1. Introduction

Ticks (order Ixodida) are divided into three main families: Ixodidae (722 species), Argasidae (208 species), and Nutalliellidae (1 species) [

1,

2]. Hard ticks, belonging to the family Ixodidae, are highly specialized obligate blood-sucking ectoparasites of terrestrial vertebrates, primarily birds and mammals, and to a lesser extent, reptiles [

3,

4]. Ticks are significant vectors of various pathogenic microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, and protozoa, and represent one of the three main components of natural and synanthropic foci of transmissible infections [

5]. Three abundant species of ixodid ticks have endemic significance in the Tomsk region:

D. reticulatus,

I. pavlovskyi, and

I. persulcatus [

6]. All of them, to varying degrees, are involved in the spread of both well-known and regularly detected pathogenic microorganisms (

Anaplasma phagocytophilum,

Babesia spp.,

Bartonella spp.,

Borrelia burgdorferi s.l.,

B. miyamotoi,

Ehrlichia chaffeensis,

E. muris,

Francisella tularensis,

Rickettsia spp., TBEV, and West Nile virus), as well as newly discovered ones (viruses of the genera

Phlebovirus,

Uukivirus, and YEZV) [

7,

8,

9,

10]. In Russia, based on the results of an analysis of 5318

I. persulcatus and

I. ricinus ticks sampled in 23 regions revealed of five YEZV isolates in

I. persulcatus ticks from three regions: Khabarovsk, Primorsky and Transbaikal territory [

10]. However, within foci of tick-borne infections located in anthropogenically transformed territories, the species

I. pavlovskyi is more significant, currently dominating urban biotopes of Tomsk over both

I. persulcatus and

D. reticulatus [

11]. Its ornithophilicity has been observed and documented at almost all life cycle stages (larva, nymph, imago) [

12].

Given the wide range of pathogens carried by ixodid ticks, the identification of novel infectious agents capable of causing disease in humans and animals is of particular interest. A notable example is the YEZV (

Orthonairovirus yezoense), a recently identified member of the genus

Orthonairovirus, order

Bunyavirales, first detected in Japan on Hokkaido Island in 2019 [

13]. The presence of the YEZV has been detected in ixodid ticks (

D. silvarum,

Haemaphysalis megaspinosa,

H. japonica,

I. ovatus,

I. persulcatus), which are vectors, in wild animals (

Cervus nippon yesoensis,

Emberiza spodocephala,

Procyon lotor), as well as in the blood of 10 patients from Japan (since 2014) and 19 from China [

10,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. The YEZV has not been previously detected in

I. pavlovskyi.

The clinical manifestations caused by the YEZV in patients from Japan were more pronounced compared to the patients from China and were accompanied by an increase in body temperature up to 39°C, loss of appetite, leukopenia, lymphocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated enzyme levels (alanine aminotransferase, aspartate transaminase, creatine kinase, lactate dehydrogenase) and ferritin, which may indicate liver damage. Furthermore, cases of blood coagulation disorders were identified. The disease manifested in the Chinese patients as a milder form. In addition to elevated body temperature and changes in blood cell counts and liver enzymes, headache, dizziness, joint pain, visual disturbances, shortness of breath, and fatigue were also observed [

13,

14,

16,

18]. As Matsuno [

20] article asserts, the disease manifested as severe in eight out of 18 patients. Furthermore, gastrointestinal tract disorders were detected in 9 patients, a phenomenon heretofore unreported in the extant literature. Moreover, neurological symptoms were observed in 5 patients, the nature of which was not specified in the publication. The clinical manifestation of the disease is subject to its variation depending on various factors, including the patient’s age and medical history, the presence of co-infection, and concomitant medication use. It is important to note that all patients infected with the YEZV exhibited full recovery within a period from two to three weeks [

13,

14,

16,

18,

20].

According to the most recent official classification, the genus

Orthonairovirus of the family

Nairoviridae includes 51 species, for which argasid or ixodid ticks serve as vectors [

21]. The genome of the

Orthonairovirus is characterized of three linear single-stranded negative-sense RNA (ssRNA(–)) segments with a size ranging from 17.2 to 20.1 kb (the S segment is 1.4–3.8 kb, the M segment is 3.9–5.9 kb, and the L segment is 11.7–12.6 kb) [

22]. Most members of the genus

Orthonairovirus have been demonstrated to be capable of replicating in both arthropods (argasid and ixodid ticks) and vertebrate animals [

23]. The recent discovery of previously unknown viral agents in ixodid tick populations indicates that the spectrum of pathogens carried by these ectoparasites is far from being fully understood [

7,

8,

9,

10]. This underscores the need for modern research methods that can enhance detection efficiency and enable rapid and timely monitoring of new or re-emerging pathogens. A representative example of such a method is metagenomic next-generation sequencing [

24]. Recent studies have indicated a marked increase in the number of such studies over the past 15 years [

25]. The objective of the present study was to perform the genomic characterization of a newly identified orthonairovirus, designated as YEZV, which was detected by metagenomic sequencing in female

I. pavlovskyi ticks collected in Tomsk.

2. Materials and Methods

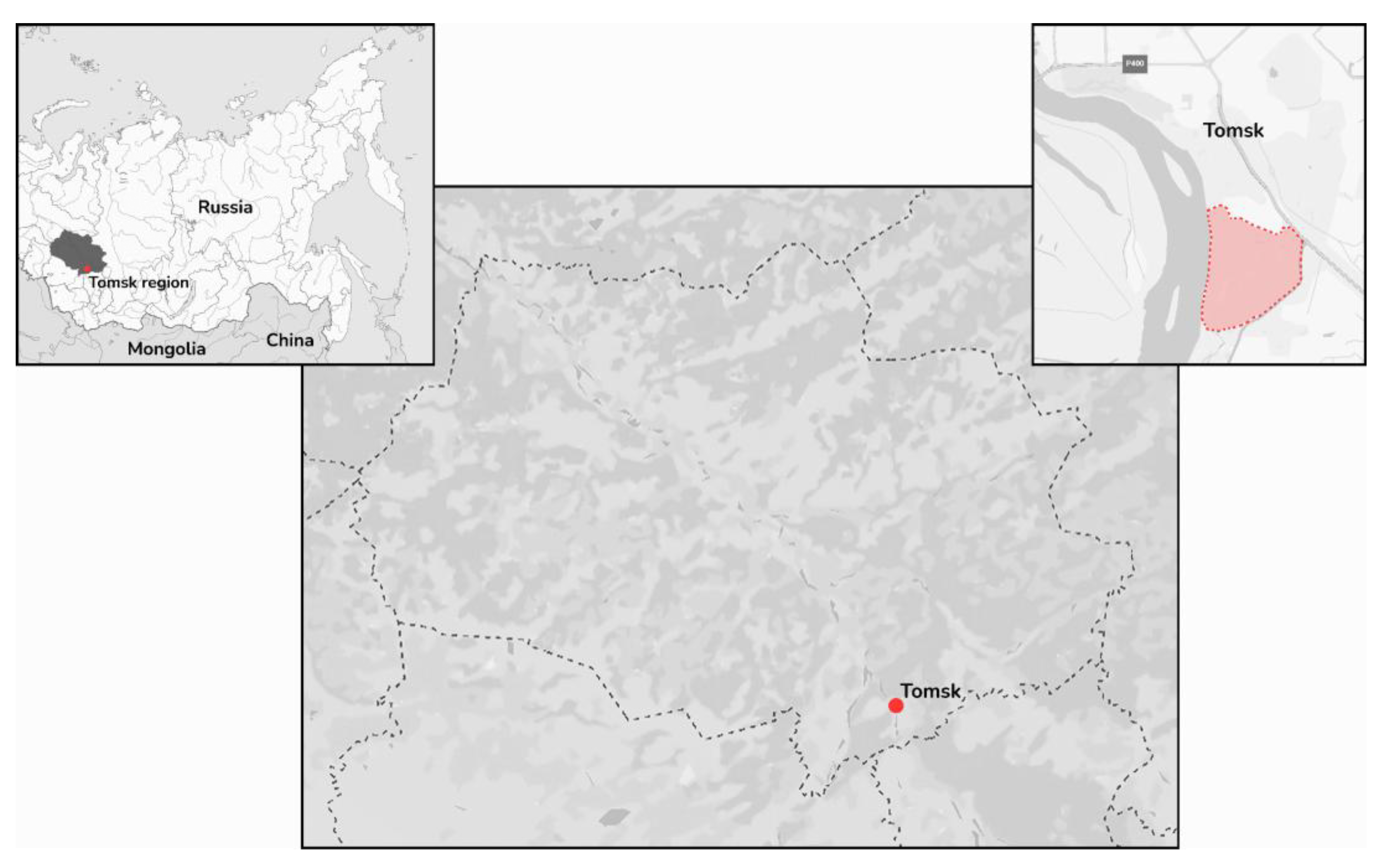

2.1. Sampling

The collection of female

I. pavlovskyi was conducted in June 2024 in Tomsk (Tomsk region, Russia). The ixodid ticks were collected using the standard flagging method from the vegetation. The collected ticks were individually placed into 1.5 ml tubes and delivered to the laboratory while still alive. There, they were stored at 4 °C until species identification. Using morphological keys [

26], the species, sex, and stage of the collected ticks were determined with a binocular microscope. After identification, each tick was washed in 70% ethanol and sterile water, then placed individually into a 0.5 ml tube, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80 °C.

2.2. Enrichment of Virus-like Particles, Nucleic Acid Extraction, Library Preparation and Metagenomic Sequencing

The enrichment of virus-like particles was conducted in accordance with a modified NetoVir protocol [

27]. Prior to homogenization, individual ixodid tick samples were combined into pools. Thus, two pools of eight individuals each were prepared for

I. pavlovskyi. A negative control consisting only of Hanks’ solution with phenol red (BioloT, Saint-Petersburg, Russia), was also used for each processed batch of tick pools. The homogenization of the pools was conducted using 2.8 mm ceramic beads (Allsheng, Hangzhou, China) and Hank’s solution with phenol red (BioloT, Saint-Petersburg, Russia) on a Bioprep-24 instrument (Allsheng, Hangzhou, China) at a speed of 7000 rpm at room temperature for 90 s. This procedure was repeated 4 times, with tubes placed at -20 °C for 1 min between repeats. The pools were centrifuged at 17,000g at 3 °C for 3 min. The supernatant was passed through a 0.8 µm pore size centrifugal microfilter (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany). The filtrate was treated with micrococcal nuclease (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Ipswich, MA, USA) and benzonase (diaGene, Moscow, Russia). Nucleic acids were extracted after filtration using a column-based RNA extraction kit (Biolabmix, Novosibirsk, Russia) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Full-transcriptome amplification was performed using the WTA2 kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) according to the NetoVir protocol. The PCR product was purified using a kit for DNA and RNA extraction from reaction mixtures (Biolabmix, Novosibirsk, Russia). After this, the PCR products from the two pools were combined into one, and library preparation began. Libraries for massively parallel sequencing were prepared using the SyntEra-DNA kit (Syntol, Moscow, Russia) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Following library preparation, a reconditioning PCR was performed for the two samples using the SyntEra-DNA kit with standard Illumina P5 (5’-AATGATACGGCGACCGAGATCT-3’) and P7 (5’-CAAGCAGAAGGGCATACGAGAT-3’) primers, and the Encyclo Plus PCR kit (Evrogen, Moscow, Russia). Two-sided size selection was then performed using AMPure XP magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). The reaction mixture consisted of the following components: 16 µl dH2O, 2.5 µl 10x Encyclo buffer, 0.5 µl 50x dNTP mix, 2.5 µl P7 and P5 primer mix, 0.5 µl 50x Encyclo polymerase mix, and 3 µl DNA. PCR was performed using the following program: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, 6 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and final elongation at 72 °C for 1 min. After reconditioning PCR following purification and size selection, fragment length analysis was conducted on a TapeStation 4150 instrument (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The prepared libraries were sequenced on a Genolab M platform (GeneMind Biosciences, Shenzhen, China) with 150-nucleotide paired-end reads with an estimated average of 10 million reads per sample.

2.3. Virome Data Analysis

The raw reads obtained were processed using the ViPER pipeline v2.3 [

28]. Particularly, untreated raw reads were trimmed with Trimmomatic v0.39 [

29] to remove Nextera adapters and low-quality reads. The trimmed reads were then aligned to the contamination control library (negative control sample) using Bowtie2 [

30] to discard contamination-related reads from laboratory sources. The remaining reads were then assembled into contigs using metaSPAdes v4.2.0 [

31]. Contigs were subsequently filtered on length (>200 bp) and clustered based on their coverage and identity threshold (80 and 95%, respectively). The contigs were taxonomically classified using Diamond v2.1.11 [

32] with the NCBI nr database, and further visualized with KronaTools v2.8 [

33] based on a common ancestor approach. Furthermore, the reads were mapped to the classified contigs using bwa-mem2 v2.2.1 [

34] to quantify their abundance.

2.4. Sequence Analysis

The Geneious v2025.1.3 software (Biomatters, Auckland, New Zealand) and the ExPASy [

35] were used for sequence analysis and subsequent visualization of the results. The genome organization scheme was prepared based on the obtained metagenomic data sequences annotation using the online graphical editor BioRender. Protein domain organization was predicted using InterProScan v106.0 [

36], while DeepTMHMM v1.0.44 [

37] was used to predict protein transmembrane domains. The presence of a signal peptide and signal peptidase cleavage site was predicted using ProP v1.0 [

38] and SignalP v6.0 [

39]. N- and O-glycosylation sites were predicted using NetNGlyc v1.0 [

40] and NetOGlyc v4.0 [

41], respectively.

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

For phylogenetic analysis, nucleotide sequences of the L, M, and S segments of YEZV and Sulina virus (SULV) isolates (

Table S1), as well as the amino acid sequences of the L segment from representatives of the genus

Orthonairovirus (

Table S2), were used. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using the MAFFT v7.511 online server [

42], with the automatic selection of the best alignment algorithm. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using IQ-TREE 3 [

43] with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The selection of the most appropriate model was performed by ModelFinder [

44]. As a result, the GTR+F+J+G4 algorithm was chosen for the L segment, TIM2+F+J+R2 for the M segment, TPM2u+F+J+R2 for the S segment, and Q.YEAST+F+J+R7 for the L segment amino acid sequences. Phylogenetic trees were visualized in R using the ggtree v3.6.2 [

45] and phytools v2.4-4 [

46] packages. The evolutionary distances of the amino acid and nucleotide sequences for the three segments of YEZV isolates were estimated using the p-distance method [

47]. The resulting values were converted to identity percentages. Visualization of the results was performed in Python using the seaborn v0.13.2 [

48] and matplotlib v3.10.3 [

49] packages.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the Metagenomic Library

In June 2024, a total of 12

I. pavlovskyi ticks were collected from the vegetation in the park area of the Tomsk Polytechnic University «Polytechnic» stadium (

Figure 1). They were combined into two pools.

After sample preparation according to the modified NetoVIR protocol, they were combined into a single pool. A cDNA library was then prepared for this pool, and metatranscriptomic sequencing was performed. This resulted in 23,418,766 reads. After analysing the raw data, 196 viral contigs (0.5% of the total) were obtained. Of these, 93 belonged to bacteriophages (families

Haloferuviridae,

Shortaselviridae,

Stanwilliamsviridae,

Autographviridae,

Soleiviridae,

Casjensviridae,

Straboviridae,

Zierdtviridae), while 37 belonged to DNA viruses (

Baculoviridae,

Bamfordviridae,

Microviridae,

Genomoviridae,

Parvoviridae and

Inoviridae) and 55 to RNA viruses (

Baculoviridae,

Deltaflexiviridae,

Virgaviridae,

Tombusviridae,

Totiviridae,

Sedoreoviridae,

Partitiviridae,

Hypoviridae,

Nairoviridae,

Peribunyaviridae,

Rhabdoviridae,

Retroviridae,

Botourmaviridae), and 11 to unclassified viruses. The dominant viral taxa are shown in

Table 3. For the YEZV, four contigs covering > 99% of the genome with an average read depth of > 1500 were obtained.

3.2. Genomic Characterization of the Detected Yezo Virus

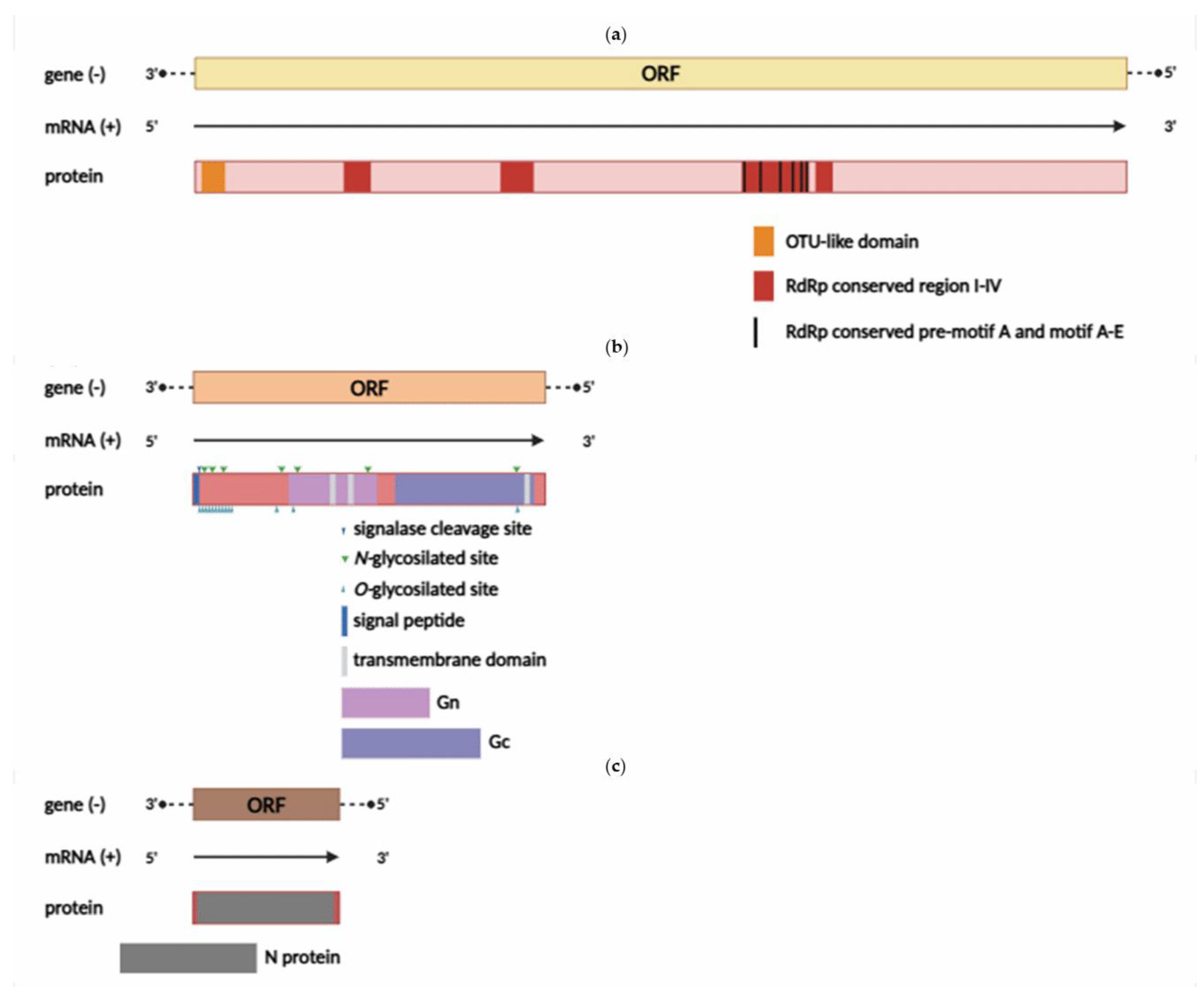

The YEZV genome is a linear ssRNA(–) consisting of three segments (

Figure 2).

The L segment is 12,103 bp in length and encodes an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) (3938 aa). Previous studies have shown that RdRp contains an OTU-like protease domain, a polymerase module consisting of pre-motif A and motifs A-E, as well as four conserved regions I-IV [

50,

51]. Amino acid sequence alignment confirmed that the RdRp of the YEZV contains all the highly conserved regions (

Figure S3).

The M segment is 4247 bp in length and encodes a glycoprotein precursor complex (GPC) (1356 aa), which consists of two subunits — Gn (from 369 to 687 aa) and Gc (from 777 to 1319 aa). The position of the N-terminal signal peptide and its cleavage site were predicted to be between 21 and 22 aa. In the N-terminal part of the glycoprotein, a high density of O- and N-glycosylation sites, susceptible to proteolytic cleavage, was identified. The Gn protein contains one O- and two N-glycosylation sites, two transmembrane domains (the first is between 541 and 560 aa, and the second is between 668 and 682 aa), and a pair of conserved zinc finger domains. These have also been found in Meihua Mountain virus and Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever viruses (CCHFV) [

51,

52]. The Gc protein contains one O- and one N-glycosylation site, as well as one transmembrane domain located between 1283 and 1303 aa. In addition, the nucleoprotein of the YEZV has conserved fusion loop regions (bc loop, cd loop, ij loop), like those observed in other orthonairoviruses [

53] (

Figure S4).

The S segment is 1685 bp in length and encodes a nucleocapsid protein (502 aa). A detailed study has established the structural organization of the nucleocapsid protein in nairovirus representatives, revealing two main domains: a globular head and a stem, along with sites that are necessary for binding RNA/DNA molecules [

54]. The alignment of the nucleotide sequences of the two domains showed that YEZV isolates differ from viruses of the NSD (Nairobi sheep disease) genogroup and exhibit high conservation among the YEZV isolates (

Figure S5).

3.3. Nucleotide and Amino Acid Identity

To assess the degree of nucleotide (

Figure S6) and amino acid (

Figure S7) identity of the genome segments of our identified YEZV, a comparative analysis was performed with other virus isolates genome segments sequences. The degree of nucleotide identity for the L segment ranged from 90.848% to 91.399%. The maximum value was observed for isolate PV061572.1 (

I. persulcatus, Khabarovsk region, Far East). For the M segment, the identity values ranged from 89.336% to 90.054%. The closest match was found for isolate PQ475627.1 (

I. persulcatus, Inner Mongolia, China). For the S segment, the identity values ranged from 91.328% and 92.341%. The closest match was found for isolate PV061580.1 (

I. persulcatus, Primorsky region, Far East).

The amino acid identity for the RdRp protein was between 98.502% and 98.959%, with the highest value being recorded for isolate WWT48702.1 (I. persulcatus, Jilin Province, China). According to the ICTV species demarcation criteria (<93% identity in L amino-acid sequence for new species in the genus Orthonairovirus), the detected virus belongs to the YEZV. For the GPC, the identity varied from 93.732% to 94.764%. The closest matches were two isolates, XJP49230.1 (I. persulcatus, Inner Mongolia, China). For the nucleoprotein, the identity values ranged from 96.414% to 97.200%. The highest value was observed for isolate XJQ61045.1 (Homo sapiens (human metagenome), Heilongjiang Province, China).

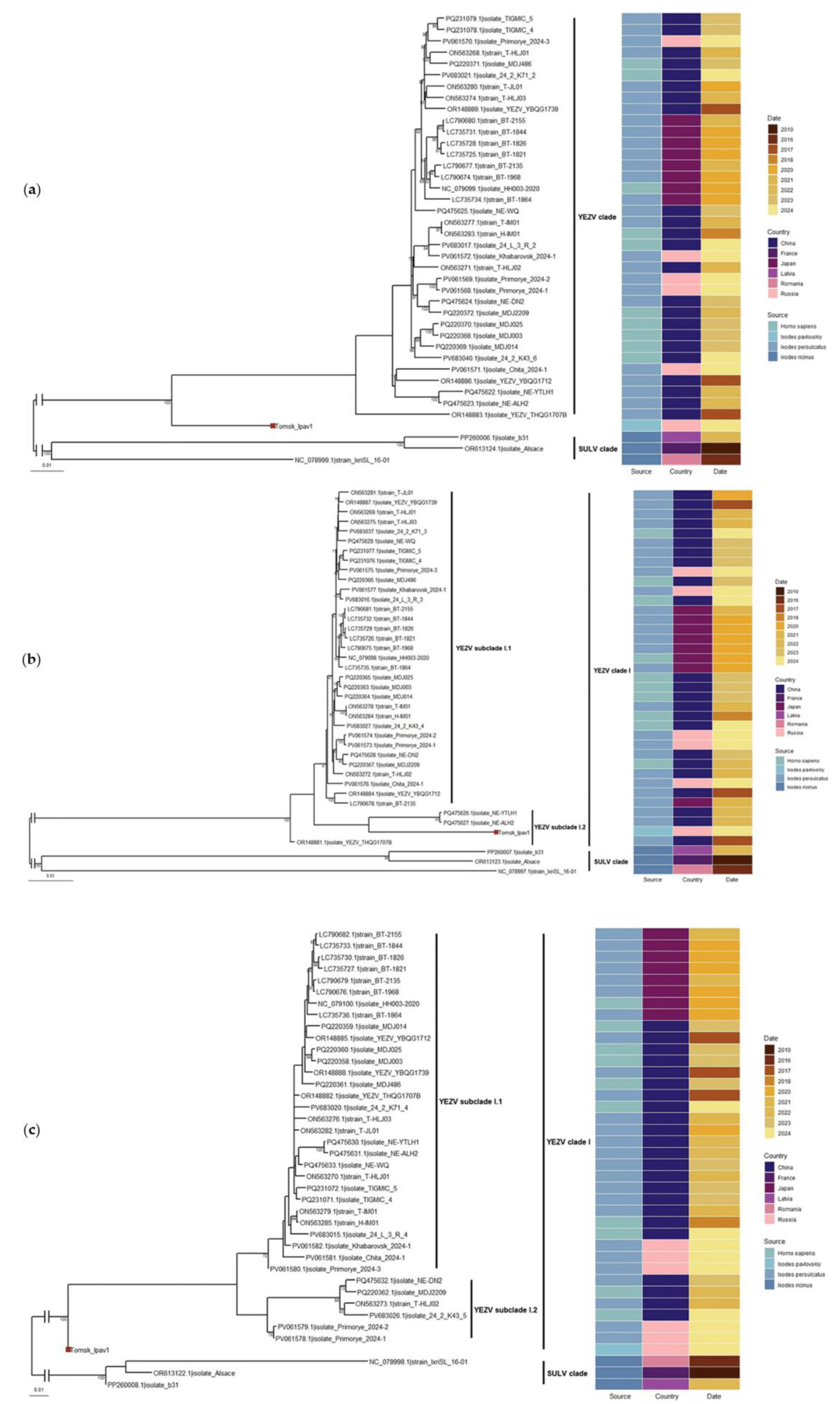

3.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

Phylogenetic analysis, performed based on the nucleotide sequences of the three segments (L, M, S) of the YEZV genome, demonstrated that all isolates of this virus form a well-supported monophyletic clade, which is clearly distinct from the closely related SULV. The isolates are distributed without a specific pattern based on the source and year of virus isolation. Our newly discovered YEZV isolate (Tomsk_Ipav1) forms a sister clade to previously identified virus isolates based on the L and S segments. For the M segment, our isolate exhibited a closer evolutionary relationship with the segments of two Chinese isolates (

Figure 8). However, the bootstrap support is low.

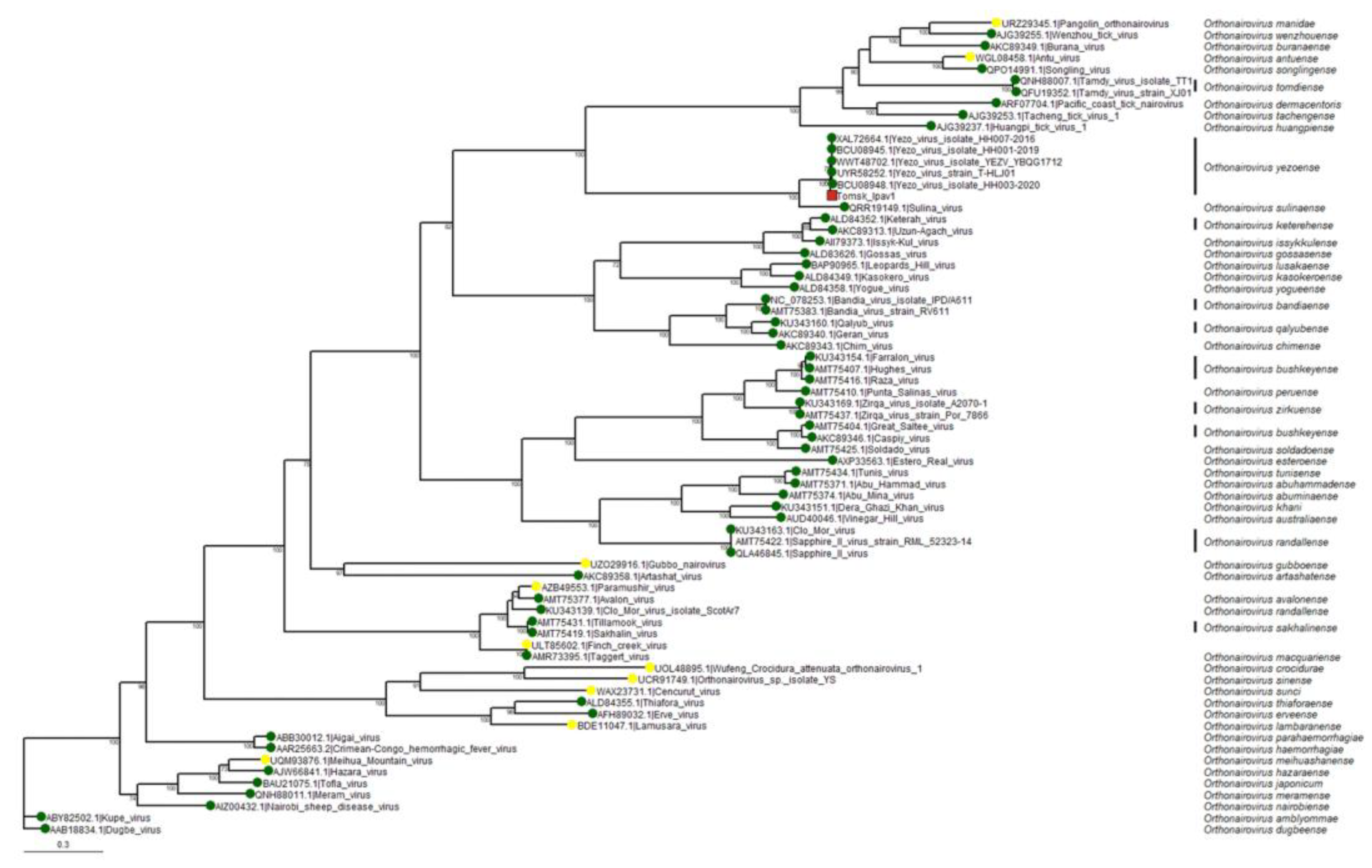

To clarify the evolutionary relationships of our discovered isolate within the genus

Orthonairovirus, a phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the amino acid sequence of the RdRp (

Figure 9).

The analysis included 65 representatives of the genus

Orthonairovirus and 6 YEZV isolates, including the one we discovered. The resulting phylogram shows that all the YEZV isolates, including the variant detected in the study, form a well-supported species subclade, clearly separate from the other viruses in the genus. Overall, the tree structure is consistent with previously published data [

21]. Thus, the relatively high percentage of differences in the virus genome segments, obtained by comparing the results on the identity of amino acid and nucleotide sequences identities between YEZV isolates, as well as the phylogenetic analysis results, indicates the discovery of a new genetic variant of Yezo virus circulating in Tomsk region (Western Siberia, Russia).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we first demonstrated the presence of YEZV in the Tomsk region (Western Siberia), significantly expanding its geographical range beyond the several regions of Japan, China, and Russia in which it was previously found. Previously, in Russia, the virus was only found in Eastern Siberia (the Zabaykalsky region) and the Far East (the Primorsky and Khabarovsk regions), while no YEZV was detected among 952 samples from Western Siberia (Altai Republic (n = 79), Kemerovo region (n = 289), Novosibirsk region (n = 107), Tomsk region (n = 340) and Tyumen region (n = 137)) [

10]. We found that the set of oligonucleotides used in the above study contains single-nucleotide mismatches, which may result in reduced sensitivity or even complete failure of PCR detection of the genetic variant of the YEZV genetic variant that we identified. Another significant finding was the detection of the virus in the ixodid tick

I. pavlovskyi, while previous study from Russia had reported detections exclusively in

I. persulcatus (

I. persulcatus and

I. ricinus was studied). Previously published data from other countries has shown that various other ixodid tick species, including

D. silvarum,

H. megaspinosa,

H. japonica,

I. ovatus and

I. persulcatus, can carry this virus [

10,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

As a result of metagenomic sequencing, we obtained the complete sequences of all three genome segments of the virus; its high quality allowed for detailed genomic characterization. Specifically, the L segment encodes an RdRp and includes an OTU-like protease domain and a polymerase module consisting of pre-motif A and motifs A-E and four conserved regions I-IV. The M segment encodes a GPC that consists of two subunits, Gn and Gc. In addition, the GPC contains an N-terminal signal peptide with its cleavage site, O- and N-glycosylation rich regions, a pair of conserved zinc finger domains, and conserved fusion loop regions — bc, cd, and ij loops. The S segment encodes a nucleoprotein, which consists of two domains: a globular head and a stem. All of the above structural components of the three genome segments of the YEZV are integral parts of the genomes of other representatives of the genus

Orthonairovirus [

10,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54].

Analysis of nucleotide and amino acid sequence identity showed that our identified YEZV is similar to previously published sequences of isolates. However, the relatively high level of differences suggests that a new genetic variant of the virus has been discovered. The percentage of differences varied from 8.601% to 9.152% for the L segment; from 9.946% to 10.664% for the M segment, and from 7.659% to 8.672% for the S segment. At the protein level, the differences ranged from 1.041% to 1.498% for the RdRp, from 5.236% to 6.268% for the GPC, and from 2.8% to 3.586% for the nucleoprotein. These data confirm the pattern previously observed in the literature that the M segment accumulates the most mutations [

55]. The increased level of genetic variability in the M segment compared to the other two genome segments is likely due to its functional significance, which lies in encoding the glycoproteins located on the surface of the viral particle. Since these proteins are responsible for viral attachment and entry into the cell, they are subject to selective pressure from the host’s immune system and during adaptation to different host and vector species. This ensures the virus’s adaptability to new conditions.

Phylogenetic analysis based on the nucleotide sequences from all three genome segments and the amino acid sequence of the RdRp confirmed the affiliation of the new genetic variant within the YEZV clade. At the same time, on the phylograms for the nucleotide sequences of the L and S segments, this genetic variant forms a distinct, well-supported sister branch relative to other virus isolates, indicating its genetic distinctiveness. This may be related to the discovery of the virus in a different species of ixodid tick and its circulation in a geographically remote region. Meanwhile, for the M segment, the new genovariant shows a closer relationship with two Chinese isolates.

The discrepancies in the topology of the phylogenetic trees indicate differences in the evolutionary dynamics of individual virus genome segments, which are likely due to reassortment. The data on the nucleotide sequence identity of the new genovariant with other isolates support this hypothesis: the L segment is most similar to the sequence from the Khabarovsk region, the M segment to the isolate from Inner Mongolia, and the S segment to the isolate from the Primorsky region. A similar situation is observed when comparing the amino acid sequences of the proteins: the RdRp is most similar to the isolate from Jilin Province, the GPC to the isolate from Inner Mongolia, and the nucleoprotein to the isolate from Heilongjiang Province. Reassortment events have been previously described in the literature for other orthonairoviruses, such as Uzhun-Agach virus, CCHFV, and Paramushir virus [

56,

57,

58].

From an epidemiological perspective, it is important to note that

I. pavlovskyi is the predominant species of ixodid ticks in urban biotopes in Tomsk, exhibiting a high degree of ornithophilicity at all developmental stages [

11,

12]. The detection of a new genovariant of the YEZV in a pool of ticks of this species may be a consequence of a high level of contact with birds, whose migration can facilitate the cross-border transfer of pathogens. As the YEZV has been found in animals and ixodid ticks in Japan and China [

10,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], it is possible that it is also circulating among vertebrates in Western Siberia, although there is currently no data to confirm this.

Thus, our findings expand knowledge of the virus and its vectors’ geographic distribution, genome size and structural organization, and highlight the need for further epidemiological surveillance of the pathogen. Future research should focus on expanding the collection sites, development of the RT-PCR oligonucleotides to detect new and known variants, assessing the prevalence of the virus among other species of ixodid tick that are important for the epidemiology of Western Siberia and among vertebrate animals, in order to establish the virus’s host range.

5. Conclusions

Due to its clinical manifestations, the YEZV poses a significant threat to public health. In this study, we report for the first time the detection of YEZV in Western Siberia, substantially expanding its geographical range. Our discovery also represents the first documented case of the virus in the tick I. pavlovskyi, thereby extending the range of its potential vectors. Using metagenomic sequencing, we obtained and characterized the complete sequences of the three YEZV genome segments. Our analysis revealed that the isolate represents a novel genetic variant, as demonstrated by sequence identity results and phylogenetic analysis. The highest number of mutations was found in the M segment, indicating its key role in adapting to new hosts and vectors. Differences in the topology of the phylogenetic tree for all three segments suggest the possibility of reassortment. This highlights the complex evolutionary dynamics of the virus and explains its genetic diversity. Our data expand the knowledge of the virus’s distribution and its vectors, emphasizing the importance of further epidemiological surveillance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Viruses and GenBank accession numbers of nucleotide (nt) and amino acid (aa) sequences of YEZV and nucleic acid sequences of SULV isolates used in phylogenetic and other comparative analyses; Table S2: Viruses and GenBank accession numbers of amino acid sequences of RdRp of members of the Orhonairovirus used in phylogenetic analyses; Figure S3: Amino acid sequence alignment of the conserved regions of NSD viruses and YEZV isolates; Figure S4: Amino acid sequence alignment of the Gns and Gcs of NSD genogroup viruses and YEZV isolates; Figure S5: Amino acid sequence alignment of the nucleoproteins of NSD genogroup viruses and YEZV isolates; Figure S6: Pairwise nucleic acid identity matrix of YEZV isolates; Figure S7: Pairwise amino acid identity matrix of YEZV isolates.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A., N.D. and K.S.; methodology, M.A., N.D., A.K.; software, M.A. N.D. and A.K.; validation, M.A. and N.D.; formal analysis, M.A. and N.D.; investigation, M.A., N.D., A.D., A.K. and A.T.; resources, A.K., G.A., E.D., A.S. and K.S.; data curation, M.A., A.K. and N.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.; writing—review and editing, M.A., N.D., A.D. and K.S.; visualization, M.A. and N.D.; supervision, A.K., G.A. and K.S.; project administration, K.S.; funding acquisition, A.S. and K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was partially supported by the following sources: RSF project 23-64-00005, state-funded budget project 225020408196-1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Partial genome sequences of YEZV from I. pavlovskyi were deposited in GenBank (PX219864, PX219865, PX219866). Raw sequencing reads are available under accession number SRR35181648.

Acknowledgments

Construction of the phylogenetic trees was carried out using sequences deposited in GenBank. We are grateful to the GenBank database (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ accessed on 8 July 2025) and to the authors who provided sequence information. We are grateful to the reviewers for their significant assistance in working on the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| YEZV |

Yezo virus |

| TBEV |

Tick-borne encephalitis virus |

| ssRNA(–) |

Single-stranded negative-sense RNA |

| SULV |

Sulina virus |

| RdRp |

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase |

| GPC |

Glycoprotein precursor complex |

| CCHFV |

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus |

| NSD |

Nairobi sheep disease |

References

- Latif, A. A.; Putterill, J. F.; De Klerk, D. G.; Pienaar, R.; Mans, B. J. Nuttalliella Namaqua (Ixodoidea: Nuttalliellidae): First description of the male, immature stages and re-description of the female. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, M.; Sajid, M. S.; Saqib, M.; Anjum, F. R.; Tayyab, M. H.; Rizwan, H. M.; Rashid, M. I.; Rashid, I.; Iqbal, A.; Siddique, R. M.; et al. Potential mechanisms of transmission of tick-borne viruses at the virus-tick interface. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 846884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskvitina, N. S.; Romanenko, V. N.; Ternovoi, V. A.; Ivanova, N. V.; Protopopova, E. V.; Kravchenko, L. B.; Kononova, Yu. V.; Kuranova, V. N.; Chausov, E. A.; Moskvitin, S. S.; et al. Detection of the West Nile virus and its genetic typing in ixodid ticks (Parasitiformes: Ixodidae) in Tomsk city and its suburbs. Parazitologiya 2008, 42, 210–225. [Google Scholar]

- Kuranova, V. N.; Yartsev, V. V.; Kononova, Yu. V.; Protopopova, E. V.; Konovalova, S. N.; Ternovoi, V. A.; Tavkina, I. S.; Romanenko, V. N.; Loktev, V. B.; Moskvitina, N. S. Lacertids (Sauria, Lacertidae) in natural foci of infectious human-transmitted ecosystems of the south-east territories of Western Siberia. In Proceedings of the 4th Meeting of the Nikolsky Herpetological Society, Kazan, Russia, 12–17 October2009; Russian collection: Saint-Petersburg, Russia, 2009; pp. 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Vilibić-Čavlek, T.; Bogdanić, M.; Savić, V.; Barbić, L.; Stevanović, V.; Kaić, B. Tick-borne human diseases around the globe, 7th ed.; Global Health Press: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Romanenko, V. N. The Peculiarities of the biology of ticks inhabiting the environs of Tomsk city. Parazitologiya 2005, 39, 365–370. [Google Scholar]

- Korobitsyn, I. G.; Moskvitina, N. S.; Tyutenkov, O. Yu.; Gashkov, S. I.; Kononova, Y. V.; Moskvitin, S. S.; Romanenko, V. N.; Mikryukova, T. P.; Protopopova, E. V.; Kartashov, M. Yu.; et al. Detection of tick-borne pathogens in wild birds and their ticks in Western Siberia and high level of their mismatch. FOLIA PARASIT 2021, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronkova, O. V.; Romanenko, V. N.; Simakova, A. V.; Esimova, I. E.; D’yakov, D. A.; Motlokhova, E. A.; Chernyshov, N. A.; Yamaletdinova, D. M. Analysis of multiple infection in ixodid ticks Dermacentor reticulatus in a combined natural focus of vector-borne infections in the Tomsk region. Problemy Osobo Opasnykh Infektsii 2023, No. 2, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tupota, N. L.; Ternovoi, V. A.; Ponomareva, E. P.; Bayandin, R. B.; Shvalov, A. N.; Malyshev, B. S.; Tregubchak, T. V.; Bauer, T. V.; Protopopova, E. V.; Petrova, N. K.; et al. Detection of the genetic material of the viruses Tacheng uukuvirus and Sara tick phlebovirus in taiga ticks collected in the Sverdlovsk, Tomsk regions and Primorsky territory of Russia and their phylogeny. Problemy Osobo Opasnykh Infektsii 2023, No. 3, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartashov, M.; Svirin, K.; Zheleznova, A.; Yanshin, A.; Radchenko, N.; Kurushina, V.; Tregubchak, T.; Maksimenko, L.; Sivay, M.; Ternovoi, V.; et al. A. first report of the Yezo virus isolates detection in Russia. Viruses 2025, 17, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanenko, V. N. Long-term dynamics of density and diversity of ticks (Ixodidae) on the natural and disturbed territories. Parazitologiya 2011, 45, 384–391. [Google Scholar]

- Moskvitina, N. S.; Korobitsyn, I. G.; Tyuten’kov, O. Yu.; Gashkov, S. I.; Kononova, Yu. V.; Moskvitin, S. S.; Romanenko, V. N.; Mikryukova, T. P.; Protopopova, E. V.; Kartashov, M. Yu.; et al. The role of birds in the maintenance of tick-borne infections in the Tomsk anthropurgic foci. Biol Bull Russ Acad Sci 2014, 41, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, F.; Yamaguchi, H.; Park, E.; Tatemoto, K.; Sashika, M.; Nakao, R.; Terauchi, Y.; Mizuma, K.; Orba, Y.; Kariwa, H.; et al. A novel nairovirus associated with acute febrile illness in Hokkaido, Japan. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, L.; Xu, W.; Yuan, Y.; Liang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wei, Z.; Sui, L.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Yezo virus infection in tick-bitten patient and ticks, Northeastern China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 797–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.-B.; Cui, X.-M.; Liu, J.-Y.; Ye, R.-Z.; Wu, Y.-Q.; Jiang, J.-F.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Q.; Shum, M. H.-H.; Chang, Q.-C.; et al. Metavirome of 31 tick species provides a compendium of 1,801 RNA virus genomes. Nat Microbiol 2023, 8, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Priyanshu, P.; Sharma, R. K.; Sharma, D.; Arora, M.; Gaidhane, A. M.; Zahiruddin, Q. S.; Rustagi, S.; Mawejje, E.; Satapathy, P. Climate change and its role in the emergence of new tick-borne Yezo virus. New Microbes and New Infections 2024, 60–61, 101423. [CrossRef]

- Nishino, A.; Tatemoto, K.; Ishijima, K.; Inoue, Y.; Park, E.; Yamamoto, T.; Taira, M.; Kuroda, Y.; Virhuez-Mendoza, M.; Harada, M.; et al. Transboundary movement of Yezo virus via ticks on migratory birds, Japan, 2020–2021. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, Y.; Sato, T.; Kato, K.; Kikuchi, K.; Mitsuhashi, K.; Watari, K.; Tamiya, K.; Goto, A.; Yamaguchi, H.; Hisada, R. A Case of tick-borne Yezo virus infection: Concurrent detection in the patient and tick. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2024, 143, 107038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Suzuki, S.; Yamaguchi, H.; Kakinoki, Y. Tick-borne disease with Yezo virus and Borrelia miyamotoi coinfection. Intern. Med. 2024, 63, 2861–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, K. Endemic area of emerging tick-borne Yezo virus infections discovered in China. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2025, 25, 359–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, J. H.; Alkhovsky, S. V.; Avšič-Županc, T.; Bergeron, É.; Burt, F.; Ergünay, K.; Garrison, A. R.; Marklewitz, M.; Mirazimi, A.; Papa, A.; et al. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Nairoviridae 2024: This Article Is Part of the ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profiles Collection. Journal of General Virology 2024, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, J.; Wiley, M.; Rodriguez, S.; Bào, Y.; Prieto, K.; Travassos Da Rosa, A.; Guzman, H.; Savji, N.; Ladner, J.; Tesh, R.; et al. Genomic characterization of the genus Nairovirus (family Bunyaviridae). Viruses 2016, 8, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spengler, J. R.; Estrada-Peña, A.; Garrison, A. R.; Schmaljohn, C.; Spiropoulou, C. F.; Bergeron, É.; Bente, D. A. A Chronological review of experimental infection studies of the role of wild animals and livestock in the maintenance and transmission of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus. Antiviral Research 2016, 135, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X. Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of infectious diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1458316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandegrift, K. J.; Kapoor, A. The ecology of new constituents of the tick virome and their relevance to public health. Viruses 2019, 11, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippova, N. A. Ixodid ticks of the subfamily Ixodinae; 4th ed.; Strelkov A. A., Eds.; Nauka: Leningrad, USSR, 1977; 396 p. (In Russian).

- Conceição-Neto, N.; Yinda, K. C.; Van Ranst, M.; Matthijnssens, J. NetoVIR: modular approach to customize sample preparation procedures for viral metagenomics; Moya, A., Pérez Brocal, V., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2018; Vol. 1838, pp. 85–95. ISBN 978-1-4939-8682-8. [Google Scholar]

- De Coninck, L.; Faye, L.; Basler, N.; Jansen, D.; Van Espen, L. ViPER, version 2.3.1; Zenodo: Geneve, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, A. M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurk, S.; Meleshko, D.; Korobeynikov, A.; Pevzner, P. A. metaSPAdes: A new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 824–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchfink, B.; Xie, C.; Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods 2015, 12, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondov, B. D.; Bergman, N. H.; Phillippy, A. M. Interactive metagenomic visualization in a web browser. BMC Bioinformatics 2011, 12, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasimuddin, Md.; Misra, S.; Li, H.; Aluru, S. Efficient architecture-aware acceleration of BWA-MEM for multicore systems. In 2019 IEEE international parallel and distributed processing symposium (IPDPS); IEEE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, E. ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Research 2003, 31, 3784–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Binns, D.; Chang, H.-Y.; Fraser, M.; Li, W.; McAnulla, C.; McWilliam, H.; Maslen, J.; Mitchell, A.; Nuka, G.; et al. InterProScan 5: Genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallgren, J.; Tsirigos, K. D.; Pedersen, M. D.; Almagro Armenteros, J. J.; Marcatili, P.; Nielsen, H.; Krogh, A.; Winther, O. DeepTMHMM predicts alpha and beta transmembrane proteins using deep neural networks. Bioinformatics , Bioinformatics April 10, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Duckert, P.; Brunak, S.; Blom, N. Prediction of proprotein convertase cleavage sites. Protein Engineering, Design and Selection 2004, 17, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teufel, F.; Almagro Armenteros, J. J.; Johansen, A. R.; Gíslason, M. H.; Pihl, S. I.; Tsirigos, K. D.; Winther, O.; Brunak, S.; Von Heijne, G.; Nielsen, H. SignalP 6. 0 Predicts all five types of signal peptides using protein language models. Nat Biotechnol 2022, 40, 1023–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Brunak, S. Prediction of glycosylation across the human proteome and the correlation to protein function. Pac Symp Biocomput 2002, 310–322. [Google Scholar]

- Steentoft, C.; Vakhrushev, S. Y.; Joshi, H. J.; Kong, Y.; Vester-Christensen, M. B.; Schjoldager, K. T.-B. G.; Lavrsen, K.; Dabelsteen, S.; Pedersen, N. B.; Marcos-Silva, L.; et al. Precision mapping of the human O-GalNAc glycoproteome through SimpleCell technology. EMBO J 2013, 32, 1478–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K. D. MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2019, 20, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.; Ly-Trong, N.; Ren, H.; Baños, H.; Roger, A.; Susko, E.; Bielow, C.; De Maio, N.; Goldman, N.; Hahn, M.; et al. IQ-TREE 3: Phylogenomic inference software using complex evolutionary models. Life Sciences , April 7, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B. Q.; Wong, T. K. F.; Von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L. S. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Smith, D. K.; Zhu, H.; Guan, Y.; Lam, T. T. ggtree : An r package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods Ecol Evol 2017, 8, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revell, L. J. Phytools: An R package for phylogenetic comparative biology (and other things). Methods Ecol Evol 2012, 3, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waskom, M. Seaborn: Statistical data visualization. JOSS 2021, 6, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honig, J. E.; Osborne, J. C.; Nichol, S. T. Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever virus genome L RNA segment and encoded protein. Virology 2004, 321, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, H.-Y.; Shao, J.-W.; Pei, M.-C.; Cao, C.; Huang, F.-Q.; Sun, M.-F. Genomic characterization and phylogenetic analysis of a novel Nairobi sheep disease genogroup Orthonairovirus from ticks, Southeastern China. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 977405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada, D. F.; De Guzman, R. N. Structural characterization of the Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus Gn tail provides insight into virus assembly. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011, 286, 21678–21686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Rao, G.; Li, Z.; Yin, J.; Chong, T.; Tian, K.; Fu, Y.; Cao, S. Cryo-EM structure of glycoprotein C from Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus. Virologica Sinica 2022, 37, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Dong, H.; Ma, C.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Mao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, T.; et al. Structural and functional diversity of Nairovirus-encoded nucleoproteins. J Virol 2015, 89, 11740–11749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyde, V. M.; Khristova, M. L.; Rollin, P. E.; Ksiazek, T. G.; Nichol, S. T. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus genomics and global diversity. J Virol 2006, 80, 8834–8842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al’khovskiĭ, S. V.; L’vov, D. K.; Shchelkanov, M. I.; Deriabin, P. G.; Shchetinin, A. M.; Samokhvalov, E. I.; Aristova, V. A.; Gitel’man, A. K.; Botikov, A. G. Genetic characterization of the Uzun-Agach virus (UZAV, Bunyaviridae, Nairovirus), isolated from bat Myotis blythii oxygnathus Monticelli, 1885 (Chiroptera; Vespertilionidae) in Kazakhstan. Vopr Virusol 2014, 59, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lukashev, A. N.; Klimentov, A. S.; Smirnova, S. E.; Dzagurova, T. K.; Drexler, J. F.; Gmyl, A. P. Phylogeography of Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever virus. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0166744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safonova, M. V.; Shchelkanov, M. Y.; Khafizov, K.; Matsvay, A. D.; Ayginin, A. A.; Dolgova, A. S.; Shchelkanov, E. M.; Pimkina, E. V.; Speranskaya, A. S.; Galkina, I. V.; et al. Sequencing and genetic characterization of two strains Paramushir virus obtained from the Tyuleniy Island in the Okhotsk Sea (2015). Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2019, 10, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).