Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

13 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Tick Species Determination

2.3. Identification of Engorged Ticks

2.4. Detection and Genetic Characterization of Bacterial Agents

2.5. Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

3. Results

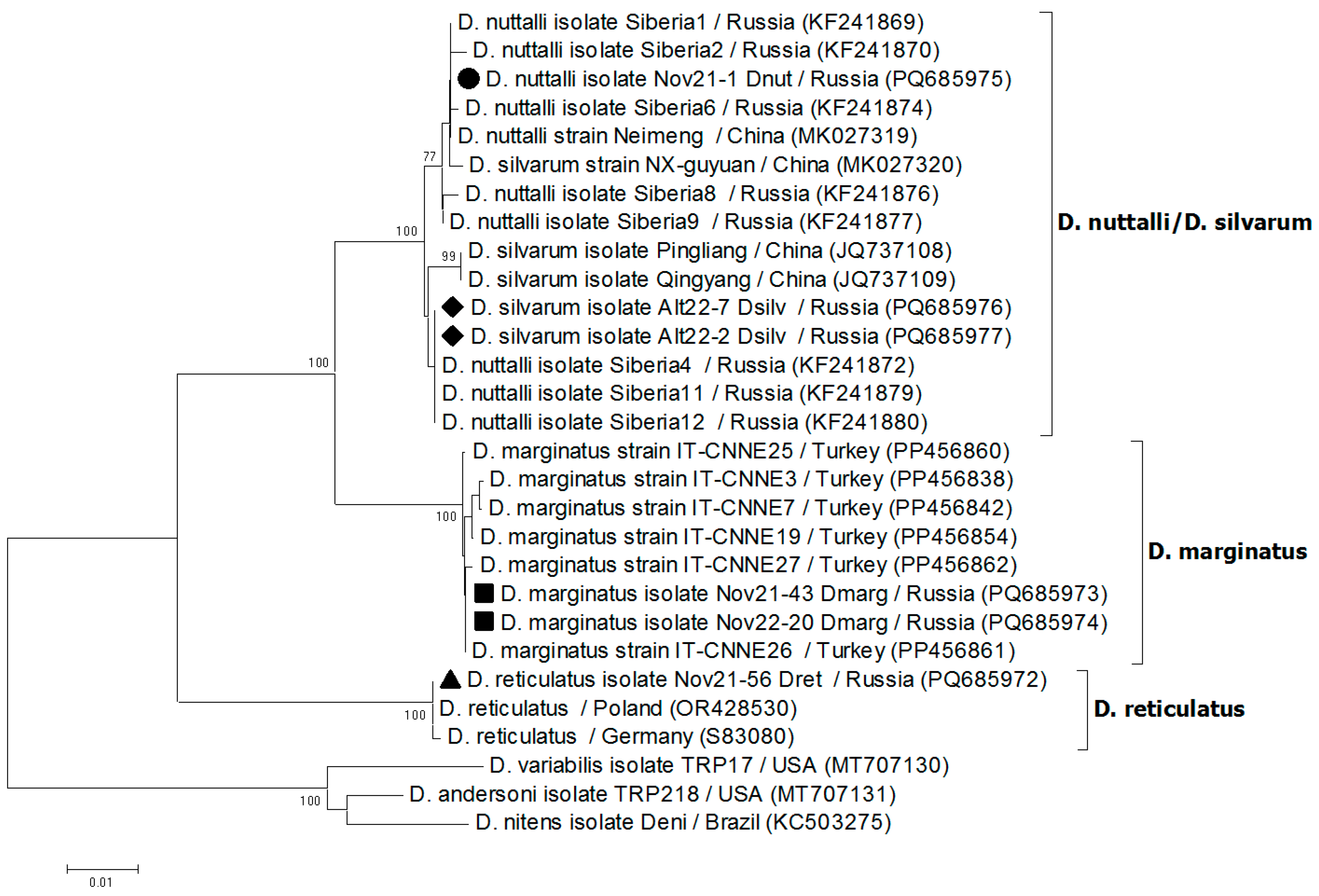

3.1. Tick Species

3.2. Determination of Human DNA in Ticks

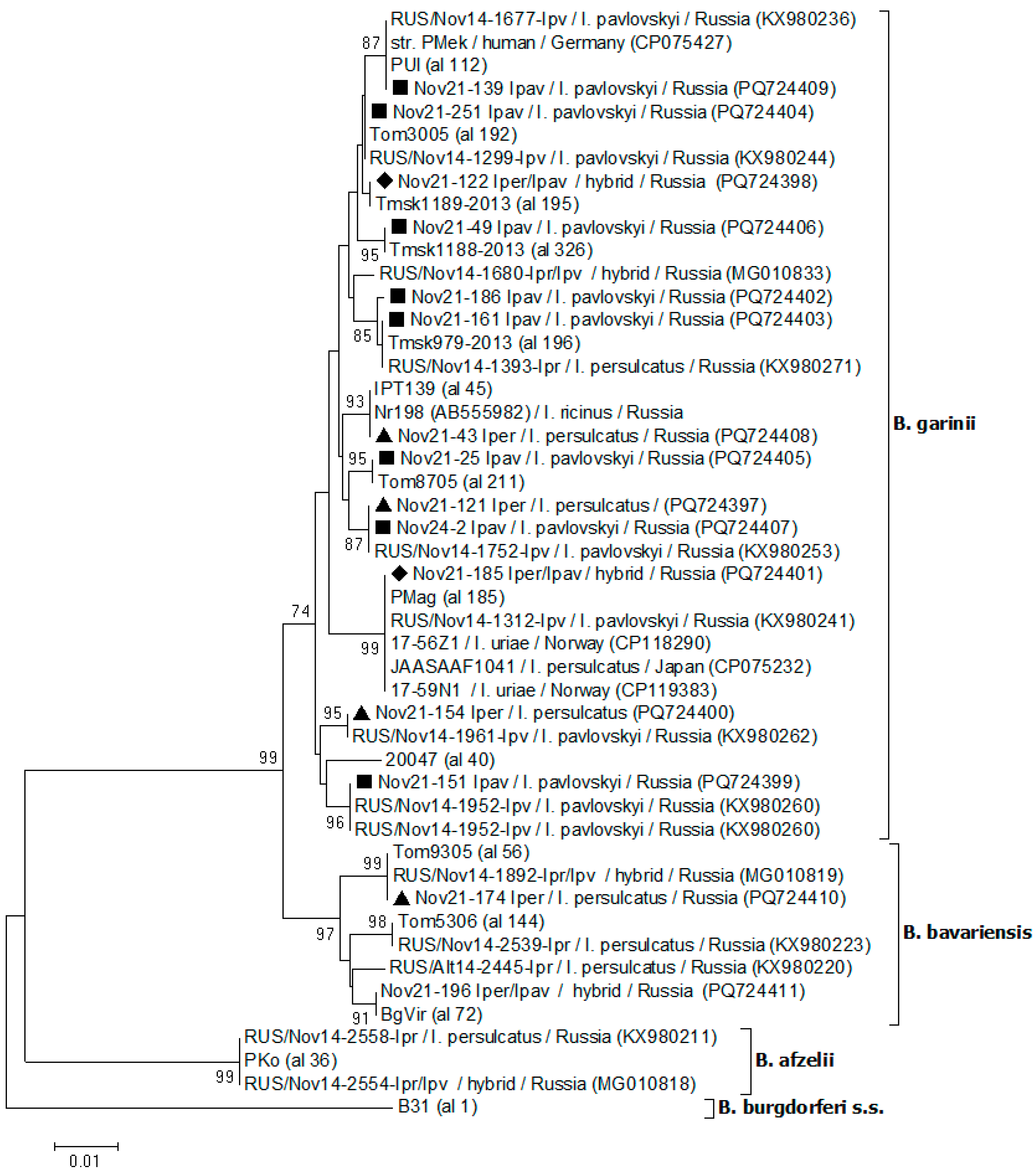

3.3. Detection of Borrelia spp. in Ticks

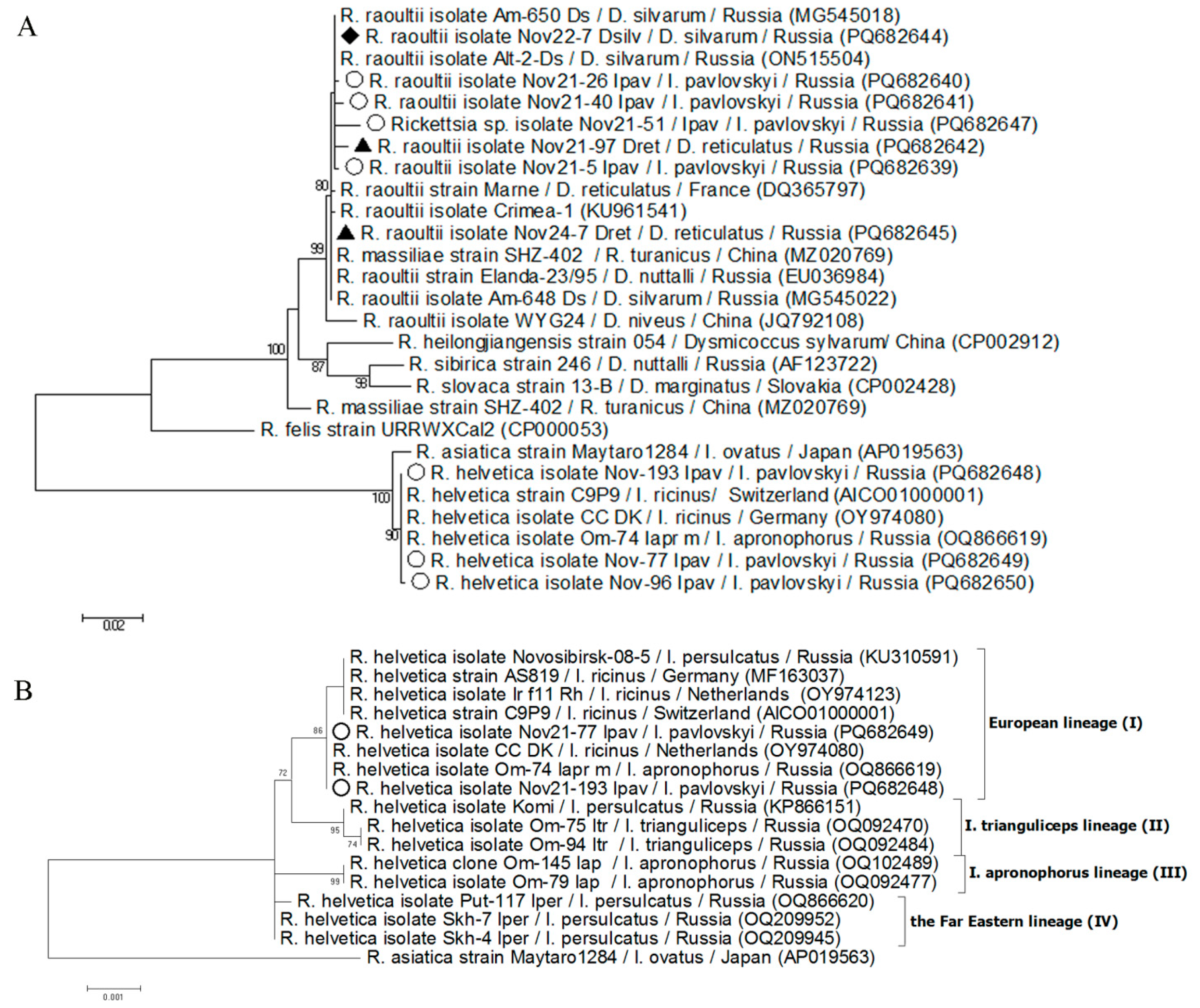

3.4. Detection of Rickettsia spp. in Ticks

3.5. Detection of Anaplasmataceae Bacteria in Ticks

| Tick species | No. of ticks | No. (%) of ticks containing DNA of tested agents | |||

| Aph | Em | Nm | All Anaplasmataceae | ||

| I. pavlovskyi | 137 | 3 (2.2) | 2 (1.5) | 4 (2.9) | 9 (6.6) |

| I. persulcatus | 58 | 0 | 0 | 2 (3.4) | 2 (3.4) |

| Hybrids | 58 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dermacentor spp. | 43 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All species | 296 | 3 (1.0) | 2 (0.7) | 6 (2.0) | 11 (3.7) |

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Livanova, N.N.; Livanov, S.G.; Panov, V.V. Features of the distribution of ticks Ixodes pavlovskyi on the border of the forest and forest-steppe zone of the Ob region. Parazitologiya 2011, 45, 94–102. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Yakimenko, V.V.; Mal’kova, M.G.; Tul’ko, Z.S.; Tkachev, S.E.; Makenov, M.T.; Vasilenko, A.G. Vector-borne viral infections of Western Siberia (regional aspects of epidemiology, ecology of pathogens and issues of microevolution). Publishing Center KAN: Omsk, 2019; pp. 1-312. (in Russian).

- Pomerantsev, B.I. New ticks of Ixodes family (Ixodidae). Parasit. Sbornik ZIN AS USSR 1948, 9, 36–46. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kovalevskiy, Yu.V.; Kuksgauzen, N.A.; Zhmaeva, Z.M. Data on the distribution of Ixodes pavlovskyi Pom. in the Altai (Acarina, Ixodidae). Parazitologiia 1975, 9, 518–521. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Bolotin, E.; Kolonin, G.; Kiselev, A.; Matjushina, O. The distribution and ecology of Ixodes pavlovskyi (Ixodidae) on Sykhote-Alin. Parazitologiya 1977, 3, 225–229. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Zamoto-Niikura, A.; Saigo, A.; Sato, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Sasaki, M.; Nakao, M.; Suzuki, T.; Morikawa, S. The presence of Ixodes pavlovskyi and I. pavlovskyi-borne microorganisms in Rishiri Island: an ecological survey. mSphere 2023, 8, e0021323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belyantseva, G.I.; Okulova, N.M. Seasonal changes in the activity of ixodid ticks in the natural focus of tick-borne encephalitis in the south of the Kemerovo region. Med. Parasit Parasit Bolezni. 1974, 43, 710–715. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Sapegina, V.F.; Ravkin, Yu.S. The finding of Ixodes pavlovskyi Pom. in North-East Altai. Parazitologiya 1969, 3, 22–23. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Romanenko, V.; Leonovich, S. Long-term monitoring and population dynamics of ixodid ticks in Tomsk city (Western Siberia). Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2015, 66, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rar, V.; Livanova, N.; Tkachev, S.; Kaverina, G.; Tikunov, A.; Sabitova, Y.; Igolkina, Y.; Panov, V.; Livanov, S.; Fomenko, N.; et al. Detection and genetic characterization of a wide range of infectious agents in Ixodes pavlovskyi ticks in Western Siberia, Russia. Parasit. Vectors 2017, 10, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalev, S. Y.; Mikhaylishcheva, M. S.; Mukhacheva, T. A. (2015). Natural hybridization of the ticks Ixodes persulcatus and Ixodes pavlovskyi in their sympatric populations in Western Siberia. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015, 32, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rar, V.; Livanova, N.; Sabitova, Y.; Igolkina, Y.; Tkachev, S.; Tikunov, A.; Babkin, I.; Golovljova, I.; Panov, V.; Tikunova, N. Ixodes persulcatus/pavlovskyi natural hybrids in Siberia: Occurrence in sympatric areas and infection by a wide range of tick-transmitted agents. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2019, 10, 101254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igolkina, Y.; Nikitin, A.; Verzhutskaya, Y.; Gordeyko, N.; Tikunov, A.; Epikhina, T.; Tikunova, N.; Rar, V. Multilocus genetic analysis indicates taxonomic status of "Candidatus Rickettsia mendelii" as a separate basal group. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2023, 14, 102104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenberg, E.I.; Nefedova, V.V.; Romanenko, V.N.; Gorelova, N.B. The tick Ixodes pavlovskyi as a host of spirochetes pathogenic for humans and its possible role in the epizootiology and epidemiology of borrelioses. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010, 10, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisen, L. Vector competence studies with hard ticks and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato spirochetes: a review. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2020, 11, 101359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, D.W.; Anderson, C.C.; Brissette, C.A. Borrelia miyamotoi: A Comprehensive Review. Pathogens 2023, 12, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollins, RE.; Sato, K.; Nakao, M.; Tawfeeq, MT.; Herrera-Mesías, F.; Pereira, RJ.; Kovalev, S.; Margos, G.; Fingerle, V.; Kawabata, H.; et al. Out of Asia? Expansion of Eurasian Lyme borreliosis causing genospecies display unique evolutionary trajectories. Mol. Ecol. 2023, 32, 786–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1Parola, P.; Paddock, C. D.; Socolovschi, C.; Labruna, M. B.; Mediannikov, O.; Kernif, T.; Abdad, M. Y.; Stenos, J.; Bitam, I.; Fournier, P. E.; Raoult, D. Update on tick-borne rickettsioses around the world: a geographic approach. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 26, 657–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Földvári, G.; Široký, P.; Szekeres, S.; Majoros, G.; Sprong, H. Dermacentor reticulatus: a vector on the rise. Parasit. Vectors 2016, 9, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kartashov, M.Yu.; Mikryukova, T.P.; Krivosheina, E.I.; Kuznecov, A.I.; Romanenko, V.N.; Moskvitina, N.S.; Ternovoj, V.A.; Loktev, V.B. Genotyping of tick-borne pathogens in Dermacentor reticulatus ticks collected in urban biotopes of Tomsk. Parazitologiya 2019, 53, 355–369. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakov, A.V.; Chekanova, T.A.; Petremgvdlishvili, K.; Timonin, A.V.; Valdokhina, A.V.; Shirokostup, S.V.; Lukyanenko, N.V.; Akimkin, V.G. High Prevalence of Rickettsia raoultii Found in Dermacentor Ticks Collected in Barnaul.; Altai Krai.; Western Siberia. Pathogens 2023, 12, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakubovskij, V.I.; Igolkina, Y.P.; Tikunov, A.Y. Panov V.V., Yakymenko V.V., Zhabykpayeva A.G., Epikhina T.I., Rar V.A. Genetic Diversity of Rickettsiae in Dermacentor spp. Ticks on the Territory of Western Siberia and Northern Kazakhstan. Mol. Genet. Microbiol. Virol. 2023, 38, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livanova, N.N.; Tikunov, A.Y.; Kurilshikov, A.M.; Livanov, S.G.; Fomenko, N.V.; Taranenko, D.E.; Kvashnina, A.E.; Tikunova, N.V. Genetic diversity of Ixodes pavlovskyi and I. persulcatus (Acari: Ixodidae) from the sympatric zone in the south of Western Siberia and Kazakhstan. Exp. Appl. Acarol 2015, 67, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanenko, V.N.; Sokolenko, V.V.; Maximova, Y.V. Local Formation of High Population Density of the Ticks Dermacentor reticulatus (Parasitiformes, Ixodidae) in Tomsk. Entmol. Rev. 2017, 97, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomenko, N.V.; Livanova, N.N.; Borgoiakov, V.Iu.; Kozlova, I.V.; Shulaĭkina, I.V.; Pukhovskaia, N.M.; Tokarevich, K.N.; Livanov, S.G.; Doroshchenko, E.K.; Ivanov, L.I. [Detection of Borrelia miyamotoi in ticks Ixodes persulcatus from Russia]. Parazitologiya 2010, 44, 201–211. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Margos, G.; Gatewood, A.G.; Aanensen, D.M.; Hanincová, K.; Terekhova, D.; Vollmer, S.A.; Cornet, M.; Piesman, J.; Donaghy, M.; Bormane, A.; et al. MLST of housekeeping genes captures geographic population structure and suggests a European origin of Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008, 105, 8730–8735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igolkina, Y.; Rar, V.; Krasnova, E.; Filimonova, E.; Tikunov, A.; Epikhina, T.; Tikunova, N. Occurrence and clinical manifestations of tick-borne rickettsioses in Western Siberia: First Russian cases of Rickettsia aeschlimannii and Rickettsia slovaca infections. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2022, 13, 101927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horsman, K.M.; Hickey, J.A.; Cotton, R.W.; Landers, J.P.; Maddox, L.O. Development of a human-specific real-time PCR assay for the simultaneous quantitation of total genomic and male DNA. J. Forensic. Sci. 2006, 51, 758–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igolkina, Y.; Yakimenko, V.; Tikunov, A.; Epikhina, T.; Tancev, A.; Tikunova, N.; Rar, V. Novel Genetic Lineages of Rickettsia helvetica Associated with Ixodes apronophorus and Ixodes trianguliceps Ticks. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33(7), 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbija, B.; Spitzweg, C.; Papoušek, I.; Fritz, U.; Földvári, G.; Mullett, M.; Ihlow, F.; Sprong, H.; Civáňová Křížová, K.; Anisimov, N.; et al. Dermacentor reticulatus - a tick on its way from glacial refugia to a panmictic Eurasian population. Int. J. Parasitol. 2023, 53, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartashov, M.Yu.; Krivosheina, E.I.; Svirin, K.A.; Tupota, N.L.; Ternovoi, V.A.; Loktev, V.B. Genotyping of tick-borne pathogens and determination of human attacking tick species in Novosibirsk and its suburbs. Russian Journal of Infection and Immunity 2022, 12, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanenko, V.N.; Kondratyeva, L.M. The infection of ixodid ticks collected from humans with the tick-borne encephalitis virus in Tomsk city and its suburbs. Parazitologiya 2011, 45, 3–10. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Tkachev, S.E.; Fomenko, N.V.; Rar, V.A.; Igolkina, Y.P.; Kazakova, Y.V.; Chernousova, N.Y. PCR-detection and molecular-genetic analysis of tick-transmitted pathogens in patients of Novosibirsk region, Russia. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2008, 298, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabitova, Y.; Rar, V.; Tikunov, A.; Yakimenko, V.; Korallo-Vinarskaya, N.; Livanova, N.; Tikunova, N. Detection and genetic characterization of a putative novel Borrelia genospecies in Ixodes apronophorus / Ixodes persulcatus / Ixodes trianguliceps sympatric areas in Western Siberia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2023, 14, 102075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhacheva, TA.; Kovalev, SY. Borrelia spirochetes in Russia: Genospecies differentiation by real-time PCR. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014, 5, 722–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margos, G.; Hofmann, M.; Casjens, S.; Dupraz, M.; Heinzinger, S.; Hartberger, C.; Hepner, S.; Schmeusser, M.; Sing, A.; Fingerle, V.; et al. Genome diversity of Borrelia garinii in marine transmission cycles does not match host associations but reflects the strains evolutionary history. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2023, 115, 105502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savel'eva, M.V.; Krasnova, E.I.; Khokhlova, N.I.; Filimonova, E.S.; Provorova, V.V.; Rar, V.A.; Tikunova, N.V. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of diseases caused by Borrelia spp. in the inhabitants of the Novosibirsk region in 2015–2017. Journal Infectology 2018, 10, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silaghi, C.; Hamel, D.; Thiel, C.; Pfister, K.; Pfeffer, M. Spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks, Germany. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 890–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, K.; Lindquist, O.; Pahlson, C. Association of Rickettsia helvetica with chronic perimyocarditis in sudden cardiac death. Lancet 1999, 354, 1169–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, K.; Elfving, K.; Páhlson, C. Rickettsia helvetica in patient with meningitis, Sweden 2006. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010, 16, 490–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shpynov, S.; Fournier, P. E.; Rudakov, N.; Tarasevich, I.; Raoult, D. Detection of members of the genera Rickettsia, Anaplasma, and Ehrlichia in ticks collected in the Asiatic part of Russia. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1078, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shpynov, S. N.; Fournier, P. E.; Rudakov, N. V.; Samoilenko, I. E.; Reshetnikova, T. A.; Yastrebov, V. K.; Schaiman, M. S.; Tarasevich, I. V.; Raoult, D. Molecular identification of a collection of spotted Fever group rickettsiae obtained from patients and ticks from Russia. Am..J Trop. Med. Hyg. 2006, 74, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Locus | Organism | Reaction | Primer name | Primer sequences 5’-3’ | T# (°С) | References |

| ITS2 | Ixodidae | conventional | F-ITS2 | cacactgagcacttactctttg | 57 | [23] |

| R1-ITS2 | actggatggctccagtattc | |||||

| cox1 | I. persulcatus | conventional | Ixodes-F | acctgatatagctttccctcg | 55 | [10] |

| Ipers-R | ttgattcctgttggaacagc | |||||

| I. pavlovskyi | conventional | Ixodes-F | acctgatatagctttccctcg | 55 | [10] | |

| Ipav-R | taatccccgtggggacg | |||||

| Ixodidae | conventional | C1 | accacaaagacattggaactatatat | 50 | [23] | |

| C2 | aatccaggaagaataagaatatatac | |||||

| D. reticulatus | conventional | Dret -F | ctaagacaacccggaacattaattg | 60 | This study | |

| Dret-R | aaaccctaaaagaccaattgcggc | |||||

| IGS | B. burgdorferi s.l. | Primary | NC1 | cctgttatcattccgaacacag | 50 | [10] |

| NC2 | tactccattcggtaatcttggg | |||||

| Nested | NC3 | tactgcgagttcgcgggag | 50 | |||

| NC4 | cctaggcattcaccatagac | |||||

| p66 | B. miyamotoi | Primary | M3 | ttctatatttggacacatgtc | 50 | [25] |

| M4 | cagattgtttagttctaatccg | |||||

| Nested | M1 | ctaaattattaaatccaaaatcg | 50 | |||

| M2 | ggaaatgagtacctacatatg | |||||

| clpA | B. burgdorferi s.l. | Primary | clpAF1237 | aaagatagatttcttccagac | 50 | [26] |

| clpAR2218 | gaatttcatctattaaaagctttc | |||||

| Nested | clpAF1255 | gacaaagcttttgatattttag | 50 | |||

| clpAR2104 | caaaaaaaacatcaaattttctatctc | |||||

| р83/100 | B. burgdorferi s.l. | Primary | F7 | ttcaaagggatactgttagagag | 50 | [10] |

| F10 | aagaaggcttatctaatggtgatg | |||||

| Nested | F5 | acctggtgatgtaagttctcc | 54 | |||

| F12 | ctaacctcattgttgttagactt | |||||

| gltA | Rickettsia spp. | Primary | glt1 | gattgctttacttacgaccc | 52 | [10] |

| glt2 | tgcatttctttccattgtgc | |||||

| Nested | glt3 | tatagacggtgataaaggaatc | 53 | |||

| glt4 | cagaactaccgatttctttaagc | |||||

| Ca. R. tarasevichiae | Nested | RT1 | tactaaaaaagtcgctgttcattc | 56 | [10] | |

| RT2 | tgttgcaaacatcatgcgtaa | |||||

| SFGR | Nested | RH1 | gtcagtctactatcacctatatag | 54 | [10] | |

| RH3 | taaaatattcatctttaagagcga | |||||

| ompB | Rickettsia spp. | Primary | B1 | atatgcaggtatcggtact | 56 | [27] |

| B2 | ccatataccgtaagctacat | |||||

| Nested | B3 | gcaggtatcggtactataaac | 56 | |||

| B4 | aatttacgaaacgattacttccgg | |||||

| 16S rRNA | Anaplasmataceae | Primary | Ehr1 | gaacgaacgctggcggcaagc | 57 | [10] |

| Ehr2 | agtaycgraccagatagccgc | |||||

| Nested | Ehr3 | tgcataggaatctacctagtag | 60 | |||

| Ehr4 | ctaggaattccgctatcctct |

| Amount (µl) of human blood in a tick | The No (%) of ticks containing different amount of human blood | ||||

| I. pavlovskyi (n=137) | I. persulcatus (n=58) | Hybrids (n=58) | Dermacentor spp. (n=43) | All species (n=296) | |

| Nd (<0.4) | 106 (77.4) | 37 (63.8) | 48 (82.8) | 33 (76.7) | 224 (75.7) |

| 0.4-0.9 | 12 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 32 |

| 1.0-1.9 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 15 |

| 2.0-2.9 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| 3.0-3.5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| 3.5-5.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal 0.4-5.5 | 23 (16.8) | 15 (25.9) | 8 (13.8) | 9 (20.9) | 55 (18.6) |

| 5.5-10 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| 10-20 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 20-50 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| 50-106 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Subtotal5.5-106 | 8 (5.8) | 6 (10.3) | 2 (3.4) | 1 (2.3) | 17 (5.7) |

| Tick species | No. of ticks | No. (%) of ticks containing DNA of tested agents* | ||||

| Bg | Ba | Bb | all B. burgdorferi (s.l.) | Bm | ||

| I. pavlovskyi | 137 | 17 (12.4) | 2 (1.5) | 0 | 19 (13.9) | 5 (3.6) |

| I. persulcatus | 58 | 4 (6.9) | 0 | 1 (1.7) | 5 (8.6) | 5 (8.6) |

| Hybrids | 58 | 5 (8.6) | 0 | 1 (1.7) | 6 (10.3) | 1 (1.7) |

| Dermacentor spp. | 43 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All species | 296 | 26 (8.8) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) | 30 (10.1) | 11 (3.7) |

| Tick species | No. of ticks | No. (%) of ticks containing DNA of tested agents | ||||

| Rt | Rr | Rh | Rsp | All Rickettsia spp. | ||

| I. pavlovskyi | 137 | 1 (0.7) | 4 (2.9) | 3 (2.2) | 1 (0.7) | 9 (6.6) |

| I. persulcatus | 58 | 26 (44.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 (44.8) |

| Hybrids | 58 | 3 (5.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (5.2) |

| D. reticulatus. | 38 | 0 | 10 (26.3) | 0 | 0 | 10 (26.3) |

| D. nuttalli / D. silvarum | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| D. marginatus | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All species | 296 | 30 (10.1) | 15 (5.1) | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | 49 (16.6) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).