1. Introduction

Tick–borne flaviviruses are widespread throughout the world and pose a serious medical problem, causing a significant number of infectious diseases among people [

1]. Among the tick–borne orthoflaviviruses found in Russia are the Powassan, Omsk hemorrhagic fever, and tick–borne encephalitis viruses [

2,

3,

4]. Despite the fairly large species diversity, the genome of all flaviviruses has a typical structure and is a non–segmented ss(+)RNA approximately 11 kb long, encoding one extended open reading frame, at the edges of which are 5’– and 3’–untranslated regions [

5,

6].

However, over the past decades, novel flavi–like viruses have been isolated that are distinguished by differ from the “classical” orthoflaviviruses by segmented genome and represent a separate Jingmenvirus group [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Such viruses have a segmented single–stranded RNA positive genome and only two genes have certain identity to the RNA dependent RNA polymerase (NS5) and helicase (NS3) of the “classical” orthoflaviviruses. This Jingmenvirus group includes the Alongshan virus (ALSV), Jingmen tick, Yanggou tick, Mogiana tick, Kindia tick viruses and a lot other joint to the group [

10,

11]. Now, these flavi–like viruses have been detected across Asia, Europe, South America, and Africa.

The genomes of segmented flavi–like viruses include four segments (typical for viruses isolated from ticks, bats, monkeys and humans) to five segments for mosquitoes [

11]. Segment 1 encodes the NS5–like nonstructural protein, which is similar to the NS5 orthoflaviviruses and segment 3 encodes NS3 polypeptide. The N–terminal domain of NS3 has protease activity, and the C–terminal domain functions as a helicase. The NS3 protein, along with NS5, plays a central role in virus replication. Proteinase activity is required for polyprotein processing, the helicase domain is involved in capping and viral synthesis RNA. To date, the structure of the NS3 protein in most unsegmented flaviviruses has been studied and high homology has been shown not only in structure but also in the mechanisms of ATP hydrolysis, recognition and unwinding of RNA. Structural proteins VP1, VP2 VP3 are encoded in segments 2 and 4 and have no known homologues either among the

Flaviviridae family or among other viruses known to date. Segment 2 in ALSV encodes putative glycoproteins VP1a and VP1b, as well as a small protein with three transmembrane domains, the function of which is unknown. Proteins VP2 (putative capsid protein) and VP3 (putative viral membrane protein) are encoded in segment 4 and have partially overlapping translation frames.

Also, additional genomic segments have been recently described for Jingmenvirus genome [

12]. Discovery of additional genomic segments reveals the fluidity of Jingmenvirus genome and possibility combinations of segments packaged in different virus particles. It may be an additional evidence that the multipartite virions are really exist.

Following the discovery of the first known flavi–like virus with segmented (multipartite) genomes in China and Brazil [

7,

8], ALSV circulation was detected in ticks and human in northeastern China (Inner Mongolia and Heilongjiang provinces) [

13,

14]. The subsequent studies detected ALSV RNA in

I. ricinus ticks in Finland, France, Serbia, Germany, and Switzerland [

11,

15,

16,

17,

18]. The ALSV has also shown detected in Russia [

19,

20,

21,

22]. The ALSV genetic material has been founded in

I. persulcatus,

I. ricinus,

Dermacentor reticulatus and

D. nuttalli ticks collected in the Kaliningrad, Ulyanovsk, and Chelyabinsk regions, as well as in the Karelia, Tatarstan, Gorny Altai and Tuva Republics of the Russia. The pathogenicity of multicomponent flavi–like viruses for domestic animals and humans has now been proven. However, this information is fragmentary and limited. It is possible that ALSV role in infectious pathology may be more significant than is commonly believed.

The aim of this study is to search and perform molecular genetic characterization complete genomes for novel ALSV isolates from ixodid ticks in different regions of the Russia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection and Processing of Ticks

In this study, 4458 individual samples of adult ticks of the species I. persulcatus (N=4122) and I. ricinus (N=336) were analyzed. Ticks were collected by flagging from vegetation in the 23 regions in 2024 at the summer period. The locations of tick collections and tick species are presented (Figure 1). Ticks were washed twice with 70% ethanol to remove external contaminants and external microflora, after which they were stored at a temperature of –80 °C until further studies. The species of ticks was established by morphological characteristics according to the identifier, followed by taxonomic verification of ALSV positive samples by determining the nucleotide sequence of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase gene.

2.2. Reverse–Transcriptase PCR (RT–PCR) and Sequencing of Amplified Products

Adult ticks were homogenized using the laboratory homogenizer TissueLyser II (QIAGEN, Germany) in 300 µl 0.9% saline solution. Viral RNA from 150 µl tick suspensions was isolated with ExtractRNA (Evrogen, Russia), according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Screening of the obtained samples for the presence of ALSV RNA was performed by RT–PCR using screening primers complementary to a fragment of segment 2: Miass_gly_3F TGGATCAGCTCACACCACAC and Miass_gly_3R TCACCGTCACAGTGGAATGG [

19]. PCR was performed on a T1000 amplifier (Bio–Rad) in 25 μl of the BioMaster RT–PCR–Standard reaction mixture (2×) (Biolabmix, Russia) containing 0.4 pM primers under the following conditions: polymerase activation at 95 ℃ for 5 minutes and then 38 cycles: 95 ℃ for 10 s, 53 ℃ for 20 s, 68 ℃ for 30 s. The amplification products (expected length 33 bp) were analyzed by electrophoresis in 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide at a concentration of 2 μg/ml and visualized in the UV spectrum using a transilluminator. To confirm the specificity of RNA detection, the ALSV PCR product was gel–purified and then sequenced in both directions on the ABI PRISM 3500 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) sequencer using ABI PRISM® BigDye™ Terminator v. 3.1

2.3. NGS Sequencing and NGS Data Analysis

To enrich the library for high–throughput sequencing, we used targeted PCR with a panel of primers for all 4 segments (Table 1). To perform targeted amplification of ALSV, the amplification method was optimized by experimentally choosing temperature regime and concentrations of the reaction mixture components. The concentration of purified PCR products was estimated by the fluorescence method on a Qubit 2.0 device (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sequencing was performed using the MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 for 600 cycles. Cutadapt (version 1.8.1) and SAMtools (version 0.1.18) were used to remove the Illumina adaptors and duplicate reads. The contigs were assembled de novo using the MIRA assembler with default parameters (version 4.9.6). High–throughput sequencing data were processed using a BLAST–based taxonomic read identification algorithm.

Table 1.

Panel of primers for targeted library enrichment sequences of different segments of the ALSV genome for NGS.

Table 1.

Panel of primers for targeted library enrichment sequences of different segments of the ALSV genome for NGS.

| Description |

Primers |

Sequences (5′–3′) |

Size (bp) |

| Segment 1 |

AL1_1F |

GCCATGATTGTCCTGATAGTG |

|

| AL1_1R |

GCCCTGTCCATCTTCATTTCC |

982 |

| AL1_2F |

AGGAAAGACAGATCACTCAC |

|

| AL1_2R |

GGACATCATGGACTTCTCCT |

1038 |

| AL1_3F |

AGAAGTCCATGATGTCCTCC |

|

| AL1_3R |

GTTCATCCAGTCCTTGTAGTTTCC |

840 |

| Segment 2 |

AL2_1F |

GTAACCTCCGTAGACTGTCCA |

|

| AL2_1R |

GTCCCTTCCGTTTGGTTGTG |

477 |

| AL2_2F |

CTTGCTACATCGGAATCATGCC |

|

| AL2_2R |

GATAAGCCCTCTCGATACCTC |

1091 |

| AL2_3F |

TGGTACGACTGGCTTTCGAG |

|

| AL2_3R |

ACTTGTTGTAGTCTGCAACCC |

1098 |

| Segment 3 |

AL3_1F |

TCGTCCAAGACTACTTAACAG |

|

| AL3_1R |

GTATCGCCTGTCCTCTATCC |

721 |

| AL3_2F |

TGCTGTCCATAGCAATCATACC |

|

| AL3_2R |

GTAGGACACGTCCTTTGCGA |

865 |

| AL3_3F |

GCAAAGGACGTGTCCTACGT |

|

| AL3_3R |

TTACCACTTGCTGGTCACAG |

1314 |

| Segment 4 |

AL4_1F |

ACTTTGATCTACATCCTCGCC |

|

| AL4_1R |

GTATCCAGCTCTTCCCTTCTC |

824 |

| AL4_2F |

GGAAGAGCTGGATACCGAACTG |

|

| AL4_2R |

TGCCAGATGTGTAGCTTCCC |

1274 |

| AL4_3F |

CAGCACTGGCGAAGATAACC |

|

| AL4_3R |

TGCCCTGATACCTCCTAGCA |

503 |

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

The nucleotide sequences of the genome–coding regions of each segment were aligned using ClustalW. Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using the maximum likelihood method and the Tamura–Nei model in MEGA 10/11 with 1000 bootstrap replications [

23,

24]. Percent identity of nucleotide and amino acid sequences of ALSV were computed in MEGA 10/11 programs using default settings.

2.5. Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

Nucleotide sequences determined in the study are available in the GenBank database under accession numbers: PP623704–PP623718 and PP942935–PP942941 for segment 1; PP623719–PP623733 and PP942942–PP942948 for segment 2; PP623734–PP623748 and PP942949–PP942955 for segment 3; PP623749–PP623763 and PP942956–PP942962 for segment 4.

2.6. Biosafety

Experiments with potential infectious material were carried out in accordance with the requirements of biosafety rules “Sanitary and Epidemiological Requirements for the Prevention of Infectious Diseases” N 3.3686–21 dated 01/28/2021

3. Results

3.1. Tick Collection and ALSV Detection

The study analyzed 4458 individual samples of adult ticks collected in 22 regions of Russia (

Figure 1, Table S1 and Table S2). Among them, 22 ticks were found to have ALSV positive by RT–PCR and the average infection rate of ticks was thus 0.5% (22/4458; 95% CI: 0.3–0.7). ALSV positive ticks was detected shown in the Transbaikal Territory, Irkutsk region, Tuva Republic, Khakassia Republic, Kemerovo region, Udmurt Republic, Vologda region (

Table S2). The highest infection rate was shown for Khakassia Republic (3.3%) and Kemerovo region (2.4%). The lowest infection rate was in the Vologda region (0.4%). In this study, all ticks in which ALSV positive was found belonged to the species

I. persulcatus. No positive samples were found among the

I. ricinus ticks studied from the Bryansk and Smolensk regions, although cases of detection of ALSV positive

I. ricinus ticks have been early recorded in Russia [

20].

3.2. Analysis of Genome Identity

When compared with other ALSV isolates found in China, the studied Russian isolates from the Asian part have a nucleotide sequence identity level of about 96.5% for segments 1,3,4 and 94.5% for segment 2. The corresponding figures for Russian isolates of the European clade are in the range of 90% for segments 1, 3, 4 and 91% for segment 2. The level of difference with the prototype isolate found in Finland from the I. ricinus tick is in 89–93% range.

The level of differences in nucleotide sequences between the studied genetic variants of ALSV is about 5% for segments 1 and 4 and about 4% for segments 2 and 3 (

Figure 2]. The level of differences in the deduced amino acid sequences for proteins encoded in segments 1, 2 and 3 (NS5, VP2, VP3, VP1a, VP1b, NS3) is about 1%. The highest level of differences is observed for the amino acid sequences of proteins VP2 and VP3 encoded in segment 4. The most conserved proteins are the non–structural proteins NS3 and NS5.

Heat maps of identity for nucleotide and amino acid sequences for early described and studied ALSV isolates also demonstrate the above-described difference between the compared sequences (

Figure 3, Figure 4). However, it is noteworthy that nucleotide substitutions characteristic of all segments does not always lead to pronounced amino acid substitutions. Moreover, the amino acid sequences of NS3 and VP2 have the greatest conservatism, and the variability is typical for the VP1a polypeptide.

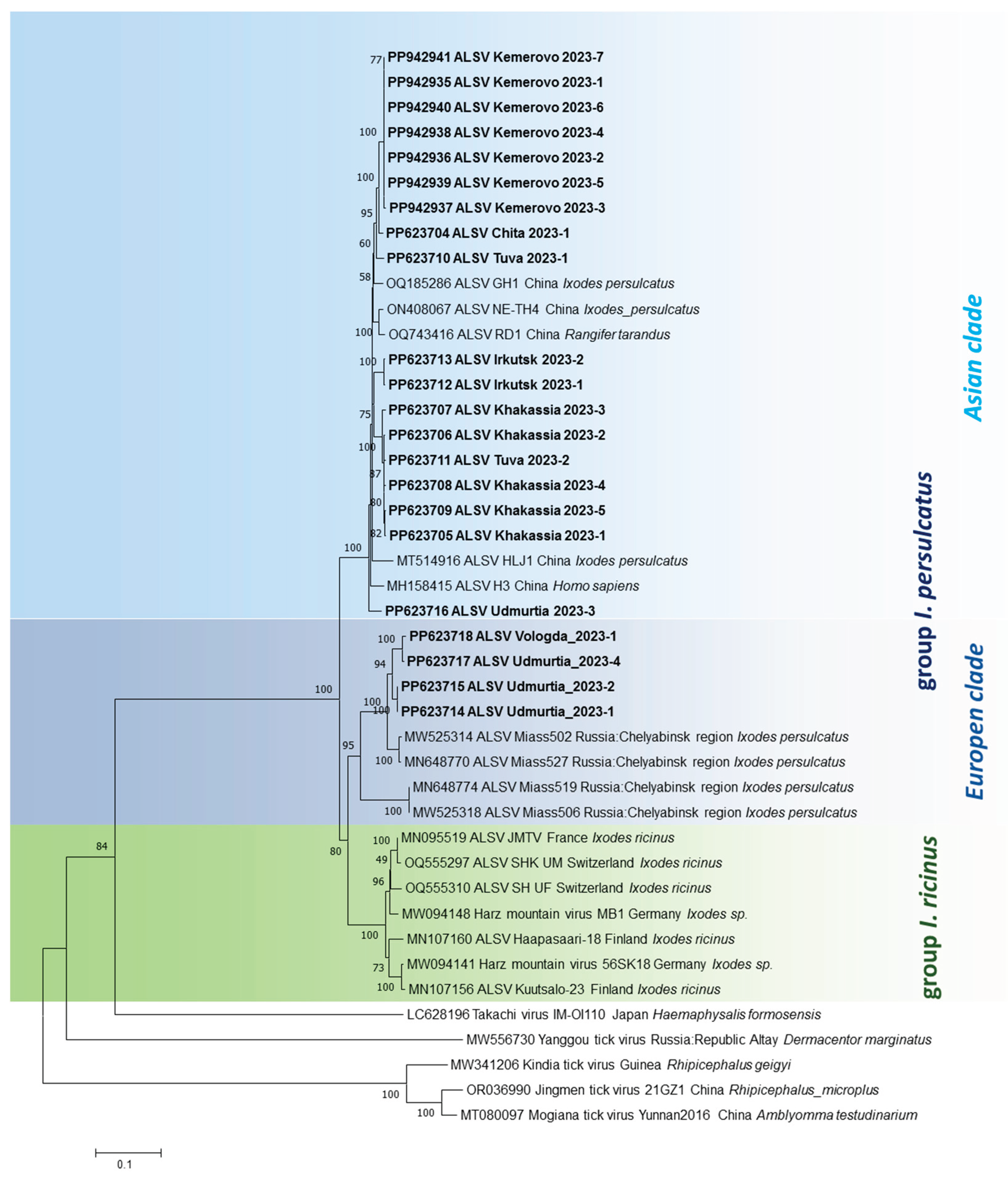

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

Phylogenetic trees demonstrate that genetic variants of ALSV circulating in

I. persulcatus ticks in the south of Eastern Siberia (Transbaikal Territory, Irkutsk region, Tuva Republic, Khakassia Republic) and Western Siberia (Kemerovo region) are grouped with sequences found in China in four segments (

Figure 5). This Asian subtype (clade) is represented by variants that form the Asian isolates found in

I. persulcatus ticks (or humans). Interestingly, this subtype (clade) also includes a single isolate from the Udmurt Republic (Europe), which is located on the border between the European and Asian parts of Russia.

Most of the ALSV variants from the Udmurt Republic, as well as the isolate from the Vologda Region, belong to separate clade within European subtype together with prototype variants from Chelyabinsk Region (Ural Mountains). These isolates were detected in I. persulcatus ticks. Another clade of European subtype is associated with I. ricinus ticks and Western European regions.

4. Discussion

The current epidemiological situation in Russia with regard to tick–borne infections is characterized not only by multiply incidence of already known tick–borne infections, but also detection a novel tick–borne pathogens such as ALSV. The ALSV was firstly isolated from the blood of patients with fever in northeastern China [

13,

14]. The viral RNA was detected in 86 of 384 patients with fever and patients with a history of tick bites. Patients infected with ALSV had a history of fever, headache, and other symptoms that resemble the manifestations of other tick–borne infections. A closely related viruses such as Jingmen tick virus, Mogiana tick virus and Kindia tick virus had been also detected in primates in Uganda, cattle in Brazil and Guinea and patients with Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever in Kosovo and Russia [

8,

25,

26,

27,

30,

31].

The ALSV genome is represented by ssRNA of positive polarity and consists of four segments [

13,

14]. Recently, the two novel putative structural proteins in the duplicated segments have been also described [

12]. This result highlights the fluid nature of Jingmenviruses genomes and their multipartite virions. Different combinations of segments packaged in different virus particles could facilitate the acquisition or loss of genomic segments and a segment duplication following genomic drift. Comparison of the nucleotide sequences of genes revealed high intraspecific variability at the level of 4.6 - 7.7%. Amino acid sequences have a higher conservatism at the level of 0.5% to 1.9%. The NS5 and NS3 flavi-like proteins encoded by segment 1 and 3 respectively are a most conserved polypeptide. The exceptions are the structural glycoproteins VP1a and VP1b, in which the amino acid variability reaches 7.5% and 4.5%, respectively. The increased variability of the putative structural viral proteins may be due to the pressure of the host immune response or the need for the ALSV to adapt different hosts. Probably, the accumulation of point substitutions in these proteins provides ALSV with the ability to replicate in various hosts and different natural foci. Analysis complete nucleotide sequences of four segments of the ALSV genome were shown that the identity level nucleotide sequences (4–6%) for Asian isolates are closer with ALSV isolates previously found in China. The European ALSV isolates has a more differences that proposed an independent evolution for ALSV in different geographical regions of the Eurasia.

Phylogenetic analysis for four genome segments of the ALSV was shown that ALSV isolates may be divided to Asian and European subtypes (

Figure 5). The Asian subtype is closely related to isolates first isolated in China in the area of the Russian–Chinese border [

13,

14] and these isolates are associated with novel ALSV variants found in the south of Eastern and Western Siberia in this study. All these isolates were found in

I. persulcatus ticks, only. The ALSV isolates of the European genotype are associated with ticks of two species:

I. persulcatus and

I. ricinus [

19,

20,

21]. These isolates form a two separate phylogenetic branches (subclades). They can be conditionally divided into Western European and Eastern European (including isolates collected in the Ural Mountains) groups of the ALSV. These may be predicted that the ecosystems of the south of Eastern Siberia and the north of Mongolia are optimal for the circulation ALSV infection [

13,

28]. Moreover, the vast territory of the south of Eastern Siberia borders is territorially close to the interior regions of China, where the circulation of ALSV was firstly detected [

14,

29].

Early, ALSV isolates were divided into the

I. ricinus and

I. persulcatus groups according to the main vector species. The

I. persulcatus group is divided into two subgroups: European (the Karelia and Altai Republics, Chelyabinsk Region) and Asian (China, the Altai, Tuva and Karelia Republics, Chelyabinsk and Ulyanovsk Regions and Altai Krai) [

19,

20,

21]. This assumption was confirmed in the present study. All ALSV isolates circulating in the south of Eastern Siberia and in Western Siberia in

I. persulcatus ticks were clearly clustered into the Asian subgroup of the corresponding vector when analyzed for each of the genome segments. Of interest is the territory of the Udmurt Republic, where most ALSV variants are characterized by clustering into the European branch, but an iso-late attributed to the Asian branch is also encountered.

Today, Russia tends to form persistent foci of tick–borne infections in urban and suburban areas [

5,

31,

32,

33]. Ticks inhabiting city parks and squares are especially dangerous, since city dwellers perceive the urban environment as free of ticks and do not take any non–specific preventive measures, unlike visiting natural biotopes. In our work, a number of places where ticks with RNA ALSV were detected can be classified as biotopes with a high anthropogenic load and located within rural settlements (for example, in the Vologda region, Udmurtia, Kemerovo region) or along busy highways, as in the Irkutsk region. Some of the places where ticks with RNA ALSV were detected in Udmurtia are located near a children’s country camp.

5. Conclusions

The study shows the wide distribution of the ALSV in the Russia. The highest-level viral detection was shown for Asian part of Russia and ALSV genetic markers were associated with I. persulcatus ticks. Analysis complete nucleotide sequences of four segments of the viral genome were shown that the high identity level nucleotide sequences for Asian isolates are closer with ALSV isolates previously found in China. The highest level of differences is observed for the VP2 and VP3 polypeptides (segment 4). NS5 and NS3 flavi-like proteins encoded by segment 1 and 3 respectively are a most conserved polypeptide. This information together with phylogenetic analysis for four genome segments of the ALSV are propose the existence of Asian and European subtypes (clades) for the ALSV may be associated with I. persulcatus and I. ricinus tick, respectively.

These data actualize the need to detect changes in the boundaries of the spread of the modern ALSV isolates and other flavi–like viruses that a potentially dangerous to humans which will allow predicting the transmission for these tick–borne infections.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Characteristics of the studied tick samples and the number of PCR–detected ALSV positive ticks; Table S2: List of the collection sites for ALSV positive ticks detected by RT PCR.

Author Contributions

M.Y.K., K.A.S., M.E.A., A.S.Z., V.Y.K., V.A.T., and V.B.L., designed the experiments and analyzed the data; M.Y.K., K.A.S., M.E.A., A.S.Z., V.Y.K., performed the experiments; A.P.A., V.A.T., project administration and funding acquisition, M.Y.K., and V.B.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This research was carried out with the support of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation, agreement No. 075-15-2025-526

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The ALSV genomes are published in GenBank with accession codes: PP623704–PP623763 and PP942935–PP942962.

Acknowledgments

We thank for help to organizing and collecting Ixodes ticks our colleagues from the Hygiene and Epidemiology Centers located in Altai Republic, Arkhangelsk region, Bryansk region, Irkutsk region, Ivanovo region, Kemerovo region, Khabarovsk Krai, Khakassia Republic, Kirov region, Komi Republic, Krasnoyarsk region, Mari El Republic, Novosibirsk region, Primorsky Krai, Smolensk region, Tomsk region, Transbaikal Territory, Tver region, Tyumen region, Tuva Republic, Udmurt Republic, Vologda region. We also thank anonymous reviewer for helpful comments on the earlier version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pierson, T.C. , Diamond, M. S. The continued threat of emerging flaviviruses. Nat Microbiol. 2020, 5, 796–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonova, G.N., Kondratov, I.G., Ternovoi, V.A., Romanova, E.V., Protopopova, E.V., Chausov, E.V., Pavlenko, E.V., Ryabchikova, E.I., Belikov, S.I., Loktev, V.B. Characterization of Powassan viruses from Far Eastern Russia. Arch Virol. 2009, 154(5), 811-820. [CrossRef]

- Ruzek, D. , Avšič Županc, T., Borde, J., Chrdle, A., Eyer, L., Karganova, G., Kholodilov, I., Knap, N., Kozlovskaya, L., Matveev, A., et al. Tick–borne encephalitis in Europe and Russia: Review of pathogenesis, clinical features, therapy, and vaccines. Antiviral Res. 2019, 164, 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyulko, Z.S., Fadeev, A.V., Vasilenko, A.G., Gradoboeva, E.A., Yakimenko, V.V., Komissarov, A.B. Analysis of changes in the genome of the Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus (Flaviviridae: Orthoflavivirus) during laboratory practices for virus preservation, Problems of Virology (Voprosy Virusologii). 2024, 69(6), 509–523. [CrossRef]

- Ternovoi, V.A. Ternovoi, V.A., Gladysheva, A.V., Ponomareva, E.P., Mikryukova, T.P., Protopopova, E.V., Shvalov, A.N., Konovalova, S.N., Chausov, E.V., Loktev, V.B. Variability in the 3’ untranslated regions of the genomes of the different tick–borne encephalitis virus subtypes. Virus Genes. 2019, 55, 448–457. [CrossRef]

- Postler, T.S., Beer, M., Blitvich, B.J., Bukh, J., de Lamballerie, X., Drexler, J.F., Imrie, A., Kapoor, A., Karganova, G.G., Lemey, P., et al. Renaming of the genus Flavivirus to Orthoflavivirus and extension of binomial species names within the family Flaviviridae. Arch Virol. 2023, 168, 224. [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.C.; Shi, M.; Tian, J.H.; Lin, X.D.; Gao, D.Y.; He, J.R.; Wang, J.B.; Li, C.X.; Kang, Y.J.; Yu, B.; et al. A tick–borne segmented RNA virus contains genome segments derived from unsegmented viral ancestors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014, 111, 6744–6749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villa, E.C., Maruyama, S.R., de Miranda–Santos, I.K.F., Palacios, G., Ladner, J.T. Complete Coding Genome Sequence for Mogiana Tick Virus, a Jingmenvirus Isolated from Ticks in Brazil. Genome Announc. 2017, 5, e00232–17. [CrossRef]

- Colmant, A.M.G. , Charrel, R.N., Coutard, B. Jingmenviruses: Ubiq–uitous, understudied, segmented flavi–like viruses. Front. Microbiol. 9970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogola, E.O. , Roy, A., Wollenberg, K., Ochwoto, M., Bloom, M.E. Strange relatives: the enigmatic arbo–jingmenviruses and orthoflaviviruses. npj Viruses 2025, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temmam, S., Bigot, T., Chrétien, D., Gondard, M., Pérot, P., Pommelet, V., Dufour, E., Petres, S., Devillers, E., Hoem, T., et al. Insights into the host range, genetic diversity, and geographical distribution of Jingmenviruses. mSphere. 2019; 4, e00645–19. [CrossRef]

- Valle, C., Parry, R.H., Coutard, B., Colmant, A.M.G. Discovery of additional genomic segments reveals the fluidity of jingmenvirus genomic organization. Virus Evolution, 2025, 11, veaf023. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.D.; Wang, B.; Wei, F.; Han, S.Z.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Z.T.; Yan, Y.; Lv, X.L.; Li, L.; Wang, S.C.; et al. A New Segmented Virus Associated with Human Febrile Illness in China. N Engl J Med. 2019, 380, 2116–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.D., Wang, W., Wang, N.N., Qiu, K., Zhang, X., Tana. G., Liu, Q., Zhu, X.Q. Prevalence of the emerging novel Alongshan virus infection in sheep and cattle in Inner Mongolia, northeastern China. Parasit Vectors. 2019, 12, 450. [CrossRef]

- Kuivanen, S., Levanov, L., Kareinen, L., Sironen, T., Jääskeläinen, A.J., Plyusnin, I., Zakham, F., Emmerich, P., Schmidt–Chanasit, J., Hepojoki, J., Smura, T., Vapalahti, O. Detection of novel tick–borne pathogen, Alongshan virus, in Ixodes ricinus ticks, south–eastern Finland, 2019. Euro Surveill. 2019, 24, 1900394. [CrossRef]

- Stanojević, M., Li, K., Stamenković, G., Ilić, B., Paunović, M., Pešić, B., Maslovara, I.Đ., Šiljić, M., Ćirković, V., Zhang,.Y. Depicting the RNA virome of hematophagous arthropods from Belgrade, Serbia. Viruses. 2020, 12, 975. [CrossRef]

- Ebert, C.L., Söder, L., Kubinski, M., Glanz, J., Gregersen, E., Dümmer, K., Grund, D., Wöhler, A.S., Könenkamp, L., Liebig, K., et al. Detection and characterization of Alongshan virus in ticks and tick saliva from Lower Saxony, Germany with serological evidence for viral transmission to game and domestic animals. Microorganisms. 2023, 11, 543. [CrossRef]

- Stegmüller, S. , Fraefel, C., Kubacki, J. Genome Sequence of Alongshan virus from Ixodes ricinus ticks collected in Switzerland. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2023, 12, e0128722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kholodilov, I.S. , Litov, A.G., Klimentov, A.S., Belova, O.A., Polienko, A.E., Nikitin, N.A., Shchetinin, A.M., Ivannikova, A.Y., Bell–Sakyi, L., Yakovlev, A.S., et al. Isolation and characterisation of Alongshan virus in Russia. Viruses. 2020, 12, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholodilov, I.S., Belova, O.A., Morozkin, E.S., Litov, A.G., Ivannikova, A.Y., Makenov, M.T., Shchetinin, A.M., Aibulatov, S.V., Bazarova, G.K., Bell–Sakyi, L., et al. Geographical and tick–dependent distribution of flavi–like Alongshan and Yanggou tick viruses in Russia. Viruses. 2021, 13, 458. [CrossRef]

- Kholodilov, I.S., Belova, O.A., Ivannikova, A.Y., Gadzhikurbanov, M.N., Makenov, M.T., Yakovlev, A.S., Polienko, A.E., Dereventsova, A.V., Litov, A.G., Gmyl, L.V., et al. Distribution and characterisation of tick–borne flavi–, flavi–like, and phenuiviruses in the Chelyabinsk Region of Russia. Viruses. 2022, 14, 2699. [CrossRef]

- Kartashov, M.Yu., Krivosheina, E.I., Kurushina, V.Yu., Moshkin, A.B., Khankhareev, S.S., Biche–ool, C.R., Pelevina, O.N., Popov, N.V., Bogomazova, O.L., Ternovoi, V.A. Prevalence and genetic diversity of the Alongshan virus (Flaviviridae) circulating in ticks in the south of Eastern Siberia. Problems of Virology (Voprosy Virusologii). 2024, 69(2), 151–161. (in Russian). [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Nei, M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1993, 10, 512–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladner, J.T. , Wiley, M.R., Beitzel, B., Auguste, A.J., Dupuis, A.P., Lindquist, M.E., Sibley, S.D., Kota, K.P., Fetterer, D., Eastwood, G., et al. A Multicomponent Animal Virus Isolated from Mosquitoes. Cell Host Microbe. 2016, 20(3), 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, W.M., Fumagalli, M.J., Torres Carrasco, A.O., Romeiro, M.F., Modha, S., Seki, M.C., Gheller, J.M., Daffre, S., Nunes, M.R.T., Murcia, P.R., et al. Viral diversity of Rhipicephalus microplus parasitizing cattle in southern Brazil. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 16315. [CrossRef]

- Emmerich, P. , Jakupi, X., von Possel, R., Berisha, L., Halili, B., Günther, S., Cadar, D., Ahmeti, S., Schmidt–Chanasit, J. Viral metagenomics, genetic and evolutionary characteristics of Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever orthonairovirus in humans, Kosovo. Infect. Genet. Evol, 65. [CrossRef]

- Su, S., Cui, M.Y., Xing, L.L, Gao, R.J., Mu, L., Hong, M., Guo, Q.Q., Ren, H., Yu, J.F., Si, X.Y., Eerde, M. Metatranscriptomic analysis reveals the diversity of RNA viruses in ticks in Inner Mongolia, China. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2024, 18, e0012706. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W., Wang, W., Li, L., Li, N., Liu, Z., Che, L., Wang, G., Zhang, K., Feng, X., Wang, W.J., et al. Alongshan Virus Infection in Rangifer tarandus Reindeer, Northeastern China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024, 30, 1434–1437. [CrossRef]

- Kartashov, M.Y., Krivosheina, E.I., Naidenova, E.V., Zakharov, K.S., Shvalov, A.N., Boumbaly, S., Ternovoi, V.A., Loktev, V.B. Simultaneous Detection and Genome Analysis of the Kindia Tick Virus in Cattle and Rhipicephalus Ticks in the Republic of Guinea. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2025, 25(7), 470–475. [CrossRef]

- Ternovoi, V.A., Gladysheva, A.V., Sementsova, A.O., Zaykovskaya, A.V., Volynkina, A.S., Kotenev, E.S., Agafonov, A.P., Loktev, V.B. Detection of the RNA for new multicomponent virus in patients with Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in southern Russia. Annals of the Russian academy of medical sciences. 2020, 75(2):129-134. (in Russian). [CrossRef]

- Korobitsyn, I.G., Moskvitina, N.S., Tyutenkov, O.Y., Gashkov, S.I., Kononova, Y.V., Moskvitin, S.S., Romanenko, V.N., Mikryukova, T.P., Protopopova, E.V., Kartashov, M.Y., et al. Detection of tick–borne pathogens in wild birds and their ticks in Western Siberia and high level of their mismatch. Folia Parasitol (Praha). 2021, 68: 024. [CrossRef]

- Kartashov, M.Y., Gladysheva, A.V., Shvalov, A.N., Tupota, N.L., Chernikova, A.A., Ternovoi, V.A., Loktev, V.B. Novel Flavi–like virus in ixodid ticks and patients in Russia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2023, 14(2). 102101. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).