1. Introduction

Today, sustainable materials alternatives to synthetic polymers derived from fossil resources have increasingly focused according to environmental impact [

1,

2,

3]. The new-generation is interested and concerning of environmentally friendly proposed worldwide. The natural biopolymers have been studied and applied since they are cost-effective functional materials, and environmental safety [

4,

5]. In addition, natural biopolymers are sustainable, biocompatible and biodegradable materials as well as their unique hierarchical structures further enhancing their appeal for a wild range of use [6-8]. Polysaccharide, such as cellulose [

9,

10,

11] , starch [

12], alginate [

13], chitosan [

14] and guar gum [

15] are also popularly discovered for applications. Another biopolymer, protein-based materials are regularly explored in different forms and applied in various fields [

16,

17,

18].

The natural silk fibers derived from silkworm cocoons has been used in textiles production according to its luster and mechanical strength [

19]. Silk fibroin (SF), which covered by a glue-like protein sericin (SE) are the main silk components [

20,

21]. In the degumming process, the later protein is usually discarded as waste, especially in the industrial production of silk fabrics [

22]. This relates to environmental problems [

19,

23]. Previous reports showed that different silk products have been developed for applications according its excellent biological and mechanical properties [

19,

23,

24].

In recent, SF is taken into consideration as SF-based devices for potential applications, especially in medical and drug delivery system [

24,

25,

26], because of its biodegradable and biocompatible characteristics [

27,

28]. SF microcarrier structures have been attractively developed [

24]. Because of their many benefits for drug delivery systems, SF hydrogels have drawn attention from all over the world [29, 30]. SF hydrogel has been used in a variety of ways in recent years [

31,

32,

33]. In addition to its structure, hydrogel properties like flexibility, plasticity, and permeability are frequently suggested.

Development of SF-based hydrogels are an attractive isuue of great significance to broaden their applications. In this work, SF aqueous solution was prepared from degummed. The prepared SF solution was blended with GG, SB and glycerol, then homogeneously stirred before pouring into the culture plates to construct the hydrogel. Afterward, the mixture solution was left to form gel for 3 days. The texture and appearance of the SF-based hydrogels were assessed following their separation from the plates. The degradation behavior of the prepared SF-based hydrogels in different media was examined. To further elucidate the effects of each blending substance on the produced SF-based hydrogels, hydrophilicity, strength, thermal stability, and conformational change were detailed and investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The cocoons of B. mori silk were received from the Silk Innovation Center at Mahasarakham University, located in the Khamriang sub-district of Kantharawichai, Maha Sarakham, Thailand. We obtained ethanol (C2H5OH), sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), and sodium chloride (NaCl) from Merck KGaA company (Darmstadt, Germany) and Ajax Finechem Pty Ltd. (Auckland, New Zealand). Before use, none of the reagent-grade chemicals used in this study required additional purification. Guar gum was purchased from commercial trade in Thailand. Sodium benzoate (C7H5O2Na) and glycerol (C3H8O3) were supplied from Merck KGaA company (Darmstadt, Germany)

2.2. Preparation of SF solution

The Thai silk B. mori cocoons were cleaned and cut into small pieces. They were then twice boiled for 30 minutes each at 100°C in a 0.5% (w/v) Na₂CO₃ solution to get rid of the glue-like protein. To obtain the SF, the degummed silk samples were rinsed with distilled water until the pH level was neutral. After that, a tertiary solvent system consisting of CaCl₂:C₂H₅OH:H₂O (1:2:8 by mol) was used to dissolve the degummed silk for 60 minutes at 75°C while stirring continuously. The hydrolysate SF was dialyzed against distilled water for three days to remove any salt using a dialysis membrane (MW cut off 10 kDa, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). After the SF solution's concentration was determined, distilled water was added to dilute it to 2% (w/v).

2.3. Preparation of SF-based Hydrogels

The 20 mL of SF solution was blended with different substances to find a favorite component, including various concentrations of guar gum (GG) (0.1–0.4 g) and C7H5O2Na (SB) (0.1–04 g). After mixing, all components were stirred until they received a homogeneous mixture and then poured in the polystyrene culture plates with a 9 cm diameter. All samples were left air-dried for several days at room temperature to obtain the hydrogel-based SF for further charcaterization.

2.4. Characteristics of SF-based Hydrogels

2.4.1. Transparency Observation.

As mentioned previously [

34], a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Lambda 25, Perkin Elmer, MA, USA) was used to measure the transparency of the SF-based hydrogels that were constructed. In short, rectangular pieces of the hydrogels were cut out and put straight into the spectrophotometer cell. The average transparency value was then determined by measuring the percentage transmittance of light at 660 nm through each hydrogel three times.

2.4.2. Analysis of Functional Groups.

Utilizing an attenuated reflection-Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectrometer (Perkin Elmer-Spectrum Gx, USA), the functional groups of the SF-based hydrogels were examined. The FTIR spectrum results were acquired with 32 scans and a wavenumber range of 4000–400 cm⁻¹ at a spectral resolution of 4 cm⁻¹. Air served as the reference for this procedure.

2.4.3. Thermal Stability.

The thermal stability of the constructed SF-based hydrogels was investigated using a thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA) (SDTQ600, TA-Instrument Co. Ltd., New Castle, DE, USA). The samples were placed within an aluminum pan before heating in the range of 50 to 800 °C by fixing a rate of 20 °C per minute. The condition of the process was performed in a nitrogen environment. The decreases in weight were recorded at several points in time.

2.4.4. Mechanical Properties.

Using the tensile testing machine and the ASTM D638 testing procedure, the mechanical characteristics of SF-based hydrogels were assessed. The samples were fixed to the machine using tensile grips after being cut into rectangular pieces measuring 200 mm by 50 mm. At room temperature, a testing speed of 2 mm/min was employed. A computer was used to monitor and control the process. The stress–strain curve was used to determine the tensile strength (MPa) and elongation at break. For each, three specimens were inspected for mechanical alterations.

2.4.5. Degradation of SF-based Hydrogels.

The degradation behavior of the SF-based hydrogels in different media (phosphate buffers with pH 7.4, 1M HCl, 1M NaOH, C

2H

5OH, and NaCl solution) were performed following the previous reported [

18] with modification. Firstly, the dry and clean glass vials were numbered and weighed the total mass of the glass vials. The SF-based hydrogels were added in the vials and weighed. The degradation experiment was conducted at 37°C in an incubator after the fresh degradation solution was added at a 1:1 (v/v) ratio to the glass vial containing the hydrogel. The new degradation solution was changed daily throughout the course of the experiments. The samples were removed and the degradation solution disposed of once the predetermined time had passed. Weighing was done to determine the combined mass of the glass vial and the leftover hydrogel. Equation (1) was used to determine the hydrogel's residual mass-retention rate.

where M0 represents the initial mass (g) of the glass vial and hydrogel, M is the glass vial's mass (g), and Mi is the mass (g) of the glass vial and any hydrogel that remains after i days.

2.4.6. Hydrophilicity Test.

The hyrophilicity of the SF -based hydrogel surfaces was determined utilizing a WCA analyzer (model OCA 11, DataPhysics Instruments GmbH, Filderstadt, Germany). The SF-based hydrogels were separated into 3 x 5 cm² rectangles and placed on a moving, horizontal platform that had been covered in black Teflon and had a WCA analyzer. A suitable droplet of water (5–10 μl) was applied to the hydrogel's surface using a microsyringe. The contact angle of the water droplet was measured. The averages of each sample's triplicate measurements were calculated for the results.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Appearance Features

3.1.1. GG-SF-based Hydrogels

SF mixed with different concentrations (0.1-0.4 g/ml) GG was prepared into hydrogels, as indicated in

Figure 1. The SF-based hydrogel mixed GG at 0.1 g/L (

Figure 1a) has a thin, smooth surface and is highly translucent, but it does not form a complete texture and cannot be peeled from the plate. When the amount of GG was increased to 0.2 g/ml (

Figure 1b), the hydrogel found clung together to form a sheet. The GG-SF-based hydrogels have a high moisture content and is fairly translucent. Though it is quite soft and folds easily, even the prepared hydrogel can be peeled off from the plate. When GG was added at a concentration of 0.3 g/ml, the GG-SF-based hydrogel, which has smoother surfaces and is more rigid, peeled off with ease (

Figure 1c). All things considered, this ratio works best for producing GG-SF-based hydrogel that can be used and transported. Although it is thicker and less transparent, the resulting SF-based hydrogel mixed GG at 0.4 g/ml (

Figure 1d) shares most of the same properties as the SF-based hydrogel with GG at 0.3 g/ml.

3.1.2. GG-SF-based Hydrogel mixed SB

As seen in

Figure 2, the SF-based hydrogel mixed GG at 0.3 g/ml was chosen for blending with various SB concentrations (0.1–0.4 g/ml) due to its best appearance. The hydrogel remains intact and does not detach from the plate when mixed with 0.1 g/ml SB (

Figure 2a). SB particles are dispersed throughout the hydrogel's surface. The blended hydrogel came together as a sheet when the SB concentration was raised to 0.2 g/ml (

Figure 2b), but it is thin and highly translucent. The resulting hydrogel is harder and more sticky when the amount of SB is increased to 0.3 g/ml (

Figure 2c). The surface of the prepared hydrogel was smooth and shiny, especially the side-contacted plate. As for the GG-SF-based hydrogel mixed with SB at 0.4 g/ml (

Figure 2d), the obtained hydrogel was generally similar to the hydrogel mixed at 0.3 g/ml but was thicker and had lower transparency. Overall, the GG-SF-based hydrogel mixed 0.2–0.4 g/ml SB resulted in suitable texture hydrogels for application.

3.2. Transparency and Degradation of the Hydrogel-based SF

When considering their practical application, transparency and water solubility are two crucial attributes to consider [35, 36]. The letters in

Figure 3 were covered in order to visually assess this macroscopic feature of the SF-based hydrogels. As GG-SF-based hydrogels, they have an overall appearance of being white, slightly glossy, and extremely transparent (

Figure 3b-d). The homogeneous glycerol-plasticized texture indicated that the glycerol was evenly distributed and contributed to the blending of the various molecules. The GG-SF-based hydrogel is less transparent and has less moisture than SB (

Figure 3e,f). As the concentration of SB increased, the transparency was decreased. The transparency of all prepared hydrogels is lower than that of the hydrogel-free sample (

Figure 3a).

All prepared SF-based hydrogels were tested for light transmittance (T660), which reflected the transparency of the hydrogels. As shown in

Table 1, the highest transmittance value found in hydrogel prepared from SF-mixed 0.2 g/ml GG of 65.30%, and then decreased gradually by increasing of GG contents. Conversely the lowest light transmittance value obtained from the hydrogel which prepared from GG-SF mixed 0.4 g/ml SB. These results can be noted that the hydrogel transparency gradually decreased when increased of both GG and SB contents. However, SB showed highly effect on the rigid texture of the hydrogels.

Table 1 shows remaining mass retention ratio of the hydrogels on various media. At the end of experiment (2 days), the GG-SF-based hydrogels had degradation about 50% in PBS buffer pH 7.4, but SB-GG-SF-based hydrogels have higher remaining mass retention rate value. GG is a hetero-polysaccharide which can be reacted to water molecules in the buffer while SB structure composed aromatic ring of benzoate, a sodium salt of benzoic acid. Benzoic acid is generally not used directly due to its poor water solubility. This is caused the hydrogel has dense texture and protected the water absorbed into the hydrogel. Sodium benzoate is usually act as a food preservative, and also used as a preservative in medicines and cosmetics. In acid condition, degradation value of the SF-based hydrogel was in higher than PBS buffer. Moreover, the SF-based hydrogel also dramatically degraded in NaOH solution with the lowest remained mass. This indicated that NaOH could be hydrolyzed the peptide bonds in SF and glycosidic bonds in GG as well as H-bonds between SF and GG. In ethanol, the prepared hydrogels had degraded, but the remaining mass retention rate is slight in higher value than in PBS buffer. The ethanol, an polar solvent, can formed hydrogen bonds with the hydrophilic groups of hydrogels. Therefore it could be penetrated into hydrogel network and quickly degraded the hydrogel texture. However, the SF-based hydrogel displayed a slight swelling texture in NaCl solution. This might be affected by the porous network structure of SF, which can absorb the water. A more stable crystal structure was also formed inside the hydrogel as a result of some salt ions entering it. As a result, the hydrogel's ability to absorb water is protected by its dense pores [

18,

37,

38]. Hydrophilicity test (

Table 2) indicated that GG and SF has interacted together via H-bonds formation, which decreased the hydrophilicity of the hydrogels. The WCA (EØ) values increased when the GG content was increased. In addition, adding SB resulted in WCA values, especially at 0.4 mg/ml. The increase in the WCA value indicates a decrease in the polarity of the hydrogel. Because the added sodium benzoate has a non-polar ring structure, we expect the sodium benzoate molecules to intercalate rather than directly bond with SF or GG.

3.3. Mechanical Properties of the Hydrogels

Mechanical properties of SF-based hydrogels were shown in

Table 3. The highest tensile strength (53.3 MPa), and Young’s modulus (226.3 MPa) found from SF-GG-SB (0.4) hydrogel, but elongation at break showed the lowest value (8.4%). However, the SF-GG (0.2) had the lowest tensile strength (32.9 MPa) and Young’s modulus (192.4 MPa). The SF-GG (0.3) hydrogel has the highest elongation at break of 27.0%. From the results, the tensile stress of the prepared hydrogels increased with the increase in both GG and SB contents. This indicated that the hydrogel-based SF formed with high GG and SB contents had higher mechanical properties. Adding SB reflected the rheological properties of the hydrogel since the SB structure is large from benzene ring. Therefore, increased SB content resulting in decreased elastic capacity of the hydrogels, which increased a higher mechanical strength.

3.3. Clarification of Functional Groups

ATR-FTIR spectra of hydrogel-based SF revealed their functional groups shown in

Figure 4. Significant functional groups of the SF (

Figure 4a) are considered seriously at the absorption location, which is amide I (-CO stretching) at 1636 cm

-1 , amide II (-NH stretching) at 1517 cm

-1, and amide III (-CN- stretching) at 1238 cm

-1 [

39]. The repeating units of polysaccharides contain many functional groups. Among their positive attributes are their biodegradability and biocompatibility. Drug delivery systems have made extensive use of GG, a naturally occurring heteropolysaccharide derived from seed gum [

40].

Figure 4b is a FTIR spectrum of GG, which revealed the light absorption peaks of -CH stretching at 3000 and 2800 cm

-1, ring stretching (1642 cm

-1), symmetrical deformations of CH

2 (1435 cm

-1), highly coupled CC-O, C-OH, and C-O-C stretching modes (800–1200 cm

-1), and galactose and mannose linkages (770–930 cm

-1) [

41,

42,

43]. The FTIR spectrum of GG-SF-based hydrogel is shown

Figure 4d. The absorption peak of hydroxyl group (-OH stretching) is dramatically wide at 3350 cm

-1. In general, the absorption peaks of the main components, SF and GG have dominant observation. However, the characteristic peaks of each material are sharp and clear. This means that the SF and GG are mixed and formed texture network via their functional groups [

44]. The FTIR spectrum of SB powder is shown in

Figure 4c. The main absorption peaks have appeared at 1404 cm

-1 for aromatic C=C stretching, 1546 and 1596 cm

-1 for C=O stretching [

45,

46]. The spectrum of SB-GG-SF-based hydrogel showed in

Figure 4e. It has also been found that all the main functional groups of SF, GG and SB have appeared. The results indicate that all of them are interacted which enhanced the strength of hydrogel.

3.4. Thermal Properties of Hydrogels

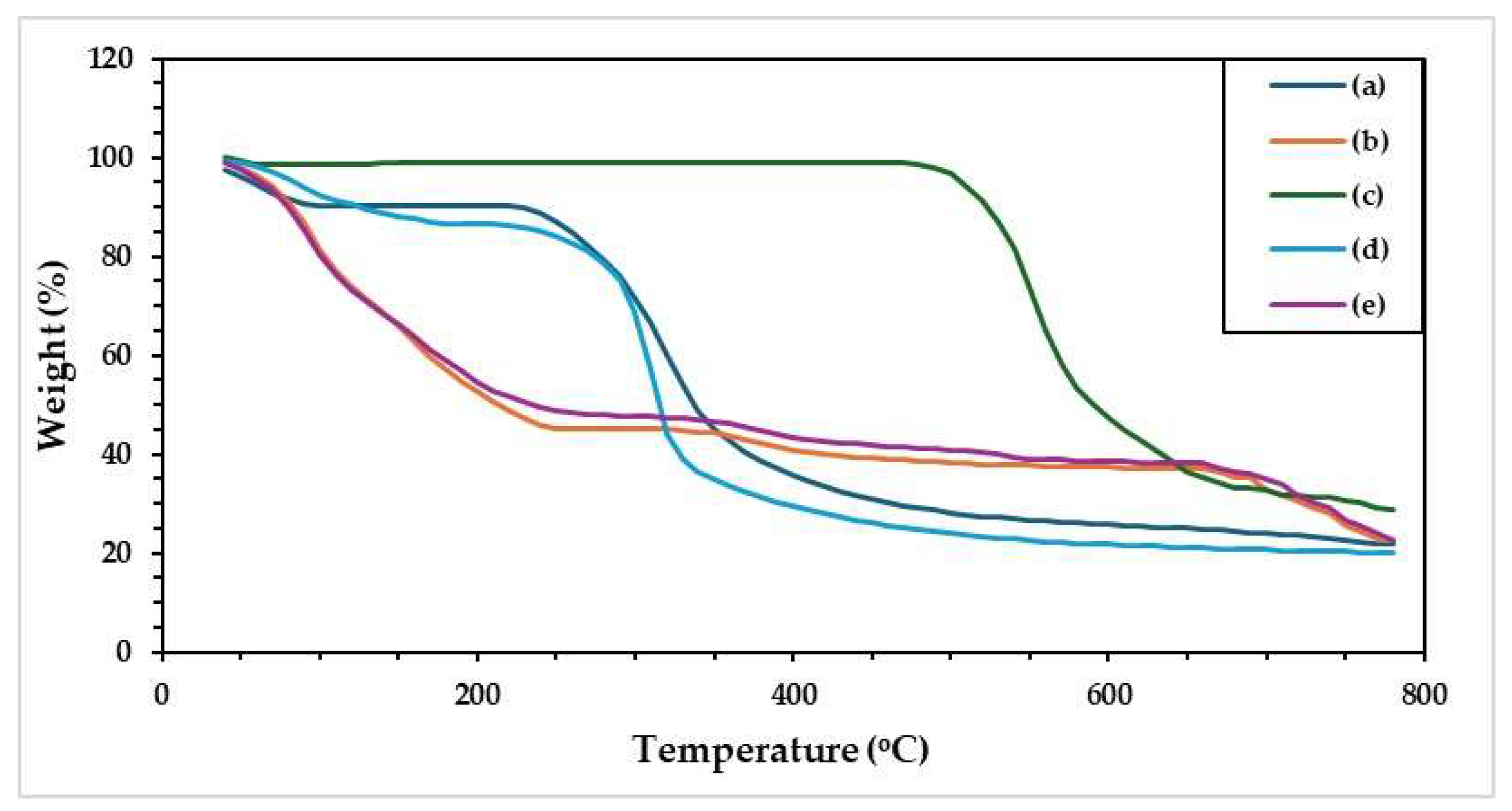

Thermal stability of all SF-based hydrogels was investigated by using a thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA).

Figure 5 showed TG thermograms of the prepared hydrogels. The results indicated different peaks of weight loss, which started by moisture losing at low temperatures (80–100 °C) [

47]. In addition, the decomposition peaks have been appeared atlease two regions at 150–230 °C and 300–400 °C. Among the hydrogels, weight loss was recorded at the initial stage for GG-SF, whereas no substantial loss was observed for the SB powder. The decomposition temperature of SB was observed after heating at 530 °C. At 800 °C, the remaining-charred of all prepared hydrogels have remained of about 20-30%, which GG has remained charred residue in lower weight than other.

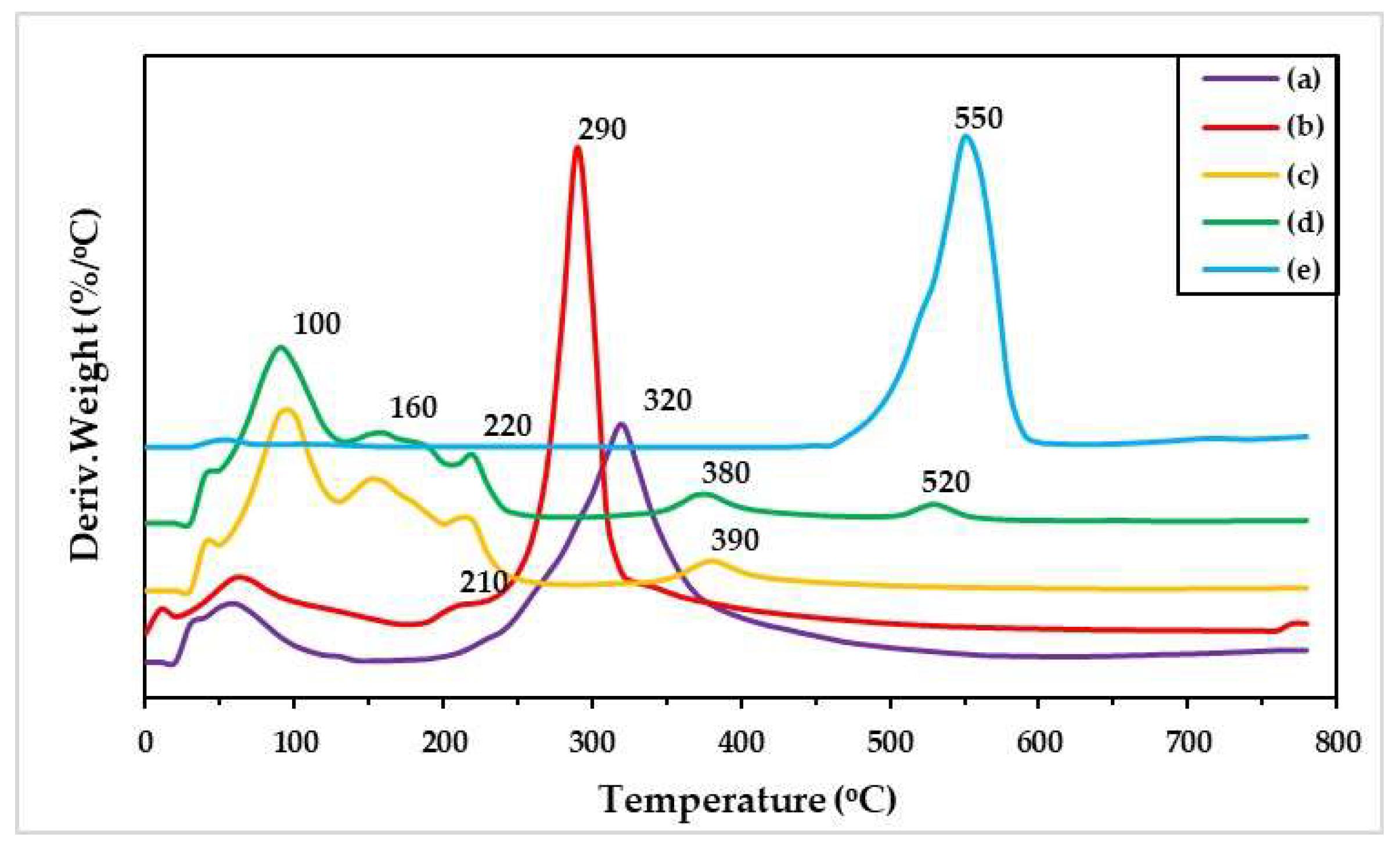

Figure 6 illustrates the DTG curves of different materials, which exhibited the maximum decomposition temperature (T

d, max). From DTG results, SF showed the T

d, max at approximately 323 °C, whereas SB revealed at 553 °C. GG has a T

d, max at 311 °C with a shoulder peak at 227 °C. SF blended GG and SB hydrogels found many peaks of T

d, max, especially at 375 °C. This peak shifted from 311 °C of GG and 323 °C of SF, which thought that some interactions between two materials would be formed and resulted to increase T

d, max. The result indicated that this interaction helped to increase thermal stability of the hydrogels [

48,

49]. Conversely, no interaction between SF and SB was observed since the T

d, max of the blended hydrogel was in lower value comparing with SB powder. In addition, the T

d, max at 216 °C was the decomposition temperature of glycerol [

50].

Table 4 summarized the effects of some parameters on the thermal behavior of all SF-based hydrogels.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, SF-based hydrogels were successfully prepared by simple evaporation technique. The outcomes of hydrogel demonstrated suitable characteristics for further applications such as ease of use, and economy of combining materials. The constructed SF-based hydrogels have moderate transparency and light transmittance, with some different appearances among GG and SB. In detail, SF and GG are homogeneously blended and formed interaction together via H-bonds which demonstrated by ATR-FTIR spectra. When SB was added into GG-SF, the hydrogels had increased of solid texture and found SB particles distributed in the hydrogel texture resulted to enhance both thermal stability and WCA value. This reason is affected by the ring structure of SB. This suggested that structure and functional groups of substances are impacted on the hydrogel properties. SF-based hydrogels showed high stability on various solvents, resulting in structural stability for application while could be environmentally degraded. Even further studies are still needed to confirm the practical use, our study shows that SF-based hydrogel might be used in specific applications including wound healing and tissue engineering.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T. and P.S.; methodology, S.T. and P.S.; investigation, S.T. and P.S.; resources, S.T.; visualization, Y.B. and P.S.; writing-original draft, A.T., P.S., and Y.B.; writing, reviewing, and editing, A.T., P.S., and Y.B. After reading the published version of the manuscript, all writers have given their approval.

Funding

This research project was financially supported by Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI). The Center of Excellence for Innovation in Chemistry (PERCH-CIC), Office of the Higher Education Commission, Ministry of Education, Thailand, for its partial funding is also appreciated by P.S.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts of interest are disclosed by the authors.

References

- Corcoran, P.L. ; Benthic Plastic Debris in Marine and Fresh Water Environments. Environ. Sci. Process Impacts 2015, 17, 1363–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Guo, S.; Kuang, X.; Wan, X.; Liu, L.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, G.; Cong, H.; He, H.; Tan, S.C. ; Recent Advancements and Perspectives on Processable Natural Biopolymers: Cellulose, Chitosan, Eggshell Membrane, and Silk Fibroin. Sci. Bull. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evode, N.; Qamar, S.A.; Bilal, M.; Barceló, D.; Iqbal, H.M.N. ; Plastic Waste and Its Management Strategies for Environmental Sustainability. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2021, 4, 100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.; Islam, S. ; Effectiveness of Waste Plastic Bottles as Construction Material in Rohingya Displacement Camps. Cleaner Eng. Technol. 2021, 3, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Khuntia, S.K. ; Development and Study of Properties of Moringa oleifera Fruit Fibers/Polyethylene Terephthalate Composites for Packaging Applications. Compos. Commun. 2019, 15, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.A.; Sohail, M.; Khan, S.; Minhas, M.U.; Matas, M.de; Sikstone, V.; Hussain, Z.; Abbasi, M.; Kousar, M. ; Biopolymer-Based Biomaterials for Accelerated Diabetic Wound Healing: A Critical Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 139, 975–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Lema, S.; Nilsson, K.; Trifol, J.; Langton, M.; Gomez-Caturla, J.; Balart, R.; Garcia-Garcia, D.; Morina, R. ; Faba Bean Protein Films Reinforced with Cellulose Nanocrystals as Edible Food Packaging Material. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 121, 107019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnacker, M.; Rieger, B. ; Recent Progress in Sustainable Polymers Obtained from Cyclic Terpenes: Synthesis, Properties, and Application Potential. Chem. Sus. Chem. 2015, 8, 2455–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Liu, L.; Zhang, L.; Lu, A. ; Strong Cellulose Hydrogel as Underwater Superoleophobic Coating for Efficient Oil/Water Separation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 229, 115467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonoobi, M.; Oladi, R.; Davoudpour, Y.; Oksman, K.; Dufresne, A.; Hamzeh, Y.; Davoodi, R. ; Different Preparation Methods and Properties of Nanostructured Cellulose from Various Natural Resources and Residues: a Review. Cellulose 2015, 22, 935–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Jeon, Y.; Kim, D.; Kwon, G.; Kim, U.-J.; Hong, C.; Choung, J.W.; You, J. ; Double-Crosslinked Cellulose Nanofiber-Based Bioplastic Films for Practical Applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 260, 117817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, Y.; Li, J.; Nie, M.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, L.; Wang, F.; Tong, L.-T. ; A Comprehensive Review of Starch-Based Technology for Encapsulation of Flavor: From Methods, Materials, and Release Mechanism to Applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 348, 122816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bialik-Wąs, K.; Kulawik-Pioro´, A.; Sienkiewicz, A.; Łętocha, A.; Osinska´, J.; Malarz, K.; Mrozek-Wilczkiewicz, A.; Barczewski, M.; Lanoue, A.; Giglioli-Guivarc’h, N.; Miastkowska, M. ; Design and Development of Multibiocomponent Hybrid Alginate Hydrogels and Lipid Nanodispersion as New Materials for Medical and Cosmetic Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Qiao, D.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, B.; Xie, F. ; Advanced Functional Chitosan-Based Nanocomposite Materials for Performance-Demanding Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2024, 157, 101872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharahi, M.; Bahrami, S.H.; Karimi, A. ; A Comprehensive Review on Guar Gum and Its Modified Biopolymers: Their Potential Applications in Tissue Engineering. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 347, 122739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Bairagi, S.; Ganie, S.A.; Ahmed, S. ; Polysaccharides and Proteins Based Bionanocomposites as Smart Packaging Materials: From Fabrication to Food Packaging Applications: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 252, 126534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Guo, Y.; Dong, A.; Yang, X. ; Protein-Based Emulsion Gels as Materials for Delivery of Bioactive Substances: Formation, Structures, Applications and Challenges. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 144, 108921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Ma, W.; Li, L.; Wang, Y. ; Protein-Based Grafting Modification in the Food Industry: Technology, Applications and Prospects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 153, 104751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, B.; Svanström, M.; Peters, G.; Rydberg, T. ; A Carbon Footprint of Textile Recycling: A Case Study in Sweden. J. Ind. Ecol. 2015, 19, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, G.H.; Diaz, F.; Calabro, C.T.J.; Horan, R.L.; Chen, J.; Lu, H.; Richmond, J.; Kaplan, D.L. ; Silk- Based Biomaterials. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Q. ; Applications of Natural Silk Protein Sericin in Biomaterials. Biotechnol. Adv. 2002, 20, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamoolphak, W.; De-Eknamkul, W.; Shotipruk, A. ; Hydrothermal Production and Characterization of Protein and Amino Acids from Silk Waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 7678–7685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Wei, J.; Zheng, L.J.; Zhao, Y.P. ; Extraction and Characterization of Silk Fibroin from Waste Silk. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 788, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sun, H.; Peng, Y.; Chen, L.; Xu, W.; Shao, R. ; Preparation and Characterization of Natural Silk FibroinHydrogel for Protein Drug Delivery. Molecules 2022, 27, 3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisuwan, Y.; Baimark, Y.; Srihanam, P. ; Preparation of Regenerated Silk Sericin/Silk Fibroin blend Microparticles by Emulsification Diffusion Method for Controlled Release Drug Delivery. Particul. Sci. Technol. 2017, 35, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.U.D.; Gautam, S.P.; Qadrie, Z.L.; Gangadharappa, H.V. ; Silk Fibroin as a Natural Polymeric based Biomaterial for Tissue Engineering and Drug Delivery Systems-A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 163, 2145–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinel, L.; Hofmann, S.; Karageorgiou, V.; Kirker-Head, C.; McCool, J.; Gronowicz, G.; Zichner, L.; Langer, R.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G.; Kaplan, D.L. ; The Inflammatory Responses to Silk Films in vitro and in vivo. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulescu, D.M.; Andronescu, E.; Vasile, O.R.; Ficai, A.; Vasile, B.S. ; Silk Fibroin-based Scaffolds for Wound Healing Applications with Metal Oxide Nanoparticles. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 96, 105689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, T.; Lovett, M.L.; Kaplan, D.L. ; Silk-Based Biomaterials for Sustained Drug Delivery. J. Control. Release 2014, 190, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.; Stok, K.S.; Kohler, T.; Meinel, A.J.; Müller, R. ; Effect of Sterilization on Structural and Material Properties of 3-D Silk Fibroin Scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.J. ; Bioinspired Conductive Cellulose Liquid-Crystal Hydrogels as Multifunctional Electrical Skins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 18310–18316. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.J.; Chu, T.S.; Chu, J.L.; Gao, B.B.; He, B.F. ; A Versatile Approach for Enzyme Immobilization Using Chemically Modified 3D-Printed Scaffolds. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 18048–18054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.T.; Das, M.; Xu, Y.D.; Si, X.H.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Z.H.; Chen, X.S. ; Leveraging Biomaterials for Cancer Immunotherapy: Targeting Pattern Recognition Receptors. Mater. Today Nano 2019, 5, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Xu, T.; Qu, R.; Yuan, J.; Cai, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. ; An Environmentally Friendly Deproteinization and Decolorization Method for Polysaccharides of Typha angustifolia Based on a Metal Ion-Chelating Resin Adsorption. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 134, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontard, N.; Guilbert, S.; CUQ, J.L.J.J.o.f.s. ; Water and Glycerol as Plasticizers Affect Mechanical and Water Vapor Barrier Properties of An Edible Wheat Gluten Film. J. Food. Sci. 1993, 58, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- özeren, H.D.; Wei, X.-F.; Nilsson, F.; Olsson, R.T.; Hedenqvist, M.S. ; Role of Hydrogen Bonding in Wheat Gluten Protein Systems Plasticized with Glycerol and Water. Polymer 2021, 232, 124149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Park, W.H. ; Chemically Cross-Linked Silk Fibroin Hydrogel with Enhanced Elastic Properties, Biodegradability, and Biocompatibility. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 2967–2978. [Google Scholar]

- Numata, K.; Ifuku, N.; Masunaga, H.; Hikima, T.; Sakai, T. Silk Resin with Hydrated Dual Chemical-Physical Cross-Links Achieves High Strength and Toughness. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 1937–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayana, S.; Nasrine, A.; Ahmed, M.G.; Sultana, R.; Gowda, B.H.J.; Surya, S.; Almuqbil, M.; Asdaq, S.M.B.; Alshehri, S.; Hussain, S.A. ; Potential Benefits of Using Chitosan and Silk Fibroin Topical Hydrogel for Managing Wound Healing and Coagulation. Saudi Pharm. J. 2023, 31, 642–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.; Sharma, S.K. ; Recent Advances in Guar Gum based Drug Delivery Systems and Their Administrative Routes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 181, 653–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrika, K.S.V.P.; Singh, A.; Rathore, A.; Kumar, A. ; Novel Cross Linked Guar Gum-g-Poly(Acrylate) Porous Superabsorbent Hydrogels: Characterization and Swelling Behaviour in Different Environments. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 149, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gihar, S.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, P. ; Facile Synthesis of Novel pH-Sensitive Grafted Guar Gum for Effective Removal of Mercury (II) Ions from Aqueous Solution. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2021, 2, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudgil, D.; Barak, S.; Khatkar, B.S. ; X-ray Diffraction, IR Spectroscopy and Thermal Characterization of Partially Hydrolyzed Guar Gum. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012, 50, 1035–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharahi, M.; Bahrami, S.H.; Karimi, A. ; A Comprehensive Review on Guar Gum and Its Modified Biopolymers: Their Potential Applications in Tissue Engineering. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 347, 122739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Bala, R.; Gondil, V.S.; Pandey, S.K.; Chhibber, S.; Jain, D.V.S.; Sharma, R.K.; Wangoo, N. Combating Food Pathogens Using Sodium Benzoate Functionalized Silver Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization and Antimicrobial Evaluation. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 8568–8575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, K.; Das, B.; Mondal, D.; Adhikari, A.; Rana, D.; Chattopadhyay, A.K.; Banerjee, R.; Mishrad, R.; Chattopadhyay, D. ; An Ex-Situ Approach to Fabricating Nanosilica Reinforced Polyacrylamide Grafted Guar Gum Nanocomposites as an Efficient Biomaterial for Transdermal Drug Delivery Application. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 9461–9471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanisood, S.; Baimark, Y. and Srihanam, P.; Preparation and Characterization of Cellulose/Silk Fibroin Composites Microparticles for Drug-Controlled Release Applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassoued, M.; Crispino, F.; Loranger, E. ; Design and Synthesis of Transparent and Flexible Nanofibrillated Cellulose Films to Replace Petroleum-Based Polymers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 254, 117411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabanpour, B.; Kazemi, M.; Ojagh, S.M.; Pourashouri, P. ; Bacterial Cellulose Nanofibers as Reinforce in Edible Fish Myofibrillar Protein Nanocomposite Films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 117, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khotsaeng, N.; Simchuer, W.; Imsombut, T.; Srihanam, P. Effect of Glycerol Concentrations on the Characteristics of Cellulose Films from Cattail (Typha angustifolia L.) Fowers. Polymers, 2023, 15, 4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Appearance of SF-based hydrogel mixed GG at different ratios: 0.1 (a), 0.2 (b), 0.3 (c), and 0.4 g/ml (d).

Figure 1.

Appearance of SF-based hydrogel mixed GG at different ratios: 0.1 (a), 0.2 (b), 0.3 (c), and 0.4 g/ml (d).

Figure 2.

Appearance of GG-SF-based hydrogels mixed SB at different concentrations: 0.1 (a), 0.2 (b), 0.3 (c), and 0.4 g/ml (d).

Figure 2.

Appearance of GG-SF-based hydrogels mixed SB at different concentrations: 0.1 (a), 0.2 (b), 0.3 (c), and 0.4 g/ml (d).

Figure 3.

Appearance of SF-based hydrogels mixed GG at 0.2 (b), 0.3 (c), 0.4 g/ml (d), and hydrogel-based SF/0.3 g/ml GG mixed SB at 0.3 (e), and 0.4 g/ml (d). The letter without hydrogel (a) as comparison.

Figure 3.

Appearance of SF-based hydrogels mixed GG at 0.2 (b), 0.3 (c), 0.4 g/ml (d), and hydrogel-based SF/0.3 g/ml GG mixed SB at 0.3 (e), and 0.4 g/ml (d). The letter without hydrogel (a) as comparison.

Figure 4.

ATR-FTIR spectra of different materials; SF (a), GG (b), SB powder (c), GG-SF-based hydrogel (d), and SB-GG SF-based hydrogel (e).

Figure 4.

ATR-FTIR spectra of different materials; SF (a), GG (b), SB powder (c), GG-SF-based hydrogel (d), and SB-GG SF-based hydrogel (e).

Figure 5.

TG thermograms of different materials; SF (a), GG (b), GG/SF-hydrogel (c), SB-GG-SF-hydrogel (e), and SB powder (f).

Figure 5.

TG thermograms of different materials; SF (a), GG (b), GG/SF-hydrogel (c), SB-GG-SF-hydrogel (e), and SB powder (f).

Figure 6.

DTG curves of of different materials; SF (a), GG (b), GG/SF-hydrogel (c), SB-GG-SF-hydrogel (e), and SB powder (f).

Figure 6.

DTG curves of of different materials; SF (a), GG (b), GG/SF-hydrogel (c), SB-GG-SF-hydrogel (e), and SB powder (f).

Table 1.

Light transmittance and degradation of hydrogels in different media.

Table 1.

Light transmittance and degradation of hydrogels in different media.

| Samples |

T660

(%) |

Remaining mass retention rate (%) (at 2 days) |

| PBS |

HCl |

NaOH |

Ethanol |

NaCL |

SF-GG (0.2)

SF-GG (0.3)

SF-GG (0.4) |

65.30 ± 1.42

60.22 ± 2.66 |

50

55 |

0

3 |

0

3 |

55

65 |

105

105 |

| 51.80 ± 1.71 |

65 |

5 |

5 |

75 |

105 |

SF-GG-SB (0.2)

SF-GG-SB (0.3)

SF-GG-SB (0.4) |

24.80 ± 2.05

10.60 ± 1.48 |

70

75 |

10

15 |

12

13 |

80

85 |

102

102 |

| 4.50 ± 2.64 |

80 |

20 |

15 |

90 |

102 |

Table 2.

Water contact angle (WCA) of the prepared SF-based hydrogels.

Table 2.

Water contact angle (WCA) of the prepared SF-based hydrogels.

| Samples |

Contact angle |

| WCA(EØ) |

WCA(EL) |

WCA(ER) |

| SF-GG (0.2) |

25.95 |

25.39 |

26.50 |

| SF-GG (0.3) |

37.67 |

38.24 |

37.10 |

| SF-GG (0.4) |

39.77 |

40.27 |

39.27 |

| SF-GG-SB (0.2) |

44.84 |

44.72 |

44.95 |

| SF-GG-SB (0.3) |

47.97 |

48.66 |

47.28 |

| SF-GG-SB (0.4) |

80.17 |

80.95 |

79.39 |

Table 3.

Mechanical properties of the prepared SF-based hydrogels.

Table 3.

Mechanical properties of the prepared SF-based hydrogels.

| Samples |

Force @ Peak

(N) |

Tensile Stress

(MPa) |

Elongation

@ Break (%) |

Young’s Modulus

(MPa) |

| SF-GG (0.2) |

150.6 |

32.9 |

24.7 |

192.4 |

| SF-GG (0.3) |

174.7 |

38.0 |

27.0 |

202.2 |

| SF-GG (0.4) |

186.1 |

40.8 |

18.5 |

215.8 |

| SF-GG-SB (0.2) |

205.7 |

46.4 |

12.3 |

219.7 |

| SF-GG-SB (0.3) |

207.4 |

48.1 |

10.8 |

221.5 |

| SF-GG-SB (0.4) |

215.5 |

53.3 |

8.4 |

226.3 |

Table 4.

Thermal behaviors of the SF-based hydrogels.

Table 4.

Thermal behaviors of the SF-based hydrogels.

| Hydrogels |

Onset of decomposition

(°C) |

Td, max

(°C) |

Charred Residue Weight at

800 °C (%) |

| SF |

95 |

323 |

22 |

| GG |

90 |

227, 311 |

20 |

| SB |

- |

553 |

22 |

| GG-SF |

90 |

152, 300, 375 |

22 |

| SB-GG-SF |

90 |

154, 375, 531 |

22 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).