Submitted:

15 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

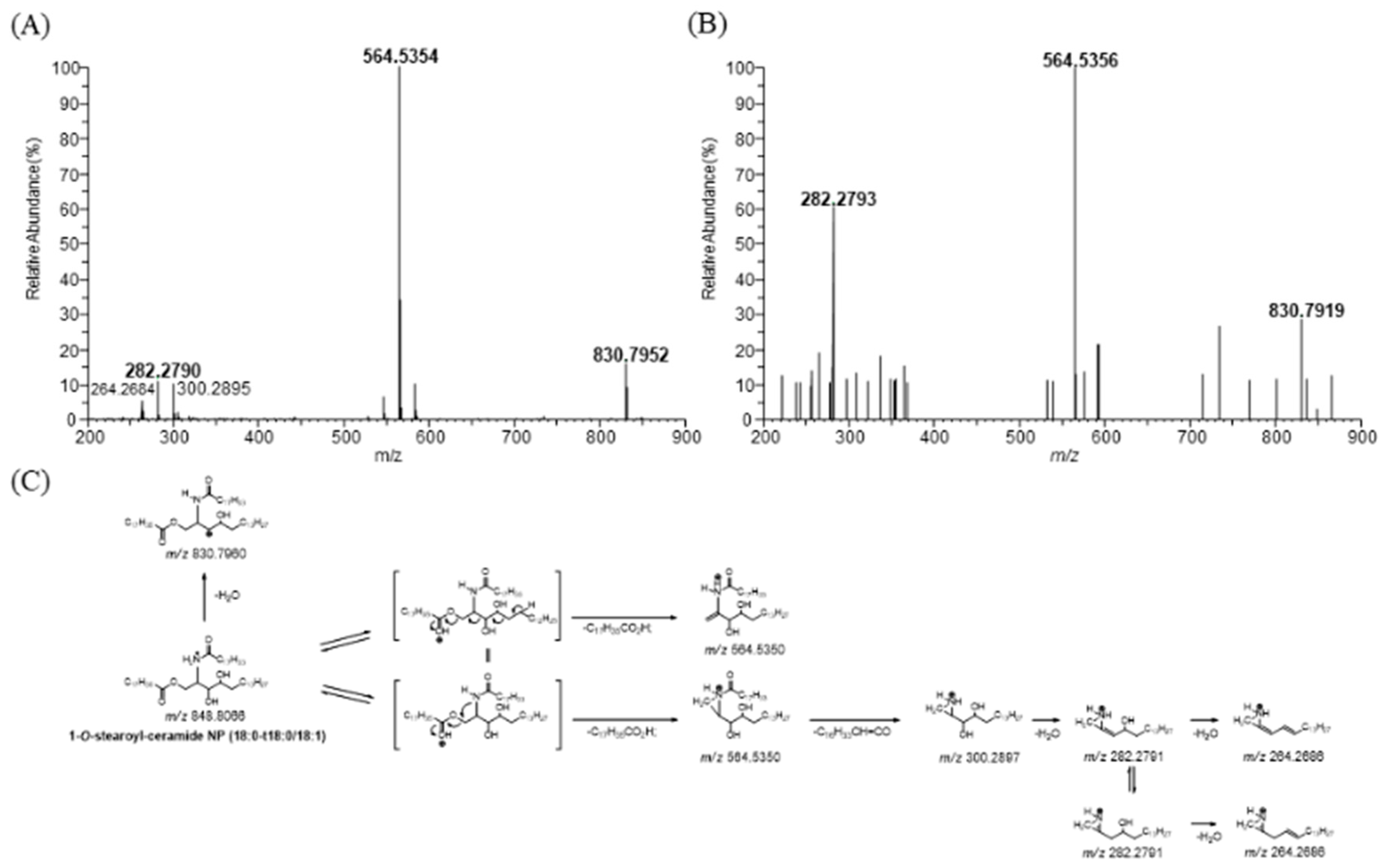

2.1. Identification of 1-O-Stearoyl-Ceramide NP (18:0-t18:1/18:0) in Human Stratum Corneum

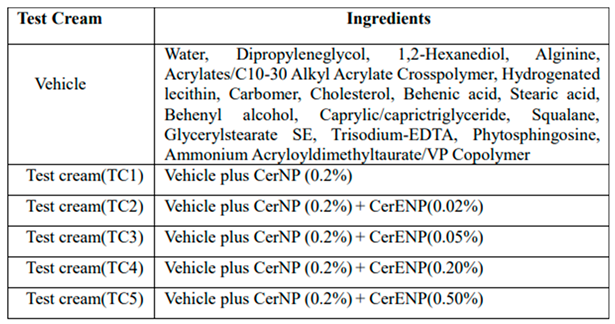

2.2. Ceramides and Test Creams

2.3. Human Study

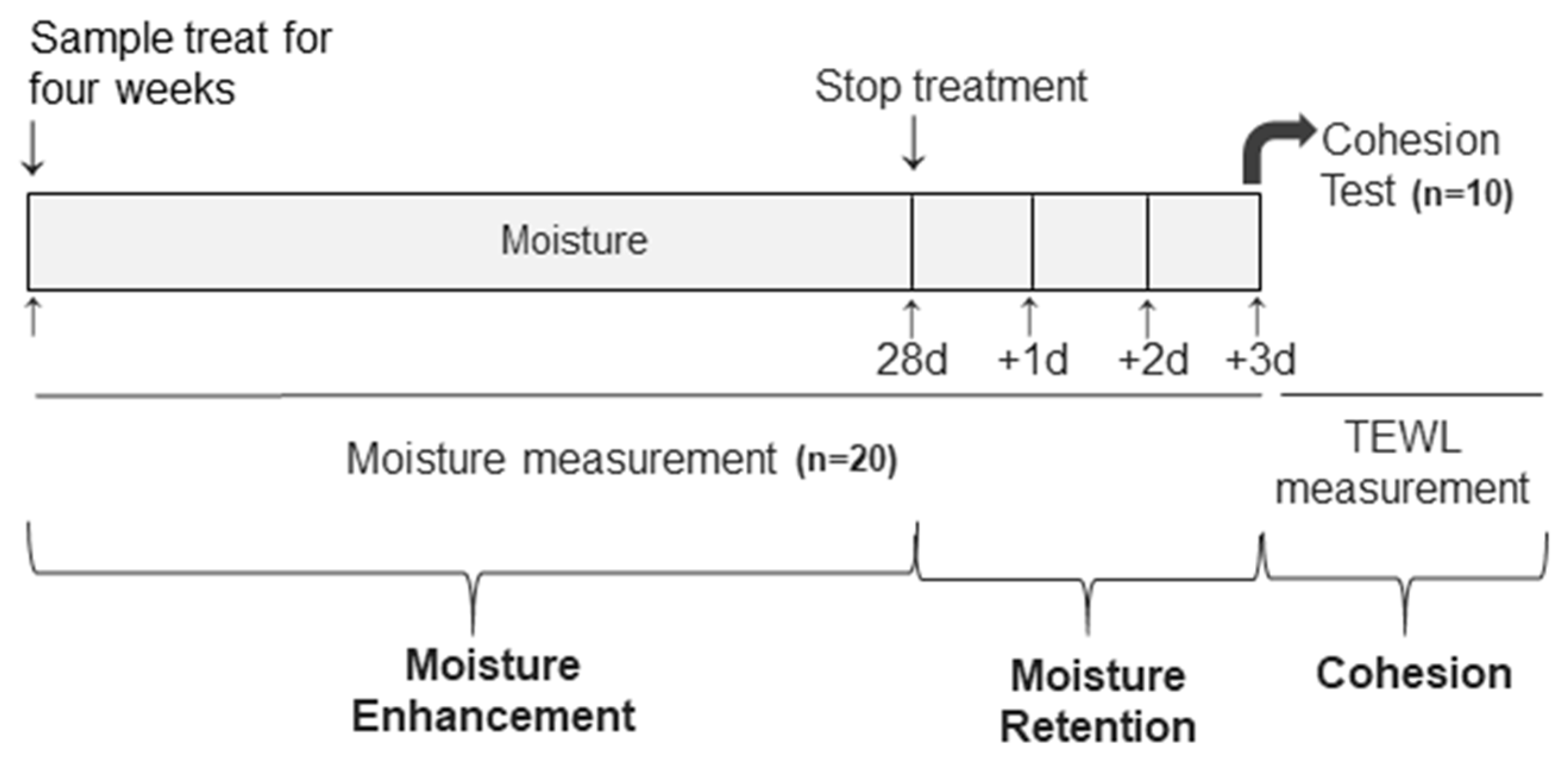

2.4. Measurement of Skin Hydration, Retention of Hydration, and SC Cohesion

- The assessment of SC hydration

- The SC cohesion

2.5. Microscopic Observations of Maltese Cross Appearance

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identification of 1-O-Stearoyl-Ceramide NP (18:0-t18:0/18:1) in Human Stratum Corneum

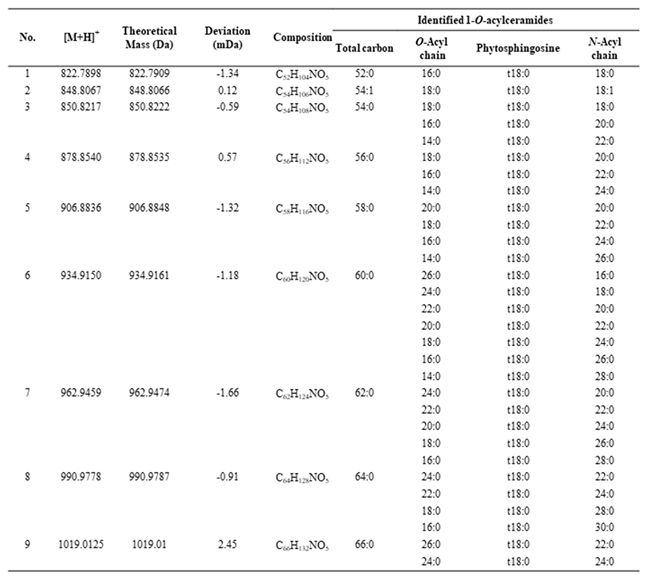

3.2. Profiling of 1-O-Acylceramide NP (CER 1-O-ENP) in Human Stratum Corneum

3.3. Effect of CER 1-O-ENP on Multilamellar Formation and Its Stability

3.3. The Influence of CER 1-O-ENP on the Skin Hydration

3.4. CER 1-O-ENP Fostered the SC Cohesion

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lampe, M.A.; Burlingame, A.L.; Whitney, J.; Williams, M.L.; Brown, B.E.; Roitman, E.; Elias, P.M. Human stratum corneum lipids: characterization and regional variations. J Lipid Res. 1983 24(2),120-30. ( PMID: 6833889). [CrossRef]

- Imokawa, G.; Abe, A.; Jin, K.; Higaki, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Hidano, A. Decreased level of ceramides in stratum corneum of atopic dermatitis: an etiologic factor in atopic dry skin? Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1991 96(4), 523-6. (PMID: 2007790). [CrossRef]

- Bouwstra, J.A.; Ponec, M. The skin barrier in healthy and diseased state. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2006 1758(12), 2080-95. (PMID: 16945325). [CrossRef]

- van Smeden, J.; Janssens, M.; Gooris, G.S.; Bouwstra, J.A. The important role of stratum corneum lipids for the cutaneous barrier function. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2014 1841(3), 295-313. (PMID: 24252189). [CrossRef]

- van Smeden, J.; Hoppel, L.; van der Heijden, R.; Hankemeier, T.; Vreeken, R.J.; Bouwstra, J.A. LC/MS analysis of stratum corneum lipids: ceramide profiling and discovery. Journal of Lipid Research. 2011 52(6), 1211-21. (PMID: 21444759). [CrossRef]

- Zettersten, E.M.; Ghadially, R.; Feingold, K.R.; Crumrine, D.; Elias, P.M. Optimal ratios of topical stratum corneum lipids improve barrier recovery in chronologically aged skin. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1997 37(3 Pt 1), 403-8. (PMID: 9308554). [CrossRef]

- Kircik, L.H. Effect of skin barrier emulsion cream vs a conventional moisturizer on transepidermal water loss and corneometry in atopic dermatitis: a pilot study. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2014 13(12), 1482-4. (PMID: 25607793).

- Danby, S.G.; Andrew, P.V.; Brown, K.; Chittock, J.; Kay, L.J.; Cork, M.J. An Investigation of the Skin Barrier Restoring Effects of a Cream and Lotion Containing Ceramides in a Multi-vesicular Emulsion in People with Dry, Eczema-Prone, Skin: The RESTORE Study Phase 1. Dermatology and Therapy. 2020 10(5), 1031-1041. (PMID: 34657996). [CrossRef]

- Masukawa, Y.; Narita, H.; Sato, H.; Naoe, A.; Kondo, N.; Sugai, Y.; Oba, T.; Homma, R.; Ishikawa, J.; Takagi, Y.; Kitahara, K. Comprehensive quantification of ceramide species in human stratum corneum. Journal of Lipid Research. 2009 50(8), 1708-19. (PMID: 19349641). [CrossRef]

- Masukawa, Y.; Narita, H.; Shimizu, E.; Kondo, N.; Sugai, Y.; Oba, T.; Homma, R.; Ishikawa, J.; Takagi, Y.; Kitahara, T.; Takema, Y.; Kita, K. Characterization of overall ceramide species in human stratum corneum. Journal of Lipid Research. 2008 49(7), 1466-76. (PMID: 18359959). [CrossRef]

- van Smeden, J.; Boiten, W.A.; Hankemeier, T.; Rissmann, R.; Bouwstra, J.A.; Vreeken, R.J. Combined LC/MS-platform for analysis of all major stratum corneum lipids, and the profiling of skin substitutes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2014, 1841, 70–79 (PMID: 24120918). [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Ohno, Y.; Kihara, A. Whole picture of human stratum corneum ceramides, including the chain-length diversity of long-chain bases. J Lipid Res. 2022 Jul 63(7), 100235. (PMID: 35654151). [CrossRef]

- Janssens, M.; van Smeden, J.; Gooris, G.S.; Bras, W.; Portale, G.; Caspers, P.J.; Vreeken, R.J.; Hankemeier, T.; Kezic, S.; Wolterbeek, R.; Lavrijsen, A.P.; Bouwstra, J.A. Increase in short-chain ceramides correlates with an altered lipid organization and decreased barrier function in atopic eczema patients. Journal of Lipid Research. 2012 53(12), 2755-66. (PMID: 23024286). [CrossRef]

- Oguri, M.; Gooris, G.S.; Bito, K.; Bouwstra, J.A. The effect of the chain length distribution of free fatty acids on the mixing properties of stratum corneum model membranes. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2014 1838(7), 1851-61. (PMID: 24565794). [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.C.; Hartkamp, R.; Iacovella, C.R.; Bunge, A.L.; McCabe, C. Effect of Ceramide Tail Length on the Structure of Model Stratum Corneum Lipid Bilayers. Biophysical journal. 2018 114(1), 113-125. (PMID: 29320678). [CrossRef]

- Pullmannová, P.; Pavlíková, L.; Kováčik, A., Sochorová M, Školová B, Slepička P, Maixner J, Zbytovská J, Vávrová K.. Permeability and microstructure of model stratum corneum lipid membranes containing ceramides with long (C16) and very long (C24) acyl chains. Biophysical chemistry. 2017 224, 20-31. (PMID: 28363088). [CrossRef]

- Uche, L.E.; Gooris, G.S.; Bouwstra, J.A.; Beddoes, C.M. Increased Levels of Short-Chain Ceramides Modify the Lipid Organization and Reduce the Lipid Barrier of Skin Model Membranes. Langmuir : the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids. 2021 37(31), 9478-9489. (PMID: 34319754). [CrossRef]

- Mann, M-Q.; Brown, B.E.; Wu-Pong, S.; Feingold, K.R.; Elias, P.M. Exogenous nonphysiologic vs physiologic lipids. Divergent mechanisms for correction of permeability barrier dysfunction. Archives of dermatology. 1995 131(7), 809-16. (PMID: 7611797). [CrossRef]

- Kono, T.; Miyachi, Y.; Kawashima, M. Clinical significance of the water retention and barrier function-improving capabilities of ceramide-containing formulations: A qualitative review. J Dermatol. 2021 8(12), 1807-1816. Epub 2021 Oct 1. (PMID: 34596254). [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, A.V.; Lane, M.E. Letter to the Editor Regarding 'An Investigation of the Skin Barrier Restoring Effects of a Cream and Lotion Containing Ceramides in a Multi-Vesicular Emulsion in People with Dry, Eczema-Prone Skin: The RESTORE Study Phase 1'. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021 11(6), 2245-2248. Epub 2021 Oct 17. (PMID: 34657996). [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, A.V.; Lane, M.E. Comment on "Clinical significance of the water retention and barrier function-improving capabilities of ceramide-containing formulations: A qualitative review". J Dermatol. 2022 49(3), e121-e123. Epub 2021 Dec 3. ( PMID: 34862644 ). [CrossRef]

- van Smeden, J.; Bouwstra, J.A. Stratum Corneum Lipids: Their Role for the Skin Barrier Function in Healthy Subjects and Atopic Dermatitis Patients. Current Problems in Dermatology. 2016 49, 8-26. (PMID: 26844894). [CrossRef]

- Opálka, L.; Kováčik, A.; Maixner, J.; Vávrová, K. Omega-O-Acylceramides in Skin Lipid Membranes: Effects of Concentration, Sphingoid Base, and Model Complexity on Microstructure and Permeability. Langmuir: the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids. 2016 32(48), 12894-12904. (PMID: 27934529). [CrossRef]

- Nakaune-Iijima, A.; Sugishima, A.; Omura, G.; Kitaoka, H.; Tashiro, T.; Kageyama, S.; Hatta, I. Topical treatments with acylceramide dispersions restored stratum corneum lipid lamellar structures in a reconstructed human epidermis model. Chemistry and physics of lipids. 2018 215, 56-62. (PMID: 29802829). [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, T.; Lange, S.; Dobner, B.; Sonnenberger, S.; Hauß, T.; Neubert, R.H.H. Investigation of a CER[NP]- and [AP]-Based Stratum Corneum Modeling Membrane System: Using Specifically Deuterated CER Together with a Neutron Diffraction Approach. Langmuir: the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids. 2018 34(4), 1742-1749. (PMID: 28949139). [CrossRef]

- Uche, L.E.; Gooris, G.S.; Beddoes, C.M.; Bouwstra, J.A. New insight into phase behavior and permeability of skin lipid models based on sphingosine and phytosphingosine ceramides. Biochimica et biophysica acta Biomembranes. 2019 1861(7), 1317-1328. (PMID: 30991016). [CrossRef]

- Yokose, U.; Ishikawa, J.; Morokuma, Y.; Naoe, Y.; Inoue, Y.; Yasuda, Y. Tsujimura, H.; Fujimura, T.; Murase, T.; Hatamochi, A. The ceramide [NP]/[NS] ratio in the stratum corneum is a potential marker for skin properties and epidermal differentiation. BMC Dermatology. 2020 20(1), 6-. (PMID: 32867747). [CrossRef]

- Rabionet, M.; Bayerle, A.; Marsching, C.; Jennemann, R.; Gröne, H.J.; Yildiz, Y.; Wachten, D.; Shaw, W.; Shayman, J.A.; Sandhoff, R. 1-O-acylceramides are natural components of human and mouse epidermis. Journal of Lipid Research. 2013 54(12), 3312-21. (PMID: 24078707). [CrossRef]

- Lin, M-H.; Miner, J.H.; Turk, J.; Hsu, F-F. Linear ion-trap MSn with high-resolution MS reveals structural diversity of 1-O-acylceramide family in mouse epidermis. J Lipid Res. 2017 58(4), 772-782. (PMID: 28154204). [CrossRef]

- Harazim, E.; Vrkoslav, V.; Buděšínský, M.; Harazim, P.; Svoboda, M.; Plavka, R.; Bosáková, Z.; Cvačka, J. Nonhydroxylated 1- O-acylceramides in vernix caseosa, J Lipid Res. 2018 59(11), 2164-2173. (PMID: 30254076). [CrossRef]

- Assi, A.; Bakar, J.; Libong, D.; Sarkees, E.; Solgadi, A.; Baillet-Guffroy, A.; Michael-Jubeli, R.; Tfayli, A. Comprehensive characterization and simultaneous analysis of overall lipids in reconstructed human epidermis using NPLC/HR-MSn:1-O-E (EO) Cer, a new ceramide subclass. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2020 412, 777-793. (PMID: 31858168). [CrossRef]

- Rabionet, M.; Bernard, P.; Pichery, M.; Marsching, C.; Bayerle, A.; Dworski, S.; Kamani, M.A.; Chitraju, C.; Gluchowski, N.L.; Gabriel, K.R.; Asadi, A.; Ebel, P.; Hoekstra, M.; Dumas, S.; Ntambi, J.M.; Jacobsson, A.; Willecke, K.; Medin, J.A.; Jonca, N.; Sandhoff, R. Epidermal 1-O-acylceramides appear with the establishment of the water permeability barrier in mice and are produced by maturating keratinocytes Lipids. 2022 57(3), 183-195. (PMID: 35318678). [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.O.; Kim, J.W.; Liu, K.H.; Shin, K.; Nam, Y.S.; Kim, J-W.; Park, C.S. A Novel Phytosphingosine Based 1-O-Acylceramide: Synthesis, Physicochemical Characterization, and Role in the Lipid Lamellar Organization. Proceedings in 32nd IFSCC congress 2022 Poster 305.

- Park, C.S.; Lee, E.O.; Kim, J.W.; Liu, K.H.; Lee, S.; Lim, K.M. Synthesis and Characterization of a Novel Phytosphingosine-Based 1-O-Acylceramide. IFSCC Magazine. 2022 25(5), 359-362.

- Oh, M.J.; Cho, Y.H.; Cha, S.Y.; Lee, E.O.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, S.K.; Park, C.S. Novel phytoceramides containing fatty acids of diverse chain lengths are better than a single C18-ceramide N-stearoyl phytosphingosine to improve the physiological properties of human stratum corneum. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology. 2017 10, 363-371. (PMID: 28979153). [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.H.; Kim, E.J.; Lee, C.H.; Park, G.H.; Yoo, K.M.; Nam, S.J.; Shin, K-O.; Park, K.; Choi E.H. A Lipid Mixture Enriched by Ceramide NP with Fatty Acids of Diverse Chain Lengths Contributes to Restore the Skin Barrier Function Impaired by Topical Corticosteroid. Skin pharmacology and physiology. 2022 35(2), 112-123 ; (PMID: 34348350). [CrossRef]

- Park, B.D.; Youm, J.K.; Jeong, S.K.; Choi, E.H.; Ahn, S.K.; Lee, S.H. The characterization of molecular organization of multilamellar emulsions containing pseudoceramide and type III synthetic ceramide. J Invest Dermatol. 2003 121(4), 794-801. ( PMID: 14632198). [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.Y.; Lee, E.; Park, C.S.; and Nam, Y.S. Molecular Dynamics Investigation into CerENP’s Effect on the Lipid Matrix of Stratum Corneum. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 128, 5378−5386. Epub 2024 May 28. (PMID: 38805566). [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.I.; Lee, D.J.; Rahman, R.T.; and Nam, Y.S. Biomimetic Multilayered Lipid Nanovesicles for Potent Protein Vaccination. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2024 13, 2304109. Epub 2024 Jun 14. (PMID: 38849130). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).