1. Introduction

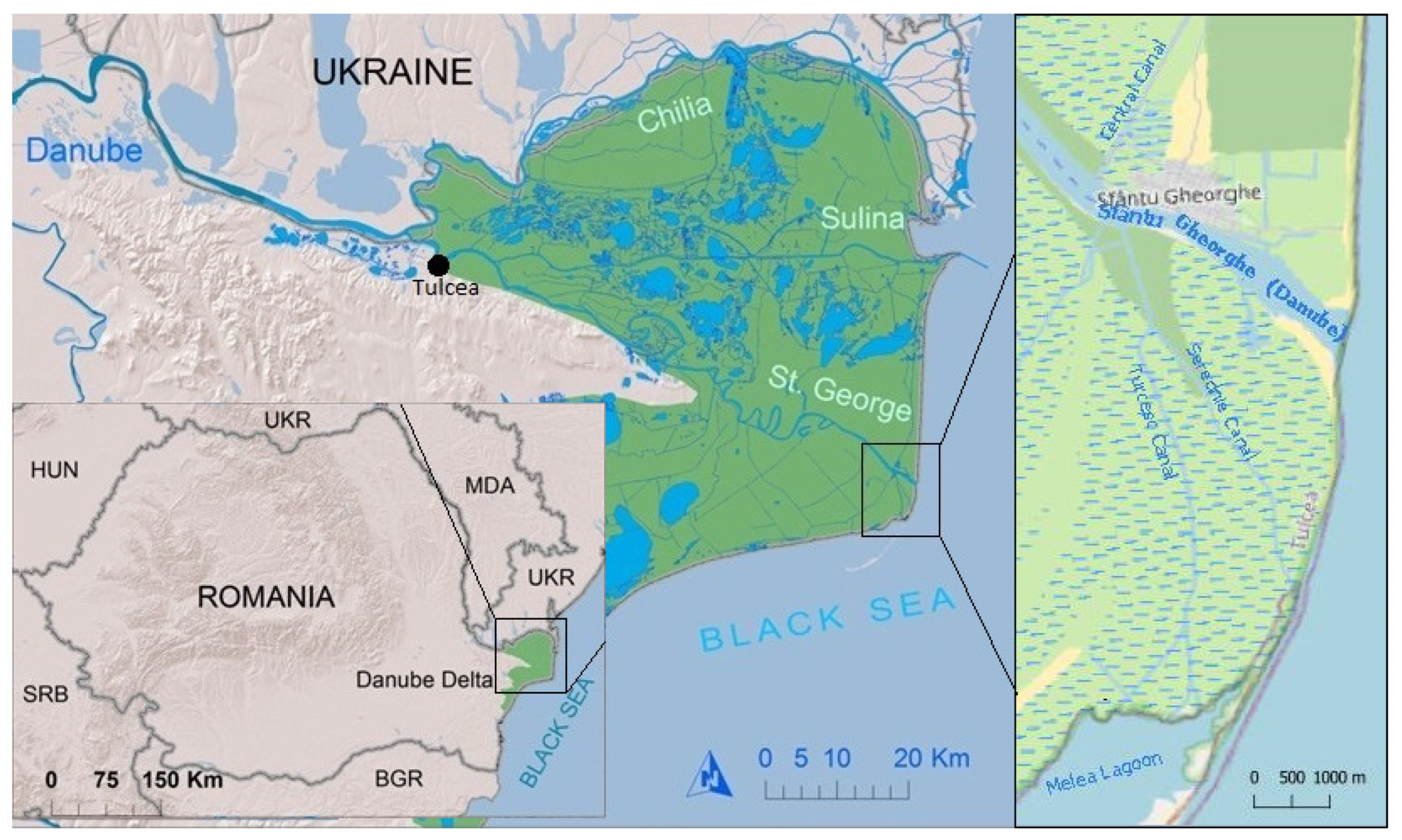

Microbiological risk assessment plays a crucial role in safeguarding public health by quantifying and qualitatively characterizing potential health hazards associated with exposure to microbial contaminants. In this context, the present study focuses on evaluating the microbiological risks related to water sources and fish-based food in the Danube Delta, near Sfântu Gheorghe locality (

Figure 1).

Vibrio species consist of short, curved, Gram-negative bacilli with high motility due to a polar flagellum ubiquitous to marine and estuarine ecosystems, various pathogenic species being frequently linked to

Vibrio infection outbreaks. These infections often result from the ingestion of contaminated food and water, including with human faeces or sewage, as well as the consumption of raw fish and seafood. Additionally, exposure of skin lesions, such as cuts, open wounds, and abrasions, to aquatic environments and fish poses a risk for Vibrio infections [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

Escherichia coli is a rod-shaped, Gram-negative bacterium inhabiting the lower intestinal tract of warm-blooded animals, including humans, often being discharged into the environment. Lately, due to changing environmental conditions,

E. coli can survive for long periods of time and naturalize within the indigenous microbial communities, raising concerns of water quality and public health [

6,

7,

8]. The Danube Delta holds significant tourist appeal, yet it simultaneously presents a landscape marked by disparities in infrastructure, access to medical services, living standards, and community development. Communities rely heavily on fishing and local resources. The health of the population is influenced, among various factors, by the natural environment and the uneven distribution of medical facilities, particularly disadvantaging administrative units within the Danube Delta. Health services in this region face challenges such as poor accessibility, lack of interest from the few physicians, and a local population that is both sparse and low-income, with a considerable portion lacking medical insurance. For emergency situations, a service comprising three motorboats, equipped with medical facilities, can navigate the Tulcea-Sfântu Gheorghe route within a few hours. During winter, when the Danube is frozen, emergency assistance may require the use of an icebreaker or a SMURD helicopter. Pharmaceutical services are also very scarce.

This makes any potential infections of high importance and calls for a thorough public information about these risks for a good prevention [

9,

10,

11]. The objective of our study was to isolate and identify the microbiome present in water and sediment samples collected from aquatic habitats within the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve, as well as from fish specimens inhabiting these environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Bacteriological Analysis

Water samples were collected at a depth of approximately 20-30 cm using 50 ml polyethylene containers (Isolab). Microbiological samples from fish and sediment were also collected in transport medium (Deltalab, Eurotubo). Fish specimens were dissected on-site using sterile disposable instruments, and samples were collected from the gills and hepato-pancreas using sterile swabs. For water assessment purposes, ten sampling points near the Sfântu Gheorghe locality were strategically selected across eight seasons. Additionally, over 100 samples of gills and hepatopancreas from various fish species including perch (Perca fluviatilis), wels catfish (Silurus glanis), sander (Sander lucioperca), pike (Esox lucius), hardtail (Alosa immaculate), gibel carp (Carassius gibelio), and common carp (Cyprinus carpio) were collected from the Danube River mouth near the Sfântu Gheorghe locality.

Standard microbiological methods were employed for the isolation and identification of bacterial strains. Homogenized samples were transferred into nutrient broth and alkaline peptone water. The tubes were incubated at various temperatures (30°C, 37°C) for 24-48 hours in aerobic conditions. Subsequently, the pre-enriched samples were transferred onto selective media, including MacConkey agar, thiosulphate–citrate–bile salts–sucrose agar (TCBS), and Brilliance UTI agar, and incubated for an additional 24-48 hours. Isolated colonies were then transferred to Tryptone soy agar (TSA) and nutrient agar, followed by a 24-hour incubation. The developed colonies were selected, subjected to Gram staining, and underwent an oxidase test (Microbact). Bacterial strain characterization was conducted using the Rapid One NF Plus (ThermoFischer Scientific, Remel), API 20E, and API 20NE systems (bioMerieux).

2.2. Data Analysis

2.2.1. Method for Microbiological Risk Assessment

Risk assessment represents the quantitative or qualitative characterization and estimation of the potential occurrence of adverse health effects associated with an individual’s or a population’s exposure to a hazard [

12,

13]. Therefore, the first step is the identification and characterization of the hazard. The studied pathogenic bacteria are contaminants but also naturally exist in water, and potential exposure pathways are diverse, ranging from common ones, such as water or food ingestion, to exposure through open wounds in water or while handling and processing infected fish. This initial step is followed by the assessment of the dose-response relationship, as some microbial pathogens have a lower infective dose than others. The evaluation then continues with exposure assessment, considering areas with different uses and visitation rates, ultimately leading to a comprehensive risk characterization. These are the steps of a static risk assessment model used for the microbiological risks, such as water and food sources, throughout their cycles. Dynamic risk assessment methods have also been developed, considering the nature and characteristics of microbial pathogens. These methods additionally evaluate indirect or secondary transmission routes in cases where person-to-person transmission may occur. However, pathogens transmitted through these routes usually do not exhibit this characteristic, or it is not as significant as in the case of water and food consumption and the cycle of contaminated food – fish.

For the microbiological risk assessment related to water, the 10 sampling points considered in the Sfântu Gheorghe locality area, with seasonal repeatability (8 seasons), the frequency of occurrence of pathogens in each sampled area could be calculated. Microbial species were evaluated based on certain important parameters that can influence the degree of microbiological hazard. Among these parameters, the following were chosen: survival duration and potential for multiplication in the aquatic environment [

3,

14,

15,

16,

17] and the predisposition of pathogen occurrence based on regional meteorological phenomena [

18,

19,

20]. Additionally, pathogens were characterized based on the degree of zoonotic risk, infectivity, and the potential to cause foodborne intoxications [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

In addition to the risks associated with the ingestion and/or contact with untreated water, there are also risks in the fish-based food preparation cycle, especially in the early stages – capture, handling, and primary preparation (contact, cleaning, evisceration, etc.).

Microbiological risk in the occurrence of foodborne intoxications and other types of non-digestive infections from fish to humans were calculated based on the literature mentioned above and the frequency of identification of known microorganisms with potential pathogenicity for humans (

V. cholerae, V. fluvialis, V. alginolyticus, V. metschnikovii, V. mimicus, V. vulnificus, V. parahaemolyticus and

E. coli) in the gills and hepatopancreas of the studied fish species [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Based on this information, a qualitative assessment was made regarding the zoonotic risk, leading to a preliminary classification into classes of microorganisms – pathogenic, opportunistic, causing nosocomial infections, and foodborne intoxications. As a result of this classification, a risk score ranging from 0 to 5 was estimated, representing situations from no zoonotic risk (0) to high zoonotic risk (5). For microbiological risks related to water, each parameter was evaluated by scoring on a scale of 1 to 10. The sum of the scores for all parameters was then applied to the calculated frequency at each water sampling point, generating a microbial risk factor. To move from a point state (sampling points) to an area, spatial interpolation was used. To complete the spatial characterization of microbial risk, distinctive areas of interest were delineated in the study area, such as the most frequented zones or locations with the most frequent observations of high pollutant concentrations. In the case of microbiological risks related to the occurrence of foodborne intoxications and other types of non-digestive infections regarding fish as vectors, transmission through contact with skin lesions or through the “dirty hands - mouth” mechanism due to fish handling (primary contact, cleaning, evisceration) was considered. The risk associated with consuming the respective organs (gills, hepatopancreas) was not considered, as these situations were not encountered in the community.

3. Results

3.1. Human Microbiological Risk of Infections Transmitted Through Water and Fish

Following the microbiological analysis of the samples collected from the gills and hepatopancreas, bacterial strains belonging to the families

Vibrionaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, Enterococcaceae and

Staphylococcaceae were isolated. As indicated in the literature, fish can harbour pathogenic bacteria with zoonotic potential or act as carriers for human pathogens like

E. coli, Salmonella spp., etc. Fish typically acquire bacteria from water, but through migration, they can transport and contaminate different areas. Concerning human aquatic microbiological risk, the highest values for

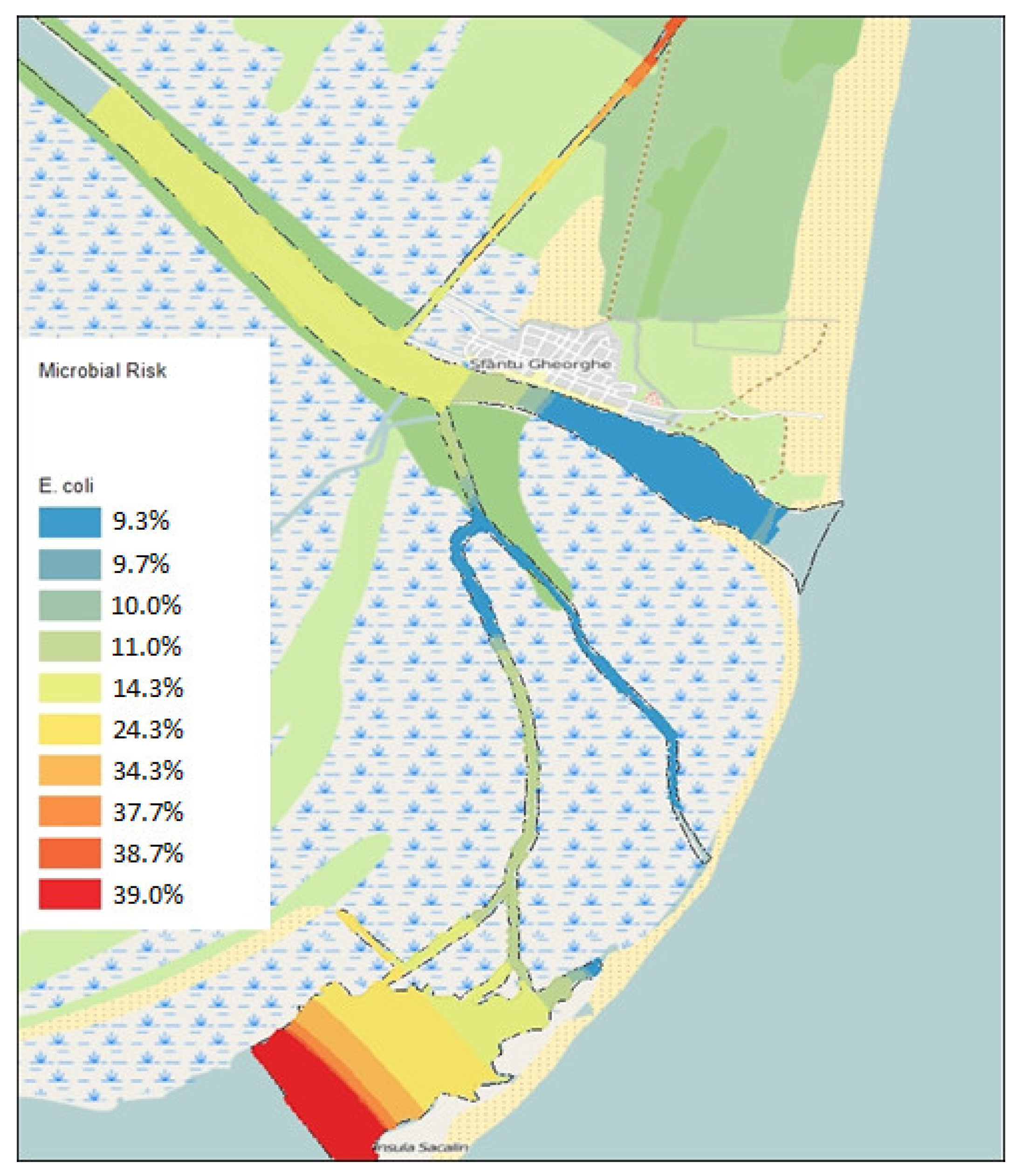

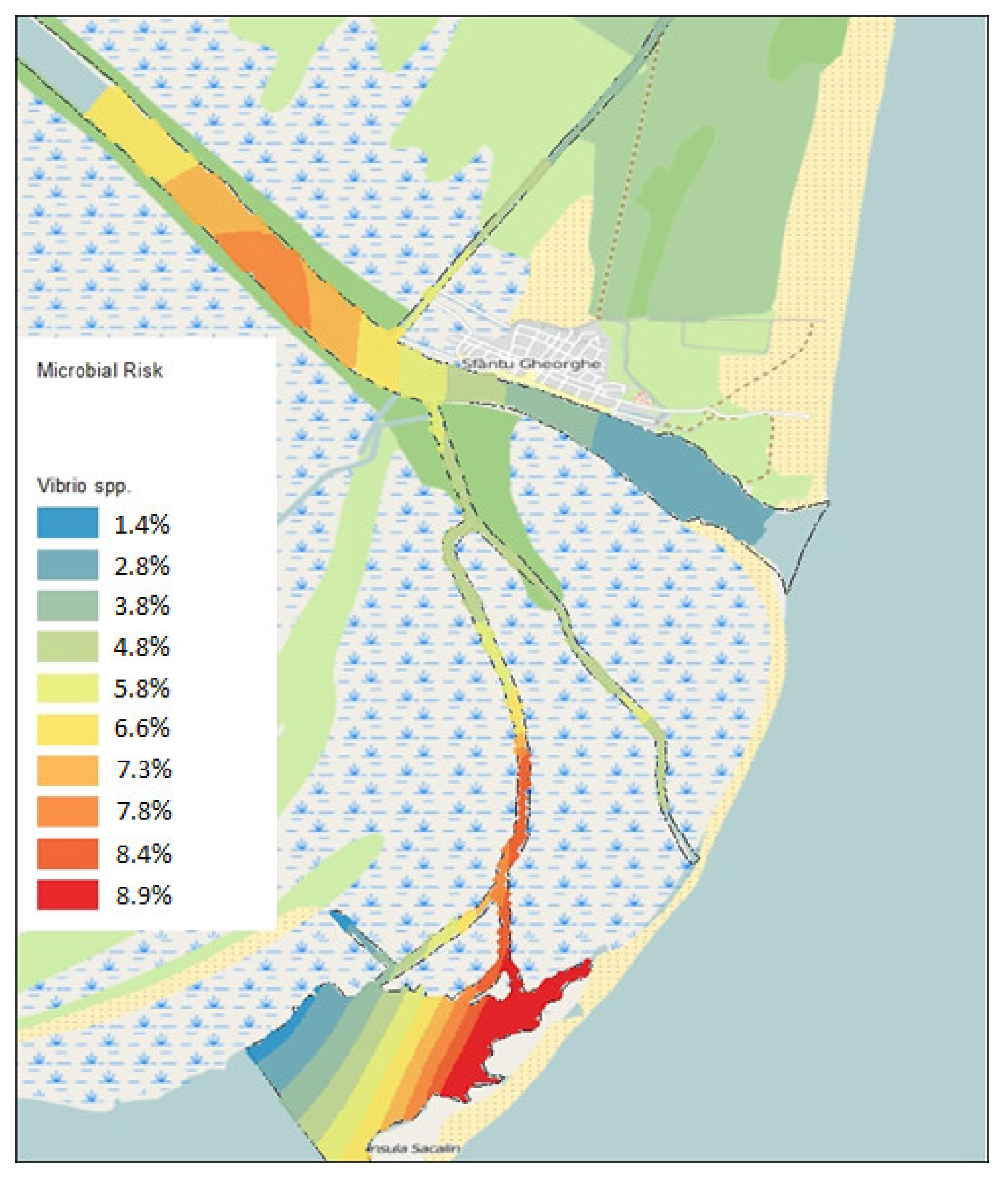

Vibrio spp. (

Figure 2) were observed in the Canal and Melea Lagoon area (2.7 or 8.9%) and in the Sfântu Gheorghe Arm area (2.5/8.5%), upstream of the locality. The lowest values were in the Central Canal area and at the mouth of the Sfântu Gheorghe Arm (0.8/2.7%). For microbiological risk related to

E. coli (

Figure 3), the highest values were also observed in the Melea Lagoon and the Central Canal (11.7 or 39%), and the lowest in the area at the mouth of the Sfântu Gheorghe Arm and the Turkish Canal (2.9/9.8%). Based on the frequency of identification of microorganisms in the studied fish species and the calculated total risk of infections, both non-digestive and foodborne intoxications were higher in gills than in the hepatopancreas for species such as pike (12/10.81 - non-digestive and 10.59/8.53 - foodborne intoxications), perch (11.89/10.42; 9.21/6.05), carp (10.25/9.32; 7.94/5.98), and zander (9.3/8.7; 6/5.5). For pontic shad (11.1/13.6; 8/11) and crucian carp (7.83/8.67; 6.43/6.5), the calculated total risk was higher in the hepatopancreas than in the gills. In the case of catfish, the calculated microbiological risk for non-digestive infections was slightly higher for the hepatopancreas (10.8/10.9), while that calculated for foodborne intoxications had higher values for gills (9.36/8.97). The calculated microbiological risk for gills had the highest values for pike (12 - non-digestive and 10.59 - foodborne intoxications) and the lowest for crucian carp (7.83 - non-digestive) and zander (6 - foodborne intoxications). Conversely, the calculated risk for the hepatopancreas had the highest values for pontic shad (13.6 and 11) and the lowest for carp (8.39 - non-digestive) and zander (5.5 - foodborne intoxications).

On average, it can be observed that the species with the highest potential microbiological risk for foodborne intoxication is pike (9.56), pontic shad (9.5), and catfish (9.17). Similar to the microbiological risk of foodborne intoxications, the microbiological risk for non-digestive infections is higher for species like pontic shad (12.35), pike (11.4), perch (11.16), and catfish (10.85). It should be noted that although the calculated microbiological risk of infection is highest for pontic shad, the duration of exposure is limited by the temporary human presence during the migration of these fish for reproduction. This microbiological risk of foodborne intoxications and other types of non-digestive infections from fish to humans considers transmission mechanisms through contact with skin lesions or the “dirty hands - mouth” mechanism resulting from the handling of fresh fish (contact, cleaning, evisceration). While rare in human pathology, infections developed through these routes can be severe, leading to death. According to literature data, dense bacterial populations can be concentrated from water and developed in fish organisms, especially in gills (up to 10

6 populations/g) and in the digestive system (approximately 10

8 heterotrophic populations/g and 10

5 anaerobic populations/g), as well as on the skin/scales (10

2–10

4 populations/cm²), eggs (10

3–10

6 populations/g), larvae, etc. [

34,

35]. In the first phase, direct contact with caught fish, by removing them from nets, transfers bacteria from their skin and mouth and gills. Microscopic lesions caused by scales, fins, teeth, etc., can occur in this process. Then, evisceration, a process recommended to be performed as quickly as possible after capturing the fish to remove the source of powerful proteases and enzymes from the digestive tract, ensuring quality and preventing their spoilage [

36,

37] involves secondary contact with the intestinal tract and organs. The use of sharp instruments on-site (often the process is carried out on a boat) increases the risk of cut and puncture wounds and indirect contamination. There are reported cases, especially of skin infections developed through these routes, primarily due to

Vibrio species (

V. vulnificus, V. alginolyticus, V. parahaemolyticus, and other unidentified

Vibrio spp.) [

38,

39,

40,

41].

4. Conclusions

The brackish waters of the lagoon formed at the mouth of the right secondary branch of Sf. Gheorghe - the Melea area is a combined risk zone (with the highest risk) for human health but has no consequences since it lacks permanent human settlements, and anthropogenic activities, like tourism, bird-watching or fishing, are reduced or prohibited, being a strictly protected area. The One Health concept is interrupted, with the possibility being extremely limited for transmission through direct contact/ingestion to humans. The calculated major aquatic microbiological risk is distributed in the right secondary branch and Melea Lagoon area and the Sfântu Gheorghe Arm, upstream of the locality. The microbiological risk in the transmission of diseases from fish to humans due to their handling is higher for non-digestive infections (contamination in the case of superficial wounds, up to septicaemia and death) compared to foodborne intoxications. The microbiological risk of foodborne intoxications, although lower, can be reduced because gastrointestinal mass is generally not consumed, and the consumption of raw fish is not specific to the area.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G., A.G. and M.S.; formal analysis E.P.; funding acquisition, M.S.; investigation, G.G.; methodology,G.G., E.P. and M.S.; supervision, A.G and E.P.; validation, G.G., M.S. and P.N.; writing—original draft, G.G.; writing—review and editing, G.G. and E.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financed by the....

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Noorian, P.; Hoque, M.M.; Espinoza-Vergara, G.; Mcdougald, D. Environmental Reservoirs of Pathogenic Vibrio spp. and Their Role in Disease: The List Keeps Expanding. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2023, 1404, 99–126. [Google Scholar]

- Normanno, G.; Parisi, A.; Addante, N.; Quaglia, N.C.; Dambrosio, A.; Montagna, C.; Chiocco, D. Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus and microorganisms of fecal origin in mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) sold in the Puglia region (Italy). International Journal Of Food Microbiology. 2006, 106, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waidner, L. A.; Potdukhe, T.V. Tools to Enumerate and Predict Distribution Patterns of Environmental Vibrio vulnificus and Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Microorganisms. 2023, 11, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canellas, A.; Lopes, I.; Mello, M.; Paranhos, R.; De Oliveira, B.; Laport, M. Vibrio Species in an Urban Tropical Estuary: Antimicrobial Susceptibility, Interaction with Environmental Parameters, and Possible Public Health Outcomes. Microorganisms. 2021, 9, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker-Austin, C.; Oliver, J.D.; Alam, M.; Afsar, A.; Waldor, M.K.; Qadri, F.; Martinez-Urtaza, J. Vibrio spp. infections. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edberg, S.C.; Rice, E.W.; Karlin, R.J.; Allen, M.J. Escherichia coli: the best biological drinking water indicator for public health protection. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2000, 88, 106S–116S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Hur, H.-G.; Sadowsky, M.J.; Byappanahalli, M.N.; Yan, T.; Ishii, S. Environmental Escherichia coli: ecology and public health implications—a review. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2017, 123, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standridge, J. E. coli as a public health indicator of drinking water quality. American Water Works Association. 2008, 100, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, M.; Nedelcu, I.; Carboni, D.; Bratu, A.; Omer, S.; Grecu, A. Medical Infrastructure Evolution and Spatial Dimen-sion of the Population Health State from the Danube Delta. In The Danube River Delta. Earth and Environmental Sciences Library; Negm, A.M., Diaconu, D.C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Damian, N.; Mocanu, I.; Mitrică, B. Education and health care provision in the Romanian Danube Valley: Territorial disparities. Area. 2019, 51, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damian, N. Socio-Economic development in the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve. Rev. Roum. Géogr./Rom. Journ. Geogr. 2016, 60, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Soller, J. A.; Olivieri, A.W.; Eisenberg, J.N.S.; Sakaji, R.; Danielson, R. Evaluation of Microbial Risk Assessment Techniques and Applications. WERF – Water Environment Research Foundation; IWA Publishing: Colchester, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua, A.; De Santis, A.; Sollazzo, G.; Speranza, B.; Racioppo, A.; Sinigaglia, M.; Corbo, M. R. Microbiological Risk Assessment in Foods: Background and Tools, with a Focus on Risk Ranger. Foods (Basel, Switzerland). 2023, 12, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etinosa, O. I.; Okoh, A.I. Emerging Vibrio species: an unending threat to public health in developing countries. Research in Microbiology. 2008, 159, 495–506. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Cholera (CDC). Vibrio species causing vibriosis. 2016. Available online: www.cdc.gov/vibrio/vibriov.html (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Cholera Fact Sheet. 2016. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs107/en (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Gangwar, M.; Usmani, M.; Jamal, Y.; Brumfield, K.D.; Huq, A.; Unnikrishnan, A.; Colwell, R. R.; Jutla, A. S. Environmen-tal Factors Associated with Incidence and Distribution of V. parahaemolyticus and V. vulnificus in Chesapeake Bay, Maryland, USA: A three-year case study. bioRxiv: the preprint server for biology 2023, 09.25.559351. [Google Scholar]

- Administrația Națională de Meteorologice (ANM). Raport meteorologic, Centrul Meteorologic Dobrogea. 2016. Available online: https://www.meteoromania.ro/wp-content/uploads/raport/Raport-2016.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Eiler, A.; Johansson, M.; Bertilsson, S. Environmental influences on Vibrio populations in northern temperate and boreal coastal waters (Baltic and Skagerrak Seas). Applied and environmental microbiology. 2006, 72, 6004–6011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A.J.; Kabengele, K.; Almagro-Moreno, S.; Ogbunugafor, C.B. Meteorological associations of Vibrio vulnificus clinical infections in tropical settings: Correlations with air pressure, wind speed, and temperature. PLoS Neglected tropical diseases. 2023, 17, e0011461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlady, W.G.; Mullen, R.C.; Hopkins R., S. Vibrio vulnificus from raw oysters. Leading cause of reported deaths from foodborne illness in Florida. J. Fla. Med. Assoc. 1999, 80, 536–538. [Google Scholar]

- Swartz, M.N. Human Diseases Caused by Foodborne Pathogens of Animal Origin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, S111–S122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampfer, J.; Gohring, T.N; . Attin, T.; Zehnder, M. Leakage of food-borne Enterococcus faecalis through temporary fillings in a simulated oral environment. International Endodontic Journal. 2007, 40, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwamoto, M.; Ayers, T.; Mahon, B.E.; Swerdlow, D.L. Epidemiology of seafood-associated infections in the United States. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 339–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, J.N.; Isokpehi, R.D.; Cooper, G.A.; Bass, M.P.; Brown, S.D.; John, A.L.; Gulig, P.A.; Cohly, H.P. Visual analytics of Surveillance data on foodborne Vibriosis in United States, 1973-2010. Environ. Health Insights. 2011, 5, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamurtthy, T.; Chowdhury, G.; Pazhani, G.P.; Shinoda, S. Vibrio fluvialis: an emerging human pathogen. Front Microbiol. 2014, 5, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Wen, J.; Ma, Y.; Ma, X.; Chen, Y. Epidemiology of foodborne disease outbreaks caused by Vibrio parahaemolyticus, China, 2003-2008. Food Control. 2014, 46, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neetoo, H.; Reega, K.; Manoga, Z.S.; Nazurally, N.; Bhoyroo, V.; Allam, M.; Jaufeerally-Fakim, Y.; Ghoorah, A.W.; Jaumdally, W.; Hossen, A.M.; Mayghun, F.; Ismail, A.; Hosenally, M. Prevalence, Genomic Characterization, and Risk Assessment of Human Pathogenic Vibrio Species in Seafood. Journal of food protection. 2022, 85, 1553–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauge, T.; Mougin, J.; Ells, T.; Midelet, G. Sources and contamination routes of seafood with human pathogenic Vibrio spp.: A Farm-to-Fork approach. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2024, 23, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gati, G.; Niculae, M.; Páll, E.; Șandru, C.D.; Brudașcă, F.; Vasiu, A.; Popescu, S.; Spînu, M. Seasonal variation of antibiotic resistance of the fecal flora isolated from fish in the Danube Delta. Lucrari Stiintifice - Universitatea de Stiinte Agricole a Banatului Timisoara, Medicina Veterinara 2017, 50, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Gati, G.; Niculae, M.; Páll, E.; Șandru, C.D.; Brudașcă, F.; Vasiu, A.; Popescu, S.; Spînu, M. Changes in the microbiome of fish from the Danube Delta by habitat and feeding behaviors. Lucrari Stiintifice - Universitatea de Stiinte Agricole a Banatului Timisoara, Medicina Veterinara 2017, 50, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Páll, E.; Niculae, M.; Brudașcă, G.F.; Ravilov, R.K.; Șandru, C.D.; Cerbu, C.; Olah, D.; Zăblău, S.; Potârniche, A.V.; Spinu, M.; Duca, G.; Rusu, M.; Rzewuska, M.; Vasiu, A. Assessment and Antibiotic Resistance Profiling in Vibrio Species Isolated from Wild Birds Captured in Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve, Romania. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021, 22, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Páll, E.; Niculae, M.; Kiss, T.; Şandru, C.D.; Spînu, M. Human impact on the microbiological water quality of the rivers. J.Med. Microbiol. 2013, 62, 1635–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, B.; Dawn, A.A. Bacterial Fish Pathogens: Disease of Farmed and Wild Fish, Fifth Edition; Springer Science and Business Media: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ronald, R.J. Fish Pathology, Fourth Edition; Wiley-Blackwell, John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaly, A.E.; Dave, D.; Budge, S.; Brooks, M.S. Fish spoilage mechanisms and preservation techniques: Review. American Journal of Applied Sciences. 2010, 7, 859–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G.M. Fish processing technology, Second Edition; Springer Science & Business Media: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Håstein, T.; Hjeltnes, B.; Lillehaug, A.; Skåre, J.U; Berntssen, M.; Lundebye, A.K. Food safety hazards that occur during the production stage: challenges for fish farming and fishing industry. Rev. Sci. Tech. Int. Epiz. 2006, 25, 607–625. [Google Scholar]

- Cimolai, N. Fish processing and human infection. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal/Journal de l’Association medicale canadienne 2017, 189, E1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mccarthy, M.; Brennan, M.; Kelly, A.L.; Ritson, C.; De Boer, M.; Thompson, N. Who is at risk and what do they know? Segmenting a population on their food safety knowledge. Food Quality and Preference. 2007, 18, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedane, T.D.; Agga, G.E.; Gutema, F.D. Hygienic assessment of fish handling practices along production and supply chain and its public health implications in Central Oromia, Ethiopia. Scientific reports. 2022, 12, 13910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).