Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

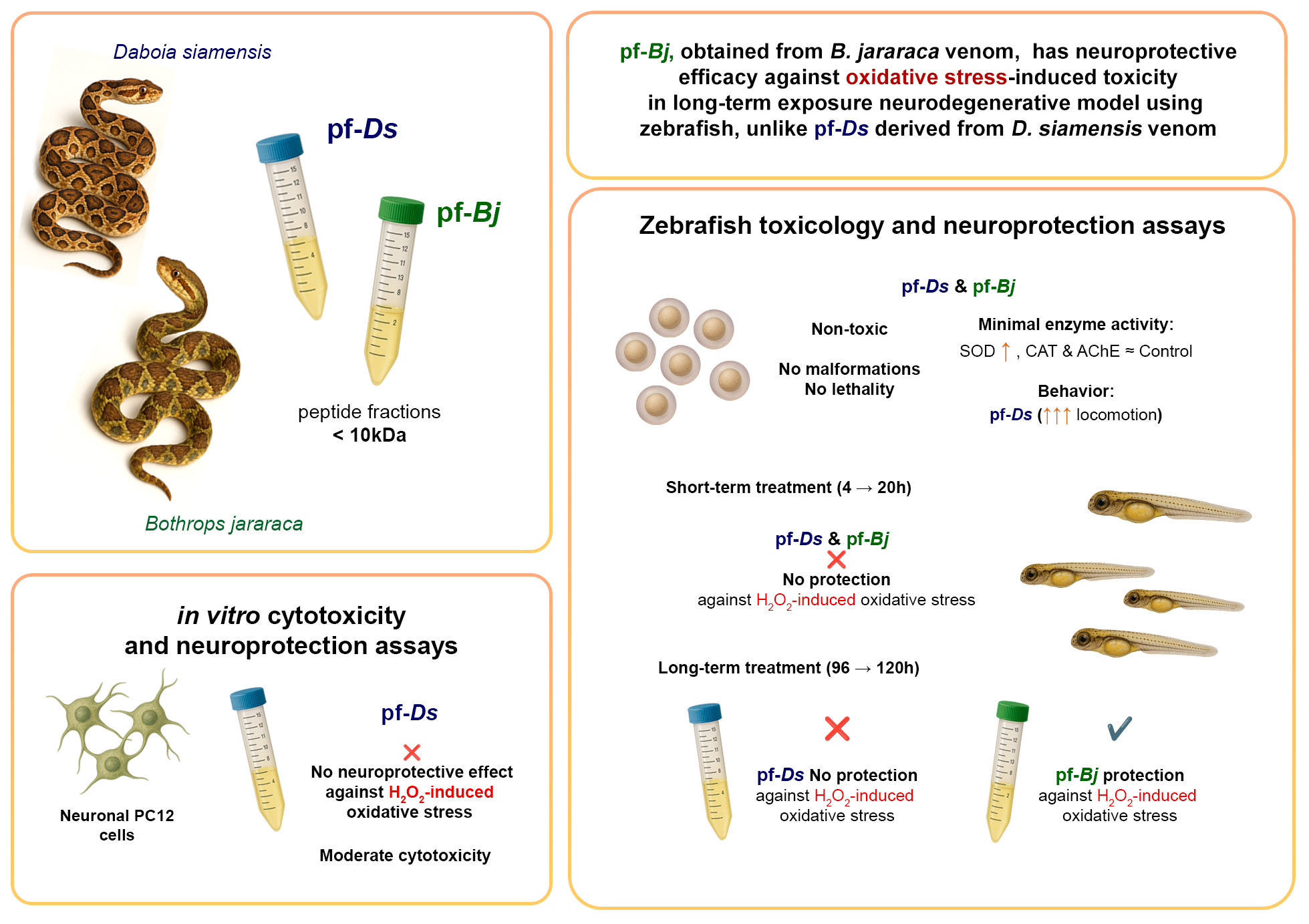

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

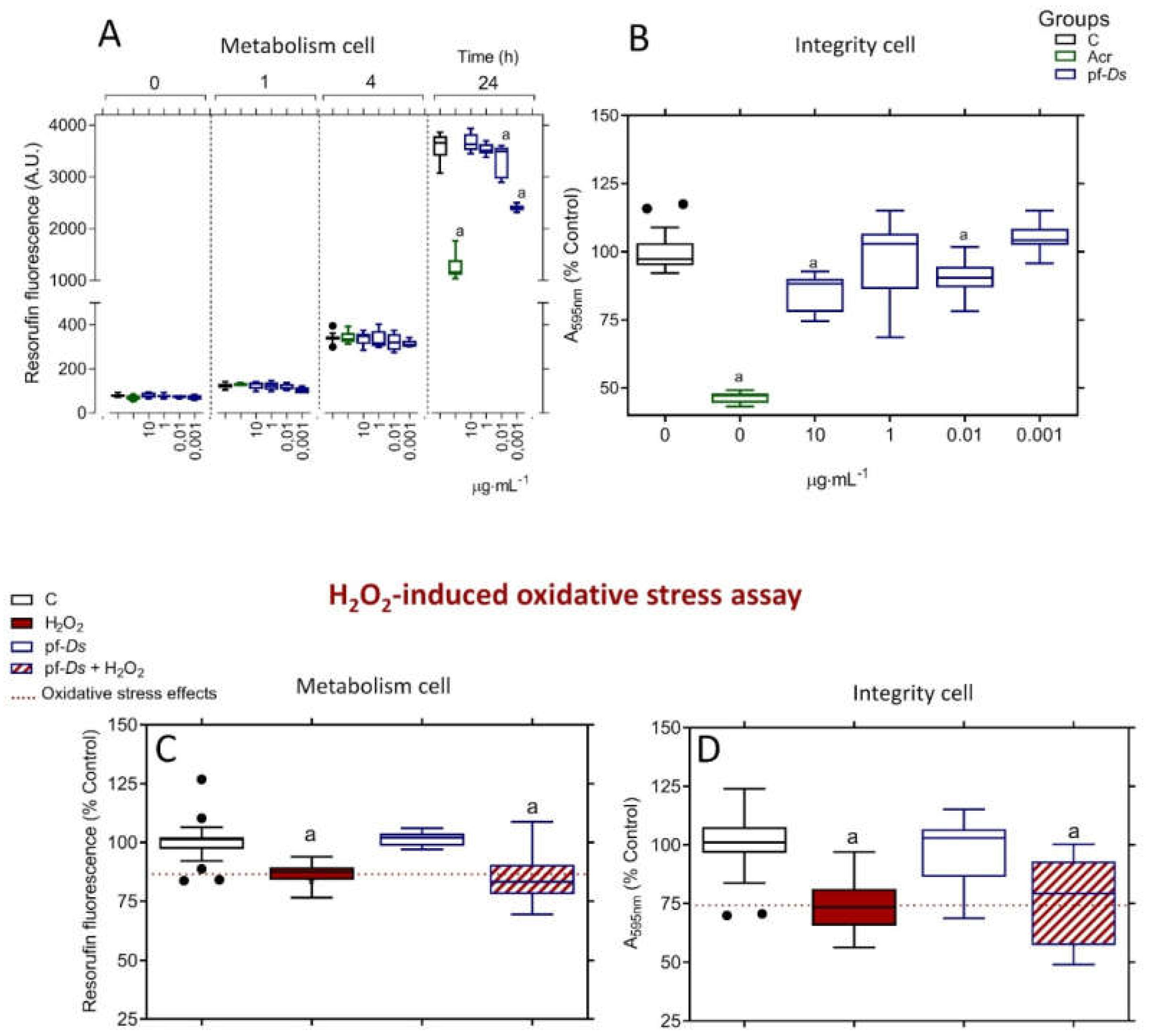

2.1. Toxicological and Neuroprotective Effects of pf-Ds in PC12 Cells

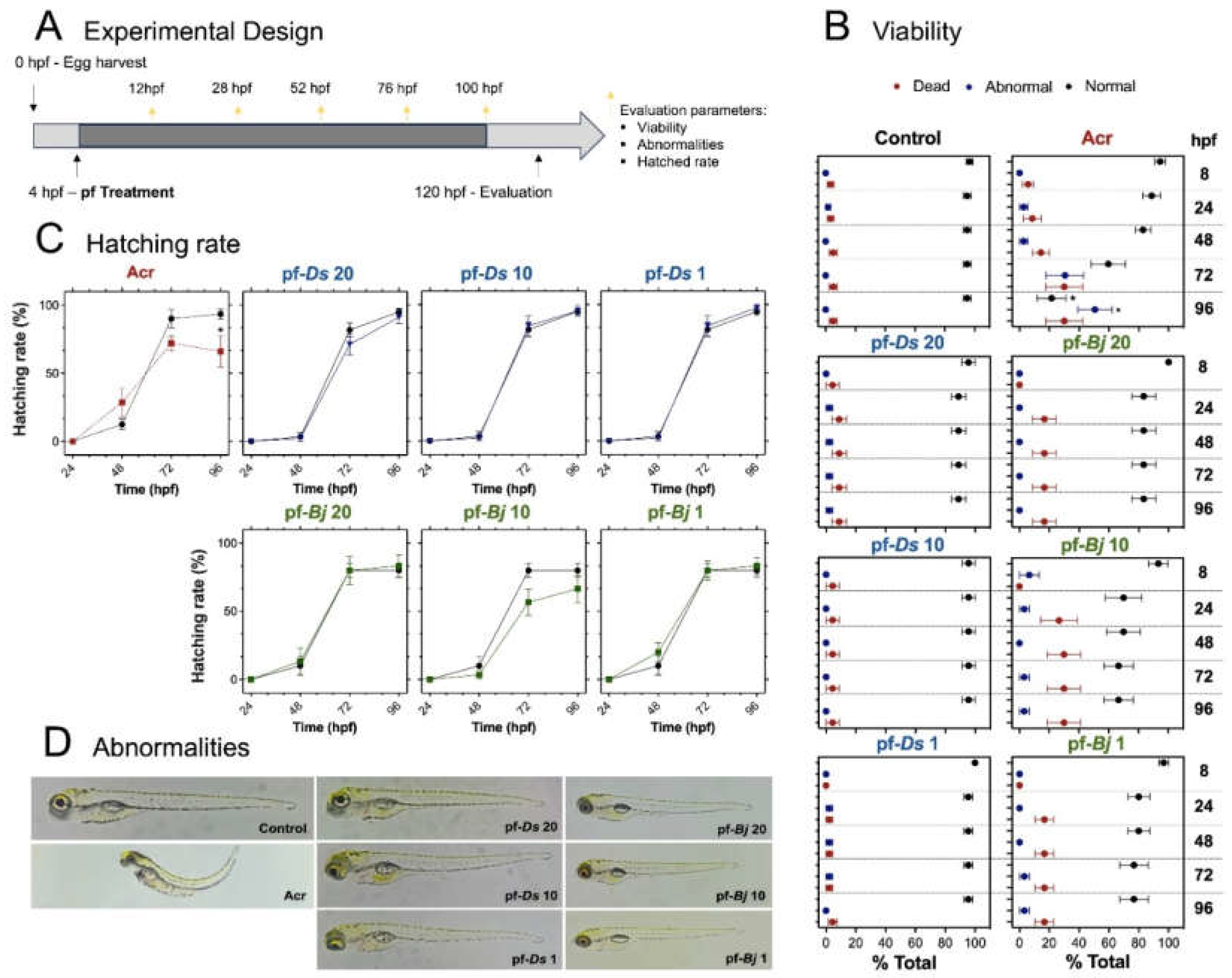

2.2. Toxicological Effects of pf-Ds and pf-Bj on Zebrafish Development

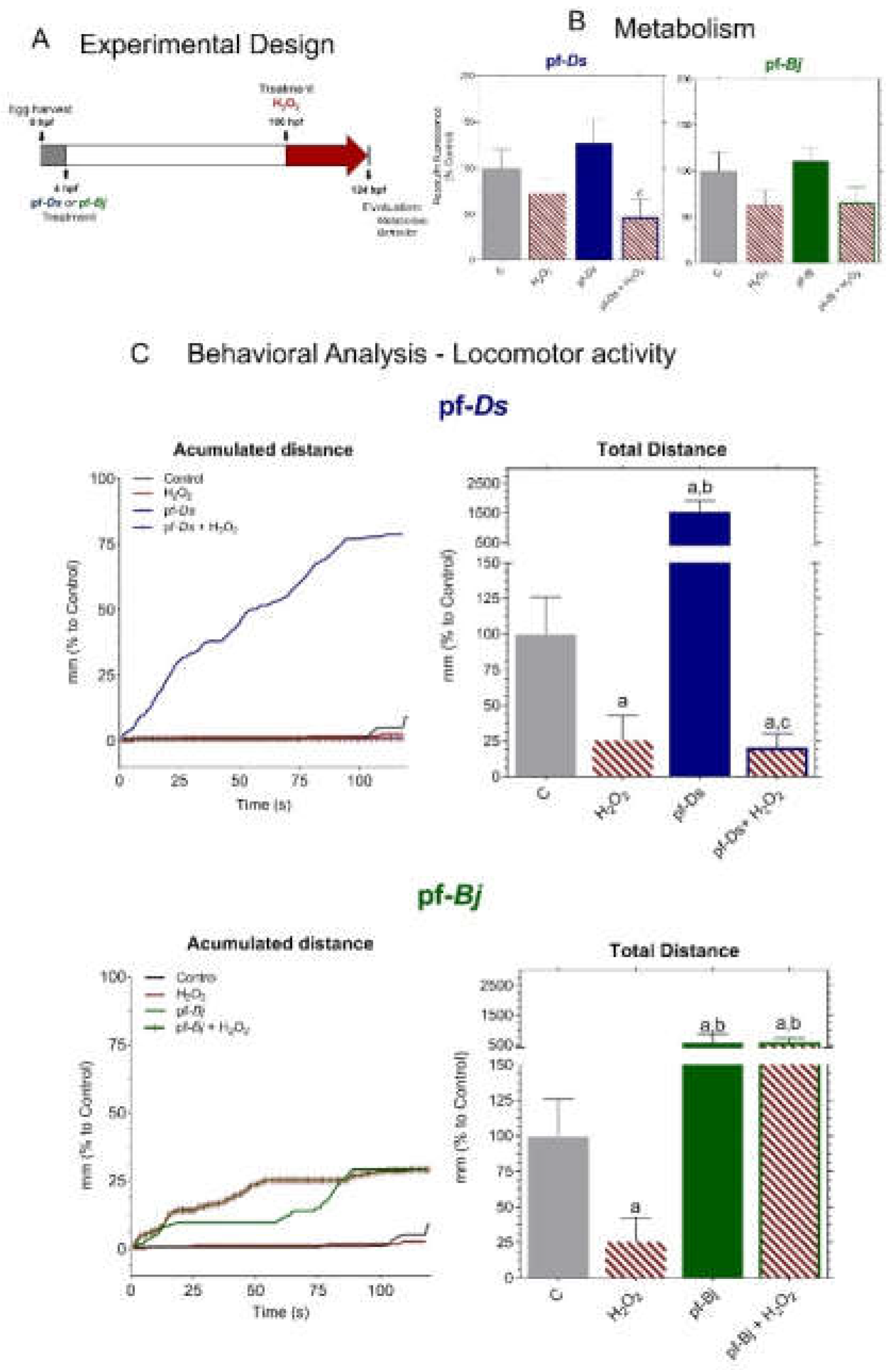

2.3. Neuroprotective Effects of pf-Ds and pf-Bj Against H₂O₂-induced Oxidative Stress in Zebrafish Embryos in 4-20 hours Model

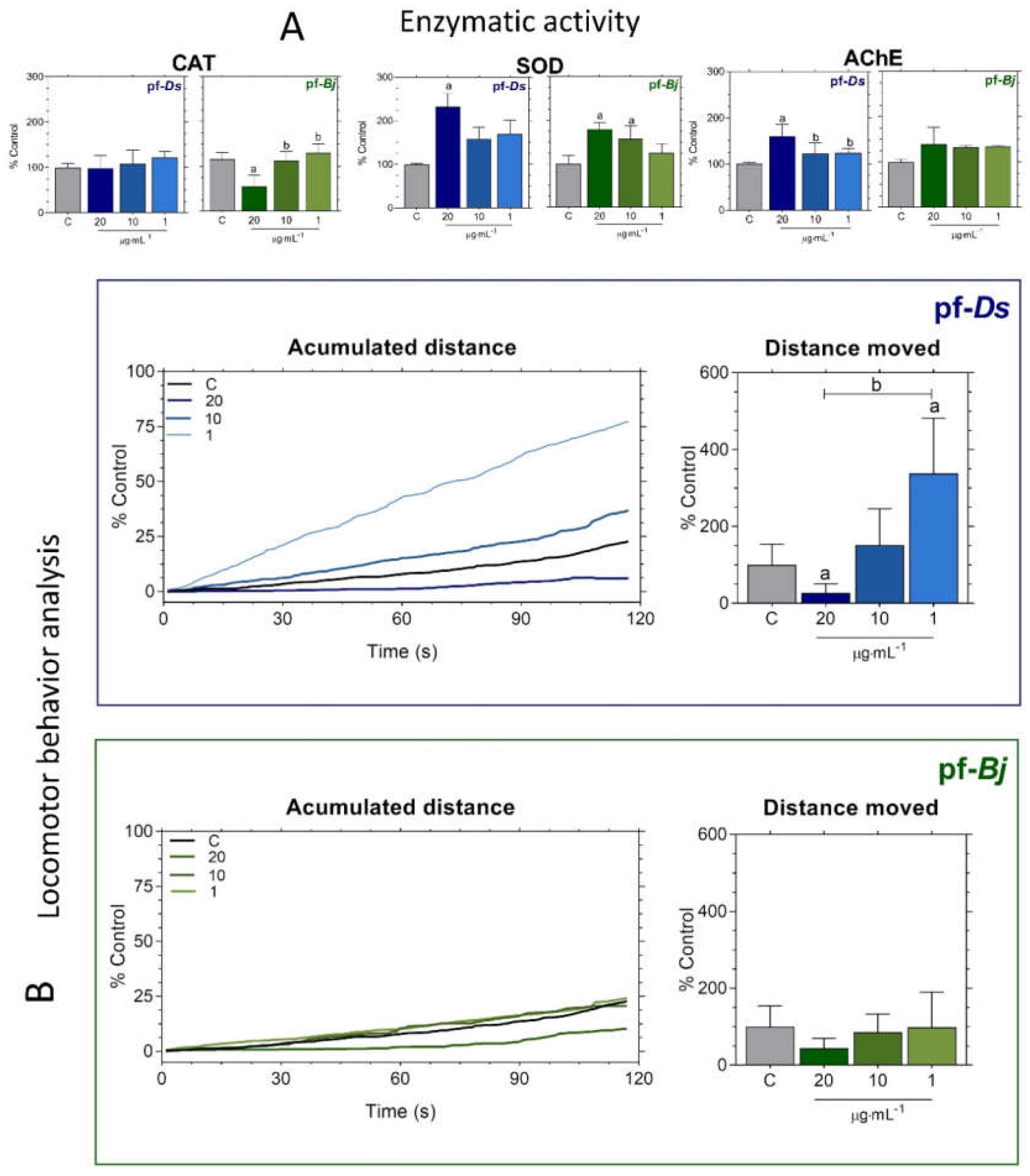

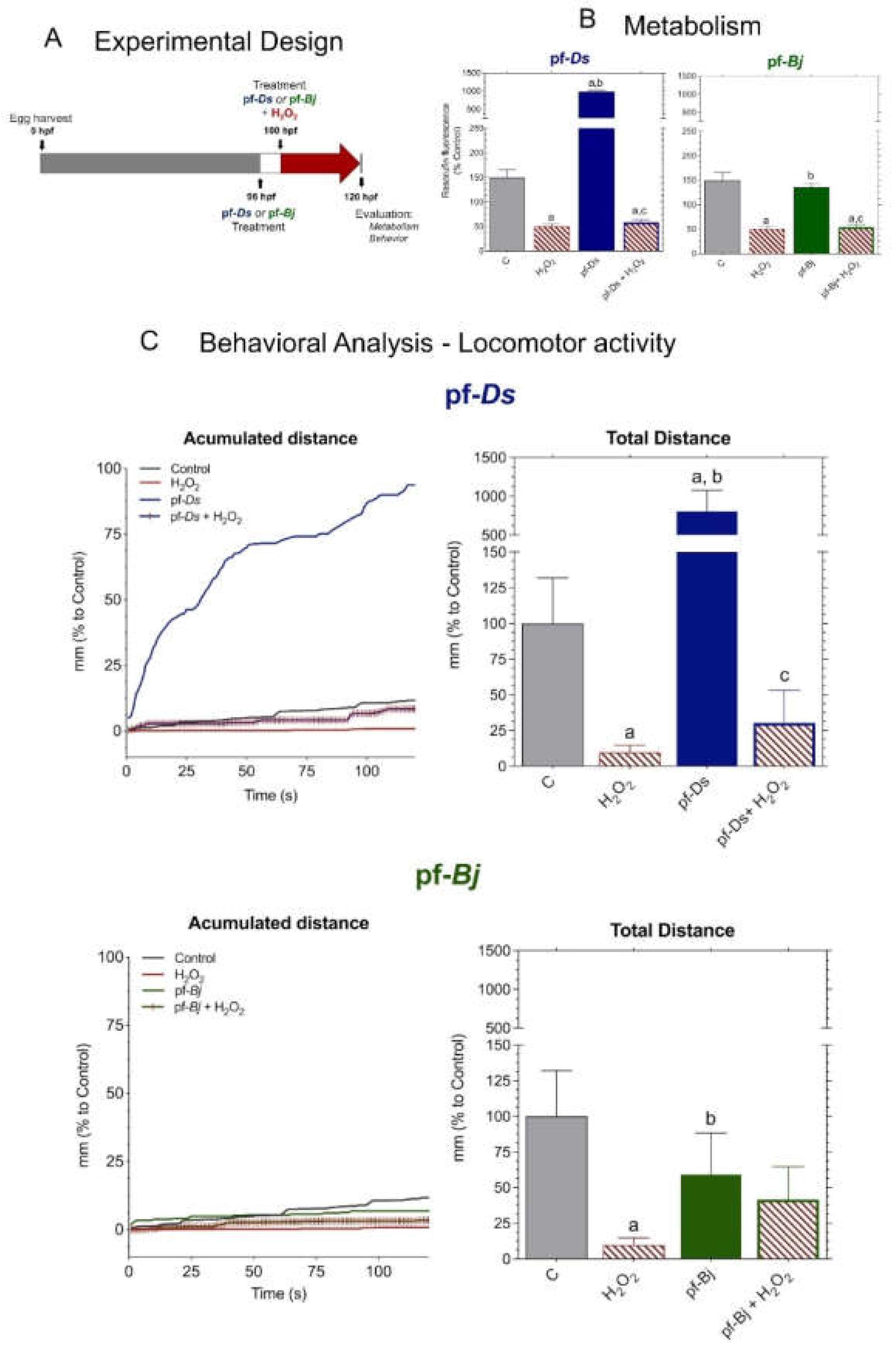

2.4. Neuroprotective Effects of f-Ds and pf-Bj Against H₂O₂-Induced Oxidative Stress in Zebrafish Embryos in 96-120 hours Model

3. Discussion

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Reagents and Peptide Fraction of D. siamensis and B. jararaca Venom

4.2. Cell Lines and Maintenance

4.2.1. Toxicity Studies in Neuronal Cell Lines

4.2.2. Neuroprotection Assay Against H₂O₂-Induced Oxidative Stress

4.3. Zebrafish Maintenance, Husbandry, and Egg Collection

4.3.1. Monitoring of Zebrafish Development

4.3.2. Neuroprotection Assay Against H₂O₂-Induced Oxidative Stress

4.3.4. Behavior Analysis

4.4. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Ethical Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nguyen, T.; Nioi, P.; Pickett, C.B. The Nrf2-Antioxidant Response Element Signaling Pathway and Its Activation by Oxidative Stress. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2009, 284, 13291–13295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbate, F.; Maugeri, A.; Laurà, R.; Levanti, M.; Navarra, M.; Cirmi, S.; Germanà, A. Zebrafish as a Useful Model to Study Oxidative Stress-Linked Disorders: Focus on Flavonoids. Antioxidants 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.; Slikker, W.; Ali, S.F. Age-Related Changes in Antioxidant Enzymes, Superoxide Dismutase, Catalase, Glutathione Peroxidase and Glutathione in Different Regions of Mouse Brain. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience 1995, 13, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.; Tan, B.K. Bioactive Peptides from Marine Organisms. Protein Pept Lett 2024, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberto-Silva, C.; da Silva, B.R.; da Silva, J.C.A.; Cunha e Silva, F.A. da; Kodama, R.T.; da Silva, W.D.; Costa, M.S.; Portaro, F.C.V. Small Structural Differences in Proline-Rich Decapeptides Have Specific Effects on Oxidative Stress-Induced Neurotoxicity and L-Arginine Generation by Arginosuccinate Synthase. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.; Disner, G.R.; Falcão, M.A.P.; Seni-Silva, A.C.; Maleski, A.L.A.; Souza, M.M.; Tonello, M.C.R.; Lopes-Ferreira, M. The Natterin Proteins Diversity: A Review on Phylogeny, Structure, and Immune Function. Toxins (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boix, N.; Teixido, E.; Pique, E.; Llobet, J.M.; Gomez-Catalan, J. Modulation and Protection Effects of Antioxidant Compounds against Oxidant Induced Developmental Toxicity in Zebrafish. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberto-Silva, C.; Pantaleão, H.Q.; da Silva, B.R.; da Silva, J.C.A.; Echeverry, M.B. Activation of M1 Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors by Proline-Rich Oligopeptide 7a (<EDGPIPP) from Bothrops Jararaca Snake Venom Rescues Oxidative Stress-Induced Neurotoxicity in PC12 Cells. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins Including Tropical Diseases 2024, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantaleão, H.Q.; Araujo da Silva, J.C.; Rufino da Silva, B.; Echeverry, M.B.; Alberto-Silva, C. Peptide Fraction from B. Jararaca Snake Venom Protects against Oxidative Stress-Induced Changes in Neuronal PC12 Cell but Not in Astrocyte-like C6 Cell. Toxicon 2023, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querobino, S.M.; Carrettiero, D.C.; Costa, M.S.; Alberto-Silva, C. Neuroprotective Property of Low Molecular Weight Fraction from B. Jararaca Snake Venom in H2O2-Induced Cytotoxicity in Cultured Hippocampal Cells. Toxicon 2017, 129, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, C.B.; Ballard, W.W.; Kimmel, S.R.; Ullmann, B.; Schilling, T.F. Stages of Embryonic Development of the Zebrafish. Developmental Dynamics 1995, 203, 253–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalueff, A. V.; Stewart, A.M.; Gerlai, R. Zebrafish as an Emerging Model for Studying Complex Brain Disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2014, 35, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irons, T.D.; MacPhail, R.C.; Hunter, D.L.; Padilla, S. Acute Neuroactive Drug Exposures Alter Locomotor Activity in Larval Zebrafish. Neurotoxicol Teratol 2010, 32, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, A.J.; Teraoka, H.; Heideman, W.; Peterson, R.E. Zebrafish as a Model Vertebrate for Investigating Chemical Toxicity. Toxicological Sciences 2005, 86, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleski, A.L.A.; Rosa, J.G.S.; Bernardo, J.T.G.; Astray, R.M.; Walker, C.I.B.; Lopes-Ferreira, M.; Lima, C. Recapitulation of Retinal Damage in Zebrafish Larvae Infected with Zika Virus. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, J.G.S.; Lima, C.; Lopes-Ferreira, M. Zebrafish Larvae Behavior Models as a Tool for Drug Screenings and Pre-Clinical Trials: A Review. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALBERTO-SILVA, C.; SILVA, B.R. DA Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Neuroprotection by Oligopeptides from Snake Venoms. BIOCELL 2024, 48, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberto-Silva, C.; Portaro, F.C.V. Neuroprotection Mediated by Snake Venom. In Natural Molecules in Neuroprotection and Neurotoxicity; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 437–451. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, B.R.; Mendes, L.C.; Echeverry, M.B.; Juliano, M.A.; Beraldo-Neto, E.; Alberto-Silva, C. Peptide Fraction from Naja Mandalayensis Snake Venom Showed Neuroprotection Against Oxidative Stress in Hippocampal MHippoE-18 Cells but Not in Neuronal PC12 Cells. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervelli, M.; Averna, M.; Vergani, L.; Pedrazzi, M.; Amato, S.; Fiorucci, C.; Rossi, M.N.; Maura, G.; Mariottini, P.; Cervetto, C.; et al. The Involvement of Polyamines Catabolism in the Crosstalk between Neurons and Astrocytes in Neurodegeneration. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, M.; Datey, A.; Wilson, K.T.; Chakravortty, D. Dual Role of Arginine Metabolism in Establishing Pathogenesis. Curr Opin Microbiol 2016, 29, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamwal, S.; Kumar, P. Spermidine Ameliorates 3-Nitropropionic Acid (3-NP)-Induced Striatal Toxicity: Possible Role of Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation, and Neurotransmitters. Physiol Behav 2016, 155, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotagale, N.R.; Taksande, B.G.; Inamdar, N.N. Neuroprotective Offerings by Agmatine. Neurotoxicology 2019, 73, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeo, F.; Eisenberg, T.; Pietrocola, F.; Kroemer, G. Spermidine in Health and Disease. Science (1979) 2018, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rgen Haas, J.; Storch-Hagenlocher, B.; Biessmann, A.; Wildemann, B. Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase and Argininosuccinate Synthetase: Co-Induction in Brain Tissue of Patients with Alzheimer’s Dementia and Following Stimulation with b-Amyloid 1-42 in Vitro;

- Casewell, N.R.; Jackson, T.N.W.; Laustsen, A.H.; Sunagar, K. Causes and Consequences of Snake Venom Variation. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2020, 41, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim, A.M.B.; Piochi, L.F.; Gaspar, A.T.; Preto, A.J.; Rosário-Ferreira, N.; Moreira, I.S. Advancing Drug Safety in Drug Development: Bridging Computational Predictions for Enhanced Toxicity Prediction. Chem Res Toxicol 2024, 37, 827–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, T.P.; Alderton, W.K.; Reynolds, H.M.; Roach, A.G.; Berghmans, S. Zebrafish: An Emerging Technology for in Vivo Pharmacological Assessment to Identify Potential Safety Liabilities in Early Drug Discovery. Br J Pharmacol 2008, 154, 1400–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, P.; Li, C.Q. Zebrafish: A Predictive Model for Assessing Drug-Induced Toxicity. Drug Discov Today 2008, 13, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, R.A.; Mir, M.N.; Malik, I.A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Alshabrmi, F.M.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Alhomrani, M.; Alamri, A.S.; Alsanie, W.F.; Hjazi, A.; et al. The Potential Mechanism and the Role of Antioxidants in Mitigating Oxidative Stress in Alzheimer’s Disease. Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark 2025, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, C.; Chatonnet, A.; Takke, C.; Yan, Y.L.; Postlethwait, J.; Toutant, J.P.; Cousin, X. Zebrafish Acetylcholinesterase Is Encoded by a Single Gene Localized on Linkage Group 7. Gene Structure and Polymorphism; Molecular Forms and Expression Pattern during Development. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richetti, S.K.; Rosemberg, D.B.; Ventura-Lima, J.; Monserrat, J.M.; Bogo, M.R.; Bonan, C.D. Acetylcholinesterase Activity and Antioxidant Capacity of Zebrafish Brain Is Altered by Heavy Metal Exposure. Neurotoxicology 2011, 32, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sant’Anna, M.C.B.; de Soares, V.M.; Seibt, K.J.; Ghisleni, G.; Rico, E.P.; Rosemberg, D.B.; de Oliveira, J.R.; Schröder, N.; Bonan, C.D.; Bogo, M.R. Iron Exposure Modifies Acetylcholinesterase Activity in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Tissues: Distinct Susceptibility of Tissues to Iron Overload. Fish Physiol Biochem 2011, 37, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademi, N.; Mehrnia, N.; Roshan, M.E. Bioactive Peptides: A Complementary Approach for Cancer Therapy. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Care 2024, 9, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.L.; Hu, C.X.; Li, D.H.; Liu, Y.D. Lipid Peroxidation and Antioxidant Responses in Zebrafish Brain Induced by Aphanizomenon Flos-Aquae DC-1 Aphantoxins. Aquatic Toxicology 2013, 144–145, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Hou, Y.; Maeng, J.H.; Shah, N.M.; Chen, Y.; Lawson, H.A.; Yang, H.; Yue, F.; Wang, T. Epigenomic Analysis Reveals Prevalent Contribution of Transposable Elements to Cis -Regulatory Elements, Tissue-Specific Expression, and Alternative Promoters in Zebrafish. Genome Res 2022, 32, 1424–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyker, A.G.; Lees, K.R. Duration of Neuroprotective Treatment for Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 1998, 29, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.; Butcher, G.Q.; Hoyt, K.R.; Impey, S.; Obrietan, K. Activity-Dependent Neuroprotection and CAMP Response Element-Binding Protein (CREB): Kinase Coupling, Stimulus Intensity, and Temporal Regulation of CREB Phosphorylation at Serine 133. The Journal of Neuroscience 2005, 25, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, N.M.; Santos, N.A.G.; Sartim, M.A.; Cintra, A.C.O.; Sampaio, S.V.; Santos, A.C. A Tripeptide Isolated from Bothrops Atrox Venom Has Neuroprotective and Neurotrophic Effects on a Cellular Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Chem Biol Interact 2015, 235, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SALEM, F.E.; YEHIA, H.M.; KORANY, S.M.; ALARJANI, K.M.; AL-MASOUD, A.H.; ELKHADRAGY, M.F. Neurotherapeutic Effects of Prodigiosin Conjugated with Silver-Nanoparticles in Rats Exposed to Cadmium Chloride-Induced Neurotoxicity. Food Science and Technology 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, M.E.; Timme-Laragy, A.R.; Karchner, S.I.; Stegeman, J.J. Nrf2 and Nrf2-Related Proteins in Development and Developmental Toxicity: Insights from Studies in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). Free Radic Biol Med 2015, 88, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, E.S.; Severance, E.G.; Arsenault, P.; Zahn, S.M.; Timme-Laragy, A.R. Activation of Nrf2 at Critical Windows of Development Alters Tissue-Specific Protein S-Glutathionylation in the Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Embryo. Antioxidants 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staurengo-Ferrari, L.; Badaro-Garcia, S.; Hohmann, M.S.N.; Manchope, M.F.; Zaninelli, T.H.; Casagrande, R.; Verri, W.A. Contribution of Nrf2 Modulation to the Mechanism of Action of Analgesic and Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Pre-Clinical and Clinical Stages. Front Pharmacol 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Gao, W.; Hu, H.; Zhou, S. Why 90% of Clinical Drug Development Fails and How to Improve It? Acta Pharm Sin B 2022, 12, 3049–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciulla, M.G.; Gelain, F. Structure–Activity Relationships of Antibacterial Peptides. Microb Biotechnol 2023, 16, 757–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.C.; Cui, J.Y.; Liu, J.; Lu, H.; Zhong, X.; Klaassen, C.D. RNA-Seq Provides New Insights on the Relative MRNA Abundance of Antioxidant Components during Mouse Liver Development. Free Radic Biol Med 2019, 134, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, M.G.; Gallagher, E.P. A Targeted Gene Expression Platform Allows for Rapid Analysis of Chemical-Induced Antioxidant MRNA Expression in Zebrafish Larvae. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0171025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borra, R.C.; Lotufo, M.A.; Gagioti, S.M.; Barros, F. de M.; Andrade, P.M. A Simple Method to Measure Cell Viability in Proliferation and Cytotoxicity Assays. Braz Oral Res 2009, 23, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feoktistova, M.; Geserick, P.; Leverkus, M. Crystal Violet Assay for Determining Viability of Cultured Cells. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2016, 2016, pdb.prot087379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes.; European Union, 2010; pp. 33–79.

- Conselho Nacional de Controle de Experimentação Animal (CONCEA) Capítulo 8—Peixes. In Guia Brasileiro de Produção, Manutenção ou Utilização de Animais em Atividades de Ensino ou Pesquisa Científica; Brasília.

- Test No. 236: Fish Embryo Acute Toxicity (FET) Test; OECD, 2013; ISBN 9789264203709.

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal Biochem 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.F.O.; Pinho, B.R.; Santos, M.M.; Oliveira, J.M.A. Disruptions of Circadian Rhythms, Sleep, and Stress Responses in Zebrafish: New Infrared-Based Activity Monitoring Assays for Toxicity Assessment. Chemosphere 2022, 305, 135449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MARKLUND, S.; MARKLUND, G. Involvement of the Superoxide Anion Radical in the Autoxidation of Pyrogallol and a Convenient Assay for Superoxide Dismutase. Eur J Biochem 1974, 47, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadwan, M.H. Simple Spectrophotometric Assay for Measuring Catalase Activity in Biological Tissues. BMC Biochem 2018, 19, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla, S.; Lassiter, T.L.; Hunter, D. Biochemical Measurement of Cholinesterase Activity. In Neurodegeneration Methods and Protocols; Harry, J., Tilson, H.A., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 1999; pp. 237–245. ISBN 978-1-59259-604-1. [Google Scholar]

- Issac, P.K.; Guru, A.; Velayutham, M.; Pachaiappan, R.; Arasu, M.V.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Choi, K.C.; Harikrishnan, R.; Arockiaraj, J. Oxidative Stress Induced Antioxidant and Neurotoxicity Demonstrated in Vivo Zebrafish Embryo or Larval Model and Their Normalization Due to Morin Showing Therapeutic Implications. Life Sci 2021, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rueden, C.T.; Schindelin, J.; Hiner, M.C.; DeZonia, B.E.; Walter, A.E.; Arena, E.T.; Eliceiri, K.W. ImageJ2: ImageJ for the next Generation of Scientific Image Data. BMC Bioinformatics 2017, 18, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).