1. Introduction

Amphibians have developed a wide range of peptide compounds in their skin as responses to the survival conditions they experience, such as adaptation to the environment, the capture of their prey, and defense against their predators [

1,

2]. Studies have shown that during their metamorphosis process from egg to tadpole and finally to their adult form, they form peptides in response to changes in environmental conditions in their habitat [

3,

4]. The transition to adulthood involves a change of habitat from an aquatic to a terrestrial environment, with more significant challenges [

5], such as high concentrations of O

2 in the air, extreme temperature conditions, and the absence of an essential barrier to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, such as the water column [

4,

6]. This implies that amphibians must face a more oxidizing environment, which generates a more significant number of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in response to these conditions [

7]. Amphibians exhibit a crucial response to oxidative stress-related damage via three defense mechanisms: 1) the production of antioxidant enzymes, including catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GPXs), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and peroxiredoxins, which primarily control endogenous antioxidant functions [

8]; 2) low molecular weight antioxidants (LMWAs) that are not genetically encoded, such as NADH, lipoic acid, and glutathione (GSH) [

9,

10]; and 3) the development of antioxidant peptides (AOPs), which are canonically produced through the activation of endogenous antioxidant defense systems [

11], that act as direct scavengers of free radicals, just as LMWAs do [

9]. In the specific case of amphibians, many studies have demonstrated the presence of AOPs in their skin secretions, playing an essential role in controlling ROS levels [

12].

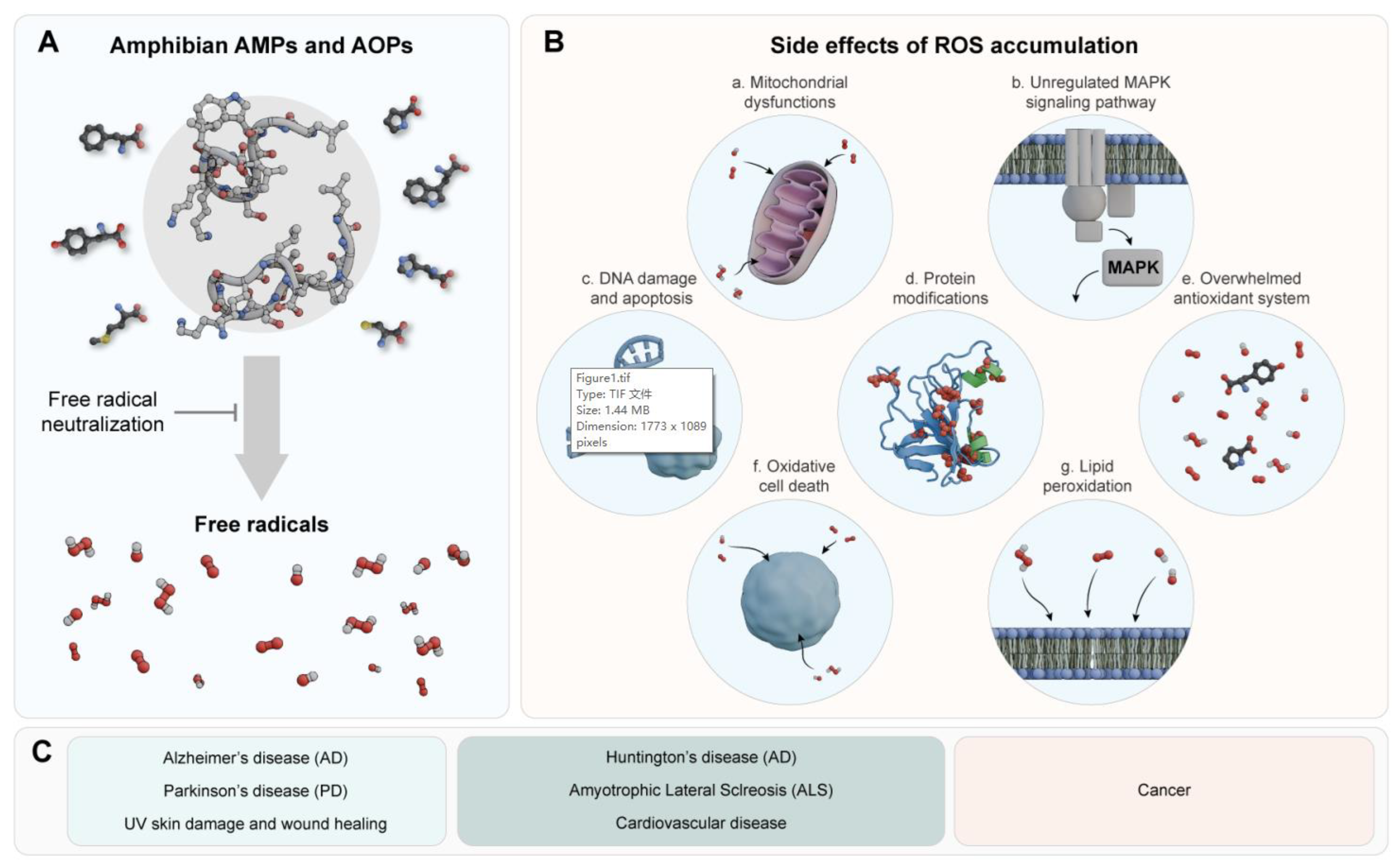

Aerobic organisms naturally produce ROS as a product of their metabolism. Like exogenous sources, these act as signaling molecules in vital physiological processes. However, ROS levels are controlled by endogenous antioxidants in the redox metabolism, allowing ROS to exert their signaling functions without side effects [

13]. When the balance is altered, excess ROS can cause irreversible oxidative damage to biomolecules (lipids, DNA, and proteins, among others), ultimately leading to oxidative stress [

14,

15]. Different studies on these alterations have been associated with the pathophysiology of many human diseases [

13], including cancer [

16,

17], diabetes mellitus (DM) [

18], cardiovascular diseases [

19], and neurodegenerative diseases (NDs) [

13,

20], including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [

21], Parkinson’s disease (PD) [

22], Huntington’s disease (HD) [

23], and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [

24], in addition to accelerating physiological processes such as aging [

25,

26,

27]. Considering the mechanisms of action exerted by AOPs, they can be associated with effective treatments for various conditions associated with oxidative stress [

8], also including antifungal, antiviral, antiparasitic, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory properties among others [

28,

29].

The identification of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) has been the objective of research on amphibian skin since their functions, based on the innate immune response mechanisms exerted by their producers, were extrapolated to represent an alternative therapy to the use of traditional antibiotics [

28]. Different studies have evaluated other characteristics attributed to these AMPs, in addition to antimicrobial properties [

12,

28,

30]. In this context, some AMPs may act as AOPs by chelating metals, inhibiting oxidative processes, and leading to beneficial effects, thus constituting them as multifunctional molecules of interest for treating diseases linked to oxidative stress. However, the structural diversity of AOP and AMP groups in amphibians is quite remarkable, and it could be said that in practically no species are there peptides with an amino acid sequence identical to that found in another. Therefore, a considerable amount of information remains unavailable, and further studies are urgently needed to understand the structure and function of these peptide groups in amphibians, as research on their molecular mechanisms in vivo remains scarce [

31].

2. AMPs from Amphibians with Antioxidant Properties

AOPs of amphibian origin currently totaling more than 100 [

12,

30], in addition to the more than 1900 AMPs reported in the skin of amphibians for 178 species belonging to 28 genera [

4]. Antimicrobial properties have been vital in the search for peptides with significant antioxidant potential, based on the ability of many amphibian species to express peptides with defensive capacity [

28], and protective capacity against oxidation [

8,

32], which regulate microbial infections and oxidative stress, respectively. Finding antioxidant properties in AMPs has been linked to other biological properties associated with free radical scavenging capacity [

29]. In addition, there is evidence of rapid action kinetics of radical elimination in amphibians, which do everything possible to protect the skin from infections or oxidative stress. Unlike AMPs, which act solely as defenses against biological injuries, AOPs can participate in both biological and non-biological injuries, leading us to conclude that defensive peptides likely act in conjunction with oxidative and microbial defenses [

8].

In addition, the relationship between AOPs and AMPs in amphibians reveals a fascinating evolutionary connection. A study on

Rana pleuraden specimens highlights that highly divergent primary structures of AOPs share an

N-terminal preproregion and standard defensive signal peptides with AMPs found in

Ranidae amphibians. BLAST analysis shows a dibasic enzymatic processing site insertion (-Lys-Arg- or -Arg-Arg-) between the spacer and mature peptide. This aligns with other defensive peptide precursors in amphibians, such as AMPs, suggesting that these AOP precursors have a biosynthesis pathway similar to that of AMPs. Interestingly, antimicrobial assays performed on the eleven groups of AOPs from

R. pleuraden showed that seven can be classified as AMPs based on their antimicrobial capabilities [

8]. This allows their classification as bifunctional or multifunctional peptides essential for the innate defense of amphibians [

33].

his leads to the exploration of the antioxidant properties of AMPs derived from amphibian skin secretions while generating information for developing new antioxidant formulations and future treatments for other oxidative stress-related diseases [

4]. To date, the peptides with a high antioxidant potential that have been identified as being of amphibian origin have been evaluated through different in vitro [

12,

30,

34] and in vivo methods [

35], demonstrating a significant effect on diseases directly related to biomolecular damage caused by free radicals, such as premature aging [

27], cancer [

16], and neurological and cardiovascular diseases [

36,

37]. This increases the likelihood of finding in amphibians AOPs with tolerance to unpredictable environmental changes, as they possess a more complex array of innate eco-physiological, behavioral, and immunological traits [

8], which may more effectively counterbalance the imbalance between ROS and antioxidants.

The antioxidant capacity of any substance, whether peptide or not, can be mediated through several mechanisms: 1) ROS scavenging capacity, 2) reducing capacity, 3) metal chelating capacity, 4) protection of biomarkers against oxidation, and 5) association with antioxidant enzymes [

38]. Among the methods frequently used to determine the antioxidant capacity are in vitro methods that measure a peptide’s ability to scavenge free radicals such as DPPH and ABTS [

8], which are the most common due to their relative stability, easy measurement, and good reproducibility [

39], as well as the oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) and the reducing power in the transformation of Fe

3+ to Fe

2+ [

40]. All these methods have made it possible to determine the antioxidant capacity of peptides identified in different amphibian species, preferably by determining the DPPH and ABTS

∙+ radical scavenging capacity.

As already mentioned, other types of antioxidant assays that have been used to determine AOPs derived from amphibians include in vitro and in vivo assays based on the measurement of redox enzymes, which provide information on the degree of oxidative damage to cells [

41]. Moreover, these assays assist in the clinical determination of pathological states. Detecting oxidative stress biomarkers is another method, along with elimination capacity, reduction capacity, and metal chelating capacity, that reflects factors related to systemic or tissue-specific oxidative stress. These molecules are modified or generate various reaction products when interacting with ROS in the surrounding environment [

42]. Biomolecules such as lipids, DNA, and proteins exemplify molecules that can interact and be modified by excess ROS in vivo [

43]. It is essential to highlight that antioxidant mechanisms and the results evaluated by different antioxidant tests can vary widely; therefore, comparing one method with another is difficult. Considering the wide variety of structural characteristics of AOPs, antioxidant tests should not be restricted to a single model. Thus, it is advisable to use different methods to evaluate their antioxidant properties and more accurately indicate their possible protective effects [

12].

Otherwise, studies have shown that part of the effectiveness of AOPs is significantly influenced by the chemical properties of the amino acid residues, including reducibility, hydrophobicity, and electron transfer capacity, which not only promote their interaction with free radicals but also allow their participation in chemical reactions relevant to antioxidation [

44,

45]. In general, the more reducing residues there are in the sequence, the stronger the antioxidant properties of the AOPs will be [

44]. Other researchers have highlighted that the effectiveness of AOPs is closely linked to the types of amino acids that constitute their primary structures. For example, aromatic amino acids such as Phe [

46,

47], Tyr [

48] and Trp [

20], which are common in the structures of AMPs and AOPs, have been shown to contribute significantly to the antioxidant properties of amphibian-derived peptides. Previous studies have shown that these aromatic residues can act as electron donors due to their electron-rich aromatic structure, and they may help stabilize ROS through interactions that involve direct electron transfer [

45]. It has also been reported that Tyr and Trp could play an antioxidant role in cell protection, as they are highly effective in protecting cells. Their phenolic and indolyl groups can be converted into relatively stable phenoxy and indolyl radicals, which can directly capture free radicals as hydrogen donors, thus achieving the function of scavenging free radicals [

49]. The transmembrane domains of integral membrane proteins exhibit substantial enrichment in Tyr and Trp residues, and data suggest that these residues are common and widespread in regions of higher lipid density [

50]. These amino acid residues exert essential antioxidant functions within the lipid bilayer and protect cells from oxidative damage. They act as potent inhibitors of lipid peroxidation and oxidative cell death[

51]. Histidine (His) exhibits strong antioxidant properties due to its imidazole rings acting as proton donors. In addition to His, Lys and Val can scavenge hydroxyl radicals by serving as electron donors, creating a hydrophobic microenvironment within the molecule that enhances the peptide’s antioxidant capacity [

52].

Sulfur-containing amino acids such as Met and Cys have also been suggested to be important in the antioxidant function of peptides [

20,

48], since the unpaired thiol group of Cys is crucial for free radical scavenging, attributed to its ability to donate an electron to a radical [

53]. Another study indicates that AOPs with a free Cys are the dominant components of highly antioxidant peptides in the species

Odorrana andersonii [

54], where the scavenging activity of such peptides would be mainly related to the disulfide bridge and, secondarily, to the hydroxyl groups present in the synthesized peptide sequence, thus contributing to their hydrogen donation capacity [

55]. Additionally, other studies confirm that the antioxidant activity of some AOPs from pleurain, odorranain, and brevinin families are directly correlated with the number of Cys residues and disulfide bridges [

56]. For example, in the study by Yang et al. (2012), the authors demonstrated that the antioxidant activity of cyclic peptides with cysteine residues forming a disulfide bridge was lower than that of linear peptides. This finding might imply that linear peptides with free cysteine residues play a more critical role in the antioxidant defense system of the skin [

57].

This study gathers research on AMPs with antioxidant properties, focusing on their amino acid content across various amphibian families, especially in the

Ranidae family [

28,

30], as listed in Table 1. These peptide families have demonstrated important physicochemical properties linked to mechanisms that protect the skin from free radicals, suggesting promising potential for other pharmacological applications [

28,

29,

58,

59,

60,

61].

Antioxidin Family

As the first peptide group with antioxidant potential reported, the antioxidins have demonstrated their capacity to eliminate free radicals in different studies, which has led to ongoing research on this peptide family to this day [

35]. The first AOPs to be discovered were antioxidin-RP1 (AMRLTYNKPCLYGT) and antioxidin-RP2 (SMRLTYNKPCLYGT), 14-amino acid peptides derived from the

Rana pleuraden species. Antioxidin-RP1 was shown to be the most potent peptide in scavenging free radicals of DPPH and ABTS

∙+, capable of eliminating 100% of the radicals at a concentration of 80 μg.mL

-1. It exhibited the highest capacity to reduce Fe

3+ ions to Fe

2+ compared to other AOPs and the highest release of nitric oxide (NO), produced by the sodium nitroprusside dihydrate (SNP) NO donor [

8].

Another AOP belonging to this class is antioxidin-RL (AMRLTYNRPCIYAT), obtained from

Odorrana livida, which was characterized by its potent free radical scavenging capacity, determined through ABTS

•+ assays [

62], and strong in vitro and in vivo UVB-induced response tests. It was observed that antioxidin-RL successfully penetrates the cell membrane and positively affects cell migration, increasing collagen deposition through in in vivo experiments [

63]. Currently, only antioxidin-RL [

8] and OA-VI12 (VIPFLACRPLGL) [

11], isolated from

O. livida and

O. andersonii, respectively, have been described with possible protective effects on amphibian skin through in vivo assays [

11,

63], showing that they prevent UVB irradiation-induced photoaging in mice. However, the mechanisms of action of these two AOPs are still not fully understood [

35].

Antioxidin-2 (YMRLTYNRPCIYAT) was designed as an analog of antioxidin-RL by replacing the

N-terminal Ala with Tyr to improve free radical binding capacity. Antioxidant testing of this analog was performed using in-solution free radical scavenging assays, and the results showed that it scavenged free radicals faster than antioxidin-RL [

64]. However, using PC-12 cell models (a mouse neuronal cell line derived pheochromocytoma), demonstrated that, although antioxidin-2 and antioxidin-RL inhibited the accumulation of intracellular free radicals induced by H

2O

2, they preserved mitochondrial morphology and reduced the expression of dynamin-related protein-1 in mitochondria. Antioxidant-RL was shown to be more effective in preventing the dissipation of the mitochondrial membrane potential [

64].

Antioxidin-I (TWYFITPYIPDK), a 12-amino acid peptide identified in

Physalaemus nattereri, were evaluated through in vitro free radical scavenging tests and showed poor performance in most free radical scavenging assays, except for the ORAC assay. However, when tested on murine fibroblasts, antioxidin-I exhibited low cytotoxicity by suppressing menadione-induced redox imbalance. Furthermore, it could substantially attenuate hypoxia-induced ROS production when tested on live microglial cells exposed to hypoxia, suggesting a possible neuroprotective role for this peptide. Antioxidin-I is found in the skin tissue of three additional tropical frog species

Phyllomedusa tarsius, P. distincta, and

Pithecopus rohdei [

46].

In another study, antioxidin-NV (GWANTLKNVAGGLCKMTGAA), obtained from the frog

Nanorana ventripunctata, was a protective peptide against skin photodamage. It reduced skin erythema, thickness, and wrinkle formation caused by UVB exposure in hairless mice. This AOP directly and rapidly scavenged excess ROS after UVB irradiation, alleviating UVB-induced DNA damage, cell apoptosis, and inflammatory response, thereby protecting against UVB-induced skin photoaging. The antioxidant activity was determined by the ABTS method, confirming that the properties of antioxidin-NV make it a promising candidate for the development of a novel antiphotoaging agent [

35].

Studies identified the peptide antioxidin-PN (FLPSSPWNEGTYVLKKLKS) from the total RNA expression of

Pelophylax nigromaculatus, also present in the same species but from different specimens distributed in two provinces of China: Yunnan and Guizhou. The peptide was evaluated for its antioxidant properties, demonstrating, like the other eight synthesized peptides, substantial elimination of ABTS

∙+ free radicals in a dose-dependent manner, eliminating 30% of the ABTS

∙+ radical at 15 seconds and 100% in 10 minutes at a low concentration (6.25 µg.mL

-1, approximately 2.85 µM). The results of this study allowed us to determine that gene-environment interaction is an essential factor in the diversity of bioactive peptides within the same species. Nonetheless, additional research is required to elucidate its mechanisms of action further [

65].

One study supports the notion that the antioxidant potential of peptides such as antioxidins may be due to the content of Pro residues, since all those found there presented at least one in their structure [

8]. The study demonstrated that Pro protects cells against H

2O

2, butyl tert-hydroperoxide, and a carcinogenic inducer of oxidative stress [

66].

Pleurain Family

Pleurain is another AMP group found in the skin of

Rana pleuraden, where in addition to the antioxidin-RP1 and antioxidin-RP1, the identification of 13 new potential antioxidant peptide groups, comprising 36 members, was reported through a peptidomic and genomic approach [

8]. In an earlier study, the antioxidant group pleurain-A had already been reported [

3]. Of the total, 11 of the 14 groups exerted antioxidant activity (pleurain-A, -D, -E, -G, -J, -K, -M, -N, -P, -R, and antioxidin-RP). Some groups, such as pleurain-B and pleurain-N, exerted only antimicrobial and antioxidant activity, respectively, while others, such as pleurain-G, showed both antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. All peptide groups share the characteristic of containing Pro residues, suggesting that this amino acid may play an essential role in their antioxidant capacity. This conclusion is supported by the fact that the study emphasized the importance of the molecular basis of AOPs, taking into account that all amino acid residues related to antioxidant activity, such as Pro, Met, Cys, Tyr, and Trp in their free form, were replaced by Gly in the 11 peptide groups. The results showed that of substituting Pro, Met, free Cys, or Trp significantly decreased their antioxidant capacity, while substituting Trp had only a slight effect. It was also confirmed that replacing all these amino acid residues eliminated their antioxidant function [

8].

Cathelicidin Family

Another of the first peptide groups reported for amphibians is the cathelicidins. Although many have been reported for mammals [

67], very few have been identified for amphibians. Only eight cathelicidins have been reported in frogs [

68,

69]. In a recent study, cathelicidin-OA1 (IGRDPTWSHLAASCLKCIFDDLPKTHN, featuring a disulfide bridge) was identified from the skin of

Odorrana andersonii, produced by post-translational processing of a 198-residue pre-propeptide [

69]. Functional analysis showed that cathelicidin-OA1 did not generate direct microbial killing, acute toxicity, or hemolytic activity, but it exhibited antioxidant activity, evidenced by the radical scavenging activity of ABTS

∙+ and DPPH. Compared with other odorous frog peptides, such as adersonine-AOP1 (FLPGLECVW), the antioxidant activity of cathelicidin-OA1 was slightly weaker. However, when the intramolecular disulfide bridge of cathelicidin-OA1 was broken, the antioxidant activities of linear cathelicidin-OA1 (containing two free Cys residues) and the mutant cathelicidin-OA1 (C14/A, containing one free Cys residue due to the change of Cys-14 by an Ala) were significantly enhanced. Research supports the idea that Cys enhances the antioxidant activities of a specific peptide; except for tylotoin (KCVRQNKRVCK), an amphibian cathelicidin that typically demonstrates direct microbe-killing effects [

70]. Cathelicidin-OA1 was also shown to accelerate wound healing in human keratinocytes (HaCaT) and skin fibroblasts (HSF) by inducing cell proliferation [

69].

In another study, cathelicidin-NV (ARGKKECKDDRCRLLMKRGSFSY), previously identified in the spot-bellied plateau frog

Nanorana ventripunctata, was shown to alleviate UVB-induced skin photoaging in mice. Furthermore, the peptide effectively suppressed cytotoxicity, DNA fragmentation, and apoptosis. It reduced the protein expression levels of c-Jun

N-terminal kinase (JNK), transcription factor Jun (c-Jun), and matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1), which are involved in regulating collagen degradation in HaCaT cells induced by UVB irradiation. Cathelicidin-NV directly scavenged excess intracellular ROS to protect HaCaT cells, thereby alleviating photoaging and positioning it as an excellent candidate for preventing and treating UV-induced skin photoaging [

68].

Additionally, a novel peptide from the cathelicidin family, named Cath-KP (GCSGRFCNLFNNRRPGRLTLIHRPGGDKRTSTGLIYV), was identified from the skin of the Asian painted frog,

Kaloula pulchra. Circular dichroism and homology modeling indicated an α-helix conformation for Cath-KP. The results demonstrated antioxidant properties through free radical scavenging and iron reduction analyses. Using 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion (MPP+) in a dopamine-induced cell line and PD mice induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), Cath-KP was found to penetrate cells and reach deep brain tissues, resulting in increased cell viability and reduced oxidative stress-induced damage by promoting the expression of antioxidant enzymes. It also alleviated the accumulation of mitochondrial and intracellular ROS through activation of the Sirtuin-1 (Sirt1)/nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway, with focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and p38 identified as regulatory elements. In MPTP-induced PD mice, administration of Cath-KP increased the number of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-positive neurons, restored TH content, and improved dyskinesia [

71].

Spinosan Family

In the study of

Paa spinosa skin, precursor cDNAs of four new AMPs were cloned, and their peptide sequencing revealed the presence of a new family of frog AMPs different from those already reported for other amphibians. The four peptides found were spinosan-A (DLGKASYPIAYS), spinosan-B (DYCKPEECDYYFSFPI), spinosan-C (DLSMMRKAGSNIVCGLNGLC) and spinosan-D (MEELYKEIDDCVNYGNCKTLKLM), which were chemically synthesized and evaluated against antimicrobial, antioxidant, hemolytic and cytotoxic activities [

72]. The peptides showed a weak hemolytic effect against rabbit erythrocytes and, in turn, exhibited a strong antioxidant effect through free radical scavenging methods. In the DPPH free radical scavenging assay, spinosan-A, -B, -C, and D- peptides exhibited significant radical scavenging results at a concentration of 80 μg.mL

-1. For example, spinosan-C showed a free radical scavenging percentage of 85%, while spinosan-A, -B, and -D showed respective scavenging values of 52%, 59%, and 49%. The study maintains that peptides with potential antioxidant activity always contain Cys, Pro, Met, Tyr, or Trp residues responsible for free radical scavenging activity [

72].

Jindongenin and Palustrin Families

Jindongenin-1a (DSMGAVKLAKLLIDKMKCEVTKAC) is a 24-amino acid peptide from the jindongenin AMP peptide family reported from the Chinese torrent frog

Amolops jingdongensis. The palustrin family was also identified as being of the same species. Palustrin-2AJ1 (GFMDTAKNVAKNVAVTLIDKLRCKVTGGC) and palustrin-2AJ2 (GFMDTAKQVAKNVAVTLIDKLRCKVTGGC) have similar structures to jindongenin-1a. These three peptides have high sequence similarity in the signal and propeptide regions (42 aa). These similarities suggest that these two families of AMPs may have arisen from an ancestral gene via genetic duplication and splicing or domain shuffling. Jindongenin-1a and Palustrin-2AJ1 were synthesized to analyze their antimicrobial, hemolytic, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities. Both peptides showed broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against standard and clinically isolated bacterial strains. However, DPPH free radical scavenging assays indicated that Jindongenin-1a and Palustrin-2AJ1 exhibited low antioxidant activity at doses up to 32 mM (8% inhibition) and 25 mM (6% inhibition). The results suggest that these peptides do not play a key role in the habituation of

A. jingdongensis to intensive UV exposure; future studies may determine the factors contributing to this adaptation [

34].

However, in a study carried out on three species of frogs from East Asia (

Amolops lifanensis, Amolops granulosus and

Hylarana taipehensis), a peptide group denominated palustrin-2GN was identified from

A. granulosus along with other important groups of AOPs and AMPs such as temporin and brevinine. The peptides palustrin-2GN1 (GLWNTIKEAGKKFALNLLDKIRCGIAGGCKG), palustrin-2GN2 (GFMDTAKNVFKNVAVTLLDKLKCKIAGGC), and palustrin-2GN3 (GILDTLKQLGKAAAQSLLSKAACKLAKTC) showed antimicrobial activity against different Gram-positive strains such as

Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923),

Enterococcus faecium 091299 (IS), and Gram-negative strains such as

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CGMCC 1.50)

, Klebsiella pneumoniae 08040724 (IS),

Enterobacter cloacae (CGMCC 1.57) and

Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922)

, among others. However, only palustrin-2GN1 exhibited a weak effect on scavenging free radicals ABTS

•+ and DPPH [

32]. In this study, as well as in previous research, it was shown that the presence of amino acid residues of Pro, Met, Cys, Tyr, or Trp contributes to the antioxidant function of peptides [

8,

48]. The structure of these AMPs contains one or more of the amino acids listed above; however, the study also indicated that peptides containing the aforementioned amino acids do not necessarily exhibit antioxidant activity. For example, palustrin-2GN2 did not show antioxidant activity in the free radical scavenging activity test, even though it contained one or more of these amino acids [

32].

Taipehensin Family

From

Hylarana taipehensis, a frog from East Asia, two AOPs denominated taipehensin-1TP1 (TLIWEFYHQILDEYNKENKG) and taipehensin-2TP1 (CLMARPNYRCKIFKQC) were identified. These AOPs exhibited a strong ABTS

∙+ free radical scavenging capacity and efficient DPPH free radical scavenging kinetic activity, similar to other reported AOPs [

8,

62]. The free radical scavenging rates of ABTS

•+ and DPPH were determined after 30 minutes. At a concentration of 200 mM, Taipehensin-1TP1 rapidly scavenged 34.1% of ABTS

•+ in 1 minute, with a final scavenging rate of 65.4% after 30 minutes. Among these peptides, taipehensin-2TP1 (>50 mM) showed the highest scavenging ability and scavenged almost all ABTS

•+ in 1 min. The ability of taipehensin-2TP1 to scavenge DPPH free radicals was lower than its ability to scavenge ABTS

•+. At 50 mM, taipehensin-2TP1 scavenged only 85.4% of DPPH free radicals in 30 minutes. At a concentration of 200 mM, it showed scavenging solid ability for ABTS

•+ and DPPH free radicals, with scavenging rates of 99.8% and 98.8%, respectively [

32].

Brevinin Family

Brevinin-1TP1 (FLPGLIKAAVGVGSTILCKITKKC), brevinin-1TP2 (FLPGLIKAAVGIGSTIFCKISKKC), brevinin-1TP3 (FLPGLIKVAVGVGSTILCKITKKC), brevinin-1TP4 (FLPGLIKAAVGIGSTIFCKISRKC), brevinin-2TP1 (SILSTLKDVGISAIKSAGSGVLSTLLCKLNKNC), and brevinin-2TP2 (SILSTLKDVGISALKNAGSGVLKTLLCKLNKNCEK) from

Hylarana taipehensis, as well as brevinin-1LF1 (FLPMLAGLAANFLPKIICKITKKC), brevinin-1LF2 (FLPIVASLAANFLPKIICKITKKC), brevinin-2LF1 (GFMDTAKNVAKNVAKNVAVTLLDKLRCKVTGGC), and brevinin-2LF2 (SIMSTLKQFGISAIKGAAQNVLGVLSCKIAKTC) from

Amolops lifanensis, are examples belonging to this family. Some of these AMPs, as is the case with brevinin-1TP1, brevinin-1TP2, brevinin-1TP3, and brevinin-1LF, are active against a broad microbial spectrum, as well as having ABTS

•+ or DPPH free radical scavenging capacity. Others, such as brevinin-2LF1, presented an MIC of 3.1 µM against the Gram-negative bacteria

Psychrobacter faecalis X29. Additionally, brevinin-1TP1 showed both antioxidant and antimicrobial activity, with a free radical scavenging percentage of ABTS

•+ of 26.5% at a concentration of 200 µM and suitable minimum inhibitory concentrations against different microbial strains such as

Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923) with MIC = 12.5 µM,

Enterococcus faecalis 981 with MIC = 6.3 µM,

Nocardia asteroides 201118 (IS) with MIC = 6.3 µM,

Psychrobacter faecalis X29 with MIC = 6.3 µM, and

Candida glabrata 090902 with MIC = 12.5 µM [

32].

Another AOP identified in this family is brevinin-1FL (FWERCSRWLLN), derived from the skin of the frog

Fejervarya limnocharis. Functional analysis demonstrated that brevinin-1FL could scavenge ABTS

•+, DPPH, NO, and hydroxyl radicals in a concentration-dependent manner while reducing iron oxidation. Furthermore, brevinin-1FL was found to display neuroprotective activity by reducing malondialdehyde (MDA) and ROS levels, enhancing the activity of endogenous antioxidant enzymes, and inhibiting H

2O

2-induced death, apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest in PC-12 cells, which was associated with its regulation of the AKT/MAPK/NF-kB signaling pathways. Furthermore, brevinin-1FL decreased paw edema and lowered levels of TNF-alpha, IL-1β, IL-6, myeloperoxidase (MPO), and MDA, while restoring CAT and SOD activity, as well as GSH content in carrageenan-injected mice. The findings suggest that brevinin-1FL, holds significant therapeutic potential for diseases associated with oxidative damage [

73].

Nigroain Family

In other studies, 50 peptides classified into 21 peptide families with antioxidant or antimicrobial activity were identified from the species

Amolops daiyunensis, Hylarana maosuoensis,

Pelophylax hubeiensis, and

Nanorana pleskei, belonging to the

Ranidae and

Dicroglossidae families. From

H. maosuoensis, peptides belonging to the nigroain family were identified, such as nigroain-B-MS1 (CVVSSGWKWNYKIRCKLTGNC), nigroain-C-MS1 (FKTWKNRPILSSCSGIIKG), nigroain-D-SN1 (CQWQFISPSRAGCIGP) and nigroain-K-SN1 (SLWETIKNAGKGFILNILDKIRCKVAGGCKT). Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity assays showed that some of these peptides exhibited significant results. For example, at a concentration of 50 μM, both nigroain-B-MS1 and nigroain-C-MS1 showed relatively strong ABTS

•+ and DPPH free radical scavenging abilities, with scavenging rates of 99.7% and 68.3% for nigroain-B-MS1, and 99.8% and 58.3% for nigroain-C-MS1, respectively. Nigroain-B-MS1 also showed activity against Gram-positive bacteria such as

Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923) with MIC = 4.7 μM and

Nocardia asteroides 201118 (IS) with MIC = 18.8 μM. Nigroain-C-MS1 only showed antimicrobial activity against the same strain of

Nocardia with a MIC of 150 μM. Interestingly, these two peptides showed weak hemolytic activity [

74].

Andersonin Family

From

Odorrana andersonii, a Chinese odorous frog, 38 novel mature AMPs grouped into 25 different subfamilies were identified: andersonin-A, -B, -C, -E, -F, -J, -L, -M, -N, -O, -P, -R, -S, -T, -U, -X (all with only one peptide), andersonin-I, -K, -Q, -V, -Y (all with two peptides), and andersonin-D, -G, -H, -W (all with three peptides). Eight peptides were synthesized and assayed for antimicrobial, antioxidant, and other activities. Only andersonin-C1 (TSRCIFYRRKKCS) and andersonin-D1 (FIFPKKNIINSLFGR) showed killing effects against the tested strains (andersonin-C1 showed MICs of 30 µg.mL

-1 against

E. coli,

C. albicans, as well as

B. pyocyaneus, and MIC > 120 µg.mL

-1 against

S. aureus; while andersonin-D1 showed MIC > 126 µg.mL

-1 against

E. coli, but MICs of 16 µg.mL

-1 against

C. albicans,

B. pyocyaneus, and

S. aureus). Andersonin-C1, andersonin-N1 (ENMFNIKSSVESDSFWG), and andersonin-R1 (ENAEEDIVLMENLFCSYIVGSADSFWT) showed a scavenging rate percentage against ABTS

•+ radicals greater than 70%. Interestingly, andersonin-C1 features a cyclic motif with a disulfide bond at the

C-terminus, showing potent antioxidant activity. However, others such as andersonin-G1 (KEKLKLKCKAPKCYNDKLACT) and andersonin-H3 (VAIYGRDDRSDVCRQVQHNWLVCDTY), both with a cyclic motif as well, showed lower antioxidant activity, with scavenging rate percentages against ABTS

•+ radicals greater than 20% and 30%, respectively. Only the peptides andersonin-D1, andersonin-Q1 (EMLKKKKEVKMERKT), and andersonin-S1 (DANVENGEDAEDLTDKFIGLMG) did not show detectable antioxidant activity [

57]. The antioxidant activity of cyclic peptides was lower than that of linear peptides when compared with other families of AMPs with free Cys. Some studies support the proposition that peptides with potential antioxidant activity always contain a free Cys residue responsible for the free radical scavenging activity [

62].

Considering that most studies on amphibians have been limited to the genetic mechanisms of adaptation to low oxygen levels and temperature in high-altitude areas, it was found that very few studies focused on the adaptation of amphibians to UV radiation according to altitude, which demonstrates the development of specialized molecules in response to such conditions. Therefore, in a study conducted on two species of frogs present in different altitudinal zones—specifically, the frog

Odorrana andersonii, found in plateau areas (approximately 2,500 m) of Yunnan province in China, which is subject to long exposures to sunlight and intense UV radiation; and the cave frog

O. wuchuanensis, distributed in a small number of caves that do not receive light throughout its life cycle at an altitude of 800 m in Guizhou province—it was found that the peptide families of these two species differ significantly in their antioxidant potential. The species

O. andersonii exhibited peptides with greater diversity and free radical scavenging potential against UV radiation than those in

O. wuchuanensis. Here, 26 new subfamilies belonging to the andersonin family were identified from high-altitude areas for

O. andersonii. Most of these AOP subfamilies contained only one member, but others exhibited high diversity, such as andersonin-AOP8 and andersonin-AOP14, which included six and five members, respectively. Andersonin-AOP1 (FLPCLECVN) was the shortest AOP, while andersonin-AOP25 (ATALGIPPRGFLPIVNKFKDIILC) and andersonin-AOP26 (IPWKLPATLRPVENPFSKPLCRNY) were the longest AOPs (24 amino acids each). The antioxidant activity results for AOPs showed that AOPs from

O. andersonii skin exhibited potential ABTS

•+ scavenging activities more significant than 90% to 50 μM., except for andersonin-AOP9 (LKGFEMGMDMKRT, 51.33%), andersonin-AOP13 (APDRPRKFCGILG, 84.69%), andersonin-AOP17 (VTPPWARIYYGCAKA, 66.67%), and andersonin-AOP19a (GAGFWKMGKYGQKRRD, 60.00%). These results were further confirmed by determining DPPH free radical scavenging activity, as most of the AOPs from

O. andersonii completely scavenged DPPH radicals, suggesting that

O. andersonii has developed a much more complex and compelling skin AOP system to survive high-altitude UV radiation levels [

54].

Odorranain Family

Odorrana has the most abundant and diversified AMPs among all studied amphibian genera. Even from a single frog, 46 cDNA sequences encoding precursors of 22 different AMPs were characterized from the skin of

Odorrana tiannanensis. Ten peptides, grouped into six subfamilies, correspond to the odorranain family. Specifically, two AMPs, odorranain-C7HSa (SLLGTVKDLLIGAGKSAAQSVLKGLSCKLSKDC) and odorranain-G-OT (FVPAILCSILKTC), were purified from the skin secretions of

O. tiannanensis, and their amino acid sequences matched the deduced sequences of the cDNAs. Odorranain-A-OT (VVKCSFRPGSPAPRCK), identified from the cDNA sequences, has the most potent antioxidant activity, scavenging 89.24% of the DPPH radicals, followed by odorranain-G-OT, which exhibited a scavenging rate of 70.41% at a concentration of 80 mg.mL

-1. The study argues that the scavenging activity of the peptides is mainly related to the disulfide bridge, as well as the hydroxyl groups from the main chain of residues such as Ser and Thr, which possibly contribute to their hydrogen-donating capacity [

56].

Hainanenin Family

From the skin secretions of the frog

Amolops hainanensis, two new AMPs belonging to this family were identified from the cloning of 31 cDNA sequences encoding ten new AMPs across four peptide families. These two new peptides are hainanenin-1 (FALGAVTKLLPSLLCMITRKC) and hainanenin-5 (FALGAVTKRLPSLFCLITRKC), each consisting of 21 amino acid residues with a 7-residue

C-terminal disulfide loop between Cys-15 and Cys-21. Hainanenin-1 and hainanenin-5 were synthesized and tested in vitro for antimicrobial, antioxidant, and hemolytic activities. The results showed that hainanenin-1 and hainanenin-5 possessed robust and broad-spectrum antimicrobial activities against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and fungi, including many clinically isolated drug-resistant pathogenic microorganisms. However, they exhibited slight antioxidant activity and undesirable hemolytic responses in human erythrocytes [

53]. Although one aim of the study was to demonstrate that most of the peptides display multiple functions, such as antioxidant and antimicrobial activitie [

8,

33,

62], it was observed that at concentrations up to 160 µg.mL

-1, hainanenin-1 and hainanenin-5 showed no apparent antioxidant activity against DPPH free radicals, with free radical scavenging percentages of 3.60% and 1.52%, respectively. The thiol groups of cysteines are considered crucial for the free radical scavenging activity of peptides, as they can donate electrons to a free radical [

48,

62]. However, it is concluded that the thiol groups of the two cysteines in hainanenin-1 and hainanenin-5 are oxidized and form a disulfide bridge, which may cause the absence of their antioxidant activities [

53].

FW Family

Another peptide family is FW, found in the tree frog

Hyla annectansis, inhabiting the southwestern plateau area of China, where there is intense UV radiation and long periods of sunlight. This indicates that its bare skin may contain chemical defense components that protect it from acute photodamage [

75]. However, to date, no peptide demonstrating this effect has been identified. In this work, two novel peptides, FW-1 (FWPLI-NH

2) and FW-2 (FWPMI-NH

2), were identified, which showed potential antioxidant effects in the epidermis by attenuating UVB-induced ROS production through an unknown mechanism. The study tested the effects of FW-1 and FW-2 on UVB-induced ROS accumulation, demonstrating that ROS production was significantly increased when HaCat cells were irradiated with UVB, and the peptides significantly attenuated UVB-induced ROS production. FW-1 and FW-2 inhibited UVB-induced ROS production remarkably at a concentration of 12 mg.mL

-1, showing effects comparable to the positive control,

N-acetylcysteine (NAC). Considering the ease of production, storage, and potential photoprotective activity of these two small peptides, FW-1 or FW-2 could be used as exciting lead compounds or templates for developing new pharmacological agents to suppress UVB-induced skin inflammation. Furthermore, this study could expand our understanding of the defensive mechanisms of tree frog skin against UVB irradiation [

75].

OM Family

From the OM family, obtained from skin secretions of odorous frogs

Odorrana margaretae, a novel peptide was identified, produced by post-translational processing of a 71-residue prepropeptide. This peptide, OM-LV20 (LVGKLLKGAVGDVCGLLPIC), contains an intramolecular disulfide bridge at the

C-terminus and exhibits weak antioxidant activity. Although it had no direct antimicrobial effects, hemolytic activity, or acute toxicity, OM-LV20 effectively promoted wound healing in human keratinocytes (HaCaT) and human skin fibroblasts (HSF) in both a time- and dose-dependent manner. For that, OM-LV20 provides a new template for bioactive peptides in the development of novel wound healing agents and drugs [

76].

A novel AOP produced by post-translational processing of a 61-residue prepropeptide was also discovered from the skin secretions of

Odorrana margaretae and was named OM-GF17 (GFFKWHPRCGEEHSMWT). OM-GF17 did not exhibit direct antimicrobial activity but could scavenge free radicals like ABTS

•+, DPPH, and NO, as well as reduce oxidized Fe

3+ ions. However, these activities were slightly weaker than other peptides identified in the odorous frog, such as adersonine-AOP1 [

54]. The results also demonstrated that five amino acid residues, including Cys, Pro, Met, Trp, and Phe, are related to the antioxidant activity of OM-GF17. There was no apparent influence on ABTS

•+ radical scavenging activity when all five amino acids were mutated individually; however, the antioxidant activity was abolished when all five amino acids were mutated together. When Met-15 and Trp-16 were replaced, the new mutant showed a decrease in scavenging rate to approximately 50 seconds, and when Trp-5 and Cys-9 were replaced, the scavenging rate decreased to approximately 60 seconds. OM-GF17 reached a maximum scavenging rate in 10 seconds. These five amino acids influence ABTS

•+ scavenging efficiency; specifically, Phe-2, Phe-3, and Pro-7 showed greater responsibility for the scavenging efficiency of OM-GF17. Additionally, it was observed that the Cys-9 mutant of OM-GF17 resulted in eliminated Fe

3+-reducing power, while for (Phe-2/Ala), (Phe-3/Ala), (Trp-5/Ala), (Pro-7/Ala), (Met-15/Ala), and (Trp-16/Ala), mutants of OM-GF17 showed similar activity to the natural parental peptide. This demonstrates that Cys-9 is responsible for the peptide’s Fe

3+-reducing power. Thus, the antioxidant activity of amphibian peptides might be related to their amino acid composition and sequence. Although free Cys, Pro, Met, Trp, and Phe residues are considered responsible for the general antioxidant activity of OM-GF17, it does not necessarily mean that they all directly participate in the quenching of free radicals. On the other hand, this novel gene-encoded antioxidant peptide may help in the development of new antioxidant agents [

77].

In another study, a novel antioxidant peptide named OM-GL15 (GLLSGHYGRASPVAC) was identified from the skin of the green odorous frog

Odorrana margaritae. Its antioxidant activity was demonstrated by evaluating its ability to scavenge ABTS

•+ and DPPH free radicals and its power to reduce Fe

3+ to Fe

2+. Exploration of the underlying mechanisms further demonstrated that OM-GL15 exerts significant antioxidant potential by reducing lipid peroxidation and malondialdehyde levels, protecting epidermal cells from UVB-induced apoptosis. It inhibits DNA damage by downregulating p53, caspase-3, caspase-9, and Bax and upregulating Bcl-2. Additionally, the topical application of OM-GL15 significantly reduced UVB-induced skin photodamage in mice. These results emphasize the potential use of amphibian skin-derived peptides for protection against UVB-induced photodamage and present a new candidate peptide for the development of anti-photodamage agents [

31].

OA Family

In a previous study of the skin secretions of the frog

Odorrana andersonii, coding a short gene led to the peptide OA-VI12 (VIPFLACRPLGL) expression. This peptide was shown to exert a direct scavenging capacity for free radicals, suggesting a possible role in protecting the skin from photodamage due to its high-altitude habitat [

69]. OA-VI12 was analyzed in models of oxidative stress induced by UVB irradiation and hydrogen peroxide in immortalized human keratinocytes. The results showed that OA-VI12 preserved cell viability, enhanced the release of CAT, and reduced levels of lactate dehydrogenase and ROS. Furthermore, the peptide stimulated the production of SOD and GSH, reduced the thickness of the epidermis and dermis, and minimized the formation of light spots and collagen fibers in the skin of the photoinjured mouse model. These findings highlight the beneficial role of the AOPs encoded by gene and its potential application as a protective agent against photodamage [

11].

In another study conducted on the skin secretions of

Odorrana andersonii, a peptide named OA-GL21 (GLLSGHYGRVVSTQSGHYGRG) was identified, which demonstrated weak antioxidant activity through ABTS

•+ and DPPH free radical scavenging methods, although it exhibited high stability. However, this peptide significantly enhanced wound healing in human keratinocytes and fibroblasts in a dose- and time-dependent manner. In conclusion, this research demonstrated the effects of OA-GL21 on cellular and animal wounds and provided a novel template peptide for the development of wound repair drugs [

78].

Temporin Family

From a large group of AOP and AMP families present in three East Asian frog species (

Amolops lifanensis, Hylarana taipehensis and

Amolops granulosus), the peptides temporin-TP1 (FLPVLGKVIKLVGGLL-NH

2), temporin-TP2 (FLPLLVGAISSILPKIF-NH

2) and temporin-TP3 (FLPLLFGALSTLLPKIF-NH

2) were found from

H. taipehensis; temporin-LF1(FLPFVGKLLSGLL-NH

2) and temporin-LF2 (FLPIVTGLLTSLL-NH

2) from

A. lifanensis; temporin-1P (FLPIVGKLLSGLL-NH

2) and temporin-MT1 (FLPIVTGLLSSLL-NH

2) from the species

A. lifanensis and

A. granulosus; and temporin-CG3 (FLPIVGKLLSGLF-NH

2) only from the species

A. granulosus. Temporin-TP1 peptide exhibited the ability to scavenge ABTS

•+ and/or DPPH radicals [

8,

62]. Although temporin-TP1 did not show obvious antimicrobial activity against some microorganisms, it had strong antimicrobial activity (with MIC=3.1mM) against Gram-positive bacteria:

Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923),

Enterococcus faecalis 981 (IS), and

Nocardia asteroides 201118 (IS) [

32].

In a study that identified 50 peptides grouped into 21 peptide families exhibiting antioxidant and antimicrobial activity from

Amolops daiyunensis, Hylarana maosuoensis, Pelophylax hubeiensis, and

Nanorana pleskei, the AMPs temporin-DY1, temporin-HB1, temporin-HB2, temporin-MS1, and temporin-MS4 were found, varying significantly in their activities due to the great variety of peptide structures they present. Of the peptides found, temporin-MS1 (FLTGLIGGLMKALGK) was synthesized and showed a slight ABTS

•+ free radical scavenging capacity, with 21.4 ± 2.2% eradication rates. In the antimicrobial activity results, temporin-MS1 showed activity against different Gram-positive strains such as

Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923),

Enterococcus faecalis 981 (IS), and

Nocardia asteroides 201118 (IS), as well as Gram-negative strains such as

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CGMCC 1.50),

Klebsiella pneumoniae 08040724 (IS), and

Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922). However, peptides temporin-MS1 and temporin-MS4 showed the most muscular hemolytic activity, which presents an undesirable effect associated with these peptides [

74].

Daiyunin and Pleskein Families

The daiyunin family is a group of peptides found in

Amolops daiyunensis, an East Asian frog species from China. Here were identified daiyunin-1 (CGYKYGCMVKVDR), daiyunin-2 (FFGTKGIFSKVEPIFCKISHSC), and daiyunin-3 (IVRPPIRCKAAFC). Among these, daiyunin-1 exhibited significant results in the antioxidant and antimicrobial assays. At a concentration of 50 μM, the scavenging ability of daiyunin-1 against ABTS

•+ and DPPH radicals within 30 minutes of the reaction was low, but its scavenging rate against ABTS

•+ reached 77.1% when the reaction time was prolonged to 14 hours. In the same study, from

Nanorana pleskei, an East Asian frog species from China, pleskein-1 (FFPLIPGVRCKILRTC), pleskein-2 (FFLLPIPNDVKCKVLGICKS), and pleskein-3 (ILPSKLCRLLGNC) were reported. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity assays showed that pleskein-1 and pleskein-2 have relatively weak antimicrobial activities, and only pleskein-2 has specific antioxidant activity (11.3% in an ABTS assay after 30 minutes at 50 μM). Pleskein-3 did not show any antimicrobial or antioxidant activity; however, it is inferred that pleskein-3, by sharing the same precursors with AMP or AOP, may possess other functions that help frogs adapt to their living environments [

74].

Jindongenin Family

This family was reported about the Chinese torrent frog

Amolops jingdongensis. One of its components is a 24-amino-acid peptide, jindongenin-1a (DSMGAVKLAKLLIDKMKCEVTKAC), tested for various activities, including antioxidant activity. Jindongenin-1a showed broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against standard and clinically isolated bacterial strains. However, DPPH free radical scavenging assays indicated that jindongenin-1a exhibited low antioxidant activity at doses up to 32 mM (8% inhibition). The results suggest that these peptides do not play a key role in the habituation of

A. jingdongensis to intense UV exposure [

34].

Tryptophilins Family

As for tryptophilins, they are one of the first peptides identified in amphibians’ skin secretions. They are characterized as a heterogeneous group of peptides that were recently reclassified according to their structures into the following groups: T-1 (

C-amidated heptapeptides and non-amidated octapeptides that have an

N-terminus formed by Lys and Pro residues, a Trp residue at position 5, and a Pro residue at position 7), T-2 (four to seven amino acid residues, which have an internal Pro-Trp), and T-3 (tridecapeptides with five conserved Pro residues and the absence of Trp) [

58]. Tryptophilins have been commonly associated with myoactive and vasorelaxation/vasoconstriction properties [

58,

60], opioid-like biological activities [

59], antiproliferative effects [

60], and antimicrobial actions [

40,

79].

Recent studies have found tryptophilin-like peptides with antioxidant potential in frogs of the species

Pithecopus azureus [

46] and

Pelophylax perezi [

80]. For

P. azureus, the amidated antioxidant peptide PaT-2 (FPPWL-NH

2) and its respective analogs PaT-2a1 (FPLPW-NH

2) and PaT-2a2 (PWLFP-NH

2) were reported [

46] . For

P. perezi, the also amidated antioxidant peptide PpT-2 (FPWLLS-NH

2) was reported, which demonstrated significant antioxidant potential for tryptophilin-like peptides [

80]. The results of the analysis of peptides PaT-2 and its analogs (PaT-2a1 and PaT-2a2) showed antioxidant activity and low cytotoxicity in mammalian central nervous system cells such as mouse BV2 microglia and human neuroblastoma cells SK-N-BE(2), which were stimulated with the diester phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and treated simultaneously with PaT-2, PaT-2a1, or PaT-2a2 at concentrations of 50 µM and 100 µM. ROS and RNS were detected before and after flow cytometry analysis for these cells, showed significant differences compared to control cells treated only in DMEM medium. Additionally, morphological and histological analyses of the skin to identify the glands of

P. azureus, as well as the results of the in silico and in vitro radical scavenging tests, allowed verification of the possible relationship between PaT-2 and oxidative protection, leading the authors to conclude that they had identified, for the first time, a tryptophilin-like peptide with antioxidant potential [

46].

On the other hand, the results from analysis of the antioxidant peptide PpT-2 were measured based on the mechanism of action of these compounds, as it generally involves a series of complex processes for deactivating and trapping free radicals. These processes include the transfer of relevant charges and the antioxidant activities of biological systems. Therefore, the possible antioxidant properties of PpT-2 were measured through its ability to eliminate ABTS and DPPH radicals in vitro, using Trolox and GSH as a reference compound and as a reference antioxidant peptide, respectively. The results showed that PpT-2 had an ABTS scavenging activity of 0.269 mg.trolox-eq.mg

-1 of peptide, which is comparable to that of other amphibian-derived peptides such as salamandrin-I (FAVWGCADYRGY-NH

2) with values of 0.285 mg.trolox-eq.mg-1 of peptide, and antioxidin-RP1 (AMRLTYNKPCLYGT) with values of 0.300 mg.trolox-eq.mg

-1 of peptide. These values are higher than the activity of antioxidant-I (TWYFITPYIPDK) with values of 0.010 mg.trolox-eq.mg

-1 of peptide [

47] but much lower than that of glutathione (1.911 mg.trolox-eq.mg

-1 of peptide). These results indicate that PpT-2 has free radical scavenging activities, with the most robust and potent activity against ABTS radicals. The neuroprotective activity of PpT-2 was also evaluated in mammalian cells, specifically mouse (

Mus musculus) microglia, which respond to tissue damage and infection by producing and releasing ROS and RNS into the surrounding central nervous system (CNS) environment. Mouse microglial cells (BV-2) were stimulated with PMA, a chemical known to induce ROS and RNS production, either in the presence or absence of PpT-2 at the two different concentrations. PMA activates protein kinase C, phosphorylating p47phox to activate NADPH oxidase (NOX), ultimately leading to increased ROS generation. The results indicated that at the tested concentrations, PpT-2 effectively inhibits oxidative stress in BV-2 cells during the 30 minutes of simultaneous incubation with PMA, occurring right at the onset of treatment. Furthermore, PpT-2 inhibits RNS generation even in cells not stimulated by PMA, suggesting that this inhibition occurs under basal conditions. The results showed that PpT-2 regulates the steady-state levels of both ROS and RNS through its antioxidant effects. Thus, this tryptophilin shows promise as a therapeutic agent for treating or preventing neurodegenerative disorders due to its antioxidant activity in microglia and the role of redox imbalance in the onset and progression of diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s. Despite the number of tryptophilins known, this is the first study to verify this bioactivity and therapeutic potential for PpT-2 [

80].

3. Amphibian AOPs and Oxidative Stress-Related Diseases

Research has shown that peptide’s antioxidant activity is influenced by its amino acid type and sequence. Amphibian-derived AOPs can scavenge oxygen free radicals, activate the antioxidant enzyme system, inhibit DNA damage and apoptosis, and regulate the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway. However, their precise functions remain unclear [

4]. Studies of model peptides suggest that any peptide satisfying the appropriate hydrophobicity and cationic criteria and capable of adopting amphipathic-helical conformation will display at least some antimicrobial [

81], and antioxidant activity [

8]. Furthermore, research on AOPs from Asian amphibians has shown that these peptides have precursors similar to AMPs [

8,

62], and many mature AOPs also exhibit antimicrobial activities, demonstrating a close evolutionary relationship [

32], and maybe a similar mechanism of action. Additionally, it is well established that OS significantly impacts cell homeostasis and that excess ROS are linked to various diseases. While the pathophysiology of conditions such as cancer, neurodegenerative disorders (NDs), and cardiovascular diseases differ, OS remains a common factor among them [

82]. By scavenging free radicals, AOPs may prevent or mitigate OS and help restore redox balance, which is crucial for treating these complex diseases. OS is known to cause damage to cellular components, inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction and activation of cell death pathways in many NDs, or even resistance to cell death in cancers (

Figure 1) [

83,

84,

85,

86]. Therefore, given the importance of antioxidant treatments in this context, we will reference reports of amphibian AOPs with antioxidant activities and other mechanisms of action evaluated directly against OS-related diseases in this section.

The brain’s physiology makes it considerably more susceptible to OS damage. Its high energy demand, high oxygen consumption, high polyunsaturated fatty acid content, and excessive iron concentration are reasons for that susceptibility [

87]. This increased sensitivity to OS makes antioxidants an essential adjunct in ND treatment, and there are reports of the potential of amphibian AOPs with neuroprotective effects. Brevinin-1FL, an AOP from the skin of

Fejervarya limnocharis, exhibited excellent antioxidant activity in vitro through its high reducing power and radical scavenging activities, as well as anti-inflammatory potential by reducing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and increasing levels of antioxidant enzymes. Brevinin-1FL also presents neuroprotective effects, since as it was able to reverse the H

2O

2-induced changes in PC-12 cells [

73]. PaT-2, a peptide from

Pithecopus azureus, prevented oxidative stress in the human microglia cell model by hampering lipopolysaccharide-induced ROS, as well as glutamate release, which is known to influence neuronal cell death [

46]. These results support amphibian AOP as a potential source of molecules to aid in ND treatment since microglial cells are important targets for antioxidant treatments because OS and inflammation related to these cells play important essential roles in NDs such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and others [

88,

89].

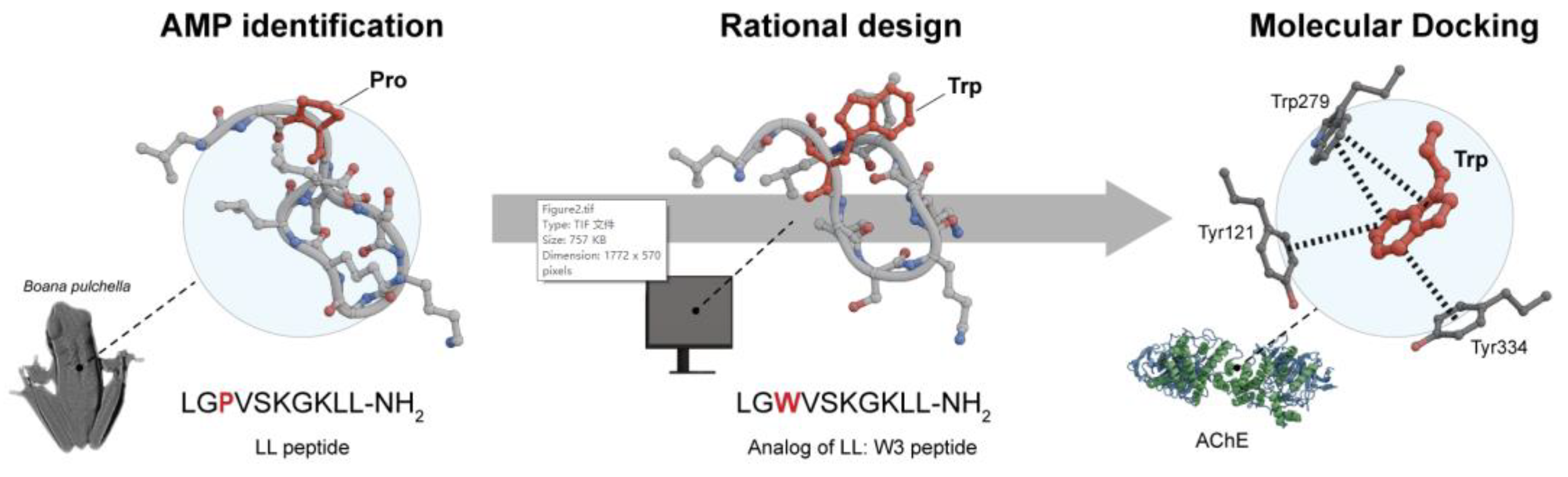

AD is the most common ND and presents several hallmarks targeted for drug discovery, such as the formation of amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques, tau protein depositions, and altered acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity. The use of AChE inhibitors, including antioxidants and multi-target compounds, is one the primary strategies for combating AD, as most drugs prescribed for AD treatment act by inhibiting AChE [

90]. Additionally, there are reports of AOPs exhibiting in vitro activities against pathways related to AD. A study on peptide skin extracts from three different amphibian families in the Argentinean Litoral region found that five out of nine evaluated extracts had the potential to act on four critical pathways of AD: inhibition of AChE and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), which are responsible for low levels of acetylcholine in AD, and monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B), known to improve AD symptoms, as well as exhibiting antioxidant potential due to free radical scavenging activity [

91]. More recently, this same group also reported that the natural peptide Bcl-1003 (GSKKTKCPR-NH

2), isolated from the skin of

Boana cordobae, inhibits both BChE and MAO-B and exhibits antioxidant activity [

92]. Among AChE inhibitors, those that target the peripheral anionic site (PAS) are of great interest. In one study, a 10-amino acid peptide called LL (LGPVSKGKLL-NH

2) was derived from a more prominent natural sequence called Hp-1935, isolated from the skin secretions of the Argentine frog

Boana pulchella, which exhibits PAS inhibitory activity [

93]. Since peptide LL is a PAS inhibitor, it was complexed with AChE through a flexible docking study, the results were corroborated with 100 ns of MD simulations. The LL-AChE complex involves three critical residues of the PAS (Tyr-70, Trp-279, and Tyr-334), all interacting through hydrophobic interactions with Pro-3 in peptide LL. Because Pro-3 was influential in the docking analysis, a rational design and synthesis of LL peptide analogs based on the substitution of Pro-3 alone, or Pro-3 and aliphatic residues, such as Gly-7 in the

C-terminus, with aromatic amino acids (Trp, Tyr, Phe, and 4-fluoro-Phe) was proposed to form π–π stacking interactions with the aromatic residues of the PAS. Finally, the authors compared the inhibitory and antioxidant properties of the new sequences with LL to evaluate the effect of the modifications. Among the analogs, peptide W3 (LGWVSKGKLL-NH

2) has an IC

50 of 10.42 μM and was found to exhibit a 30-fold enhancement in AChE inhibitory activity, along with antioxidant activity, making it one of the most potent against this Alzheimer’s-related enzyme. Additionally, it was observed that W3 interacts with AChE in the same region as peptide LL, specifically the PAS. MM analysis indicated that Trp-3 of W3 is located close to the three critical residues of the PAS site throughout the simulation time, where the indole side chain of W3 is sandwiched between residues Tyr-121, Trp-279, and Tyr-334 of the PAS through aromatic-aromatic stacking interactions (

Figure 2) [

94].

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is caused by the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain region, also known as the substantia nigra, characterized by the accumulation of α-synuclein [

95,

96,

97]. Studies show that excessive ROS leads to the oxidation of macromolecules, including lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, and their accumulation in the brain tissues of Parkinson’s patients, causing local or systemic damage and promoting dopaminergic neural degeneration [

97,

98]. The previously mentioned AOP, PpT-2, has electron donation and acceptance capacity similar to other antioxidants, eliminates free radicals, and inhibits PMA-induced OS. It has also demonstrated neuroprotective potential in vitro on mouse microglial cells (BV-2) by controlling the levels and steady state of ROS and RNS. Therefore, PpT-2 could be a promising therapeutic agent for AD and PD [

80]. Another study described Cath-KP, a peptide that belongs to the cathelicidin family, extracted from the skin of the Asian-painted frog

Kaloula pulchra. Cath-KP penetrates cells and reaches deep brain tissues, resulting in improved cell viability even when treated with 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), and it reduces OS-induced damage by inducing the expression of antioxidant enzymes and alleviating the accumulation of mitochondrial and intracellular ROS. In mice with PD induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), there was an increase in tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-positive neurons, improving dyskinesia. Thus, this demonstrates that Cath-KP can prevent damage caused by OS due to its antioxidant and neuroprotective properties [

71].

Mitochondria play a crucial role in apoptosis, a programmed cell death process, and MAPK signaling pathways can act as either activators or inhibitors of apoptosis. Tests with antioxidant peptides in cell lines have allowed us to identify some mechanisms of action that demonstrate their effect on signaling pathways involved in cell proliferation and translocation to mitochondria. For example, peptide OA-VI12 (VIPFLACRPLGL), identified in the frog

Odorrana andersonii [

11], can regulate the MAPK signaling pathway [

99], which is usually activated by oxidative stress and is related to cell proliferation and migration, signal transduction, inflammation, collagen synthesis, and apoptosis. Additionally, in the research on apoptotic mechanisms of AOPs, it is commonly expected to detect levels of crucial apoptotic proteins, gene expression of Bcl-2 family proteins, and the translocation of cytochrome C (Cyt C) into mitochondria and the cytoplasm [

100]. OM-GL15 (GLLSGHYGRASPVAC) from the skin of the green odorous frog

Odorrana margaretae, is an AOP that protects epidermal cells from apoptosis, significantly attenuating UVB radiation-induced skin photodamage in mice by reducing lipid peroxidation and malondialdehyde levels through upregulation of Bcl-2, inhibition of DNA damage, and downregulation of caspase-3, caspase-9, and Bax [

31]. Antioxidin-RL (AMRLTYNRPCIYAT) can regulate the accumulation of free radicals and the expression of superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD1) and glutathione peroxidase-1 (GPx1) in rat PC-12 cells, where oxidation was induced with H

2O

2, while maintaining mitochondrial morphology to ensure cellular metabolism [

74]. Similarly, brevinin-1FL was able to reverse H

2O

2-induced oxidation in a cell-dependent manner in PC-12 cells, suggesting a protective effect against H

2O

2-induced damage to the mitochondrial membrane [

73]. As mentioned above, peptides containing Pro and Cys are associated with the ability to eliminate oxygen free radicals, as is the case with this peptide that regulates the redox environment in mammalian cells [

66]. OA-VI12, OM-GL15, and antioxidin-RL contain these amino acids.

Several reports of amphibian peptides describe activity against numerous cancers, with most exhibiting antitumor activity by killing cells, affecting proliferation, modulating the immune system, or inhibiting angiogenesis [

101]. There is a well-established and widely described relationship between OS and cancer in the literature [

86,

102], demonstrating that OS can lead to DNA damage and consequent mutations, overactivation of signaling pathways related to cell growth and proliferation, modulation of the tumor microenvironment, and promotion of cell survival and resistance to therapies [

103,

104,

105,

106]. Therefore, in theory, controlling OS seems to be an essential step not only for cancer treatment but also for prevention since chronic OS can favor tumor growth and progression [

107]. However, there are still some limitations regarding using antioxidants for cancer treatment. Some key issues may influence the low efficacy of antioxidants in clinical practice. First, reliance on pharmacological doses in studies rather than dietary doses does not accurately reflect in vivo conditions. Additionally, antioxidants may not be evenly distributed throughout the body. They can have low bioavailability in specific tissues, and their effects can also vary depending on concentration and oxygen levels, shifting between antioxidant and pro-oxidant properties. Finally, since many chemotherapy drugs generate ROS, antioxidants could potentially interfere with the effectiveness of these treatments, undermining their ability to induce cancer cell death [

108].

Although there are many controversies, acknowledging these limitations might help optimize the design of assays and studies in which adding antioxidants could be advantageous. Additionally, drug delivery strategies, such as nanoparticles, are alternatives that could help overcome some of these issues [

109,

110]. The development of new cancer therapies is necessary not only to help overcome resistance problems but also to improve the quality of life for cancer patients, relieving symptoms and perhaps even preventing recurrence. Different antioxidant molecules might present distinct results, so searching, characterizing, and evaluating new antioxidant molecules and sources, such as amphibian AOPs, may constitute a possibility for developing adjunctive cancer treatments, but further investigation is necessary.

The skin is regularly exposed to OS from endogenous and exogenous sources. Air pollution, chemicals, microorganisms, toxins, harmful natural gases, and ionizing and non-ionizing radiation are examples of exogenous agents that contribute to ROS generation and consequent OS in the skin [

109,

110]. Maintaining skin homeostasis is essential and particularly challenging, mainly due to its significant exposure to UV radiation, which does not affect other organs [

110]. UV radiation impacts both the skin’s structure and functionality, and excessive exposure can result in immediate and long-lasting harmful effects, including photodamage, premature aging, and an increased risk of skin cancer [

111,

112].

OS-LL11 (LLPPWLCPRNK) was identified from

Odorrana schmackeri. This AOP can scavenge free radicals and exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic properties. In vitro, results demonstrated that the peptide was able to preserve the cell viability of mouse keratinocytes treated with UVB irradiation or H

2O

2 by diminishing harmful effects such as lipid peroxidation and ROS while increasing the levels of CAT and other important essential proteins involved in cellular responses to oxidative stress and regulation of antioxidant defenses. OS-LL11 activity was also evaluated in vivo, and the photoprotective effects on mouse skin occurred due to upregulation of superoxide dismutase, glutathione, and nitric oxide levels, as well as a reduction in the number of apoptotic bodies and downregulation of H

2O

2, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and other proteins involved in OS and apoptosis [

113].

The activity of the AOP, OA-GI13 (GIWAPWPPRAGLC), identified from

Odorrana andersonii, was described as exhibiting free-radical scavenging activity and was able to maintain keratinocyte viability under treatment with H

2O

2 by protecting cell membrane integrity, as evidenced by reduced lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels in the presence of the peptide, and also due to the stimulation of SOD, CAT, and GSH release [

112]. The activity of OA-GI13 was also tested in mice. The peptide exhibited photoprotective action against UVB radiation exposure, as evidenced by decreased erythema, edema, and reduced levels of OS markers like peroxide. Another mechanism by which the peptide exerts antioxidant activity was observed in vitro and in vivo. The inhibition of p38 phosphorylation upon OA-GI13 treatment suppresses the p38 MAPK signaling pathway and prevents ROS production. Other studies describe amphibian AOPs with photoprotective activity, which supports their applicability since they recover redox balance and even prevent UV radiation’s detrimental effects by maintaining homeostasis. Their potential against acute symptoms is established, and they constitute a basis for further investigation regarding protection against chronic effects of UV exposure, such as skin cancer and aging [

11,

63,

114].

Skin regeneration is another process of interest in drug development, as it is crucial for maintaining homeostasis and is also affected by diseases. Amphibians, due to their high wound-healing capacity (Campbell and Crews, 2008) and ability to regenerate limbs or tails, especially in young animals, are promising sources of molecules with regenerative properties. There are many reports of amphibian-derived wound-healing peptides [

115], but only one, to our knowledge, with both antioxidant and regenerative activity. Cathelicidin-OA1, previously mentioned in this review, was the first amphibian peptide of the cathelicidin group to show solid wound-healing activity. In vitro, it improved wound healing in human keratinocytes and fibroblasts. In vitro, it improved wound healing in human keratinocytes and fibroblasts. In vivo, the peptide increased macrophage recruitment to the wound site, stimulating cell proliferation and migration, leading to an increase in re-epithelialization and formation of granulation tissue [

69]. Since OS interferes with wound repair, cathelicidin-OA1 promotes regeneration, directly facilitating the healing process and enhancing repair capacity through its antioxidant activity

.

As previously discussed, OS is a common factor among various diseases. In this review, we focused on conditions for which amphibian AOPs or amphibian peptides have already been reported; however, their evaluation against other OS-related diseases is also valid. Other neurodegenerative disorders, such as Huntington’s disease (HD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), are greatly affected by OS, as are cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. There are reports of peptides with antioxidant activity from different sources with multifunctional properties, i.e., AOPs displaying multiple activities that can be of interest for treating multifactorial diseases [

116,

117].