Submitted:

24 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

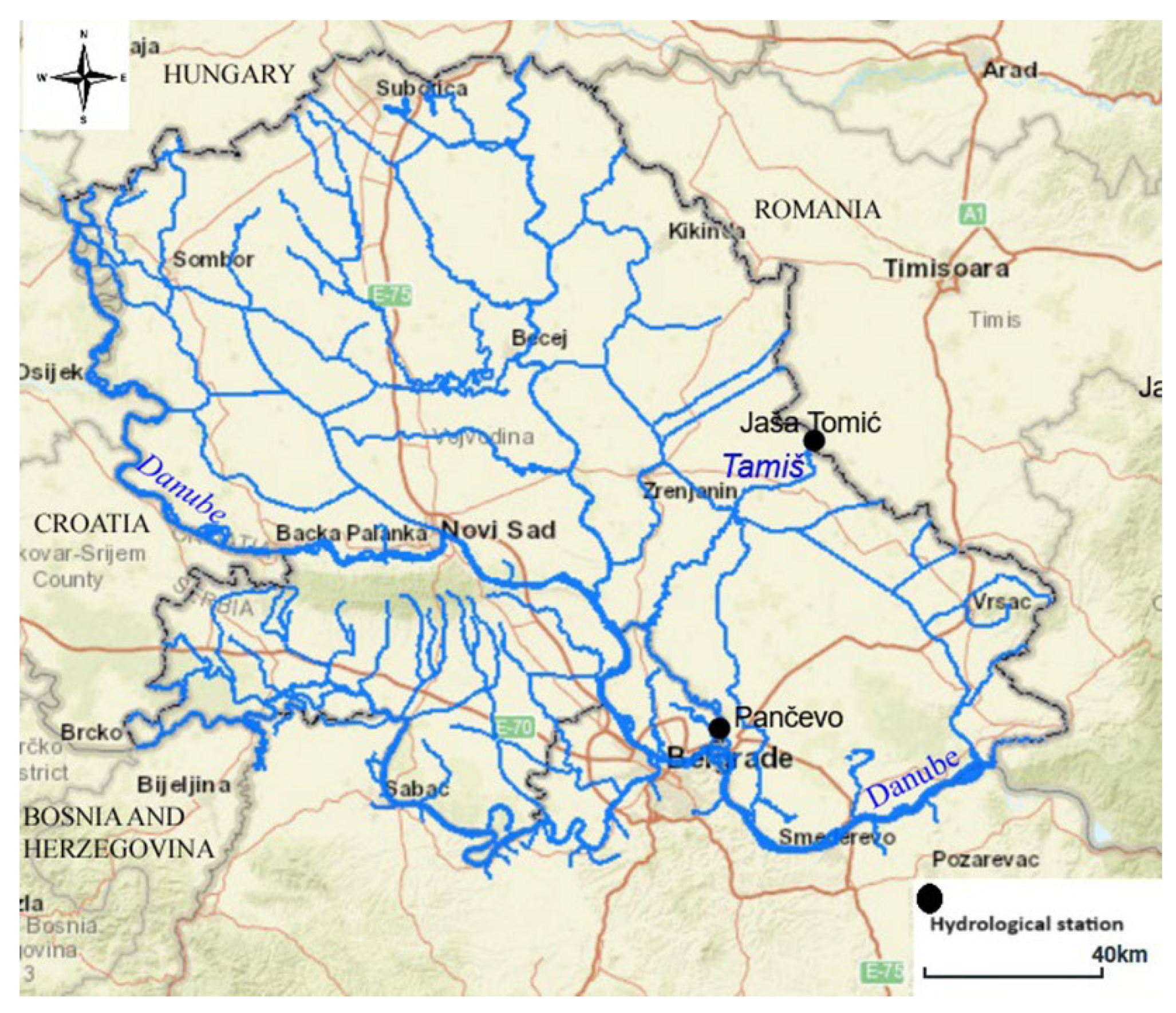

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data and Methods

2.3. Water Pollution Index (WPI)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Parameters Deviation from Class I

3.2. Water Pollution Index (WPI) Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, D.; Shao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Hou, H.; Quan, X. Integrated analysis of the water–energy–environmental pollutant nexus in the petrochemical industry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 14830–14842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valeev, T.K.; Rakhmanin, Y.A.; Suleimanov, R.A.; Malysheva, A.G.; Bakirov, A.B.; Rakhmatullin, N.R.; Rakhmatullina, L.R.; Daukaev, R.A.; Baktybaeva, Z.B. Experience on the environmental and hygienic assessment of water pollution in the territories referred to oil refining and petrochemical complexes. Hygiene and Sanitation 2020, 99, 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radelyuk, I.; Tussupova, K.; Klemeš, J.J.; Persson, K.M. Oil refinery and water pollution in the context of sustainable development: Developing and developed countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 302, 126987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzboon, K.; Abu Salem, Z.; Alshboul, Z.; Al-Tabbal, J.; Al Tarazi, E.; Alrawashdeh, K. Impacts of the petrochemical industries on groundwater quality. J. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 25, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostadinov, S.; Zlatic, M.; Dragicevic, S.; Novkovic, I.; Kosanin, O.; Borisavljevic, A.; Lakicevic, M.; Mladjan, D. Anthropogenic influence on erosion intensity changes in the Rasina river watershed-Central Serbia. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2014, 23, 254–263. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S. The analysis of groundwater nitrate pollution and health risk assessment in rural areas of Yantai, China. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Romero, D.C.; Domínguez, I.; Oviedo-Ocaña, E.R. Effect of agricultural activities on surface water quality from páramo ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 83169–83190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukate, S.; Wagh, V.; Panaskar, D.; Jacobs, J.A.; Sawant, A. Development of new integrated water quality index (IWQI) model to evaluate the drinking suitability of water. Ecol. Ind. 2019, 101, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njuguna, S.M.; Onyango, J.A.; Githaiga, K.B.; Gituru, R.W.; Yan, X. Application of multivariate statistical analysis and water quality index in health risk assessment by domestic use of river water. Case study of Tana River in Kenya. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 133, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babuji, P.; Thirumalaisamy, S.; Duraisamy, K.; Periyasamy, G. Human health risks due to exposure to water pollution: a review. Water 2023, 15, 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovljević, D. Serbian and Canadian water quality index of Danube river in Serbia in 2010. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijić SASA 2012, 62, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zou, Z.; Yan, A. Water quality assessment in Qu River based on fuzzy water pollution index method. Acta Sci. Circumst. 2016, 50, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milijašević Joksimović, D.; Gavrilović, B.; Obradović Lović, S. Application of the water quality index in the Timok River basin (Serbia). J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijić SASA 2018, 68, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenović-Ranisavljević, I.I.; Žerajić, S.A. Comparison of different models of water quality index in the assessment of surface water quality. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 15, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.H.; Robescu, D. Assessment of water quality of the Danube River using water quality indices technique. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2019, 18, 1727–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachroud, M.; Trolard, F.; Kefi, M.; Jebari, S.; Bourrié, G. Water quality indices: challenges and application limits in the literature. Water 2019, 11, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, T.D.; Kumarasamy, V.M. Development of water quality indices (WQIs): a review. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2020, 29, 2011–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calmuc, M.; Calmuc, V.; Arseni, M.; Topa, C.; Timofti, M.; Georgescu, L.P.; Iticescu, C. A comparative approach to a series of physico-chemical quality indices used in assessing water quality in the Lower Danube. Water 2020, 12, 3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanović Pešić, A.; Brankov, J.; Milijašević Joksimović, D. Water quality assessment and populations’ perceptions in the National park Djerdap (Serbia): key factors affecting the environment. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 2365–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanday, S.A.; Bhat, S.U.; Islam, S.T.; Sabha, I. Identifying lithogenic and anthropogenic factors responsible for spatio-seasonal patterns and quality evaluation of snow melt waters of the River Jhelum Basin in Kashmir Himalaya. Catena 2021, 196, 104853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouimouass, H.; Fakir, Y.; Tweed, S.; Sahraoui, H.; Leblanc, M.; Chehbouni, A. Traditional irrigation practices sustain groundwater quality in a semiarid piedmont. Catena 2022, 210, 105923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, E. A holistic framework of water quality evaluation using water quality index (wqi) in the Yihe river (China). Environ. Sci. Pollut. 2022, 29, 80937–80951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.H.R.B.; Ahsan, A.; Imteaz, M.; Shafiquzzaman, M.; Al-Ansari, N. Evaluation of the surface water quality using global water quality index (WQI) models: perspective of river water pollution. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukhabi, D.K.; Mensah, P.K.; Asare, N.K.; Pulumuka-Kamanga, T.; Ouma, K.O. Adapted water quality indices: limitations and potential for water quality monitoring in Africa. Water 2023, 15, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.S.; Pandya, D.M.; Shah, M. A systematic and comparative study of Water Quality Index (WQI) for groundwater quality analysis and assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 54303–54323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dippong, T.; Mihali, C.; Avram, A. Evaluating Groundwater Metal and Arsenic Content in Piatra, North-West of Romania. Water 2024, 16, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazheeva, Z.I.; Plyusnin, A.M.; Dampilova, B.V. Changes in water quality in the Modonkul River assessed by combinatory pollution index. Water Resour. 2024, 51, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dass, B.; Rao, M.S.; Sen, S. Hydrogeochemical characterization and water quality assessment of mountain springs: insights for strategizing water management in the lesser Indian Himalayas. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 57, 102126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Ren, B.; Wu, B.; Deng, X. Spatiotemporal dynamics and optimization of water quality assessment in the Nantong section of the Yangtze River Basin: A WQImin approach. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 57, 102106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Meng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Xia, L.; Zheng, H. Analysis of the temporal and spatial distribution of water quality in China’s major river basins, and trends between 2005 and 2010. Front. Earth Sci. 2015, 9, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yu, R.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Xue, H.; Hao, Y.; Wang, L. Temporal and Spatial Variation Trends in Water Quality Based on the WPI Index in the Shallow Lake of an Arid Area: A Case Study of Lake Ulansuhai, China. Water 2019, 11, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widodo, T.; Budiastuti, M.T.S.; Komariah, K. Water Quality and Pollution Index in the Grenjeng River, Boyolali Regency, Indonesia. Caraka Tani: Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 2019, 34, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Patra, P.K. Water pollution index – a new integrated approach to rank water quality. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 117, 106668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.K.K.M.B.; Singh, L.C.; Singh, N.D. Analysis of Seasonal Variation in Water Pollution Index of Nambul River, Manipur, North-East, India. International Journal of Lakes and Rivers, 2023, 16, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.T.; Liem, N.D.; Hieu, H.H.; Tam, H.T.; Mong, N.V.; Yen, N.T.M.; Yen, T.T.H.; Quang, N.X.; Luu, P.T. Assessment of long-term surface water quality in Mekong River estuaries using a comprehensive water pollution index. Environ. Nat. Resour. J. 2023, 21, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanović Pešić, A.; Brankov, J.; Milijašević Joksimović, D. Water quality assessment and populations’ perceptions in the National park Djerdap (Serbia): key factors affecting the environment. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 2365–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovljević, D.; Milanović Pešić, A.; Miljanović, D. Human impacts on water resources in the Lower Danube River Basin in Serbia. In The Lower Danube River: Hydro-environmental Issues and Sustainability; Negm, A., Zaharia, L., Ioana-Toroimac, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; pp. 195–251. [CrossRef]

- Popović, N.; Đuknić, J.; Čanak Atlagić, J.; Raković, M.; Marinković, N.; Tubić, B.; Paunović, M. Application of the Water Pollution Index in the Assessment of the Ecological Status of Rivers: a Case Study of the Sava River, Serbia. Acta Zool. Bulg. 2016, 68, 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Brankov, J.; Milijašević, D.; Milanović, A. The assessment of the surface water quality using the water pollution index: a case study of the Timok river (The Danube River basin), Serbia. Arch. Environ. Prot. 2012, 38, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milijašević Joksimović, D.; Vuletić, M. 2024. Assessing surface water quality of the Porečka River. In Zbornik radova – VI Kongres geografa Srbije sa medunarodnim ucešcem, Zlatibor, Serbia, 29–31 August 2024. [CrossRef]

- Milanović, A.; Milijašević, D.; Brankov, J. Assessment of polluting effects and surface water quality using water pollution index: A case study of hydro-system Danube-Tisa-Danube, Serbia. Carpath. J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2011, 6, 269–277. [Google Scholar]

- Milanović Pešić, A.; Jojić Glavonjić, T.; Denda, S.; Jakovljević, D. Sustainable Tourism Development and Ramsar Sites in Serbia: Exploring Residents’ Attitudes and Water Quality Assessment in the Vlasina Protected Area. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimon, M.N.; Gotia, S.R.; Gotia, S.L.; Borozan, A.; Popescu, R.; Gherman, V.D. Bacteriological studies on river Timis with a role in evaluating pollution. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 2009, 14, 284–288. [Google Scholar]

- Babović, N.; Marković, D.; Dimitrijević, V.; Marković, D. Some indicators of water quality of the Tamiš river. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 2011, 17, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lujić, J.; Matavulj, M.; Poleksić, V.; Rašković, B.; Marinović, Z.; Kostić, D.; Miljanović, B. Gill reaction to pollutants from the Tamiš River in three freshwater fish species, Esox lucius L. 1758, Sander lucioperca (L. 1758) and Silurus glanis L. 1758: a comparative study. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2015, 44, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute for Nature Conservation of Serbia. Pregled zaštićenih područja, 2024. https://zzps.rs/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/11-12-2023-Pregled-zasticenih-podrucja-RS.docx (accessed on 3 December 2024) (in Serbian).

- Gavrilović, Lj.; Dukić, D. Reke Srbije. Belgrade: Zavod za udžbenike, Serbia, 2002 (in Serbian).

- Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia. Hidrološki godišnjaci – 1. Površinske vode, 2003–2022. https://www.hidmet.gov.rs/latin/hidrologija/povrsinske_godisnjaci.php (accessed on 3 December 2024) (in Serbian).

- Serbian Environmental Protection Agency. Rezultati ispitivanja kvaliteta površinskih i podzemnih voda, 2011–2015, 2018–2022. https://sepa.gov.rs/publikacije/ (accessed on 3 December 2024) (in Serbian).

- Vode Vojvodine. Available online: https://gis.vodevojvodine.com/smartPortal/vodeVojvodineEksterna (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Marković, D.; Dražić, M.; Mitić, M.; Babović, N.; Jakovljev, Z.; Marković, D.; Dimitrijević, V.; Aranđelović, M.; Đorđević, S.; Aleksić, D.; Cvetković, D. Integralni katastar zagađivača reke Tamiš. Faculty of Applied Ecology Futura, Singidunum University, Belgrade, 2010.

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia, No. 93/2023. Uredba o proglašenju predela izuzetnih odlika „Potamišje”. https://pravno-informacioni-sistem.rs/eli/rep/sgrs/vlada/uredba/2023/93/5 (accessed on 3 December 2024) (in Serbian).

- Lyulko, I., Ambalova, T., Vasiljeva, T. To integrated water quality assessment in Latvia. In MTM (Monitoring Tailor-Made) III, Proceedings of International Workshop on Information for Sustainable Water Management; Institute for Inland Water Management and Waste Water Treatment (RIZA), Netherlands, 2000.

- Official Gazette of the RS, No 24/2014. Uredba o graničnim vrednostima prioritetnih i prioritetnih hazardnih supstanci koje zagađuju površinske vode i rokovima za njihovo dostizanje. https://pravno-informacioni-sistem.rs/eli/rep/sgrs/vlada/uredba/2014/24/3/reg (accessed on 3 December 2024) (in Serbian).

- Official Gazette of the RS, No 50/2012. Uredba o graničnim vrednostima zagađujućih materija u površinskim i podzemnim vodama i sedimentu i rokovima za njihovo dostizanje. https://pravno-informacioni-sistem.rs/eli/rep/sgrs/vlada/uredba/2012/50/1/reg (accessed on 3 December 2024) (in Serbian).

- Official Gazette of the RS, No. 74/2011 Pravilnik o parametrima ekološkog i hemijskog statusa površinskih voda i parametrima hemijskog i kvantitativnog statusa podzemnih voda. https://pravno-informacioni-sistem.rs/eli/rep/sgrs/ministarstva/pravilnik/2011/74/4/reg (accessed on 3 December 2024) (in Serbian).

- Official Gazete of the SRS, No 31/1982. Pravilnik o opasnim materijama u vodama. https://pravno-informacioni-sistem.rs/eli/rep/sgsrs/ministarstva/pravilnik/1982/31/1 (accessed on 3 December 2024) (in Serbian).

- Bilotta, G.S.; Brazier, R.E. Understanding the influence of suspended solids on water quality and aquatic biota. Water Res. 2008, 42, 2849–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tang, H.; Zhang, X.; Xue, X.; Zhu, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Z. Mitigation of nitrite toxicity by increased salinity is associated with multiple physiological responses: a case study using an economically important model species, the juvenile obscure puffer (Takifugu obscurus). Environ. Pollut. 2018, 232, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Management of the Republic of Serbia. Plan vodoprivrede na teritoriji Republike Srbije za period 2021. do 2027. godine, 2021. http://www.minpolj.gov.rs/download/Plan_upravljanja_-vodama_do_2027-FINAL.pdf?script=lat (accessed on 3 December 2024) (in Serbian).

- Ding, T.T.; Du, S.L.; Huang, Z.Y.; Wang, Z.J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.H.; Liu, S.S.; He, L.S. Water quality criteria and ecological risk assessment for ammonia in the Shaying River Basin, China. Ecotox. Environ Safe. 2021, 215, 112141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biliani, I.; Tsavatopoulou, V.; Zacharias, I. Comparative Study of Ammonium and Orthophosphate Removal Efficiency with Natural and Modified Clay-Based Materials, for Sustainable Management of Eutrophic Water Bodies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Unit | Class I |

| Dissolved Oxygen (DO) | mg /l | 8.5 |

| Oxygen Saturation (OS) | % | 90 |

| pH | 6.5–8.5 | |

| Suspended solids (SS) | mg /l | 25 |

| Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) | mg/l | 2 |

| Chemical Oxygen Demand (CODMn) | mg/l | 10 |

| Nitrites (NO2-), | mg/l | 0.01 |

| Ammonium (NH4+) | mg/l | 0.1 |

| Orthophosphates (PO43-) | mg/l | 0.02 |

| Sulphates (SO42-) | mg/l | 50 |

| Iron (Fe) | mg/l | 0.3 |

| Manganese (Mn) | mg/l | 0.05 |

| Nickel (Ni) | µg/l | 20 |

| Mercury (Hg) | µg/l | 1 |

| Copper (Cu) | µg/l | 2000 |

| Lead (Pb) | µg/l | 50 |

| Cadmium (Cd) | µg/l | 5 |

| Total Coliforms (TC) | N/100 ml | 500 |

| Class | Characteristics | WPI |

| I | Very pure | ≤0.3 |

| II | Pure | 0.3-1 |

| III | Moderately polluted | 1-2 |

| IV | Polluted | 2-4 |

| V | Impure | 4-6 |

| VI | Heavily impure | >6 |

| Pančevo | ||||||||||||||||||

| Year | DO | OS | pH | SS | BOD | CODMn | NO2- | NH4+ | PO43- | SO42- | Fe | Mn | Ni | Hg | Cu | Pb | Cd | TC |

| 2011 | 1.138 | 0.943 | 0.929 | 0.732 | 0.895 | 0.48 | 1.9 | 1.33 | 5.3 | 1.326 | 0.347 | 0.6 | 0.168 | 0.1 | 0.002 | 0.01 | 0.005 | 21.067 |

| 2012 | 1.175 | 1.022 | 0.941 | 0.648 | 0.885 | 0.488 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 4.1 | 0.72 | 0.17 | 0.28 | 0.511 | 0.1 | 0.002 | 0.01 | 0.004 | 6.3 |

| 2013 | 1.15 | 0.959 | 0.929 | 0.604 | 0.82 | 0.53 | 1.8 | 1.18 | 4.9 | 0.748 | 1.34 | |||||||

| 2014 | 201.013 | 0.891 | 0.929 | 1.128 | 0.845 | 0.605 | 1.6 | 1.25 | 4.35 | 0.75 | 0.353 | 0.56 | 0.511 | 0.1 | 0.005 | 0.014 | 0.006 | 39.8 |

| 2015 | 1.125 | 0.942 | 0.929 | 1.3 | 1.055 | 0.513 | 1.8 | 1.14 | 3.8 | 0.948 | 0.29 | 0.48 | 0.171 | 0.1 | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.006 | 149.5 |

| Jaša Tomić | ||||||||||||||||||

| Year | DO | OS | pH | SS | BOD | CODMn | NO2- | NH4+ | PO43- | SO42- | Fe | Mn | Ni | Hg | Cu | Pb | Cd | TC |

| 2011 | 2.088 | 1.022 | 0.929 | 1.456 | 0.922 | 0.41 | 1.3 | 0.84 | 1.95 | 1.062 | 0.247 | 1.68 | 0.59 | 0.046 | 0.002 | 0.01 | 0.005 | 2.096 |

| 2012 | 1.175 | 1.03 | 0.918 | 1.064 | 0.841 | 0.36 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 1.15 | 1.442 | 0.177 | 0.82 | 0.26 | 0.114 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.004 | 0.25 |

| 2013 | 1.254 | 1.071 | 0.926 | 1.953 | 0.795 | 0.456 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 2.35 | 0.757 | 7.55 | |||||||

| 2014 | 1.203 | 1.011 | 0.935 | 2.107 | 0.763 | 0.575 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 2.5 | 0.715 | 0.41 | 0.64 | 0.495 | 0.1 | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.005 | 13.333 |

| 2015 | 1.188 | 1.036 | 0.941 | 1.272 | 0.704 | 0.415 | 1.5 | 0.69 | 1.75 | 0.884 | 0.28 | 0.42 | 0.206 | 0.1 | 0.002 | 0.014 | 0.005 | 3.69 |

| 2018 | 1.2 | 1.009 | 0.918 | 1.852 | 0.625 | 0.498 | 1.6 | 0.89 | 1.7 | 0.845 | 2 | 1 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.005 | 1.823 |

| 2019 | 1.200 | 0.981 | 0.906 | 0.828 | 0.692 | 0.449 | 1.3 | 1.25 | 1.85 | 1.035 | 0.697 | 1.14 | 1.745 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.016 | 0.005 | 1.488 |

| 2020 | 1.225 | 1.028 | 0.918 | 0.808 | 0.823 | 0.328 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1 | 0.855 | 0.613 | 0.82 | 0.494 | 0.07 | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.005 | 1.84 |

| 2021 | 1.249 | 1.061 | 0.908 | 1.252 | 0.775 | 0.435 | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.953 | 0.183 | 0.48 | 0.246 | 0.07 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.015 | 3.895 |

| 2022 | 1.231 | 1.025 | 0.902 | 1.340 | 0.84 | 0.498 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.367 | 0.8 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.005 | 0.013 | 0.022 | 1.584 |

| Hydrological Station | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| Pančevo | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 3 | 9.1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| IV | III | III | IV | VI | ||||||

| Jaša Tomić | 0.93 | 0.78 | 1.81 | 1.49 | 0.83 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.82 |

| II | II | III | III | II | II | II | II | II | II |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).