Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Pollution of aquatic ecosystems is rising due to anthropogenic activities, with developing countries facing severe water contamination due to inadequate wastewater treatment, and limited access to clean water. This study investigates water microbial contamination in the Nandoni Dam, Thate Vondo Dam, Albasini Dam, the Xikundu Weir (Limpopo province), and the Orlando Dam (Gauteng province) in South Africa. Water quality was determined using possible human activities, physical parameters, and pathogenic indicators (Total coliforms (TC) and Escherichia coli (E. coli). TC and E. coli were detected using the Quanti-Tray®, and E. coli was characterized using multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction (mPCR). The Vitek-2 automated system was used for isolate identification. The Electrical conductivity (EC) at all sites met South African water quality guidelines of DWAF and WHO, while other physical parameters (TDS, pH, and temperature) varied across the sites. TC levels exceeded the recommended limits and 85% of samples tested positive for E. coli. Five pathogenic E. coli were identified: Enterohaemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), Enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC), and Enterotoxigenic E. coli. Nandoni Dam and Orlando Dam showed a high diversity of bacterial species. Overall, the microbial quality of the assessed water was substandard.

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Study Area

Sample Collection

Physical Parameters Measurements

Risk Assessment Analysis

Enumeration of Escherichia coli and Determination of Total Coliform

Membrane Filtration Analysis

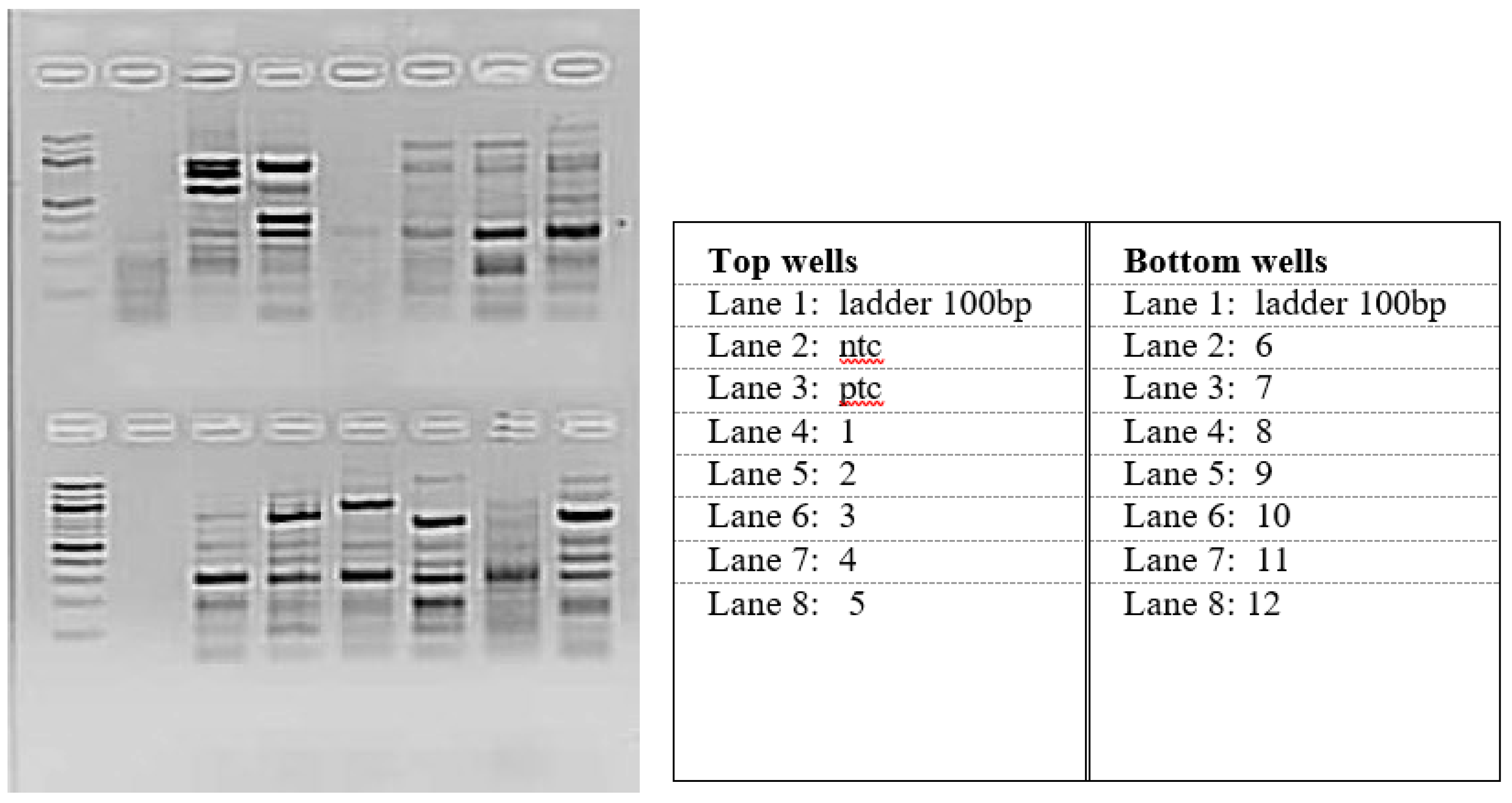

Multiplex PCR (mPCR)

Specificity of the m-PCR

Identification of Isolates Using Vitek 2 Automated System

Statistical Analysis

Results

Physical Parameters

Comparison Between the Nandoni Dam and the Orlando Dam

Risk Assessment

| Assessed human activities | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling site | Garbage point | Animal grazing | Bricklaying | Farming | Body wash | Faecal matter | Industrial waste | Fishing | Sewage discharge | % of Risk per site |

| Nandoni dam 1 | + | + | + | - | ⁻ | + | + | + | + | 77.8 |

| Nandoni dam 2 | + | + | + | - | - | + | ⁻ | + | + | 66.7 |

| Nandoni dam 3 | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | 88.9 |

| Orlando dam 1 | + | ⁻ | ⁻ | ⁻ | ⁻ | ⁻ | + | ⁻ | + | 33.3 |

| Orlando dam 2 | ⁻ | ⁻ | ⁻ | ⁻ | ⁻ | ⁻ | + | ⁻ | + | 22.2 |

| Orlando dam 3 | + | ⁻ | ⁻ | ⁻ | ⁻ | ⁻ | ⁻ | + | 22.2 | |

| Orlando dam 4 | + | ⁻ | ⁻ | ⁻ | ⁻ | ⁻ | ⁻ | ⁻ | + | 22.2 |

| Thate Vondo 1 | + | + | - | - | - | + | ⁻ | - | ⁻ | 33.3 |

| Thate Vondo 2 | - | - | - | - | - | + | ⁻ | - | ⁻ | 11.1 |

| Thate Vondo 3 | + | - | - | - | - | - | ⁻ | - | ⁻ | 11.1 |

| Albasini dam 1 | + | ⁻ | ⁻ | + | ⁻ | + | ⁻ | ⁻ | ⁻ | 33.3 |

| Albasini dam 2 | + | ⁻ | ⁻ | + | ⁻ | + | ⁻ | ⁻ | ⁻ | 33.3 |

| Xikundu weir | - | + | - | + | + | + | ⁻ | - | ⁻ | 44.4 |

| Percentage per risk activity | 76.9 | 38.5 | 23.1 | 23.1 | 15.4 | 61.5 | 30.8 | 23.1 | 53.8 | |

| += Activity observed; ⁻ = No activity observed | ||||||||||

The E. coli Strains Were Identified in Water Samples

Bacterial Isolates Identified by the Vitek-2 Automated System

Discussion

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Appendix A. Compounds used to perform 43 biochemical tests.

References

- Nthunya, L.N; Khumalo, N.P; Verliefde, A.R; Mamba, B.B; Mhlanga, S.D. Quantitative analysis of phenols and pahs in the Nandoni dam in Limpopo Province, South Africa: A preliminary study for dam water quality management Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, pp. 228-238, 2019.

- Potgieter, N; Karambwe, S; Mudau, L.S; Barnard, T; Traoré, A. Human enteric pathogens in eight rivers used as rural household drinking water sources in the northern region of South Africa. International Journal O of Environmental Research and Public, 17(6), p. 2079, 2020.

- Onyango, A.E; Okoth, M.W; Kunyanga, C.N; Aliwa, B.O. Microbiological quality and contamination level of water sources in Isiolo County in Kenya. Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ashbolt, N.J. Microbial contamination of drinking water and human health from community water systems. Current Environmental Health Reports, 2(1), pp. 95-106, 2015.

- Sankhla, M. S; Kumari, M; Nandan, M; Kumar, R; Agrawal, P. Heavy metals contamination in water and their hazardous effect on human health-a review. International Journal of Currents Mcrobiology and Applied Science, 5(10), pp. 759-766, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Shafy, H.I; Mansour, M.S. A review on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: source, environmental impact, effect on human health and remediation. Egyptian journal of Petroleum, 25(1), pp. 107-123, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Praveen, P. K; Ganguly, S, Wakchaure, R, Para, P.A, Mahajan, T, Qandri, K, Kamble, S, Sharma, R, Shekhar, S, Eds.; Dalai, N. Water-borne diseases and its effect on domestic animals and human health: A Review. International Journal of Advanced Research and Technology, pp. 242-245, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gumbo, J.R; Dzaga, R.A; Nethengwe, N.S. Impact on water quality of Nandoni water reservoir downstream of municipal sewage plants in Vhembe District, South Africa. Sustainability, 8(7), p. 597, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cissé, G. Food-borne and water-borne disease under climate change in low-and middle-income countries: Further efforts needed for reducing environmental health exposure risks. Acta Tropica, 194, pp. 181-188, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Potgieter, N; Becker, P.J; Ehlers, M.M. Evaluation of the CDC safe water-storage intervention to improve the microbiological quality of point-of-use drinking water in rural communities in South Africa. Water SA, 2009.

- Barnhoorn, I.E.J; Bornman, M.S; Van Rensburg, C.J; Bouwman, H. DDT residues in water, sediment, domestic, and indigenous biota from a currently DDT-sprayed area. Chemosphere, 77(9), pp. 1236-1241, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Obi, C. L; Potgieter, N; Bessong, P.O. Enteric Pathogens in Water Sources and Stools of Residents in the Venda Region of Limpopo Province. Water Research Commission, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Edokpayi, J.N; Odiyo, J.O; Durowoju, O.S. Impact of wastewater on surface water quality in developing countries: a case study of South Africa. Water Quality, pp. 401-416, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Edokpayi, J.N; Enittan, A. M; Mutileni, N; Odiyo, J.O. Evaluation of water quality and human risk assessment due to heavy metals in groundwater around Muledane area of Vhembe District, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Chemistry Central Journal, 2018; 2. [Google Scholar]

- Musetha, M.A. The impact of climate change on agricultural crop production in the Vhembe District Municipality, Limpopo Province South Africa (Doctoral dissertation). Doctoral dissertation, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nefale, T.A. The role of agricultural cooperatives in poverty reduction: A case study of selected cooperatives in the four local municipalities of Vhembe district municipality, Limpopo Province, South Africa (Doctoral dissertation). Doctoral dissertation, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vhembe District Municipality. Annual performance report 2021/2022. Final VDM annual performance report 2021-2022 financial year 31 august 202215h30," thohoyandou, 2022.

- Traoré, A. N; Mulaudzi, K; Chari, G.J; Foord, S.H; Mudau, L.S; Barnard, T.G; Potgieter, N. The impact of human activities on microbial quality of rivers in the Vhembe District, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(8), p. 817, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sibada, T; Okoh, A.I. Real-time PCR quantitative assessment of hepatitis A virus, rotaviruses, and enteroviruses in the Tyume River located in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Water SA, 2013.

- Bengu, T. S; Du Plessis, J; Modley, L.S van Dyk, J.C. Health effects in fish from the polluted Orlando Dam and Klipspruit wetland system, Soweto, South Africa. African Journal of Aquatic Science, 42(2), pp. 131-141. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pheiffer, W; Bortey-Sam, N; Ikenaka, Y; Nakayama, S.M.M; Mizukawa, H; Ishinuka, M; Smith, N.J; Pieters, R. First report on OH-PAHs in South African Clarias gariepinus bile from an urban impacted system. African Journal of Aquatic Science, 43(3), pp. 305-312, 2018.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for drinking-water quality: second addendum. Vol. 1, Recommendations, 3rd ed. World Health Organization, 2008.

- World Health Organization. Assessing microbial safety of drinking water improving approaches and methods: Improving approaches and methods. OECD Publishing, 2003.

- World Health Organization. A toolkit for monitoring and evaluating household water treatment and safe storage programmes, 2012.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Water Quality. Health Criteria and Other Supporting Information. World Health Organization, Geneva, 1993.

- Omar, K.B; Barnard, T.G. Detection of diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli in clinical and environmental water sources in South Africa using single-step 11-gene m-PCR. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 30(10), pp. 2663-2671, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Banu, O.K; George, B.T; Paul, J. Development of a competitive PCR assay for the quantification of total Escherichia coli DNA in water. African Journal of Biotechnology, 9(4), 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Water Affairs and Forestry. South African Water Guidelines. Domestic Water Use, 1996.

- Department of Water Affairs and Forestry. South African Water Guidelines. Aquatic ecosystems, 1996.

- Odiyo, J. O; Chimuka, L; Mamali, M.A; Fatoki, O.S. Trophic status of Vondo and Albasini Dams; impacts on aquatic ecosystems and drinking water. International Journal of Science and Technology, 9,(2), pp. 203-218, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sinthumule, N.I. Window of economic opportunity or door of exclusion? Nandoni Dam and its local communities. Sustainability, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Water quality and health: Review of the health effects of chemicals on the quality of drinking-water. Geneva, WHO Press, 2017.

- Barnhoorn. I.E.J. Intersex in feral indigenous freshwater Oreochromis mossambicus, from various parts in the Luvuvhu River, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 73(7), pp. 1537-1542, 2010.

- Mahmoud, A.F; Hafez, A.E.S.E; Seadawy, H.G; Mohamed, E.F; Abdalllah, K.M. Quality Assessment and Impact of Gamma Irradiation on Histamine Content in Some Fish. Journal of Advanced Veterianry Research, 12(6) pp. 760-767, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bedane, T. D; Megersa, B; Abunna, F; Waktole, H; Woldemariyam, F.T; Tekle, M; Shimelis, E; Gutema, F.D. Occurrence, molecular characterization, and antimicrobial susceptibility of sorbitol non-fermenting Escherichia coli in lake water, fish and humans in central Oromia, Ethiopia. Scientific reports, 14(1), p. 12461, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.Y; Sharif, M.I; Adhikari, R.K; Faruque, O. Post mortem variation in total volatile base nitrogen and trimethyl lamine nitrogen between Galda (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) and Bagda (Panaeus monodon). University Journal of Zoology, vol. 28, pp. 7-10, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hoorzook, K. B; Pieterse, A, Heine, L, Barnard, T, G, Eds.; van Rensburg, N.J. Soul of the Jukskei River: the extent of bacterial contamination in the Jukskei River in Gauteng Province, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), p. 8537, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Palamuneli, L; Akoth, M. Experimental contamination of drinking water with fecal coliforms: Effects on health. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 39(1), pp. 101-105, 1993.

- Madilonga, R.T; Edokpayi, J.N; Volenzo, E.T; Durowujo, O.S; Odiyo, J.O. R.T. Water quality assessment and evaluation of human health risk in Mutangwi river, Limpopo province, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), p. 6765, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Geldreich, E.E. E; Gut feelings: enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) interactions with the host. Annual review of cell and developmental biology, 16(1), pp. 173-189, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ledwaba, S.E; Costa, D.V; Bolick, D. T; Giallourou, N; Medeiros, P.H; Swann, J.R; Traoré, A.N; Potgieter, N; Nataro, J.R; Guerrant, R.L. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infection induces diarrhea, intestinal damage, metabolic alterations, and increased intestinal permeability in a murine model. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.B; Kim, S.K; Yoon, J.W. Pathophysiology of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli during a host infection. Journal of Veterinary Science, 23(2), 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yacoub, A.M; Sabra, S.M; Al-Kourashi, M.K.D. A.M. Meat Quality and Hematological Indices of Oreochromis niloticus Fish Experimentally Exposed to Escherichia coli Toxins: A Recent Study. 2021.

- Hatt, B.E; Fletcher, T.D; Deletic, A. The influence of urbanization on the quality of stormwater runoff. Water Science and Technology, 49(7), pp. 63-70, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- McLennan, M.A. E. coli as an indicator of fecal contamination in the aquatic environment. Microbial Ecology, 48(3), pp. 259-269, 2004. [Google Scholar]

| Bacterial Strain | Reference | Use | Genes Present |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli (Commensal)a | PCR | Mdh | |

| Enterohaemorrhaging (EHEC) | ESCCO21b | PCR | Mdh, stx1, stx2 and aeaA |

| Enteroinvasive (EIEC) | ESCCOS ATCC 43893b | PCR | Mdh and ial |

| Enterotoxigenic (EPEC) | ESCCO 22b | PCR | Mdh, It and st |

| Enteropathogenic (EPEC) | S-ESCCO 16 PIb | PCR | Mdh, eaeA, bfp |

| Enteroaggregative (EPEC) | ESCCO 14b | PCR | Mdh and eagg |

|

aEnvironmental isolate confirmed by API 20E (OMNIMED®, Moorestone, NJ, USA) and PCR as commensal E. coli; bStrains purchased from National Health Laboratory Services (NHLS) confirmed with biochemical and PCR by the NHLS. | |||

| Sampling site | Conductivity (µs/cm) | TDS (mg/ℓ) | Temp (°C) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OD1 | 379 | 243 | 17,6 | 7,67 |

| OD2 | 377 | 241 | 16,9 | 8,17 |

| OD3 | 349 | 223 | 16,4 | 8,17 |

| OD4 | 343 | 220 | 16,1 | 7,9 |

| ND1 | 129,8 | 83,1 | 16,4 | 8,6 |

| ND2 | 138,5 | 88,9 | 17,2 | 8,2 |

| ND3 | 142,2 | 91,1 | 17,4 | 8,5 |

| TD1 | 24,6 | 15,6 | 13 | 8,4 |

| TD2 | 31,9 | 20,4 | 13 | 8,9 |

| TD3 | 42,1 | 26,4 | 12,7 | 8,8 |

| AD1 | 184,1 | 117,4 | 12,5 | 8,3 |

| AD2 | 182 | 116,6 | 11,6 | 8,35 |

| XD | 138,9 | 88,9 | 17,5 | 8,6 |

| Parameter |

Orlando Dam n = 4 |

Nandoni Dam n = 3 |

(F-Test value) | P.value |

| Conductivity | Mean = 362, sd = 18,65 | Mean = 136,8, sd = 6,37 | F (1,5) = 386.3 | p < 0.05 |

| TDS | Mean = 232, sd = 11.92 | Mean = 87.7, sd = 4.13 | F (1,5) = 385.9 | P < 0.05 |

| pH | Mean = 7.98, sd = 0.24 | Mean = 8.43, sd = 0,21 | F (1,5) = 6.82 | P < 0.05 |

| Temp | No significant difference | No significant difference | F (1,5) = 0.29 | P = 0.614 |

| Sampling site | Total coliform (MPN)/100 ml | E. Coli (MPN/100 mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Orlando Dam 1 | ˃ 2419.6 | 70 |

| Orlando Dam 2 | ˃ 2419.6 | 238.9 |

| Orlando Dam 3 | ˃ 2419.6 | 9.7 |

| Orlando Dam 4 | ˃ 2419.6 | 9.7 |

| Nandoni Dam 1 | ˃ 2416.6 | 6.3 |

| Nandoni Dam 2 | ˃ 2416.6 | 3.1 |

| Nandoni Dam 3 | ˃ 2416.6 | 7.2 |

| Thate Vondo Dam 1 | 2419.6 | 6.2 |

| Thate Vondo Dam 2 | 1986.3 | 0 |

| Thate Vondo Dam 3 | 1986.3 | 0 |

| Albasini Dam 1 | >2416.6 | 2 |

| Albasini Dam 2 | 2419.6 | 1 |

| Xikundu weir Dam 1 | 2416.6 | 42.2 |

| Sample site | N | F | Com | EPEC | EHEC | EIEC | ETEC | EAEC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orlando Dam | 4 | 4 | 4(100%) | 4(100%) | 1(25%) | 0(0%) | 4(100%) | 3(75%) |

| Nandoni Dam | 3 | 3 | 3(100%) | 4(100%) | 3(100%) | 0(0%) | 2 (67%) | 2(67%) |

| Thate Vondo Dam | 3 | 1 | 1(33%) | 1(33%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 1(33%) | 1(33%) |

| Albasini Dam | 2 | 2 | 2(100%) | 2(100%) | 1(50%) | 1(50%) | 1(50%) | 1(50%) |

| Xikundu weir | 1 | 1 | 1(100%) | 1(100%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 1(100%) | 1(100%) |

| Origin | Identification |

|---|---|

| Orlando Dam 1 | Pseudomonas stutzeri |

| Enterobacter cloacae complex | |

| Klebiella pneumoniae spp ozaenae | |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | |

| Orlando Dam 2 | Klepsiella pneumoniae spp pneumoniae |

| Enterobacter asburiae | |

| Orlando Dam 3 | Klepsiella pneumoniae spp pneumoniae |

| Aerococcus viridans | |

| Citrobacter braakii | |

| Citrobacter freundii | |

| Orlando Dam 4 | Serratia fonticola |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri | |

| Citrobacter braakii | |

| Nandoni Dam 1 | Enterobacter cloacae complex |

| Citrobacter freundii | |

| Alloicoccus otitis | |

| Plesiomonas shigelloides | |

| Nandoni Dam 2 | Citrobacter freundii |

| Plesiomonas shigelloides | |

| Nandoni Dam 3 | Sphingomonas paucimobilis |

| Thate Vondo Dam 1 | Citrobacter braakii |

| Thate Vondo Dam 2 | Edwardsiella tarda |

| Thate Vondo Dam 3 | Enterococcus faecalis |

| Enterobacter asbusiae | |

| Albasini Dam 1 | Klepsiella pneumoniae spp pneumoniae |

| Aeromonas sobria | |

| Albasini Dam 2 | |

| Aeromonas sobria | |

| Xikundu weir | Enterobacter cloacae complex |

| Plesiomonas shigelloides |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).