Introduction

Areca palm (

Areca catechu L.) is a crucial crop for over 2 million farmers in Hainan Province, China [

1]. Its cultivation, however, is severely threatened by yellow leaf disease (YLD), which significantly reduces fruit yield and causes substantial economic losses [2, 3]. The absence of resistant cultivars underscores the urgent need to develop virus-resistant varieties through genetic engineering. Traditional

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation systems have faced significant challenges in areca palm, a perennial tropical tree [4, 5]. Indeed, transient

in planta expression has not been reported due to the tough, waxy nature of its leaves.

Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS), an RNA-silencing-based method, offers a rapid and efficient alternative for gene silencing in plant species that are difficult to genetically transform [6-9]. VIGS has been successfully utilized in functional genomics research for various woody species, including

Populus euphratica,

Malus domestica, and

Prunus spp. [10-12]. Beyond functional studies, VIGS has also been applied to combat viral diseases, such as the development of a VIGS-based vaccine from Apple latent spherical virus to control three tospoviruses [

13].

For VIGS application in areca palm, the identification of a mild virus isolate with lower virulence is essential.

Areca necrotic spindle-spot virus (ANSSV) is a positive-sense single-stranded

Potyvirus with a genome of 9,437 nucleotides [14-18]. While an infectious ANSSV clone has successfully infected

Nicotiana benthamiana [

19], its inability to infect areca palm and the severe symptoms it induces in

N. benthamiana make it unsuitable as a VIGS vector. Establishing a transient transformation system is also critical for developing VIGS. Microparticle bombardment using gene gun technology is an efficient method for transferring foreign DNA into plant cells, particularly in species resistant to

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation [20, 21]. The second-generation Helios hand-held Gene Gun system enables direct transformation of intact plants, bypassing callus culture and facilitating studies in both herbaceous and woody species [22-24]. Its applications include transforming

Arabidopsis thaliana,

Nicotiana tabacum, and crops like

Solanum tuberosum, highlighting its potential for studying complex traits, such as disease resistance, in perennial woody plants [25, 26].

In our previous work, we identified a mild ANSSV isolate (ANSSVm) showing mild symptoms on its host and possessing a shorter genome (7,868 nt), making it a suitable candidate for engineering as a VIGS vector for areca palm. This study reports the construction of an infectious ANSSVm clone and its transformation into N. benthamiana through agroinfiltration. Additionally, using β-glucuronidase (GUS) and RUBY as reporter genes [27, 28], exogenous gene was first reported to transiently expressed in areca palm seedlings through microparticle bombardment. Although the transformation of the ANSSVm infectious clone in areca palm has not yet been achieved, this work lays a foundation for developing VIGS in areca palm.

Results

Construction and Transmission of Vectors Expressing Reporter Gene in N. benthamiana

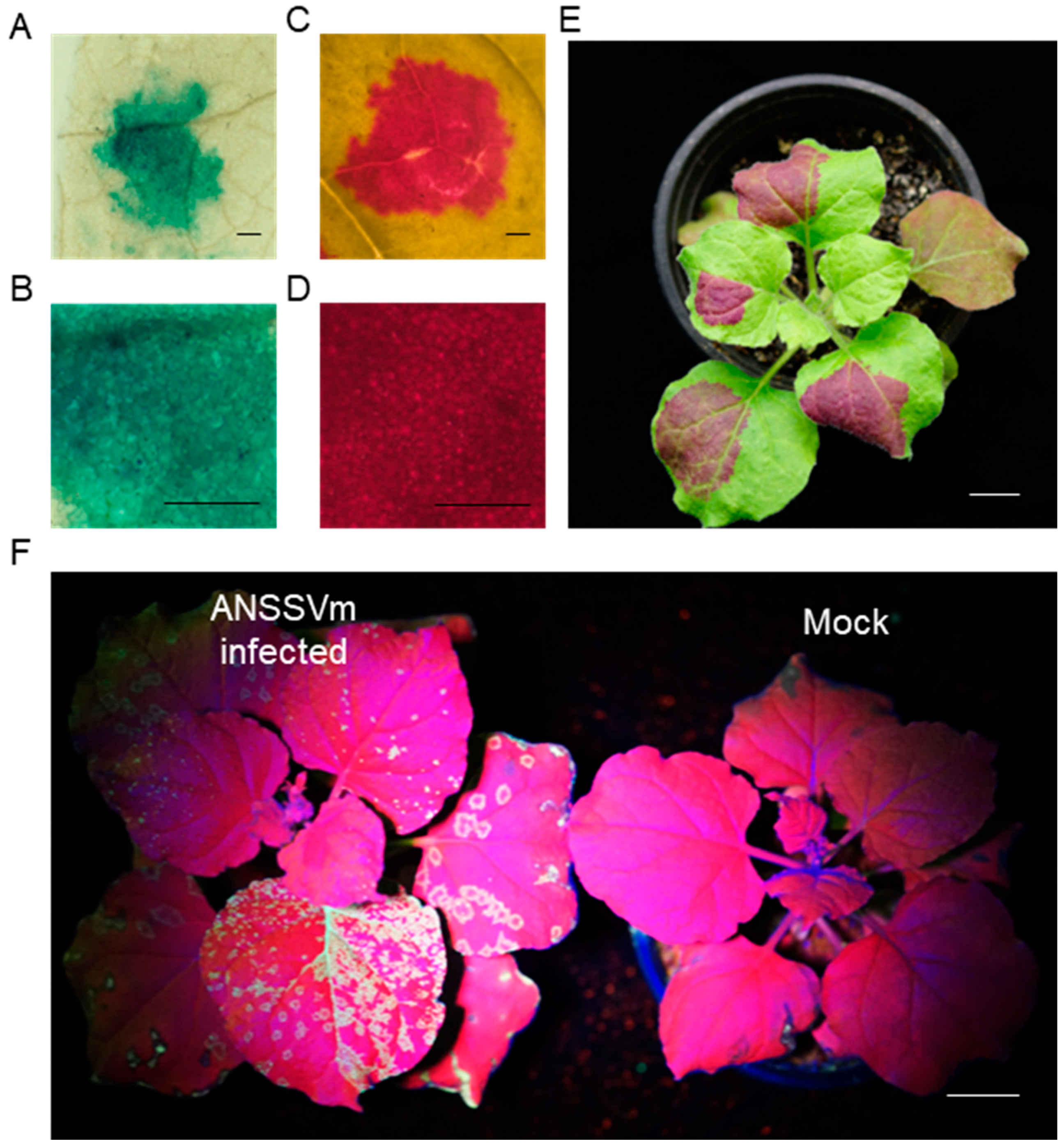

To evaluate the efficiency of foreign gene delivery into areca palm using a gene gun, two universal transient expression vectors, pCambia1301 and 35S::RUBY [29, 30], were selected (Fig. 1A and 1B). Additionally, a GFP-labeled infectious clone of the Areca palm necrotic spindle-spot virus (ANSSVm) isolate was constructed (35S::ANSSVm-GFP) (Fig. 1C). Before delivery in areca palm, the three vectors were first introduced into N. benthamiana via agroinfiltration. Leaves infiltrated with pCambia1301 were treated with X-Gluc substrate, and chlorophyll was removed using 75% ethanol. At 3 days post-inoculation (dpi), significant blue staining was observed in the infiltrated areas (Fig. 2A and 2B). Red pigmentation appeared in N. benthamiana leaves infiltrated with the 35S::RUBY plasmid at 4 dpi (Fig. 2C and 2D) and became more prominent by 10 dpi (Fig. 2E). Following agroinfiltration of 35S::ANSSVm-GFP, green fluorescent spots were observed in systemic leaves of N. benthamiana at 23 dpi (Fig. 2F). These results confirm that all three vectors were successfully and transiently expressed in N. benthamiana through agroinfiltration, and the ANSSVm-GFP infectious clone demonstrated systemic infection following localized agroinfiltration.

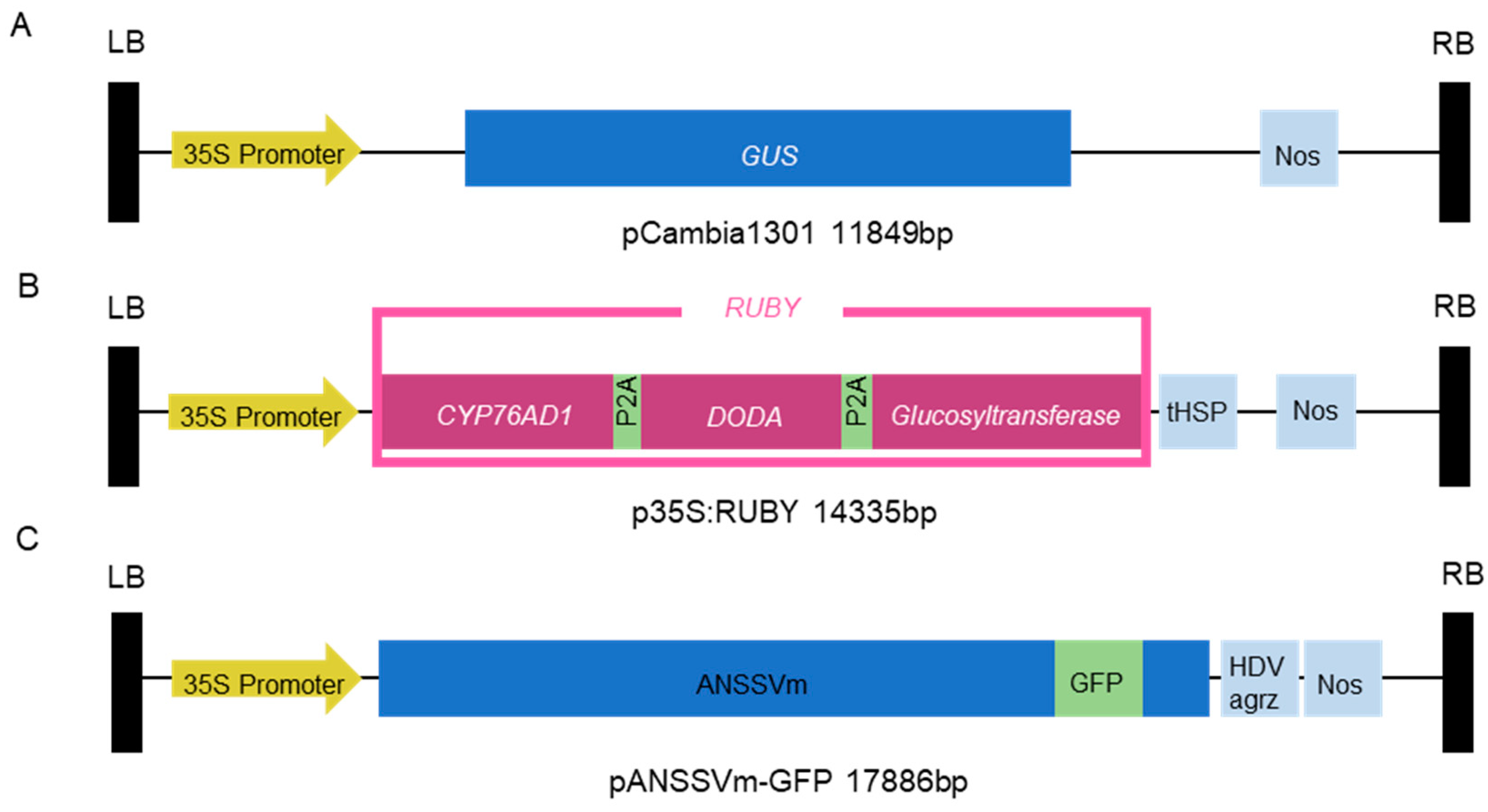

Figure 1.

Schematics of the vector constructs used for micropaticle bombardment. (A) Structure of pCambia1301 vector; (B) Structure of p35S:RUBY. CaMV 35S promoter driving three betalain biosynthetic genes CYP76AD1, DODA and Glucosyltransferase were linked with ‘self-cleaving’ 2A peptides with Arabidopsis HSP18.2 terminator. (C) Structure of pANSSVm-GFP, 17886bp. The expression cassette of full-length ANSSVm genomic RNA is integrated into a mini-binary vector pCB301 backbone. GFP (green fluorescent protein) sequence was inserted at the junction of the NIb protein and the CP protein.

Figure 1.

Schematics of the vector constructs used for micropaticle bombardment. (A) Structure of pCambia1301 vector; (B) Structure of p35S:RUBY. CaMV 35S promoter driving three betalain biosynthetic genes CYP76AD1, DODA and Glucosyltransferase were linked with ‘self-cleaving’ 2A peptides with Arabidopsis HSP18.2 terminator. (C) Structure of pANSSVm-GFP, 17886bp. The expression cassette of full-length ANSSVm genomic RNA is integrated into a mini-binary vector pCB301 backbone. GFP (green fluorescent protein) sequence was inserted at the junction of the NIb protein and the CP protein.

Figure 2.

Transformation of pCambia1301, 35S::RUBY and 35S::ANSSVm-GFP in N. benthamiana through agroinfiltration.GUS expressing on leaves of N. benthamiana infiltrated with pCambia1301 at 3dpi, the leaf was treated with X-Gluc and decolorized with absolute ethanol (A, B). Expression of RUBY on N. benthamiana leaves infiltrated with 35S::RUBY at 3dpi (C, D) and at 10 dpi (E). GFP fluorescence on N. benthamiana infiltrated with 35S::ANSSVm-GFP at 23dpi (F).

Figure 2.

Transformation of pCambia1301, 35S::RUBY and 35S::ANSSVm-GFP in N. benthamiana through agroinfiltration.GUS expressing on leaves of N. benthamiana infiltrated with pCambia1301 at 3dpi, the leaf was treated with X-Gluc and decolorized with absolute ethanol (A, B). Expression of RUBY on N. benthamiana leaves infiltrated with 35S::RUBY at 3dpi (C, D) and at 10 dpi (E). GFP fluorescence on N. benthamiana infiltrated with 35S::ANSSVm-GFP at 23dpi (F).

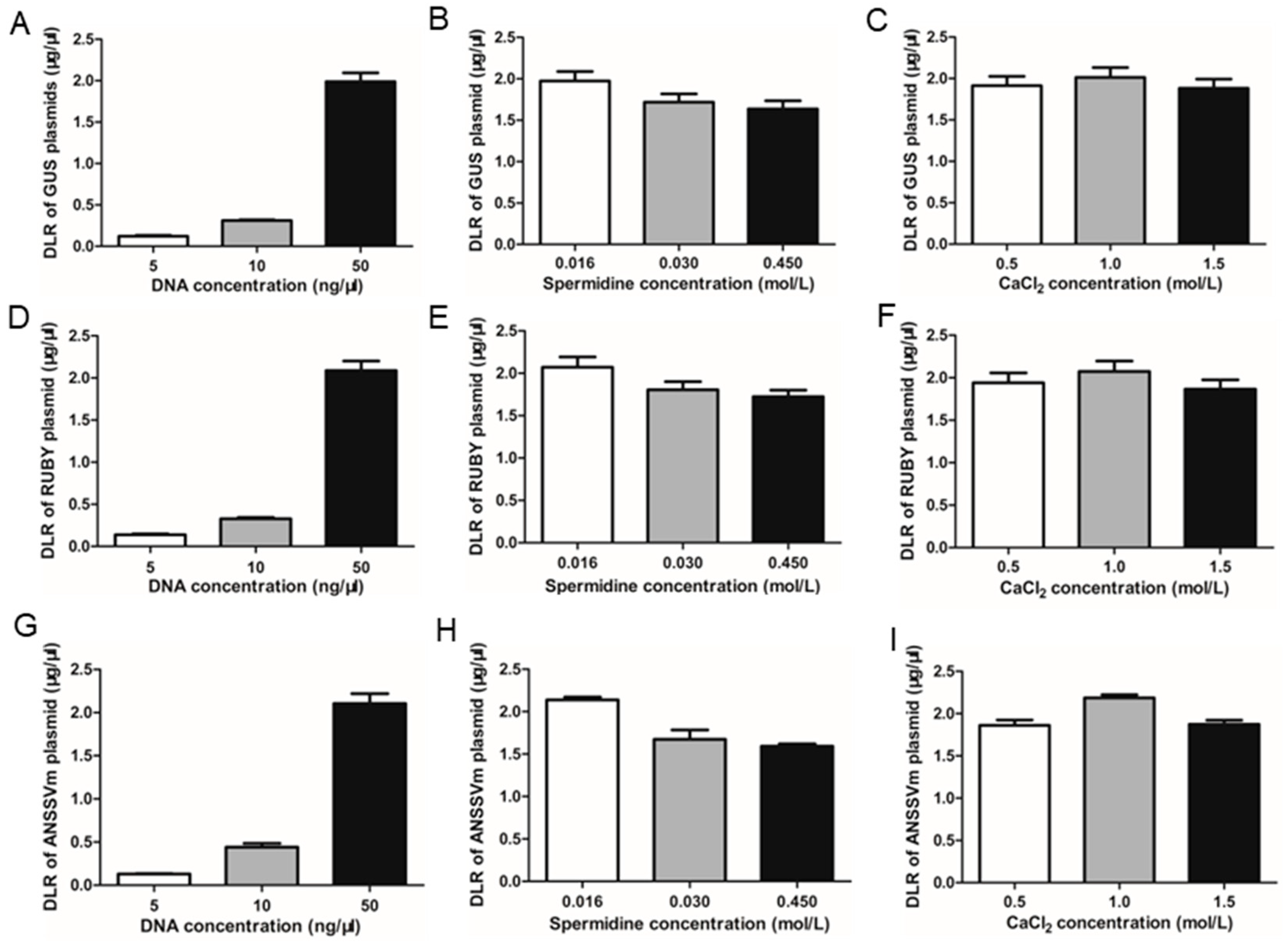

Optimization of DNA Loading Ratio (DLR) Conditions

To enhance DNA loading efficiency (DLR) in the gold particle adsorption system, three critical parameters—DNA concentration, spermidine concentration, and CaCl₂ concentration—were optimized. The results showed that the highest DLR was achieved at a DNA concentration of 50 ng/µL (Fig. 3A, D, G). Increasing DNA concentration beyond this level led to gold particle aggregation and precipitation, causing uneven distribution of particles in the gene gun cartridge and reducing bombardment efficiency. Similarly, the optimal spermidine concentration was 0.016 mol/L, with a slight decrease in DLR observed at higher concentrations (Fig. 3B, E, H). For CaCl₂, the DLR reached its maximum at a concentration of 1 mol/L (Fig. 3C, F, I). These optimized conditions were consistent across all three tested plasmids: pCAMBIA1301, 35S::RUBY, and 35S::ANSSVm-GFP.

Figure 3.

Optimizing DNA loading ratio (DLR). DLR of pCAMBIA1301 plasmid (A-C), 35S::RUBY plasmid (D-F) and 35S::ANSSVm-GFP plasmid (G-I) in different DNA concentration, different spermidine concentration, different CaCl2 concentration.

Figure 3.

Optimizing DNA loading ratio (DLR). DLR of pCAMBIA1301 plasmid (A-C), 35S::RUBY plasmid (D-F) and 35S::ANSSVm-GFP plasmid (G-I) in different DNA concentration, different spermidine concentration, different CaCl2 concentration.

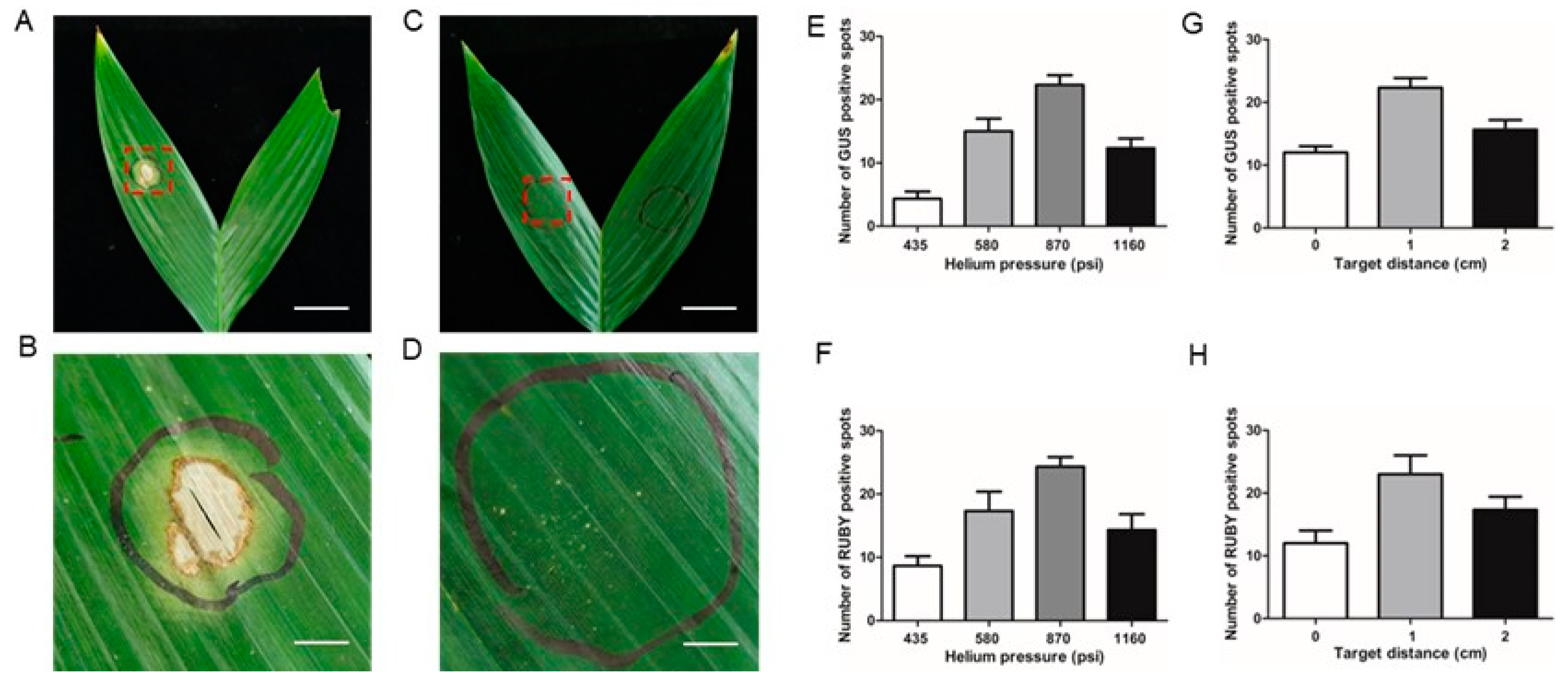

Optimization of Gene Delivery Parameters for Areca Palm Using a Gene Gun

To improve gene delivery efficiency into areca palm leaves via a gene gun, two critical parameters—bombardment pressure and the distance between the gene gun nozzle and the target tissue—were systematically optimized. Efficiency was evaluated by counting GUS-expressing blue spots and RUBY-expressing red spots on bombarded leaves. At a fixed bombardment distance of 1 cm, the highest number of GUS blue spots (21–24 spots) was observed at a pressure of 870 psi (Fig. 4E), while RUBY red spots peaked at 23–26 spots under the same pressure (Fig. 4F). When the pressure was kept constant at 870 psi, reducing the bombardment distance to 0 cm resulted in severe tissue damage compared to the optimal distance of 1 cm (Figs. 4A–D). Conversely, increasing the bombardment distance to 2 cm significantly reduced the number of GUS blue spots and RUBY red spots compared to the optimal 1 cm distance (Figs. 4G, H). These results indicate that a bombardment pressure of 870 psi and a nozzle-to-target distance of 1 cm are optimal for efficient and minimally damaging gene delivery into areca palm leaves using a gene gun.

Figure 4.

Optimizing helium pressures and bombardment distances. (A-D) Damage to areca palm leaves post-bombardment, (A, B)1160 psi and 0 cm, (C, D) 870 psi and 1 cm, bar=2 cm; (B, D) amplification of bombardment area, bar=2 mm. (E,F) Number of GUS-positive infection sites and RUBY-positive infection sites observed under different pressures; (G,H) number of GUS-positive infection sites and RUBY-positive observed under different bombardment distances.

Figure 4.

Optimizing helium pressures and bombardment distances. (A-D) Damage to areca palm leaves post-bombardment, (A, B)1160 psi and 0 cm, (C, D) 870 psi and 1 cm, bar=2 cm; (B, D) amplification of bombardment area, bar=2 mm. (E,F) Number of GUS-positive infection sites and RUBY-positive infection sites observed under different pressures; (G,H) number of GUS-positive infection sites and RUBY-positive observed under different bombardment distances.

Expression of Reporter Genes Post-Bombardment in Areca Palm

To evaluate reporter gene expression in areca palm leaves following gene gun bombardment, stereomicroscopy was employed. Four days after bombardment with pCambia1301, blue spots were observed in the bombarded regions under stereomicroscopy, indicating successful GUS expression in areca palm cells (

Figure 5A, B). Gold particles were visible near clusters of blue-stained cells at higher magnification (

Figure 5C), consistent with the observation in bombarded

N. benthamiana leaves (data not shown). RT-PCR analysis further confirmed GUS expression in areca palm cells (

Figure 5D).

Similarly, four days after bombardment with the 35S::RUBY plasmid, red spots appeared in the bombarded areas after decolorization, confirming successful RUBY expression (

Figure 6A, B). Higher magnification revealed gold particles near red-stained cell clusters (

Figure 6C). RT-PCR analysis corroborated RUBY expression in areca palm cells (

Figure 6D). These findings demonstrate the successful delivery and expression of

GUS and

RUBY genes, validating gene gun bombardment as an effective method for genetic transformation in areca palm leaves.

Discussion

Areca palm (Areca catechu L.) is severely infected by yellow leaf disease (YLD), causing significant yield reduction and substantial economic losses [2, 3]. Areca palm velarivirus 1 (APV1) has been proven to be the causal agent of YLD. There is urgent need to develop virus-resistant varieties through genetic engineering due to the absence of resistant cultivars. Both Agrobacterium-mediated transformation and transient expression has not achieved in areca palm. The aim of this study is to achieve transient expression of exogenous genes and to establish VIGS in areca palm.

VIGS have been successfully utilized to investigate gene functions in many woody plants, such as the

Prunus necrotic ringspot virus (PNRSV)-based vector in plum [

27] and

Apple latent spherical virus (ALSV)-based vectors in apple [

28]. Plum necrotic ringspot virus (PNRSV) has been used to silence the

ef4E gene in plum, conferring resistance to Plum pox virus (PPV). However, in palm species, the TRV-based VIGS vector has only been successfully used to transform callus tissue of oil palm (

Elaeis guineensis) and GFP reporter gene was expressed in protoplast of areca palm [31, 32]. Furthermore, the VIGS-transformed callus tissue often browns and dies quickly, hindering further development into mature plants. There has been no report that the VIGS has successfully infected areca palm seedlings so far. In this work, exogenous gene was first reported to transiently expressed in areca palm leaves through microparticle bombardment, laying a foundation for establishment of VIGS in areca palm.

In order to establish VIGS in areca palm, we have tried to identify latent viruses hosted areca palm, leading to identification of areca palm latent totivirus 1 (APLTV1) [

33]. However, the construction of infectious clone for APLTV1 has not succeeded. Recently, we identified a mild isolate ANSSVm in areca palm. In this work, GFP-labelled infectious clone (35S::ANSSVm-GFP) was constructed and successfully achieved systemic infection in

N. benthamiana (

Figure 2F). The infected

N. benthamiana did not show any virus disease symptoms, indicating that it is a good candidate for VIGS vector for areca palm. Unfortunately, 35S::ANSSVm-GFP vectors was not transferred into areca palm through microparticle bombardment. A possible reason is that the size of the plasmid has limited the transform of the vector into nucleus.

Another reason for the failure of ANSSVm-GFP transformation appears to be the insufficient number of infection foci. Successful systemic infection and high replication within the host plant require a substantial number of infection foci at the initial stage [34-37]. To address these challenges, two feasible strategies are proposed. First, the third-generation hand-held gene gun, the GDS-80 (Wealtec corp), could be utilized with the optimized parameters established in this study [

38]. Unlike Helios gene gun, GDS-80 gene gun eliminates the need for cumbersome cartridge preparation by directly injecting a gold particle–plasmid suspension, thereby reducing gold particle loss. Furthermore, its Laval-effect-based barrel design minimizes damage to the leaves caused by bombardment pressure. Theoretically, the third-generation handheld gene gun offers higher transformation efficiency, making it better suited for bombarding areca palm leaves. Second, the plasmid could be replaced with ANSSVm viral particles extracted from infected

N. benthamiana, combined with gold particles. While plasmid bombardment requires delivery of DNA into the nucleus for expression, ANSSVm, being an RNA virus, only needs to reach the cytoplasm to replicate and express viral proteins [

38]. This approach could significantly improve the likelihood of successful transformation in areca palm leaves.

This study optimized key parameters for gene gun bombardment, successfully expressing exogenous GUS and RUBY in areca palm leaves. The infectious clone of the mild isolate ANSSVm was constructed and effectively transferred into N. benthamiana, causing systemic infection. Although the transformation of ANSSVm-GFP in areca palm was not achieved, this study established a reliable method for foreign gene expression, providing a foundation for developing a VIGS system in areca palm. This advancement holds significant potential for gene characterization and breeding disease-resistant areca palm varieties.

Materials and Methods

Construction of Infectious cDNA Clones

The GFP-tagged infectious cDNA clones of ANSSVm were constructed basically following the design of the reported GFP expression vector of ANSSV-HNBT [

14]. Overlap PCR [

39] was employed to insert the intron 2 of the

NIR gene of

Phaseolus vulgaris (

PvNIR, GenBank U10419) into the P3-coding region to generate a large PCR product of 3.9 kb covering the 5’-terminal region. This chimeric PCR product containing the 1st and 2nd viral fragments and the

PvNIR intron, two other viral sequences (the 3rd and 4th viral fragments), the GFP coding sequence and the vector backbone (digested by

StuI and

SmaI) were assembled into the full-length clone via recombination-based one-step assembly (Vazyme, China). The final constructs were preliminarily verified by restriction enzyme digestion with

HindIII that had seven recognition sites in the consensus genome of ANSSVm, and further identified by next generation sequencing of the plasmids (Sangon Biotech, China).

Plant Materials for Bombarded

Areca catechu L. seedlings used in this study were cultivated from seeds purchased in Danzhou, Hainan, and grown in our laboratory. The seedlings were planted in nutrient soil and maintained under controlled conditions at 30°C with a 14-hour light/10-hour dark photoperiod for approximately three months. Fully expanded leaves from the upper-middle sections of the plants were harvested for gene gun transformation experiments.

N. benthamiana L. wild-type seeds, preserved in our laboratory, were sown in nutrient soil and grown under controlled conditions at 25°C with a 16-hour light/8-hour dark photoperiod for about one month. Fully expanded leaves from the upper-middle sections of these plants were collected for Agrobacterium-mediated infection and gene gun transformation experiments.

Preparation of Cartridges and Gene Gun Bombardment

Gold particles were suspended in 50% glycerol to prepare a suspension. A 100 μL aliquot of the suspension was placed in a centrifuge tube (one tube can be used for up to 10 shots; for larger sample sizes, the suspension was divided into smaller tubes). Using a micropipette, 10-20 μL of plasmid DNA (at a concentration of 1 μg/μL) was added along the wall of the tube, and the mixture was vortexed for 30 seconds. Next, 40 μL of spermidine (0.1 M) was added along the wall, followed by vortexing for another 30 seconds. Afterward, 100 μL of CaCl₂ solution (2.5 M) was added while vortexing for 30 seconds to 1 minute. The mixture was allowed to stand for 1 minute, and then the gold particles were transferred to a new siliconized centrifuge tube. The mixture was centrifuged, and the supernatant was discarded.

Subsequently, 300 μL of 70% ethanol was added, and the precipitate was gently tapped (without vortexing) to ensure even dispersion. After centrifuging and discarding the supernatant, anhydrous ethanol was added, and the mixture was centrifuged again to remove the supernatant. This washing process was repeated, first with 300 μL of anhydrous ethanol, and then with 120 μL of anhydrous ethanol to resuspend the gold particles. If the suspension dispersed well, the gold particles were transferred into prepared cartridges for gene gun bombardment. Gene gun bombardment was performed using the Helios genegun system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), following the Helios Gene Gun System Instruction Manual.

GUS Staining and RUBY Treatment in Areca Palm

After gene gun bombardment, the bombarded areca palm leaves were cultured for 3 days before being subjected to GUS staining. The leaves were incubated in the GUS staining solution at 37°C for 4–8 hours, then decolorized in absolute ethanol to remove chlorophyll[

40]. Blue staining indicative of GUS activity was observed under a stereomicroscope (OLYMPUS SZX16) at 2× magnification. The number of blue spots at the bombardment sites was counted, and at higher magnification, gold particles that had entered the areca palm cells could also be visualized.

For RUBY expression, after 4 days of cultivation post-bombardment, the areca palm leaves were decolorized in absolute ethanol and examined under a stereomicroscope (OLYMPUS SZX16) at 2× magnification. Red spots, indicative of RUBY expression, were visible, and the number of red spots at the bombardment sites was recorded. Each experiment included 10 leaves per treatment, with two bombardment sites on each leaf. The experiment was repeated three times to ensure consistency. This approach allowed us to evaluate the transient expression efficiency of both GUS and RUBY reporter genes in the areca palm cells.

Fluorescence Observation of N.benthamiana Post-ANSSVm-GFP Inoculation

On the 23 dpi with ANSSVm-GFP, fluorescence was observed using a hand-held strong blue light (450 nm) flashlight (LUYOR-3260RB, LuYor Instruments Co., USA) as the excitation source. The leaves were directly observed in a darkroom under illumination, and images were captured using a Sony α6000 DSLR camera in combination with the LUV-520A filter provided by LuYor Instruments. This setup allowed for the visualization and documentation of GFP fluorescence in the injected leaves.

RT-PCR and Western Blot (WB) Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the gene gun-bombarded areca palm leaves using the plant total RNA purification kit (for polysaccharide- and polyphenol-rich samples, #DP441) from TianGen Biotech (Beijing, China), following the manufacturer's protocol. The RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (#K1622) from Thermo Fisher Scientific (China), following the provided instructions. The cDNA was subsequently analyzed using specific primers for detection (

Table S1). For Western blot analysis, GFP expression in the bombarded areca palm leaves was assessed. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Immunodetection was performed using the appropriate primary antibodies [

37]. Chemiluminescent signals were detected using the SuperSignal™ West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate Kit (Thermo Fisher, Product #34579), and the images were captured with the Molecular Imager Gel Doc™ XR System (Bio-Rad, Product #170-81703). All primers used in this study were synthesized by Qingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Hainan, China).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

X.H. and J.Z conceived and designed the experiments; H.T. and H.Z. performed experiments; R.Z. helped with data interpretation; H. T. wrote the manuscript; J.Z. and X.H. revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by Hainan Key Research and Development Plan Foundation (ZDYF2024XDNY208) and the earmarked fund for Agriculture Research System in Hainan Province (Grant No. HNARS-1-G4-1).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical Standards

This article does not contain any research involving human or animal participants.

References

- Ding, H.; Zhou, G.; Zhao, L.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Xia, C.; Xia, Z.; Wan, Y. , Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Fruit Shape-Related Traits in Areca catechu. International journal of molecular sciences. [CrossRef]

- Khan, L. U.; Zhao, R.; Wang, H.; Huang, X. , Recent advances of the causal agent of yellow leaf disease (YLD) on areca palm (Areca catechu L.). Tropical Plants. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, H.; Cao, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhai, J.; Huang, X. , Prevalence of yellow leaf disease (YLD) and its associated areca palm velarivirus 1 (APV1) in betel palm (Areca catechu) plantations in Hainan, China. Plant Dis 2020, 104(10), 2556–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Gou, B.; Hu, W.; Qin, L.; Shen, W.; Wang, A.; Cui, H.; Dai, Z. , Direct leaf-peeling method for areca protoplasts: a simple and efficient system for protoplast isolation and transformation in areca palm (Areca catechu). BMC plant biology 2023, 23(1), 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, Q. T.; Bandupriya, H. D.; López-Villalobos, A.; Sisunandar, S.; Foale, M.; Adkins, S. W. , Tissue culture and associated biotechnological interventions for the improvement of coconut (Cocos nucifera L.): a review. Planta, 2015; 242, 1059–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baulcombe, D. C. , VIGS, HIGS and FIGS: small RNA silencing in the interactions of viruses or filamentous organisms with their plant hosts. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2015, 26, 141–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch-Smith, T. M.; Anderson, J. C.; Martin, G. B.; Dinesh-Kumar, S. P. , Applications and advantages of virus-induced gene silencing for gene function studies in plants. Plant J 2004, 39(5), 734–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhu, M.; Liu, W.; Jahan, M. S.; Gu, Q.; Shu, S.; Sun, J.; Guo, S. , CsPAO2 Improves Salt Tolerance of Cucumber through the Interaction with CsPSA3 by Affecting Photosynthesis and Polyamine Conversion. Int J Mol Sci. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ellison, E. E.; Myers, E. A.; Donahue, L. I.; Xuan, S.; Swanson, R.; Qi, S.; Prichard, L. E.; Starker, C. G.; Voytas, D. F. , Heritable gene editing in tomato through viral delivery of isopentenyl transferase and single-guide RNAs to latent axillary meristematic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121(39), e2406486121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajeri, S.; Killiny, N.; El-Mohtar, C.; Dawson, W. O.; Gowda, S. , Citrus tristeza virus-based RNAi in citrus plants induces gene silencing in Diaphorina citri, a phloem-sap sucking insect vector of citrus greening disease (Huanglongbing). Journal of biotechnology 2014, 176, 42–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamagishi, N.; Yoshikawa, N. , Highly efficient virus-induced gene silencing in apple and soybean by apple latent spherical virus vector and biolistic inoculation. Methods in molecular biology 2013, 975, 167–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Sun, J.; Yao, J.; Wang, S.; Ding, M.; Zhang, H.; Qian, Z.; Zhao, N.; Sa, G.; Zhao, R.; Shen, X.; Polle, A.; Chen, S. , High rates of virus-induced gene silencing by tobacco rattle virus in Populus. Tree Physiol 2015, 35(9), 1016–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taki, A.; Yamagishi, N.; Yoshikawa, N. , Development of apple latent spherical virus-based vaccines against three tospoviruses. Virus research, 2013; 176, 251–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Shen, W.; Tang, Z.; Hu, W.; Shangguan, L.; Wang, Y.; Tuo, D.; Li, Z.; Miao, W.; Valli, A. A.; Wang, A.; Cui, H. , A Newly Identified Virus in the Family Potyviridae Encodes Two Leader Cysteine Proteases in Tandem That Evolved Contrasting RNA Silencing Suppression Functions. J Virol, 2020; 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Ran, M.; Li, Z.; Hu, M.; Zheng, L.; Liu, W.; Jin, P.; Miao, W.; Zhou, P.; Shen, W.; Cui, H. , Analysis of the complete genomic sequence of a novel virus, areca palm necrotic spindle-spot virus, reveals the existence of a new genus in the family Potyviridae. Arch Virol 2018, 163(12), 3471–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Ran, M.; Li, Z.; Hu, M.; Zheng, L.; Liu, W.; Jin, P.; Miao, W.; Zhou, P.; Shen, W.; Cui, H. , Correction to: Analysis of the complete genomic sequence of a novel virus, areca palm necrotic spindle-spot virus, reveals the existence of a new genus in the family Potyviridae. Arch Virol 2018, 163(12), 3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, W.; Dai, Z.; Gou, B.; Liu, H.; Hu, W.; Qin, L.; Li, Z.; Tuo, D.; Cui, H. , Biological and Molecular Characterization of Two Closely Related Arepaviruses and Their Antagonistic Interaction in Nicotiana benthamiana. Frontiers in microbiology 2021, 12, 755156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Yan, H.; Song, L.; Jin, P.; Miao, W.; Cui, H. , Correction to: Analysis of the complete genome sequence of a potyvirus from passion fruit suggests its taxonomic classification as a member of a new species. Arch Virol 2021, 166(1), 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, L.; Liu, H.; Liu, P.; Jiang, L.; Cheng, X.; Li, F.; Shen, W.; Qiu, W.; Dai, Z.; Cui, H. , Rubisco small subunit (RbCS) is co-opted by potyvirids as the scaffold protein in assembling a complex for viral intercellular movement. PLoS Pathog 2024, 20(3), e1012064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Moscou, M. J.; Wise, R. P. , Blufensin1 negatively impacts basal defense in response to barley powdery mildew. Plant Physiol 2009, 149(1), 271–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoengenaert, L.; Van Doorsselaere, J.; Vanholme, R.; Boerjan, W. , Microparticle-mediated CRISPR DNA delivery for genome editing in poplar. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1286663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Brien, J. A.; Holt, M.; Whiteside, G.; Lummis, S. C.; Hastings, M. H. , Modifications to the hand-held Gene Gun: improvements for in vitro biolistic transfection of organotypic neuronal tissue. J Neurosci Methods 2001, 112(1), 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, A.; El-Mochtar, C.; Wang, C.; Goodin, M.; Orbovic, V. , A new toolset for protein expression and subcellular localization studies in citrus and its application to citrus tristeza virus proteins. Plant Methods 2018, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K.; Kikuchi, T.; Kasajima, I.; Li, C.; Yamagishi, N.; Yamashita, H.; Yoshikawa, N. , Virus-Induced Flowering by Apple Latent Spherical Virus Vector: Effective Use to Accelerate Breeding of Grapevine. Viruses, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsono, N.; Yoshida, T. , Transient Expression of Green Fluorescent Protein in Rice Calluses : Optimization of Parameters for Helios Gene Gun Device. Plant Production Science 2015, 11(1), 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acanda, Y.; Wang, C.; Levy, A. , Gene Expression in Citrus Plant Cells Using Helios(®) Gene Gun System for Particle Bombardment. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.). [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Wang, A. , An efficient viral vector for functional genomic studies of Prunus fruit trees and its induced resistance to Plum pox virus via silencing of a host factor gene. Plant biotechnology journal 2017, 15(3), 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Sasaki, N.; Isogai, M.; Yoshikawa, N. , Stable expression of foreign proteins in herbaceous and apple plants using Apple latent spherical virus RNA2 vectors. Arch Virol 2004, 149(8), 1541–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, T.; Sun, H.; Zhan, H.; Zhao, Y. , A reporter for noninvasively monitoring gene expression and plant transformation. Horticulture research 2020, 7(1), 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhong, Y.; Feng, B.; Qi, X.; Yan, T.; Liu, J.; Guo, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, S.; Pan, R.; Liu, C.; Chen, S. , The RUBY reporter enables efficient haploid identification in maize and tomato. Plant Biotechnol J 2023, 21(8), 1707–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xingqi, Y.; Zijia, L.; Yu, L.; Jixin, Z.; Yusheng, Z.; Dongdong, L. , Construction and optimization of the TRV-mediated VIGS system in Areca catechu embryoids. Scientia Horticulturae 2024, 338, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, J.; Yang, M.; Zou, J.; Zheng, Y.; Li, D. , EgMADS3 directly regulates EgLPAAT to mediate medium-chain fatty acids (MCFA) anabolism in the mesocarp of oil palm. Plant Cell Rep 2024, 43(4), 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, H.; Zhao, R.; Wang, H.; Huang, X. , Identification and molecular characterization of a novel member of the genus Totivirus from Areca catechu L. Arch Virol 2023, 168(10), 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maule, A. J.; Caranta, C.; Boulton, M. I. , Sources of natural resistance to plant viruses: status and prospects. Mol Plant Pathol 2007, 8(2), 223–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soosaar, J. L.; Burch-Smith, T. M.; Dinesh-Kumar, S. P. , Mechanisms of plant resistance to viruses. Nature reviews. Microbiology 2005, 3(10), 789–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Du, S.; Wang, K.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, R.; Bruening, G.; Wang, P.; Duanmu, D.; Fan, Q. , Cowpea lipid transfer protein 1 regulates plant defense by inhibiting the cysteine protease of cowpea mosaic virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121(35), e2403424121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Hu, R.; Pi, Q.; Zhang, D.; Duan, J.; Li, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhao, X.; Yang, M.; Zhao, X.; Liu, D.; Su, Z.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y. , DEAD-box RNA helicase RH20 positively regulates RNAi-based antiviral immunity in plants by associating with SGS3/RDR6 bodies. Plant Biotechnol J 2024, 22(12), 3295–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, A. , Biolistic Inoculation of Fruit Trees with Full-Length Infectious cDNA Clones of RNA Viruses. Methods Mol Biol 2022, 2400, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, R. M.; Hunt, H. D.; Ho, S. N.; Pullen, J. K.; Pease, L. R. , Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene 1989, 77(1), 61–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lao, X.; Jin, P.; Yang, R.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zeng, Y.; Li, X. , Establishment of Agrobacterium-Mediated Transient Transformation System in Desert Legume Eremosparton songoricum (Litv.) Vass. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).