Submitted:

23 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

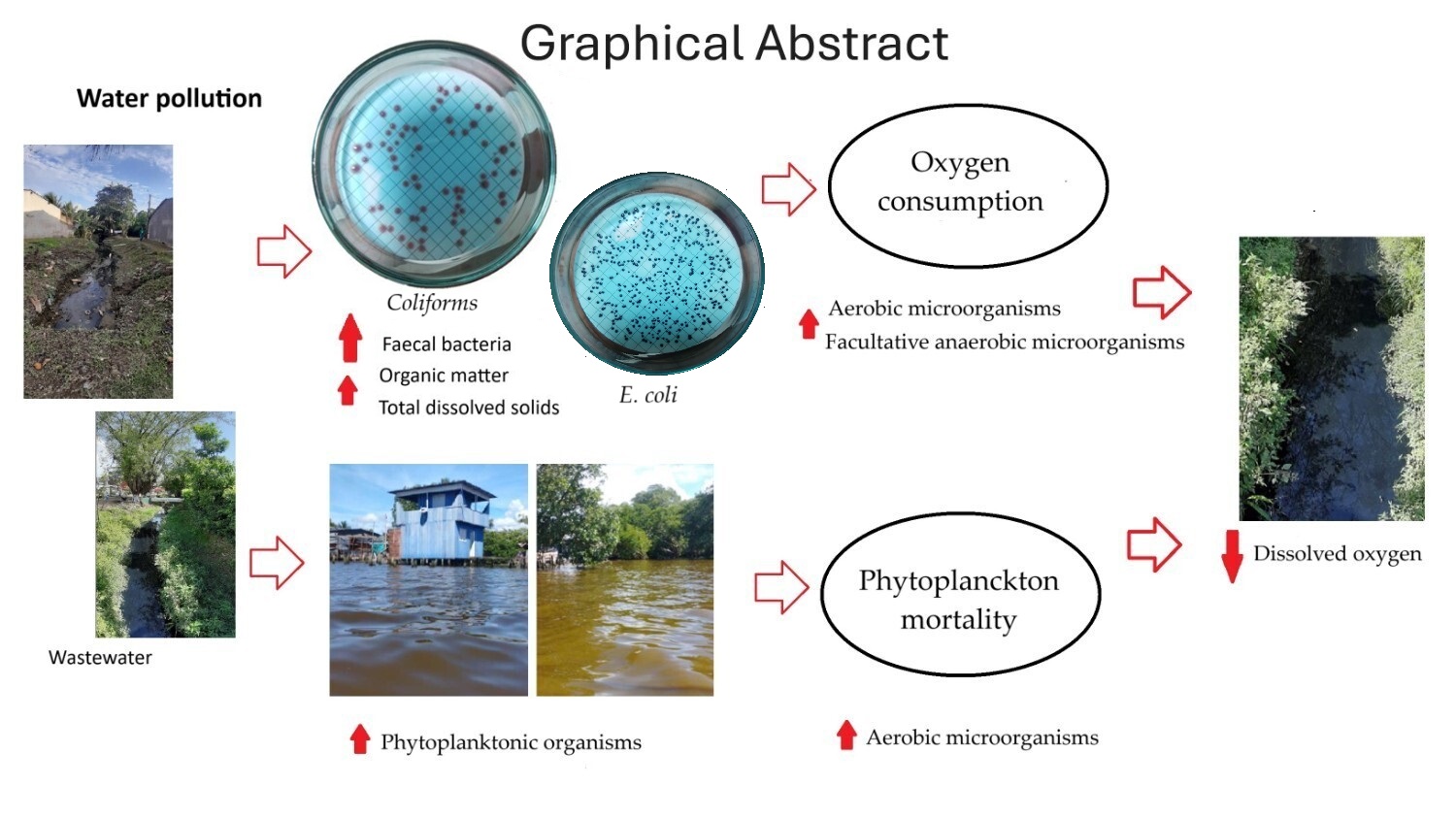

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

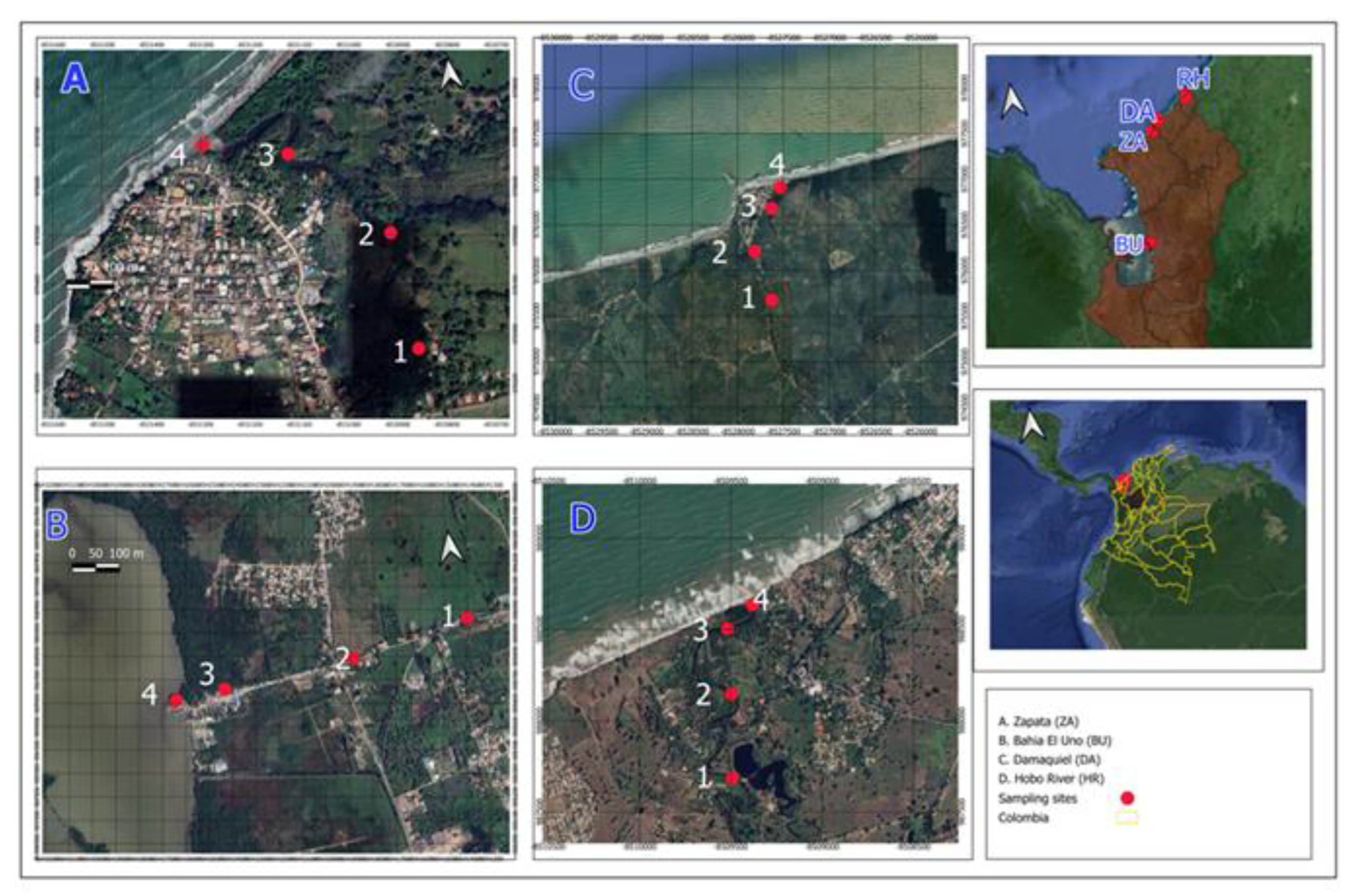

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TC | Total coliforms |

| TTC | Thermotolerant coliforms |

| °C | Centigrade degrees |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| GISMAC | Marine and coastal systems research group |

| IDEAM | Colombian Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies (Instituto de hidrología, meteorología y estudios ambientales de Colombia). |

| mL | Milliliter |

| mm/month | Millimeters per month |

| mg/L | Milligrams per liter |

| MPN | Most Probable Number |

| MPN/100mL | Most Probable Number per 100 milliliters |

| DO | Dissolved oxygen |

| TDS | Total dissolved solids |

References

- Peters. N. E., Meybeck. M., & Chapman. D. V. Effects of Human Activities on Water Quality. In M. G. Anderson & J. J. McDonnell (Eds.). Encyclopedia of Hydrological Sciences (1st ed.). Wiley. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Hale, R.L., Grimm, N.B., Vörösmarty, C.J., & Fekete, B. (2015). Nitrogen and phosphorus fluxes from wátersheds of the northern U.S. from 1930 to 2000: Role of anthropogenic nutrient inputs, infrastructure, and runoff. Global Biochemical Cycles. 2015. 29 (3): 341-356. [CrossRef]

- Derfoufi, H., Legssyer, M., Belbachir, C., & C., & Legssyer, B. Effect of physicochemical and microbiological parameters on the water quality of wadi Zegzel. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2019, 13, 730-738. [CrossRef]

- Camara, M., Jamil, N. R., & Abdullah, A.F.B. Impact of land uses on water quality in Malaysia: a review. Ecol Process, 2019, 8, 10. [CrossRef]

- Chester, R. (1990). The transport of material to the oceans: the river pathway. Marine Geochemistry. Springer, Dordrecht, 1990. [CrossRef]

- Umaña. G. Characterization of some Golfo Dulce drainage basin rivers (Costa Rica). Rev. Biol. Trop, 1998, 46, 125-135.

- Calvo. G., & Mora. J. Preliminary evaluation and classification of water quality in the Tárcoles and Reventazón river basins. Part IV: Statistical analysis of variables related to water quality. Tecnología en Marcha, 2009, 22, 57-64.

- du Plessis, A. Persistent degradation: Global water quality challenges and required actions. One Earth, 2022, 5 (2): 129-131. [CrossRef]

- Ciobotaru, A. Influence of human activities on water quality of rivers and groundwaters from Brǎila Country. Annals of the University of Oradea, Geography Series, 2015, 5-13.

- Gianoli, A., Hung, A., & Shiva, C. Relationship between total and thermotolerant coliforms with water physicochemical factors in six beaches of Sechura-Piura bay 2016-2017. Salud y Tecnología Veterinaria, 2018, 2: 62-71. [CrossRef]

- Covich, A.P., Austen, M.C., Bärlocher, F., Chauvet, E., Cardinale, B.J., Biles, C.L., Inchausti, P., Dangles, O., Solan, M., Gessner, M.O., Statzner, B., & Moss, B. The role of biodiversity in the functioning of freshwater and marine benthic ecosystems. BioScience, 2004, 54(8), 767-775. [CrossRef]

- Faghihinia, M., Xu, Y., Liu, D., & Wu, N. Freshwater biodiversity at different habitats: Research hotspots with persistent and emerging themes. Ecological Indicators, 2021, 129, 107926. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A., Chakrabarty. M., Rakshit, N., Bhowmick, A. R., & Ray, S. Environmental factors as indicators of dissolved oxygen concentration and zooplankton abundance: Deep learning versus traditional regression approach. Ecological Indicators, 2019, 100. 99-117. [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, D.A., Chendake, A.D., Ghosal, D., Mathuriya, A.S., Kumar, S.S., & S. Pandit. Chapter 6—Advanced microbial fuel cell for biosensor applications to detect quality parameters of pollutants. Bioremedation, Nutrient, and Other Valuable Produc Recovery, Elsevier, 2021, 125-139. [CrossRef]

- Braga, F.H.R., Dutra, M.L.S., Lima, N.S., Silva, G.M., Miranda, R.C.M., Firmo, W.C.A., Moura, A.R.L., Monteiro, A.S., Silva, L.C.N., Silva, D.F., & Silva, M.R.C. Study of the Influence of Physicochemical Parameters on the Water Quality Index (WQI) in the Maranhão Amazon. Brazil. Water, 2022, 14(10). 1546. [CrossRef]

- Vazquez Zapata. G., Herrera. L., Cantera. J., Galvis. A., Cardona. D., & Hurtado. I. METHODOLOGY TO DETERMINE EUTROPHICATION LEVELS IN AQUATIC ECOSYSTEMS. Journal of the Colombian Association of Biological Sciences, 2012, 24. 112-128. https://www.revistaaccb.org/r/index.php/accb/article/view/81/81.

- Aristizabal-Tique, V.H., Gomez-Gallego, D.D., Ramos-Hernandez, I.T., Arcos-Arango, Y., Polanco-Echeverry, D.N., & Velez-Hoyos, F.J. Assessing the Physicochemical and Microbiological Condition of Surface Waters in Urabá-Colombia: Impact of Human Activities and Agro-Industry. Water Air Soil Pollut, 2024, 235:260. [CrossRef]

- Ricaurte-Villota. C., & Bastidas. M. Oceanographic regionalisation: A dynamic vision of the Caribbean. Marine and Coastal Research Institute José Benito Vives De Andréis (INVEMAR). INVEMAR Special Publications Series#14. Santa Marta, Colombia, 2017, 180. https://www.invemar.org.co/en/publicaciones.

- Toro-Valencia, V. G., Mosquera, W., Barrientos, N., & Bedoya, Y. (2019). Circulación oceánica del golfo de Urabá usando campos de viento de alta resolución temporal. Boletín científico CIOH, 38(2), 41-56. [CrossRef]

- Roldan. P., Gómez. E., & Toro. F. Mean circulation pattern in Colombia Bay in the two extreme climatic epochs. XXIII Latin American Hydraulics Congress. Postgraduate thesis. School of Geosciences and Environment. National University of Colombia. September 2008, 12. https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/bitstream/handle/unal/8096/Roldan.Toro.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Campillo, A., Taupin, J. D., Betancur, T., Patris, N., Vergnaud,V., Paredes, V., & Villegas, P. (2021). A multi-tracer approach for understanding the functioning of heterogeneous phreatic coastal aquifers in humid tropical zones. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 2021, 66(4), 600-621. [CrossRef]

- American Public Health Association (APHA) (2005) Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater Analysis. American Water Works Association/Water Environment Federation. Washington DC. 289.

- Masindi, T. K., Gyedu-Ababio, T., & Mpenyana-Monyatsi, L. Pollution of Sand River by Wastewater Treatment Works in the Bushbuckridge Local Municipality, South Africa. Pollutants. 2022, 2(4):510-530. [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Tobón, S., Agudelo-Cadavid, R.M., & Gutiérrez-Builes, L.A. Pathogens and microbiological indicators of water quality for human consumption. Revista Facultad Nacional de Salud Pública, 2017, 35(2). 236-247. [CrossRef]

- Griffin, N.J.; Palmer, C.G.; Scherman, P.A. Critical Analysis of Environmental Water Quality in South Africa: Historic and Current Trends Report to the Water Research Commission; Water Research Commission: Pretoria, South Africa, 2014.

- Bienfang, P. K., Defelice, S. V., Laws, E. A., Brand, L. E., Bidigare, R. R., Christensen, S., Trapido-Rosenthal, H., Hemscheidt, T. K., McGillicuddy, D. J., Anderson, D. M., Solo-Gabriele, H. M., Boehm, A. B., & Backer, L.C. Prominent human health impacts from several marine microbes: history, ecology, and public health implications. International Journal of Microbiology. 2011, 20111-115. htpps://doi: 10.1155/2011/15281.

- Caissie, D. The thermal regime of rivers: A review. Freshwater Biology, 2006, 51, 1389-1406.

- Evans, E. C., Mcgregor, G. R., & Petts, G. E. (1998). River energy budgets with special reference to river bed processes. Hydrological Processes, 1998. 12, 575-595.

- Johnson, M. F., Albertson, L. K., Algar, A. C., Dugdale, S. J., Edwards, P., England, J., Gibbins, C., Kazama, S., Komori, D., MacColl, A. D. C., Scholl, E. A., Wilby, R. L., de Oliveira Roque, F., & Wood, P. J. Rising water temperature in rivers: Ecological impacts and future resilience. WIREs Water, 2024, 11(4), e1724. [CrossRef]

- Webb, B.W., Hannah, D.M., Moore, R.D., Brown, L.E., & Nobilis, F. Recent advances in stream and river temperature research. Hydrological Processes, 2008, 22(7), 902-918. [CrossRef]

- Webb, B. W.; Clack, P. D.; Walling, D. E. Water-air temperature relationships in a Devon River system and the role of flow. Hydrological Process. 2003, 17, 3069-3084.

- Mohseni, O.; Stefan, H.G. Stream temperature/air temperature relationship: A physical interpretation. Journal or Hydrology. 1999, 218, 128-141.

- Larrea-Murrell, J. A., Rojas-Badía, M. M., Romeu-Álvarez, B., Rojas-Hernández, N. M., & Heydrich-Pérez, M. Bacterias indicadoras de contaminación fecal en la evaluación de la calidad de las aguas: revisión de la literatura. Revista CENIC. Ciencias Biológicas, 2013, 44(3), 24-34.

- World Metrological Organization—WMO. Update predicts 60% chance of La Niña. Press Release. 11 september 2024. https://wmo.int/news/media-centre/wmo-update-predicts-60-chance-of-la-nina.

- Ruiz, J.F., & Melo, J.Y. Informe de Predicción Climática a corto, mediano y largo plazo en Colombia. Grupo de Modelamiento de Tiempo y Clima, Subdirección de Meteorología—IDEAM. Mayo de 2024. 12 pp.

- Ortiz Trujillo, J., Ramos De La Hoz, I., & Garavito Mahecha, J. D. (2023). Boletín Meteomarino Mensual del Caribe Colombiano No.131 / Noviembre de 2023. Cartagena de Indias D.T. y C., Colombia: Dirección General Marítima. https://cecoldodigital.dimar.mil.co//3369/3/dimarcioh_2339-4099_2023_bol_meteomarino_caribe_131.pdf.

- Ortiz Trujillo, Jonnatan and Llorente Valderrama, Alder De Jesús. (2024). Boletín Meteomarino Mensual del Caribe Colombiano No.133 / Enero de 2024. Cartagena de Indias D.T. y C., Colombia: Dirección General Marítima. https://cecoldodigital.dimar.mil.co//3425/1/dimarcioh_2339-4099_2023_bol_meteomarino_caribe_133.pdf.

- Llorente Valderrama, Alder de Jesús and Ramos De La Hoz, Isabel and Garavito Mahecha, José David. (2024). Boletín Meteomarino Mensual del Caribe Colombiano No.136 / Abril de 2024. Cartagena de Indias D.T. y C., Colombia: Dirección General Marítima. https://cecoldodigital.dimar.mil.co//3527/1/dimarcioh_2339-4099_2024_bol_meteomarino_caribe_136.pdf.

- Ortiz Trujillo, J. A., Ramos De La Hoz, I., & Garavito Mahecha, J. D. (2024). Boletín Meteomarino Mensual del Caribe Colombiano No.140 / Agosto de 2024. Cartagena de Indias D.T. y C., Colombia: Dirección General Marítima. https://cecoldodigital.dimar.mil.co//3557/1/dimarcioh_2339-4099_2024_bol_meteomarino_caribe_140.pdf.

- Centro de Investigaciones Oceanográficas e Hidrográficas del Caribe -CIOH. Derrotero de las costas y áreas insulares del Caribe colombiano. 2020. Tomo 1. Cartagena—Colombia.

- Poole. G.C., & Berman. C.H. An Ecological Perspective on In-Stream Temperature: Natural Heat Dynamics and Mechanisms of Human-CausedThermal Degradation. Environmental Management, 2001, 27(6). 787-802. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Castillo, A.C., & Rodríguez, A. Physicochemical index of water quality for the management of tropical flooded lagoons. Revista de Biología Tropical, 2008, 56 (4): 1905-1918.

- Shrestha, A. K., & Basnet, N. B. The correlation and regression analysis of physicochemical parameters of river water for the evaluation of percentage contribution to electrical conductivity. Journal of Chemistry. 2018:9, 8369613.

- Fusi, M., Daffonchio, D., Booth, J., & Giomi, F. Dissolved Oxygen in Heterogeneous Environments Dictates the Metabolic Rate and Thermal Sensitivity of Tropical Aquatic Crab. Frontiers in Marine Science. 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz. H., Orozco. S., Vera. A., Suárez. J., García. E., Mercedes. N., & Jiménez, J. Relationship between dissolved oxygen, rainfall and temperature: Zahuapan river. Tlaxcala. Mexico. Tecnología y ciencias del agua, 2015, 6(5). 59-74.

- Roslev. P., Bjergbaek. L. A., & Hesselsoe, M. Effect of oxygen on survival of faecal pollution indicators in drinking water. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2004, 96(5). 938-45. [CrossRef]

- McFeters, G. A. (Ed.). Drinking Water Microbiology, Springer, New York, NY. 1990, 3-31.

- Benjumea Hoyos, C. A., & Álvarez Montes, G. Oxygen demand by sediments in different stretches of the Negro Rionegro River. Antioquia. Colombia. Producción + Limpia, 2017, 12(2). 131-146.

- Martínez. S. A., & Pardo, G. A. S. S. Evaluation of the impact of domestic wastewater discharges. Through the application of the contamination index (ICOMO) in Caño Grande. Located in Villavicencio-Meta. Undergraduate. Faculty of Environmental Engineering. Santo Tomas. 2018. Colombia. http://hdl.handle.net/11634/14218.

- 49 Olds, H.T.; Corsi, S.R.; Dila, D.K.; Halmo, K.M.; Bootsma, M.J.; McLellan, S.L. High levels of sewage contamination released from urban areas after storm events: A quantitative survey with sewage specific bacterial indicators. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002614.

- Onifade, O.; Lawal, Z.K.; Shamsuddin, N.; Abas, P.E.; Lai, D.T.C.; Gӧdeke, S.H. Impact of Seasonal Variation and Population Growth on Coliform Bacteria Concentrations in the Brunei River: A Temporal Analysis with Future Projection. Water 2025, 17, 1069. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Health. Public health surveillance protocol. Morbidity due to acute diarrhoeal disease. National Institute of Health. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kadlec RH, Wallace SD. 2009. Treatment Wetlands. In: Ahumada-Santos, Y. P., Báez-Flores, M. E., Díaz-Camacho, S. P., Uribe-Beltrán, M. J., López-Angulo, G., Vega-Aviña, R., Chávez-Duran, F. A., Montes-Avila, J., Carranza-Díaz, O., Möder, M., Kuschk, P., & Delgado-Vargas, F. Distribución espaciotemporal de la contaminación bacteriana del agua residual agrícola y doméstica descargada a un canal de drenaje (Sinaloa, México). Ciencias marinas, 2014, 40(4), 277-289. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni. S. A Review on Research and Studies on Dissolved Oxygen and Its Affecting Parameters. International Journal of Research and Review, 2016, 3. 18-22. https://www.ijrrjournal.com/IJRR_Vol.3_Issue.8_Aug2016/IJRR004.pdf.

- Kitsiou, D., & Karydis, M. Coastal marine eutrophication assessment: A review on data analysis. Environment International, 2011, 37 (4). 778–801. [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y., Yu, J., Lei, G., Xue, B., Zhang, F., & Yao, S. Indirect influence of eutrophication on air—water exchange fluxes, sinking fluxes, and occurrence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Water Research., 2017, 122, 512-525. [CrossRef]

- Testa, J. M., Carstensen, J., Laurent, A., & Li, M. (2023) Hypoxia and Climate Change in Estuaries. In: Kennish, M.J., Eutrophication of Estuarine and Coastal Marine Environments: An Emerging Climatic-Driven Paradigm Shift. Open Journal of Ecology, 2025, 15(4), 289-324. [CrossRef]

- Rabalais, N. N., Cai, W. J., Carstensen, J., Conley, D. J., Fry, B., Hu, X., Quiñones-Rivera, Z., Rosenberg, R., Slomp, C. P., Turner, R. E., Voss, M., Wissel, B., & Zhang, J. Eutrophication-driven deoxygenation in the coastal ocean. Oceanography., 2014, 27(1):172–183. [CrossRef]

- Arcos Pulido, M. P., Ávila de Navia, S. L., Estupiñán Torres, S. M., & Gómez Prieto, A. C. Indicadores microbiológicos de contaminación de las fuentes de agua. Nova- Publicación Científica, 2005; 3 (4): 69–79. http://www.unicolmayor.edu.co/invest_nova/NOVA/ARTREVIS2_4.pdf.

- Rivera Gutiérrez, J. V. Determinación de las tasas de oxidación, nitrifícación y sedimentación en el proceso de autopurificación de un río de montaña. Ingeniare. Revista chilena de ingeniería, 2016, 24(2): 314-326. [CrossRef]

- Pauta-Calle, G., Velazco, M., Gutiérrez, D., Vázquez, G., Rivera, S., Morales, O., & Abril, A. Water quality assessment of rivers in the city of Cuenca in Ecuador. Maskana, 2019, 10 (2). 76-88. http://doi: 10.18537/mskn.10.02.08.

- Salinas, N., Briones, N., Quiroz, S., Peña, D., & Ortiz, Y. Characterization and Analysis of Water Quality in Urban Environments through the implementation of an Embedded System with IoT Technology. Revista Tecnológica ESPOL—RTE, 2024, 36(1). [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A., Vásquez, M., & Velandia, G. Evaluation of the microbiological quality of water for human consumption in the villages of El Alto del Águila and El Tunal in the municipality of Zipaquirá. Cundinamarca. Undergraduate thesis. Repositorio Universidad Colegio Mayor de Cundinamarca. Colombia. https://repositorio.universidadmayor.edu.co/bitstream/handle/unicolmayor/5719/Documento%20Proyecto%20de%20Grado.pdf?sequence=14&isAllowed=y.

| Water body | Site location | Coordinates | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bahia el Uno | B1 | Before the entrance to Bahia el Uno | 8°06′46”- 76° 43′22” |

| B2 | New canal—before the entrance to Bahía el Uno | 8°06′8.276”-76°43′38.5” | |

| B3 | Caño el Uno* | 8°06′31”- 76° 44′11” | |

| B4 | River mouth | 8°06′18”- 76° 44′20” | |

| Zapata River | Z1 | Upstream, away from the entrance to Zapata | 8°40′328”- 76° 37′59” |

| Z2 | Before entering to Zapata | 8°40′36”- 76° 38′42” | |

| Z3 | Zapata* | 8°40′33”- 76° 38′02” | |

| Z4 | River mouth | 8°44′10.0”-76°38′15” | |

| Hobo River | H1 | Upstream before the entrance to Hobo River | 8°49′09.7”-76° 26′30.9” |

| H2 | Pond | 8°59′48.6”- 76° 26′17.8” | |

| H3 | Hobo river* | 8°50′44.3”- 76° 26′27.7” | |

| H4 | River mouth | 8°50′45.9”- 76° 26′27.3” | |

| Damaquiel River | D1 | Last stream flowing into the river—Before Damaquiel. | 8°44′10.0”- 76° 36′23.3” |

| D2 | Entrance to the river | 8°44′08.2”- 76° 36′24” | |

| D3 | Damaquiel* | 8°44′22.5”- 76° 36′18.1” | |

| D4 | River mouth | 8°44′30.8”- 76° 36′14.3” | |

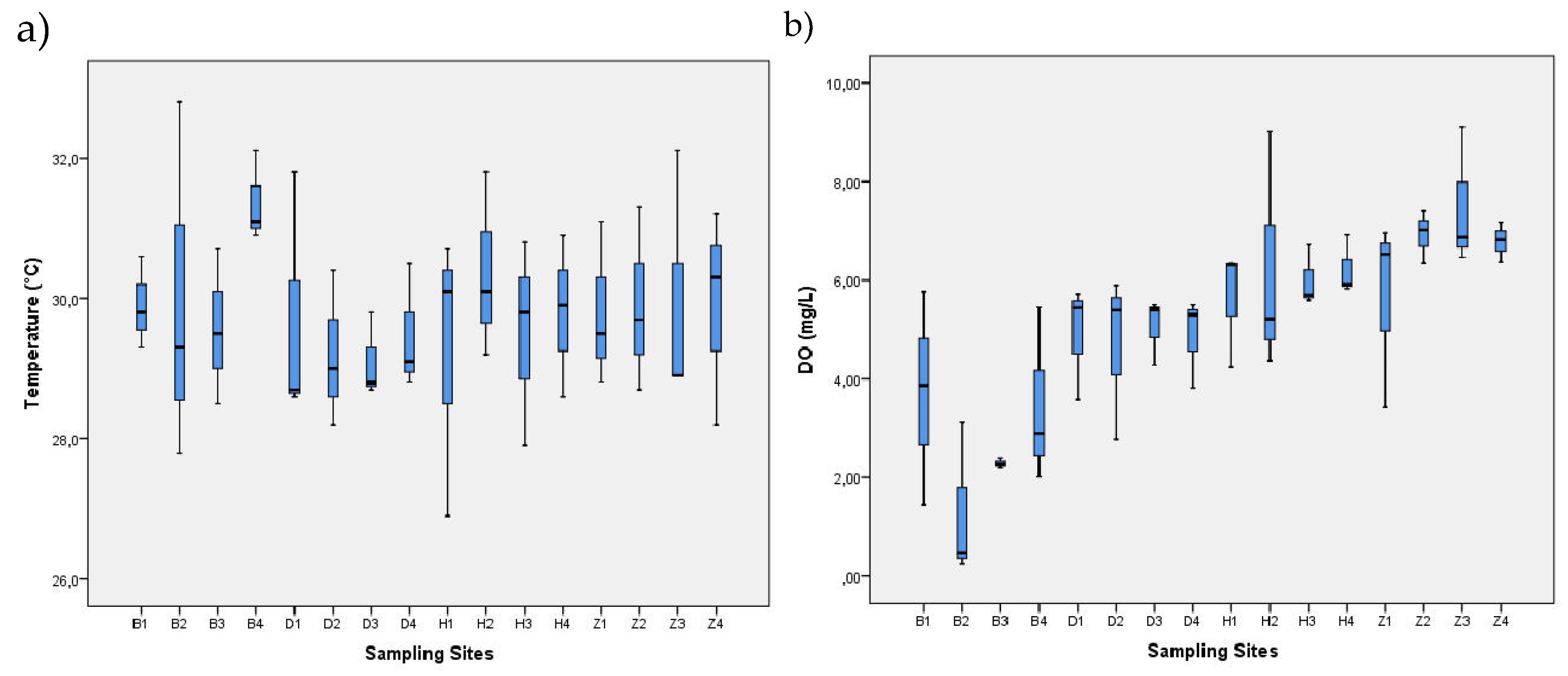

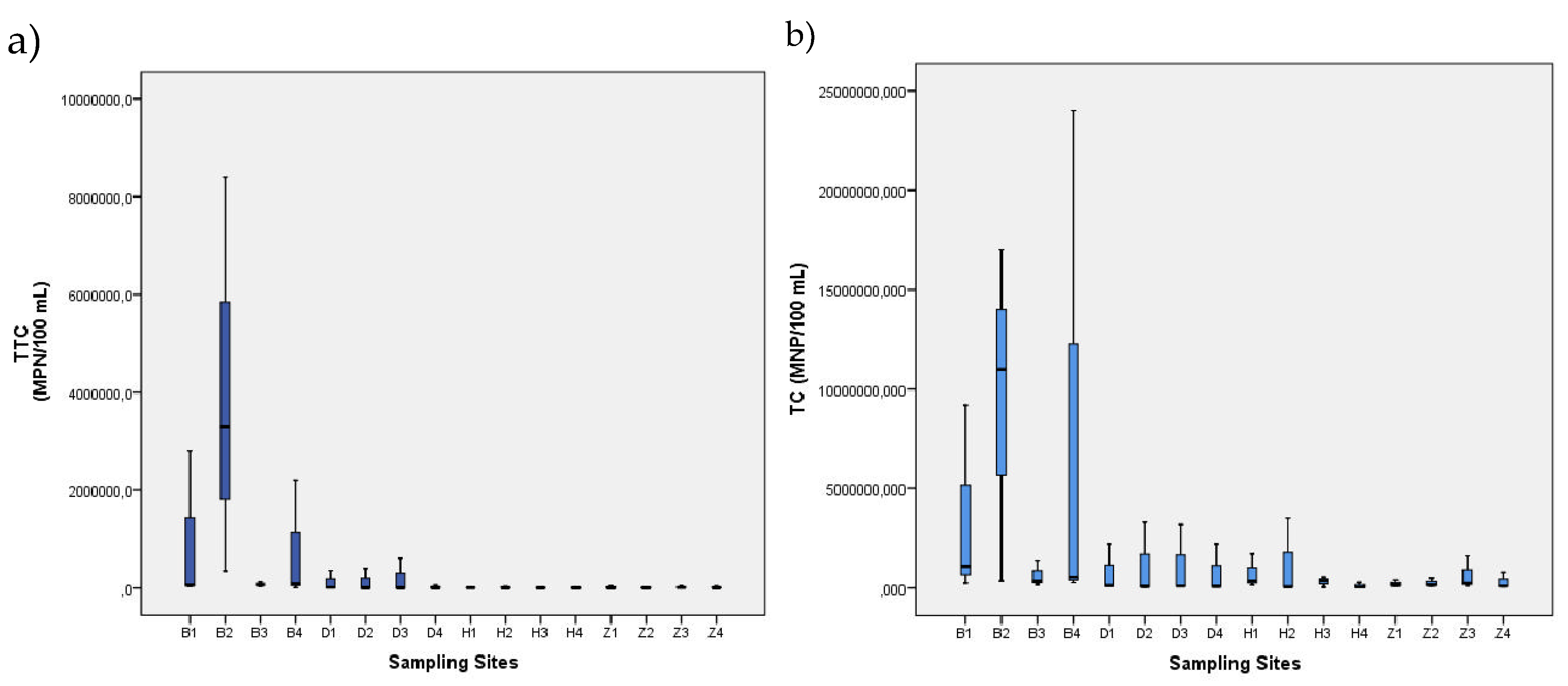

| Sampling / Month | Season | Water Temperature (°C) |

Dissolved Oxygen (mg/L) | pH | Total dissolved solids (mg/L) |

Thermotolerant coliforms (MPN/100 mL) | Total coliforms (MPN/100 mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—November | Dry (DS1) | 26.9–30.9 | 0.48–6.53 | 6.69–8.4 | 79.7- 15000 | 780–2200000 | 54000-24000000 |

| 2—January | Dry (DS2) | 29.8–32.8 | 0.25–9.11 | 6.97–7.8 | 125.8–12470 | 360–8400000 | 35000-11000000 |

| 3—April | Wet (WS1) | 27.8–31.1 | 2.27–7.02 | 7.00–7.99 | 3.73–699 | 4000–3300000 | 40000-17000000 |

| 4—August | Wet (WS2) | 29.0–33.7 | 0.26–8.17 | 7.31–7.87 | 98.8–>15000 | 20–6300000 | 78- 9200000 |

| Range | 26.9–33.7 | 0.25–9.11 | 6.69–8.4 | 19.85–>15000 | 78–8400000 | 78- 24000000 | |

| Mean ± SD | 30.0 ± 1.329 | 5.32 ± 2.05 | 7.51 ± 0.30 | 2777 ± 3964 | 399812 ± 1405339 | 1542043 ± 4097424 | |

| Reference | -—- | ˃3.0+ 4.0++ | 4.5–9.0▫ | -—- | ˂200* | 1000** | |

| Spearman’s Rho | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTC | TC | OD | TDS | Water Temperature |

||

|

TEC |

Correlation coefficient | 1.000 | .906 | -.495 | -.307 | -.270 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | . | .000 | .000 | .014 | .031 | |

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

|

TTC |

Correlation coefficient | .906 | 1.000 | -.484 | -.277 | -.294 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | .000 | . | .000 | .026 | .018 | |

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

|

DO |

Correlation coefficient | -.495 | -.484 | 1.000 | -.066 | .017 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | .000 | .000 | . | .607 | .892 | |

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

|

SDT |

Correlation coefficient | -.307 | -.277 | -.066 | 1.000 | .365 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | .014 | .026 | .607 | . | .003 | |

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

|

Water Temperature |

Correlation coefficient | -.270 | -.294 | .017 | .365 | 1.000 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | .031 | .018 | .892 | .003 | . | |

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).