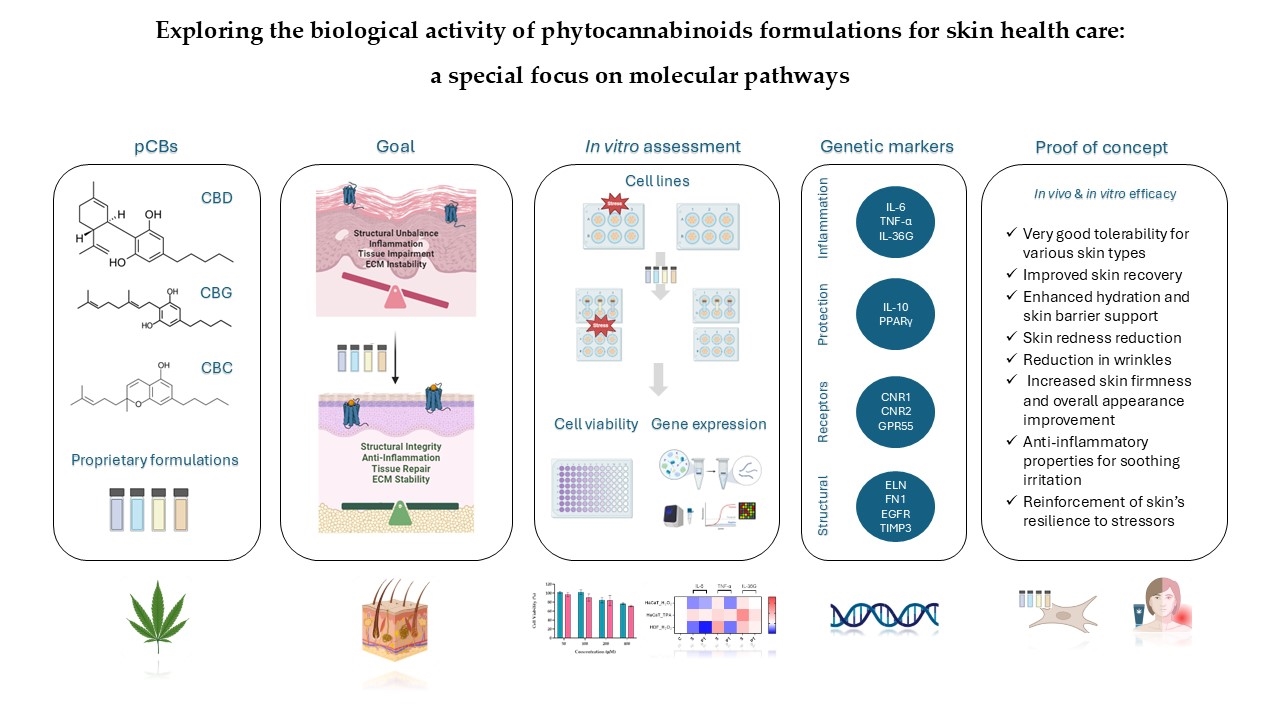

2.2. Evaluation of Gene Expression Markers in Cell Lines

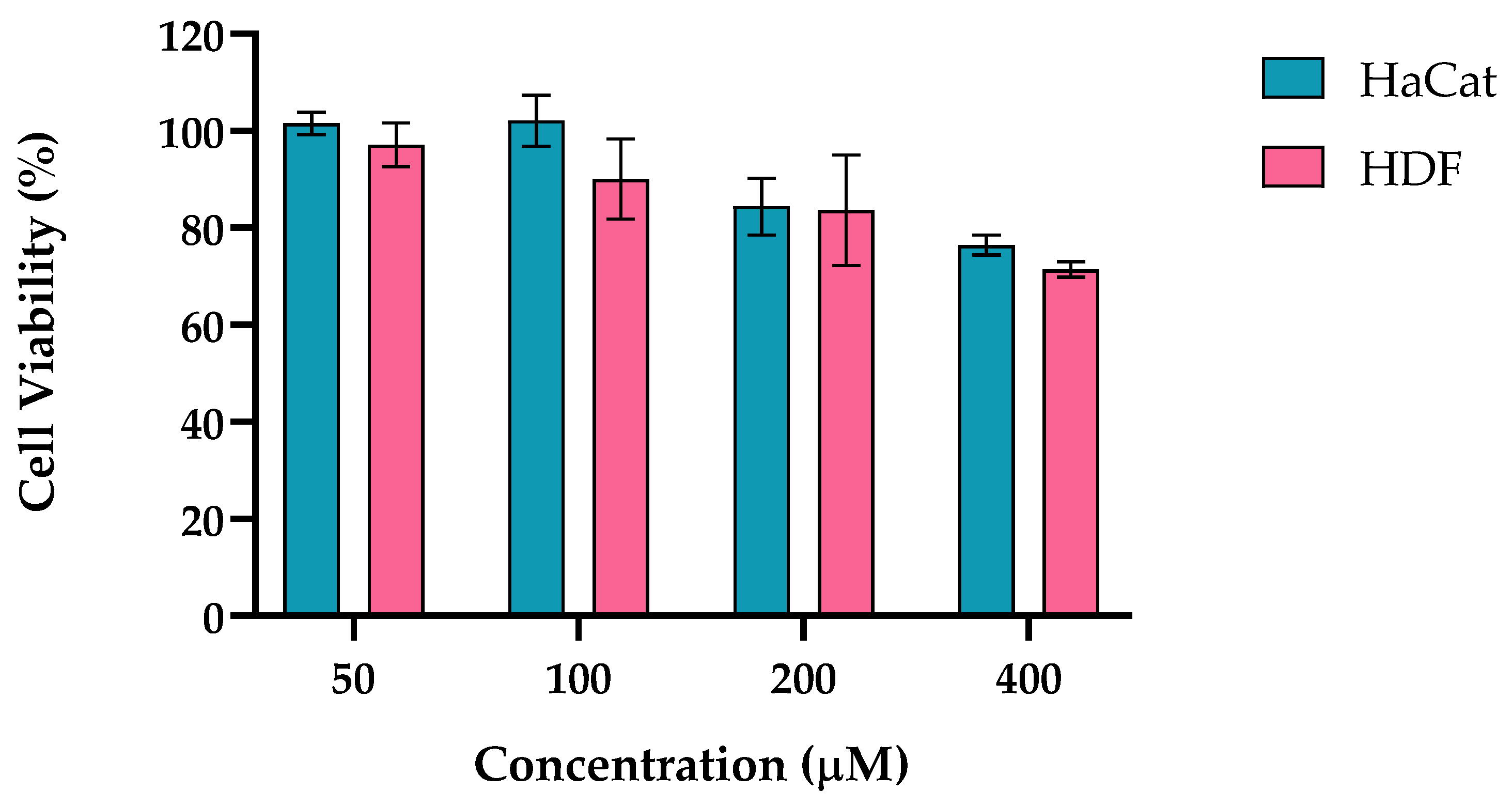

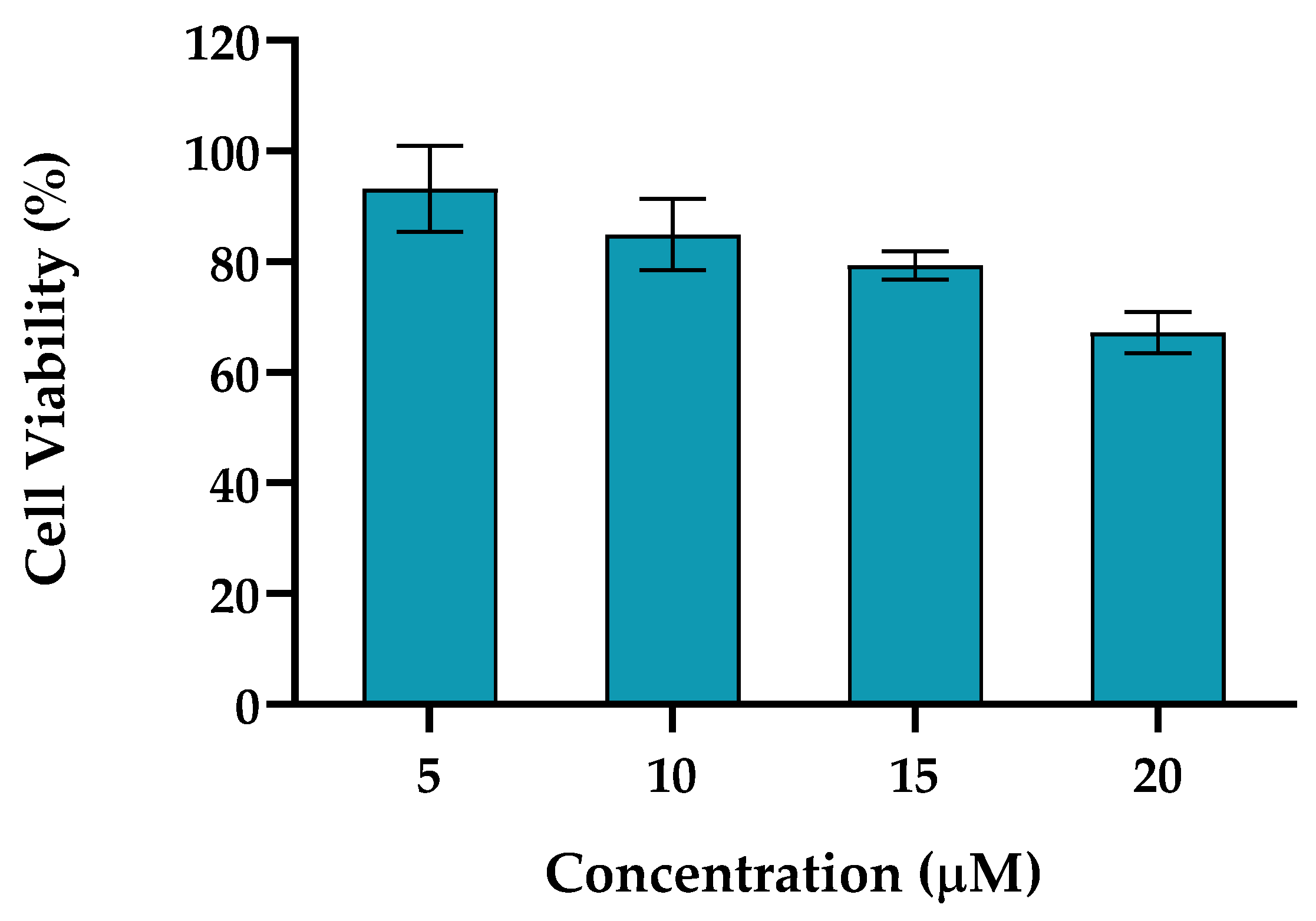

The use of HaCaT and HDF cell lines in studies of cannabinoid formulations provides valuable insights into their effects on inflammation, regeneration, and wound healing. Keratinocytes are the predominant cell type in the epidermis and play a significant role in the skin's response to injury and inflammation. Cannabinoid research using HaCaT has shown that pCBs can exert anti-inflammatory effects by modulating cytokine production and promote wound healing by enhancing keratinocyte migration [

1,

20]. This migration is a vital step in the re-epithelialization process during wound repair, thus restoring the skin's barrier function. HDF cells are also relevant for studying wound healing and regeneration as pCBs can influence fibroblast activity, which is crucial for tissue repair and ECM remodeling which provide structural support to the skin, affecting processes such as cell proliferation, migration, and collagen production. For instance, pCBs have shown to promote fibroblast proliferation and migration, which are critical for wound closure and tissue repair modulate the balance between inflammation and regeneration, which are crucial for effective wound healing and minimizing scarring [

40].

Using both HaCaT and HDF cell lines to model the complex interactions keratinocytes and fibroblasts allows us to better understand how pCBs-based formulations might modulate inflammation and regeneration highlighting their potential for cosmeceutical and/or therapeutic use in dermatology.

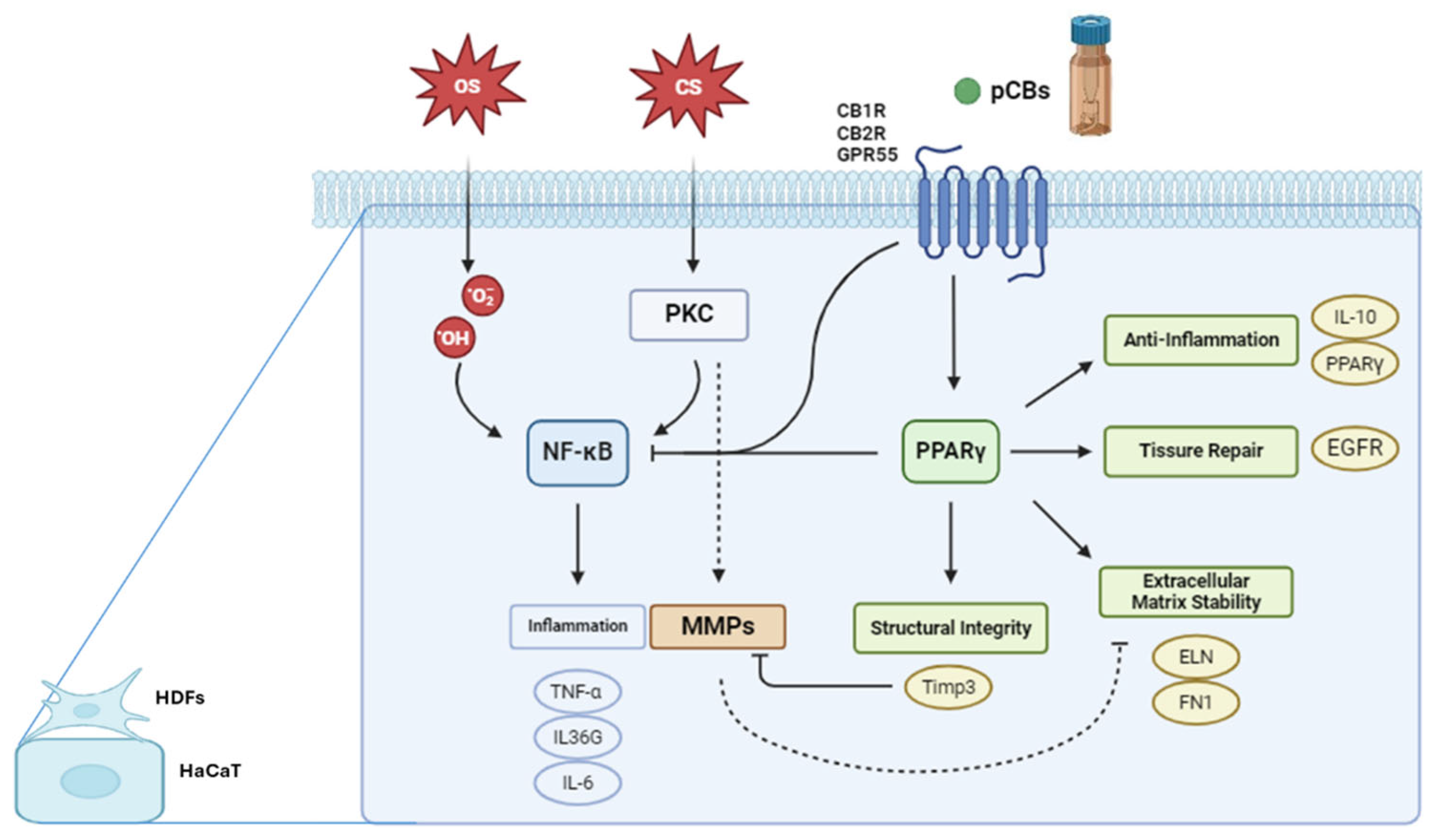

These cell lines express several key proteins and pathways involved in stress responses, inflammation, and tissue homeostasis. PKC is expressed in both HDF and HaCaT cells, playing a crucial role in signal transduction. In HaCaT cells, PKC activation, such as by phorbol esters like TPA, can stimulate the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway and activate Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs). The NF-κB pathway, active in both cell types, is a central mediator of inflammatory responses. Upon activation in HaCaT cells, NF-κB translocate to the nucleus, promoting the transcription of pro-inflammatory genes including Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 36G (IL-36G), and interleukin 6 (IL-6). Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor gamma (PPARγ) is expressed in both HDF and HaCaT cells. While its specific role in these cell lines requires further elucidation, PPARγ is known to be involved in regulating inflammation and maintaining skin homeostasis. MMPs are also expressed in both cell types, with their activation in HaCaT cells linked to PKC stimulation under conditions of chemical stress. pCBs, while not endogenously expressed, exert significant effects on both HDF and HaCaT cells. Recent studies have demonstrated that pCBs modulate inflammatory responses in HaCaT cells [

22,

41,

42,

43]. These effects are mediated through the ECS and signaling pathways. It is important to note that while both HDF and HaCaT cells express these proteins and pathways, their expression levels and responses to stimuli may differ due to their distinct origins and functions within the skin. This underscores the importance of considering cell type-specific responses when interpreting results from

in vitro studies using these models in skin biology and inflammation research.

Figure 3 illustrates the complex interplay between oxidative stress, chemical stress, and the ECS in modulating gene expression pathways within keratinocytes and fibroblasts. Oxidative stress inducers, such as H₂O₂, lead to an overproduction of ROS that activate the NF-κB signaling pathway [

44]. Once activated, NF-κB translocate to the cell nucleus, where it drives the transcription of pro-inflammatory genes, including TNF-α, IL-36G, and IL-6 [

45]. Chemical stressors, such as TPA, activate PKC, which in turn stimulates the NF-κB pathway, resulting in the transcription of the same inflammatory genes as seen in the oxidative stress pathway [

46]. Additionally, PKC activation triggers another signaling cascade that leads to the activation of MMPs. These zinc-dependent enzymes degrade components of the ECM, such as collagens and elastin (ELN), which can compromise ECM stability, tissue integrity, and cellular behavior [

46]. Cannabinoid receptors, including CNR1, CNR2, and GPR55, play vital roles in regulating various skin physiological processes like inflammation, pain perception, cell proliferation, and differentiation [

47]. CNR1 is linked with pain modulation, neuroprotection, and anti-inflammatory effects, CNR2 is primarily involved in anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory functions and G protein-coupled receptor 55 (GPR55), sometimes referred to as the "third" cannabinoid receptor, influences inflammatory responses and cell proliferation. Although pCBs may not always directly activate these receptors, they can modulate receptor expression and thereby influence the ECS [

30,

47]. Activation of these receptors can lead to PPARγ pathway activation, that is crucial for anti-inflammatory responses, tissue repair, and ECM maintenance. One significant gene regulated by PPARγ is TIMP3, which inhibits MMPs, preventing excessive ECM degradation and promoting tissue homeostasis. The activation of cannabinoid receptors and the PPARγ pathway can inhibit NF-κB by various mechanisms, such as preventing NF-κB from translocating to the nucleus, interfering with its DNA binding, or modulating upstream signals that activate NF-κB [

30,

48].

Stressors & Stress-baseline response

H₂O₂ induces oxidative stress, which leads to cellular damage and triggers responses such as inflammation, apoptosis, or senescence [

49,

50,

51]. TPA, on the other hand, activates signaling pathways, particularly through PKC [

46], which plays a crucial role in processes like signal transduction, cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and immune responses, often resulting in inflammation and potential tumorigenesis [

52,

53,

54].

Exposure to H₂O₂ and TPA typically stimulates an inflammatory response, increasing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-36G. IL-6 is essential during the acute phase of inflammation, while IL-36G is crucial in skin-related inflammatory responses and conditions like psoriasis. TNF-α promotes the recruitment of immune cells and enhances vascular permeability, further intensifying inflammation by stimulating other pro-inflammatory cytokines.

The regulation of anti-inflammatory markers like IL-10 and PPARγ is equally critical in managing damage and initiating repair. IL-10 reduces the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, limiting tissue damage and promoting healing. PPARγ plays a key role in controlling inflammation, regulating lipid metabolism, and promoting cellular differentiation and stress response. Both IL-10 and PPARγ are expected to be up-regulated by treatments aimed at reducing inflammation and aiding tissue repair.

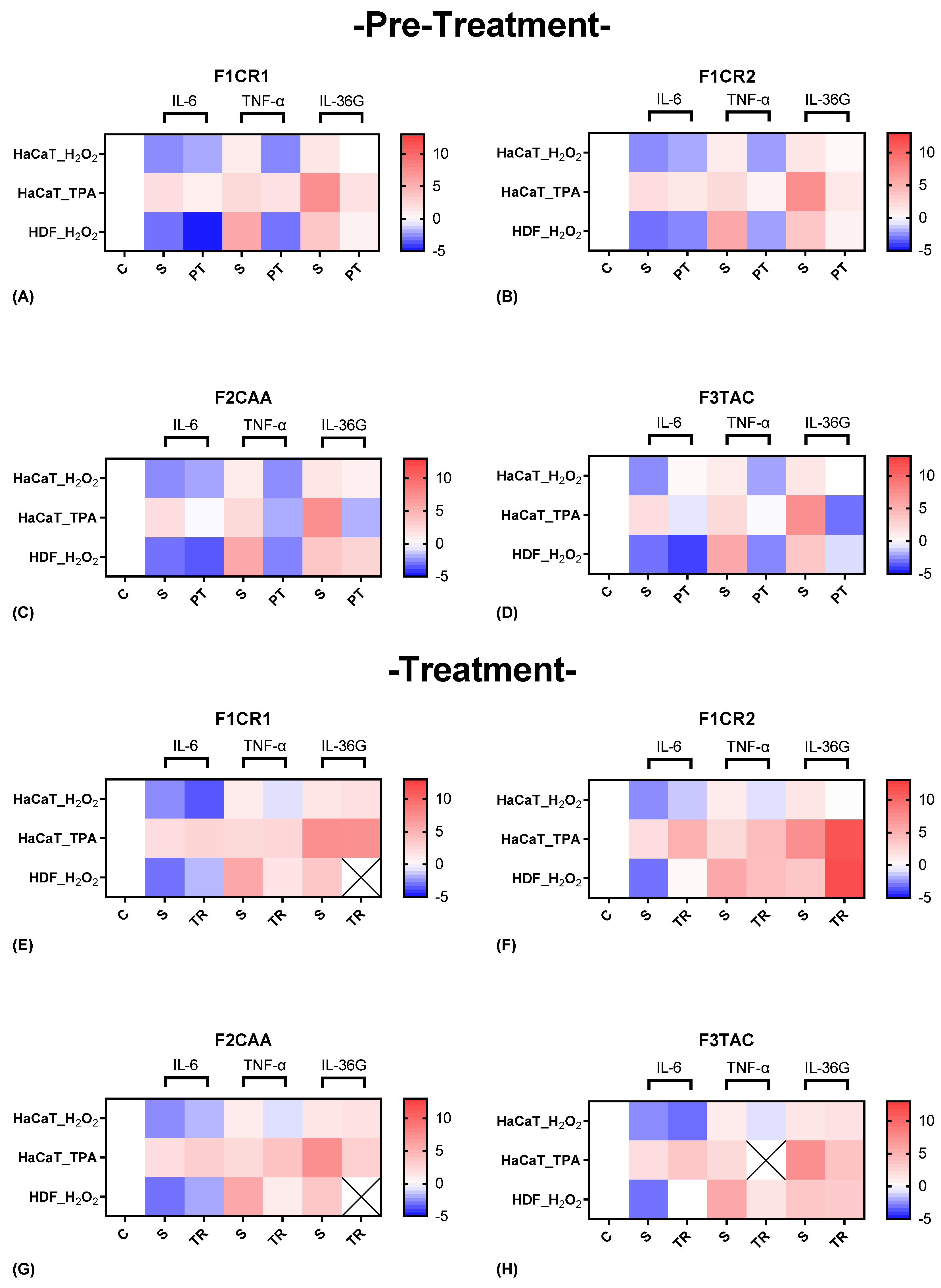

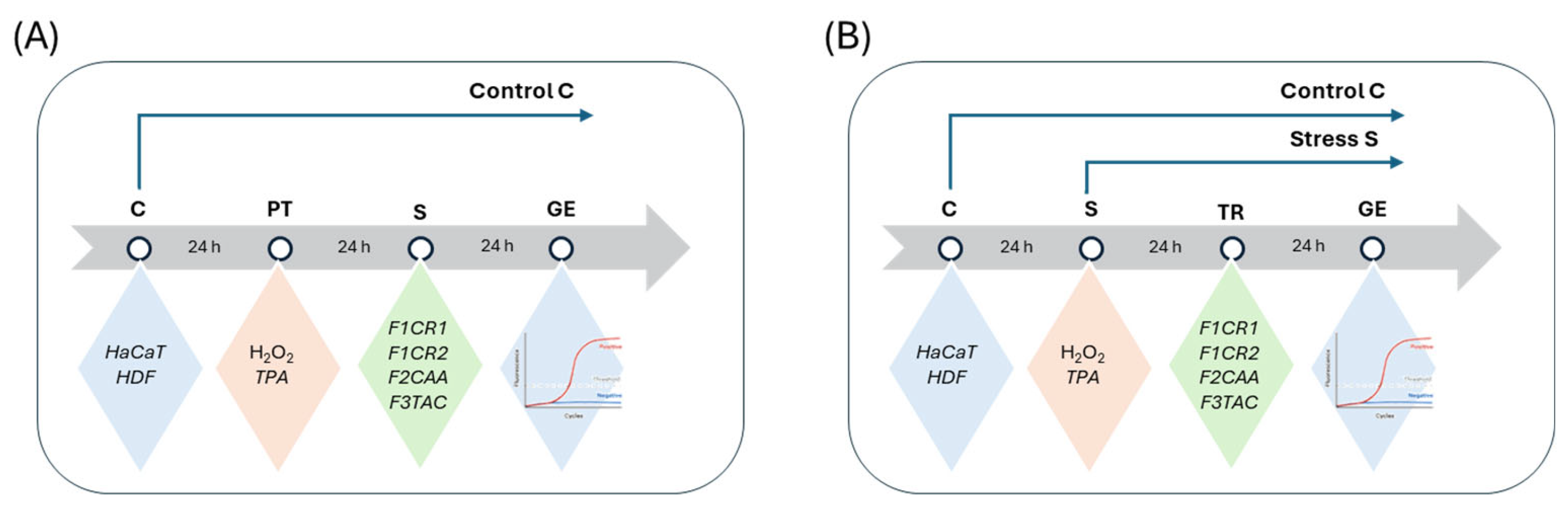

2.2.1. Molecular Insights into the Pro-Inflammatory Modulation by F1CR1, F1CR2, F2CAA, and F3TAC Formulations in Pre-Treatment and Treatment Conditions

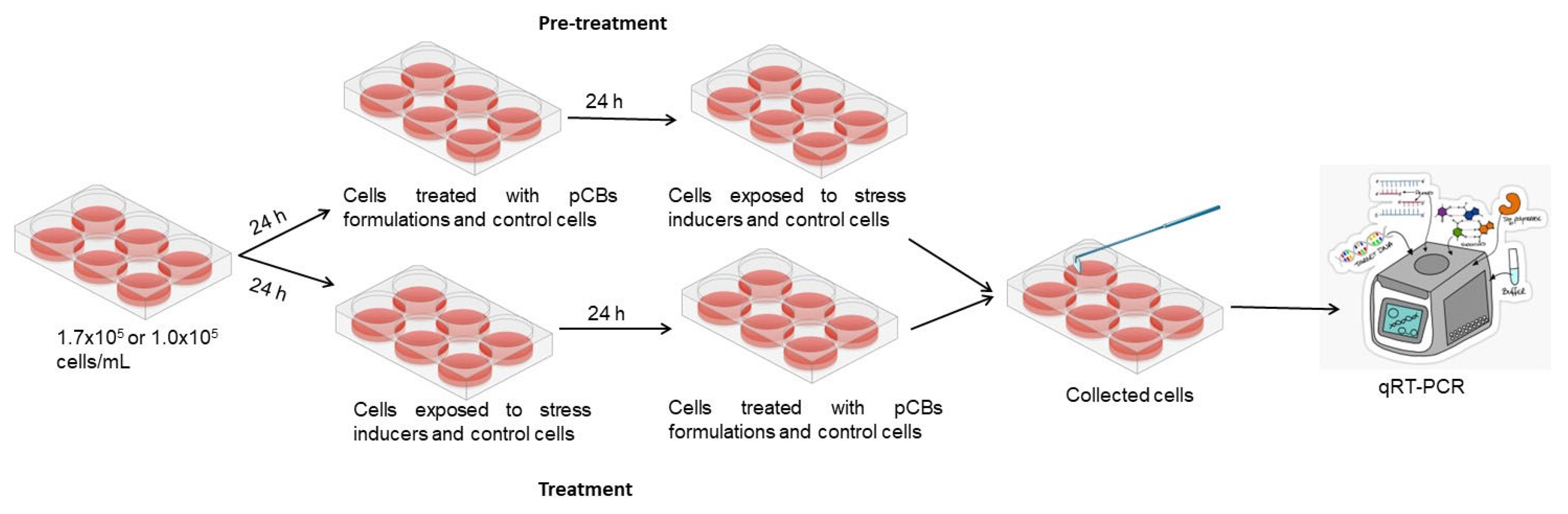

The effect of each one of the proprietary formulations on pro-inflammatory markers (IL-6, TNF-α and IL-36G), was assessed in HaCat and HDF cells following exposition to H

2O

2 and TPA, either in pre-treatment or treatment conditions (

Figure 4). Detailed results can be found in supplementary material, “S1 – Effect of formulations on pro-inflammatory markers”.

F1CR1 Pre-Treatment: resulted in a significant downregulation of key pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-36G) in both HaCaT and HDF cells (

Figure 4 A). This effect was consistent across both oxidative (H₂O₂) and inflammatory (TPA) stress conditions, indicating the broad anti-inflammatory potential of F1CR1. These results suggest that F1CR1 effectively primes skin cells to withstand oxidative and inflammatory stress, making it highly protective against skin damage. By reducing the expression of these pro-inflammatory markers, F1CR1 may help prevent chronic inflammation and associated tissue damage.

F1CR1 Treatment: F1CR1 also demonstrated significant efficacy when applied post-stress (

Figure 4 E). After oxidative or inflammatory stress, it reduced pro-inflammatory markers, suggesting its ability to control inflammation even after damage has occurred. This post-treatment effect indicates a potential therapeutic role for F1CR1 in managing ongoing skin inflammation, especially in conditions characterized by excessive oxidative stress or inflammation. Overall, F1CR1 modulates both inflammatory and regenerative processes in HaCat and HDF, offering protection and aiding recovery in various stress conditions.

F1CR2 Pre-Treatment: F1CR2 exhibited stress-dependent and cell-type-specific modulation of pro-inflammatory markers (

Figure 4 B). In HaCaT cells IL-6 was upregulated, while TNF-α and IL-36G were downregulated, suggesting that F1CR2 helps modulate the inflammatory response and offers protection against oxidative stress. In HDF cells, a strong downregulation of TNF-α and an upregulation of IL-36G was observed, highlighting a tailored inflammatory response that supports tissue repair. Pre-treatment before TPA-induced inflammatory stress in HaCaT cells resulted in a strong downregulation of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-36G, suggesting that F1CR2 helps control inflammation and prevents chronic skin damage under inflammatory conditions.

F1CR2 Treatment: the results varied depending on the type of stressor (

Figure 4 F). After oxidative stress, both HaCaT and HDF cells showed an upregulation of IL-6 and downregulation of TNF-α, indicating that F1CR2 helps manage inflammation while promoting tissue regeneration. IL-36G was downregulated in HaCaT cells but upregulated in HDF cells, suggesting a role in supporting tissue repair, especially in HDF. However, when F1CR2 was applied post-TPA stress, there was an upregulation of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-36G, indicating that F1CR2 may be less effective in controlling inflammation once the pro-inflammatory cascade is fully activated. This highlights the importance of timing when using F1CR2 for its anti-inflammatory and regenerative properties.

F2CAA Pre-Treatment: In HaCaT cells an upregulation of IL-6 and downregulation of TNF-α and IL-36G, suggesting a compensatory response to oxidative stress was achieved (

Figure 4 C). In HDF cells, F2CAA led to a consistent downregulation of all three pro-inflammatory markers, particularly TNF-α, indicating strong anti-inflammatory potential in fibroblasts. In HaCaT, F2CAA caused significant downregulation of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-36G, showing its ability to effectively prime the skin against inflammatory stressors.

F2CAA Treatment: After oxidative stress it was demonstrated an upregulation of IL-6 and a downregulation of TNF-α in both HaCaT and HDF cells, highlighting a selective modulation of inflammatory pathways, with stronger effects on HDF (

Figure 4 G). After TPA-induced stress, F2CAA caused a slight upregulation of IL-6 and TNF-α but a strong downregulation of IL-36G, indicating its effectiveness in targeting pathways like IL-36G, which are linked to chronic skin inflammation.

Overall, F2CAA demonstrates strong anti-inflammatory potential in both pre-treatment and treatment scenarios, with its ability to modulate key cytokines making it a valuable agent in managing skin inflammation

F3TAC Pre-Treatment: In HaCaT cells, pre-treated before H₂O₂, a strong upregulation of IL-6 and downregulation of TNF-α and IL-36G, indicating complex modulation of the inflammatory response was observed (

Figure 4 D). In HDF cells, pre-treated with F3TAC, all three pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-36G) were consistently downregulated, with TNF-α showing the most significant decrease. These results suggest that F3TAC has potent anti-inflammatory effects, particularly in HDF, where it significantly reduces inflammation under oxidative stress. Additionally, pre-treatment with F3TAC, before TPA-induced stress in HaCaT cells, resulted in a marked downregulation of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-36G, highlighting F3TAC’s potential to prime keratinocytes against inflammatory damage.

F3TAC Treatment: F3TAC’s effects on pro-inflammatory markers were more limited (

Figure 4 H). In HaCaT cells exposed to H₂O₂, a slight upregulation of IL-6 and downregulation of TNF-α and IL-36G, indicating that F3TAC can still modulate inflammation after oxidative damage, though less effectively than in pre-treatment scenarios was attained. In HDF cells, post-treatment with F3TAC led to an upregulation of IL-6 but strong downregulation of TNF-α, suggesting a continued anti-inflammatory effect in fibroblasts even after stress. After TPA-induced stress, F3TAC slightly upregulated IL-6 but strongly downregulated IL-36G, suggesting that it remains effective in modulating specific inflammatory pathways triggered by inflammatory stress.

The differential effects of F3TAC between pre-treatment and post-treatment scenarios highlight the importance of timing in modulating the inflammatory response in skin cells. Pre-treatment appears to prime cells to handle stress more effectively, while treatment shows F3TAC’s continued ability to manage inflammation and aid in tissue repair. These findings suggest that F3TAC has both protective and therapeutic properties depending on when it is administered.

2.2.2. Molecular Insights into the Anti-Inflammatory Effects of F1CR1, F1CR2, F2CAA, and F3TAC Formulations in Pre-Treatment and Treatment Conditions

The effect of each one of the proprietary formulations on anti-inflammatory markers (IL-10 and PPARγ), was assessed in HaCat and HDF cells following exposition to H

2O

2 and TPA, either in pre-treatment or treatment conditions (

Figure 5). Detailed results can be found in supplementary material, “S2 – Effect of formulations on anti-inflammatory markers”.

F1CR1 Pre-Treatment: In HaCaT cells exposed to H₂O₂ stress, no significant changes were observed in IL-10 and PPARγ regulation, suggesting that F1CR1 does not significantly alter the anti-inflammatory response in keratinocytes under oxidative stress (

Figure 5 A). However, in HDF cells, F1CR1 pre-treatment led to a notable downregulation of both IL-10 and PPARγ, indicating that F1CR1 may shift anti-inflammatory mechanisms in fibroblasts. When subjected to TPA stress, both HaCaT and HDF cells showed significant downregulation of IL-10 and PPARγ, suggesting that F1CR1’s effects vary based on cell type and stress conditions, potentially modulating inflammation through alternative pathways.

F1CR1 Treatment: In HaCaT cells after H₂O₂ stress, there was a downregulation of PPARγ, suggesting modulation of inflammatory responses and keratinocyte differentiation (

Figure 5 E). In HDF cells, F1CR1 led to an upregulation of IL-10 and a strong downregulation of PPARγ, highlighting its anti-inflammatory potential and modulation of metabolic and inflammatory pathways in HDF. Following TPA stress, HaCaT cells showed a downregulation of IL-10 without significant changes in PPARγ, suggesting stress-specific responses and different compensatory mechanisms depending on the type of stress.

F1CR2 Pre-Treatment: H

2O

2 stress led to a strong downregulation of IL-10 and a significant upregulation of PPARγ in both HaCaT and HDF cells (

Figure 5 B). In HaCaT cells, this suggests that F1CR2 prepares cells to handle oxidative stress by reducing the need for IL-10, potentially promoting stress tolerance and repair mechanisms. In HDF cells, F1CR2 reduced IL-10 dependency and enhanced PPARγ expression, indicating its role in regulating inflammation and promoting tissue repair.

F1CR2 Treatment: When F1CR2 was applied after H₂O₂ stress, no significant changes in IL-10 were observed in HaCaT cells, but PPARγ remained upregulated, indicating the continued activation of recovery pathways (

Figure 5 F). In HDF cells, IL-10 was upregulated, suggesting an active role in managing inflammation and supporting tissue repair. The consistent upregulation of PPARγ in both cell lines highlights F1CR2’s role in promoting anti-inflammatory responses and aiding recovery from oxidative stress, particularly in fibroblasts.

F2CAA Pre-Treatment: In HaCaT cells exposed to H₂O₂ stress, IL-10 was slightly upregulated, suggesting enhanced anti-inflammatory responses, while PPARγ remained stable (

Figure 5 C). In HDF cells, both IL-10 and PPARγ were downregulated, indicating a more targeted and cell-specific inflammation modulation. Under TPA stress, both IL-10 and PPARγ were downregulated in HaCaT cells, indicating stress-specific effects of F2CAA.

F2CAA Treatment: In HaCaT cells after H₂O₂ stress, there was a strong downregulation of both IL-10 and PPARγ, suggesting a more pronounced inflammatory modulation (

Figure 5 G). In HDF cells, IL-10 was downregulated, but PPARγ was upregulated, indicating an anti-inflammatory response. After TPA stress, HaCaT cells exhibited an upregulation of both IL-10 and PPARγ, indicating a protective response against inflammation. These results show that F2CAA’s effects are cell-type and stress-specific, with differing impacts on anti-inflammatory mediators.

F3TAC Pre-Treatment: In HaCaT cells, regarding H₂O₂ stress, there was a slight upregulation of IL-10 with no significant changes in PPARγ, indicating a potential enhancement of anti-inflammatory responses in keratinocytes (

Figure 5 D). However, in HDF cells, both IL-10 and PPARγ were downregulated, indicating cell-specific effects of F3TAC in modulating pro- and anti-inflammatory signals in fibroblasts. Pre-treatment with F3TAC before TPA stress led to significant downregulation of both IL-10 and PPARγ in HaCaT cells, suggesting F3TAC’s effects are stress-dependent and may involve other compensatory mechanisms.

F3TAC Treatment: Post-treatment with F3TAC in HaCaT cells after H₂O₂ stress resulted in slight but non-significant downregulation of IL-10 and PPARγ, suggesting limited effects on these markers after oxidative stress (

Figure 5 H). In HDF cells, there was a consistent downregulation of IL-10 and PPARγ, indicating that F3TAC has a more pronounced effect on modulating anti-inflammatory pathways in fibroblasts. After TPA stress, HaCaT cells showed no significant changes in IL-10 or PPARγ, further indicating that F3TAC’s effects are context-dependent

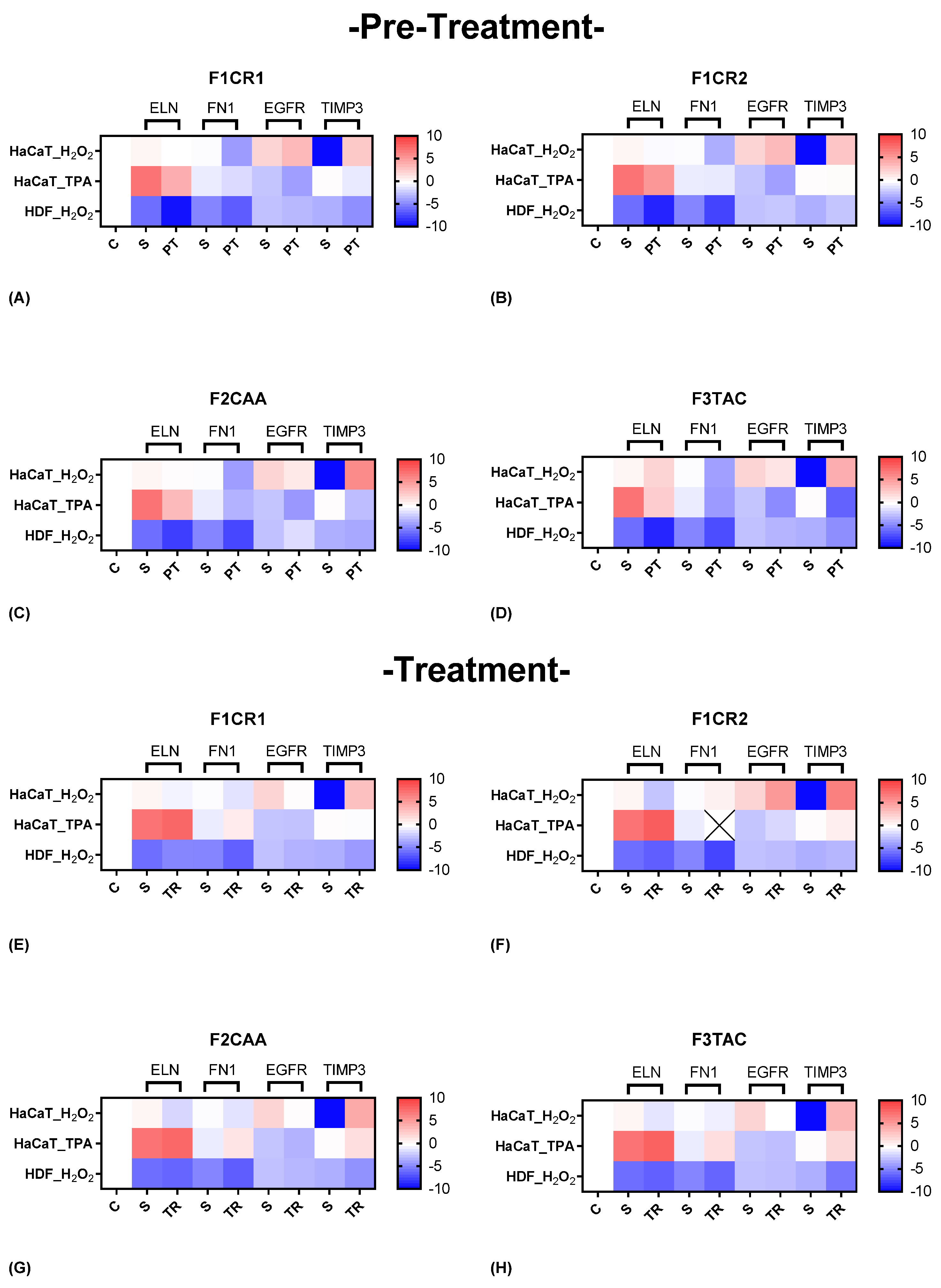

2.2.3. Molecular Insights into the Structural Modulation by F1CR1, F1CR2, F2CAA, and F3TAC Formulations in Pre-Treatment and Treatment Conditions

The effect of each one of the proprietary formulations on structural markers (ELN, FN1, EGFR and TIMP3), was assessed in HaCat and HDF cells following exposition to H

2O

2 and TPA, either in pre-treatment or treatment conditions (

Figure 6). Detailed results can be found in supplementary material, “S3 – Effect of formulations on structural markers”.

F1CR1 Pre-Treatment: In HaCaT cells, exposed to H₂O₂ stress, F1CR1 induced a strong downregulation of FN1 and an upregulation of both EGFR and TIMP3 (

Figure 6 A). This suggests a role in modulating ECM production and promoting cell survival and proliferation under oxidative stress. In HDF cells, under the same conditions, F1CR1 led to the downregulation of ELN, FN1, and TIMP3, highlighting cell-specific responses, possibly aimed at preventing fibrosis. Under TPA-induced stress, HaCaT cells experienced downregulation of ELN, FN1, TIMP3, and EGFR, indicating a protective response against inflammation and excessive cell proliferation. F1CR1 may help prepare cells to better cope with stress by modulating genes involved in ECM production, cell proliferation, and tissue remodeling.

F1CR1 Treatment: In HaCaT cells, after H₂O₂ stress, the FN1 downregulation suggests modulation of ECM production, potentially preventing excessive fibrosis (

Figure 6 E). The upregulation of EGFR points to the restoration of normal cell proliferation and differentiation, while the stronger upregulation of TIMP3 indicates enhanced ECM remodeling and protection against oxidative damage. In HDF cells, F1CR1 led to a slight upregulation of ELN, indicating a mild protective effect on skin elasticity, with a subtle downregulation of FN1, EGFR, and TIMP3, suggesting less pronounced remodeling activity. After TPA-induced stress, HaCaT cells showed no significant changes in ELN, TIMP3, and EGFR, but FN1 was upregulated, potentially reflecting an enhanced wound healing response to inflammation.

F1CR2 Pre-Treatment: In HaCaT cells exposed to H₂O₂ stress, there was a downregulation of ELN and FN1, suggesting a protective mechanism against oxidative damage and potential prevention of excessive fibrosis (

Figure 6 B). The upregulation of EGFR and TIMP3 indicates enhanced cellular proliferation and ECM remodeling, aiding tissue repair. In HDF cells, F1CR2 pre-treatment led to upregulation of ELN and FN1, suggesting enhanced structural support and wound healing under stress.

F1CR2 Treatment: When F1CR2 was applied after H₂O₂ stress, HaCaT cells showed enhanced ECM production (upregulated FN1) and tissue regeneration (upregulated EGFR and TIMP3) (

Figure 6 F). In HDF cells, there was a strong downregulation of ELN and FN1, possibly to prevent excessive scarring, with a slight upregulation of TIMP3 indicating controlled matrix remodeling. After TPA-induced stress, HaCaT cells demonstrated upregulation of ELN and TIMP3, with slight downregulation of EGFR, indicating a focus on structural support and matrix stabilization in response to inflammation.

F2CAA Pre-Treatment: In HaCaT cells, regarding H₂O₂ stress, a strong downregulation of FN1 and EGFR, along with a strong upregulation of TIMP3, suggesting a protective mechanism against oxidative stress by reducing ECM degradation and fibrosis was observed (

Figure 6 C). In HDF cells, F2CAA pre-treatment led to a downregulation of ELN and FN1, with an upregulation of EGFR, indicating modulation of ECM production and cell proliferation in fibroblasts.

F2CAA Treatment: In post-treatment and after H₂O₂ stress, HaCaT cells showed downregulation of ELN, FN1, and EGFR, alongside strong upregulation of TIMP3, indicating protection against ECM degradation (

Figure 6 G). In HDF cells, downregulation of FN1, ELN, and TIMP3 was observed, suggesting a complex modulation of ECM balance in fibroblasts under oxidative stress. After TPA stress, HaCaT cells exhibited slight upregulation of ELN, FN1, and TIMP3, with slight downregulation of EGFR, indicating tissue repair promotion and moderation of cell proliferation under inflammatory conditions.

F3TAC Pre-Treatment: In HaCaT cells, considering H₂O₂ stress, the upregulation of ELN suggests improved skin elasticity, while the strong downregulation of FN1 and EGFR indicates reduced cell proliferation and migration (

Figure 6 D). The very strong upregulation of TIMP3 suggests enhanced protection against ECM degradation. In HDF cells pre-treated with F3TAC under H₂O₂ stress, downregulation of ELN, FN1, and TIMP3 indicates reduced ECM production and remodeling, with stable EGFR levels suggesting maintained cell proliferation.

F3TAC Treatment: When HaCaT cells were treated with F3TAC after H₂O₂ stress, FN1 remained stable, suggesting preserved ECM production (

Figure 6 H). The strong downregulation of EGFR indicates reduced cell proliferation, while the strong upregulation of TIMP3 points to enhanced matrix protection. In HDF cells treated after H₂O₂ stress, downregulation of ELN, FN1, and TIMP3 suggests reduced matrix production and remodeling, with stable EGFR levels maintaining cell proliferation. After TPA stress, HaCaT cells treated with F3TAC showed upregulation of ELN, TIMP3, and slight upregulation of FN1, indicating enhanced matrix production and protection, while EGFR remained unchanged, reflecting stable cell proliferation capacity.

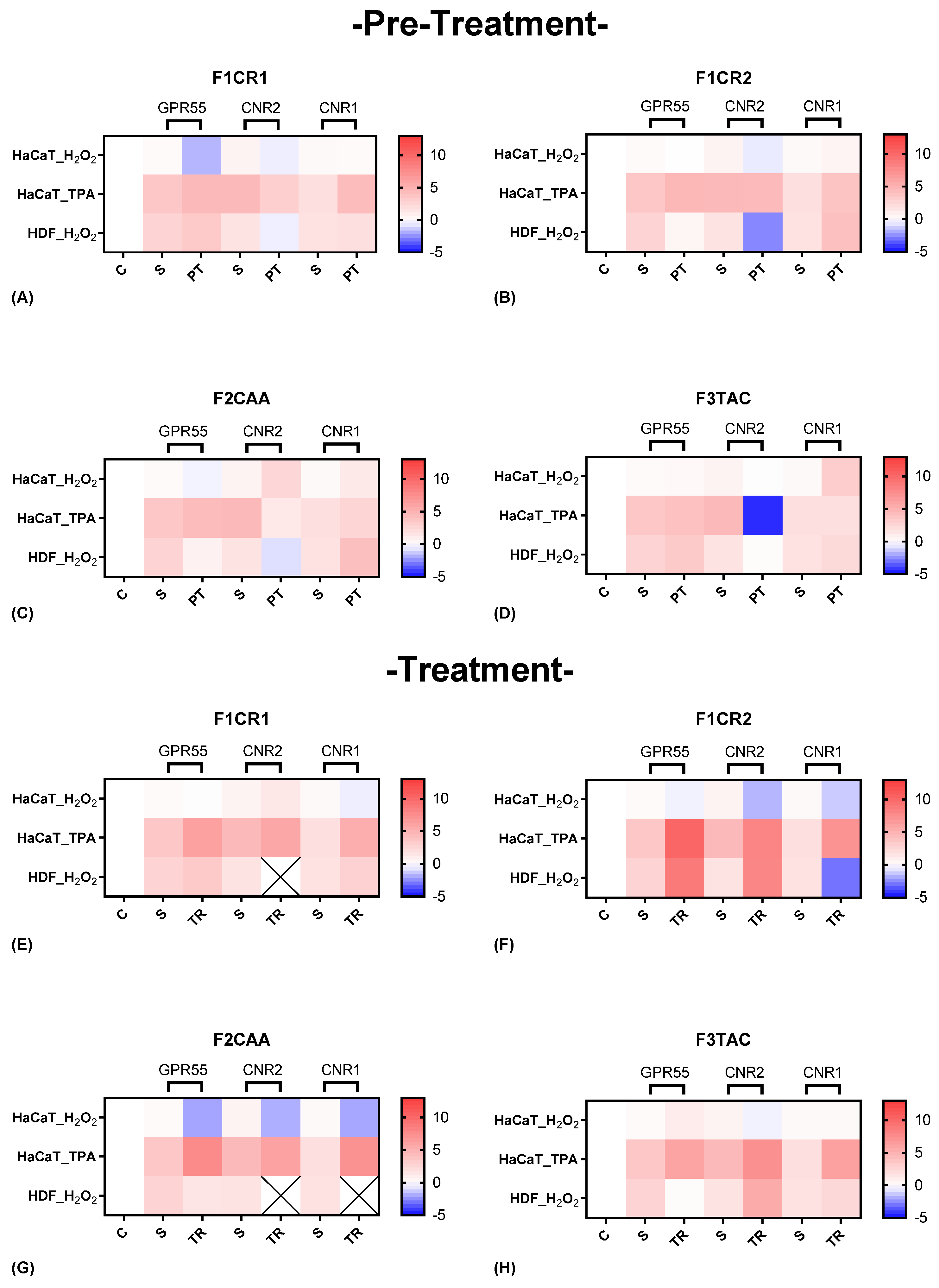

2.2.4. Molecular Evaluation of Cannabinoid Receptor Modulation by F1CR1, F1CR2, F2CAA, and F3TAC Formulations in Pre-Treatment and Treatment Scenarios

The effect of each one of the proprietary formulations on cannabinoid receptor markers (GPR55, CNR2 and CNR1), was assessed in HaCat and HDF cells following exposition to H

2O

2 and TPA, either in pre-treatment or treatment conditions (

Figure 7). Detailed results can be found in supplementary material, “S4 – Effect of the formulations on cannabinoid receptor markers”.

F1CR1 Pre-Treatment: Exposed to H₂O₂ stress, GPR55 and CNR2 were downregulated in HaCat cells, suggesting potential anti-inflammatory actions, while CNR1 remained unchanged (

Figure 7 A). In contrast, HDF cells showed an upregulation of GPR55 and downregulation of CNR2, highlighting cell-specific responses, with GPR55 potentially aiding wound healing in fibroblasts. Under TPA-induced stress, HaCaT cells experienced upregulation of GPR55 and downregulation of CNR2, reinforcing the stress-specific nature of F1CR1’s effects.

F1CR1 -Treatment: After H₂O₂ treatment, F1CR1 upregulated CNR2 and downregulated CNR1 in HaCaT cells, indicating modulation of HaCat inflammation, while HDF showed mild upregulation of GPR55 and CNR1 (

Figure 7 E). Post-TPA treatment, all three receptors—GPR55, CNR2, and CNR1—were upregulated, suggesting F1CR1 activates the ECS to reduce inflammation and support regeneration under inflammatory stress. These results highlight the complex and context-dependent effects of F1CR1 on the ECS in skin cells.

F1CR2 Pre-Treatment: The application of F1CR2 prior to H₂O₂-induced oxidative stress in HaCaT cells resulted in the downregulation of GPR55 and CNR2, accompanied by an upregulation of CNR1 (

Figure 7 B). The downregulation of GPR55 suggests that F1CR2 may be attenuating pro-inflammatory effects, while the upregulation of CNR1 points to enhanced protective mechanisms against oxidative stress. In HDF cells, F1CR2 led to a strong upregulation of GPR55 and CNR2, with downregulation of CNR1, indicating activation of pathways involved in wound healing and tissue remodeling.

F1CR2 -Treatment: In HaCaT cells, after H₂O₂-induced stress, CNR1 remained upregulated, but CNR2 and GPR55 were downregulated, indicating a reduced pro-inflammatory response (

Figure 7 F). In HDF cells, GPR55 and CNR2 were upregulated, promoting regenerative and anti-inflammatory responses, while CNR1 was downregulated, potentially indicating a shift towards cellular repair. This highlights that the timing of F1CR2 application is crucial for maximizing its anti-inflammatory and regenerative benefits.

F2CAA Pre-Treatment: In HaCaT cells, and before H₂O₂ stress, GPR55 was downregulated while CNR1 and CNR2 were upregulated, indicating a protective, anti-inflammatory effect (

Figure 7 C). In HDF cells, F2CAA pre-treatment also downregulated GPR55 and CNR2, with CNR1 upregulated, suggesting cell-specific protective responses. Under TPA stress, F2CAA caused GPR55 upregulation and CNR2 downregulation in HaCaT cells, pointing to a modulation of inflammatory pathways depending on the stress type.

F2CAA Treatment: Treatment with F2CAA, after H₂O₂ stress, led to the downregulation of all three receptors in HaCaT cells, suggesting a focus on reducing oxidative stress effects (

Figure 7 G). In HDF cells, only GPR55 was slightly downregulated, indicating a milder modulation. After TPA stress, F2CAA caused upregulation of all three receptors, showing enhanced cannabinoid signaling and tissue repair post-inflammation. These results emphasize the importance of timing when administering F2CAA, as it appears to provide both protective and regenerative benefits depending on when it is applied.

F3TAC Pre-Treatment: In HaCaT cells, and before H₂O₂ stress, GPR55 and CNR2 were slightly upregulated, and CNR1 was strongly upregulated, suggesting protection against oxidative stress through anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects (

Figure 7 D). In HDF cells, F3TAC pre-treatment led to slight upregulation of GPR55 and CNR1, with downregulation of CNR2, indicating cell-specific protective mechanisms in the dermal layer. Under TPA stress, HaCaT cells pre-treated with F3TAC showed upregulation of GPR55, downregulation of CNR2, and unchanged CNR1, reflecting modulation of stress-specific inflammatory pathways.

F3TAC Treatment: In HaCaT cells, and after H₂O₂ stress, CNR2 was significantly downregulated, GPR55 was slightly upregulated, and CNR1 remained unchanged, indicating a shift in inflammatory modulation and regeneration post-stress (

Figure 7 H). In HDF cells, GPR55 was downregulated, while CNR1 and CNR2 were strongly upregulated, enhancing cannabinoid signaling and promoting anti-inflammatory and regenerative responses. Post-TPA treatment in HaCaT cells led to significant upregulation of all three receptors, suggesting enhanced cannabinoid signaling for repair and recovery from inflammatory stress.

The most noticeable results are indicated in

Table 1, highlighting the potential pathways involved in modulation of pro-inflammatory, anti-inflammatory and cannabinoid receptor markers and ECM regulation suggested from the

in vitro assays.

The observed effects across different cell lines suggest that F1CR1, F1CR2, F2CAA and F3TAC formulations may influence cell-specific and stress-dependent responses, highlighting their capacity to modulate inflammatory and regenerative processes in a controlled environment. These findings point to possible mechanisms that could be further explored for their therapeutic relevance.

2.3. In-Vivo Efficacy Assays in Human Volunteers: A Proof of Concept

The regenerator cream, formulated with the F1CR1 combination, demonstrated significant efficacy in promoting skin recovery and regeneration across multiple dimensions. This aligns with the previously discussed properties of F1CR1, which include potent anti-inflammatory effects, enhancement of cellular repair mechanisms, and modulation of key structural and inflammatory pathways.

The application of the F1CR1-associated regenerator cream for 28 days significantly accelerated the reduction of skin redness, decreasing the recovery time by 2.7 days (12%, p<0.05) compared to the control. This outcome is consistent with F1CR1's ability to downregulate pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, which are responsible for prolonged inflammation and redness in the skin. The cream also effectively impacted microcirculation, reducing recovery time by 1.9 days (6.6%, p<0.05) compared to the control. This improvement could be due to F1CR2’s influence on the ECS, particularly through its modulation of cannabinoid receptors, which play a role in maintaining microcirculation and reducing vascular inflammation. The cream enhanced skin's barrier function, shortening the recovery time by 2.7 days (11%, p<0.05) versus the control. The cream exhibited excellent skin compatibility and acceptability, with no adverse reactions reported throughout the study, reflecting the formulation’s safety and tolerability.

Subjective efficacy results at the study's conclusion were also positive. 79% of participants reported softer, more hydrated skin with an overall improved appearance, likely due to F1CR1’s role in promoting skin hydration and repair. 64% of subjects agreed that their skin was effectively repaired, with 36% stating complete skin reparation, underscoring F1CR1’s ability to enhance the skin's natural healing processes. 93% observed a noticeable reduction in skin redness, consistent with the anti-inflammatory properties of F1CR1. In terms of cosmetic qualities, the cream was well-received by all participants. 100% of subjects appreciated the cream's texture, agreeing that it spread and absorbed easily, which likely contributed to the overall positive user experience and efficacy in daily use.

The application of F1CR2 for 28 days resulted in a reduction in erythema recovery time by 2.2 days (9.5%) compared to the control. The anti-inflammatory properties observed in pre-treated HaCaT and HDF support this result. Erythema, often accompanied by increased blood flow, was similarly affected, with F1CR2 reducing blood flow recovery time by 0.8 days (1.6%) compared to the control. The slight reduction in blood flow recovery time may be linked to F1CR2's ability to modulate the skin's ECS, particularly through the upregulation of CNR1 and CNR2 receptors. This modulation could help improve microcirculation and vascular function, leading to faster recovery from increased blood flow associated with erythema. The use of F1CR2 reduced barrier recovery time by 1.4 days (5.4%) when compared to the control. F1CR2's impact on ECM components and structural markers such as TIMP3 and FN1, as seen in vitro, likely contributes to its efficacy in enhancing skin barrier recovery.

No adverse reactions were reported during the study, indicating that F1CR2 exhibited excellent skin compatibility and acceptability. Regarding the subjective efficacy of F1CR2, 79% of participants agreed that the appearance of their skin had improved, 86% stated that their skin felt soft and hydrated, 86% agreed that their skin was repaired, with 50% noting full repair, 93% observed a reduction in skin redness. In terms of cosmetic qualities, 100% of participants liked the texture of F1CR2, and 92% agreed that it was easily absorbed and spread on the skin.

The application of the F2CAA cream resulted in a modest reduction across various skin spot metrics, including a 3.6% decrease in the count of visible spots, a 5.6% decrease in their area, a 4.3% reduction in UV spot area, and a 3.7% decrease in red spot count. The antioxidant capacity of the cream was evaluated by inducing an oxidation reaction with UVA radiation. Using β-carotene, a yellow chromophore that loses its color upon oxidation, it was observed that the untreated control area exhibited a 53.6% greater color variation compared to the area treated with the cream. This statistically significant result (p<0.05) indicates that the cream effectively mitigates oxidation under UVA exposure.

The cream demonstrated a statistically significant reduction (p<0.05) in the count of wrinkles and fine lines by 21.2%. Additionally, the application of the cream significantly improved (p<0.05) skin firmness by 11.9% and significantly decreased (p<0.05) skin roughness, while a non-significant increase of 1.2% in skin elasticity was observed. The efficacy of the cream in reducing wrinkles was further corroborated through clinical evaluation using the crow’s feet clinical score. After 28 days of application, a significant reduction (p<0.05) of 9.5% in the crow’s feet score was recorded, highlighting the cream’s effectiveness in diminishing the appearance of wrinkles.

Post-treatment analysis revealed a statistically significant decrease of 21.4% in the maximum microcirculation value and a significant 40.6% increase in the onset time to vasodilation. These findings suggest that the cream effectively reduces vasodilation and delays its onset when induced by histamine, thereby demonstrating its soothing properties. These outcomes suggest that the cream not only reduces the extent of vasodilation—a key marker of inflammation—but also delays its onset, indicating a soothing effect on the skin. The study also reported a statistically significant 19.1% reduction in Trans Epidermal Water Loss (TEWL), indicating an enhancement of the skin barrier function. In terms of hydration, the treatment led to a statistically significant 32.3% increase in skin hydration, further substantiating the cream’s efficacy in improving both hydration and skin barrier integrity. The reduction in TEWL and the improvement in skin barrier function further support the anti-inflammatory conclusion, as a well-functioning skin barrier is essential for protecting against environmental stressors and reducing inflammatory responses.

No adverse reactions were documented throughout the study, confirming the cream's excellent skin compatibility and acceptability.

Regarding the subjective efficacy of the cream, 100% of participants reported that their skin felt softer, 86% noted immediate hydration, 93% observed that their skin appeared hydrated, glowing, and radiant, 86% felt their skin was firmer, 64% noted a reduction in the appearance of lines and wrinkles, 86% reported that their skin felt restored and rejuvenated, 71% agreed that their skin looked and felt plumped and youthful, 86% felt their skin was nourished, 93% agreed that their skin felt energized, brighter, and that its texture was improved and more even, 50% observed a reduction in hyperpigmentation, 86% noticed a reduction in pore size, and 64% reported a reduction in skin redness.

Regarding the cosmetic formulation, 100% of participants expressed satisfaction with the texture and found the product easy to absorb and spread.

In conclusion, these findings suggest that the F2CAA cream is effective in improving the appearance of aging skin, provides antioxidant protection, and exhibits soothing effects after 28 days of consistent use.

For all the creams, no adverse reactions were reported during the study. This aligns with the in vitro findings for which, each formulation demonstrated a capacity to modulate inflammation without triggering excessive pro-inflammatory responses. The high percentage of participants reporting skin repair, hydration, and improved appearance can be attributed to the formulation role in upregulating key regenerative markers. These factors contribute to enhanced tissue repair, collagen synthesis, and overall skin health, as seen in both HaCat and HDF. The reduction in skin redness reported by participants directly correlates with anti-inflammatory properties demonstrated in vitro.

Regarding the application of F3TAC, there was an increase in the count and area of red spots, a slight decrease in the count of visible spots accompanied by an increase in their area, and an increase in the lipidic index, suggesting that the anti-acne tonic may not be performing as expected in reducing signs of acne. A possible explanation for these outcomes can be that sometimes, topical treatments, especially those targeting acne, can trigger an initial purging phase. This is a period where the skin begins to expel impurities from beneath the surface, leading to a temporary increase in spots and redness. The increase in red spots and their area could be indicative of this purging process, where the skin is reacting to the active ingredients in the tonic by bringing underlying issues to the surface.

Moreover, a positive outcome was that there was a 10.4% decrease in both porphyrins count and area. Porphyrins are produced by bacteria such as

Cutibacterium acnes, and known as virulence factor involved in the pathogenesis of acne [

55,

56]. High levels are associated with increased acne severity, whereas a reduction in porphyrins correlates with acne improvement [

57].

Regarding hydration and skin barrier function, the product demonstrated a 12.9% increase in skin hydration and a 20.7% increase in TEWL

Subjective assessments of the tonic’s efficacy revealed that 67% of participants agreed that their skin appeared brighter, felt protected, and that skin irritation was reduced with regulated sebum secretion, 83% agreed that oil production was controlled and skin texture improved, 75% reported a reduction in blemishes and breakouts,67% observed a reduction in the size and color of blemishes, with faster disappearance, 58% felt their skin was more balanced and noted improvement as early as the fifth day of use, 41% agreed that their skin felt more hydrated, 75% felt their skin was calm, soothed, and non-greasy after application, 41% noticed a reduction in hyperpigmentation, 58% saw a reduction in scarring associated with blemishes or acne, 50% agreed that pore size and skin redness were reduced. Regarding the cosmetic formulation, 92% of participants liked the texture and 83% agreed that the product absorbed easily.

No adverse reactions were reported during the study, confirming that the tonic exhibited good skin compatibility and acceptability.

In conclusion, while the product produced changes across all measured parameters, these differences were not statistically significant, the results indicate a trend towards a reduction in pore appearance and porphyrins, aligning with the intended purpose of an anti-acne tonic.

To enhance the efficacy of the tonic, several strategies could be considered, focusing on both formulation improvements and complementary approaches, by increasing the concentration of key active ingredients (within safe limits), can be combined with F1CR2 and / or tested during more time. The efficacy of acne treatments should typically be monitored over a period of 8 to 12 weeks as the skin cycle, or the time it takes for new skin cells to form and reach the surface, is about 4 to 6 weeks. Monitoring for at least two full skin cycles allows for a more accurate assessment of how well the treatment is working. Most topical acne treatments require several weeks to start showing noticeable effects. Initial improvements in acne lesions, reduction in inflammation, and overall skin texture often become evident after 4 to 8 weeks of consistent use.

This work confirmed the effectiveness and safety of the pCBs-based formulations for skin applications, highlighting their potential to improve its regeneration, and enhance structural processes. This research further underscores the significant promise of cannabis-based formulations in both the cosmetic and dermatological industries, offering substantial value to consumers seeking advanced skincare solutions. With increasing consumer demand for natural and effective products, cannabis-based products are poised to attract growing interest from both the public and industries, potentially reshaping the landscape of modern skincare and therapeutic applications.