Submitted:

17 June 2025

Posted:

19 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Physicochemical and Microbiological Parameters

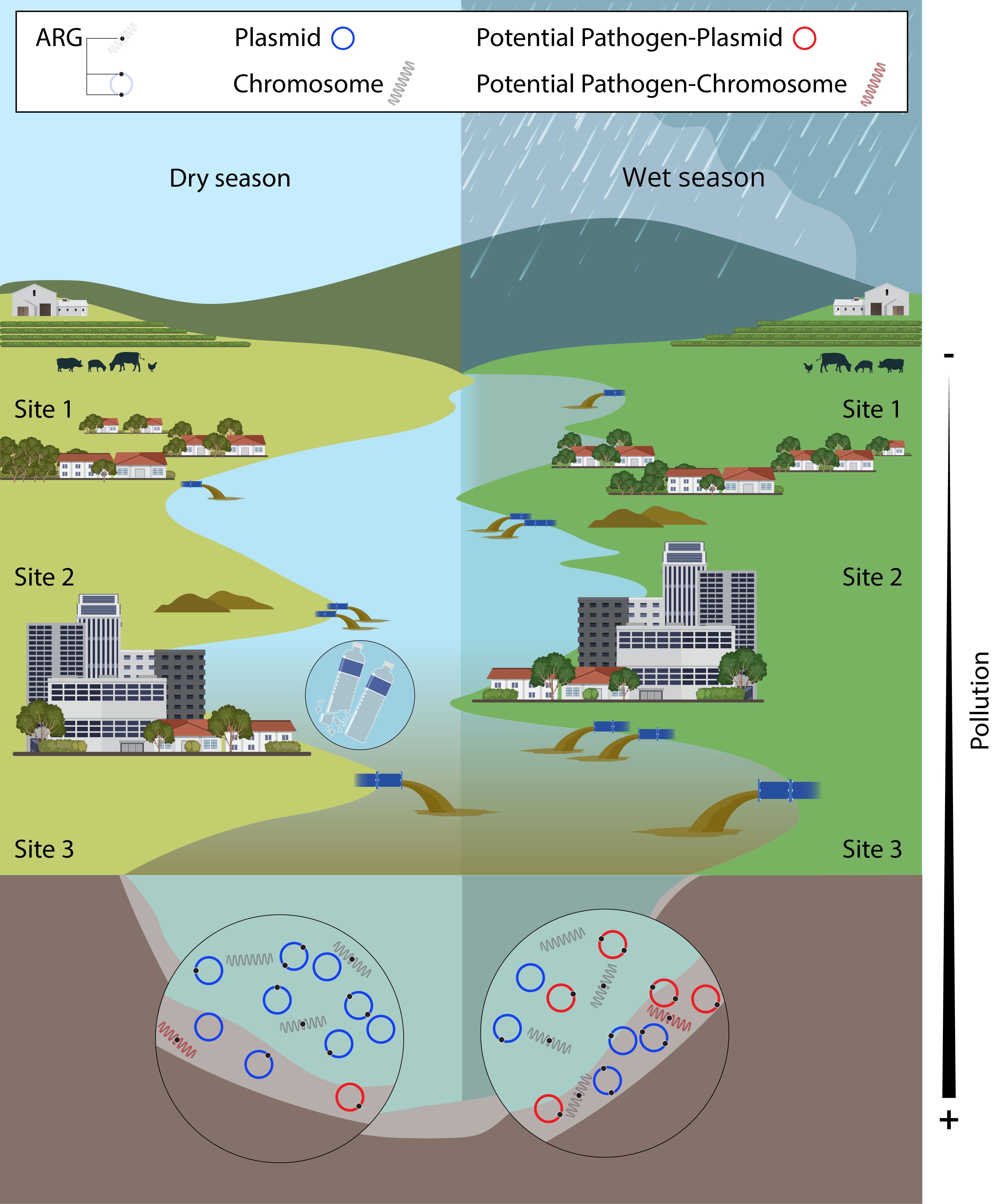

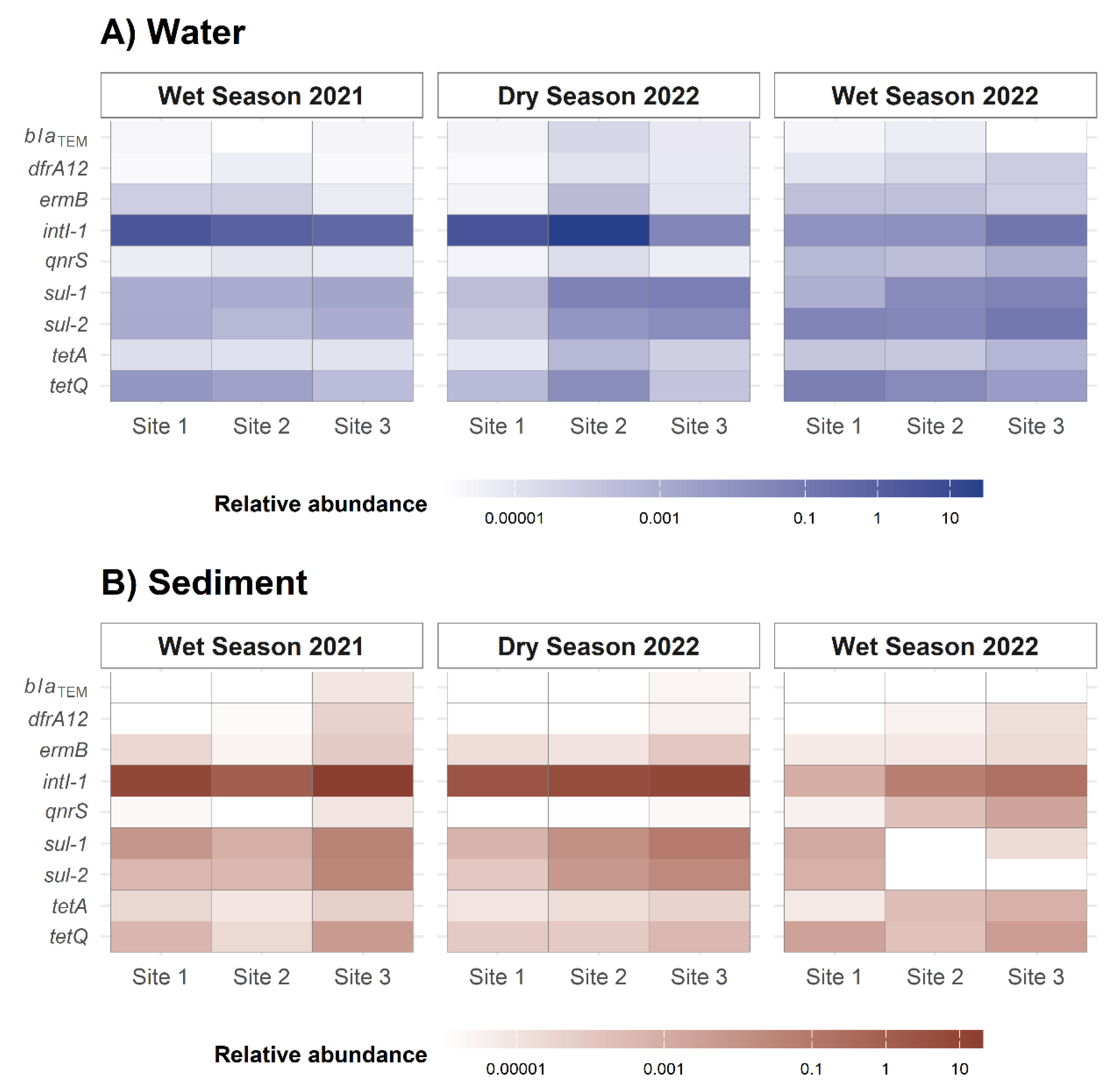

2.2. Seasonality Influences ARGs Distribution Along the Virilla River Watershed

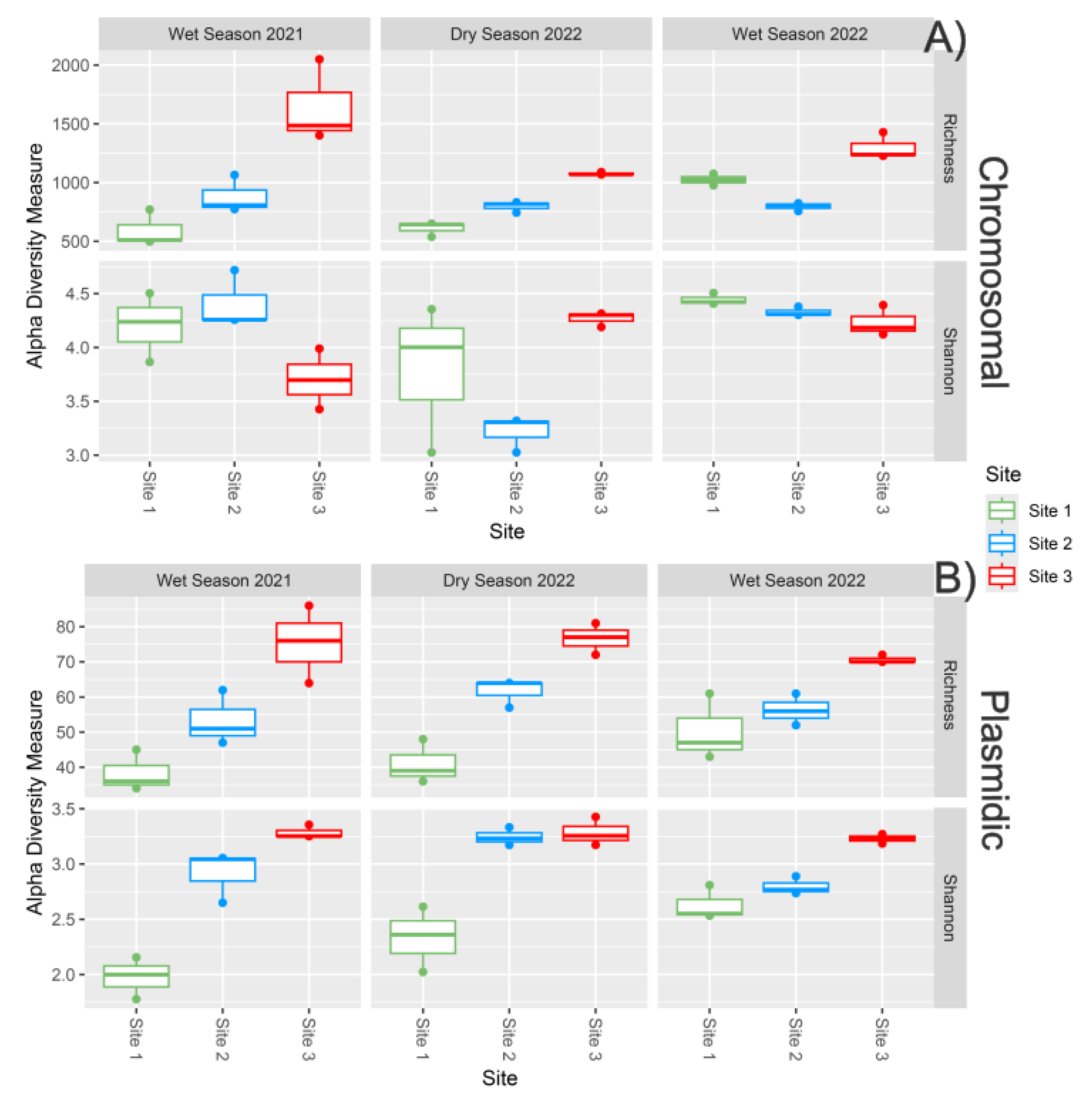

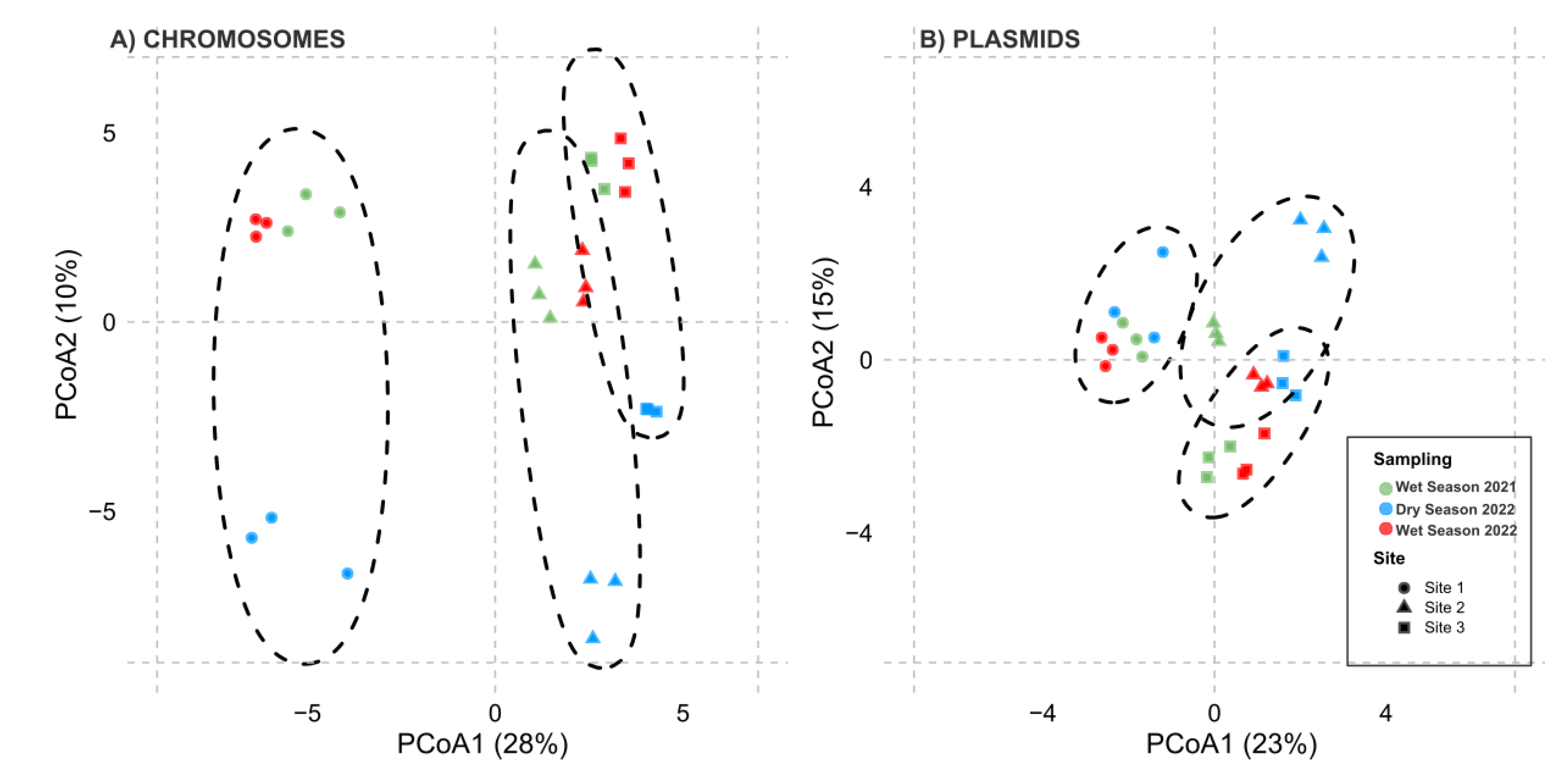

2.3. Bacteria Diversity Analysis

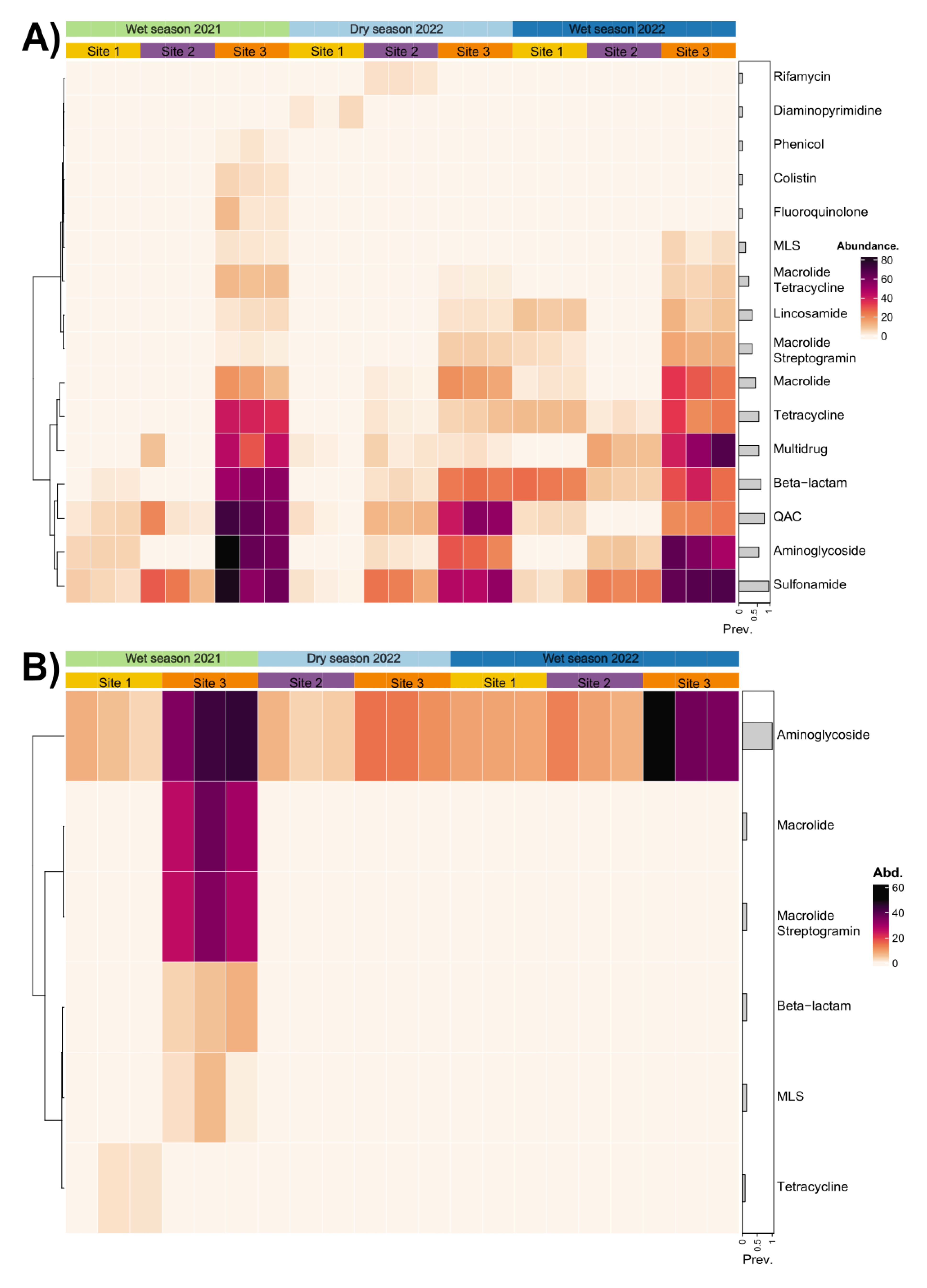

2.4. Abundance of Distinctive ARGs in Metagenomic Data

3. Discussion

3.1. Impacts of Pollution on the Surface Water of the Virilla River Watershed

3.2. Seasonal Dynamics of ARGs Quantification

3.3. Spatial Patterns Drive Microbial Community Composition and ARG Distribution More than Temporal Variability

4. Materials and Methods

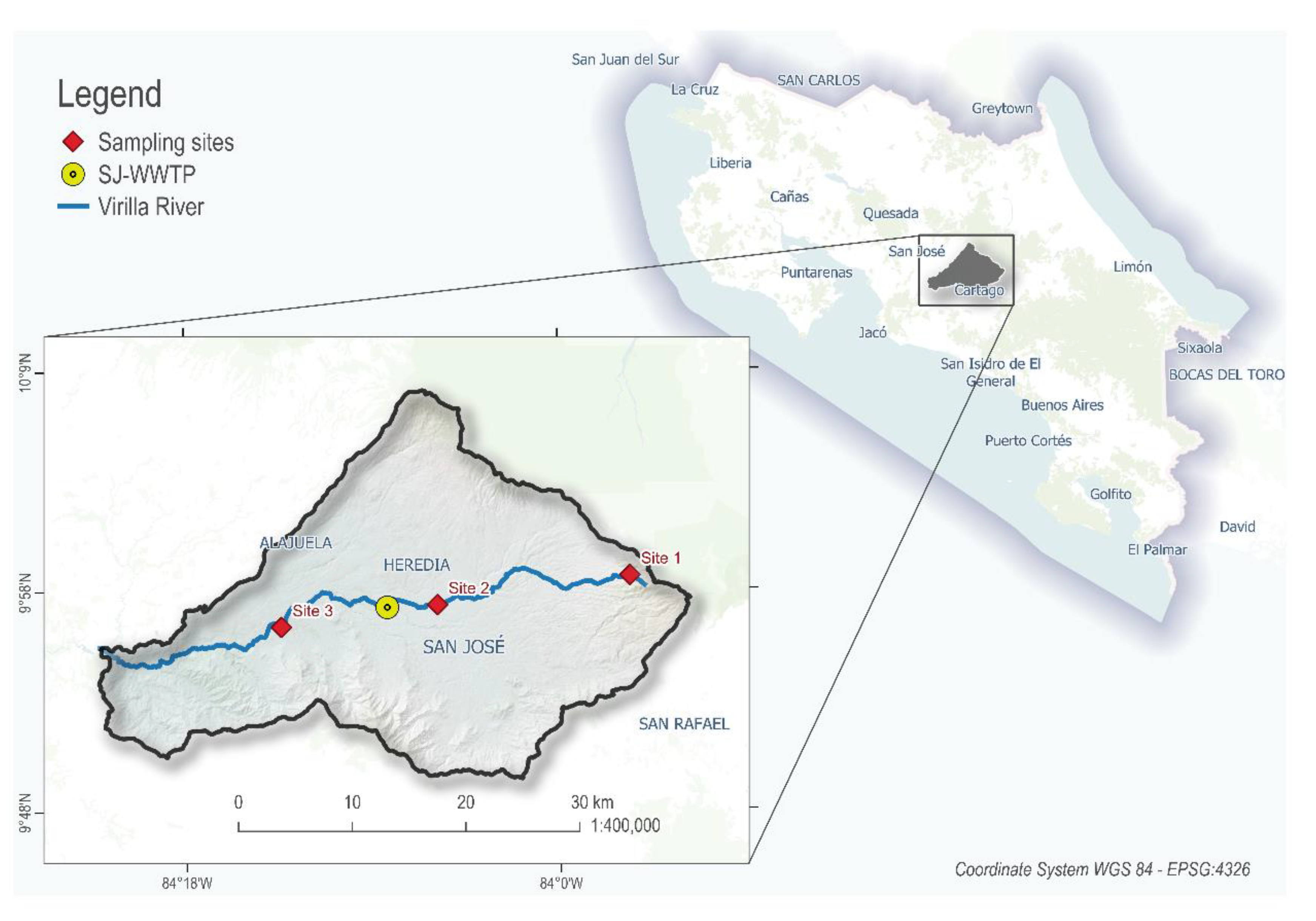

4.1. Study Area

4.2. Microbiological and Physical-Chemical Analysis

4.3. DNA Extraction and Quantification

4.4. Quantification of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes

4.5. Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing and Quality Control

4.6. Taxonomic Assignment and Diversity Analysis

4.7. Antibiotic Resistance Genes Detection from Sediment Samples

4.8. Precipitation Data

4.9. Data Analysis and Visualization

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D. Numberger et al., “Urbanization promotes specific bacteria in freshwater microbiomes including potential pathogens,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 845, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhu, R. Li, Y. Yan, and L. Cui, “Urbanization drives the succession of antibiotic resistome and microbiome in a river watershed,” Chemosphere, vol. 301, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Morales-Mora, L. Rivera-Montero, J. R. Montiel-Mora, K. Barrantes-Jiménez, and L. Chacón-Jiménez, “Assessing microbial risks of Escherichia coli: A spatial and temporal study of virulence and resistance genes in surface water in resource-limited regions,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 958, p. 178044, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang et al., “Antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements in different rivers: The link with antibiotics, microbial communities, and human activities,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 919, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Laperriere, R. H. Hilderbrand, S. R. Keller, R. Trott, and A. E. Santoro, “Headwater stream microbial diversity and function across agricultural and urban land use gradients,” Appl Environ Microbiol, vol. 86, no. 11, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Castañeda-Barba, E. M. Top, and T. Stalder, “Plasmids, a molecular cornerstone of antimicrobial resistance in the One Health era,” Jan. 01, 2024, Nature Research. [CrossRef]

- H. Huang et al., “Diverse and abundant antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in an urban water system,” J Environ Manage, vol. 231, pp. 494–503, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. A. Sabri et al., “Prevalence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in a wastewater effluent-receiving river in the Netherlands,” J Environ Chem Eng, vol. 8, no. 1, 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. M. Nolan et al., “Agricultural and urban practices are correlated to changes in the resistome of riverine systems,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 927, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. P. Marathe, C. Pal, S. S. Gaikwad, V. Jonsson, E. Kristiansson, and D. G. J. Larsson, “Untreated urban waste contaminates Indian river sediments with resistance genes to last resort antibiotics,” Water Res, vol. 124, pp. 388–397, 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Mendoza-Guido, K. Barrantes, C. Rodríguez, K. Rojas-Jimenez, and M. Arias-Andres, “The Impact of Urban Pollution on Plasmid-Mediated Resistance Acquisition in Enterobacteria from a Tropical River,” Antibiotics, vol. 13, no. 11, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. T. Botts et al., “Characterization of four multidrug resistance plasmids captured from the sediments of an urban coastal wetland,” Front Microbiol, vol. 8, no. OCT, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Di Cesare, E. M. Eckert, M. Rogora, and G. Corno, “Rainfall increases the abundance of antibiotic resistance genes within a riverine microbial community,” Environmental Pollution, vol. 226, pp. 473–478, 2017. [CrossRef]

- G. Reichert et al., “Determination of antibiotic resistance genes in a WWTP-impacted river in surface water, sediment, and biofilm: Influence of seasonality and water quality,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 768, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Zoppini, N. Ademollo, S. Amalfitano, P. Casella, L. Patrolecco, and S. Polesello, “Organic priority substances and microbial processes in river sediments subject to contrasting hydrological conditions,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 484, no. 1, pp. 74–83, Jun. 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. Pan, Y. Bao, and B. Xu, “Seasonal variation of antibiotics in surface water of Pudong New Area of Shanghai, China and the occurrence in typical wastewater sources,” Chemosphere, vol. 239, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Nessner Kavamura, R. G. Taketani, M. D. Lançoni, F. D. Andreote, R. Mendes, and I. Soares de Melo, “Water Regime Influences Bulk Soil and Rhizosphere of Cereus jamacaru Bacterial Communities in the Brazilian Caatinga Biome,” PLoS One, vol. 8, no. 9, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Arias-Andres, F. Mena, and M. Pinnock, “Ecotoxicological evaluation of aquaculture and agriculture sediments with biochemical biomarkers and bioassays: Antimicrobial potential exposure,” J Environ Biol, vol. 35, no. January, pp. 107–117, 2014.

- M. J. Fernandes et al., “Antibiotics and antidepressants occurrence in surface waters and sediments collected in the north of Portugal,” Chemosphere, vol. 239, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Yitayew et al., “Antimicrobial resistance genes in microbiota associated with sediments and water from the Akaki river in Ethiopia,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 29, no. 46, pp. 70040–70055, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Heim and J. Schwarzbauer, “Pollution history revealed by sedimentary records: A review,” Environ Chem Lett, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 255–270, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Z. Maghsodian et al., “Occurrence and Distribution of Antibiotics in the Water, Sediment, and Biota of Freshwater and Marine Environments: A Review,” Nov. 01, 2022, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang et al., “Pollution gradients shape the co-occurrence networks and interactions of sedimentary bacterial communities in Taihu Lake, a shallow eutrophic lake,” J Environ Manage, vol. 305, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Rodríguez-Beltrán, J. DelaFuente, R. León-Sampedro, R. C. MacLean, and Á. San Millán, “Beyond horizontal gene transfer: the role of plasmids in bacterial evolution,” Jun. 01, 2021, Nature Research. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Partridge, S. M. Kwong, N. Firth, and S. O. Jensen, “Mobile Genetic Elements Associated with Antimicrobial Resistance,” Clin Microbiol Rev, vol. 31, no. 4, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Kothari et al., “Large circular plasmids from groundwater plasmidomes span multiple incompatibility groups and are enriched in multimetal resistance genes,” mBio, vol. 10, no. 1, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Stockdale et al., “Metagenomic assembled plasmids of the human microbiome vary across disease cohorts,” Sci Rep, vol. 12, no. 1, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- SINIGIRH, “Sistema Nacional de Información Para La Gestión Integrada Del Recurso Hídrico.,” https://mapas.da.go.cr/mapnew.php. [Online]. Available: http://mapas.da.go.cr/.

- K. Barrantes-Jiménez et al., “Anthropogenic imprint on riverine plasmidome diversity and proliferation of antibiotic resistance genes following pollution and urbanization,” Water Res, vol. 281, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO, “Partnerships and cooperation for water The United Nations World Water Development Report 2023,” Paris, 2023. [Online]. Available: www.unwater.org.

- J. Herrera-Murillo, D. Anchía-Leitón, J. F. Rojas-Marín, D. Mora-Campos, A. Gamboa-Jiménez, and M. Chaves-Villalobos, “Influencia de los patrones de uso de la tierra en la calidad de las aguas superfciales de la subcuenca del río Virilla, Costa Rica,” Revista Geográfica de América Central, vol. 4, no. 61E, p. 11, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Mena-Rivera, O. Vásquez-Bolaños, C. Gómez-Castro, A. Fonseca-Sánchez, A. Rodríguez-Rodríguez, and R. Sánchez-Gutiérrez, “Ecosystemic assessment of surface water quality in the Virilla River: Towards sanitation processes in Costa Rica,” Water (Switzerland), vol. 10, no. 7, pp. 1–16, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), “Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Technical Summary,” Cambridge University Press, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Adyari et al., “Seasonal hydrological dynamics govern lifestyle preference of aquatic antibiotic resistome,” Environmental Science and Ecotechnology, vol. 13, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Jiang et al., “Antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements in a rural river in Southeast China: Occurrence, seasonal variation and association with the antibiotics,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 778, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Bengtsson-Palme, E. Kristiansson, and D. G. J. Larsson, “Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance,” FEMS Microbiol Rev, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 68–80, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Amarasiri, D. Sano, and S. Suzuki, “Understanding human health risks caused by antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB) and antibiotic resistance genes (ARG) in water environments: Current knowledge and questions to be answered,” Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol, vol. 50, no. 19, pp. 2016–2059, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. P. Neher, L. Ma, T. B. Moorman, A. Howe, and M. L. Soupir, “Seasonal variations in export of antibiotic resistance genes and bacteria in runoff from an agricultural watershed in Iowa,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 738, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Zalewska, A. Błażejewska, A. Czapko, and M. Popowska, “Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Animal Manure – Consequences of Its Application in Agriculture,” Mar. 29, 2021, Frontiers Media S.A. [CrossRef]

- S. Suhartono, M. Savin, and E. E. Gbur, “Genetic redundancy and persistence of plasmid-mediated trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole resistant effluent and stream water Escherichia coli,” Water Res, vol. 103, pp. 197–204, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. H. Le et al., “Occurrences and characterization of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and genetic determinants of hospital wastewater in a tropical country,” Antimicrob Agents Chemother, vol. 60, no. 12, pp. 7449–7456, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Díaz-Madriz et al., “Assessing antimicrobial consumption in public and private sectors within the Costa Rican health system: current status and future directions,” BMC Public Health, vol. 24, no. 1, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Blanco-Meneses, O. Castro-Zúñiga, and A. Calderón-Abarca, “Diagnóstico del uso de antibióticos en regiones productoras de tomate en Costa Rica,” Agronomía Costarricense, vol. 1, no. 47, pp. 87–99, 2023, Accessed: Mar. 10, 2025. [Online]. Available: www.mag.go.cr/rev_agr/index.html.

- E. D. La Cruz, F. Garcia, and A. Molina, “Hazard prioritization and risk characterization of antibiotics in an irrigated Costa Rican region used for intensive crop, livestock and aquaculture farming,” J Environ Biol, vol. 35, no. Special issue, pp. 85–98, 2014.

- F. Granados-Chinchilla and C. Rodríguez, “Tetracyclines in Food and Feedingstuffs: From Regulation to Analytical Methods, Bacterial Resistance, and Environmental and Health Implications,” 2017, Hindawi Limited. [CrossRef]

- Costa Rica Gobierno del Bicentenario, “Plan de acción nacional de lucha contra la Resistencia a los antimicrobianos Costa Rica 2018-2025,” 2018. Accessed: Mar. 03, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ministeriodesalud.go.cr/index.php/biblioteca-de-archivos-left/documentos-ministerio-de-salud/vigilancia-de-la-salud/normas-protocolos-guias-y-lineamientos/resistencia-a-los-antimicrobianos/1861-plan-de-accion-nacional-de-lucha-contra-la-resistencia-a-los-antimicrobianos-costa-rica-2018-2025/file.

- A. Li et al., “Occurrence and distribution of antibiotic resistance genes in the sediments of drinking water sources, urban rivers, and coastal areas in Zhuhai, China,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 25, no. 26, pp. 26209–26217, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang, G. Yang, Y. Zhang, and C. Yang, “High-throughput profiling of antibiotic resistance genes in the Yellow River of Henan Province, China,” Sci Rep, vol. 14, no. 1, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Haenelt, H. H. Richnow, J. A. Müller, and N. Musat, “Antibiotic resistance indicator genes in biofilm and planktonic microbial communities after wastewater discharge,” Front Microbiol, vol. 14, 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Strugeon, V. Tilloy, M. C. Ploy, and S. Da Re, “The stringent response promotes antibiotic resistance dissemination by regulating integron integrase expression in biofilms,” mBio, vol. 7, no. 4, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. Philippot, B. S. Griffiths, and S. Langenheder, “Microbial Community Resilience across Ecosystems and Multiple Disturbances,” Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, vol. 85, no. 2, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Liu, P. Wang, C. Wang, X. Wang, and J. Chen, “Anthropogenic disturbances on antibiotic resistome along the Yarlung Tsangpo River on the Tibetan Plateau: Ecological dissemination mechanisms of antibiotic resistance genes to bacterial pathogens,” Water Res, vol. 202, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. Lekunberri, J. L. Balcázar, and C. M. Borrego, “Metagenomic exploration reveals a marked change in the river resistome and mobilome after treated wastewater discharges,” Environmental Pollution, vol. 234, pp. 538–542, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Kämpfer, “Acinetobacter,” in Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology: Second Edition, Elsevier Inc., 2014, pp. 11–17. [CrossRef]

- K. Towner, “The Genus Acinetobacter,” pp. 746–758, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Y. Dai, J. Gao, and M. Jiang, “Case Report: A rare infection of multidrug-resistant Aeromonas caviae in a pediatric case with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and review of the literature,” Front Pediatr, vol. 12, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Mayslich, P. A. Grange, N. Dupin, and H. Brüggemann, “microorganisms Cutibacterium acnes as an Opportunistic Pathogen: An Update of Its Virulence-Associated Factors,” 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Nakamura et al., “Epidemiology of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella Species, and Proteus mirabilis strains producing extended-spectrum -βlactamases from clinical samples in the Kinki region of Japan,” Am J Clin Pathol, vol. 137, no. 4, pp. 620–626, Apr. 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. Zayet et al., “Leclercia adecarboxylata as emerging pathogen in human infections: Clinical features and antimicrobial susceptibility testing,” Pathogens, vol. 10, no. 11, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Chorost et al., “Bacteraemia due to Microbacterium paraoxydans in a patient with chronic kidney disease, refractory hypertension and sarcoidosis,” JMM Case Rep, vol. 5, no. 11, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Yao and D. Liu, “Moraxella catarrhalis,” in Molecular Medical Microbiology, Third Edition, Elsevier, 2023, pp. 1503–1517. [CrossRef]

- O. M. Alzahrani et al., “Pseudomonas putida: Sensitivity to Various Antibiotics, Genetic Diversity, Virulence, and Role of Formic Acid to Modulate the Immune-Antioxidant Status of the Challenged Nile tilapia Compared to Carvacrol Oil,” Fishes, vol. 8, no. 1, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Niu, B. Wang, Z. Wang, and H. Zhang, “Effect of pH on antibiotic resistance genes removal and bacterial nucleotides metabolism function in the wastewater by the combined ferrate and sulfite treatment,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 480, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Q. Yu et al., “Metagenomics reveals the response of antibiotic resistance genes to elevated temperature in the Yellow River,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 859, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Huang, W. Zhao, T. Xu, B. Zheng, and D. Yin, “Occurrence and distribution of antibiotic resistance genes in the water and sediments of Qingcaosha Reservoir, Shanghai, China,” Environ Sci Eur, vol. 31, no. 1, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Mora-Aparicio, C. Alfaro-Chinchilla, J. P. Pérez-Molina, and I. Vega-Guzmán, “Environmental contribution of Los Tajos wastewater treatment plant in the removal of physicochemical and microbiological pollutants,” Uniciencia, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 1–17, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Brown, N. I. McClelland, R. A. Deininger, and M. F. O’Connor, “A water quality index-crashing the psychological barrier,” 1972.

- M. Marselina, F. Wibowo, and A. Mushfiroh, “Water quality index assessment methods for surface water: A case study of the Citarum River in Indonesia,” Heliyon, vol. 8, no. 7, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Srivastava and P. Kumar, “Water Quality Index with Missing Parameters,” IJRET: International Journal of Research in Engineering and Technology, vol. 2, no. 4, Apr. 2013, [Online]. Available: http://www.ijret.org.

- I. Ichwana, S. Syahrul, and W. Nelly, “Water Quality Index by Using National Sanitation Foundation-Water Quality Index (NSF-WQI) Method at Krueng Tamiang Aceh,” in Proceeding of the First International Conference on Technology, Innovation and Society, ITP Press, Jul. 2016, pp. 110–117. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Uddin, S. Nash, and A. I. Olbert, “A review of water quality index models and their use for assessing surface water quality,” Mar. 01, 2021, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- S. Chen, Y. Zhou, Y. Chen, and J. Gu, “Fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor,” in Bioinformatics, Oxford University Press, Sep. 2018, pp. i884–i890. [CrossRef]

- B. Langmead and S. L. Salzberg, “Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2,” Nat Methods, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 357–359, Apr. 2012. [CrossRef]

- D. E. Wood, J. Lu, and B. Langmead, “Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2,” Genome Biol, vol. 20, no. 1, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Chaumeil, A. J. Mussig, P. Hugenholtz, and D. H. Parks, “GTDB-Tk: A toolkit to classify genomes with the genome taxonomy database,” Bioinformatics, vol. 36, no. 6, pp. 1925–1927, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Lu, F. P. Breitwieser, P. Thielen, and S. L. Salzberg, “Bracken: Estimating species abundance in metagenomics data,” PeerJ Comput Sci, vol. 2017, no. 1, 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. J. McMurdie and S. Holmes, “Shiny-phyloseq: Web application for interactive microbiome analysis with provenance tracking,” Bioinformatics, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 282–283, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Bartlett, D. Padfield, L. Lear, R. Bendall, and M. Vos, “A comprehensive list of bacterial pathogens infecting humans,” Microbiology (United Kingdom), vol. 168, no. 12, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Li, C. M. Liu, R. Luo, K. Sadakane, and T. W. Lam, “MEGAHIT: An ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph,” Bioinformatics, vol. 31, no. 10, pp. 1674–1676, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Mikheenko, V. Saveliev, and A. Gurevich, “MetaQUAST: Evaluation of metagenome assemblies,” Bioinformatics, vol. 32, no. 7, pp. 1088–1090, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Yu, E. C. Fogarty, and A. M. Eren, “Diverse plasmid systems and their ecology across human gut metagenomes revealed by PlasX and MobMess,” Nat Microbiol, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 830–847, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Eren et al., “Community-led, integrated, reproducible multi-omics with anvi’o,” Jan. 01, 2021, Nature Research. [CrossRef]

- D. Hyatt, G.-L. Chen, P. F. Locascio, M. L. Land, F. W. Larimer, and L. J. Hauser, “Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification,” 2010. [Online]. Available: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2105/11/119.

- M. Y. Galperin et al., “COG database update 2024,” Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 53, no. D1, pp. D356–D363, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Mistry et al., “Pfam: The protein families database in 2021,” Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 49, no. D1, pp. D412–D419, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Jia et al., “CARD 2017: Expansion and model-centric curation of the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database,” Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 45, no. D1, pp. D566–D573, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Li et al., “The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools,” Bioinformatics, vol. 25, no. 16, pp. 2078–2079, Aug. 2009. [CrossRef]

- A. Bairoch and R. Apweiler, “The SWISS-PROT protein sequence database and its supplement TrEMBL in 2000,” 2000. [Online]. Available: http://www.expasy.

- W. Wang and M. E. Griswold, “Natural interpretations in Tobit regression models using marginal estimation methods,” Stat Methods Med Res, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 2622–2632, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. G. Halsey, “The reign of the p-value is over: What alternative analyses could we employ to fill the power vacuum?,” May 01, 2019, Royal Society Publishing. [CrossRef]

| Sampling sites | Fecal coliforms (mean ± standard deviation) MPN/100 ml |

E.coli (mean ± standard deviation) MPN/100 ml | E.faecalis (mean ± standard deviation) MPN/100 ml | O2 sat % (mean ± standard deviation) |

Temperature (mean ± standard deviation) °C |

pH (mean ± standard deviation | Turbidity (mean ± standard deviation) UNT | NSFQI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling campaign 1 (wet season 2021) | ||||||||

| Site 1 | (4.33 ± 7.76) × 10^4 | (2.99 ± 4.34) × 10^4 | (3.12 ± 1.90) × 10^4 | 71.4 ± 3.7 | 18.7 ± 3.2 | 7.94 ± 2.30e-01 | 142.0 ± 95.4 | 44 |

| Site 2 | (6.79 ± 10.50) × 10^4 | (6.79 ± 10.50) × 10^4 | (1.10 ± 1.65) × 10^5 | 61.1 ± 33.0 | 19.5 ± 3.5 | 7.90 ± 2.23e-01 | 33.0 ± 9.3 | 41 |

| Site 3 | (1.48 ± 1.49) × 10^5 | (1.35 ± 1.54) × 10^5 | (1.92 ± 12.30) × 10^4 | 51.9 ± 6.4 | 19.2 ± 3.4 | 7.93 ± 9.50e-02 | 13.1 ± 15.1 | 28 |

| Sampling campaign 2 (dry season 2022) | ||||||||

| Site 1 | (2.88 ± 0.64) × 10^2 | (2.11 ± 1.00) × 10^2 | (6.67 ± 3.29) × 10^2 | 78.1 ± 0.0 | 15.8 ± 0.0 | 7.51 ± 1.09e-15 | 9.8 ± 0.0 | 66 |

| Site 2 | (9.64 ± 7.22) × 10^4 | (6.71 ± 6.74) × 10^4 | (1.87 ± 0.44) × 10^4 | 71.8 ± 0.0 | 23.4 ± 0.0 | 7.85 ± 1.09e-15 | 8.7 ± 0.0 | 49 |

| Site 3 | (3.38 ± 1.10) × 10^5 | (2.59 ± 1.00) × 10^5 | (5.58 ± 2.90) × 10^3 | 47.7 ± 0.0 | 28.0 ± 0.0 | 7.90 ± 1.09e-15 | 21.9 ± 0.3 | 35 |

| Sampling campaign 3 (wet season 2022) | ||||||||

| Site 1 | (4.60 ± 0.00) × 10^3 | (4.60 ± 0.00) × 10^3 | (3.50 ± 0.00) × 10^3 | 86.2 ± 0.0 | 15.9 ± 0.0 | 7.72 ± 0.00e+00 | 38.0 ± 3.0 | 49 |

| Site 2 | (9.20 ± 0.00) × 10^4 | (5.40 ± 0.00) × 10^4 | (3.50 ± 0.00) × 10^4 | 80.0 ± 0.0 | 20.7 ± 0.0 | 8.10 ± 0.00e+00 | 167.0 ± 2.0 | 41 |

| Site 3 | (7.00 ± 0.00) × 10^4 | (3.10 ± 0.00) × 10^4 | (9.20 ± 0.00) × 10^3 | 77.0 ± 0.0 | 25.6 ± 0.0 | 7.76 ± 1.09e-15 | 215.0 ± 5.0 | 42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).