Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Water as Weapons

1.2. The Main Use of Heavy Metals in Military Operations

2. Materials and Methods

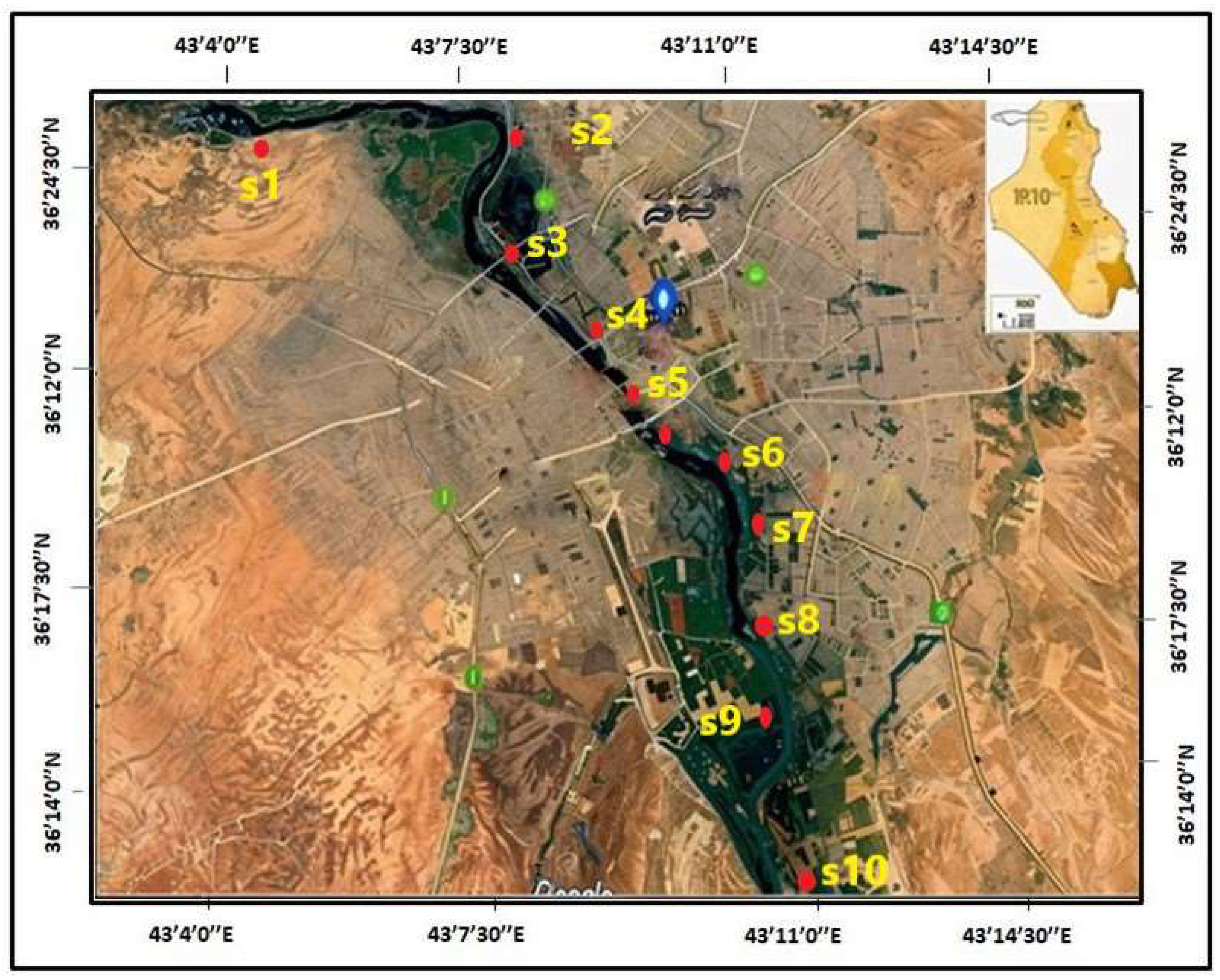

2.1. Investigation Area

2.2. Sampling Procedure

2.3. Field Measurement Parameters

2.4. Laboratory Measurement Parameters

2.6. Assessment of Water Quality and Heavy Metals Consents

2.6.1. Calculation of the CCME WQI

2.6.2. Heavy Metal Pollution INDEX (HPI)

3. Results and Discussions

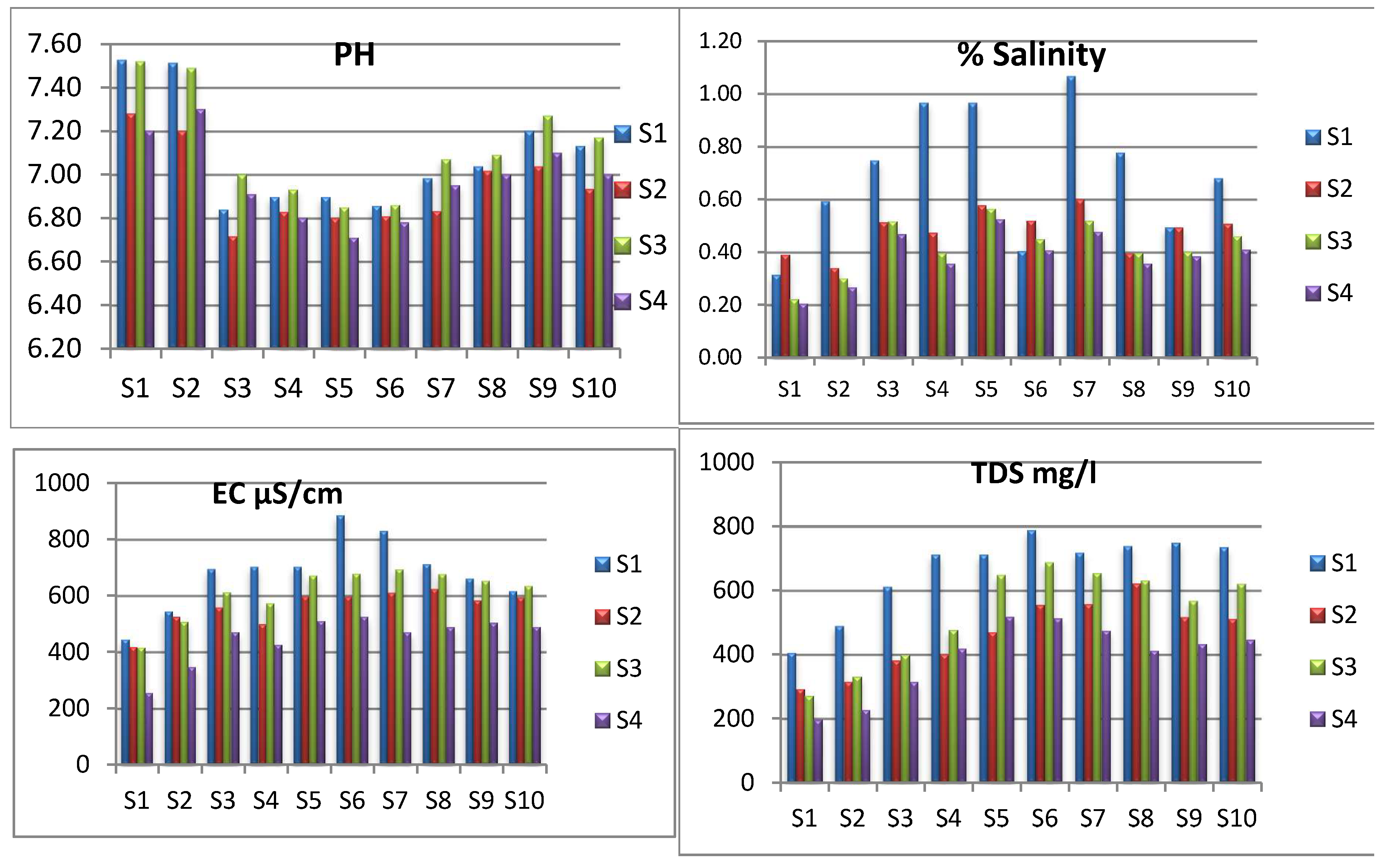

3.1. Physico-Chemical Characteristics of All Parameters

3.1.1. pH Value

3.1.2. E.C., TDS, Salinity

3.1.3. COD

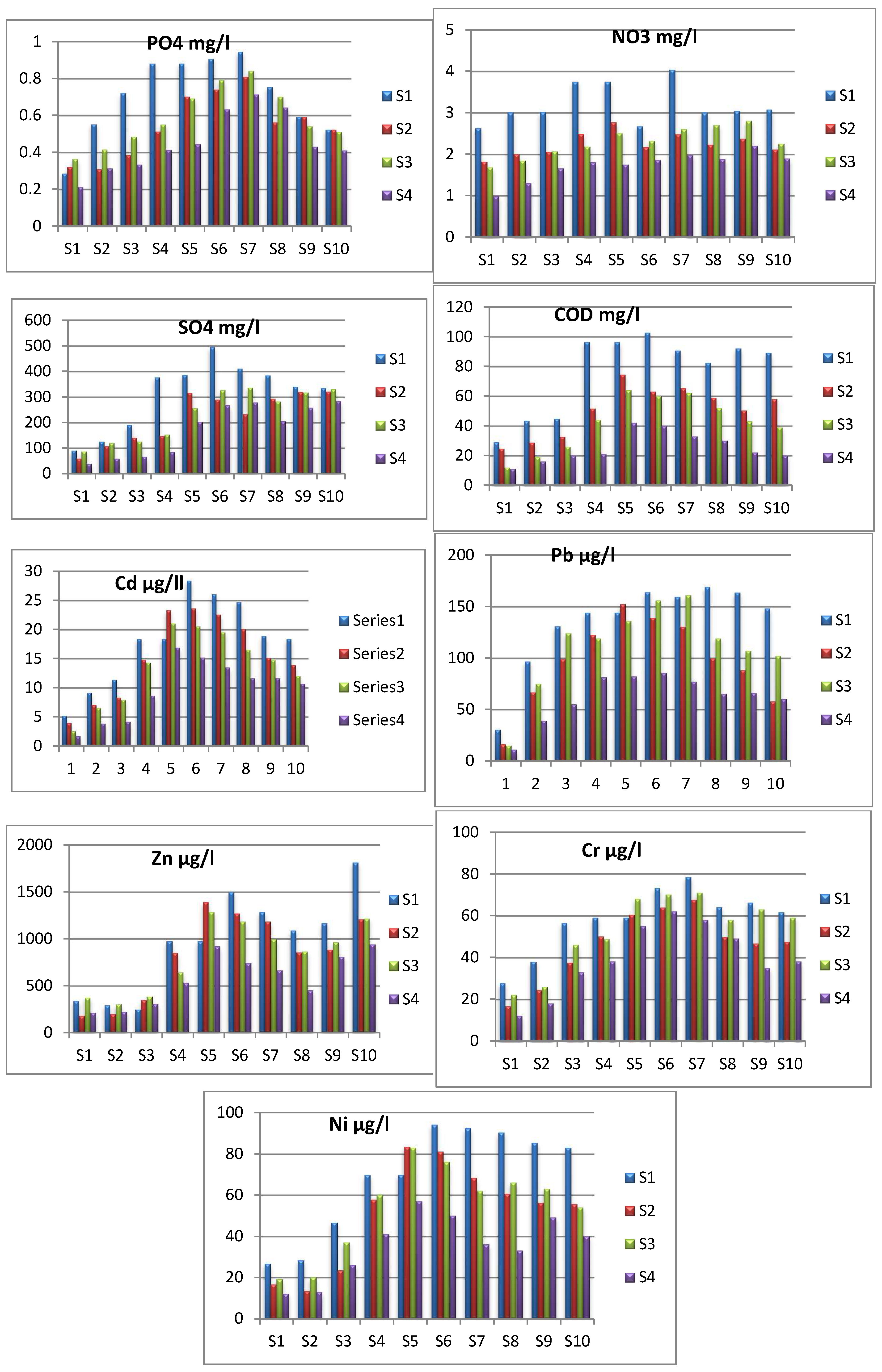

3.1.4. , , as Anions,

3.1.5. Heavy Metals

3.2. Statistic Analysis

3.2.1. Test Values for Seasonal and Annual Variations

3.2.2. Comparison of Heavy Metal Concentration with Previous Study

3.3. Water Quality Evaluation

3.3.1. CCME WQI in River’s Water Samples

3.3.2. Heavy Metal Pollution Index HPI in River’s Water Samples

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AccuWeather. (2024). Mosul - Current Air Quality. Pennsylvania. https://www.accuweather.com.

- Al-Ahmady, K Amina F. Farhan, Nawfal Abd-Aljabbar Al-Masry (2020). Assessment of Tigris River Water Quality in Mosul for Drinking and Domestic Use by Applying CCME Water Quality Index. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 737. [CrossRef]

- Al-Dabbas, M. (2021). Hydrochemical Evaluation of the Tigris River from Mosul to South of Baghdad Cities, Iraq. International Journal of Environment and Climate Change. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353486819.

- Alfadehl, M., & Sultan, F. (2019). Evaluation of the East Mosul Old Water Treatment Plant. International Journal of Environment & Water.

- Alfadhl, M. (2015). Descending of Tigris River Water Quality: Causes and Impacts. International Journal of Environment and Water, 4(4). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317402132.

- Alfadhl, M. (2020). Pollution Investigation on Tigris River within Mosul Area, Iraq. Plant Archives, 20(S2), 1273–1277. http://www.plantarchives.org/SPL%20ISSUE%2020-2/202__1273-1277_. Aljanabi, Z. Z., Al-Obaidy, A. M. J., & Fikrat, M. (2021). A Brief Review of Water Quality Indices and Their Applications. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science.

- Al-Masri, M., & Alfadhel, M. (2014). Pollutant Variation through Tigris River in Mosul City. International Journal of Interdisciplinary Research and Innovations, 2(4), 38–58. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317402047_Pollutant_Variation_through_Tigris_River_in_Mosul_City.

- Al-Meshhadani. (2012). Study of Some Characteristics of Tigris River Between Mosul City and Hamam Al-Aleel Province. Iraq Academic Scientific Journal, 23(8), 56–67. https://www.iraqjournals.com/article_64524_0.

- Al-Sarraj, E., Jankeer, M., & Al-Rawi, S. (2019). Estimation of the Concentrations of Some Heavy Metals in Water and Sediments of Tigris River in Mosul City. Environmental Science, 28(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sheraety, R. M., Al-Mallah, A. Y., & Hussien, A. K. (2023). Spatial Distribution of Heavy Metals in Soil. Iraqi Geological Journal, 56(1C). [CrossRef]

- Al-Saffawi, A. Y. (2018b). Application of CCME WQI to Assess the Environmental Status of Tigris River Water for Aquatic Life within Nineveh Governorate, North Iraq. Al-Utroha Journal, (5), 13–25.

- Al-Saffawi, A., et al. (2021). Application of Weight Mathematical Model (WQI) to Assess Water Quality for Irrigation: A Case Study of Tigris River in Nineveh Governorate. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 735.

- Altahaan, Z., & Dobslaw, D. (2024a). Assessment of the Impact of War on Concentrations of Pollutants and Heavy Metals and Their Seasonal Variations in Water and Sediments of the Tigris River in Mosul/Iraq. Environments, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Altahaan, Z. F., & Dobslaw, D. (2024b). Assessment of Post-War Groundwater Quality in Urban Areas of Mosul City/Iraq. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 21(03), 2461–2481. [CrossRef]

- Altahaan, Z., & Dobslaw, D. (2025). Post-War Air Quality Index in Mosul City, Iraq. Atmosphere, 16(2), 135. [CrossRef]

- APHA, AWWA, & WEF. (1998). Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater (23rd ed.). American Public Health Association. https://www.pdfdrive.com/standard-methods-for-the-examination-of-water-and-wastewater-e11311928.html.

- Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment. (2001). Canadian Water Quality Guidelines for the Protection of Aquatic Life: CCME Water Quality Index 1.0, User’s Manual. https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1165076.

- Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment. (2017). CCME Water Quality Index: User’s Manual—2017 Update. https://ccme.ca/en/res/wqimanualen.pdf.

- Chiamsathit, C., Supunnika, A., & Thammarakcharoen, S. (2020). Heavy Metal Pollution Index for Assessment of Seasonal Groundwater Supply Quality in Hillside Area, Kalasin. Applied Water Science, 10, 142. [CrossRef]

- DIN EN ISO. (2016). Water Quality — Sampling — Part 6: Guidance on Sampling of Rivers and Streams. International Organization for Standardization.

- Danboos, A., Jaafar, O., & El-Shafie, A. (2017). Water Scarcity Analysis, Assessment and Alleviation: New Approach for Arid Environment. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research, 12(18), 7536–7545. https://www.ripublication.com/ijaer17/ijaerv12n18_59.

- Edokpayi, J. N., Odiyo, J. O., Popoola, E. O., & Msagati, T. A. M. (2017). Evaluation of Temporary Seasonal Variation of Heavy Metals and Their Potential Ecological Risk in Nzhelele River, South Africa. Open Chemistry, 15, 272–282. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/chem-2017-0033/html.

- Ewaid, S. (2016). Water Quality Assessment of Al-Gharraf River, South of Iraq by the Canadian Water Quality Index (CCME WQI). Iraqi Journal of Science, 57(2A), 878–885. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305511602_.

- Iqbal, M., Iqbal, M. M., Li, L., Hussain, S., Lee, J. L., Mumtaz, F., ... & Dilawar, A. (2022). Analysis of Seasonal Variations in Surface Water Quality over Wet and Dry Regions. Water, 14, 1058. [CrossRef]

- Magri, P. (2017). After Mosul, Re-Inventing Iraq. Report study submitted for ISPI Executive. https://web.archive.org/web/20180421160433id_/http://www.ledizioni.it/stag/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Iraq_web_DEFDEF.pdf.

- Jo, C. D., & Kwon, H. G. (2023). Temporal and Spatial Evaluation of the Effect of River Environment Changes Caused by Climate Change on Water Quality. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 30, 103066. [CrossRef]

- Kingdon, M. J., Bootsma, J., & Mwita, B. M. (1999). River Discharge and Water Quality. Environment Canada, National Water Research Institute.

- Koushali, H., Mastouri, R., & Khaledian, M. R. (2023). Impact of Precipitation and Flow Rate Changes on the Water Quality of a Coastal River. Shock and Vibration, 2021, Article ID 6557689. [CrossRef]

- Lazaridou-Dimitriadou, M. (2002). Seasonal Variation of the Water Quality of Rivers and Streams of Eastern Mediterranea. Web Ecology, 3, 20–32.

- calculation of its pollution index for Uglješnica River, Serbia. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 97(5), 737–774. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308215236.

- Mohan, S. V., Nithila, P., & Reddy, S. J. (1996). Estimation of heavy metals in drinking water and development of heavy metal pollution index. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A, 31, 283–289. [CrossRef]

- Ojok, W., Wasswa, J., & Ntambi, E. (2017). Assessment of seasonal variation in water quality in River Rwizi using multivariate statistical techniques, Mbarara Municipality, Uganda. Journal of Water Resource and Protection, 9, 83–97. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jwarp.

- Othman, K., Bilal, A. A., & Sulaman, Y. I. (2012). Morphologic characteristics of Tigris River with at Mosul City. Tikrit Journal of Engineering Sciences, 19(3), 36–54. [CrossRef]

- Pax for Peace. (2017). Living under a black sky: Conflict pollution and environmental health concerns in Iraq. https://paxforpeace.nl/publications/living-under-a-black-sky/.

- Phadatare, S., & Gawande, S. (n.d.). Review paper on development of water quality index. International Journal of Engineering Research.

- Prasad, B., & Kumari, S. (2008). Heavy metal pollution index of groundwater of an abandoned open cast mine filled with fly ash: A case study. Mine Water and the Environment, 27(4), 265–267. [CrossRef]

- Razaghi, M., Taherizadh, M. R., & Mashjoor, S. (2018). Seasonal variation in heavy metal concentrations in sediment from Khalasi Estuary, Hormozgan, Iran. Indian Journal of Fisheries, 65(3), 130–134. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330686305.

- Reza, R., & Singh, G. (2010). Assessment of heavy metal contamination and its indexing approach for river water. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 7(4). [CrossRef]

- Islam, S., Uddin, K., Tareq, S. M., Shammi, M., Kamal, A. K. I., Sugano, T., Tanaka, S., & Kuramitz, H. (2015). Alteration of water pollution level with the seasonal changes in mean daily discharge in three main rivers around Dhaka City, Bangladesh. Environments, 2(3), 280–294. [CrossRef]

- Stiftung Wissenschaft Und Politik (SWP). (2016). Water as weapon: IS on the Euphrates and Tigris. https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/water-as-weapon-is-euphrates-tigris.

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). (2017). Environmental issues in areas retaken from ISIS in Mosul, Iraq: Rapid scoping mission (July - August). https://reliefweb.int/report/iraq/technical-note-environmental-issues-areas-retaken-isil-mosul-iraq-rapid-scopying-mission¶.

- UN-Habitat. (2016). City profile of Mosul, Iraq: Multi-sector assessment of a city under siege. https://unhabitat.org/city-profile-of-mosul-iraq-multi-sector-assessment-of-a-city-under-siege.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2023). Climate change, environmental degradation, conflict, and displacement in the Arab States region. https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2023-06.

- UNEP & OCHA. (2016). A rapid overview of environmental and health risks related to chemical hazards in the Mosul humanitarian response. https://reliefweb.int/report/iraq/rapid-overview-environmental-and-health-risks-related-chemical-hazards-mosul.

- UNEP. (2018). Mosul debris management assessment. https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/mosul-debris-management-assessment.

- Water Quality Australia. (2013). Characterising the relationship between water quality and water quantity. https://www.waterquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/characterising.pdf.

- Action Against Hunger Iraq. (2022/2023). Water scarcity index for Ninewa Governorate, Iraq. https://www.actioncontrelafaim.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Drought-Prediction-Tool-2022-ACF-Iraq.pdf.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2004). Guidelines for drinking-water quality (2nd ed., pp. 133–415). https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/38551.

- Al-Rawi, S. M. (2005). Contribution of man-made activities to the pollution of the Tigris within Mosul area, Iraq. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2(2), 245–250. [CrossRef]

- https://butlerms.com/education-blog/sewage-parameters-4-part-1-phosphorus-p.

- Fadhel, M. N. (2020). Pollution investigation on Tigris River within Mosul area, Iraq. Plant Archives, 20(2), 1273–1277.

- Hu, S., Lian, F., & Wang, J. (2019). Effect of pH to the surface precipitation mechanisms of arsenate and cadmium on TiO₂. Science of the Total Environment, 666, 956–963. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sarraj, E. S. J. H. (2013). Study of the pollution of the Tigris River with various wastes within the city of Mosul and their impact on a number of local fish (PhD thesis, University of Mosul, Iraq).

- Ahmed, W. A. (2013). Study of the potential pollution with heavy metals and some environmental factors in the water of the Tigris River and some main branches in Maysan Governorate, southern Iraq. Basra Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 26(1), 401–409.

- Shukry, H. M., Rahim, A., Jassem, G. H., Hassan, A. A., Asaad, J. I., & Ahmed, N. A. N. (2011). Study of the pollution of the Tigris River in Baghdad governorate with some heavy metals (zinc and lead) and evaluation of its chemical and biological quality. Journal of Biotechnology Research Center, 5(2), 5–14.

- Kannah, A. M. A., & Shihab, H. F. A. (2022). Heavy metals levels in the water of the Tigris River in the city of Mosul, Iraq. Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology & Fisheries, 26(6), 1007–1020.

- Al-Yazji, Y. M., & Mahmoud, H. J. (2008). Study of the qualitative characteristics and archaeological elements of the water of the Tigris River in the city of Mosul. Iraqi Journal of Earth Sciences, 8, 33–49.

- Malakootian, M., Jaafarzadeh, N. A., & Hossaini, H. (2011). Efficiency of perlite as a low-cost adsorbent applied to removal of Pb and Cd from paint industry effluent. Desalination and Water Treatment, 26, 243–249. [CrossRef]

- McTee, M., Parish, C. N., Jourdonnais, C., & Ramsey, P. (2023). Weight retention and expansion of popular lead-based and lead-free hunting bullets. Science of the Total Environment, 904, 166288. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Song, J., Soons, J. A., Thompson, R. M., & Zhao, X. (2020). Pilot study on deformed bullet correlation. Forensic Science International, 306, 110098. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M. K., Prabhakar, N. G., Chandrika, G., Mohan, B. M., & Nagendrappa, G. (2011). Microscopic and spectrometric characterizations of trace evidence materials present on the discharged lead bullet and shot – A case report. Journal of the Saudi Chemical Society, 15, 11–18. [CrossRef]

- Gümgüm, B., Ünlü, E., Akba, O., Yildiz, A., & Namli, O. (2001). Copper and zinc contamination of the Tigris River (Turkey) and its wetlands. Archives of Nature Conservation and Landscape, 40(3), 233–239.

- Khudhair, M. F., Ahmed, F., Dawod, A., & Abd, W. M. (2018). Evaluation of irrigation water quality index for Tigris River and pollution levels of heavy metals in Baghdad. Research Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical Sciences, 9(6), 993–1000.

- Rasheed, K. A., Flayyh, H. A., & Dawood, A. T. (2017). Study the concentrations of Ni, Zn, Cd, and Pb in the Tigris River in the city of Baghdad. International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology, 2(1), 196–201. [CrossRef]

- Barker, A. J., Clausen, J. L., Douglas, T. A., Bednar, A. J., Griggs, C. S., & Martin, W. A. (2021). Environmental impact of metals resulting from military training activities: A review. Chemosphere, 265, 129110. [CrossRef]

- Al-Tamimi, M. H., Kadhim, H. H., & Al-Hello, A. Z. A. (2022). Assessment of environmental pollution by heavy elements in the sedimentary at Abu Al-Kahsib River in Basrah province-southern Iraq. Marsh Bulletin, 17(2), 114.

- Al-Heety, L. F. D., Hasan, O. M., & Al-Heety, E. A. M. S. (2021). Heavy metal pollution and ecological risk assessment in soils adjacent to electrical generators in Ramadi City, Iraq. Iraqi Journal of Science, 62(4), 1077–1087. [CrossRef]

- Skalny, A. V., Aschner, M., Bobrovnitsky, I. P., Chen, P., Tsatsakis, A., Paoliello, M. M., Buha, D. A., & Tinkov, A. A. (2021). Environmental and health hazards of military metal pollution. Environmental Research, 201, 111568. [CrossRef]

- Kahle, H. (1993). Response of roots of trees to heavy metals. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 33(1), 99–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/0098-8472(93)90059-OThe National News (2022). Mosul’s island of tranquility: the forst still recovering from ISIS war. Published 2022/03/03. https://www.thenationalnews.com/mena/2022/03/03/mosuls-island-of-tranquillity-the-forest-still-recovering-from-isis-war/.

- ClimeChart. (2024). Climate change chart of Mossul, Iraq. Retrieved from https://www.climechart.com/en/climate-change/mossul/iraq.

- Aljanabi, Z. Z., Hassan, F. M., & Al-Obaidy, A. H. M. J. (2022). Heavy metals pollution profiles in Tigris River within Baghdad city. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1088, 012008. [CrossRef]

- ASTM International. (2018). Standard specification for zinc coating (hot-dip galvanized) on iron and steel products (ASTM A123/A123M).

- Defense Logistics Agency (DLA). (2021). Nickel-based alloys in defense applications. Retrieved from https://www.dla.mil/.

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). (2002). Lead in military applications. London: DEFRA Publications.

- International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). (2005). Radiation protection and safety in military environments (IAEA Safety Reports Series No. 40).

- Military Handbook (MIL-HDBK-5H). (2003). Metallic materials and elements for aerospace vehicle structures. U.S. Department of Defense.

- National Defense Industrial Association (NDIA). (2019). Advanced materials for defense systems. NDIA Technical Report.

- NATO. (2020). Energy storage solutions for military operations (STO Technical Report TR-AVT-323).

- Society for Protective Coatings (SSPC). (2015). Chromium-based coatings for military infrastructure (SSPC-Paint 20).

- U.S. Army Materiel Command. (2016). High-performance materials for combat systems (AMC Pamphlet 750-3).

- U.S. Department of Defense (DoD). (2017). Battery technologies for military use (DoD Directive 4270.5).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (2006). Lead in ammunition: Environmental and health impacts (EPA/600/R-06/042).

| Site No. | Location names | Latitude N |

Longitude E |

Describtion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Al Kuba | 36.398501 | 43.074622 | Residential area |

| S2 | Alrashidia | 36.39606 | 43.114278 | Agricultural area |

| S3 | Third bridge | 36.363435 | 43.114976 | Recreation area |

| S4 | Fifth bridge | 36.35485 | 43.12616 | Recreation area |

| S5 | Old bridge | 36.345667 | 43.136953 | Commercial +residential |

| S6 | Aljumhoria bridge | 36.340904 | 43.145025 | Residential area |

| S7 | Fourth bridge | 36.332283 | 43.152415 | Residential area |

| S8 | Jarimjah | 36.298735 | 43.176358 | Agricultural area |

| S9 | Albosaef | 36.277681 | 43.163921 | Agricultural area |

| S10 | Hammam Al aleel | 36.160292 | 43.263505 | Residential area |

| Suitability | class | CCME WQI Value | Water quality description |

| Excellent | 1 | 95-100 |

water quality is protected with a virtual absence of threat or impairment, conditions very close to natural or pristine levels. |

| Good | 2 | 94-80 |

water quality is protected with only a minor degree of threat or impairment; conditions rarely depart from natural or desirable levels. |

| Fair | 3 | 79-65 |

water quality is usually protected, but occasionally threatened or impaired; conditions sometimes depart from natural or desirable levels. |

| Marginal | 4 | 64-50 |

water quality is frequently threatened or impaired; conditions often depart from natural or desirable levels. |

| Poor | 5 | 49-0 |

water quality is almost always threatened or impaired; conditions usually depart from natural or desirable levels. |

| HPI | Classification |

| <25 | Excellent |

| 26-50 | Good |

| 51-75 | Poor |

| 76-100 | Very poor |

| >100 | Unsuitable |

| 2022 | PH | E.c µS/cm | TDS mg/l | Sal. % |

COD mg/l | PO4 mg/l | NO3 mg/l | SO4 mg/l | Cd µg/l |

Pb µg/l |

Zn µg/l |

Cr µg/l |

Ni µg/l |

|

| WHO std. | 6.5-8.5 | 1400 | 1000 | 1% | 100 | 0.4 | 50 | 250 | 5 | 10 | 5000 | 50 | 20 | |

| S1 | Mean | 7.5 | 431.3 | 348.7 | 0.4 | 26.8 | 0.3 | 2.2 | 74.0 | 4.5 | 23.0 | 258.4 | 22.2 | 21.7 |

| ±Sd | 0.69 | 89.9 | 39.9 | 0.34 | 5.96 | 0.114 | 1.06 | 55.11 | 3.82 | 4.98 | 91.78 | 5.78 | 6.58 | |

| S2 | Mean | 7.4 | 534.3 | 402.0 | 0.5 | 36.0 | 0.4 | 2.5 | 115.8 | 8.1 | 81.6 | 159.3 | 31.2 | 20.8 |

| ±Sd | 0.57 | 83.65 | 98.49 | 0.33 | 6.41 | 0.104 | 0.57 | 29.96 | 4.58 | 6.18 | 100.78 | 5.48 | 5.18 | |

| S3 | Mean | 7.0 | 625.8 | 496.5 | 0.6 | 38.7 | 0.6 | 2.5 | 164.8 | 9.8 | 114.6 | 146.5 | 47.0 | 35.0 |

| ±Sd | 0.77 | 107.01 | 73.25 | 0.33 | 6.41 | 0.104 | 0.57 | 29.96 | 4.8 | 6.59 | 137.66 | 5.8 | 5.47 | |

| S4 | Mean | 7.0 | 600.2 | 556.2 | 0.7 | 74.0 | 0.7 | 3.1 | 190.0 | 16.5 | 133.1 | 910.7 | 54.5 | 63.7 |

| ±Sd | 0.79 | 151.88 | 51.88 | 0.32 | 4.62 | 0.074 | 0.44 | 22 | 4.28 | 5.24 | 96.46 | 22.94 | 7.04 | |

| S5 | Mean | 6.9 | 706.3 | 602.2 | 0.6 | 91.0 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 344.7 | 25.0 | 165.1 | 1544.5 | 62.2 | 90.5 |

| ±Sd | 0.9 | 187.9 | 92.97 | 0.4 | 13.88 | 0.104 | 0.57 | 76.13 | 7.51 | 3.36 | 226.79 | 14.33 | 12.02 | |

| S6 | Mean | 6.8 | 740.2 | 670.8 | 0.5 | 82.8 | 0.8 | 2.4 | 336.5 | 26.0 | 151.3 | 1381.6 | 68.5 | 87.5 |

| ±Sd | 0.78 | 173.25 | 20 | 0.33 | 6.41 | 0.104 | 0.57 | 29.96 | 4.55 | 5.68 | 120.26 | 26.54 | 7.8 | |

| S7 | Mean | 7.0 | 719.8 | 637.0 | 0.8 | 78.0 | 0.9 | 3.3 | 277.8 | 24.3 | 144.7 | 1233.7 | 73.1 | 80.3 |

| ±Sd | 0.72 | 124 | 73.25 | 0.33 | 6.41 | 0.104 | 0.57 | 30.28 | 4.73 | 5.78 | 111.68 | 25.06 | 7.74 | |

| S8 | Mean | 7.0 | 667.0 | 679.3 | 0.6 | 70.7 | 0.7 | 2.6 | 313.3 | 22.3 | 134.2 | 970.3 | 56.9 | 75.4 |

| ±Sd | 0.79 | 110.1 | 20.1 | 0.32 | 3.13 | 0.064 | 0.65 | 29.26 | 4.75 | 5.81 | 112.57 | 25.24 | 7.77 | |

| S9 | Mean | 7.1 | 621.8 | 632.3 | 0.5 | 71.2 | 0.6 | 2.7 | 328.8 | 17.0 | 125.8 | 1025.5 | 56.4 | 70.7 |

| ±Sd | 0.69 | 98.16 | 265.58 | 0.34 | 8.94 | 0.144 | 0.76 | 41.54 | 4.61 | 5.59 | 103.67 | 23.44 | 7.39 | |

| S10 | Mean | 7.0 | 604.5 | 680.2 | 0.6 | 73.5 | 0.5 | 2.6 | 327.5 | 16.1 | 102.9 | 1509.9 | 54.5 | 69.3 |

| ±Sd | 0.55 | 10.2 | 10.2 | 0.31 | 1.71 | 0.034 | 0.38 | 16.18 | 4.75 | 5.81 | 122.57 | 25.24 | 7.77 | |

| Zone 1 | Zone 2 | Zone 3 | Zone 4 | |||||||||||

| 2023 | PH | E.c µS/cm | TDS mg/l | Sal. % |

COD mg/l | PO4 mg/l | NO3 mg/l | SO4 mg/l | Cd µg/l |

Pb µg/l |

Zn µg/l |

Cr µg/l |

Ni µg/l |

|

| WHO std. | 6.5-8.5 | 1400 | 1000 | 1% | 100 | 0.4 | 50 | 250 | 5 | 10 | 5000 | 50 | 20 | |

| S1 | Mean | 7.36 | 336 | 233.5 | 0.213 | 11.5 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 62.5 | 2.065 | 12.9 | 292.5 | 17 | 15.5 |

| ±Sd | 0.39 | 89.60 | 39.60 | 0.04 | 5.66 | 0.10 | 0.95 | 52.33 | 1.04 | 2.20 | 89.00 | 3.00 | 3.80 | |

| S2 | Mean | 7.40 | 428 | 279.5 | 0.283 | 17.5 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 88.5 | 5.175 | 56.9 | 262.5 | 22 | 16.5 |

| ±Sd | 0.27 | 83.35 | 98.19 | 0.03 | 6.11 | 0.09 | 0.46 | 27.18 | 1.80 | 3.40 | 98.00 | 2.70 | 2.40 | |

| S3 | Mean | 6.96 | 542 | 357.0 | 0.492 | 23.0 | 0.4 | 1.9 | 95.5 | 6.025 | 89.4 | 344.5 | 39.5 | 31.5 |

| ±Sd | 0.47 | 106.71 | 72.95 | 0.03 | 6.11 | 0.09 | 0.46 | 27.18 | 2.02 | 3.81 | 134.88 | 3.02 | 2.69 | |

| S4 | Mean | 6.87 | 499 | 447.5 | 0.377 | 32.5 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 118.0 | 11.475 | 99.9 | 586.5 | 43.4 | 50.5 |

| ±Sd | 0.49 | 151.58 | 51.58 | 0.02 | 4.32 | 0.06 | 0.33 | 19.22 | 1.50 | 2.46 | 93.68 | 20.16 | 4.26 | |

| S5 | Mean | 6.86 | 590 | 583.0 | 0.545 | 53.0 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 229.0 | 18.925 | 108.9 | 1100.5 | 61.5 | 70 |

| ±Sd | 0.60 | 187.60 | 92.67 | 0.10 | 13.58 | 0.09 | 0.46 | 73.35 | 4.73 | 0.58 | 224.01 | 11.55 | 9.24 | |

| S6 | Mean | 6.82 | 602 | 600.0 | 0.428 | 50.0 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 296.5 | 17.825 | 120.55 | 961.5 | 66 | 63 |

| ±Sd | 0.70 | 172.95 | 19.70 | 0.03 | 6.11 | 0.09 | 0.46 | 27.18 | 1.77 | 2.90 | 117.48 | 23.76 | 5.02 | |

| S7 | Mean | 7.01 | 582 | 564.5 | 0.498 | 47.5 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 307 | 16.475 | 118.9 | 829 | 64.5 | 49 |

| ±Sd | 0.42 | 123.70 | 72.95 | 0.03 | 6.11 | 0.09 | 0.46 | 27.18 | 1.63 | 2.68 | 108.58 | 21.96 | 4.64 | |

| S8 | Mean | 7.05 | 582 | 521.5 | 0.377 | 41.0 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 243.0 | 14.075 | 91.9 | 656.5 | 53.5 | 49.5 |

| ±Sd | 0.49 | 109.80 | 19.80 | 0.02 | 2.83 | 0.05 | 0.54 | 26.16 | 1.65 | 2.71 | 109.47 | 22.14 | 4.67 | |

| S9 | Mean | 7.19 | 578 | 500.0 | 0.392 | 32.5 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 287.5 | 13.2 | 86.4 | 886.5 | 49 | 56 |

| ±Sd | 0.39 | 97.86 | 265.28 | 0.04 | 8.64 | 0.13 | 0.65 | 38.44 | 1.51 | 2.49 | 100.57 | 20.34 | 4.29 | |

| S10 | Mean | 7.09 | 562 | 533.0 | 0.435 | 29.5 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 306.5 | 11.325 | 66.3 | 1076.5 | 48.5 | 47 |

| ±Sd | 0.25 | 9.90 | 9.90 | 0.01 | 1.41 | 0.02 | 0.27 | 13.08 | 1.65 | 2.71 | 119.47 | 22.14 | 4.67 | |

| Zone 1 | Zone 2 | Zone 3 | Zone 4 | |||||||||||

| T test between S1(wet) & S2(dry) 2022 | T test between S3(wet) & S4(dry) 2023 | |||||||

| Parameters | T-test | *DF | P | **Status p<0.05 | T-test | *DF | **P | Status p<0.05 |

| pH | 1.745881 | 18 | 0.048938 | 1 | 1.447636 | 0.082456 | 18 | 0 |

| EC | 2.648184 | 18 | 0.008176 | 1 | 4.165857 | 0.00029 | 18 | 1 |

| TDS | 3.868649 | 18 | 0.000563 | 1 | 2.244035 | 0.018822 | 18 | 1 |

| Salinity% | 2.669917 | 18 | 0.007808 | 1 | 2.244035 | 0.018822 | 18 | 1 |

| COD | 2.586038 | 18 | 0.009319 | 1 | 2.502734 | 0.011091 | 18 | 1 |

| 1.826824 | 18 | 0.042179 | 1 | 1.878644 | 0.038294 | 18 | 1 | |

| 5.394127 | 18 | 1.99E-05 | 1 | 3.51537 | 0.001235 | 18 | 1 | |

| 1.813528 | 18 | 0.021327 | 1 | 1.312887 | 0.102857 | 18 | 0 | |

| Cd | 1.798236 | 18 | 0.021757 | 1 | 1.474367 | 0.078829 | 18 | 1 |

| Pb | 2.008098 | 18 | 0.029941 | 1 | 2.944581 | 0.004334 | 18 | 1 |

| Zn | 1.668797 | 18 | 0.025606 | 1 | 1.643754 | 0.05879 | 18 | 1 |

| Cr | 1.6898 | 18 | 0.054156 | 1 | 3.256256 | 0.002192 | 18 | 1 |

| Ni | 1.484068 | 18 | 0.077546 | 1 | 2.173495 | 0.021667 | 18 | 1 |

| Parameters | T | P | *DF | **Status value(P<0.05) |

| pH | -0.71769 | 0.238669 | 38 | 0 |

| E.C | 2.425631 | 0.01007 | 38 | 1 |

| TDS | 2.137765 | 0.019515 | 38 | 1 |

| Salinity % | 3.525425 | 0.000561 | 38 | 1 |

| COD | 4.382003 | 4.48E-05 | 38 | 1 |

| 1.723515 | 0.046462 | 38 | 1 | |

| 4.139127 | 9.32E-05 | 38 | 1 | |

| 1.783523 | 0.41245 | 38 | 0 | |

| Cd | 2.3375 | 0.01239 | 38 | 1 |

| Pb | 2.235142 | 0.015682 | 38 | 1 |

| Zn | 1.420289 | 0.081838 | 38 | 1 |

| Cr | 1.858237 | 0.035448 | 38 | 1 |

| Ni | 2.035252 | 0.024422 | 38 | 1 |

| Zone | Element | 2013 | 2022 | 2023 | Factor1 | Factor 2 |

| Zone 1 | Cd | 1 | 4.0 | 2.065 | 4.00 | 2.07 |

| Pb | 4 | 19.0 | 12.9 | 4.75 | 3.23 | |

| Zn | 469 | 258.4 | 292.5 | -1.45 | -1.38 | |

| Cr | ND | 22.2 | 17 | ND | ND | |

| Ni | ND | 21.7 | 15.5 | ND | ND | |

| Zone 3 | Cd | 4 | 25.0 | 17.7 | 6.25 | 4.44 |

| Pb | 27 | 165.1 | 116.1 | 6.14 | 4.32 | |

| Zn | 1339 | 1544.5 | 963.6 | 1.15 | -1.28 | |

| Cr | ND | 62.2 | 64 | ND | ND | |

| Ni | ND | 90.5 | 60.6 | ND | ND | |

| Zone 4 | Cd | 5 | 18.5 | 12.87 | 3.69 | 2.57 |

| Pb | 32.5 | 102.9 | 86.43 | 3.17 | 2.66 | |

| Zn | 1961 | 1509.9 | 873.17 | -1.23 | -1.55 | |

| Cr | ND | 54.5 | 50.33 | ND | ND | |

| Ni | ND | 69.3 | 50.83 | ND | ND |

| 2022 | 2023 | ||||||

| sites | value | class | suitability | sites | value | class | suitability |

| S1 | 83.97 | 4 | Good | S1 | 90.06 | 4 | Good |

| S2 | 74.40 | 3 | Fair | S2 | 82.65 | 4 | Good |

| S3 | 71.53 | 3 | Fair | S3 | 77.79 | 3 | Fair |

| S4 | 66.95 | 3 | Fair | S4 | 70.12 | 3 | Fair |

| S5 | 62.27 | 3 | Marginal | S5 | 65.31 | 3 | Fair |

| S6 | 61.60 | 2 | Marginal | S6 | 63.85 | 2 | Marginal |

| S7 | 62.27 | 3 | Marginal | S7 | 68.59 | 3 | Fair |

| S8 | 67.89 | 3 | Fair | S8 | 71.56 | 3 | Fair |

| S9 | 68.56 | 3 | Fair | S9 | 71.02 | 3 | Fair |

| S10 | 68.93 | 3 | Fair | S10 | 71.56 | 3 | Fair |

| Mean | 68.83 | 3 | Fair | Mean | 73.25 | 3 | Fair |

| Year | values | class | suitability |

| 2009 | 82.848 | 4 | Good |

| 2010 | 88.65 | 4 | Good |

| 2011 | 90.045 | 4 | Good |

| 2012 | 89.852 | 4 | Good |

| 2013 | 80.448 | 4 | Good |

| 2014 | 85.885 | 4 | Good |

| 2022 | 68.83639 | 3 | Fair |

| 2023 | 73.25168 | 3 | Fair |

| sites | Cd | Pb | Zn | Cr | Ni |

| S1 | 1.4 | 3.9 | 41.5 | 9.3 | 6.9 |

| S2 | 2.6 | 9.0 | 41.7 | 13.1 | 6.7 |

| S3 | 3.1 | 12.6 | 38.4 | 19.7 | 11.2 |

| S4 | 5.3 | 14.6 | 238.6 | 22.9 | 19.7 |

| S5 | 8.0 | 18.2 | 404.7 | 26.1 | 28.1 |

| S6 | 8.3 | 16.6 | 362.0 | 28.8 | 27.1 |

| S7 | 7.8 | 15.9 | 323.2 | 30.7 | 24.9 |

| S8 | 7.1 | 14.8 | 254.2 | 23.9 | 23.4 |

| S9 | 5.4 | 13.8 | 268.7 | 23.7 | 21.9 |

| S10 | 5.1 | 11.3 | 395.6 | 22.9 | 21.5 |

| sites | Cd | Pb | Zn | Cr | Ni |

| S1 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 76.6 | 7.1 | 5.0 |

| S2 | 1.7 | 6.3 | 68.8 | 9.2 | 5.3 |

| S3 | 1.9 | 9.8 | 90.3 | 16.6 | 10.1 |

| S4 | 3.7 | 11.0 | 153.7 | 18.2 | 15.7 |

| S5 | 6.1 | 12.0 | 288.3 | 25.8 | 21.7 |

| S6 | 5.7 | 13.3 | 251.9 | 27.7 | 19.5 |

| S7 | 5.3 | 13.1 | 217.2 | 27.1 | 15.2 |

| S8 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 172.0 | 22.5 | 15.3 |

| S9 | 5.0 | 9.2 | 295.3 | 21.2 | 19.2 |

| S10 | 5.2 | 8.2 | 382.0 | 22.1 | 18.4 |

| 2022 | 2023 | ||||

| sites | HPI | Classification | sites | HPI | Classification |

| S1 | 38 | good | S1 | 33 | good |

| S2 | 42 | good | S2 | 37 | good |

| S3 | 48 | good | S3 | 44 | good |

| S4 | 117 | unsuitable | S4 | 87 | very poor |

| S5 | 206 | unsuitable | S5 | 132 | unsuitable |

| S6 | 210 | unsuitable | S6 | 125 | unsuitable |

| S7 | 192 | unsuitable | S7 | 110 | unsuitable |

| S8 | 130 | unsuitable | S8 | 107 | unsuitable |

| S9 | 120 | unsuitable | S9 | 95 | unsuitable |

| S10 | 106 | unsuitable | S10 | 96 | unsuitable |

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | S9 | S10 | |

| Cd | 41.97 | 21.40 | 39.43 | 61.98 | 134.70 | 143.56 | 128.72 | 112.05 | 65.62 | 58.05 |

| Pb | 10.58 | 24.24 | 34.06 | 39.54 | 49.047 | 44.95 | 43.00 | 39.88 | 37.38 | 30.57 |

| Zn | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.080 | 0.07 | 0.070 | 0.071 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Cr | 1.01 | 1.42 | 2.130 | 2.47 | 2.824 | 3.110 | 3.32 | 2.58 | 2.56 | 2.47 |

| Ni | 4.68 | 4.50 | 7.563 | 13.33 | 18.94 | 18.324 | 16.82 | 15.78 | 14.80 | 14.51 |

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | S9 | S10 | |

| Cd | 33.19 | 16.30 | 28.96 | 48.15 | 82.55 | 73.04 | 61.37 | 67.64 | 55.11 | 49.43 |

| Pb | 5.92 | 16.91 | 26.56 | 29.68 | 32.36 | 35.82 | 35.33 | 27.31 | 24.74 | 22.13 |

| Zn | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Cr | 0.77 | 1.00 | 1.79 | 1.97 | 2.79 | 3.00 | 2.93 | 2.43 | 2.29 | 2.39 |

| Ni | 3.35 | 3.57 | 6.81 | 10.57 | 14.65 | 13.19 | 10.26 | 10.36 | 12.99 | 12.40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).