Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

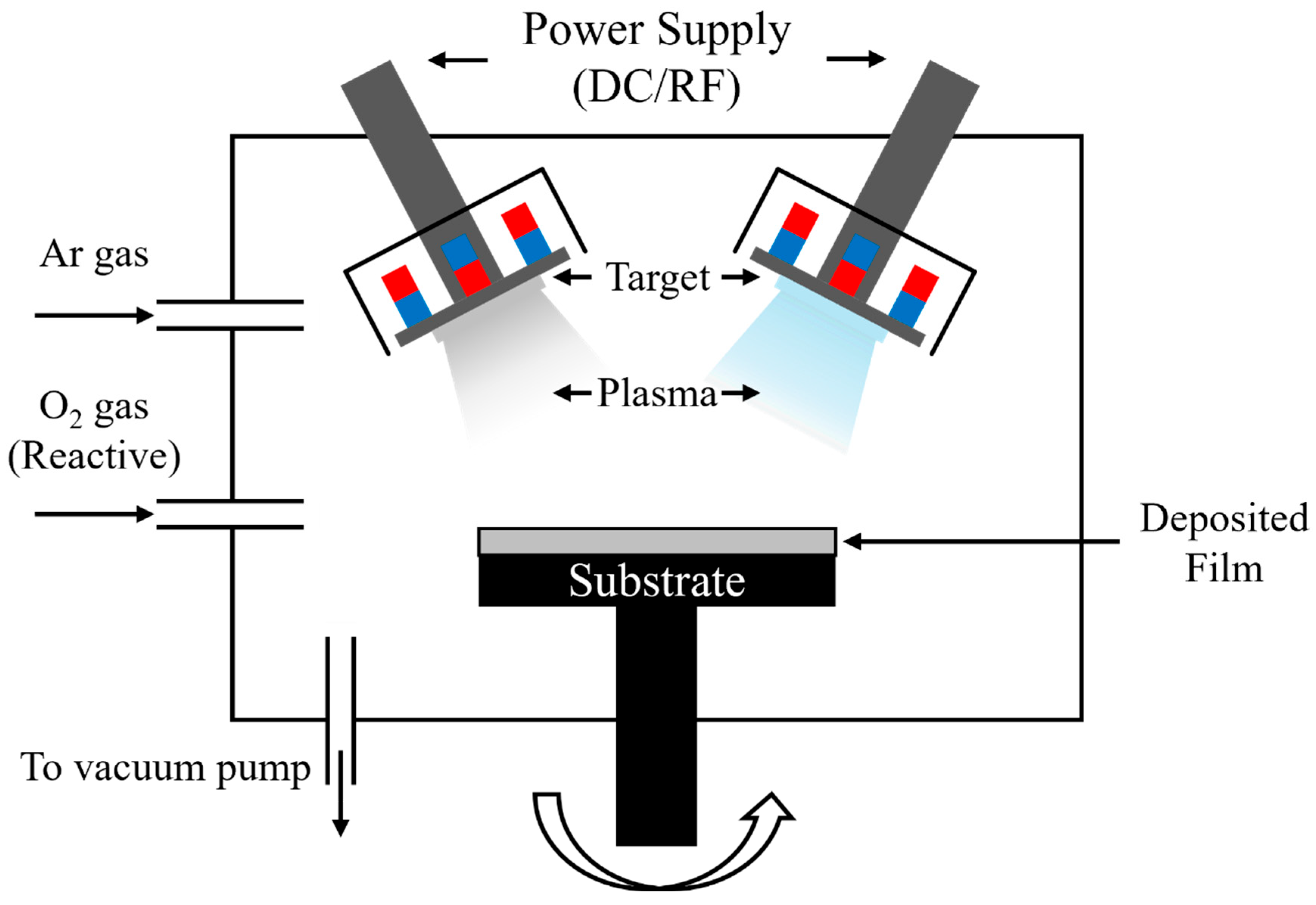

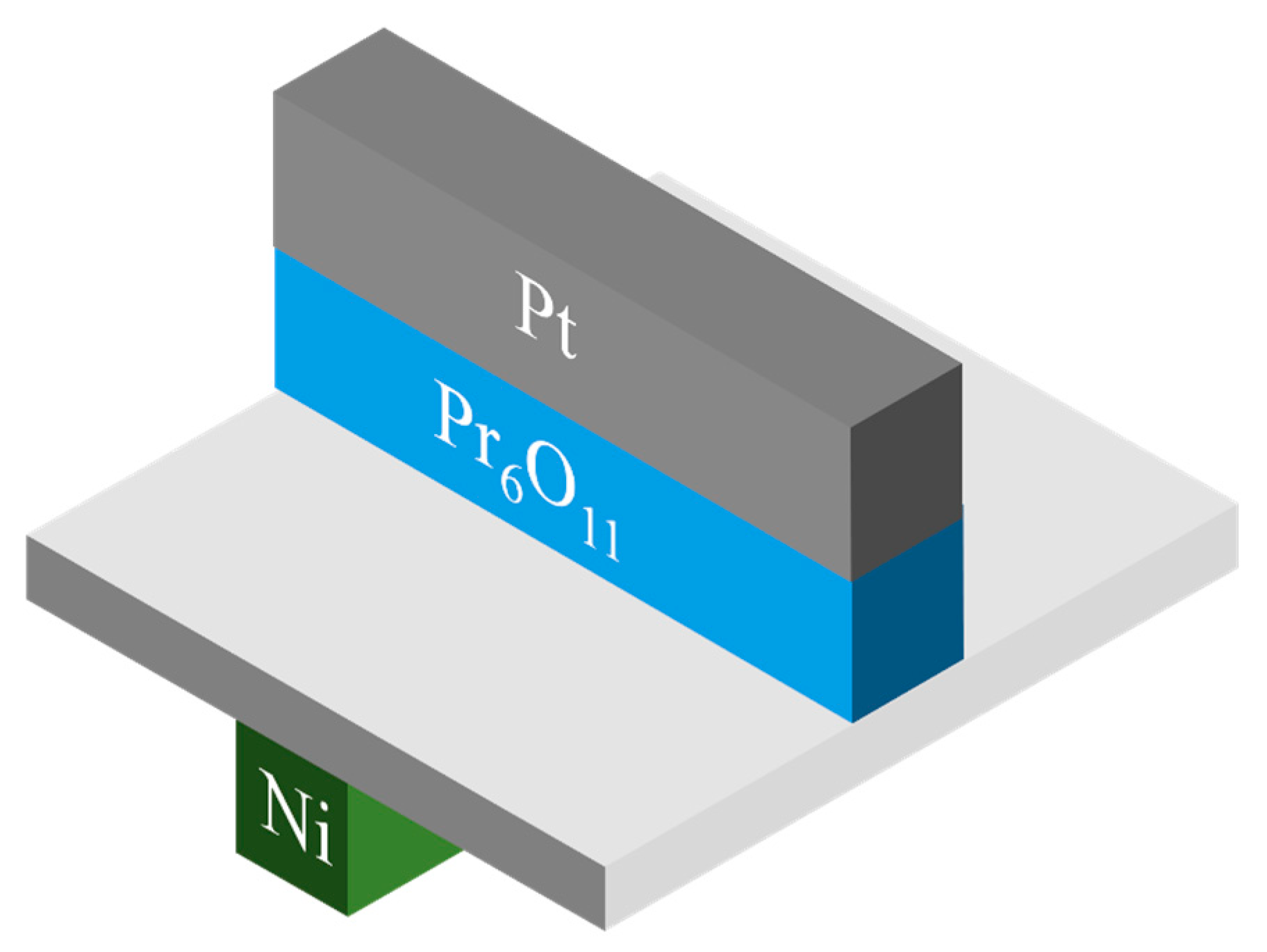

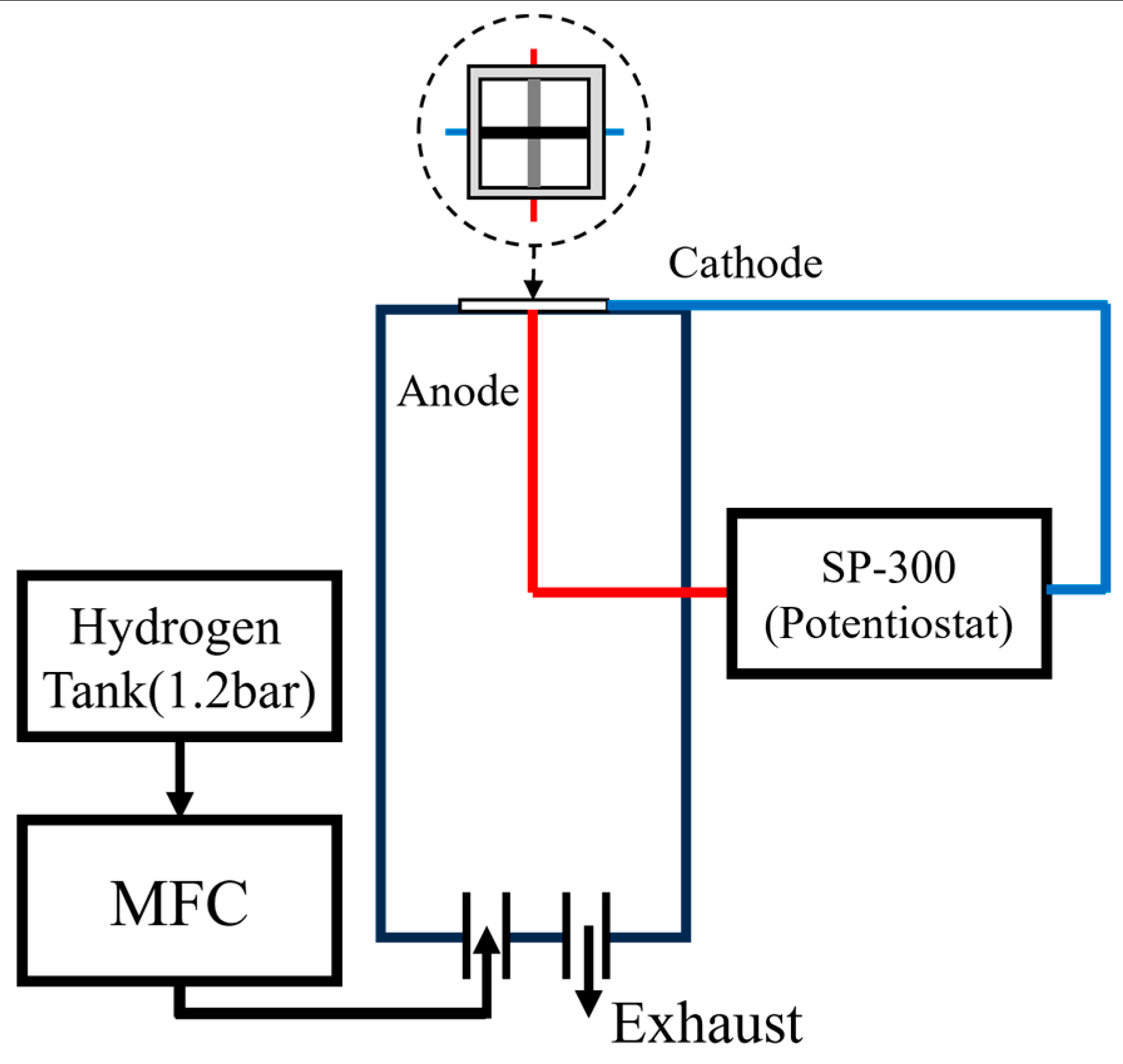

2. Experiments

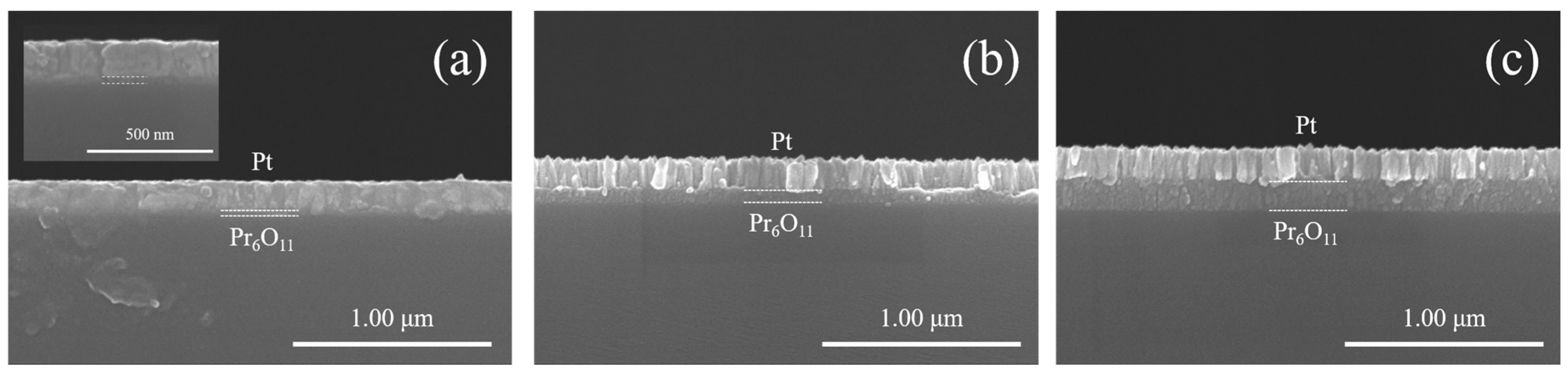

| Parameters | Pr30 | Pr55 | Pr150 |

| PrOx Thickness | 30nm | 55nm | 150nm |

| PrOx Power | 5mTorr, Ar 24sccm + O2 6sccm, RT, 40W | ||

| PrOx Deposition time | 1hr 7min | 2hr 15min | 4hr 30min |

| Cathode (Pt) | 50mTorr, Ar 30sccm, RT, 100W, 5min | ||

| Anode (Ni) | 30mTorr, Ar 30sccm, RT, 100W, 25min | ||

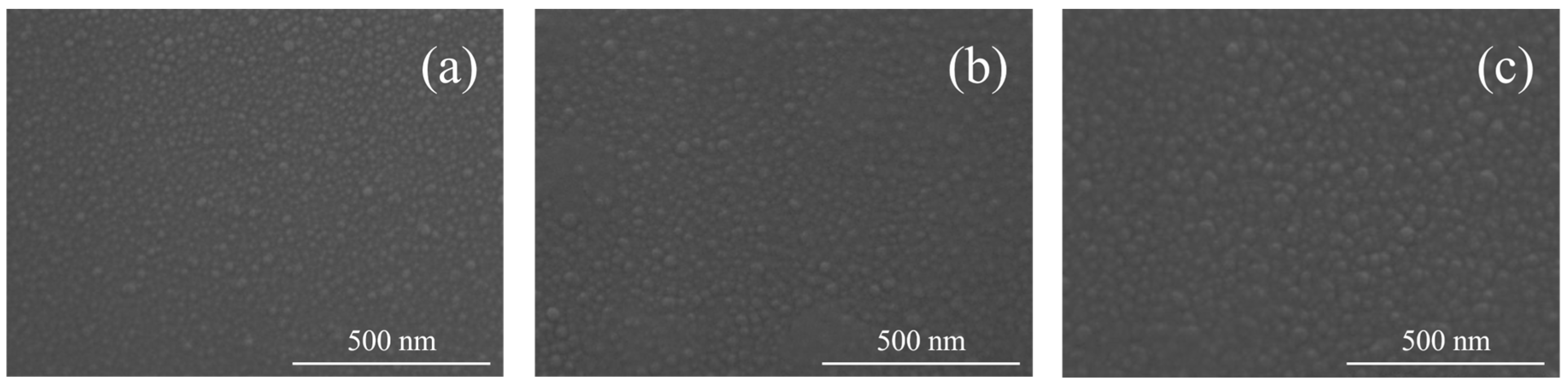

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- F. B. Ryan, O’H., Cha, S.-W., Colella, W., Prinz, Fuel Cell Fundamentals 3rd edition. 2016.

- O. Z. Sharaf and M. F. Orhan, “An overview of fuel cell technology: Fundamentals and applications,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 32, pp. 810–853, Apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Liu, M. E. Lynch, K. Blinn, F. M. Alamgir, and Y. Choi, “Rational SOFC material design: new advances and tools,” Mater. Today, vol. 14, no. 11, pp. 534–546, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- G. Y. Cho, Y. H. Lee, and S. W. Cha, “Multi-component nano-composite electrode for SOFCS via thin film technique,” Renew. Energy, vol. 65, pp.130–136, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- E. Ivers-Tiffée, A. Weber, and D. Herbstritt, “Materials and technologies for SOFC-components,” J. Eur. Ceram. Soc., vol. 21, no. 10–11, pp. 1805–1811, Jan. 2001. [CrossRef]

- N. Mahato, A. Banerjee, A. Gupta, S. Omar, and K. Balani, “Progress in material selection for solid oxide fuel cell technology: A review,” Prog. Mater. Sci., vol. 72, pp. 141–337, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. A. González-García et al., “Electrical and thermal properties of LT-SOFC solid electrolytes: Sm cerates/zirconates obtained by mechanochemistry,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Guo et al., “Thermodynamic analysis of a novel combined heating and power system based on low temperature solid oxide fuel cell (LT-SOFC) and high temperature proton exchange membrane fuel cell (HT-PEMFC),” Energy, vol. 284, p. 129227, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Patakangas, Y. Ma, Y. Jing, and P. Lund, “Review and analysis of characterization methods and ionic conductivities for low-temperature solid oxide fuel cells (LT-SOFC),” J. Power Sources, vol. 263, pp. 315–331, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. B. Kim, J. H. Shim, T. M. Gür, and F. B. Prinz, “Epitaxial and Polycrystalline Gadolinia-Doped Ceria Cathode Interlayers for Low Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells,” J. Electrochem. Soc., vol. 158, no. 11, p. B1453, 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. Bae, S. Hong, B. Koo, J. An, F. B. Prinz, and Y. B. Kim, “Influence of the grain size of samaria-doped ceria cathodic interlayer for enhanced surface oxygen kinetics of low-temperature solid oxide fuel cell,” J. Eur. Ceram. Soc., vol. 34, no. 15, pp. 3763–3768, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- W. Jeong, W. Yu, M. S. Lee, S. J. Bai, G. Y. Cho, and S. W. Cha, “Ultrathin sputtered platinum–gadolinium doped ceria cathodic interlayer for enhanced performance of low temperature solid oxide fuel cells,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, vol. 45, no. 56, pp. 32442–32448, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Develos-Bagarinao, R. A. Budiman, S. S. Liu, T. Ishiyama, H. Kishimoto, and K. Yamaji, “Evolution of cathode-interlayer interfaces and its effect on long-term degradation,” J. Power Sources, vol. 453, p. 227894, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Chrzan, J. Karczewski, D. Szymczewska, and P. Jasinski, “Nanocrystalline cathode functional layer for SOFC,” Electrochim. Acta, vol. 225, pp. 168–174, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. H. Lee, H. Ren, E. A. Wu, E. E. Fullerton, Y. S. Meng, and N. Q. Minh, “All-Sputtered, Superior Power Density Thin-Film Solid Oxide Fuel Cells with a Novel Nanofibrous Ceramic Cathode,” Nano Lett., vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 2943–2949, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Matović et al., “Synthesis and characterization of Pr6O11 nanopowders,” Ceram. Int., vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 3151–3155, Apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yi et al., “Boosting the Performance and Stability of Perovskites by Construction of NiFe Alloy and PrOx Heterogeneously Structured Composites for High-Performance Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Anode,” Adv. Funct. Mater., vol. 2412486, pp. 1–11, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Nicollet et al., “An innovative efficient oxygen electrode for SOFC : Pr6O11 infiltrated into Gd-doped ceria backbone To cite this version : An innovative efficient oxygen electrode for SOFC : Pr 6 O 11 infiltrated into Gd-doped ceria backbone,” 2021.

- V. Thangadurai, R. A. Huggins, and W. Weppner, “Mixed ionic-electronic conductivity in phases in the praseodymium oxide system,” J. Solid State Electrochem., vol. 5, no. 7–8, pp.531–537. 2001. [CrossRef]

- V. Frizon et al., “Tuning the Pr Valence State to Design High Oxygen Mobility, Redox and Transport Properties in the CeO2-ZrO2-PrO x Phase Diagram,” J. Phys. Chem. C, vol. 123, no. 11, pp. 6351–6362, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Corby, L. Francàs, A. Kafizas, and J. R. Durrant, “Determining the role of oxygen vacancies in the photoelectrocatalytic performance of WO3 for water oxidation,” Chem. Sci., vol. 11, no. 11, pp. 2907–2914, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Y. Lu, R. Scipioni, B. K. Park, T. Yang, Y. A. Chart, and S. A. Barnett, “Mechanisms of PrOx performance enhancement of oxygen electrodes for low and intermediate temperature solid oxide fuel cells,” Mater. Today Energy, vol. 14, p. 100362, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Okada, S. Miyoshi, and S. Yamaguchi, “Rate Determining Step in ORR of PrO x -Based Film Cathodes,” ECS Trans., vol. 68, no. 1, pp. 987–994, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Z. Naiqing, S. Kening, Z. Derui, and J. Dechang, “Study on Properties of LSGM Electrolyte Made by Tape Casting Method and Applications in SOFC,” J. Rare Earths, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 90–92, Dec. 2006. [CrossRef]

- H. Moon, S. D. Kim, S. H. Hyun, and H. S. Kim, “Development of IT-SOFC unit cells with anode-supported thin electrolytes via tape casting and co-firing,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, vol. 33, no. 6, pp. 1758–1768, Mar. 2008. [CrossRef]

- H. Lee, J. Park, Y. Lim, H. Yang, and Y. B. Kim, “Flash light sintered SDC cathodic interlayer for enhanced oxygen reduction reaction in LT-SOFCs,” J. Alloys Compd., vol. 861, p. 158397, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. U. Dubal, A. P. Jamale, S. T. Jadhav, S. P. Patil, C. H. Bhosale, and L. D. Jadhav, “Yttrium doped BaCeO3 thin films by spray pyrolysis technique for application in solid oxide fuel cell,” J. Alloys Compd., vol. 587, pp. 664–669, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Choi, S. Yoo, J.-Y. Shin, and G. Kim, “High Performance SOFC Cathode Prepared by Infiltration of Lan + 1NinO3n + 1 (n = 1, 2, and 3) in Porous YSZ,” J. Electrochem. Soc., vol. 158, no. 8, p. B995, 2011. [CrossRef]

- W. Yu, S. Lee, W. Jeong, G. Y. Cho, Y. H. Lee, and S. W. Cha, “High performance, enhanced structural stability of co-sputtered nanocomposite anode with neutral stress state for low-temperature solid oxide fuel cells,” Mater. Today Energy, vol. 34, p. 101308, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Pan, J. Wang, Z. Lu, R. Wang, and Z. Xu, “A review on the application of magnetron sputtering technologies for solid oxide fuel cell in reduction of the operating temperature,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, vol. 50, pp. 1179–1193, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang, Y. Zhang, and M. Yan, “A review on the preparation of thin-film YSZ electrolyte of SOFCs by magnetron sputtering technology,” Sep. Purif. Technol., vol. 298, p. 121627, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T.-M. Pan, C.-I. Hsieh, F.-J. Tsai, and T.-W. Wu, “Excellent Electrical Characteristics of Praseodymium Oxide Dielectrics on Si Substrate by Reactive RF Sputtering,” ECS Trans., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 247–250, Apr. 2007. [CrossRef]

- V. Vijaya Lakshmi, R. Bauri, A. S. Gandhi, and S. Paul, “Synthesis and characterization of nanocrystalline ScSZ electrolyte for SOFCs,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, vol. 36, no. 22, pp. 14936–14942, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- H. Liang, J. Xu, D. Zhou, X. Sun, S. Chu, and Y. Bai, “Thickness dependent microstructural and electrical properties of TiN thin films prepared by DC reactive magnetron sputtering,” Ceram. Int., vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 2642–2647, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang, H. Yang, X. Pang, K. Gao, and A. A. Volinsky, “Microstructure, residual stress, and fracture of sputtered TiN films,” Surf. Coatings Technol., vol. 224, pp. 120–125, Jun. 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. Chen, S. R. Bishop, and H. L. Tuller, “Praseodymium-cerium oxide thin film cathodes: Study of oxygen reduction reaction kinetics,” J. Electroceramics, vol. 28, no. 1, pp.62–69, 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Faryna, M. Adamczyk-Habrajska, and M. Lubszczyk, “Influence of grain boundary plane distribution on ionic conductivity in yttria-stabilized zirconia sintered at elevated temperatures,” Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng., vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 1–7, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Korte, A. Peters, J. Janek, D. Hesse, and N. Zakharov, “Ionic conductivity and activation energy for oxygen ion transport in superlattices-the semicoherent multilayer system YSZ (ZrO2 + 9.5 mol% Y2O3)/Y2O3,” Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., vol. 10, no. 31, pp. 4623–4635, 2008. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhang et al., “Pr/Ba cation-disordered perovskite Pr2/3Ba1/3CoO31δ as a new bifunctional electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution reactions,” J. Ceram. Soc. Japan, vol. 126, no. 10, pp.814–819, 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Kamecki, T. Miruszewski, and J. Karczewski, “Structural and electrical transport properties of Pr-doped SrTi 0.93 Co 0.07 O 3-δ a novel SOEC fuel electrode materials,” J. Electroceramics, vol. 42, no. 1–2, pp. 31–40, 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Grima, J. I. Peña, and M. L. Sanjuán, “Pyrochlore-like ZrO2-PrOx compounds: The role of the processing atmosphere in the stoichiometry, microstructure and oxidation state,” J. Alloys Compd., vol. 923, p. 166449, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Poggio-Fraccari, G. Baronetti, and F. Mariño, “Pr3+ surface fraction in CePr mixed oxides determined by XPS analysis,” J. Electron Spectros. Relat. Phenomena, vol. 222, pp. 1–4, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, Y. Tian, Z. Li, X. Wu, L. Wang, and T. Bian, “Boosting the performance of La0.5Sr0.5Fe0.9Mo0.1O3-δ oxygen electrode via surface-decoration with Pr6O11 nano-catalysts,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, vol. 84, pp. 305–312, Sep. 2024. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Timurkutluk, T. Altan, S. Toros, O. Genc, S. Celik, and H. G. Korkmaz, “Engineering solid oxide fuel cell electrode microstructure by a micro-modeling tool based on estimation of TPB length,” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, vol. 46, no. 24, pp. 13298–13317, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, S. Wang, and P. C. Su, “Proton-conducting Micro-solid Oxide Fuel Cells with Improved Cathode Reactions by a Nanoscale Thin Film Gadolinium-doped Ceria Interlayer,” Sci. Rep., vol. 6, no. February, 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Park et al., “Effect of the thickness of sputtered gadolinia-doped ceria as a cathodic interlayer in solid oxide fuel cells,” Thin Solid Films, vol. 584, pp. 120–124, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Nielsen, T. Jacobsen, and M. Wandel, “Impedance of porous IT-SOFC LSCF:CGO composite cathodes,” Electrochim. Acta, vol. 56, no. 23, pp. 7963–7974, Sep. 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Lazanas and M. I. Prodromidis, “Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy─A Tutorial,” ACS Meas. Sci. Au, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 162–193, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. A. Chart, M. Y. Lu, and S. A. Barnett, “High-Performance Oxygen Electrodes for Low Temperature Solid Oxide Cells,” ECS Meet. Abstr., vol. MA2019-01, no. 33, p. 1713, 2019. [CrossRef]

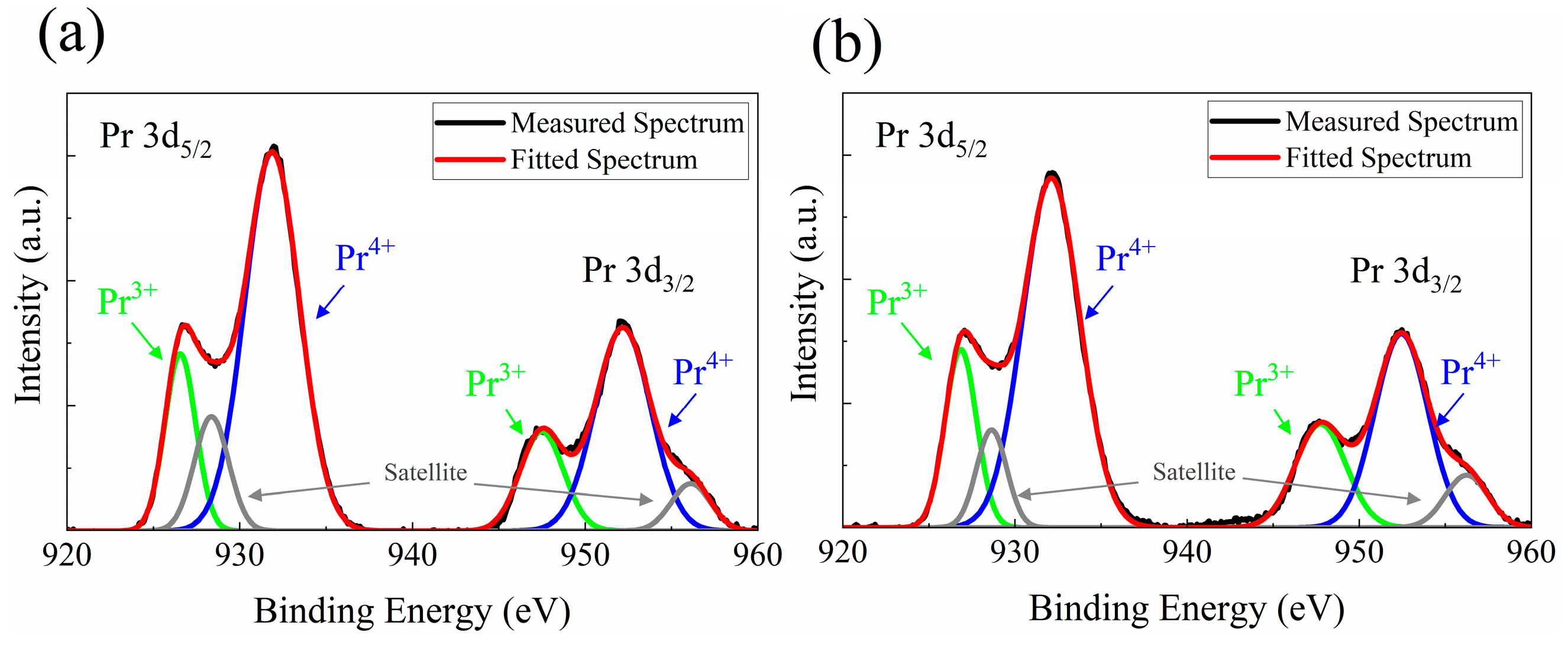

| 500℃ 1hr Annealed | As-deposited | |

| Pr3+ | 23.36 % | 26.52 % |

| Pr4+ | 76.64 % | 73.48 % |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).