Submitted:

15 September 2025

Posted:

17 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant, Inoculation, and Host Bacterial Materials

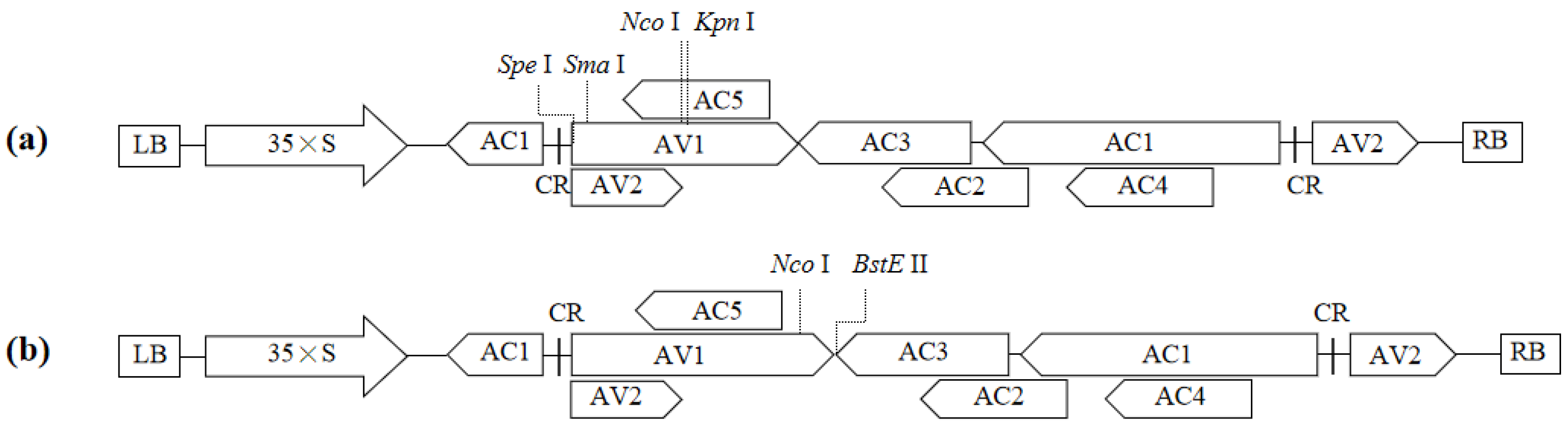

2.2. Design of Target Fragments and Construction of Vacant Vectors

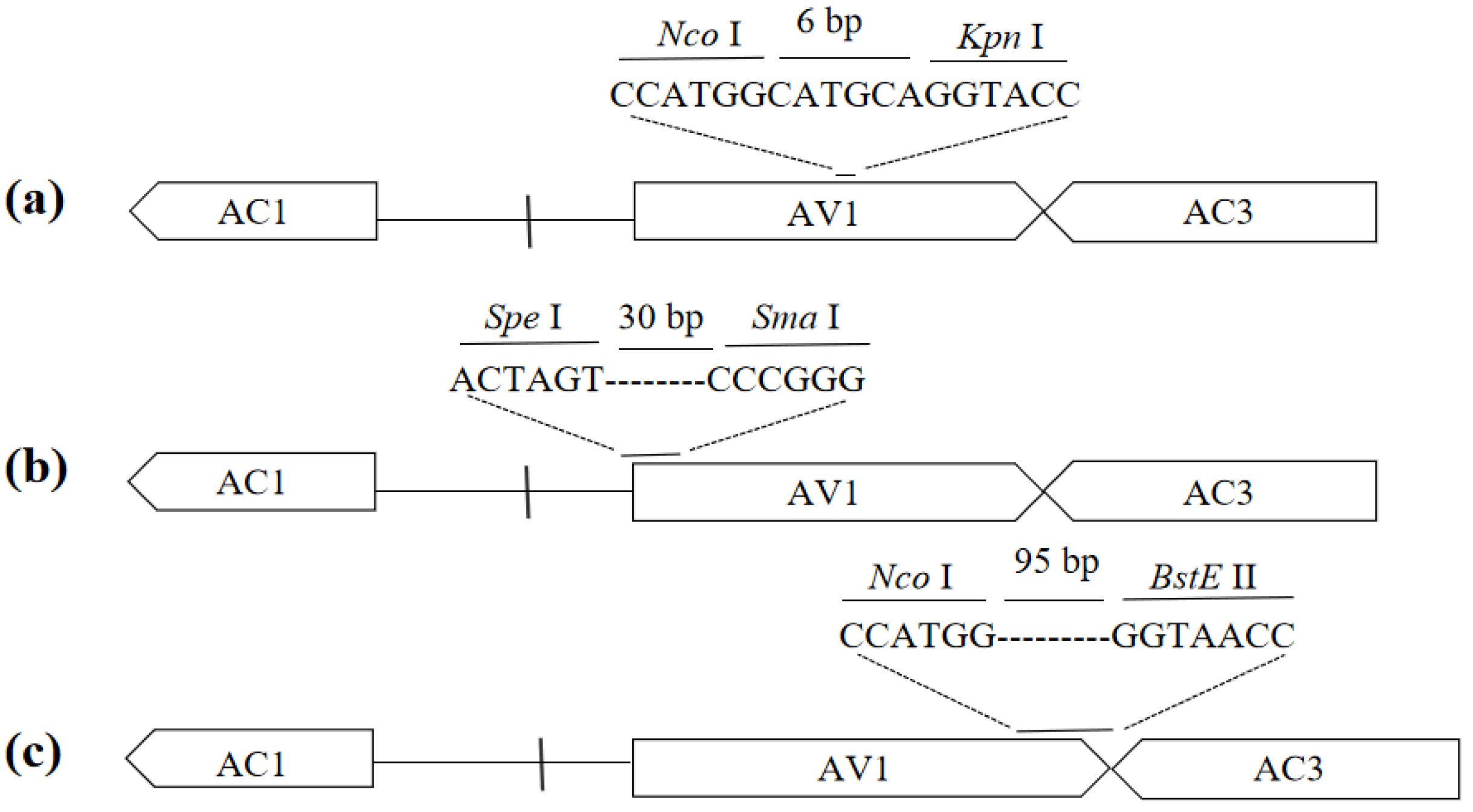

2.3. Construction of ToLCNDV-Based VIGS Vectors

2.3.1. Construction of VIGS Vectors with Different Target Fragment Lengths

2.3.2. Construction of VIGS Vectors with Different Substitution Areas for the CmPDS Fragment

2.3.3. Construction of VIGS Vectors with the Antisense Orientation of CmPDS Fragments

2.4. Agroinfiltration

2.5. Effects of VIGS Vectors on the Phenotypic Traits of Melon Plants

2.6. Effects of VIGS Vectors on PDS Gene Expression in Melon

3. Results

3.1. Design of Target Fragments and Construction of Vacant Vectors

3.2. Construction of ToLCNDV-Based VIGS Vectors

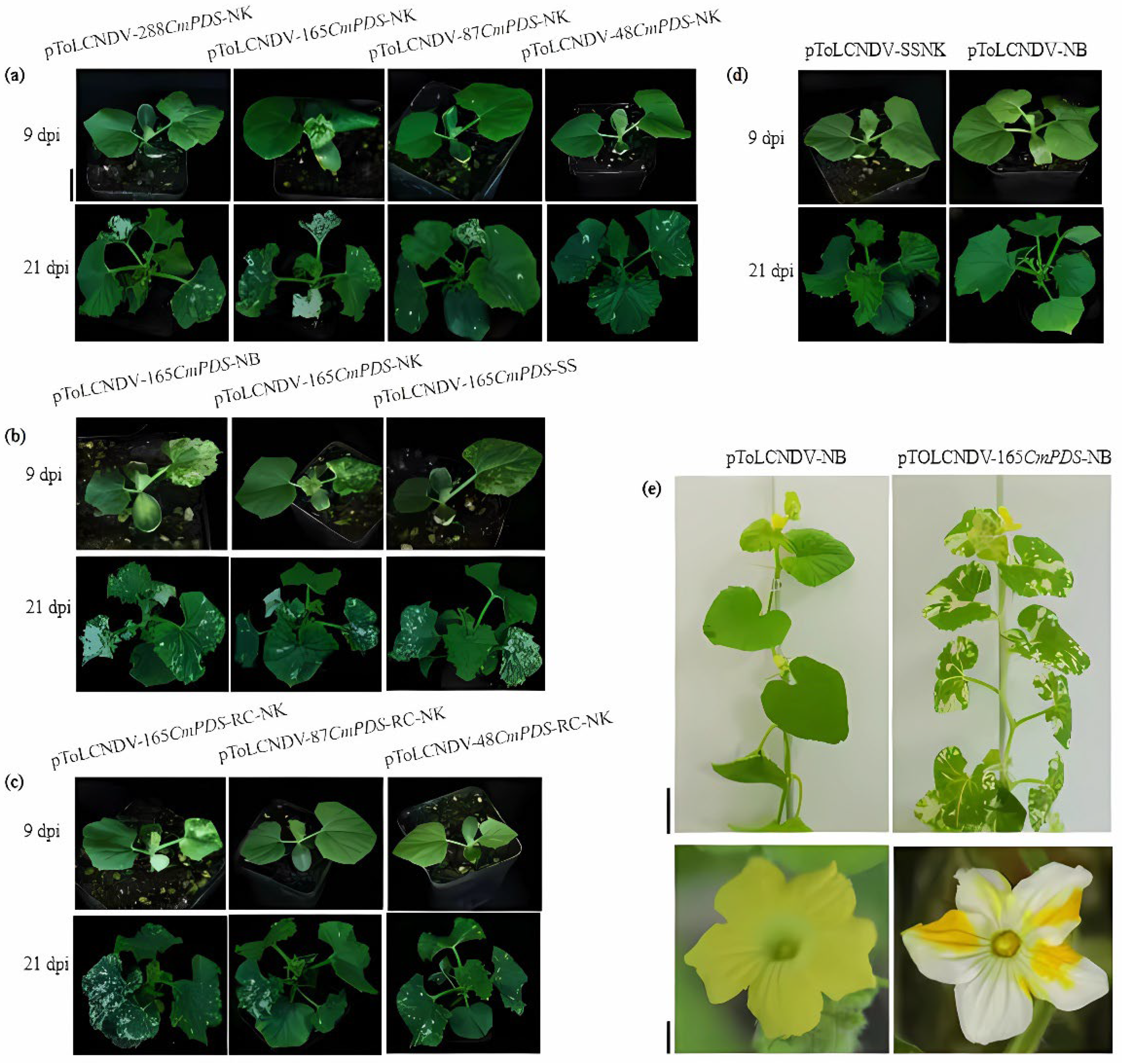

3.3. Effects of VIGS Vectors on Melon Leaf Photobleaching

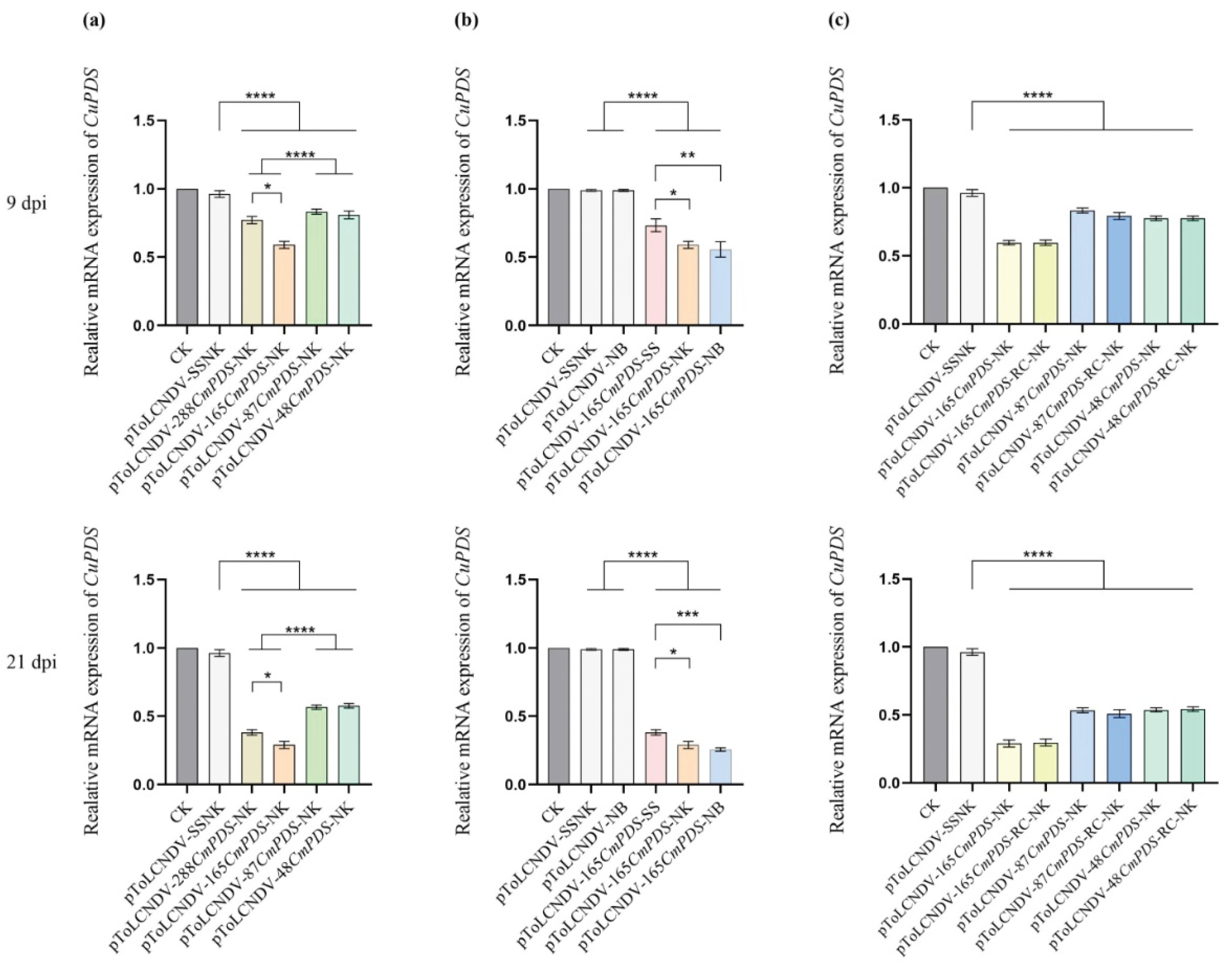

3.4. Influence of VIGS Vectors on PDS Gene Expression in Melon

3.4.1. Silencing Effects of the Length of the CmPDS Fragment

3.4.2. Silencing Effects of the Substitution Area of the CmPDS Fragment

3.4.3. Silencing Effects of CmPDS Fragments in the Antisense Orientation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Target fragment | Sequences(5’→3’) | Restriction Enzymes at the 5’ end |

Restriction Enzymes at the 3’ end |

Inserting position Within AV1gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 288CmPDS-NK | atggcgttttggggtagtgagattgtgggcgatgggttgaaagtatctggcagacatgttagtaggaaactgtataagggagctataccactgaagatagtttgtgtggattaccctagaccacagatagatgatacagttaatttcattgaagcagcttccatatctgctagttttcgtgcttctgcacgtcccaggaagccattgaaagtagtgattgctggggcaggattggctggtatatcgacagcaaaatatttggcagatgctggccacaaacctgttcat | Nco I | Kpn I | middle |

| 165CmPDS-NK | atggcgttttggggtagtgtgttagtaggaaactgtataagggagctataccactgaagatagtttgtgtggattaccctagaccacagatagatgatacagttaatttcattgaagcagcttccata | Nco I | Kpn I | middle |

| 87CmPDS-NK | gcgttttggggtagtgagattgtgggcgatgggttgaaagtatctggcagacatgttagtaggaaactgtataagggagctata | Nco I | Kpn I | middle |

| 48CmPDS-NK | gcgttttggggtagtgagattgtgggcgatgggttgaaagtatctggc | Nco I | Kpn I | middle |

| 165CmPDS-NB | cttcgcacctgcagaagagtggatttctcggagtgactcggacattattgatgcgacaatggtggaactagctaaactatttcctgatgaaatttctgctgatcagagcaaagctaagattgtgaagtaccacgttgttaaaaccccaaggtcg | Nco I | BstE II | 3’ end |

| 165CmPDS-SS | atggcgttttggggtagtgagattgtgggcgatgggttgaaagtatctggcagacatgttagtaggaaactgtataagggagctataccactgaagatagtttgtgtggattaccctagaccacagatagatgatacagttaatttcattgaagcagcttccata | Spe I | Sma I | 5’ end |

| 165CmPDS-RC-NK | tatggaagctgcttcaatgaaattaactgtatcatctatctgtggtctagggtaatccacacaaactatcttcagtggtatagctcccttatacagtttcctactaacatgtctgccagatactttcaacccatcgcccacaatctcactaccccaaaacgc | Nco I | Kpn I | middle |

| 87CmPDS-RC-NK | tatagctcccttatacagtttcctactaacatgtctgccagatactttcaacccatcgcccacaatctcactaccccaaaacgc | Nco I | Kpn I | middle |

| 48CmPDS-RC-NK | gccagatactttcaacccatcgcccacaatctcactaccccaaaacgc | Nco I | Kpn I | middle |

References

- Sun, G.Y.; Ju, Y.Q.; Zhang, C.P.; Li, L.L.; Jiang, X.Q.; Xie, X.M.; Lu, Y.Z.; Wang, K.L.; Li, W. Styrax japonicus functional genomics: an efficient virus induced gene silencing (VIGS) system. Horticultural Plant Journal 2024, 10, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rössner, C.; Lotz, D.; Becker, A. VIGS Goes Viral: How VIGS Transforms Our Understanding of Plant Science. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2022, 73, 703–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, S.; Farooq, M.A.; Zhao, T.T.; Wang, P.P.; Tabusam, J.; Wang, Y.H.; Xuan, S.X.; Zhao, J.J.; Chen, X.P.; Shen, S.X.; Gu, A.X. Virus–induced gene silencing(VIGS): a powerful tool for crop improvement and its advancement towards epigenetics. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 5608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisette, M.A.; Neftalí, O. Virus–Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) in Chili Pepper (Capsicum spp.). Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.J.) 2020, 2172, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bu, R.; Wang, R.; Wei, Q.; Hu, H.Y.; Sun, H.L.; Song, P.W.; Yu, Y.A.; Liu, Q.L.; Zheng, Z.C.; Li, T.; Li, D.X.; Wang, L.; Chen, S.J.; Wu, L.L.; Wu, J.Y.; Li, C.W. Silencing of glycerol–3–phosphate acyltransferase 6 (GPAT6) gene using a newly established virus induced gene silencing (VIGS) system in cucumber alleviates autotoxicity mimicked by cinnamic acid (CA). Plant and Soil 2019, 438, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.J.; Wang, C.H.; Xing, Q.J.; Li, Y.P.; Liu, X.F.; Qi, H.Y. Overexpression and VIGS system for functional gene validation in oriental melon (Cucumis melo var. makuwa Makino). Plant Cell. Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2019, 137, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.M.; Lim, S.; Igori, D.; Yoo, R.H.; Kwon, S.; Moon, J.S. Development of tobacco ringspot virus–based vectors for foreign gene expression and virus–induced gene silencing in a variety of plants. Virology 2016, 492, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liang, Z.; Aranda, M.A.; Hong, N.; Liu, L.M.; Kang, B.S. A cucumber green mottle mosaic virus vector for virus–induced gene silencing in cucurbit plants. Plant Methods 2020, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch–Smith, T.M.; Anderson, J.C.; Martin, G.B.; Dinesh–Kumar, S.P. Applications and advantages of virus–induced gene silencing for gene function studies in plants. The Plant Journal 2004, 39, 734–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.S.; Mansoor, S. Viral vectors for plant genome engineering. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Shen, W.X.; Zhu, S.P.; Zhao, X.C. Use of TRV–mediated VIGS for functional genomics research in citrus. Plant Cell. Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2019, 139, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, E.; Holland, J.J. RNA virus mutations and fitness for survival. Annu Rev Microbiol 1997, 51, 151–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fofana, I.B.F.; Sangare, A.; Collier, R.; Taylor, C.; Fauquet, C.M. A geminivirus–induced gene silencing system for gene function validation in cassava. Plant Mol Biol 2004, 56, 613–624.(ACMV). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenz, B.; Wege, C.; Jeske, H. Cell–free construction of disarmed abutilon mosaic virus–based gene silencing vectors. J Virol Methods 2010, 169, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Zhou, X. A modified viral satellite DNA that suppresses gene expression in plants. Plant J 2004, 38, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, J.R.; Idris, A.M.; Brown, J.K.; Haigler, C.H.; Robertson, D. Geminivirus–mediated gene silencing from cotton leaf crumple virus is enhanced by low temperature in cotton. Plant Physiol 2008, 148, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peele, C.; Jordan, C.V.; Muangsan, N.; Turnage, M.; Robertson, D. Silencing of a meristematic gene using geminivirus–derived vectors. Plant J 2010, 27, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyabharathy, C.; Shakila, H.; Usha, R. Development of a VIGS vector based on the beta–satellite DNA associated with bhendi yellow vein mosaic virus. Virus Res 2015, 195, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhao, J.; Xie, K.; Hong, Y.; Liu, Y. Virus–based microRNA expression for gene functional analysis in plants. Plant Physiol 2010, 153, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, J.; Aguado, E.; Martinez, C.; Garcia, A.; Cebrian, C.; Paris, H.S.; Jamilena, M. A novel dominant resistance gene for ToLCNDV in Cucurbita spp. Acta Horticulturae 2020, 1294, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.T.B.; Troiano, E.; Lal, A.; Hoang, P.T.; Kil, E.J.; Lee, S.K.; Parrella, G. ToLCNDV–ES infection in tomato is enhanced by TYLCV: Evidence from field survey and agroinoculation. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 954460–954460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renukadevi, P.; Devi, G.R.; Jothika, C.; Karthikeyan, G.; Malathi, V.G.; Balakrishnan, N.; Rajagopal, B.; Nakkeeran, S.; Abd-Allah, E.F. Genomic distinctiveness and recombination in tomato leaf curl New Delhi virus (ToLCNDV–BG) isolates infecting bitter gourd. 3 Biotech 2024, 14, 184–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, C.; Manzano, S.; Megias, Z.; Garcia, A.; Garrido, R.; Paris, H.S.; Jamilena, M. Screening of Cucurbita germplasm for ToLCNDV resistance under natural greenhouse conditions. Acta Horticulturae 2017, 1151, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveena, E.; Rajasree, V.; Behara, T.K.; Karthikeyan, G.; Kavitha, M.; Rameshkumar, D. Molecular confirmation of ToLCNDV resistance in cucumber through agroinoculation and field screening. Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences–Japs 2024, 34, 1582–1593. [Google Scholar]

- Arif, M. Cross–species substitution matrix comparison of Tomato leaf curl New Delhi virus (ToLCNDV) with medicinal plant isolates. Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection 2024, 131, 1925–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Z.; Khurshid, M. Immunocapture PCR Detection of ToLCNDV from Plant Extract by using Heterologous Virus Coat Protein Antisera. Pakistan Journal of Zoology 2017, 49, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belén, R.; Pedro, G.; Dirk, J.; Ruiz, L. Insights into the Key Genes in Cucumis melo and Cucurbita moschata ToLCNDV Resistance. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Prasad, M. Interaction of ToLCNDV TrAP with SlATG8f marks it susceptible to degradation by autophagy. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2022, 79, 241–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez–Moro, C.; Sáez, C.; Sifres, A.; Lopez, C.; Dhillon, N.P.S.; Picó, B.; Pérez–de–Castro, A. Genetic Dissection of ToLCNDV Resistance in Resistant Sources of Cucumis melo. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 8880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, M.T.; Voinnet, O.; Baulcomb, D.C. Initiation and maintenance of virus–induced gene silencing. The Plant Cell 1998, 10, 937–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacomme, C.; Hrubikova, K.; Ingo, H. Enhancement of virus–induced gene silencing through viral–based production of inverted–repeats. The Plant journal for cell and molecular biology 2003, 34, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennypaul, H.S.; Mutti, J.S.; Rustgi, S.; Kumar, N.; Okubara, P.A.; Gill, K.S. Virusinduced gene silencing (VIGS) of genes expressed in root, leaf, and meiotic tissues of wheat. Funct Integr Genomics 2012, 12, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlavan, A.; Solouki, M.; Fakheri, B.; Nasab, B.F. Using Morphological and Phytochemical Traits and ITS (1, 4) and rbcl DNA Barcodes in the Assessment of Different Malva sylvestris L. Genotypes. Journal of Medicinal Plants and By-Products-Jmpb 2021, 10, 19–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, M.; Amir, A.; Ikram, A. In Silico Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Proteins of Different Field Variants. Vaccines 2023, 11, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naing, H.A.; Song, Y.H.; Lee, M.J.; Lim, K.B.; Kim, C.K. Development of an efficient virus–induced gene silencing method in petunia using the pepper phytoene desaturase (PDS) gene. Plant Cell. Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2019, 138, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avesani, L.; Marconi, G.; Morandini, F.; Albertini, E.; Bruschetta, M.; Bortesi, L.; Pezzotti, M.; Porceddu, A. Stability of potato virus X expression vectors is related to insert size: implications for replication models and risk assessment. Transgenic Research 2007, 16, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleba, Y.; Klimyuk, V.; Marillonnet, S. Viral vectors for the expression of proteins in plants. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2007, 18, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyret, H.; Lomonossoff, G.P. When plant virology met Agrobacterium: the rise of the deconstructed clones. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2015, 13, 1121–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruun–Rasmussen, M.; Madsen, C.T.; Jessing, S.; Albrechtsen, M. Stability of barley stripe mosaic virus–induced gene silencing in barley. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact 2007, 20, 1323–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakir, C. Mahmut Tör. Factors influencing barley stripe mosaic virus–mediated gene silencing in wheat. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol 2010, 74, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xu, H.; Amilijiang, W.; Wang, H. Developing and applying a virus–induced gene silencing system for functional genomics in walnut (Juglans regia L.) mediated by tobacco rattle virus. Gene 2025, e936149087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, K.; Lu, Z.; Yang, H.; Chen, S.; Li, C.; Cao, D.; Wang, H.; Hao, Q.; Chen, H.; Shan, Z. Efficient Virus–Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) Method for Discovery of Resistance Genes in Soybean. Plants 2025, 14, 1547–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.S.; Cheng, A.C.; Yang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Jia, R.Y.; Liu, M.F.; Zhu, D.K.; Chen, S.; Zhang, S.Q.; Zhao, X.X. Structures and Functions of the 3′ Untranslated Regions of Positive–Sense Single–Stranded RNA Viruses Infecting Humans and Animals. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2020, 10, 453. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, T.Y.; Yang, F.Y.; Yang, F.; Cao, W.J.; Zheng, H.X.; Zhu, Z.X. Structural diversity and biological role of the 5’ untranslated regions of picornavirus. RNA Biology 2023, 20, 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El–Mohtar C, Dawson W O. 2014. Exploring the limits of vector construction based on citrus tristeza virus. Virology, 448: 274–283.

- Qiao, W.; Falk, B. Efficient protein expression and virus–induced gene silencing in plants using a crinivirus–derived vector. Viruses 2018, 10, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Bradshaw, J.D.; Whitham, S.; Hill, J.H. The development of an efficient multipurpose bean pod mottle virus viral vector set for foreign gene expression and RNA silencing. Plant Physiol 2010, 153, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacak, A.; Strozycki, P.M.; Barciszewska–Pacak, M.; Alejska, M.; Lacomme, C.; Jarmolowski, A.; Szweykowska-Kulinska, Z.; Figlerowicz, M. The brome mosaic virus–based recombination vector triggers a limited gene silencing response depending on the orientation of the inserted sequence. Arch Virol 2010, 155, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killiny, N.; Nehela, Y.; Hijaz, F.; Ben–Mahmoud, S.K.; Hajeri, S.; Gowda, S. Citrus tristeza virus–based induced gene silencing of phytoene desaturase is more efficient when antisense orientation is used. Plant Biotechnology Reports 2019, 13, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, R.; Dasgupta, I. Phenotyping of VIGS–mediated gene silencing in rice using a vector derived from a DNA virus. Plant Cell Reports 2017, 36, 1159–1170. [Google Scholar]

- Bruun–Rasmussen, M.; Madsen, C.T.; Jessing, S.; Albrechtsen, M. Stability of barley stripe mosaic virus–induced gene silencing in barley. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact 2007, 20, 1323–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiriart, J.B.; Lehto, K.; Tyystjärvi, E.; Junttila, T.; Aro, E.M. Suppression of a key gene involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis by means of virus–inducing gene silencing. Plant Mol. Biol. 2002, 50, 213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z.; Xing, M.; Liu, X.; Fang, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhuang, M.; Lv, H. An efficient virus–induced gene silencing (VIGS) system for functional genomics in Brassicas using a cabbage leaf curl virus (CaLCuV)–based vector. Planta 2020, 252, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, Z.H.; Chen, Y.; Zhai, M.; Zhu, K.K.; Xuan, J.P.; Hu, L.J. Development and application of a virus–induced gene silencing system for functional genomics in pecan (Carya illinoinensis). Scientia Horticulturae 2023, 310, e111759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| VIGS Sytems (with pCambia-ToLCNDV-1.6B) |

Systemically silenced plants/total infiltrated plants | Systemic silencing frequency in average* |

|---|---|---|

| pToLCNDV-288CmPDS-NK | 14/16, 14/16, 15/16 | 89.58% ± 3.61% |

| pToLCNDV-165CmPDS-NK | 15/16, 15/16, 16/16 | 95.83% ± 3.61% |

| pToLCNDV-87CmPDS-NK | 13/16, 14/16, 13/16 | 83.33% ± 3.61% |

| pToLCNDV-48CmPDS-NK | 14/16, 13/16, 12/16, | 81.25% ± 6.25% |

| pToLCNDV-165CmPDS-NB | 16/16, 16/16, 16/16, | 100.00% ± 0% |

| pToLCNDV-165CmPDS-SS | 13/16, 12/16, 13/16 | 79.17% ± 3.61% |

| pToLCNDV-165CmPDS-RC-NK | 14/16, 15/16, 16/16 | 93.75% ± 6.25% |

| pToLCNDV-87CmPDS-RC-NK | 14/16, 12/16, 13/16, | 81.25% ± 6.25% |

| pToLCNDV-48CmPDS-RC-NK | 13/16, 13/16, 14/16 | 83.33% ± 3.61% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).