Submitted:

30 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Cell Lines

2.2. Crude Venom and Obtaining PF

2.3. PF Characterization by Mass Spectrometry

2.4. Culture and Maintenance

2.5. Cytotoxic Effects of PF

2.6. Cell Integrity

2.7. Metabolic Activity

2.8. Neuroprotection Against Oxidative Stress in PC12 and mHippoE-18 Cells

2.8.1. H2O2-Induced Oxidative Stress Effects

2.8.2. Neuroprotection Assay

2.8.3. ROS Quantification

2.8.4. Label-Free Quantitative Mass Spectrometry Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

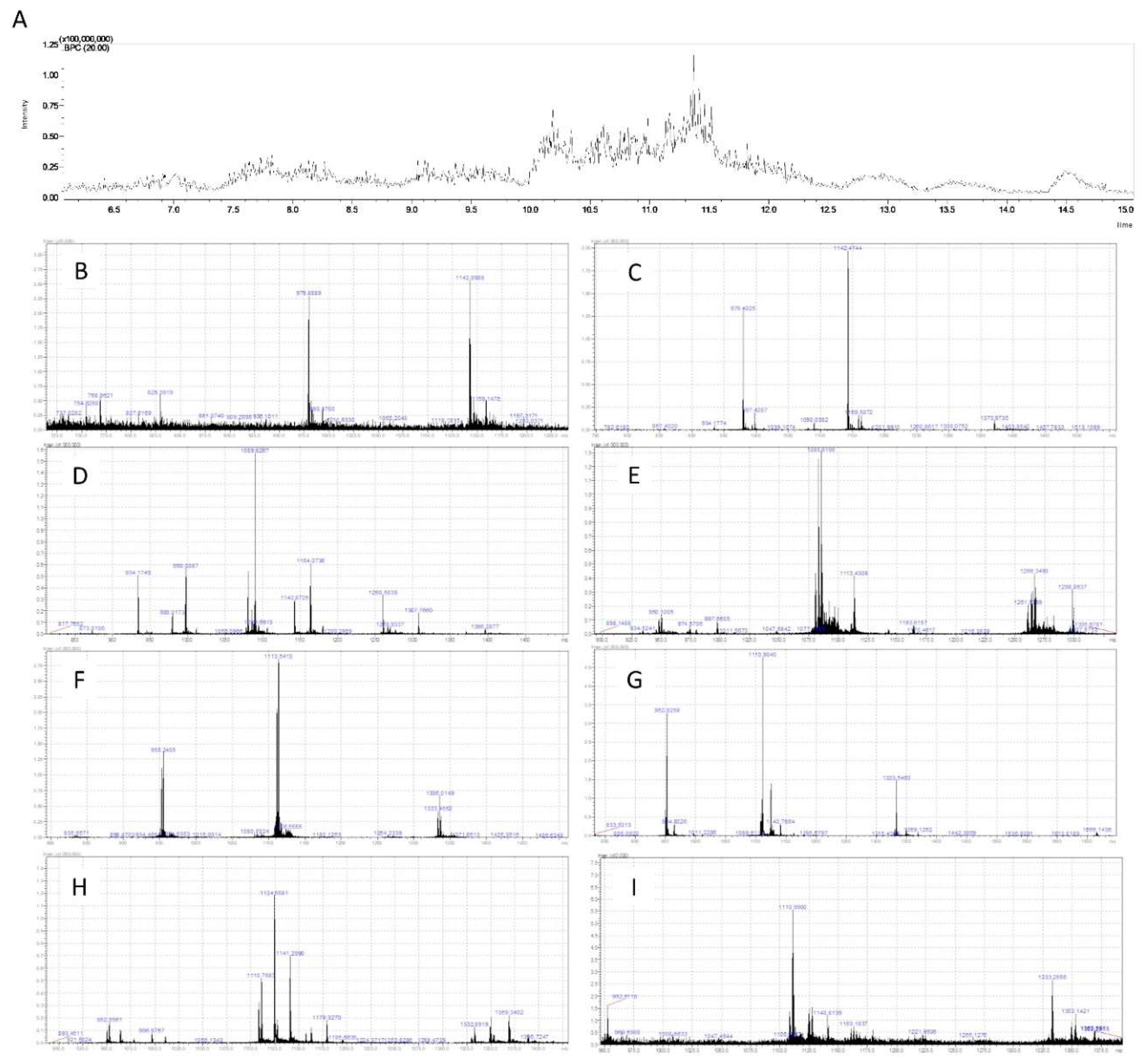

3.1. PF Analysis by Mass Spectrometry

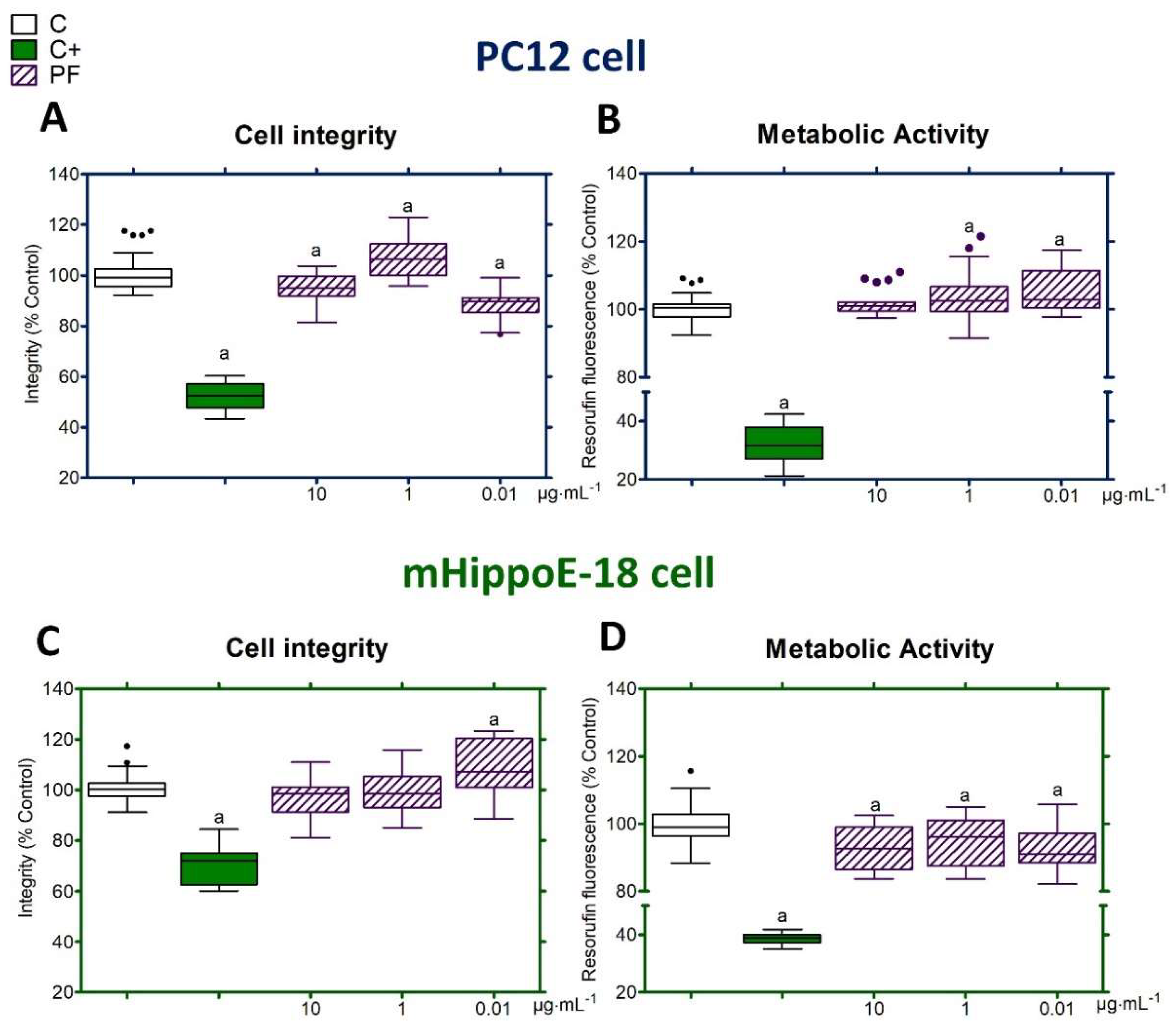

3.2. Toxicological Profile of PF

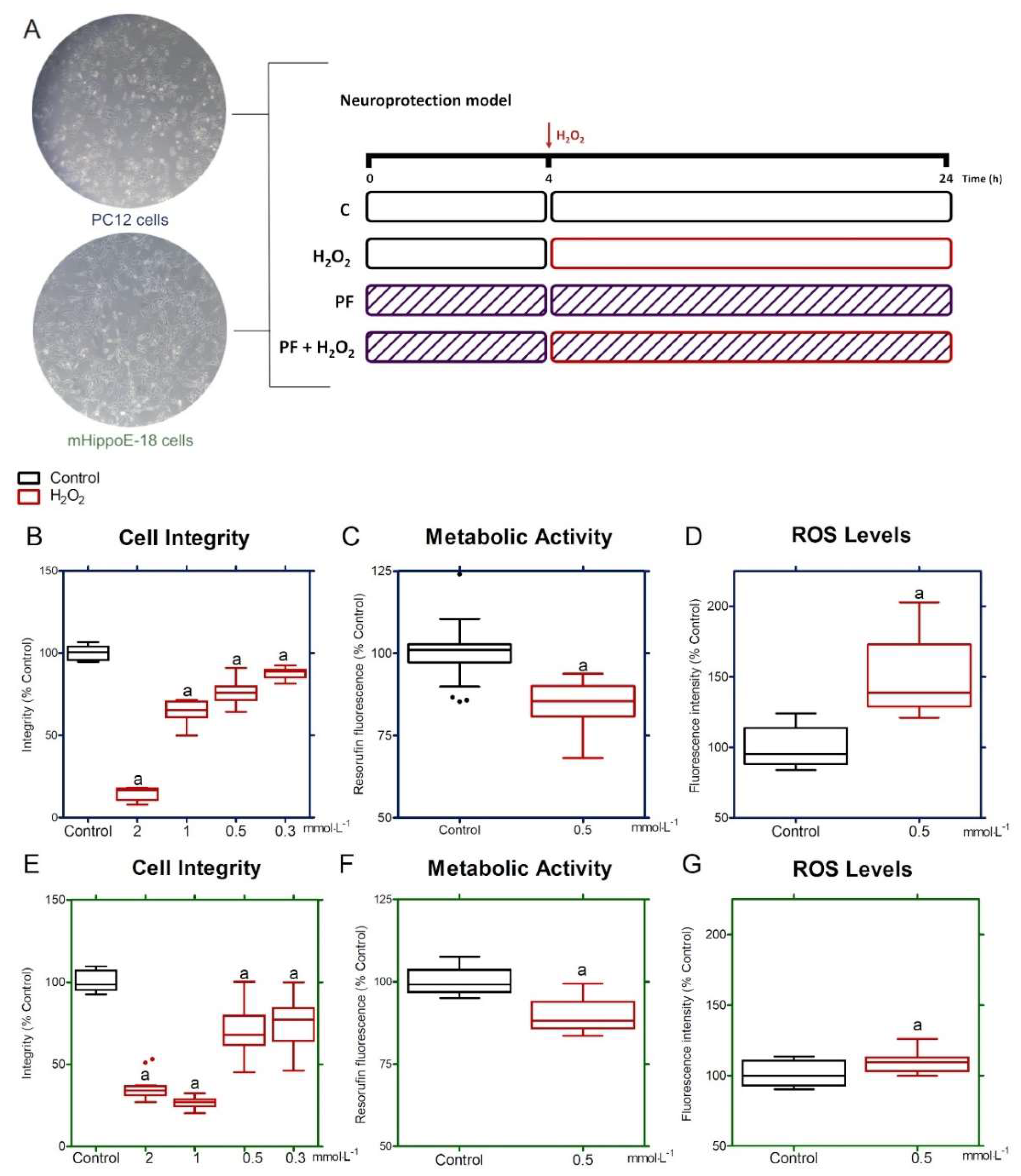

3.3. Oxidative Stress Model in PC12 and mHippoE-18 Cells

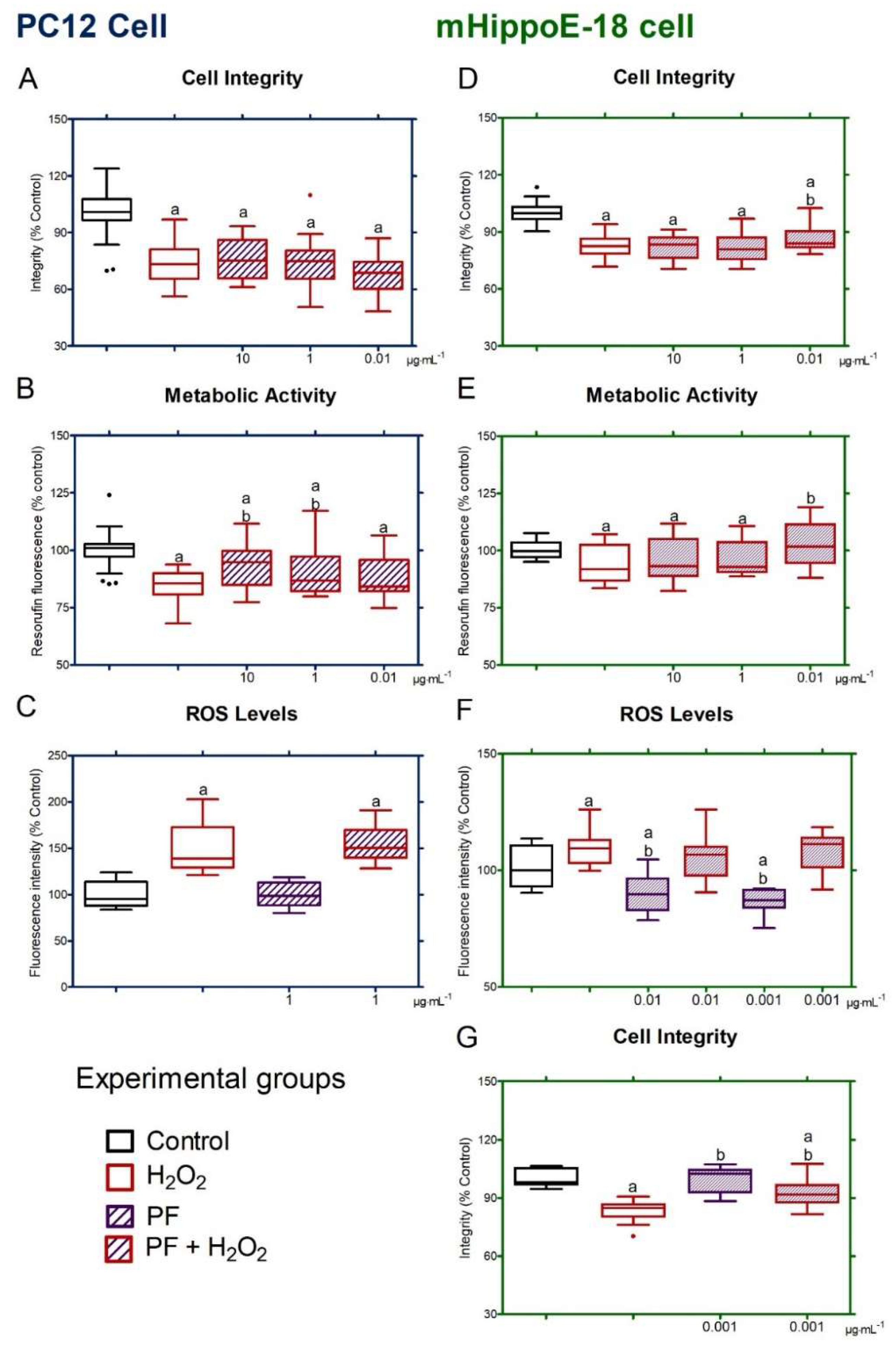

3.4. PF-Mediated Neuroprotection Against Oxidative Stress in PC12 and mHippoE-18 Cells

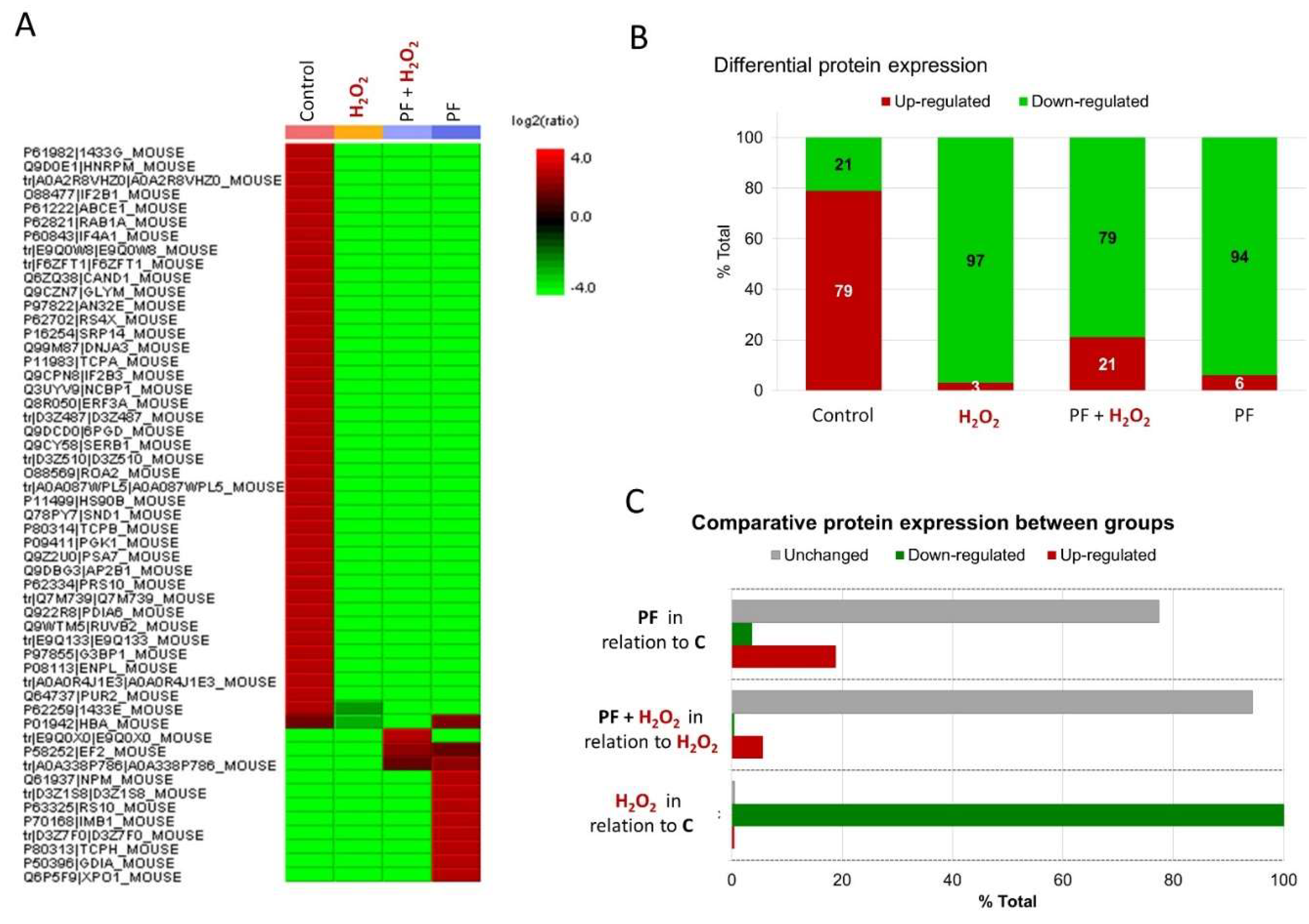

3.5. Quantitative Proteomics and Network Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Cconclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Alberto-Silva, C.; da Silva, B.R. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Neuroprotection by Oligopeptides from Snake Venoms. BIOCELL 2024, 48, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberto-Silva, C.; Portaro, F.C.V. Neuroprotection Mediated by Snake Venom. Natural Molecules in Neuroprotection and Neurotoxicity 2024, 437–451. [Google Scholar]

- Frangieh, J.; Rima, M.; Fajloun, Z.; Henrion, D.; Sabatier, J.M.; Legros, C.; Mattei, C. Snake Venom Components: Tools and Cures to Target Cardiovascular Diseases. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira Almeida, G.; de Oliveira, I.S.; Arantes, E.C.; Sampaio, S.V. Snake Venom Disintegrins Update: Insights about New Findings. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis 2023, 29, 20230039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, N.M.; Santos, N.A.G.; Sartim, M.A.; Cintra, A.C.O.; Sampaio, S.V.; Santos, A.C. A Tripeptide Isolated from Bothrops Atrox Venom Has Neuroprotective and Neurotrophic Effects on a Cellular Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Chem Biol Interact 2015, 235, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, N.M.; Ferreira, D.A.S.; Carvalho Rodrigues, M.A.; Cintra, A.C.O.; Santos, N.A.G.; Sampaio, S.V.; Santos, A.C. Low-Molecular-Mass Peptides from the Venom of the Amazonian Viper Bothrops Atrox Protect against Brain Mitochondrial Swelling in Rat: Potential for Neuroprotection. Toxicon 2010, 56, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querobino, S.M.; Ribeiro, C.A.J.; Alberto-Silva, C. Bradykinin-Potentiating PEPTIDE-10C, an Argininosuccinate Synthetase Activator, Protects against H2O2-Induced Oxidative Stress in SH-SY5Y Neuroblastoma Cells. Peptides (N.Y.) 2018, 103, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querobino, S.M.; Carrettiero, D.C.; Costa, M.S.; Alberto-Silva, C. Neuroprotective Property of Low Molecular Weight Fraction from B. Jararaca Snake Venom in H2O2-Induced Cytotoxicity in Cultured Hippocampal Cells. Toxicon 2017, 129, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querobino, S.M.; Costa, M.S.; Alberto-Silva, C. Protective Effects of Distinct Proline-Rich Oligopeptides from B. Jararaca Snake Venom against Oxidative Stress-Induced Neurotoxicity. Toxicon 2019, 167, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberto-Silva, C.; Pantaleão, H.Q.; da Silva, B.R.; da Silva, J.C.A.; Echeverry, M.B. Activation of M1 Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors by Proline-Rich Oligopeptide 7a (<EDGPIPP) from Bothrops Jararaca Snake Venom Rescues Oxidative Stress-Induced Neurotoxicity in PC12 Cells. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis 2024, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Pantaleão, H.Q.; Araujo da Silva, J.C.; Rufino da Silva, B.; Echeverry, M.B.; Alberto-Silva, C. Peptide Fraction from B. Jararaca Snake Venom Protects against Oxidative Stress-Induced Changes in Neuronal PC12 Cell but Not in Astrocyte-like C6 Cell. Toxicon 2023, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munawar, A.; Ali, S.A.; Akrem, A.; Betzel, C. Snake Venom Peptides: Tools of Biodiscovery. Toxins (Basel) 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugger, B.N.; Dickson, D.W. Pathology of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadhave, D.G.; Sugandhi, V.V.; Jha, S.K.; Nangare, S.N.; Gupta, G.; Singh, S.K.; Dua, K.; Cho, H.; Hansbro, P.M.; Paudel, K.R. Neurodegenerative Disorders: Mechanisms of Degeneration and Therapeutic Approaches with Their Clinical Relevance. Ageing Res Rev 2024, 99, 102357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlikowska, R. Whether Short Peptides Are Good Candidates for Future Neuroprotective Therapeutics? Peptides (N.Y.) 2021, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Li, H.; Liao, P.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Zheng, M.; Gao, J. Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Mechanisms and Advances in Therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durães, F.; Pinto, M.; Sousa, E. Old Drugs as New Treatments for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, F.; Edison, P. Neuroinflammation and Microglial Activation in Alzheimer Disease: Where Do We Go from Here? Nat Rev Neurol 2021, 17, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Dhalaria, R.; Guleria, S.; Cimler, R.; Sharma, R.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Valko, M.; Nepovimova, E.; Dhanjal, D.S.; Singh, R.; et al. Anti-Oxidant Potential of Plants and Probiotic Spp. in Alleviating Oxidative Stress Induced by H2O2. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 165, 115022. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, M.R.; Chaudhary, S.; Sharma, Y.; Singh, T.A.; Mishra, A.K.; Sharma, S.; Mehdi, M.M. Aging, Oxidative Stress and Degenerative Diseases: Mechanisms, Complications and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Biogerontology 2023, 24, 609–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci-Çekiç, S.; Özkan, G.; Avan, A.N.; Uzunboy, S.; Çapanoğlu, E.; Apak, R. Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defense. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2022, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Yu, S.; Jiang, Z.; Liang, C.; Yu, W.; Li, J.; Du, X.; Wang, H.; Gao, X.; Wang, X. N-Acetyl-Serotonin Protects HepG2 Cells from Oxidative Stress Injury Induced by Hydrogen Peroxide. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberto-Silva, C.; da Silva, B.R.; da Silva, J.C.A.; Cunha e Silva, F.A. da; Kodama, R.T.; da Silva, W.D.; Costa, M.S.; Portaro, F.C.V. Small Structural Differences in Proline-Rich Decapeptides Have Specific Effects on Oxidative Stress-Induced Neurotoxicity and L-Arginine Generation by Arginosuccinate Synthase. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2024, 17, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shehri, S.S. Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species and Innate Immune Response. Biochimie 2021, 181, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, S.; Abramov, A.Y. Mechanism of Oxidative Stress in Neurodegeneration. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2012, 2012, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, S.; Bagheri, M. In Vivo, in Vitro and Pharmacologic Models of Parkinson’s Disease. Physiol Res 2019, 68, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casewell, N.R.; Jackson, T.N.W.; Laustsen, A.H.; Sunagar, K. Causes and Consequences of Snake Venom Variation. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2020, 41, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slowinski JB, W.W. A New Cobra (Elapidae: Naja) from Myanmar (Burma) on JSTOR. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3893276 (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- Neto, E.B.; Coelho, G.R.; Sciani, J.M.; Pimenta, D.C. Proteomic Characterization of Naja Mandalayensis Venom. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis 2021, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, N.A.H.; Sainik, N.Q.A.V.; Esa, E.; Muhamad Hendri, N.A.; Ahmad Rusmili, M.R.; Hodgson, W.C.; Shaikh, M.F.; Othman, I. Neuroprotective Effect of Phospholipase A2 from Malaysian Naja Sumatrana Venom against H2O2-Induced Cell Damage and Apoptosis. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.-H. n; Wang, W.-L.; Dai, R.; Yan, H.-W.; Han, C.-N.; Liu, L.-S. Current Situation of PC12 Cell Use in Neuronal Injury Study. Int J Biotechnol Wellness Ind 2015, 4, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de los Rios, C.; Cano-Abad, M.F.; Villarroya, M.; López, M.G. Chromaffin Cells as a Model to Evaluate Mechanisms of Cell Death and Neuroprotective Compounds. Pflugers Arch 2018, 470, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiatrak, B.; Kubis-Kubiak, A.; Piwowar, A.; Barg, E. PC12 Cell Line: Cell Types, Coating of Culture Vessels, Differentiation and Other Culture Conditions. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, L.A.; Tischler, A.S. Establishment of a Noradrenergic Clonal Line of Rat Adrenal Pheochromocytoma Cells Which Respond to Nerve Growth Factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1976, 73, 2424–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gingerich, S.; Kim, G.L.; Chalmers, J.A.; Koletar, M.M.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Belsham, D.D. Estrogen Receptor α and G-Protein Coupled Receptor 30 Mediate the Neuroprotective Effects of 17β-Estradiol in Novel Murine Hippocampal Cell Models. Neuroscience 2010, 170, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feoktistova, M.; Geserick, P.; Leverkus, M. Crystal Violet Assay for Determining Viability of Cultured Cells. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2016, 2016, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, B.R.; Reis, S.D.; Hartley, R.C.; Murphy, M.P.; Oliveira, J.M.A. Mitochondrial Superoxide Generation Induces a Parkinsonian Phenotype in Zebrafish and Huntingtin Aggregation in Human Cells. Free Radic Biol Med 2019, 130, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseti, I.B.; Rocha, J.B.T.; Costa, M.S. Diphenyl Diselenide (PhSe)2 Inhibits Biofilm Formation by Candida Albicans, Increasing Both ROS Production and Membrane Permeability. J Trace Elem Med Biol 2015, 29, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beraldo-Neto, E.; Ferreira, V.F.; Vigerelli, H.; Fernandes, K.R.; Juliano, M.A.; Nencioni, A.L.A.; Pimenta, D.C. Unraveling Neuroprotection with Kv1.3 Potassium Channel Blockade by a Scorpion Venom Peptide. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, J.M.; Goncalves, B.D.C.; Gomez, M.V.; Vieira, L.B.; Ribeiro, F.M. Animal Toxins as Therapeutic Tools to Treat Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, A.; Trusch, M.; Georgieva, D.; Hildebrand, D.; Kwiatkowski, M.; Behnken, H.; Harder, S.; Arni, R.; Spencer, P.; Schlüter, H.; et al. Elapid Snake Venom Analyses Show the Specificity of the Peptide Composition at the Level of Genera Naja and Notechis. Toxins (Basel) 2014, 6, 850–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasoulis, T.; Isbister, G.K. A Current Perspective on Snake Venom Composition and Constituent Protein Families. Archives of Toxicology 2022, 97, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Chu, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Pang, Z.; Chen, N. Neuroinflammatory In Vitro Cell Culture Models and the Potential Applications for Neurological Disorders. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, W.Q.; Kalogeropoulos, K.; Allentoft, M.E.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Zhao, W.N.; Workman, C.T.; Knudsen, C.; Jiménez-Mena, B.; Seneci, L.; Mousavi-Derazmahalleh, M.; et al. The Rise of Genomics in Snake Venom Research: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Gigascience 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, C.; Luo, T.; Zhang, S.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Ge, P. Lycopene Protects Human SH-SY5Y Neuroblastoma Cells against Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Death via Inhibition of Oxidative Stress and Mitochondria-Associated Apoptotic Pathways. Mol Med Rep 2016, 13, 4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.Y.; Wu, T.T.; Hwang, B.R.; Lee, J.; Lee, M.H.; Lee, S.; Cho, E.J. The Neuro-Protective Effect of the Methanolic Extract of Perilla Frutescens Var. Japonicaand Rosmarinic Acid against H₂O₂-Induced Oxidative Stress in C6 Glial Cells. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2016, 24, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ju, X.; Chen, Y.; Dong, X.; Luo, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D. Effects of L-Carnitine against H2O2-Induced Oxidative Stress in Grass Carp Ovary Cells (Ctenopharyngodon Idellus). Fish Physiol Biochem 2016, 42, 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansor, N.I.; Ling, K.H.; Rosli, R.; Hassan, Z.; Adenan, M.I.; Nordin, N. Centella Asiatica (L.) Urban. Attenuates Cell Damage in Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Oxidative Stress in Transgenic Murine Embryonic Stem Cell Line-Derived Neural-Like Cells: A Preliminary Study for Potential Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2023, 94, S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, F. Chemical Basis of Reactive Oxygen Species Reactivity and Involvement in Neurodegenerative Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingappa, S.; Shivakumar, M.S.; Manivasagam, T.; Somasundaram, S.T.; Seedevi, P. Neuroprotective Effect of Epalrestat on Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Neurodegeneration in SH-SY5Y Cellular Model. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2021, 31, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ye, J.; Dong, G. Neuroprotective Effect of Baicalein on Hydrogen Peroxide-Mediated Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in PC12 Cells. J Mol Neurosci 2010, 40, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerszon, J.; Rodacka, A. Determination of Trans-Resveratrol Action on Two Different Types of Neuronal Cells, Neuroblastoma and Hippocampal Cells. Czech Journal of Food Sciences 2016, 34, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Kumar, A. Harnessing Mitophagy for Therapeutic Advances in Aging and Chronic Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neuroglia 2024, 5, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houldsworth, A. Role of Oxidative Stress in Neurodegenerative Disorders: A Review of Reactive Oxygen Species and Prevention by Antioxidants. Brain Commun 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, H.S.; Real, C.; Cyrne, L.; Soares, H.; Antunes, F. Hydrogen Peroxide Sensing, Signaling and Regulation of Transcription Factors. Redox Biol 2014, 2, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynes, R.; Pomatto, L.C.D.; Davies, K.J.A. Degradation of Oxidized Proteins by the Proteasome: Distinguishing between the 20S, 26S, and Immunoproteasome Proteolytic Pathways. Mol Aspects Med 2016, 50, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A.; Parrado, J.; Bougria, M.; Machado, A. Effect of Oxidative Stress, Produced by Cumene Hydroperoxide, on the Various Steps of Protein Synthesis. Modifications of Elongation Factor-2. J Biol Chem 1996, 271, 23105–23110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijk, S.J.L.; Timmers, H.T.M. The Family of Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzymes (E2s): Deciding between Life and Death of Proteins. FASEB J 2010, 24, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, R.; Merrill, A.R.; Andersen, G.R. The Life and Death of Translation Elongation Factor 2. Biochem Soc Trans 2006, 34, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, V.; Duennwald, M.L. Nrf2 and Oxidative Stress: A General Overview of Mechanisms and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, K.R.; Riaz, T.A.; Kim, H.R.; Chae, H.J. The Aftermath of the Interplay between the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response and Redox Signaling. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2021, 53, 151–167. [Google Scholar]

- Dasuri, K.; Zhang, L.; Keller, J.N. Oxidative Stress, Neurodegeneration, and the Balance of Protein Degradation and Protein Synthesis. Free Radic Biol Med 2013, 62, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuehlke, A.; Johnson, J.L. Hsp90 and Co-Chaperones Twist the Functions of Diverse Client Proteins. Biopolymers 2010, 93, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seixas, C.; Cruto, T.; Tavares, A.; Gaertig, J.; Soares, H. CCTα and CCTδ Chaperonin Subunits Are Essential and Required for Cilia Assembly and Maintenance in Tetrahymena. PLoS One 2010, 5, e10704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yoo, Y.; Fan, H.; Kim, E.; Guan, K.L.; Guan, J.L. Regulation of Integrin β 1 Recycling to Lipid Rafts by Rab1a to Promote Cell Migration. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 29398–29405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcello, E.; Saraceno, C.; Musardo, S.; Vara, H.; De La Fuente, A.G.; Pelucchi, S.; Di Marino, D.; Borroni, B.; Tramontano, A.; Pérez-Otaño, I.; et al. Endocytosis of Synaptic ADAM10 in Neuronal Plasticity and Alzheimer’s Disease. J Clin Invest 2013, 123, 2523–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, K.; Uemura, M.; Munakata, K.; Takahashi, H.; Haraguchi, N.; Nishimura, J.; Hata, T.; Matsuda, C.; Ikenaga, M.; Murata, K.; et al. Fructose-Bisphosphate Aldolase A Is a Key Regulator of Hypoxic Adaptation in Colorectal Cancer Cells and Involved in Treatment Resistance and Poor Prognosis. Int J Oncol 2017, 50, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.K.; Morrison, D.K. 14-3-3 Proteins: Diverse Functions in Cell Proliferation and Cancer Progression. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2011, 22, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, K.S.; Powers, M.A.; Forbes, D.J. Nuclear Export Receptors: From Importin to Exportin. Cell 1997, 90, 967–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhana, A.; Lappin, S.L. Biochemistry, Lactate Dehydrogenase. StatPearls 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).