate Luenberger observers. Those estimated states are used by both the inertia adaption scheme and the nonlinear projection–based regression learning. The goal of the comparison is merely to choose the Luenberger instantiations. The observer comparison is presented qualitatively in

Figure 18 and quantitatively in

Table 14. The nonlinear, enhanced observer was slightly superior in the maneuver axis, but relatively substantially inferior in the non–maneuver axes.

Figure 18.

Estimated actual rotation during highly perturbed thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and estimated rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant. (

a) roll; (

b) pitch; (

c) yaw. Actual rotation angle (dashed blue line), rotation angle estimated by enhanced Luenberger observer (dotted red line), and rotation angle estimated by enhanced, nonlinear Luenberger observers. (a) roll; (b) pitch; (c) yaw. Quantitative data corresponding to the qualitative display in

Figure 18 is presented in

Table 14.

Figure 18.

Estimated actual rotation during highly perturbed thirty–degree yaw with time in seconds on the abscissa and estimated rotation angle in degrees on the ordinant. (

a) roll; (

b) pitch; (

c) yaw. Actual rotation angle (dashed blue line), rotation angle estimated by enhanced Luenberger observer (dotted red line), and rotation angle estimated by enhanced, nonlinear Luenberger observers. (a) roll; (b) pitch; (c) yaw. Quantitative data corresponding to the qualitative display in

Figure 18 is presented in

Table 14.

Table 14.

Observer estimation percent performance comparison. Highly perturbed (uniformly varied inertia, sensors with white noise) thirty–degree yaw maneuver tracking errors.

Table 14.

Observer estimation percent performance comparison. Highly perturbed (uniformly varied inertia, sensors with white noise) thirty–degree yaw maneuver tracking errors.

| |

Mean roll

[degrees] |

Mean pitch

[degrees] |

Mean yaw

[degrees] |

| Benchmark Luenberger |

|

|

|

| Nonlinear Luenberger 1

|

77% |

144.58% |

-1.02% |

Box 4. Observer recommendation.

Observer recommendation: Simultaneous use of both Luenberger styles is recommended to leverage their relative strengths in the maneuver–axis and non–maneuver axis.

3.3. Identification of Mass Moments and Products

The estimations from the Luenberger observers are used to estimate inertia moments and products using two disparate methods: nonlinear adaption, and nonlinear projection–based regression learning described respectively in sections 3.3.1 and 3.3.2.

3.3.1. Identification of Mass Moments and Products by Nonlinear Adaption

Nonlinear adaption as proposed in [

43] and improved in [

44] and [

45] were utilized to estimate the six inertia moments and products. The method was simulated in [

46] and experimentally validated in [

47].

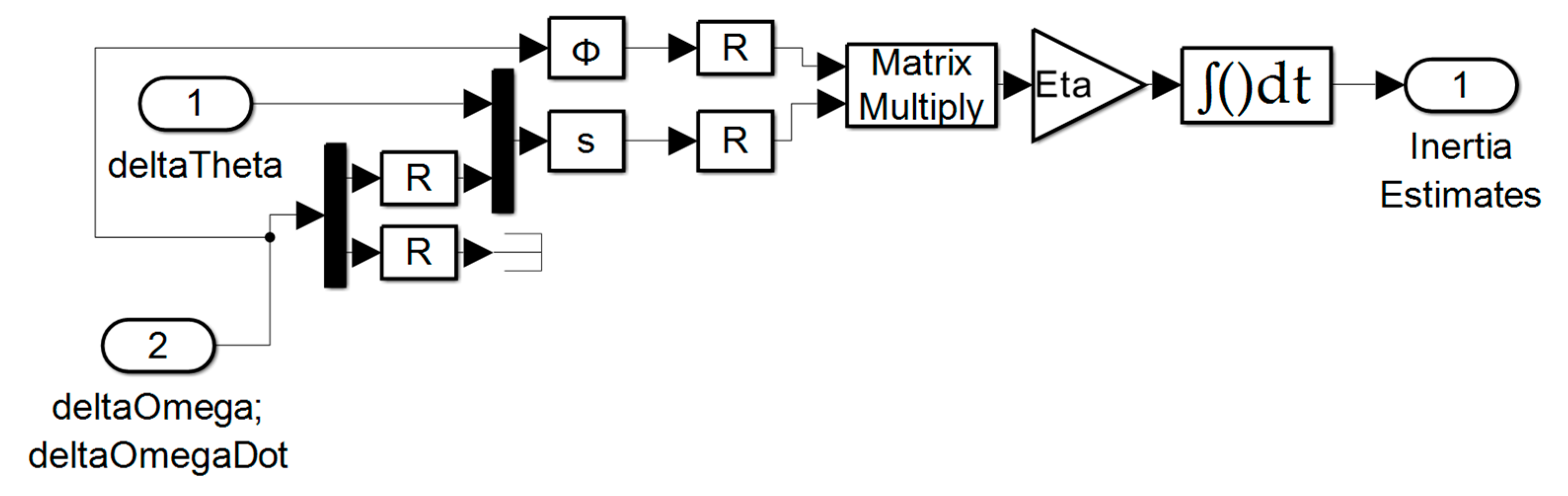

A combined measure of error linearly combines angular acceleration and velocities using a constant gain. The gained, combined measure of error is multiplied by the system matrix with an adaption gain to establish the adaption rate which is integrated to produce inertia component adaptions. The MATLAB®/SIMULINK® simulation subsystems are presented in appendix B.

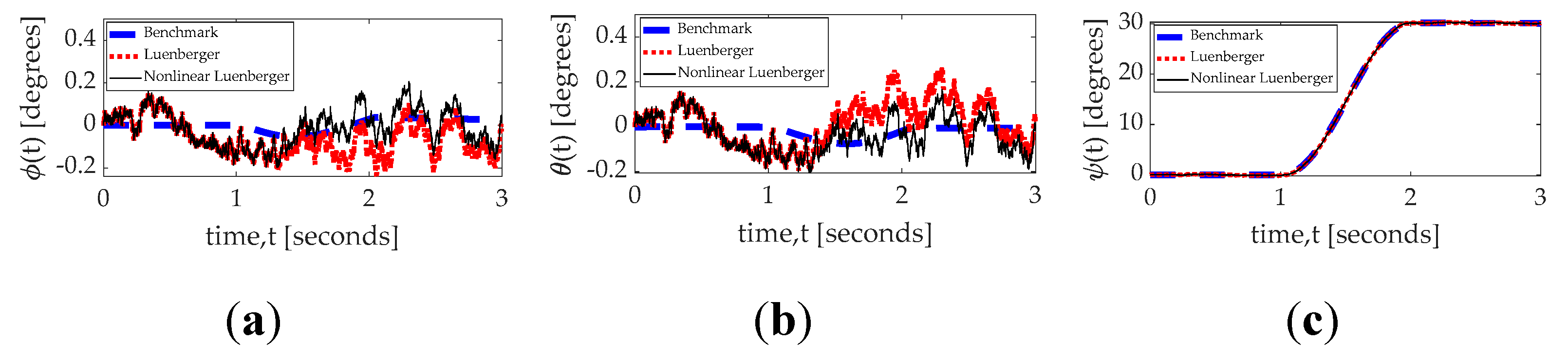

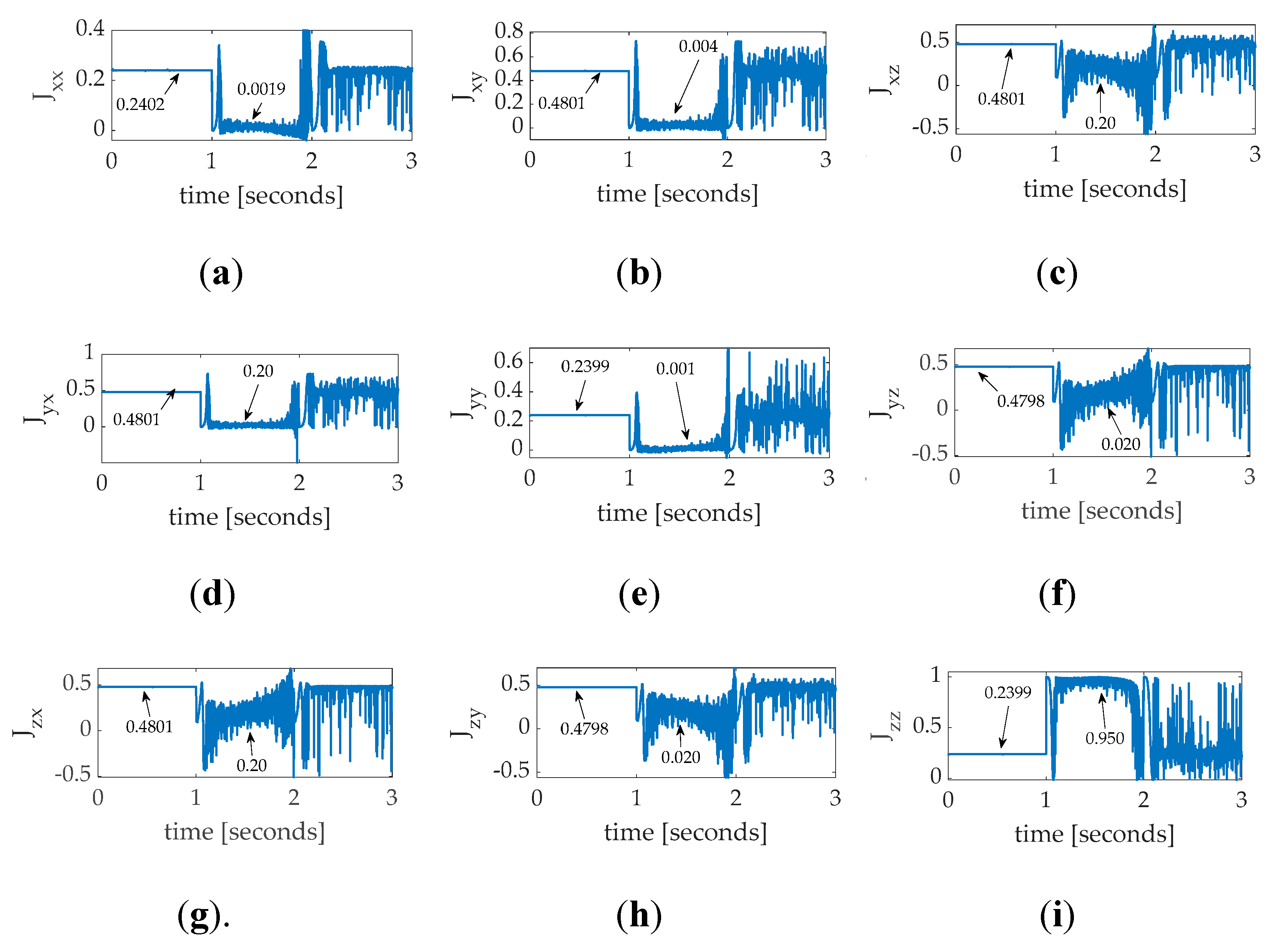

Figure 19.

Nonlinear adaption derived inertia moments and products: Time varying mass moments and products for a single, thirty–degree yaw maneuver with coupled motion in roll and pitch, where the command has white noise added to aid persistent excitation (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) ; (e) ; (f) ; (g) ; (h) ; (i) . Notice the initial flat–line behavior during the initial quiescent period is followed by rapid location learning during the maneuver excitement, lastly followed by a slow, oscillatory settling following the maneuver during regulation. The moments and products of inertia seem to converge towards a certain value during the maneuver excitation but not during either period of regulation, lacking persistent excitation.

Figure 19.

Nonlinear adaption derived inertia moments and products: Time varying mass moments and products for a single, thirty–degree yaw maneuver with coupled motion in roll and pitch, where the command has white noise added to aid persistent excitation (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) ; (e) ; (f) ; (g) ; (h) ; (i) . Notice the initial flat–line behavior during the initial quiescent period is followed by rapid location learning during the maneuver excitement, lastly followed by a slow, oscillatory settling following the maneuver during regulation. The moments and products of inertia seem to converge towards a certain value during the maneuver excitation but not during either period of regulation, lacking persistent excitation.

3.3.2. Identification of Mass Moments and Products by Nonlinear Projection–Based Regression Learning

Nonlinear projection–based regression learning as proposed just last year in [

48] to learn the six inertia moments and products. Referring to

Figure 20, the method utilized included analysis and simulation, while validating experimentation is proposed in this present manuscript.

Figure 20.

Process stages adopted in this study: analyze and hypothesize followed by verification of analysis with modeling and simulation validated experimentally.

Figure 20.

Process stages adopted in this study: analyze and hypothesize followed by verification of analysis with modeling and simulation validated experimentally.

Angle trajectory tracking error alone (not in a combine error measure as done with nonlinear adaption) is projected on the system matrix used to embody the nonlinear feedforward control parameterized in regression form without linearization, diagonalization, or otherwise simplification.

Figure 21 reveals the mass moments and products estimated by the learning algorithm, while the corresponding MATLAB

®/SIMULINK

® simulation subsystems are presented in appendix B.

Figure 21.

Projection regression–based learning inertia moments and products: Time varying mass moments and products for a single, thirty–degree yaw maneuver with coupled motion in roll and pitch, where the command has white noise added to aid persistent excitation (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) ; (e) ; (f) ; (g) ; (h) ; (i) . Notice the initial flat–line behavior during the initial quiescent period is followed by rapid location learning during the maneuver excitement, lastly followed by a slow, oscillatory settling following the maneuver during regulation. The moments and products of inertia seem to converge towards a certain value during the maneuver excitation but not during either period of regulation, lacking persistent excitation.

Figure 21.

Projection regression–based learning inertia moments and products: Time varying mass moments and products for a single, thirty–degree yaw maneuver with coupled motion in roll and pitch, where the command has white noise added to aid persistent excitation (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) ; (e) ; (f) ; (g) ; (h) ; (i) . Notice the initial flat–line behavior during the initial quiescent period is followed by rapid location learning during the maneuver excitement, lastly followed by a slow, oscillatory settling following the maneuver during regulation. The moments and products of inertia seem to converge towards a certain value during the maneuver excitation but not during either period of regulation, lacking persistent excitation.

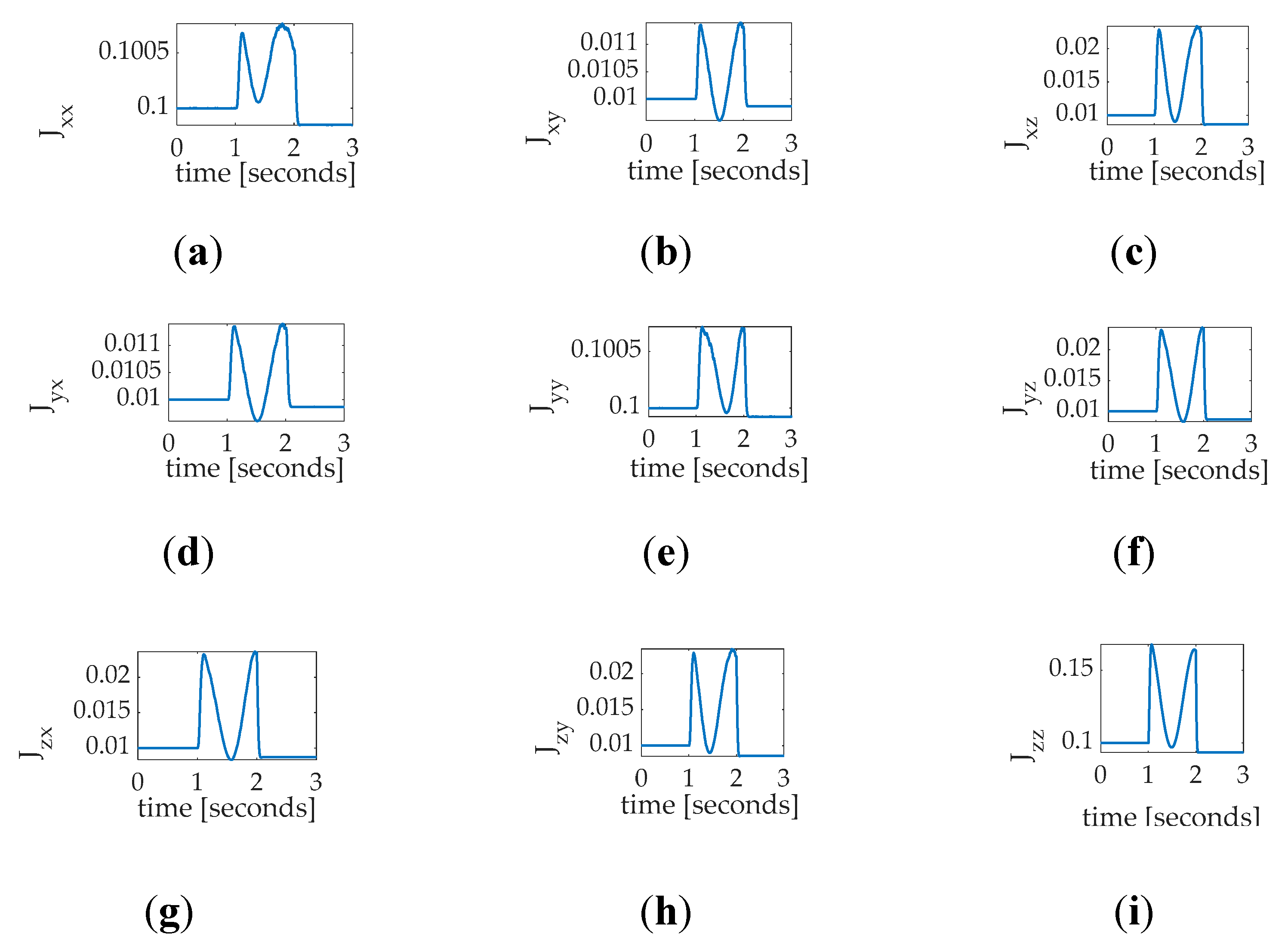

3.4. Location of Mass Center

Time varying estimates of mass moments and products may be used with equation (12) to directly calculate the location of the mass center (as a reminder that the inertia matrix must not be diagonalized). The estimates of inertia moments and products are produced with two disparate methods: nonlinear adaption, and nonlinear projection–based regression learning respectively in sections 3.4.1. and 3.4.2.

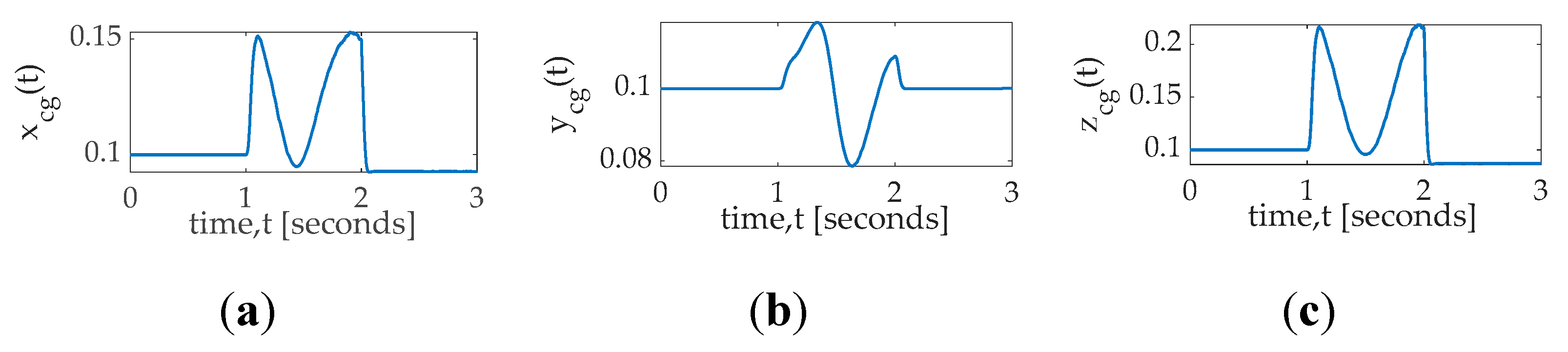

3.4.1. Identification of Mass Center Coordinates by Nonlinear Adaption

Notice in

Figure 22 adaption occurs twice: at the beginning and the end of trajectory tracking. The roll channel depicted in subfigure (a) seems to indicate a proper mass center location roughly at 0.15 in the

direction. Meanwhile, the pitch channel adaption deviates from 0.1

in the

direction, while the yaw channel location adaption displayed in subfigure (c) behaves similar to the roll channel, seemingly indicating a mass center location roughly 0.225 in the

direction. Lastly, notice during the post–maneuver quiescent period, the location estimate does not return to the initial estimate (at the beginning of the pre–manuever quiescent period. As a reminder the control signal contains a sinusoidal trajectory command (which is persistently exciting of order 2) with white noise added (which is persistently exciting of order

).

Figure 22.

Nonlinear adaption time varying location of the center of mass: For a single, thirty–degree yaw maneuver with coupled motion in roll and pitch, where the command has white noise added to aid persistent excitation (a) coordinate; (b) coordinate; (c) coordinate. Notice the initial flat–line behavior during the initial quiescent period is followed by rapid location learning during the maneuver excitement, lastly followed by a slow, oscillatory settling following the maneuver during regulation. The location seems to approach the body axes origin in the and directions with slight movement away in direction. (d) three–dimensional plot of learned cg location using projection regression–based learning; (e) three–dimensional plot of learned cg location using nonlinear adaption for inertia calculations. Both (d) and (e) use identical deterministic relationships to locate the center of mass using the products of inertia.

Figure 22.

Nonlinear adaption time varying location of the center of mass: For a single, thirty–degree yaw maneuver with coupled motion in roll and pitch, where the command has white noise added to aid persistent excitation (a) coordinate; (b) coordinate; (c) coordinate. Notice the initial flat–line behavior during the initial quiescent period is followed by rapid location learning during the maneuver excitement, lastly followed by a slow, oscillatory settling following the maneuver during regulation. The location seems to approach the body axes origin in the and directions with slight movement away in direction. (d) three–dimensional plot of learned cg location using projection regression–based learning; (e) three–dimensional plot of learned cg location using nonlinear adaption for inertia calculations. Both (d) and (e) use identical deterministic relationships to locate the center of mass using the products of inertia.

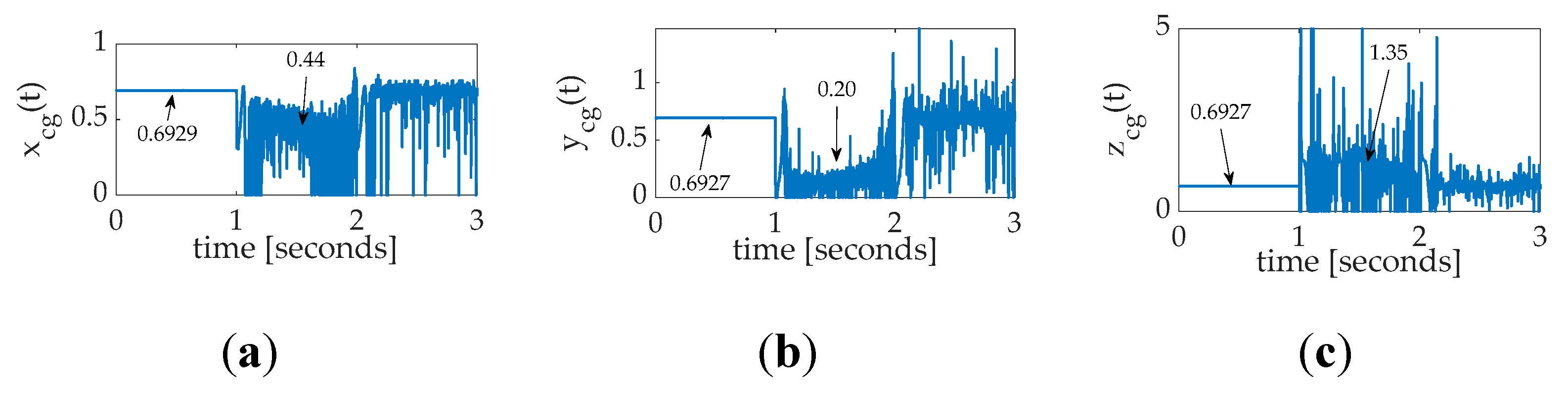

3.4.2. Identification of Mass Center Coordinates by Nonlinear Projection–Based Regression Learning

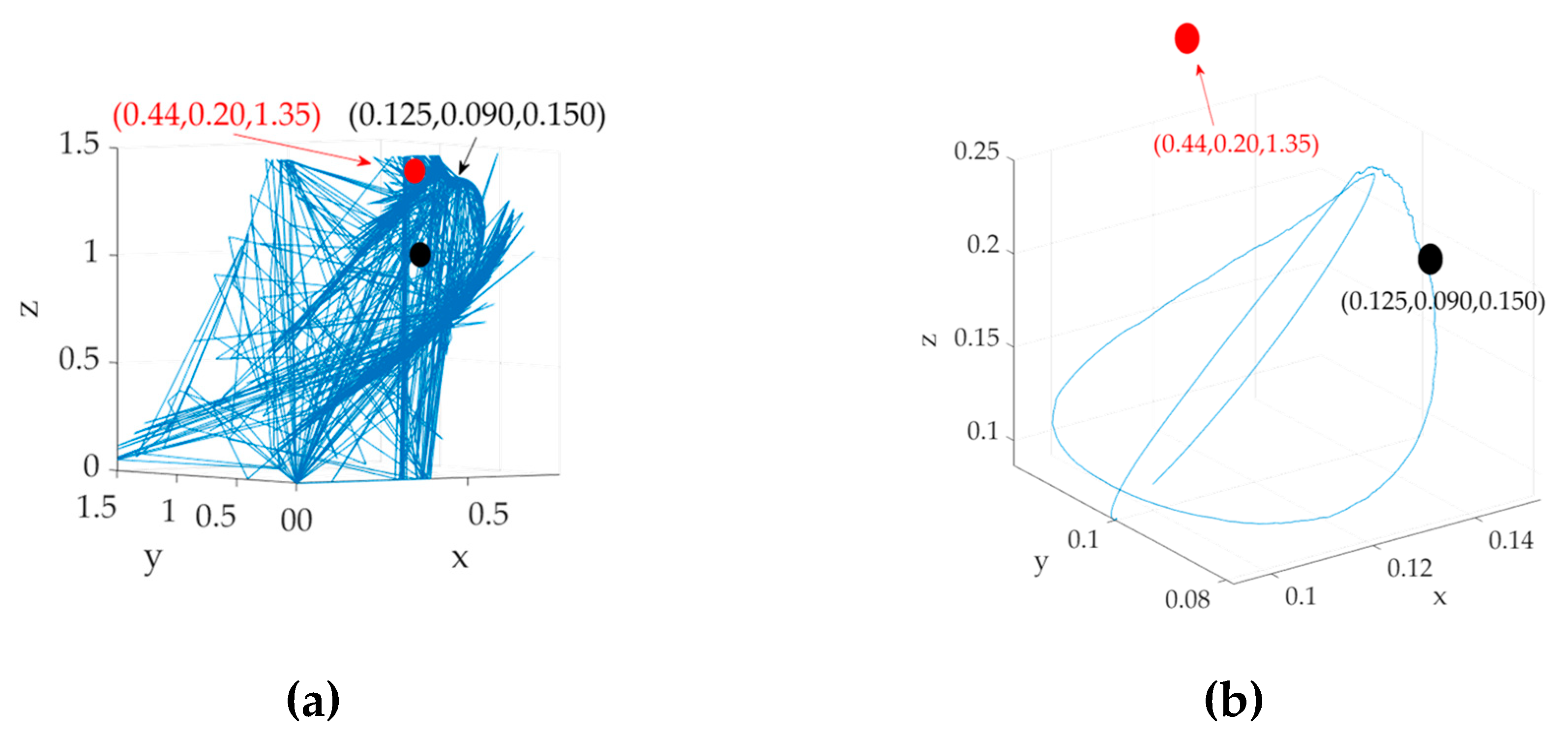

Notice in

Figure 23 adaption occurs many more times than twice. Especially focusing on the period between the beginning and the end of trajectory tracking, the roll channel depicted in subfigure (a) seems to indicate a proper mass center location roughly at 0.44 in the

direction. Meanwhile, the pitch channel adaption deviates from 0.20 in the

direction, while the yaw channel location adaption displayed in subfigure (c) seemingly indicating a mass center location roughly 1.35 in the

direction. Again, notice during the post–maneuver quiescent period, the location estimate does not return to the initial estimate (at the beginning of the pre–manuever quiescent period. As a reminder the control signal contains a sinusoidal trajectory command (which is persistently exciting of order 2) with white noise added (which is persistently exciting of order

).

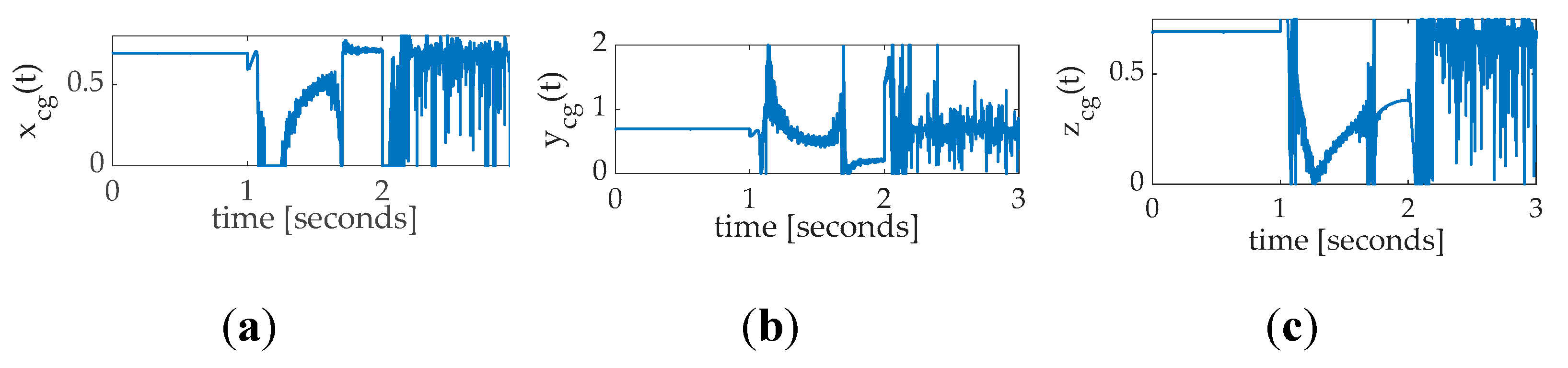

Figure 23.

Projection regression–based learning time varying location of the center of mass: Three–dimensional coordinate estimates (a) , (b) , and (c) ; for a single, thirty–degree yaw maneuver with coupled motion in roll and pitch, where the command has white noise added to aid persistent excitation. Notice the initial flat–line behavior during the initial quiescent period is followed by rapid location learning during the maneuver excitement. Furthermore notice the degree of convergence spans roughly 253, 493, and 657 millimeters in each axis respectively in mere seconds.

Figure 23.

Projection regression–based learning time varying location of the center of mass: Three–dimensional coordinate estimates (a) , (b) , and (c) ; for a single, thirty–degree yaw maneuver with coupled motion in roll and pitch, where the command has white noise added to aid persistent excitation. Notice the initial flat–line behavior during the initial quiescent period is followed by rapid location learning during the maneuver excitement. Furthermore notice the degree of convergence spans roughly 253, 493, and 657 millimeters in each axis respectively in mere seconds.

Box 5. Mass center recommendation.

Locating the mass center: Compared to using nonlinear adaption, use of nonlinear projection–based regression learning was more sensitive to identical cases of persistent excitation and accordingly produced better location of mass center.

3.4.3. Location of Center of Mass: Three–Dimensional Comparison

Both methods of inertia matrix components identification (adaption and learning) were implemented and compared in

Figure 24. Immediately evident upon first glance is the fact the adaptive approach converges relatively slowly compared to projection regression two norm optimal learning. During developing the learning approach in section 2 of this manuscript, the notion of having optimal estimates at every time step seemed attractive, but clearly has drawbacks illustrated in

Figure 23a and

Figure 24 compared to the nonlinear adaptive approach whose results are displayed in

Figure 23b and

Figure 22. The two–norm optimal pseudoinverse calculation in the learning approach seems to be highly excited by the presence of so many perturbations (indicating potentially poor applicability to deployed space robotic systems.

Figure 24.

Comparison, time varying location of the center of mass: (a) three–dimensional plot of learned cg location using projection regression–based learning; (b) three–dimensional plot of learned cg location using nonlinear adaption for inertia calculations. Both (a) and (b) use identical deterministic relationships to locate the center of mass using the products of inertia.

Figure 24.

Comparison, time varying location of the center of mass: (a) three–dimensional plot of learned cg location using projection regression–based learning; (b) three–dimensional plot of learned cg location using nonlinear adaption for inertia calculations. Both (a) and (b) use identical deterministic relationships to locate the center of mass using the products of inertia.

3.4. Compound Maneuvers

Figure 25.

Compound maneuver trajectory tracking errors. Projection regression–based learning with nonlinear Luenberger observers. (a) roll; (b) pitch; (c) yaw.

Figure 25.

Compound maneuver trajectory tracking errors. Projection regression–based learning with nonlinear Luenberger observers. (a) roll; (b) pitch; (c) yaw.

Table 15.

Compound maneuver trajectory tracking errors. Projection regression–based learning with nonlinear Luenberger observers.

Table 15.

Compound maneuver trajectory tracking errors. Projection regression–based learning with nonlinear Luenberger observers.

| |

Roll

[degrees] |

Pitch

[degrees] |

Yaw

[degrees] |

| Error mean |

0.00028129 |

|

0.0027575 |

| Error standard deviations 1

|

0.0084356 |

0.0054244 |

0.011515 |

Figure 26.

Compound maneuver estimated mass center location. Projection regression–based learning with nonlinear Luenberger observers. (a) -coordinate; (b) -coordinate; (c) -coordinate.

Figure 26.

Compound maneuver estimated mass center location. Projection regression–based learning with nonlinear Luenberger observers. (a) -coordinate; (b) -coordinate; (c) -coordinate.

Box 6. Compound maneuver recommendation.

Single axis versus compound axis maneuvers: Compound maneuvers eliminated learning convergence experienced with single–axis maneuvers. Single axis maneuvers should be sequenced sequentially amongst all three axes.

3.5. Summary of Results

Results displayed through the manuscript are consolidated in this section and presented as percent performance difference relative to a comparative benchmark. Narrative results are subsequently discussed in

Section 4 Discussion aiming to highlight substantial results in plain verbiage (e.g. no use of “microradian”, etc.) in favor of percent performance difference. Superlative results are highlighted in bold font to amplify information transmission when readers scan the manuscript.

Table 16.

Attitude control trajectory tracking percent performance difference.

Table 16.

Attitude control trajectory tracking percent performance difference.

| Maneuver case |

Roll errors |

Pitch errors |

Yaw errors |

| |

Mean |

Deviation |

Mean |

Deviation |

Mean |

Deviation |

| Unperturbed PID unperturbed system* |

3% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

899% |

0% |

| Benchmark case ** |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

| Feedforward + feedback + adaption*** or learning **** |

-68% |

-51% |

-50% |

-49% |

-49% |

-50% |

Table 17.

Observer estimation percent performance comparison. Highly perturbed (uniformly varied inertia, sensors with white noise) thirty–degree yaw maneuver tracking errors.

Table 17.

Observer estimation percent performance comparison. Highly perturbed (uniformly varied inertia, sensors with white noise) thirty–degree yaw maneuver tracking errors.

| |

Mean roll

[degrees] |

Mean pitch

[degrees] |

Mean yaw

[degrees] |

| Benchmark Luenberger |

|

|

|

| Nonlinear Luenberger 1

|

77% |

144.58% |

-1.02% |

Table 18.

Performance comparison of controlling highly perturbed system (uniformly varied inertia, sensors with white noise) 1 unless otherwise stated for a thirty–degree yaw maneuver.

Table 18.

Performance comparison of controlling highly perturbed system (uniformly varied inertia, sensors with white noise) 1 unless otherwise stated for a thirty–degree yaw maneuver.

| Case |

Cost |

| PID controlled unperturbed system |

-1% |

| Benchmark PID feedback |

-- |

| Nonlinear feedforward with inertia adaption, and PID feedback |

-10% |

| Nonlinear feedforward with regression–based inertia learning |

-10% |

Table 19.

Locating center of mass performance comparison. ****,†.

Table 19.

Locating center of mass performance comparison. ****,†.

| Maneuver case |

x coordinate |

y coordinate |

z coordinate |

| Nonlinear adaption |

7% |

0% |

13% |

| Nonlinear projection–based regression learning |

36% |

71% |

-95% |

|

4. Discussion

Nonlinear adaptive methods for locating the mass center proved effective, but less so than nonlinear projection–based regression learning. Using identical excitation, nonlinear adaptive methods were able to establish an average seven percent difference in coordinates of the mass center, while an average over seventy percent difference was achievable using nonlinear projection–based regression learning. Listed in

Table 20, several recommendations are advised to repeat these results.

Table 20.

Most significant recommendations.

Table 20.

Most significant recommendations.

Use the physics–based governing dynamics to embody the control (section 2.1) To maximize persistent excitation, autonomous sinusoidal trajectories are recommended with white noise added. (section 2.9) Simultaneous use of both Luenberger styles is recommended to leverage their relative strengths in the maneuver–axis and non–maneuver axis. (section 3.2) Compared to using nonlinear adaption, use of nonlinear projection–based regression learning was more sensitive to identical cases of persistent excitation and accordingly produced better location of mass center. (section 3.4.2) Compound maneuvers eliminated learning convergence experienced with single–axis maneuvers. Single axis maneuvers should be sequenced sequentially amongst all three axes. (section 3.4.3) |

4.1. Future Research Directions

While this prequel study introduces the first two steps of investigation (analysis and verification in simulations), validation with spaceflight experiments is planned for March 2025, after which a sequel will be published with the results of the spaceflight tests.

4. Conclusion

Arguably, reference [

22] presents the best recently proposed comparative benchmark, since that method was experimentally validated on the GRACE-C satellite. The method effectively generated convergent estimates of mass center coordinates, where the convergence spanned just greater than 0.3 millimeters over several hundred days. Meanwhile convergence using the proposed methods (in simulations) span roughly 200–600 millimeters respectively in each axis, and convergence occurs in mere seconds assuming a single–axis slew maneuver. Multi–axis, compound slew maneuvers were completely ineffective using the proposed approach to estimate coordinates of the center of mass. Succinctly, the proposed methods seem to indicate advantages of speed and quantity of coordinate convergence when compared to the state–of–the–art comparative benchmark. Spaceflight experiments planned for March 2025 will evaluate the efficacy of this proposed approach empirically.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, T.S.; methodology, T.S.; software, T.S.; validation, T.S.; formal analysis, T.S.; investigation, T.S.; resources, T.S.; data curation, T.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.S.; writing—review and editing, T.S.; visualization, T.S.; supervision, T.S.; project administration, T.S.; funding acquisition, T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the corresponding author.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The nonlinear feedforward is developed step–by–step in this appendix.

Appendix B

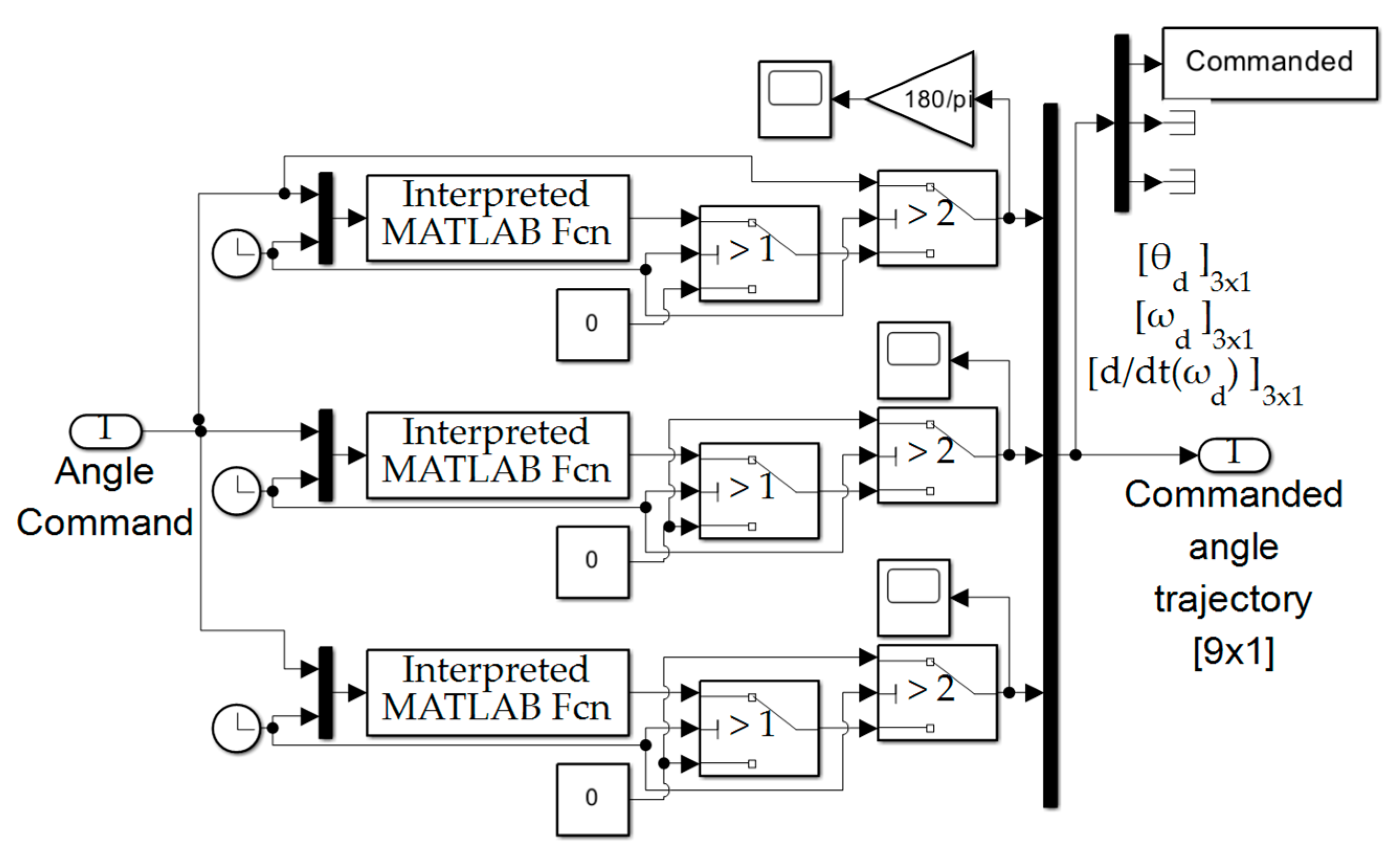

This appendix displays all the simulation subsystems permitting repeatability by the readership using MATLAB®/SIMULINK®. Implementation steps follow:

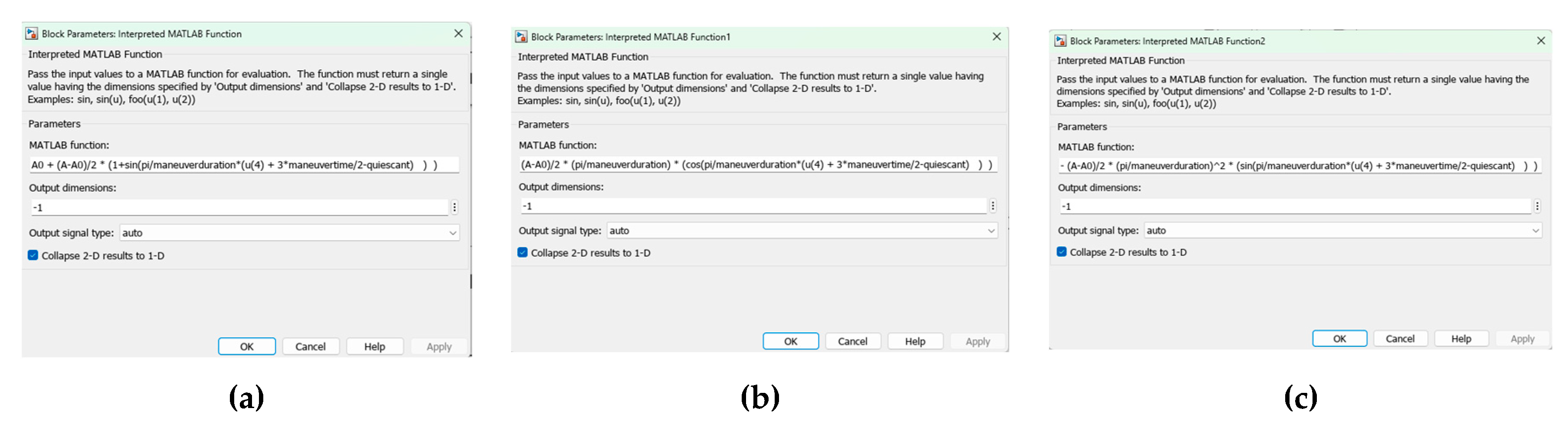

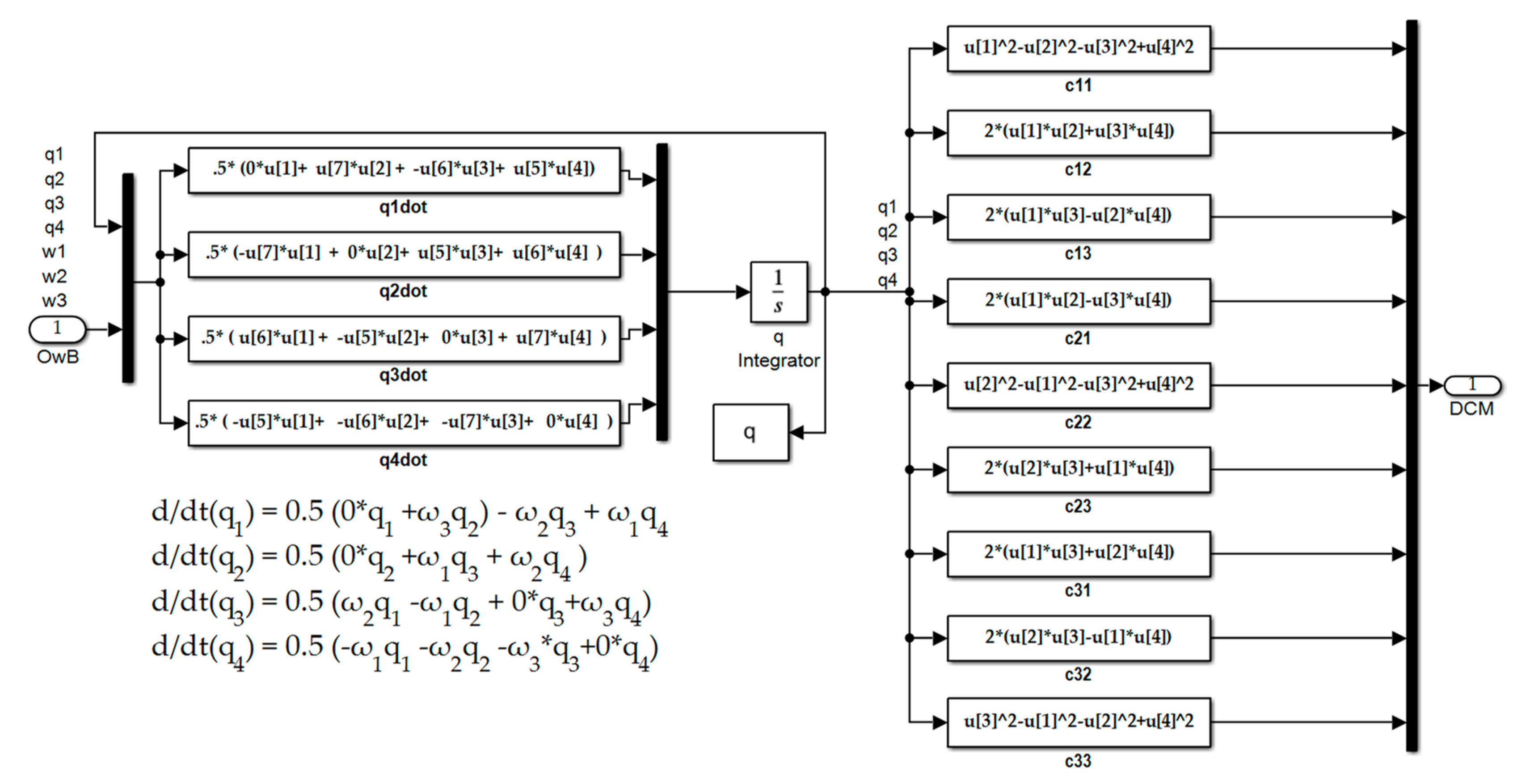

Create a scheme of command. A sinusoidal scheme is depicted in Figure B.27 and may be constructed by dragging and dropping the blocks depicted from the library to the simulation. The switching logic produces smooth sinusoids for angular displacement, velocity, and acceleration. The switch institutes to regulation at the final commanded value smoothly exiting the sinusoidal curves respectively. The syntax for the sinusoidal commands is displayed in Figure B.28

The attitude controllers are displayed in Figure B.29 including both feedforward and feedback controllers. The project–based learning algorithm is also included. Additionally, notice there is a manual switch away from the input sinusoidal trajectories and optionally towards a simple step command. Lastly, notice artificially faked inertia values and random perturbations are included as switchable options as well.

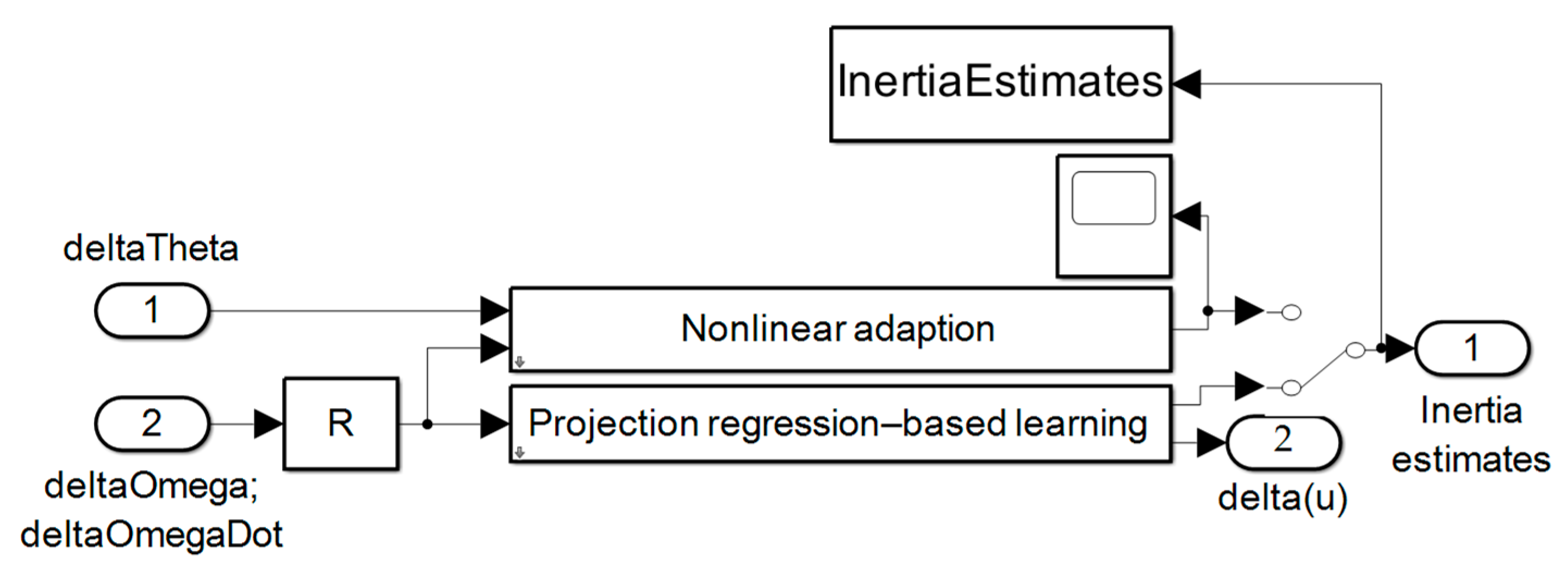

Projection–based learning and/or nonlinear adaption feedback is displayed in Figure B.30, Figure B.31, and Figure B.32,

The implementation steps elaborated so far in

Appendix B yield an ability to produce endpoint commands, autonomous trajectory generation, and trajectory tracking abilities, where the outputs include the control torque (to be sent to the space robot). Additional outputs include time–varying inertia estimates and location of the center of mass. The control signal is routed the actuator on the space robot.

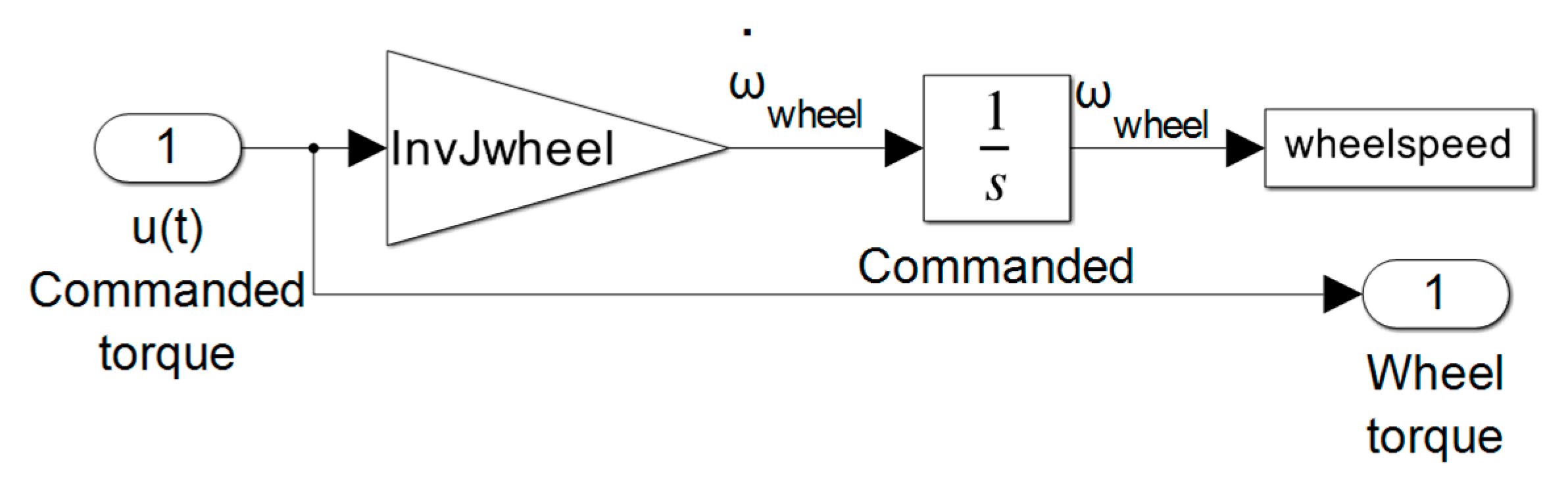

- 4.

The reaction wheel actuator is displayed in Figure B.35, where the output torque from the actuator is routed to the governing equations of motion depicted in Figure B.36 with expanded drilldown elaboration in Figure B.37 and Figure B.38. The governing equations of motion produce angular velocities relative to the inertial reference frame but need to be expressed in the coordinates of a body frame of interest.

- 5.

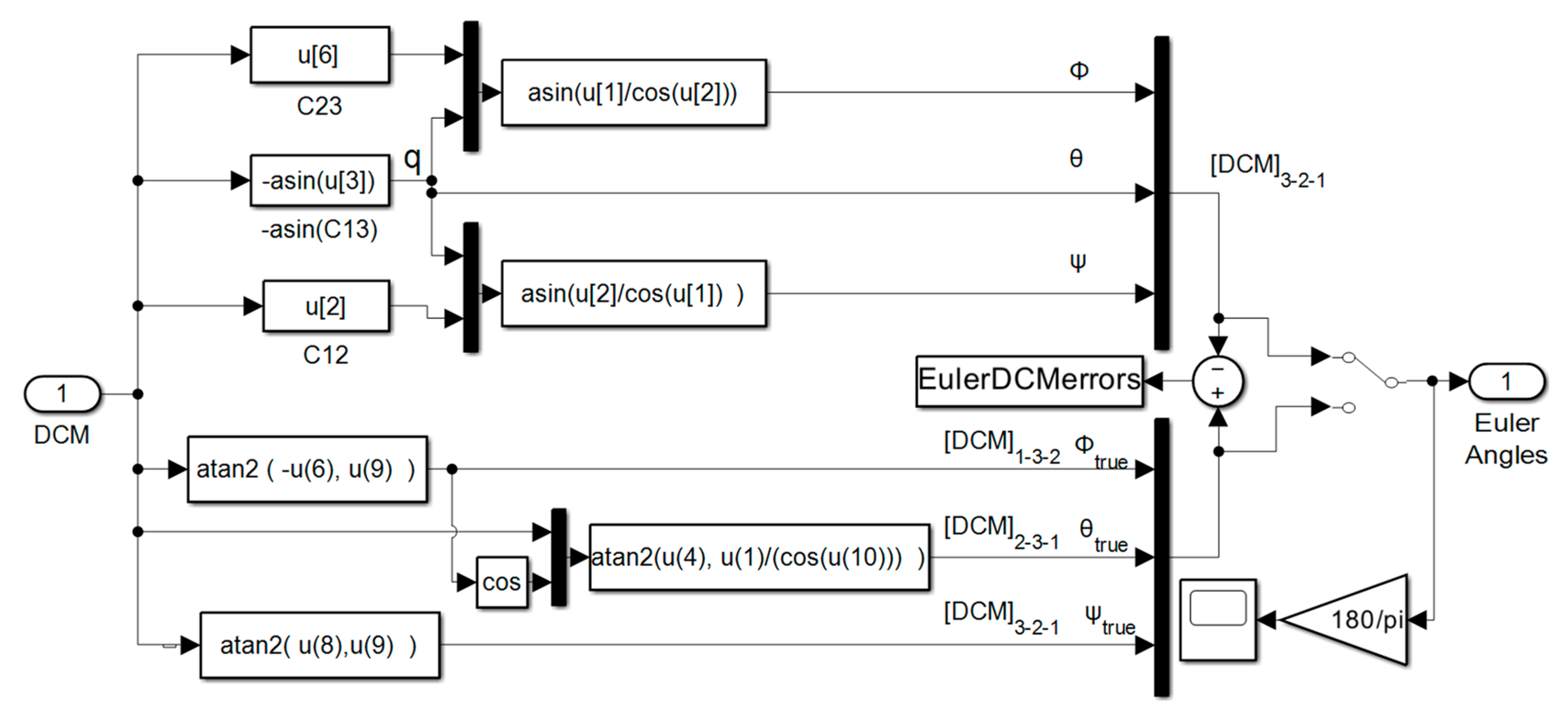

Figure B.38 displays the high–level kinematics topology. Drill downs for quaternions is displayed in Figure B.39 where the quaternions are used to construct a nine–element direction cosine matrix transformation between inertial and body coordinates. The direction cosine matrix is used to extract Euler angles where a 321 rotation sequence is assumed, and that code is depicted in Figure B.40.

- 6.

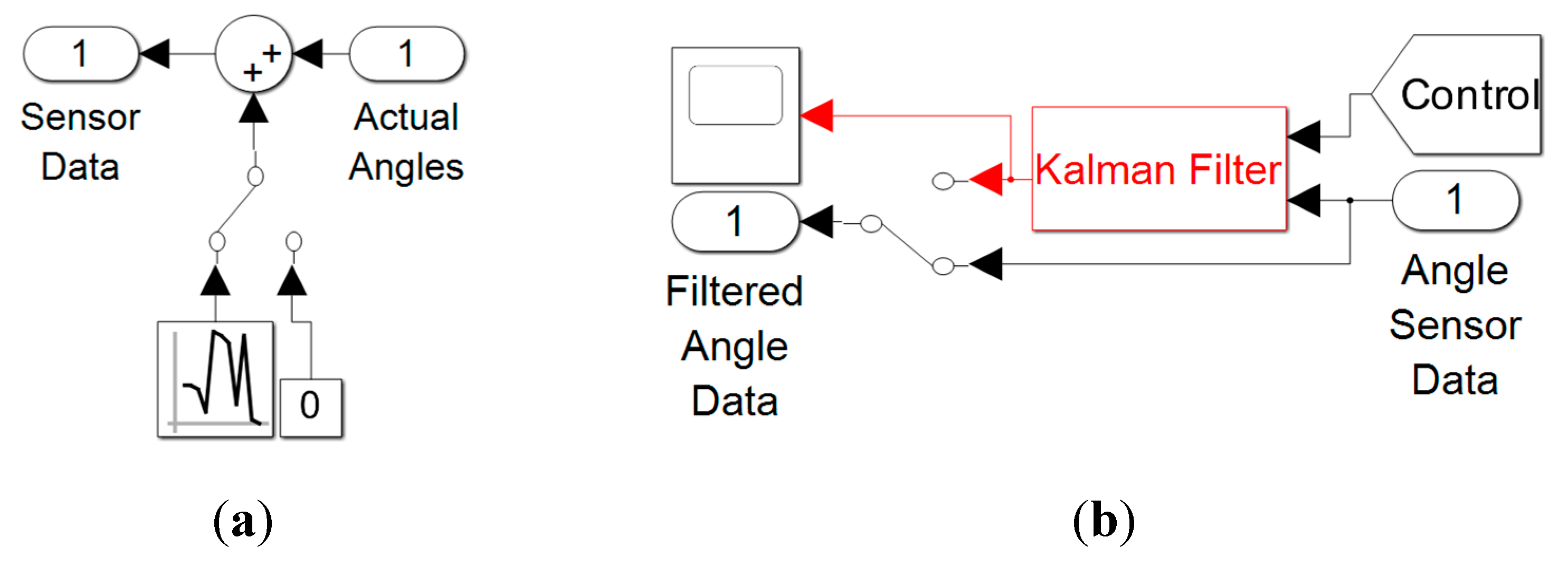

While the true Euler angles cannot be known by the robot operators, sensors are simulated with additive noise and filters designed to counteract the noise in Figure B.41.

- 7.

The direction cosine matrix conveniently reveals the vector locations of the body axes and is used to calculated environmental disturbance torques.

The implementation steps elaborated so far in

Appendix B now additionally include kinetics, kinematics, noisy sensors and filters. Lastly, the simulation of environmental disturbances is elaborated.

- 8.

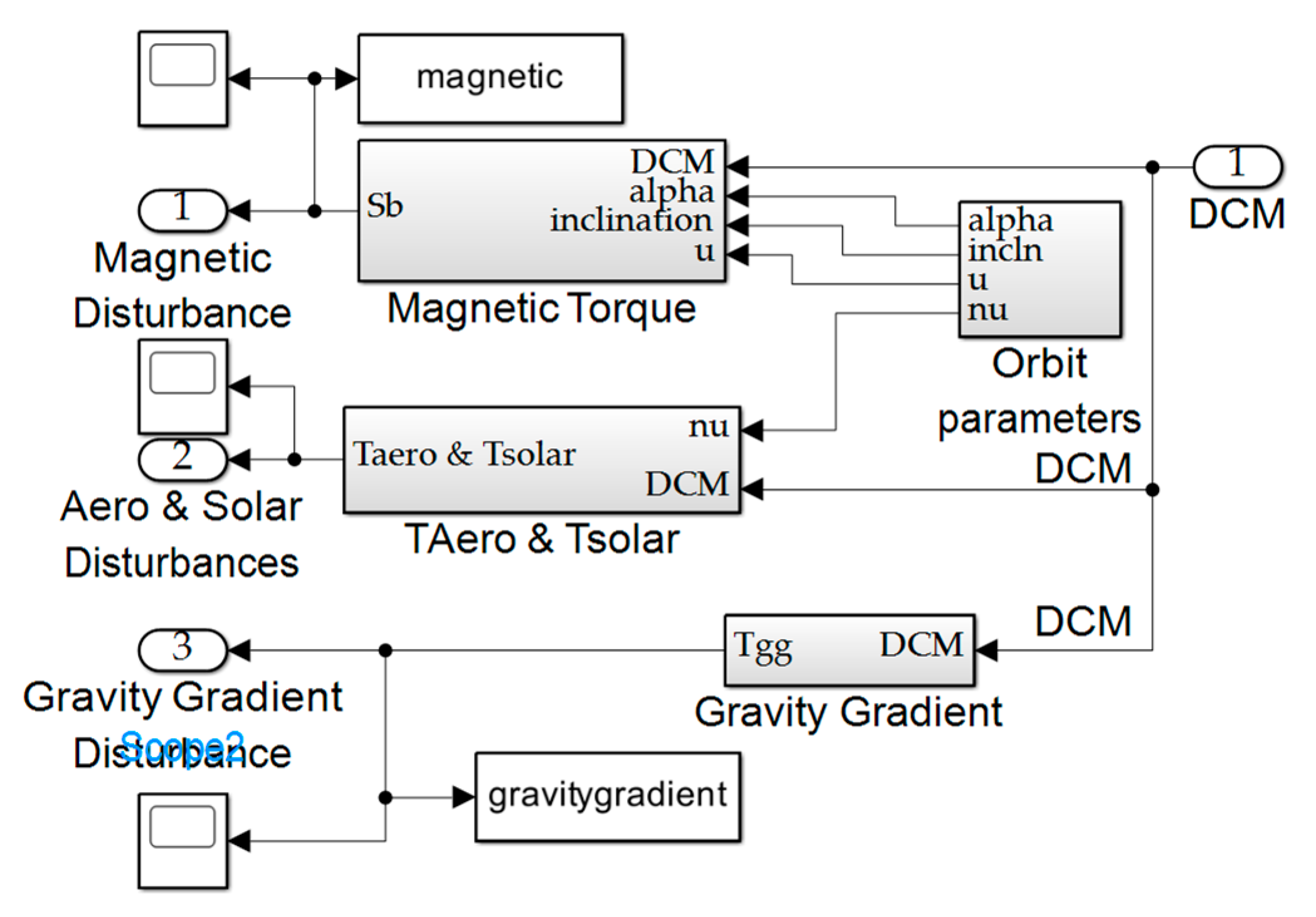

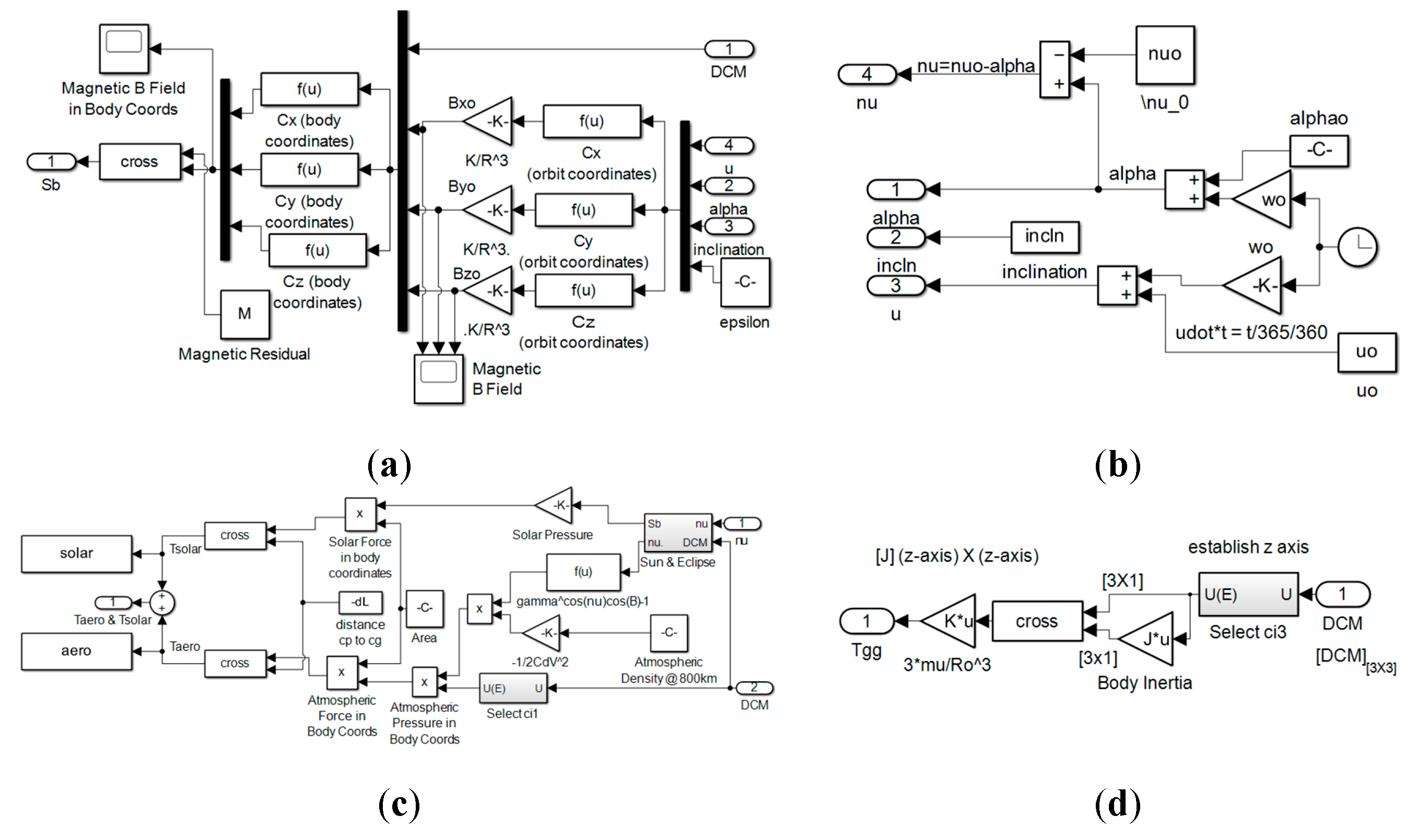

The top–level topology of environmental disturbances is displayed in Figure B.42 where each subsystem is individually displayed in Figure B.43 for atmospheric, magnetic, solar radiation, and gravity gradient disturbances.

Figure B.27.

Internal content of trajectory generation subsystem depicted in

Figure 3. Notice the sinusoidal attitude trajectories are formulated from the single input of angle commanded outside the space robot (presumably either autonomously by the demands of the translational motion subsystem or alternatively externally supplied by a human operator aiding the space robot’s motion with remote-controls.

Figure B.27.

Internal content of trajectory generation subsystem depicted in

Figure 3. Notice the sinusoidal attitude trajectories are formulated from the single input of angle commanded outside the space robot (presumably either autonomously by the demands of the translational motion subsystem or alternatively externally supplied by a human operator aiding the space robot’s motion with remote-controls.

Figure B.28.